Abstract

Primary liver cancer is the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality. The increasing prevalence of metabolic syndrome and alcohol consumption, along with the existing burden of viral hepatitis, could significantly heighten the impact of primary liver cancer. However, the specific effects of these factors in the Asia–Pacific region, which comprises more than half of the global population, remain largely unexplored. This study aims to analyze the epidemiology of primary liver cancer in the Asia–Pacific region. We evaluated regional and national data from the Global Burden of Disease study spanning 2010 to 2019 to assess the age-standardized incidence, mortality, and disability-adjusted life years associated with primary liver cancer in the Asia–Pacific region. During the study period, there were an estimated 364,700 new cases of primary liver cancer and 324,100 deaths, accounting for 68 and 67% of the global totals, respectively. Upward trends were observed in the age-standardized incidence rates of primary liver cancer due to metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MASLD) and alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD) in the Asia–Pacific region, as well as an increase in primary liver cancer from Hepatitis B virus infection in the Western Pacific region. Notably, approximately 17% of new cases occurred in individuals aged 15–49 years. Despite an overall decline in the burden of primary liver cancer in the Asia–Pacific region over the past decade, increases in incidence were noted for several etiologies, including MASLD and ALD. However, viral hepatitis remains the leading cause, responsible for over 60% of the total burden. These findings underscore the urgent need for comprehensive strategies to address the rising burden of primary liver cancer in the Asia–Pacific region.

Keywords: Liver cancer, Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, Alcohol-associated liver disease, Epidemiology, Asia–Pacific

Subject terms: Liver cancer, Liver

Introduction

Primary liver cancer, the third leading cause of cancer-related death, imposes a substantial global health and economic burden. Approximately 70% of all primary liver cancers are hepatocellular carcinoma, while around 15% are intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma1–3. The global incidence and mortality rates of primary liver cancer are projected to increase by 55% by 20404. Risk factors for primary liver cancer vary, influenced by sex- and age-specific demographic disparities1. Well-known risk factors include chronic alcohol consumption, chronic viral hepatitis caused by either hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV), metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), and other conditions such as autoimmune hepatitis and cholestatic liver disease5,6.

The 2020 United Nations Human Development Index (HDI) report indicated that countries with lower HDI have higher burdens of primary liver cancer4. There are disparities in the burden of primary liver cancer between high and low HDI countries in the Asia–Pacific region; however, most low HDI countries have the highest estimated incidence and death rates for primary liver cancer4. Notably, although the Asia–Pacific region is currently grappling with declining fertility and aging populations, it will still contain more than half of the world's population over the next five decades7. The prevalence of primary liver cancer attributable to steatotic liver disease (SLD), caused by alcohol and MASLD, is increasing in the Asia–Pacific region, especially among the elderly8–11. Previous studies on primary liver cancer in the Asia–Pacific region have focused on specific countries or etiologies12,13. Therefore, we conducted this study to further explore the epidemiology of primary liver cancer of different etiologies, including alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD), HBV and HCV infection, and MASLD, in the Asia–Pacific region over the last decade using data from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study14,15.

Methods

Data source

The study was conducted using data on the incidence, mortality, and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) of primary liver cancer in the Asia–Pacific region from 2010 to 2019, obtained from the GBD 2019 dataset14,15. Various parameters, including sex, age (overall and 15–49 years), region, and country, were considered in the analysis. The data was accessed using the Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx) query tool (http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool), managed by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. This tool enables users to retrieve data on the annual frequencies and age-standardized rates (ASRs) for the incidence, mortality, and DALYs of primary liver cancer across different demographic and geographic variables. By examining trends and variations in the burden of primary liver cancer, this study provides valuable insights into its epidemiology over the study period.

Estimation methods

The methods used in estimating the burden of primary liver cancer and other data in the GBD 2019 dataset are detailed in the GBD 2019 study4,16. Consistent coding standards were applied to ensure reliable identification of primary liver cancer cases across countries and regions. A rating system ranging from 0 to 5 was implemented in the GBD study to address potential disparities in data quality among countries. These ratings, presented in Supplementary Table 1, were used to evaluate the reliability of cause-of-death data from individual countries. The proportion of primary liver cancer cases attributed to each designated risk factor was calculated. These proportions, pooled across the five liver disease etiologies—alcohol use, HBV, HCV, MASLD, and others—and stratified according to location, sex, and year, were incorporated into five distinct DisMod-MR 2.1 models, which are Bayesian meta-regression-type models17,18. The final proportions were adjusted to ensure they summed up to 100% for each age, sex, year, and location. This rescaling was achieved by dividing each proportion by the sum of all five models. Regarding MASLD, the GBD 2019 collected data under the term nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). However, multiple studies suggest that the data for MASLD and NAFLD can be used interchangeably19–21. Therefore, we will refer to it as MASLD.

The GBD database delineates the Asia–Pacific region precisely; however, we amalgamated both Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific region based on the World Health Organization (WHO) classification. Additionally, recognizing the escalating global burden of early-onset cancer22–25, we conducted a subgroup analysis of early-onset primary liver cancer, defined as the occurrence of primary liver cancer in individuals aged 15–49 years.

Statistical analysis

The incidence, death, and DALYs data for primary liver cancer, along with their 95% uncertainty intervals (UIs), were determined by identifying the 2.5th and 97.5th ranked values across 1000 draws from the posterior distribution. This method accounts for uncertainty in statistical modeling, offering a range of values to allow for a comprehensive understanding of data variability. Age-standardized rates (ASRs) were calculated using the GBD 2019 population estimate method to ensure comparability across different populations and periods.

Changes over time were assessed using annual percent change (APC) and its 95% confidence interval (CI), calculated by the Joinpoint regression program, version 4.9.1.0 (Statistical Research and Applications, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA). This method identifies the year(s) when a trend shift occurs and estimates the APC over the entire study period. It describes changes in data trends by connecting several different line segments on a log scale at "joinpoints." The analysis begins with the minimum number of joinpoints (i.e., 0 joinpoints, representing a straight line) and tests for model fit with a maximum of 4 joinpoints.

Ethical approval

The data utilized in this article were obtained from the publicly available GBD database; thus, obtaining informed consent from the study subjects was not necessary. This study was exempt from the Ethics committee in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Human Research Ethics Unit (HREU) of the Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University (REC number: 67-185-14-1).

Results

Burden of primary liver cancer in the Asia–Pacific region

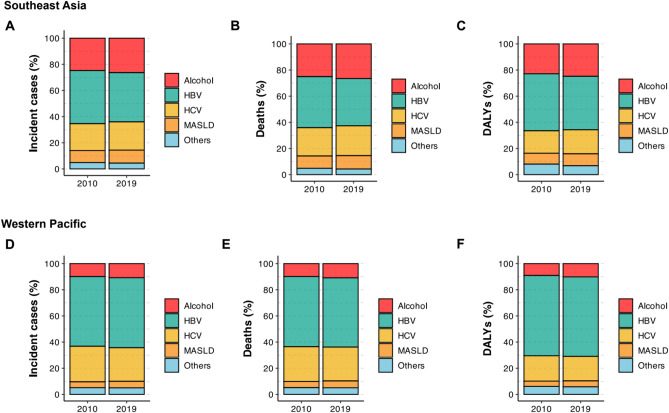

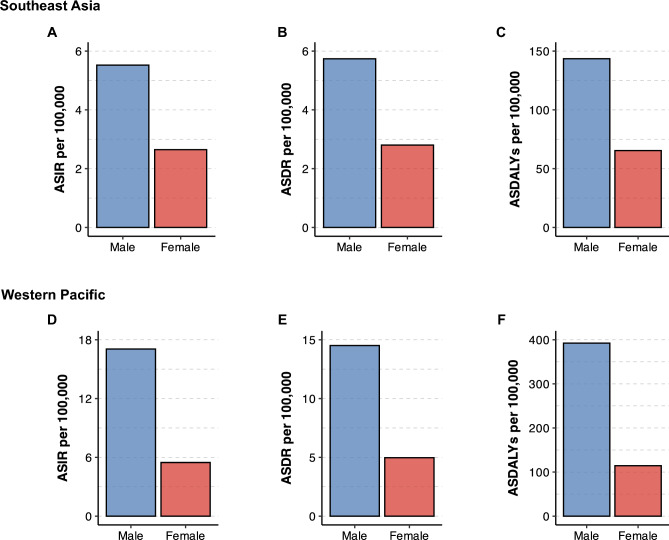

In 2019, the Asia–Pacific region recorded an estimated 364,700 incident cases, 324,100 related deaths, and 8.59 million DALYs for primary liver cancer (Tables 1, 2 and 3). Of these, 69,200 incident cases, 70,000 deaths, and 1.89 million DALYs (19%, 22%, and 22% of the estimates for the Asia–Pacific region, respectively) were recorded in Southeast Asia (Fig. 1A–C). The numbers recorded in the Western Pacific region were considerably higher: 295,500 incident cases, 254,100 deaths, and 6.71 million DALYs (81%, 78%, and 78% of the estimates for the Asia–Pacific region, respectively). The proportion of primary liver cancer in the Asia–Pacific region in each etiology is depicted in Fig. 1A–F. Further details on the sex-stratified burden of primary liver cancer in the Asia–Pacific region are presented in Supplementary Material 1 and Fig. 2A–F.

Table 1.

Incident cases, age-standardized incidence rates, and time trend of primary liver cancer during 2010 to 2019 in the Asia–Pacific region, stratified by sex and etiology.

| Southeast Asia | Western Pacific | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 Incident cases (95% UI) |

2019 Age-standardized Incidence rate per 100,000 (95% UI) |

APC from 2010 to 2019 (95% CI) |

p | 2019 Incident cases (95% UI) |

2019 Age-standardized Incidence rate per 100,000 (95% UI) |

APC from 2010 to 2019 (95% CI) |

p | |

| Overall | 69,200 (60,300 to 79,300) | 4.04 (3.52 to 4.63) | −0.34 (−0.39 to −0.28) | < 0.001 | 295,500 (257,500 to 339,100) | 11.02 (9.62 to 12.61) | 0.03 (−0.06 to 0.13) | 0.506 |

| By sex | ||||||||

| Male | 46,300 (39,700 to 53,900) | 5.52 (4.72 to 6.39) | −0.16 (−0.23 to −0.09) | < 0.001 | 217,900 (183,700 to 259,300) | 17.05 (14.51 to 20.12) | 0.37 (0.28 to 0.45) | < 0.001 |

| Female | 22,900 (19,400 to 27,200) | 2.65 (2.23 to 3.14) | −0.54 (−0.62 to −0.46) | < 0.001 | 77,600 (64,600 to 90,700) | 5.47 (4.57 to 6.41) | −0.98 (−1.03 to −0.92) | < 0.001 |

| By etiology | ||||||||

| Alcohol | 18,200 (13,800 to 23,200) | 1.06 (0.82 to 1.35) | 0.29 (0.05 to 0.53) | 0.016 | 31,900 (24,900 to 40,300) | 1.16 (0.90 to 1.46) | 0.74 (0.61 to 0.87) | < 0.001 |

| Hepatitis B | 26,000 (21,100 to 32,200) | 1.43 (1.15 to 1.78) | −0.99 (−1.06 to −0.91) | < 0.001 | 158,200 (130,500 to 188,500) | 5.85 (4.85 to 6.98) | 0.46 (0.36 to 0.57) | < 0.001 |

| Hepatitis C | 14,900 (11,700 to 18,600) | 0.95 (0.75 to 1.17) | −0.27 (−0.33 to −0.21) | < 0.001 | 75,800 (65,300 to 86,500) | 2.88 (2.48 to 3.28) | −1.27 (−1.37 to −1.16) | < 0.001 |

| MASLD | 6900 (5300 to 8700) | 0.42 (0.33 to 0.53) | 0.21 (0.04 to 0.38) | 0.021 | 14,800 (12,000 to 18,300) | 0.55 (0.45 to 0.68) | 0.91 (0.86 to 0.96) | < 0.001 |

| Others | 3100 (2500 to 3800) | 0.17 (0.14 to 0.21) | −0.31 (−0.48 to −0.14) | < 0.001 | 14,700 (12,100 to 18,000) | 0.58 (0.48 to 0.70) | 0.23 (−0.01 to 0.47) | 0.059 |

Abbreviation: CI: confidence interval, MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, UI: uncertainty interval.

*Significant values are in bold.

Table 2.

Death, age-standardized death rates, and time trend from 2010 to 2019 of primary liver cancer during 2010 to 2019 in the Asia–Pacific region, stratified by sex and etiology.

| Southeast Asia | Western Pacific | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 Death (95% UI) | 2019 Age-standardized Death rate per 100,000 (95% UI) |

APC from 2010 to 2019 (95% CI) |

p | 2019 Death (95% UI) | 2019 Age-standardized Death rate per 100,000 (95% UI) |

APC from 2010 to 2019 (95% CI) |

p | |

| Overall | 70,000 (60,600 to 80,600) | 4.22 (3.67 to 4.84) | −0.48 (−0.69 to −0.27) | < 0.001 | 254,100 (221,700 to 289,500) | 9.50 (8.31 to 10.78) | −0.29 (−0.64 to 0.06) | 0.109 |

| By sex | ||||||||

| Male | 46,500 (39,800 to 54,400) | 5.74 (4.90 to 6.72) | −0.27 (−0.43 to −0.11) | 0.001 | 183,200 (153,400 to 216,500) | 14.51 (12.26 to 16.98) | 0.04 (−0.39 to 0.48) | 0.847 |

| Female | 23,500 (19,500 to 28,100) | 2.80 (2.31 to 3.34) | −0.66 (−1.07 to −0.24) | 0.002 | 70,800 (59,300 to 82,500) | 4.97 (4.17 to 5.79) | −1.12 (−1.25 to −0.98) | < 0.001 |

| By etiology | ||||||||

| Alcohol | 18,600 (14,400 to 23,400) | 1.11 (0.86 to 1.39) | 0.17 (−0.14 to 0.47) | 0.294 | 27,600 (21,300 to 34,700) | 1.00 (0.78 to 1.25) | 0.54 (0.20 to 0.89) | 0.002 |

| Hepatitis B | 25,300 (20,200 to 31,300) | 1.43 (1.14 to 1.76) | −1.12 (−1.27 to −0.97) | < 0.001 | 134,500 (111,400 to 161,500) | 4.96 (4.11 to 5.93) | 0.02 (−0.50 to 0.53) | 0.951 |

| Hepatitis C | 16,000 (12,600 to 19,700) | 1.06 (0.83 to 1.29) | −0.37 (−0.58 to −0.17) | < 0.001 | 65,700 (56,500 to 74,100) | 2.53 (2.17 to 2.85) | −1.36 (−1.51 to −1.21) | < 0.001 |

| MASLD | 7200 (5500 to 9300) | 0.46 (0.35 to 0.59) | 0.09 (−0.10 to 0.28) | 0.305 | 13,400 (10,900 to 16,400) | 0.50 (0.41 to 0.61) | 0.91 (0.54 to 1.28) | < 0.001 |

| Others | 3000 (2400 to 3700) | 0.17 (0.14 to 0.21) | −0.56 (−0.88 to −0.25) | < 0.001 | 12,800 (10,400 to 15,500) | 0.50 (0.41 to 0.60) | −0.13 (−0.82 to 0.56) | 0.708 |

Abbreviation: CI: confidence interval, MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, UI: uncertainty interval.

*Significant values are in bold.

Table 3.

Disability-adjusted life years, age-standardized DALYs rates, and time trend from 2010 to 2019 of primary liver cancer during 2010 to 2019 in the Asia–Pacific region, stratified by sex and etiology.

| Southeast Asia | Western Pacific | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 DALYs (95% UI) | 2019 Age-standardized DALYs rate per 100,000 (95% UI) |

APC from 2010 to 2019 (95% CI) |

p | 2019 DALYs (95% UI) | 2019 Age-standardized DALYs rate per 100,000 (95% UI) |

APC from 2010 to 2019 (95% CI) | p | |

| Overall | 1,887,900 (1,639,500 to 2,169,400) | 103.72 (89.99 to 119.12) | −0.62 (−0.88 to −0.37) | < 0.001 | 6,705,000 (5,793,400 to 7,739,800) | 251.6 (217.75 to 290.24) | −0.10 (−0.49 to 0.30) | 0.625 |

| By sex | ||||||||

| Male | 1,291,200 (1,096,900 to 1,517,600) | 143.52 (122.18 to 168.06) | −0.54 (−0.78 to −0.30) | 0.001 | 5,136,100 (4,237,500 to 6,163,600) | 392.42 (325.58 to 469.09) | 0.26 (−0.21 to 0.73) | 0.279 |

| Female | 596,700 (494,300 to 711,100) | 65.43 (54.19 to 77.80) | −0.80 (−1.17 to −0.44) | < 0.001 | 1,568,900 (1,311,600 to 1,851,700) | 114.37 (95.97 to 134.91) | −1.18 (−1.33 to −1.02) | < 0.001 |

| By etiology | ||||||||

| Alcohol | 468,100 (358,700 to 597,500) | 25.99 (20.06 to 33.07) | 0.05 (−0.32 to 0.42) | 0.788 | 680,700 (515,100 to 860,300) | 24.45 (18.59 to 30.82) | 0.65 (0.29 to 1.03) | 0.001 |

| Hepatitis B | 771,700 (632,900 to 948,000) | 40.47 (32.93 to 49.88) | −1.26 (−1.44 to −1.08) | < 0.001 | 4,076,200 (3,359,500 to 4,917,500) | 152.89 (125.97 to 184.01) | 0.19 (−0.34 to 0.72) | 0.487 |

| Hepatitis C | 347,100 (270,900 to 432,100) | 20.50 (16.07 to 25.35) | −0.42 (−0.64 to −0.20) | < 0.001 | 1,254,700 (1,072,900 to 1,429,500) | 46.15 (39.55 to 52.39) | −1.49 (−1.62 to −1.37) | < 0.001 |

| MASLD/MAFLD | 172,000 (133,700 to 216,600) | 9.77 (7.64 to 12.38) | 0.02 (−0.14 to 0.19) | 0.784 | 305,900 (250,200 to 376,900) | 11.34 (9.31 to 13.88) | 0.92 (0.29 to 1.55) | 0.004 |

| Others | 128,900 (106,800 to 152,800) | 6.99 (5.79 to 8.26) | −0.55 (−0.90 to −0.20) | 0.002 | 387,500 (316,700 to 465,600) | 16.77 (14.01 to 19.79) | −0.29 (−0.93 to 0.35) | 0.379 |

Abbreviation: CI: confidence interval, DALYs: disability-adjusted life years, MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, UI: uncertainty interval.

*Significant values are in bold.

Figure 1.

(A) Proportions of incidences of primary liver cancer in Southeast Asia from 2010 to 2019, stratified according to etiology. (B) Proportions of deaths associated with primary liver cancer in Southeast Asia from 2010 to 2019, stratified according to etiology. (C) Proportions of disability-adjusted life years for primary liver cancer in Southeast Asia from 2010 to 2019, stratified according to etiology. (D) Proportions of incidences of primary liver cancer in the Western Pacific region from 2010 to 2019, stratified according to etiology. (E) Proportions of deaths associated with primary liver cancer in the Western Pacific region from 2010 to 2019, stratified according to etiology. (F) Proportions of disability-adjusted life years for primary liver cancer in the Western Pacific region from 2010 to 2019, stratified according to etiology. DALYs, disability-adjusted life years; MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease.

Figure 2.

(A) Age-standardized incidence rates of primary liver cancer in Southeast Asia in 2019, stratified according to sex. (B) Age-standardized death rates of primary liver cancer in Southeast Asia in 2019, stratified according to sex. (C) Age-standardized disability-adjusted life years for primary liver cancer in Southeast Asia in 2019, stratified according to sex. (D) Age-standardized incidence rates of primary liver cancer in the Western Pacific region in 2019, stratified according to sex. (E) Age-standardized death rates of primary liver cancer in the Western Pacific region in 2019, stratified according to sex. (F) Age-standardized disability-adjusted life years for primary liver cancer in the Western Pacific region in 2019, stratified according to sex. ASDALYs, age-standardized disability-adjusted life years; ASDR, age-standardized death rates; ASIR, age-standardized incidence rates; MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease.

The age-standardized incidence rate (ASIR), age-standardized death rate (ASDR), and age-standardized DALYs (ASDALYs) of primary liver cancer in Southeast Asia were 4·04 (95% UI, 3.52 to 4.63), 4.22 (95% UI, 3.67 to 4.84), and 103.72 (95% UI, 89.99 to 119.12), respectively (Tables 1, 2 and 3). From 2010 to 2019, Southeast Asia experienced a decline in the ASIR (APC: −0.34%, 95% CI −0.39 to −0.28%), ASDR (APC: −0.48%, 95% CI −0.69 to −0.27%), and ASDALYs (APC: −0.62%, 95% CI −0.88 to −0.37%) of primary liver cancer (Tables 1, 2 and 3). The ASIR, ASDR, and ASDALYs of primary liver cancer in the Western Pacific region were 11.02 (95% UI, 9.62 to 12.61), 9.50 (95% UI, 8.31 to 10.78), and 251.60 (95% UI, 217.75 to 290.24), respectively (Tables 1, 2 and 3). In contrast to the changes in trends observed in Southeast Asia, the ASIR, ASDR, and ASDALYs recorded in the Western Pacific region were stable over the study period (Tables 1, 2 and 3). The change in ASIR, ASDR, and ASDALYs is listed in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Burden of primary liver cancer in the Asia–Pacific region is categorized according to etiology

Of all the primary liver cancer etiologies, HBV had the highest number of incident cases (n = 184,200), number of deaths (n = 159,800), and DALYs (4.85 million) of primary liver cancer (Tables 1, 2 and 3), followed by HCV, with 90,800 incident cases, 81,700 deaths, and 1.60 million DALYs. The ASIR, ASDR, and ASDALYs of primary liver cancer in the Asia–Pacific region stratified according to etiology are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. The ASIR, ASDR, and ASDALYs of primary liver cancer caused by HBV were the highest, followed by those of primary liver cancer caused by HCV and alcohol use, and lowest with MASLD and other etiologies.

In Southeast Asia, the ASIRs of primary liver cancer caused by HBV (APC: −0.99%, 95% CI −1.06 to −0.91%), HCV (APC: −0.27%, 95% CI −0.33 to −0.21%), and other etiologies (APC: −0.31%, 95% CI −0.48 to −0.14%) decreased, whereas those of primary liver cancer caused by ALD (APC: 0.29%, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.53%) and MASLD (APC: 0.21%, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.38%) increased (Table 1). The ASDRs of primary liver cancer caused by HCV (APC: −0.37%, 95% CI −0.58 to −0.17%), HBV (APC: −1.12%, 95% CI −1.27 to −0.97%), and other etiologies (APC: −0.56%, 95% CI −0.88 to −0.25%) decreased, whereas those of primary liver cancer caused by ALD and MASLD remained stable (Table 2). The ASDALYs of primary liver cancer caused by HCV (APC: −0.42%, 95% CI −0.64 to −0.20%), HBV (APC: −1.26%, 95% CI −1.44 to −1.08%), and other etiologies (APC: −0.55%, 95% CI −0.90 to −0.20%) slowly decreased, whereas those of primary liver cancer caused by ALD and MASLD did not change significantly (Table 3).

In the Western Pacific region, the ASIR of primary liver cancer caused by HCV (APC: −1.27%, 95% CI −1.37 to −1.16%) decreased, while those of primary liver cancer caused by HBV (APC: 0.46%, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.57%), ALD (APC: 0.74%, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.87%), and MASLD (APC: 0.91%, 95% CI 0.86 to 0.96%) increased (Table 1). The ASDR of primary liver cancer caused by HCV (APC: −1.36%, 95% CI −1.51 to −1.21%) decreased, those of primary liver cancer caused by HBV and other etiologies remained stable, and those of primary liver cancer caused by ALD (APC: 0.54%, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.89%) and MASLD (APC: 0.91%, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.28%) increased (Table 2). Similarly, the ASDALYs of primary liver cancer caused by HCV decreased (APC: −1.49%, 95% CI −1.62 to −1.37%), those of primary liver cancer caused by ALD (APC: 0.65%, 95% CI 0.29 to 1.03%) and MASLD (APC: 0.92%, 95% CI 0.29 to 1.55%) increased, and those of primary liver cancer caused by HBV and other etiologies remained stable (Table 3).

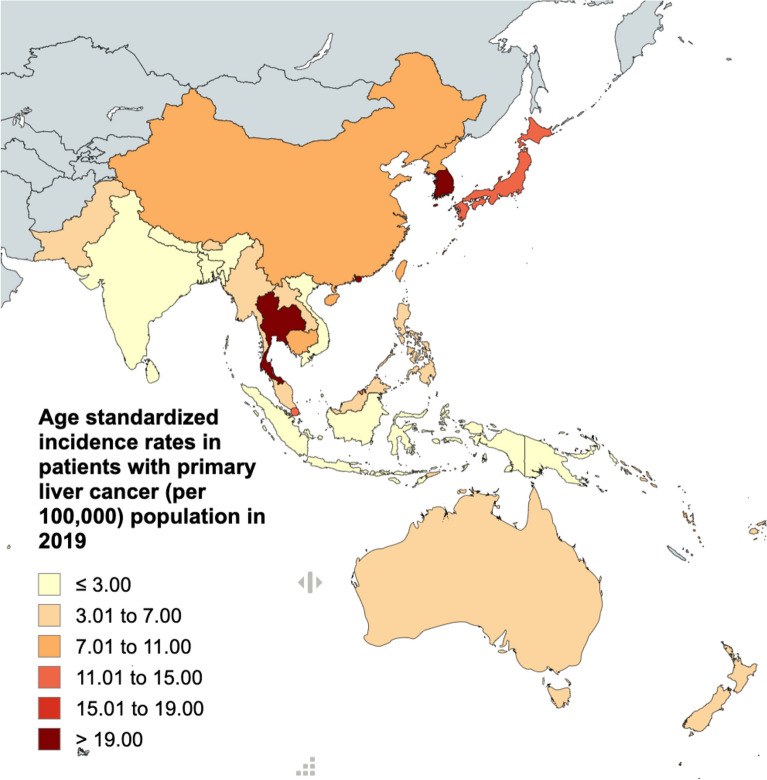

The burden of primary liver cancer in each country in the Asia–Pacific region

The ASIRs and ASDRs of primary liver cancer in the Asia–Pacific region categorized according to country are presented in Fig. 3A,B and Supplementary Tables 2 and 3. ASIRs ranged from 1.53 (95% UI, 1.19 to 1.96) in Papua New Guinea to 24·33 (95% UI, 17.65 to 31.90) in Tonga. In addition to Tonga, the countries with the highest ASIRs were Thailand, the Republic of Korea, and Japan. Thailand had an ASIR of 24.18 (95% UI, 17.89 to 32.01), the Republic of Korea had an ASIR of 22.80 (95% UI, 18.72 to 27.32), and Japan had an ASIR of 12.71 (95% UI, 10.51 to 14.98) (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 2). The trend in ASDR is outlined in Supplementary Table 3.

Figure 3.

The 2019 age-standardized incidence rates of primary liver cancer for each country in the Asia–Pacific region.

Burden of primary liver cancer in young adults in the Asia–Pacific region

The number of primary liver cancer-related incidences, deaths, and DALYs in patients aged 15–49 years were estimated to be 60,800 cases, 46,800 deaths, and 2.23 million DALYs, respectively (Supplementary Tables 4, 5 and 6). From 2010 to 2019, Southeast Asia recorded a decrease in ASIR (APC: −0.70%, 95% CI −0.84 to −0.56%), ASDR (APC: −0.91%, 95% CI −1.37 to −0.44%), and ASDALYs (APC: −0.90%, 95% CI −1.36 to −0.45%). Conversely, the Western Pacific region experienced an increase in ASIR (APC: 1.69%, 95% CI 1.55 to 1.83%), ASDR (APC: 1.36%, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.86%), and ASDALYs (APC: 1.31%, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.83%) (Supplementary Tables 4, 5 and 6).

Discussion

In this study, which was conducted using data from the GBD 2019 dataset, we analyzed the epidemiology of primary liver cancer in the Asia–Pacific region from 2010 to 2019. The results highlighted the substantial burden of primary liver cancer and the temporal changes in its epidemiology in the Asia–Pacific region over the past decade. In 2019, over 350,000 new primary liver cancer cases and 300,000 related deaths were recorded in the Asia–Pacific region, representing 68% and 67% of the global estimates, respectively26. Notably, early-onset primary liver cancer accounted for 17% of the total incident cases and 14% of the deaths from primary liver cancer in the general population. This finding underscores the significant impact of primary liver cancer on young adults. Moreover, this study identified notable trends in the incidence of primary liver cancer in the Asia–Pacific region. The results revealed a decrease in the incidence of primary liver cancer from most etiologies and an increase in the incidence rates of primary liver cancer caused by SLD.

The present study indicated decreasing trends in the incidence rates of primary liver cancer, a finding that is consistent with those observed in the global population in the GBD 2019 study18,27. Notably, the reduction in mortality can be partly attributed to enhanced management of viral hepatitis. This includes measures such as the use of antiviral agents, such as nucleos(t)ide analogues for chronic hepatitis B and novel treatments for chronic hepatitis C infection28–30. Given that HBV vaccination was introduced in 1992, subsequent GBD study cycles are expected to show a decline in the incidence rates of HBV, reflecting the long-term success of vaccination programs31,32.

The present study revealed that although the incidence rates of primary liver cancer of most etiologies are decreasing, those of primary liver cancer caused by SLD, including both ALD and MASLD, are increasing. This finding aligns with current global trends. The increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome, alcohol consumption, and SLD may be attributed to the widespread consumption of westernized diets in many countries across the globe10,33–36. Health alliances designed to tackle the rising wave of SLD in the Asia–Pacific region, which comprises more than half of the global population, are urgently needed at global, regional, and national levels. As public policies play a vital role in increasing or reducing the burden of SLD, strategies for reducing the incidence of SLD need to be implemented37–40. However, while focusing on SLD policies, it is essential not to overlook viral hepatitis, which remained a significant contributor to the total burden in this region as of 2019. Efforts towards viral elimination must be continued and expanded. Despite the high and rising burden, gaps in care remain in the management of patients with MASLD and ALD41,42. Early detection in high-risk patients, such as those with cirrhosis, using non-invasive tests is warranted43,44.

Another important finding of the present study is the divergent trends in the incidence rate of primary liver cancer among young adults, increasing in the Western Pacific region and decreasing in Southeast Asia. The possible explanation for this could be the underreporting of data in the Southeast Asia region, which has lower data rating quality compared to the Western Pacific region. Interestingly, primary liver cancer in young adults accounted for 17% of all primary liver cancer cases recorded in the Asia–Pacific region, nearly three times higher than the proportions recorded in Europe and the Americas18,45. The exact reasons for this higher proportion are unknown, but it could be influenced by different population structures between the two regions46.

It is important to note that primary liver cancer in young adults, particularly in Asian populations, is relatively understudied compared to other early-onset gastrointestinal cancers47–49. This demographic faces social and financial challenges that hinder accessibility to appropriate care and timely diagnosis50. Preventative approaches such as reducing alcohol consumption, managing metabolic comorbidities, and implementing vaccination strategies could mitigate the increasing burden of primary liver cancer in this demographic51–54. The results of the present study emphasize the importance of understanding the unique characteristics of primary liver cancer in young adults and highlight the need for targeted interventions tailored to this group55.

This study has a few limitations. First, it underscores the challenges associated with the availability and reliability of primary data, which are mainly influenced by the vital registration systems used in individual countries. Discrepancies in data quality across regions may impact the overall findings. Second, the estimation methodology employed in the GBD study may lead to an underrepresentation of the mortality rate of primary liver cancer, particularly that caused by MASLD, in low-income countries where advanced diagnostic techniques may be lacking. Additionally, religious prohibitions against alcohol in some countries may lead to underreporting of ALD data, potentially underestimating the true burden of primary liver cancer in these areas50. Furthermore, the incidence of primary liver cancer in areas with limited healthcare accessibility and health awareness may be underreported, contributing to a potential underestimation of the disease burden.

The GBD approach, which attributes primary liver cancer to single disease factors, may overlook complex causes such as mixed etiologies, as seen in cases of MASLD with chronic alcohol intake, recently defined as MASLD with increased alcohol intake (MetALD), concomitant with other chronic liver diseases. This limitation could potentially impact the accuracy of estimates51,52. Efforts to enhance data collection methods to capture detailed information on multiple etiologies for each primary liver cancer case could help mitigate this limitation. This may include the use of more comprehensive patient registries that can record multiple contributing factors. Employing statistical models that account for multiple etiologies and their interactions could provide a more accurate estimation of the disease burden53. Furthermore, the GBD 2019 study lacks detailed data on the different histological subtypes of primary liver cancer, such as hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, hepatoblastoma, and angiosarcoma54. Given that each subtype has distinct characteristics and corresponding clinical outcomes, the absence of detailed data for each subtype limits our comprehensive understanding of the global burden of each primary liver cancer subtype17.

Additionally, the GBD database categorizes the remaining etiologies of primary liver cancer into broader liver disease groups, which include conditions such as autoimmune diseases, hemochromatosis, and aflatoxin exposure. Further research on these specific categories of primary liver cancer could provide valuable insights that will inform public health strategies aimed at addressing the diverse spectrum of liver diseases.

In summary, this study highlights the declining burden of overall primary liver cancer in the general population and the declining trend of primary liver cancer in young adults. However, an uptrend was observed in incidence rates from SLD in both regions and from HBV in the Western Pacific region. These results emphasize the critical need for the development and implementation of effective interventions for tackling the escalating burden of primary liver cancer. A comprehensive approach, which includes the mitigation of risk factors such as alcohol consumption and metabolic syndrome, as well as the widely tailored implementation of interventions for viral hepatitis, including vaccination and the use of antiviral agents, is vital.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The world maps presented in the figures were created using mapchart.net.

Abbreviations

- ALD

Alcohol-associated liver disease

- APC

Annual percentage change

- ASDALYs

Age-standardized disability-adjusted life years

- ASDR

Age-standardized death rate

- ASIR

Age-standardized incidence rate

- ASR

Age-standardized rate

- CI

Confidence interval

- DALYs

Disability-adjusted life years

- GBD

Global burden of disease

- GHDx

GlobalHealth data exchange

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- HCV

Hepatitis C virus

- HDI

United Nations human development index

- MASLD

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease

- MetALD

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease with increased alcohol intake

- NAFLD

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- SLD

Steatotic liver disease

- UI

Uncertainty interval

- WHO

World health organization

Author contributions

Conceptualization—P.D., A.K., K.W. Data curation—P.D., B.S., S.S. Formal analysis—P.D., N.P. Funding acquisition—A.K. Investigation—P.D., Y.P. Methodology—P.D., Y.P. Project Administration—P.D., A.K. Supervision—S.L., T.P., A.K. Validation—P.T., B.S., C.K. Visualization—P.D., B.S. Writing, original draft—P.D., K.S., P.T., C.K., S.S., M.K. Writing, review, and editing—P.D., K.W., P.S., N.C., M.H.N., S.L., T.P., A.K.

Funding

This study was supported by the Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University, Thailand.

Data availability

Data from the 2019 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study can be accessed using the GlobalHealth Data Exchange (GHDx) query tool (http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool), which is maintained by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation.

Competing interests

Teerha Piratvisuth received research grants from Gilead Sciences, Roche Diagnostics, Janssen, Fibrogen, and VIR and honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Bayer, Abbott, Esai, Mylan, Ferring, and MSD. Mindie H. Nguyen received research support from Pfizer, Enanta, Astra Zeneca, GSK, Delfi, Innogen, Exact Science, CurveBio, Gilead, Vir Biotech, Helio Health, National Cancer Institute, Glycotest, National Health Institute and is a consultant and/or advisory board of GSK, Gilead, and Exelixis. Dr. Liangpunsakul discloses consulting roles with Durect Corporation, Surrozen, and Korro Bio. However, these roles do not present any conflict of interest concerning the content of this work. Apichat Kaewdech received research grants or support from Roche, Roche Diagnostics, and Abbott Laboratories, and honoraria from Roche, Roche Diagnostics, Abbott Laboratories, and Esai. The other authors have no relevant conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Pojsakorn Danpanichkul and Kanokphong Suparan.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-70526-z.

References

- 1.Llovet, J. M. et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers.7(1), 6 (2021). 10.1038/s41572-020-00240-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buettner, S., van Vugt, J. L., IJzermans, J. N. & Groot Koerkamp, B. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: current perspectives. Onco Targets Ther.10, 1131–42 (2017). 10.2147/OTT.S93629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altekruse, S. F., Devesa, S. S., Dickie, L. A., McGlynn, K. A. & Kleiner, D. E. Histological classification of liver and intrahepatic bile duct cancers in SEER registries. J. Regist. Manag.38(4), 201–205 (2011). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rumgay, H. et al. Global burden of primary liver cancer in 2020 and predictions to 2040. J. Hepatol.77(6), 1598–1606 (2022). 10.1016/j.jhep.2022.08.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGlynn, K. A., Petrick, J. L. & El-Serag, H. B. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology.73(Supp 1), 4–13 (2021). 10.1002/hep.31288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Konyn, P., Ahmed, A. & Kim, D. Current epidemiology in hepatocellular carcinoma. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.15(11), 1295–1307 (2021). 10.1080/17474124.2021.1991792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asia-Pacific Population and Development Report 2023. Bangkok: Social Development Division, Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP), United Nations (2023).

- 8.Danpanichkul, P. et al. Global and regional burden of alcohol-associated liver disease and alcohol use disorder in the elderly. JHEP Rep.6(4), 101020 (2024). 10.1016/j.jhepr.2024.101020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Danpanichkul, P. et al. The surreptitious burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the elderly in the asia-pacific region: An insight from the global burden of disease study 2019. J. Clin. Med.12(20), 6456 (2023). 10.3390/jcm12206456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danpanichkul, P. et al. The silent burden of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in the elderly: A global burden of disease analysis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther.58(10), 1062–1074 (2023). 10.1111/apt.17714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Danpanichkul, P. et al. Global and regional burden of alcohol-associated liver disease and alcohol use disorder in the elderly. JHEP Rep.6(4), 101020 (2024). 10.1016/j.jhepr.2024.101020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitiyakara, T. et al. Regional differences in admissions and treatment outcomes for hepatocellular carcinoma patients in Thailand. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev.23(11), 3701–3715 (2022). 10.31557/APJCP.2022.23.11.3701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng, R. et al. Liver cancer incidence and mortality in China: Temporal trends and projections to 2030. Chin. J. Cancer Res.30(6), 571–579 (2018). 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2018.06.01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collaborators, G. B. D. H. B. Global, regional, and national burden of hepatitis B, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol.7(9), 796–829 (2022). 10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00124-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collaborators, G. B. D. R. F. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet.396(10258), 1223–49 (2020). 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30752-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu, Y. et al. Global burden of primary liver cancer by five etiologies and global prediction by 2035 based on global burden of disease study 2019. Cancer Med.11(5), 1310–1323 (2022). 10.1002/cam4.4551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diseases, G. B. D. & Injuries, C. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet.396(10258), 1204–1222 (2020). 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang, D. Q. et al. Changing global epidemiology of liver cancer from 2010 to 2019: NASH is the fastest growing cause of liver cancer. Cell Metab.34(7), 969–77.e2 (2022). 10.1016/j.cmet.2022.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song, S. J., Lai, J. C., Wong, G. L., Wong, V. W. & Yip, T. C. Can we use old NAFLD data under the new MASLD definition?. J. Hepatol.80(2), e54–e56 (2024). 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Younossi, Z. M. et al. Clinical profiles and mortality rates are similar for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol.80(5), 694–701 (2024). 10.1016/j.jhep.2024.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suzuki, H., Tsutsumi, T., Kawaguchi, M., Amano, K., Kawaguchi, T. Changing from NAFLD to MASLD: Prevalence and progression of ASCVD risk are similar between NAFLD and MASLD in Asia. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Danpanichkul, P. et al. The global burden of early-onset biliary tract cancer: Insight from the global burden of disease study 2019. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol.14(2), 101320 (2024). 10.1016/j.jceh.2023.101320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Danpanichkul, P. et al. Rising incidence and impact of early-onset colorectal cancer in the Asia-Pacific with higher mortality in females from Southeast Asia: A global burden analysis from 2010 to 2019. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.38(12), 2053–2060 (2023). 10.1111/jgh.16331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Danpanichkul, P., Ng, C. H., Hao Tan, D. J., Wijarnpreecha, K., Huang, D. Q., Noureddin, M., et al. The global burden of alcohol-associated cirrhosis and cancer in young and middle-aged adults. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.LaPelusa, M., Shen, C., Arhin, N. D., Cardin, D., Tan, M., Idrees, K., et al. Trends in the incidence and treatment of early-onset pancreatic Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 14(2) (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Cao, G., Liu, J. & Liu, M. Global, regional, and national trends in incidence and mortality of primary liver cancer and its underlying etiologies from 1990 to 2019: Results from the global burden of disease study 2019. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health.13(2), 344–360 (2023). 10.1007/s44197-023-00109-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karim, M. A. et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-associated hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Cli. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.21(3), 670-680.e18 (2023). 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trepo, C., Chan, H. L. & Lok, A. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet.384(9959), 2053–2063 (2014). 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60220-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nawaz, A. et al. Therapeutic approaches for chronic hepatitis C: A concise review. Front. Pharmacol.14, 1334160 (2023). 10.3389/fphar.2023.1334160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sripongpun, P. et al. Hepatitis C screening in post-baby boomer generation Americans: one size does not fit all. Mayo Clin. Proc.98(9), 1335–1344 (2023). 10.1016/j.mayocp.2023.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lok, A. S. Progress in hepatitis B: A 30-year journey through three continents. Hepatology.60(1), 4–11 (2014). 10.1002/hep.27120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chamroonkul, N. & Piratvisuth, T. Hepatitis B during pregnancy in endemic areas: Screening, treatment, and prevention of mother-to-child transmission. Paediatr. Drugs.19(3), 173–181 (2017). 10.1007/s40272-017-0229-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarin, S. K. et al. Liver diseases in the Asia-Pacific region: A lancet gastroenterology & hepatology commission. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol.5(2), 167–228 (2020). 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30342-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang, Y. L. et al. Alcohol and alcohol-related harm in China: Policy changes needed. Bull. World Health Organ.91(4), 270–276 (2013). 10.2471/BLT.12.107318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ranasinghe, P., Mathangasinghe, Y., Jayawardena, R., Hills, A. P. & Misra, A. Prevalence and trends of metabolic syndrome among adults in the asia-pacific region: A systematic review. BMC Public Health.17(1), 101 (2017). 10.1186/s12889-017-4041-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Danpanichkul, P. et al. The burden of overweight and obesity-associated gastrointestinal cancers in low and lower-middle-income countries: A global burden of disease 2019 analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol.119(6), 1177–1180 (2024). 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lazarus, J. V. et al. The global NAFLD policy review and preparedness index: Are countries ready to address this silent public health challenge?. J. Hepatol.76(4), 771–780 (2022). 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diaz, L. A. et al. Impact of public health policies on alcohol-associated liver disease in Latin America: An ecological multinational study. Hepatology.74(5), 2478–2490 (2021). 10.1002/hep.32016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diaz, L. A. et al. Association between public health policies on alcohol and worldwide cancer, liver disease and cardiovascular disease outcomes. J. Hepatol.80(3), 409–418 (2024). 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Danpanichkul, P., Duangsonk, K., Diaz, L. A., Arab, J. P., Liangpunsakul, S., Wijarnpreecha, K. Editorial: Sounding the alarm-The rising global burden of adolescent and young adult alcohol-related liver disease. Author's reply. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Zeng, R. W., Ong, C. E. Y., Ong, E. Y. H., Chung, C. H., Lim, W. H., Xiao, J., Danpanichkul, P., Law, J. H., Syn, N., Chee, D., Kow, A. W. C., Lee, S. W, Takahashi, H., Kawaguchi, T., Tamaki, N., Dan, Y. Y, Nakajima, A., Wijarnpreecha, K., Muthiah, M. D, Noureddin, M, Loomba, R., Ioannou, G. N., Tan, D. J. H., Ng, C. H., Huang, D. Q. Global prevalence, clinical characteristics, surveillance, treatment allocation, and outcomes of alcohol-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Tan, D. J. H. et al. Clinical characteristics, surveillance, treatment allocation, and outcomes of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-related hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol.23(4), 521–530 (2022). 10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00078-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Israelsen, M., Rungratanawanich, W., Thiele, M., Liangpunsakul, S. Non-invasive tests for alcohol-associated liver disease. Hepatology. (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Preechathammawong, N., Charoenpitakchai, M., Wongsason, N., Karuehardsuwan, J., Prasoppokakorn, T., Pitisuttithum, P., et al. Development of a diagnostic support system for the fibrosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease using artificial intelligence and deep learning. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Danpanichkul, P., Aboona, M. B., Sukphutanan, B., Kongarin, S., Duangsonk, K., Ng, C. H., et al. Incidence of liver cancer in young adults according to the global burden of disease database 2019. Hepatology. (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Balachandran, A., de Beer, J., James, K. S., van Wissen, L. & Janssen, F. Comparison of population aging in Europe and Asia using a time-consistent and comparative aging measure. J. Aging Health.32(5–6), 340–351 (2020). 10.1177/0898264318824180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu, C. W. & Lui, R. N. Early-onset colorectal cancer: Current insights and future directions. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol.14(1), 230–241 (2022). 10.4251/wjgo.v14.i1.230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Milne, A. N. & Offerhaus, G. J. Early-onset gastric cancer: Learning lessons from the young. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol.2(2), 59–64 (2010). 10.4251/wjgo.v2.i2.59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nguyen, H. T., Zheng, A., Gugel, A. & Kistin, C. J. Asians and Asian subgroups are underrepresented in medical research studies published in high-impact generalist journals. J. Immigr. Minor. Health.23(3), 646–649 (2021). 10.1007/s10903-021-01142-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alhashimi, F. H., Khabour, O. F., Alzoubi, K. H. & Al-Shatnawi, S. F. Attitudes and beliefs related to reporting alcohol consumption in research studies: a case from Jordan. Pragmat. Obs. Res.9, 55–61 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Israelsen, M. et al. Validation of the new nomenclature of steatotic liver disease in patients with a history of excessive alcohol intake: an analysis of data from a prospective cohort study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol.9(3), 218–228 (2024). 10.1016/S2468-1253(23)00443-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Danpanichkul, P., Suparan, K., Kim, D., Wijarnpreecha, K. What is new in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease in lean individuals: From bench to bedside. J. Clin. Med. 13(1) (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Hagstrom, H., Adams, L. A., Allen, A. M., Byrne, C. D., Chang, Y., Duseja, A., et al. The future of international classification of diseases coding in steatotic liver disease: An expert panel Delphi consensus statement. Hepatol. Commun. 8(2) (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Mejia, J. C. & Pasko, J. Primary liver cancers: Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma. Surg. Clin. North Am.100(3), 535–549 (2020). 10.1016/j.suc.2020.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Danpanichkul, P. et al. Global epidemiology of alcohol-associated liver disease in adolescents and young adults. Aliment Pharmacol. Ther.60(3), 378–388. 10.1111/apt.18101 (2024). 10.1111/apt.18101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data from the 2019 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study can be accessed using the GlobalHealth Data Exchange (GHDx) query tool (http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool), which is maintained by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation.