Highlights

-

•

The effect of ultrasonic treatment in the production of pregelatinized rice flour was studied.

-

•

The solubility of rice flour improved with treatment time.

-

•

The collapse of the rice gel structure and decrease in viscosity were confirmed.

-

•

Provides new applications for the use of rice flour in the beverage industry.

Keywords: Pregelatinized rice flour, Solubility, Ultrasonication, Physical modification

Abstract

This study evaluated the physical and rheological properties of whole rice flour treated for different sonication times (0–15 min). Ultrasonication reduces the particle size of rice flour and improves its solubility. Viscosity tests using RVA and steady shear showed a notable decrease in the viscosity of the rehydrated pregelatinized rice flour. Although no unusual patterns were observed in the XRD analysis, the FT-IR and microstructure morphology findings suggest that ultrasonication led to structural changes in the rice flour. Overall, the study indicates that ultrasonication is a practical and clean method for producing plant-based drinks from rice flour, which could expand its limited applications in the beverage industry.

1. Introduction

Plant-based drinks are colloidal suspensions or emulsions with a particle distribution of 5–20 μm consisting of dissolved and decomposed plant material, resembling milk in terms of appearance, nutritional properties, and consistency [1], [2]. The demand for these products is increasing because of functional improvements in the face of lactose intolerance, which affects more than 50 % of the people in Asia; environmental awareness of the sustainability of milk production; and ethical considerations regarding milk consumption, including vegetarian and vegan diets [3], [4]. Plant-based drinks are classified according to the type of plant source, such as cereals, nuts, legumes, or oilseeds [5]. Additionally, the nutritional quality and stability of the final products are of great concern and are influenced by the degradation method, heat treatment, homogenization, and storage conditions [6].

Rice (Oryza sativa) is the staple food of more than half of the world's population and accounts for approximately 20 % of the energy needs, commercially grown over 2,000 rice varieties worldwide [7]. Rice flour is considered an interesting grain in the market for plant-based meals because it can replace wheat more easily than other grains or similar grains owing to its functional properties, such as mild taste, digestibility, and low allergenicity [7], [8]. However, it presents a challenge for its application in the beverage industry because of its limited solubility in water and discernible viscosity variation at high temperatures. To maintain the structural integrity of rice beverages, researchers have utilized saccharification of rice, the application of modified starch, and emulsifiers [9], [10], [11], [12].

Physical modification of starch and proteins offers industrial advantages over chemical or enzymatic methods, making it environmentally friendly, cost-effective, and energy-saving [13]. Ultrasonication, which is considered a green process suitable for food applications, is a physical processing technology that uses high-frequency acoustic waves that human hearing cannot detect (>16 kHz) [14]. In a liquid–solid system, ultrasonic waves generate small bubbles that periodically form and collapse, resulting in acoustic cavitation [15]. Acoustic cavitation produces strong localized transient heat and shear forces and causes mechanical damage such as cracks, pores and cause mechanical damage such as cracks, pores, and irregular surfaces within the food matrix [16], [17], [18]. Ultrasonication causes modifications of starch granules [19] and gelatinized starch [20], altering starch crystallinity [21], breaking down amylopectin chains [22], increasing solubility [23], and affecting rheological properties [24]. Ultrasonication can also modify the secondary structures of plant proteins, expose internal hydrophobic residues, and affect intermolecular interactions [25], [26]. These modified proteins can interact with the surrounding biopolysaccharides and assemble into structures with new functions, such as solubility and emulsifying power [27], [28], [29]. However, the specific impact of ultrasonication on the structure of gelatinized rice gels is not yet fully understood.

Therefore, this study prepared pregelatinized rice flour through ultrasonication and investigated the impact of time parameters on physicochemical changes, including particle size distribution and hydration, pasting, and rheological properties. Additionally, the morphological structure was confirmed using X-ray diffraction (XRD) spectroscopy, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Preparation of rice gel

Rice flour of Japonica varieties from Korea (“Baromi2″) was dry-ground using an air classifier mill. The amylose content of rice measured using the amylose/amylopectin assay kit (K-AMYL, Neogen, MI, USA) was 12.3 %. To gelatinize the rice flour, rice slurry (1.5 kg) was prepared by dispersing 10 % rice flour (w/w) in water. The rice slurry was then placed in a 90 °C water bath and stirred for 1 h using an overhead stirrer with a triple-bladed impeller (Ф50 mm) at 1,200 rpm. Considering the results of Li et al. [30] that the degree of gelatinization of the rice grains parboiled for more than 15 min was 100 %, it was assumed that the rice flour was completely gelatinized using the method used in this study.

2.2. Ultrasonication

Ultrasonication was performed using a sonicator (VCX-500, Sonics & Materials, Newtown, CT, USA) with a 13 mm diameter probe. The position of the probe was adjusted so that it was immersed to a depth of 10 mm in rice gel contained in a 250-mL beaker (Φ70). Rice gel (200 g) was sonicated for different durations (0, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15 min) at a frequency of 20 kHz and amplitude of 70 %. To prevent a rapid rise in temperature of the rice gel, the beaker was placed in an ice bucket and a power on/off pulse (10/10 s) was used. The sample temperature immediately after sonication was ranged at 30–35 °C. The sonicated samples were stored at −20 °C for 1 h and lyophilized for 48 h. The dried samples were ground in a laboratory grinder and passed through a 150-µm sieve (#100) to obtain pregelatinized rice powder. The powdered samples were named 0 T, 3 T, 6 T, 9 T, 12 T, and 15 T, depending on the treatment time (0, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15 min). Ungelatinized raw rice flour was prepared for the control group and named “Raw.” The samples were stored at 4 °C and used for further experiments. The initial moisture content of the powdered samples was 2.5 ± 0.1 %.

2.3. Particle size distribution

Aqueous dispersions of each sample were prepared with a 5 % (w/w) concentration of the sample in distilled water. The particle size distribution of the sample dispersion was measured in the range of 0.02–2000 µm using a Bettersizer S2 raser particle size analyzer (Bettersize Instrument Ltd, Costa Mesa, CA, USA). The refractive indices of the sample and medium were 1.52 and 1.33, respectively.

2.4. Hydration properties

The water absorption index (WAI) of pregelatinized rice flour was calculated using the slightly modified method described by He et al. [31]. Each samples was dispersed in 40 mL distilled water (0.5 %, w/v), stirred intermittently for 30 min, and centrifuged at 3000 × g for 20 min. The sediment was weighed to determine the WAI and expressed in g sediment/g flour dry matter (DM). The swelling power (SP) and water solubility (WS%) were determined with slight modifications to the method described by Vela et al. [32]. Two grams of the sample was dispersed in 40 mL of distilled water within 50 mL conical tubes. The samples were placed in a shaking water bath at 90 °C for 30 min, cooled to 25 °C, and centrifuged at 3000 × g for 20 min. The supernatant was poured into an evaporating dish and maintained overnight in an oven at 105 °C to determine the solid content (WS%). The sediment was weighed to determine the SP expressed in g sediment/g of insoluble solids in flour.

2.5. Dispersion stability

To determine the stability of rice flour dispersion in water, turbidity was determined by modifying the method described by Alade et al. [33]. Two hundred milliliters of a 5 % aqueous solution (w / v) of each sample was prepared and placed in a clear glass jar, and 4 mL of a 4.5 mL disposable polystyrene cuvette (PS Microcuvettes, Dispolab Kartell, Milan, Italy) and retained for 12 h in a UV–visible spectrophotometer (Cary 3500, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Absorbance at a wavelength of 600 nm was measured at 10-min intervals. After the measurement, 4 mL of fresh samples were recollected, and turbidity was determined using the same instrument and wavelength at 1-day intervals for 7 days. Photographs and visual observations of sample vials were also conducted. For comparison, the obtained absorbance data were normalized to a value between 0 and 1, with the value measured immediately after sample preparation being 1.

2.6. Pasting properties

The pasting properties of the pregelatinized rice flour samples were determined using a rapid visco analyzer (RVA4500, PerkinElmers, Shelton, CT, USA) following the AACC International Method 61–02.01 [34]. The peak viscosity, trough viscosity, final viscosity, breakdown, and setback were calculated using the software provided with RVA4500 (PerkinElmers). The samples were measured in triplicate.

2.7. Rheological properties

Rheological tests were performed using a Discovery HR-10 (TA Instruments, DE, USA) with a smooth parallel plate geometry (40 mm diameter). The rehydrated gel samples were prepared following the protocol described in Section 2.6. Flow sweep tests were performed at a shear rate of 0.1–1000 s−1, and the results were fitted to the power-law model equation:

| (1) |

where τ is the shear stress (Pa), K is the consistency index (Pa · sn), γ is the shear rate (s−1), and n is the flow behavior index (dimensionless). Parameter values are presented as mean ± SD.

2.8. X-ray diffraction (XRD)

XRD patterns were obtained using an X’pert Pro Powder (Malvern Panalytical Ltd) equipped with Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 0.154 nm) at a voltage of 40 kV and a current of 40 mA. Before measurement, all the samples were equilibrated to 25 % relative humidity in an incubator (OH-3S, AS ONE, Osaka, Japan) at 25 °C. The radiation intensities were measured in the range of 5°–40° of 2θ diffraction angle, with a scan step size of 0.02°, receiving slit width of 0.02 nm, scatter slit width of 2.92°, divergence slit width of 1°, and a rate of 1.2°/min.

2.9. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR)

The FT-IR spectra in the wavenumber range of 800–1200 cm−1 of the samples were recorded using a Spectrum 3 (PerkinElmer) coupled with an attenuated total reflectance (ATR) device equipped with a diamond crystal. All samples were equilibrated at a relative humidity of 25 % as described in Section 2.8.

2.10. Field electron-scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM)

FE-SEM (Gemini SEM 300, Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) was used to study the surface microstructure of pregelatinized rice flour. Each sample was coated with Pt for 30 s. Visualization was performed at a voltage of 3 kV and a magnification of 1000 × . Representative micrographs are selected for illustrative purposes.

2.11. Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using SPSS software (version 26.0; Bitstream, Cambridge, MN, USA). Duncan's post hoc test was used to evaluate significant differences between samples at p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Particle size distribution

The particle size distribution of the powdered rice dispersion as a function of sonication time is shown in Fig. 1. The increase in the particle size distribution values of 0 T compared with raw rice flour was supported by the results of Ma et al. [35], who reported that the median particle size of rice flour heated at high temperatures nearly doubled. Swelling and gelatinization break the structure of starch granules, and the released amylose molecules may aggregate during retrogradation [36], [37]. In contrast to the decrease in volume distribution with a sonication time of approximately 100 µm, the volume distribution increased with a sonication time of approximately 0.8 µm and 10 µm. Kentish and Ashokkumar [38] reported that cavitation of microbubbles caused by ultrasonication generates instantaneous high heat (>5000 K) and pressure (70–100 mPa), resulting in physical shear forces, and Bonto et al. [39] suggested that these shear forces are likely to cause chemical reactions, resulting in the cleavage of starch chains. In this sense, the results of the present study can also be interpreted as a reduction in particle size due to the shear force of cavitation.

Fig. 1.

Particle size distribution of pregelatinized rice flour with ultrasonication. Raw: Raw rice flour, 0 T: Pregelatinized rice flour, 3 T–15 T: pregelatinized rice flour with ultrasonication (3, 6, 9, 12, 15 min).

3.2. Hydration properties

The results of the hydration properties of the powdered rice as a function of sonication time are shown in Table 1. The WAI was the highest at 0 T and decreased with sonication time, with 12 T and 15 T showing similar trends to raw rice flour. The SP notably decreased with ultrasonication compared with F and 0 T. Lai et al. [40] reported that pregelatinization of rice starch modifies the crystal structure of starch and increases water retention, swelling power, and starch solubility due to amylose elution and water influx, which are similar to the results between Raw and 0 T in this study. However, the decrease in WAI and SP in the sonicated sample can be attributed to the severe destruction of starch molecules and crystal structures with ultrasonication (See section 3.8). The significant increase in solubility (70–85.95 %) as a result of ultrasonication demonstrated the effect of ultrasonication. The solubility of 0 T in this study was similar to that of the pregelatinized starch (11.97 %) reported by He et al. [31]. The significant increase in starch solubility may be due to interaction with modified proteins. The solubility of the soy protein-rice starch complex increased compared with that of a simple mixture [41]. Ultraonication induces the modification of proteins to form protein-polysaccharide complexes and effectively improves the solubility and emulsification properties of proteins [42]. As the result of Niu et al. [43] that the interaction between rice bran protein hydrolyzate and gelatinized rice starch, the recrystallization of gelatinized rice starch may have been inhibited by the modified rice protein, and its solubility may have increased.

Table 1.

Hydration properties of pregelatinized rice flour with ultrasonication. Raw: Raw rice flour, 0 T: Pregelatinized rice flour, 3 T–15 T: Pregelatinized rice flour with ultrasonication (3, 6, 9, 12, 15 min). a-f: Different lowercase alphabets in the same column mean significantly different.

| Sample | WAI | SP | WS% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw | 2.73 ± 0.05e | 9.25 ± 1.01b | 8.59 ± 1.56f |

| 0 T | 10.47 ± 0.46a | 13.08 ± 0.06a | 13.06 ± 0.31e |

| 3 T | 6.76 ± 0.71b | 3.94 ± 0.12d | 70.84 ± 0.72d |

| 6 T | 4.88 ± 0.12c | 2.53 ± 0.03c | 77.37 ± 0.20c |

| 9 T | 3.59 ± 0.44d | 1.53 ± 0.04e | 82.80 ± 0.41b |

| 12 T | 2.65 ± 0.41e | 1.12 ± 0.04e | 85.95 ± 0.04a |

| 15 T | 3.06 ± 0.17de | 1.16 ± 0.09e | 85.70 ± 0.63a |

WAI: water absorption index; SP: swelling power; WS%: water solubility (%).

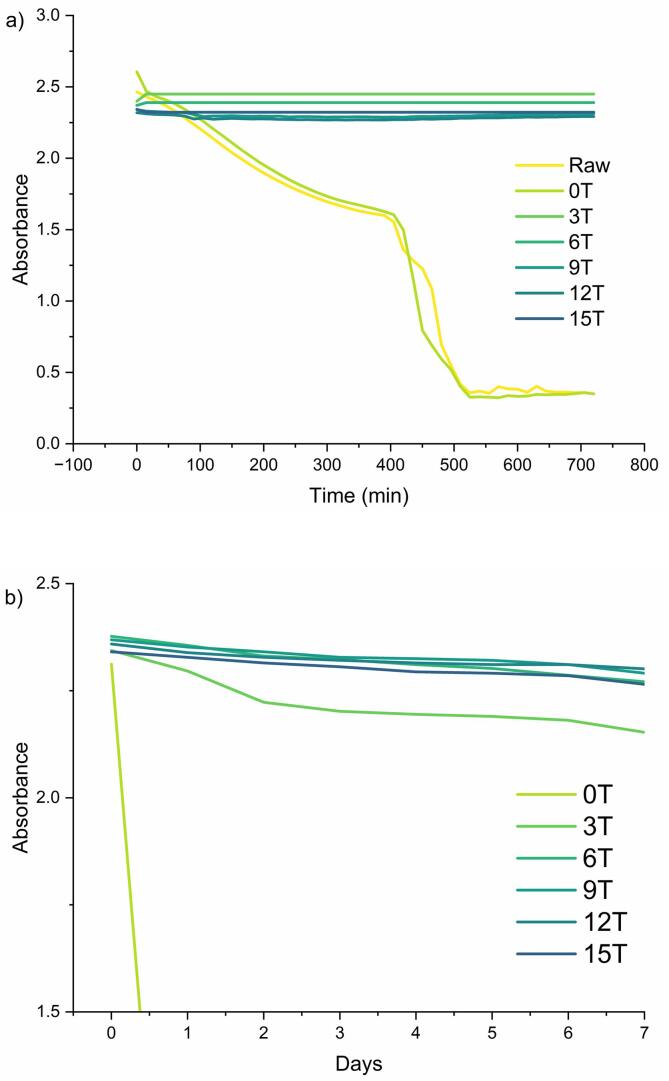

3.3. Dispersion stability

Fig. 2a shows the turbidity measured over a period of 12 h. 0 T represents a steady decrease in the normalized absorbance value and a sharp reduction near 420 min, in contrast to the absence of a change in turbidity up to 12 h in all sonicated groups. No significant changes were observed in the 7-day turbidity measurements of the sonicated samples (Fig. 2b). Changes in absorbance occur through processes in which light passing through the center of a quartz cell is refracted, reflected, or absorbed by colloidal particles [44]. Therefore, a decrease in the turbidity of the dispersion indicates the unilateral behavior of colloidal particles within the cell, indicating a lack of stability [45]. The constant turbidity value after 540 min can be interpreted as being caused by water-soluble substances in the dispersion. As a result, sedimentation occurs at 0 T stored for 7 days, unlike the other samples (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Turbidity changes of pregelatinized rice flour with ultrasonication. a) shows the turbidity measured over a period of 12 h, and b) shows the turbidity measured over 7 days. Raw: Raw rice flour, 0 T: Pregelatinized rice flour, 3 T–15 T: pregelatinized rice flour with ultrasonication (3, 6, 9, 12, 15 min).

Fig. 3.

Photographs of rehydrated pregelatinized rice flour with ultrasonication. Raw: Raw rice flour, 0 T: Pregelatinized rice flour, 3 T–15 T: pregelatinized rice flour with ultrasonication (3, 6, 9, 12, 15 min).

3.4. Pasting properties

The RVA paste profile of pregelatinized rice flour is shown in Fig. 4. All pregelatinized rice flours showed a decrease in viscosity with increasing temperature. This curve shape differs from that of raw rice flour (R), which shows typical starch-pasting properties [46]. A study by Lai et al. [47] also showed a similar RVA curve for pregelatinized rice flour, which was attributed to the polymer properties of pregelatinized rice flour. The viscosity of all sonicated rice flours showed some breakdown and setback but was very low overall. After 6 min of treatment, the viscosity was close to 0 in all heating and cooling sections, suggesting that it barely underwent additional gelatinization after the ultrasonication. The RVA paste profile was significantly correlated with the gelatinization temperature measured by DSC [48], and no endothermic peak was found in DSC for any of the sonicated samples in this study (data not shown). The values of specific pasting parameters are listed in Table 2. A clear reduction in pasting viscosity of sonicated rice flour was similar to the results of enzyme-treated [49] and heat-moisture treated rice flour [50]. Interactions between the modified rice starch and proteins may have contributed to the decrease in viscosity. Puncha-arnon & Uttapap [50] compared the RVA paste profiles of rice flour and rice starch and found that the presence of proteins modified with heat-moisture treatment reduced the gelatinization viscosity of rice flour. Stable low viscosity, narrowly independent of temperature changes of 50–90 °C, is advantageous in beverage processing, especially in sterilization processes [2].

Fig. 4.

Pasting profiles of pregelatinized rice flour with ultrasonication. Raw: Raw rice flour, 0 T: Pregelatinized rice flour, 3 T–15 T: pregelatinized rice flour with ultrasonication (3, 6, 9, 12, 15 min).

Table 2.

Pasting properties of pregelatinized rice flour with ultrasonication Raw: Raw rice flour, 0 T: Pregelatinized rice flour, 3 T–15 T: pregelatinized rice flour with ultrasonication (3, 6, 9, 12, 15 min) PV: a-d: Different lowercase alphabets in the same column mean significantly different.

| Sample | PV (cP) | TV (cP) | FV (cP) | BD (cP) | SB (cP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw | 1732 ± 88b | 899 ± 39a | 1855 ± 69a | 833 ± 49b | 124 ± 21a |

| 0 T | 2678 ± 47a | 903 ± 36a | 1859 ± 63a | 1774 ± 26a | −819 ± 32d |

| 3 T | 243 ± 19c | 83 ± 3b | 159 ± 5b | 159 ± 16c | −83 ± 14c |

| 6 T | 143 ± 2d | 52 ± 1bc | 91 ± 2c | 91 ± 2d | −52 ± 2b |

| 9 T | 95 ± 3d | 34 ± 2c | 64 ± 7c | 61 ± 2d | −30 ± 9b |

| 12 T | 96 ± 2d | 28 ± 1c | 55 ± 2c | 68 ± 2d | −40 ± 2b |

| 15 T | 86 ± 2d | 26 ± 2c | 53 ± 3c | 59 ± 2d | –33 ± 3b |

PV: peak viscosity; TV: trough viscosity; BV: breakdown viscosity; FV: final viscosity; SV: setback viscosity;

3.5. Rheological properties

The change in the viscosity of pregelatinized rice flour with the shear rate is shown in Fig. 5. The apparent viscosities of all samples tended to decrease with increasing shear rate, indicating typical shear-thinning behavior. The non-Newtonian fluid behavior of the rice gel is interpreted as the collapse of the network of entangled polysaccharide molecules during shearing [51]. The results of fitting the power-law model of the shear stress versus shear rate curve with steady shear measurements are presented in Table 3. The consistency index (K) decreased with sonication time, and the flow behavior index (n) increased with sonication time, indicating that the shear-thinning behavior of the rice gel was weakened by ultrasonication and became closer to the properties of a Newtonian fluid. The flow behavior index of 12 T and 15 T was similar to the result of Silva et al. [52] demonstrating that of a plant-based beverage prepared with Brazil nuts (0.651–0.752). Lower viscosity and higher flow behavior index result in lower head losses in flow, which reduces power and production costs, suggesting the suitability of rice flour sonication for beverage applications [52].

Fig. 5.

Apparent viscosity versus the shear rate of pregelatinized rice gel. Raw: Raw rice flour, 0 T: Pregelatinized rice flour, 3 T–15 T: pregelatinized rice flour with ultrasonication (3, 6, 9, 12, 15 min).

Table 3.

The power-law model parameters of pregelatinized rice gel.

| Sample | K | n | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw | 57.39 ± 0.67b | 0.28 ± 0.00e | 0.997 |

| 0 T | 61.71 ± 4.95a | 0.29 ± 0.01e | 0.995 |

| 3 T | 9.24 ± 0.37c | 0.46 ± 0.01d | 0.999 |

| 6 T | 2.46 ± 0.32d | 0.55 ± 0.02c | 0.999 |

| 9 T | 0.76 ± 0.07d | 0.64 ± 0.02b | 0.999 |

| 12 T | 0.45 ± 0.01d | 0.67 ± 0.01a | 0.999 |

| 15 T | 0.34 ± 0.04d | 0.67 ± 0.01a | 0.999 |

F: Raw rice flour, 0 T: Pregelatinized rice flour, 3 T–15 T: pregelatinized rice flour with ultrasonication (3, 6, 9, 12, 15 min). a-e: Different lowercase alphabets in the same column mean significantly different.

3.6. XRD

The XRD patterns of the native and ultrasonically treated pregelatinized rice flours are shown in Fig. 6. Raw rice flour showed a crystalline form of type A starch, with peaks at 15.1°, 17.1°, 17.8°, and 23.2°. The 0 T and sonicated samples exhibited peaks at 13° and 20°, corresponding to a V-type crystal structure, indicating that complete gelatinization had occurred. The peak at 20° is due to the formation of a V-type inclusion complex by lipids and amylose helices [53]. There was no change in the XRD peaks, regardless of sonication time. Several studies have reported that ultrasonication does not change the XRD pattern [54], [55], [56], [57]. Amini et al. [24] declared that the diffraction intensity decreased with ultrasonication, which was different from the results of this study. Recrystallization during starch retrogradation can change the XRD pattern [58]. However, the pregelatinized rice flour in this study did not recrystallize. The structural changes in rice flour induced by ultrasonication might be due to preferential damage to the amorphous regions.

Fig. 6.

X-ray diffraction patterns of pregelatinized rice flour with ultrasonication. Raw: Raw rice flour, 0 T: Pregelatinized rice flour, 3 T–15 T: pregelatinized rice flour with ultrasonication (3, 6, 9, 12, 15 min).

3.7. FTIR

Fig. 7 shows a comparison of the spectra of the rice flour samples. The band intensities at 995 cm−1 and 1022-1 are data mainly used to determine the ratio of crystalline and amorphous starch [59]. The band at 995 cm−1 depicts the bending of C-O-C bonds and is associated with the double helices of amylose and the crystallinity of starch [60]. The band intensity at 1022 cm−1 indicates the C-OH bond and indicates the amorphous region of starch [60]. Depending on the sonication time, the intensity of the band at 995 cm−1 decreased and that at 1022 cm−1 increased. This suggests that ultrasonication affects the formation of amylose double helices and increases the amorphous region of the rice starch. Similar cases have been reported in which the band intensity of starch samples at 1022 cm−1 was increased by ultrasonication [61], [62].

Fig. 7.

The Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy of pregelatinized rice flour with ultrasonication. Raw: Raw rice flour, 0 T: Pregelatinized rice flour, 3 T–15 T: pregelatinized rice flour with ultrasonication (3, 6, 9, 12, 15 min).

3.8. FE-SEM

The microstructural changes in pregelatinized rice flour are shown in Fig. 8. Similar to the heat-treated rice flour particles reported by Wu et al. [7], particles with multiple cavities were detected in the SEM images at 0 T, 3 T, and 6 T. As the ultrasonication progressed, particles with a small overall size and flat shape were observed. Honeycomb-shaped particles are thought to be generated by the complex formation between amylose leached from the swelling of starch granules and thermally unfolded protein chains [63]. Physical deformation may disrupt the formation of these complexes and cause structural changes in rice flour.

Fig. 8.

The scanning electron microscopy images of pregelatinized rice flour with ultrasonication (×1,000). Raw: Raw rice flour, 0 T: Pregelatinized rice flour, 3 T–15 T: pregelatinized rice flour with ultrasonication (3, 6, 9, 12, 15 min).

4. Conclusions

In the present study, ultrasonication was found to significantly enhance the solubility of pregelatinized rice flour. The ultrasonication broke down the rice gel structure, significantly reduced viscosity, and increased dispersion stability. Overall, this study suggests that ultrasonication is a highly effective, environmentally friendly, and industrially viable method for producing non-fermented beverages from rice flour. This could improve the limited application of rice flour in the beverage industry owing to its low solubility.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the author(s) used Paperpal to improve language and readability. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Hyeonbin Oh: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. Jung-Hyun Nam: Methodology, Data curation. Bo-Ram Park: Writing – review & editing, Methodology. Kyung Mi Kim: Writing – review & editing, Validation. Ha Yun Kim: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. Yong Sik Cho: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Research Program for Agricultural Science & Technology Development (Project No. PJ01728203) and the National Institute of Agricultural Science, Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

References

- 1.Yadav D.N., Bansal S., Jaiswal A.K., Singh R. Plant based dairy analogues: an emerging food. Agri Res & Tech. 2017;10:1–4. https://krishi.icar.gov.in/jspui/handle/123456789/28957 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aydar E.F., Tutuncu S., Ozcelik B. Plant-based milk substitutes: Bioactive compounds, conventional and novel processes, bioavailability studies, and health effects. J. Funct. Food. 2020;70 doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2020.103975. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lomer M.C.E., Parkes G.C., Sanderson J.D. Review article: lactose intolerance in clinical practice – myths and realities. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008;27:93–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siddiqui S.A., Mehany T., Schulte H., Pandiselvam R., Nagdalian A.A., Golik A.B., Asif Shah M., Muhammad Shahbaz H., Maqsood S. Plant-based milk – Thoughts of researchers and industries on what should be called as ´milḱ. Food Rev. Intern. 2023:1–28. doi: 10.1080/87559129.2023.2228002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sethi S., Tyagi S.K., Anurag R.K. Plant-based milk alternatives an emerging segment of functional beverages: a review. J Food Sci Technol. 2016;53:3408–3423. doi: 10.1007/s13197-016-2328-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reyes-Jurado F., Soto-Reyes N., Dávila-Rodríguez M., Lorenzo-Leal A.C., Jiménez-Munguía M.T., Mani-López E., López-Malo A. Plant-based milk alternatives: types, processes, benefits, and characteristics. Food Rev. Intern. 2023;39:2320–2351. doi: 10.1080/87559129.2021.1952421. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Villanueva M., Harasym J., Munoz J.M., Ronda F. Microwave absorption capacity of rice flour. Impact of the radiation on rice flour microstructure, thermal and viscometric properties. J. Food Engg. 2018;224:156–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2017.12.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu Y., Chen Z., Li X., Wang Z. Retrogradation properties of high amylose rice flour and rice starch by physical modification. LWT-Food Sci. Tech. 2010;43:492–497. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2009.09.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghosh K., Ray M., Adak A., Dey P., Halder S.K., Das A., Jana A., Parua S., Mohapatra P.K.D., Pati B.R. Microbial, saccharifying and antioxidant properties of an Indian rice based fermented beverage. Food Chem. 2015;168:196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferreira S.M., Caliari M., Júnior M.S.S., Beleia A.D.P. Infant dairy-cereal mixture for the preparation of a gluten free cream using enzymatically modified rice flour. LWT-Food Sci. Tech. 2014;59:1033–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2014.06.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koyama M., Kitamura Y. Development of a new rice beverage by improving the physical stability of rice slurry. J. Food Engg. 2014;131:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2014.01.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russell K., Delahunty C. The effect of viscosity and volume on pleasantness and satiating power of rice milk. Food Qual. Pref. 2004;15:743–750. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2003.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu Z., Qiao D., Zhao S., Lin Q., Zhang B., Xie F. Nonthermal physical modification of starch: An overview of recent research into structure and property alterations. Internat. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022;203:153–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.01.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patist A., Bates D. Ultrasonic innovations in the food industry: From the laboratory to commercial production. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Tech. 2008;9:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2007.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu F. Impact of ultrasound on structure, physicochemical properties, modifications, and applications of starch. Tren. Food Sci. Tech. 2015;43:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2014.12.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ashokkumar M. Applications of ultrasound in food and bioprocessing. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015;25:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bai W., Hébraud P., Ashokkumar M., Hemar Y. Investigation on the pitting of potato starch granules during high frequency ultrasound treatment. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;35:547–555. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Sullivan, J.J. Applications of ultrasound for the functional modification of proteins and submicron emulsion fabrication, PhD Thesis, University of Birmingham, 2015. https://etheses.bham.ac.uk/id/eprint/6086/ (accessed April 1, 2024).

- 19.Sujka M. Ultrasonic modification of starch–Impact on granules porosity. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;37:424–429. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iida Y., Tuziuti T., Yasui K., Towata A., Kozuka T. Control of viscosity in starch and polysaccharide solutions with ultrasound after gelatinization. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Techno. 2008;9:140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2007.03.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Falsafi S.R., Maghsoudlou Y., Rostamabadi H., Rostamabadi M.M., Hamedi H., Hosseini S.M.H. Preparation of physically modified oat starch with different sonication treatments. Food Hydrocol. 2019;89:311–320. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.10.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei B., Qi H., Zou J., Li H., Wang J., Xu B., Ma H. Degradation mechanism of amylopectin under ultrasonic irradiation. Food Hydrocol. 2021;111 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.106371. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang H., Xu K., Ma Y., Liang Y., Zhang H., Chen L. Impact of ultrasonication on the aggregation structure and physicochemical characteristics of sweet potato starch. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;63 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.104868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amini A.M., Razavi S.M.A., Mortazavi S.A. Morphological, physicochemical, and viscoelastic properties of sonicated corn starch. Carbohy. Polym. 2015;122:282–292. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang H., Claver I.P., Zhu K.-X., Zhou H. The effect of ultrasound on the functional properties of wheat gluten. Molec. 2011;16:4231–4240. doi: 10.3390/molecules16054231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu Z., Zhu W., Yi J., Liu N., Cao Y., Lu J., Decker E.A., McClements D.J. Effects of sonication on the physicochemical and functional properties of walnut protein isolate. Food Res. Internat. 2018;106:853–861. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thirunavookarasu N., Kumar S., Rawson A. Effect of ultrasonication on the protein–polysaccharide complexes: a review. Food Meas. 2022;16:4860–4879. doi: 10.1007/s11694-022-01567-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li C., Huang X., Peng Q., Shan Y., Xue F. Physicochemical properties of peanut protein isolate–glucomannan conjugates prepared by ultrasonic treatment. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2014;21:1722–1727. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dong D., Cui B. Fabrication, characterization and emulsifying properties of potato starch/soy protein complexes in acidic conditions. Food Hydrocol. 2021;115 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2021.106600. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li H., Yan S., Yang L., Xu M., Ji J., Mao H., Song Y., Wang J., Sun B. Starch gelatinization in the surface layer of rice grains is crucial in reducing the stickiness of parboiled rice. Food Chem. 2021;341 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He X., Xia W., Chen R., Dai T., Luo S., Chen J., Liu C. A new pre-gelatinized starch preparing by gelatinization and spray drying of rice starch with hydrocolloids. Carbohy. Polym. 2020;229 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vela A.J., Villanueva M., Solaesa Á.G., Ronda F. Impact of high-intensity ultrasound waves on structural, functional, thermal and rheological properties of rice flour and its biopolymers structural features. Food Hydrocol. 2021;113 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.106480. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alade O.S., Mahmoud M., Al Shehri D.A., Sultan A.S. Rapid determination of emulsion stability using turbidity measurement incorporating artificial neural network (ANN): experimental validation using video/optical microscopy and kinetic modeling. ACS Omega. 2021;6:5910–5920. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.1c00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.AACC, Method 61-02.01. Determination of the pasting properties of rice with the rapid visco analyzer, AACC International Approved Methods of Analysis. (2000).

- 35.Ma M., He M., Xu Y., Li P., Li Z., Sui Z., Corke H. Thermal processing of rice grains affects the physical properties of their pregelatinised rice flours. Int. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2020;55:1375–1385. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.14417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ratnayake W.S., Jackson D.S. A new insight into the gelatinization process of native starches. Carbohy. Polym. 2007;67:511–529. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2006.06.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chung C., Degner B., McClements D.J. Physicochemical characteristics of mixed colloidal dispersions: Models for foods containing fat and starch. Food Hydrocol. 2013;30:281–291. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2012.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kentish, S., Ashokkumar, M. The physical and chemical effects of ultrasound, in: H. Feng, G. Barbosa-Canovas, J. Weiss (Eds.), Ultrasound Technologies for Food and Bioprocessing, Springer New York, New York, NY, 2011: pp. 1–12.

- 39.Bonto A.P., Tiozon R.N., Jr, Sreenivasulu N., Camacho D.H. Impact of ultrasonic treatment on rice starch and grain functional properties: A review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;71 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lai H.-M. Effects of hydrothermal treatment on the physicochemical properties of pregelatinized rice flour. Food Chem. 2001;72:455–463. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(00)00261-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thirunavookarasu N., Kumar S., Anandharaj A., Rawson A. Enhancing functional properties of soy protein isolate—rice starch complex using ultrasonication and its characterization. Food Biopro. Technol. 2023 doi: 10.1007/s11947-023-03280-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vargas S.A., Delgado-Macuil R.J., Ruiz-Espinosa H., Rojas-López M., Amador-Espejo G.G. High-intensity ultrasound pretreatment influence on whey protein isolate and its use on complex coacervation with kappa carrageenan: Evaluation of selected functional properties. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;70 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Niu L., Wu L., Xiao J. Inhibition of gelatinized rice starch retrogradation by rice bran protein hydrolysates. Carbohy. Polym. 2017;175:311–319. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.07.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matusiak J., Grządka E. Stability of colloidal systems-a review of the stability measurements methods. Annales Universitatis Mariae Curie-Sklodowska, Sectio AA–Chemia. 2017;72:33. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nafiunisa A., Aryanti N., Wardhani D.H. Ultrasonic preparation of olive oil pickering emulsion stabilized by modified starch. Acta Scientiarum Polonorum Technologia Alimentaria. 2022;21:183–194. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakorn K.N., Tongdang T., Sirivongpaisal P. Crystallinity and rheological properties of pregelatinized rice starches differing in amylose content. Starch-Stärke. 2009;61:101–108. doi: 10.1002/star.200800008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lai H., Cheng H. Properties of pregelatinized rice flour made by hot air or gum puffing. Int. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2004;39:201–212. doi: 10.1046/j.0950-5423.2003.00761.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bao J. Accurate measurement of pasting temperature by the rapid visco-analyser: A case study using rice flour. Rice Sci. 2008;15:69–72. doi: 10.1016/S1672-6308(08)60022-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu E., Wu Z., Wang F., Li H., Xu X., Jin Z., Jiao A. Impact of high-shear extrusion combined with enzymatic hydrolysis on rice properties and chinese rice wine fermentation. Food Biopro. Technol. 2015;8:589–604. doi: 10.1007/s11947-014-1429-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Puncha-arnon S., Uttapap D. Rice starch vs. rice flour: Differences in their properties when modified by heat–moisture treatment. Carbohy. Polym. 2013;91:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bhandari P.N., Singhal R.S., Kale D.D. Effect of succinylation on the rheological profile of starch pastes. Carbohy. Polym. 2002;47:365–371. doi: 10.1016/S0144-8617(01)00215-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Silva K., Machado A., Cardoso C., Silva F., Freitas F. Rheological behavior of plant-based beverages. Food Sci. Technol. 2019;40:258–263. doi: 10.1590/fst.09219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cheetham N.W., Tao L. Variation in crystalline type with amylose content in maize starch granules: an X-ray powder diffraction study. Carbohy. Polym. 1998;36:277–284. doi: 10.1016/S0144-8617(98)00007-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carmona-García R., Bello-Pérez L.A., Aguirre-Cruz A., Aparicio-Saguilán A., Hernández-Torres J., Alvarez-Ramirez J. Effect of ultrasonic treatment on the morphological, physicochemical, functional, and rheological properties of starches with different granule size: Ultrasonic treatment of large and small starch granules. Starch-Stärke. 2016;68:972–979. doi: 10.1002/star.201600019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Flores-Silva P.C., Roldan-Cruz C.A., Chavez-Esquivel G., Vernon-Carter E.J., Bello-Perez L.A., Alvarez-Ramirez J. In vitro digestibility of ultrasound-treated corn starch: In vitro digestibility of ultrasound-treated corn starch. Starch-Stärke. 2017;69:1700040. doi: 10.1002/star.201700040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Luo Z., Fu X., He X., Luo F., Gao Q., Yu S. Effect of ultrasonic treatment on the physicochemical properties of maize starches differing in amylose content. Starch-Stärke. 2008;60:646–653. doi: 10.1002/star.200800014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kaur H., Gill B.S. Effect of high-intensity ultrasound treatment on nutritional, rheological and structural properties of starches obtained from different cereals. Internat. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019;126:367–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.12.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fu Z., Wang L., Li D., Zhou Y., Adhikari B. The effect of partial gelatinization of corn starch on its retrogradation. Carbohy. Polym. 2013;97:512–517. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.04.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Van Soest J.J., Vliegenthart J.F. Crystallinity in starch plastics: consequences for material properties. Tren. Biotech. 1997;15:208–213. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(97)01021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sevenou O., Hill S.E., Farhat I.A., Mitchell J.R. Organisation of the external region of the starch granule as determined by infrared spectroscopy. Internat. J. Biol. Macromol. 2002;31:79–85. doi: 10.1016/S0141-8130(02)00067-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Monroy Y., Rivero S., García M.A. Microstructural and techno-functional properties of cassava starch modified by ultrasound. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;42:795–804. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vela A.J., Villanueva M., Ronda F. Low-frequency ultrasonication modulates the impact of annealing on physicochemical and functional properties of rice flour. Food Hydrocol. 2021;120 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2021.106933. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hu W.-X., Chen J., Zhao J.-W., Chen L., Wang Y.-H. Effect of the addition of modified starch on gelatinization and gelation properties of rice flour. Internat. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;153:26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]