Abstract

The present study examines the extent and direction of horizontal, backward and forward spillover effects of FDIs on firms' productivity. It also shows how the mediating factors (firm's age, export and import intensity, R&D and advertisement intensity) contribute to the firms' productivity. Further, the study also uncovers the importance of the ownership patterns of the firms that affect the spillovers. It uses a balanced firm-level panel data set from the Indian manufacturing industries over the available period 2003 to 2016 to examine the inter- and intra-industry spillovers of the FDIs. The estimation methods used in this study are the fixed effects approach and the generalised method of moments. The study also applies the Levinsohn-Petrin method to compute firm-level productivity. It finds a significant positive spillover backward effect and confirms the supportive role of the mediating factors in augmenting the spillover channels. However, the results do not support the existence of horizontal and forward FDI spillover effects for the overall manufacturing industries. They suggest that a comprehensive policy package approach be used, thereby underlining the importance of all channels of the FDI spillover effects and their relations to the downstream sector, particularly by keeping the performance of the firms and their external links in perspective.

Keywords: Foreign direct investment, Horizontal and vertical spillovers, Productivity, Joint effects

1. Introduction

Since the early 20th century, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) has been the most prominent method of technology transfer worldwide. Policymakers have long believed that FDI, which is transmitted through Multinational Enterprises (MNEs), brings with it a package that includes job creation, capital accumulation, upgradation of management skills, export promotion, development of technical know-how and diffusion of technology (Lall, 1997 [1]). However, the spillover effect of FDI virtually contributes to firms' productivity growth through the diffusion of knowledge and technology from foreign investors to local firms and workers [2]. The productivity of domestic firms can be enhanced due to the presence of FDI in the same industry, thereby leading to intra-industry spillovers or horizontal spillovers (Carstensen and Farid, 2004 [3]; [4]). Moreover, it is also possible that the presence of FDI can lead to inter-industry spillovers which are known as vertical spillovers, arising from linkages with domestic firms in different industries (Sinani and Klaus, 2004 [5]; [6]). The spillovers arising from upstream suppliers are known as forward spillovers and those arising from customers down the stream are known as backward spillovers [7].

Although there exist a plethora of studies focusing on the spillover effects of FDI, however, the empirical evidences are mixed, overlapping, and inconclusive (Görg and Greenaway, 2004 [8]; Siddharthan and Lal, 2004; Lipsey and Sjöholm, 2005; [[9], [10], [11]]). The studies from the developing countries, such as, Venezuela [12] and Morocco [13] rejected the hypothesis that foreign presence accelerated the productivity growth of domestic firms and claimed that the net impact was quite marginal. Contrary to these works, studies from the manufacturing establishments of Indonesia [14] and Lithuania [15] provide evidence of positive, productive spillovers from FDI.

In India, the situation was not encouraging until the onset of economic reforms of 1991. Inward FDI was essentially recognised as a technology transfer channel, unavailable through licensing agreements and capital imports. But, the economic reforms of 1991 allowed automatic approval of FDI up to 51 % in several selected industries. Gradually, massive FDI inflows took place (on the basis of annual averages, the volumes have even crossed USD 35 billion during the period 2008–2015) in the manufacturing sector to bring forth competition among local players, expansion of technological knowledge base and formation of human capital through foreign contacts (Mondal and Pant, 2014). Given these facts, several studies surveyed the spillover channels that influence the productivity growth of the domestic firms. Studies by Bhattacharya et al. (2008) and Malik [16] conclude that the increasing inflows of FDI to India's domestic manufacturing firms have resulted in productivity spillovers. However, the findings have not been uniform.

Such mixed results suggest that only receiving large volume of FDI inflows does not necessarily imply positive productivity spillover. Therefore, a rigourous and comprehensive empirical exercise is called for as targeted by the present study to examine why only a certain segment of manufacturing industries realise positive productivity spillover even though the entire spectrum of manufacturing industries receive higher doses of FDI inflow? Does that mean the firm- and industry-specific characteristics (Melitz [17]) play any influential mediating role on local firms' professional ties and connections with their foreign counterparts? The mediating factors (MFs) are the key factors that determine the benefits from FDI and are firm-specific capabilities that differentiate one firm from another (Merlevede and Schoors, 2006). Therefore, the main objective of the present study is to analyse the roles of the mediating factors that affect the productivity growth of Indian manufacturing firms, both independently as well as jointly working through the inter-industry and intra-industry spillover channels. Further, the analysis is extended to examine the roles of the mediating factors that determine productivity under different ownership patterns, i.e., domestic-owned firms and foreign-owned firms. By considering a balanced panel data covering 437 manufacturing firms over the period 2003-04 to 2016-17, the current study evaluates the impact of multinational enterprises on the transmission of productivity benefits to domestic firms resulting from the influx of foreign direct investments.

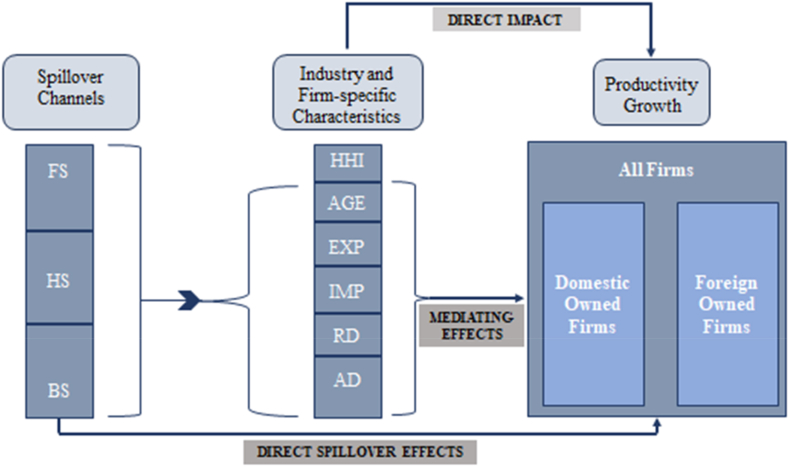

The study uses the fixed effects estimation and the generalised method of moments to estimate the models. It also applies the Levinsohn-Petrin method to generate the firm-level total factor productivity (TFP) measures. The results show that there are positive spillover effects from FDI through the backward linkages. They also reveal that the firms operating under foreign ownership gain more from foreign presence in the downstream sector than those running under domestic ownership. However, the results do not consistently support the existence of horizontal and forward FDI spillover effects. Further, they confirm the supportive roles of the mediating factors in augmenting the spillover channels. The findings underscore the importance of using a comprehensive policy package that keeps the performance of the producing unit (firm) and its external link in perspective. To achieve more gains in the long run, policymakers should emphasise the importance of all the channels that affect the FDI spillover effects, particularly the downstream sector. Please see the figure-1 for conceptual framework of the study.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual framework. Source: Authors own imagination.

This study contributes to the research on the MFs of the FDI spillovers in several ways. Firstly, it considers the heterogeneity of firms’ productivity, and the mediating factors along with the horizontal, forward and backward spillover channels. It also extends the empirical analysis by further splitting the sample into domestically owned and foreign-owned firms in the second part to capture the impact of ownership patterns on productivity. Finally, foreign firms may be biased towards some firms or industries specific unobserved characteristics that may impact productivity of domestic firms. If so, then the empirical exercise may give rise to inconsistent and biased estimates because of endogenity bias. This econometric issue has been handled by using the system GMM.

The presence of foreign MNCs in the same or different sectors of international business and operation through opening up accessories, branches, or subsidiaries massively impacts the elevation of productivity. Such pecuniary benefits or externalities of foreign presence would have been limited if the credit was accounted for by MNCs only. Do the resident firms have no role to play? Indian manufacturing firms have mixed characteristics and show incongruity with each other in various ways. Some are seasoned players, and others are new incumbents in their business operations. Some spend a sizable fraction of their sales on in-house innovation, technological gradation, and diversification of their products through brand imaging, while many others lag. Additionally, firms' internationalization strategies in terms of the volume of foreign technological know-how imports and degree of interaction with foreign markets and consumers through export performance also differ significantly. These firm-specificities contribute directly to their productivity growth and constitute a medium of their absorptive capacity. When these characteristics drop a line with the spillover channels, their overall impact may get accentuated, both on their own and joint. Based on this hypothesis, the present paper aims to explore the roles of the mediating factors that affect the productivity of Indian manufacturing firms, both independently as well as jointly working through the inter-industry and intra-industry spillover channels. This exercise will be different from the earlier studies like Joseph [18], Kathuria [19], Mondal and Pant [20], and Mallik [16] as they concentrate only on one aspect at a time. It will add value to the existing studies as it covers both solo effects of spillover channels and industry-firm-specific characteristics and their mediating effects on firms’ productivity. Furthermore, splitting the overall firms based on ownership will provide additional microscopic evidence of solo and joint effects on the productivity of domestic firms having foreign collaboration and no alliance.

The organizational structure of this paper is as below. A brief outline of the relevant theories and empirics are presented in the section 2. It also highlights the roles of the mediating factors. Section 3 describes empirical framework covering the data, the variable construction and the econometric methodology. Results and main findings from the analysis of productivity spillovers from FDI are discussed in section 4 and finally, section 5 concludes.

2. Review of the literature

The literature review has two parts. The first part discusses existing theories and empirical findings relating to the spillover effects of FDI on the host economy. The roles of mediating factors in affecting the FDI spillovers are critically examined in the second part.

2.1. Spillover effects of FDI on the host economy

The literature has identified three primary channels by which productivity spillovers come into being, such as demonstration effect, labour turnover, and vertical linkages. The demonstration effect is defined as the imitation and reverse engineering of a multinational enterprise's products and practices by local (host country's) firms (Saggi, 2002 [21]). It is also acknowledged that the rate at which foreign firms transfer technology to the host country firms, is directly linked to the former's commitment. This would enhance the probability of the demonstration and competition effects of the FDI spillovers. Several studies empirically established this (e.g., Ref. [15,22,23]). The second channel is the labour turnover or workers' mobility. Workers employed in the firms invested by foreign companies obtain training and acquire skills. Subsequently, they may switch over to join an existing domestic firm or open-up a new one [12,24]. This channel brings forth the foreign knowledge for the benefit of domestic firms.

The third channel refers to the transmission of effects through vertical links. This phenomenon has been studied by Ref. [25,26]. Rodriguez-Clare [27] and Markusen and Venables [28] empirically validate the vertical linkage channel of the FDI spillovers. The forward and backward linkages may re-establish technological spillover via the vertical linkage. The vertical technology transfer through backward linking is a phenomenon that Lin and Saggi [29] take into consideration. Three channels connect multinational firms to local suppliers: direct knowledge transfer from foreign customers to local suppliers, higher product quality and on-time delivery requirements introduced by multinationals, and multinational entry increasing demand for intermediate products, which allows local suppliers to benefit from economies of scale [15].

The absorptive capacity of local enterprises is a significant factor when assessing whether the host nation has positive or negative spillover effects (Blomstrom & Sjoholm, 1999). The technological gap that exists between foreign and domestic firms is another important factor for the FDI spillover [30]. It has been observed that the absorptive capacity will decrease in proportion to the technological gap, and it will become more challenging to acquire resources that are supportive of technological advances. In turn, this results in multinational corporations operating in “enclaves” within the host nation to minimize the costs involved with training the workers for skill augmentation [9]. The heterogeneity of the domestic firms and industries also affects the spillover effects of FDI [31].

Based on the findings of the majority of research, it has been determined that the increase in productivity of manufacturing companies in India is not significantly influenced by the presence of foreign companies (see Refs. [19,[32], [33], [34], [35], [36]] and Marin and Sasidharan[37]. On the other hand, research conducted by Goldar et al. [38], Siddharthan and Lal [39], Behera et al. [40], Sahu and Solarin [41], Mondal and Pant [20], and Mallik [16] has indicated that foreign direct investment has the potential to have beneficial spillover.

In their research on Indian manufacturing companies, Marin and Sasidharan [37] demonstrated that the characteristics of FDI subsidiaries significantly impact the productivity spillovers resulting from FDI. If the subsidiaries are capable of enhancing the host economy's capabilities, then they will have a positive spillover impact on the host country's economy; otherwise, the absorptive capability levels of the local companies are irrelevant. On the other hand, if the companies could not able to use the situation effectively, they would have ended up having a negative spillover impact. Sasidharan and Ramanathan [36] were equally unsuccessful in their attempt to discover horizontal and vertical production spillovers, with the exception of the backward linkage effect. According to their assertions, foreign businesses mostly depended on imported technology rather than native technology sources.

Contrarily, Joseph [18] finds a positive impact for the foreign presence on the productivity of domestic companies. Both the competition effect (horizontal spillovers) and the complementary effect (backward spillovers) have helped spurring domestic firms' productivity growth. In addition, the firms engaged in internal R&D activities have found a cushion that helps reaping the benefits of the positive horizontal and backward FDI spillovers effects. Siddharthan and Lal [39] have argued that the increases in capabilities since the liberalisation have helped the local firms to reap the benefit from the foreign presence in the market. According to Goldar et al. [38] and Behera et al. [40], local enterprises are subject to rivalry from their overseas counterparts, which ultimately results in an increase in the capability and productivity of domestic firms.

2.2. Roles of mediating factors in FDI spillovers

The literature has identified three major types of mediating factors that determine FDI spillovers. These include: characteristics of (i) foreign firms, (ii) domestic firms, and (iii) host-country specific as distinguished from the origin country of MNCs. These characteristics represent the potentiality of MNCs, absorptive capacity of domestic firms and institutional arrangements that affect both, respectively [42].

There are several characteristics of foreign firms that work as mediating factors for technology spillovers. The degree of foreign ownership influences FDI spillovers Dimelis and Louri, 2002 [43]; [11,44,45]. The potential for spillover is likely to be mediated by a variety of factors such as resource-seeking, efficiency-seeking, and market-seeking, which are all driving forces behind foreign direct investment. Additionaly, the products produced by MNCs are technologically advanced in general and FDI spillovers depend on the technology intensity [46,47].

The domestic firms’ characteristics as mediating factors have been examined in several studies ([10,48]; Du et al., 2011 and [12]). For example, the role of the R&D as a mediating factor has been well documented in the literature (Kinoshita, 2001; [[48], [49], [50]]). The shares of skilled labour also mediate [[50], [51], [52]]. The role of exports as the mediating factor has been argued to work in both ways. In contrast to the findings of Blomstrom and Sjoholm [1], Ponomareva [53] and Abraham et al. [54], which indicate that exporters experience lower levels of productivity increases, Barrios and Strobl [48], Lin et al. [47], and Jordan [55] have discovered that exporters experience higher levels of productivity gains. The institutional framework of the host country, which includes regulations on the labor market, access to financial resources, intellectual property rights, learning and innovation, infrastructure, trade, investment, and industrial policy, as well as the governance of the host country, also functions as another set of mediating factors for FDI spillover [11,56].

It is clearly evident from the earlier studies that spillover effects of FDI and the firm's capability have been analysed but separately. Although several studies in the Indian context have examined the nature of the spillover effects on the productivity of the domestic firms, the roles of mediating factors in driving the FDI spillover effects are neglected to a greater extent. Therefore, in this paper, an attempt has been made to examine the nature of the spillover effects on the productivity of the Indian manufacturing firms independently as well as jointly with the mediating factors.

The contributions of the present study is as follows. First, while acknowledging the fact that firms are heterogeneous in terms of their productivity [57], the mediating factors are examined as independent determinants of the firm-level productivity. Although few studies [16,18] have taken a single or few firm-specific characteristics as the mediating factors in the Indian case, our study has concentrated on a set of firm–specific capabilities as the mediating factors. Second, the joint effects of the mediating factors with the horizontal, forward, and backward spillover channels on the firms' level productivity are analysed, which is hardly explored in the Indian scenario. Third, the view that the likelihood of spillover potential varies between the domestic and the foreign ownerships [11], has been empirically verified by further splitting the sample under the categories of domestically owned and FDI firms. Finally, because foreign firms may be attracted towards a specific sector leading to the empirical problem of endogeneity, our study has applied a dynamic panel estimator, i.e. the General Method of Moments (GMM1), to address the potential endogeneity bias.

3. Empirical framework

This paper has employed a two-step estimation procedure to investigate the spillovers effects of FDI. First, the TFP of the firms have been computed using the Levinsohn-Petrin method (2003). Second, the estimated TFP of domestic firms is considered as the dependent variable which is regressed on spillover channels and mediating factors.

3.1. Derivation of total factor productivity measure with the Levinsohn-Petrin framework

As productivity of any producing unit is an unobserved and implicit characteristic, it involves a set of inputs and output for measurement. Additionally, it assumes a theoretical distribution and functional framework that links inputs with output. Econometrically, it may lead to biased and inconsistent estimates, if the estimation techniques do not control for endogeneity issue, simultaneity bias and selection bias. Therefore, the Levinsohn and Petrin approach (2003), a consistent semi-parametric estimator, offers a practical guide for consistently estimating firm productivity. In comparison to the Olley and Pakes approach [58], which is in widespread usage, this method represents an upgrade as it uses the intermediate inputs’ consumption as the proxy for productivity instead of investment.

We assume a Cobb-Douglas2 production function as follows:

| (1) |

The logarithmic transformation of variables like output, capital stock, labor input, raw materials, and firm energy is represented by the letters y, k, l, m, and e, respectively. Here, the letter w represents the productivity of the company, while the letter η represents the measurement error. In the equation (1) presented above, the subscripts i represent the company, j represent the industry, and t represent the period. As a means of compensating for endogeneity bias, we make use of energy as a proxy. These variables are constructed using the data and the variables’ construction section below.

3.2. Horizontal and vertical spillovers and mediating factors

In the second stage, domestic firms' total factor productivity (TFP) is regressed on the three versions of spillover channels, industry characteristics, and a set of firm-specific characteristics that play the mediating role. This is demonstrated by the regression equation that is provided below.

| TFPijt = β1HSjt + β2BSjt+ β3FSjt+ β4HHIjt + β5AGEijt + β6EXPINTijt + β7IMPINTijt + β8RDINTijt + β9ADINTijt + εijt | (2) |

In Eq. (2), HS, BS, FS, HHI, AGE, EXPINT, IMPINT, RDINT and ADINT respectively denote the horizontal FDI spillovers, backward FDI spillovers, forward FDI spillovers, Herfindahl-Hirschman Index, age, export intensity, technology import intensity, R&D intensity and advertisement intensity. The term ε is the error term. The details about these variables are mentioned in the data and variable construction section.

The study categorizes all the companies into two categories: domestic companies and foreign firms. This is done since the study's main objective is to investigate how the presence of foreign ownership in Indian manufacturing enterprises influences the diffusion of knowledge to the host nation. The firms with at least 10 % foreign equity participation or more are categorized as foreign-owned firms, and the domestic firms own less than 10 % or none. Moreover, the interaction effects of firm-specific characteristics with three spillover effect covariates are done separately and are presented in the following regression equations:

| TFPijt = β1HSjt + β2BSjt + β3FSjt + β4HHIjt + β5HS*AGEijt + β6HS*EXPINTijt + β7HS*IMPINTijt + β8HS*RDINTijt + β9HS*ADINTijt + εijt | (3) |

| TFPijt = β1HSjt + β2BSjt + β3FSjt + β4HHIjt + β5BS*AGEijt + β6BS*EXPINTijt + β7BS*IMPINTijt + β8BS*RDINTijt + β9BS*ADINTijt + εijt | (4) |

| TFPijt = β1HSjt + β2BSjt + β3FSjt + β4HHIjt + β5FS*AGEijt + β6FS*EXPINTijt + β7FS*IMPINTijt + β8FS*RDINTijt + β9FS*ADINTijt + εijt | (5) |

In this study, we apply the firm-level fixed effects estimation (FEE)3 in the static panel analysis and the System Generalised Method of Moments (SGMM)4 in the dynamic panel analyses to estimate the models given in Eq. (2) to Eq. (5). The FEE is preferred in this study over random effect estimation as the Hausman test supports the former model. Nevertheless, the fixed effects specification is susceptible to heteroscedasticity and serial correlation, which might result in skewed estimates of the model. The SGMM estimation technique addresses the unobserved heterogeneity and endogeneity problems. It also allows the total factor productivity to depend on its own past realisations.

3.3. Data and variables

The detailed database along with the details of the used variables is represented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of variables and data sources.

| Variables | Description | Formula for computation | Data sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Factor Productivity and its related Variables | |||

| TFP | Total Factor Productivity | Levinsohn-Petrin Method | Authors' computation |

| Y | Real Output | (Sales + change in stock of finished/semi-finished goods of the firm) divided by industry level price indices | CMIE, Prowess |

| L | Labour or number of persons engaged in a firm. | Salaries and wages at the firm level divided by the average wage rate (AWR) of the industry (two-digit) to which the firm belongs. To arrive at the AWR, the Annual Survey of Industries (ASI) provides data on the Total Emoluments (TE) as well as the Total Persons Engaged (TPE) for the relevant industry (AWR = TE/TPE). | CMIE, Prowess and ASI |

| K | Capital | Gross fixed assets (GFA) of the firm in the historical cost and application of the Perpetual Inventory Method | CMIE, Prowess and National Accounts Statistics (CSO) |

| M | Raw Materials | Reported cost of raw materials deflated by the raw material price indices for each industry | CMIE, Prowess and Input-Output Transaction Table of India (CSO) |

| E | Energy | Reported energy cost deflated by an energy price index | Same as above |

| Spillover Channels related variables | |||

| HS | Horizontal FDI Spillover measures the share of output accounted for by the foreign firms in the total output of the industry | Horizontal FDIjt = where Yit is the output of firms i in year t and Yitf is output of foreign firm i in the same year. n stands for the total number of firms in an industry consisting of both domestic and foreign firms and m denotes the number of foreign firms in an industry. | Same as above |

| BS | Backward FDI Spillover is the share of total output of an industry that is sold to foreign firms in downstream industries. | Backward FDIjt = Horizontal FDIkt where is the proportion of industry j's output supplied to industry k, which is taken from the 2006–2007 industry x industry coefficient matrix at the two-digit level (NIC-2008). (For more details, see Ref. [14]) | Same as above |

| FS | Forward FDI spillover measures the degree of forward linkages from foreign firms to domestic firms in the downstream industries and is defined as the proportion of an industry's intermediate consumption supplied by the foreign-owned firms. | Forward FDIjt = where σwj is the share of inputs purchased by industry j from industry w in the total inputs sourced by industry j and the superscript f stands for the foreign firm. The second term of the right side of the equation computes the share of foreign firms' output in the upstream or the supplying industry. For the same reason as before, inputs purchased within the sector are excluded. The value of the variable increases with an increase in the share of foreign firms' output in the upstream industries. | Same as above |

| Market Structure or Degree of Competition | |||

| HHI | Herfindahl-Hirschman Index captures the effect of competition in an industry | where si is the market share of firm i in the market and N is the number of firms. | Same as above |

| Mediating Factors | |||

| EXPINT | Export Intensity measures the degree of interaction with foreign buyers and foreign markets | Ratio of the firm's export to its sales value | CMIE, Prowess |

| IMPINT | Technology import intensity controls for the expenditure on technology imports | Ratio of a firm's expenditure on technology import to its sales value. The technology import expenditure includes the expenditure on the import of capital goods and foreign exchange spending on royalty and/or technical know-how | Same as above |

| RDINT | Research and Development (R&D) intensity measures the in-house technology content and its potentiality | Ratio of firm's R&D expenditure to its sales value. | Same as above |

| ADINT | Advertisement Intensity measures the degree of product differentiation by creating positive brand images | Ratio of firm's advertisement expenditure to its sales value | Same as above |

| AGE | Age of the firm measures production and business experience and understanding of the market | Current year minus the incorporation year of the firm. | Same as above |

This study is based on the firm-level panel data of the 19 manufacturing industries chosen from the National Industrial Classification, 2008 (NIC-2008), from 2003 to 2004 and from 2016 to 2017. After initial rounds of data filtration, we are left with 6118 observations on 437 manufacturing firms for 14 years. The descriptive statistics for the sample used are presented in Table 2. They summarise significant correlations between the productivity of firms and the spillover channels. Moreover, the inclusion of the mediating factors along with the channels of spillovers in the estimation is free from the multicollinearity problem as the mean VIF is very small.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

| Pair-wise Correlation coefficients |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | VIF | LTFP | HS | BS | FS | HHI | AGE | EXPINT | IMPINT | RDINT | ADINT |

| LTFP | 0.845 | 0.901 | −6.582 | 3.354 | 1 | ||||||||||

| HS | 0.275 | 0.156 | 0.018 | 0.717 | 1.26 | −0.120*** | 1 | ||||||||

| BS | 0.109 | 0.136 | 0.002 | 0.508 | 1.37 | 0.191*** | −0.074*** | 1 | |||||||

| FS | 0.067 | 0.044 | 0.011 | 0.16 | 1.55 | −0.165*** | 0.426*** | −0.438*** | 1 | ||||||

| HHI | 0.071 | 0.065 | 0.027 | 0.581 | 1.1 | −0.109*** | 0.063*** | −0.256*** | 0.060*** | 1 | |||||

| AGE | 26.955 | 16.593 | 0 | 112 | 1.02 | 0.187*** | 0.007 | −0.017 | 0.015 | −0.094*** | 1 | ||||

| EXPINT | 17.848 | 27.113 | 0 | 374.9 | 1.03 | 0.040*** | 0.061*** | −0.078*** | 0.040** | 0.067*** | −0.096*** | 1 | |||

| IMPINT | 0.018 | 0.526 | 0 | 41 | 1.00 | −0.107*** | 0.001 | −0.015 | 0.005 | 0.000 | −0.008 | −0.002 | 1 | ||

| RDINT | 0.002 | 0.008 | 0 | 0.203 | 1.01 | −0.030** | 0.054*** | −0.012 | 0.008 | −0.026** | 0.035*** | 0.014 | −0.002 | 1 | |

| ADINT | 0.004 | 0.016 | 0 | 0.514 | 1.02 | 0.025* | 0.020 | −0.084 | 0.016*** | 0.088*** | 0.010 | −0.069*** | −0.003 | −0.009 | 1 |

| Observation | 6118 | 1.15 (Mean VIF) | |||||||||||||

Note: ***, ** and * denote significance at the 1 per cent, 5 per cent and 10 per cent levels, respectively.

Source: Authors' calculation.

4. Results and discussion

The average performance of different manufacturing sectors is shown in Table 3.5 It can be observed that the productivity of the manufactured leather and related products (NIC # 15) is on average the lowest among all the manufacturing industries, whereas the manufacturer of basic metals (# 24) leads the series. In the horizontal FDI categories, the manufacturers of computer, electronic and optical products (# 26) dominate the firms operating under paper products. In the vertical FDI category, the manufacturer of beverages (#11) and the manufacturer of wood products (# 16) lie in the lowest ladder of the backward and forward FDIs. The manufacturer of basic metals (# 24) and other manufacturers lead in terms of the highest backward and forward FDIs, respectively.

Table 3.

Average Performance of Manufacturing Sub-sectorsa w.r.t. TFP, HS, BS and FS.

| NIC_Sectors | TFP_Average | NIC_Sectors | HS_Average | NIC_Sectors | BS_Average | NIC_Sectors | FS_Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 0.322 | 17 | 0.022 | 11 | 0.002 | 16 | 0.012 |

| 11 | 0.383 | 11 | 0.059 | 15 | 0.006 | 10 | 0.012 |

| 33 | 0.396 | 23 | 0.060 | 21 | 0.006 | 24 | 0.017 |

| 32 | 0.480 | 10 | 0.092 | 14 | 0.010 | 23 | 0.021 |

| 28 | 0.495 | 14 | 0.128 | 30 | 0.015 | 20 | 0.021 |

| 23 | 0.597 | 30 | 0.194 | 16 | 0.020 | 15 | 0.024 |

| 16 | 0.623 | 25 | 0.196 | 23 | 0.022 | 13 | 0.033 |

| 21 | 0.634 | 24 | 0.197 | 17 | 0.025 | 17 | 0.039 |

| 22 | 0.729 | 21 | 0.206 | 33 | 0.026 | 11 | 0.058 |

| 26 | 0.765 | 13 | 0.250 | 28 | 0.034 | 32 | 0.065 |

| 14 | 0.798 | 22 | 0.267 | 10 | 0.035 | 21 | 0.066 |

| 27 | 0.832 | 20 | 0.284 | 13 | 0.047 | 30 | 0.096 |

| 17 | 0.845 | 33 | 0.354 | 26 | 0.048 | 26 | 0.100 |

| 13 | 0.876 | 16 | 0.356 | 32 | 0.050 | 25 | 0.106 |

| 20 | 0.978 | 27 | 0.357 | 22 | 0.063 | 27 | 0.111 |

| 25 | 0.987 | 15 | 0.572 | 25 | 0.099 | 14 | 0.111 |

| 10 | 0.999 | 28 | 0.580 | 27 | 0.227 | 22 | 0.114 |

| 30 | 1.103 | 32 | 0.608 | 20 | 0.241 | 28 | 0.114 |

| 24 | 1.359 | 26 | 0.630 | 24 | 0.472 | 33 | 0.149 |

Note: The figures are arranged in an ascending order of performance. Here NIC stands for the National Industries Classification (2008), TFP for total factor productivity, HS for horizontal spillover, BS for backward spillover and FS for forward spillover effects, respectively.

Note: The following two-digit codes represent the respective industries: 10 - Manufacturer of food products; 11 - Manufacturer of beverages; 12 - Manufacturer of tobacco products; 13 - Manufacturer of textiles; 14 - Manufacturer of wearing apparel; 15 - Manufacture of leather and related products; 16 - Manufacturer of wood and products of wood and cork, except furniture; manufacturer of articles of straw and plaiting materials; 17 - Manufacturer of paper and paper products; 18 - Printing and reproduction of recorded media; 19 - Manufacturer of coke and refined petroleum products; 20 - Manufacturer of chemicals and chemical products; 21 - Manufacturer of pharmaceuticals, medicinal chemical and botanical products; 22 - Manufacturer of rubber and plastics products; 23 - Manufacturer of other non-metallic mineral products; 24 - Manufacturer of basic metals; 25 - Manufacturer of fabricated metal products, except machinery and equipment; 26 - Manufacturer of computers, electronic and optical products; 27 - Manufacturer of electrical equipment; 28 - Manufacturer of machinery and equipment n. e.c.; 29 - Manufacturer of motor vehicles, trailers and semi-trailers; 30 - Manufacturer of other transport equipment; 31 - Manufacturer of furniture; 32 - Other manufacturers; 33 - Repair and installation of machinery and equipment. In our study # 12, 18, 19 and 29 are not considered for insufficiency of data.

Source: Authors' calculation.

The study examines the vertical and horizontal spillovers from FDI in the regression equation (2), with the application of both static and dynamic panel data analyses. The spillover covariates and firm-specific characteristics are estimated but without interaction effects. However, in the models given in Eq. (3) to Eq. (5), the interaction effects are estimated along with the spillover effects. The interaction effects of the horizontal spillover effects with the mediating factors are estimated in Eq. (3).

Further, the interaction effects of the backward spillover effects with the mediating factors are modelled in Eq. (4). Finally, the interaction effects of the forward spillover effects with the mediating factors are estimated as given in Eq. (5). The model's productivity spillovers from domestically owned firms are compared with those of foreign-owned firms. Also, a comparison is made with the overall firms where no distinction is made on the basis of the ownership patterns.

4.1. Horizontal and vertical technology spillovers from FDI

Table 4 presents the results of FEE and SGMM econometrics techniques for the full sample of the manufacturing firms. The estimates of the horizontal FDI are positive and statistically significant in the fixed effects estimation but are found to be statistically insignificant in the system GMM estimation.

Table 4.

Estimates of mediating factors and productivity spillover channels without interaction effects.

| Depvar: ltfpijt | Fixed Effect Estimation | System GMM Estimation |

|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | All firms (I) | All firms (II) |

| ltfpijt-1 | 0.641*** (0.095) | |

| Horizontal Spillover | 1.293*** | 0.262 |

| (0.371) | (0.261) | |

| Backward Spillover | 1.616* | 2.841*** |

| (0.908) | (0.662) | |

| Forward Spillover | −1.025 | −0.883 |

| (2.472) | (1.46) | |

| HHI | −1.669 | 0.136 |

| (1.131) | (0.717) | |

| Age | 0.055*** | 0.024*** |

| (0.003) | (0.007) | |

| Export intensity | 0.002** | 0.002* |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Import intensity | −0.168*** | −0.151*** |

| (0.001) | (0.033) | |

| R&D intensity | −2.097* | −2.514** |

| (1.096) | (1.086) | |

| Advertisement intensity | 0.018 | −1.021 |

| (2.494) | (1.917) | |

| Constant | −0.999*** | |

| (0.273) | ||

| Time fixed Effect | Yes | |

| Observations | 6118 | 5244 |

| Number of firms | 437 | 437 |

| Within R-squared | 0.3599 | |

| F-statistic | 2581.62*** | 253.49*** |

| Hausman test (chi-square) | 723.86*** | |

| Hansen (p-value) | 0.188 | |

| AR(2) (p-value) | 0.055 |

Note: (1) Robust standard errors are provided in the parentheses. (2) *, **, and *** represent significance at the 10 per cent, 5 per cent, and 1 per cent levels, respectively.

As a result of a one-unit rise in the output of foreign businesses operating in the same industries, the total factor productivity (TFP) of the overall manufacturing firms is predicted to improve by around 129 percent, according to the substantial estimated coefficient presented here. In light of this, it can be deduced that the presence of foreign companies in the industries that supply the domestic firms and in the same industries is beneficial to the domestic enterprises because of the horizontal connections. However, such a conclusion cannot be generalised as the dynamic panel estimation does not support it. Furthermore, the calculated coefficients of the backward foreign direct investment (FDI) spillover in both the FEE and system GMM models are positive and shown to be statistically significant. This suggests that if there is a rise in output by a single unit of a foreign firm operating in the downstream sector, then the TFP of the manufacturing firms increases by 161 % (FEE) and 284 % (system GMM). This implies that as the foreign presence become prominentin the downstream industries, it boosts productivity performance of the domestic firms through the backward linkage. In contrast, foreign presence in the raw materials supplying industries and operating in the upstream sector do not have any significant spillover effect on the productivity growth of the domestic firms, as the coefficients of Forward FDI spillover effects are statistically insignificant in both estimations.

All the mediating factors and firm-specific variables, except HHI and advertisement intensity, have mixed but significant effects on the overall manufacturing firms in India. There is a favourable and statistically significant influence that age and export intensity have on the private companies that are based in India. This indicates that more experienced firms may have accumulated valuable production and business experiences over a period of time that this gives them an advantage that hence improves their TFP. Similarly, a greater degree of internationalization in terms of export intensity leads to a higher productivity. However, the estimated coefficients of technology import intensity and R&D intensity are negative and statistically significant. This implies that larger the share of sales of domestic firms spent on capital imports and foreign payments towards royalty and technical information in the technology from abroad, the less will be its productivity growth prospect. However, negative R&D intensity is an exception in contrast to the conventional presumption that the degree of innovation as captured by R&D intensity contributes positively to the firms’ productivity performance. A number of other researchers, including Schoors van der Tol (2002) and Javorcik [15] have come to a similar conclusion. The backward links have been used to verify the vertical technological spillovers that result from foreign direct investment.

4.2. Ownership differences and productivity spillovers from FDI

Columns (iii) and Column (iv) of Table 5 show the fixed effects estimation of model 1, thereby splitting the overall sample into domestic firms6 and foreign firms,7 respectively. Employing the system GMM estimation, the results are reported in Columns (v) and (vi) of Table 5, respectively. As per FEE, the estimated coefficient of the horizontal FDI for the foreign-owned firms is 3.85 and is statistically significant at the 1 % level. In the system GMM estimation, FDI via the horizontal linkage for the foreign-owned firm is 2.62 and statistically significant at the 1 % level. But, the coefficient is not uniform for the domestically owned firms, neither in significance nor even in the sign. Therefore, it can be concluded on the basis of the above findings that as the foreign presence in the foreign-owned firms increases, it will contribute more to horizontal FDI spillover effects.

Table 5.

Estimates of mediating factors and productivity spillover channels without interaction effects.

| Depvar: ltfpijt | Fixed Effect Estimation | System GMM Estimation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | Domestic firms (iii) | Foreign firms (iv) | Domestic firms (v) | Foreign firms (vi) |

| ltfpijt-1 | 0.718*** | 0.643*** | ||

| (0.037) | (0.121) | |||

| Horizontal Spillover | 0.258 | 3.849*** | −0.899*** | 2.617*** |

| (0.433) | (0.607) | (0.266) | (0.466) | |

| Backward Spillover | 1.787* | 0.475 | 3.326*** | 3.383** |

| (1.024) | (1.942) | (0.768) | (1.615) | |

| Forward Spillover | −0.34 | −1.747 | −0.044 | −0.766 |

| (2.999) | (4.056) | (1.379) | (2.955) | |

| HHI | −2.212* | −2.188 | −0.102 | −1.113 |

| (1.291) | (1.748) | (0.719) | (1.424) | |

| Age | 0.053*** | 0.06*** | 0.018*** | 0.023** |

| (0.004) | (0.006) | (0.003) | (0.01) | |

| Export intensity | 0.003** | 0.001 | 0.003* | 0.001 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Import intensity | −0.167*** | −0.364** | −0.171*** | 0.664 |

| (0.001) | (0.17) | (0.024) | (1.062) | |

| R&D intensity | −1.416 | −2.054 | −1.372 | 6.739 |

| (1.326) | (1.808) | (1.322) | (7.798) | |

| Advertisement intensity | −0.675 | 0.328 | −1.847 | −0.23 |

| (5.369) | (0.479) | (2.647) | (1.641) | |

| Constant | −0.733** | −1.703*** | ||

| (0.304) | (0.556) | |||

| Time fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | ||

| Observations | 4620 | 1498 | 3960 | 1284 |

| Number of firms | 330 | 107 | 330 | 107 |

| Within R-squared | 0.3524 | 0.4448 | ||

| F-statistic | 3908.37*** | 12.47*** | 274.44*** | 95.31*** |

| Hausman test (chi-square) | 606.32*** | 137.32*** | ||

| Hansen (p-value) | 0.291 | 0.53 | ||

| AR(2) (p-value) | 0.121 | 0.376 | ||

Note: (1) Robust standard errors are in the parentheses. (2) *, **, and *** show significance at the 10 per cent, 5 per cent, and 1 per cent levels, respectively.

The estimated coefficients of backward FDI spillover effects are positive and significant, irrespective of the estimation procedure and the ownership structure (with the exception of foreign-owned firms in FEE). This indicates that the presence of FDI firms in the downstream industries benefits domestically owned as well as foreign-owned firms through the backward linkages. However, foreign-owned firms receive more positive backward spillover effects than domestically-owned firms (as per the results of the system GMM estimation technique only).

The forward spillover effects are statistically insignificant (in both the FEE and system GMM estimations) for the domestic and foreign-owned firms. All the mediating factors, including HHI, maintain similar effects even when the sample is divided on the basis of the ownership pattern. The estimated coefficients remain either insignificant or, if found to be significant, maintain the same sign as that of the overall firms. That means the variation in the ownership structure does not impact much on the effects of the mediating factors on productivity of the firms. However, the immediate lag period of TFP is estimated as an independent variable in the system GMM estimation. The estimated coefficients for the overall firms (see Table 4), domestic firms and foreign-owned firms (see Table 5) are all positive and statistically significant. It confirms the behaviour of historical growth of TFP. The findings of the study are similar to Sugiharti, L et al. [59] and Sun, Y., Zhang et al. [60]. Other diagnostic tests such as the within R-square, F-statistics and Hausman chi-square tests, all endorse the model's reliability. The Hansen test and autocorrelation test (AR (2)) also confirm the validity of the instruments used to handle the endogeneity problem.

4.3. Mediating factors and productivity spillovers from FDI

The results as shown in Table 6 describes the interactions between the mediating factors and the spillover channels and results are reported for all manufacturing firms, domestic-owned and foreign-owned firms. Models (i), (iv) and (vii) show the impact of mediating factors on the firms’ productive capacity from the interactions of HS, BS and FS for the overall manufacturing firms. In Table 6, Columns (ii), (v), and (viii) provide the outcomes of an exercise that was conducted in a similar fashion for the firms that are controlled by domestic entities. Similarly, models (iii), (vi) and (ix) of the same table present the interaction effects of the mediating factors and the spillover channels of HS, BS and FS.

Table 6.

Mediating Factors and FDI Spillover effect: System GMM Estimation.

| Depvar: ltfpijt |

Interaction with HS |

Interaction with BS |

Interaction with FS |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | All firms (i) | Domestic firms (ii) | Foreign firms (iii) | All firms (iv) | Domestic firms (v) | Foreign firms (vi) | All firms (vii) | Domestic firms (viii) | Foreign firms (ix) |

| ltfpijt-1 | 0.621*** | 0.689*** | 0.771*** | 0.759*** | 0.818*** | 0.682*** | 0.595*** | 0.691*** | 0.680*** |

| (0.102) | (0.040) | (0.089) | (0.074) | (0.029) | (0.099) | (0.108) | (0.041) | (0.131) | |

| Horizontal FDI (HS) | −2.405*** | −3.366*** | 1.149 | 0.131 | −0.987*** | 2.573*** | 0.067 | −0.993*** | 2.567*** |

| (0.754) | (0.495) | (0.788) | (0.259) | (0.293) | (0.422) | (0.252) | (0.270) | (0.478) | |

| Backward FDI (BS) | 2.524*** | 2.917*** | 3.496** | 0.227 | 1.125 | −2.236 | 2.179*** | 2.620*** | 3.330** |

| (0.684) | (0.743) | (1.562) | (1.156) | (0.908) | (2.663) | (0.728) | (0.740) | (1.671) | |

| Forward FDI (FS) | −0.184 | 0.293 | −1.755 | −3.828*** | −1.994 | −2.632 | −9.929*** | −8.084*** | −9.083** |

| (1.625) | (1.347) | (3.129) | (1.381) | (1.445) | (2.867) | (2.256) | (1.525) | (4.168) | |

| HHI | 0.738 | −0.081 | −0.583 | −0.341 | −0.342 | −1.269 | 0.531 | 0.013 | −1.122 |

| (0.819) | (0.709) | (1.405) | (0.726) | (0.742) | (1.401) | (0.732) | (0.708) | (1.467) | |

| HS*AGE | 0.092*** | 0.077*** | 0.047** | ||||||

| (0.026) | (0.012) | (0.023) | |||||||

| HS*EXPINT | 0.005* | 0.011** | 0.005 | ||||||

| (0.003) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |||||||

| HS*IMPINT | −0.704*** | −0.783*** | −0.596 | ||||||

| (0.162) | (0.134) | (2.643) | |||||||

| HS*RDINT | −8.255* | −7.644** | −10.605 | ||||||

| (4.499) | (3.989) | (27.050) | |||||||

| HS*ADINT | −6.531 | −9.945 | −4.699 | ||||||

| (7.613) | (11.431) | (5.038) | |||||||

| BS*AGE | 0.118*** | 0.101*** | 0.196*** | ||||||

| (0.041) | (0.022) | (0.077) | |||||||

| BS*EXPINT | 0.012* | 0.026** | 0.017 | ||||||

| (0.007) | (0.011) | (0.022) | |||||||

| BS*IMPINT | −9.192 | −18.186** | 9.820 | ||||||

| (9.173) | (8.092) | (8.289) | |||||||

| BS*RDINT | −9.654 | −20.958 | −40.663 | ||||||

| (22.877) | (26.333) | (29.106) | |||||||

| BS*ADINT | 5.610 | 0.813 | 35.578 | ||||||

| (19.737) | (69.811) | (31.318) | |||||||

| FS*AGE | 0.396*** | 0.285*** | 0.264* | ||||||

| (0.117) | (0.048) | (0.153) | |||||||

| FS*EXPINT | 0.029 | 0.068*** | 0.009 | ||||||

| (0.019) | (0.023) | (0.015) | |||||||

| FS*IMPINT | −2.263*** | −2.682*** | 14.616 | ||||||

| (0.569) | (0.425) | (15.451) | |||||||

| FS*RDINT | −46.251** | −38.992* | 183.206 | ||||||

| (21.436) | (21.799) | (165.635) | |||||||

| FS*ADINT | −29.100 | −44.911 | 11.214 | ||||||

| (30.014) | (33.578) | (27.481) | |||||||

| Constant | |||||||||

| Observations | 5244 | 3960 | 1284 | 5244 | 3960 | 1284 | 5244 | 3960 | 1284 |

| Number of firms | 437 | 330 | 107 | 437 | 330 | 107 | 437 | 330 | 107 |

| F-statistic | 188.87 | 188.45 | 105.01 | 236.55 | 246.18 | 58.85 | 180.25 | 226.42 | 67.39 |

| Hansen (p-value) | 0.174 | 0.252 | 0.221 | 0.164 | 0.239 | 0.18 | 0.196 | 0.291 | 0.546 |

| AR(2) (p-value) | 0.064 | 0.125 | 0.389 | 0.304 | 0.143 | 0.424 | 0.069 | 0.124 | 0.291 |

Notes: Robust standard errors are given in the parentheses and *, **, and *** show significance at the 10 per cent, 5 per cent, and 1 per cent levels, respectively. Here HS stands for horizontal spillover, BS for backward spillover and FS for forward spillover effects respectively.

Source: Authors' calculation.

The results of Table 6 show that the interaction effects of age and the spillover channels on the productivity of the overall Indian manufacturing industry are positive and significant at the 1 per cent level. The coefficients of HS*AGE (0.092), BS*AGE (0.118) and FS*AGE (0.396) indicate that as the firm becomes more and more experienced, it could contribute more positively to the intra- and inter-industry spillover effects regarding the productivity of the overall manufacturing firms. More importantly, the forward spillover effect on the productivity is more pronounced in comparison to the backward spillover effect and horizontal spillover effect. The findings are similar when the estimated coefficients are analysed for sub-sample firms, i.e. domestically-owned firms and FDI firms.

Moving to the second mediating factor EXPINT, the results show that the estimated coefficients of its interaction with the HS (0.005) and BS (0.012) channels are found to be positive but weakly statistically significant (at the 10 % level) for the overall manufacturing firms. Moreover, the coefficient for FS*EXPINT (0.029) loses the significance level. This shows that as the firm becomes more internationalized, the more will the possibilities be for the horizontal and backward spillover effects of FDI on the productivity of the firms. However, the coefficients of HS*EXPINT (0.011), BS*EXPINT (0.026) and FS*EXPINT (0.068) for domestically owned firms indicate that a higher proportion of sales going for export would result in positive HS, BS and FS effects on the productivity. A comparative study demonstrates, once more, that the forward spillover impact on the productivity of domestically held enterprises is more substantial than the backward and horizontal spillover effects. This is the cases compared to the other two types of spillover effects. On the contrary, the estimated coefficients for the interaction effects of EXPINT with the three channels of productivity spillover lose statistical significance, making it difficult to draw any conclusions on the significant effect of EXPINT as a mediating factor for the productivity spillover effects of FDI, especially when the firms are running under the control of foreign ownership.

In contrast to the hypothesis related to the technological upgradation through innovation and R&D, this paper finds that a higher level of R&D generated from greater sales of a firm would hinder productivity through the horizontal (−8.26) and forward (−46.25) spillover channels. Those findings are similar for those of the domestically owned firms. One important point to note from Table 6 is that the estimated coefficients of HS*RDINT, BS*RDINT and FS*RDINT for the foreign owned firms are also negative but insignificant. The negative and significant coefficients for both the overall and domestically owned enterprises indicate that the advantage of the foreign presence in the same industry and those operating in the upstream sector in terms of productivity is lower when the R&D intensity is higher. This is the case regardless of whether the firms are of domestic or foreign ownership.

The results of the interaction effects of IMPINT with the spillover channels on the productivity performance of the overall firms and the domestic owned firms are almost similar to the interaction effects of RDINT with the HS, BS and FS channels. The estimated coefficients for HS*IMPINT, BS*IMPINT and FS*IMPINT are negative for the domestically owned firms and the overall firms but the results for the foreign-owned firms lack statistical significance. This result suggests that if a higher proportion of sales of a firm goes to expenditures on the capital imports and technological licensing fees payments, then the negative productivity spillover effects through the different channels become more pronounced. It may be so because firms have to pay a higher price or a greater interest for either purchasing or leasing advanced technologies that contribute to expanding their productive capacity. However, higher expenditures on technology imports may result in a sizable fraction of total sales going to foreign countries as an import flow or as a repayment, which may negatively contribute to the productivity of firms. This finding is similar with Wang, H., Zheng et. al [61].

ADINT and its interaction effects with the HS, BS and FS channels on the productivity of manufacturing firms show no statistically significant result. However, ADINT generally captures the intangible assets along with RDINT that may control an upward bias in the performance measures of the firms. Moreover, ADINT may help firms in building their reputation and acting as a deterrent for new entrants in the industry [62]. Columns (i)-(ix) endorse the historical growth pattern of TFP, i.e.; the past values of the TFP affect its current value too. The other diagnostic tests (Hansen and AR (2)) also confirm the validity of the instruments used to handle the endogeneity problem. The reported standard errors are robust with respect to econometric problems like heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation.

The interaction effect results shown in Table 6 reveal that the coefficients of the original HS, BS and FS channels change their signs and statistical significance in the presence of mediating factors. Alternatively, this substantiates the notion that the spillover channels, through the mediation of the variables, have an impact on the productivity of manufacturing firms in India. In a study by Nam, H. J., Bang, J., & Ryu, D [63]. also reported a similar finding.

5. Conclusion

This study examines the impact of FDI spillovers on the productivity of Indian manufacturing firms during the period 2003-04 to 2016-17. It also focuses on three different forms of the FDI-induced spillover channels, namely the horizontal, backward and forward spillovers. In the empirical analysis, we use firm-specific mediating factors that include age of firms, export intensity, technology import intensity, R&D intensity and advertisement intensity. In addition to the earlier studies, the present study has examined the mediating factors along with their interaction effects with the spillover channels on the productivity of the firms. The robustness of this exercise is further enhanced as the overall firms are classified into FD|I and domestically owned firms, respectively.

In this two-stage econometrics exercise, we apply the semi-parametric estimation method of Levinsohn and Petrin [64] to measure the productivity of the Indian manufacturing firms. In the following stages of the estimation process, the fixed effects panel regression in the static approach and the system GMM estimation in the dynamic panel regression are used. Taking total factor productivity of the firms as dependent variable, we use key sectoral and firm-specific mediating variables as the independent variables, along with three spillover channels: horizontal, backward and forward. The selection of variables is in accordance with the existing literature, including there are primary factors that determine the rise of productivity at the firm level.

Departing from earlier studies, the present paper adds to the available literatures related to productivity spillovers by the following ways. It explains how the intra- and inter-industry spillovers from FDI vary across sectors and over time, by considering the recent available data. Furthermore, the study also unravels how the firm-specific mediating factors mediate the productivity spillovers from FDI to Indian manufacturing industries. Moreover, the study also uncovers the importance of the ownership patterns of the firms in affecting productivity spillovers from FDI.

In concordance with the empirical evidence from the earlier studies [14,15,16], the paper confirms that there exist positive FDI spillover effects from FDI via the backward linkages. Besides, it is also revealed that firms operating under foreign ownership gain more from the presence of foreign firms in the downstream sector than those running under domestic ownership. This asserts that productivity spillovers are more pronounced for foreign ownership affiliates than domestic-owned firms. This may be so because foreign firms are professionals in terms of quality assurance and punctual delivery. However, the horizontal spillover results are not uniform. But in general, firms do not benefit from horizontal spillovers of FDI. This finding implies that more and more inflows of FDI in a particular sector or industry as they originally belong to in their countries of origin do not necessarily contribute to total factor productivity growth of the domestic firms through any spillover channels.

The estimated results for the forward spillover effects are statistically insignificant in many models. This implies that productivity growth is not transmitted between the foreign firms in the upstream industries and the local firms. In other words, the intermediate consumption of domestic firms supplied by the MNEs does not contribute much to the performance of local firms.

6. Policy suggestions

The interaction effects of mediating factors and spillover channels show that firm experience and degree of internationalization contribute positively to intra- and inter-industry spillover effects on manufacturing firm productivity, emphasizing the relevance and importance of reputation and market openness. The intensity factors for R&D and technology import, on the other hand, have a negative impact on the productivity spillover effects of foreign presence in the same or different industries. Overall, the effects of the mediating variables are substantial contributions to the various channels of spillovers. As a result, governmental interventions are required to promote synergy between internal firm-specific capacity and international activity.

Given the variety of the various manufacturing industries, comprehensive reform packages must be efficiently implemented. The goal should be to maximize the possible production of each producing unit in an efficient way. Once enterprises achieve better productivity scores and rankings, they will continue to push the frontier forward in succeeding periods. In this backdrop, the Indian government must also take measures to establish export promotion platforms. This would also encourage MNEs to manufacture in India and export their goods to the rest of the world. Furthermore, the government's role as a liaison agent is required to allow enterprises to operate for an extended period of time and persist in a competitive market in order to internalize its potentiality.

Funding

This study was not financially supported by any public, commercial, or non-profit funding agencies.

Data availability statement

Research data are not shared.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Bikash Ranjan Mishra: Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Lopamudra D. Satpathy: Writing – review & editing, Software, Data curation. Pabitra Kumar Jena: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization. Tania Dehury: Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

The authors sincerely acknowledge the constructive suggestions and feedback given by Professor Pravakar Sahoo, IEG in the initial drafts of the paper and the anonymous reviewers for their encouragements.

Footnotes

The Arellano and Bond approach, and its extension to the ‘System GMM’ context, is an estimator for situations with ‘small T, large N’ panels, that is few time periods but many individual units, a linear functional relationship, one left-hand variable that is dynamic depending on its own past realisations, and right-hand variables that are not strictly exogenous: correlated with past and possibly current error realisations and more importantly have fixed For all dynamic panel data estimators subject to moment criteria, GMM estimators are consistent, asymptotically normal, and efficient [].

Recently, unit-level production establishment productivity ratings have garnered study attention. Starting productivity estimates with a functioning production function is typical. Cobb-Douglas is usually favored. Despite the translog function's less restricted and more flexible nature, restricting the functional form to the Cobb-Douglas does not seem to make much of a difference numerically. The Cobb Douglas function makes it easy to determine if the calculated coefficients and returns to scale match common sense (Arnold, 2005). We assume the simplest four-factor production function that Eq. (1) describes for this explanation.

Wooldridge J. [] ([34] and 2005).

Arellano and Bover []; Blundell and Bond [].

Here we are focusing on the entire spectrum of manufacturing firms ranging from a two digit classification of 10–33.

Those firms having a less than 10 % (including 0 %) foreign equity holding in the share-holding pattern of ownership are domestically owned firms.

Those firms having a more than 10 % (including 100 %) foreign equity holding in the share-holding pattern of ownership are foreign-owned firms.

Contributor Information

Bikash Ranjan Mishra, Email: bikashranjan.mishra@gmail.com.

Lopamudra D. Satpathy, Email: satpathy.lopa@gmail.com.

Pabitra Kumar Jena, Email: pabitrakumarjena@gmail.com.

Tania Dehury, Email: taniadehury@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Blomström M., Sjöholm F. Technology transfer and spillovers: does local participation with multinationals Matter? Eur. Econ. Rev. 1999;43(4–6):915–923. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keller W. International technology diffusion. J. Econ. Lit. 2004;42(3):752–782. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carstensen K., Farid T. Foreign direct investment in central and eastern European countries: a dynamic panel analysis. J. Comp. Econ. 2004;32:3–22. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ran J., Voon J.P., Li Guangzhong. How does FDI affect China? Evidence from industries and provinces. J. Comp. Econ. 2007;35:774–799. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sinani E., Klaus M.E. Spillovers of technology transfer from FDI: the case of Estonia. J. Comp. Econ. 2004;32:445–466. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorodnichenko Y., Jan S., Katherine T. When does FDI have positive spillovers? Evidence from 17 transition market economies. J. Comp. Econ. 2014;42:954–969. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iwasaki I., Masahiro T. Technology transfer and spillovers from FDI in transition economies: a meta-analysis. J. Comp. Econ. 2016;44:1086–1114. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Görg H., Greenaway D. Much ado about nothing? Do domestic firms really benefit from foreign direct investment? World Bank Res. Obs. 2004;19(2):171–197. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu X.H., Buck T. Innovation performance and channels for international technology spillovers: evidence from Chinese high-tech industries. Res. Pol. 2007;36(3):355–366. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smeets R. Collecting the pieces of the FDI knowledge spillovers puzzle. World Bank Res. Obs. 2008;2:107–138. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Havranek T., Irsova Z. Estimating vertical spillovers from FDI: why results vary and what the true effect is? J. Int. Econ. 2011;85(2):234–244. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aitken B., Harrison A.E. Do domestic firms benefit from direct foreign investment? Evidence from Venezuela. Am. Econ. Rev. 1999;89(3):605–618. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haddad M., Harrison A. Are there positive spillovers from direct foreign investment? Evidence from panel data for Morocco. J. Dev. Econ. 1993;42:51–74. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blalock G., Gertler P. Welfare gains from foreign direct investment through technology transfer to local suppliers. J. Int. Econ. 2008;74(2):402–421. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Javorcik B.S. Does foreign direct investment increase the productivity of domestic firms? In search of spillovers through backward linkages. Am. Econ. Rev. 2004;94(3):605–627. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malik S.K. Conditional technology spillovers from foreign direct investment: evidence from Indian manufacturing industries. J. Prod. Anal. 2015;43(2):183–198. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melitz M.J. The impact of trade on intra industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica. 2003;71(6):1695–1725. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joseph T.J. Spillovers from FDI and absorptive capacity of firms: evidence from Indian manufacturing industry after liberalisation. IIMB Management Review. 2007;19(2):119–130. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kathuria V. Does the technology gap influence spillovers? A post- liberalization analysis of Indian manufacturing industries. Oxf. Dev. Stud. 2010;38(2):145–170. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mondal S., Pant M. FDI and firm competitiveness: evidence from Indian manufacturing. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 2014;49(38):56–64. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saggi K. Trade, foreign direct investment and international technology transfer: a survey. World Bank Res. Obs. 2002;17(2):191–235. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griffith R., Redding S., Reenen J.V. Mapping the two faces of R&D: productivity growth in a panel of OECD industries. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2004;86(4):883–895. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suyanto H.B., Salim R.A. Sources of productivity gains from FDI in Indonesia: is it efficiency improvement or technological progress? Develop. Econ. 2010;48:450–472. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fosuri A., Motta M., Ronde T. Foreign direct investment and spillovers through worker's mobility. J. Int. Econ. 2001;53(1):205–222. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoekman B., Javorcik B.S. In: Global Integration and Technology Transfer. Hoekman B., Javorcik B.S., editors. Palgrave Macmillan; Washington D.C: 2006. Lessons from empirical research on international technology diffusion through trade and foreign direct investment; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin P., Saggi K. In: Does Foreign Direct Investment Promote Development? Moran T.H., Graham E., Blomstrom M., editors. Institute for International Economics, Centre for Global Development; Washington D.C.: 2005. Multinational firms and backward linkages: a critical survey and a simple model; pp. 159–174. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodríguez-Clare A. Multinationals, linkages and economic development. Am. Econ. Rev. 1996;86:852–873. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Markusen J.R., Venables A.J. Foreign direct investment as a catalyst for industrial development. J. Int. Econ. 1999;43(2):335–356. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin P., Saggi K. Multinational firms, exclusivity and backward linkages. J. Int. Econ. 2007;71(1):206–220. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kokko A., Tansini R., Zejan M.C. Local technological capability and productivity spillovers from FDI in the Uruguayan manufacturing sector. J. Dev. Stud. 1996;32(4):602–611. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glass A.J., Saggi K. International technology transfer and the technology gap. J. Dev. Econ. 1998;55(2):369–398. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kathuria V. Productivity spillovers from technology transfer to Indian manufacturing firms. J. Int. Dev. 2000;12(3):343–369. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kathuria V. Foreign firms, technology transfer and knowledge spillovers to Indian manufacturing firms: a stochastic frontier analysis. Appl. Econ. 2001;33(5):625–642. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kathuria V. Liberalisation, FDI, and productivity spillovers - an analysis of Indian manufacturing firms. Oxf. Econ. Pap. 2002;54(4):688–718. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patibandla M., Sanyal A. Foreign investment and productivity: a study of post-reform Indian industry. Rev. Appl. Econ. 2005;1(1):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sasidharan S., Ramanathan A. Foreign direct investment and spillovers: evidence from Indian manufacturing. Int. J. Trade Global Mark. 2007;1(1):5–22. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marin A., Sasidharan S. Heterogeneous MNC subsidiaries and technological spillovers: explaining positive and negative effects in India. Res. Pol. 2010;39(9):1227–1241. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldar B.N., Renganathan V.S., Banga R. Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations; New Delhi: 2003. Ownership and Efficiency in Engineering Firms in India, 1990-91 to 1999-2000. ICRIER Working Paper No.115. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siddharthan N.S., Lal K. Liberalisation, MNE and productivity of Indian enterprises. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 2004;39:448–452. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Behera S.R., Dua P., Goldar B. Foreign direct investment and technology spillover: evidence across Indian manufacturing industries. Singapore Econ. Rev. 2012;57(2):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sahu P.K., Solarin S.A. Does higher productivity and efficiency lead to spillover?: evidence from Indian manufacturing. J. Develop. Area. 2014;48(3):175–193. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paus E.A., Gallagher K.P. Missing links: foreign investment and industrial development in Costa Rica and Mexico. Stud. Comp. Int. Dev. 2008;43(1):53–80. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dimelis S., Louri H. Foreign ownership and production efficiency: a quantile regression analysis. Oxf. Econ. Pap. 2002;54(3):449–469. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takii S. Productivity spillovers and characteristics of foreign multinational plants in Indonesian manufacturing 1990–1995. J. Dev. Econ. 2005;76(2):521–542. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Javorcik B.S., Spatareanu M. To share or not to share: does local participation matter for spillovers from foreign direct investment? J. Dev. Econ. 2008;85(1–2):194–217. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buckley P., Wang C., Clegga J. The impact of foreign ownership, local ownership and industry characteristics on spillover benefits from foreign direct investment in China. Int. Bus. Rev. 2007;16(2):142–158. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin P., Liu Z., Zhanga Y. Do Chinese domestic firms benefit from FDI inflow? Evidence of horizontal and vertical spillovers. China Econ. Rev. 2009;(4):677–691. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barrios S., Strobl E. Foreign direct investment and productivity spillovers: evidence from the Spanish experience. Rev. World Econ. 2002;138(3):459–481. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Damijan J., Knell M., Majcen B., Rojec M. The role of FDI, R&D accumulation and trade in transferring technology to transition countries: evidence from firm panel data for eight transition countries. Econ. Syst. 2003;27(2):189–204. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blalock G., Gertler P. How firm capabilities affect who benefits from foreign technology. J. Dev. Econ. 2009;90(2):192–199. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Girma S., Görg H., Pisu M. Exporting, linkages and productivity spillovers from foreign direct investment. Can. J. Econ. 2008;(1):320–340. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sinani E., Meyer K. Spillovers of technology transfer from FDI: the case of Estonia. J. Comp. Econ. 2004;32(3):445–466. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ponomareva N. New Economic School; Moscow: 2000. Are There Positive or Negative Spillovers from Foreign-Owned to Domestic Firms? Working paper BSP/00/042. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abraham F., Konings J., Slootmaekers V. FDI spillovers in the Chinese manufacturing sector, Evidence of firm heterogeneity. Economies of Transition. 2010;18(1):143–182. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jordaan J. Local sourcing and technology spillovers to Mexican suppliers: how important are FDI and supplier characteristics? Growth Change. 2011;42(3):287–319. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Crespo N., Fontoura M. Determinant factors of FDI spillovers – what do we really know? World Dev. 2007;35(3):410–425. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Girma S., Görg H. Foreign direct investment, spillovers and absorptive capacity: evidence from quantile regressions. University of Nottingham: Nottingham Centre for Research on Globalisation and Economic Policy. 2002 GEP Research Paper No.02/14, 1-31. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Olley G.S., Pakes A. The dynamics of productivity in the telecommunications equipment industry. Econometrica. 1996;64(6):1263–1297. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sugiharti L., Yasin M.Z., Purwono R., Esquivias M.A., Pane D. The FDI spillover effect on the efficiency and productivity of manufacturing firms: its implication on open innovation. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity. 2022;8(2):99. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sun Y., Zhang M., Zhu Y. Do foreign direct investment inflows in the producer service sector promote green total factor productivity? Evidence from China. Sustainability. 2023;15(14) [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang H., Zheng L.J., Zhang J.Z., Behl A., Arya V., Rafsanjani M.K. The dark side of foreign firm presence: how does the knowledge spillover from foreign direct investment influence the new venture performance. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge. 2023;8(3) [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pant M., Pattanayak M. Does openness promote competition: a case study of Indian manufacturing. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 2006;39:4226–4231. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nam H.J., Bang J., Ryu D. Do financial and governmental institutions play a mediating role in the spillover effects of FDI? J. Multinatl. Financ. Manag. 2023;69 [Google Scholar]

- 64.Levinsohn J., Petrin A. Estimating production functions using inputs to control for unobservable. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2003;70(2):317–342. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Research data are not shared.