Abstract

Helicobacter pylori causes gastritis, peptic ulcer disease and gastric cancer. The microbe is found in the gastric mucus layer where a pH gradient ranging from acidic in the lumen to neutral at the cell surface is maintained. The aim of the present study was to investigate the effects of pH on H. pylori binding to gastric mucins from healthy individuals. At pH 3, all strains bound to the most charged MUC5AC glycoform and to a putative mucin of higher charge and larger size than subunits of MUC5AC and MUC6, irrespective of host blood-group. In contrast, at pH 7.4 only Leb-binding BabA-positive strains bound to Leb-positive MUC5AC and to smaller mucin-like molecules, including MUC1. H. pylori binding to the latter component(s) seems to occur via the H-type-1 structure. All strains bound to a proteoglycan containing chondroitin sulphate/dermatan sulphate side chains at acidic pH, whereas binding to secreted MUC5AC and putative membrane-bound strains occurred both at neutral and acidic pH. The binding properties at acidic pH are thus common to all H. pylori strains, whereas mucin binding at neutral pH occurs via the bacterial BabA adhesin and the Leb antigen/related structures on the glycoprotein. Our work shows that microbe binding to membrane-bound mucins must be considered in H. pylori colonization, and the potential of these glycoproteins to participate in signalling events implies that microbe binding to such structures may initiate signal transduction over the epithelial layer. Competition between microbe binding to membrane-bound and secreted mucins is therefore an important aspect of host–microbe interaction.

Keywords: gastric mucin, glycosylation, Helicobacter pylori, host–pathogen interaction, mucosal protection, pH-dependence

Abbreviations: AlpA, adherence-associated lipoprotein A; AP, alkaline phosphatase; BabA, blood-group antigen-binding adhesin; DNase, deoxyribonuclease I; GdmCl, guanidinium chloride; HRP, horseradish peroxidase; HSA, human serum albumin; mAb, monoclonal antibody; SabA, sialic acid-binding adhesin

INTRODUCTION

The stomach is lined by a viscous mucus layer that acts as a barrier and protects the mucosa against the acidic environment, proteolytic enzymes and mechanical damage. The pH gradient in the unstirred mucus layer ranges from acidic in the lumen to neutral at the cell surface. The mucus gel is formed by high-molecular-mass glycoproteins referred to as mucins. Mucin-type oligosaccharides are structurally very diverse and often display blood-group antigens. The glycan structures present on a mucin reflect the glycosyltransferases expressed by the individual, and the expression pattern is tissue-dependent. In the stomach, MUC5AC and MUC6 constitute the major secreted mucins, the former being produced by the surface epithelium and the latter by the glands [1]. Both these mucins are oligomeric and occur as distinct glycoforms [2]. In Leb-positive individuals, the Leb structure has been shown to appear on the MUC5AC mucin [3]. In addition, the membrane-associated monomeric MUC1 mucin has been identified in the stomach [4].

Helicobacter pylori infection causes gastric and duodenal ulcers and is a risk factor for gastric cancer [5]. The genome of H. pylori codes for a large number of outer membrane proteins [6], and several different adhesins have been implicated in H. pylori binding {e.g. BabA (the blood-group antigen-binding adhesin), SabA (the sialic acid-binding adhesin) and AlpA/B (adherence-associated lipoproteins A and B) [7–10]}. The microbe can be detected attached to the gastric epithelial cells, but the majority are found within the mucus layer [11]. The BabA adhesin recognizes the Leb and H-type-1 structures [12], and in a previous study we showed that binding of H. pylori at neutral pH to human gastric MUC5AC from healthy individuals is both dependent on BabA and mediated by the Leb structure presented by the mucin [3]. Furthermore, the Leb-binding BabA adhesin(s) demonstrated strain-dependent preference in binding to MUC5AC glycoforms substituted with Leb [3]. In Rhesus monkey gastric mucosa, we have shown that H. pylori also binds to a putative membrane-associated mucin [13]. Mucins show variable number of tandem repeats (VNTR) polymorphism, which affects the length of the highly glycosylated mucin domains, and there is an increased frequency of homozygotes for the short allelic form of MUC1 among individuals with H. pylori gastritis [14]. Furthermore, the highly glycosylated extracellular domain (‘ectodomain’) of MUC1 seems to disappear from the luminal gastric surface during H. pylori infection [14]. Proteolytic cleavage and phosphorylation sites in MUC1 suggest that this mucin could play a dynamic role in mucosal defence and participate in signalling events [4,15].

Here, we have characterized the binding of H. pylori to human gastric mucins from healthy individuals at a pH range from 1–7.4 to mimic the pH gradient in the gastric mucus layer. H. pylori binding to mucins differed substantially at the various pHs. At acidic pH, the BabA-dependent binding to H-type-1/Leb was abolished. However, all eight H. pylori strains investigated bound to the most charged MUC5AC glycoform and to a putative ‘novel’ monomeric mucin.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

The bacterial strains, culture conditions and biotinylation procedure, as well as most of the reagents, have been described previously [2,3,13]. Strains 17875/Leb and P466 bind the Leb structure; the 17875BabA1::kanbabA2::cam-mutant (designated babA1A2) and strain CCUG17874 bind the sialyl-Lex structure; and strain P1 expresses the AlpA/B proteins, whereas P1-140 is an AlpA-deletion mutant [7–9]. Deoxyribonuclease 1 (DNase) was from Sigma (St Louis, MO, U.S.A.). Sepharose CL2B and the ECL® detection kit were from Amersham Biosciences (Uppsala, Sweden). Chondroitinase ABC and an mAb (monoclonal antibody) against sialyl-Lex (clone KM93) were obtained from Seikagaku America (Ijamsville, MD, U.S.A.). An mAb recognizing the Leb, BLeb, ALeb and H-type-1 structures [16] (clone 96FR2.10) was from Biotest (Breieich, Germany), and HRP (horseradish peroxidase)-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse antibody from Dako A/S (Copenhagen, Denmark). The mAb against MUC1 (clone 215D4) was developed by Dr J. Hilkens (The Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

Methods

Isolation of mucins

Mucins carrying the carbohydrate determinants summarized in Table 1 were the same as investigated previously [3]. The mucins were purified from human full-thickness gastric wall obtained from five females (referred to as samples 1–5), between 33 and 49 years of age, who underwent elective surgery for morbid obesity, after informed consent.

Table 1. Carbohydrate determinants present on the gastric mucins investigated.

The antibodies used are indicated within parentheses.

| Carbohydrate structure | Sample no… | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (clone A003) | − | + | − | − | − | |

| B (clone B005) | − | − | − | − | + | |

| H-type-2 (clone 92FRA2) | + | − | + | + | + | |

| Lea (clone 7LE) | − | + | − | − | − | |

| Leb (clone 2-25LE) | + | − | − | + | + | |

| H-type-1, Leb (96FR2.10) | + | − | + | + | + | |

| Sialyl-Lex (clone KM93) | − | − | − | − | − |

Analytical methods

Density measurements were performed using a Carlsberg pipette as a pycnometer. Sialic acid was detected using an automated method [17], and carbohydrate was detected as periodate-oxidizable structures [18]. In addition, sialic acid (carboxylate groups) and sulphate were assayed by staining aliquots of samples blotted on to PVDF membranes with 1% Alcian Blue 8GX [13]. Both sialic acid and sulphate are stained in 3% (v/v) acetic acid, pH 2.5, whereas mainly sulphate residues are stained in 0.1 M HCl, pH 1. The difference in reactivity between pH 2.5 and pH 1 is ascribed to sialic acid. MUC1 was assayed by blotting fractions on to PVDF membranes. Unbound sites were blocked with 0.5% (w/v) BSA in blocking buffer [5 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4)/0.15 M NaCl/0.05% Tween 20] for 1 h. The membranes were washed three times in blocking buffer between all ensuing steps. The membranes were incubated with the anti-MUC1 antibody (clone 215D4) diluted 1:20 in blocking buffer, and then with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibodies diluted 1:2000 in blocking buffer for 1 h. Bound secondary antibody was visualized using the ECL® detection kit, and intensity was quantified with a Hoefer GS 300 densitometer. MUC1 was also detected using ELISA, with similar results but weaker signals.

Microtitre-based assay and inhibition experiments with H. pylori

These assays were performed as described previously [3], with the exception that pH was adjusted to 1–7.4 in the Boehringer blocking reagent for ELISA supplemented with 10 mM citric acid and 0.05% Tween 20. ELISA was performed as described previously [3].

Rate zonal centrifugation

Samples were treated with chondroitinase ABC (0.005 unit/ml) in 0.1 M Tris/acetate buffer, pH 7.3, containing 5 mM sodium-EDTA at 37 °C for 4 h, with DNase (5 μg/ml) in 5 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, at 37 °C for 4 h, or with both chondroitinase ABC and DNase. The samples were then dialysed in 5 M GdmCl (guanidinium chloride)/10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, layered on top of a gradient (6–8 M GdmCl) and centrifuged for 6 h at 20 °C and 40000 rev./min (197000 g; total gradient volume 11.6 ml) using a Beckman SW-41 Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA, U.S.A.).

CsCl density-gradient centrifugation in 0.5 M GdmCl

Samples were dialysed into 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 6.5, containing 0.5 M GdmCl and 5 mM sodium EDTA, and subjected to isopycnic CsCl density-gradient centrifugation in 0.5 M GdmCl with a starting density of 1.50 g/ml for 90 h at 15 °C and 36000 rev/min (118000 g) using a Beckman 50.2 Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter Inc.).

Chromatography

Reduction of mucins, gel chromatography and anion-exchange chromatography were performed as described previously [3,13].

RESULTS

Density-gradient centrifugation in CsCl/4 M GdmCl

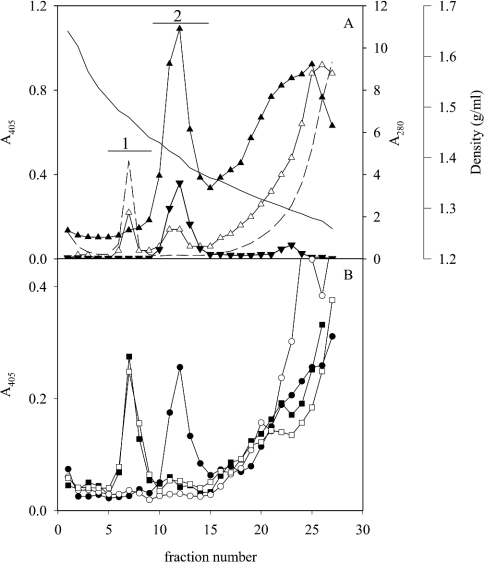

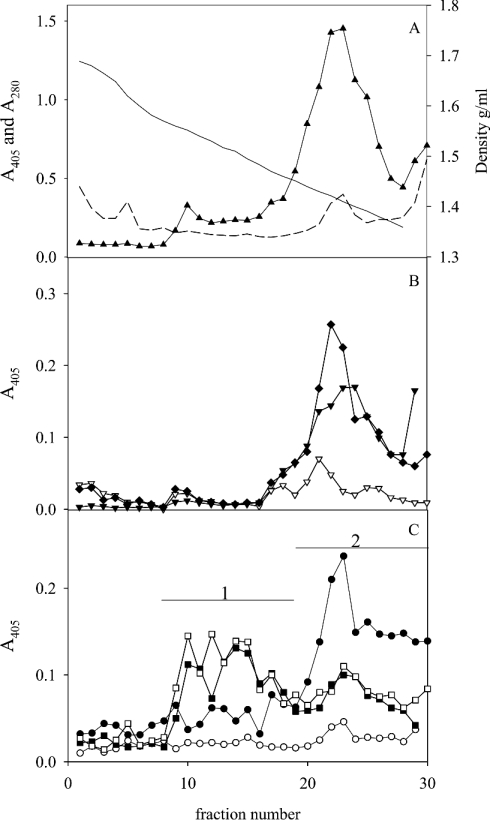

Fractions from five density gradients of extracts of human gastric mucosa from individuals expressing different blood-group antigens (Table 1) were analysed for binding with eight H. pylori strains with different adhesin repertoires using a microtitre-based assay. At neutral pH, the two Leb-binding strains (17875/Leb and P466) that utilize BabA bound MUC5AC in Leb-positive samples, whereas the other six strains showed no or little binding to the mucins, as shown previously (Figures 1A and 1B) [3]. All strains bound to material of the same density as DNA (appearing at 1.47 g/ml under these conditions [19]) at pH 3, but not at pH 7.4 (Figures 1A and 1B), with an optimum at pH 5. Rate-zonal centrifugation of this material (pooled according to bar 1; Figure 1A) separated a smaller component from a larger one that both bound H. pylori at acidic pH (results not shown). The smaller one was degraded by chondroitinase ABC, but not by DNase, whereas the larger one was degraded by DNase, but not by chondroitinase ABC. The fact that chondroitinase ABC and DNase together abolished all microbe binding suggests that the sialic acid reactivity in pool 1 is not explained by the presence of a mucin-like component in this fraction. Because of the low sialic acid content in gastric mucins, fractions from the density gradients were analysed at high sample concentrations, and the sialic acid in pool 1 may in part be due to cross-reactivity with DNA. The binding to the component degraded by chondroitinase ABC (putative proteoglycan) was stronger at pH 3, whereas binding to DNA was more pronounced at pH 5 (results not shown). In addition, H. pylori bound to low-density non-mucin material at the top of the gradient, as observed previously [3]. This binding was not characterized here.

Figure 1. CsCl density-gradient centrifugation in 4 M GdmCl of an extract of human gastric mucosa from an Leb-positive individual (sample 1).

Fractions were analysed for: (A) density (—), A280 (---), carbohydrate (▲), sialic acid (△), MUC5AC (▼); and (B) binding with bacterial strain 17875/Leb (Leb-binding, ●) and the babA1A2 mutant (○) at pH 7.4 and these strains at pH 3 (■, □) respectively. No MUC2 or MUC5B was detected using the LUM5B-2 and LUM2-LUM3 antibodies respectively.

pH-dependence of H. pylori binding to mucin glycoforms

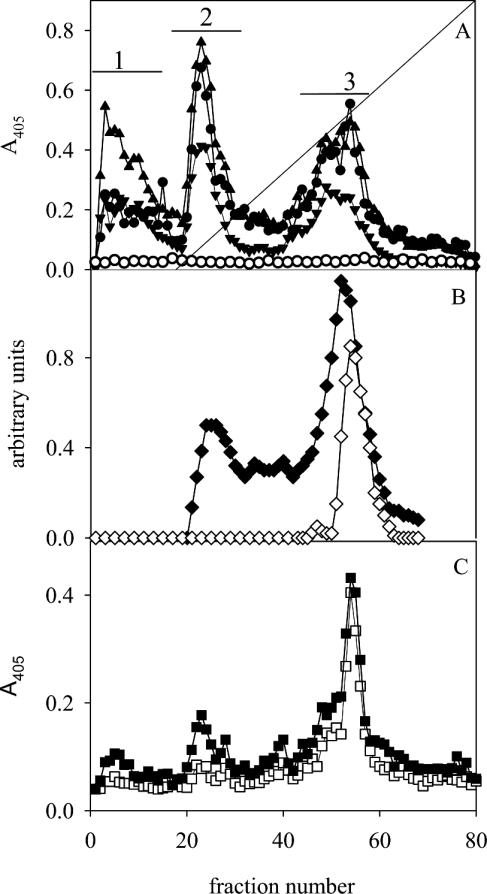

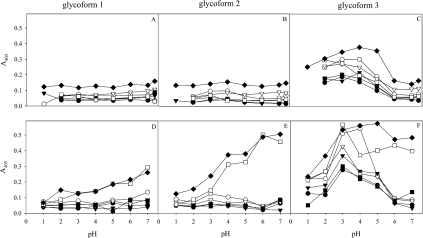

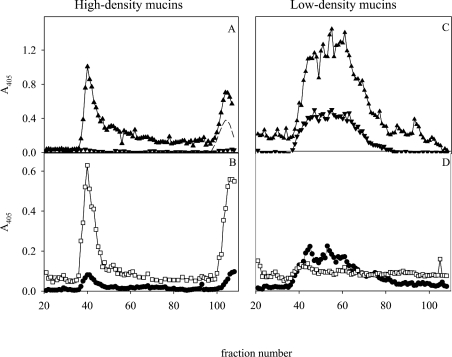

When subjected to anion-exchange chromatography, the MUC5AC subunits separate into three glycoforms (glycoforms 1–3), as shown in Figure 2(A) (bars 1–3), whereas MUC6 was present as glycoforms 1 and 2, as described previously [3]. In Leb-positive individuals, the Leb antigen was detected in all three glycoforms. Sulphate (as detected by Alcian Blue at pH 1) was identified in glycoform 3 and sialic acid (as the difference between Alcian Blue staining at pH 2.5 and pH 1) in glycoforms 2 and 3. The glycoforms can thus be broadly described as neutral mucins (glycoform 1), sialomucins (glycoform 2) and a mixture of sialo- and sulpho-mucins (glycoform 3). The sulphated species within glycoform 3 have a slightly higher charge than the sialylated ones (Figure 2B). Sialyl-Lex was negative in all glycoforms from all individuals, indicating that the sialic acid present in the acidic glycoforms is not part of this structure. At pH 3, all H. pylori strains (including those expressing SabA) bound to glycoform 3, and binding was more pronounced to the sulphated species than to the sialylated ones (Figure 2C). H. pylori binding to the mucins at pH 3 is more evident after separating them into glycoforms, which can be explained by the fact that the highly charged species only comprise a small proportion of the material. At pH 3, no difference in binding was detected between mucins carrying different blood-group structures (Table 1) and strains with different adhesins. In contrast, at pH 7.4, the non-Leb-binding strains (the babA1A2 mutant; Figure 2A, CCUG17874, P1, P1-140, M019 and 26695, results not shown) showed no binding to the mucins from any of the five samples investigated, whereas the Leb-binding BabA-positive strains (17875/Leb; Figure 2A and P466, results not shown) differed in their binding to the three Leb-positive mucin glycoforms, but did not bind to the Leb-negative ones [3]. The three glycoforms were pooled individually (Figure 2A, bars 1–3), and binding was investigated as a function of pH. In the Leb-negative sample, no binding was detected to glycoforms 1 and 2, whereas binding to glycoform 3 had a maximum at pH 3–4 for all strains (Figures 3A–3C). In the Leb-positive sample, binding was similar for the non-Leb-binding strains, whereas binding of the Leb-binding strains to glycoforms 1 and 2 increased with pH, and binding to glycoform 3 was most pronounced at pH 3–5 (Figures 3D–3F).

Figure 2. Mucin glycoforms.

Mucins were pooled (Figure 1A, bar 2), reduced into subunits and subjected to anion-exchange chromatography on a Mono Q column. The fractions were analysed for: (A) carbohydrate (▲), MUC5AC (▼), binding with the H. pylori strain 17875/Leb (●) and the babA1A2 mutant (○) at pH 7.4; (B) Alcian Blue staining at pH 2.5 (◆) and pH 1.0 (◇); and (C) binding to strain 17875/Leb (■) and the babA1A2 mutant (□) at pH 3.

Figure 3. Effect of pH on H. pylori binding to mucin glycoforms.

Glycoforms 1, 2 and 3 were pooled (Figure 2A, bars 1, 2 and 3) and H. pylori binding was assessed at pH 1–7.4 to an Leb-negative sample (sample 3; A–C) and a Leb-positive one (sample 1; D–F). In the Leb-positive sample, binding with strain 17875/Leb (◆) and P466 (□) carrying the Leb-binding BabA adhesins show a pH-dependence differing from strains CCUG17874 (●), P1 (○), P1–140 (▼), 26695 (▽) and the babA1/2 mutant (■) that lack this adhesin.

Identification of non-MUC5AC H. pylori-binding mucin at neutral pH

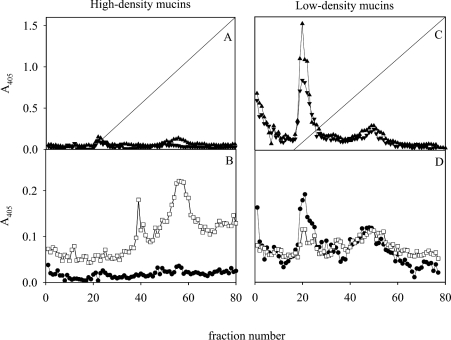

As expected, after gel chromatography of the mucins (Figure 1A, bar 2), MUC5AC eluted in the void (Figure 4A). However, considerable H. pylori binding was also found to material of much smaller size (Figure 4B). In the two samples reacting most strongly with Leb antibodies, there was strong reactivity with the Leb-binding BabA-positive strains, both with the void fractions containing Leb-positive MUC5AC and this additional smaller component, whereas the other bacteria showed only weak or no reactivity. This material did not react with antibodies against MUC5AC and MUC6; however, an antibody against MUC1 reacted with part of the low-molecular-mass population (Figure 4). The remaining part of the distribution may also be MUC1, since it is well known that the epitopes recognized by antibodies against the MUC1 ectodomain may be shielded by glycosylation, and possibly only MUC1 populations with a low degree of glycosylation and hence a smaller size are detected. An antibody (clone 96FR 2) that recognizes the H-type-1 structure in addition to Leb reacted with the included component(s) (Figure 4A), although the specific Leb antibody (2-25LE) did not, suggesting that the H-type-1 structure is present on this molecule. Binding to the included component(s) was completely inhibited by HSA (human serum albumin)-Leb or HSA–H-type-1 conjugates in a concentration-dependent way, with a higher concentration of H-type-1 than of Leb needed to achieve the same level of inhibition (results not shown). In summary, component(s) (e.g. MUC1) with the same density as MUC5AC and MUC6, but of much smaller size, bind H. pylori via BabA.

Figure 4. Size fractionation of mucins.

Mucins were pooled (Figure 1A, bar 2) and subjected to gel chromatography. Fractions were analysed for: (A) carbohydrate (▲), MUC5AC (▼), Leb (clone 2–25LE; ◆) and reactivity with an antibody (clone 96FR2.10) recognizing the Leb, BLeb, ALeb and H-type-1 structures (▽), and (B) MUC1 (◇) and binding with the H. pylori strain 17875/Leb (●) and the babA1A2 mutant (○) at pH 7.4.

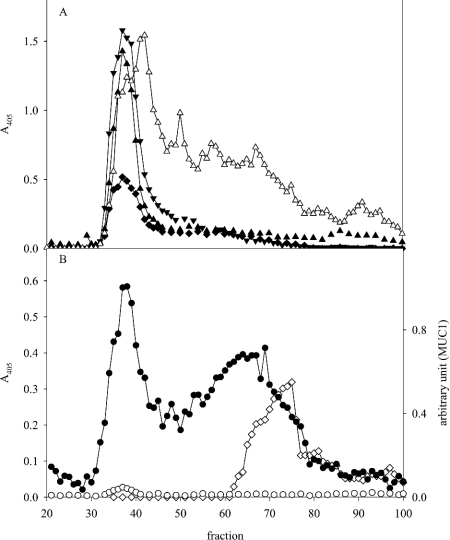

Identification of a putative monomeric mucin that binds H. pylori at acidic pH

By subjecting the mucins (Figure 1A, bar 2) to CsCl density-gradient centrifugation in 0.5 M GdmCl, the majority of the material (analysed as MUC5AC, MUC6 and carbohydrate; Figures 5A and 5B) was separated from yet another H. pylori-binding component. At pH 7.4, the Leb-binding strain 17875/Leb followed the Leb and MUC5AC reactivities, whereas binding of the babA1A2 mutant was modest (Figure 5C). At pH 3, both strains (17875/Leb and the babA1A2 mutant) bound to the ‘high-density’ material (1.55–1.45 g/ml), but also to components (including MUC5AC) appearing at a lower density (1.35–31.45 g/ml). The ‘high-density’ material is not DNA, since DNA occurs at a much higher density (1.60–1.75 g/ml) under these conditions (results not shown) [19]. Thus the mucin-containing fractions in the CsCl density-gradient centrifugation performed in 4 M GdmCl contain a component of higher density in 0.5 M GdmCl than MUC5AC/MUC6 that binds H. pylori at pH 3.

Figure 5. Separation of ‘high-density’ mucin populations from ‘low-density’ ones.

Mucins were pooled (Figure 1A, bar 2) and subjected to a second density-gradient centrifugation step in CsCl/0.5 M GdmCl. Fractions were analysed for: (A) density (—), A280 (---) and carbohydrate (▲); (B) MUC5AC (▼), MUC6 (▽) and Leb (◆); and (C) binding with H. pylori strain 17875/Leb (●) and the babA1A2 mutant (○) at pH 7.4; as well as binding with strain 17875/Leb (■) and the babA1A2 mutant (□) at pH 3.

Size of the ‘high-density’ and ‘low-density’ components after reduction

The ‘high-density’ H. pylori-binding material (Figure 5C, bar 1) was separated by gel chromatography into two components after reduction, eluting in the void and in the total volume respectively. Both reacted as carbohydrate, and bound the babA1A2 mutant at pH 3, whereas little binding was detected at pH 7.4 with strain 17875/Leb (Figures 6A and 6B). Possibly, material eluting in the total volume represents a smaller ‘subunit’ attached to a larger one via disulphide bonds. When the ‘low-density’ material (Figure 5C, bar 2) was subjected to the same treatment, carbohydrate, MUC5AC and BabA-dependent H. pylori binding at pH 7.4 (17875/Leb) appeared as a broad peak starting in the void, and very little reactivity (the babA1A2 mutant) was detected at pH 3 (Figures 6C and 6D). Consequently, the component binding H. pylori at acidic pH seems to have a larger size than MUC5AC and MUC6 subunits, in addition to having a higher density. In order to assess whether this component was present in all samples, the mucins were pooled directly (from samples 2–5) from the first density-gradient centrifugation (Figure 1A, bar 1) and subjected to reduction and gel chromatography (results not shown). MUC5AC, MUC6, carbohydrate reactivity and binding with the Leb-binding BabA-positive strains at pH 7.4 show a similar elution pattern as shown in Figure 6, and at pH 3 all strains bound to a component in the void volume in the four samples investigated.

Figure 6. Size of the ‘high-density’ (A and B) and ‘low-density’ (C and D) mucin populations.

‘High-density’ (Figure 5C, bar 1), and ‘low-density’ material (Figure 5C, bar 2) were reduced and subjected to gel chromatography. Fractions were analysed for: (A and C) carbohydrate (▲), MUC5AC (▼) and A280 (---); and (B and D) binding with the H. pylori strain 17875/Leb at pH 7.4 (●) and the babA1A2 mutant at pH 3 (□).

Charge of the ‘high’- and ‘low-density’ components

The ‘high-density’ (Figure 5C, bar 1) H. pylori-binding population was subjected to anion-exchange chromatography. At pH 3, the babA1A2 mutant mainly bound to material corresponding to glycoform 3, but of slightly higher charge than the main population (Figure 7B), i.e. the sulphated subpopulation (see Figure 2B). The ‘low-density’ material (Figure 5C, bar 2) eluted as three glycoforms containing carbohydrate and MUC5AC that bound to strain 17875/Leb at pH 7.4. At pH 3, the babA1A2 mutant bound weakly to glycoforms 2 and 3 (Figure 7D).

Figure 7. Charge density of the ‘high-density’ and ‘low-density’ mucin populations.

High-density (Figure 5C, bar 1) and low-density (Figure 5C, bar 2) material was reduced and subjected to anion-exchange chromatography. Fractions were analysed for: (A and C) carbohydrate (▲), MUC5AC (▼) and (B and D) binding with the H. pylori strain 17875/Leb at pH 7.4 (●) and the babA1A2 mutant at pH 3 (□).

DISCUSSION

In this study, the effects of pH on H. pylori binding to gastric mucins were investigated. At acidic pH, the binding to Leb described previously [3] was abolished, but binding to other structures occurred. In addition to binding to mucins, the microbe bound to a putative proteoglycan containing chondroitin sulphate/dermatan sulphate side chains. However, in biopsies from four apparently normal individuals, the latter component was not found (S. Lindén and I. Carlstedt, unpublished work), indicating that this molecule is located ‘deep’ in the tissue. Binding to DNA was also observed, and had an optimum at pH 5. H. pylori has previously been shown to interact with heparin and heparan sulphate with a binding maximum at pH 4–5, and with laminin, vitronectin and plasminogen at neutral pH [20,21]. Most likely, none of these structures are available for H. pylori binding in the healthy stomach, but may, together with DNA and chondroitin sulphate/dermatan sulphate, be exposed in damaged tissue.

In individuals expressing the Leb structure, Leb-binding strains with BabA adhesins bound to components of ‘typical’ mucin density, but of smaller size than MUC5AC at neutral pH. The low-molecular-size species of this material appears to be MUC1, whereas the part of the distribution (Figure 4) that does not react with the MUC1 antibodies may be explained by the presence of a so-far-unidentified ‘mucin-like’ component and/or by MUC1 species with the epitopes recognized by the antibody shielded by glycosylation. No Leb reactivity co-eluted with this material; however, reactivity was observed with an antibody recognizing the H-type-1 structure in addition to Leb [16]. H. pylori binding was inhibited in a concentration-dependent manner by both Leb and H-type-1 conjugates, suggesting that H-type-1 could be the structure mediating binding. Our results suggest that the same adhesin is responsible for binding to this component as to MUC5AC, but that the microbe has a stronger avidity for Leb than for the putative H-type-1 structure. Others have shown that antibody reactivity with the highly glycosylated MUC1 ectodomain disappears in individuals with H. pylori gastritis, suggesting that this part of MUC1 is either cleaved off or subjected to changes in glycosylation that shield the epitopes recognized by the antibody used [14]. Together, these observations suggest that MUC1 may play an important role in H. pylori colonization and the consequences thereof.

At acidic pH, yet another component with a mucin density was found to bind H. pylori in a strain- and blood-group-independent way. This putative mucin has a higher charge and larger size than subunits of MUC5AC, and may consist of a large subunit connected via disulphide bonds to a small one. All the non-MUC5AC/MUC6 putative cell-associated H. pylori-binding mucins are present in very small amounts relative to the secreted oligomeric ones. This is in keeping with the latter being present both as a thick mucus layer attached to the mucosa and as a highly condensed storage form in the secretory granules, whereas cell-associated mucins only occur as a single molecular ‘layer’ at the luminal plasma membrane. H. pylori binding to charged molecules at acidic pH seems to be a feature common to all strains studied. Adherence to mucins at acidic pH could retain the bacteria in an environment incompatible with survival and, possibly, provide one host defence mechanism. In contrast, binding via the Leb-binding BabA allows the microbes to adhere at neutral pH and detach when the mucus gel is released into the acidic gastric juice.

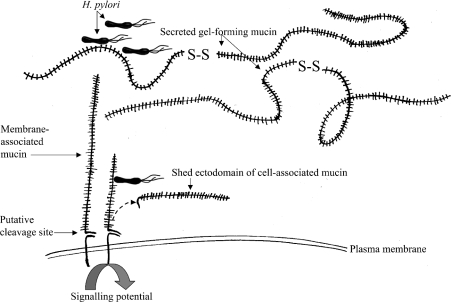

The implications of our work on H. pylori binding to secreted and membrane-associated mucins are summarized in Figure 8. The molecular design of the latter indicates that they can initiate intracellular signalling, and that their extracellular ‘ectodomain’ can be detached from the cell surface. Possibly, H. pylori binding to cell-associated mucins may cause signal transduction over the epithelial barrier, as shown for Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a cell culture model [15], and/or trigger microbe removal from the luminal surface of the epithelial cells by releasing the ‘ectodomain’ into the lumen. Whether the bacteria bind to the membrane-associated or to the secreted mucus-forming mucins depends both on the glycosylation of the respective mucins and on the adhesins present on the bacteria. The observation that BabA seems to have a higher avidity for Leb present on MUC5AC than for the putative H-type-1 structure on MUC1 suggests that the secreted gel-forming mucins may function as decoys for microbe binding to the membrane-associated ones, and this notion is supported by the fact that the secreted mucins are present in much larger amounts. Consequently, the interplay between binding to secreted and cell-associated mucins is likely to influence host–microbe cross-talk and thus to determine the outcome of H. pylori colonization; however, further work is needed to unravel the mechanisms involved.

Figure 8. Pictorial summary of mucin-H. pylori interactions.

H. pylori binding occurs both to secreted and membrane-associated mucins. The membrane-associated mucins contain a cleavage site that potentially would allow the glycosylated ectodomain to be removed from the cell surface, and they have been shown to participate in signalling events [15]. Competition between H. pylori binding to membrane-associated and secreted mucins is thus likely to influence the outcome of the host–microbe interaction. The Figure is not drawn to scale.

In summary, this work shows that H. pylori binding to human gastric mucins may occur in two different ways: (1) in a blood-group-dependent way at neutral pH, or (2) in a charge-dependent way to sulphated or sialylated mucins, with a pH optimum at approx. 3–4. At least two putative membrane-associated mucins were identified as H. pylori-binding targets (one being MUC1), and it is proposed that competition in binding to secreted and cell-associated mucins will decide the outcome of host–microbe cross-talk.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research (Glycoconjugates in Biological Systems); the Swedish Medical Research Council (grants 7902 and 11218); the Swedish Cancer Society (4101-B00-03XAB); the Crafoord Foundation; Österlunds Stiftelse; Council for Medical Tobacco Research; Swedish Match; and the Medical Faculty of Lund. We thank Dr J. Hilkens and Dr J. Bara for kindly providing antibodies against MUC1 and Lewis antigens respectively.

References

- 1.De Bolos C., Garrido M., Real F. X. MUC6 apomucin shows a distinct normal tissue distribution that correlates with Lewis antigen expression in the human stomach. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:723–734. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90379-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nordman H., Davies J. R., Lindell G., de Bolos C., Real F., Carlstedt I. Gastric MUC5AC and MUC6 are large oligomeric mucins that differ in size, glycosylation and tissue distribution. Biochem. J. 2002;364:191–200. doi: 10.1042/bj3640191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindén S., Nordman H., Hedenbro J., Hurtig M., Borén T., Carlstedt I. Strain- and blood group-dependent binding of Helicobacter pylori to human gastric MUC5AC glycoforms. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1923–1930. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.37076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gendler S. J., Spicer A. P. Epithelial mucin genes. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1995;57:607–634. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.003135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Helicobacter and Cancer Collaborative Group. Gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori: a combined analysis of 12 case control studies nested within prospective cohorts. Gut. 2001;49:347–353. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.3.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tomb J. F., White O., Kerlavage A. R., Clayton R. A., Sutton G. G., Fleischmann R. D., Ketchum K. A., Klenk H. P., Gill S., Dougherty B. A., et al. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature (London) 1997;388:539–547. doi: 10.1038/41483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ilver D., Arnqvist A., Ogren J., Frick I. M., Kersulyte D., Incecik E. T., Berg D. E., Covacci A., Engstrand L., Borén T. Helicobacter pylori adhesin binding fucosylated histo-blood group antigens revealed by retagging. Science. 1998;279:373–377. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahdavi J., Sonden B., Hurtig M., Olfat F. O., Forsberg L., Roche N., Angstrom J., Larsson T., Teneberg S., Karlsson K. A., et al. Helicobacter pylori SabA adhesin in persistent infection and chronic inflammation. Science. 2002;297:573–578. doi: 10.1126/science.1069076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Odenbreit S., Till M., Hofreuter D., Faller G., Haas R. Genetic and functional characterization of the alpAB gene locus essential for the adhesion of Helicobacter pylori to human gastric tissue. Mol. Microbiol. 1999;31:1537–1548. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teneberg S., Miller-Podraza H., Lampert H. C., Evans D. J., Jr, Evans D. G., Danielsson D., Karlsson K. A. Carbohydrate binding specificity of the neutrophil-activating protein of Helicobacter pylori. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:19067–19071. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.19067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunn B. E., Cohen H., Blaser M. J. Helicobacter pylori. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1997;10:720–741. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.4.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borén T., Falk P., Roth K. A., Larson G., Normark S. Attachment of Helicobacter pylori to human gastric epithelium mediated by blood group antigens. Science. 1993;262:1892–1895. doi: 10.1126/science.8018146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindén S., Borén T., Dubois A., Carlstedt I. Rhesus monkey gastric mucins: oligomeric structure, glycoforms and Helicobacter pylori binding. Biochem. J. 2004;379:765–775. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vinall L. E., King M., Novelli M., Green C. A., Daniels G., Hilkens J., Sarner M., Swallow D. M. Altered expression and allelic association of the hypervariable membrane mucin MUC1 in Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:41–49. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lillehoj E. P., Kim H., Chun E. Y., Kim K. C. Pseudomonas aeruginosa stimulates phosphorylation of the epithelial membrane glycoprotein Muc1 and activates MAP kinase. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2004;287:L809–L815. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00385.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Good A. H., Yau O., Lamontagne L. R., Oriol R. Serological and chemical specificities of twelve monoclonal anti-Lea and anti-Leb antibodies. Vox Sang. 1992;62:180–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1992.tb01195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lohmander L. S., De Luca S., Nilsson B., Hascall V. C., Caputo C. B., Kimura J. H., Heinegard D. Oligosaccharides on proteoglycans from the swarm rat chondrosarcoma. J. Biol. Chem. 1980;255:6084–6091. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Svitacheva N., Davies J. R. Mucin biosynthesis and secretion in tracheal epithelial cells in primary culture. Biochem. J. 2001;353:23–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carlstedt I., Lindgren H., Sheehan J. K., Ulmsten U., Wingerup L. Isolation and characterization of human cervical-mucus glycoproteins. Biochem. J. 1983;211:13–22. doi: 10.1042/bj2110013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirmo S., Utt M., Ringner M., Wadström T. Inhibition of heparan sulphate and other glycosaminoglycans binding to Helicobacter pylori by various polysulphated carbohydrates. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 1995;10:301–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1995.tb00048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ringner M., Valkonen K. H., Wadström T. Binding of vitronectin and plasminogen to Helicobacter pylori. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 1994;9:29–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1994.tb00470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]