Abstract

We herein report radical hydroazidation and hydrohalogenation of mono-, di- and trisubstituted alkenes through iron catalysis. The alkene moiety that often occurs as a functionality in natural products is readily transformed into useful building blocks through this approach. Commercially available tosylates and α-halogenated esters are used as radical trapping reagents in combination with silanes as reductants. The reported radical Markovnikov hydroazidation, hydrobromination, hydrochlorination, and hydroiodination occur under mild conditions. These hydrofunctionalizations are valuable and practical alternatives to ionic hydrohalogenations with the corresponding mineral acids that have to be run under harsher acidic conditions, which diminishes the functional group tolerance. Good to excellent diastereoselectivities can be obtained for the hydrofunctionalization of cyclic alkenes.

Subject terms: Homogeneous catalysis, Synthetic chemistry methodology

Alkenes are attractive building blocks for synthetic organic chemists as they are widely available and can be functionalized in ways that enable manifold further transformations. Here, the authors present a suite of hydrofunctionalizations of alkenes that lead to regioselective delivery of azides and halogens, under mild conditions, with iron catalysis.

Introduction

Radical alkene hydrofunctionalization is generally conducted under mild conditions and various functional groups can be introduced with excellent regioselectivity through such a strategy. Cobalt, manganese, and iron complexes have been used as catalysts along these lines1. In his pioneering work on radical alkene hydration, Mukaiyama applied cobalt catalysis with O2 as an oxygenation reagent2. The Carreira group later developed cobalt-catalyzed alkene hydroazidation and hydrochlorination using tosyl azides and tosyl chlorides as radical traps (Fig. 1A)3–5. Recently, this protocol was further optimized by the Zhu group and applied to the modification of polymers6. Hydrobromination and hydroiodination have been achieved by Herzon and Ma with Co(acac)2 as a stoichiometric mediator and tosyl bromide and diiodomethane as halogen atom transfer reagents7. Very recently, the Ohmiya group published a valuable method for radical alkene hydrohalogenation (F, Cl, Br, and I) using cobalt and iridium dual catalysis8. Through a related approach, Lin et al. achieved photocatalytic Markovnikov hydrofluorination with triethylamine trihydrofluoride as F-source9. It is important to highlight that these radical hydrohalogenations occur under mild non-acidic conditions and as compared to the classical Markovnikov hydrohalogenation with the corresponding mineral acid, functional group tolerance is significantly higher. Moreover, cationic rearrangements that often occur as side reactions in the ionic hydrohalogenation are not a problem using the radical approach.

Fig. 1. Radical hydrofunctionalizations.

A Co-catalyzed alkene hydrofunctionalization. B Hydrofunctionalization of alkenes by using superstoichiometric amounts of an iron salt as a mediator. C Reductive radical alkene/alkene cross-coupling applying Fe-catalysis and suggested mechanism for this radical cascade reaction with an α-ester radical as key intermediate to reoxidize the Fe(II)-complex. Reduction of the Fe(III)OEt with a silane to regenerate the Fe(III)hydride is the rate-determining step. D General reaction scheme of the herein-introduced Fe-catalyzed alkene hydrohalogenation. Design of the radical X-group transfer reagent.

Considering iron-based transformations that are undoubtedly even more attractive, as iron is the most abundant and least toxic metal, current hydrofunctionalization protocols mostly require stoichiometric amounts of iron10–15. For example, the Boger group developed alkene hydrofunctionalizations using superstoichiometric amounts of iron salt (Fig. 1B)12,14. Ishibashi et al. achieved Fe-mediated reductive cyclization of dienes with concomitant bromination or iodination13. These Fe-mediated hydrofunctionalizations proceed through the initial formation of a Fe(III)hydride species by reaction of a Fe(III)X complex with a reductant (borohydride or silane) mostly in the presence of alcohol. After metal-hydride hydrogen atom transfer (MHAT) to the alkene, a carbon-centered radical is formed, which can further react with a radical trapping reagent either through addition to a π-system or halogen abstraction to form the targeted product along with a Fe(II)-complex. To achieve Fe-catalysis, the radical adduct or byproduct formed after trapping must be able to reoxidize the Fe(II)-species. An alternative would be the use of a stoichiometric external oxidant, as realized for Co-systems7,16–18. Oxidation and regeneration of the Fe(III)–H complex (rate determining step) under reducing conditions pose challenges and inefficient oxidation leads to a buildup of inactive Fe(II)-species that eventually stops catalysis. In fact, only a limited number of successful Fe-catalyzed radical hydrofunctionalizations have been reported to date. For example, the Boger group realized alkene hydration with air as the oxidant using Fe-catalysis12. We developed an iron-catalyzed Mukaiyama-type hydration that utilizes nitroarenes as radical traps19,20. Moreover, additional Fe-catalyzed hydrofunctionalizations, like C–C couplings21–23, hydronitrosation24, hydroamination25,26, hydrofluorination27, and hydroalkynylation28 have been reported. Further advancements have recently been made by the groups of Shenvi and Baran, who achieved coupling reactions using catalytic amounts of iron porphyrin complexes29,30. These complexes are able to form an intermediate alkyl iron complex that can engage in coupling reactions with alkyl radicals through homolytic substitution.

The Baran group established Fe-catalyzed reductive cross-coupling of electron-rich alkenes with α,β-unsaturated esters or ketones (Fig. 1C)31. In these couplings, the initial MHAT occurs at the electron-rich alkene, and the H-adduct C-radical further reacts with the Giese-acceptor to give an α-keto or an α-ester C-radical that are both able to reoxidize the Fe(II)-complex. The critical Fe(II)-oxidation step was studied in more detail by the groups of Holland and Poli who suggested that the alcohol is of importance, as oxidation likely proceeds through a concerted proton-coupled electron transfer (CPET) from a Fe(II)/alcohol complex to the C-radical32. In Fe-catalyzed hydrofunctionalizations where catalytic turnover without additional oxidant is achieved, an α-keto or an α-ester C-radical often appear as key intermediates22,26,33,34.

In this work, we present iron-catalyzed radical alkene hydrofunctionalizations, leveraging the oxidative capabilities of α-ester C-radicals to facilitate catalytic turnover of the redox cycle (Fig. 1D). The hydrofunctionalization reagents were designed according to the following criteria. The X-atom transfer reagent used as the radical trap should (a) react efficiently with secondary and tertiary C-radicals, and (b) after successful X-atom transfer generates an α-ester radical that is reducible by a Fe(II)-complex. Based on these requirements, we selected readily available α-halo esters, where depending on the α-substituents, X-atom-transfer to nucleophilic C-radicals are known to be efficient (at least for Br and I)35. To our knowledge, Fe-catalyzed radical Markovnikov hydrohalogenation has not been reported to date.

Results

Hydrobromination and hydroiodination—reaction optimization

We commenced our studies by using the terminal alkene 1a as the model substrate in combination with commercial α-bromoisobutyric ester 2a as the Br-transfer reagent. Pleasingly, with 1.5 equivalents of 2a, Fe(dpm)3 (Hdpm = dipivaloylmethane) as catalyst (10 mol%) in combination with the RubenSilane (PhSiOiPrH2)36 (2 equiv.) in a THF/iPrOH solvent mixture, the targeted secondary bromide 3a was obtained in 85% yield (Table 1, entry 1). Replacing the silane 4 with commercial phenylsilane led to a slight decrease in yield (entry 2). A lower conversion and lower yield were noted with Fe(acac)3 (entry 3) and a further diminished yield was achieved with Fe(acac)3 in combination with phenylsilane as the hydride source (56%, entry 4). However, a better result was noted for the Fe(acac)3/PhSiH3 couple by using methanol as solvent (76%, entry 5). Upon decreasing the amount of phenylsilane (1 equiv.) and prolonging the reaction time to 2 days we could further improve the yield to 84% (entry 6). Increasing the temperature to 40 °C allowed to shorten the reaction time to 24 h accompanied by a slight loss in yield (entry 7). The best result was achieved by decreasing the amount of radical trap to 1.2 equivalents, leading to an excellent 98% yield of 3a (entry 8).

Table 1.

Optimization of the Fe-catalyzed radical Markovnikov hydrobromination and hydroiodination with various X-transfer reagents using alkenes 1a and 1b as model substrates

| Entrya | Fe–H source | Solvent | Radical trap | Conversion | Yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fe(dpm)3, 4 (2.0 eq.) | THF/iPrOH | 2a (1.5 eq.) | 98% (1a) | 85% (3a) |

| 2 | Fe(dpm)3, PhSiH3 (2.0 eq.) | THF/iPrOH | 2a (1.5 eq.) | 99% (1a) | 79% (3a) |

| 3 | Fe(acac)3, 4 (2.0 eq.) | THF/iPrOH | 2a (1.5 eq.) | 90% (1a) | 79% (3a) |

| 4 | Fe(acac)3, PhSiH3 (2.0 eq.) | THF/iPrOH | 2a (1.5 eq.) | 93% (1a) | 56% (3a) |

| 5 | Fe(acac)3, PhSiH3 (2.0 eq.) | MeOH | 2a (1.5 eq.) | 98% (1a) | 76% (3a) |

| 6b | Fe(acac)3, PhSiH3 (1.0 eq.) | MeOH | 2a (1.5 eq.) | 94% (1a) | 84% (3a) |

| 7c | Fe(acac)3, PhSiH3 (1.0 eq.) | MeOH | 2a (1.5 eq.) | 96% (1a) | 81% (3a) |

| 8b | Fe(acac)3, PhSiH3 (1.0 eq.) | MeOH | 2a (1.2 eq.) | 98% (1a) | 98% (3a) |

| 9 | Fe(acac)3, PhSiH3 (1.5 eq.) | MeOH | 2a (1.5 eq.) | 41% (1b) | 9% (3b) |

| 10 | Fe(dpm)3, 4 (2.0 eq.) | THF/iPrOH | 2a (2.0 eq.) | 57% (1b) | 27% (3b) |

| 11b | Fe(dpm)3, 4 (2.0 eq.) | THF/iPrOH | 2a (1.1 eq.) | 89% (1b) | 79% (3b) |

| 12b | Fe(dpm)3, 4 (1.2 eq.) | THF/iPrOH | 2a (1.1 eq.) | 90% (1b) | 81% (3b) |

| 13 | Fe(acac)3, PhSiH3 (2.0 eq.) | MeOH | 2b (3.0 eq.) | 33% (1a) | 12% (5a) |

| 14 | Fe(acac)3, PhSiH3 (2.0 eq.) | MeOH | 2c (3.0 eq.) | n.d. (1a) | 8% (5a) |

| 15 | Fe(dpm)3, 4 (2.0 eq.) | THF/iPrOH | 2d (3.0 eq.) | 49% (1a) | 0% (5a) |

| 16 | Fe(acac)3, PhSiH3 (2.0 eq.) | MeOH | 2e (3.0 eq.) | 33% (1a) | 25% (5a) |

| 17 | Fe(acac)3, PhSiH3 (2.0 eq.) | MeOH | 2f (3.0 eq.) | 0% (1a) | 0% (5a) |

| 18d | Fe(acac)3, PhSiH3 (1.0 eq.) | MeOH | 2e (1.0 eq.) | 87% (1a) | 84% (5a) |

| 19e | Fe(acac)3, PhSiH3 (1.0 eq.) | MeOH | 2e (1.0 eq.) | 81% (1a) | 81% (5a) |

aReactions were carried out on a 0.1 mmol scale. The reactions were stirred until no further conversion was observed by GC analysis. Conversion and yield were determined by GC analysis using dodecane as an internal standard.

bStirred for 48 h at rt.

cReaction run at 40 °C.

dFor 4 days on a 0.5 mmol scale.

eAt 40 °C for 30 h.

Unfortunately, when we applied these optimized conditions to the hydrobromination of the 1,1-disubstituted alkene 1b, which reacts through a tertiary alkyl radical, only a 9% yield of 3b was obtained (entry 9). An improved result was noted for the hydrobromination of 1b upon switching to Fe(dpm)3 as precatalyst in combination with the RubenSilane (2 equiv.) in THF/iPrOH (27%, entry 10). The conversion was further improved by lowering the amount of the trapping reagent 2a (1.1 equiv.) and 3b was formed in 79% yield (entry 11). The best result was achieved by lowering the amount of silane 4 to 1.2 equivalents (81%, entry 12). Continuously extending the reaction time failed to yield improved results. Instead, it resulted in stagnant conversion.

Next, we optimized the hydroiodination of the terminal alkene 1b. With the α-iodoisobutyric ester 2b as the I-transfer reagent (3 equiv.) under the above-optimized hydrobromination conditions, the secondary alkyl iodide 5a was formed in low yield (12%, entry 13). We therefore tested other α-iodo esters as trapping reagents and with the ester 2c yield further decreased to 8% (entry 14). With the α,α-difluoroester 2d as a radical trap, product 5a was not formed (entry 15). Pleasingly, the α-iodopropionic ester 2e gave 5a in an improved yield (25%), but conversion remained low (entry 16) and no reaction was noted with the α-phenyl-α-iodo ester 2f as the radical trap (entry 17). Optimization studies were therefore continued with the most promising reagent 2e. Conversion and yield could be significantly increased by reducing the amounts of phenylsilane and radical trap to just one equivalent each (entry 18). Under these conditions, the reaction took longer and after 4 days, an 89% yield was achieved. Unfortunately, prolonging the reaction time did not result in additional conversion, as the reaction stopped. Upon running the hydroiodination at 40 °C, reaction time could be shortened to 30 h at a slight expense in yield (entry 19). For a full optimization study, please refer to the Supplementary Material. Unfortunately, as tertiary alkyl iodides are not stable under the reaction conditions, hydroiodination of the 1,1-disubstituted alkene 1b was not successful.

Hydrochlorination and hydroazidation—reaction optimization

We next addressed the hydrochlorination of the alkenes 1a and 1b. Encouraged by the successful hydrobromination with 2a, we first selected 2-chloroisobutyricacid methyl ester as the radical chlorination reagent. However, under all tested conditions the Fe-catalyzed radical hydrochlorination failed for these alkenes. This is not unexpected as Cl-atom transfer reactions are several orders of magnitude slower than the corresponding bromine atom transfers37. We, therefore, switched to commercial tosyl chloride as the Cl-donor that was successfully used before in Fe-mediated (superstoichiometric) Markovinkov hydrochlorination reactions12 and also in Co-catalyzed alkene hydrofunctionalizations4. Thus, secondary and tertiary C-radicals are known to react with tosyl chloride and the challenge lay in finding conditions, where the tosylsulfonyl radical generated after Cl-atom transfer efficiently oxidizes the Fe(II)-complex to close the redox cycle.

Initial optimization studies were conducted on the 1,1-disubstituted alkene 1b to give the tertiary chloride 7b (for a full optimization study, please refer to the Supplementary Material). By using Fe(dpm)3 as precatalyst (10 mol%) in combination with the RubenSilane 4 (2.0 equiv.) and 1.5 equivalents of tosyl chloride 6a, the desired hydrofunctionalization product 7b was obtained in 74% yield (Table 2, entry 1). Replacing 4 by phenylsilane afforded a worse result (entry 2) and Fe(acac)3 in combination with 4 provided a significantly diminished yield (entry 3). Increasing the amount of tosyl chloride to 3 equivalents did not affect the reaction outcome (entry 4) and exposing the reaction mixture to air had a detrimental effect on the hydrofunctionalization (entry 5). We then switched to the terminal alkene 1a as the substrate and found that alkyl chloride 7a was formed in 48% yield under the ideal conditions identified for substrate 1b (entry 6). The yield could be improved to 61% by lowering the amount of tosyl chloride to 1.1 equivalents (entry 7). We were pleased to find that increasing the amount of silane (3 equiv.) and extending reaction time (72 h) led to a further improvement of the result and 7a was obtained in 82% yield (entry 8). Notably, similar yields were also achieved with Fe(acac)3 in combination with phenylsilane (4 equiv.). However, the reaction took 8 days to reach high conversion (entry 9). Reaction time could be shortened to 2 days by running the hydrochlorination at 40 °C with little loss in yield (entry 10).

Table 2.

Optimization of the Fe-catalyzed hydrofunctionalization with commercial tosyl chloride and tosyl azide as the atom or group transfer reagents

| Entrya | Fe–H source | Radical trap | Conversion | Yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fe(dpm)3, 4 (2.0 eq.) | 6a (1.5 eq.) | 76% (1b) | 74% (7b) |

| 2 | Fe(dpm)3, PhSiH3 (2.0 eq.) | 6a (1.5 eq.) | 64% (1b) | 62% (7b) |

| 3 | Fe(acac)3, 4 (2.0 eq.) | 6a (1.5 eq.) | 23% (1b) | 23% (7b) |

| 4 | Fe(dpm)3, 4 (2.0 eq.) | 6a (3.0 eq.) | 77% (1b) | 77% (7b) |

| 5b | Fe(dpm)3, 4 (2.0 eq.) | 6a (1.5 eq.) | 57% (1b) | 50% (7b) |

| 6 | Fe(dpm)3, 4 (2.0 eq.) | 6a (1.5 eq.) | 75% (1a) | 48% (7a) |

| 7 | Fe(dpm)3, 4 (2.0 eq.) | 6a (1.1 eq.) | 79% (1a) | 61% (7a) |

| 8c | Fe(dpm)3, 4 (3.0 eq.) | 6a (1.1 eq.) | 90% (1a) | 82% (7a) |

| 9d | Fe(acac)3, PhSiH3 (4.0 eq.) | 6a (1.5 eq.) | 81% (1a) | 80% (7a) |

| 10e | Fe(acac)3, PhSiH3 (4.0 eq.) | 6a (1.5 eq.) | 80% (1a) | 75% (7a) |

| 11 | Fe(dpm)3, 4 (2.0 eq.) | 6b (1.5 eq.) | 76% (1a) | 62% (8a) |

| 12 | Fe(dpm)3, 4 (2.0 eq.) | 6b (1.5 eq.) | 84% (1b) | 71% (8b) |

aReactions were carried out on a 0.1 mmol scale. The reactions were stirred until no further conversion was observed by GC analysis. Conversion and yield were determined by GC analysis using dodecane as an internal standard.

bConnected to air by needle.

cStirred for 72 h.

dStirred for 194 h.

eAt 40 °C for 48 h.

Finally, we also screened conditions for the Fe-catalyzed hydroazidation of the alkenes 1a and 1b with commercial tosyl azide 6b as the group transfer reagent. Of note, Fe-catalyzed hydroazidation is currently unknown to our knowledge. Conditions identified for the hydrochlorination of 1b turned out to be well-suited for the hydroazidation of the two model alkenes. Thus, the reaction of 1a with Fe(dpm)3 and the RubenSilane (2 equiv.) in a THF/iPrOH solvent mixture with tosyl azide 6b (1.5 equiv.) at room temperature for 24 h afforded the alkyl azide 8a in 62% yield (entry 11). Under the same conditions, the alkene 1b was successfully converted to the tertiary azide 8b which was formed in 71% yield (entry 12).

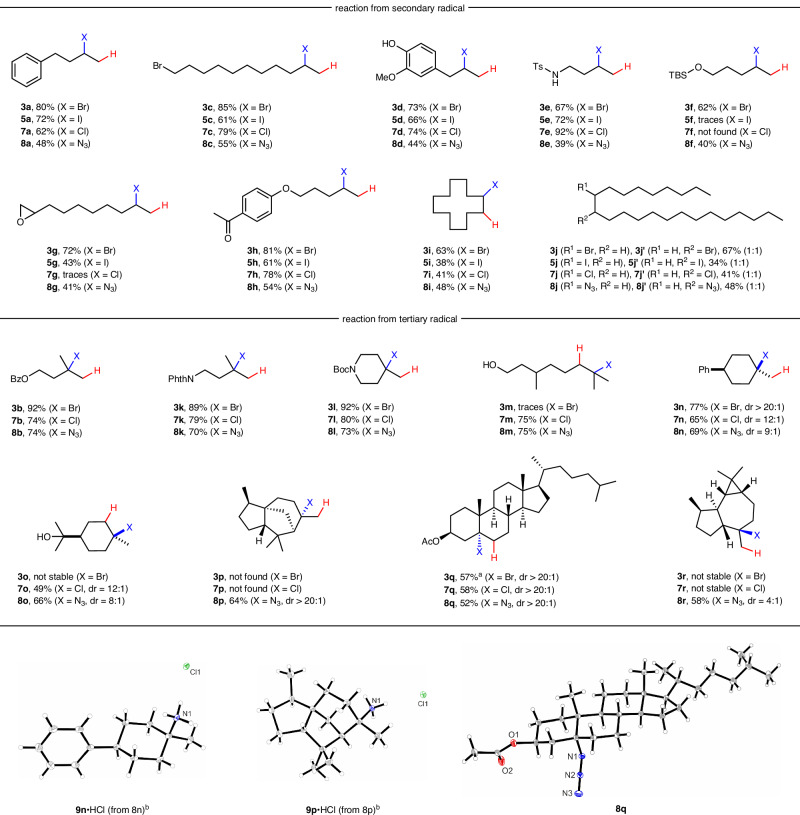

Hydrofunctionalization of various alkenes—reaction scope

With optimized conditions in hand for the individual hydrofunctionalizations, the reaction scope was examined (Fig. 2). For each monosubstituted alkene, hydrobromination, hydroiodination, hydrochlorination, and also hydroazidation were tested, while for the multisubstituted alkenes hydrobromination, hydrochlorination and hydroazidation were investigated. Considering monosubstituted alkenes, simple aliphatic systems worked well and regioselective hydrohalogenation, as well as hydroazidation, was achieved in 48–79% isolated yield (3a, 5a, 7a, and 8a). Diverse functional groups were tolerated such as a terminal bromide (3c, 5c, 7c, 8c, 55–89%), free phenol, and phenol ether (3d, 5d, 7d, 8d, 44–74%), as well as a tosylamide with a free NH entity (3e, 5e, 7e, 8e, 39–92%). Of note, in all series, the lowest yield was achieved for the hydroazidation. A TBS-protected primary alcohol was tolerated in the hydrobromination (3f, 62%) and also in the hydroazidation (8f, 40%), while silyl ether decomposition was noted during hydrochlorination and hydroiodination. The epoxide moiety survived the hydrobromination (3g, 73%), hydroiodination (5g, 43%), and hydroazidation (8g, 41%). However, hydrochlorination was not compatible with epoxide functionality. A ketone group was tolerated by all investigated hydrofunctionalizations in good yields (3h, 5h, 7h, 8h, 54–81%). Furthermore, 1,2-disubstituted alkenes could also undergo hydrofunctionalizations. For example, cis/trans-cyclododecene yielded the hydrobrominated product 3i in 63% yield. For the corresponding hydroiodination, -chlorination, and -azidation lower yields were achieved (38–48%, 5i, 7i, 8i). For the unsymmetrical 1,2-disubstituted alkene (Z)-tricos-9-ene, the products 3j, 3j’, 5j, 5j’, 7j, 7j’, and 8j, 8j’ could be isolated in 34–67% yields. As expected, we could not separate the two regioisomers and also by NMR they are indistinguishable. As the two alkyl substituents at the double bond are nearly identical, we assume that the regioisomers were formed as a 1:1 mixture, as indicated in the figure.

Fig. 2. Scope of the Fe-catalyzed hydrohalogenation and hydrofunctionalization of mono-, di- und trisubstituted alkenes including natural products.

X-ray structure of the HCl salts derived from 8n and 8p, as well as of azide 8q. Reactions were carried out on a 0.2–0.5 mmol scale and all yields provided refer to isolated yields. Diastereoselectivity (if applicable) was determined by GC or NMR analysis, and the relative configuration was assigned by X-ray analysis of single crystals or in analogy to a known related compound, see Supplementary Material.aNMR yield. bSee Supplementary Material for the procedure.

1,1-Disubstituted alkenes were investigated next. Very good isolated yields were achieved for the hydrobromination, hydrochlorination, and hydroazidation of 3-methylbut-3-en-1-yl benzoate (3b, 7b, 8b, 74–92%). A phthalimide functionality, as well as a Boc-protected secondary amine, were tolerated and the corresponding tertiary hydrofunctionalization products 3k, 7k, 8k, 3l, 7l, and 8l were obtained in good to very good yields (70–92%). We were pleased to find that trisubstituted alkenes are eligible substrates, as documented by the successful transformation of β-citronellol to provide the tertiary chloride 7m (75%) and the azide 8m (75%) that were both formed with complete Markovnikov selectivity. However, only a trace of the product was observed for the corresponding hydrobromination. Unfortunately, hydrofunctionalizations did not work for styrenes, 1,3-dienes, or allylic ethers/alcohols (for an overview of failed substrates, we refer to the Supplementary Material).

We also studied diastereoselective reactions and achieved high cis-selectivity for the hydrofunctionalization of (4-methylenecyclohexyl)benzene (3n, 7n, 8n, 47–77%). (α)-Terpineol could also be hydrochlorinated and -azidated with our three procedures and the hydrofunctionalization products 7o and 8o were isolated in 49–66% yield with similar diastereoselectivity. The hydrobrominated product 3o was observed by GC with promising selectivity, but could not be isolated due to facile decomposition. With (−)-α-cedrene only hydroazidation was achieved and 8p was isolated in good yield as a single diastereoisomer. Only very low conversion was noted for the bromination and chlorination, possibly due to the high steric shielding of the tertiary radical. Moreover, hydrochlorination and -azidation of cholesteryl acetate worked well and the corresponding hydrofunctionalization products 7q and 8q were obtained in 52–58% yield and perfect diastereoselectivity. The hydrobromination product 3q could not be isolated, due to decomposition during purification. An NMR yield of 57% could be determined from the crude mixture. (+)-Aromadendrene engaged in the hydroazidation and the tertiary azide 8r was isolated in good yield and diastereoselectivity. No clean reaction was achieved for the corresponding hydrohalogenations and isolation of 3r, as well as of 7r was not possible due to product instability.

Mechanistic investigations

To prove whether the ester 2a indeed serves as a trapping reagent for alkyl radicals, we decomposed dilauroylperoxide (DLP) in hexane at 80 °C in the presence of 2a and obtained n-undecylbromide through a bromine atom transfer reaction (Fig. 3A). The radical nature of the hydrobromination was further supported by a hydrofunctionalization with a concomitant radical 5-exo-cyclization. Hence, hydrobromination of the diene 10 gave the cyclization/bromination product 11 as a cis:trans-mixture of the diastereoisomers in 49% yield (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3. Mechanistic studies.

Mechanistic experiments (A–C) and proposed mechanism for the Fe-catalyzed hydrohalogenation of alkenes with α-halo esters (D). aGC yield.

The hydroazidation of natural (–)-α-pinene afforded the expected hydroazidation product 13a along with the hydroazidation product of limonene 13b in ~58% combined yield (Fig. 3C). Total conversion of (–)-α-pinene was 64%. 13b is formed through initial MHAT followed by radical ring-opening to give a tertiary alkyl radical, which can then be trapped by tosyl azide. Hydrobromination of (–)-α-pinene exclusively leads to the ring-opened product, which is unstable and accompanied by limonene and terpinolene, resulting from the elimination of hydrogen bromide (see Supplementary Material). Taken together, the cyclization product 11 and the ring-opening products observed when employing (–)-α-pinene strongly support the radical nature of the Fe-catalyzed hydrofunctionalization reactions.

The suggested mechanism for the hydrobromination and hydroiodination with reagents 2a and 2e is presented in Fig. 3D. Formation of the Fe–H species is considered to be the rate-determining step in these hydrofunctionalizations32. As the RubenSilane is known to be a more efficient reducing reagent for the generation of the metal hydride, it is not surprising that hydrofunctionalizations with 4 are faster as compared to the reactions run with phenylsilane36. The Fe–H complex then engages in MHAT to the alkene to give the H-adduct radical B along with a Fe(II)-complex. Radical B can reversibly trap the Fe(II)-complex to give the corresponding Fe(III)-alkyl complex A. In the productive path, alkyl radical B is iodinated or brominated by the esters 2a or 2e through halogen atom transfer to give the final products 3 or 5. The concomitantly generated α-ester radical C is then reduced by the Fe(II)/HiOPr through CPET32 to give ethyl propionate or methyl isobutyrate as byproducts and a Fe(III)OiPr complex that reacts with the silane to regenerate the starting iron hydride complex. The trapping of the alkyl radical with the halo ester should be faster than Fe–H formation, so it is surprising that the reaction time varies depending on the used radical trap and substrate type. Control experiments confirmed that the I-atom transfer with 2e is faster than the Br-transfer with 2a, as expected35. We currently assume that the longer reaction time for the hydroiodination is due to partial deactivation of the catalyst. For all reactions, conversion slows down as the reaction progresses, sometimes coming to a halt before full conversion is reached. This may be explained by competing unknown side reactions, which might destroy the catalyst or lead to a build-up of a Fe(II)-species that is not reoxidized. We can currently not fully rule out, whether the slower Br-atom transfer from 2a to the alkyl radical is occasionally mediated by the Fe-catalyst. For the more efficient iodine atom transfer we regard such a scenario as unlikely. Regarding the proposed mechanism for the alkene hydrochlorination and hydroazidation with the tosyl chloride and tosyl azide as radical trapping reagents, please refer to the Supplementary Material.

Discussion

Radical Markovnikov-type hydrohalogenation of mono-, di- and trisubstituted alkenes has been developed. As halogenation reagents commercially available α-halo esters and tosyl chloride are used. Hydroazidation is possible upon switching to tosyl azide as the trapping reagent under otherwise similar conditions. These highly regioselective radical hydrofunctionalizations are catalyzed with cheap and commercial Fe-catalysts in combination with silane as a reductant. Reactions occur under mild conditions and functional group tolerance is broad. In contrast to the classical Markovnikov hydrohalogenation with the corresponding mineral acids that proceed through cationic intermediates, which are poised for unwanted rearrangements, such a problem does not occur using the radical approach. Moreover, the radical intermediates generated after initial MHAT to the alkene can be harvested to combine the hydrofunctionalization with a typical radical cyclization or fragmentation step. For rigid alkenes, these hydrofunctionalizations occur with excellent diastereoselectivity and complete regioselectivity. Successful hydrofunctionalization of terpenes documents the potential of the herein-introduced processes in synthesis. Importantly, the alkene functionality can be found in many natural products and the introduced functionalities (halides and azide) are valuable entities for follow-up chemical transformation.

Methods

Hydrobromination of terminal and 1,2-disubstituted alkenes

Fe(acac)3 (17.7 mg, 50.0 µmol, 10 mol%) was placed in an oven-dried Schlenk tube under argon equipped with a magnetic stir bar and dissolved in dry methanol (4 mL). The alkene (0.50 mmol, 1.0 eq.) and methyl 2-bromo-2-methylpropanoate (78 µL, 0.60 mmol, 1.2 eq.) were added, followed by dropwise addition of phenylsilane (62 µL, 0.50 mmol, 1.0 eq.). The reaction was stirred for 48 h at room temperature. Afterwards, the solvent was evaporated and the residue was purified using flash chromatography to obtain the pure product.

Hydrobromination of 1,1-disubstituted and trisubstituted alkenes

Fe(dpm)3 (12.2 mg, 20.0 µmol, 10 mol%) was placed in an oven-dried Schlenk tube under argon equipped with a magnetic stir bar and dissolved in dry iPrOH (1 mL) and dry THF (1 mL). The alkene (0.20 mmol, 1.0 eq.) and methyl 2-bromo-2-methylpropanoate (28 µL, 0.21 mmol, 1.1 eq.) were added, followed by dropwise addition of isopropoxy(phenyl)silane (39 µL, 0.22 mmol, 1.0 eq.). The reaction was stirred for 48 h at room temperature. Afterwards, the solvent was evaporated and the residue was purified using flash chromatography to obtain the pure product.

Hydroiodination of terminal and 1,2-disubstituted alkenes

Fe(acac)3 (17.7 mg, 50.0 µmol, 10 mol%) was placed in an oven-dried Schlenk tube under argon equipped with a magnetic stir bar and dissolved in dry methanol (4 mL). The alkene (0.50 mmol, 1.0 eq.) and ethyl 2-iodo-propanoate (68 µL, 0.50 mmol, 1.0 eq.) were added, followed by dropwise addition of phenylsilane (62 µL, 0.50 mmol, 1.0 eq.). The reaction was stirred for 4 days at room temperature (alternatively 30 h at 40 °C). Afterwards, the solvent was evaporated and the residue was purified using flash chromatography to obtain the pure product.

Hydrochlorination of terminal and 1,2-disubstituted alkenes

Fe(acac)3 (17.7 mg, 50.0 µmol, 10 mol%) was placed in an oven-dried Schlenk tube under argon equipped with a magnetic stir bar and dissolved in dry iPrOH (2 mL) and dry THF (2 mL). The alkene (0.50 mmol, 1.0 eq.) and pTsCl (143 mg, 0.750 mmol, 1.5 eq.) were added, followed by the dropwise addition of phenylsilane (246 µL, 2.00 mmol, 4.0 eq.). The reaction was stirred for 48 h at 40 °C. Afterwards, the solvent was evaporated and the residue was purified using flash chromatography to obtain the pure product.

Hydrochlorination of 1,1-disubstituted and trisubstituted alkenes

Fe(dpm)3 (12.2 mg, 20.0 µmol, 10 mol%) was placed in an oven-dried Schlenk tube under argon equipped with a magnetic stir bar and dissolved in dry iPrOH (1 mL) and dry THF (1 mL). The alkene (0.20 mmol, 1.0 eq.) and pTsCl (57.2 mg, 0.300 mmol, 1.5 eq.) were added, followed by dropwise addition of isopropoxy(phenyl)silane (64 µL, 0.40 mmol, 2.0 eq.). The reaction was stirred for 24 h at room temperature. Afterwards, the solvent was evaporated and the residue was purified using flash chromatography to obtain the pure product.

Hydroazidation of alkenes

Fe(dpm)3 (12.1 mg, 20.0 µmol, 10 mol%) is placed in an oven-dried Schlenk tube under argon equipped with a magnetic stir bar and dissolved in dry iPrOH (1 mL) and dry THF (1 mL). The alkene (0.20 mmol, 1.0 eq.) and pTsN3 (59.2 mg, 0.300 mmol, 1.5 eq.) are added, followed by dropwise addition of isopropoxy(phenyl)silane (64 µL, 0.40 mmol, 2.0 eq.). The reaction is stirred for 24 h at room temperature. Afterwards, the solvent is evaporated and the residue is purified using flash chromatography to obtain the pure product.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank the University of Münster for supporting this work.

Author contributions

J.E., N.L.F., and A.S. conceived and designed the experiments. J.E., N.L.F., and I.R. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. J.E. and A.S. wrote the manuscript. C.G.D. conducted the X-ray crystal structure analysis.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Wen-Dao Chu, and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

Supplementary information and chemical compound information accompany this paper at www.nature.com/ncomms. The data supporting the results of this work are included in this paper or in the Supplementary Information and are also available upon request from the corresponding author.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-024-51706-x.

References

- 1.Crossley, S. W. M., Obradors, C., Martinez, R. M. & Shenvi, R. A. Mn-, Fe-, and Co-catalyzed radical hydrofunctionalizations of olefins. Chem. Rev.116, 8912–9000 (2016). 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Isayama, S. & Mukaiyama, T. Hydration of olefins with molecular oxygen and triethylsilane catalyzed by bis(trifluoroacetylacetonato)cobalt(II). Chem. Lett.18, 569–572 (1989). 10.1246/cl.1989.569 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waser, J., Gaspar, B., Nambu, H. & Carreira, E. M. Hydrazines and azides via the metal-catalyzed hydrohydrazination and hydroazidation of olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc.128, 11693–11712 (2006). 10.1021/ja062355+ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaspar, B. & Carreira, E. M. Catalytic hydrochlorination of unactivated olefins with para-toluenesulfonyl chloride. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.47, 5758–5760 (2008). 10.1002/anie.200801760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaspar, B., Waser, J. & Carreira, E. M. Cobalt-catalyzed synthesis of tertiary azides from α,α-disubstituted olefins under mild conditions using commercially available reagents. Synthesis2007, 3839–3845 (2007). 10.1055/s-2007-1000817 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yin, Y.-N. et al. Modifying commodity-relevant unsaturated polymers via Co-catalyzed MHAT. Chem10.1016/j.chempr.2024.05.021 (2024).

- 7.Ma, X. & Herzon, S. B. Non-classical selectivities in the reduction of alkenes by cobalt-mediated hydrogen atom transfer. Chem. Sci.6, 6250–6255 (2015). 10.1039/C5SC02476E [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shibutani, S., Nagao, K. & Ohmiya, H. A Dual cobalt and photoredox catalysis for hydrohalogenation of alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.146, 4375–4379 (2024). 10.1021/jacs.3c10133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu, J. et al. Co-catalyzed hydrofluorination of alkenes: photocatalytic method development and electroanalytical mechanistic investigation. J. Am. Chem. Soc.146, 4380–4392 (2024). 10.1021/jacs.3c10989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang, T., Lu, L. & Shen, Q. Iron-mediated Markovnikov-selective hydro-trifluoromethylthiolation of unactivated alkenes. Chem. Commun.51, 5479–5481 (2015). 10.1039/C4CC08655D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liang, B., Wang, Q. & Liu, Z.-Q. A Fe(III)/NaBH4-promoted free-radical hydroheteroarylation of alkenes. Org. Lett.19, 6463–6465 (2017). 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b03313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leggans, E. K., Barker, T. J., Duncan, K. K. & Boger, D. L. Iron(III)/NaBH4-mediated additions to unactivated alkenes: synthesis of novel 20′-vinblastine analogues. Org. Lett.14, 1428–1431 (2012). 10.1021/ol300173v [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taniguchi, T., Goto, N., Nishibata, A. & Ishibashi, H. Iron-catalyzed redox radical cyclizations of 1,6-dienes and enynes. Org. Lett.12, 112–115 (2010). 10.1021/ol902562j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barker, T. J. & Boger, D. L. Fe(III)/NaBH4-mediated free radical hydrofluorination of unactivated alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.134, 13588–13591 (2012). 10.1021/ja3063716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dao, H. T., Li, C., Michaudel, Q., Maxwell, B. D. & Baran, P. S. Hydromethylation of unactivated olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc.137, 8046–8049 (2015). 10.1021/jacs.5b05144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tokuyasu, T., Kunikawa, S., Masuyama, A. & Nojima, M. Co(III)−Alkyl complex- and Co(III)−alkylperoxo complex-catalyzed triethylsilylperoxidation of alkenes with molecular oxygen and triethylsilane. Org. Lett.4, 3595–3598 (2002). 10.1021/ol0201299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shigehisa, H. et al. Catalytic hydroamination of unactivated olefins using a Co catalyst for complex molecule synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc.136, 13534–13537 (2014). 10.1021/ja507295u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shigehisa, H., Aoki, T., Yamaguchi, S., Shimizu, N. & Hiroya, K. Hydroalkoxylation of unactivated olefins with carbon radicals and carbocation species as key intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc.135, 10306–10309 (2013). 10.1021/ja405219f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhunia, A., Bergander, K., Daniliuc, C. G. & Studer, A. Fe-catalyzed anaerobic mukaiyama-type hydration of alkenes using nitroarenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.60, 8313–8320 (2021). 10.1002/anie.202015740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elfert, J., Bhunia, A., Daniliuc, C. G. & Studer, A. Intramolecular radical oxygen-transfer reactions using nitroarenes. ACS Catal.13, 6704–6709 (2023). 10.1021/acscatal.3c00958 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li, F.-Y. et al. Facile construction of benzo[d][1,3]oxazocine: reductive radical dearomatization of N-alkyl quinoline quaternary ammonium salts. Org. Lett.26, 1996–2001 (2024). 10.1021/acs.orglett.3c04243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lang, M., Tardieu, D., Pousse, B., Compain, P. & Kern, N. Diastereoselective access to C, C -glycosyl amino acids via iron-catalyzed, auxiliary-enabled MHAT coupling. Chem. Commun.60, 3154–3157 (2024). 10.1039/D3CC06249J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen, Y., Qi, J., Mao, Z. & Cui, S. Fe-catalyzed hydroalkylation of olefins with para-quinone methides. Org. Lett.18, 2722–2725 (2016). 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b01173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kato, K. & Mukaiyama, T. Iron(III) complex catalyzed nitrosation of terminal and 1,2-disubstituted olefins with butyl nitrite and phenylsilane. Chem. Lett.21, 1137–1140 (1992). 10.1246/cl.1992.1137 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gui, J. et al. Practical olefin hydroamination with nitroarenes. Science348, 886–891 (2015). 10.1126/science.aab0245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng, J., Qi, J. & Cui, S. Fe-catalyzed olefin hydroamination with diazo compounds for hydrazone synthesis. Org. Lett.18, 128–131 (2016). 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b03317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xie, Y. et al. Ligand-promoted iron(III)-catalyzed hydrofluorination of alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.58, 7097–7101 (2019). 10.1002/anie.201902607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao, B., Zhu, T., Ma, M. & Shi, Z. SOMOphilic alkynylation of unreactive alkenes enabled by iron-catalyzed hydrogen atom transfer. Molecules27, 33 (2022). 10.3390/molecules27010033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kong, L., Gan, X., van der Puyl Lovett, V. A. & Shenvi, R. A. Alkene hydrobenzylation by a single catalyst that mediates iterative outer-sphere steps. J. Am. Chem. Soc.146, 2351–2357 (2024). 10.1021/jacs.3c13398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gan, X. et al. Carbon quaternization of redox active esters and olefins by decarboxylative coupling. Science384, 113–118 (2024). 10.1126/science.adn5619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lo, J. C., Yabe, Y. & Baran, P. S. A practical and catalytic reductive olefin coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc.136, 1304–1307 (2014). 10.1021/ja4117632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim, D., Rahaman, S. M. W., Mercado, B. Q., Poli, R. & Holland, P. L. Roles of iron complexes in catalytic radical alkene cross-coupling: a computational and mechanistic. Study. J. Am. Chem. Soc.141, 7473–7485 (2019). 10.1021/jacs.9b02117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mondal, B., Hazra, S., Chatterjee, A., Patel, M. & Saha, J. Fe-catalyzed hydroallylation of unactivated alkenes with vinyl cyclopropanes. Org. Lett.25, 5676–5681 (2023). 10.1021/acs.orglett.3c02105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen, X.-L., Dong, Y., Tang, L., Zhang, X.-M. & Wang, J.-Y. A synthetic strategy for 2-alkylchromanones: Fe(III)-catalyzed reductive cross-coupling of unactivated alkenes with chromones. Synlett29, 1851–1856 (2018). 10.1055/s-0036-1591601 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Curran, D. P., Bosch, E., Kaplan, J. & Newcomb, M. Rate constants for halogen atom transfer from representative.alpha.-halo carbonyl compounds to primary alkyl radicals. J. Org. Chem.54, 1826–1831 (1989). 10.1021/jo00269a016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Obradors, C., Martinez, R. M. & Shenvi, R. A. Ph(i-PrO)SiH2: an exceptional reductant for metal-catalyzed hydrogen atom transfers. J. Am. Chem. Soc.138, 4962–4971 (2016). 10.1021/jacs.6b02032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schiesser, C. H., Smart, B. A. & Tran, T.-A. An ab initio study of some free-radical homolytic substitution reactions at halogen. Tetrahedron51, 3327–3338 (1995). 10.1016/0040-4020(95)00054-C [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Supplementary information and chemical compound information accompany this paper at www.nature.com/ncomms. The data supporting the results of this work are included in this paper or in the Supplementary Information and are also available upon request from the corresponding author.