Abstract

Mouse models of experimental autoimmune uveitis (EAU) mimic unique features of human uveitis, and serve as a template for preclinical study. The “classical” EAU model is induced by active immunization of mice with the retinal protein IRBP in adjuvant, and has proved to be a useful tool to study basic mechanisms and novel therapy in human uveitis. Several spontaneous models of uveitis induced by autoreactive T cells targeting on IRBP have been recently developed in IRBP specific TCR transgenic mice (R161H) and in AIRE−/− mice. The “classical” immunization-induced EAU exhibits acute ocular inflammation with two distinct patterns: (i) severe monophasic form with extensive destruction of the retina and rapid loss of visual function, and (ii) lower grade form with an acute onset followed by a prolonged chronic phase of disease. The spontaneous models of uveitis in R161H and AIRE−/− mice have a gradual onset and develop chronic ocular inflammation that ultimately leads to retinal degeneration, along with a progressive decline of visual signal. The adjuvant-dependent model and adjuvant-free spontaneous models represent distinct aspects and/or various forms of human uveitis. This review will discuss and compare clinical manifestations, pathology as well as visual function of the retina in the different models of uveitis, as measured by fundus imaging and histology, optical coherence tomography (OCT) and electroretinography (ERG).

Keywords: Electroretinography, histology, experimental autoimmune uveitis, mice, optical coherence tomography, Uveitis

INTRODUCTION

Uveitis is a general term of an inflammation of the retina and uvea consisting of the iris, ciliary body, and choroid. As one of the leading causes of vision impairment in the developed world, uveitis is estimated to account for 10 to 15% of severe vision handicap in the Western world [1,2]. Uveitis is categorized on an anatomical basis as anterior, intermediate, posterior, or panuveitis in association with or without systemic immunological disorders. The etiology and pathogenesis are not fully identified, and noninfectious uveitis is believed to be autoimmune or immune-mediated [2,3]. Human autoimmune uveitis involves a range of intraocular inflammatory diseases, such as undifferentiated uveitis, birdshot chorioretinopathy and sympathetic ophthalmia, sarcoidosis, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease and Behçet’s disease. Many uveitic diseases show strong associations with particular human leukocyte antigen (HLA) haplotypes [4]. Improvement of disease is typically seen in patients treated with T cell targeting agents, such as CsA, rapamycin and anti-IL-2 receptor antibodies (daclizumab).

Experimental autoimmune uveitis (EAU) [5] has been developed as a template for the preclinical studies. EAU can be induced in mice [6] and in rats [7] by active immunization with retinal antigens recognized by lymphocytes of uveitis patients, such as interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein (IRBP) and retinal soluble (S) antigen. The “classical” model of EAU, induced by immunization with IRBP in complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA), is mainly characterized by retinal and/or choroidal inflammation, retinal vasculitis, photoreceptor destruction and loss of visional function [8], that represent many clinico-pathological features of posterior uveitis and/or panuveitis in human [9]. Over the years, the “classical” EAU model has proved to be a useful tool to study basic mechanisms and therapeutic strategies in human uveitis. However, in order to induce EAU with high incidence, use of CFA and (in some strains) pertussis toxin is required, which strongly enhances innate immune response and affects the adaptive immunity that is induced.

To avoid the use of immunization and the side effect of strong adjuvants, an adjuvant-free spontaneous model of uveitis in IRBP T cell receptor by our group [10]. R161H mice express a transgenic TCR specific to the retinal antigen IRBP161–180, and spontaneous uveitis is induced at an early age by a high frequency of autoreactive T cells specific to IRBP161–180 in the peripheral repertoire. In addition to R161H mice, spontaneous uveitis develops in mice deficient in the AutoImmune Regulator (AIRE) gene [11], which controls expression of tissue-specific antigens in the thymus (e.g., IRBP and S-antigen), culling the highly uveitogenic T cells from the repertoire. AIRE−/− mice develop a multi-organ disorder that resembles human autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy (APECED), which also includes uveoretinitis [11,12]. It is of note that uveitis in AIRE−/− mice targets the IRBP antigen, as mice deficient in IRBP fail to develop retinal disease [13]. The mode of disease induction and the site of pathology in these three models of EAU are summarized in Table 1. Therefore, a common platform for comparison is present in all three models on the genetically identified strain B10.RIII, targeting on the same retinal antigen IRBP.

Table 1.

Mouse models of uveitis targeting on IRBP in B10.RIII mice.

| Model | Antigen or Mode of Induction | Main Site of Pathology | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CFA-EAU | Active immunization with IRBP161–180 in CFA | Posterior uveitis, transient anterior uveitis | [14,15] |

| R161H (Tg) | High proportion of autoreactive T cells specific to IRBP161–180 | Posterior uveitis, minimal anterior uveitis | [10,14] |

| AIRE−/− | Defect in negative selection of autoreactive T cells; IRBP-dependent uveitis | Multi-organ disease, posterior uveitis | [13] |

In this review, the clinical manifestations, pathology as well as visual function of the retina will be compared among the three induced and spontaneous models of uveitis, using a series of methods including fundoscopy, Micron-II fundus imaging, Bioptigen Envisu R2200 ultra-high resolution optical coherence tomography (OCT) system as well as electroretinography (ERG) in comparison with histology.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATION IN INDUCED AND SPONTANEOUS MODELS OF UVEITIS

Comparison of Disease Course and Severity in Three Mouse Models of EAU

Disease severity as well as clinical course were evaluated using fundus imaging and fundoscopy in these three models of uveitis, the “classical” adjuvant-induced model of EAU, spontaneous uveitis developed in R161H mice, and spontaneous uveitis developing in AIRE−/− mice (Fig. 1). In the adjuvant-induced model, onset of EAU occurred 11–13 days post immunization (p.i.) and peaked on day 14. Two distinct patterns of disease progression were observed: monophasic and chronic, depending on the severity of the initial acute phase of retinal inflammation. In the monophasic form, mice that developed EAU with clinical scores higher than two manifested perivascular exudates, subretinal hemorrhage and retinal folds at the acute phase of inflammation. Active inflammation resolved rapidly, and progressed sharply into retinal degeneration phase around 4–5 weeks p.i. In the chronic form of EAU induced with lower dose of IRBP peptides, following the initial phase of acute inflammation (2–3 weeks p.i.), mice with disease scores of 2 or less exhibited prolonged inflammation, characterized by as persistent white granulomatous-like lesions and perivascular cuffing that continued for 5–6 months until retinal degeneration occurred [14].

Fig. (1).

Comparison of disease severity and course in induced and spontaneous uveitis models. EAU was induced in B10R.III mice by immunization with IRBP161–180 in adjuvant. R161H and AIRE−/− mice spontaneously developed uveitis. A, Retinal images obtained by fundus photography at different phase of disease in three models of uveitis. Fundus photographs shown is the chronic form of induced EAU. B, Clinical scores evaluated using an adapted fundus microscope at different stage of disease. EAU induced by immunization with IRBP in adjuvant (a, n=17); spontaneous uveitis seen in R161H (b, n=16) and AIRE−/− mice (c, n=21). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Figure modified from reference [14].

R161H mice spontaneously developed chronic-progressive ocular inflammation, with an early onset of disease at 5–6 weeks of age. Ocular inflammation manifested as persistent and aggressive cell infiltrates in the vitreous, and large-size pearl-like perivascular lesions in the retina. Spontaneous uveitis reached a peak at 8–10 weeks of age when mice gradually initiated to develop secondary cataracts, essentially precluding further follow up by fundus examination beyond week 14. Similarly to R161H mice, AIRE−/− mice spontaneously developed chronic-progressive ocular inflammation at 5–6 weeks of age. However, unlike the lesions in R161H mice, AIRE−/− mice exhibited small-size, snowball-like multifocal lesions in the retina and choroid, that progressively led to retinal degeneration at 10–14 weeks of age. No cataracts were formed in AIRE−/− mice during the course of study [14].

Comparison of Disease Activity

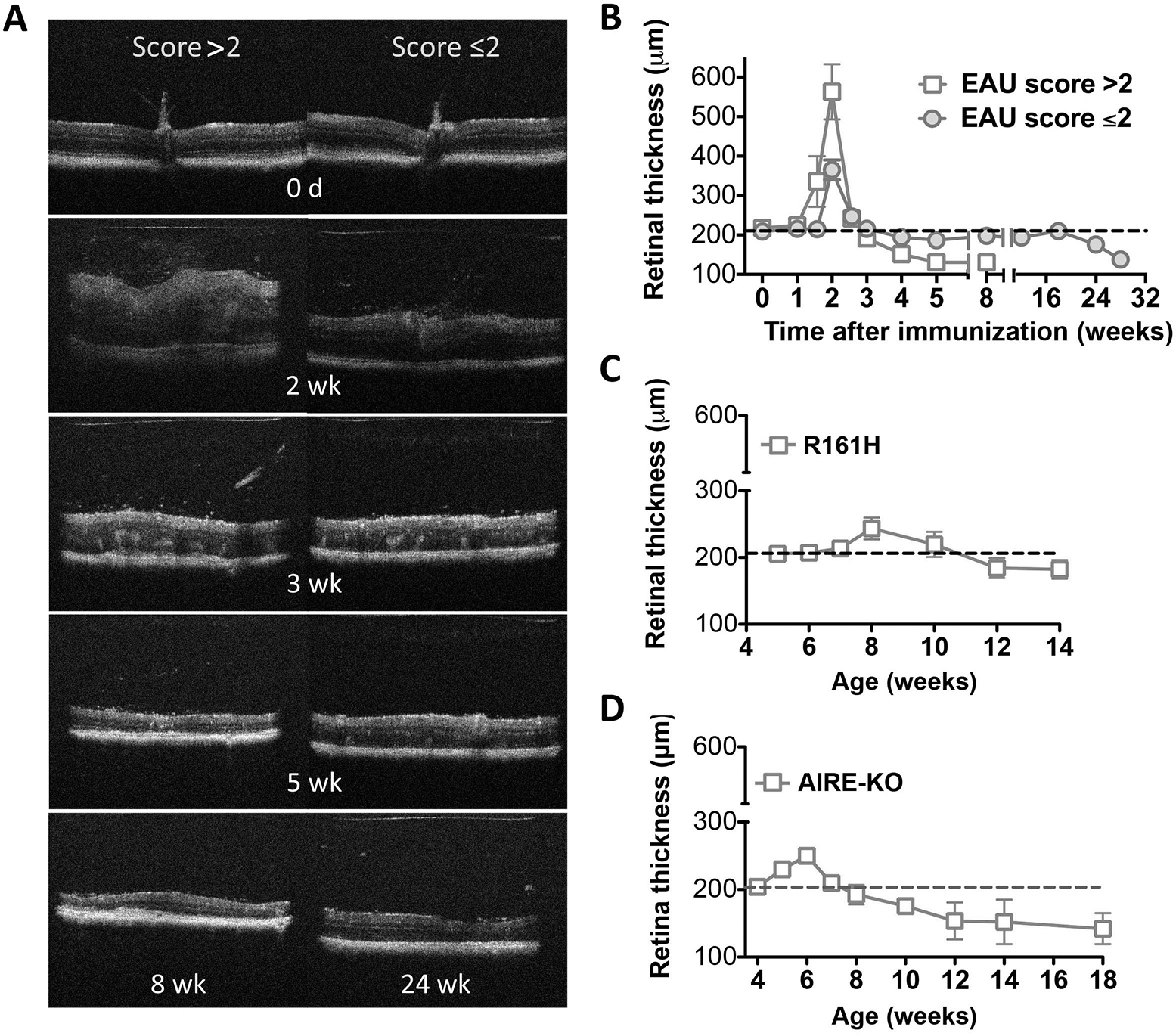

The assessment of retinal thickness using B-scan OCT imaging could be used as a parameter for evaluation of disease activity [15]. We compared the disease activity between the induced and spontaneous models of uveitis (Fig. 2). In the monophasic form of induced EAU, retinal thickness exhibited a 2-fold increase 14 days p.i., which corresponded well to the peak of retinal inflammation as detected by EAU scoring, and followed by a sharp decline of retinal thickness weeks p.i. Active inflammation ended around 4–5 weeks, retinal degeneration and thinning along with destruction of photoreceptor layer (PRL) appeared, with retinal thickness of only about half of the normal baseline. Alternately, in the chronic form of EAU, mice that initially developed less disease with EAU scores of 2 or less exhibited prolonged retinal inflammation lasting several months after the acute phase. No increase in retinal thickness was detected during the onset of disease. The thickness of the retina was increased approximately 1-fold at the peak of inflammation, rapidly recovered and retained to the normal level of baseline for several months. Thinning of the retina (destruction of PRL) occurred after 5–6 months [14]. In both forms of induced EAU, the increase of retinal thickness correlated well with the active inflammation as detected by EAU scoring (Fig. 1).

Fig. (2).

Comparison of retinal thickness in induced and spontaneous models of uveitis. B-scan OCT of the retina was evaluated at the indicated time points using a Bioptigen SD-OCT imaging system, and retinal thickness was measured and averaged from OCT images of the retina. EAU induced by immunization with IRBP in adjuvant (A-B); spontaneous uveitis seen in R161H (C) and AIRE−/− mice (D). Data are presented as mean ± SEM of 17 mice from two individual experiments (A-B) and 16–21 mice from two to three individual experiments (C-D). Figure reprinted from reference [14].

In contrast to the induced model of EAU, the spontaneous models of uveitis seen in R161H and AIRE−/− mice manifested relatively chronic progressive inflammation, with a mild increase of retinal thickness around 6–8 weeks of age. After the active inflammation, a decline of retinal thickness beyond the normal baseline was detected, indicating the phase of retinal degeneration occurred. R161H mice developed secondary cataracts around 12–14 weeks of age that precluded further OCT examination. In contrast, progressive thinning of the retina (destruction of PRL) over many months was documented in AIRE−/− mice, with decline of retinal thickness about half of the normal baseline detected at the late phase of retinal degeneration [14].

Pattern of Cellular Infiltrates

We assessed cell infiltrates in the vitreous by measurement of OCT signal intensity using ImageJ analysis, and compared the data among the three models of uveitis (Fig. 3). In the monophasic form of induced EAU, massive cell infiltrates were observed in the vitreous during the acute inflammation (2–4 weeks p.i.), and disappeared rapidly around 4–5 weeks. Unlike in the monophasic form, mice that developed the chronic form of EAU exhibited relatively modest cell infiltrates in the vitreous during the initial acute phase of inflammation, and that remained at moderate level until 12 weeks p.i. and receded thereafter [14].

Fig. (3).

Semi-quantitative evaluation of cellular infiltrates in the vitreous of mice with induced and spontaneous models of uveitis. Volume-scan of OCT images was captured in the vitreous at the indicated time points using a Bioptigen SD-OCT imaging system. All images were digitally processed in the same way using Photoshop to equalize background contrast levels. Signal intensity of OCT volume scan was then measured and analyzed using ImageJ analysis. EAU induced by immunization with IRBP in adjuvant (A, n=8); spontaneous uveitis seen in R161H (B, n=8) and AIRE−/− mice (C, n=6). Data are presented as mean ± SEM of percent increase of OCT intensity to normal or WT mice. Figure modified from reference [14].

In R161H mice with spontaneous uveitis, cell infiltrates became apparent in the vitreous as early as 4–5 weeks of age, marking disease onset. The cell infiltrates increased sharply reaching a peak at 8 weeks of age, and then remained at high level until OCT imaging was prevented by the occurrence of secondary cataracts at 14 weeks. Similarly, vitreous cell infiltrates became apparent in AIRE−/− mice during active inflammation around 6 weeks of age, and remained at a moderate level until the end of study [14]. Overall, the peak of cell infiltrates correlated well with the disease activity as assessed by retinal thickness in these three models (Fig. 2).

COMPARATIVE HISTOPATHOLOGY

We next compared the histopathology of the eyes in the induced and spontaneous models of uveitis (Fig. 4). At the peak of monophasic EAU (day 14 p.i.) (Fig. 4a), ocular histology revealed severe retinal destruction, extensive cell infiltrates into the vitreous and retina, subretinal hemorrhage, etc. Shortly after that retinal edema diminished, discrete retinitis, vitreal and subretinal hemorrhage, retinal folding, destruction of PRL in the retina as well as choroiditis were prominent on days 18–21 after immunization (Fig. 4b). Diffuse and rapid retinal degeneration/atrophy was observed shortly afterwards. In the chronic form of EAU there was characteristically less photoreceptor damage. Vitreal hemorrhage and retinal folding with intact PRL was frequently observed 18–21 days after immunization (Fig. 4c), but atrophy was focal and did not set in until 6–7 months [14].

Fig. (4).

Histopathology of induced and spontaneous uveitis models. a-c, Mice were immunized with IRBP in adjuvant and eyes were collected at the indicated days after immunization. Note severe ocular inflammation including vitritis, retinal swelling and destruction, retinal folding and cell infiltrates, subretinal hemorrhage, and choroidal inflammation at the peak of inflammation on day 14 p.i. (a, low magnification). During the acute phase of EAU, 18–21 days after immunization, eye histology showed extensive retinal lesions and infiltrating cells in the choroid, vitreous, as well as subretinal hemorrhage (b, high magnification). Retinal folding was seen in mice that developed the chronic form of EAU (c, high magnification). d-f, Eye histology of R161H mice at different ages. Note cell infiltrates and exudates in the vitreous and in the retina (d-e, low and high magnification), lymphoid aggregation in the retina (f, asterisk), and choroidal inflammation (e-f). g-i, Eye histology of AIRE−/− mice at different ages. Note severe choroiditis (g, low magnification; i, high magnification), granuloma-like lesions in the retina (h-i, low magnification). Figure modified from reference [14].

Chronic/progressive ocular inflammation in R161H mice (Fig. 4d–f), was characterized by focal lymphoid aggregates, monocytic cell infiltrates in the vitreous and retina, accompanied by PRL destruction [14]. Ocular histology of chronic inflammation seen in AIRE−/− mice was characterized by granuloma-like focal lesions in the retina, moderate retinitis and severe choroiditis, along with prominent retinal atrophy at later stages of disease [14] (Fig. 4g–i).

CHANGES IN VISUAL FUNCTION IN INDUCED VS SPONTANEOUS MODELS OF UVEITIS

Visual function of mice in the three models of uveitis was examined using an ERG recording system in the same individual mice whose morphological changes were assessed by OCT, fundus imaging and histology and were depicted in the previous figures. We recorded photopic (light-adapted) ERG response that representing cone-mediated visual signals during the course of the disease (Fig. 5). In the immunization-induced model of EAU, two patterns of ERG responses could be distinguished that corresponded to the monophasic and chronic courses of disease in mice which developed scores >2 or ≤2 in the initial acute phase (Fig. 5A). Following the onset of disease on day 11 p.i., mice destined to develop either monophasic disease or biphasic disease experienced a detectable reduction in b-wave amplitudes measured in light-adapted condition. By day 14 (peak of active inflammation), the amplitudes dropped sharply by 90% and remained flat thereafter in mice developed monophasic form of EAU [14,15]. However, in the biphasic form of EAU with disease score less than 2, resolution of active inflammation was followed by partial recovery of visual function with ERG returning to 50–65% of normal amplitude. The partial restoration of visual function remained for several months, despite the chronic inflammation, and followed by a noticeable decline of ERG when retinal thickness dropped under baseline 6–7 months after immunization [14].

Fig. (5).

Kinetics of light-adapted ERG response in induced and spontaneous uveitis models. Mice that developed induced and spontaneous EAU were monitored and followed up at the indicative time points by ERG. Amplitude of light-adapted ERG was recorded and analyzed in mice developed adjuvant-induced EAU (A) and in R161H (B) and AIRE−/− (C) mice that developed spontaneous uveitis. Data represent the mean ± SEM of 17 mice from two individual experiments (A) and 16–21 mice from two to three individual experiments (B, C). Figure modified from reference [14].

ERG recording was initiated in R161H and AIRE−/− mice that spontaneously developed uveitis and in their wild type (WT) littermates at 4–5 weeks of age. As part of normal postnatal development of the retina, ERG amplitudes measured in WT mice exhibited a downward trend through puberty, to plateau at 7 weeks of age (Figs. 5B and 5C). R161H mice, in which disease developed as early as 4–5 weeks of age, consistently showed reduced ERG amplitudes below WT values. At 8 weeks of age, when the retinal inflammation reached the peak, as assessed by an increase in retinal thickness, a decline of ERG values was detected, which continued progressively and finally plateaued at near zero levels when reduction of retinal thickness became apparent after week 10 (Fig. 5B) [14]. Although AIRE−/− mice initially exhibited ERGs equivalent to WT (up to 5 weeks) the values dipped below WT thereafter. Similar to R161H mice, the ERG values dropped quickly at 8 weeks of age to plateau at a low level after week 10, when appreciable thinning of the retina occurred reflecting permanent deficit in visual function (Fig. 5C) [14]. Overall, in the three models of EAU, the decline of ERG response correlated well with the change of retinal thickness in mice during acute phase of active inflammation as well as retinal degeneration phase.

SUMMARY

Experimental animal models are essential preclinical tools for studying disease pathogenesis and translational immunotherapies. It has frequently been a matter of debate, which model best represents autoimmune uveitis in human. Since human uveitis is heterogeneous, the answer is that all are relevant. In this review, we attempted to compare multiple parameters of disease in three mouse models of uveitis: the “classical” EAU model induced by immunization and two spontaneous models: R161H IRBP TCR transgenic mice and AIRE−/− mice. All three models are on the same B10.RIII background and driven by a T cell mediated response to IRBP. Importantly, disease parameters are assessed in parallel by different morphological and functional criteria in the same individual. A brief summary is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of morphologic and functional changes in induced and spontaneous models of uveitis.

| Model | Onset and Progress of Ocular Inflammation |

| Adjuvant-Induced EAU (Active Immunization) | |

| B10.RIII | • Monophasic & biphasic forms of posterior uveitis; transient anterior uveitis • Onset of disease 11d after immunization • Diffuse retinal lesions; extensive exudates & infiltrates; PRL destruction • Loss of visual signal during acute and retinal degeneration phases |

| Adjuvant-Free Spontaneous Uveitis | |

| R161H (Tg) | • Chronic form of posterior uveitis, minimal anterior chamber involvement • Spontaneous uveitis starts at early age • Focal retinal lesions; persistent cellular infiltrates & aggregates • Loss of visual signal during retinal degeneration phase |

| AIRE−/− | • Chronic form of posterior uveitis • Spontaneous uveitis starts at early age • Small-size, multi-focal retinal lesions, severe choroiditis • Loss of visual signal during retinal degeneration phase |

Table modified from reference [14].

We propose that adjuvant-induced EAU with its rapid onset, explosive development and diffuse pathology could represent acute and subacute forms of human uveitis better than the spontaneous uveitis models. However, the feature of rapid and permanent loss of visual function in mice with the monophasic form of EAU limits its value for therapy studies. In contrast, the adjuvant-free spontaneous models with their relentless chronic and progressive course but more focal type of pathology could more faithfully resemble the chronic types of human uveitis. In addition to the differences in the course of disease, particularly prominent was the anterior chamber involvement in EAU, which was minimal in R161H and absent in AIRE−/− mice. Between R161H and AIRE−/− mice, the main differences were focal retinal lymphoid aggregates in R161H vs prominent choroidal involvement in AIRE−/− mice. R161H pathology thus appears more concentrated in the retina, whereas AIRE−/− pathology targets the choroid as well.

This review uncovers the variability and unique distinguishing features in induced and spontaneous models of uveitis. We emphasize that, although no one single animal model represents the full spectrum of clinical and pathological features of human uveitis, each one can reflect particular aspects of human disease. A better understanding of differences in the clinical and histological manifestations as well as visual function in the “classical” immunization-induced model of EAU and the spontaneous models of uveitis, could guide better choices of animal model(s) for the study of basic mechanisms and therapeutic strategies in human uveitis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the NEI Histology Core Facility for assistance in preparing the histology slides, and the NEI Vision Function Core Facility and the Biological Imaging Care Facility for assistance in providing excellent technical support. The study was supported by NIH/NEI Intramural funding, project # EY000184.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AIRE

Autoimmune regulator

- APECED

Autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy

- CFA

Complete Freund’s adjuvant

- EAU

Experimental autoimmune uveitis

- ERG

Electroretinography

- IRBP

Interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein

- −/−

Knockout

- OCT

Optical coherence tomography

- p.i.

Post-immunization

- PRL

Photoreceptor layer

- R161H

IRBP TCR transgenic mouse

- S

soluble protein

- SD-OCT

spectral domain optical coherence tomography

- TCR

T cell receptor

- WT

wild type

Biography

J. Chen

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

DISCLOSURE

Part of this article has been previously published in PLoS One 8(8): e72161. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0072161.

REFERENCES

- [1].Durrani OM, Meads CA, Murray PI. Uveitis: a potentially blinding disease. Ophthalmologica 2004; 218: 223–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gritz DC, Wong IG. Incidence and prevalence of uveitis in Northern California; the Northern California Epidemiology of Uveitis Study. Ophthalmology 2004; 111: 491–500; discussion 500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Nussenblatt RB WS. Uveitis: fundamentals and clinical practice. Edition r, Editor. Philadelphia: Mosby: (Elsevier; ); 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Caspi RR. A look at autoimmunity and inflammation in the eye. J Clin Invest 2010; 120: 3073–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Caspi RR, Chan CC, Wiggert B, Chader GJ. The mouse as a model of experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis (EAU). Curr Eye Res 1990; 9 Suppl: 169–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Caspi RR, Kuwabara T, Nussenblatt RB. Characterization of a suppressor cell line which downgrades experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis in the rat. J Immunol 1988; 140: 2579–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Caspi RR. A rapid one-step multiwell tray test for release of soluble mediators. J Immunol Methods 1986; 93: 141–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Chan CC, Caspi RR, Ni M, et al. Pathology of experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis in mice. J Autoimmun 1990; 3: 247–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Forrester JV, Liversidge J, Dua HS, Towler H, McMenamin PG. Comparison of clinical and experimental uveitis. Curr Eye Res 1990; 9 Suppl: 75–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Horai R, Silver PB, Chen J, et al. Breakdown of immune privilege and spontaneous autoimmunity in mice expressing a transgenic T cell receptor specific for a retinal autoantigen. J Autoimmun 2013; 44: 21–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].DeVoss J, Hou Y, Johannes K, et al. Spontaneous autoimmunity prevented by thymic expression of a single self-antigen. J Exp Med 2006; 203: 2727–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Jiang W, Anderson MS, Bronson R, Mathis D, Benoist C. Modifier loci condition autoimmunity provoked by Aire deficiency. J Exp Med 2005; 202: 805–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].ESDevoss JJ, Shum AK, Johannes KP, et al. Effector mechanisms of the autoimmune syndrome in the murine model of autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 1. J Immunol 2008; 181: 4072–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chen J, Qian H, Horai R, Chan CC, Falick Y, Caspi RR. Comparative analysis of induced vs spontaneous models of autoimmune uveitis targeting the interphotoreceptor retinoid binding protein. PLoS One 2013; 8: e72161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Chen J, Qian H, Horai R, Chan CC, Caspi RR. Use of optical coherence tomography and electroretinography to evaluate retinal pathology in a mouse model of autoimmune uveitis. PLoS One 2013; 8: e63904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]