Abstract

Introduction

Congenital epulis, also known as Neumann's tumor, is an uncommon benign tumor of the oral mucosa that occurs in newborns. It is a rare condition, with fewer than 250 reported cases worldwide. The exact cause or underlying mechanism of this tumor is still not well understood.

Case presentation

We present a three-day-old male neonate who presented with a swelling on the gingiva that had been present since birth. The infant did not encounter any difficulties with feeding or breathing. The patient had a single, round, pink swelling measuring 2 × 2 × 1 cm on the right maxillary alveolar ridge. The swelling was surgically removed under general anesthesia. Microscopic examination revealed large polygonal cells with abundant granular cytoplasm, centrally located nuclei indicating a diagnosis of congenital epulis.

Clinical discussion

Clinical manifestation could vary from no symptoms to feeding difficulty and rarely airway obstruction. It usually tends to grow on anterior alveolar ridge of the newborns, more on the maxilla than on the mandible. Confirmation of the diagnosis is by histopathology, which commonly shows proliferation of polygonal round cells with eosinophilic granular cytoplasm and round central nucleus. Congenital epulis can be approached using different management techniques depending on the size, site of the tumor, and presenting symptoms of the newborns.

Conclusion

Congenital epulis is rare, but it has to be considered as a differential diagnosis for gingival swelling among neonates.

Keywords: Congenital epulis, Maxilla, Case report

Highlights

-

•

Congenital epulis is a rare congenital tumor of the newborn.

-

•

Microscopy shows cells with abundant granular cytoplasm, centrally located nuclei.

-

•

General anesthesia is safer for newborns with Congenital epulis.

1. Introduction

Congenital epulis, also known as Neumanns' tumor, is a rare benign oral mucosal tumor of newborns, which was first described by Neumann in 1871. It is also recognized alternatively as congenital granular cell lesion, gingival granular cell tumor of the newborn, congenital epulis of the newborn, congenital granular cell myoblastoma, and granular cell fibroblastoma. Congenital epulis has a very low incidence of 0.0006 % at a university hospital in Wales, with less than 250 cases reported worldwide [[1], [2], [3]]. Although some speculate that it originates from Schwann cells, it typically tests negative for the S-100 protein [[3], [4], [5]]. However, in one case report, contradictory positivity to this protein was seen [1]. The case report has been reported in line with SCARE Criteria [6].

2. Case presentation

A 3-days-old male neonate was referred to the maxillofacial surgery department due to swelling on the gingiva that had been present since birth. The baby did not experience any difficulties with feeding or breathing. During the physical examination, all vital signs were within the normal range. A single, round, pink, pedunculated, fleshy, nontender swelling measuring 2 × 2 × 1 cm was observed on the right maxillary anterior alveolar ridge. Abdominal and Transfontanelle ultrasound was none revealing. The neonate was delivered through a spontaneous vaginal delivery from parents with unremarkable medical history.

The swelling was surgically removed under general anesthesia, and the excised sample was sent to the pathology department for histopathological examination. Following the operation, the patient had a smooth recovery and was discharged from the hospital in stable condition after 3 days, with a scheduled follow-up appointment in a month. During follow up the patient had no history of difficulty feeding or breathing and the mass did not recur.

During the macroscopic examination, a solitary, multinodular, grey-white, and firm polypoid tissue measuring 2 × 1 × 0.7 cm was received. The cut surface of the specimen displayed a uniform grey-white tissue with a focus of hemorrhage (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Gross specimen showing multinodular grey-white tissue.

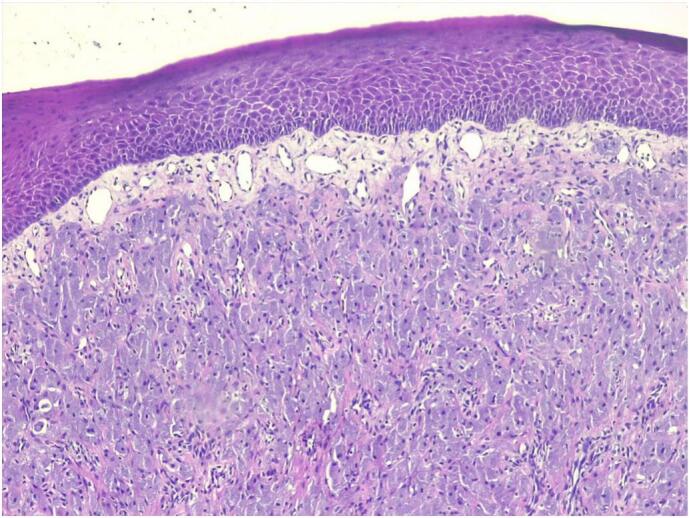

Microscopic analysis of the tissue revealed a polypoid structure with stratified squamous surface epithelium and areas of surface epithelial ulceration. Sheets and nests of large polygonal cells were present, exhibiting well-defined cell borders, abundant granular cytoplasm, and centrally located nuclei. Scattered blood vessels were also observed, and there were no signs of mitosis (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4). Based on these histomorphological characteristics, the case was diagnosed as congenital epulis.

Fig. 2.

Low power microscopic view showing stratified squamous epithelium with subepithelial proliferation of large polygonal cells in nests and solid sheets.

Fig. 3.

Medium power microscopic view showing nests and sheets of large polygonal cells having abundant granular eosinophilic cytoplasm and central nucleus.

Fig. 4.

High power microscopic view showing different sized blood vessels distributed in some parts of the lesion.

3. Discussion

Congenital epulis is a rare benign oral mucosal tumor of newborns. Although its etiology or pathogenesis is still obscure, there have been different theories as to the origin of congenital epulis, including myoblastic, neurogenic, odontogenic, fibroblastic, histiocytic, and endocrinologic origin of the tumor [[1], [2], [3],7]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the third reported case in Ethiopia.

Depending on the size, number, and location of the tumor, clinical manifestation could vary from no symptoms to feeding difficulty and rarely airway obstruction. Clinically, congenital epulis can grossly present as smooth-surfaced lobular or ovoid, sessile or pedunculated, red or pink nodule with a size ranging from several millimeters up to 7.5–10 cm. It usually tends to grow on anterior alveolar ridge of the newborns, more on the maxilla than on the mandible with a ratio of 3:1 [3,5,[7], [8], [9]]. Congenital epulis mostly occurs as a single tumor, but 10 % of cases were reported to be multiple. Despite its gender predilection for females with an F:M ratio of 8–10:1, detectable estrogen and progesterone receptors were not witnessed in the lesions [1,7,8,10]. Differential diagnosis of a tumor in the newborn's oral cavity could be teratoma, rhabdomyoma or rhabdomyosarcoma,leiomyoma or leiomyosarcoma, congenital dermoid cyst, congenital cystic choristoma, congenital fibrosarcoma, congenital lipoma, hemangioma, granuloma, infantile myofibroma, and GCT [11].

Diagnosis of congenital epulis in general is made clinically at or after birth, but prenatal imaging like three-dimensional ultrasound, Doppler ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging, done usually around third trimester of pregnancy, can be used to make prenatal diagnosis of congenital epulis by narrowing differential diagnosis, helping to assess complications, and panning mode of delivery. In addition, knowing the presence of a tumor while in utero can help both physicians and parents to better cope with the postpartum situation and plan the best treatment possible [9,12]. Confirmation of the diagnosis is by histopathology, which commonly shows proliferation of polygonal round cells with eosinophilic granular cytoplasm and round central nucleus with overlying thin squamous epithelium. Given the histopathologic resemblance of congenital epuils with GCT, it is important to mention some differences of the two diseases. Unlike congenital epulis, GCT usually affects adults between the age of 30 and 60 and mostly manifests on the tongue. Their immunohistochemistry variation is believed to come from their difference in their cellular origin. GCT is thought to arise from Schwann cells and shows positive expression for S-100 protein, while congenital epulis is believed to originate from stroma or neuroectoderm and often shows negative S-100 protein staining. On microscopic examination, GCT has overlying pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplesia of the squamous epithelium, while congenital epulis has overlying thin squamous epithelium [9,11,13].

Congenital epulis can be approached using different management techniques depending on the size, site of the tumor, and presenting symptoms of the newborns. For those with small lesions and no associated feeding or respiratory problems, conservative management for spontaneous regression with regular follow up is best possible option as this protects the newborns from the effect of surgery and anesthesia. This technique is proved to have no effect on normal dentation [14]. In another case report, combination of waiting for regression and subsequent surgical excision were reported to be beneficial to the newborns in a way that it will give time for the tumor to reduce in size and for newborn's physiology to develop for surgery. After excision of the tumor using electrical cauterization, the baby was followed for 3 years, and no recurrence was seen and dentation was unaffected [15]. Also, in another case reports, combined therapy was applied for multiple lesion, where the larger one was excised and the smaller one (causing no symptom) were left to regress spontaneously [4,5]. Generally, if the tumor is large and/or obstructive it has to be excised surgically under either general or local anesthesia. One case report argues general anesthesia is safer for newborns with Congenital epulis for maintaining good airway protection and minimizing blood loss, stress, and pain accompanying the surgery [16]. Excision of the tumor under local anesthesia is also an option for those who cannot be intubated or with small lesions. Recently removal of the tumor is being done with electrical cauterization [8]. However, usage of modified microdissection needle to remove the tumor is reported to be economical, equally safe, and effective [12]. Another author also suggested laser surgery for removal of the tumor, which is cost effective with minimal intraoperative and postoperative complications, and it can be done in an outpatient setting [17]. Congenital epulis is known to have good postoperative prognosis with no recurrence of the tumor even with incomplete surgical excision, and no malignant transformation was seen [4,5,14].

4. Conclusion

Congenital epulis is a rare occurrence, the decision to either manage it conservatively or remove it surgically might be challenging. The size and number of the tumor and whether or not it is causing obstructive symptoms are the factors taken under consideration to decide course of treatment. Congenital epulis has to be considered as a differential diagnosis for gingival swelling among neonates.

Consent

A written informed consent for the data and pictures was obtained from the mother and available upon request from the Editor-in chief.

Ethical approval

According to our institution, ethical clearance is not required for case reports.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author contribution

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Guarantor

Dr. Kirubel Addisu Abera.

Research registration number

Elsevier does not support or endorse any registry.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Data availability

The authors of this manuscript are willing to provide any additional information regarding the case report.

References

- 1.Babu E., et al. Congenital epulis of the newborn: a case report and literature review. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2021;14(6):833–837. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10005-2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rauniyar D., et al. Congenital epulis: a rare diagnosis of newborn. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2023;2023(8) doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjad453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Navas-Aparicio M.D.C., Acuña-Navas A., Colombari D. Guillén. Congenital granular cell tumor of the newborn. A case report and literature review. Odovtos. 2022:135–141. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang M.J., Kang S.H. Congenital epulis in a newborn. J. Korean Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022;48(6):382–385. doi: 10.5125/jkaoms.2022.48.6.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gan J., et al. Multiple congenital granular cell tumours of the maxilla and mandible: a rare case report and review of the literature. Transl. Pediatr. 2021;10(5):1386–1392. doi: 10.21037/tp-21-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sohrabi C., et al. The SCARE 2023 guideline: updating consensus surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2023;109(5):1136–1140. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pek?etin Z.S., et al. Congenital epulis of the newborn: a case report. Open J. Stomatol. 2018;08(04):7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vinay K.N., et al. Neumann’s tumor: a case report. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2017;27(2):189–192. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v27i2.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ye Y., et al. Prenatal diagnosis and multidisciplinary management: a case report of congenital granular cell epulis and literature review. J. Int. Med. Res. 2021;49(10) doi: 10.1177/03000605211053769. (p. 03000605211053769) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar R.M., et al. Congenital epulis of the newborn. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2015;19(3):407. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.174642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheung J.M., Putra J. Congenital granular cell epulis: classic presentation and its differential diagnosis. Head Neck Pathol. 2020;14(1):208–211. doi: 10.1007/s12105-019-01025-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarangal H., et al. Management of congenital epulis: a case report with review of literature. J. South Asian Assoc. Pediatr. Dent. 2018;1(02):58–60. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodrigues K.S., et al. Congenital granular cell epulis: case report and differential diagnosis. J. Br. Patol. Med. Lab. 2019:55. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ritwik P., Brannon R.B., Musselman R.J. Spontaneous regression of congenital epulis: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Reports. 2010;4(1):331. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-4-331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dhareula A., et al. Congenital granular cell tumor of the newborn – spontaneous regression or early surgical intervention. J. Indian Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent. 2018;36(3):319–323. doi: 10.4103/JISPPD.JISPPD_1187_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dulal A., et al. Anesthetic management of congenital epulis in a newborn: a case report. Ann. Med. Surg. (Lond.) 2023;85(5):1998–2000. doi: 10.1097/MS9.0000000000000539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernaola-Paredes W.E., et al. Clinical and histopathological features of congenital epulis in a newborn submitted to laser surgery. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2022;26(Suppl. 1):S77–S79. doi: 10.4103/jomfp.jomfp_449_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors of this manuscript are willing to provide any additional information regarding the case report.