Abstract

We present four open-source datasets that provide results of density functional theory (DFT) calculations of ground-state properties of refractory solid solution binary alloys niobium-tantalum (NbTa), niobium-vanadium (NbV), tantalum-vanadium (TaV), and ternary alloys NbTaV ordered in body-centered-cubic (BCC) structures with 128 Bravais lattice sites. The first-principles code used to run the calculations is the Vienna Ab-Initio Simulation Package. The calculations have been collected by uniformly sampling chemical compositions across the entire compositional range. For each chemical composition, the calculations have been run for 100 randomized arrangements of the constituents on the BCC lattice sites. This sampling methodology resulted in running DFT simulations for a total of 3,100 randomized atomic configurations over 31 chemical compositions for each of the three binary alloys Nb-Ta, Nb-V, Ta-V, and a total of 10,500 randomized atomic structures over 105 chemical compositions for the ternary alloys Nb-Ta-V. For each atomic configuration, geometry optimization has been performed, and the data released contains information about each step of geometry optimization for each atomic configuration.

Subject terms: Electronic properties and materials, Structure of solids and liquids

Background & Summary

In multiple principal element alloys (also called high entropy alloys, HEAs) systems, the Gibbs energy functions of the predominant solid solution phases often display multiple local minimums (saddle points), which create ample opportunities to form immiscibility gaps in these systems for phase decomposition1–4. The natural way for developing new alloys is to search for uniform solid solutions. However, the presence of nanoscale size non-homogeneities often improves alloy properties5. The phase decomposition has an important role in forming heterogeneous nanoscale domains in microstructure, from which numerous interfaces between different nanodomains can be created and serve as barriers for dislocation movement, thereby improving strength for a wide range of temperatures. Recently, this strategy has been successful to develop radiation resistant alloys6.

The higher the decomposition temperature of the material, the more likely it can achieve high strength at higher temperature. Considerable research has been performed on the face-centered-cubic (FCC), equiatomic, quinary HEA chrome-manganese-iron-cobalt-nickel (CrMnFeCoNi) and its derivatives7 and interesting mechanical properties have been reported8. In contrast, fewer results have been reported for body-centered-cubic (BCC) HEAs, especially those containing refractory elements. Among the refractory HEAs (RHEAs), two equiatomic quinaries stand out as model systems for investigation because they can be synthesized as single-phase solid solutions: vanadium-niobium-molybdenum-tantalum-tungsten (VNbMoTaW)9 and titanium-zirconium-hafnium-niobium-tantalum (TiZrHfNbTa)10,11. These RHEAs and their derivatives have been proposed as potential high-temperature materials due to the expectation that their high melting points will result in high strengths at elevated temperatures. Indeed, compression tests to 1200 °C12 have confirmed that the yield strength of the VNbMoTaW RHEA is superior to that of Inconel 718 above 800 °C. RHEAs such as VNbMoTaW and TiZrNbHfTa, with estimated melting temperatures (Tm) of 2700 °C (rule of mixtures) and 2000 °C (CALPHAD calculation), respectively, are being explored. However, the phase stability and phase separation in RHEAs is historically difficult to study because of the limitation of experimental capability at high temperatures and sluggish decomposition kinetics to reach equilibrium at low temperatures. For example, investigations into the phase stability of the Ti-Zr-Hf-Nb-Ta system have shown that TiZrNbHfTa has a single-phase BCC structure after 2 hours at 1000 °C and 3 hours at 1200 °C, but transformed into a BCC1+BCC2 structure with ZrHf-enriched and NbTa-enriched phases after 2 hours at 800 °C13,14. However, additional work on TiZrNbHfTa by Schuh et al., showed that after high-pressure torsion (HPT) at room temperature, the alloy consisted of a single BCC phase and subsequent annealing for 1 hour at 300 °C did not produce a phase transformation15. The phase separation at high temperature does not seem consistent with the single phase observed at low temperature.

Accurate prediction of formation energy for RHEAs using computational methods is of critical importance to accurately calculate the phase separation and microstructure evolution. This effort requires: (1) studying a crystal structure with a sufficiently large number of atoms to capture the effect of the configurational entropy, (2) reduce the boundary effect on the prediction of the formation energy, and (3) include effect of temperature. State of the-art density functional theory16 (DFT) based approaches used to compute the formation energy on large crystal structures are very expensive and typically only focus on static crystal structures at 0 Kelvin. This makes questionable the use of DFT based approaches to compute the formation energy for several atomic configurations that span multiple chemical compositions for several temperature. Additionally, the material space described by all the possible chemical composition and atomic disorders for the crystal structure of the high entropy alloy is high dimensional. The dimensionality of the material space increases exponentially with the number of pure elements mixed and the number of atoms in the crystal structure. Computation of ground-state structures of a binary alloy requires calculating the total energy for all possible configurations of placing atoms A and B on N sites of the underlying Bravais lattice. As the number of possible configurations 2N is extremely high, even for relatively low values of N, it is computationally unfeasible to calculate the energy quantum mechanically for an exhaustive set of configurations even using state-of-the-art leadership class supercomputing facilities.

Present limitations of large-scale computational approaches are shedding new light on the potential benefit of integrating machine learning (ML) within traditional material science and quantum mechanics17. In particular, deep learning (DL) models have shown the ability to effectively capture relevant non-linearities triggered by the atomic configurations of an atomic system18–27. Once trained, the trained DL model can be used for inference in a fraction of the time it would take to run a full DFT calculation, while still producing accurate results. This drastic reduction of time to predict properties of alloys using atomic information opens a promising path towards an effective acceleration of discovery and design of new multi-component alloys. The amount of data required to train DL models for the study of HEAs depends on the dimensionality of the chemical space to explore, the complexity of the DL architecture used, and the availability and quality of the data. In general, DL models benefit from large amounts of diverse and high-fidelity data. However, collecting such large amounts of high-fidelity data is challenging for HEAs. In particular, the design of HEAs often involves exploring a vast compositional space28, which means that obtaining a comprehensive dataset covering the entire space is only possible by accessing and leveraging leadership class supercomputing facilities.

We present four new datasets that provide results of DFT calculations at 0 Kelvin for BCC structures with 128 Bravais lattice sites of solid solution binary alloys NbTa29, NbV30, TaV31, and solid solution ternary alloys NbTaV32. The first-principle code used to run the calculations is the Vienna Ab-Initio Simulation Package (VASP)33–37. We carried out VASP calculations utilizing two DOE supercomputers: OLCF-Summit at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) and NERSC-Perlmutter at the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC). The versions of the VASP software used are the version 6.3.2 on Summit and 6.2.1 on Perlmutter, both of which enable hardware acceleration on NVIDIA graphic processing units (GPUs). The calculations have been collected by uniformly sampling chemical compositions across the entire compositional range of the multi-component systems. The chemical compositions have been sampled starting from a pure metal and by progressively increasing the number of atoms of the other constituent by 4 for the binary alloys, and by progressively increasing the number of atoms of the other constituents by 8 for the ternary alloys. For each chemical composition of binaries and ternaries, 100 randomized atomic arrangements of the constituents on the BCC lattice sites have been sampled. The DFT simulations have been run for a total of 3,100 randomized atomic configurations over 31 chemical compositions for each of the three binary alloys NbTa, NbV, TaV, and for a total of 10,500 randomized atomic configurations over 105 chemical compositions for the ternary alloys NbTaV. Starting from an ideal BCC structure, geometry optimization has been performed on each atomic configuration until the geometry has been fully relaxed. This dataset will serve as starting point to compute the phonon contribution to the energy of the multi-component system NbTaV by taking the fully relaxed geometry for each atomic configuration and displacing the atoms from their position of equilibrium. In addition, using information from each step of geometry optimization from the output of the VASP calculations, this dataset also provides informative material to develop ML force fields. The four datasets for binary systems NbTa, NbV, TaV, and for the ternary systems NbTaV have been released open-source29–32.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section “Methods” describes the input parameters used to run the VASP calculations. Section “Procedures for Data Generation” describes the process to generate the randomized atomic configurations and submit the calculations in batches to the job scheduler of the supercomputers for execution. Section “Technical Validation” comments on the results obtained from out calculations with respect to previous work performed on the same system with only 12 atoms in the BCC structure, as well as preliminary experimental low temperature observations provided by our experimental collaborators. Section “Usage Note” provides instructions on how to access and download the data. Section “Code Availability” provides details on the open-source repository with the python scripts that we used to generate the randomized atomic configurations and the bash script that we used for job scheduling to submit the calculations to the supercomputers.

Methods

The electronic structures of alloys have been calculated using Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)33–37. Within this package the density functional theory (DFT)16 approach is used to describe the electron-electron interactions. This allows the reduction of the many-body Schrödinger equation to a set of single particle Kohn-Sham (KS) equations38. The many particle electron interaction in DFT is captured by an universal exchange-correlation functional for which a wide choice of approximations have been proposed. In the present calculations, we employ the generalized gradient approximation within the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof39 parametrization. The electron-ion interactions are described by pseudopotentials (PPs) using the plane-wave basis projector augmented-wave (PAW) approach40. The PPs used in our calculations are the set provided with the respective VASP distributions. We chose PPs treating s and p semi-core states as valence states in the cases of V, Nb, and p semi-core states as valence states in case of Ta. These are the VASP-developer-recommended potentials for DFT calculations, as outlined in https://www.vasp.at/wiki/index.php/Available_PAW_potentials#Recommended_potentials_for_DFT_calculations. The electronic densities and potentials are expanded in plane-waves with an energy cutoff of 350 eV. A 2 × 2 × 2 k-mesh and the VASP precision setting “normal” were used. Thus, such chosen mesh and cutoff energy guarantee accuracy of the calculation by dropping the error below 4 meV per atom. Methfessel-Paxton smearing of electronic occupations near the Fermi level were introduced with a broadening of 0.2 eV. The alloys are modeled by supercells containing 128 randomly distributed atoms. In the initial structure, the atoms occupy perfect BCC lattice cites. These initial structures were optimized until an energy change of less than 10−4 eV was achieved and forces acting on the atoms do not exceed 10−2 eV/Å.

Procedures for data generation

Creation of atomic structures and set-up of VASP6 calculations

The Python scripts that we used to generate the VASP6 cases to run are available at the ORNL-GitHub repository https://github.com/ORNL/ScalableWorkflow_VASP_Calculations. The script generate_vasp_atomic_configurations_binary.py was used to generate atomic structures for the solid solution binary alloys Nb-Ta, Nb-V, and Ta-V. The variable atomic_increment was set to 4 atoms to sample 31 chemical compositions evenly distributed across the entire compositional range of the binary alloys. Similarly, the script generate_vasp_atomic_configurations_ternary.py was used to generate atomic structures for the solid solution ternary alloys Nb-Ta-V. The variable atomic_increment was set to 8 atoms to sample 105 chemical compositions evenly distributed across the entire compositional range of the ternary alloys. For the random generation of disordered atomic structures, we fixed the random seed to 42.

Both Python scripts generate a directory for each sampled chemical composition. Within each directory for a chemical composition, multiple sub-directories have been created, one per atomic configuration. For each sub-directory associated with an atomic configuration, a randomized atomic structure that mixes atoms of different constituents is generated by randomly shuffling an initial atomic structure provided in a POSCAR file using the function ‘numpy.random.shuffle()’. Once the execution of these python scripts is completed, each sub-directory associated with an atomic structure contains only the following files needed to start the VASP6 calculations: INCAR, POTCAR, POSCAR, KPOINTS. The file INCAR contains various parameters and settings for controlling the behavior of the electronic structure calculations, the file POTCAR contains information about the pseudopotential, the file POSCAR contains the information about the initial atomic structure before geometry optimization is performed, and the file KPOINTS contains the information about the quadrature points that need to be used for numerical integration in the complex plane.

Scalable scheduling of large ensemble of VASP6 calculations on US-DOE leadership class supercomputers

Our focus is on generating extensive and complete numerical data, aimed at enhancing future scientific research in the field of ML-assisted design of solid solution alloys with desired thermodynamic and mechanical functional properties. Our data collection process has been used to to perform VASP calculations on a total of 19,800 atomic configurations across all binaries and ternaries, collectively amounting to approximately 120,000 compute node hours on OLCF-Summit and 100,000 node hours on NERSC-Perlmutter. For each configuration, we launched concurrent VASP computations using multiple GPUs distributed across multiple nodes on both supercomputing facilities.

A significant challenge we faced was managing a vast quantity of DFT calculations that demands careful monitoring of tasks, identifying and tracking errors, and rerunning them when necessary, which is a tedious but crucial process. Drawing inspiration from the GNU parallel tool41, renowned for its user-friendly approach to executing multiple tasks concurrently, we have developed an in-house tool. This tool is designed for efficient and easy parallel execution and monitoring of multiple jobs. The cornerstone of our algorithm is its ability to maintain a task list in a lightweight database file supporting concurrent access by multiple processes. We employ SQLite3 for its lightweight nature, serverless architecture, cross-platform compatibility, and support with transactions for concurrent access by multiple processes.

By leveraging SQLite3’s lock and unlock capabilities, which guarantee that only one process can modify a database file at a time, we ensure that multiple processes can pick up an unfinished job without causing duplications, while also maintaining records of completed tasks and any error status. This setup allows us to efficiently scale our resources; we can easily allocate more workers when additional compute time is available, or scale down according to the availability of compute nodes. Throughout this process, the global task list and status are maintained seamlessly in a database file, avoiding any conflicts.

Software specification to run VASP6 calculations on OLCF Summit

Part of the calculations were performed on the Summit computer system at the Oak Ridge Leadership computing facility. Summit is an IBM AC922 system which combines IBM Power9 CPUs with NVIDIA V100 GPUs. Table 1 shows the main software components and their versions used for this work that are installed on OLCF-Summit.

Table 1.

Software Specification on OLCF Summit for the VASP6 calculations.

| Software | Description | Version |

|---|---|---|

| VASP-6 | Atomistic first principles package | 6.3.2 |

| ESSL | Numerical library | 6.3.0 |

| FFTW | Numerical fast Fourier transformation library | 3.3.10 |

| Spectrum MPI | MPI implementation | 10.4.0.3 |

| CUDA | NVIDIA GPU Toolkit | 11.0 |

| Python | High-level programming language | 3.9 |

| SQLite | Lightweight database engine | 3.40 |

Software specification to run VASP6 calculations on NERSC Perlmutter

We used the Permultter supercomputer at the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC). Perlmutter is a Cray system which combines AMD Milan CPUs with NVIDIA A100 GPUs. Table 2 shows the software packages utilized in this project, including the primary software components and their respective versions used for this work that are installed on NERSC-Perlmutter.

Table 2.

Software Specification on NERSC-Perlmutter for the Workflow Components.

| Software | Description | Version |

|---|---|---|

| VASP-6 | Atomistic first principles package | 6.2.1 |

| Cray MPICH | MPI implementation | 8.1.25 |

| FFTW | Numerical fast Fourier transformation library | 3.3.10 |

| CUDA | NVIDIA GPU Toolkit | 11.7 |

| Python | High-level programming language | 3.9 |

| SQLite | Lightweight database engine | 3.40 |

Description of the Datasets

The datasets NbTa_BCC_SolidSolution_128atoms_VASP629, NbV_BCC_SolidSolution_128atoms_VASP630, TaV_BCC_SolidSolution_128atoms_VASP631, and NbTaV_BCC_SolidSolution_128atoms_VASP632 contain the input and output files of the VASP calculations for the binary alloys NbTa, NbV, TaV, and the ternary alloys NbTaV, respectively.

Each one of these datasets is structured with three hierarchical levels of directories. The highest level of each dataset is comprised of three folders with the two extreme mono-atomic cases and one folder for the alloy of interest. The directories for the alloys contain a second hierarchical level of sub-directories associated with different chemical compositions, and each sub-directory for a chemical composition contains a third hierarchical level with multiple sub-directories, one per atomic configuration. For the binary alloys, the convention used to name the directories associated with different chemical compositions are AXBY, where A and B refer to the constituents, whereas X and Y are positive integers that represent the number of A-atoms and B-atoms in the atomic structure, respectively. The values of X and Y sum up to 128, which is the total number of sites in the Bravais lattice. Similarly, the convention used to name the directories for ternary alloys is AXBYCZ, where A, B, and C refer to the constituents, and X, Y, and Z are positive integers that represent the number of atoms for each constituent and their values still sum up to 128. Inside each directory associated with a chemical composition, 100 sub-directories are generated using the convention ‘case-N’ to name the directories, where N is a positive integer that spans all the values from 1 through 100, extremes included.

Each subdirectory with name “case-N” contains the following files:

INCAR: input file that contains various parameters and settings for controlling the behavior of the electronic structure calculations

KPOINTS: input file that specifies the Bloch vectors (k points) used to sample the Brillouin zone

0.POSCAR: input file that defines the atomic structure of a system

0.CONTCAR: output file that provides the atomic positions and cell parameters after the first geometry optimization has been run with the precision variable set to “PREC=Low” in the INCAR file

0.OUTCAR: output file that contains detailed information about the progress of a calculation after the first geometry optimization has been run with the precision variable set to “PREC=Low” in the INCAR file

rlx1.out: file with diagnostic information about the execution of the first geometry optimization with precision variable set to “PREC=Low” in the INCAR file

POSCAR: input file that defines the atomic structure of a system after the first geometry optimization has been run at low precision. This represents the input for the second geometry optimization run with the precision variable set to “PREC=Normal” in the INCAR file

CONTCAR: output file that provides the atomic positions and cell parameters after the second geometry optimization has been run with the precision variable set to “PREC=Normal” in the INCAR file

OUTCAR: output file that contains detailed information about the progress of a calculation after the second geometry optimization has been run with the precision variable set to “PREC=Normal” in the INCAR file

rlx2.out: file with diagnostic information about the execution of the second geometry optimization with precision variable set to “PREC=Normal” in the INCAR file

vaspout.h5: hierarchical HDF5 file containing the inputs and outputs of a VASP calculation. To analyze the data in this file we recommend using py4vasp. This file is only produced if the VASP version used is compiled with HDF5 support

vasprun.xml: contains similar information to OUTCAR, but in an xml format.

For more information about the content of the output files we refer the reader to the website https://www.vasp.at/wiki/index.php/Category:Output_files.

Calculation of the formation energy for each atomic configuration

For each atomic configuration, we calculated the formation energy at the ground state (0 Kelvin). At the ground state, the total energy E of an alloy can be written as

| 1 |

where Nelem is the total number of distinct elements in the system, ci is the molar fraction of each element i, Ei is the molar energy of each element i, and ΔEform is the formation energy. We calculated the formation energy for each sample by subtracting the internal energy from the total energy computed with VASP. The histograms of the observed formation energies are shown in Figs. 1 and 2. As calculations are performed for a discrete number of concentrations, for each concentration, the energies of the sampled configurations will be centered around the average formation energy for this concentration. This results in multi-peaked energy histograms in Figs. 1 and 2.

Fig. 1.

Formation energy of solid solution NbTa, NbV, and TaV binary alloys with BCC structure.

Fig. 2.

Distribution values of formation energy for NbTaV alloys.

Correlation between lattice distortion and mechanical strength of solid solution alloys

In a single-phase HEAs, different elemental atoms with different atomic sizes and number of valence electrons are randomly mixed in one crystallographic lattice, which leads to severe lattice distortion in the atomic structures of HEAs42,43. Lattice distortion has been recognized to have a significant role in strength44, phase stability45,46, sluggish diffusion47,48, electrical49,50, and thermal conductivities50 of HEAs. Therefore, in this work, we calculated the root mean-squared displacement (RMSD) for each atomic configuration to obtain quantitative understanding on the lattice distortion.

Calculation of the root mean-squared displacement (RMSD) for each atomic configuration

Let us with the set of coordinates of the atoms’ nuclei on the ideal BCC Bravais lattice, with the deformation tensor computed by the VASP code on each atomic configuration, and with the fully optimized geometry of an atomic configuration. We compute as follows:

| 2 |

where the superscript T denotes the transpose. We denote with the ith row of the tensor Xideal and with the ith row of the tensor Xdeformed, with i being an integer that ranges between 1 and Natoms. The root mean-squared displacement (RMSD) is computed as follows:

| 3 |

where ∥ ⋅ ∥ is the Euclidean norm of a vector.

NbTa_BCC_SolidSolution_128atoms_VASP6 dataset

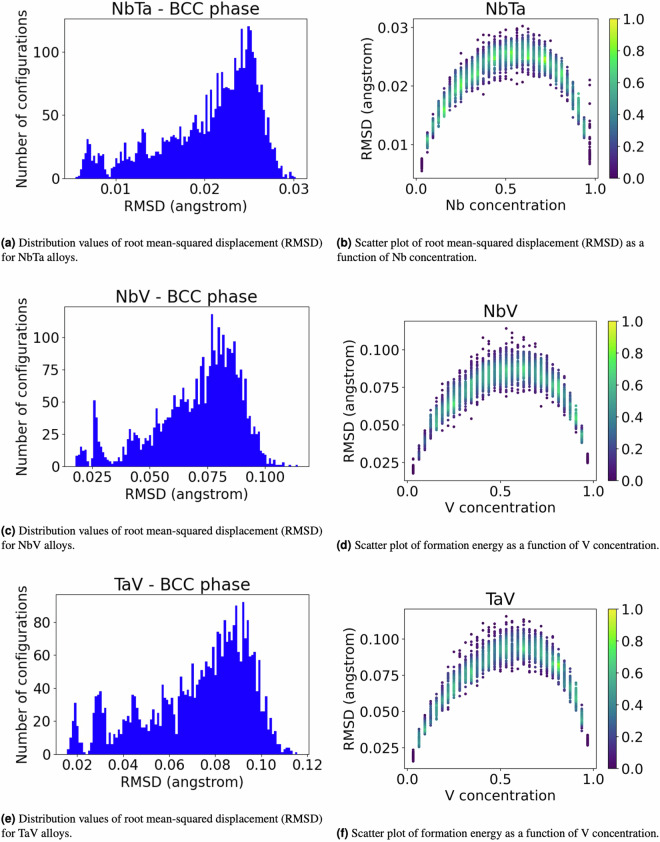

Figure 1(a) illustrates the distribution of the values of the formation energy and Fig. 1(b) illustrates the scatter plot of the formation energy as a function of the Nb concentration for the binary systems NbTa. The convex shape of the scatter plot shows that the BCC solid solution phase favors mixing of the constituents at 0 Kelvin. Figure 6(a) illustrates the distribution of the values of the RMSD and Fig. 6(b) illustrates the scatter plot of the RMSD as a function of the Nb concentration for the binary systems NbTa. Figure 6(b) shows that the maximum RMSD in the binary system NbTa is at approximately at 60 % concentration of Nb.

Fig. 6.

Root mean-squared displacement RMSD of solid solution NbTa, NbV, and TaV binary alloys with BCC structure.

NbV_BCC_SolidSolution_128atoms_VASP6 dataset

The distribution of the values of the formation energy and the scatterplot of the formation energy as a function of the V concentration for the binary systems NbV are shown in Fig. 1(c),(d), respectively. In this case, the scatter plot is concave, thereby indicating a phase separation between the constituents at 0 Kelvin. Figure 6(c) illustrates the distribution of the values of the RMSD and Fig. 6(d) illustrates the scatter plot of the RMSD as a function of the V concentration for the binary systems NbV. Figure 6(d) shows that the maximum RMSD in NbV binary is at approximately 60 % concentration of V. The absolute value is greater than that in the binary system NbTa, suggesting that the random mixing induced lattice distortion between Nb and V greater than the distortion induced in NbTa.

TaV_BCC_SolidSolution_128atoms_VASP6 dataset

Figure 1(e),(f) illustrate the distribution of the values of the formation energy and the scatter plot of the formation energy as a function of the V concentration for the binary systems TaV, respectively. Also for this system, the scatter plot is concave, thereby indicating a phase separation between the constituents at 0 Kelvin. Figure 6(e) illustrates the distribution of the values of the RMSD and Fig. 6(f) illustrates the scatter plot of the RMSD as a function of the V concentration for the binary systems TaV. Figure 6(f) shows that the maximum RMSD in the binary system TaV is at approximately 60 % concentration of V. The absolute value is the greatest among the Nb-Ta, Nb-V and TaV systems, suggesting that the random mixing induced the greatest distortion in the binary system TaV.

NbTaV_BCC_SolidSolution_128atoms_VASP6 dataset

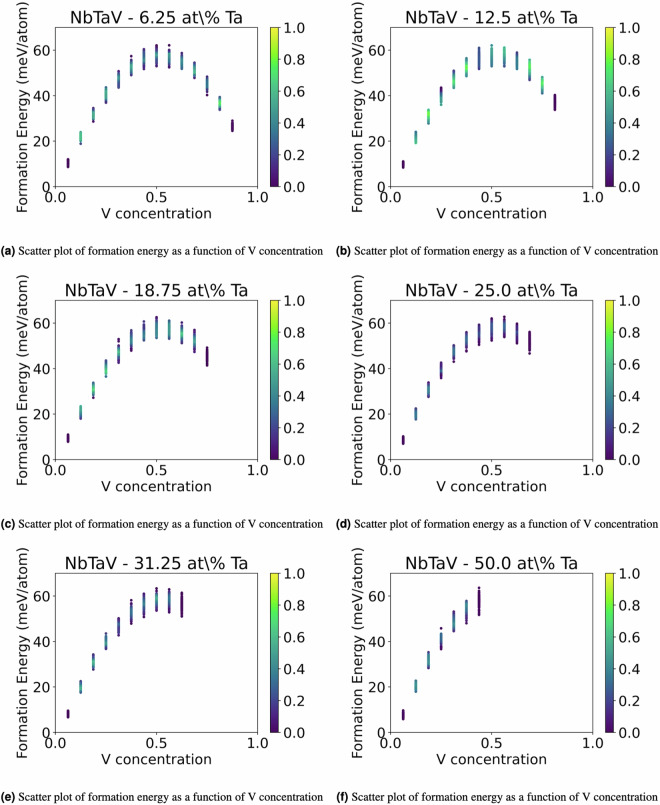

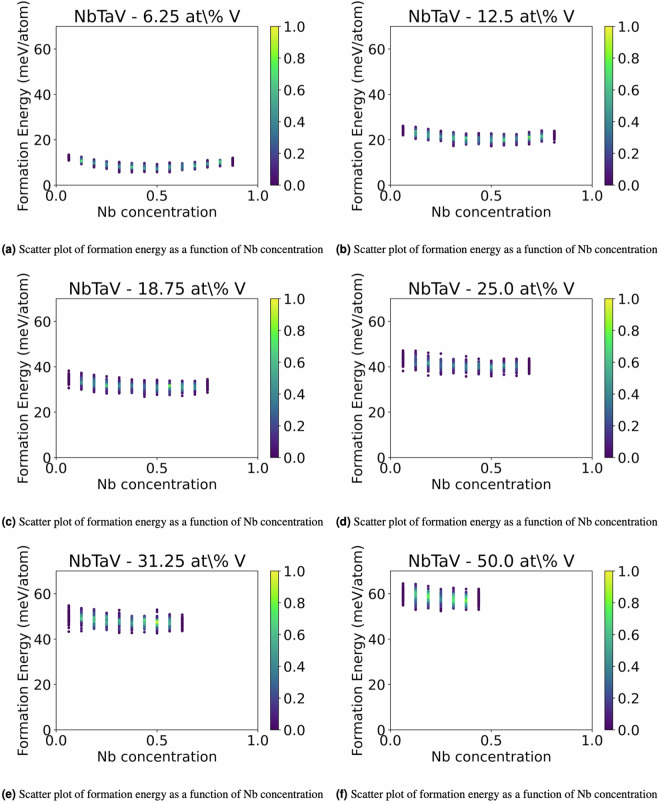

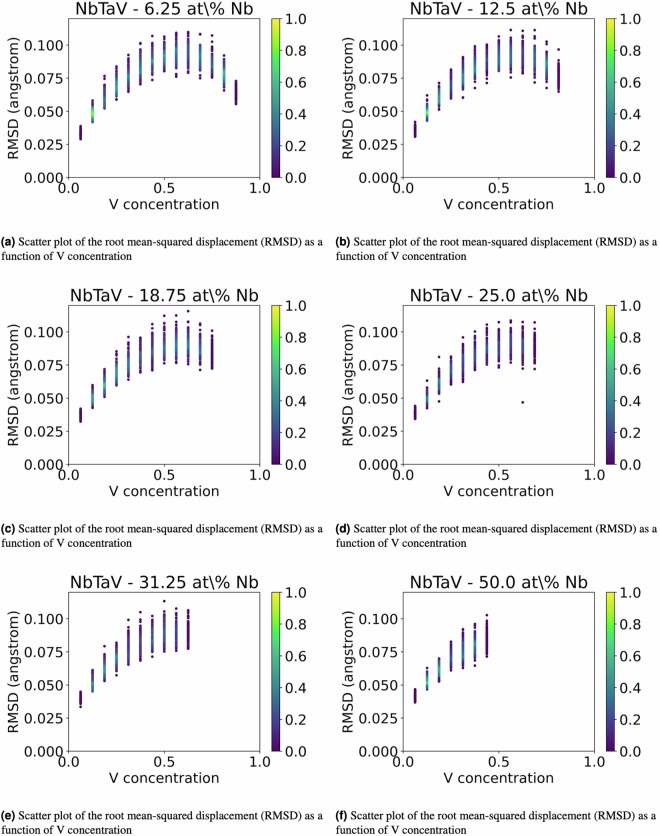

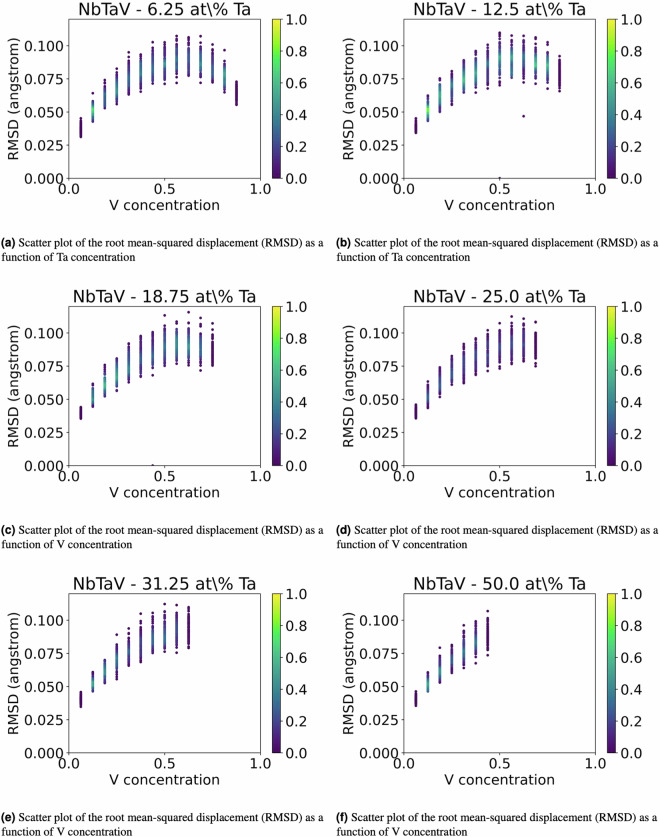

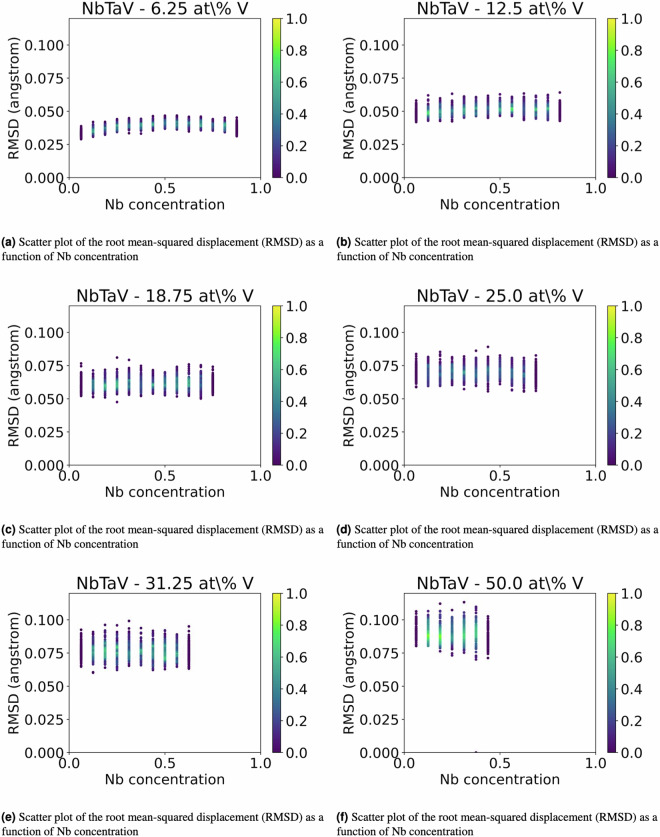

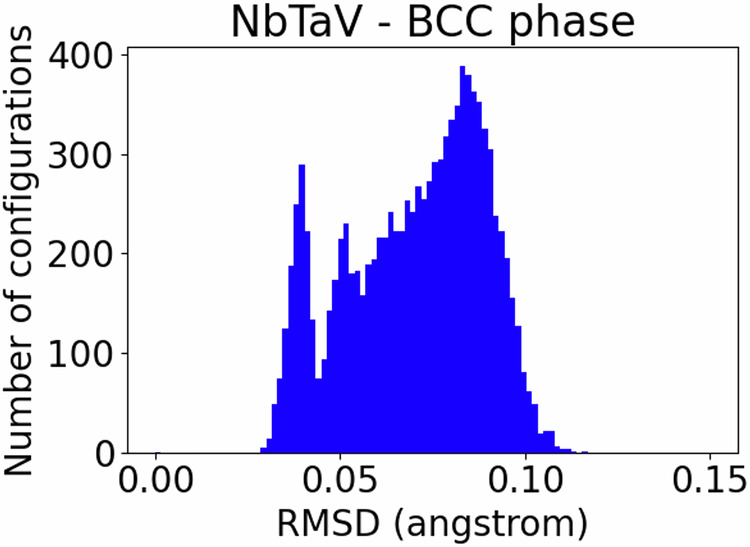

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of the values of the formation energy, whereas Figs. 3, 4, and 5 illustrate scatter plots of the formation energy for the ternary alloys NbTaV at fixed values of concentrations of Nb, Ta, and V, respectively. For low concentrations of Nb, the plots in Fig. 3 have a similar shape to the ones of the binary alloy TaV in Fig. 1(f). Similarly, for low concentrations of Ta, the plots in Fig. 4 are very similar to the ones of the binary alloy NbV in Fig. 1(d). Finally, for low concentrations of V (say 6.25 at% V), the plots in Fig. 5 show a convex shape of the formation energy as a function of the chemical concentration of V, thereby showing a very similar trend to the one of the formation energy for the binary alloy NbTa in Fig. 1(b). These trends are reasonable to expect, because small additions of a third new constituent to a binary alloy are not supposed to abruptly change the trend of the formation energy as a function of the chemical composition. Fig. 7 illustrates the distribution of the values of the RMSD, whereas Figs. 8, 9, and 10 illustrate scatter plots of the RMSD for the ternary alloys NbTaV at fixed values of concentrations of Nb, Ta, and V, respectively. For all sampled concentrations of Nb, the RMSD reaches a maximum for chemical compositions that are rich in V. The magnitude of RMSD does not show strong dependency on Nb concentration. The random mixing between Ta and V induced a RMSD in the ternary that is not significantly different from the one induced in the binary TaV. A similar trend is also observed for the NbV mixing at different concentrations of V. However, for the NbTa mixing, the RMSD significantly increases with the increasing concentrations of V. These results suggest that the mixing of V with the other two elements is the key factor that leads to larger RMSD and, thus, leads to increased strength of the ternary systems NbTaV.

Fig. 3.

2D plots of the formation energy of solid solution NbTaV alloys for fixed values of concentrations of Nb.

Fig. 4.

2D plots of the formation energy of solid solution NbTaV alloys for fixed values of concentrations of Ta.

Fig. 5.

2D plots of the formation energy of solid solution NbTaV alloys for fixed values of concentrations of V.

Fig. 7.

Distribution values of root mean-squared displacement (RMSD) for NbTaV alloys.

Fig. 8.

2D plots of the root mean-squared displacement (RMSD) of solid solution NbTaV alloys for fixed values of concentrations of Nb.

Fig. 9.

2D plots of the root mean-squared displacement (RMSD) of solid solution NbTaV alloys for fixed values of concentrations of Ta.

Fig. 10.

2D plots of the root mean-squared displacement (RMSD) of solid solution NbTaV alloys for fixed values of concentrations of V.

Artefact Description

The datasets NbTa_BCC_SolidSolution_128atoms_VASP6, NbV_BCC_SolidSolution_128atoms_VASP6, and TaV_BCC_SolidSolution_128atoms_VASP6 contain each 31 directories associated with different chemical compositions, and each directory associated with a chemical composition contains 100 sub-directories, one per atomic configuration. This amounts to a total of 3,100 sub-directories. The sub-directories with name “case-N”, where N ranges between 1 and 10 (extremes included) contain all the files listed in Section except vaspout.h5. Sub-directories with name “case-N”, where N ranges between 41 and 60 (extremes included), contain a duplicate copy of the files listed above except for KPOINTS. The names of the duplicate files end with “-bis”, and correspond to a second VASP calculation that has converged to a different optimized geometry. The differences in these duplicate calculations are for calculations performed on the two different computing resources described above including different hardware architectures and compilers. Thus these differences arise from slight numerical differences in the calculations and the difference in the relaxed atomic positions is of the ordered of only 0.01% of the supercell size and the energy difference of the order of a few μeV per atom. The dataset NbTaV_BCC_SolidSolution_128atoms_VASP6 contain 105 directories associated with different chemical composition, and each directory associated with a chemical composition contains 100 sub-directories, one per atomic configuration. This amounts to a total of 10,500 sub-directories.

Data Records

The open-source datasets NbTa_BCC_SolidSolution_128atoms_VASP629, NbV_BCC_SolidSolution_128atoms_VASP630, TaV_BCC_SolidSolution_128atoms_VASP631, and NbTaV_BCC_SolidSolution_128atoms_VASP632 are stored by the OLCF Data Constellation Facility. The datasets can be downloaded using the Globus data transfer service, as indicated by the instructions provided at the following website https://docs.olcf.ornl.gov/data/index.html#data-transferring-data.

Alternatively, the datasets are also available on Figshare and can be downloaded from the following websites:

Technical Validation

Importance of large Bravais lattices to accurately model the configurational entropy in solid solutions

The authors of51 calculated phase diagrams of NbV, TaV, and NbTa alloys by combining the total energies of 40-50 configurations for each system (obtained via DFT calculations run with the VASP software) with the cluster expansion and Monte Carlo techniques. For this study, a BCC supercell with 12 atoms was used for the DFT calculations. Although this study represents a seminal work for solid solution alloys in the Nb-Ta-V chemical space, the size of the BCC supercell used and the total number of atomic configurations considered are not sufficiently large to make meaningful conclusions about the solid solution phases of NbV, TaV, and NbTa alloys. In fact, using a BCC supercell with only 12 atoms and running 40-50 configurations for each system over the entire compositional range does not capture the effect of the configurational entropy on the formation energy of the systems, thereby precluding meaningful conclusions about the stability (or instability) of solid solution phases at certain chemical compositions and temperatures. This is corroborated also by comparing the values of the formation energy at 0 Kelvin obtained from our DFT calculations for solid solution binary systems NbTa, NbV, and TaV in Figure 1 of this manuscript and the DFT values mixed with the cluster expansion (CE) predictions in Figures 7, 9, and 11 of51. Even though we must be mindful in comparing our results that represent only DFT values with the ones displayed in Figures 7, 9, and 11 of51 which mix DFT values with CE predictions, a qualitative comparison shows that the DFT values from our calculations are less scattered and more concentrated around the parabolic curve. This indicates that our calculations better capture the effect of atomic disorder on the stability/instability of the solid solution phase, depending on whether the parabola is convex or concave, whereas the formation energy values in Figures 7, 9, and 11 of51 are dispersed over a broad range of values because BCC structures with only 12 atoms can only describe ordered (e.g., intermetallic) phases.

Usage Notes

The code to prepare the inputs of the VASP calculations and performing post-processing statistical analysis of the dataset is open-source and available at the ORNL-GitHub repository https://github.com/ORNL/ScalableWorkflow_VASP_Calculations. The code contains the following Python script:

generate_vasp_atomic_configurations_binary.py: generates the hierarchy of directories (with one directory per chemical composition and multiple subdirectories names case-N, with N between 1 and 100, for each chemical composition of the binary alloy)

generate_vasp_atomic_configurations_ternary.py: generates the hierarchy of directories (with one directory per chemical composition and multiple subdirectories names case-N, with N between 1 and 100, for each chemical composition of the ternary alloy)

compute_formation_energy.py: computes the formation energy for each fully optimized atomic structure by subtracting the linear term of the total energy

plot_formation_energy_binary.py: plots the histogram for the distribution of values of the formation energy for the binary alloys and generates the scatterplot of the formation energies for each atomic structure as a function of the chemical concentration of one of the two constituents of the binary alloys

plot2D_sliced_formation_energy_ternary_ase_objects: plots the histogram for the distribution of values of the formation energy for the binary alloys and generates the scatterplots of the formation energies for each atomic structure by fixing the chemical concentration of one constituent, and plotting the formation energy values as a function of the chemical concentration of another constituent of the ternary alloys

Acknowledgements

Massimiliano Lupo Pasini thanks Dr. Vladimir Protopopescu for his valuable feedback in the preparation of the manuscript. He also thanks Dr. Stephan Irle for his observation on some of the plots of the formation energy and RMSD. This research is sponsored by the Artificial Intelligence Initiative as part of the Laboratory Directed Research and Development (LDRD) Program of Oak Ridge National Laboratory, managed by UT-Battelle, LLC, for the US Department of Energy under contract DE-AC05-00OR22725. This work used resources of the Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility, which is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC05-00OR22725, under Directorate Discretionary awards MAT025 (Materials Science) and LRN026 (Machine Learning), and INCITE award MAT201. This work also used resources of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, which is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, under award ERCAP0025216.

Author contributions

M.L.P. created the input files for each disordered atomic configuration, curated the dataset once its collection was completed for its public release, analyzed the dataset, and drafted the main portion of the manuscript. G.S. ran the VASP calculations on the NERSC-Perlmutter system for binary solid solution NbTa, NbV, and TaV solid solution alloys with cases 21-40 for each chemical composition, and ran all the cases for the ternary solid solution NbTaV alloys, participated in writing the manuscript. M.E. ran the VASP calculations on the OLCF-Summit system with cases 41-100 for each chemical composition of the binary solid solution Nb-Ta, Nb-V, and Ta-V alloys. J.Y.C. created efficient bash scripts to effectively run large ensembles of VASP calculations on NERSC-Perlmutter and OLCF-Summit, and helped diagnose the runtime errors obtained during the execution of the calculations. J.Y. ran the VASP calculations on the OLCF-Summit system with cases 1-10 for each chemical composition of the binary solid solution NbTa, NbV, and TaV alloys. Y.Y. chose the alloys to study based on her experimental observations obtained through her laboratory experiments and provided meaningful interpretation of the output of the simulations.

Code availability

The code to prepare the inputs of the VASP calculations and performing post-processing statistical analysis of the dataset is open-source and available at the ORNL-GitHub repository https://github.com/ORNL/ScalableWorkflow_VASP_Calculations.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Massimiliano Lupo Pasini, German Samolyuk.

Contributor Information

Massimiliano Lupo Pasini, Email: lupopasinim@ornl.gov.

German Samolyuk, Email: samolyukgd@ornl.gov.

References

- 1.An, Z. et al. Spinodal-modulated solid solution delivers a strong and ductile refractory high-entropy alloy. Mater. Horizons8, 948–955, 10.1039/D0MH01341B (2021). 10.1039/D0MH01341B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li, L. et al. Segregation-driven grain boundary spinodal decomposition as a pathway for phase nucleation in a high-entropy alloy. Acta Materialia178, 1–9, 10.1016/j.actamat.2019.07.052 (2019). 10.1016/j.actamat.2019.07.052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morral, J. E. & Chen, S. Stability of high entropy alloys to spinodal decomposition. J. Phase Equilibria Diffusion42, 673–695, 10.1007/s11669-021-00915-8 (2021). 10.1007/s11669-021-00915-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kadirvel, K., Koneru, S. R. & Wang, Y. Exploration of spinodal decomposition in multi-principal element alloys (mpeas) using calphad modeling. Scripta Materialia214, 114657, 10.1016/j.scriptamat.2022.114657 (2022). 10.1016/j.scriptamat.2022.114657 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang, Y. et al. Bifunctional nanoprecipitates strengthen and ductilize a medium-entropy alloy. Nature595, 245–249 (2021). 10.1038/s41586-021-03607-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El Atwani, O. et al. A quinary wtacrvhf nanocrystalline refractory high-entropy alloy withholding extreme irradiation environments. Nat. Commun.14, 2516 (2023). 10.1038/s41467-023-38000-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Otto, F., Yang, Y., Bei, H. & George, E. Relative effects of enthalpy and entropy on the phase stability of equiatomic high-entropy alloys. Acta Materialia61, 2628–2638, 10.1016/j.actamat.2013.01.042 (2013). 10.1016/j.actamat.2013.01.042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu, Z., Bei, H., Pharr, G. & George, E. Temperature dependence of the mechanical properties of equiatomic solid solution alloys with face-centered cubic crystal structures. Acta Materialia81, 428–441, 10.1016/j.actamat.2014.08.026 (2014). 10.1016/j.actamat.2014.08.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Senkov, O., Wilks, G., Miracle, D., Chuang, C. & Liaw, P. Refractory high-entropy alloys. Intermetallics18, 1758–1765, 10.1016/j.intermet.2010.05.014 (2010). 10.1016/j.intermet.2010.05.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Couzinié, J.-P. et al. On the room temperature deformation mechanisms of a tizrhfnbta refractory high-entropy alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A645, 255–263, 10.1016/j.msea.2015.08.024 (2015). 10.1016/j.msea.2015.08.024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gadelmeier, C., Yang, Y., Glatzel, U. & George, E. P. Creep strength of refractory high-entropy alloy tizrhfnbta and comparison with ni-base superalloy cmsx-4. Cell Reports Phys. Sci.3, 100991, 10.1016/j.xcrp.2022.100991 (2022). 10.1016/j.xcrp.2022.100991 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xin, S. et al. Bulk nanocrystalline boron-doped vnbmotaw high entropy alloys with ultrahigh strength, hardness, and resistivity. J. Alloy. Compd.853, 155995, 10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.155995 (2021). 10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.155995 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soni, V., Senkov, O. N., Gwalani, B., Miracle, D. B. & Banerjee, R. Microstructural design for improving ductility of an initially brittle refractory high entropy alloy. Nat. Sci. Reports8, 8816, 10.1038/s41598-018-27144-3 (2018). 10.1038/s41598-018-27144-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Senkov, O., Scott, J., Senkova, S., Miracle, D. & Woodward, C. Microstructure and room temperature properties of a high-entropy tanbhfzrti alloy. J. Alloy. Compd.509, 6043–6048, 10.1016/j.jallcom.2011.02.171 (2011). 10.1016/j.jallcom.2011.02.171 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schuh, B. et al. Thermodynamic instability of a nanocrystalline, single-phase tizrnbhfta alloy and its impact on the mechanical properties. Acta Materialia142, 201–212, 10.1016/j.actamat.2017.09.035 (2018). 10.1016/j.actamat.2017.09.035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hohenberg, P. & Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. review136, B864 (1964). 10.1103/PhysRev.136.B864 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katiyar, N., Goel, G. & Goel, S. Emergence of machine learning in the development of high entropy alloy and their prospects in advanced engineering applications. Emergent Mater. 4, 10.1007/s42247-021-00249-8 (2021).

- 18.Balabin, R. M. & Lomakina, I. Neural network approach to quantum-chemistry data: Accurate prediction of density functional theory energies. J. Chem. Phys.131, 074104, 10.1063/1.3206326 (2009). 10.1063/1.3206326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chandrasekaran, A. et al. Solving the electronic structure problem with machine learning. NPJ Comput. Mater. 5, 10.1038/s41524-019-0162-7 (2019).

- 20.Brockherde, F., Vogt, L., Tuckerman, M. E., Burke, K. & Müller, K. R. Bypassing the Kohn-Sham equations with machine learning. Nat. Commun. 8, 10.1038/s41467-017-00839-3 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Sinitskiy, A. V. & Pande, V. S. Deep neural network computes electron densities and energies of a large set of organic molecules faster than density functional theory (DFT). https://arxiv.org/abs/1809.02723.

- 22.Custódio, C. A., Filletti, E. R. & ca, V. V. F. Artificial neural networks for density-functional optimizations in fermionic systems. Sci. Rep. 9, 10.1038/s41598-018-37999-1 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Schleder, G. R., Padhila, A. C. M., Acosta, C. M., Costa, M. & Fazzio, A. From DFT to machine learning: recent approaches to materials science–a review. JPhys. Mater. 2, 10.1088/2515-7639/ab084b (2019).

- 24.Vasudevan, R. K. et al. Materials science in the AI age: high-throughput library generation, machine learning and a pathway from correlations to the underpinning physics. MRS Commun. 9, 10.1557/mrc.2019.95 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Maguire, J., Benedict, M., Woodcock, L. & LeClair, S. Artificial intelligence in materials science: Application to molecular and particulate simulations. MRS Commun. 700, 10.1557/PROC-700-S8.1 (2001).

- 26.Wang, C., Tharval, A. & Kitchin, J. R. A density functional theory parameterised neural network model of zirconia. Mol. Simul.44, 623–630, 10.1080/08927022.2017.1420185 (2018). 10.1080/08927022.2017.1420185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lupo Pasini, M. et al. Fast and stable deep-learning predictions of material properties for solid solution alloys. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter33, 084005, 10.1088/1361-648X/abcb10 (2020). 10.1088/1361-648X/abcb10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keil, T., Bruder, E. & Durst, K. Exploring the compositional parameter space of high-entropy alloys using a diffusion couple approach. Mater. & Des.176, 107816, 10.1016/j.matdes.2019.107816 (2019). 10.1016/j.matdes.2019.107816 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lupo Pasini, M. et al. NbTa_BCC_SolidSolution_128atoms_VASP6. OSTI.GOV10.13139/OLCF/2222906 (2023).

- 30.Lupo Pasini, M. et al. NbV_BCC_SolidSolution_128atoms_VASP6. OSTI.GOV10.13139/OLCF/2228839 (2023).

- 31.Lupo Pasini, M. et al. TaV_BCC_SolidSolution_128atoms_VASP6. OSTI.GOV10.13139/OLCF/2222910 (2023).

- 32.Lupo Pasini, M., Samolyuk, G., Eisenbach, M., Choi, J. Y. & Yang, Y. NbTaV_BCC_SolidSolution_128atoms_VASP6. OSTI.GOV10.13139/OLCF/2217644 (2023).

- 33.Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. review B47, 558 (1993). 10.1103/PhysRevB.47.558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal–amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B49, 14251 (1994). 10.1103/PhysRevB.49.14251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. materials science6, 15–50 (1996). 10.1016/0927-0256(96)00008-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. review B54, 11169 (1996). 10.1103/PhysRevB.54.11169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. review b59, 1758 (1999). 10.1103/PhysRevB.59.1758 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kohn, W. & Sham, L. J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. review140, A1133 (1965). 10.1103/PhysRev.140.A1133 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. review letters77, 3865 (1996). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. review B50, 17953 (1994). 10.1103/PhysRevB.50.17953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tange, O. Gnu parallel 20230122 (’bolsonaristas’), GNU Parallel is a general parallelizer to run multiple serial command line programs in parallel without changing them. Zenodo10.5281/zenodo.7558957 (2023). 10.5281/zenodo.7558957 [DOI]

- 42.Yeh, J.-W. et al. Formation of simple crystal structures in Cu-Co-Ni-Cr-Al-Fe-Ti-V alloys with multiprincipal metallic elements. Metall. Mater. Transactions A35, 2533–2536, 10.1007/s11661-006-0234-4 (2004). 10.1007/s11661-006-0234-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yeh, J.-W. Recent progress in high-entropy alloys. Annales De Chimie-science Des Materiaux31, 633–648, 10.3166/ACSM.31.633-648 (2006). 10.3166/ACSM.31.633-648 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rao, S., Woodward, C., Akdim, B., Senkov, O. & Miracle, D. Theory of solid solution strengthening of BCC Chemically Complex Alloys. Acta Materialia209, 116758, 10.1016/j.actamat.2021.116758 (2021). 10.1016/j.actamat.2021.116758 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Samolyuk, G. D., Osetsky, Y. N., Stocks, G. M. & Morris, J. R. Role of static displacements in stabilizing body centered cubic high entropy alloys. Phys. Rev. Lett.126, 025501, 10.1103/PhysRevLett.126.025501 (2021). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.126.025501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ikeda, Y., Gubaev, K., Neugebauer, J., Grabowski, B. & Körmann, F. Chemically induced local lattice distortions versus structural phase transformations in compositionally complex alloys. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 10.1038/s41524-021-00502-y (2021).

- 47.Tsai, K.-Y., Tsai, M.-H. & Yeh, J.-W. Sluggish diffusion in Co–Cr–Fe–Mn–Ni high-entropy alloys. Acta Materialia61, 4887–4897, 10.1016/j.actamat.2013.04.058 (2013). 10.1016/j.actamat.2013.04.058 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang, R. et al. Effect of lattice distortion on the diffusion behavior of high-entropy alloys. J. Alloy. Compd.825, 154099, 10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.154099 (2020). 10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.154099 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mu, S., Wimmer, S., Mankovsky, S., Ebert, H. & Stocks, G. M. Influence of local lattice distortions on electrical transport of refractory high entropy alloys. Scripta Materialia170, 189–194, 10.1016/j.scriptamat.2019.05.032 (2019). 10.1016/j.scriptamat.2019.05.032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang, Y. et al. Influence of chemical disorder on energy dissipation and defect evolution in concentrated solid solution alloys. Nat. Commun.6, 1–9, 10.1038/ncomms9736 (2015). 10.1038/ncomms9736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ravi, C., Panigrahi, B. K., Valsakumar, M. C. & van de Walle, A. First-principles calculation of phase equilibrium of v-nb, v-ta, and nb-ta alloys. Phys. Rev. B85, 054202, 10.1103/PhysRevB.85.054202 (2012). 10.1103/PhysRevB.85.054202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Tange, O. Gnu parallel 20230122 (’bolsonaristas’), GNU Parallel is a general parallelizer to run multiple serial command line programs in parallel without changing them. Zenodo10.5281/zenodo.7558957 (2023). 10.5281/zenodo.7558957 [DOI]

Data Availability Statement

The code to prepare the inputs of the VASP calculations and performing post-processing statistical analysis of the dataset is open-source and available at the ORNL-GitHub repository https://github.com/ORNL/ScalableWorkflow_VASP_Calculations.