Abstract

MAIDS (murine AIDS) is caused by infection with the murine leukaemia retrovirus RadLV-Rs and is characterized by a severe immunodeficiency and T-cell anergy combined with a lymphoproliferative disease affecting both B- and T-cells. Hyperactivation of the cAMP-protein kinase A pathway is involved in the T-cell dysfunction of MAIDS and HIV by inhibiting T-cell activation through the T-cell receptor. In the present study, we show that MAIDS involves a strong and selective up-regulation of cyclo-oxygenase type 2 in the CD11b+ subpopulation of T- and B-cells of the lymph nodes, leading to increased levels of PGE2 (prostaglandin E2). PGE2 activates the cAMP pathway through G-protein-coupled receptors. Treatment with cyclo-oxygenase type 2 inhibitors reduces the level of PGE2 and thereby reverses the T-cell anergy, restores the T-cell immune function and ameliorates the lymphoproliferative disease.

Keywords: cAMP, cyclo-oxygenase type 2, immunodeficiency, prostaglandin E2, retroviral infection, T-cell

Abbreviations: COX-2, cyclo-oxygenase type 2; HRP, horseradish peroxidase; mAb, monoclonal antibody; MAIDS, murine AIDS; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; PKA, protein kinase A; TCR, T-cell receptor

INTRODUCTION

MAIDS (murine AIDS) is caused by infection of C57BL/6 mice with the RadLV-Rs retrovirus [1]. The syndrome is characterized by lymphoproliferation, hypergammaglobulinaemia and a severe T-cell anergy leading to increased susceptibility to opportunistic infections, neoplasms and ultimately death at 16–24 weeks postinfection. Both T- and B-cells are required for the progression of MAIDS [2–4], and the course of the disease follows a pattern of initial polyclonal activation and proliferation of T- and B-cells, hypergammaglobulinaemia and development of lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly. Subsequently, a state of immunodeficiency develops. Despite the polyclonal non-specific activation, the CD4+ T-cell subset loses the responsiveness to mitogens and antigenic stimuli and becomes anergic and B-cell dysfunction ensues later [5–8].

Direct cell contact-dependent interactions between T- and B-cells play a key role in the disease development. Blocking these interactions with anti-CD40L [9], CTLA4Ig [10,11] or antibodies to intercellular cell-adhesion molecule 1 and lymphocyte function associated antigen [12] inhibits the disease progression to various degrees. Several lines of evidence also suggest that soluble factors may be involved [13], although these remain unknown. The requirement of T- and B-cell interactions is further supported by observations that animals depleted of CD4+ T-cells [3,14] or B-cells [4] are resistant to MAIDS. However, it has been reported that T-cell immunodeficiency can occur independently of overt B-cell pathology in CD4 knockout mice [15]. In these mice, T-cell immunodeficiency develops with impaired proliferative responses after TCR (T-cell receptor) stimulation without any B-cell abnormalities such as hypergammaglobulinaemia and splenomegaly.

Since it is unlikely that the viral genome encodes conventional superantigens [12,16] or other antigens responsible for the polyclonal activation of T- and B-cells, and since the T-cell dysfunction involves both naive and memory CD4+ T-cells [17], antigen-independent mechanisms may be crucial in the pathogenesis. We have recently reported that the intracellular level of cAMP is strongly increased in T-cells from MAIDS mice leading to constitutive activation of PKA (protein kinase A) type I [18]. cAMP inhibits T-cell activation by eliciting a multistep pathway involving activation of PKA type I that phosphorylates and activates Csk localized in lipid rafts of the plasma membrane. Activated Csk then phosphorylates Lck on an inhibitory tyrosine residue and thereby inhibits T-cell activation induced by the TCR [19,20]. Blocking PKA type I restores T-cell function in vitro in MAIDS [18] as well as in HIV infection [21,22]. However, the agent inducing the increase in cAMP levels has not been identified. Because both MAIDS and HIV infection are associated with generalized immune activation and polyclonal T-cell anergy, we have hypothesized that an inflammatory humoral factor may induce the panclonal T-cell anergy characteristic of these conditions. In the present study, we report that there is a significant increase in PGE2 (prostaglandin E2) secretion by mixed lymph node cells in MAIDS. We further show that the increase in PGE2 levels is caused by up-regulation of COX-2 (cyclo-oxygenase type 2) in a population of CD11b+ T- and B-cells that reside in lymph nodes of MAIDS mice. Both in vitro and in vivo inhibition of COX-2 by specific COX-2 inhibitors restore the T-cell function and ameliorate the lymphoproliferative disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and cell suspension

Male C57BL/6 mice were bred in our facility. Mice were injected twice intraperitoneally, at the age of 4 and 5 weeks, with 0.25 ml of the cell-free viral extract. Age-matched control mice were injected twice intraperitoneally with 0.25 ml of PBS. At different times postinfection, the mice were killed by CO2 asphyxiation. Peripheral lymph nodes (inguinal, axillary and cervical) were dissociated with syringes to obtain single-cell suspensions and passed through a nylon cell strainer, washed three times with complete RPMI 1640 medium and counted on a Thoma cytometer after Trypan Blue exclusion before further analysis or cell culture. For in vivo experiments, osmotic pumps (100 μl; Alzet) were implanted subcutaneously. In some experiments, peripheral and mesenteric lymph nodes and spleens were dissected and weighed. All studies on mice with MAIDS were performed under a permit given to the University of Liège Animal Facility from the Belgian Ministry for Agriculture and with permission from the Local Animal Ethics Committee.

Virus

Viral extract was prepared from lymph nodes of mice injected 2 months earlier with RadLV-Rs as described previously [18]. Lymph nodes were collected, ground in PBS and centrifuged twice at 1.5×104 g for 30 min. This acellular viral extract was stored in liquid nitrogen. The XC plaque assay was used for quantification, and showed that the viral preparation contained 103 PFU (plaque forming units) of ecotropic virus/ml.

Compounds

Indomethacin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.) was dissolved in DMSO. Meloxicam (Boehringer Ingelheim, Gagny, France) was delivered as an injection compound and diluted in PBS, whereas rofecoxib (Merck, Sharp and Dome) and celecoxib (Amersham Biosciences) were extracted from tablets by organic phase extraction (Drug Discovery Laboratory, Oslo, Norway) and dissolved in DMSO for cell culture experiments.

Antibodies

Rabbit anti-COX-1 and -2 polyclonal antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used for Western-blot experiments with an HRP (horseradish peroxidase)-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (BD Biosciences, La Jolla, CA, U.S.A.) in the second layer. For flow cytometry, the following mAbs (monoclonal antibodies) obtained from BD Biosciences were used: phycoerythrin-conjugated CD4/L3T4 (YTS.191.1), FITC-conjugated CD45R/B220 (RA3-6B2), FITC-conjugated CD11b/Mac-1 (M1/70), FITC-conjugated CD161/NK-1.1 (PK136), FITC-conjugated CD8a (Ly-2) and CD16/CD32 (FcγIII/II receptor) (2.4G2). The CD3 mAb (145-2C11) used to activate T-cells was purified in our laboratory.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Flow cytometry was performed on a FACStar-plus flow cell sorter with Cellquest software (Becton Dickinson). Viable lymphocytes were gated on forward and side scatter, and analysed for FITC and phycoerythrin fluorescence after excitation at 488 nm. For cell sorting, 60×106 cells were incubated with anti-FcγRII (Fc block) to prevent non-specific interactions, before labelling for 20 min on ice with the fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies. CD4+ and CD8+ T- and B-cells were positively selected. The T-cell subpopulations were sorted by co-expression of CD3 and CD4 or CD8, whereas the B-cells were sorted by B220 expression. The CD11b− cells were negatively selected on the basis of the absence of CD11b expression on the cell surface. For each sorting, the selected fraction was reanalysed by flow cytometry to assess purity, which was always higher than 97%. For the analysis of CD11b+ by flow cytometry, the antibody was titrated, samples were blocked with anti-CD32 before analysis and the isotype-matched antibody was used as control.

PGE2 determination

Cultures of lymph-node cells from control and infected mice were incubated for 48 h and the supernatants (500 μl) were collected and mixed with an equal volume of 80% (v/v) ethanol and 10 μl of ice-cold acetic acid and centrifuged to remove the protein. Supernatants were collected and run through Amprep C18 minicolumns, primed with 2 column volumes of 10% ethanol. The columns were then washed with 1 vol. of water and 1 vol. of hexane, after which PGE2 was eluted with 2×0.75 ml of ethyl acetate. The eluate was freeze-dried under nitrogen, each fraction was reconstituted in 100 μl of assay buffer and PGE2 was assayed using an Amersham EIA kit according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunohistochemistry and immunocytochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on 2 μm histological sections of tissues fixed in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde and embedded in plastic (JB4-JBPolysciences). Sections were permeabilized with trypsin (0.24%) for 10 min at 37 °C and then treated with Tween 20 (2%, v/v) in PBS for 30 min at 37 °C. Endogenous peroxidases were quenched by incubation with H2O2 (1%) for 30 min at room temperature (20 °C) and the sections were saturated with normal goat serum (15%, v/v) for 1 h at 37 °C to block unspecific binding. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary polyclonal rabbit anti-COX-1 or rabbit anti-COX-2 antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and then incubated for 2 h with a biotinylated goat anti-rabbit antibody. The latter was detected by ABC complex (Novostain Super ABC kit; Novocastra, Newcastle, U.K.). Peroxidase was revealed using diaminobenzidine (DakoCytomation A/S, Glostrup, Denmark), which gives a brown precipitate in the presence of H2O2. Sections were counterstained with haematoxylin–eosin (Sigma). To verify the specificity, sections were incubated with normal rabbit serum instead of primary antibody. Similarly, smears of LN cells were subjected to COX-2 staining detected by an FITC- or tetramethylrhodamine β-isothiocyanate-labelled goat anti-rabbit antibody and double stained with Mac-3 or CD11b antibodies (see above for details).

Cell homogenization and immunoblotting

Cells (50×106) were homogenized by sonication (2×15 s) on ice in a buffer containing 10 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.1), 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100 and 10 μg/ml each of the protease inhibitors chymostatin, leupeptin, pepstatin A and antipain (Penninsula Laboratories, Belmont, CA, U.S.A.), and centrifuged for 30 min (15000 g) to remove the insoluble material. Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories). For immunoblotting, 10 μg of protein was separated by SDS/PAGE (10% gel), transferred on to PVDF membranes and incubated with antibodies in TBS/Tween with 5% non-fat dry milk and 0.1% BSA (Blotto). Primary antibodies were detected by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and ECL® (Amersham Biosciences).

Proliferation assays

Proliferation assays were performed by incubation of 0.1×106 mixed lymph node cells in a 100 μl volume in flat-bottomed 96-well microtitre plates. Activation was achieved by subsequent addition of soluble anti-CD3 antibodies (clone 2C11) at a final dilution of 4 μg/ml for the experiments shown. The optimal concentration of antibody was titrated carefully in the initial set-up, and parallel experiments with several different dilutions of antibody were always performed. Proliferation was analysed by incubating cells for 72 h, during which [3H]thymidine (0.4 μCi) was included for the last 4 h and collected with a cell harvester (Skatron, Sterling, VA, U.S.A.) on to glass fibre filters. The incorporated precursor was counted in a scintillation analyser (Tri-Carb, Packard, Meriden, CT, U.S.A.). cAMP analogues, when used, were added 30 min before activation by the addition of anti-CD3 antibodies. Sp- and Rp-8-Br-cAMPS were purchased from BioLog Life Science Company (Bremen, Germany) and were dissolved to concentrations of 10 mM in PBS and the concentrations were calculated using the molar absorption coefficients given by the manufacturer.

Statistical analyses

For comparison of two independent groups of animals, the Mann–Whitney U test (two-tailed) was used, whereas Wilcoxon matched pairs test was used for paired comparisons. Statistical and curve fit analyses were performed using Statistica (Statsoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, U.S.A.) and Sigma Plot (Jandel Corporation, Erkrath, Germany) software packages respectively. Results are given as medians and 25–75th percentiles unless otherwise stated; P values are two-sided and considered significant when <0.05.

RESULTS

Increased secretion of PGE2 by lymph node mononuclear cells of retrovirus-infected mice

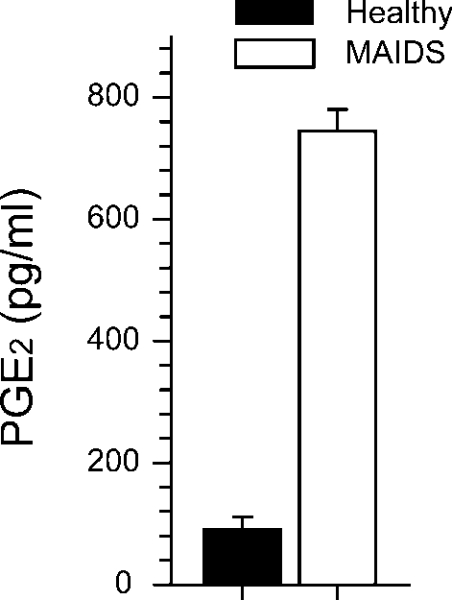

Mixed mononuclear cells from the lymph nodes of retrovirus-infected and aged-matched control mice were isolated and cultured for 48 h in the absence of any mitogenic stimuli. The levels of PGE2 were measured and found to be 7–8-fold higher in the supernatants from infected lymph node cells compared with that of controls (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Secretion of PGE2 by lymph node cells from control and MAIDS mice in vitro.

Mixed lymph node mononuclear cells from retrovirus-infected mice (0.5×106 cells/well) at 20 weeks postinfection (n=5) and age-matched control mice (n=3) were cultured for 48 h in the absence of any mitogenic stimulus, after which secreted levels of PGE2 were measured in the supernatants by ELISA. The bars represent means±S.E.M., P<0.05, Mann–Whitney U test.

Up-regulation of COX-2 in the lymph nodes of retrovirus-infected mice

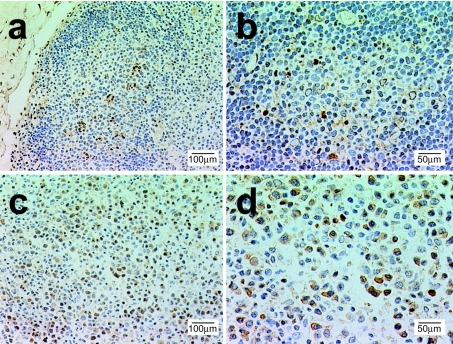

We immunostained sections of lymph nodes with an anti-COX-2 mAb. Very few cells (1.8%) were COX-2+ in the control lymph nodes. Most of these were limited to the germinal centres and were characterized by a typical macrophage morphology with phagocytic inclusions evoking tingible bodies (Figure 2). Looking at lymph nodes from MAIDS mice, we observed alteration of the gross architecture and loss of germinal centres. Furthermore, in comparison with their paucity in the control lymph nodes, the proportion of COX-2+ cells strikingly increased (38%) in the infected lymph nodes (Figure 2). In these sections, we mostly observed cytoplasmic staining for COX-2 in large activated cells frequently displaying mitotic figures. These cells were diffusely distributed throughout the lymph nodes. Up-regulation of COX-2 was seen as early as 3–4 weeks postinfection (not shown).

Figure 2. Level of expression of COX-2 is increased in lymph nodes of MAIDS-infected mice.

Lymph nodes were fixed, plastic-embedded, sectioned and subjected to COX-2 immunohistochemical staining (brown stain). (a) Normal control lymph node with the germinal centre stained for COX-2. (b) Normal lymph node at higher magnification. Note that cells staining positive for HRP-colour reaction (brown colour) are ‘tingible body’ macrophages with dense, ingested material. (c) Lymph node from MAIDS mouse (20 weeks postinfection). Note the altered morphology and architecture. (d) Higher magnification of MAIDS lymph node stained for COX-2. Note that a number of cells have brown immunostaining in the cytoplasm and numerous mitotic figures. Blocking with antigen competed COX-2 staining (not shown). Representative observations from the examination of three pairs of infected and healthy mice are shown.

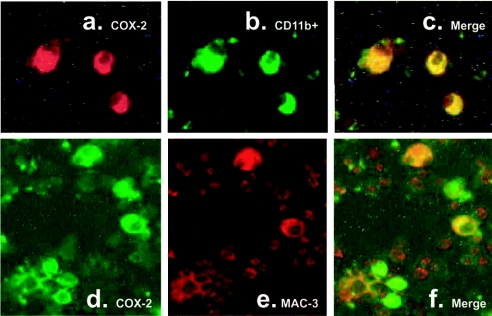

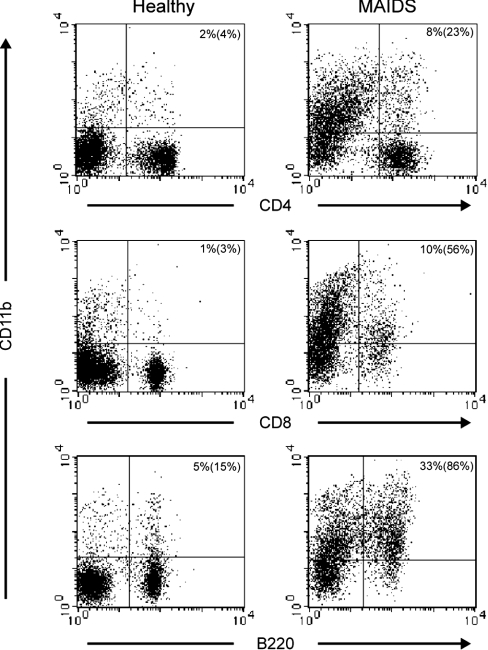

Distinct subsets of CD11b+ cells up-regulate COX-2 in the lymph nodes of retrovirus-infected mice

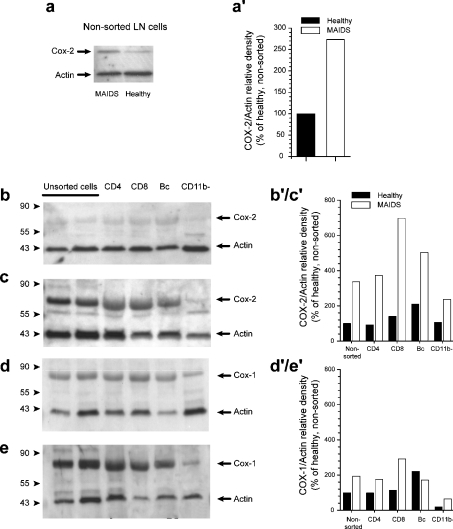

To clarify the lineage of the cells responsible for PGE2 secretion during retroviral infection, we performed double immunostaining on cell smears from infected and control lymph nodes. As expected, less than 0.1% of the cells were COX-2+ in the control mice. In sharp contrast, 50% of the cells were COX-2+ in the infected mice. All macrophages (as identified by Mac-3 expression) were strongly COX-2+ (Figures 3d–3f). Interestingly, a significant fraction of COX-2+ cells did not express Mac-3, suggesting that they belonged to another cell subset. However, independent of Mac-3 expression, all COX-2+ cells strongly expressed the integrin α-subunit CD11b (Figures 3a–3c). Next, we examined mixed lymph-node cells by immunoblotting for COX-2 and demonstrated a 2.5-fold increase in expression compared with healthy mice (Figures 4a and 4a′). Subsequently, we sorted CD4+ T-cells, and CD8+ T- and B-cells, from infected lymph nodes to high purity and performed immunoblot analysis on protein extracts from sorted cells. All three subsets were strongly positive for COX-2 when purified from MAIDS mice but not when purified from control mice (Figures 4b, 4c and 4b′/c′). In contrast, extracts prepared from negatively selected CD11b− cells had low levels of reactivity with anti-COX-2 mAb (Figures 4b and 4c), but still an increase in MAIDS was observed (Figure 4b′/c′). Together, this indicates that a population of CD11b+ cells belonging to CD4+, CD8+ and B-lymphocyte subsets is responsible for COX-2 up-regulation and PGE2 secretion. Levels of COX-1 were also somewhat altered compared with healthy mice, but to a lesser extent when compared with COX-2 (Figures 4d, 4e and 4d′/e′). To rule out a possible contamination of these purified lymphocyte fractions by another cell type expressing CD11b, we analysed the expression of CD11b on lymphocytes (Figure 5). In control mice, less than 5% of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells and approx. 15% of B-cells expressed CD11b. Surprisingly, we observed a strong up-regulation of CD11b expression in the three lymphocyte subsets in infected cells.

Figure 3. COX-2-expressing cells are positive for CD11b.

Smears of mixed lymph node cells from MAIDS mice were subjected to dual immunofluorescence staining for COX-2 (a, d) and CD11b (b) or Mac-3 (e). As seen in the image overlays (c, f), COX-2-expressing cells were always positive for CD11b, whereas a subpopulation of COX-2-positive cells were expressing Mac-3.

Figure 4. Expression of COX-2 and COX-1 by different subsets of lymph node lymphocytes in normal and MAIDS-infected mice.

Unsorted lymph-node (LN) cells (a) and FACS-sorted CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells, B220+B-cells and negatively selected CD11b− cells from normal (a, b, d) and infected (a, c, e) mice were lysed and 10 μg of protein from each sample was subjected to immunoblot analysis for the expression of COX-2 (a–c) or Cox-1 (d–e). Blots were concomitantly reacted with antibodies to actin as control. One of the three experiments with different animals is shown. Blots were analysed by densitometry (www.scion.com) and COX expression was normalized to actin (a′, b′/c′, d′/e′).

Figure 5. MAIDS lymph node cells have high levels of CD11b.

Expression of CD11b by different subsets of lymph node lymphocytes from infected and control mice was analysed by flow cytometry. Representative observations from the examination of three pairs of infected and healthy mice are shown. Numbers in the upper right quadrants refer to the percentage of upper right versus total number of cells and numbers in parentheses refer to the percentage of upper right versus both right quadrants.

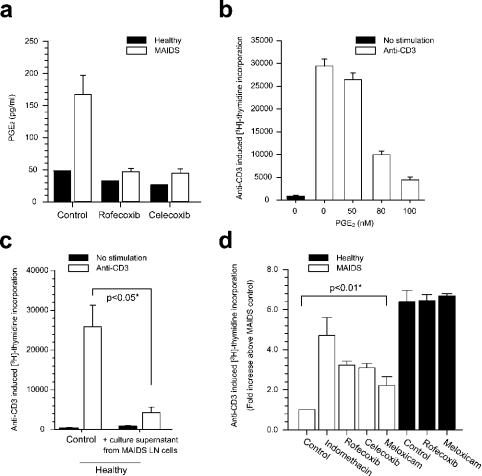

In vitro inhibition of PGE2 production restores T-cell responses

Next, we addressed the effect of COX-2 inhibitors ex vivo on PGE2 secretion and T-cell responses. As seen in Figure 6, mixed lymph node cells from MAIDS mice secreted 5–6-fold more PGE2 when compared with lymph node cells from healthy mice, in agreement with the observations in Figure 1, and secreted 15-fold more PGE2 in the presence of lipopolysaccharide (results not shown). Furthermore, the non-selective inhibitor indomethacin decreased PGE2 levels in culture to levels of healthy mice (not shown). More interestingly, the COX-2-selective inhibitors rofecoxib and celecoxib also abolished the retrovirus-induced increase in PGE2 levels at submicromolar concentration (0.125 μM), where the selectivity for inhibition of COX-2 is optimal [23], whereas no such effect was observed on normal T-cells. PGE2 (Figure 6b) and supernatant from cultures of MAIDS lymph node cells (Figure 6c) inhibited anti-CD3-induced proliferation of T-cells from healthy mice. T-cell proliferative responses induced by cross-ligation of anti-CD3 mAb were strongly inhibited in infected mice and usually remained below 20% of the responses in control mice. In the presence of indomethacin, proliferation levels increased 4–5-fold, almost reaching the responses from cells of non-infected animals. Rofecoxib, celecoxib and meloxicam had similar, although slightly less pronounced, effects on proliferation. In T-cells from retrovirus-infected mice, the concentrations of rofecoxib and celecoxib that produced half-maximal effects (ED50) were approx. 0.01 and 0.03 μM respectively (not shown). In contrast, the proliferative responses of lymphocytes from healthy mice were not modified by any of the compounds mentioned above.

Figure 6. Effect of COX-2-specific and non-selective inhibitors on secretion of PGE2 and T-cell immune responses in mixed lymph node cultures ex vivo.

(a) Lymph node mononuclear cells (0.3×106 cells/well) from retrovirus-infected mice at 20 weeks postinfection (open bars, n=5) and from a pool of three age-matched control mice (black bars) were cultured for 48 h with and without the COX-2-specific inhibitors rofecoxib (0.125 μM) and celecoxib (0.125 μM). Level of secretion of PGE2 was measured by ELISA in the supernatants. Bars represent means±S.E.M. (b) T-cell proliferative responses were assessed in a mixed population of lymph node mononuclear cells from healthy mice (n=3) in the absence and presence of PGE2. T-cell activation was accomplished by cross-ligation of anti-CD3 (mAb 2C11; 4 g/ml), proliferation was assessed after 72 h culture, during which [3H]thymidine was included for the last 4 h, and data were normalized with regard to proliferative response in infected mice in the absence of any COX inhibitor. The bars represent means±S.E.M. (c) T-cell proliferative responses were assessed in a mixed population of lymph node mononuclear cells from healthy mice (n=3) in the absence and presence of culture supernatant from culture of MAIDS LN cells for 24 h. T-cell activation and proliferation assays were conducted as in (b). The bars represent means±S.E.M., *P<0.05 by Mann–Whitney U test. (d) T-cell proliferative responses were assessed in a mixed population of lymph node mononuclear cells from infected (n=4) and age-matched control mice (n=3) in the absence and presence of indomethacin (50 ng/ml), rofecoxib (0.125 μM), celecoxib (0.125 μM) or meloxicam (2.5 μg/ml). T-cell activation and proliferation assays were conducted as in (b). The bars represent means±S.E.M., *P<0.01 by Mann–Whitney U test.

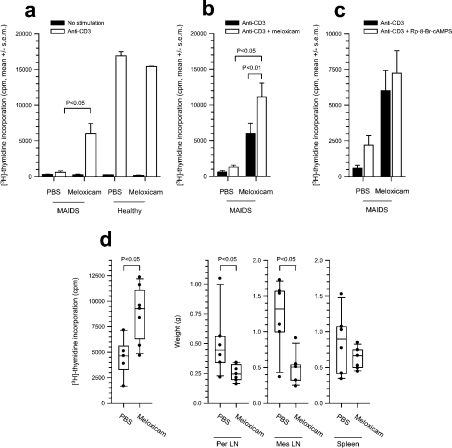

In vivo treatment of retrovirus-infected mice with COX-2 inhibitors reverses T-cell dysfunction and ameliorates the lymphoproliferative disease

To examine the effect of COX-2 inhibitors in vivo, infected and healthy mice were treated with the water-soluble meloxicam, which has a selectivity profile similar to that of celecoxib [23], administered by subcutaneous implantation of osmotic pumps at 2.8 mg·kg−1·day−1, which corresponds to the recommended dose for use in humans when taking into account the 7-fold higher clearance in rodents. When T-cell function was assessed in lymph node cells from meloxicam-treated and PBS-treated infected mice, it was clear that whereas PBS-treated infected animals had very low anti-CD3-induced proliferative responses, infected mice that received meloxicam for 14 days had at least 10-fold higher T-cell responses to anti-CD3 (Figure 7a, P<0.05). When meloxicam was again added to the cell cultures during the 3-day in vitro T-cell proliferation assay to prevent release from the in vivo inhibition by meloxicam and thereby re-activation of COX-2, the immune response in the meloxicam-treated group was 2-fold higher than the response without the addition of meloxicam in vitro (Figure 7b, P=0.005), and when compared with MAIDS mice that received PBS in vivo, the effect was again significant (P<0.05). In contrast, only MAIDS mice that received PBS in vivo and not meloxicam-treated mice demonstrated increased immune responses when the PKA type I-selective cAMP antagonist, Rp-8-Br-cAMPS, was added to the anti-CD3-stimulated mixed lymph node cultures in vitro (Figure 7c). The fact that the effect of cAMP antagonist is absent from meloxicam-treated MAIDS mice indicates that in vivo meloxicam treatment decreases or removes the cAMP-induced T-cell dysfunction of MAIDS and restores immune function.

Figure 7. Effect of in vivo treatment of MAIDS mice with meloxicam on T-cell immune function.

(a) Osmotic pumps (Alzet; 100 μl) with meloxicam (release rate of 70 μg·animal−1·day−1) or PBS were implanted subcutaneously in MAIDS mice (14 weeks postinfection) and healthy mice for 14 days. Subsequently, T-cell proliferative responses were assessed in vitro in a mixed population of unsorted lymph node mononuclear cells from meloxicam-treated animals and animals that received PBS by [3H]thymidine incorporation. T-cell activation was accomplished in all samples by cross-ligation of anti-CD3 (mAb 2C11; 4 μg/ml). Cells were cultured for 72 h, during which [3H]thymidine was included for the last 4 h. Mean±S.E.M. for each group is shown. The effect of meloxicam treatment on anti-CD3-stimulated proliferation of cells from MAIDS mice compared with that of MAIDS mice that received PBS is significant (P<0.05). (b) Mixed lymph node cultures from the groups of mice in (a) treated in vivo with meloxicam or PBS and where meloxicam (2.5 μg/ml) was again added to the medium in cell culture in vitro; anti-CD3-induced T-cell proliferation was assessed as in (a), and the effect of adding again meloxicam in vitro was assessed by comparing with the response in cells treated with meloxicam in vivo but with no in vitro addition (P=0.005). (c) Mixed lymph node cultures from the groups of mice in (a) treated in vivo with meloxicam or PBS and where Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (0.5 mM) was added in cell culture in vitro; anti-CD3-induced T-cell proliferation was assessed as in (a), and the effect of Rp-8-Br-cAMPS in vitro was expressed as fold induction above that of cells that received no in vitro addition. (d) MAIDS mice were implanted with osmotic pumps delivering PBS or meloxicam for 2 weeks as in (a), and the proliferative responses (left panel) and weights of peripheral (left middle) and mesenteric (right middle) lymph nodes and spleens (right panel) were analysed.

We next assessed the effect of COX-2 inhibitor on the lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly that are features of the lymphoproliferative disease induced by retroviral infection, and in an experiment similar to that of Figure 7(a), we treated MAIDS mice with meloxicam for 2 weeks. Again, T-cell function improved, whereas the weights of peripheral and mesenteric lymph nodes decreased, indicating reduced lymphoproliferation (Figure 7d).

DISCUSSION

The MAIDS syndrome includes both a lymphoproliferative component and T-cell anergy. The T-cell anergy severely compromises the immune system, and in the final stages of MAIDS, the animals are prone to opportunistic infections and neoplasms. We have previously shown that the cAMP-PKA type I pathway plays an important role as a negative regulator of T-cell activation under both health and disease conditions [19,20]. The cAMP-PKA type I pathway inhibits proliferative responses and cytokine production in CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells from healthy blood donors. T-cells isolated from mice with MAIDS have increased levels of cAMP, and the T-cell anergy can be reversed by inhibiting PKA type I [18]. Interestingly, T-cells from HIV patients as well as patients with common variable immunodeficiency also have increased levels of cAMP, and the T-cell dysfunction in both these diseases can be reversed by inhibiting PKA type I in a similar manner as observed in MAIDS [21,22,24]. Here, we show that MAIDS involves up-regulation of COX-2 expression in CD11b+ lymphocytes, leading to increased levels of PGE2. Some increase in COX-1 expression is also seen. PGE2 induces cAMP by binding to EP2 and EP4 prostaglandin receptors [25] and inhibits anti-CD3-induced T-cell proliferation in a cAMP- and PKA-dependent manner, which can be blocked by Rp-8-Br-cAMPS [26]. Inhibition of PGE2 production by COX-2-specific inhibitors significantly improves proliferative T-cell responses and ameliorates the lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly.

COX-2 expression is restricted to sites of tissue injury and inflammation and certain tumours [27], and there are normally low or undetectable levels of COX-2 in lymphoid tissues and resting lymphocytes [28]. However, it has been reported that COX-2 is induced in T-cell activation in vitro [29]. This is interesting with respect to MAIDS and HIV. Both MAIDS and HIV involve massive immune activation and subsequent T-cell anergy. In HIV infection, chronic stimulation and the induction of anergy is not restricted to HIV-specific T-cells as the hyporesponsiveness is broadly manifested and encompasses T-cell responses to recall antigens, alloantigens and mitogens [30,31]. Similarly, in MAIDS, the T-cell anergy manifests itself as a profound hyporesponsiveness to mitogenic stimulation. This suggests that an antigen-independent suppressive mechanism may be operating, and our studies suggest that it may involve inhibition of TCR signalling by the cAMP-PKA type I. This pathway may be elicited by immune activation in an indirect manner. It has previously been reported that HIV infection as well as acute cytomegalovirus infection leads to tumour necrosis factor α-induced release of arachidonic acid in monocytes with the subsequent synthesis and secretion of PGE2 suppressing T-cell function [32–34]. However, increased expression of COX-2 has not been reported in lymphocytes in either MAIDS or HIV infection. In the present study, we report increased expression of COX-2 in CD11b+ T- and B-cells in MAIDS. The up-regulation of COX-2 expression in these cells is probably due to the activation status of the cells. CD11b expression is normally restricted to monocytes and macrophages, and is not expressed by resting lymphocytes. However, T-cells do express CD11b after in vitro activation [35,36]. This suggests that COX-2 is induced in a subset of activated T- and B-cells identified by CD11b leading to increased levels of PGE2. The functional significance is evident from the significantly improved T-cell proliferative responses after in vivo treatment with COX-2-specific inhibitors.

Although a state of immune activation may lead to up-regulation of COX-2 expression in lymphocytes in MAIDS, it is not clear how the replication-defective retrovirus induces such a massive T- and B-cell activation. The viral genome encodes a single gag precursor (Pr60gag) protein. Myristylation of Pr60gag is required for membrane anchoring and disease development [37], and it has been reported that the Pr60gag targeted to the plasma membrane translocates c-Abl from the nucleus to the plasma membrane, leading to proliferation of infected B-cells [38]. It has therefore been suggested that MAIDS may develop as paraneoplastic syndrome. However, as mentioned above, both B- and T-cells are required for disease development [2–4], and several cell contact-dependent interactions involved in normal B- and T-cell interactions have been shown to be required as well [9–12]. This may lead to the hypothesis that Pr60gag induces aberrant activation of infected B-cells, which activate T-cells in the vicinity of lymphoid tissues in an antigen non-specific manner, but by applying co-stimulatory pathways and adhesion proteins normally involved in antigen-specific immune responses. This non-specific T-cell activation is then required for further disease development, which may act back on uninfected B-cells, leading to a massive lymphoproliferative disease and hypergammaglobulinaemia. Such a scenario is supported by the reported disconnection between T-cell anergy and the lymphoproliferative component in the CD4 knockout model [15]. However, the immune activation also leads to up-regulation of COX-2 in T- and B-cells in the lymph nodes, leading to increased production and secretion of PGE2. PGE2 suppresses T-cell function and causes anergy to mitogens and specific antigens requiring signal transduction elicited through the TCR.

In conclusion, the results presented in this study provide a mechanism whereby up-regulation of COX-2 leads to increased levels of PGE2 and thereby suppresses T-cell function. PGE2 directly suppresses T-cell function by binding to EP2 receptors [39] through induction of cAMP [19,25]. Thus up-regulation of COX-2 in CD11b+ T- and B-cells may play a key role in the pathogenesis of MAIDS since in vivo treatment with selective COX-2 inhibitors restores the T-cell responsiveness and reverses the T-cell anergy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Fund for Scientific Research (Télévie), the Centre Anticancéreux près l’Université de Liège, the Fredericq Foundation (to S.R. and M.M.), the Norwegian Cancer Society, Programme for Advanced Studies in Medicine, the Norwegian Research Council and the Novo-Nordisk Foundation (to E.M.A. and K.T.) and the European Union (RTD grant no. QLK3-CT-2002-02149 and QLK2-CT-2002-72419).

References

- 1.Aziz D. C., Hanna Z., Jolicoeur P. Severe immunodeficiency disease induced by a defective murine leukaemia virus. Nature (London) 1989;338:505–508. doi: 10.1038/338505a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mosier D. E., Yetter R. A., Morse H. C., III Functional T lymphocytes are required for a murine retrovirus-induced immunodeficiency disease (MAIDS) J. Exp. Med. 1987;165:1737–1742. doi: 10.1084/jem.165.6.1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yetter R. A., Buller R. M., Lee J. S., Elkins K. L., Mosier D. E., Fredrickson T. N., Morse H. C., III CD4+ T cells are required for development of a murine retrovirus-induced immunodeficiency syndrome (MAIDS) J. Exp. Med. 1988;168:623–635. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.2.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cerny A., Hugin A. W., Hardy R. R., Hayakawa K., Zinkernagel R. M., Makino M., Morse H. C., III B cells are required for induction of T cell abnormalities in a murine retrovirus-induced immunodeficiency syndrome. J. Exp. Med. 1990;171:315–320. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.1.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mosier D. E., Yetter R. A., Morse H. C., III Retroviral induction of acute lymphoproliferative disease and profound immunosuppression in adult C57BL/6 mice. J. Exp. Med. 1985;161:766–784. doi: 10.1084/jem.161.4.766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cerny A., Hugin A. W., Holmes K. L., Morse H. C., III CD4+ T cells in murine acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: evidence for an intrinsic defect in the proliferative response to soluble antigen. Eur. J. Immunol. 1990;20:1577–1581. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830200725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klinman D. M., Morse H. C., III Characteristics of B cell proliferation and activation in murine AIDS. J. Immunol. 1989;142:1144–1149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muralidhar G., Koch S., Haas M., Swain S. L. CD4 T cells in murine acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: polyclonal progression to anergy. J. Exp. Med. 1992;175:1589–1599. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.6.1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green K. A., Crassi K. M., Laman J. D., Schoneveld A., Strawbridge R. R., Foy T. M., Noelle R. J., Green W. R. Antibody to the ligand for CD40 (gp39) inhibits murine AIDS-associated splenomegaly, hypergammaglobulinemia, and immunodeficiency in disease-susceptible C57BL/6 mice. J. Virol. 1996;70:2569–2575. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2569-2575.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Leval L., Colombi S., Debrus S., Demoitie M. A., Greimers R., Linsley P., Moutschen M., Boniver J. CD28-B7 costimulatory blockade by CTLA4Ig delays the development of retrovirus-induced murine AIDS. J. Virol. 1998;72:5285–5290. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.5285-5290.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Leval L., Debrus S., Lane P., Boniver J., Moutschen M. Mice transgenic for a soluble form of murine cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 are refractory to murine acquired immune deficiency syndrome development. Immunology. 1999;98:630–638. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00900.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makino M., Yoshimatsu K., Azuma M., Okada Y., Hitoshi Y., Yagita H., Takatsu K., Komuro K. Rapid development of murine AIDS is dependent of signals provided by CD54 and CD11a. J. Immunol. 1995;155:974–981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simard C., Huang M., Jolicoeur P. Murine AIDS is initiated in the lymph nodes draining the site of inoculation, and the infected B cells influence T cells located at distance, in noninfected organs. J. Virol. 1994;68:1903–1912. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1903-1912.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giese N. A., Giese T., Morse H. C., III Murine AIDS is an antigen-driven disease: requirements for major histocompatibility complex class II expression and CD4+ T cells. J. Virol. 1994;68:5819–5824. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5819-5824.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris D. P., Koch S., Mullen L. M., Swain S. L. B cell immunodeficiency fails to develop in CD4-deficient mice infected with BM5: murine AIDS as a multistep disease. J. Immunol. 2001;166:6041–6049. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.10.6041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doyon L., Simard C., Sekaly R. P., Jolicoeur P. Evidence that the murine AIDS defective virus does not encode a superantigen. J. Virol. 1996;70:1–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.1-9.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koch S., Muralidhar G., Swain S. L. Both naive and memory CD4 T cell subsets become anergic during MAIDS and each subset can sustain disease. J. Immunol. 1994;152:5548–5556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rahmouni S., Aandahl E. M., Trebak M., Boniver J., Tasken K., Moutschen M. Increased cAMP levels and protein kinase (PKA) type I activation in CD4+ T cells and B cells contribute to retrovirus-induced immunodeficiency of mice (MAIDS): a useful in vivo model for drug testing. FASEB J. 2001;15:1466–1468. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0813fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aandahl E. M., Moretto W. J., Haslett P. A., Vang T., Bryn T., Tasken K., Nixon D. F. Inhibition of antigen-specific T cell proliferation and cytokine production by protein kinase A type I. J. Immunol. 2002;169:802–808. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.2.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vang T., Torgersen K. M., Sundvold V., Saxena M., Levy F. O., Skalhegg B. S., Hansson V., Mustelin T., Tasken K. Activation of the COOH-terminal Src kinase (Csk) by cAMP-dependent protein kinase inhibits signaling through the T cell receptor. J. Exp. Med. 2001;193:497–507. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.4.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aandahl E. M., Aukrust P., Skalhegg B. S., Muller F., Froland S. S., Hansson V., Tasken K. Protein kinase A type I antagonist restores immune responses of T cells from HIV-infected patients. FASEB J. 1998;12:855–862. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.10.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aandahl E. M., Aukrust P., Muller F., Hansson V., Tasken K., Froland S. S. Additive effects of IL-2 and protein kinase A type I antagonist on function of T cells from HIV-infected patients on HAART. AIDS. 1999;13:F109–F114. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199912030-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warner T. D., Giuliano F., Vojnovic I., Bukasa A., Mitchell J. A., Vane J. R. Nonsteroid drug selectivities for cyclo-oxygenase-1 rather than cyclo-oxygenase-2 are associated with human gastrointestinal toxicity: a full in vitro analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:7563–7568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aukrust P., Aandahl E. M., Skalhegg B. S., Nordoy I., Hansson V., Tasken K., Froland S. S., Muller F. Increased activation of protein kinase A type I contributes to the T cell deficiency in common variable immunodeficiency. J. Immunol. 1999;162:1178–1185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Breyer R. M., Bagdassarian C. K., Myers S. A., Breyer M. D. Prostanoid receptors: subtypes and signaling. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2001;41:661–690. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vang T., Abrahamsen H., Myklebust S., Horejsi V., Tasken K. Combined spatial and enzymatic regulation of Csk by cAMP and protein kinase a inhibits T cell receptor signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:17597–17600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300077200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crofford L. J. COX-1 and COX-2 tissue expression: implications and predictions. J. Rheumatol. 1997;24(Suppl. 49):15–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pablos J. L., Santiago B., Carreira P. E., Galindo M., Gomez-Reino J. J. Cyclooxygenase-1 and -2 are expressed by human T cells. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1999;115:86–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00780.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Gregorio R., Iniguez M. A., Fresno M., Alemany S. Cot kinase induces cyclooxygenase-2 expression in T cells through activation of the nuclear factor of activated T cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:27003–27009. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100885200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roos M. T., Miedema F., Koot M., Tersmette M., Schaasberg W. P., Coutinho R. A., Schellekens P. T. T cell function in vitro is an independent progression marker for AIDS in human immunodeficiency virus-infected asymptomatic subjects. J. Infect. Dis. 1995;171:531–536. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.3.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shearer G. M., Clerici M. Early T-helper cell defects in HIV infection. AIDS. 1991;5:245–253. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199103000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nokta M. A., Pollard R. B. Human immunodeficiency virus replication: modulation by cellular levels of cAMP. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 1992;8:1255–1261. doi: 10.1089/aid.1992.8.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nokta M. A., Hassan M. I., Loesch K. A., Pollard R. B. HIV-induced TNF-alpha regulates arachidonic acid and PGE2 release from HIV-infected mononuclear phagocytes. Virology. 1995;208:590–600. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Foley P., Kazazi F., Biti R., Sorrell T. C., Cunningham A. L. HIV infection of monocytes inhibits the T-lymphocyte proliferative response to recall antigens, via production of eicosanoids. Immunology. 1992;75:391–397. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muto S., Vetvicka V., Ross G. D. CR3 (CD11b/CD18) expressed by cytotoxic T cells and natural killer cells is upregulated in a manner similar to neutrophil CR3 following stimulation with various activating agents. J. Clin. Immunol. 1993;13:175–184. doi: 10.1007/BF00919970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wagner C., Hansch G. M., Stegmaier S., Denefleh B., Hug F., Schoels M. The complement receptor 3, CR3 (CD11b/CD18), on T lymphocytes: activation-dependent up-regulation and regulatory function. Eur. J. Immunol. 2001;31:1173–1180. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200104)31:4<1173::aid-immu1173>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang M., Jolicoeur P. Myristylation of Pr60gag of the murine AIDS-defective virus is required to induce disease and notably for the expansion of its target cells. J. Virol. 1994;68:5648–5655. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5648-5655.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dupraz P., Rebai N., Klein S. J., Beaulieu N., Jolicoeur P. The murine AIDS virus Gag precursor protein binds to the SH3 domain of c-Abl. J. Virol. 1997;71:2615–2620. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.2615-2620.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nataraj C., Thomas D. W., Tilley S. L., Nguyen M. T., Mannon R., Koller B. H., Coffman T. M. Receptors for prostaglandin E(2) that regulate cellular immune responses in the mouse. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;108:1229–1235. doi: 10.1172/JCI13640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]