Abstract

MXenes are being heavily investigated in biomedical research, with applications ranging from regenerative medicine to bioelectronics. To enable the adoption and integration of MXenes into therapeutic platforms and devices, however, their stability under standard sterilization procedures must be established. Here, we present a comprehensive investigation of the electrical, chemical, structural, and mechanical effects of common thermal (autoclave) and chemical (ethylene oxide (EtO), and H2O2 gas plasma) sterilization protocols on both thin-film Ti3C2Tx MXene microelectrodes and mesoscale arrays made from Ti3C2Tx-infused cellulose-elastomer composites. We also evaluate the effectiveness of the sterilization processes in eliminating all pathogens from the Ti3C2Tx films and composites. Post-sterilization analysis revealed that autoclave and EtO did not alter the DC conductivity, electrochemical impedance, surface morphology, or crystallographic structure of Ti3C2Tx, and were both effective at eliminating E. coli from both types of Ti3C2Tx-based devices. On the other end, exposure to H2O2 gas plasma sterilization for 45 minutes induced severe degradation of the structure and properties of Ti3C2Tx films and composites. The stability of the Ti3C2Tx after EtO and autoclave sterilization as well as the complete removal of pathogens establish the viability of both sterilization processes for Ti3C2Tx-based technologies.

Keywords: MXenes, Bioelectronics, Ti3C2Tx, Sterilization, Wearables, Implantable electrodes

Bioelectronic technologies are widely used in the clinical diagnosis and treatment of neurological and neuromuscular disorders.1-7 Since the introduction of implantable neuromodulators in the late 1960s, bioelectronic devices have predominantly relied on metals like platinum (Pt) and stainless steel to monitor and modulate the activity of excitable cells and tissues. These materials, however, pose significant challenges in realizing safe, stable, and functional interfaces with biological structures - primarily arising from the fundamental mismatch of their mechanical, electrochemical, and chemical properties.8-11 Propelled by the recognition of the tunable structure-function properties both at the molecular scale and in the assembled form, there has been a growing interest in leveraging nanostructured materials for applications in bioelectronics. Promising nanomaterials that have been explored include graphene,12-14 carbon nanotubes,15,16 nanodiamonds,17 and Pt nanorods,18 among others.

Two-dimensional metal carbides and nitrides (MXenes) are rapidly emerging as cost-effective and high-performance alternatives to noble metals for high-resolution, multiscale bioelectronics.19-21 MXenes are transition-metal carbides, carbonitrides, and nitrides typically produced by selective etching of the A element, like aluminum, from the layered MAX-phase precursors, where M is an early transition metal and X is carbon or nitrogen. Among their properties, the high electrical conductivity,22 volumetric capacitance,23 hydrophilicity,24 biocompatibility,25 and antibacterial nature26,27 make MXenes particularly suitable for bioelectronic applications. Liquid-phase processing of aqueous Ti3C2Tx MXene dispersions has been successfully leveraged in several application-specific fabrication schemes to produce recording, stimulation, and biosensing devices. To date, Ti3C2Tx-based bioelectronic technologies have been demonstrated in a number of applications, including wearable cardiac (electrocardiography, ECG), muscle (electromyography, EMG), and brain (electroencephalography, EEG) electrodes,28-30 as well as invasive electrode arrays for neural recording and stimulation,31,32 detection of neurochemicals,33,34 and remote non-genetic neuromodulation.35

As MXenes and other emerging nanomaterial-based technologies advance towards translation, their ability to withstand standard clinical sterilization processes to be rendered pathogen-free becomes of paramount importance and must be demonstrated. As dictated by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and other internationally-accepted standards for medical device sterilization, any device or item intended to enter a sterile environment or tissue can pose a high risk of infection, thus requiring sterilization by either steam autoclave, H2O2 gas plasma, or ethylene oxide (EtO).36,37 Demonstrating robust stability of Ti3C2Tx MXene films and devices under these commonly implemented clinical sterilization procedures would thus mark an important milestone in the translational pathway of MXene-based medical technologies.

Here, we present a systematic investigation of the stability of Ti3C2Tx MXene films and devices under EtO, steam autoclave, and H2O2 gas plasma sterilization. Specifically, we investigate thin-films of Ti3C2Tx spray-cast onto Parylene-C to form microelectrode arrays,32 as well as devices made from laser-machined cellulose-polyester blends infiltrated with Ti3C2Tx.30 We first evaluate the effects of sterilization on the electrical, electrochemical, structural, chemical, and mechanical properties of Ti3C2Tx films and devices. Then, we demonstrate the effectiveness of the sterilization processes in rendering Ti3C2Tx devices pathogen-free, by quantifying E. coli bacterial units in both device types over a 24-hour post-sterilization incubation period.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

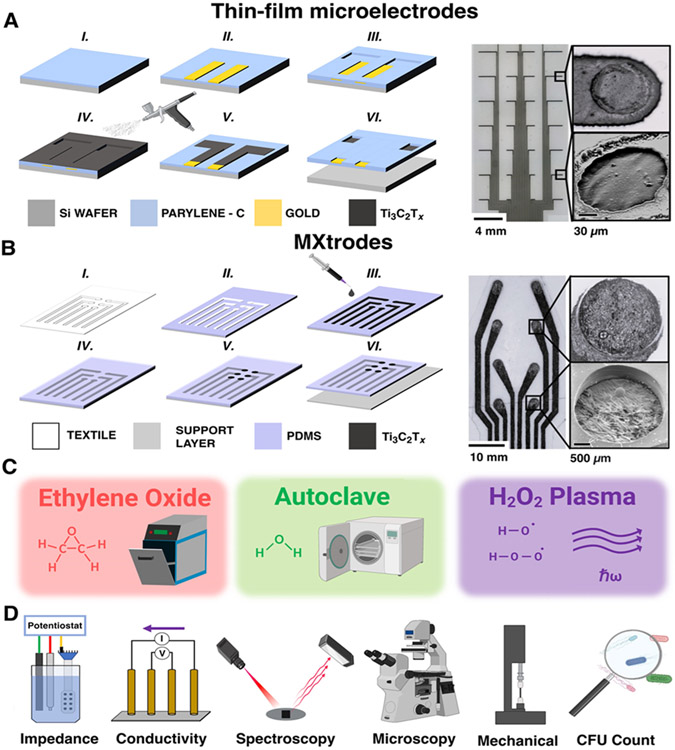

Ti3C2Tx thin-film microelectrodes and cellulose-polyester-Ti3C2Tx arrays (a.k.a. MXtrodes) were fabricated using previously established protocols, detailed in the supporting information (SI).30,32 Briefly, thin-film microelectrodes were arranged in a 4x8 grid (12.1 mm x 28.1 mm) made of Ti3C2Tx films (~1 mg/mL, 100 mL) spray-cast onto a 3.5-μm-thick Parylene-C film (Figure 1A). 100-nm-thick Ti/Au pads and interconnects were photolithographically defined and electron-beam deposited before a second 3.5-μm-thick Parylene-C layer was added to form the top encapsulation.32 Electrode diameter and pitch are 100 μm and 4 mm (in both directions, Figure S1). The thin-film microelectrodes were designed to provide high-resolution neural monitoring capabilities by leveraging a high-density of microscale electrode contacts made on an ultrathin substrate (final device thickness: 7.0 ± 1.1 μm, number of samples, n = 8). Cellulose-polyester-Ti3C2Tx MXtrodes were composed of 2.5 mm contacts arranged in a 2x4 array (12.5 mm x 32.5 mm) spaced 1 cm apart (Figures 1B and S2). The arrays were fabricated from a Texwipe® cellulose-polyester blend textile infused with Ti3C2Tx (~20 mg/mL) and were encapsulated on both sides with ~300 μm polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) layers (final device thickness: 820 ± 100 μm, n = 14). The elemental composition of device contacts was qualitatively confirmed for both device form-factors using Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDX) measurements which highlighted the elemental presence of Ti3C2Tx as well as the encapsulating Parylene-C for thin-film microelectrodes and PDMS for MXtrodes (Figure S3).

Figure 1. Overview of the study.

(A, B) Left: schematics of fabrication process, right: bright-field microscopy and SEM images of completed arrays and contacts for (A) high-density Ti3C2Tx MXene thin-film microelectrodes, and (B) MXtrode arrays. (C) Sterilization processes investigated in this work. (D) Schematics of the analysis methods used to evaluate the post-sterilization stability of Ti3C2Tx.

We subjected both types of devices to the following sterilization cycles using clinical equipment and standard cycle parameters: EtO, Anprolene AN74i, 12-hour cycle, 2-hour post-sterilization gas purge; steam autoclave, Primus PSS 500, up to 30-minute cycle, 134 °C chamber temperature; H2O2 gas plasma, Sterrad NX 100, 47-minute cycle, sub-ambient pressure (Figure 1C). After each sterilization cycle, we evaluated the electrochemical and bulk conductivity effects of sterilization by collecting electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and DC conductivity with a Gamry Reference 600 potentiostat and a Loresta-AX four-point probe, respectively. We further characterized the effects of sterilization on the structure, bulk, and surface chemistry of Ti3C2Tx using X-ray diffraction (XRD), Raman spectroscopy, and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) for each device. Additionally, we used optical and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to visualize the effects of sterilization on the devices and characterize the extent of film cracking and delamination of the Ti3C2Tx from the underlying substrate at the exposed contact sites. For MXtrode composites, we also investigated the mechanical properties of device samples in response to sterilization by monitoring the change in device resistance over the course of hundreds of continuous cyclic deformations (to induce bending) as well as with vertical tensile elongation to failure. Finally, we evaluated the effectiveness of the sterilization treatments at rapidly removing all pathogens from the devices by measuring the presence of E. coli bacterial colony forming units (CFU) counted over a 24-hour incubation period at 37 °C (Figure 1D).

Electrochemical and Electrical Stability.

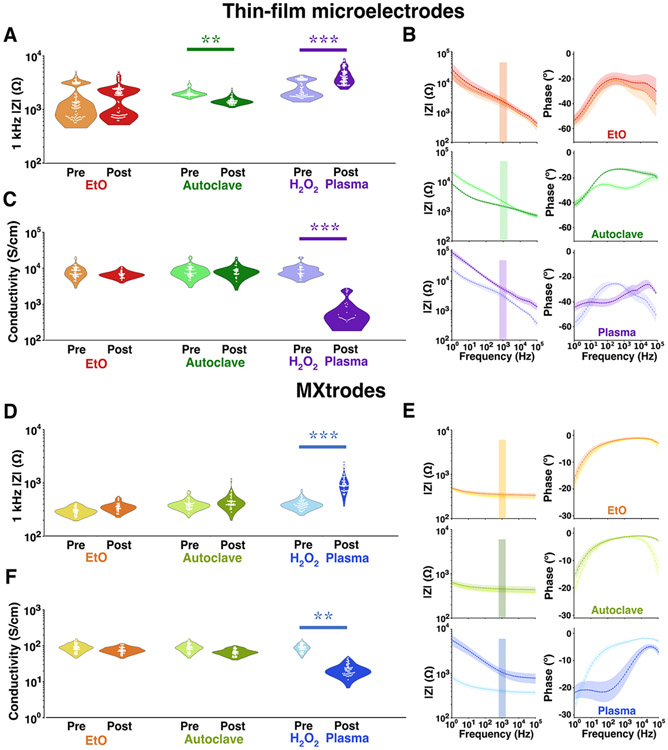

As bioelectronics primarily rely on the electrochemical transduction of ionic currents in the body at the electrode-tissue interface, we first investigated the influence of sterilization on the electrochemical interface impedance of thin-film and MXtrode devices with EIS scans acquired in 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before and after each sterilization cycle. For thin-film microelectrodes post-EtO, we did not observe a significant change in the impedance modulus at the reference frequency of 1 kHz (pre: 1.9 ± 1.2 kΩ, post: 2.1 ± 1.1 kΩ, with a non-significant effect size of 0.21, Figure 2A and Table S1). We also did not observe a significant change in impedance across the entire 102–105 Hz frequency range. Autoclave sterilized thin-film arrays showed a significant decrease in impedance post-sterilization (pre: 2.1 ± 0.3 kΩ, post: 1.5 ± 0.2 kΩ, effect size: 2.54), which was accompanied by the disappearance of a local minimum in the phase at 102–104 Hz, while the rest of the spectral response remained essentially unchanged (Figure 2B). This change in the phase behavior can be attributed to the evaporation of water intercalated between MXene layers in the films – possibly from ambient environmental humidity or aqueous EIS testing in the pre-autoclave exposure – and is further supported by a low d-spacing value of 11.4 Å post-sterilization (Table S2). In contrast, H2O2 gas plasma sterilized devices showed a significantly higher impedance after sterilization (pre: 2.8 ± 1.0 kΩ, post: 4.9 ± 1.7 kΩ, effect size: 3.10) and a capacitive shift in the broadband phase response. H2O2 sterilized thin-film devices also showed a decrease in their electronic properties with >10x DC conductivity loss (pre: 9.0 ± 3.3 103 S cm−1, post: 9.2 ± 7.8 102 S cm−1, effect size: 3.00). On the other hand, DC conductivity of Ti3C2Tx films remained unchanged after EtO (pre: 8.9 ± 3.2 103 S cm−1, post: 7.1 ± 1.4 103 S cm−1, effect size: 0.698) and autoclave sterilization (pre: 8.9 ± 3.1 103 S cm−1, post: 8.7 ± 3 103 S cm−1, effect size: 0.087, Figure 2C and Table S3).

Figure 2. Electrochemical impedance and DC Conductivity of sterilized devices.

(A-C) Thin-film microelectrodes: (A) 1 kHz impedance modulus (EtO: 3 devices, n = 96 channels, AC: 2 devices, n = 53 channels, H2O2 plasma: 3 devices, n = 86 channels). (B) Full-band EIS impedance and phase spectra. (C) DC conductivity (n = 30 samples each). (D-F) MXtrodes: (D) 1 kHz impedance modulus (sample size: 5 devices each, n = 40 channels). (E) Full-band EIS impedance and phase spectra. (F) DC conductivity (n = 45 samples each). (* effect size > 1 / ** effect size > 2 / *** effect size > 3). In (B) and (E) points are means, shaded areas are standard deviations.

MXtrode devices also showed a similar EIS and DC conductivity responses in each of the tested conditions. The impedance modulus and phase behavior of sterilized MXtrodes were stable after both EtO (pre: 300 ± 60 Ω, post: 350 ± 60 Ω, effect size 0.887) and autoclave sterilization (pre: 400 ± 80 Ω, post: 460 ± 150 Ω, effect size: 0.872, Figure 2D). Interestingly, the phase response of the MXtrode devices did not show evidence of intercalated water removal after autoclave sterilization and appeared to be unaffected by the treatment cycle, with a d-spacing of 12.5 Å both before and after sterilization. This could be caused by the composite morphology, where the cellulose-polyester-PDMS matrix inhibits the ingress of water between the Ti3C2Tx flakes, as previously suggested.38 Consistent with the thin-film device response, however, H2O2 gas plasma strongly affected the electrochemical interface of MXtrodes, with the impedance modulus increasing from 400 ± 80 Ω to 1100 ± 410 Ω (significant effect size of 10.1) and the phase response again shifting to lower angles (Figure 2E). We also evaluated potential size effects in the impedance response by exposing MXtrode devices with 1 mm and 5 mm contact size to the same sterilization conditions, but we did not find any significant difference in effect compared to the 2.5 mm devices (Figure S4), although we did see the overall magnitude of impedance increase with decreasing electrode diameter regardless of sterilization, as expected.39,40 DC conductivity measures also had similar trends in the effects of sterilization on the 2.5 mm MXtrodes with non-significant changes after EtO (pre: 90 ± 20 S cm−1, post: 77 ± 14 S cm−1, effect size: 0.490, Figure 2F) and autoclave sterilization (pre: 92 ± 21 S cm−1, post: 68± 13 S cm−1, effect size: 0.791), but a significant > 3x drop in conductivity after exposure to H2O2 gas plasma (pre: 90 ± 22 S cm−1, post: 23± 8 S cm−1, effect size: 2.21).

XRD and Raman Analysis of Ti3C2Tx Films and Devices.

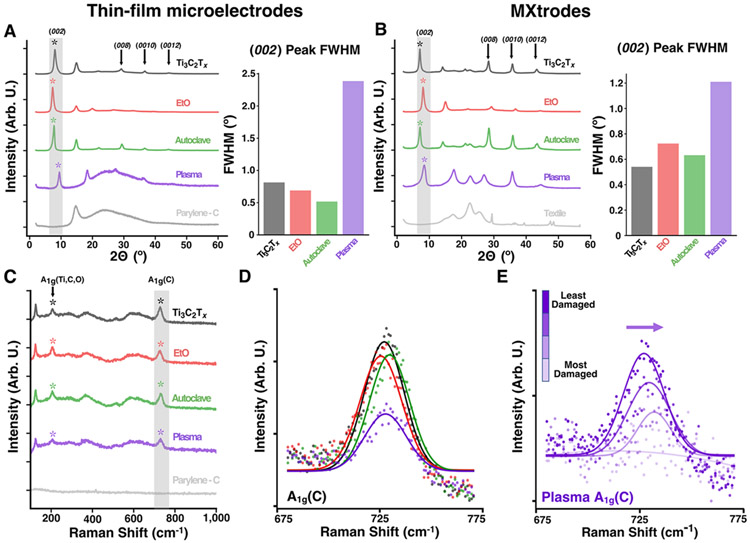

To confirm that the structure and chemical composition of Ti3C2Tx thin films and composites were unaffected by EtO and autoclave, but also to further elucidate the mechanisms of H2O2 gas plasma-induced degradation, we collected XRD patterns and Raman spectra for each sterilization condition and quantitatively compared the results against: 1) pristine (i.e., non-sterilized) Ti3C2Tx samples, 2) the background spectra of the substrate. In the XRD patterns, we noted the presence of the characteristic (00l) peaks of Ti3C2Tx MXene for all pristine and sterilized samples in both device form factors, indicative of out-of-plane stacking of MXene flakes (Figure 3A and 3B).41 We further calculated the full width at half-maximum (FWHM) of the dominant (002) peak for each sample to probe the flake alignment and interlayer spacing variations in the sterilized samples.42 For both device types, the FWHM did not vary significantly after either EtO or autoclave sterilization, indicating no change in the flake alignment. Furthermore, the increased intensity of high-order (00l) peaks in the autoclaved samples suggests a regular spacing between MXene layers and no negative effect of this treatment on the film structure. Only a minor expansion of the interlayer spacing was observed for the EtO sterilized thin films (from 10.9 to 12.1 Å), which notably did not affect the post-sterilization electrochemical behavior. H2O2 gas plasma sterilized thin films and MXtrodes, however, showed a significant increase in the FWHM of the (002) peak, which is indicative of a decreased structural order and, possibly, more anisotropic spacing of the Ti3C2Tx flakes.43,44 Further, the XRD patterns of the H2O2 gas plasma samples showed a broad scattering background similar to the Parylene-C layer for the thin-films and the strong peak at ~23° similar to the textile for the MXtrodes, which both indicate some loss of Ti3C2Tx layers, damage and sputtering of the substrate layers, or formation of amorphous degradation products. Likely, loss of interlayer water and sintering of the films after gas plasma sterilization resulted in the up-shift of the (002) peak, which is further supported by the decrease in the d-spacing after H2O2 gas plasma treatment.

Figure 3. Raman and XRD analysis of pristine and sterilized devices.

(A, B) Left: XRD patterns including pristine control and Parylene-C or textile backgrounds. Right: FWHM of the (002) peak for (A) thin-film devices and (B) MXtrodes (n = 2 for each condition). (C) Raman spectra including pristine controls and Parylene-C background for thin-film devices. (n = 2 samples for each condition). (D) Normalized Gaussian-fitted A1g(C) peak for thin-film devices. (E) Right-shifting Normalized Gaussian-fitted A1g(C) peak for increasingly visually damaged thin-film samples after H2O2 gas plasma sterilization.

Raman spectra of the pristine and sterilized Ti3C2Tx MXene thin films and MXtrode samples (Figure 3C and S5) showed the characteristic Ti3C2Tx peaks, including the E1g(C) in-plane resonance at ~120 cm−1 and both A1g(Ti, C, O) and A1g(C) out-of-plane peaks at ~205 cm−1 and ~730 cm−1, respectively.45 Raman spectra were analyzed by normalizing the A1g(C) peak in each spectrum by its maximum and fitting it with a Gaussian curve to compare the amplitude and peak center of the fitted A1g(C) peaks and calculate the normalized FWHM. For both EtO and autoclave sterilized samples, there was no significant change in the A1g(C) peak amplitude or FWHM compared with the pristine MXene. There was, however, a significant increase in the FWHM and decrease in the A1g(C) peak amplitude that was only seen in the H2O2 gas plasma sterilized samples, likely caused by surface degradation and a removal of MXene layers during the sterilization cycle (Figures 3D, S6, and S7). Indeed, when scanning at shift values > 1000 cm−1 there were large D and G band peaks indicative of amorphous carbons between 1100 cm−1 – 1700 cm−1 formed upon MXene degradation in the H2O2 gas plasma thin-film samples, compared to much smaller peaks in EtO and autoclave samples (Figure S8A). Furthermore, in a subset of H2O2 gas plasma thin-film samples that became visually more damaged, the A1g(C) peak trended towards lower amplitudes and right-shifted to higher wavelengths (from 727 cm−1 to 732 cm−1, Figure 3E), which has been shown to be caused by a decrease in the MXene layer thickness,44,46 and could potentially indicate the onset of Ti3C2Tx oxidation.47 In addition to the A1g(C) peak, other characteristic Raman signatures of Ti3C2Tx gradually attenuate with increasing level of visual damage, including the A1g(Ti, C, O) and E1g(C) peaks (Figure S8B). However, despite the visible lightening in color, surface damage, and right-shifted A1g(C) peak, there were no signs of rutile or anatase titanium oxide (TiO2) on any of the Raman spectra collected for H2O2 sterilized thin-film arrays and MXtrodes, despite the higher sensitivity of Raman to the formation of nanoscale TiO2 compared to XRD.44,48 This suggests that the bulk chemistry of Ti3C2Tx in the devices is unaffected by the exposure to H2O2 gas plasma. Moreover, the visible damage in the case of H2O2 plasma treatment was confined predominantly to the surface of the samples. Therefore, since the penetration depth of light into Ti3C2Tx films is several microns with an excitation wavelength of 785 nm,49 the presence of Ti3C2Tx peaks in the Raman spectra of the H2O2 plasma treated films indicate that the majority of the damage did not exceed ~10s of nanometers. This suggests that the Ti3C2Tx is being continuously oxidized and etched away directly at the surface rather throughout the bulk of the material.

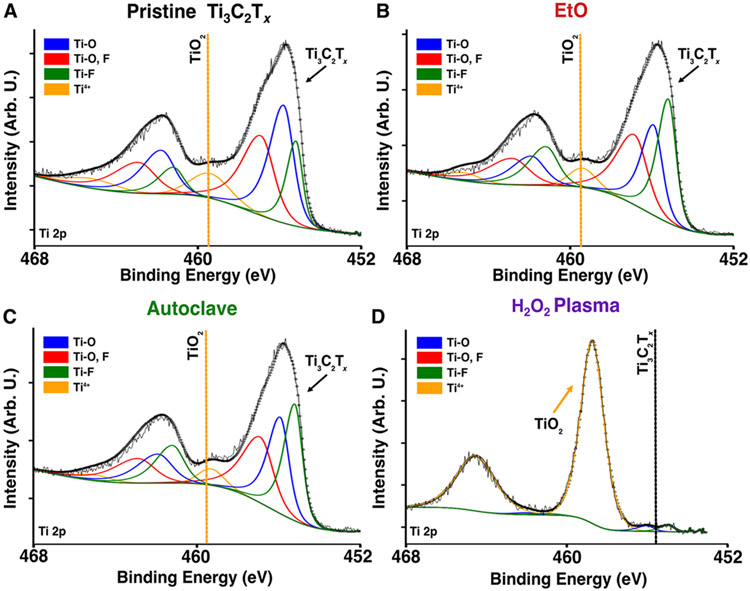

XPS Analysis Confirms Oxidation after H2O2 Gas Plasma Sterilization.

To characterize the chemical composition of the sterilized samples and investigate the possible presence of surface TiO2 as a driving mechanism for Ti3C2Tx degradation in H2O2 gas plasma sterilized samples, we collected XPS spectra for EtO, autoclave, and H2O2 gas plasma sterilized thin films and MXtrodes and compared them to pristine samples. For pristine samples and those sterilized with EtO and autoclave, the Ti 2p spectra shows three pairs of doublets attributed to Ti with -O and -F surface terminations indicative of properly-synthesized Ti3C2Tx MXene, and with less than ~10 % of the spectra stemming from TiO2 (doublet at ~459 eV and ~465 eV, Figure 4A-C, S9A and Table S4).50,51 Similarly, the C 1s spectra clearly shows one peak attributed to C-Ti bonding indicative of pristine MXene, and other peaks attributed to adventitious carbon contamination on the surface (Figure S9C).51 After H2O2 gas plasma sterilization, however, the components attributed to Ti3C2Tx in the Ti 2p and C 1s spectra completely disappear (Figure 4D) and the survey spectra indicates only titania, amorphous carbon, and silica remain, confirming surface oxidation (Figure 4D and S9A).44,52 The increase of the Si 2s and Si 2p peaks in the survey spectra, presumably from silica, are indicative of the exposed substrate for the thin film samples, which again indicate the loss of Ti3C2Tx flakes in plasma sterilized samples, consistent with XRD and Raman results. Considering that XPS probing depth is less than 10 nm, and titania was only identified in XPS but not in Raman spectra, our findings suggest that only the surface layers – between 10 to 100 nm – are oxidized and the remaining Ti3C2Tx is intact. Moreover, the exposed substrate indicates that damage is not homogenous throughout the entire surface and some spots might be more damaged than others.

Figure 4. XPS of pristine and sterilized devices.

(A-D) Ti 2p XPS spectra of thin-film microelectrodes (A) before and (B-D) after sterilization with EtO, autoclave, and H2O2 gas plasma, respectively.

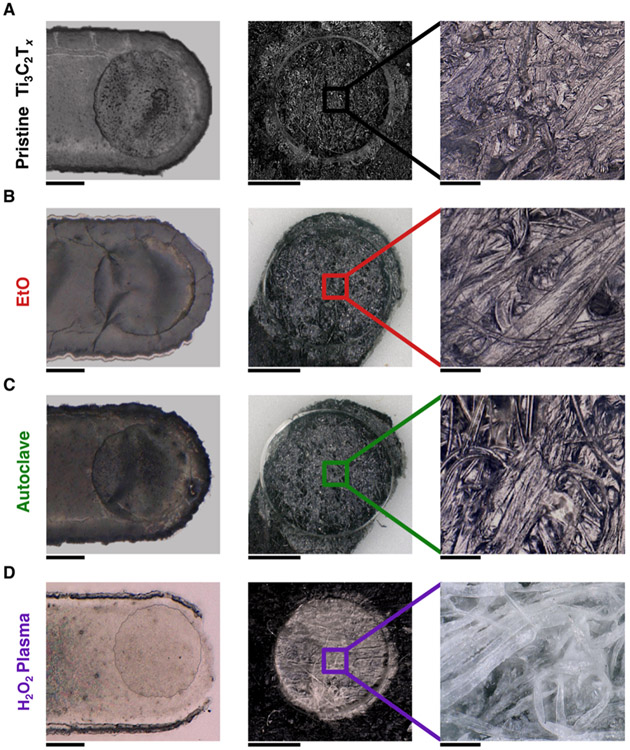

Optical and SEM of Thin-film Microelectrode and MXtrode Contacts.

The degradation of H2O2 gas plasma sterilized devices was also visually apparent. The 100 μm thin-film microelectrode and 2.5 mm MXtrode contacts were visibly lighter in color and showed clear removal of Ti3C2Tx on and around the contact site post-sterilization (Figure 5). Additionally, SEM measurements of the contact surfaces revealed that there was clear cracking of the Ti3C2Tx films for both thin-film microelectrode and MXtrode devices that were sterilized with H2O2 gas plasma along with a relative increase in elemental Oxygen in the EDX spectra (Figure S10). Notably, however, there was no apparent delamination of the encapsulating substrate visible for either device type, and both Parylene-C and PDMS layers appeared undamaged. In contrast to the visible damage incurred after gas plasma sterilization, however, EtO and autoclave sterilized thin-film and MXtrode contacts remained visually unaffected and showed no sign of Ti3C2Tx cracking or delamination on or around the exposed contacts, similar to the pristine, unsterilized contacts.

Figure 5. Optical microscopy of pristine and sterilized device contacts.

(A-D) Left: bright-field microscopy image of thin-film microelectrode contacts in pristine and sterilized conditions. Scale bar 50 μm. Middle: bright-field microscopy image of MXtrode contacts in all conditions. Scale bar 1.25 mm. Right: zoomed-in of individual cellulose-polyester fibers coated in Ti3C2Tx MXene for (A) pristine, (B) EtO, (C) autoclave, and (D) H2O2 gas plasma sterilized devices. Scale bar 100 μm.

Mechanical Stability of MXtrodes to Cyclic Bending and Tensile Testing.

Additional characterization of the effects of sterilization was performed by assessing the mechanical stability of MXtrode composites in response to cyclic bending and vertical tensile stress to failure. Briefly, cyclic deformation was performed over 300 cycles on pristine and sterilized sample MXtrode composites (5 mm x 5 cm) to induce a bending radius of ~5 mm. While the measured change in resistance from pre to post bending remained low for pristine, EtO, and autoclave sterilized samples (10 % - 16%), there was a large (>130 %) increase in the relative resistance of H2O2 gas plasma sterilized samples after bending - likely caused by a combination of the degraded electrical performance and crack formation (Figure S11). Tensile stress strain measurements of the MXtrode samples were consistent in magnitude to those previously reported,30 and appear to be driven - in all samples - by the mechanical properties of the encapsulating PDMS in the linear regime. The relative failure points for each sample condition appeared to be driven by local variations or defects in the PDMS thickness and did not seem to be affected by sterilization.

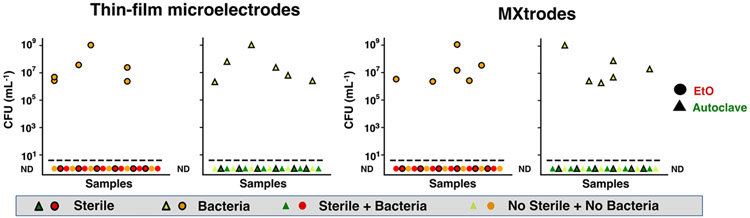

Sterilization is Effective at Rapidly Eliminating Pathogens from Ti3C2Tx Devices.

Finally, to evaluate the efficacy of EtO and autoclave at rapidly removing any and all bacterial pathogens adhered to the devices in a single sterilization cycle, we inoculated E. coli onto the devices prior to exposure to the sterilization cycles. After sterilization, we incubated all samples in culture media at 37 °C and then measured colony forming units (CFU) and optical density at 600 nm wavelength (OD600) over the following 24 hours. Samples exposed to E. coli that were not sterilized showed bacterial contamination and proliferation at all six timepoints during the 24 hours of the experiment (Figures 6 and S12). Notably, this high volume of bacteria in unsterilized samples is not related to the antibacterial properties of Ti3C2Tx directly, but rather is a control indicating that complete devices (Ti3C2Tx, PDMS, Parylene-C, Au, cellulose-textiles) that are not sterilized will not be clinically sterile or safe for patient use. For all of the samples inoculated and sterilized, however, both the bacterial count and optical density were below the detection limit threshold (ND) at all timepoints. These findings demonstrate that Ti3C2Tx thin-film microelectrodes and MXtrode composites can be effectively and completely sterilized by EtO and autoclave and rapidly rendered pathogen-free for clinically safe use in wearable and implantable devices.

Figure 6. Efficacy of EtO and autoclave sterilization.

CFU counts at all timepoints (0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 24 hours) for different combinations of sterility and bacterial inoculation of thin-film microelectrodes and MXtrodes. All samples below dashed line had non-detectable bacterial counts. ND: Non-Detectable. (n = 6 samples for each condition).

CONCLUSION

Here, we have investigated the effects and efficacy of the three most common sterilization techniques on Ti3C2Tx thin-films and textile-PDMS composites assembled in the form of electrode arrays. Our studies reveal that EtO and autoclave sterilization do not cause any change in the crystalline structure, mechanical strength, or the electronic/electrochemical properties of Ti3C2Tx. Interestingly, autoclave sterilized thin-film devices showed a slight, but consistent improvement in electrochemical impedance and disappearance of double-peak phase shifts in full EIS spectra, likely due to the removal of intercalated water. Exposure to 45-min cycles of H2O2 gas plasma sterilization, however, resulted in severe degradation of Ti3C2Tx films and composites, evidenced by a significant drop in electrical conductivity, decreased flake alignment, cracking, and Ti3C2Tx delamination from the substrates. While there was no presence of rutile or anatase TiO2 peaks in XRD patterns or Raman spectra, surface chemical analysis with XPS indicated that MXene is oxidized to TiO2 at least to within 10 nm from the surface, where the H2O2 radicals and ultraviolet (UV) excitation are likely driving Ti3C2Tx degradation. The functional and structural damage from H2O2 gas plasma sterilization treatment is not specific to Ti3C2Tx and has already been independently found to damage other common bioelectronic materials, such as PEDOT:PSS, indicating that H2O2 gas plasma sterilization is not a viable option with many emerging nanomaterial and organic bioelectronics.53 Furthermore, H2O2 gas plasma is not compatible with common electronic components such as connectors and head-stage amplifiers, or with many active bioelectronic technologies.54 Finally, we demonstrated that EtO and autoclave sterilization are effective at completely and rapidly removing all common and significantly harmful pathogens like E. coli bacteria from Ti3C2Tx thin films and composites within a single sterilization cycle. As synthesis and functionalization of Ti3C2Tx play an important role in determining its stability and resistance to oxidation, future work should elucidate the effects of different synthesis processes and terminal groups on Ti3C2Tx resistance to H2O2 gas plasma.55 Ultimately, our findings indicate that common sterilization processes widely adopted in clinical and research settings, such as EtO and autoclave, do not alter Ti3C2Tx MXene devices and thus can be integrated in processing, manufacturing, and surgical workflows for wearables and invasive implants, paving the way for the future translation of Ti3C2Tx MXene bioelectronics and other medical technologies.

METHODS

Ti3C2Tx MXene Synthesis.

Suspensions of Ti3C2Tx MXene were produced and provided by MuRata Manufacturing, Co., Ltd. Large Ti3C2Tx flakes (~ 2 μm lateral size) were synthesized using the minimally intensive layer delamination (MILD) method, where the Al is etched from the Ti3AlC2 powder (MAX phase) with a combination of 12 M LiF and 9 M HCl.24 Ti3C2Tx MXene suspensions were stored in a large glass vial at 4 °C until use.

Device Fabrication.

Thin-film microelectrodes were fabricated as follows from previously established protocols.32 On a 4” silicon wafer, 3.5-μm thick Parylene-C was deposited via chemical vapor deposition. Photolithography with negative resist (NR-73000p) was used to pattern conductive backend channels of 10nm/90nm Ti/Au, deposited using electron beam deposition, and residual metal was lifted-off using an organic solvent. Next, an anti-adhesion cleaning solution was spun on the wafer to prevent adhesion of overlaid parylene-C layers, followed by the deposition of a 3-μm thick sacrificial parylene-C layer. The second of three photolithography processes then outlined the 32 electrode contacts, and reactive ion etching (RIE) using O2 plasma exposed the base parylene-C layer in these locations. Once the electrode contacts were exposed by the plasma etching, spray coating the 100 mL of dilute Ti3C2Tx MXene (~1 mg mL−1) onto the wafers was carried out using a hand-held, commercially available airbrush (Gravity Double Action Tattoo Art Model) from a distance of ~2 feet above the surface of the wafers at an angle of ~45° from horizontal. The Ti3C2Tx MXene used was provided by MuRata Manufacturing as a stock 20 mg/mL, which we diluted to 1 mg/mL for spray coating with DI water. The dilution was homogenized by brief (~30 seconds) sonication prior to spray coating. The working spray coating pressure was held constant at 40 psi and a 0.2 mm diameter nozzle was used. Spray coating was performed in a fume hood with the wafer set on a hot plate heated to 150 °C during the entire coating process. The angle of the spray nozzle was rapidly rastered left to right across the wafer repeatedly throughout spray coating, and the entire wafer was rotated 90 ° three times during the coating to ensure an even film distribution. After coating, the wafer was placed in an 80 °C oven for 30 minutes to bake out any residual water from the MXene films on the wafers. Once the Ti3C2Tx MXene films had dried on the wafers, the sacrificial parylene-C layer was peeled up to leave Ti3C2Tx MXene only at the 32 contact sites. A final 3.5-μm top-encapsulating Parylene-C layer was deposited on the wafer, the device shape and exposed connections were photolithographically defined, and completed devices were peeled off the wafer after a final RIE etch. Devices were stored in a N2 gas desiccator after peel-off and before use, to prevent MXene film oxidation.

MXtrodes were fabricated from a previously established protocol.30 First, the stock 30 mg mL−1 suspensions were diluted to 20 mg mL−1. Then, the array geometries were laser-patterned into a Texwipe® nonwoven, hydrogenated cellulose-polyester blend substrate with a CO2 laser. The electrode cutouts were then adhered with Adapt® 3M medical adhesive spray to a ~300-μm thick degassed and cured polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS, SYLGARD™ 184, 10:1 ratio) sheet, which served as an underlying encapsulation layer. The woven electrode geometries were next inked with Ti3C2Tx and placed in an 80 °C oven to bake for 1 hour. After inking and drying, backend connectors were attached with Circuitworks® two-part conductive silver epoxy, to interface with the recording instrumentation. A final ~300-μm thick encapsulation layer was formed by pouring PDMS over the electrode arrays, followed by 10 min degassing and 1 hour curing in the oven at 80 °C . The encapsulated devices were then cut away from the PDMS sheet into their final form. Finally, to expose the electrode contacts, the PDMS was cut out with 1mm, 2.5 mm, or 5 mm biopsy punches.

Sterilization Protocols.

Ethylene oxide (EtO) samples were sterilized in a Anprolene AN 74i machine, using a single (12-hour cycle) Anprolene® EtO ampoule to deliver the gas sterilization.

All EtO samples were packaged in commercial steam and EtO sterilization wrapping, with an Anprolene biological dosimeter indicator and a Humidichip® humidity chip. Samples were run under a 12-hour cycle for all experiments. Autoclave samples were sterilized in a Primus PSS 500 Autoclave machine. MXtrode and thin-film devices were packaged in commercial steam and EtO sterilization wrapping with indicator tape placed on the wall of the wrapping. Samples were steam sterilized using the Vacuum cycle at 134 °C for 30 minutes with a 20-minute drying time. All H2O2 plasma sterilized MXtrode and thin-film microelectrode samples were packaged in Tyvek low-temperature pouches prior to sterilization. H2O2 sterilization was performed in a Sterrad® NX 100 Plasma sterilization tool for ~45-minute cycles. The temperature of the H2O2 chamber did not exceed 50 °C.

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy.

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) of Ti3C2Tx MXtrodes and thin-film microelectrodes was acquired with a Gamry Reference 600 potentiostat (Gamry Instruments) in room temperature 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4). The measurements were collected in a three-electrode cell, with the MXtrode or thin-film microelectrode contact as the working electrode, a long graphite rod (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) serving as the counter electrode, and an Ag/AgCl electrode (Sigma-Aldrich) as the reference electrode. Measurements were collected by applying a 10 mVrms sinusoidal voltage at decreasing frequencies from 100 kHz to 1 Hz. Prior to EIS, each device was placed in an 80 °C oven for one hour to remove any potential moisture. EIS was collected on the same devices before and after sterilization.

DC Conductivity.

MXtrodes for conductivity measurements were prepared as ~2cm x 2cm square samples. Thin-film samples were prepared on 3μm parylene-C coated glass slides spray-coated with 100 mL of 1 mg mL−1 Ti3C2Tx. Spray-coating was performed on a 150 °C hot plate and slides were placed in an 80 °C oven for 1 hour after film deposition. Conductivity measurements were collected on each thin-film and MXtrode sample before and after sterilization. For MXtrodes, the average thickness of the infused textile prior to encapsulation was found to be consistent with previously reported values, at 0.28 ± .03 mm (n = 4).30 Thin-film thickness was measured on a high-resolution profilometer (KLA Tencor P7 2D Profilometer) and was 150 ± 20 nm (n = 5). DC conductivity was measured using a Loresta-AX® four-point probe. Sheet resistance (Rs, Ω / ▢) and film thickness (T, nm) were collected for each sample. Conductivity (σ, S/cm) was calculated as follows:

| (1) |

X-Ray Diffraction.

A Rigaku MiniFlex benchtop X-ray diffractometer was used for X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements (Rigaku Co. Ltd.). The source was Cu Ka (λ = 0.1542 nm), and spectra were acquired at 40 kV, 15 mA, for Bragg angles from 3°–60° at a rate of 14° min−1 with a step of 0.02°. After collection, spectra were fitted using CrystalDiffract to identify peak locations, calculate FWHM, and derive the (002) peak d-spacing values.

Raman Spectroscopy.

A Renishaw in Via Raman spectrometer (Gloucestershire, UK) instrument was used for all measurements. The acquisition time for the measurements was 10 seconds using a 63x objective (NA=0.7). The excitation intensity using the diode (785 nm) laser was 10.5 mW x 10%. All measurements were conducted by raster scanning from 100-3200 cm−1. Additional measurements investigating the presence of adventitious carbons at shift values > 1000 cm−1 were collected using a 514 nm excitation wavelength. After collection, peak amplitude and FWHM peak values were confirmed using OriginLab, which fitted the peak with a gaussian curve for calculation. Gaussian fitting for the A1g(C) peak was calculated using the following equation, where A is the peak amplitude, xo is the peak center, sd is the standard deviation of the curve, and H is the baseline offset of the peak.

| (2) |

X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy.

XPS was acquired using a PHI VersaProbe 5000 instrument (Physical Electronics) with a 25 W monochromatic Al-Kα (1486.6 eV) X-ray source targeting a 200 μm spot. Charge neutralization was acquired through a dual-beam setup using low energy Ar+ ions and low-energy electrons at 1 eV and 200 μA. Survey spectra and High-resolution spectra from the Ti 2p and C 1s core-level region were collected using pass energy / energy resolution of 117.4 / 0.5 and 23.5 / 0.05 eV, respectively. The binding energy scales were calibrated by adjusting the C-C/C-H component from adventitious carbon in the C 1s spectra to 284.8 eV, where the required shift was < 3.3 eV for all samples. Quantification and peak fitting were conducted using the CasaXPS software following previously published studies.56

Optical Microscopy.

Optical images of the MXene electrodes were acquired using a Keyence VHX6000 digital microscope. Image magnification ranged from 50x to 200x for MXtrodes and thin-film microelectrodes, respectively. 3D depth composition was performed during image acquisition to resolve the image at multiple depths.

Scanning Electron Microscopy.

SEM images of the thin-film microelectrodes and MXtrodes were acquired using a FEI QUANTA 600 FE-SEM machine. Charge neutralization was accomplished with copper conductive grounding tape. Chamber pressure was kept at a constant 0.38 torr, and power was set to 15 keV during acquisition. Image magnification ranged from 50–3000x for MXtrodes and thin-film microelectrodes, respectively.

Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy.

EDX spectra of the thin-film microelectrodes and MXtrodes was acquired in the same scanning sessions as the SEM imaging. Samples were charge neutralized with copper conductive tape and the samples were kept under high vacuum during acquisition. EDX spectra was collected and fitted with elemental mapping using the EDAX Team™ Wavelength Dispersive Spectrometry (WDS) analysis system in mapping mode with a final resolution of 256 x 512 voxels per image. Spectra were normalized by the sum of counts measured within 0-5.5 KeV at the end of acquisition.

Mechanical Testing.

Cyclic bending and tensile stress/strain measurements were performed using an Instron testing system (Instron 5948). MXtrode samples were prepared with 5 mm x 5 cm strips of textile infused with Ti3C2Tx MXene ink and encapsulated in PDMS as previously described. After sterilization, samples were placed in the Instron and were subjected to 300 cycles of 20 mm compression to induce bending that corresponded to induce a bending radius of ~5 mm. Throughout testing, resistance was recorded at 2 Hz with a Gamry Reference 600 potentiostat using alligator clips fixed to each end of the sample. Resistance was also measured with a potentiostat before and after testing to assess overall change in resistance as a result of the cyclic deformation. Force-displacement curves were measured by vertically applying force to each sample until failure.

Bacterial Culture & Quantification Assays.

Escherichia coli ATCC11775 (E. coli) was grown and plated in Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates incubated overnight at 37 °C. Following the incubation period, one isolated colony was transferred to 6 mL of medium (LB broth), which was incubated overnight (12–16 hours) at 37 °C. On the following day, the inoculum was prepared by diluting the bacterial overnight solutions 1:100 in 6 mL of the respective media and incubated at 37 °C until logarithmic phase (OD600 = 0.5). The devices were then placed in Petri dishes (EtO group) or glass flasks (autoclave group) with 15 mL of LB broth. Groups exposed to bacteria were inoculated with 2x106 cells mL−1 prior to sterilization. During sterilization, all samples were placed in glass flasks. Three aliquots of each condition (100 μL) were transferred to a 96-wells plate and OD600 values were quantified at 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 24 hours using the Elx808™ absorbance microplate reader (Biotek, VT, USA). After OD600 values were recorded, 10-fold serial dilutions were performed, and the dilutions were plated on LB agar plates and allowed to grow overnight at 37 °C. Afterwards, CFU counts were recorded. H2O2 gas plasma bacterial evaluation was not collected due to the damaging oxidation from sterilization, which causes functional degradation to both Ti3C2Tx films and devices.

Statistical Analysis.

Effect size was used as the primary indication of sterilization-induced degradation. The effect size provides a quantitative indication of changes in impedance and conductivity after sterilization, as opposed to the binary p-value indication of whether the data is statistically different in the initial and final cases because it calculates the change in the device performances as a metric of the standard deviation of the pre-sterilization distribution.57 The expression of the effect size is shown below, where and are the means, and are the sample sizes, and and are the standard deviations for the pre and post distributions, respectively. As an additional direct statistical test, we also computed the confidence interval for each pre-post condition, to confirm that significant changes were consistent with the measures of effect size.

| (3) |

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by: the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants no. R01AR081062 (F.V.), R01NS121219 (F.V. and Y.G.), and U01NS113339 (M.S.B.). M.A. was supported by the National Science Foundation 870 Graduate Research Fellowship Program (NSF GRFP) under Grant No. DGE-1646737 and the U.S. Department of Education Graduate Assistance in Areas of National Need (GAANN) fellowship. B.B.M. was supported by the NSF GRFP under Grant No. DGE-1845298. This work was carried out in part at the Singh Center for Nanotechnology, part of the National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure Program, which is supported by the NSF grant NNCI-2025608. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. C.d.l.F.-N. acknowledges funding from the IADR Innovation in Oral Care Award, the Procter & Gamble Company, United Therapeutics, a BBRF Young Investigator Grant, the Nemirovsky Prize, Penn Health-Tech Accelerator Award, the Dean’s Innovation Fund from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number R35GM138201, and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA; HDTRA11810041 and HDTRA1-21-1-0014). We thank Dr. Sarah Gullbrand for the help with mechanical testing, Mr. William K.S. Ojemann for an insightful discussion on statistical analysis, the Penn ULAR staff for access and support with plasma sterilization, and MuRata Manufacturing Co., for providing the MXene material.

ABBREVIATIONS

- Pt

Platinum

- EtO

Ethylene Oxide

- n

Number of Samples/Channels

- PDMS

polydimethylsiloxane

- SEM

Scanning Electron Microscopy

- CFU

Colony Forming Units

- EIS

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy

- DC

Direct Current

- XRD

X-Ray Diffraction

- XPS

X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy

- FWHM

Full-Width at Half-Max

- OD

Optical Density

- SNR

Signal-to-Noise Ratio

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Schematics of thin-film microelectrodes and MXtrodes; SEM and EDX spectra of thin-film microelectrode and MXtrode contact; EIS of 1, 2.5, and 5 mm MXtrode devices pre and post sterilization; Raman spectra of MXtrodes; sterilization-induced Raman A1g(C) peak shape and amplitude change in thin-film microelectrodes and MXtrode devices; blue-shifting and attenuating A1g(C) peak in Raman of H2O2 sterilized thin-film samples; XPS survey spectra and core-level Ti 2p and C 1s spectra for thin-film devices and MXtrodes; SEM and EDX spectra of sterilized thin-film contacts; SEM of sterilized MXtrode contacts; cyclic deformation and tensile stress strain curves for MXtrode composites; optical density of bacterial assays; impedance and conductivity values pre and post sterilization with effect size and confidence intervals; d-spacing and peak location from XRD patterns; quantification from Ti 2p and C 1s curve-fitting of XPS spectra.

Conflict of Interest Statement

F.V. and Y.G. are co-inventors on international patent application No. PCT/US2018/051084, “Implantable devices using 2D metal carbides and nitrides (MXenes).” F.V. is a co-inventor on U.S. provisional patent application No. PCT/US2018/051084, “Rapid manufacturing of absorbent substrates for soft, conformable sensors and conductors”. C.d.l.F.-N. provides consulting services to Invaio Sciences and is a member of the Scientific Advisory Boards of Nowture S.L. and Phare Bio. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Spencer R. Averbeck, Department of Bioengineering, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 19104, USA; Center for Neuroengineering and Therapeutics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 19104, USA.

Doris Xu, Department of Bioengineering, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 19104, USA; Center for Neuroengineering and Therapeutics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 19104, USA..

Brendan B. Murphy, Department of Bioengineering, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 19104, USA; Center for Neuroengineering and Therapeutics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 19104, USA.

Kateryna Shevchuk, Department of Material Science and Engineering, Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 19104, USA; A.J Drexel Nanomaterials Institute, Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 19104, USA..

Sneha Shankar, Department of Bioengineering, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 19104, USA; Center for Neuroengineering and Therapeutics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 19104, USA..

Mark Anayee, Department of Material Science and Engineering, Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 19104, USA; A.J Drexel Nanomaterials Institute, Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 19104, USA..

Marcelo Der Torossian Torres, Department of Bioengineering, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 19104, USA; Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 19104, USA; Departments of Psychiatry and Microbiology, Perelman School of Medicine University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 19104, USA; Institute for Biomedical Informatics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 19104, USA..

Michael S. Beauchamp, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 19104, USA.

Cesar de la Fuente-Nunez, Department of Bioengineering, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 19104, USA; Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 19104, USA; Departments of Psychiatry and Microbiology, Perelman School of Medicine University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 19104, USA; Institute for Biomedical Informatics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 19104, USA..

Yury Gogotsi, Department of Material Science and Engineering, Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 19104, USA; A.J Drexel Nanomaterials Institute, Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 19104, USA..

Flavia Vitale, Department of Bioengineering, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 19104, USA; Center for Neuroengineering and Therapeutics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 19104, USA; Department of Neurology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 19104, USA; Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 19104, USA; Center for Neurotrauma, Neurodegeneration, and Restoration, Corporal Michael J. Crescenz Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 19104, USA..

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the authors.

REFERENCES

- (1).Vitale F; Litt B Bioelectronics: The Promise of Leveraging the Body’s Circuitry to Treat Disease. Bioelectronics in Medicine 2018, 1, 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Arya R; Wilson JA; Fujiwara H; Rozhkov L; Leach JL; Byars AW; Rose DF Presurgical Language Localization with Visual Naming Associated ECoG High-Gamma Modulation in Pediatric Drug-Resistant Epilepsy. Epilepsia 2017, 58, 663–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Okun MS Deep-Brain Stimulation for Parkinson’s Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2012, 367, 1529–1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Mayberg HS; Lozano AM; Voon V; McNeely HE; Seminowicz D; Hamani C; Kennedy SH Deep Brain Stimulation for Treatment-Resistant Depression. Neuron 2005, 45, 651–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Frigo C; Crenna P Multichannel SEMG in Clinical Gait Analysis: A Review and State-of-the-Art. Clinical Biomechanics 2009, 24, 236–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Dhanasingh A; Jolly C An Overview of Cochlear Implant Electrode Array Designs. Hearing Research 2017, 356, 93–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Taplin AM; de Pesters A; Brunner P; Hermes D; Dalfino JC; Adamo MA; Schalk G Intraoperative Mapping of Expressive Language Cortex using Passive Real-Time Electrocorticography. Epilepsy & Behavior Case Reports 2016, 5, 46–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Sahyouni R; Chang DT; Moshtaghi O; Mahmoodi A; Djalilian HR; Lin HW Functional and Histological Effects of Chronic Neural Electrode Implantation. Laryngoscope Investigative Otolaryngology 2017, 2, 80–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Harris AR Current Perspectives on the Safe Electrical Stimulation of Peripheral Nerves with Platinum Electrodes. Bioelectronics in Medicine 2020, 3, 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Wellman SM; Eles JR; Ludwig KA; Seymour JP; Michelson NJ; McFadden WE; Kozai TD A Materials Roadmap to Functional Neural Interface Design. Advanced Functional Materials 2018, 28, 1701269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Patel PR; Welle EJ; Letner JG; Shen H; Bullard AJ; Caldwell CM; Chestek CA Utah Array Characterization and Histological Analysis of a Multi-Year Implant in Non-Human Primate Motor and Sensory Cortices. Journal of Neural Engineering 2022, 20, 014001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Garg R; Gopalan DP; de la Barrera SC; Hafiz H; Nuhfer NT; Viswanathan V; Cohen-Karni T Electron Transport in Multidimensional Fuzzy Graphene Nanostructures. Nano Letters 2019, 19, 5335–5339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Driscoll N; Rosch RE; Murphy BB; Ashourvan A; Vishnubhotla R; Dickens OO; Vitale F Multimodal in Vivo Recording using Transparent Graphene Microelectrodes Illuminates Spatiotemporal Seizure Dynamics at the Microscale. Communications Biology 2021, 4,1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Lu Y; Lyu H; Richardson AG; Lucas TH; Kuzum D Flexible Neural Electrode Array Based on Porous Graphene for Cortical Microstimulation and Sensing. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Wang K; Fishman HA; Dai H; Harris JS Neural Stimulation with a Carbon Nanotube Microelectrode Array. Nano Letters 2006, 6, 2043–2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Lu L; Fu X; Liew Y; Zhang Y; Zhao S; Xu Z; Duan X Soft and MRI Compatible Neural Electrodes from Carbon Nanotube Fibers. Nano Letters 2019, 19, 1577–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Simpson DA; Morrisroe E; McCoey JM; Lombard AH; Mendis DC; Treussart F; Hollenberg LC Non-Neurotoxic Nanodiamond Probes for Intraneuronal Temperature Mapping. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 12077–12086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Tchoe Y; Bourhis AM; Cleary DR; Stedelin B; Lee J; Tonsfeldt KJ; Dayeh SA Human Brain Mapping with Multithousand-Channel PtNRGrids Resolves Spatiotemporal Dynamics. Science Translational Medicine 2022, 14, 1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Driscoll N; Dong R; Vitale F Emerging Approaches for Sensing and Modulating Neural Activity Enabled by Nanocarbons and Carbides. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2021, 72, 76–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Garg R; Vitale F Latest Advances on MXenes in Biomedical Research and Healthcare. MRS Bulletin 2023, in press. DOI: 10.1557/s43577-023-00480-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Vitale F; Driscoll N; Murphy BB Biomedical Applications of MXenes. In 2D Metal Carbides and Nitrides (MXenes); eds. Anasori B; Gogotsi Y; Springer, Cham: ; 2019; pp. 503–524 [Google Scholar]

- (22).Kim SJ; Koh HJ; Ren CE; Kwon O; Maleski K; Cho SY; Jung HT Metallic Ti3C2Tx MXene Gas Sensors with Ultrahigh Signal-to-Noise Ratio. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 986–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Xie X; Zhao MQ; Anasori B; Maleski K; Ren CE; Li J; Gogotsi Y Porous Heterostructured MXene/Carbon Nanotube Composite Paper with High Volumetric Capacity for Sodium-Based Energy Storage Devices. Nano Energy 2016, 26, 513–523. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Alhabeb M; Maleski K; Anasori B; Lelyukh P; Clark L; Sin S; Gogotsi Y Guidelines for Synthesis and Processing of Two-Dimensional Titanium Carbide (Ti3C2Tx MXene). Chemistry of Materials 2017, 29, 7633–7644. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Dai C; Lin H; Xu G; Liu Z; Wu R; Chen Y Biocompatible 2D Titanium Carbide (MXenes) Composite Nanosheets for pH-Responsive MRI-Guided Tumor Hyperthermia. Chemistry of Materials 2017, 29, 8637–8652. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Rasool K; Mahmoud KA; Johnson DJ; Helal M; Berdiyorov GR; Gogotsi Y Efficient Antibacterial Membrane Based on Two-Dimensional Ti3C2Tx (MXene) Nanosheets. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Rasool K; Helal M; Ali A; Ren CE; Gogotsi Y; Mahmoud KA Antibacterial Activity of Ti3C2Tx MXene. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 3674–3684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Seyedin S; Uzun S; Levitt A; Anasori B; Dion G; Gogotsi Y; Razal JM MXene Composite and Coaxial Fibers with High Stretchability and Conductivity for Wearable Strain Sensing Textiles. Advanced Functional Materials 2020, 30, 1910504. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Murphy BB; Mulcahey PJ; Driscoll N; Richardson AG; Robbins GT; Apollo NV; Vitale F A Gel-Free Ti3C2Tx-Based Electrode Array for High-Density, High-Resolution Surface Electromyography. Advanced Materials Technologies 2020, 5, 2000325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Driscoll N; Erickson B; Murphy BB; Richardson AG; Robbins G; Apollo NV; Vitale F MXene-Infused Bioelectronic Interfaces for Multiscale Electrophysiology and Stimulation. Science Translational Medicine 2021, 13, 8629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Driscoll N; Richardson AG; Maleski K; Anasori B; Adewole O; Lelyukh P; Vitale F Two-Dimensional Ti3C2 MXene for High-Resolution Neural Interfaces. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 10419–10429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Driscoll N; Maleski K; Richardson AG; Murphy BB; Anasori B; Lucas TH; Vitale F Fabrication of Ti3C2 MXene Microelectrode Arrays for in vivo Neural Recording. JoVE (Journal of Visualized Experiments) 2020, 156, e60741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Ni M; Chen J; Wang C; Wang Y; Huang L; Xiong W; Fei J A High-Sensitive Dopamine Electrochemical Sensor Based on Multilayer Ti3C2 MXene, Graphitized Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes and ZnO Nanospheres. Microchemical Journal 2022, 178, 107410. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Shahzad F; Iqbal A; Zaidi SA; Hwang SW; Koo CM Nafion-Stabilized Two-Dimensional Transition Metal Carbide (Ti3C2Tx MXene) as a High-Performance Electrochemical Sensor for Neurotransmitter. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 2019, 79, 338–344. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Wang Y; Garg R; Hartung JE; Goad A; Patel DA; Vitale F; Cohen-Karni T Ti3C2Tx MXene Flakes for Optical Control of Neuronal Electrical Activity. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 14662–14671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Rutala WA; Weber DJ Guideline for Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities. Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC), Center for Disease Control (CDC) 2008, https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/47378. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Jagadeeswaran I; Chandran S ISO 11135: Sterilization of Health-Care Products—Ethylene Oxide, Requirements for Development, Validation and Routine Control of a Sterilization Process for Medical Devices. In Medical Device Guidelines and Regulations Handbook Cham; Springer International Publishing, 2022; pp. 145–153. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Garg R; Driscoll N; Shankar S; Hullfish T; Anselmino F; Iberite F; Averbeck S; Vitale F Wearable High-Density MXene-Bioelectronics for Neuromuscular Diagnostics, Rehabilitation, and Assistive Technologies. Small Methods 2023, 2201318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Boehler C; Carli S; Fadiga L; Stieglitz T; Asplund M Tutorial: Guidelines for Standardized Performance Tests for Electrodes Intended for Neural Interfaces and Bioelectronics. Nature Protocols 2020, 15, 3557–3578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Franks W; Schenker I; Schmutz P; Hierlemann A Impedance Characterization and Modeling of Electrodes for Biomedical Applications. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2005, 52, 1295–1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Li Z; Wang L; Sun D; Zhang Y; Liu B; Hu Q; Zhou A Synthesis and Thermal Stability of Two-Dimensional Carbide MXene Ti3C2. Materials Science and Engineering 2015, 191, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Holder CF; Schaak RE Tutorial on Powder X-ray Diffraction for Characterizing Nanoscale Materials. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 7359–7365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Lotfi R; Naguib M; Yilmaz DE; Nanda J; Van Duin AC A Comparative Study on the Oxidation of Two-Dimensional Ti3C2 MXene Structures in Different Environments. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2018, 6, 12733–12743. [Google Scholar]

- (44).Ahmed B; Anjum DH; Hedhili MN; Gogotsi Y; Alshareef HN H2O2 Assisted Room Temperature Oxidation of Ti2C MXene for Li-ion Battery Anodes. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 7580–7587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Sarycheva A; Gogotsi Y Raman Spectroscopy Analysis of the Structure and Surface Chemistry of Ti3C2Tx MXene. Chemistry of Materials 2020, 32, 3480–3488. [Google Scholar]

- (46).Rakhi RB; Ahmed B; Hedhili MN; Anjum DH; Alshareef HN Effect of Post-Etch Annealing Gas Composition on the Structural and Electrochemical Properties of Ti2CTx MXene Electrodes for Supercapacitor applications. Chemistry of Materials 2015, 27, 5314–5323. [Google Scholar]

- (47).Johnson D; Hansen K; Yoo R; Djire A Elucidating the Charge Storage Mechanism on Ti3C2 MXene through In Situ Raman Spectroelectrochemistry. ChemElectroChem 2022, 9, e202200555. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Ghassemi H; Harlow W; Mashtalir O; Beidaghi M; Lukatskaya MR; Gogotsi Y; Taheri ML In Situ Environmental Transmission Electron Microscopy Study of Oxidation of Two-Dimensional Ti3C2 and Formation of Carbon-Supported TiO2. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2014, 2, 14339–14343. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Adar F; Lee E; Mamedov S; Whitley A Experimental Evaluation of the Depth Resolution of a Raman Microscope. Microscopy and Microanalysis 2010, 16, 360–361. [Google Scholar]

- (50).Biesinger MC; Payne BP; Grosvenor AP; Lau LW; Gerson AR; Smart RSC Resolving Surface Chemical States in XPS Analysis of First Row Transition Metals, Oxides and Hydroxides: Cr, Mn, Fe, Co and Ni. Applied Surface Science 2011, 257, 2717–2730. [Google Scholar]

- (51).Shuck CE; Sarycheva A; Anayee M; Levitt A; Zhu Y; Uzun S; Gogotsi Y Scalable Synthesis of Ti3C2Tx MXene. Advanced Engineering Materials 2020, 22, 1901241. [Google Scholar]

- (52).Chae Y; Kim SJ; Cho SY; Choi J; Maleski K; Lee BJ; Ahn CW An Investigation into the Factors Governing the Oxidation of Two-Dimensional Ti3C2 MXene. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 8387–8393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Uguz I; Ganji M; Hama A; Tanaka A; Inal S; Youssef A; Malliaras GG Autoclave Sterilization of PEDOT: PSS Electrophysiology Devices. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2016, 5, 3094–3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Chiang CH; Won SM; Orsborn AL; Yu KJ; Trumpis M; Bent B; Viventi J Development of a Neural Interface for High-Definition, Long-term Recording in Rodents and Nonhuman Primates. Science Translational Medicine 2020, 12, eaay4682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Michalowski PP; Anayee M; Mathis TS; Kozdra S; Wójcik A; Hantanasirisakul K; Gogotsi Y Oxycarbide MXenes and MAX Phases Identification using Monoatomic Layer-by-Layer Analysis with Ultralow-Energy Secondary-Ion Mass Spectrometry. Nature Nanotechnology 2022, 17, 1192–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Näslund LÅ; Persson I XPS Spectra Curve Fittings of Ti3C2Tx Based on First Principles Thinking. Applied Surface Science 2022, 593, 153442. [Google Scholar]

- (57).Nakagawa S; Cuthill IC Effect Size, Confidence Interval and Statistical Significance: A Practical Guide for Biologists. Biological Reviews 2007, 82, 591–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the authors.