Abstract

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is a highly successful operation performed worldwide in increasing numbers for a wide range of indications. There has been a corresponding rise in the incidence of periprosthetic joint infection of the hip (PJIH), which is a devastating complication.

There is a significant variation in the definition, diagnosis and management of PJIH largely due to a lack of high-level evidence. The current standard of practice is largely based on cohort studies from high-volume centres, consensus publications amongst subject experts, and national guidance. This review describes our philosophy and practical approach of managing PJIH at a regional tertiary high-volume joint replacement centre.

Keywords: Periprosthetic hip infection, PJI, Total hip arthroplasty, THA, Hip, Antibiotics

1. Introduction

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is one of the most successful operations for end-stage conditions of the hip and has been recognised as the ‘Operation of the Century’.1 Nonetheless periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) remains a devastating complication for the patient and the surgeon. It is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, multiple surgeries, prolonged inpatient stay, and often poor functional outcomes.2 The demand for THA has increased by over 22 % in the last decade and is estimated to increase to 40 % by 2060.3 Current literature suggests the incidence of PJI of the hip (PJIH) at 1–2%.4 With the cost of management being more than five-fold that the cost of a primary THA, the increasing numbers of PJIH represent a significant expenditure within the health economy which has been estimated to be up to £30,000 for the UK's National Health Service.5 Despite the ever-increasing burden and challenges of PJIH there is a lack of consensus management with conflicting guidance for the definitions and diagnosis of infection, with no single test achieving 100 % sensitivity or specificity.6, 7, 8

The gold-standard two-stage revision procedure has been challenged by the widespread adoption of a single-stage procedure, which has expanded from a single-centre experience.9,10 In addition, the role of debridement, implant retention and long-term antibiotic suppression has been investigated by many centres for increasing indications causing a departure from guideline-recommended treatments.11, 12, 13 Consequently, morbidity and mortality outcomes following PJI treatment have not meaningfully improved.14, 15, 16 The body of guidance and recommendations are often proposed by high-volume revision units with high level of surgical expertise. Following on from the seminal work of Sir John Charnley who pioneered the modern low-friction arthroplasty, we perform amongst the highest volume primary and revision arthroplasties in the UK at Wrightington Hospital, and as such, has been designated a ‘Centre of Excellence’ for orthopaedic surgery.17 In this review we describe a pragmatic and practical approach to the prevention, diagnosis and management of PJIH from our regional UK based arthroplasty centre.

2. Definition and classification

There is no “gold standard” definition or diagnostic test for PJI.18 The updated Musculoskeletal Infection Society (MSIS) diagnostic criteria do not find wide support amongst subject experts across the world due to the potential to underdiagnose a wider spectrum of infections.19 There is now a greater understanding of low-grade infection and how inappropriate treatment can significantly impact outcomes. The newer EBJIS criteria (Table 1), now being adopted across the UK (recommended by British Hip Society Surgical Standard guidelines20) and most European centres, define PJI in a pragmatic, three-level approach with ‘infection confirmed’, ‘infection likely’ and ‘infection unlikely’.21 The EBJIS definition has been shown to significantly reduce the number of uncertain diagnoses, and is better at ruling out PJI with an ‘infection unlikely’ result (sensitivity 89 %) compared to existing definitions.22

Table 1.

EBJIS criteria (adapted from McNally et al.21) for the diagnosis of suspected prosthetic joint infection. CFU, colony forming unit; HPF, high power field; PMN, polymorphonuclear; WBC, white blood cell.

| Infection Unlikely (all findings negative) | Infection Likely (2 positive findings) | Infection Confirmed (any positive finding) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical and blood workup | |||

| Clinical features | Clear alternative reason for implant dysfunction |

|

Sinus tract communicating with the joint or visualisation of the prosthesis |

| C-reactive protein | >10 mg/l | ||

| Synovial fluid cytological analysis | |||

| Leucocyte count (cells/μm) | ≤1500 | >1500 | >3000 |

| PMN (%) | ≤65 % | >65 % | >80 % |

| Synovial fluid biomarkers | |||

| Alpha-defensin | Positive | ||

| Microbiology | |||

| Aspiration fluid | Positive culture | ||

| Intraoperative | All cultures negative | Single positive culture | ≥2 positive cultures of same organism |

| Sonication | No growth | >1 CFU/ml | >50 CFU/ml |

| Histology | |||

| HPF (400x magnification) | Negative | ≥5 neutrophils in 1 HPF | ≥5 neutrophils in 5 HPF and/or Visible microorganisms |

| Others | |||

| Nuclear imaging | Negative 3 phase bone scan | Positive WBC scintigraphy | |

3. Preoperative infection prevention

At Wrightington Hospital we utilise a three-stage approach to preventing PJIH. Preoperatively, our ‘preop team’ optimise modifiable risk factors, particularly poor glycaemic control (target HbA1c < 8.5 %), smoking cessation, correction of anaemia, malnutrition and obesity, all of which are recognised risk factors for PJIH.23 Broad spectrum antibiotics are discontinued at least 2 weeks before any aspiration or revision procedure. Patients are thoroughly investigated and medically optimised for anaesthetic fitness (e.g. echocardiogram, pulmonary function, managing anticoagulation, pacemakers etc). Decolonisation with nasal mupirocin and chlorhexidine skin wash is completed by all patients. Foci of infection elsewhere (skin ulcers, poor dental hygiene) are addressed and rectified. Surgery is deferred until systemic infection (respiratory or urinary tract infections) has been appropriately treated.

4. Immediate perioperative care

Surgical site hair removal is performed in the anaesthetic room with clippers immediately before skin preparation. Prophylactic intravenous antibiotics are administered within 30 min of skin incision followed by 2 postoperative doses. We then perform the first skin preparation in the anaesthetic room (as described traditionally by Sir John Charnley, who pioneered the “double prepping process at Wrightington hospital along with the ‘Low Frictional Torque Arthroplasty’ in the 1960s) using an aseptic no-touch technique with alcohol-based povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine solutions. Not only does this provide the most rapid reduction of bacterial count but also improves skin adhesion to surgical and incise drapes.24 Chlorhexidine (bactericidal and bacteriostatic actions), combined with alcohol is effective against aerobes, anaerobes, yeasts and fungi. Iodine, or betadine, (with alcohol) is bactericidal and has broad antisepsis against fungi and viruses and is also less likely to cause skin irritation or blistering compared with chlorhexidine. It is commercially polymerised with povidone to prolong its persistence on skin.25 A second “skin prep” is then performed in theatre with application of impervious and iodophor-impregnated incise drapes. Wound edges are protected with chlorhexidine-impregnated moist swabs.

The world's first clean-air operating theatre was established at our unit in the 1960s (Fig. 1) the benefits of which were further cemented by the Medical Research Council's landmark paper on reducing deep infection in 1982.26 We perform all arthroplasty in ultra-clean air, exponential laminar-flow operating theatres in both traditional and modern barn-style suites (Fig. 2). The surgical and scrub team within the sterile field don a positive air-pressure toga without body exhaust and only necessary personnel are present to reduce entrainment and disturbances to air flow.

Fig. 1.

The world's first clean air operating theatre designed and used by Sir John Charnley at Wrightington Hospital, used from 1965 to 1997.

Fig. 2.

Perspective view of our ultra-clean air exponential laminar-flow theatre enclosure in a barn style suite at Wrightington Hospital. Scrub personnel demonstrating full-length positive-pressure toga-style surgical gowns.

5. Presentation of PJIH

Patients presenting with a painful THA are reviewed urgently in the outpatient clinic and undergo a triple assessment of history, clinical examination and outpatient investigations. A thorough history includes location of primary arthroplasty, and implant details (including operative records and implant labels from the National Joint Registry, NJR). It includes history of post-surgical wound healing problems (even if trivial), any period of sepsis or significant infection (local or systemic) since implantation, or history of trauma. As is well-known there is a lifetime risk of infection by haematogenous seeding from a remote sepsis, such as respiratory, urinary tract and dental infections.

6. Investigations

Our approach to diagnostics begins with blood tests (full blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, ESR, and CRP), and clinical photography if there is a sinus. Serial measurements are more helpful than isolated single levels. We find these tests useful due to their relatively low cost, ease of availability and usefulness in ruling out infection in non-PJIH cases.27,28 Initial imaging includes an up to date plain film radiograph of the hips (AP and lateral) and compared with previous studies to assess for serial changes, particularly peri-implant lucency, subsidence, osteolysis and periosteal reaction.29 In some cases additional CT (computed tomography) is helpful is assessing bone loss with up to 87 % diagnostic accuracy. In selected cases, we find magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) helpful in assessing soft tissue extension of infection such as periprosthetic muscle oedema or fluid collection and demonstrates 78–95 % sensitivity and 86–97 % specificity depending on the signs considered for diagnosis.30,31

Where investigations are equivocal, or if CT/MRI is unable to rule-out infection, we perform nuclear imaging (SPECT/CT, or PET/MRI bone scan) which can increase overall diagnostic accuracy by up to 98 % for PJIH and has the added benefit of defining the anatomic location and extent of the infective process. The performance of both SPECT/CT and PET/MRI demonstrate 100 % sensitivity and 97 % specificity.32 If performed soon after surgery however, these investigations have a lower specificity for diagnosing PJI. Whilst a negative scan can exclude PJI (NPV 92–100 %), a positive result has to be interpreted with caution within the first two years following surgery.30,33

7. Aspiration

Identification of the organism via a percutaneous joint fluid aspirate or tissue specimen is an important investigation for diagnosing acute and chronic PJIH which we perform for all cases. All aspirations are performed under strict aseptic conditions with fluoroscopic guidance either in the operating theatre or the imaging suite. Antibiotics are stopped for at least 2 weeks prior to aspiration to reduce the risk of a culture-negative result, except in cases of acute infection in a systemically unwell patient. The true number of culture-negative infections are difficult to determine although recent evidence suggests rates between 9 and 42 %.34

Samples are collected aseptically in a sterile pot and sent for microscopy and culture, or in blood culture bottles as it helps improve growth and detection of biofilm-associated infections where organism number may be low. Microscopy includes Gram stain, differential cell count and crystal analysis. Synovial fluid should be cultured for both aerobic and anaerobic organisms and a small volume is incubated in enrichment broth. Direct culture and blood culture bottles are incubated for 5 days, and enrichment broth for 7. Occasionally the incubation period is extended up to 14 days in the setting of chronic PJI when there has been no previous culture results. Mycobacterial and fungal cultures are performed for chronic, indolent, or refractory infection; previously culture-negative infection; or immunosuppression.

Peri-prosthetic tissue biopsies are routinely collected in theatre during revision. We recommend multiple periprosthetic tissue samples (ideally five, to minimise sampling error and optimise specificity) are obtained with different instruments and put into separate sterile containers to prevent cross-contamination. Cultures may be falsely negative with swabs or insufficient tissue. Pre-treatment of tissue biopsy samples (particularly in culture-negative or in chronic or atypical PJI) has also been recommended to help increase microbial yield by homogenisation which involves specimen collection in theatres and transfer into-leak proof containers with 10 glass beads and 5 ml Ringer's or normal saline. Cultures have a sensitivity of up to 75 % and specificity of 95 %, which can diminish by transport time and temperature. This can be mitigated by using paediatric blood culture bottles.35

We also perform histology for quantitative assessment of neutrophil infiltrates. Molecular testing (16S PCR and 18S PCR) are performed in the setting of culture negative PJI if the index of suspicion for infection is high and for isolating suspected atypical bacteria, fungal, yeast or culture-negative PJIH as PCR is less affected by prior use of antibiotics. We have not found routine alpha-defensin analysis to be an effective screening for PJIH due to low sensitivity (54 %) and cost.36

8. Regional revision hub

There has been a significant move in the UK for management of PJI to be conducted in specialist centres as part of a hub-and-spoke model in line with British Hip Society and Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT) guidance.37 This has led to a rapid development and evolution of a multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach to complex revision hip arthroplasty and PJIH. It provides governance, helps the surgeon with decision making and onward referral if more expertise is required. The MDT approach has reduced revision rates, improved cost-effectiveness and avoids improper management with the philosophy of providing ‘the right patient with the right treatment at the right time’20

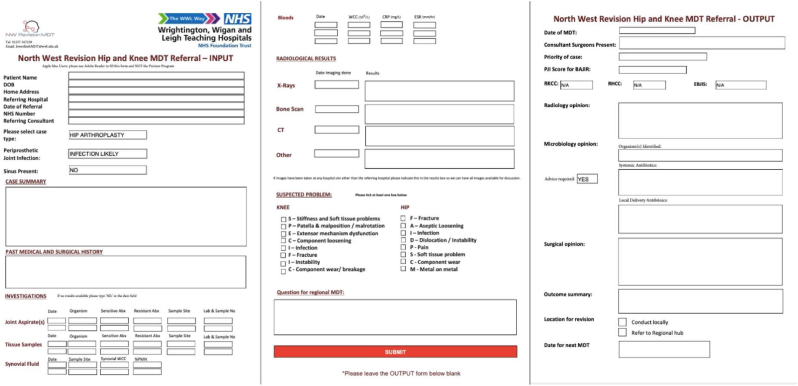

Our MDT is comprised of arthroplasty surgeons, microbiologists and radiologists with revision experience, and access to pharmacists, plastic and vascular surgeons. The weekly meeting follows a hybrid model with the majority of members attending in-person and virtually. The referring surgeon completes a standardised patient referral proforma (Fig. 3) and presents their case. The MDT reviews the available imaging and microbiology in order to classify the case and identify the organism. The MDT proposes a consensus surgical and antimicrobial treatment strategy. The cases are graded ‘R1’, ‘R2’ or ‘R3’ according to the Revision Hip Complexity Classification. Management recommendations consist of either local treatment or onward referral to the hub if the complexity warrants.38 Outcome data are submitted to the NJR and the Bone And Joint Infection Registry (BAJIR). In complex cases we often operate together with an experienced colleague which in our experience improves patient safety, intra-operative decision making, surgical time and eventually outcomes.

Fig. 3.

Standardised MDT referral proforma. Pages 1–2 are completed by the referrer to capture patient demographics and key clinical, serological and radiological findings. Meeting outcomes and recommendations are recorded on page 3.

8.1. Operative management

Our treatment strategies for PJIH are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of patient variables and our treatment options after consensus decision by the multidisciplinary revision arthroplasty team. DAIR, debridement antibiotics and implant retention; PJIH, periprosthetic joint infection of the hip.

| Variable | DAIR | Single stage | Two-stage | Pseudoarthrosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <6 weeks since implantation | ✓ | |||

| Patient fitness | Fit | Fit | Comorbidities | Comorbidities |

| Previous revision | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Recurrent PJIH | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Atypical organism | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Culture-negative | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Sinus present | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

8.2. DAIR (debridement, antibiotics and implant retention)

We would attempt DAIR in acute infections, i.e. within 4–6 weeks of the index surgery and in the presence of a well-fixed prosthesis. It is also performed for acutely presenting but late haematogenous infections. Undertaking a DAIR before the formation of a mature biofilm is critical to a successful outcome. Colonies form in the first few hours and mature by 4–6 weeks after inoculation.39 Contraindications include an unstable implant or periprosthetic fracture, and infections due to atypical, multi-drug resistant (relative contraindication) or fungal infections. We rarely perform a DAIR more than once, unless recommended by the MDT.

Thorough, systematic debridement and irrigation in a layer-by-layer approach is paramount. The existing hip wound is opened along its length, extending proximally or distally as required. We excise the wound margin along with any sinus. Sinuses are explored and curetted with excision of the deep tract. The subcutaneous fat is debrided and curetted of any devitalised tissue before copious pulse lavage with normal saline. Next, the fascia is divided and any pre-existing suture material is removed.

We undertake a thorough debridement and find the a “tricyclic debridement” concept developed by Morgan-Jones very useful to standardise the process.40 This involves a methodically performed surgical, mechanical and chemical debridement. Surgical debridement involves a complete synovectomy, removal of membrane and excision of intracapsular scar tissue by sharp dissection which also helps facilitate prosthetic hip dislocation. With the hip dislocated, all modular components (such as liner, head and modular neck) are carefully removed without damaging the indwelling stem or acetabular components. This is followed by mechanical debridement in a compartmental manner with any surfaces and planes cleared of devitalised tissue using curettage and rongeurs. Normal saline under powered pulse lavage is used to clear away debris and disrupt the membrane and biofilm. This cycle of curettage and pulse lavage is repeated multiple times until good clearance is obtained. We also find hydrogen peroxide useful as a desloughing agent.

The chemical debridement is performed by soaking the surgical field with an antimicrobial agent which creates a hostile environment for pathogens. We use 0.05 % chlorhexidine or 1 % povidone-iodine solution to soak the wound for 10–20 min during which time fresh gloves are donned and a new surgical drape is applied over the existing field. The antimicrobial is washed off with pulsed lavage normal saline before inserting new modular components. In most cases, we use 10–20 cc bio-absorbable calcium sulphate (STIMULAN®, Biocomposites Ltd., UK) with gentamycin and vancomycin (as the recommended antibiotic in the MDT) for additional high dose local antibiotic delivery in the deep planes. There is a known risk of wound discharge associated with calcium sulphate of up to 4 % particularly if greater than 30 cc volume is used or if placed superficially.41 The hip is reduced and closed in a standard fashion without drains where possible.

Postoperatively patients are commenced on broad-spectrum intravenous and oral antibiotics (teicoplanin and ciprofloxacin) for durations ranging from 2 to 6 weeks or longer if the organism is rifampicin resistant or for non-staphylococcal species, based on our institutional policy.42 Antibiotic choice and duration are tailored to each patient depending on culture results and guidance from our microbiologist. The step-down from intravenous to oral regimens is usually determined by improving clinical signs and serology. We monitor patients closely in the outpatient clinic and undergo clinical assessment, radiography and blood tests at each review.

8.3. Single-stage revision

Although two-stage revision has been the gold-standard treatment for PJIH for many decades, there is recent evidence to suggest that overall morbidity, reinfection rates and functional outcome may not differ between single and two-stage revision.43, 44, 45 Better quality evidence is still however required to categorically establish if single-stage revision produces better functional outcomes and has reduced morbidity, length of stay and healthcare costs.

Single-stage revision for PJIH is gaining popularity and we use it for the appropriately elected patients. The Endo-Klinik (Hamburg, Germany) have pioneered single-stage revision for increasing indications (including fungal and culture-negative infection) with excellent outcomes in their cohorts at up to 24-years follow-up.46, 47, 48 However they described suboptimal results with single-stage for streptococcal and enterococcal infections for which they recommend two-stage revision.49,50 While desirable, we have not found that identification of the infective organism before surgery influences outcomes. We continue to perform single-stage for PJIH for most cases, including infection of unknown organisms with good results.51 Our other indications for single-stage, after appropriat e MDT consensus, include a viable soft tissue envelope, adequate bone stock to support a prosthesis and a good patient host (overall medical status and fitness). We do not find the presence of a discharging sinus to be a contraindication for a single-stage and have previously reported excellent outcomes for this patient group from our unit.52

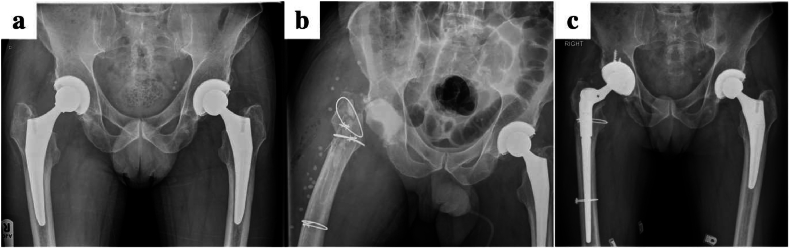

Our initial approach and debridement is as described before. Specimens are taken before any systemic antibiotics are administered. The femoral component and all remaining cement is carefully removed from the canal with specialist manual, mechanical or ultrasonic instruments. The canal is reamed over a flexible guide wire to remove all remaining membrane and neo-cortex. This facilitates a better exposure of the acetabular component which is safely extracted including all cement and a thorough debridement is repeated. During the chemical debridement all contaminated instruments and trays are removed, gloves and drapes changed, and new sterile drapes applied over the operative field. Joint reconstruction is based on surgical plans and implants recommended by the Revision MDT. Bioabsorbable STIMULAN® pellets are routinely used for local antibiotic delivery within the deeper planes, and use the pellets as a cement plug in the femoral intramedullary canal (Fig. 4). The antibiotic regimen is tailored dependent on specimen culture. The same principles apply for removal of uncemented prosthesis safely using the appropriate instruments. We prefer to avoid extended trochanteric osteotomies as far as possible.

Fig. 4.

Pre and postoperative radiographs of a patient treated for S.aureus periprosthetic infection with a single stage revision. STIMULAN can be seen as a cement restrictor in the intramedullary canal.

8.4. Two-stage revision

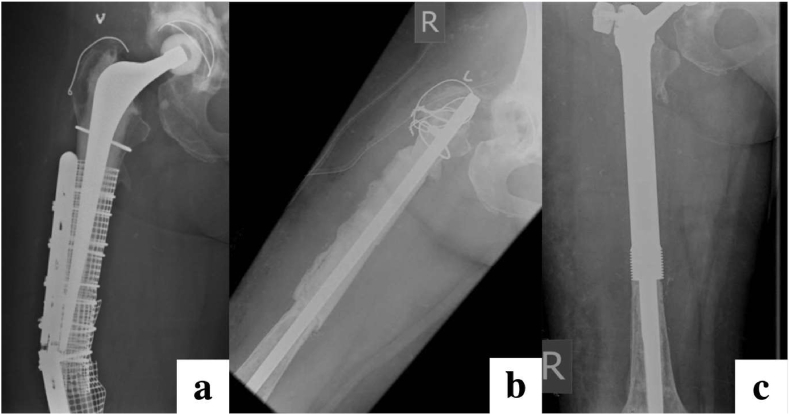

Two-stage revision remains the gold-standard for PJI management. Our indications include the multiply-revised hip, atypical or fungal infections, or significant soft tissue compromise. In the first stage we explant all prosthetic material with tricyclic debridement, femoral/acetabular reaming and specimen sampling akin to our single-stage protocol (Fig. 5). Targeted local antibiotic delivery is administered with absorbable and non-absorbable methods such as antibiotic-impregnated cement in the form of beads or a spacer. In our experience the decision whether to use a cement spacer, intramedullary nail or articulating prosthesis as a spacer depends on the patient's baseline mobility, soft tissue envelope and bone quality. A cohort of patients treated at our unit without a cement spacer, however, are still able to transfer and mobilise using a frame without significant functional impairment which is the preferred option.

Fig. 5.

Radiographs demonstrating delayed-onset right hip PJI due to atypical pathogen (a) treated with two-stage revision. Antibiotic-loaded calcium sulphate beads and a cement block spacer can be appreciated in the first-stage (b) followed by definitive implantation of a cementless revision prosthesis at second-stage (c).

There are two approaches to a ‘hip spacer’. Non-articulating block spacers are a handmade ball of antibiotic-loaded cement to void-fill the acetabulum and remain an effective option. In contrast, articulating spacers are usually injection-moulded from cement (some are a composite of polyethylene and metal) and attempt to preserve the joint space and maintain range-of-motion though its use is falling out of favour in the UK and at our unit. There is a known risk of increased pain, bone erosion, spacer fracture and dislocation owing to the mechanical and surface properties of cement. There are also concerns with the degree of antibiotic elution due to the low surface-area to volume ratio and further risk of biofilm development once the antibiotic has been depleted. Overall we avoid the use of articulating hip spacers at our unit. In cases where there are concerns over the fragility of the proximal femur without a prosthesis following a first-stage (i.e. due to severe bone loss or osteopenia), we elect to perform a ‘nail cementoplasty’. This involves loosely cementing a narrow-diameter intramedullary nail into the debrided and reamed femur for structural stability (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Radiographs of an elderly patient presenting with an infected periprosthetic fracture (a) undergoing two-stage revision with an antibiotic cement-coated nail ‘cementoplasty’ at first-stage (b), followed definitive proximal femoral replacement at second-stage.(c).

The Exeter unit developed the CUMARS (CUstom Made ARticulating Spacer, or ‘Kiwi’ hip) technique whereby a primary stem and polyethylene cup are ‘loosely’ cemented into place. They demonstrated improved weight bearing and mobility rates and in some patients, postponing the second stage indefinitely with retention of the CUMARS as the final definitive prosthesis.53 The technique then evolved into using a well-cemented prosthesis. Many units including ours in the UK have adopted this technique into a so-called ‘1.5 stage revision’ which can allow the patient to ambulate indefinitely if necessary, but also can still be revised into a staged philosophy if required. Our indications include high-risk patients who would benefit from a shorter anaesthetic time, patients who would otherwise be unable to tolerate mobility or nursing following a first-stage and those with an overall poor prognosis or palliative care.

The duration of systemic antibiotic treatment duration following first-stage revision hip is a contentious issue. The standard practice at our unit is to administer targeted systemic antibiotic for 6 weeks to 3 months following first-stage and subsequent second-stage revision, with longer durations for certain microorganisms and fungal infections based on the advice obtained from our specialist and experienced microbiologist. Many studies have demonstrated the non-inferiority of ‘short’ course (2–6 weeks) versus prolonged course (6–12 weeks) of antibiotics.54,55 Furthermore the Sheffield group have published excellent results for two-stage revisions using antibiotic cement beads in the first stage without prolonged (less than 48 h) systemic antibiotics.56 Our philosophy, in line with other units, advocates that the key to successful eradication of infection depends on aggressive surgical debridement.

The second-stage involves definitive implantation, which occurs approximately 6 weeks to 6 months (3 months on average) following the first-stage. We prefer to establish good clinical improvement confirmed by normalisation of inflammatory parameters prior to definitive implantation. A further pre-operative aspirate is selectively performed if infection clearance is in doubt. The skin, soft tissues and surgical bed should be viable and free from any visible features of infection or necrosis. We routinely perform repeat intraoperative sampling to check for microorganisms. Implant fixation is dependent on the host bone stock though cemented fixation combined with impaction bone grafting after containment of acetabular segmental defects is our preference.

Femoral reconstruction options are chosen based on available bone stock and quality or surgeon preference and experience. We often use proximal femoral replacement as suitable and relatively straightforward reconstruction option and to avoid a prolonged surgical time, particularly in frail elderly patients with multiple comorbidities undergoing second-stage with poor proximal bone stock (Fig. 6). Uncemented reconstruction is also a viable option. We add additional antibiotics to the bone cement along with STIMULAN®. Systemic antibiotics are administered for 6 weeks even if second-stage cultures are negative, or longer if other organisms are identified from sampling during the second stage, though this is rare in our practice.

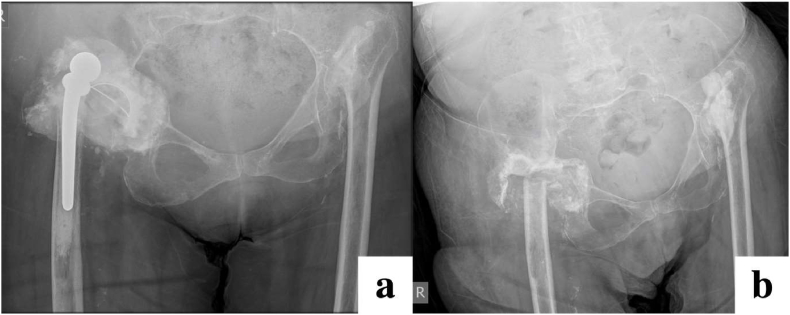

8.5. Permanent excision arthroplasty - pseudoarthrosis

Patients who have failed two-stage revision still have the option of DAIR, repeat staged revision or antibiotic suppression. Onward management depends on comorbidities, integrity of bone stock, soft tissues and the patient's desire to undergo further surgeries.57 A pseudoarthrosis, (resection arthroplasty, or Girdlestone procedure) is our preferred salvage method for the failing, recalcitrantly infected, multiply revised hip with poor soft tissue where reconstruction is unrealistic (Fig. 7). Patients with a pseudoarthrosis are surprisingly able to ambulate reasonably well in most cases, as the proximal femur articulates within the acetabulum and the surrounding soft tissues contract forming a relatively stable pseudo-joint over time. Echoing the literature, our experience of pseudoarthrosis has shown a high rate of pain relief and infection control.58 In some rare cases, cure of the infection is unachievable either due high-risk comorbidities precluding surgery, or in the context of a highly-resistant microorganism despite revision surgery and well-fixed implants, life-long antibiotic suppression and sinus management would be recommended. In our experience such patients have good levels of function for many years on life-long oral antibiotics. Though some units may opt to discharge this patient group to ‘patient-initiated-follow-up’ it is still our policy to keep these patients under outpatient clinical and radiographic review, with sinus care performed in the community as needed.

Fig. 7.

Radiographs demonstrating persistent chronic infection and prosthetic right hip dislocation (a), treated with pseudoarthrosis (b). Patient had also previously undergone pseudoarthrosis of the left hip for the same indication.

9. Limitations

We acknowledge several limitations in this review. Firstly, we present a single-centre experience from a specialist orthopaedic tertiary referral centre with a large surgeon body who routinely undertake a high-volume of complex revision cases. Secondly, the demographic of patients presenting to our unit in the UK may limit the applicability of our recommendations to other countries. There is also a debate on what is defined as ‘infection-free’. It is our standard practice to monitor patients clinically and serologically in the postoperative period. Some units recommend to perform routine joint aspiration to confirm the eradication of infection as a determinant of successful treatment, though this is not our practice, in line with Delphi-based consensus.59

10. Future direction of research

Next generation sequencing (NGS) to detect microorganisms by amplification of microbial DNA has shown promising results in otherwise culture-negative specimens with high sensitivity and specificity. However their limitations lie in the high cost, special training and low availability of the technology.60 Newer antibiotics such as dalbavancin have been developed which have demonstrated improved penetration into bones and joints and have been used in selected cases by MDT guidance at our unit.61 Further research is critical in antibiotic and resistance mechanisms as it is estimated that by 2050, antibiotic resistant infections may cause ten million deaths a year.62 Immunotherapy, monoclonal antibodies and photodynamic therapy also show promising results particularly against biofilm formation though similarly at present their use is not mainstream due to high cost and availability.63 Bacteriophage-derived proteins may play a significant role in the future treatment of PJIH. In vitro studies have shown that in isolation, phages reduce biofilm formation as well as target non-biofilm bacteria. They also demonstrate a synergism with vancomycin by reducing bacterial load in periprosthetic tissues and on implant surfaces.64

11. Conclusion

Whilst stemming from a single-centre experience, our multidisciplinary framework and shared decision-making using a standardised approach is in line with the majority of UK and European revision centres with satisfactory and comparable outcomes, which may be helpful to clinicians across the globe. Collaborative management of PJIH is the cornerstone for successful treatment with current diagnostic and treatment strategies, though the breadth of clinical manifestations and culture-negative infection remains a challenge. Nonetheless, the successful eradication of infection is underpinned by performing a thorough and systematic surgical, mechanical and chemical debridement. Attention should be given to upcoming diagnostic biomarkers and antimicrobials, which will play a greater role in screening and treatment.

Author contributions

Rajpreet Sahemey, Mohammed As-Sultany, Chinari Pradeep Kumar Subudhi and Nikhil Shah: manuscript writing, proof reading and preparation of figures. Henry Wynn Jones, Amol Chitre and Sunil Panchani: preparation of manuscript and proof reading.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Rajpreet Sahemey, Email: rajsahemey@gmail.com.

Nikhil Shah, Email: Nikhil.shah@wwl.nhs.uk.

References

- 1.Learmonth I.D., Young C., Rorabeck C. The operation of the century: total hip replacement. Lancet. 2007;370(9597):1508–1519. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60457-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore A.J., Blom A.W., Whitehouse M.R., Gooberman-Hill R. Deep prosthetic joint infection: a qualitative study of the impact on patients and their experiences of revision surgery. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matharu G., Culliford D., Blom A., Judge A. Projections for primary hip and knee replacement surgery up to the year 2060: an analysis based on data from the National Joint Registry for England, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2022;104(6):443–448. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2021.0206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garfield K., Noble S., Lenguerrand E., et al. What are the inpatient and day case costs following primary total hip replacement of patients treated for prosthetic joint infection: a matched cohort study using linked data from the National Joint Registry and Hospital Episode Statistics. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):335. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01803-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kallala R.F., Vanhegan I.S., Ibrahim M.S., Sarmah S., Haddad F.S. Financial analysis of revision knee surgery based on NHS tariffs and hospital costs: does it pay to provide a revision service? The Bone & Joint Journal. 2015;97-B(2):197–201. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.97B2.33707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luppi V., Regis D., Sandri A., Magnan B. Diagnosis of periprosthetic hip infection: a clinical update. Acta Biomed. 2023;94(S2) doi: 10.23750/abm.v94iS2.13792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shahi A., Parvizi J. The role of biomarkers in the diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection. EFORT Open Rev. 2016;1(7):275–278. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.1.160019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zmistowski B., Della Valle C., Bauer T.W., et al. Diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(2 Suppl):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zahar A., Kendoff D.O., Klatte T.O., Gehrke T.A. Can good infection control Be obtained in one-stage exchange of the infected TKA to a rotating hinge design? 10-year results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(1):81–87. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4408-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zahar A., Klaber I., Gerken A.M., et al. Ten-year results following one-stage septic hip exchange in the management of periprosthetic joint infection. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34(6):1221–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deng W., Li R., Shao H., Yu B., Chen J., Zhou Y. Comparison of the success rate after debridement, antibiotics and implant retention (DAIR) for periprosthetic joint infection among patients with or without a sinus tract. BMC Muscoskel Disord. 2021;22(1):895. doi: 10.1186/s12891-021-04756-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siqueira M.B.P., Saleh A., Klika A.K., et al. Chronic suppression of periprosthetic joint infections with oral antibiotics increases infection-free survivorship. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(15):1220–1232. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.00999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Armstrong M.D., Carli A.V., Abdelbary H., Poitras S., Lapner P., Beaulé P.E. Tertiary care centre adherence to unified guidelines for management of periprosthetic joint infections: a gap analysis. Can J Surg. 2018;61(1):34–41. doi: 10.1503/cjs.008617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Debbi E.M., Khilnani T., Gkiatas I., et al. Changing the definition of treatment success alters treatment outcomes in periprosthetic joint infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Jt Infect. 2024;9(2):127–136. doi: 10.5194/jbji-9-127-2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu C., Goswami K., Li W.T., et al. Is treatment of periprosthetic joint infection improving over time? J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(6):1696–1702.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.01.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goel R., Buckley P., Sterbis E., Parvizi J. Patients with infected total hip arthroplasty undergoing 2-stage exchange arthroplasty experience massive blood loss. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(11):3547–3550. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Joint Registry Hospital profile - NJR surgeon and hospital profile. https://surgeonprofile.njrcentre.org.uk/HospitalProfile?hospitalName=Wrightington/20Hospital

- 18.Fernández-Sampedro M., Fariñas-Alvarez C., Garces-Zarzalejo C., et al. Accuracy of different diagnostic tests for early, delayed and late prosthetic joint infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):592. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2693-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shohat N., Bauer T., Buttaro M., et al. Hip and knee section, what is the definition of a periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) of the knee and the hip? Can the same criteria be used for both joints?: proceedings of international consensus on orthopedic infections. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34(2S):S325–S327. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.British Hip Society Investigation & management of periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) https://britishhipsociety.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/BHSSS-PJI.pdf

- 21.McNally M., Sousa R., Wouthuyzen-Bakker M., et al. The EBJIS definition of periprosthetic joint infection. Bone Joint Lett J. 2021;103-B(1):18–25. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.103B1.BJJ-2020-1381.R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sousa R., Ribau A., Alfaro P., et al. The European Bone and Joint Infection Society definition of periprosthetic joint infection is meaningful in clinical practice: a multicentric validation study with comparison with previous definitions. Acta Orthop. 2023;94:8–18. doi: 10.2340/17453674.2023.5670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alamanda V.K., Springer B.D. The prevention of infection: 12 modifiable risk factors. Bone Joint Lett J. 2019;101-B(1_Supple_A):3–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.101B1.BJJ-2018-0233.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morrison T.N., Chen A.F., Taneja M., Küçükdurmaz F., Rothman R.H., Parvizi J. Single vs repeat surgical skin preparations for reducing surgical site infection after total joint arthroplasty: a prospective, randomized, double-blinded study. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(6):1289–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Letzelter J., Hill J.B., Hacquebord J. An overview of skin antiseptics used in orthopaedic surgery procedures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2019;27(16):599–606. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-18-00105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lidwell O.M., Lowbury E.J., Whyte W., Blowers R., Stanley S.J., Lowe D. Effect of ultraclean air in operating rooms on deep sepsis in the joint after total hip or knee replacement: a randomised study. Br Med J. 1982;285(6334):10–14. doi: 10.1136/bmj.285.6334.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Izakovicova P., Borens O., Trampuz A. Periprosthetic joint infection: current concepts and outlook. EFORT Open Rev. 2019;4(7):482–494. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.4.180092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zimmerli W., Trampuz A., Ochsner P.E. Prosthetic-joint infections. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(16):1645–1654. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McBride T.J., Prakash D. How to read a postoperative total hip replacement radiograph. Postgrad Med. 2011;87(1024):101–109. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2009.095620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romanò C.L., Petrosillo N., Argento G., et al. The role of imaging techniques to define a peri-prosthetic hip and knee joint infection: multidisciplinary consensus statements. J Clin Med. 2020;9(8):2548. doi: 10.3390/jcm9082548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galley J., Sutter R., Stern C., Filli L., Rahm S., Pfirrmann C.W.A. Diagnosis of periprosthetic hip joint infection using MRI with metal artifact reduction at 1.5 T. Radiology. 2020;296(1):98–108. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020191901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aleksyniene R., Iyer V., Bertelsen H.C., et al. The role of nuclear medicine imaging with 18F-FDG PET/CT, combined 111In-WBC/99mTc-nanocoll, and 99mTc-HDP SPECT/CT in the evaluation of patients with chronic problems after TKA or THA in a prospective study. Diagnostics. 2022;12(3):681. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12030681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Erba P.A., Glaudemans A.W.J.M., Veltman N.C., et al. Image acquisition and interpretation criteria for 99mTc-HMPAO-labelled white blood cell scintigraphy: results of a multicentre study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imag. 2014;41(4):615–623. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2631-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berbari E.F., Marculescu C., Sia I., et al. Culture-negative prosthetic joint infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(9):1113–1119. doi: 10.1086/522184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hughes J.G., Vetter E.A., Patel R., et al. Culture with BACTEC Peds Plus/F bottle compared with conventional methods for detection of bacteria in synovial fluid. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(12):4468–4471. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.12.4468-4471.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sigmund I.K., Holinka J., Gamper J., et al. Qualitative α-defensin test (Synovasure) for the diagnosis of periprosthetic infection in revision total joint arthroplasty. Bone Joint Lett J. 2017;99-B(1):66–72. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.99B1.BJJ-2016-0295.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Getting it right first time. GIRFT orthopaedics follow-up report. https://gettingitrightfirsttime.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/GIRFT-orthopaedics-follow-up-report-February-2020.pdf

- 38.Leong J.W.Y., Singhal R., Whitehouse M.R., et al. Development of the revision hip complexity classification using a modified Delphi technique. Bone Jt Open. 2022;3(5):423–431. doi: 10.1302/2633-1462.35.BJO-2022-0022.R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stewart P.S., Costerton J.W. Antibiotic resistance of bacteria in biofilms. Lancet. 2001;358(9276):135–138. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05321-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Razii N., Clutton J.M., Kakar R., Morgan-Jones R. Single-stage revision for the infected total knee arthroplasty. Bone Jt Open. 2021;2(5):305–313. doi: 10.1302/2633-1462.25.BJO-2020-0185.R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abosala A., Ali M. The use of calcium sulphate beads in periprosthetic joint infection, a systematic review. J Bone Jt Infect. 2020;5(1):43–49. doi: 10.7150/jbji.41743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Osmon D.R., Berbari E.F., Berendt A.R., et al. Executive summary: diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(1):1–10. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matthews P.C., Berendt A.R., McNally M.A., Byren I. Diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection. BMJ. 2009;338:b1773. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beswick A.D., Elvers K.T., Smith A.J., Gooberman-Hill R., Lovering A., Blom A.W. What is the evidence base to guide surgical treatment of infected hip prostheses? systematic review of longitudinal studies in unselected patients. BMC Med. 2012;10:18. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-10-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blom A.W., Lenguerrand E., Strange S., et al. Clinical and cost effectiveness of single stage compared with two stage revision for hip prosthetic joint infection (INFORM): pragmatic, parallel group, open label, randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2022;379 doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-071281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wolff M., Lausmann C., Gehrke T., Zahar A., Ohlmeier M., Citak M. Results at 10-24 years after single-stage revision arthroplasty of infected total hip arthroplasty in patients under 45 years of age. Hip Int. 2021;31(2):237–241. doi: 10.1177/1120700019888877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gehrke T., Kendoff D. Peri-prosthetic hip infections: in favour of one-stage. Hip Int. 2012;22(Suppl 8):S40–S45. doi: 10.5301/HIP.2012.9569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klatte T.O., Kendoff D., Kamath A.F., et al. Single-stage revision for fungal peri-prosthetic joint infection: a single-centre experience. Bone Joint Lett J. 2014;96-B(4):492–496. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.96B4.32179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abdelaziz H., Grüber H., Gehrke T., Salber J., Citak M. What are the factors associated with Re-revision after one-stage revision for periprosthetic joint infection of the hip? A case-control study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2019;477(10):2258–2263. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000000780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ohlmeier M., Jachczik I., Citak M., et al. High re-revision rate following one-stage exchange for streptococcal periprosthetic joint infection of the hip. Hip Int. 2022;32(4):488–492. doi: 10.1177/1120700021991467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Greenfield B.J., Jones H.W., Siney P.D., Kay P.R., Purbach B., Board T.N. Is preoperative identification of the infecting organism essential before single-stage revision hip arthroplasty for periprosthetic infection? J Arthroplasty. 2021;36(2):705–710. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Raut V.V., Siney P.D., Wroblewski B.M. One-stage revision of infected total hip replacements with discharging sinuses. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76(5):721–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsung J.D., Rohrsheim J.A.L., Whitehouse S.L., Wilson M.J., Howell J.R. Management of periprosthetic joint infection after total hip arthroplasty using a custom made articulating spacer (CUMARS); the Exeter experience. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(9):1813–1818. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kurapatti M., Oakley C., Singh V., Aggarwal V.K. Antibiotic therapy in 2-stage revision for periprosthetic joint infection: a systematic review. JBJS Rev. 2022;10(1) doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.21.00143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bernard L., Legout L., Zürcher-Pfund L., et al. Six weeks of antibiotic treatment is sufficient following surgery for septic arthroplasty. J Infect. 2010;61(2):125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Petrie M.J., Panchani S., Al-Einzy M., Partridge D., Harrison T.P., Stockley I. Systemic antibiotics are not required for successful two-stage revision hip arthroplasty. Bone Joint Lett J. 2023;105-B(5):511–517. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.105B5.BJJ-2022-0373.R2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tande A.J., Patel R. Prosthetic joint infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27(2):302–345. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00111-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grauer J.D., Amstutz H.C., O'Carroll P.F., Dorey F.J. Resection arthroplasty of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71(5):669–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Diaz-Ledezma C., Higuera C.A., Parvizi J. Success after treatment of periprosthetic joint infection: a delphi-based international multidisciplinary consensus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(7):2374–2382. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-2866-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tarabichi M., Shohat N., Goswami K., Parvizi J. Can next generation sequencing play a role in detecting pathogens in synovial fluid? Bone Joint Lett J. 2018;100-B(2):127–133. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.100B2.BJJ-2017-0531.R2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Crotty M.P., Krekel T., Burnham C.A., Ritchie D.J. New gram-positive agents: the next generation of oxazolidinones and lipoglycopeptides. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54(9):2225–2232. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03395-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gibb B.P., Hadjiargyrou M. Bacteriophage therapy for bone and joint infections. Bone Joint Lett J. 2021;103-B(2):234–244. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.103B2.BJJ-2020-0452.R2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.George D.A., Gant V., Haddad F.S. The management of periprosthetic infections in the future: a review of new forms of treatment. Bone Joint Lett J. 2015;97-B(9):1162–1169. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.97B9.35295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sosa B.R., Niu Y., Turajane K., et al. John Charnley Award: the antimicrobial potential of bacteriophage-derived lysin in a murine debridement, antibiotics, and implant retention model of prosthetic joint infection. Bone Joint Lett J. 2020;102-B(7_Supple_B):3–10. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.102B7.BJJ-2019-1590.R1. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]