Abstract

The “RNA world” represents a novel frontier for the study of fundamental biological processes and human diseases and is paving the way for the development of new drugs tailored to each patient’s biomolecular characteristics. Although scientific data about coding and non-coding RNA molecules are constantly produced and available from public repositories, they are scattered across different databases and a centralized, uniform, and semantically consistent representation of the “RNA world” is still lacking. We propose RNA-KG, a knowledge graph (KG) encompassing biological knowledge about RNAs gathered from more than 60 public databases, integrating functional relationships with genes, proteins, and chemicals and ontologically grounded biomedical concepts. To develop RNA-KG, we first identified, pre-processed, and characterized each data source; next, we built a meta-graph that provides an ontological description of the KG by representing all the bio-molecular entities and medical concepts of interest in this domain, as well as the types of interactions connecting them. Finally, we leveraged an instance-based semantically abstracted knowledge model to specify the ontological alignment according to which RNA-KG was generated. RNA-KG can be downloaded in different formats and also queried by a SPARQL endpoint. A thorough topological analysis of the resulting heterogeneous graph provides further insights into the characteristics of the “RNA world”. RNA-KG can be both directly explored and visualized, and/or analyzed by applying computational methods to infer bio-medical knowledge from its heterogeneous nodes and edges. The resource can be easily updated with new experimental data, and specific views of the overall KG can be extracted according to the bio-medical problem to be studied.

Subject terms: Data integration, Data acquisition

Background & Summary

The involvement of RNAs in various physiological processes has been ascertained by several studies1–3 that have revealed the pervasive transcription of an unexpected variety of RNA molecules4–7. These molecules can lead to a significant breakthrough in the treatment of cancer, genetic and neurodegenerative disorders, cardiovascular and infectious diseases8. The study of RNA is also one of the most promising avenues of research in therapeutics, as evidenced by the recent success of mRNA-based vaccines for the COVID-19 pandemic9, for the treatment of melanoma10, for the development of new drugs that can target both proteins and mRNA, as well as other non-coding RNAs, and for encoding missing or defective proteins, regulating the transcriptome, and mediating DNA or RNA editing11. Thus, RNA technology significantly broadens the set of druggable targets, and is also less expensive than other technologies (e.g., drug synthesis based on recombinant proteins), due to the relatively simple structure of RNA molecules that facilitate their biochemical synthesis and chemical modifications12. Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) comprise a large range of RNA species13, and a large set of scientific data is made publicly available by several genomics laboratories representing different kinds of interactions among them and with other bio-entities (e.g., genes, proteins, chemicals, diseases, and phenotypes).

The possibility of integrating the interactions that they make available would be of great relevance for knowledge discovery and also for the development of new RNA-based drugs. However, these sources adopt different data models, formats, and conventions for the representation of the bio-entities, and different semantics can be assigned to the proposed interactions. The extraction and integration of information from even two data sources for conducting knowledge discovery activity would require a lot of effort from researchers. To address these issues, Knowledge graphs (KGs)14 have emerged as a compelling abstraction for organizing interrelated knowledge in different domains and a way for integrating heterogeneous information extracted from multiple data sources with the aim of highlighting complex interdependencies and uncovering hidden relationships. KGs can be represented both with property graphs (e.g., Neo4j15) or according to the Resource Description Framework (RDF16) with different advantages and disadvantages17. When a KG is generated according to an ontology, it contains a schema part (denoted TBox or terminologies) and a data part (denoted ABox, facts, or assertions) on top of which different kinds of reasoning activities can be conducted using expressive languages (like OWL18, DL19, or SPARQL20). KGs have started to play a central role also in the life sciences21 for the representation of bio-entities and their interactions and for the application of AI approaches for discovering new knowledge and eventually for explaining it. Different ontologies have been proposed for systematizing the corpus of terms used to describe the function and localization of bio-entities and for offering a formal framework to represent biological knowledge. Specific biological KGs (e.g., PrimeKG22, Human Disease benchmark KG23, ReproTox-KG24, Monarch Knowledge Graph25, Oregano Knowledge Graph26, and Knowledge Base of Biomedicine27) have been recently constructed for conducting different kinds of analysis and supporting research activities.

In this paper we describe RNA-KG, the first ontology-based KG for representing coding and non-coding RNA molecules and their interactions with other biomolecular data as well as with pathways, abnormal phenotypes and diseases to support the study and the discovery of the biological role of the “RNA-world”. RNA-KG contains RDF triples extracted from more than 60 public data sources and also integrates related bio-medical concepts. RNA-KG can be exploited for the study of RNA molecules and the development of innovative graph algorithms to support knowledge discovery in data science. A big effort has been dedicated to the characterization of the data sources and to the identification of the bio-medical ontological concepts that better represent the information provided by the considered data sources and the interactions involving RNA molecules. This work culminated in the construction of a meta-graph that represents all the possible interactions that can be devised from the considered data sources. The relationships have been grounded according to the Relation Ontology (RO28), which ensures common semantics for the different relationships that can be extracted from the sources. Relying on the generated meta-graph and exploiting the Phenotype Knowledge Translator (PheKnowLator23) tool, we extracted 673,825 nodes and 12,692,212 high-quality edges according to the metrics provided in each data source. Different analyses have been conducted to characterize the types of nodes and interactions that are represented in RNA-KG, their distribution, and the topological structure. RNA-KG can be exported according to different knowledge models and can be accessed through a SPARQL endpoint.

RNA-KG takes advantage of a preliminary meta-graph29 and the PheKnowLator system23 for the construction of semantically rich, large-scale biomedical KGs that are Semantic Web compliant and amenable to automatic OWL reasoning, and conforming to contemporary property graph standards. We have used PheKnowLator to download data, transform and/or pre-processing resources into edge lists, construct KGs, and generate a wide range of outputs.

Related Work

For a better understanding of the approach that we have followed in the construction of RNA-KG, we first outline the methods developed for integrating graph-based biomedical heterogeneous data sources and then summarize the main characteristics of the different types of RNA molecules. Finally, we outline the bio-ontologies that can be exploited for the characterization of RNA molecules and the bio-entities with which they are related.

Approaches for the construction of bio-medical knowledge graphs

Data integration is a widely recognized challenge in data management, that prompted the development of numerous approaches to handle relational data30. However, the proliferation of data formats (like CSV, JSON, and XML), alongside the variability in representing similar data types31,32, has underscored the necessity of leveraging ontologies as global models for both accessing (OBDA - Ontology-Based Data Access) and integrating (OBDI - Ontology-Based Data Integration) data sources33. In OBDA, queries are expressed according to ontology terms, with mappings between the ontology and data sources’ schema described through declarative rules. Typically, two approaches have been proposed for enabling access and integration across different data sources: materialization and virtualization. Materialization involves aligning local data formats to the ontology concepts and relationships, whereas virtualization executes transformations on the fly during query evaluation, utilizing mapping rules and ontology. In virtualization, only data pertinent to the query from the original sources are accessed. Materialization offers swift and accurate data access to the data that are collected and organized in a centralized repository. However, frequent changes in data sources may compromise data freshness. Conversely, virtualization allows access to fresh data but may introduce delays and inconsistencies when the local source schema changes. Various approaches exist for specifying mapping rules, including R2RML34 (a W3C standard for relational to RDF mapping), RML35 (a R2RML extension for dealing with multiple formats), SPARQL-Generate36, YARRRML37, and ShExML38, catering to data heterogeneity.

In the biological domain, significant efforts are being dedicated to constructing knowledge graphs (KGs) by integrating diverse public sources, using materialization and virtualization approaches. For instance, Zhang et al.39 utilized a Connecting Ontology (CO) to integrate external ontologies describing involved data sources. By leveraging algorithms for fusion and annotation integration, they generated an enriched KG spanning multiple data sources, annotated with an integrated biological ontology combining Gene40, Trait41, Disease42, and Plant43 ontologies. PrimeKG22 was developed to represent comprehensive views of diseases, integrating over 20 high-quality resources capturing information such as disease-associated perturbations and molecular pathways. Ontologies (e.g. Disease Gene Network, Mayo Clinical Knowledgebase, Mondo, Bgee, and DrugBank) have been used to annotate the collected data. ReproTox-KG24 combines gene, drug, and preclinical small molecule information with birth defect associations, aiming to predict compound-induced birth abnormalities and whether these compounds are likely to cross the placental barrier. The information is extracted from scientific literature taking into account ontologies like HPO44, CDC birth-defect terms45, Geneshot46 for connecting genes with birth-defect terms, DrugCentral47 for connecting drugs with birth-defect terms, and LINCS L1000 data48 for drug-gene associations. Other examples include the Oregano KG for drug repositioning26 and a virtualization approach proposed by Sima et al.49 for federating three data sources (Bgee, OMA, and UNIProtKB) through ontology-based integration. Specifically, starting from the GenEx semantic model for gene expression, mapping rules were proposed to deal with the different formats of the three sources and faced the issue of joint queries across the sources by leveraging SPARQL endpoints.

All these papers point out the difficulties that arise when trying to integrate different data sources that exploit different data models, formats, and ontologies. Specifically, data redundancies, data duplicates, and lack of common identifier mechanisms must be properly addressed. In the case of RNA data integration, we also have to consider the lack of specific ontologies for the description of all possible non-coding RNA sequences, and the presence of ontologies that are not well-recognized by the community because still in their infancy. All these aspects must be properly addressed in the generation of RNA-KG.

RNA molecules

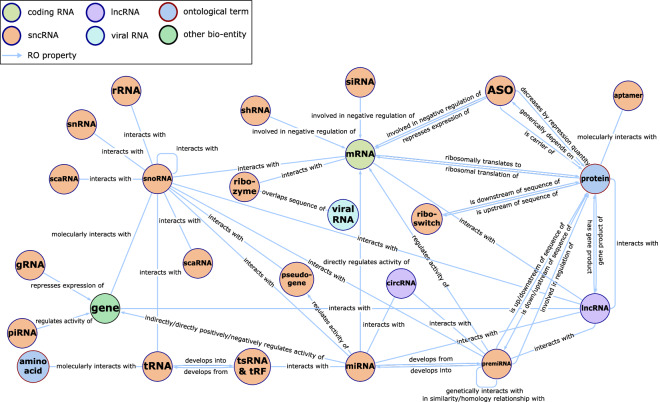

The wide functional role of the different types of RNA molecules opened the way to novel therapeutics able to revolutionize the treatment and prevention of human diseases50. Indeed, RNA molecules play a fundamental role in cell biology, performing a wide range of functions either i) directly by regulating gene expression, exhibiting enzymatic activity, through the modification or regulation of other RNAs or other bio-molecules, or ii) indirectly by being translated into proteins. Figure 1 shows the main classes of RNAs.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the RNA network within a cell.

Coding RNA

Eukaryotic messenger RNA (mRNA) primary transcripts undergo extensive processing to obtain their protein-encoding mature form from pre-mRNA; mRNA is finally translated by ribosomes into sequence of amino acids connected through peptide bonds51.

Non-coding RNA

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) are transcripts not translated into proteins. Two subgroups named long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and small non-coding RNAs (sncRNAs) can be distinguished relying on a length cut-off of 200 nucleotides13.

Long non-coding RNA (lncRNA)

lncRNAs constitute the bulk of transcription products and hold crucial importance in the onset and advancement of diseases52. lncRNAs are involved in competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) regulation, transcriptional regulation and epigenetic regulation53. They can modulate chromatin function, regulate the assembly and function of membraneless nuclear bodies, alter the stability and translation of cytoplasmic mRNAs, and interfere with signaling pathways54. Its transcriptional regulation activity is realized either modifying transcription factor activity, or regulating the association and activity of co-regulators55. lncRNAs are also involved in post-transcriptional regulation. Several studies showed that lncRNAs act as competitive endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) by “sponging” target miRNAs to regulate mRNA expression53. Among lncRNAs, circular RNAs (circRNAs) derive from alternative splicing and can be involved in the regulation of splicing events. Their abnormal expression is detected in numerous human diseases, including cancer and neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease56. lncRNAs are also well-known epigenetic regulators that guide target enzymes necessary to control chromatin organization. For instance, they are involved in the inactivation of X-chromosome in female mammals (e.g., Xist) and in genomic imprinting (e.g., Kcnq1ot1) by recruiting histone modifying enzymes leading to gene silencing57,58. Moreover, lncRNAs and circRNAs can interact directly or indirectly with the enzyme families involved in DNA methylation (i.e., DNMT) and demethylation (i.e., TET) to modulate methylation at specific genomic positions, in turn being involved in many tumors59 but also in physiological processes (e.g., Kcnq1ot1 interacts with Dnmt1 to further control the silencing of ubiquitous imprinted genes58).

Small non-coding RNA (sncRNA)

sncRNAs participate in multiple cellular biological processes, encompassing: translation, RNA interference (RNAi) pathways, splicing and self-cleavage processes, biochemical reactions catalysis, and targeted gene editing.

sncRNAs involved in the translation process

Numerous sncRNAs play various important roles in the translation phase of protein biosynthesis, such as: some types of small rRNA, transfer RNAs (tRNAs), small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs), small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs), and Small Cajal body-specific RNAs (scaRNAs, snoRNAs localized in the Cajal body). While rRNAs are the structural and enzymatic scaffold of the ribosome, tRNAs have a unique structure comprising an acceptor stem that binds to a specific amino acid and a distinct anticodon sequence of three bases complementary to the mRNA codon triplet. This configuration guarantees the accurate translation of mRNA codons into their corresponding chain of amino acids. snRNAs and snoRNAs mainly direct the chemical modification of other RNAs (e.g. rRNA and tRNA) and regulate the chromatin condensation state and DNA accessibility.

sncRNAs associated with RNA interference pathways

RNA interference is a post-transcriptional regulation mechanism of gene expression and its alteration is associated with many pathologies60. sncRNAs participating in RNAi pathways include: microRNAs (miRNAs), short interfering RNAs (siRNAs), short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs), antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs), tRNA-derived fragments (tRFs), and tRNA-derived small RNAs (tsRNAs). Mature miRNAs, siRNAs, shRNAs, and ASOs modulate mRNA expression by inhibiting translation or facilitating the degradation of the target transcript via complementary base pairing. In contrast to siRNAs, a single miRNA has the capacity to concurrently regulate hundreds of protein-coding genes and transcription factors (TFs). The term for miRNAs that are detected in various human biological fluids but originate from exogenous sources is xeno-miRNAs61. On the other hand, ASOs suppress the expression of nuclear targets with greater efficacy while siRNA have better performance in the inhibition of cytoplasmic target62 by recruiting the RNA-induced Silencing Complex (RISC) through siRNA:mRNA duplex, which in turn catalyzes the mRNA cleavage reaction. piRNAs and tRFs similarly leverage RNA interference mechanisms to silence transposons, retrotransposons and repeat sequences, thus preserving genome integrity and cellular homeostasis63.

Aptamers, riboswitches, ribozymes and guide-RNA

RNAs can perform interference activities also exploiting their tertiary structure. Aptamers are short single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules that, due to their specific 3D conformation, can act like chemical antibodies binding a diverse array of targets (e.g., proteins, peptides, carbohydrates, DNA, and RNA)64–66. Riboswitches are small non-coding RNAs that perform a ligand-dependent conformational change triggering alternative splicing and self-cleavage processes that cause the modulation of gene expression and mRNA degradation, which is of pivotal importance for cell survival and adaptation to different environmental stimuli67. Some RNAs (e.g. ribozymes) have enzymatic activity acting as catalysts to accelerate biochemical reactions like mRNA and protein cleavage. Ribozymes can be artificially engineered to target specific sequences and synthetic ribozymes have already been designed against viral RNA. Synthetic guide RNAs (gRNAs) are employed in the CRISPR-Cas9 system, which is utilized for gene editing and gene therapy purposes68.

Biomedical ontologies for the semantic characterization of RNA-KG

Several standard biomedical ontologies can be used to set up common semantics in the considered data sources. Table 1 shows those considered during RNA-KG construction (their specifications are made available in the web portals ebi.ac.uk/ols4 and bioportal.bioontology.org). We selected these ontologies because their terms and hierarchical structures are commonly accepted by the scientific community to unequivocally describe biological classes and entities such as diseases, phenotypes, chemicals, biological processes, proteins, and relations between them. In the case of RNA-KG, we have also taken into account the lack of specific ontologies for the description of all possible RNA sequences (especially non-coding ones), and the presence of bio-ontologies that are yet not well-recognized by the community.

Table 1.

Main biomedical ontologies used for RNA-KG construction (* modified to include only human and viral proteins).

| Name | Abbr. | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Human Phenotype Ontology44 | HPO | Terms representing medically relevant phenotypes and disease-phenotype annotations. |

| Gene Ontology40 | GO | Terms representing attributes of gene products in all organisms. Cellular component, molecular function, and biological process domains are covered. |

| Monarch Merged Disease Ontology98 | Mondo | Terms representing human diseases. |

| Vaccine Ontology99 | VO | Terms in the domain of vaccine and vaccination. |

| Chemical Entities of Biological Interest100 | ChEBI | Structured classification of molecular entities of biological interest focusing on “small” chemical compounds. |

| Uber-anatomy Ontology101 | Uberon | Terms representing body parts, organs and tissues in a variety of animal species, with a focus on vertebrates. |

| Cell Line Ontology102 | CLO | Terms representing publicly available cell lines. |

| PRotein Ontology103* | PRO | Terms representing protein-related entities (including specific modified forms, orthologous isoforms, and protein complexes). |

| Sequence Ontology104 | SO | Terms representing features and properties of nucleic acid used in biological sequence annotation. |

| Pathway Ontology105 | PW | Terms for annotating gene products to pathways. |

| Relation Ontology28 | RO | Terms and properties representing relationships used across a wide variety of biological ontologies. |

Methods

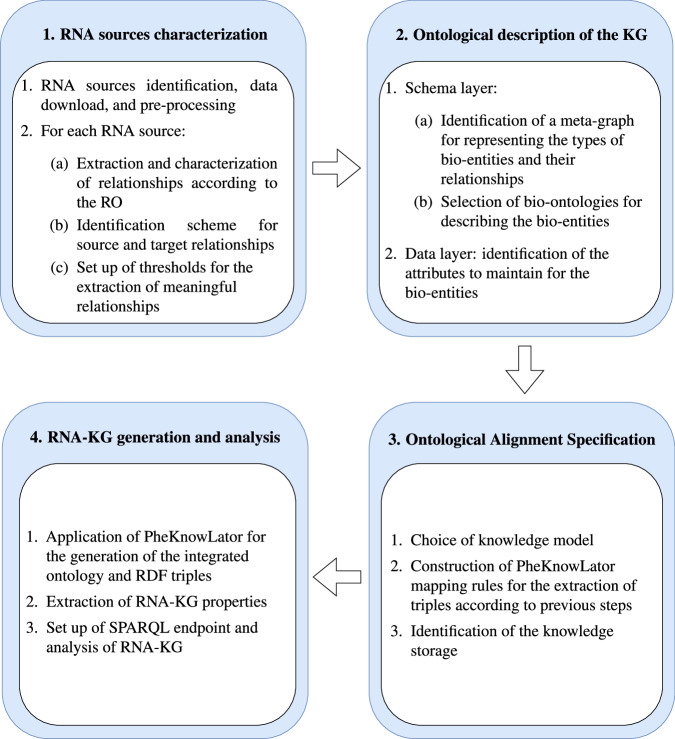

The creation of a KG is a complex task that requires passing through several phases that can be organized in a workflow such as the one reported in Fig. 2. In the remainder of the section, we provide a detailed description of the different issues and adopted solutions for each phase of the creation of our RNA-based KG.

Fig. 2.

Workflow for the construction of RNA-KG.

RNA sources characterization

In this phase, we have identified and analyzed the characteristics of relevant data sources from which the information for feeding the KG has been extracted. This is a well recognized critical initial step in constructing a KG69.

With this aim, an extensive literature review was carried out and ended with the identification of more than 60 public repositories dealing with RNA sequences and annotations developed by well-reputed organizations, published in top journals in the last 10 years, periodically updated, and containing significant amounts of RNA molecules and relevant relationships with other types of molecules and bio-entities. Sources provide data in different formats (e.g., CSV, TSV, gaf, reactome, xlsx, JSON, and HTML) or by issuing queries on content management systems. Once the data were downloaded, Pandas70 DataFrames were used to transform the data into a common format (TSV files) and remove syntactic inconsistencies.

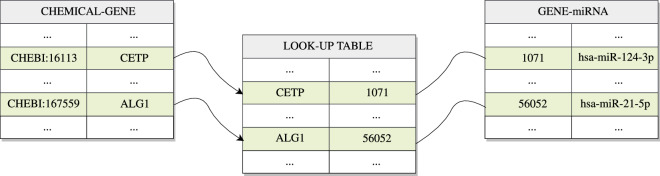

The adoption of different types of molecular identifiers represents another issue. Indeed, the identification scheme encountered in the considered data may vary from the source and target of the relation and could be characterized by different accuracy levels. Four levels have been detected: Well-Reputed (denoted WR), when the identifiers are widely accepted by the scientific community (e.g., NCBI Entrez Gene identifiers); Ontology-based (denoted O), when the identifiers are directly represented with ontological terms; Mapping-based (denoted M), when the identifiers can be obtained by exploiting look-up tables; and Proprietary (denoted P), when all the previous techniques cannot be applied. Once the identification scheme adopted in a source has been classified, appropriate look-up tables for their mapping into the reference ontology have been realized by analyzing synonyms in the reference ontology or by examining the ones provided by the sources themselves to facilitate interoperability with other sources dealing with the same entities. For instance, we employed NCBI Gene Entrez identifiers to represent genes in RNA-KG, but many sources provide the correspondent Gene Symbol. In this case, a look-up table has been used to map gene identifiers into the chosen representation (Fig. 3). To guarantee a high level of reliability of the relationships to be included in RNA-KG, only meaningful relationships have been considered, that is those satisfying constraints that take into account p-values or FDR – False Discovery Rate (e.g., pval < 0.01), experimental validation of results, or scores (denoted with σ) defined as reliable in the considered data source.

Fig. 3.

The relationship between chemicals and miRNA cannot be decoded directly because of the use of different identification schemes. However, by means of a look-up table the relationship can be highlighted.

The main characteristics of the identified repositories are reported in Tables 2, 3, 4, whose entries are organized according to the main type of RNA molecules made available by the source. Sources with miRNA entities can contain hairpin miRNA, xeno-miRNA, and mature miRNA molecules (last ones, in turn, can be classified in -3p and -5p transcripts). Inter RNA sources are those that do not focus on a single RNA type but propose multiple relationships among different types of RNA molecules and bio-entities (e.g., disease in the case of RNADisease or cellular component in the case of RNALocate). Note that no species is present for RNA drugs, vaccines and aptamers because they are synthetic. Regarding the format, the majority of the considered data sources (≥70%) export data in a flat-file format (CSV). Only a small fraction of them (around 20%) provides an API for accessing data stored in a relational database. Only DrugBank and the GO resource offer an RDF data representation coupled with a SPARQL endpoint.

Table 2.

Main data sources (Part I).

| Type | Data source | Species | RNAs | Format | API | Threshold | SI | Relation with | TI | Relation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA | miRBase106 | 271 | 87,474 | rel/CSV | no | validated | WR |

miRNA epi. mod. |

WR M |

58,168 7 |

| miRDB107 | 5 | 7,086 | CSV | no | σ > 80 | WR | mRNA | WR | 3,519,884 | |

| miRNet108 | 10 | 7,928 | rel/CSV | yes | WR |

variant gene snoRNA chemical TF epi. mod. lncRNA pseudogene circRNA disease |

WR WR WR M M M WR WR WR M |

67,532 3,025,487 9,738 4,935 3,311 1,955 31,345 59,417 804,086 32,004 |

||

| miRecords109 | 9 | 384 | CSV | no | validated | WR | mRNA | M | 1,529 | |

| HMDD110 | HS | 1,206 | CSV | no | WR | disease | M | 35,547 | ||

| EpimiR111 | 7 | 617 | CSV | no | WR | epi. mod. | M | 1,974 | ||

| miR2Disease112 | HS | 349 | CSV | no | WR | disease | O | 3,273 | ||

| TargetScan113 | 5 | 5,168 | CSV | no | validated | WR | gene | WR | 2,850,014 | |

| SomamiR114 | HS | 1,078 | CSV | no | validated | WR |

mRNA circRNA lncRNA disease |

WR WR WR M |

2,313,416 428,237 127,025 2,424 |

|

| TarBase115 | 18 | 2,156 | rel/CSV | no | WR | gene | WR | 665,843 | ||

| miRTarBase116 | 28 | 4,630 | CSV | no | WR | gene | WR | 2,200,449 | ||

| SM2miR117 | 21 | 1,658 | CSV | no | WR | chemical | M | 4,989 | ||

| TransmiR118 | 19 | 785 | CSV | no | validated | WR | TF | M | 3,730 | |

| PolymiRTS119 | HS | 11,182 | rel/CSV | no | validated | WR |

disease variant mRNA |

M WR WR |

83,516 16,412 16,412 |

|

| dbDEMC120 | HS | 3,268 | CSV | no | pval < 0.01 | WR | disease | M | 160,800 | |

| TAM121 | HS | 1,209 | CSV | no | WR |

mol. function miRNA TF disease anatomy |

M WR M M M |

2,538 1,218 165 12,516 58 |

||

| PuTmiR122 | HS | 1,296 | CSV | no | WR | TF | M | 12,097 | ||

| miRPathDB123 | HS, MM | 29,430 | CSV | no |

FDR < 0.05 validated |

WR |

mol. function bio. process cell. component pathway |

O O O WR |

1,066,511 4,782,046 1,136,036 986,400 |

|

| miRCancer124 | HS | 57,984 | CSV | no | WR | disease | M | 9,080 | ||

| miRdSNP125 | HS | 249 | CSV | no | validated | WR |

disease variant mRNA |

M WR WR |

786 758 180 |

|

| miRandola126 | 14 | 1,002 | CSV | no | WR |

extracell. form chemical |

M M |

3,262 25 |

||

| mRNA vaccine | DrugBank127 | 4 | rel/RDF | yesS | P | disease | M | 8 |

For each type of RNA molecule, the table reports the corresponding data sources. Moreover, for each data source, Species and RNAs columns specify the number of species and distinct sequences (HS and MM tags refer to specific species Homo sapiens and Mus musculus); Relation with and Relation columns specify the distinct relationships with bio-entities and their number; Format column refers to the data format (CSV for flatfiles, rel for relational tables, RDF, or HTML for web pages); API column reports the availability of API or SPARQL endpoints (the last one denoted with the superscript s) for data access; Threshold column provides identified quality threshold within the source. SI and TI columns contain the class of the identification schemes (WR – Well-Reputed, O – Ontology-based, M – Mapping- based, and P – Proprietary) adopted respectively by source and target(s) within a specific resource (the source is the RNA molecule specified in the Type column, whereas target(s) are specified in the Relation with column).

Table 3.

Main data sources (Part II).

| Type | Data source | Species | RNAs | Format | API | Threshold | SI | Relation with | TI | Relation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s(i/h)RNA | ICBP siRNA128 | HS, MM | 147 | HTML | no | P | mRNA | WR | 147 | |

| DrugBank127 | 4 | rel | yesS | P |

mRNA disease |

WR M |

4 6 |

|||

| RNA aptamer | Apta-Index129 | 230 | rel | no | P |

chemical protein |

M M |

77 153 |

||

| DrugBank127 | 2 | rel/RDF | yesS | P |

protein disease |

M M |

5 6 |

|||

| ASO | eSkip-Finder130 | 4 | 2,196 | rel | no | P | mRNA | WR | 11,778 | |

| DrugBank127 | 12 | rel/RDF | yesS | P |

protein mRNA disease |

M WR M |

12 7 14 |

|||

| gRNA | Addgene131 | 29 | 296 | HTML | no | P | gene | WR | 321 | |

| lncRNA | LncBook132 | HS | 323,950 | rel/CSV | no | validated | WR |

miRNA small protein disease bio. context |

WR WR M M |

146,092,274 772,745 34,536 95,243 |

| LncRNADisease133 | 4 | 6,066 | CSV | no | WR | disease | M | 20,277 | ||

| LncExpDB134 | HS | 101,293 | rel/CSV | no | pval < 0.01 | WR | mRNA | WR | 28,443,865 | |

| dbEssLnc135 | HS, MM | 207 | JSON | no | WR |

bio. role bio. process |

P O |

207 28 |

||

| lncATLAS136 | HS | 6,768 | CSV | no | σ ≥ 28.50 | WR | cell. component | M | 2,429,368 | |

| NONCODE137 | 39 | 644,510 | rel | no | WR | disease | O | 32,226 | ||

| Lnc2Cancer138 | HS | 3,402 | CSV | no | WR | disease | O | 9,254 | ||

| LncRNAWiki139 | HS | 106,063 | rel/CSV | no | WR |

small protein disease bio. context cell. component gene miRNA TF bio. process mol. function chemical pathway |

P M M M WR WR M M M M M |

9,387 7,634 18,453 4,969 509 210 232 10,806 1,800 789 571 |

||

| LncBase140 | 4 | 21,225 | rel/CSV | no |

σ1 ≥ 0.7325 σ2 ≥ 2.497 |

WR |

miRNA anatomy cell cell. component |

WR M M M |

4,229,539 61,905 68,355 73,069 |

|

| TANRIC141 | HS | 12,727 | rel/CSV | no | σ ≥ 0.3 | WR | disease | M | 36,632 | |

| Ribozyme | Ribocentre142 | 1,195 | 21,084 | rel | no | P | bio. process | M | 34 | |

| Rfam143 | 16 | 35 | rel | yes | P |

bio. process cell. component mol. function |

O O O |

8 6 22 |

||

| Riboswitch | TBDB144 | 3,621 | 23,497 | CSV | no | P | protein | M | 23,535 | |

| RSwitch145 | 50 | 215 | rel/CSV | no | P | bact. strain | M | 215 | ||

| tRF & tsRNA | tRFdb146 | 7 | 863 | CSV | no | P |

tRNA cell |

WR M |

792 2,292 |

|

| tsRFun147 | HS | 3,940 | CSV | no | FDR < 0.01 | P |

miRNA tRNA disease |

WR WR M |

45,165 46,798 4,620 |

|

| MINTbase148 | HS | 28,824 | CSV | no | P | tRNA | WR | 125,285 |

Table 4.

Main data sources (Part III).

| Type | Data source | Species | RNAs | Format | API | Threshold | SI | Relation with | TI | Relation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viral RNA | ViroidDB149 | 9 | 9,891 | CSV | no | WR | ribozyme | P | 17,460 | |

| snoRNA | snoDB150 | HS | 751 | CSV | no | WR |

gene mRNA lncRNA miRNA pseudogene rRNA snoRNA snRNA tRNA scaRNA |

WR WR WR WR WR P WR WR P WR |

763 276 45 17 10 735 670 164 164 34 |

|

| tRNA | tRNAdb151 | 681 | 9,758 | rel | no | WR | amino acid | M | 8,872 | |

| GtRNAdb152 | 4,857 | 426,592 | rel | no | WR | epi. mod. | M | 1,366 | ||

| piRNA | piRBase82 | 44 | 218,383,944 | rel | no | WR |

disease variant mRNA lncRNA |

M WR WR WR |

302 1,640,636 30,338 1,199 |

|

| iPiDA-GCN153 | HS | 10,149 | CSV | no | WR | disease | O | 11,981 | ||

| TarpiD154 | 9 | 1,154 | rel | no | WR |

gene disease |

WR M |

28,682 11,869 |

||

| Inter RNA | RNAInter155 | 156 | 455,887 | CSV | yes | σ ≥ 0.2886 | WR |

chemical histone mod. RBP TF protein gene |

M M M M M WR |

10,890 1,060,685 5,200,067 9,323,690 22,543,829 119,377 |

| RNALocate156 | 104 | 123,592 | CSV | yes | WR | cell. component | M | 213,429 | ||

| RNADisease157 | 117 | 91,245 | CSV | yes | σ ≥ 0.95 | WR | disease | O | 343,273 | |

| ncRDeathDB158 | 12 | 648 | CSV | yes | WR | prog. cell death | M | 4,615 | ||

| cncRNADB159 | 21 | 2,002 | CSV | yes | WR | anatomy | M | 2,598 | ||

| ViRBase160 | 152 | 41,718 | CSV | yes | σ ≥ 0.7 | WR |

viral RNA viral protein |

WR M |

719,214 195 |

|

| Vesiclepedia161 | 41 | 20,490 | CSV | no | WR | extracell. form | M | 388,154 | ||

| DirectRMDB162 | 25 | 19,702 | CSV | no | WR | epi. mod. | M | 904,712 | ||

| Modomics163 | 32 | 225 | rel/RDF | yes | WR | epi. mod. | M | 276 | ||

| 12 | 26,245 | rel/RDF | yesS | P |

bio. process mol. function cell. component |

O O O |

48,096 23,767 42,563 |

For the characterization of the relationships that can be extracted from the different data sources, we applied the Relation Ontology (RO). Moreover, the hierarchical organization of concepts in RO allows the expression of different kinds of relationships at different granularities (e.g., the general property interacts with can be substituted with more specific properties such as molecularly interacts with or genetically interacts with). Finally, in case of a lack of specific properties for describing relationships identified in a data source, we decided to approximate the concept/relationship type with a property already present in RO. This choice has the effect of getting a larger agreement on the meaning of the used terms.

Figure 4 summarizes the available relations involving RNA molecules and bio-entities (i.e., gene, protein, chemical, and disease) that we have identified in the different data sources. miRNA-lncRNA interactions are the most numerous. We can retrieve around 150 million distinct relationships of this type from public RNA-based data sources. In terms of cardinality, they are followed by lncRNA-mRNA interactions (~ 28 million) and miRNA-mRNA/miRNA-gene interactions (~ 6 million each). Around 800 thousand distinct relationships can also be identified for protein-lncRNA interactions. These categories of molecules often interact with each other in specific diseases. RNA aptamer-disease is the less represented one because at the current stage only two approved (or under-investigation) RNA aptamer drugs are present in DrugBank and, in general, RNA drugs are less represented than others because they are synthetic (DrugBank siRNA and mRNA vaccine categories contain only 4 approved or under-investigation drugs, ASO drugs are only 12, and RNA aptamer drugs only 2). In addition to the so far discussed data sources, RNAcentral71 is a collector coordinated by the European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI72), which imports non-coding RNA sequences from multiple databases and enables integrated text search, sequence similarity search, bulk downloads, and programmatic data access through a reliable API.

Fig. 4.

Number of relationships involving RNA molecules and relevant bio-entities (gene, protein, chemical, and disease) within the considered RNA sources. Colors represent the ranges of relationships in log scale, as reported in the legend.

To guarantee a high level of homogeneity in the KG, a few tuples have been omitted when the mapping to the reference ontology was not possible. For some types of RNA molecules (especially ncRNA sequences), the look-up tables cannot be adopted because of the lack of a reference ontology with which these molecules can be represented. In these cases, the NCBI Entrez Gene identifiers of the gene from which the specific RNA is transcribed have been extended with a suffix that corresponds to the type of non-coding RNA (e.g., in case of small nucleolar RNA molecules the suffix is ?snoRNA). We remark that the lack of a common ontological representation among heterogeneous sources can cause the same molecule to be represented multiple times under different identifiers. At the current stage of development, we decided to admit their presence, but we will consider de-duplication techniques73,74 that rely on the use of similarity measures on the molecule sequences in future releases.

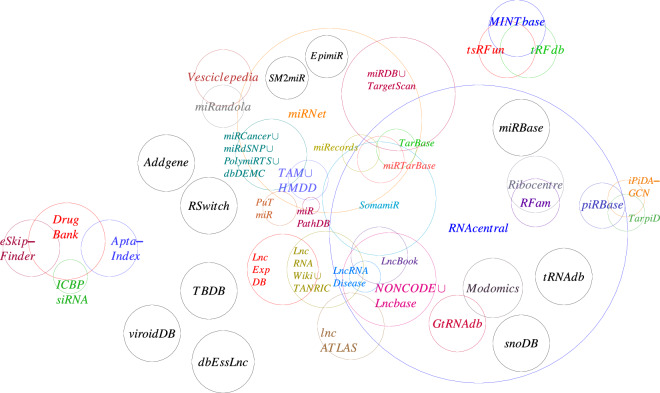

Starting from the need to understand whether the content of the different data sources overlap, we examined the entities and relationships made available in the considered data sources and identified containment (or overlapping) data sources. The result of our study is reported in Fig. 5 where bubbles represent the relationships made available by the data sources. We can note the presence of two prominent clusters (miRNet and RNAcentral) that properly include or overlap the relationships made available by other data sources. The identification of these containments has been exploited to reduce the issue of semantic compatibility. Furthermore, many miRNA and lncRNA sources contain relations that either overlap or are properly included within other sources. We remark that the Inter RNA sources RNAInter, RNALocate, RNAdisease, ncRDeathDB, cncRNAdb, and ViRBase are nicknamed “Sister Projects” because they are updated and maintained by the same research team. Common semantics in “Sister Projects” result useful for data handling because they share a practically identical structure.

Fig. 5.

Bubbles represent the relationships made available from the considered data sources. Overlapping and inclusions of bubbles show the presence of common relationships among the considered data sources.

Ontological description of the KG

In this phase, we identified the classes of bio-entities that need to be managed and the kinds of relationships that can exist among them (schema layer). Moreover, specific instances and the properties that need to be maintained have been highlighted (data layer). This design activity plays a fundamental role in the hierarchy, structure, and content filling of the knowledge graph, and it is the basis for determining the kind of reasoning that can be supported.

Starting from the knowledge gained from the characterization of RNA sources, we moved toward the construction of the ontological schema underlying the KG. A meta-graph was built to include all the kinds of bio-entities and relationships between them outlined in the previous phase. The meta-graph provides both direct and inverse relationships that are considered to guarantee bi-directional navigation of the generated KG. Once classes of bio-entities and their relationships have been identified, we determined the properties that should be kept for them. At the current stage, only fundamental properties of bio-entities have been collected (identifiers, node types, and source provenance). This choice has the advantage of avoiding the explosion of the KG size. However, in future implementations, we wish to include class properties.

Table 5 reports the main relationships of the considered data sources according to the RO ontology. For each relation, the table reports the RO identifier, the corresponding meaning, and, whenever available, the inverse relation. The relation names that are exploited for unidirectional relationships are marked with the * symbol. The general relationships interacts with available in RO with the meaning “A relationship that holds between two entities in which the processes executed by the two entities are causally connected” have been specified in the most specific relationships molecularly interacts with in our classification to represent the situation in which the two partners are molecular entities that directly physically interact with each other (e.g., via a stable binding interaction or a brief interaction during which one modifies the other). We use this relationship to represent a specific interaction process at the molecular level (e.g., aptamer-protein binding interaction or tRNA molecule charged with a specific amino acid). We remark that some authors75,76 suggest that miRNA molecules are involved in negative regulation of complementary miRNA molecules by forming base-pairing interactions. However, this kind of relationship is not present in our data sources. Finally, we note that (the part of property, together with its inverse has part, formally belong to the Basic Formal Ontology – BFO77 – but are imported in RO).

Table 5.

Main relations among bio-entities involving RNA with the RO identifier (* symmetric relationship).

| Relation ID | Name | Inverse Relation ID | Inverse Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| RO:0000056 | participates in | RO:0000057 | has participant |

| RO:0000079 | function of | RO:0000085 | has function |

| RO:0011013 | indirectly positively regulates activity of | ||

| RO:0001015 | location of | RO:0001025 | located in |

| RO:0011016 | indirectly negatively regulates activity of | ||

| RO:0002202 | develops from | RO:0002203 | develops into |

| RO:0002204 | gene product of | RO:0002205 | has gene product |

| RO:0002245 | over-expressed in | ||

| RO:0002246 | under-expressed in | ||

| RO:0002260 | has biological role | ||

| RO:0002263 | acts upstream of | ||

| RO:0002264 | acts upstream of or within | ||

| RO:0002291 | ubiquitously expressed in | RO:0002293 | ubiquitously expresses |

| RO:0002302 | is treated by substance | RO:0002606 | is substance that treats |

| RO:0002314 | characteristic of part of | ||

| RO:0002325 | colocalizes with* | ||

| RO:0002326 | contributes to | ||

| RO:0002327 | enables | RO:0002333 | enabled by |

| RO:0002331 | involved in | ||

| RO:0002387 | has potential to develop into | ||

| RO:0002428 | involved in regulation of | ||

| RO:0002430 | involved in negative regulation of | ||

| RO:0002432 | is active in | ||

| RO:0002434 | interacts with* | ||

| RO:0002435 | genetically interacts with* | ||

| RO:0002436 | molecularly interacts with* | ||

| RO:0002448 | directly regulates activity of | ||

| RO:0002449 | directly negatively regulates activity of | ||

| RO:0002450 | directly positively regulates activity of | ||

| RO:0002479 | has part that occurs in | ||

| RO:0002526 | overlaps sequence of* | ||

| RO:0002528 | is upstream of sequence of | RO:0002529 | is downstream of sequence of |

| RO:0002559 | causally influenced by | RO:0002566 | causally influences |

| RO:0003002 | represses expression of | ||

| RO:0003302 | causes or contributes to condition | ||

| RO:0004033 | acts upstream of or within, negative effect | ||

| RO:0004035 | acts upstream of, negative effect | ||

| RO:0010001 | generically depends on | RO:0010002 | is carrier of |

| RO:0011002 | regulates activity of | ||

| RO:0011007 | decreases by repression quantity of | ||

| BFO:0000050 | part of | BFO:0000051 | has part |

| RO:HOM0000000 | in similarity relationship with* | ||

| RO:HOM0000001 | in homology relationship with* |

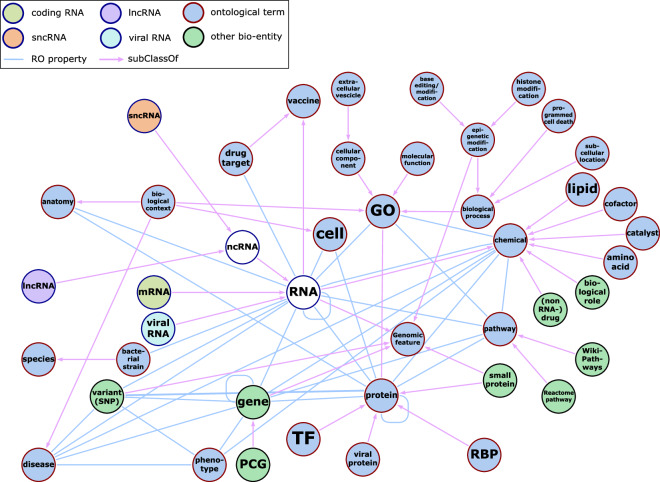

The content of Tables 2–5 is the groundwork for the generation of the meta-graph reported in Fig. 6. The graphical representation provides a global overview of the richness of information that is currently provided. To simplify the visualization of the meta-graph, we omitted most of the non-RNA bio-entities that are known to play an important role in studying the biology (and supporting the discovery) of novel RNA drugs. Moreover, we have omitted some of the relationships extracted from the Inter RNA data sources (see Table 4) because of the limitation of their occurrences. The meta-graph in Fig. 6 can be further extended to include other nodes representing other bio-entities (e.g., diseases, epigenetic modifications, small molecules, tissues, biological pathways, and cellular components) and relationships relevant to the analysis. This “enlarged” meta-graph is quite complex and difficult to represent graphically. Figure 7 shows a very abstract representation by clustering in a single RNA node all the kinds of RNA molecules described in Fig. 6. Then, this node is connected with various bio-entities based on insights extracted from RNA sources and literature.

Fig. 6.

RNA-KG meta-graph. Most non-RNA entities are not represented to simplify the visualization.

Fig. 7.

The complete conceptual RNA-KG meta-graph. RNA nodes are summarized into a few general types (e.g., ncRNA and mRNA) to simplify the visualization.

Table 6 specifies the bio-ontologies that have been exploited for grounding concepts in RNA sources. RNA sources are categorized according to the main treated molecules of RNA (whose characteristics are reported in Tables 2–4).

Table 6.

Bio-ontologies that can be exploited for the characterization of data sources (Part I).

| Type | Data source | GO | Mondo | HPO | VO | ChEBI | Uberon | CLO | PRO | SO | PW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA | miRBase | x | x | ||||||||

| miRDB | x | ||||||||||

| miRNet | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| miRecords | x | ||||||||||

| EpimiR | x | ||||||||||

| HMDD | x | x | x | ||||||||

| miR2Disease | x | x | x | ||||||||

| TargetScan | x | ||||||||||

| SomamiR | x | x | x | ||||||||

| TarBase | x | ||||||||||

| miRTarBase | x | ||||||||||

| SM2miR | x | x | |||||||||

| TransmiR | x | x | |||||||||

| PolymiRTS | x | x | x | ||||||||

| dbDEMC | x | x | x | ||||||||

| TAM | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| PuTmiR | x | x | |||||||||

| miRPathDB | x | x | x | ||||||||

| miRCancer | x | x | x | ||||||||

| miRdSNP | x | x | x | ||||||||

| miRandola | x | x | x | ||||||||

| mRNA vaccine | DrugBank | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| s(i/h)RNA | ICBP siRNA | x | |||||||||

| DrugBank | x | x | x | ||||||||

| RNA aptamer | Apta-Index | x | x | x | |||||||

| DrugBank | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| ASO | eSkip-Finder | x | |||||||||

| DrugBank | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| gRNA | Addgene | x | |||||||||

| lncRNA | LncBook | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| LncRNADisease | x | x | x | ||||||||

| LncExpDB | x | ||||||||||

| dbEssLnc | x | x | x | ||||||||

| lncATLAS | x | x | |||||||||

| NONCODE | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Lnc2Cancer | x | x | x | ||||||||

| LncRNAWiki | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| LncBase | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| TANRIC | x | x |

Ontological alignment specification

In this phase, we identified the KG representation and the kind of storage system to adopt. RDF triples have turned out to be suitable because of their common, flexible, and uniform data model. These properties result in an ontologically-grounded KG for conducting different kinds of analysis and reasoning.

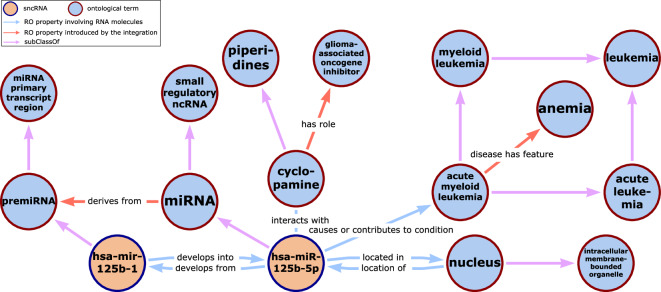

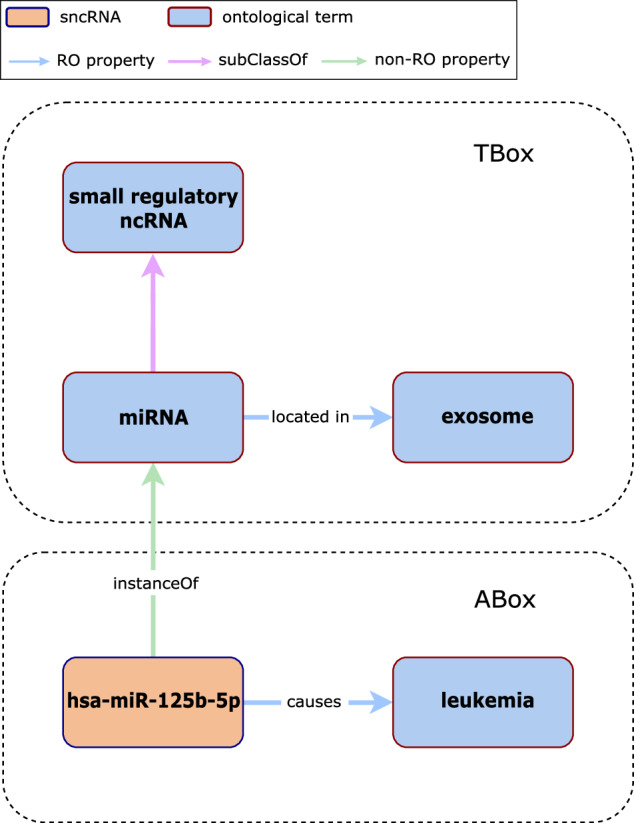

Since a standardized formal definition for the concept of a KG is still lacking, we considered the one adopted by Callahan and colleagues23 in which a KG is a pair < T, A > , where T is the TBox and A the ABox. The TBox represents the taxonomy of a particular domain including classes, properties/relationships, and assertions that are assumed to generally hold within a domain (e.g., a miRNA is a small regulatory ncRNA located in an exosome as depicted in Fig. 8). The ABox describes attributes and roles of class instances (i.e., individuals) and assertions about their membership in classes within the TBox (e.g., hsa-miR-125b-5p is a miRNA whose overexpression has been associated with leukemia). Non-ontological entities (i.e., entities from a data source that are not compliant to a given set of ontologies such as RNA molecules) can be integrated with ontologies using either a TBox (i.e., class-based) or ABox (i.e., instance-based) knowledge model. For the class-based approach, each database entity is represented as subClassOf an existing ontology class, while for the instance-based approach it is represented as instanceOf an existing ontology class.

Fig. 8.

An example of the use of Description Logic (DL) for knowledge modeling. The TBox includes classes (i.e., miRNA, small regulatory ncRNA, and exosome), and the assertions between classes (i.e., “miRNA subClassOf small regulatory ncRNA” and “miRNA is located in exosome”). The ABox includes instances of classes (i.e., hsa-miR-125b-5p) represented in the TBox and assertions about those instances (i.e., “hsa-miR-125b-5p instanceOf miRNA” and “hsa-miR-125b-5p causes leukemia”).

For the construction of the KG we have employed the PheKnowLator ecosystem23 because it offers both approaches for the representation of bio-entities and their relationships, and also because of its simplicity in the identification of the columns containing the molecules’ identifiers and for the specification of their relationships in terms of the RO ontology. PheKnowLator also provides tools to easily generate the ontology that better describes the content of the KG that, besides the terms and relationships of the meta-graph, also includes other ontological terms for supporting the reasoning.

KGs can be easily exported according to different kinds of models offered by PheKnowLator depending on the analyses to be conducted. Even if RNA-KG is made available in all the supported knowledge models, we think that the instance-based, inverse relation, semantically abstracted (OWL-NETS78 without harmonization) configuration is the most suitable to be processed by different kinds of ML algorithms for node and link prediction. This solution ensures that RNA molecules (which lack semantic characterizations in bio-ontologies) and other non-ontological data can be specified as subClassOf specific ontological classes. Moreover, this approach enables the automatic specification of inverse relations among the involved bio-entities. Lastly, OWL-NETS reversibly abstracts ontological biomedical knowledge into a network representation containing only biologically meaningful concepts and relations. Figure 9 shows a small toy-example subgraph extracted from RNA-KG according to the proposed set-up. We can notice the presence of inverse relationships (located in and its inverse location of), and the relation RDF subClassOf connected to entities that do not have a corresponding term in a reference ontology (miRNA molecules are specified as subClassOf the SO term miRNA).

Fig. 9.

Example of a RNA-KG subgraph realized according to the instance-based, inverse relations, semantically abstracted (OWL-NETS without harmonization) parameters.

By studying the characteristics of the data sources, specific mapping rules have been devised through PheKnowLator to extract triples compliant with the adopted ontologies. Mapping rules contain the position of the source and object in the TSV file, the two human-readable labels for subject and object (e.g., mRNA and disease), the type of relationship that holds/exists between them according to RO (e.g., RO_0003302 corresponds to causes or contributes to condition relation), and further detailed options (e.g., thresholds for considering the tuple, row filtering options, transformation options according to the look-up table). These rules will be exploited for the extraction of the triples according to the reference ontology.

Since many ontologies are used in our context, we adopted the PheKnowLator tools to clean ontology files (i.e., remove and normalize errors, eliminate obsolete and/or deprecated entities, remove duplicate classes and class concepts) and merge cleaned ontology files into a single one that describes entirely the structure of RNA-KG and is compliant with our meta-graph.

RNA-KG generation and analysis

In this final phase, the PheKnowLator mapping rules have been issued on the pre-processed data for generating a KG compliant with the meta-graph identified in Phase 2 (ontological description of the KG). In order to evaluate the characteristics of the generated KG, we used the GRAPE library that we recently developed for fast and efficient graph processing and embedding79. By importing RNA-KG into the GRAPE environment, we were able to retrieve relevant topological information and topological oddities that can be useful in identifying (eventual) data duplication. Moreover, GRAPE can be exploited to implement different types of graph embedding techniques that cannot be realized by means of other tools because of the size of the generated KG. Finally, a Blazegraph endpoint80 was created to make RNA-KG freely available and accessible. Using SPARQL, it is possible to extract portions of the graph and use it for different kinds of analysis (see the examples reported in the Supplementary Listings S1–S3). Moreover, the entire RNA-KG can be downloaded from our lab website http://RNA-KG.anacleto.di.unimi.it.

Data Records

RNA-KG data resource is hosted on Zenodo81. We have deposited the KG and all relevant intermediate files in this repository. The current version of RNA-KG (version 0.9) has a single connected component containing 673,825 nodes and 12,692,212 edges. The number of nodes and edges has been substantially reduced by considering only the relationships with high reliability. The construction process of the graph is designed to be periodically updated, including data from other public RNA and related biomedical sources. Moreover, thresholds can be tuned for enlarging or reducing the KG size. Table 7 depicts the main macroscopic topological and structural properties of the current RNA-KG.

Table 7.

Bio-ontologies that can be exploited for the characterization of data sources (Part II).

| Type | Data source | GO | Mondo | HPO | VO | ChEBI | Uberon | CLO | PRO | SO | PW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ribozyme | Ribocentre | x | x | ||||||||

| Rfam | x | x | |||||||||

| Viral RNA | ViroidDB | x | |||||||||

| Riboswitch | TBDB | x | x | x | |||||||

| RSwitch | x | x | |||||||||

| tRF & tsRNA | tRFdb | x | x | ||||||||

| tsRFun | x | x | |||||||||

| MINTbase | x | ||||||||||

| snoRNA | snoDB | x | |||||||||

| tRNA | tRNAdb | x | x | ||||||||

| GtRNAdb | x | x | |||||||||

| piRNA | piRBase | x | x | ||||||||

| iPiDA-GCN | x | x | |||||||||

| TarpiD | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Inter RNA | RNAInter | x | x | x | |||||||

| RNALocate | x | x | |||||||||

| RNADisease | x | x | |||||||||

| ncRDeathDB | x | x | |||||||||

| cncRNADB | x | x | x | ||||||||

| ViRBase | x | x | |||||||||

| Vesiclepedia | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| DirectRMDB | x | x | |||||||||

| Modomics | x | x | x | ||||||||

| The GO resource | x | x |

RNA-KG is made available in N-Triples format. The files made available are described in Supplementary Tables S1–S8. These tables provide a breakdown of the number of nodes by node type and the number of edges by edge type. RNA-KG is available via SPARQL endpoint that can be accessed at http://RNA-KG.anacleto.di.unimi.it.

The dataset also includes the N-Triples KG that merges RNA-KG and Human Disease benchmark KG. Moreover, we provide supporting input files for the generation of RNA-KG by using PheKnowLator. Specifically:

edge_source_list.txt. It contains the organization of the resources directory in which data files downloaded from the repositories are maintained. For each file, it reports the kinds of edges that can be extracted by PheKnowLator.

ontology_source_list.txt. It contains the bio-ontologies chosen to describe the meta-graph. Ontologies employed for building the current release of RNA-KG were updated to date April 22, 2024.

resource_info.txt. It contains the meta-graph. RO properties are used to describe the interactions stored in edge_source_list.txt. Moreover, this file is used to specify prefixes for subject and object nodes (e.g., http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/ for ontological nodes), apply evidence criteria to filter a source, and map node identifiers through look-up tables.

Raw data are also reported on Zenodo and have been collected from the public data sources referenced in Tables 2–4. The data sources’ owners have been contacted to present the initiative and asked the use permission for their data. No one answered that their data cannot be used for academic purposes.

Technical Validation

To evaluate the quality of RNA-KG, several analyses were executed whose results are reported in the following paragraphs.

RNA-KG statistical analysis

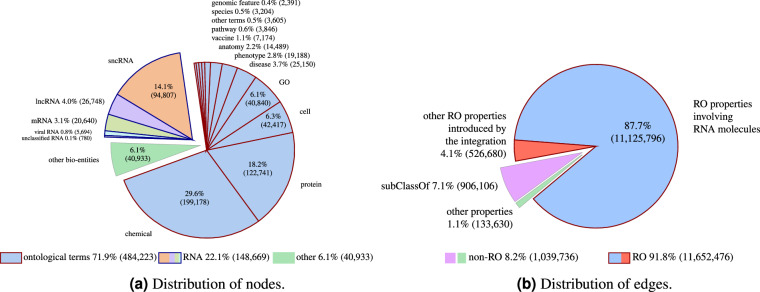

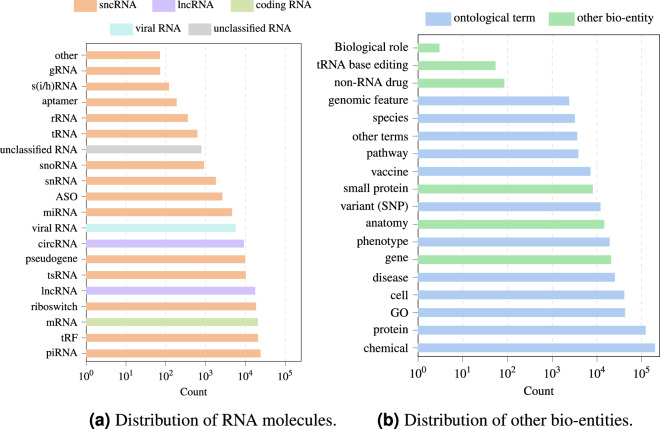

Figure 10a shows the distribution of nodes contained in RNA-KG. Nodes can be classified into nodes representing bio-entities and those representing ontological terms. Bio-entities have been further subdivided into RNA nodes (gathering together sncRNA, mRNA, lncRNA, viral RNA, and unclassified RNA nodes), and non-RNA nodes (named other bio-entities) that contain, for instance, gene and variant (SNP)-typed nodes. Furthermore, Fig. 11a presents the distribution of nodes according to the main type of RNA molecules, detailing the different categories of sncRNA, mRNA, viral RNA, and lncRNA. miRNA, mRNA, and lncRNA molecules are among the most represented in RNA-KG because they are well-studied (many RNA sources have been categorized/typed as lncRNA and miRNA, and mRNA are in relationships with many other ncRNAs as already discussed in the characterization of the data sources). piRNAs are the most numerous sncRNA category because they are very short sequences of ~ 20 − 30 nucleotides that originate from large genomic regions called piRNA clusters, which can be transcribed into long single-strand precursors and further processed into mature piRNAs that often act on the same gene or mRNA transcript in specific diseases or aberrant phenotypes82,83. Additionally, tRF molecules are abundant because they are “fragments” of tRNAs (one tRNA can generate more than one tRF or tsRNA). Riboswitches are also numerous because in RNA-KG we have many riboswitches belonging to human-pathogenic bacteria that can be targets for drugs. Each bacterial riboswitch comes with a different identifier.

Fig. 10.

Pie-chart of: (a) node distribution according to node types; (b) edge distribution according to edge types.

Fig. 11.

Node distribution according to node types.

The unclassified RNA category includes 780 RNA nodes for which a better semantic characterization cannot be assigned because, in the original sources, they are specified as “other RNA”, “miscellaneous RNA”, “unknown RNA”, “ncRNA”, or “RNA molecules to be experimentally confirmed”. Finally, the other category includes sncRNA molecules whose distribution is negligible in RNA-KG (71 sncRNA molecules among ribozymes, enhancer RNAs, vault RNAs, Y RNAs, retained introns, mitochondrial RNAs, small conditional RNAs, and scaRNAs). The total number of mRNA, and in general, RNA, is consistent with experimental studies regarding the number of genes in humans (~ 22-25K protein coding genes and more than 100K total genes84).

Ontological terms shown in Fig. 10a are introduced in the generation of the KG for supporting reasoning activities and can be further classified according to the specific bio-ontology from which they are extracted (e.g., ChEBI for chemicals and HPO for phenotypes). Among them, chemical and protein nodes cover around 47.8% of the total amount of nodes in RNA-KG. This is because ChEBI and PRO both contain many terms representing chemical entities and proteins for Homo sapiens. Figure 11b further details the distribution of ontological terms. Since the considered ontologies contain also terms that do not follow the usual pattern for their identification (e.g., terms representing glycans belong to PRO but their identifier starts with the prefix GNO which differs from the usual one adopted for identifying proteins), we have introduced the category species, with the terms representing the species (all species start with the prefix NCBITaxon), and the category other terms generally containing all the others.

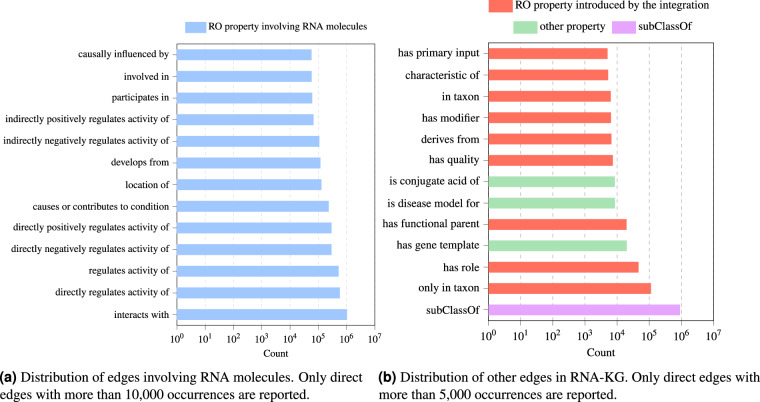

Figure 10b shows the distribution of edges in RNA-KG. Edges have been subdivided into three categories: i) edges representing RO properties that have been further classified in those that describe the interactions among RNA molecules and RO properties introduced by the integrations of the bio-ontologies; ii) edges representing the subClassOf relationships; and iii) edges representing other kinds of relationships not included in RO (e.g., has gene template belonging to PRO). Figure 12a details the distribution of the types of edges involving RNA molecules. As reflected by the organization of the meta-graph, interacts with is the most represented edge type because it encompasses edges for which the original source does not provide specific semantics, whereas the presence of many regulates activity of edges is justified by the vast majority of miRNA molecules within RNA-KG that indeed regulate the activity of, for example, genes and pseudogene and mRNA molecules. Moreover, Fig. 12b shows the distribution of the remaining edges included in RNA-KG. We can notice the prevalence of many subClassOf due to the integration of the bio-ontologies, and because each RNA molecule is subClassOf an appropriate class within SO (e.g., SO_0000276 for miRNA molecules).

Fig. 12.

Edges distribution.

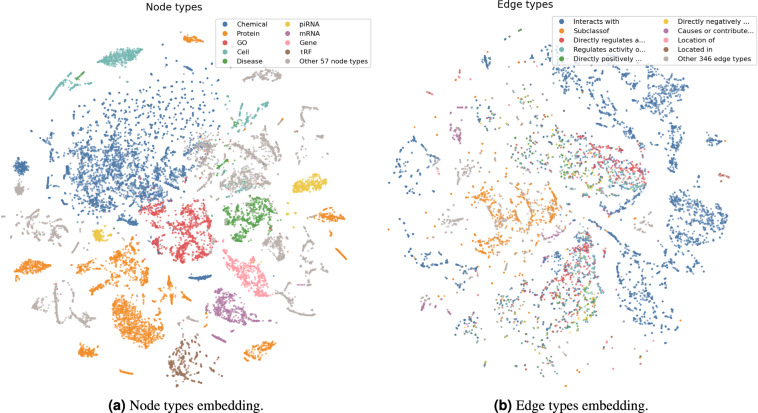

t-SNE representation

Figure 13 shows the t-SNE representation of an embedding of the nodes/edges in RNA-KG by using the GRAPE implementation of Node2Vec with continuous bag of words (CBOW), a random walk-based second-order embedding algorithm85, with walk length equal to 5. Figure 13a shows how the embedding of the node type is able to effectively identify the similarities among the nodes of the same type, thus capturing their function in the network. On the other hand, Fig. 13b depicts the edge embedding for RNA-KG. Also in this case, the embedding is able to capture the similarity between edges with the only exception of the interacts with and regulates activity of relations which seem to overlap several other edge types. This fact is not so surprising considering that the interacts with relation is also used to denote a generic relation between nodes. Moreover, the various subcategories of regulates activity of existing between miRNA and mRNA (e.g., directly regulates activity of and its subtypes directly positively regulates activity of and directly negatively regulates activity of) are not distinguished as the algorithm is homogeneous. In the future, we plan to adopt algorithms that take into account the heterogeneity of RNA-KG.

Fig. 13.

Bidimensional view of RNA-KG embeddings.

Topological analysis

The topological analysis led to the identification of top-5 nodes with the highest degree centrality: microvesicle (GO_1990742) with degree 26.94K (whose type is GO); nucleus (GO_0005634) with degree 20.45K; hcmv-miR-US25-1-5p (human cytomegalovirus hcmv-miR-US25-1-5p mature miRNA) with degree 18.18K and node type miRNA; and, (human) hFOXA1 (PR_P55317) with degree 17.37K and node type protein. We remark that the nodes nucleus and microvescicle represent cellular components used for aggregating different bio-entities existing in the context of a cell and this is the main reason for the high node degree within RNA-KG.

Moreover, the RNA relationships with these kinds of cellular components are enhanced by the semantics of location of edge type together with its respective RO inverse located in. On the other hand, hcmv-miR-US25-1-5p is a human cytomegalovirus (HCMV)-encoded -5p miRNA transcript, whose diagnostic and prognostic value has been proved valid for several human diseases and their clinical implications86. Relationships involving this miRNA sequence are mainly borrowed from ViRBase source. Finally, hFOXA1 is a human forkhead TF known to be the main target of insulin signaling, to regulate metabolic homeostasis in response to oxidative stress, and to interact with chromatin. The central role assumed by hFOXA1 in RNA-KG is quite interesting since this TF is implicated in various human malignancies characterized by altered expression of ncRNAs87.

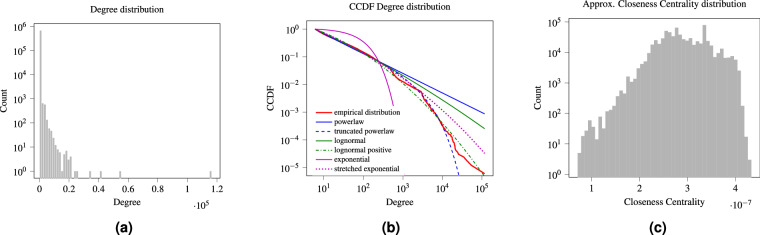

Degree distribution

As shown in Table 7, the average degree of the undirected version of RNA-KG is relatively small (25.23). Despite the sparsity of the graph, the diameter of the KG is also relatively small (33). On the other hand, as shown in Fig. 14a, the degree distribution suggests a heavy-tailed distribution. All of these properties are usually associated with scale-free networks, or more generally to heavy-tailed degree distributions, which is a common structure in real-world complex systems. This motivates the computation of the empirical complementary cumulative distribution function (CCDF) for the degree reported in Fig. 14b. This curve approximates the probability distribution that a randomly selected node has a degree greater than or equal to x. A linear trend in this plot is usually associated with a powerlaw distribution, where the CCDF is given by a function proportional to x1−α. We estimate the power of the distribution using88, obtaining a value of α = 1.708. The theoretical powerlaw obtained for the degrees is shown in Fig. 14b together with other common heavy-tailed distributions. Among these alternatives, we found that the truncated powerlaw distribution fits better according to the log-likelihood ratio criterion89 with p-values smaller than or equal to 10−20. This distribution behaves as a power law’s scaling on a range but is truncated by an exponentially bounded tail according to the distribution x−αe−λx. Further exploration should be made to confirm the powerlaw properties of the graph since they are usually associated with a hierarchical modular structure of the network, entailing algorithmic advantages for its analysis. For instance, the closeness centrality distribution in Fig. 14c exhibits a bimodal behavior, which could be explained by the existence of a well-connected core usually present in heavy-tail degree distribution networks.

Fig. 14.

(a) Node degree distribution (semi-log). (b) Complementary cumulative distribution (CCDF) for the node degree. (c) Approximated closeness centrality distribution.

Treewidth

Treewidth is a graph parameter measuring the structural similarity between a graph and a tree. It is based on the construction of a tree decomposition which captures how subset of nodes can be grouped to form a tree structure that maintains the global structure of the former graph. For instance, graphs having treewidth equal to one are trees, cycles have treewidth two, and clique graphs have a treewidth equal to the number of nodes minus one. The computation of the treewidth is in NP, but several approximation strategies can be used90. The upper bound (10, 611 in Table 7), computed on the undirected version of the KG, can be considered relatively small because it represents about 1.57% of the KG size. This result is consistent with a tree-like hierarchical structure of RNA-KG that has a small and well-connected core.

Isomorphic node groups

RNA-KG contains 761 isomorphic node groups, that is nodes with exactly the same neighbours, node and edge types. Nodes in such groups are topologically indistinguishable, that is, swapping their identifiers would not change the graph topology. These groups involve a total of 9.15K nodes (1.36%) and 272.30K edges (2.15%), with the largest one involving 372 nodes and 10.86K edges. This particular group has degree 10 and is composed of tRFs, specifically i-tRFs (i.e. tRF molecules originating from the internal region of mature tRNA91), and contains sequences that stem from tRNA molecules whose predicted tRNA isotypes/anticodons are all Histidine-GTG. Other detected isomorphic group components involve tRNA molecules that are all interacting with amino acids at a molecular level or tRF and tsRNA sequences that originate from tRNAs with molecular interactions tied to specific amino acids. For example, some of these groups include Aspartic acid-GTC tRNA sequences or tsRNA-Leucines. The remaining isomorphic node groups involve mRNA and piRNA molecules. All these isomorphic node groups deserve further investigation to check whether the involved molecules correspond to the same tRNA, mRNA, piRNA, tsRNA, or tRF and thus their pruning improves the information quality of RNA-KG. Indeed, many of these groups derive from different RNA sources and contain molecules presenting proprietary identifiers that might collapse.

Usage Notes

The methodology we employed to construct RNA-KG enabled us to generate a high-quality KG that includes reliable interactions, validated through experimental methods and/or strongly endorsed by data providers, and whose meaning was meticulously verified to ensure a consistent representation of domain knowledge.

RNA-KG can generate heterogeneous biomedical graphs in different formats that can be processed by graph-based computational tools to infer biomedical knowledge, provide insights into biomolecular mechanisms and biological processes underlying diseases, support the discovery of new drugs, especially those based on RNA, and evaluate biomedical hypotheses in silico. Specific views of RNA-KG can also be generated or extracted by querying the entire KG according to the type of prediction task to be conducted. Predefined views of interest are already provided on RNA-KG’s website and queries, like the one reported in the Supplementary material, can be issued on RNA-KG for extracting meaningful hidden patterns from the data.

RNA-KG is specifically designed to deal with computational tasks involving RNAs by e.g., exploiting the information about ncRNA interactions for gene and protein expression regulation, collected from tens of publicly available databases. By leveraging the biomedical concepts represented in the biomedical ontologies embedded in the KG, RNA-KG can be also analyzed to predict associations and causal relationships of the “RNA world” with diseases and abnormal phenotypes. We also observe that the rich information embedded in the RNA-KG can be leveraged for classical biomedical prediction tasks, including e.g., gene-disease prioritization, drug-target prediction, drug repurposing and synthetic lethality interaction detection92,93.

Most of these biomedical tasks can be modeled as link or node-label prediction problems in heterogeneous graphs. Even if, in principle we could apply methods developed for homogeneous graphs94, to leverage the rich information scattered across the different types of modes and edges of the RNA-KG, we suggest applying methods specifically designed for heterogeneous graphs95. To this end, several AI graph-based methods have been recently proposed to deal with heterogeneous graphs, also in the context of biomedical KGs96. In particular, we foresee that Graph Representation Learning methods, by leveraging the topology of the complex bio-medical heterogeneous graphs to embed them into compact vectorial spaces, could be the most promising choice to properly analyze the complex heterogeneous structure of RNA-KG97.

Supplementary information

An ontology-based knowledge graph for representing interactions involving RNA molecules - Supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was primarily funded by National Recovery and Resilience Plan-NextGenerationEU award from the National Center for Gene Therapy and Drugs based on RNA Technology (G43C22001320007) to AC, GV, MM, MSG, SB. This work was also supported by funding from: MUSA - Multilayered Urban Sustainability Action - Project, funded by the PNRR-NextGeneration EU program ([G43C22001370007], Code ECS00000037) to MM and GV; the National Library of Medicine (T15LM009451 and T15LM007079) to TJC; the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract (DE-AC02-05CH11231) to JR; and, the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) to PNR (5U24HG011449). The authors wish to thank the anonymous reviewers and the editorial board member, prof. Lynn Schriml, for their useful suggestions for improving the quality of our work.

Author contributions

M.M. and G.V. designed the study. Em.C. retrieved, processed, and harmonized datasets. T.J.C., M.M. defined the methodology for the construction of the KG. Em.C. and S.B. worked on the specification of the mapping alignment. G.V., Em.C., and J.G. worked on the description of RNA molecules. Em.C. generated the KG that A.C. and M.S.G. analyzed. S.B. and P.P. set up the SPARQL endpoint and developed the SPARQL queries on the generated KG. G.V., E.C., J.G., J.R., P.N.R. identified the possible applications of the KG in conducting knowledge discovery in life science. M.M., Em.C. and G.V. wrote the initial draft of the paper. All authors reviewed the final version of the manuscript and approved it.

Code availability

The RNA-KG’s project website is at http://RNA-KG.anacleto.di.unimi.it. The code to reproduce results, together with documentation and tutorials, is available in RNA-KG’s GitHub repository at https://github.com/AnacletoLAB/RNA-KG. In addition, the repository contains information and Python scripts to build new versions of RNA-KG as the underlying primary resources get updated and new data become available.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41597-024-03673-7.

References

- 1.Bartel, D. P. & Chen, C.-Z. Micromanagers of gene expression: the potentially widespread influence of metazoan micrornas. Nature Reviews Genetics5, 396–400, 10.1038/nrg1328 (2004). 10.1038/nrg1328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guttman, M. & Rinn, J. L. Modular regulatory principles of large non-coding rnas. Nature482, 339–346, 10.1038/nature10887 (2012). 10.1038/nature10887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cech, T. R. & Steitz, J. A. The noncoding rna revolution—trashing old rules to forge new ones. Cell157, 77–94, 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.008 (2014). 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iyer, M. K. et al. The landscape of long noncoding rnas in the human transcriptome. Nature genetics47, 199–208, 10.1038/ng.3192 (2015). 10.1038/ng.3192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lorenzi, L. et al. The rna atlas expands the catalog of human non-coding rnas. Nature biotechnology39, 1453–1465, 10.1038/s41587-021-00936-1 (2021). 10.1038/s41587-021-00936-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keller, A. et al. mirnatissueatlas2: an update to the human mirna tissue atlas. Nucleic acids research50, D211–D221, 10.1093/nar/gkab808 (2022). 10.1093/nar/gkab808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vo, J. N. et al. The landscape of circular rna in cancer. Cell176, 869–881, 10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.021 (2019). 10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Damase, T. R. et al. The limitless future of rna therapeutics. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology9, 10.3389/fbioe.2021.628137 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Barbier, A. J., Jiang, A. Y., Zhang, P., Wooster, R. & Anderson, D. G. The clinical progress of mrna vaccines and immunotherapies. Nature Biotechnology40, 840–854, 10.1038/s41587-022-01294-2 (2022). 10.1038/s41587-022-01294-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carvalho, T. Personalized anti-cancer vaccine combining mrna and immunotherapy tested in melanoma trial. Nature Medicine29, 2379–2380, 10.1038/d41591-023-00072-0 (2023). 10.1038/d41591-023-00072-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winkle, M., El-Daly, S. M., Fabbri, M. & Calin, G. A. Noncoding rna therapeutics — challenges and potential solutions. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery20, 629–651, 10.1038/s41573-021-00219-z (2021). 10.1038/s41573-021-00219-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paunovska, K., Loughrey, D. & Dahlman, J. E. Drug delivery systems for rna therapeutics. Nature Reviews Genetics23, 265–280, 10.1038/s41576-021-00439-4 (2022). 10.1038/s41576-021-00439-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hombach, S. & Kretz, M.Non-coding RNAs: Classification, Biology and Functioning, 3-17 (Springer International Publishing, 2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Hogan, A. et al. Knowledge graphs. ACM Computing Surveys54, 1–37, 10.1145/3447772 (2021). 10.1145/3447772 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neo4j. Neo4j - the world’s leading graph database. Available at http://neo4j.org/ (2012).

- 16.Beckett, D. & McBride, B. RDF/XML Syntax Specification (Revised) - W3C recommendation. Available at https://www.w3.org/TR/REC-rdf-syntax/ (2004).

- 17.Alocci, D. et al. Property graph vs rdf triple store: A comparison on glycan substructure search. PLOS ONE10, e0144578, 10.1371/journal.pone.0144578 (2015). 10.1371/journal.pone.0144578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.OWL Working Group. Web ontology language (owl) - w3c recommendation. Available at https://www.w3.org/OWL/ (2012).

- 19.Baader, F., Horrocks, I., Lutz, C. & Sattler, U.An Introduction to Description Logic (Cambridge University Press, 2017).

- 20.Prud’hommeaux, E. & Seaborne, A. SPARQL Query Language for RDF - W3C recommendation. Available at https://www.w3.org/TR/rdf-sparql-query/ (2018).

- 21.Chen, J. et al. Knowledge graphs for the life sciences: Recent developments, challenges and opportunities. Transactions on Graph Data Knowl.1, 5:1–5:33, 10.4230/TGDK.1.1.5 (2023).