Abstract

AHAS (acetohydroxyacid synthase) catalyses the first committed step in the biosynthesis of branched-chain amino acids, such as valine, leucine and isoleucine. Owing to the unique presence of these biosynthetic pathways in plants and micro-organisms, AHAS has been widely investigated as an attractive target of several classes of herbicides. Recently, the crystal structure of the catalytic subunit of yeast AHAS has been resolved at 2.8 Å (1 Å=0.1 nm), showing that the active site is located at the dimer interface and is near the herbicide-binding site. In this structure, the existence of two disordered regions, a ‘mobile loop’ and a C-terminal ‘lid’, is worth notice. Although these regions contain the residues that are known to be important in substrate specificity and in herbicide resistance, they are poorly folded into any distinct secondary structure and are not within contact distance of the cofactors. In the present study, we have tried to demonstrate the role of these regions of tobacco AHAS by constructing variants with serial deletions, based on the structure of yeast AHAS. In contrast with the wild-type AHAS, the truncated mutant which removes the C-terminal lid, Δ630, and the internal deletion mutant without the mobile loop, Δ567–582, impaired the binding affinity for ThDP (thiamine diphosphate), and showed different elution profiles representing a monomeric form in gel-filtration chromatography. Our results suggest that these regions are involved in the binding/stabilization of the active dimer and ThDP binding.

Keywords: acetohydroxyacid synthase (AHAS), cofactor binding, deletion mutant, functional domain analysis, thiamine diphosphate, tobacco

Abbreviations: AHAS, acetohydroxyacid synthase; BFDC, benzoylformate decarboxylase; GST, glutathione S-transferase; IPTG, isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside; PDC, pyruvate decarboxylase; POX, pyruvate oxidase; ThDP, thiamine diphosphate

INTRODUCTION

Acetohydroxyacid is a precursor of the branched-chain amino acids, leucine, valine and isoleucine. It is formed in a reaction catalysed by AHAS (acetohydroxyacid synthase, EC 2.2.1.6) in which a pyruvate is decarboxylated and condensed with either a second pyruvate to form 2-acetolactate, or 2-ketobutyrate to form 2-aceto-2-hydroxybutyrate (reviewed in [1,2]). AHAS, in common with several other enzymes that catalyse the decarboxylation of 2-ketoacids, requires ThDP (thiamine diphosphate) as a cofactor and a bivalent metal ion, such as Mg2+, that anchors ThDP in the active site [3]. It also has an essential requirement for FAD, which is unexpected, because the reaction involves no redox reaction.

The branched-chain amino acids are not synthesized in animals, but are made by micro-organisms and plants. This makes AHAS an attractive target for herbicides, and several compounds that are widely used in agriculture act as specific and potent inhibitors of the enzyme [4–7]. These compounds bear no structural resemblance to the substrate and are not competitive inhibitors, suggesting that they do not bind at the active site. An unusual feature of plant AHAS is that it is inhibited by all three of the branched-chain amino acids, unlike most bacterial and fungal enzymes that are sensitive only to valine [6,8,9]. Moreover, there is synergistic inhibition by the combination of leucine with valine. These properties are observed for the plant enzyme extracted from its native source as well as reconstitution in vitro using the purified Arabidopsis thaliana subunits expressed in Escherichia coli [9].

Biochemical analysis based on bacterial AHAS isoenzymes revealed that they have a common α2β2 tetrameric structure, consisting of two large (catalytic, ∼60 kDa), and two small (regulatory, 10–17 kDa) subunits. These two small subunits play roles in feedback regulation [10,11], activity and stability [12,13]. In contrast with the bacterial enzyme, the structure and biochemical properties of AHAS from eukaryotes have been poorly characterized. Recently, the three-dimensional structure of yeast AHAS has been resolved [14]. This crystal structure reveals the location of several active-site features, including the position and conformation of the cofactors ThDP, Mg2+ and FAD. An interesting feature of the crystal structure of AHAS is the exposed environment of its active sites to solvent. Many lines of evidence indicate that a hydrophobic environment is required for the decarboxylation step of the reaction. The three-dimensional structure shows that the active site is quite open, with the entire thiazolium ring, C-4′, N-4′, C-6, C-7 and C-7′, fully accessible to solvent. In the crystal structure of other ThDP-dependent enzymes, the coenzyme is less accessible, with no more than C-2, S-1 and N-4′ exposed, suggesting that the open structure in AHAS may not reflect the situation during catalysis, where mobile regions could cover the active site.

More recently, a second structure of yeast AHAS has been determined with a bound herbicide [15]. Although there are no major differences in the overall fold of both structures when the dimeric structures are compared, there are noticeable differences in the structure of AHAS in the presence of the inhibitors, i.e. two important changes are observed in this complex. First, three domains of each monomer of AHAS are brought closer together in the complex, resulting in a reduction in the volume occupied by the active and herbicide-binding sites. Secondly, a capping region, which consists of the last 38 C-terminal amino acid residues 650–687 (C-terminal ‘lid’) and a polypeptide segment consisting of amino acid residues 580–595 (‘mobile loop’), become ordered, further restricting solvent accessibility to the active site. This mobile cap is involved in the formation of a substrate access channel that is missing in the uncomplexed enzyme structure. As a result of the presence of the additional capping region in the structure of enzyme–inhibitor complex, most of ThDP is buried with only the C-2 atom of ThDP readily accessible to solvent. Therefore, although these regions of AHAS are not folded into any distinct secondary structure and are not within contact distance of the cofactors in free enzyme, they may be important because of their possible involvement during catalysis. By super-imposing the structure of AHAS with other ThDP-dependent enzymes, such as BFDC (benzoylformate decarboxylase), PDC (pyruvate decarboxylase) and POX (pyruvate oxidase), corresponding regions have also been observed. In contrast with AHAS, in BFDC and POX, these regions form a helix–loop structure covering the active site of the enzyme, and critical residues are located within these regions, including the amino acids corresponding to the interaction with Mg2+, the diphosphate group of ThDP and the thiazole ring of ThDP [16–18]. Furthermore, it has been documented that deletion of the last nine residues of Zymomonas mobilis PDC resulted in the loss of activity [19]. Therefore it can be postulated that, during catalysis, these regions of AHAS might close over the active site and form direct interactions with reaction intermediates as well as with herbicide inhibitors. This is supported by the fact that the putative mobile loop of yeast AHAS contains residues that are known to be important in substrate specificity (Trp586) and in herbicide resistance (Met582, Val583, Trp586 and Phe590) [20].

To investigate this possibility, we have performed C-terminal deletions of the enzyme, which are focused on the two mobile regions, the mobile loop and the C-terminal lid. We observed that enzyme activity is largely dependent on these two regions and the reduced activity is accompanied by a decreased affinity for ThDP. In the present study, we provide the first evidence to support the above hypothesis.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

Cell culture media, Bacto-tryptone and Bacto-yeast extract, were purchased from Difco. Restriction enzymes, Pfu DNA polymerase, T4 DNA ligase and other modifying enzymes were from Promega and TaKaRa SHUZO Co. (Shiga, Japan). IPTG (isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside), FAD, ThDP, α-naphthol, creatine, sodium pyruvate and other chemicals were from Sigma Chemical Co. Glutathione–Sepharose, benzamidine–Sepharose and Superdex G200 HR 10/30 were obtained from Amersham Biosciences. E. coli strains DH5α and BL21(DE3) were from Novagen.

Construction of C-terminal truncation mutants

Wild-type tobacco AHAS (Nta2, SurB), which lacks a part of the 5′ regions encoding the N-terminal transient peptide for chloroplast transport, was subcloned into the bacterial overexpression vector, pGEX-2T (Amersham Biosciences). This vector system produces a target protein as an N-terminal GST (glutathione S-transferase)-fusion protein for the rapid purification by a single affinity-chromatography column. To generate the C-terminal-truncated mutants of AHAS, we designed the oligonucleotides corresponding to the indicated regions. Mutant genes were obtained by PCR with specific primer sets, NKB1 for sense primer, 5′-CCGGATTCATGTCCACTACCCAA-3′, and the indicated deletion primers for antisense. The sequences of antisense primer for each C-terminal deletion mutant were as follows. AHAS Δ567, 5′-AAGGATCCTTAGTGTTGATTATTCAGTAA-3′; AHAS Δ598, 5′-AAGGATCCTTAAGGAAAGATCTCCGCCTC-3′ and AHAS Δ630, 5′-AAGGATCCTTAAGTGTCTAACATCTTTTG-3′. All primers for the mutant genes have a BamHI restriction enzyme site (underlined) and a stop codon. Internal deletion mutant of AHAS (Δ567–582) was produced by the ligation of two gene fragments, N-terminal (1–566) and C-terminal (583–655). These two fragments were prepared by PCR with the following primer sets: for the N-terminal fragment (1–566), NKB1 for sense primer and AHAS iF/N for antisense, 5′-GTGTTGATTATTCAGTAACAG-3′, and for the C-terminal fragment (583–655), AHAS iF/C for sense primer, 5′-GCACACACATACCTGGGGAAT-3′, and NKB2 for antisense, 5′-GGGGATTCTCAAAGTCAATAGG-3′ respectively. Primers AHAS iF/N and AHAS iF/C were modified by the attachment of a 5′-phosphate. These two fragments produced by PCR were purified and subjected to direct ligation. The products (internal deletion gene of AHAS, Δ567–582) were separated and isolated by the gel-elution method. Purified products were used as a template for PCR using NKB1 and NKB2 to amplify the internal deletion gene. All genes for AHAS mutants and the expression vector, pGEX-2T, were digested with BamHI. The vector was treated further with CIAP (calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase; Promega), and then a ligation reaction was performed with the indicated mutant genes by T4 DNA ligase. Plasmids containing mutant genes were isolated and their identity was confirmed by restriction enzyme mapping and by DNA sequencing.

Protein expression and purification

Plasmids harbouring mutant genes of the tobacco AHAS catalytic subunit were introduced into the expression host cell, DH5α. Cells were grown aerobically at 37 °C in LBA medium (Luria–Bertani medium containing 50 μg/ml ampicillin) to a D600 of 0.7–0.8 and induced by addition of IPTG to a final concentration of 1 mM at 30 °C. At 4 h post-induction, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 2408 g at 4 °C for 10 min. Pellets (3–4 g/l of culture) were resuspended in PBST buffer, containing 150 mM NaCl, 16 mM Na2HPO4, 4 mM NaH2PO4, pH 7.4, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100 and 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol, and incubated on ice for 10 min, followed by lysis via sonication. The cell lysates were centrifuged at 16278 g at 4 °C for 15 min, and the supernatant was incubated directly with glutathione–Sepharose 6B resin (500 μl of 50% slurry resin, which has a binding capacity of approx. 10 mg/ml for the 50% slurry resin; Amersham Biosciences) that was pre-equilibrated with PBST buffer. After a 30 min incubation at 4 °C, target protein (GST–AHAS) bound to the resin was collected by centrifugation (1115 g at 4 °C for 1 min) and the resin was vigorously washed with PBST buffer containing 250 mM NaCl and 5 mM glutathione. Proteins were eluted on a step gradient with 15 mM glutathione, pH 8.0, at 4 °C, and dialysed against buffer containing 20 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.0, 2 mM EDTA and 10% (v/v) glycerol.

Cleavage of purification tag (GST)

GST-free AHAS was prepared by two methods according to the experimental purpose. The conditions for the efficient removal of the GST tag were based on manufacturer's protocols (Sigma Chemical Co.). GST–AHAS containing a thrombin-recognition site was cleaved either while bound to glutathione or in solution after elution. First, we added thrombin to the resin. Following this cleavage reaction, supernatants were collected and GST-free AHAS was isolated by gel-filtration chromatography (Superdex G75 10/30 HR; Amersham Biosciences) or by ion-exchange chromatography (Q-Sepharose). Secondly, eluted GST–AHASs were digested with thrombin overnight at 4 °C. The GST-free AHAS was purified by the additional step of GST-affinity column chromatography.

AHAS assay

The AHAS activity was measured according to the method of Westerfeld [21] with the following modifications. Enzymes were pre-incubated in the presence or absence of various concentrations of cofactors at 37 °C for the indicated time period. The reaction was initiated by the addition of enzyme to the reaction mixture containing 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 1 mM ThDP, 20 μM FAD, 100 mM pyruvate and 10 mM MgCl2, unless otherwise described. Total reaction volume was 200 μl. After incubation at 37 °C for 1 h, the reaction was terminated by the addition of 20 μl of 3 M H2SO4, and the reaction product, acetolactate, was decarboxylated by incubation at 60 °C for 15 min. The acetoin produced by acidification was incubated further with 200 μl of 0.5% creatine (15 min), followed by incubation with 200 μl of 5% α-naphthol (15 min) at 60 °C. The absorbance of the coloured complex was measured at 525 nm (ε=20000 M−1·cm−1). Under the conditions used, product formation has been shown to proceed linearly with time over the period used. One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount required to form 1 μmol of acetolactate per min under the assay conditions as described above, and specific activity is expressed as units per mg of protein.

Gel-filtration chromatography

Gel-filtration chromatography was carried out at room temperature (25 °C) on Superdex G200 HR 10/30 connected to an FPLC system, Acta purifier (Amersham Biosciences). The column was pre-equilibrated with buffer A containing 100 mM Mops, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl and 10% (v/v) glycerol. Proteins were pre-incubated in buffer A containing 20 μM FAD at 37 °C for 15 min. The indicated amounts of enzyme were loaded on to the column and eluted with buffer A at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. The elution of protein was monitored by the absorbance at 280 nm.

Analysis of ThDP binding

The extent of ThDP binding was measured by monitoring the quenching of the intrinsic fluorescence of the enzyme after addition of increasing concentrations of ThDP. The purified enzymes were pre-incubated in buffer containing 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 20 μM FAD, 2 mM MgCl2 and the indicated concentrations of ThDP at 37 °C for 15 min, and the total protein concentration was adjusted to 0.1 mg/ml. Fluorescence spectra were obtained in 4 ml cylindrical quartz cuvettes. The wavelength of excitation was 300 nm and the emission was recorded in the range 310–450 nm (bandwidth of 2 nm). Each emission value was the mean for three independent experiments.

Analysis of the data

Steady-state kinetic data were plotted as a function of reciprocal substrate concentration, and data were analysed according to the appropriate rate equations using the Fortran programs of Cleland [22] and EnzFitter (a non-linear curve fitting program; BIOSOFT). Substrate and cofactor saturation curves were fitted to eqn (1) to obtain values of Vmax and Km:

|

(1) |

where v and A represent initial velocity and substrate concentration respectively.

The fluorescence-quenching data were analysed using eqn (2)

|

(2) |

where F0 is the intrinsic fluorescence of enzyme in the absence of quencher, F1 is the observed fluorescence at a given [Q] (concentration of quencher), fa is the fractional degree of fluorescence and Kd is the dissociation constant.

RESULTS

Construction and expression of C-terminal truncated tobacco AHAS

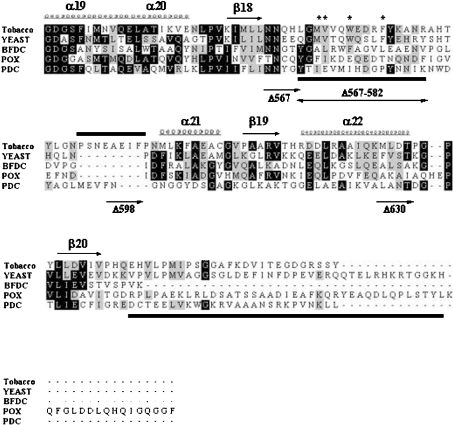

On the basis of the structure of yeast AHAS, sequence alignment using the ClustalX program showed two corresponding regions of tobacco AHAS (Figure 1). The putative mobile loop region of tobacco AHAS also contains three amino acids that are responsible for herbicide-resistance, Met569, Trp573 and Phe577 [23]. Interestingly, a unique region, residues 590–598, has been found in tobacco AHAS. A similar region has been identified in other plant sources, but not in yeast or bacteria. To investigate the role of these two disordered regions of catalytic subunit of tobacco AHAS, we constructed the serial C-terminal truncated mutants as follows. The mutant AHAS Δ567 deleted the entire C-terminus including the mobile loop and the C-terminal lid; Δ598 maintained the mobile loop and a unique region of tobacco AHAS, 590–598, but removed the remainder of the C-terminus; Δ630 deleted the C-terminal lid, and Δ567–582 deleted only the mobile loop region.

Figure 1. Alignment of the C-terminal region of various ThDP-dependent enzymes.

The sequences of the C-terminal region of various ThDP-dependent enzymes were analysed by amino acid alignment with the ClustalX program. Represented secondary structure, α-helix (α19–α22) and β-pleated sheet (β18–β20), was based on the X-ray crystal analysis of yeast AHAS. The indicated region (residues 549–687, yeast) is a part of the γ-domain of AHAS. The corresponding region of tobacco AHAS shown in this Figure is residues 536–669. BFDC is from Pseudomonas putida; POX is from Lactobacillus plantarum; PDC is from Zymomonas mobilis. Conserved residues are represented with a black shaded box, and residues with similarities are shown with a grey shaded box. An asterisk (*) represents the residues corresponding to herbicide-resistance for AHAS and the bars beneath the sequences indicate the two invisible (disordered) regions in the three-dimensional structure of yeast AHAS, which is postulated to be involved in enzyme catalysis by covering the active site. Also, sequences unique to plant AHASs, tobacco (590–598), Arabidopsis thaliana (591–599) and Brassica napus (576–583, Bna1) are represented by a bar above the sequences. Each C-terminal-truncated mutant has a portion of the C-terminal region of tobacco AHAS as follows: AHAS Δ567, AHAS without entire C-terminus including both mobile loop and the C-terminal lid; AHAS Δ567–582, internal deletion mutant AHAS without the mobile loop; AHAS Δ598, AHAS containing the mobile loop and unique plant sequences, but with the remainder of the C-terminus deleted; AHAS Δ630, AHAS without the regions corresponding to the C-terminal lid of yeast AHAS.

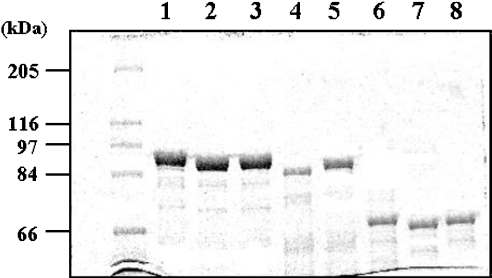

All mutants were expressed successfully as N-terminal GST-fusion proteins and were purified to homogeneity with similar expression levels (Figure 2). Interestingly, the deletion mutant, AHAS Δ567, showed a lower expression level, and a portion of protein was found in the insoluble fraction after lysis (results not shown). Since the expression host, E. coli, has three kinds of AHASs (AHAS I, 60 kDa; AHAS II, 59 kDa; and AHAS III, 63 kDa), it might be co-purified with our enzymes due to the heterogeneous dimerization. If hybrids occurred during overexpression or purification, they could be detected on SDS/PAGE in the lane containing GST–AHASs. However, as shown in Figure 2, there is only one significant protein band with an expected molecular mass for our GST–AHAS, suggesting that this possibility was completely ruled out.

Figure 2. SDS/PAGE analysis of the purified enzymes.

Purified proteins were resolved by SDS/10% PAGE. The first lane contains molecular-mass markers (sizes indicated in kDa), while the remaining lanes include the purified proteins designated in Figure 1 as wild-type tobacco AHAS (lane 1), AHAS Δ630 (lane 2), AHAS Δ567–582 (lane 3), AHAS Δ567 (lane 4) and AHAS Δ598 (lane 5). These enzymes were overexpressed as N-terminal GST-fusion proteins and purified by the affinity resin, glutathione–Sepharose. In addition, GST-free AHASs were generated by the treatment of thrombin described in the Experimental section and were analysed on the same SDS/PAGE gel in lane 6 (wild-type AHAS; 66 kDa), lane 7 (AHAS Δ630; 62 kDa), and lane 8 (AHAS Δ567–582; 64 kDa).

To determine the effects of these deletions on enzyme activity, we measured the enzyme activity under the standard saturating concentration of cofactors (1 mM ThDP, 20 μM FAD and 10 mM Mg2+) and substrate (100 mM pyruvate) as reported previously [24,25] (Table 1). All of the deletions greatly reduced the activity to that of a few percent of wild-type enzyme, and deletion of the entire C-terminus (Δ567), including both mobile loop and C-terminal lid, did not show any detectable activity. This result suggests that the C-terminus, containing these two regions, plays an important role in enzyme activity. Considering the active site shown in the three-dimensional structure of yeast AHAS, there are two possible explanations for the loss of activity: (i) the impairment of active dimer formation or (ii) failure to bind essential cofactors. To test these possibilities, the mobile loop deletion (Δ567–582) and the C-terminal lid deletion (Δ630) mutants were chosen for further characterization.

Table 1. Comparison of activities of C-terminal deletion mutants to that of wild-type AHAS.

Enzyme activity was determined in the mixture containing 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 1 mM ThDP, 20 μM FAD and 10 mM MgCl2. The reaction was initiated by the addition of substrate, 100 mM pyruvate, and incubated at 37 °C for 60 min. The reaction product, acetolactate, was converted into a coloured complex with creatine and α-naphthol, and the amount was measured at 525 nm (ε=20000 M−1·cm−1). Activities were determined using 50 nM of indicated enzymes.

| kcat (S−1)* | Relative activity (%)† | |

|---|---|---|

| Wild-type AHAS | 2.32 | 100 |

| Δ567 | Not detectable | Not detectable |

| Δ598 | 0.028 | 1.2 |

| Δ630 | 0.104 | 4.5 |

| Δ567–582 | 0.097 | 4.2 |

* kcat is equivalent to the number of substrate molecules converted into products in a given unit of time (s) on a single enzyme under the standard conditions of cofactors (1 mM ThDP, 20 μM FAD and 10 mM Mg2+).

† Relative activity was calculated by the activity of wild-type AHAS as a reference (100%).

The effects of deletion on quaternary structure of tobacco AHAS

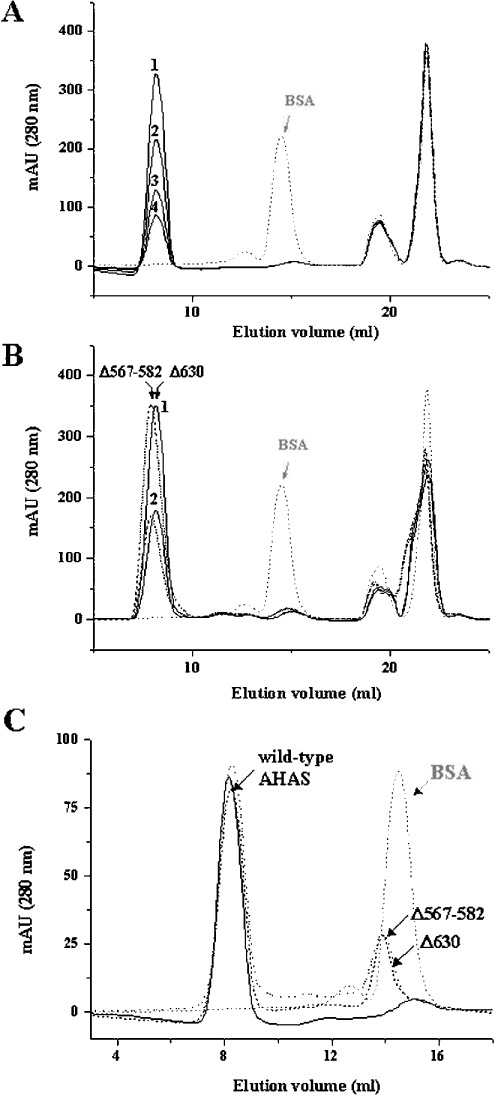

To test the effect of deletions on the quaternary structure of AHAS, which is related to active enzyme consisting of two AHAS monomers, we investigated the oligomeric state of the deletion mutants by gel-filtration chromatography. The enzymes were pre-incubated in buffer A [100 mM Mops, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl and 10% (v/v) glycerol] containing 20 μM FAD, and were applied to a size-exclusion column, Superdex G200, that had been pre-equilibrated with buffer A. As shown in Figure 3(A), the wild-type AHAS eluted as a single peak at a molecular mass of more than the dimer, compared with BSA (molecular mass, 66 kDa), which was used as a standard. In the elution profiles, the last two peaks that showed a yellow colour did not contain any protein fraction. These two peaks were also observed in samples without enzyme or with BSA standard in the same incubation buffer (buffer A containing 20 μM FAD), suggesting that these fractions correspond to FAD.

Figure 3. Gel-filtration chromatography of tobacco AHAS.

The enzymes were subjected to gel-filtration chromatography (Superdex G200 HR 10/30), and the molecular mass of the enzymes (GST-free AHAS: wild-type, 66 kDa; Δ630, 62 kDa and Δ567-582, 64 kDa) was estimated by comparison with the elution rate of BSA (66 kDa, grey dotted line, which is also indicated as an arrow) as a standard molecule. Each protein was pre-incubated in buffer A containing 20 μM FAD at 37 °C for 20 min, and subjected to loading on to the column that pre-equilibrated with the same buffer without 20 μM FAD. (A) The elution profile of wild-type AHAS. Elution rate of the major peak (1, 5 μM; 2, 3 μM; 3, 2 μM; 4, 1 μM) was much faster than that of the standard molecule (BSA). (B) The elution profiles of deletion mutants. Deletion mutants (Δ630, solid line and Δ567–582, broken line) were injected at a concentration of 6 μM (peak 1) or 3 μM (peak 2) and compared with the elution profile of BSA (arrow). (C) The elution profiles of wild-type and deletion mutants at 1 μM. When 1 μM mutant enzyme was applied to the gel-filtration chromatography column, another peak containing enzymes was observed at the position that overlapped with the peak of the standard molecule (arrow). Solid line, wild-type AHAS; dotted line, Δ567–582; broken line, Δ630.

In all tested concentrations of enzyme (0.1–5 μM), the elution profiles were nearly identical. In the case of two deletion mutants (Δ630 and Δ567–582), similar elution profiles were obtained (Figure 3B), suggesting that these deletions do not alter the quaternary structure of the enzyme. The representative peaks, indicating a dimer (or more) conformation, implied that other regions, rather than these two regions, are critical determinants of the interaction between two AHAS monomers. However, as the concentration of mutants was decreased (1 μM), another peak was also observed (Figure 3C). The peak was located near the position for the monomeric form, which roughly overlapped with the peak of the standard molecule, BSA. These results suggest that the binding affinities between two subunits of these mutants are much lower than that of wild-type enzyme, and that these two regions within the C-terminus of AHAS are involved in the stabilization of its quaternary structure. Therefore, given that the active site is located within the interface of two monomer subunits of AHAS, the reduced activities of the deletion mutants might be due to the impairment of active dimerization.

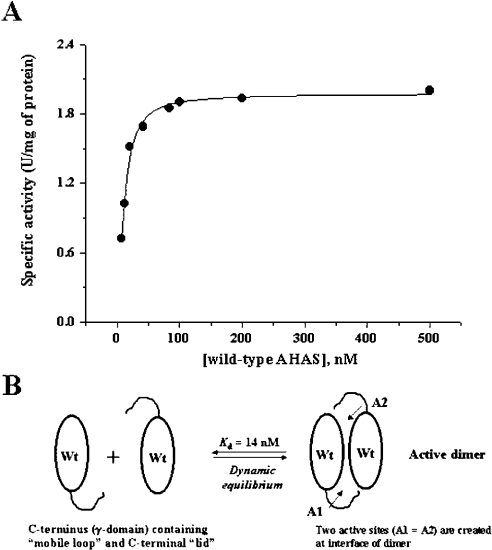

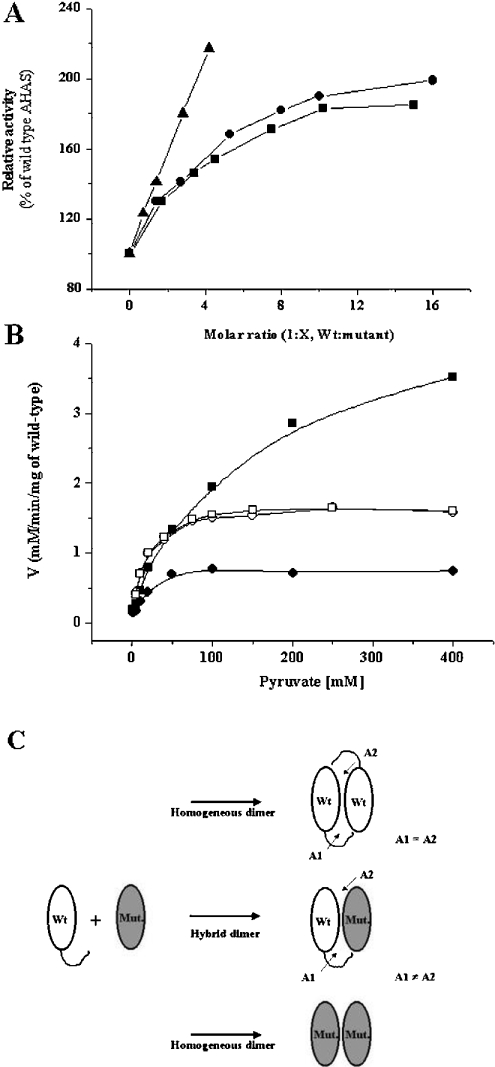

To test this possibility, we performed the enzyme assay using a high concentration of enzyme and carried out the reconstitution assay of mutants with wild-type AHAS. Before these experiments, we examined the specific activity in order to determine the quaternary structure of enzyme as a function of the protein concentration. Since active enzyme is composed of two identical monomer subunits of AHAS, a specific activity (units/mg of enzyme) could provide an indication of the dynamic equilibrium for dimerization. As seen in Figure 4, the constant specific activity was observed over 100 nM of wild-type enzyme. However, the specific activity below 50 nM of enzyme varied. This result suggested that the equilibrium dynamics favour the monomer at the low concentration. In a theoretical calculation using EnzFitter program, the Kd is 14.1±2.3 nM. Although it was not possible to determine the Kd values for the deletion mutants (they did not show any detectable activity at low concentration, ≤50 nM), we speculated that the deletion mutants have higher Kds than the wild-type enzyme. For this reason, we performed the enzyme assay using a high concentration of the deletion mutants at 5 μM, at which the quaternary structure of each mutant showed a single state corresponding to dimer (or more) as shown in Figure 3. However, there were no significant changes in specific activity (within 5%), implying that the loss of activity in each mutant was not due to the defect in active oligomer state of enzyme.

Figure 4. Specific activity of wild-type AHAS as the function of protein concentration.

(A) The specific activity was determined at various enzyme concentrations. Fitted data were from three independent experiments, and the curve was drawn using the hyperbola equation of EnzFitter program. Enzyme was pre-incubated in buffer containing 100 mM phosphate, pH 7.4, at 37 °C for 5 min, followed by addition of a cofactor mixture at saturating concentrations for an additional 10 min. The reaction was initiated by adding 100 mM of pyruvate and incubated at 37 °C for 60 min. The theoretical Kd is 14.1±2.3 nM. (B) Schematic illustration of a dynamic equilibrium. Catalytic subunits of AHAS associate to create the two active sites at the interface of the dimer. Each active site is composed of different polypeptide chains from individual subunits, and the C-terminus of each subunit is postulated to be one component of the active-site environment. The specific activity indicates the equilibrium dynamic with a Kd of 14 nM. Wt, wild-type. A1 and A2 are active sites.

To test this hypothesis further, reconstitution assays were performed using the wild-type and mutant proteins. In the crystal structure of yeast AHAS, a single active site is formed by different polypeptides of two subunits (α-domain of monomer A, β-domain of monomer B and γ-domain of monomer B) [14,15], and postulated to be covered with two disordered regions (a mobile loop and C-terminal lid) during catalysis. Therefore, if the enzyme could dissociate to release monomers of catalytic subunits and then reassociate, some of the reconstitution enzymes in a mixture of wild-type and mutants might be composed of heterogeneous hybrids containing one ‘normal’ and one ‘defective’ active site. Because the deletion mutants have low activity, the activity from a reconstitution assay might be attributed to the wild-type homodimer and the wild-type–mutant heterodimer. Once heterogeneous complexing has occurred, the kinetic parameters could be changed due to the different environments of the active sites. This prediction was tested in an experiment in which the wild-type and the deletion mutants were pre-incubated together, in different molar ratios, for 20 min at 37 °C before addition of the cofactors. To efficiently generate a heterogeneous complex, we used 15 nM of wild-type enzyme, the value of its theoretical Kd, and various higher concentrations of the deletion mutants. These conditions should favour hybrid dimer formation. As shown in gel-filtration experiments, mutants with deletions at each disordered region are able to associate to form intrinsic quaternary structures with somewhat lower binding affinities. Therefore, if wild-type AHAS, at the concentration that favours the monomer state, interacts and associates with mutants, the activities might increase because of heterogeneous hybrid formation.

Also, the conditions for the activity assay (100 mM pyruvate, 20 μM FAD, 1 mM ThDP and 10 mM MgCl2) were chosen so that mutants showed little activity. As shown in Figure 5(A), the hybrid dimers yielded higher activity than the sum of the activities of the wild-type and each deletion mutant. The highest activity of the hybrid dimers was obtained when the molar ratio was 1:10 (wild-type/mutant). It was saturable at around 2-fold. In addition, reconstitution assay under the condition that favour hybrid formation showed similar Kms for pyruvate (Figure 5B). Wild-type enzyme showed a Km for pyruvate of 10–15 mM, which is in line with previous reports for tobacco AHAS [24,26]. The hybrid dimers yielded Kms of 14 mM for Δ630 and 15 mM for Δ567–582 respectively. This result suggests that the activity was from just one ‘normal’ active site consisting of the C-terminal portion from the wild-type and another portions from the deletion mutants. The apparent 2-fold increase of the activity results from the higher total subunit concentration in the presence of the deletion mutant, which causes the dimerization of wild-type enzyme in the monomer state, so that there are higher numbers of active sites.

Figure 5. Reconstitution assay of wild-type AHAS with mutant enzymes.

(A) Relative activity of wild-type and mutant hybrid enzymes. A concentration of 15 nM of wild-type (the value of its theoretical Kd) and varying concentrations of mutants were pre-incubated in buffer (100 mM phosphate, pH 7.4) for 20 min at 37 °C, followed by addition of the cofactor mixtures containing 1 mM ThDP, 20 μM FAD and 10 mM MgCl2 for an additional 5 min. The reaction was initiated by adding 100 mM pyruvate. Relative activity was determined with the activity of wild-type AHAS as a control. Representative data was from four independent experiments (•, reconstitution with Δ630; ▪, reconstitution with Δ567–582; and ▴, reconstitution with W573F). (B) Substrate saturation curves of hybrid enzymes. A concentration of 15 nM of wild type AHAS was pre-incubated in the absence (•) or presence of 60 nM of W573F (▪), or 150 nM of each C-terminal deletion mutant (Δ567–582, □; Δ630, ○) in 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, at 37 °C for 15 min. The line represents a curve fitted to the data using the Michaelis–Menten equation, and Kms for pyruvate were 14.31±3.3 mM (wild-type alone), 14.29±1.02 mM (hybrid with Δ630), 14.90±1.00 mM (hybrid with Δ567–582) and 115.9±16.5 mM (hybrid with W573F) respectively. (C) Illustration of possible complementation in the reconstitution assay. Exchange of catalytic subunits between wild-type (Wt) and mutant (Mut.) AHASs at the C-terminus yields the hybrid dimer which have one normal active site (A1) and one defective active site (A2) because a single active site is formed by different polypeptides of two subunits (α-domain of monomer A, β-domain of monomer B and γ-domain of monomer B) and it is postulated to be covered by the two mobile regions of monomer B (mobile loop and C-terminal lid), the regions of which are deleted in Δ567–582 and Δ630 respectively. Therefore, in the case of reconstitution with deletion mutants, the hybrids have only one ‘normal’ active site consisting of a C-terminus from wild-type and others from the indicated mutant. However, in the reconstitution with W573F, the hybrid has one ‘normal’ and one ‘altered’ active site consisting of C-terminus including point mutation in Trp573, which is located within the mobile loop, and others from wild-type. This prediction might be supported by the facts that the activity of the hybrid was increased with a higher fold, and that the Km (116 mM) for substrate of hybrid was totally different from those of wild-type (10–15 mM) and W573F mutant (400 mM) respectively.

In contrast with the deletion mutants, the reconstitution assay with a wild-type and the W573F (Trp573→Phe) mutant showed different results. The point mutation of Trp573 to phenylalanine was reported to reduce activity (approx. 1/4 of the specific activity) and to have a high substrate Km value of 400 mM [26]. When mutant W573F was mixed with the wild-type, the hybrid dimer showed higher activity than the sum of activities of both enzymes and the increase was more than 2-fold. Also, the hybrid enzyme Km for substrate was increased (115.9±16.5 mM), implying the existence of an altered active site within the hybrid enzymes. These results were explained by the illustration in Figure 5(C).

The effects of deletions on cofactor activation

We have examined the effects of the deletion mutant on cofactor activation. Removal of the cofactors FAD and ThDP abolished the activity, and activity was restored by the addition of each cofactor (results not shown). The dependence of activities on each cofactor was determined and is summarized in Table 2. When the enzyme assay was performed in a mixture containing cofactors at higher concentrations (20 mM ThDP or 1 mM FAD) than in the standard conditions (1 mM ThDP and 20 μM FAD), there was no significant increase of enzyme activity in the wild-type enzyme. However, the deletion mutants led to a significant change in ThDP-dependent activity, more than 6-fold, whereas there were minimal changes in the activities of mutants with higher concentrations of FAD. To address the effects of these two regions on ThDP in the enzyme reaction, we determined the kinetic parameters of enzyme with this cofactor. The dependence of activity on the concentration of cofactor can be used to calculate a cofactor activation constant (Kc) that is an approximate measure of the affinity of the enzyme for the cofactor. For the wild-type AHAS, Kc for ThDP was 0.39±0.03 mM at saturating concentrations of other cofactors, whereas the Kc of each mutant was increased, more than 40-fold, 17.20±2.28 mM for Δ567–582 and 16.10±1.73 mM for Δ630. These results suggest that these two regions are involved in binding and/or stabilization of ThDP in the active site of the enzyme.

Table 2. The effects of deletions on cofactor activation.

Enzyme assay was performed in 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, and 100 mM pyruvate, with various cofactor mixtures, including the saturating concentration of cofactor mixture (1 mM ThDP, 20 μM FAD and 10 mM MgCl2) as a standard. Indicated conditions represent varied cofactor concentrations with saturating concentration of others. Enzymes were pre-incubated in the buffer at 37 °C for 15 min, and the reaction was initiated by the addition of substrate, 100 mM pyruvate.

| Conditions | Specific activity (units/mg of protein) | Kc for ThDP* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type AHAS | Standard | 1.73 | 0.39±0.03 mM |

| 20 mM ThDP | 2.11 | ||

| 1 mM FAD | 1.70 | ||

| 20 mM ThDP+1 mM FAD | 2.17 | ||

| Δ630 | Standard | 0.068 | 16.10±1.73 mM |

| 20 mM ThDP | 0.58 | ||

| 1 mM FAD | 0.058 | ||

| 20 mM ThDP+1 mM FAD | 0.57 | ||

| Δ567–582 | Standard | 0.063 | 17.2±2.28 mM |

| 20 mM ThDP | 0.45 | ||

| 1 mM FAD | 0.063 | ||

| 20 mM ThDP+1 mM FAD | 0.44 |

* The activation constant (Kc) of ThDP was determined as a function of ThDP concentration. The data were collected and processed using the Hill equation. All fitted data were from the mean for three independent experiments.

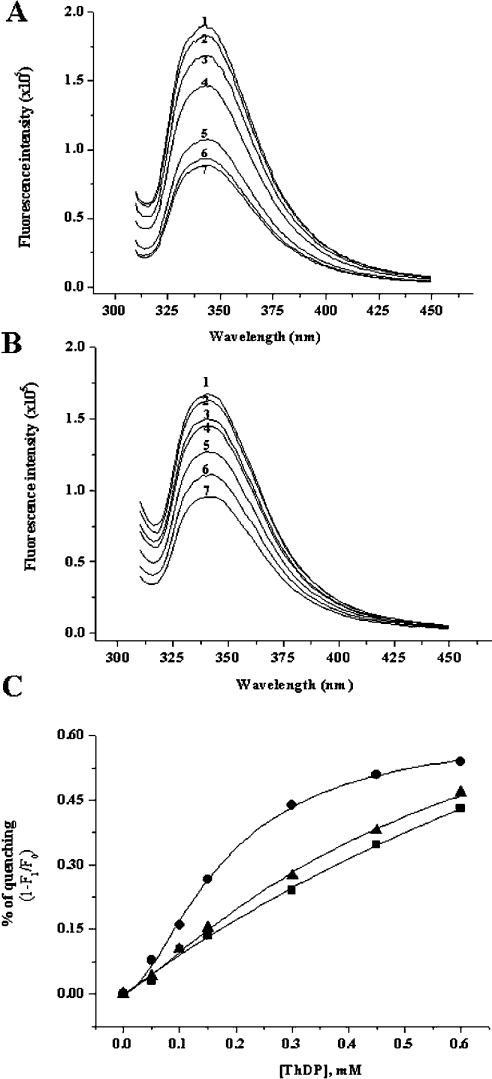

To confirm the binding of ThDP to enzyme, Kds were determined from the quenching of intrinsic fluorescence. The fluorescence-quenching experiment was performed by titrating ThDP into a mixture of apoenzyme in the presence of 100 mM phosphate, pH 7.4, 2 mM Mg2+ and 20 μM FAD. The enzyme exhibits a fluorescence emission maximum at 340–345 nm upon excitation at 300 nm (Figure 6A), which might correspond to a buried tryptophan in AHAS. The quenching of apo-AHAS fluorescence by ThDP was concentration-dependent and saturable, following a typical hyperbolic binding curve. However, the deletion mutants showed a different binding pattern (Figure 6B). Although the fluorescence quenching of the deletion mutants by ThDP is concentration-dependent, their binding curves are not saturated at the tested concentrations (Figure 6C). In the theoretical calculations from extrapolative curve fitting, the Kd of each mutant was 0.58 mM for Δ630 and 0.69 mM for Δ567–582, whereas that of wild-type was 0.18 mM. This result supported that these two regions play important roles in ThDP binding to enzyme.

Figure 6. Effects of ThDP on the fluorescence emission spectrum of wild-type AHAS and deletion mutant (Δ630).

Each enzyme [0.1 mg/ml of wild-type AHAS, (A); the same concentration of Δ630, (B)] was pre-incubated with a buffer containing 100 mM Mops, pH 7.5, and 20 μM FAD in the presence of 2 mM MgCl2, and then the following concentrations of ThDP were added: 0 (1), 0.05 (2), 0.1 (3), 0.15 (4), 0.3 (5), 0.45 (6) and 0.6 (7) mM. The wavelength of excitation was 300 nm and the emission spectra were recorded in the range 310–450 nm. Emission maximum was around 340 nm. The emission spectrum of the internal deletion mutant (Δ567–582) was similar to that of Δ630 (results not shown). (C) Fluorescence-quenching plot of wild-type and deletion mutants. Plots show the dependence of the fluorescence decrease, 1-(F1/F0), where F0 is the fluorescence intensity in the absence of ThDP and F1 is the fluorescence intensity in the presence of the indicated concentration of ThDP (•, wild-type; ▴, Δ630; ▪, Δ567–582).

DISCUSSION

Efforts to identify the regions or residues corresponding to cofactor binding and herbicide sensitivity have been concentrated on AHAS studies [1,7,11,20,25,27,28]. Among these, the requirement of ThDP as a central reaction centre provides deep insight into the understanding of the reaction mechanism, residues related to catalysis [29] and the structure of AHAS, in comparison with other well-known ThDP-dependent enzymes, such as BFDC [16], POX [17] and PDC [18]. On the basis of this information, biochemical approaches have identified the chemical mechanism and the role of ThDP in AHAS-catalysed reactions [1,27]. Furthermore, the recent reports of the three-dimensional structure of yeast AHAS showed the location of several active-site features, including the position and conformation of the cofactors ThDP, Mg2+ and FAD, and proposed a model for a substrate-access channel at the interface of the two subunits [14,15]. In this structure, the existence of two invisible (disordered) regions in free enzyme (these regions showed different conformations in the enzyme–inhibitor complex) is quite noticeable because of possible involvement in the enzyme reaction. The first of these flexible regions are residues 580–595 (mobile loop) and another disordered region includes the last 40 residues of yeast AHAS (C-terminal lid). An alignment of the C-terminal regions for ThDP-dependent enzymes is shown in Figure 1. There is a high degree of sequence identity in the overall sequences, with two regions indicated by bars beneath the sequences in Figure 1, which are putatively, highly flexible regions in this enzyme family.

In the present study, we investigated the role of these two disordered regions using two deletion mutants, Δ630 (without the C-terminal lid) and Δ567–582 (without the mobile loop). As suggested by the structure from crystal analysis, these mutants showed greatly reduced activities. From our results, we provide the following explanations.

The first effect of deletion mutants is a stabilization of the quaternary structure of active enzyme which consists of two subunits. Our results show that native tobacco AHAS favours more than a dimer, which was represented as a fast, single elution profile in gel-filtration experiments. This is in line with previous studies of AHAS from several sources [1,8,30]. The constant specific activity at varying concentrations of enzyme supports this result further. In addition, our results also show that there is a dynamic equilibrium for the formation of active enzyme. The theoretical Kd, from the measurement of specific activity at low concentration of enzyme, was approx. 15 nM. In the concentration range 1–5 μM, a single peak containing wild-type AHAS was obtained at a position corresponding to more than a dimer form in gel-filtration experiments. However, the elution profiles for deletion mutants were different from that of wild-type enzyme. At a concentration of 1 μM, another peak (beside a major peak) containing mutant enzyme was observed at a position which overlapped with the BSA peak. These peaks gradually decreased as the enzyme concentration was increased, while the peaks representing the dimer form (or more) were increased. This result implies that these regions have a role in the stabilization of active dimer (or more) formation, rather than in the critical determination of subunit interaction. This result is supported by the structural data of yeast AHAS [14,15]. In its structure, residues 653–666 of the C-terminal lid reach across from the γ-domain and attach to the β-domain, suggesting possible involvement in the native structure of the enzyme. This is a unique feature of AHAS. The C-terminal lid does not have an equivalent in the closely related ThDP-dependent enzymes, POX, PDC and BFDC. All sequences have an α-helix near the C-terminus, but none of them has the extended loop reaching across to interact with the β-domain [16–18]. However, residues Leu636 (corresponding to yeast Leu641), Pro648 (yeast Pro653), Gly653 (yeast Gly658) and Asp658 (yeast Glu663) of tobacco AHAS are well-conserved amino acids in a wide spectrum of AHASs [1].

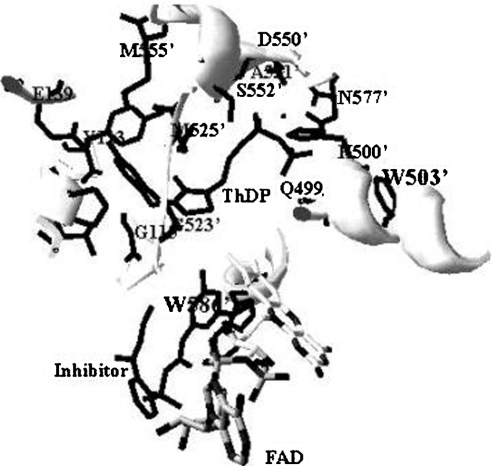

The second role of these regions is related to the affinity of the enzyme for its essential cofactor, ThDP. The loss of activity is in part due to the impairment of ThDP binding to the enzyme. The data for the Kc for ThDP and fluorescence quenching clearly showed the effect of deletions on ThDP binding to the enzymes. Given that the Kc is related to the affinity of the enzyme for a cofactor, the higher Kc (approx. 40-fold) of each deletion mutant demonstrates large decreases in affinity for ThDP. Also, the fluorescence-quenching experiment supported this result. It has been extensively documented that binding of ThDP to enzyme, such as PDC and PDH [3,31,32], quenches the tryptophan fluorescence, suggesting that there is a tryptophan(s) in the ThDP-binding site (active site). However, there is little documentation on the fluorescence quenching of AHAS upon ThDP binding. Based on the X-ray crystal co-ordinate (Protein Data Bank code 1N0H) of yeast AHAS, we analysed the environment of the active site centred at ThDP (Figure 7). In this structural model, two possible tryptophan residues (Trp503′ and Trp586′) are observed within 5 Å (1 Å=0.1 nm) of ThDP. Given that Trp586′ is not visible in the crystallography of free enzyme without the inhibitor, Trp503′ (corresponding to tobacco AHAS Trp490) can be postulated to be involved in fluorescence quenching with ThDP. The W573F mutant of tobacco AHAS (Trp586 of yeast AHAS) also showed intrinsic fluorescence quenching with ThDP (results not shown). The emission maximum of tryptophan in water is highly dependent upon polarity, which causes the shift-emission ranging from 310 to 350 nm [31,33]. The fluorescence emission maximum of the deletion mutants (Δ630 and Δ567–582) is slightly red-shifted (approx. 3–5 nm) compared with that of wild-type AHAS upon excitation at 300 nm, implying that subtle conformational changes bring the tryptophan residue(s) into a less non-polar (more solvent-accessible) environment. Assuming that these two regions (mobile loop and C-terminal lid) are involved in ThDP binding (or stabilization) to enzyme, these missing interactions might be the main reason why ThDP binding on the deletion mutants (Δ630 and Δ567–582) is more exposed to solvent as compared with wild-type AHAS. Although it remains to be characterized which amino acid is involved in ThDP binding, our results suggest strongly that the regions of these two deletion mutants participate in ThDP binding to the enzyme.

Figure 7. Structural representation of the ThDP-binding site.

The active site centred at ThDP was modelled by a SwissProt database program using the X-ray co-ordinates of yeast AHAS (Protein Data Bank code 1N0H). The three-dimensional structure represented here was constructed with the inhibitor, chlorimuron ethyl. Trp586′ was shown only when inhibitor was added to the crystal formation. Trp503′ and Trp586′ correspond to residues Trp490 and Trp573 of tobacco AHAS respectively. Protein side chains close to ThDP or within 5 Å to the likely position of active sites are shown, with residues from the domain of one subunit designated as a number and those from the other subunit as a primed number.

Finally, the deletions result in drastic decreases in kcat with little effect on Km for substrate. Furthermore, the substantial differences between the Kc for ThDP (17.20±2.28 mM for Δ567–582 and 16.10±1.73 mM for Δ630) and the direct Kd (0.69 mM for Δ567–582 and 0.58 mM for Δ630) support the hypothesis of closure of the active site containing ThDP by these two deleted regions. Many lines of evidence have suggested that the active site of ThDP-dependent enzymes is inaccessible to solvent-derived protons during catalysis [34–36], which is in line with reports that a hydrophobic environment is required for the decarboxylation step in the reaction [37–39]. Modelling and kinetic studies agree with the proposal of a cyclic opening and closing of the active site during catalysis [40,41]. In addition, in the structure of the yeast AHAS–inhibitor complex, there is an important observation that the regions consisting of the 38 C-terminal amino acid residues 650–687 (corresponding to residues 645–669 of tobacco, C-terminal lid) and the polypeptide segment consisting of amino acid 580–595 (residues 567–582 of tobacco, mobile loop) become ordered, further restricting solvent accessibility to the active site [14].

The functional domain study should be carefully examined. There is a possibility that the deletion mutagenesis causes profound structural changes and denaturation of the overall structure of the proteins. They could interfere with and complicate the interpretation of our observations. However, it is reasonable to assume that the constructed variants folded into similar conformation in the absence of indicated regions, consistent with the finding that mutants are able to bind the cofactors, and exhibit varying levels of activity. Also, the observation of the same elution profiles in gel filtration compared with native enzyme could not be explained by an overall structural change or denaturation of the protein. Furthermore, three-dimensional modelling showed that the three domains (α, β and γ-domain) of AHAS were folded independently [14,15], and that the deleted regions are disordered and flexible. Although the crystal structure of yeast AHAS suggested that access to the active site is impeded by these two regions, it is possible that the structure of the enzyme in solution is slightly different from that in the crystal structure, and that the structure of our investigated model, tobacco, is not related to that of yeast.

We are now attempting to obtain more evidence for movement of these regions of AHAS during catalysis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Korean Research Foundation Grant (KRF-2002-070-C00064). We are grateful to Dr Ronald G. Duggleby (Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia) for helpful discussions and comments. We also thank Dr William Atkins and Michael Dabrowski (Department of Medicinal Chemistry, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, U.S.A.) for correction and advice on the manuscript prior to submission.

References

- 1.Duggleby R. G., Pang S. S. Acetohydroxyacid synthase. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2000;33:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chipman D., Barak Z., Schloss J. V. Biosynthesis of 2-aceto-2-hydroxy acids: acetolactate synthases and acetohydroxyacid synthases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1385:401–419. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(98)00083-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jordan F., Nemeria N., Guo F., Baburina I., Gao Y., Kahyaoglu A., Li H., Wang J., Yi J., Guest J. R., Furey W. Regulation of thiamin diphosphate-dependent 2-oxo acid decarboxylases by substrate and thiamin diphosphate. Mg(II) – evidence for tertiary and quaternary interactions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1385:287–306. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(98)00075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaner D. L., Anderson P. C., Stidham M. A. Imidazolinones: potent inhibitors of acetohydroxyacid synthase. Plant Physiol. 1984;76:545–546. doi: 10.1104/pp.76.2.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Durner J., Boger P. New aspects on inhibition of plant acetolactate synthase by chlorosulfuron and imazaquin. Plant Physiol. 1991;95:1144–1149. doi: 10.1104/pp.95.4.1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang A. K., Duggleby R. G. Herbicide-resistant forms of Arabidopsis thaliana acetohydroxyacid synthase: characterization of the catalytic properties and sensitivity to inhibitors of four defined mutants. Biochem. J. 1998;333:765–777. doi: 10.1042/bj3330765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee Y. T., Duggleby R. G. Mutagenesis studies on the sensitivity of Escherichia coli acetohydroxyacid synthase II to herbicides and valine. Biochem. J. 2000;350:69–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hershey H. P., Schwartz L. J., Gale J. P., Abell L. M. Cloning and functional expression of small subunit of acetolactate synthase from Nicotiana plumbaginifolia. Plant Mol. Biol. 1999;40:795–806. doi: 10.1023/a:1006273224977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee Y. T., Duggleby R. G. Identification of the regulatory subunit of Arabidopsis thaliana acetohydroxyacid synthase and reconstitution with its catalytic subunit. Biochemistry. 2001;40:6836–6844. doi: 10.1021/bi002775q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sella C., Weinstock O., Barak Z., Chipman D. M. Subunit association in acetohydroxy acid synthase isozyme III. J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:5339–5343. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.17.5339-5343.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vyazmensky M., Sella C., Barak Z., Chipman D. M. Isolation and characterization of subunits of acetohydroxy acid synthase isozyme III and reconstitution of the holoenzyme. Biochemistry. 1996;35:10339–10346. doi: 10.1021/bi9605604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill C. M., Pang S. S., Duggleby R. G. Purification of Escherichia coli acetohydroxyacid synthase isoenzyme II and reconstitution of active enzyme from its individual pure subunits. Biochem. J. 1997;327:891–898. doi: 10.1042/bj3270891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weinstock O., Sella C., Chipman D. M., Barak Z. Properties of subcloned subunits of bacterial acetohydroxy acid synthases. J. Bacteriol. 1992;174:5560–5566. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.17.5560-5566.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pang S. S., Duggleby R. G., Guddat L. W. Crystal structure of yeast acetohydroxyacid synthase: a target for herbicidal inhibitors. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;317:249–262. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pang S. S., Guddat L. W., Duggleby R. G. Molecular basis of sulfonylurea herbicide inhibition of acetohydroxyacid synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:7639–7644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211648200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasson M. S., Muscate A., McLeish M. J., Polovnikova L. S., Gerlt J. A., Kenyon G. L., Petsko G. A., Ringe D. The crystal structure of benzoylformate decarboxylase at 1.6 Å resolution: diversity of catalytic residues in thiamin diphosphate-dependent enzymes. Biochemistry. 1998;37:9918–9930. doi: 10.1021/bi973047e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muller Y. A., Schulz G. E. Structure of the thiamine- and flavin-dependent enzyme pyruvate oxidase. Science. 1993;259:965–967. doi: 10.1126/science.8438155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dobritzsch D., Konig S., Schneider G., Lu G. High resolution crystal structure of pyruvate decarboxylase from Zymomonas mobilis: implications for substrate activation in pyruvate decarboxylases. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:20196–20204. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang A. K., Nixon P. F., Duggleby R. G. Effects of deletions at the carboxyl terminus of Zymomonas mobilis pyruvate decarboxylase on the kinetic properties and substrate specificity. Biochemistry. 2000;39:9430–9437. doi: 10.1021/bi0002683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ibdah M., Bar-Ilan A., Livnah O., Schloss J. V., Barak Z., Chipman D. M. Homology modeling of the structure of bacterial acetohydroxy acid synthase and examination of the active site by site-directed mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 1996;35:16282–16291. doi: 10.1021/bi961588i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Westerfeld W. W. A colorimetric determination of blood acetoin. J. Biol. Chem. 1945;161:495–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cleland W. W. Statistical analysis of enzyme kinetic data. Methods Enzymol. 1979;63:103–138. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)63008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chong C. K., Choi J. D. Amino acid residues conferring herbicide tolerance in tobacco acetolactate synthase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;279:462–427. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang S. I., Kang M. K., Choi J. D., Namgoong S. K. Soluble overexpression in Escherichia coli, and purification and characterization of wild-type recombinant tobacco acetolactate synthase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;234:549–553. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoon M. Y., Hwang J. H., Choi M. K., Baek D. K., Kim J., Kim Y. T., Choi J. D. The active site and mechanism of action of recombinant acetohydroxy acid synthase from tobacco. FEBS Lett. 2003;555:185–191. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01177-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chong C. K., Shin H. J., Chang S. I., Choi J. D. Role of tryptophanyl residues in tobacco acetolactate synthase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;259:136–140. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bar-Ilan A., Balan V., Tittmann K., Golbik R., Vyazmensky M., Hubner G., Barak Z., Chipman D. M. Binding and activation of thiamin diphosphate in acetohydroxyacid synthase. Biochemistry. 2001;40:11946–11954. doi: 10.1021/bi0104524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gollop N., Damri B., Barak Z., Chipman D. M. Kinetics and mechanism of acetohydroxyacid synthase isozyme III from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1989;28:6310–6317. doi: 10.1021/bi00441a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Candy J. M., Duggleby R. G. Investigation of the cofactor-binding site of Zymomonas mobilis pyruvate decarboxylase by site-directed mutagenesis. Biochem. J. 1994;300:7–13. doi: 10.1042/bj3000007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pang S. S., Duggleby R. G. Expression, purification, characterization, and reconstitution of the large and small subunits of yeast acetohydroxyacid synthase. Biochemistry. 1999;38:5222–5231. doi: 10.1021/bi983013m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li H., Furey W., Jordan F. Role of glutamate 91 in information transfer during substrate activation of yeast pyruvate decarboxylase. Biochemistry. 1999;38:9992–10003. doi: 10.1021/bi9902438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hawkins C. F., Borges A., Perham R. N. A common structural motif in thiamin pyrophosphate-binding enzymes. FEBS Lett. 1989;255:77–82. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lakowicz J. R. 2nd edn. New York: Kluwer Academic; 1999. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu M., Sergienko E. A., Guo F., Wang J., Tittmann K., Hubner G., Furey W., Jordan F. Catalytic acid-base groups in yeast pyruvate decarboxylase. 1. Site-directed mutagenesis and steady-state kinetic studies on the enzyme with the D28A, H114F, and E477Q substitutions. Biochemistry. 2001;40:7355–7368. doi: 10.1021/bi002855u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sergienko E. A., Jordan F. Catalytic acid-base groups in yeast pyruvate decarboxylase. 2. Insights into the specific roles of D28 and E477 from the rates and stereospecificity of formation of carboligase side products. Biochemistry. 2001;40:7369–7381. doi: 10.1021/bi002856m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jordan F., Akinyosoye O., Dikada G., Kudzin Z. H., Kuo D. J. In: Thiamin Pyrophosphate Biochemistry, vol. 1. Schowen R. L., Schellenberger A., editors. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1988. pp. 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ermer J., Schellenberger A., Hubner G. Kinetic mechanism of pyruvate decarboxylase. Evidence for a specific protonation of the enzymic intermediate. FEBS Lett. 1992;299:163–165. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80238-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harris T. K., Washabaugh M. W. Solvent-derived protons in catalysis by brewers' yeast pyruvate decarboxylase. Biochemistry. 1995;34:14001–14011. doi: 10.1021/bi00043a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dyda F., Furey W., Swaminathan S., Sax M., Farrenkopf B., Jordan F. Catalytic centers in the thiamin diphosphate dependent enzyme pyruvate decarboxylase at 2.4 Å resolution. Biochemistry. 1993;32:6165–6170. doi: 10.1021/bi00075a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lobell M., Crout D. H. G. Pyruvate decarboxylase: a molecular modeling study of pyruvate decarboxylation and acyloin formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:1867–1873. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alvarez F. J., Ermer J., Huebner G., Schellenberger A., Schowen R. L. The linkage of catalysis and regulation in enzyme action: solvent isotope effects as probes of protonic sites in the yeast pyruvate decarboxylase mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:1678–1683. [Google Scholar]