Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is increasing in incidence worldwide and has become the fastest growing cause of cancer death in the United States, with a median survival of less than 1 year [1–3]. In order to improve survival with current treatments, HCC must be detected early when it is amenable to surgical resection or transplantation [3, 4]. However, multiphase, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging frequently misses lesions less than 1 cm, resulting in diagnostic uncertainty, delayed diagnosis, and early recurrence following resection [5–7]. Innovative technology capable of detecting HCC with enhanced sensitivity and specificity is therefore imperative and pressing.

Radioisotope theranostics, including immuno-positron emission tomography (immunoPET) and radioimmunotherapy (RIT), is an emerging field with the potential to transform HCC diagnosis and therapy [8]. While yttrium-90 microspheres and iodine-131-labeled lipiodol and metuximab are used in radioembolization therapy, there are currently no FDA approved theranostics for HCC [9]. However, glypican-3 (GPC3)-targeted radioisotopes have shown promise in preclinical and early clinical studies [6, 9–20]. GPC3 is a cell surface antigen expressed on up to 80% of HCCs but absent in liver parenchyma and benign lesions, making it an accessible and specific target for a theranostic approach [14, 15, 21]. GPC3-based imaging has the potential to facilitate earlier, definitive HCC diagnosis and subsequent RIT, thus improving patient survival [16].

Our group previously demonstrated that immunoPET using 89Zr-labeled murine antibody targeting GPC3 (89Zr-αGPC3M) reliably identified small HCCs in mice [6, 10, 11]. Natarajan et al. described the use of 89Zr-labeled humanized αGPC3 for HCC detection in a patient-derived xenograft model [16]. We built on this important work by humanizing our radioimmunoconjugate (αGPC3H) and performing in vitro and novel in vivo comparisons to its murine predecessor. Here, we report that 89Zr-αGPC3H targets GPC3 comparably to 89Zr-αGPC3M, resulting in highly specific tumor uptake and successful HCC detection.

Methods

Creative Biolabs, Inc. (Shirley, NY) constructed αGPC3H by engrafting of the parental murine antibody’s complementarity-determining region (CDR). Flow cytometry was used to evaluate in vitro binding of αGPC3M, a chimeric intermediary (αGPC3C), αGPC3H, and αGPC3-deferoxamine (DFO) to HepG2 cells. Specifically, HepG2 cells were resuspended in cold FACS buffer and aliquoted at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/100 μL. Primary and secondary antibodies were sequentially added to the cell suspensions and incubated at 4 °C protected from light for 30 min each. Cells were then washed, resuspended in cold buffer, and analyzed with the Symphony A3 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) flow cytometer. A minimum of 10,000 cells were analyzed for each sample. Data analysis was performed using FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR).

Orthotopic xenograft models of HCC were generated as previously described in athymic nude mice (Jackson Laboratories) [10–12, 22]. A final concentration of 1 × 106 HepG2 cells in 20 μL Geltrex (Gibco, Billings, MT) was injected into the left hepatic lobe. Two weeks after injection, bioluminescence imaging (BLI) was performed using the In Vivo Imaging System Spectrum (PerkinElmer) to verify tumor establishment. Tumor size was calculated in a semi-quantitative manner based on mean photon emission (photons/sec) in a 2D region of interest (ROI) containing the tumor.

Humanized and murine αGPC3 were conjugated with eight equivalents of deferoxamine (DFO)-N-chlorosuccinimide and labeled with positron emitter 89Zr as previously described [10]. Isoelectric focusing was consistent with an average of less than one DFO moiety per antibody in both groups. The radiochemical yield of 89Zr-DFO-αGPC3H and 89Zr-DFO-αGPC3M was 98% and 89%, respectively. Radiochemical purity was determined by instant thin layer chromatography (iTLC) and confirmed by radioactive HPLC. Specific activity was calculated by dividing total radioactivity (GBq) of 89Zr by total mg for each antibody. For simplicity, 89Zr-DFO-αGPC3 is written as 89Zr-αGPC3.

Mice were injected retro-orbitally with 8.1 to 10 megabecquerels (MBq) of 89Zr-αGPC3H (n = 11) or 89Zr-αGPC3M (n = 11). Five days after injection, mice with tumors predicted using BLI (n = 6 per group) underwent imaging using the Inveon small-animal PET/CT scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc. Molecular Imaging, Knoxville, TN). Horos software (Nimble Co., Annapolis, MD) was used for image analysis. Maximum activity concentration (MBq/mL) was measured in a 2D region of interest (ROI) to calculate tumor radioisotope uptake (percent injected dose per milliliter, %ID/mL), tumor-to-liver ratio, and tumor maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax).

Biodistribution studies were performed separately in non-tumor-bearing, non-imaged mice 2 days after injection and in PET-imaged mice after imaging completion. Ionization events (counts per minute, CPM) were measured for each organ and tumor (when applicable) using a Cobra II gamma counter (Packard Bioscience, Meriden, CT) and tissue uptake (%ID/g) was calculated. Livers from PET-imaged mice were processed for histopathology. Details provided in Supplementary Methods.

Results

Humanized αGPC3 and αGPC3-DFO maintains GPC3 binding in vitro

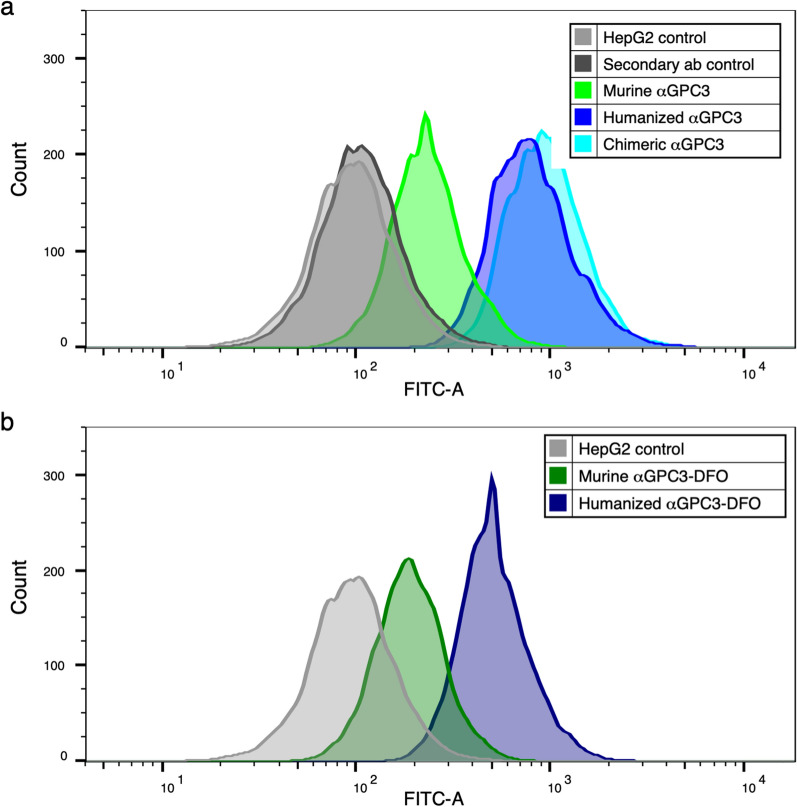

Binding to HepG2 cell surface GPC3 by unconjugated αGPC3M, αGPC3C, and αGPC3H was confirmed by flow cytometry (Fig. 1a). Binding of DFO-conjugated and αGPC3M to GPC3 was overall similar to the unconjugated antibody (Fig. 1b). Binding of αGPC3H and αGPC3C to GPC3 was greater than αGPC3M.

Fig. 1.

Humanized αGPC3 binds to GPC3-expressing HepG2 cells in vitro. a Flow cytometric mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of αGPC3M (green), αGPC3C (aqua), and αGPC3H (blue) compared with controls (unlabeled HepG2 cells and FITC-labeled secondary antibody alone, gray). b MFI of deferoxamine (DFO)-conjugated αGPC3M (dark green) and αGPC3H (navy) compared with control (gray)

Bioluminescence imaging predicts tumor establishment

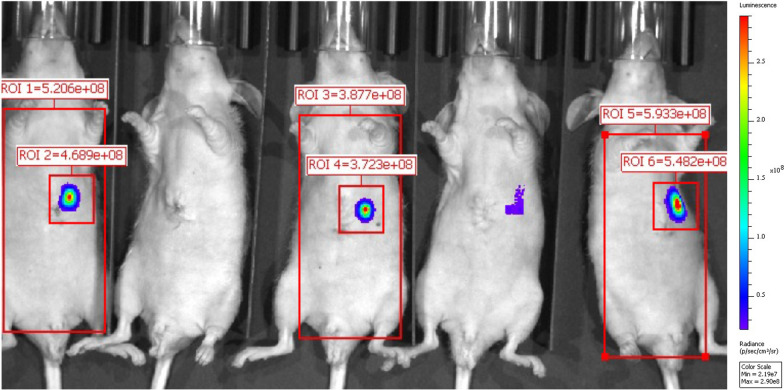

Tumors were identified with BLI (Fig. 2). Mice were assigned to 89Zr-αGPC3H and 89Zr-αGPC3M injection such that mean photon emission (photons/sec) in tumor-containing ROIs was similar between groups (4.1 × 108 vs. 5.3 × 108 photons/s; Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Bioluminescence imaging predicts tumor establishment. Representative BLI image demonstrating predicted tumor establishment in three of the five mice shown. ROI = region of interest. (Position 1–5 from left to right; mean photon emission not calculated for positions two and four)

Table 1.

ImmunoPET and biodistribution data by mouse

| H1 | H2 | H3 | H4 | H5 | H6b | M7 | M8 | M9 | M10 | M11 | M12b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bioluminescence imaging | ||||||||||||

|

Biolum (photons/ second) |

3.7 × 108 | 5.5 × 108 | a | 9.2 × 108 | 7 × 107 | 1.6 × 108 | 1.4 × 108 | 4.1 × 108 | 2.5 × 108 | 2.1 × 109 | 4.7 × 108 | 2 × 107 |

| PET/CT imaging | ||||||||||||

| Tumor uptake (%ID/mL) | 24 | 131 | 67 | 245 | 21 | 15.5 | 14.9 | 24 | 142 | 111 | ||

|

Liver uptake (%ID/mL) |

12.5 | 7.9 | 9.6 | 7.3 | 8.1 | 8.9 | 6.7 | 7.0 | 5.4 | 5.9 | 5.6 | 4.7 |

| Tumor- liver ratio | 1.9 | 16.5 | 6.9 | 34 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 4.5 | 24 | 19.9 | ||

| SUVmax | 9.2 | 47 | 23 | 104 | 9.1 | 6.0 | 5.6 | 9.0 | 55 | 45 | ||

| Biodistribution studies | ||||||||||||

|

Tumor uptake (%ID/g) |

− 426c | 100 | 982 | 109 | 85 | 16.8 | 58 | 458 | 156 | 56 | ||

| Liver uptake (%ID/g) | 20 | 10.2 | 16.2 | 11.3 | 10.5 | 10.9 | 7.6 | 8.3 | 6.1 | 6.4 | 6.5 | 7.7 |

| Tumor- liver ratio | − 21c | 9.8 | 61 | 9.6 | 8.1 | 2.2 | 7.0 | 75 | 24 | 8.8 | ||

| Histopathologic analysis | ||||||||||||

|

Tumor weight (g) |

0.003 | 0.031 | 0.005 | 0.115 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.036 | 0.043 | ||

aNot measured due to minimal apparent signal

bH6, M12: no tumor identified on PET/CT or histopathology (blank = not applicable)

cPET and histologic findings suggest a tumor was present in H1, and the negative %ID/g was due to standard experimental error and a calculated baseline liver uptake that was higher than the measured tumor-containing left hepatic lobe uptake

αGPC3H is amenable to 89Zr radiolabeling

The radiochemical purity of both 89Zr-αGPC3 antibodies was > 98% and the specific activity was 0.14 GBq/mg. Details provided in Supplementary Methods.

Humanized 89Zr-αGPC3 immunoPET reliably identifies tumors

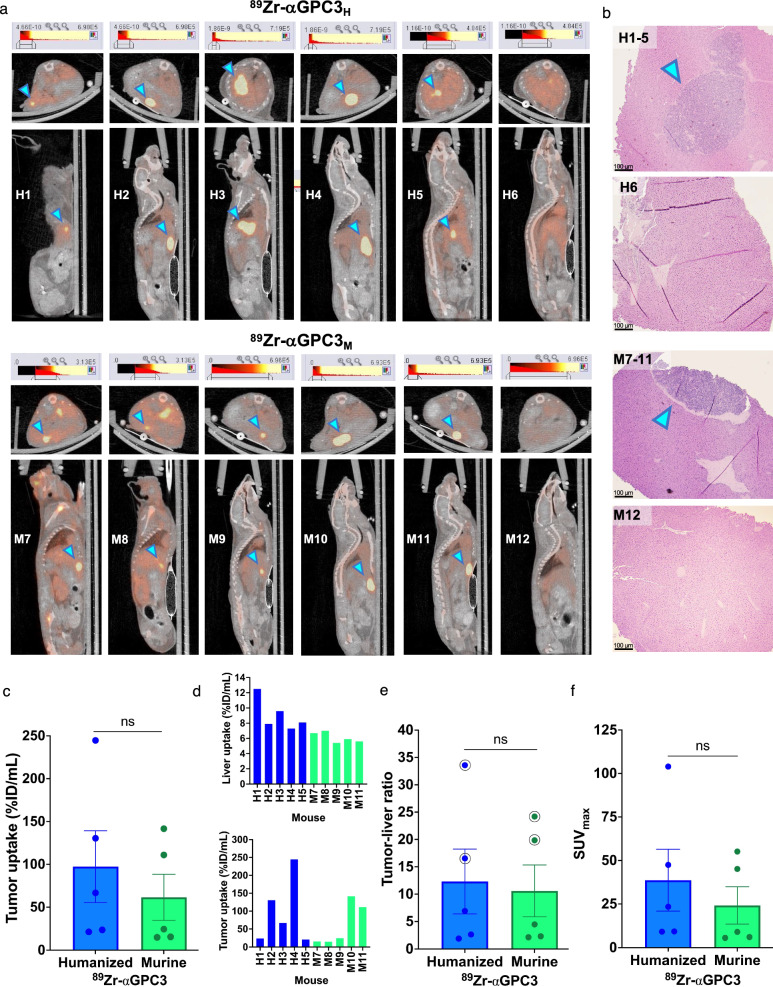

Five of six mice injected with 89Zr-αGPC3H and 89Zr-αGPC3M, respectively, demonstrated increased PET intensity within a focal area in the liver consistent with a tumor (mice H1–H5 and M7–M11; Fig. 3a). Mean bioluminescence calculated from prior IVIS measurements (Table 1) was equivalent between groups (4.8 × 108 vs. 6.3 × 108 ± 4.5 × 108 photon/sec, p = 0.75). Histopathologic analysis identified tumors in mice H1-H5 and M7-M11, but not in mice without PET-identified tumors (H6, M12) (Fig. 3b). Tumor uptake (97 vs. 61 ± 50%ID/mL, p = 0.42) and tumor-to-liver ratios (12 vs. 11 ± 7.6, p = 0.68) were not significantly different between groups, despite significantly increased liver uptake in the 89Zr-αGPC3H-injected mice (9.1 vs 6.1 ± 1.0%ID/mL, p = 0.02) (Fig. 3c–e). SUVmax was equivalent between groups (39 vs. 24 ± 21, p = 0.51) (Fig. 3f).

Fig. 3.

Humanized 89Zr-αGPC3 immunoPET reliably identifies tumors. a Axial (top) and sagittal (bottom) PET/CT images of 89Zr-αGPC3H- and 89Zr-αGPC3M-injected mice. b Select H&E-stained liver sections. Blue arrowheads denote tumors. Scale bars 100 μm. c Tumor radioisotope uptake (%ID/mL). d Liver and tumor %ID/mL by mouse. e Tumor-to-liver ratio of %ID/mL; circle denotes largest tumors. f Tumor maximum standardized uptake (SUVmax). Each point or thin bar (d) denotes the value for each tumor-bearing mouse (n = 5/group); large bars denote the mean with SEM

No difference in tumor radioimmunoconjugate uptake on biodistribution studies

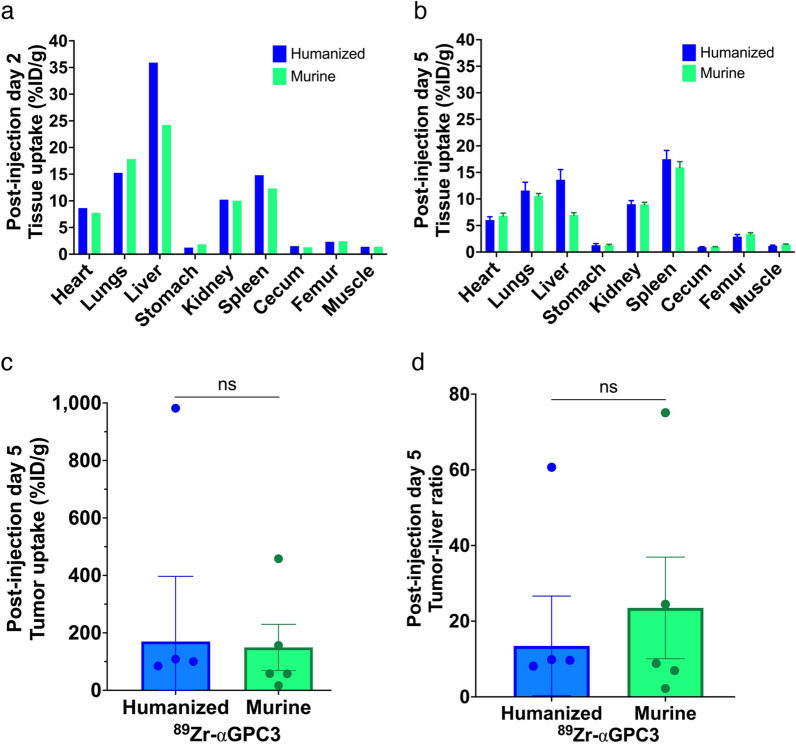

In non-imaged mice, the liver had the highest %ID/g calculated from gamma counter measurements followed by the lungs and spleen, with no significant difference between 89Zr-αGPC3H and 89Zr-αGPC3M-injected mice (mean 10 vs. 8.8 ± 4.6%ID/g, p = 0.77) (Fig. 4a). In PET-imaged mice, tumor uptake was sevenfold greater than other organs, with equivalent organ uptake (mean 7.1 vs. 6.3 ± 2.7%ID/g, p = 0.75), tumor uptake (170 vs. 149 ± 241%ID/g, p = 0.93), and tumor-to-liver ratio of %ID/g (13 vs 24 ± 19, p = 0.61) (Fig. 4b–d).

Fig. 4.

Tissue biodistribution is not significantly different between humanized and murine 89Zr-αGPC3-injected mice. a, b Mean tissue radioisotope uptake (%ID/g) from biodistribution studies in (a) mice not imaged with PET (non-tumor-bearing) (n = 5/group) and b imaged with PET (majority tumor-bearing) (n = 6/group), 2 and 5 days after injection, respectively. Note For mice not imaged with PET (a), organ uptake was calculated as an injection group mean, and thus error bars are not included. c Tumor uptake and d tumor-to-liver ratio (%ID/g) from biodistribution studies in PET-imaged mice. Each point denotes the value for each tumor-bearing mouse (humanized n = 5, murine n = 5; negative values from mouse H1 were included in mean tumor uptake and tumor-to-liver ratio calculations for Fig. 4c, d, but the points are not shown on graph). Bars denote mean with SEM when applicable

Discussion

Humanized αGPC3 specifically targeted GPC3 in vitro and in vivo, enabling HCC detection with immunoPET in an orthotopic xenograft mouse model. This proof-of-concept study builds on our prior research validating a murine radioimmunoconjugate for a theranostic approach to HCC, with potential to improve diagnosis, treatment, and survival [6, 10–12].

Our results demonstrate that humanization of 89Zr-αGPC3 did not alter the highly avid binding to GPC3 on HepG2 cells and liver tumor xenografts. First, flow cytometry established at least equivalent, if not greater, binding of αGPC3H to GPC3 compared with αGPC3M, with minimal change when conjugated with DFO. Next, quality assurance of 89Zr labeling confirmed that 89Zr-αGPC3H maintained high purity and specific activity. The majority of our experiments focused on the novel in vivo comparison between 89Zr-αGPC3H and 89Zr-αGPC3M. Five of six tumors in each group were detected by immunoPET, with no difference between groups in mean bioluminescence. PET/CT data revealed no significant difference in mean tumor uptake and tumor-to-liver ratios (%ID/mL). Similarly, biodistribution analysis showed no difference in mean organ uptake, tumor uptake, and tumor-to-liver ratios (%ID/g).

While finding comparability between 89Zr-αGPC3H and 89Zr-αGPC3M achieved the study’s primary goal, additional details are worth noting. First, tumor uptake varied based on tumor size, with higher uptake in larger tumors as previously demonstrated [6]. %ID/g (gamma counter) results were greater than %ID/mL (PET) due to limited PET/CT spatial resolution causing partial volume effect; hence, there could be a larger discrepancy between %ID/g and %ID/mL values in mice with smaller tumors (e.g., H3, M9) (Fig. 3, Table 1). While further consideration of the clinical impact of partial volume effect is warranted, this finding does highlight the successful detection of a range of tumor sizes with 89Zr-αGPC3 immunoPET. Second, background liver uptake was greater in the 89Zr-αGPC3H group, which could imply Fc-mediated liver uptake of 89Zr-αGPC3H. However, our prior studies of mice injected with 89Zr-αGPC3M compared with non-GPC3-targeting and GPC3-blocked controls demonstrated similar background liver uptake [6, 11, 16]. Furthermore, the tumor-to-liver ratio by nature adjusts for such variables, with no difference between groups suggesting that tumor uptake was also proportionally higher in the humanized antibody group. In fact, tumor-to-liver ratios of 12 or greater indicate 89Zr-αGPC3H is highly specific for GPC3-expressing tumors [16]. Finally, a limitation of our study is that we did not measure blood pool activity in biodistribution analyses and thus could not calculate tumor-to-blood ratios. However, we did include other highly vascular organs, and have shown in prior studies that 89Zr-αGPC3 uptake in tumor and organs such as the liver, kidneys, and spleen is greater than blood pool activity beyond 24 h after injection [6, 11].

Tumor presence was histopathologically confirmed in mice with PET-identified tumors, while no tumors were found on histologic analysis of livers without PET-identified tumors. A second limitation of our study is that, while meticulous gross examination of the liver and histopathologic analysis of suspected tumors was performed, serial sectioning of the entire left hepatic lobe was not undertaken due to funding constraints. Therefore, the discordance between BLI and PET for H6 and M12 is unresolved. Of note, the 3-week interval between imaging modalities was longer than in previous studies and thus tumor involution may have occurred.

Our study is similar to those from other groups in that it underscores the potential of human αGPC3 to detect HCC with immunoPET, however, there are key differences. Tumor-to-liver ratios by PET/CT and biodistribution analyses were notably higher than those reported by Natarajan et al. using a similar 89Zr-labeled human αGPC3 IgG antibody and Fayn et al. using 89Zr-labeled GPC3-targeting HN3 single-domain antibodies. In addition, there was a greater relative difference between tumor uptake and uptake in organs such as the heart, lungs, gastrointestinal tract, and kidneys on biodistribution analysis [16, 17]. While different methods for model development and radioimmunoconjugate injection used may affect the results such that they are not directly comparable [16, 17], it is possible that our humanized antibody has a higher specificity for GPC3-expressing tumors. Furthermore, it should be noted that tumor-to-liver ratios were measured 5 days after injection in this study compared with 1–7 days after injection in the aforementioned studies, however our prior experiments with 89Zr-αGPC3M demonstrated high tumor-to-liver ratios calculated from 4 h up to 7 days after injection [6, 11]. Finally, Carrasquillo et al. conducted a phase I clinical study of PET/CT in HCC patients using αGPC3 codrituzumab labeled with iodine-124 (124I). While this valuable work underscores the clinical translatability of radiolabeled antibodies against GPC3, there was no tumor uptake in one patient and low tumor-to-liver ratios in several others [18]. The authors stated that 89Zr could have been a reasonable alternative to 124I, and our findings support further investigation of 89Zr-αGPC3 immunoPET to overcome challenges encountered with other radioimmunoconjugates. We appreciate the rigorous and ongoing work by our colleagues in the field and believe that parallel approaches to developing GPC3-targeted radiolabeled imaging agents will be beneficial [14–20, 23, 24].

Conclusions

Humanized αGPC3 successfully targeted GPC3 in vitro and in vivo. Compared with our previously validated murine antibody, 89Zr-αGPC3H immunoPET demonstrated comparable HCC detection with highly specific tumor uptake in an orthotopic xenograft mouse model, affirming the efficacy and clinical translatability of 89Zr-αGPC3H immunoPET for HCC detection [16]. Given our GPC3-targeted murine radioimmunoconjugates were previously validated for both immunoPET and cytotoxic RIT, immediate next steps include assessing treatment response using αGPC3H-based RIT. This developing theranostic joins a growing field of other solid tumors, including colorectal, breast, prostate, renal cell cancers, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and neuroendocrine tumors, and has the potential to transform HCC management [10, 25, 26].

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the following individuals and centers for their support of this work: Michael Zittle and Joyce Chambers, Radiation Safety/Environmental Health and Safety; University of Washington (UW)/Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center Translational Bioimaging Core; Dr. Neal Paragas, Radiology Optical Imaging Core; Aurelio Silvestroni, UW Department of Pathology Flow Cytometry Core; Andra Atvars and Robert Hunter, In Vivo Services Core.

Abbreviations

- GPC3

Glypican-3

- immunoPET

Immuno-positron emission tomography

- 89Zr-αGPC3

Zirconium-89-labeled anti-GPC3 antibody

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- CT

Computed tomography

- RIT

Radioimmunotherapy

- CDR

Complementarity-determining region

- DFO

Deferoxamine

- BLI

Bioluminescence imaging

- MBq

Megabecquerels

- ROI

Region of interest

- %ID/mL

Percent injected dose per milliliter

- SUVmax

Maximum standardized uptake value

- 124I

Iodine-124

Author contributions

LKD contributed to study conception and design, performed data collection, analysis, and interpretation of results, and drafted the manuscript. ALL contributed to study conception and design, performed data collection, analysis, and interpretation of results, and provided revisions to manuscript drafts. DKH contributed to study conception and design, prepared materials, and performed data collection and interpretation of results. KPL contributed to study conception and design and provided revisions to manuscript drafts. KEG performed data analysis and contributed to drafting the manuscript. YL (Liu) performed data collection, analysis, and interpretation of results, and provided revisions to manuscript drafts. YL (Li) contributed to study conception and design and provided revisions to manuscript drafts. DSW contributed to study conception and design and provided revisions to manuscript drafts. RM contributed to study conception and design, performed interpretation of results, and provided revisions to manuscript drafts. JOP contributed to study conception and design, performed data collection, analysis, and interpretation of results, and provided revisions to manuscript drafts. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Wayne and Joan Kuni Foundation Imagination Grant and the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA015704.

Availability of data and materials

All data analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Washington (Protocol #4304-02). This study was performed in accordance with the University of Washington Office of Animal Welfare guidelines for the humane use of animals and was carried out in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines. Specifically, the minimum number of mice needed to achieve experimental goals were used. Cages were supplied with sufficient bedding, food, water, and enrichment throughout the experiment. Appropriate anesthetic/analgesic, ophthalmic lubricant, heating pads, and sterile surgical technique were used for survival surgical procedures to minimize animal distress. Mice were monitored closely during and immediately after surgery for adequate depth of anesthesia and full recovery, respectively; isotonic saline was administered subcutaneously for fluid support as needed. Mice were evaluated daily for the first week after surgery for signs of distress, weight loss, agitation, sedation, lameness, failure to eat/drink, poor or aberrant grooming, abnormal posture, wound, or skin ulcerations. A composite of general appearance, body condition score (BCS), body weight, and abdominal girth measurements were used to assess well-being. After the first week, mice were evaluated three times weekly for the remainder of the experiment. For bioluminescence imaging and PET/CT, mice were anesthetized and cared for as described in the Supplementary Methods. Both the research team and Veterinary Services were actively involved in evaluation and care of the mice throughout the experiment. At the completion of the experiment, mice were euthanized using CO2 followed by cervical dislocation according to IACUC protocol.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Philips CA, Rajesh S, Nair DC, Ahamed R, Abduljaleel JK, Augustine P. Hepatocellular carcinoma in 2021: an exhaustive update. Cureus. 2021. 10.7759/cureus.19274. 10.7759/cureus.19274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen ZY, Chhatwal J. Changing epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma and role of surveillance. In: Hoshida Y, editor. Hepatocellular carcinoma: translational precision medicine approaches. Totowa: Humana Press; 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singal AG, Parikh ND, Rich NE, John BV, Pillai A. Hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance and staging. In: Hoshida Y, editor. Hepatocellular carcinoma: translational precision medicine approaches. Totowa: Humana Press; 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021. 10.1038/s41572-020-00240-3. 10.1038/s41572-020-00240-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ayyappan AP, Jhaveri KS. CT and MRI of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2010. 10.1586/era.10.24. 10.1586/era.10.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sham JG, Kievit FM, Grierson JR, et al. Gypican-3-targeted 89Zr PET imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Nuc Med. 2014. 10.2967/jnumed.113.132118. 10.2967/jnumed.113.132118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi J-Y, Lee J-M, Sirlin CB. CT and MR imaging diagnosis and staging of hepatocellular carcinoma: part II. Extracellular agents, hepatobiliary agents, and ancillary imaging features. Radiology. 2014;273(1):30–50. 10.1148/radiol.14132362. 10.1148/radiol.14132362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacobson O, Chen X. Interrogating tumor metabolism and tumor microenvironments using molecular positron emission tomography imaging. Theranostic approaches to improve therapeutics. Pharmacol Rev. 2013;65(4):1214–56. 10.1124/pr.113.007625. 10.1124/pr.113.007625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen H, Teng M, Zhang H, Liang X, Cheng H, Liu G. Advanced radionuclides in diagnosis and therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Chin Chem Lett. 2022. 10.1016/j.cclet.2022.03.079.36091579 10.1016/j.cclet.2022.03.079 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Labadie KP, Ludwig AD, Lehnert AL, et al. Glypican-3 targeted delivery of 89Zr and 90Y as a theranostic radionuclide platform for hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2021. 10.1038/s41598-021-82172-w. 10.1038/s41598-021-82172-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Labadie KP, Lehnert AL, Kenoyer AL, et al. Glypican-3 targeted positron emission tomography detects sub-centimeter tumors in a xenograft model of hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging Res. 2023. 10.1186/s13550-023-00980-9. 10.1186/s13550-023-00980-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ludwig AD, Labadie KP, Seo YD, et al. Yttrium-90-labeled anti-glypican 3 radioimmunotherapy halts tumor growth in an orthotopic xenograft model of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Oncol. 2019. 10.1155/2019/4564707. 10.1155/2019/4564707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang X, Liu H, Sun CK, et al. Imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma patient-derived xenografts using 89Zr-labeled anti-glypican-3 monoclonal antibody. Biomaterials. 2014. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.04.089. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.04.089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishida T, Kataoka H. Glypican 3-targeted therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers. 2019. 10.3390/cancers11091339. 10.3390/cancers11091339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grega SD, Zheng DX, Zheng Q-H. Imaging ligands targeting glypican-3 receptor expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2022;12(4):113–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Natarajan A, Zhang H, Ye W, et al. A humanized anti-GPC3 antibody for immuno-positron emission tomography imaging of orthotopic mouse model of patient-derived hepatocellular carcinoma xenografts. Cancers. 2021. 10.3390/cancers13163977. 10.3390/cancers13163977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fayn S, King AP, Gutsche NT, et al. Site-specifically conjugated single-domain antibody successfully identifies glypican-3-expressing liver cancer by immuno-PET. J Nuc Med. 2023. 10.2967/jnumed.122.265171. 10.2967/jnumed.122.265171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carrasquillo JA, O’Donoghue JA, Beylergil V, et al. I-124 codrituzumab imaging and biodistribution in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging Res. 2018. 10.1186/s13550-018-0374-8. 10.1186/s13550-018-0374-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanaoka H, Nagaya T, Sato K, et al. Glypican-3 targeted human heavy chain antibody as a drug carrier for hepatocellular carcinoma therapy. Mol Pharm. 2015. 10.1021/acs.mocpharmaceut.5b00132. 10.1021/acs.mocpharmaceut.5b00132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.An S, Zhang D, Zhang Y, et al. GPC3-targeted immunoPET imaging of hepatocellular carcinomas. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2022. 10.1007/s00259-022-05723-x. 10.1007/s00259-022-05723-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang HL, Anatelli F, Zhai QJ, Adley B, Chuang S-T, Yang XJ. Glypican-3 as a useful diagnostic marker that distinguishes hepatocellular carcinoma from benign hepatocellular mass lesions. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008. 10.5858/132.11.1723. 10.5858/132.11.1723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perciedusert N, Hurst V, Ahluwalia A, et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 2020;18(7):e3000410. 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000410. 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin F, Clift R, Ehara T, et al. Peptide binder to glypican-3 as a theranostic agent for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Nucl Med. 2024. 10.2967/jnumed.123.266766. 10.2967/jnumed.123.266766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bal C, Ballal S, Kallur K, et al. Abstract 2585: first in human study with a novel peptide binder to glypican-3, demonstrates high specificity as a PET imaging agent in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2024. 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2024-2585. 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2024-2585 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Labadie KP, Hamlin DK, Kenoyer A, et al. Glypican-3-targeted 227Th α-therapy reduces tumor burden in an orthotopic xenograft murine model of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Nucl Med. 2022. 10.2967/jnumed.121.262562. 10.2967/jnumed.121.262562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Werner RA, Weich A, Kricher M, et al. The theranostic promise for neuroendocrine tumors in the late 2010s—Where do we stand, where do we go? Theranostics. 2018;8(22):6088. 10.7150/thno.30357. 10.7150/thno.30357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.