Abstract

Background

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS)-based prediction of drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis has the potential to guide clinical decisions in the design of optimal treatment regimens.

Methods

We utilized WGS to investigate drug resistance mutations in a 32-year-old Tanzanian male admitted to Kibong’oto Infectious Diseases Hospital with a history of interrupted multidrug-resistant tuberculosis treatment for more than three years. Before admission, he received various all-oral bedaquiline-based multidrug-resistant tuberculosis treatment regimens with unfavourable outcomes.

Results

Drug susceptibility testing of serial M. tuberculosis isolates using Mycobacterium Growth Incubator Tubes culture and WGS revealed resistance to first-line anti-TB drugs, bedaquiline, and fluoroquinolones but susceptibility to linezolid, clofazimine, and delamanid. WGS of serial cultured isolates revealed that the Beijing (Lineage 2.2.2) strain was resistant to bedaquiline, with mutations in the mmpR5 gene (Rv0678. This study also revealed the emergence of two distinct subpopulations of bedaquiline-resistant tuberculosis strains with Asp47f and Glu49fs frameshift mutations in the mmpR5 gene, which might be the underlying cause of prolonged resistance. An individualized regimen comprising bedaquiline, delamanid, pyrazinamide, ethionamide, and para-aminosalicylic acid was designed. The patient was discharged home at month 8 and is currently in the ninth month of treatment. He reported no cough, chest pain, fever, or chest tightness but still experienced numbness in his lower limbs.

Conclusion

We propose the incorporation of WGS in the diagnostic framework for the optimal management of patients with drug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis.

Keywords: Whole-genome sequencing, XDR-TB, Genomic Diagnostics, Case Report, Clinical application

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is a highly contagious bacterial disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. TB has been a significant global health concern for centuries, and it continues to be a major cause of illness and death worldwide [1]. The discovery of streptomycin in the mid-20th century marked a turning point in TB treatment, making it one of the first diseases to be treated with antibiotics [2, 3]. However, over time, strains of TB have developed resistance to various antibiotics, leading to the emergence of drug-resistant (DR) forms of the disease [4–8].

Multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) is defined as TB that is resistant to rifampicin and isoniazid [9]. In addition, pre-extensively drug-resistant TB (Pre-XDR-TB) is a TB that is resistant to rifampicin and any fluoroquinolone (a class of second-line anti-TB drugs) [9]. Extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB) is the most severe form of drug-resistant TB and is defined as TB resistant to rifampicin plus any fluoroquinolone and to at least one of either bedaquiline or linezolid [9]. Recently, limited treatment options [10], increased treatment complexity and cost [11], increased rates of treatment failure and mortality [12], and the potential for further transmission of resistant strains [13] of drug-resistant TB (DR-TB) have been of great concern because they can undermine TB control efforts globally. Healthcare systems need to strengthen TB surveillance, improve diagnostic capabilities, ensure access to effective treatment regimens, and implement infection control measures to prevent the spread of DR-TB strains [14, 15].

The emergence of XDR-TB is primarily attributed to the improper use of antibiotics in TB treatment, inadequate supervision of treatment regimens, and a lack of comprehensive healthcare systems. The prevalence of XDR-TB varies across different regions, with higher rates found in parts of Eastern Europe, Asia, and Africa [9]. In Tanzania, the trend of MDR/Pre-XDR-TB notifications has been increasing in the past 7 years, with a slight decrease between 2019 and 2021 [16]. According to the Tanzania National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Programme (NTLP) 2021 report, 6 Pre-XDR-TB patients were detected among 442 RR/MDR/Pre-XDR-TB patients identified in 2021 [16].

Efforts to address pre-XDR-TB include improving diagnostic capabilities, enhancing surveillance systems, developing new drugs and treatment regimens, and strengthening healthcare infrastructure to ensure proper treatment and prevent further spread [17, 18]. Combating pre-XDR-TB and XDR-TB requires a multifaceted approach involving international collaboration, research, healthcare system strengthening, and addressing socioeconomic factors that contribute to its persistence and spread.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has established guidelines for the disease diagnosis and management of TB. Clinical diagnosis of DR-TB in Tanzania, as reported in other resource-limited countries, relies on microscopy, culture, and molecular diagnostic assays such as the Xpert MTB/RIF and line probe assays. Molecular assays such as the Xpert MTB/RIF and line probe assays have more variable sensitivities for TB detection [19, 20]. In developed countries with robust healthcare systems, WGS plays a pivotal role in augmenting diagnostic accuracy and treatment precision for DR-TB patients [21–24]. However, in low-income settings with high TB incidences, the clinical application of WGS for the diagnosis and management of DR-TB patients can be challenging due to obstacles such as limited infrastructure, cost constraints, and technical expertise [23–25].

This case study presents the case of a patient with TB who first presented with MDR-TB but, due to inadequate adherence to treatment, evolved to XDR-TB. To understand the microevolution of the XDR-TB infection, this study investigated the evolutionary changes in M. tuberculosis in eight isolates obtained over two consecutive years (Table 1) by using WGS. This study reports the genotypic mutations and microevolution of two distinct XDR subpopulations from the same strain in serial isolates and highlights the potential of WGS in shaping the management and control of XDR-TB.

Table 1.

Serial sputum samples collection dates

| Sputum Sample ID | Collection Date |

|---|---|

| 1 | May 2021 |

| 2 | June 2021 |

| 3 | April 2022 |

| 24 | June 2022 |

| 4 | August 2022 |

| 5 | October 2022 |

| 6 | November 2022 |

| 7 | March 2023 |

Case presentation

A 32-year-old man from Tanzania was transferred to Kibong’oto Infectious Diseases Hospital after his second-line treatment for drug-resistant TB had failed for 16 months. Upon admission, he exhibited symptoms including a productive cough, chest pain, chest tightness, fever, and weight loss. Microscopy and LJ cultures yielded positive results. He had no prior history of HIV, diabetes, or hypertension and did not smoke cigarettes or drink alcohol.

During the physical examination, the patient exhibited normal vital signs, including a normal temperature (36.7 °C), pulse rate (73 bpm), blood pressure (117/71 mmHg), oxygen saturation of 97% on room air, and respiration rate (17 breaths/minute). His weight was 65 kg, and his height was 1.69 m, equivalent to a body mass index of 23 kg/m2. Respiratory examination revealed decreased air entry into the left chest. His electrocardiogram, liver and kidney function tests and electrolyte levels were all within the normal range. However, he presented with leukocytosis, neutrophilia (8.6), and lymphopenia (11.4%). Chest radiography revealed cavitary disease and prominent fibrotic changes in the right lung (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Chest radiography of the extensively drug resistance tuberculosis patient

Since his initial MDR-TB episode in 2019, the patient has undergone various treatment regimens for either pre-XDR-TB or XDR-TB, with inconsistent treatment durations and outcomes documented in Table 2. Monthly monitoring utilizing clinical assessments, smear microscopy, and culture in MGIT indicated improvement with the revised medications. Particularly in his current XDR-TB regimen, which was tailored based on WGS results, the patient experienced severe neuropathy associated with a high dose (1200 mg) of linezolid at month 4 of therapy, which was then reduced to 600 mg for an additional 2 months. By month 6 of XDR-TB treatment, the patient developed mild hearing loss attributed to the injection of 1 gm of amikacin. The treating clinicians adjusted the frequency of amikacin daily to three times per week until month 8 of therapy, when it was completely discontinued. The patient was discharged home at month 8 and is currently in the ninth month of treatment. He reported no cough, chest pain, fever, or chest tightness but still experienced numbness in his lower limbs.

Table 2.

The patient’s previous history of mycobacterial diagnosis, multiple treatment regimens, and inconsistent outcomes

| Years | Form of TB | Presentations | Diagnostic tool | Treatment Regimens | Progress and actions | Final outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| October 2019 | MDR-TB | TB symptoms and signs | Xpert® MTB/RIF | BDQ + LZD + LFX + PZA + CS + CFZ | • Lost to follow up after 7 months in April 2020 | Lost to follow up |

| May 2021 | MDR-TB | TB symptoms and signs reverted | Xpert® MTB/RIF, smear microscopy and culture for monitoring | BDQ + LZD + LFX + CFZ + PTO + PZA |

• Converted to culture negative at month 4 but reverted to positive at month 8 through month 14. • Phenotypic DST in LJ culture revealed resistant to isoniazid, fluoroquinolones and ethambutol but susceptible to injectable aminoglycosides (amikacin, kanamycin & capreomycin) and ethionamide |

MDR-TB Treatment failure |

| September 2022 | Pre-XDR-TB | TB symptoms and signs |

DST in LJ Culture Xpert® MTB/XDR |

BDQ + LZD + LFX + CFZ + PTO + PZA + PAS + DLM |

• Culture remained positive for 7 months from until September 2022 to April 2023 • WGS of cultured isolates performed in April 2023 revealed resistant to BDQ, CFZ, fluoroquinolones (LFX), SM, EMB, ETH, INH, and RIF. |

Pre-XDR TB treatment failure |

| April 2023 | XDR-TB | TB symptoms, signs and culture positivity | Whole genome sequencing of cultured isolates | Amikacin 1 g, LZD (1200 mg), PAS 4 mg daily, DLM 100 mg twice per day & CS 750 mg daily. | Achieved culture conversion at month 2. He has been discharged home and now at month 9. TB symptoms has resolved and culture remained negative | Continuation phase of optimize treatment regimen |

Anti-TB medicines: BDQ, bedaquiline; CFZ, Clofazimine; CS, Cycloserine; DLM, delamanid; EMB, ethambutol; ETH, Ethionamide; INH, isoniazid; LFX, Levofloxacin; LZD, Linezolid; PAS, para-amainosalicylic acid; PTO, prothionamide; PZA pyrazinamide; RIF, rifampicin and SM, streptomycin

Methods

Culture and phenotypic testing

Eight spot and early morning sputum samples from the patient were collected over two consecutive years (Table 1) and processed by Petroff’s method according to the manufacturer’s instructions [26]. The culture, identification, and DST of the XDR-TB isolates were performed at the Central Tuberculosis Reference Laboratory, Muhimbili National Hospital, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, in Mycobacterium Growth Incubator Tubes (BBL™ MGIT™ Becton–Dickinson, Sparks MD, USA) on Middlebrook 7H11 agar and selective 7H11 agar following the manufacturer’s instructions. Drug susceptibility testing (DST) was conducted in MGIT™ at the recommended critical concentrations [27].

DNA extraction and quantification

The bacteria were grown on Löwenstein–Jensen slants at 37 °C until colonies were visible. Colonies were then scraped from the surface of the solid medium using a sterile loop, suspended in 400 mL Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer, and heat-killed at 90 °C for 30 min. Genomic DNA was extracted at the Genomic Laboratory at Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences by using a modified protocol adopted from the Centre for Clinical Microbiology (CCM), University College London (UCL) [28]. Briefly, lysozyme (50 µL, 10 mg/mL), 5 µL of proteinase K (20 mg/mL), 70 µL of SDS (10% w/v) and 100 µL of prewarmed CTAB/NaCl (10% CTAB in 0.7 M NaCl) were added and then incubated at 60 °C for 10 min, 750 µL of chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (24:1 v/v) was added, and the debris was pelleted by centrifugation for 5 min at 10,000×g. Ice-cold isopropanol (450 µL) was added to the aqueous supernatants, which were subsequently centrifuged at 10,000×g for 5 min before the pellets were washed with 1 mL of 70% ethanol. DNA pellets were rehydrated in 100 µL of molecular grade water overnight at 4 °C. DNA was quantified using NanoDrop™ spectrophotometry and the Qubit™ dsDNA BR Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher). The size and integrity of the DNA fragments were confirmed using genomic DNA reagents and ScreenTape from the TapeStation 4150 (Agilent Technologies Inc.). DNA extractions were shipped to CCM and UCL for sequencing.

Library preparation and sequencing

Libraries were prepared from the MTB DNA extracts using the PathHiT protocol, which is a modification of CoronaHiT [29], for subsequent sequencing on Illumina sequencers. Sequencing of the prepared libraries was carried out in the UCL Genomics unit using a MiSeq, NextSeq 500/550 or NextSeq 2000 sequencer (Illumina) and the most appropriate sequencing kit (with a minimum of 150 cycles, i.e., generating 75 bp paired-end reads) depending on the number of samples and aiming for 100X mean read depth. Sequences were analysed at CCM and UCL and deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) (project accession number: PRJEB74918).

Bioinformatics analysis

Sequence reads were mapped to the H37Rv reference genome (RefSeq accession: NC_000962.3) using bwa mem v.0.7.17 [30], and alignments were sorted using samtools v.1.12 [31]. Site statistics were generated using BCFtools mpileup v.1.12, and gene annotations were generated using snpEff (v.4.3.1t) software [32]. Sequence purity was determined using Kraken2 [33] to exclude potential contamination with nontuberculous mycobacterial sequences. Variants in the genes conferring resistance to pretomanid and bedaquiline and upstream regions, as described in the second edition of the WHO catalogue of mutations [34], were investigated. The genotype of the drug resistance-conferring variants was determined using TB-profiler v.5.0.1/database tbdb_e25540b_Oct 26, 2023 and Mykrobe v.0.13.0 [35]. The percentage of variants of interest in the genes conferring resistance to bedaquiline was verified by viewing the BAM files against the H37Rv reference genome (RefSeq accession: NC_000962.3) using the genome viewer IGV v.2.15.2. The percentages of variants were calculated from the proportion of sequence reads showing variants of interest in relation to the sequence depth at the corresponding genomic position. Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed using IQ-TREE (v2.0.3) with a general time reversible model of nucleotide substitution (model selection restricted to those supported by RAxML); branch support values were determined using 1000 bootstrap replicates) [36]. Phylogenetic comparisons for the tree construction filter out all mixed sites and INDELS.

Results

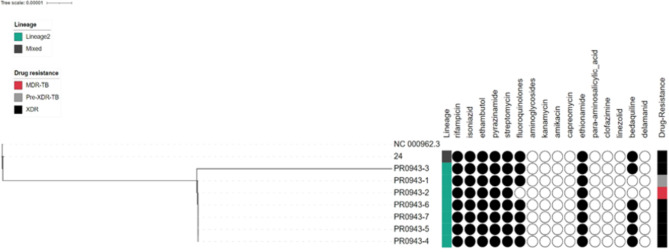

WGS analysis revealed that all eight (8) serial isolates were pure M. tuberculosis; lineage 2 (Beijing); sublineage 2.2, with good coverage > 99.5% and a mean depth of sequencing ≥ 100 x. All isolates, apart from isolate number 24, were closely related to very small genetic distances in the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 2). According to the sequence data for isolate number 24, 7% of the reads were classified as lineage 4 (Latin American Mediterranean, LAM). The results also indicated that the MTB evolved from MDR to Pre-XDR to XDR (Fig. 2). Subsequent resistance mutations in the gyrA gene (p.Asp94Gly) against moxifloxacin gave rise to pre-XDR strains, and further mutations in gyrA (p.Asp94Gly) against the levofloxacin gene facilitated the emergence of XDR strains.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic relationship between the eight serial M. tuberculosis isolates collected over two years from the presented case and genotypic drug resistance pattern: black circle: drug resistant variants were detected, white circles: susceptible

WGS revealed the presence of mutations conferring resistance to the following anti-tuberculosis drugs: rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, ethambutol, streptomycin, fluoroquinolones, ethionamide, cycloserine, clofazimine, and bedaquiline in all the serially tested isolates. Mutations were detected in the rpoB, katG, pncA, embB, gid, gyrA, ethA, ald and mmpR5 genes. The specific variants involved in drug resistance are listed in Table 3. A subpopulation (17%) of the 6th (PR0943-5) and 7th (PR0943-6) isolates developed a frameshift mutation in the ald gene due to the duplication of 2 “GC” bases in coding positions 436–437 of the gene, which is associated with resistance to cycloserine.

Table 3.

Comparison of genotypic and phenotypic drug resistance profiles of M. tuberculosis strains using whole genome sequencing

| Drugs | Genotype | Genotypic mutations in drug targets | Phenotypic DST | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample ID | PR0943-1 | PR0943-2 | PR0943-3 | PR0943-24 | PR0943-4 | PR0943-5 | PR0943-6 | PR0943-7 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 24 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Isoniazid | katG | p.Ser315Thr | p.Ser315Thr | p.Ser315Thr | p.Ser315Thr | p.Ser315Thr | p.Ser315Thr | p.Ser315Thr | p.Ser315Thr | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R |

| Rifampicin | rpoB | p.Ser450Leu | p.Ser450Leu | p.Ser450Leu | p.Ser450Leu | p.Ser450Leu | p.Ser450Leu | p.Ser450Leu | p.Ser450Leu | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R |

| Ethambutol | embB |

p.Gln497Lys p.Met306Ile |

Gln497Lys Met306Ile |

p.Gln497Lys p.Met306Ile |

p.Gln497Lys p.Met306Ile |

p.Gln497Lys p.Met306Ile |

p.Gln497Lys p.Met306Ile |

p.Gln497Lys p.Met306Ile |

p.Gln497Lys p.Met306Ile |

R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R |

| Pyrazinamide | pncA | p.Cys14Arg | Cys14Arg | p.Cys14Arg | p.Cys14Arg | p.Cys14Arg | p.Cys14Arg | p.Cys14Arg | p.Cys14Arg | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R |

| Streptomycin |

gid rrs |

p.Leu79Ser n.514 A > C |

Leu79Ser n.514 A > C |

p.Leu79Ser n.514 A > C |

p.Leu79Ser n.514 A > C |

p.Leu79Ser n.514 A > C |

p.Leu79Ser n.514 A > C |

p.Leu79Ser n.514 A > C |

p.Leu79Ser n.514 A > C |

R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R |

| Flouroquinolones | gyrA | p.Ala90Val (10%) * | - | p.Asp94Gly | p.Asp94Gly | p.Asp94Gly | p.Asp94Gly | p.Asp94Gly | p.Asp94Gly | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R |

| Bedaquiline |

MmpR5 (Rv0678) |

- | - |

- c.139_140dup GA; p.Asp47f |

c.139_140dupGA; p.Asp47fs |

c.139_140dupGA; p. Asp47fs c.144dupC; p.Glu49fs |

c.139_140dupGA; p.Asp47fs c.144dupC; p.Glu49fs |

c.139_140dupGA; p.Asp47fs c.144dupC; p.Glu49fs |

c.139_140dupGA; p.Asp47fs c.144dupC; p.Glu49fs |

S | S | S | S | S | S | R | S |

| Clofazimine | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | |

| Delamanid | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | |

| Levofloxacin | gyrA | p.Ala90Val (10%) * | - | p.Asp94Gly | p.Asp94Gly | p.Asp94Gly | p.Asp94Gly | p.Asp94Gly | p.Asp94Gly | S | S | S | S | R | S | R | R |

| Linezolid | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | |

S = culture sensitive

R = culture resistant

*% variant

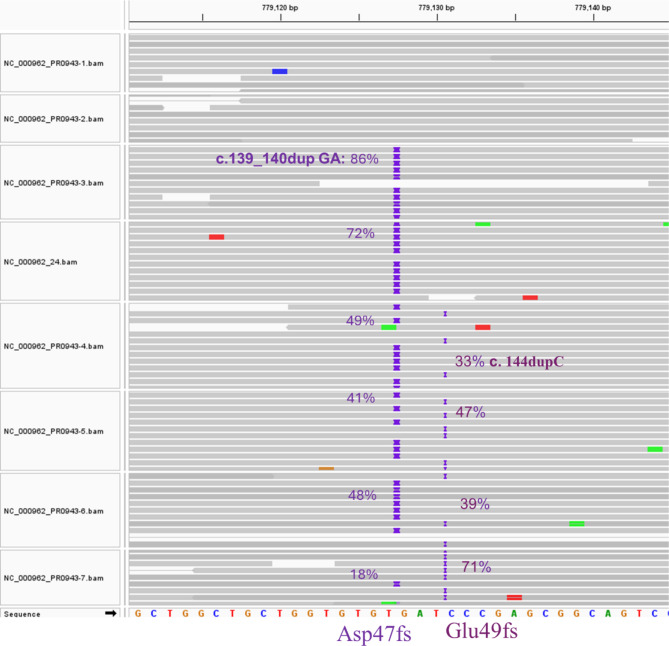

Longitudinal analysis of the eight serial isolates over two years revealed a dynamic picture of the evolution of resistance to bedaquiline, fluoroquinolones and cycloserine in the M. tuberculosis population. The evolution of bedaquiline resistance started in the third isolate (PR0943-3) through the emergence of a subpopulation with a frameshift mutation (Asp47f) in the mmpR5 gene (Rv 0678) due to the insertion of 2 bases, “GA”, at positions 139–140 in the coding region of the gene. Another distinct subpopulation emerged in the fifth isolate (PR0943-4) with a frameshift mutation (Glu49fs) in the mmpR5 gene (Rv 0678) due to the insertion of a cytosine at position 144 in the coding region of the gene. No single read in the six serial isolates carried both alleles on the same sequencing read (Fig. 3), which indicates that these were two distinct subpopulations. Over time, the first subpopulation diminished, with the frequency of the reads carrying this allele gradually declining in the subsequent isolates, while the second subpopulation increased gradually and predominated the population in the eighth isolate (PR0943-7), with an allele frequency reaching 71% (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The evolution Bedaquiline resistance in the presented case through the emergence of two distinct subpopulations; the first developed Asp47fs mutation through insertion of 2 bases “GA” at genomic position 779,127 and the second with Glu49fs through insertion of 1 base “C” at genomic position 779,130. Across the subsequent M. tuberculosis isolates the first subpopulation was diminishing while the second was rising; the percentages of both variants are displayed on each sequence pane next to the corresponding mutation position

The genotypic mutations detected in the gyrA gene are associated with resistance to fluoroquinolones. In the first isolate (PR0943-1), 10% of the reads showed a variant of gyrA with the missense mutation Ala90Val, and this subpopulation was eliminated in the second isolate, PR0943-2. Starting from the third isolate (PR0943-3), another variant of the gyrA gene, Asp94Gly, associated with fluoroquinolone resistance, evolved and continued to persist across the subsequent isolates.

For cycloserine resistance, a subpopulation (17%) emerged in the 6th (PR0943-5) and 7th (PR0943-6) isolates with a frameshift mutation in the ald gene due to the duplication of the 2-base “GC” in coding position 436–437 of the gene but was subsequently eliminated in the eighth isolate (PR0943-7).

Discussion

In this study, we analysed a series of eight isolates of the same strain that were collected consecutively from one patient who first presented with MDR-TB and developed XDR-TB over the course of treatment due to a history of intermittent treatment and noncompliance.

This study also investigated the genotypes and phylogenetic relationships of the isolates and revealed that all the XDR-TB isolates belonged to the Beijing (lineage 2.2) strain (Fig. 2), which has been associated with the spread of MDR-TB and unfavourable treatment outcomes [37]. The Beijing TB genotype is not common in Tanzania [38, 39], but documented TB isolates in Tanzania indicate that the Beijing genotype has been established among TB patients in Tanzania.

The present study revealed that the phenotypic DST and WGS results of M. tuberculosis clinical isolates were concordant for isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, streptomycin, pyrazinamide, and fluoroquinolones among all eight isolates. However, there was a discrepancy between the phenotypic DST and genotypic drug resistance patterns for bedaquiline in isolates PR0943-3, PR0943-24, PR0943-5 and PR0943-7 and for levofloxacin in isolates 3rd PR0943-3, 4th PR0943-24, and 6th PR0943-5 (Table 3). This could be explained by the emergence of the subpopulation with the variants conferring resistance to these classes of antibiotics and the relatively low proportions in the early isolates. The latter isolates were found to be phenotypically resistant by DST.

With respect to fluoroquinolones, both variants, gyrA_p. Ala90Val and gyrA_p. Asp94Gly is classified as a group 1 gene associated with resistance to levofloxacin and moxifloxacin; however, the former was reported to be associated with a low level of resistance to moxifloxacin, and the latter persisted with a high level of resistance to moxifloxacin.

The serial isolates from the present patient developed mutations in the mmpR5 (Rv0678) gene encoding the MmpR5 repressor protein over time, and variants of mmpR5 are associated with resistance to bedaquiline and clofazimine. Recently, it was reported that not all frameshift mutations in mmpR5 (Rv0678) cause loss of function of the protein and may not confer resistance to bedaquiline [40]. However, the two variants detected in our patient were associated with resistance, especially the latter. The former variant in mmpR5_p. Asp47f detected in the first subpopulation resistant to bedaquiline is classified as group 1 (the variants associated with resistance) for bedaquiline and group 2 (variants associated with resistance-intrem) for clofazimine in the second version of the WHO catalogue of drug resistance mutations in M. tuberculosis (2023). The latter variant mmpR5_p. Glu49fs is classified as group 1 and is associated with resistance to bedaquiline and clofazimine.

Genotypic mutations in the mmpR5 (Rv0678) gene in bedaquiline before exposure to clofazimine have been identified in settings with limited prior use of bedaquiline [41]. However, there is limited knowledge about the mechanisms of action, drug susceptibility, pharmacokinetics, resistance mechanisms, and cross-resistance of bedaquiline and clofazimine [42].

Neither the TB profiler nor Mykrobe predicted resistance to either bedaquiline or clofazimine. Nevertheless, the variants identified in our longitudinal subpopulation analysis are likely the mechanism for bedaquiline resistance (BDQ-R), especially because the patient did not respond to bedaquiline treatment. We detected 144dupC in some of the clinical trials in a BDQ-R isolate, which has been reported elsewhere [43–46]. Even using the most sensitive approach possible, where any mutation in any of the genes that have been identified as potentially associated with bedaquiline resistance is assumed to be resistance-conferring, only approximately half (49–69%) of bedaquiline resistance genes were identified [41]. In other studies, mutations in mmpR5 were significantly associated with resistance according to minimum inhibitory concentration tests [41].

The history of the patient involved the transfer from a health centre, signifying the non-responsiveness of the patient to the prescribed individualized treatment regimen. The patient was reported to be culture positive after receiving TB treatment at KIDH and presented with cough, chest pain, chest tightness, fever, and weight loss, indicating failure of the prescribed current regimen. Unresponsiveness to the treatment regimen might be attributed to nonadherence to the regimen, as evidenced by reports including loss to follow-up. As observed in phenotypic DST, resistance to clofazimine was not observed in any of the isolates. However, resistance to bedaquiline was detected phenotypically in the later isolates, and WGS demonstrated the evolution of bedaquiline resistance in this patient, emphasizing the importance of WGS. As revealed by the WGS results, acquired resistance to bedaquiline, as evidenced by the emergence of subpopulations of MDR-TB strains, requires the inclusion of drugs with high resistance preventing capacity through high and early bactericidal activity [47]. The United Republic of Tanzania is among the 124 countries that have adopted bedaquiline as a treatment regimen for DR-TB. The management of XDRTB patients is challenging, and there are implications associated with the management of XDR-TB patients, including limited treatment options, potential for transmission, and the importance of infection control measures. Thus, the detection of bedaquiline resistance at the infant stage of its use in the management of TB in the country advocates for early confirmation of drug resistance in TB patients by obtaining specimens for culture and DST. It is recommended that implementing rigorous infection control measures, including proper isolation and ventilation, is vital to prevent the spread of XDRTB to naive individuals.

Management of XDR-TB patients with few alternative regimens, very sick patients and a long lead time for phenotypic data to guide therapy is challenging. Here, we highlight the role of WGS as a tool for the detection of TB resistance, particularly the detection of otherwise missed and initially reported sensitive isolates. More work is required to confirm the utility of WGS in routine clinical practice for the management of DR-TB in resource-limited settings. Despite challenges such as a lack of expertise and financial capabilities in the application of WGS in the diagnosis and management of DR-TB patients in resource-limited countries, WGS is rewarding in terms of profiling the evolution of drug resistance, providing guidance for personalized treatment in patients [48], and enabling a more appropriate and accurate choice of regimen [20].

Acknowledgements

The authors of this study extend sincere gratitude to Dr. Amos Nungu, the Director General, Tanzania Commission for Science and Technology, for granting permission to the principal investigator to conduct this study. We are profoundly grateful to the study participants recruited at KIDH whose willingness to engage in our study was instrumental in its success. The staff at the Genomic Laboratory, University College London, are acknowledged for their expertise in sequencing the MDRTB isolates. Furthermore, we acknowledge the assistance provided by the Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences Genomic Laboratory staff, particularly Dr. Teddy Mselle, for logistic support during the extraction of DNA. Library preparation and sequencing were carried out at UCL Genomics, Genetics & Genomic Medicine Research & Teaching Dept, UCL GOS Institute of Child Health.

Author contributions

BZK involved in conceptualization, study design, drafted the main manuscript, SR focused on genomic data analysis, prepared Figs. 2 and 3, LE involved in genomic sequencing, EVM conceptualized the study, SGM, GAS, JAR and PMM were focused on clinical management and treatment outcomes of the patient, DM and MGM were involved in sample processing and analysis, CW and RW were involved in Genome sequencing, TDM and MIM were involved in conceptualization, supervision.

Funding

This study is funded by the EDCTP2 programme supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme as part of the EDCTP research career fellowship (TMA2018CDF-2363).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethical approval for the observational study was obtained from the National Institute for Medical Research with the reference NIMR/HQ/R.8a/Vol. IX/3600, and a written informed consent to use the chest radiography obtained in the diagnosis of the extensively drug resistance tuberculosis was obtained from the patient. The research permit to conduct the study was obtained from the Tanzania Commission for Science and Technology (COSTECH) with reference number CST00000286-2023-2024-00049. This study is also registered in the ISRCTN registry as ISRCTN14635089. The study was registered in the ISRTCN registry on 06/03/2024.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.WHO. Global Tuberculosis Report 2022Geneva: World Health Organization. 2022. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. www.who.int › global-tuberculosis-report-2022: World Health Organization; 2022.

- 2.Kerantzas CA, Jacobs WRJ. Origins of Combination Therapy for Tuberculosis: Lessons for Future Antimicrobial Development and Application. mBio 2017; 14;8: e01586-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Zwick ED, Pepperell CS. Tuberculosis sanatorium treatment at the advent of the chemotherapy era. BMC Infect Dis 2020; 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Palomino JC, Martin A. Drug resistant mechanisms in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antibiot Basel 2014; 2;3: 317 – 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Seung KJ, Keshavjee S, Rich ML. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2015;27:5: a017863. 10.1101/cshperspect.a017863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fonseca JD, Knight GM, McHugh TD. The complex evolution of antibiotic resistant in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int J Infect Dis. 2015;32:94–100. 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh R, Dwivedi SP, Gaharwar US, et al. Recent updates on drug resistant in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Appl Microbiol. 2019;128:1547–67. 10.1111/jam.14478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allué-Guardia A, García JI, Torrelles J. Evolution of drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains and their adaptation to the human lung environment. Front Microbiol 2021;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.WHO. Global tuberculosis report 2023. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2023. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. 2023.

- 10.Häcker B, Schönfeld N, Krieger D, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of delamanid-containing regimens in MDR- and XDR-TB patients in a specialized tuberculosis treatment center in Berlin, Germany. Eur Respir J. 2020;56:2000009. 10.1183/13993003.00009-2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams AO, Makinde OA, Ojo M. Community-based management versus traditional hospitalization in treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob health res policy 2016; 1,10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Jeon DS, Shin DO, Park SK, et al. Treatment outcome and mortality among patients with Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Tuberculosis hospitals of the Public Sector. J Korean Med Sci. 2011;26:33–41. 10.3346/jkms.2011.26.1.33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leung ECC, Leung CC, Kam KM, et al. Transmission of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in a metropolitan city. Eur Respir J. 2013;41:901–8. 10.1183/09031936.00071212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banerjee R, Starke JR. What tuberculosis can teach us about combating multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacilli. J Clin Tuberculosis Other Mycobact Dis. 2016;3:28–34. 10.1016/j.jctube.2016.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Westhuizen H-M, Nathavitharana RR, Pillay C et al. The high-quality health system ‘revolution’: reimagining tuberculosis infection prevention and control. J Clin Tuberculosis Other Mycobact Dis 2019; 17100118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.NTLP. National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Programme (NTLP). Report: Ministry of Health, United Republic of Tanzania; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singhal P, Dixit P, Singh P, et al. A study on pre-XDR & XDR Tuberculosis & their prevalent genotypes in clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in North India. Indian J Med Res. 2016;143:341–7. 10.4103/0971-5916.182625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang KC, Yew WW. Management of difficult multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis: Update 2012. Respirology 2012; 2013: 8–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Drobniewski F, Nikolayevskyy V, Maxeiner H, et al. Rapid diagnostics of tuberculosis and drug resistance in the industrialized world: clinical and public health benefits and barriers to implementation. BMC Med. 2013;11:190. 10.1186/1741-7015-11-190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dlamini MT, Lessells R, Iketleng T, de Oliveira T. Whole genome sequencing for drug-resistant tuberculosis management in South Africa: what gaps would this address and what are the challenges to implementation? J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2019;16:100115. 10.1016/j.jctube.2019.100115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Witney AA, Gould KA, Arnold A, et al. Clinical application of whole-genome sequencing to inform treatment for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis cases. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:1473–83. 10.1128/JCM.02993-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vogel M, Utpatel C, Corbett C, et al. Implementation of whole-genome sequencing for tuberculosis diagnostics in a low-middle income, high MDR-TB burden country. Sci Rep. 2021;11:15333. 10.1038/s41598-021-94297-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gordon KA, Maraisc B, Walkere TM, Sintchenko V. Clinical and public health utility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis whole-genome sequencing. Int J Infect Dis 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Dookie N, Khan A, Padayatchi N, Naidoo K. Application of Next Generation sequencing for diagnosis and clinical management of drug-resistant tuberculosis: updates on recent developments in the field. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:775030. 10.3389/fmicb.2022.775030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Araujo L, Cabibbe AM, Mhuulu L, et al. Implementation of targeted next-generation sequencing for the diagnosis of drug-resistant tuberculosis in low-resource settings: a programmatic model, challenges, and initial outcomes. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1204064. 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1204064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharma A, Agarwal A, Katoch CDS, et al. Evaluation of a novel sputum processing ReaSLR methodology for improving sensitivity of smear microscopy in clinical samples. Med J Armed Forces India. 2022;78:227–82. 10.1016/j.mjafi.2020.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.WHO. Technical Report on critical concentrations for drug susceptibility testing of medicines used to treat drug-resistant tuberculosis. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2018 (WHO/CDS/TB/2018.5). Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 30 IGO 2018.

- 28.Kent L, McHugh TD, Billington O, et al. Demonstration of homology between IS6110 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and DNAs of other Mycobacterium spp? J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2290–3. 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2290-2293.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baker DJ, Aydin A, Le-Viet T et al. CoronaHiT: High-thoroughput sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 genomes. Genome Med 2021; 13: 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Li H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv preprint arXiv:13033997 2013.

- 31.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, et al. The sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–9. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cingolani P, Platts A, Wang le L, et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly (Austin). 2012;6:80–92. 10.4161/fly.19695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wood DE, Salzberg SL. Kraken: ultrafast metagenomic sequence classification using exact alignments. Genome Biol. 2014;15:R46. 10.1186/gb-2014-15-3-r46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Catalogue of mutations in. Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and their association with drug resistance. second ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phelan JE, O’Sullivan DM, Machado D, et al. Integrating informatics tools and portable sequencing technology for rapid detection of resistance to anti-tuberculous drugs. Genome Med. 2019;11:41. 10.1186/s13073-019-0650-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Witney AA, Bateson AL, Jindani A, et al. Use of whole-genome sequencing to distinguish relapse from reinfection in a completed tuberculosis clinical trial. BMC Med. 2017;15:71. 10.1186/s12916-017-0834-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu Q, Wang D, Martinez L, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing genotype strains and unfavourable treatment outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:180–8. 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mfinanga SGM, Warren RM, Kazwala R et al. Genetic profile of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and treatment outcomes in human pulmonary tuberculosis in Tanzania. Tanzan J Health Res, 2016; 16. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Katale BZ, Mbelele PM, Lema NA et al. Whole genome sequencing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates and clinical outcomes of patients treated for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Tanzania. BMC Genomics 2020; 2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Snobre J, Meehan CJ, Mulders W et al. Frameshift Mutations in Rv0678 Preserve Bedaquiline Susceptibility in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis by Maintaining Protein Integrity. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4769101 or 10.2139/ssrn4769101

- 41.Nimmo C, Bionghi N, Cummings MJ et al. Opportunities and limitations of genomics for diagnosing bedaquiline-resistant tuberculosis: an individual isolate meta-analysis. Lancet Microbe 2024; 9: S2666-5247(23)00317-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Islam MM, Alam MS, Liu Z et al. Molecular mechanisms of resistance and treatment efficacy of clofazimine and bedaquiline against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Front Med (Lausanne) 2024; 10;10:1304857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Sonnenkalb L, Carter JJ, Spitaleri A, et al. Comprehensive resistant prediction for tuberculosis: an International Consortium. Bedaquiline and clofazimine resistant in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: an in vitro and in-silico data analysis. Lancet Microbe. 2023;4:e358–68. 10.1016/S2666-5247(23)00002-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Degiacomi G, Sammartino JC, Sinigiani V, et al. In vitro study of Bedaquiline Resistant in Mycobacterium tuberculosis Multi-drug Resistant Clinical isolates. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:559469. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.559469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu J, Wang B, Hu M et al. Primary Clofazimine and Bedaquiline Resistance among Isolates from Patients with Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017; 24;61: e00239-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Timm J, Bateson A, Solanki P, et al. Baseline and acquired resistance to bedaquiline, linezolid and pretomanid, and impact on treatment outcomes in four tuberculosis clinical trials containing pretomanid. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2023;3:e0002283. 10.1371/journal.pgph.0002283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mallick JS, Nair P, Abbew ET et al. Acquired bedaquiline resistant during the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis: a systematic review. JAC Antimicrob Resist 2022; 29;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Nimmo C, Doyle R, Burgess C, et al. Rapid identification of a mycobacterium tuberculosis full genetic drug resistant profile through whole-genome sequencing directly from sputum. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;62:44–6. 10.1016/j.ijid.2017.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.