Abstract

NS3, a non-structural protein of the HCV (hepatitis C virus), contains a protease and a helicase domain and plays essential roles in the processing of the viral polyprotein, viral RNA replication and translation. LMP7 (low-molecular-mass protein 7), a component of the immunoproteasome, was identified as an NS3-binding protein from yeast two-hybrid screens, and this interaction was confirmed by in vitro binding and co-immunoprecipitation analysis. The minimal domain of interaction was defined to be between the pro-sequence region of LMP7 (amino acids 1–40) and the protease domain of NS3. To elucidate the biological importance of this interaction, we studied the effect of this interaction on NS3 protease activity and on LMP7 immunoproteasome activity. Recombinant LMP7 did not have any effect on NS3 protease activity in vitro. The peptidase activities of LMP7 immunoproteasomes, however, were markedly reduced when tested in a stable cell line containing a HCV subgenomic replicon. The down-regulation of proteasome peptidase activities could interfere with the processing of viral antigens for presentation by MHC class I molecules, and may thus protect HCV from host immune surveillance mechanisms to allow persistent infection by the virus.

Keywords: hepatitis C virus (HCV), immunoproteasome, low-molecular-mass protein 7 (LMP7), non-structural protein NS3, proteasome

Abbreviations: a.a., amino acid; Boc-LRR-AMC, t-butoxycarbonyl-Leu-Arg-Arg-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin; co-IP, co-immunoprecipitation; DTT, dithiothreitol; GST, glutathione S-transferase; HCV, hepatitis C virus; IFN-γ, interferon-γ; LMP7, low-molecular-mass protein 7; MECL-1, multicatalytic endopeptidase complex-like-1; NS, non-structural protein; NS5A5B, NS5A–NS5B; S138A etc., Ser138→Ala etc.; Suc-LLVY-AMC, succinyl-Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-AMC; Z-LLE-AMC, benzyloxycarbonyl-Leu-Leu-Glu-AMC

INTRODUCTION

HCV (hepatitis C virus) infects about 170 million people world-wide and chronic infection often leads to liver diseases, such as cirrhosis, steatosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [1,2]. HCV poses a serious and long-term medical challenge, as the development of effective anti-HCV drugs and therapies have been impeded by the lack of cell culture and small animal model systems, as well as the emergence of HCV quasispecies [3,4]. Much of the research into HCV has focused on the study of viral–host interactions, with the aim to identify cellular proteins that may be essential for the replication cycle of HCV.

HCV is a single plus-strand enveloped RNA virus of the Flaviviridae family and is the sole member in the genus Hepacivirus. The viral RNA genome encodes a large polyprotein of 3010 a.a. (amino acids), which is cleaved by host and viral proteases to generate 9 or 10 proteins [5,6]. The structural proteins that are assembled to form viral particles are core and envelope proteins, E1 and E2. The non-structural proteins are NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A and NS5B [7,8]. NS2, together with the N-terminal domain of NS3, comprise a metalloprotease responsible for cleavage at the NS2–NS3 junction [9,10]. The N-terminus one third of NS3 encodes a serine protease, which, with NS4A as a cofactor, is responsible for cleavage at the NS3–NS4A, NS4A–NS4B, NS4B–NS5A and NS5A–NS5B junctions [11,12]. The remaining C-terminal portion of NS3 contains the NTPase/helicase domain [13]. The HCV NS5B is the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase [14]. The functions of NS4B and NS5A are largely unknown, but are likely to act as cofactors in HCV RNA replication.

In addition to the obvious role of NS3 in viral replication, this protein may play a role in regulating cell proliferation through its interaction with p53 tumour suppressor [15,16]. NS3 was also reported to transform NIH 3T3 cells [17], as well as rat 3T3 cells [18], implicating its involvement in oncogenesis. Given the highly conserved sequence of the NS3 protease and helicase domains among different HCV genotypes, NS3 is likely to play a pivotal role in catalysing viral replication.

In the present study, a yeast two-hybrid screen of a human spleen cDNA library was set up to identify host proteins that interact with NS3. One clone encoding a low-molecular-mass protein, LMP7, an IFN-γ (interferon-γ)-inducible beta subunit of the proteasome, was isolated. The core of the proteasome is a 20 S barrel-like multicatalytic endopeptidase complex with a stack of four rings, comprising two outer identical alpha-rings and two identical inner beta-rings. The alpha and beta rings are each made up of seven structurally similar alpha and beta subunits. Eukaryotic core particles consist of six active sites, three on each of its two central beta-rings: two sites on subunits X (β5), two sites on subunits Z (β2) and the remaining two sites on subunits Y (β1). These catalytic sites are associated with several peptidase activities of the 20 S core, including chymotrypsin-like activity, which cleaves following hydrophobic residues, trypsin-like activity, which cleaves following basic residues, and post-acidic activity, which cleaves following acidic residues [19–21]. Upon viral infection or IFN-γ stimulation, the beta subunits Y, X, and Z are down-regulated and are replaced by LMP2 (β1i), LMP7 (β5i) and MECL-1 (multicatalytic endopeptidase complex-like-1; β2i) respectively, generating immunoproteasomes, which are responsible for the generation of MHC class I ligands for antigen presentation through the MHC class I pathway [22,23]. In the present study, we characterized in detail the interaction between NS3 and LMP7 and the effect of their binding on the NS3 protease and immunoproteasome activities.

EXPERIMENTAL

Construction of plasmids

The NS3-coding sequence was amplified from HCV RNA extracted from HCV-positive serum [24] by RT (reverse transcriptase)-PCR. For the yeast two-hybrid screen, NS3 was fused in frame with the Gal4 DNA-binding domain in pAS2-1 vector (ClonTech). For mammalian expression of FLAG- or Myc-tagged proteins, DNA fragments were cloned into pXJ40-flag or pXJ100-myc plasmids [25] respectively. For expression of GST (glutathione S-transferase)-tagged proteins in bacteria, constructs were made in pGEX-2TK vector (Pharmacia). LMP7 coding region was amplified by PCR from the spleen cDNA library with primers OLG144 (CGCGGATCCATGGCGCTACTAGATGTATGC), which contains a BamHI site, and OLG145 (CCGCTCGAGTTATTGATTGGCTTCCCGGTA), which contained a XhoI site. Plasmids generated and used in the present study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Plasmids used in this study.

| Plasmid | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| pAS-NS3 | FLAG–NS3 (a.a. 1–630) | [27] |

| pXJflag-NS3 | FLAG–NS3 (a.a. 1–630) | [27] |

| pXJflag-NS3-NdeI | FLAG–NS3 Nde I (a.a. 1–310) | Present work |

| pXJflag-NS3-protease | FLAG–NS3 protease (a.a. 1–180) | Present work |

| pXJflag-NS3-helicase | FLAG–NS3 protease (a.a. 181–630) | [27] |

| pXJflag-GST | FLAG–GST | Glaxo lab, IMCB* |

| pXJmyc-C1-28 | Myc–LMP7 (a.a. −3–277) | Present work |

| pXJmyc-LMP7 | Myc–LMP7 (a.a. 1–277) | Present work |

| pXJmyc-ΔC200LMP7 | Myc–LMP7 (a.a. 1–200) | Present work |

| pXJmyc-ΔC160LMP7 | Myc–LMP7 (a.a. 1–160) | Present work |

| pXJmyc-ΔC120LMP7 | Myc–LMP7 (a.a. 1–120) | Present work |

| pXJmyc-ΔN40LMP7 | Myc–LMP7 (a.a. 40–277) | Present work |

| pXJmyc-ΔN80LMP7 | Myc–LMP7 (a.a. 80–277) | Present work |

| pGEX-NS3 | GST–NS3 (a.a. 1–630) | Present work |

| pGEX-LMP7 | GST–LMP7 (a.a. 1–277) | Present work |

| pGEX-NS5A5B | GST–NS5A5B (cleavage site EEASEDVVPCSMSYTWTGACCFGTM) | [26] |

| pAS2-1 | Gal4 DNA-binding domain in a 2-μm TRP1 yeast shuttle vector | ClonTech |

| pACT2 | Gal4-activating binding domain in a 2-μm LEU2 yeast shuttle vector | ClonTech |

| pXJ40-flag | Mammalian expression vector for tagging proteins with FLAG at the N-terminus | [25] |

| pXJ100-myc | Mammalian expression vector for tagging proteins with c-Myc at the N-terminus with NotI and HincII sites in the same frame as in pACT2 | V. Yu laboratory, IMCB* |

| pGEX-2TK | GST-fusion expression vector with modified multiple cloning sites | S. C. Lin laboratory, IMCB* |

* IMCB, Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology, Singapore.

Yeast two-hybrid screens

Yeast two-hybrid screens of a human spleen cDNA library with NS3 as bait was performed as described in the Matchmaker user's manual (ClonTech). Interaction between NS3 and host proteins from the library was indicated by the activation of the reporter genes HIS3 and ADE2, which would allow yeast cells to grow on His− and Ade− media respectively. Ade+ phenotype represented a stronger interaction compared with His+ phenotype. Plasmids from positive library clones were sequenced and re-cloned into pXJ100-myc vector for verification by in vitro binding and co-IP (co-immunoprecipitation) assays.

In vitro binding assay

Candidate genes obtained from yeast two-hybrid screens were re-cloned into pXJ100-myc for in vitro transcription and translation. The proteins were labelled with [35S]methionine using the TNT® Quick Coupled Transcription/Translation system (Promega), following the manufacturer's instructions. The in vitro-translated products were then added to 5 μg of GST–NS3 or GST bound to glutathione beads and incubated for 1 h at room temperature (24 °C) with gentle agitation. The beads were washed four times with lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 0.5% Nonidet P40, 1% Triton X-100) supplemented with 1 mM protease inhibitor PMSF, and the bound proteins separated on SDS/PAGE gels. The gels were dried and bound proteins were detected by autoradiography.

Recombinant protein expression and purification

BL21 bacteria cells (Stratagene) transformed with pGEX-NS3 were induced with 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside) overnight at 30 °C. Cells from a 1 litre culture were pelleted and re-suspended in 5 ml of buffer A [PBS containing 1 mM DTT (dithiothreitol) and 1% Triton X-100], supplemented with 1 M NaCl and 1 mM PMSF before sonication in a Microson ultrasonic homogenizer (model XL2000). Cell debris were spun down at 47900 g for 30 min in a Sorvall SS34 rotor. The clarified supernatant was then reconstituted to 0.3 M NaCl with buffer A and 500 μl of GSH–Sepharose 4B beads (Pharmacia) were added. The GST–NS3 protein was rolled with GSH beads for 2 h, washed three times with buffer A containing 1 M NaCl and finally another three times with GSH wash buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.0, and 1 mM DTT). The GST–NS3-fusion protein was eluted from GSH beads overnight in GSH elution buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl, 1 mM DTT, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100 and 10 mM GSH). Three subsequent washes were collected, concentrated and dialysed in buffer B (20 mM Tris/HCl, pH 6.7, 1 mM DTT and 10% glycerol) in a Biomax Ultra free centrifugal filter (molecular-mass cut-off, 50 kDa; Millipore).

The GST moiety in the fusion protein could not be cleaved from NS3 with thrombin. The GST–NS3-fusion protein was eluted from beads using GSH. GST–NS3 showed good protease activity and could be used in in vitro protease assays. However, further purification was necessary as the eluted protein was found to be contaminated by smaller proteins of about 30 kDa. To further purify GST–NS3, the eluted proteins were concentrated and then subjected to FPLC using a 1-ml HiTrap SP column (Pharmacia). The column was pre-equilibrated in buffer B and the proteins were eluted through a linear gradient of 0 to 1 M NaCl in buffer B. The contaminating proteins were found to elute in the earlier fractions (fractions 3–11), whereas the fusion protein concentrated in the later fractions (fractions 27–29) at about 400 mM NaCl. A GST–NS3 protein carrying a mutation in the protease domain, to be used as a control, was also expressed and purified in the same manner.

Plasmid pGEX-LMP7 was transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 cells to express GST-tagged LMP7. Protein expression was carried out using the same procedure as for GST–NS3. After binding, GST–LMP7-bound beads were washed three times with buffer A containing 1 M NaCl and another three times with thrombin cleavage buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100 and 2.5 mM CaCl2). GST was cleaved from LMP7 with thrombin (5 units/litre of culture; Sigma) for 1 h. An abundant contaminating protein at about 70 kDa was present in the supernatant and attempts were made to purify the protein by FPLC through a HiTrap SP column, through a NaCl gradient. LMP7 was found to elute in later fractions (fraction 38 onwards) at about 500 mM NaCl. These fractions were collected and checked for binding between purified recombinant LMP7 and NS3.

Fractions containing relatively pure GST–NS3 and GST–LMP7 were stored at −80 °C for future use in in vitro protease assays. All purification steps were performed at 4 °C unless otherwise stated. The purified preparations of NS3 and LMP7 used for protease assay were found to associate with each other: LMP7 bound GST–NS3, but did not bind GST (see Figure 4A).

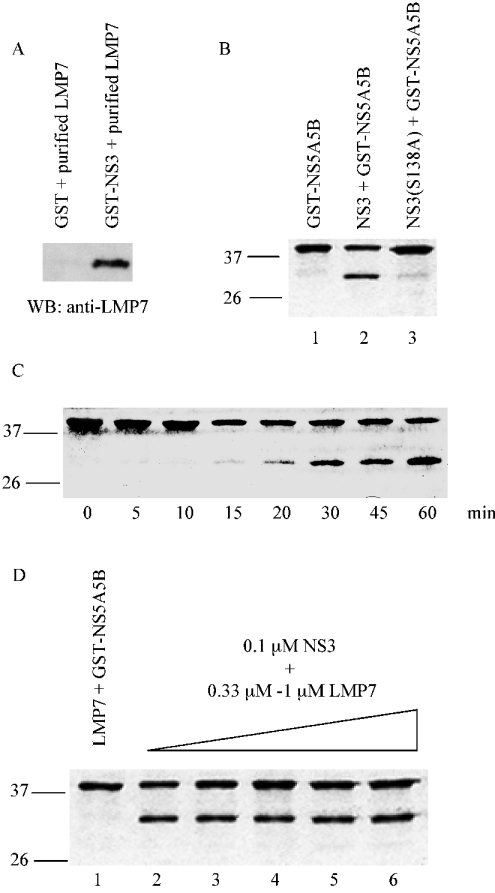

Figure 4. Effect of LMP7 on NS3 protease activity in vitro.

(A) In vitro binding of LMP7 to GST–NS3. LMP7 (200 ng) was incubated overnight with either 200 ng of GST or GST–NS3 bound to GSH beads in lysis buffer at 4 °C. The bound LMP7 was detected on Western blots with anti-LMP7 antibody. (B) Coomassie-stained SDS/PAGE gels showing the cleavage of the NS3 substrate, GST–NS5A5B. GST–NS5A5B expressed in bacteria bound on glutathione beads (lane 1). GST–NS5A5B substrate was cleaved by wild-type NS3 to release a smaller protein of approx. 30 kDa (lane 2). This showed that the purified GST–NS3 was active for protease activity. GST–NS3 protease mutant was unable to cleave substrate, showing that the GST–NS5A5B substrate was specifically cleaved by GST–NS3, and not by a co-purified contaminating bacterial protein (lane 3). (C) Optimization of protease activity. GST–NS3 protease activity was monitored over 60 min and the amount of cleaved products at different time intervals was revealed on a Coomassie-stained SDS/PAGE gel. Incubation (30 min) was sufficient to detect protease activity. (D) Different amounts of LMP7 were added to GST–NS3. Purified LMP7 did not cleave the GST–NS5A5B substrate, indicating that cleavage of GST–NS5A5B substrate was specifically due to GST–NS3 (lane 1). GST–NS3 (0.2 μg, 0.1 μM) incubated with increasing amounts of purified LMP7, 0.2–0.6 μg (0.3–1.0 μM), and the substrate was revealed on a Coomassie-stained SDS/PAGE gel (lanes 2–6).

Plasmid pGEX-NS5A5B [26] was transformed into E. coli BL21 cells for the expression of GST–NS5A5B-fusion protein (where NS5A5B refers to the NS5A–NS5B fusion protein) for use as an NS3 protease substrate. GST–NS5A5B was expressed and purified on GSH beads in the same manner as for GST–NS3.

In vitro protease activity assay

The protease activity of GST–NS3 was determined by the cleavage of GST–NS5A5B. To investigate the effect of LMP7 on NS3 protease activity in vitro, different amounts of purified LMP7, 0.2–0.6 μg, equivalent to 0.3–1.0 μM were added to the in vitro cleavage reaction. Each reaction consisted of 0.2 μg of purified GST–NS3, various amounts of LMP7, 2 μg of GST–NS5A5B bound to beads and 1 μg of NS4A peptide (a.a. 18–40) (Bioprocessing Technology Centre, Singapore) made up to a final volume of 20 μl in protease assay buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.0, 30 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2 and 10 mM DTT). The reaction mix was incubated at 37 °C with gentle agitation for 30 min. Reaction was stopped by adding SDS-loading buffer and the cleavage of GST–NS5A5B (40 kDa) to a smaller protein of about 30 kDa was observed by Coomassie staining on an SDS/PAGE gel.

Proteasome activity assay

Immunoprecipitation of proteasomes were done in either HeLa or stable cell line, 9-13, which contains self-replicating HCV subgenomic RNA [3] in Huh-7 cells. HeLa cells on a 10-cm plate (Nunc) were transfected with either 1.25 μg of pXJflag-NS3 or 0.4 μg of pXJflag-GST using LipofectAMINE™ (Invitrogen) for 6 h prior to LMP7 induction by the addition of 100 units/ml INF-γ (Roche). Similarly in 9-13 cells, LMP7 was also induced by adding 100 units/ml INF-γ. Huh-7 cells were also induced as controls. After 24 h incubation at 37 °C, cells were harvested in lysis buffer supplemented with 1 mM PMSF. Cell lysate containing 1.0 mg of total protein was incubated with 100 μl of anti-(alpha 4 subunit)-conjugated agarose (Affiniti) overnight at 4 °C. The beads were then washed three times with lysis buffer followed by another three washes with proteasome assay buffer (20 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5) and finally re-suspended in 500 μl of the same buffer.

The proteasomes isolated from 9-13 cells were tested for peptidase activities by the use of three different fluorogenic peptide substrates. Each proteasome assay consisted of 0.6 μg of immunoprecipitated proteasome complex, 0.1 mM Suc-LLVY-AMC (succinyl-Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin; Affiniti), Boc-LRR-AMC (t-butoxycarbonyl-Leu-Arg-Arg-AMC; Affiniti), or Z-Leu-Leu-Glu-AMC (benzyloxycarbonyl-LLE-AMC; Boston Biochem), with or without the proteasome inhibitor clasto-lactacystin β-lactone (Affiniti) in a final volume of 150 μl of proteasome assay buffer. The reaction mix was incubated for 20 min at 37 °C, after which 100 μl of reaction mix was quenched with 100 μl of cold ethanol. Fluorescence measurements were read by a spectrofluorimeter (Tecan) at 360 nm excitation and 465 nm emission on a 96-well black F16 Maxisorp plate (Nunc). Each assay was performed in triplicate.

Tissue culture

COS-7, a monkey kidney fibroblast cell line, and HeLa, a human cervical carcinoma cell line (A.T.C.C.), were maintained in standard DMEM (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (HyClone Laboratories) and antibiotics, 10 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Sigma). The 9-13 stable cell line was maintained in standard DME medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 10 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 1 mg/ml Geneticin (Gibco).

Co-IP and Western blot analyses

Co-IP between the NS3 and LMP7 fragments, and Western blot analyses were performed as described previously [27]. Briefly, COS-7 cells on 6-cm plates were transfected with 0.5 μg of DNA using Effectene (Qiagen), according to manufacturer's instructions. Cells were harvested in lysis buffer and 150 μg of total protein was incubated with 20 μl of anti-FLAG agarose beads (Sigma) overnight at 4 °C. After four washes with lysis buffer, 2× sample buffer was added to the samples and boiled before loading on to SDS/PAGE gels. Western blots were probed with antiMyc polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biochemicals; 1:1000 dilution), anti-FLAG polyclonal antibody (Sigma; 1:5000), anti-GST polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biochemicals; 1:10000) or anti-LMP7 monoclonal antibody (Affiniti; 1:500).

RESULTS

Screening for NS3 host-interacting partner

A spleen cDNA library was used instead of a liver library in yeast two-hybrid screens, as a liver library repeatedly yielded many candidate genes encoding secreted proteins and false-positive candidates. The liver is known to express a large number of secreted proteins that are not likely to interact with NS3, a cytoplasmic protein. In addition to the liver, HCV has been reported to also infect B-cells [28,29], and the spleen is the organ from which B-cells originate.

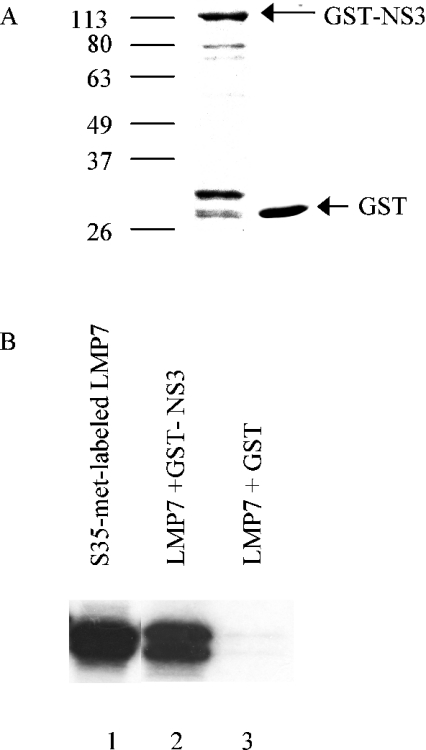

Yeast two-hybrid screens of a human spleen cDNA library with NS3 as bait identified a clone encoding LMP7, a beta subunit of the immunoproteasome complex. This clone included the full-length coding sequence and 9 nt of the 5′-UTR (untranslated region) of the LMP7 gene. The coding region of this protein was amplified by PCR from the spleen cDNA library, and the interaction between LMP7 and NS3 was verified by in vitro binding assay. [35S]-Methionine-labelled LMP7 was incubated with either GST–NS3 or GST bound to beads (Figure 1A). LMP7 bound to GST–NS3, but not GST (Figure 1B), confirming the interaction shown by yeast two-hybrid assays, and indicating that the interaction between LMP7 and NS3 is specific.

Figure 1. NS3–LMP7 interaction demonstrated by in vitro binding assay.

(A) Recombinant GST and GST–NS3 were expressed in bacteria and bound to GSH beads. Protein (2 μg) was separated on an SDS/PAGE gel and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. Molecular mass markers are indicated. (B) LMP7 was [35S]methionine-labelled in an in vitro transcription–translation reaction using pXJmyc-C1-28 as template (lane 1). LMP7 bound to recombinant GST–NS3 (lane 2), but not to GST (lane 3).

Delineating the region of interaction in NS3 and LMP7 by co-IP

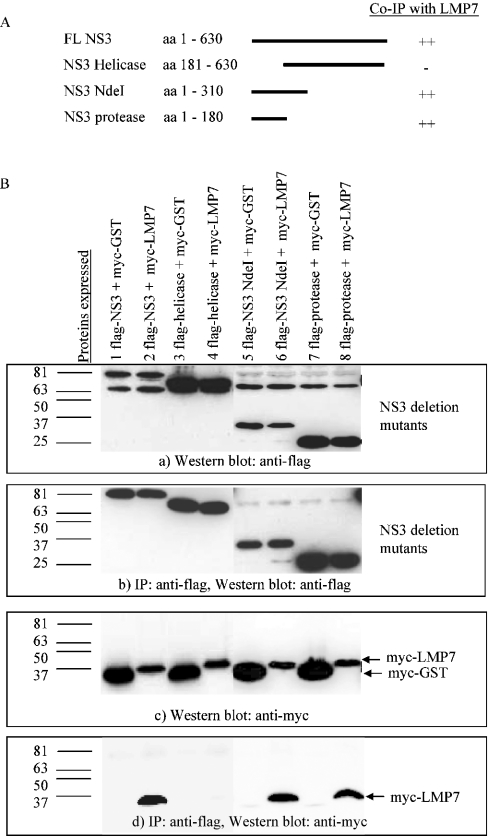

To determine the region in NS3 that interacts with LMP7, several deletion mutants were generated. Constructs expressing the FLAG-tagged full-length NS3 and deletion mutants (Figure 2A) and Myc-tagged LMP7 were co-transfected into COS-7 cells. LMP7 was found to co-immunoprecipitate with the full-length NS3 and the N-terminal region containing the protease domain of NS3 (Figure 2B, lanes 2, 6 and 8), but not with the helicase domain of NS3 (Figure 2B, lane 4). As a negative control, Myc–GST was also co-transfected with the different FLAG–NS3 deletion constructs (Figure 2B, lanes 1, 3, 5 and 7). LMP7 was found to bind specifically to the minimal region containing the protease domain of NS3 (a.a. 1–245) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. LMP7 interacts with the protease domain of NS3.

(A) A schematic representation of the deletion mutants of NS3 and their ability to co-immunoprecipitate with LMP7 is summarized, with (++) and (−) representing strong and no binding respectively. The minimal region that interacts with LMP7 is the protease domain of NS3 (a.a. 1–245). (B) COS-7 cells were transfected with various constructs as indicated (lanes 1–8), and Western blots of total protein (20 μg) showed the FLAG-tagged NS3 full-length and mutant proteins (a) and Myc-tagged LMP7 or GST (c) were expressed. Total protein (150 μg) was incubated with anti-FLAG agarose gel, and one-tenth of the immunoprecipitated proteins were detected with anti-FLAG (b) and the remaining immunoprecipitated proteins probed for co-immunoprecipitated Myc-tagged proteins with anti-Myc antibodies (d). As a negative control, Myc–GST was co-expressed with FLAG-tagged NS3 or deletion mutants: Myc–GST did not bind to all FLAG-tagged proteins (lanes 1, 3, 5 and 7). Myc–LMP7 co-immunoprecipitated with full-length FLAG–NS3 (lane 2), FLAG–NS3 NdeI (lane 6) and FLAG–protease (lane 8), but did not did not bind to FLAG–helicase (lane 4).

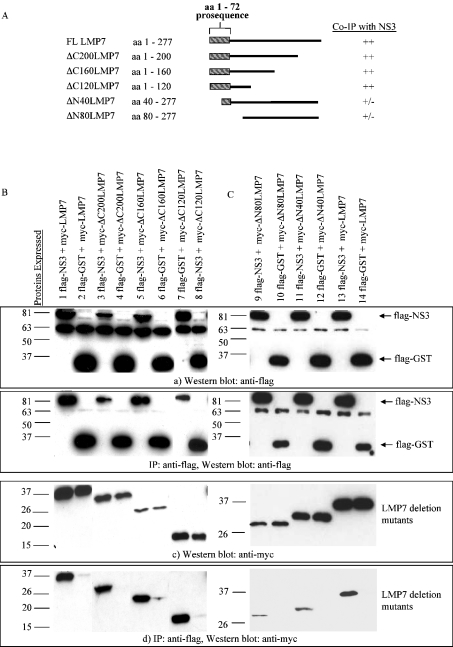

Similarly, to determine the region on LMP7 that interacts with NS3, several deletion mutants of LMP7 were also generated (Figure 3A). Myc-tagged LMP7 and LMP7 deletion mutants were co-expressed with FLAG-tagged NS3 or GST. Deletion from the C-terminus of LMP7 did not affect its co-IP with NS3 (Figure 3B), but deletion of the first 40 amino acids from the N-terminus reduced the association of LMP7 with NS3 drastically (Figure 3C, lanes 9 and 11). GST did not co-immunoprecipitate with any of the LMP7 deletion mutants. These results indicate that NS3 interacts with the N-terminus of LMP7, and the strongest interacting domain was found to be between residues 1–40, which contains the LMP7 pro-sequence (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. NS3 interacts with the pro-sequence of LMP7.

(A) Deletion mutants of LMP7 are schematically depicted. Their ability to co-immunoprecipitate with NS3 are indicated, with (++) and (+/−) representing strong and weak binding respectively. NS3 interacted mainly with the N-terminal region (a.a. 1–40) of LMP7. (B) COS-7 cells were transfected with constructs expressing Myc–LMP7 and C-terminally LMP7 deletion mutants, together with FLAG–NS3. Cell lysate (150 μg) was immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody on an agarose gel, and one-tenth of the immunoprecipitated proteins were probed for FLAG–NS3 with anti-FLAG antibodies (b) and the remaining immunoprecipitated proteins probed for co-immunoprecipitated Myc-tagged LMP7 proteins with anti-Myc antibodies (d). Full-length Myc–LMP7 (lane 1), Myc–ΔC200LMP7 (lane 3), Myc–ΔC160LMP7 (lane 5) and Myc–ΔC120LMP7 (lane 7) co-immunoprecipitated with FLAG–NS3. None of the LMP7 proteins interacted with FLAG–GST (lanes 2, 4, 6 and 8). (C) Similarly, co-immunoprecipitation between full-length FLAG–NS3, and N-terminal-deletion LMP7 mutants was studied. Full-length Myc–LMP7 (lane 13) co-immunoprecipitated with FLAG–NS3, but Myc–ΔN80LMP7 (lane 9) and Myc–ΔN40LMP7 (lane 11) co-immunoprecipitated only weakly with FLAG–NS3. Flag–GST served as a negative control (lanes 10, 12 and 14). For (B) and (C), Western blots of 20 μg of total protein showed appropriate expression of FLAG-tagged NS3 and GST (a), and Myc-tagged LMP7 full-length and deletion mutants (c).

Effect of LMP7 on NS3 protease activity

Since LMP7 interacted with the protease domain of NS3, the effect of LMP7 on NS3 protease activity was investigated. Protease activity was indicated by the cleavage of bead-bound 40-kDa substrate, GST–NS5A5B, at the NS5A–NS5B junction to produce a 30-kDa cleavage product GST–NS5A, and a small NS5B peptide not visible on the gel. The GST–NS3 protease mutant [S138A (Ser138→Ala)] [12] was similarly purified and assayed for protease activity. No activity was detected, indicating that cleavage of GST–NS5A5B substrate was solely due to wild-type NS3 and not to a contaminating bacterial protease (Figure 4B). With increasing amounts of LMP7 added to the protease assay, no notable change in NS3 protease activity was observed (Figure 4D), indicating that under these conditions LMP7 does not have any effect on NS3 protease activity.

Effect of NS3 on proteasome activity

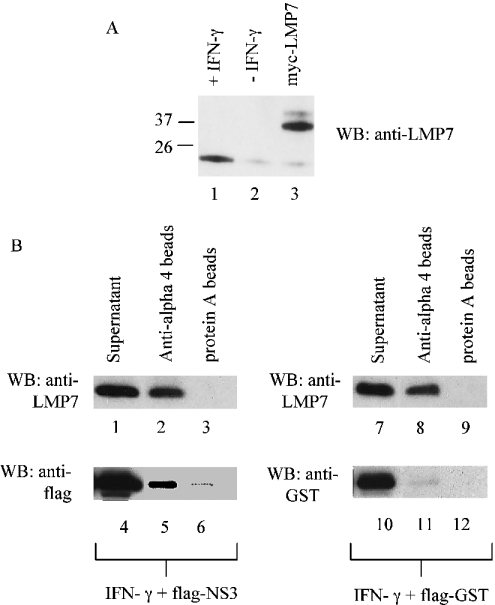

LMP7 is a beta subunit of the 20 S proteasome, which is induced in the presence of IFN-γ (Figure 5A). The 20 S proteasome is associated with several peptidase activities, namely, chymotrypsin-like, trypsin-like and post-acidic activities, which can be assayed by the use of fluorogenic substrates Suc-LLVY-AMC, Boc-LRR-AMC and Z-LLE-AMC respectively. Firstly, co-IP of NS3 with proteasome complex was verified by adding IFN-γ to either NS3-transfected HeLa cells or GST-transfected HeLa cells as a control. Proteasome complex was immunoprecipitated using agarose beads with antibodies against the alpha 4 subunit of the proteasome conjugated to them. As a control, rabbit anti-Myc antibody and Protein A beads were used. The proteasome preparation was checked for the presence of LMP7, as well as the binding of NS3 to the proteasome through LMP7. LMP7 precipitated specifically with the anti-(alpha 4) antibody beads, but not with the Protein A beads. NS3, but not GST, was found to co-immunoprecipitate with the precipitated proteasome complex (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. NS3 binds to the immunopreoteasome complex.

(A) HeLa cells were induced with IFN-γ in HeLa cells (lane 1), uninduced (lane 2) or transfected with a construct expressing Myc–LMP7 as a control (lane 3). Western blots of these cell lysates were probed with an anti-LMP7 antibody. (B) HeLa cells were transfected with constructs expressing FLAG–NS3 or FLAG–GST as control. Following transfection (6 h), the cells were induced with IFN-γ for 24 h. The cells were harvested and the proteasome complex immunoprecipitated from cell lysates with anti-(alpha 4) antibody–agarose beads or with anti-Myc antibody-conjugated Protein A beads. LMP7 induced in the presence of IFN-γ (lanes 1 and 7) and LMP7 present in the immunoprecipitated proteasome complex (lanes 2 and 8) were detected with anti-LMP7 antibodies. LMP7 was not precipitated with anti-Myc antibody bound to Protein A beads (lanes 3 and 9), indicating that LMP7 bound specifically to the proteasome complex. Exogenous FLAG–NS3 (lane 4) and FLAG–GST (lane 10) in cell lysates, and FLAG–NS3 immunoprecipitated with proteasome complex (lane 5) were detected with anti-FLAG antibodies. Flag–GST did not co-immunoprecipitate with the proteasome (lane 11), indicating that FLAG–NS3 bound specifically to the proteasome complex.

To examine the effect of the NS3–LMP7 interaction on the different peptidase activities of the proteasome in the presence of HCV viral proteins, IFN-γ was first added to either the cell line 9-13, which carries a HCV NS3–NS5B replicon, or untransfected Huh-7 cells (parental cell line of 9-13) as control. Both NS3 and LMP7 were detected in 9-13 cells, but NS3 was not detected in the immunoprecipitated proteasomes complex (results not shown). This could be due to the lower expression level of NS3 compared with that in NS3-tranfected HeLa cells.

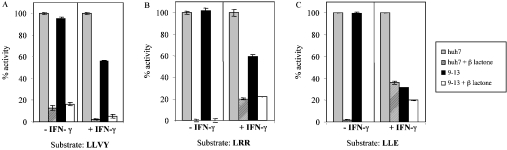

The peptidase activities of the proteasome sample precipitated from 9-13 cells were tested using three different peptide substrates in the presence or absence of 10 μM clasto-lactacystin β-lactone, which is a specific inhibitor of the proteasome. Clasto-lactacystin β-lactone inhibits proteasome activities by covalently modifying the threonine residues of the catalytic beta subunits [30]. Fluorescence obtained from untransfected Huh-7 cells was normalized as 100%. All three peptidase activities of the proteasome dropped significantly upon the addition of β-lactone (Figures 6A–6C), which verified that the peptidase activities observed were truly due to proteasome and not any other contaminating cellular peptidases. In the absence of IFN-γ, there was minimal reduction in proteasome activities, however, after IFN-γ induction, the chymotrypsin-like (Suc-LLVY-AMC) and trypsin-like (Boc-LRR-AMC) activities were reduced to about 55% (Figures 6A and 6B), and the post-acidic activity (Z-LLE-AMC) was reduced, at most, to approx. 40% (Figure 6C). These results suggest that the presence of the HCV proteins specifically inhibits the immunoproteasomes and not the constitutive proteasomes, as reduction in peptidase activities was only observed with the addition of IFN-γ.

Figure 6. Expression of NS3–NS5B viral proteins reduces the LMP7 immunopropteasome activity.

Constitutive proteasome (−IFNγ) and immunoproteasome (+IFNγ) complexes precipitated from either 9-13 or Huh-7 cells were assayed for three different peptidase activities, with or without 10 μM clasto-lactacystin β-lactone (β lactone). The 9-13 line is a Huh-7-derived cell line carrying a self-replicating HCV subgenomic RNA and expresses all the non-structural proteins of HCV. Huh-7 is a liver carcinoma cell line and the parental cell line of the 9-13 line. Fluorogenic substrate Suc-LLVY-AMC (LLVY) (A) was used to test for chymotrypsin-like activity, Boc-LRR-AMC (LRR) (B) for trypsin-like activity, and Z-LLE-AMC (LLE) (C) for post-acidic activity. For each substrate, the fluorescence signals obtained from proteasomes or immunoproteasomes precipitated from Huh-7 cells in the absence of clasto-lactacystin β-lactone treatment, were standardized as 100% activity. All other activities were expressed as a percentage of this control.

DISCUSSION

Our search for a host protein that interacts with the HCV NS3 protein by yeast two-hybrid screen led to the identification of LMP7, a component of the IFN-γ inducible immunoproteasome. The effect of LMP7 on NS3 protease activity and the effect of NS3 on immunoproteasomes were tested. Since LMP7 interacts with the protease region of NS3, we assayed for in vitro NS3 protease activity in the presence and absence of NS3. Under our assay conditions, we were unable to find any change in the protease activity in the presence of LMP7 (Figure 4D). The binding of LMP7 to the NS3 protease domain neither enhanced nor reduced NS3 protease activity. Their interaction probably did not interfere with NS3 catalytic sites or cause any conformational change to NS3, as purified NS3 was found to be active. On the other hand, the recombinant LMP7 expressed might not be folded into its native conformation after purification, even though the purified form could still bind NS3 (Figure 4A). We were unable to test for peptidase activity of LMP7, as this subunit is only functional in the presence of other proteasome proteins of the 20 S catalytic core.

HCV NS3 shows the strongest interaction with the prosequence of LMP7 and binds very weakly (if at all) to LMP7 with the pro-sequence deleted (Figure 3C). Since the replicase exists as a complex during HCV infection and NS3 is a key component of the HCV replicase complex, it is important to determine if proteasome activities are affected in the presence of all the components of the HCV replicase complex. We used the 9-13 stable cell line, which expresses viral non-structural proteins NS3 to NS5B, and the parental cell line, Huh-7, as a control, for this experiment. When the peptidase activities of the constitutive proteasome (i.e. without IFN-γ) were also tested, no changes were observed (Figure 6). Upon IFN-γ induction, all 3 peptidase activities were down-regulated by approx. 50% in the presence of the HCV proteins (Figure 6), indicating that only immunoproteasome activity, but not the constitutive proteasome activity, is affected when the HCV NS proteins are expressed.

We do not know the mechanism of immunoproteasome inhibition by the binding of NS3 to LMP7, however, the following possibilities can be proposed. Firstly, the processing of the LMP7 prosequence may be affected. We do not detect immature LMP7 when NS3 is overexpressed (Figure 5B), indicating that the binding of NS3 to the pro-sequence does not affect the cleavage of the pro-sequence of LMP7. Secondly, NS3 may sequester LMP7, thus lowering the pool available for assembly into immunoproteasomes. This is not likely to be the case, as the LMP7 detected upon IFN-γ induction and the amount of LMP7 detected in the precipitated proteasomes did not seem to change significantly in the presence or absence of NS3 or NS3–NS5B (results not shown).

Thirdly, we cannot rule out the possibility that the assembly of proteasome complexes is affected in the presence of NS3. During proteasome assembly, the different alpha and beta subunits come together to form half-proteasomes, each half consisting of a full alpha ring and a ring of unprocessed beta subunits. The half-proteasomes dimerize and the pro-sequences are autocatalytically removed from the beta subunits, exposing the N-terminal catalytic threonine and rendering the 20 S proteasome proteolytically active [31,32]. Pro-sequences, exclusive to the proteasome β subunits, are important for the assembly of proteasome subunits to generate catalytically active proteasome [33], as deletion of the propeptides results in reduced proteasome activities, defects in proteasome assembly and premature inactivation of the N-terminal active site [34,35]. Therefore the binding of NS3 to the LMP7 pro-sequence could impede the efficient dimerization and processing of the half-proteasomes during assembly, thereby causing reductions in immunoproteasome peptidase activities. Further biochemical characterization is necessary to determine if partially assembled immunoproteasomes accumulates when NS3 is overexpressed.

Fourthly, the composition of immunoproteasomes may be altered, thereby shifting the peptidase activities detected. Immunoproteasomes with these three combinations have been reported: those consisting of LMP7 alone, LMP2 and MECL-1, or all three inducible subunits [36]. The modified proteolytic specificities of these immunoproteasomes generate a different spectrum of peptides from that of constitutive proteasomes. Immunoproteasomes were generally reported to have enhanced cleavage after hydrophobic and basic residues, but a reduced cleavage after acidic residues [37–39].

LMP7 is one of the IFN-γ inducible catalytic subunits of the 20 S proteasome. Proteasomes are multisubunit, multicatalytic proteases that represent a major non-lysosomal proteolytic machinery of eukaryotic cells [40]. Although they are found in all eukaryotic cells, the concentration of proteasomes varies substantially among different cell types. The liver, spleen and lung constitute the highest level of proteasomes and levels are significantly lower in the skeletal muscle, brain and kidney [41]. Proteasomes are also particularly abundant in cancerous cell lines, such as human and rat hepatomas [42]. They are implicated in cellular processes which include the degradation of short-lived regulatory proteins, such as cyclins and transcription regulators, and the removal of misfolded proteins, and are also shown to be involved in apoptosis [43] and to play a central role in the production of peptides for presentation by MHC class I molecules [44]. Inhibitors of the proteasomes were found to block the degradation of most cellular proteins, as well as the generation of the majority of class I-presented peptides [30]. Constitutive proteasomes are reported to be replaced by immunoproteasomes during viral or bacterial infection, and the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response is directed mainly to immunoproteasome-generated T-cell epitopes [45]. It is conceivable that HCV suppresses the activity of immunoproteasomes, leading to pathogenesis and allowing the virus to escape the T-cell mediated immune surveillance mechanism.

Viral evasion of the immune system through the interference of proteasome activity was proposed for several viruses. The hepatitis B virus X protein was reported to interact with the alpha 4 subunit of the proteasome, causing reductions in proteasome activities [46]. LMP7 expression is necessary for the processing of an antigen of HBV (hepatitis B virus) core protein [47] and epitope presentation of the HIV-1 reverse transcriptase [48]. The human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 Tax protein, however, binds to two proteasome subunits, alpha 3 and beta 7, and stimulated proteasome activities [49].

During the acute phase of infection, the presence of inflammatory cytokines drives the synthesis of LMP2, LMP7 and MECL-1. As the infection progresses, cytokine levels decrease, which eventually leads to chronic diseases. In the case of HCV infection, the persistence of the virus could well be exacerbated by the interaction of NS3 with immunoproteasome, thereby reducing the immunoproteasome activities.

The development of anti-HCV drugs has predominantly focused on the antiviral effect of IFN-α and IFN-β. Although the use of IFN-α alone or in combination with ribavirin, a nucleoside analogue, on patients with chronic HCV has yielded encouraging results, these therapies are often accompanied by undesirable side effects [50,51]. The mechanism by which NS3 alters immunoproteasome activity is still not known and much work is needed to understand the biological consequence of this inhibition. Our findings suggest that IFN-γ-induced immunoproteasome activity is inhibited in the presence of non-structural proteins NS3–NS5B, possibly through the interaction of NS3 with LMP7, and consequently, the presentation of viral antigens may be affected. This could eventually contribute to the persistence of HCV in infected patients. The possibility of an alternative mechanism by which HCV could deploy to evade and counter host immune surveillance opens up interesting possibilities for new antiviral therapies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Ralf Bartenschlager (Department of Molecular Virology, Institute of Hygiene, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany) for providing the 9-13 replicon-bearing cell line, Ms Hong He and Mr Meng-Hwee Seah for technical assistance, and our in-house Sequencing Unit for DNA sequencing. This work was supported by grants from the Agency for Science, Technology and Research, Singapore.

References

- 1.Kenny-Walsh E. The natural history of hepatitis C virus infection. Clin. Liver Dis. 2001;5:969–977. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(05)70204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. WHO concerns on hepatitis C. Lancet. 1998;351:1415. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lohmann V., Korner F., Koch J., Herian U., Theilmann L., Bartenschlager R. Replication of subgenomic hepatitis C virus RNAs in a hepatoma cell line. Science. 1999;285:110–113. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5424.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wyatt C. A., Andrus L., Brotman B., Huang F., Lee D. H., Prince A. M. Immunity in chimpanzees chronically infected with hepatitis C viruses: role of minor quasispecies in reinfection. J. Virol. 1998;72:1725–1730. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.1725-1730.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller R. H., Purcell R. H. Hepatitis C virus shares amino acid sequence similarity with pestiviruses and flaviviruses as well as members of two plant virus supergroups. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1990;87:2057–2061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.6.2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robertson B., Myers G., Howard C., Brettin T., Bukh J., Gaschen B., Gojobori T., Maertens G., Mizokami M., Nainan O., et al. Classification, nomenclature, and database development for hepatitis C virus and related viruses: proposals for standardization. Arch. Virol. 1998;143:2493–2503. doi: 10.1007/s007050050479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hijikata M., Mizushima H., Tanji Y., Komoda Y., Hirowatari Y., Akagi T., Kato N., Kimura K., Shimotohno K. Proteolytic processing and membrane association of putative non-structural proteins of hepatitis C virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:10733–10777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hijikata M., Kato N., Ootsuyama Y., Nakagawa M., Shimotohno K. Gene mapping of the putative structural region of the hepatitis C virus genome by in vitro processing analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1991;88:5547–5551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grakoui A., McCourt D. W., Wychowski C., Feinstone S. M., Rice C. M. A second hepatitis C virus-encoded proteinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:10583–10587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hijikata M., Mizushima H., Akagi T., Mori S., Kakiuchi N., Kato N., Tanaka T., Kimura K., Shimotohno K. Two distinct proteinase activities required for the processing of a putative nonstructural precursor protein of the hepatitis C virus. J. Virol. 1993;67:4665–4675. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4665-4675.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartenschlager R. L., Lohmann V., Wilkinson T., Koch J.O. Complex formation between the NS3 serine-type proteinase of the hepatitis C virus and NS4A and its importance for polyprotein maturation. J. Virol. 1995;69:7519–7528. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7519-7528.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomei L., Failla C., Santolini E., De Francesco R., La Monica N. NS3 is a serine protease required for processing of hepatitis C virus polyprotein. J. Virol. 1993;67:4017–4026. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.4017-4026.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tai C. L., Chi W. K., Chen D. S., Hwang L. H. The helicase activity associated with hepatitis C virus non-structural protein 3 (NS3) J. Virol. 1996;70:8477–8484. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8477-8484.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Behrens S. E., Tomei L., De Francesco R. Identification and properties of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of hepatitis C virus. EMBO J. 1996;15:12–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujita T., Ishido S., Muramatsu S., Itoh M., Hotta H. Suppression of actinomycin D-induced apoptosis by the NS3 protein of hepatitis C virus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996;229:825–831. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishido S., Hotta H. Complex formation of the nonstructural protein 3 of hepatitis C virus with p53 tumor suppressor. FEBS Lett. 1998;438:258–262. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01312-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakamuro D., Furukawa T., Takegami T. Hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein NS3 transforms NIH 3T3 cell. J. Virol. 1995;69:3893–3896. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3893-3896.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zemel R., Gerechet S., Greif H., Bachmatove L., Birk Y., Golan-Goldhirsh A., Kunin M., Berdichevsky Y., Benhar I., Tur-Kaspa R. Cell transformation induced by hepatitis C virus NS3 serine protease. J. Viral Hepat. 2001;8:96–102. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2001.00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dick T. P., Nussbaum A. K., Deeg M., Heinemeyer W., Groll M., Schirle M., Keilholz W., Stevanovic S., Wolf D. H., Huber R., et al. Contribution of proteasomal beta-subunits to the cleavage of peptide substrates analyzed with yeast mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:25637–25646. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nussbaum A. K., Dick T. P., Keilholz W., Schirle M., Stevanovic S., Dietz K., Heinemeyer W., Groll M., Wolf D. H., Huber R., et al. Cleavage motifs of the yeast 20 S proteasome beta subunits deduced from digests of enolase 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:12504–12509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orlowski M. The multicatalytic proteinase complex, a major extralysosomal proteolytic system. Biochemistry. 1990;29:10289–10297. doi: 10.1021/bi00497a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Belich M. P., Glynne R. J., Senger G., Sheer D., Trowsdale J. Proteasome components with reciprocal expression to that of the MHC-encoded LMP proteins. Curr. Biol. 1994;4:769–776. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00174-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Groettrup M., Kraft R., Kostka S., Standera S., Stohwasser R., Kloetzel P. M. A third interferon gamma induced subunit exchange in the 20 S proteasome. Eur. J. Immunol. 1996;26:863–869. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lim S. P., Khu Y. L., Hong W., Tay A., Ting A. E., Lim S. G., Tan Y. H. Identification and molecular characterization of the complete genome of a Singapore isolate of hepatitis C virus: sequence comparison with other strains and phylogenetic analysis. Virus Genes. 2001;23:89–95. doi: 10.1023/a:1011143731677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manser E., Huang H. Y., Loo T. H., Chen X. Q., Dong J. M., Leung T., Lim L. Expression of constitutively active α-PAK reveals effects of the kinase on actin and focal complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997;17:1129–1143. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sing W. T., Lee C. L., Yeo S. L., Lim S. P., Sim M. M. Arylalkylidene rhodanine with bulky and hydrophobic functional group as selective HCV NS3 protease inhibitor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001;11:91–94. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00610-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khu Y. L., Koh E., Lim S. P., Tan Y. H., Brenner S., Lim S. G., Hong W., Goh P. Y. Mutations that affect dimmer formation and helicase activity of the hepatitis C virus helicase. J. Virol. 2001;75:205–214. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.1.205-214.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sung V. M., Shimodaira S., Doughty A. L., Picchio G. R., Can H., Yen T. S., Lindsay K. L., Levine A. M., Lai M. M. Establishment of B-cell lymphoma cell lines persistently infected with hepatitis C virus in vivo and in vitro: the apoptotic effects of virus infection. J. Virol. 2003;77:2134–46. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.3.2134-2146.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zignego A. L., Macchia D., Monti M., Thiers V., Mazzetti M., Foschi M., Maggi E., Romagnani S., Gentilini P., Brechot C. Infection of peripheral mononuclear blood cells by hepatitis C virus. J. Hepatol. 1992;15:382–386. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(92)90073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Craiu A., Gaczynska M., Akopian T., Gramm C. F., Fenteany G., Goldberg A. L., Rock K. L. Lactacystin and clasto-lactacystin β-lactone modify multiple proteasome β-subunits and inhibit intracellular protein degradation and major histocompatibility complex class I antigen presentation. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:13437–13445. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.13437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen P., Hochstrasser M. Autocatalytic subunit processing couples active site formation in the 20 S proteasome to completion of assembly. Cell. 1996;86:961–972. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80171-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmidtke G., Schmidt M., Kloetzel P. M. Maturation of mammalian 20 S proteasome: purification and characterization of 13 S and 16 S proteasome precursor complexes. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;268:95–106. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lowe J., Stock D., Jap B., Zwickl P., Baumeister W., Huber R. Crystal structure of the 20 S proteasome from the archaeon T. acidophilum at 3.4 Å resolution. Science. 1995;268:533–539. doi: 10.1126/science.7725097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arendt C. S., Hochstrasser M. Eukaryotic 20 S proteasome catalytic propeptides prevent active site inactivation by N-terminal acetylation and promote particle assembly. EMBO J. 1999;18:3575–3585. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.13.3575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jager S., Groll M., Huber R., Wolf D. H., Heinemeyer W. Proteasome beta-type subunits: unequal roles of propeptides in core particle maturation and a hierarchy of active site function. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;291:997–1013. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Groettrup M., Khan S., Schwarz K., Schmidtke G. Interferon-gamma inducible exchanges of 20 S proteasome active site subunits: why? Biochimie. 2001;83:367–372. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(01)01251-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Driscoll J., Brown M. G., Finley D., Monaco J. J. MHC-linked LMP gene products specifically alter peptidase activities of the proteasome. Nature. 1993;365:262–264. doi: 10.1038/365262a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gaczynska M., Rock K. L., Goldberg A. L. Gamma-interferon and expression of MHC genes regulate peptide hydrolysis by proteasomes. Nature. 1993;365:264–267. doi: 10.1038/365264a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gaczynska M., Rock K. L., Spies T., Goldberg A. L. Peptidase activities of proteasomes are differentially regulated by the major histocompatibility complex-encoded genes for LMP2 and LMP7. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:9213–9217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coux O., Tanaka K., Goldberg A. L. Structure and functions of the 20 S and 26 S proteasomes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1996;65:801–847. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.004101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanaka K., Ii K., Ichihara A. A high molecular weight protease in the cytosol of rat liver. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:15197–15203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ichihara A., Tanaka K., Andoh T., Shimbara N. Regulation of proteasome expression in developing and transformed cells. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 1993;33:173–180. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(93)90016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hilt W., Wolf D. H. Proteasomes: destruction as a programme. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1996;21:96–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rock K. L., Gramm C., Rothstein L., Clark K., Stein R., Dick L., Hwang D., Goldberg A. L. Inhibitors of the proteasome block the degradation of most cell proteins and the generation of peptides presented on MHC class I molecules. Cell. 1994;78:761–771. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90462-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khan S., van den Broek M., Schwarz K., de Giuli R., Diener P. A., Groettrup M. Immunoproteasomes largely replace constitutive proteasomes during an antiviral and antibacterial immune response in the liver. J. Immunol. 2001;167:6859–6868. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.12.6859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hu Z., Zhang Z., Doo E., Coux O., Goldberg A. L., Liang T. J. Hepatitis B virus X protein is both a substrate and a potential inhibitor of the proteasome complex. J. Virol. 1999;73:7231–7240. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7231-7240.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sijts A. J., Ruppert T., Rehermann B., Schmidt M., Koszinowski U., Kloetzel P. M. Efficient generation of a hepatitis B virus cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope requires the structural features of immunoproteasomes. J. Exp. Med. 2000;191:503–514. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sewell A. K., Price D. A., Teisserenc H., Booth B. L., Gileadi U., Flavin F. M., Trowsdale J., Phillips R. E., Cerundolo V. Interferon gamma exposes a cryptic cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. J. Immunol. 1999;162:7075–7079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hemelaar J., Bex F., Booth B., Cerundolo V., McMichael A., Daenke S. Human T cell leukemia virus type 1 Tax protein binds to assembled nuclear proteasomes and enhances their proteolytic activity. J. Virol. 2001;75:11106–11115. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.22.11106-11115.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Di Bisceglie A. M., Hoofnagle J. H. Optimal therapy of hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2002;36:S121–S127. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Neumann A. U., Lam N. P., Dahari H., Gretch D. R., Wiley T. E., Layden T. J., Perelson A. S. Hepatitis C viral dynamics in vivo and the antiviral efficacy of interferon-alpha therapy. Science. 1998;282:103–107. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5386.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]