Abstract

Perioperative neurocognitive disorders (PND) refer to cognitive deterioration that occurs after surgery or anesthesia. Prolonged isoflurane exposure has potential neurotoxicity and induces PND, but the mechanism is unclear. The glymphatic system clears harmful metabolic waste from the brain. This study sought to unveil the functions of glymphatic system in PND and explore the underlying molecular mechanisms. The PND mice model was established by long term isoflurane anesthesia. The glymphatic function was assessed by multiple in vitro and in vivo methods. An adeno-associated virus was used to overexpress AQP4 and TGN-020 was used to inhibit its function. This research revealed that the glymphatic system was impaired in PND mice and the blunted glymphatic transport was closely associated with the accumulation of inflammatory proteins in the hippocampus. Increasing AQP4 polarization could enhance glymphatic transport and suppresses neuroinflammation, thereby improve cognitive function in the PND model mice. However, a marked impaired glymphatic inflammatory proteins clearance and the more severe cognitive dysfunction were observed when decreasing AQP4 polarization. Therefore, long-term isoflurane anesthesia causes blunted glymphatic system by inducing AQP4 depolarization, enhanced the AQP4 polarization can alleviate the glymphatic system malfunction and reduce the neuroinflammatory response, which may be a potential treatment strategy for PND.

Keywords: Perioperative neurocognitive disorder, glymphatic system, aquaporin-4, neuroinflammation, isoflurane

Introduction

General anesthesia is believed to cause a temporary and fully reversible loss of consciousness innocuous to the central nervous system (CNS). Evidence of consequential neurological problems would challenge this belief, thereby requiring a rethinking of the mechanism of anesthetic action or the CNS response to surgery.1,2 Cognitive decline after anesthesia or surgery is now well recognized and was named perioperative neurocognitive disorders (PND). 2 A variety of interventions have been developed for neurodegeneration, including those targeting amyloid deposition, neuroinflammation, and oxidative stress, all well-documented pathologies associated with PND.3,4 Additional risk factors, such as cardiovascular status, insulin resistance, and obesity may also influence cognition.4,5 Given its complex pathophysiology and heterogeneous etiology, an integrated management strategy for PND is desired. A tractable entry point for such strategies is the clearance of abnormal toxic proteins and metabolic waste.

The glymphatic system is a waste disposal system in the brain that uses peri-arterial space for the inflow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and peri-venous space for efflux of CSF from brain parenchyma, this brain-wide fluid transport pathway facilitates the exchange of CSF and interstitial fluid (ISF) and clears waste from the metabolically active brain.6,7 As such, the glymphatic system plays a key role in regulating directional CSF/ISF movement, waste clearance, and potentially, brain immunity. Previous studies have confirmed that prolonged failure of the glymphatic pathway for perivascular drainage contributes greatly to neurological diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), traumatic brain injury.8,9 These observations inspired us to investigate the potential causal link between glymphatic clearance and PND.

Aquaporin-4 (AQP4) polarization to perivascular astrocytic endfeet is critical for efficient glymphatic transport.10,11 Mouse lacking AQP4 exhibit about 70% reduction in CSF influx and 55% reduction in parenchymal solute clearance. 12 Pharmacological inhibition of AQP4 polarity resulted in about 85% reduction in CSF-ISF exchange. 11 Inefficient glymphatic transport in neurodegenerative disorders has been attributed to AQP4 depolarization.13,14 Yet, there is little direct evidence that AQP4 mediated glymphatic function impairment relates to the pathophysiology of PND.

Here, we used ex vivo fluorescence imaging and dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DCE-MRI) to demonstrate the glymphatic system was impaired in PND mice, which correlated with the abnormal localization and expression of AQP4, alluding to the critical role of this clearance system in the deposition of inflammatory proteins in the brain. Subsequently, we demonstrated the critical role of AQP4-mediated glymphatic clearance in PND by pharmacologically inhibiting AQP4 function and overexpressing AQP4 in astrocytes via recombinant adeno-associated virus.

Material and methods

Animals

Animal use and experimental protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital of Nanjing University Medical School (2021AE01058), and all of the experimental procedures were in accordance with guidelines set by the Institutes for the Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines (i.e., ARRIVE guidelines 2.0). 15 All male C57BL/6 mice were 4 months old and were maintained in standard housing conditions with food and water available ad libitum, on a 12-h light/dark cycle (8 am–8 pm). The animal facility’s temperature ranged from 20 to 23°C, and the humidity ranged from 40 to 60%.

Drugs and reagents

Pharmacologic inhibitor TGN-020 (HY-W008574, MedChemExpress, USA) was used to inhibit AQP4. 10 TGN-020 can be regarded as an isoform-specific inhibitor of AQP4 (at least among the aquaporins mainly expressed in mammalian plasma membranes). 16 To improve solubility, TGN-020 was dissolved in water for injection with 20% sulfobutyl ether-β-cyclodextrin (YITA Biotech, China). For AQP4 inhibition experiments, after establishing the PND model, the mice were treated intraperitoneally with either TGN-020 (250 mg/kg) or vehicle (20% sulfobutyl ether-β-cyclodextrin). Adeno-associated virus encoding AQP4 driven by the GFAP promoter (AAV-AQP4, Hanheng Biotech, China) was used to overexpress AQP4 in astrocytes in vivo.

Establishment of the PND mouse model

Animals were anesthetized using an inhalant gas mixture composed of isoflurane and air according to our previous study. 17 Mice were placed in a chamber with 4.2% isoflurane (license No. H20020267, Lunan Better Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., China) for induction and 1.5% isoflurane in 30% oxygen at a flow rate of 2–3 L/min for maintenance for 6 hours (from 9:00 pm to 3:00 am). During isoflurane exposure, an anesthesia monitor (Dragerwerk AG & Co. KGaA, Germany) was used to continuously monitor the concentration of isoflurane in the chamber, and respiration was observed to prevent respiratory depression. Mice were placed on a heating pad support to keep their body temperature within 36.5 ± 0.5°C and monitored with a rectal temperature probe. The same procedure was performed for the control animals but without isoflurane and mice were allowed to act freely. Mice were placed in a prone position in both awake and anesthesia conditions.

Behavioral tests

The mice underwent fear condition test (FCT) and Y maze test on days 3 and 7 after long-term isoflurane exposure to evaluate cognition in the mice as described previously. 17 FCT consists of conditional fear training, contextual fear condition test (CFCT, a hippocampal-dependent test), and tone fear condition test (TFCT, a hippocampal- and amygdala-dependent test).18,19 CFCT and TFCT were performed 24 h after training. Freezing was defined as a lack of movement besides respiration. Y maze was used to study spontaneous alternation as a measure of working memory. Each mouse was placed in the center of the Y maze and explored the arena for 8 min. The sequence and number of all arm entries were recorded for each animal throughout the period. The alternation rate was defined as entries into all three arms consecutively using formula (1):

| (1) |

Researchers carrying out follow-up measurements will be blinded to group assignment of mice and behavioral tests.

Western blot

The hippocampus was prepared as described previously. 17 Equal amounts of protein were loaded onto 10% SDS polyacrylamide gels and transferred to PVDF membranes (0.45 μm, Merck Millipore) before overnight incubation with the primary antibodies. Membranes were washed and incubated in the appropriate secondary antibodies for 2 h and visualized by ECL plus detection system. β-actin was used as the internal reference protein for normalization. The primary and secondary antibodies used are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Immunofluorescence staining

Coronal brain tissue sections were prepared as described previously, 17 and were incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4°C and then with corresponding fluorescent secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1.5 h. Slices were mounted with antifade mounting medium with DAPI (Beyotime Biotechnology, China). Multichannel fluorescent images were acquired using the Thunder Imaging System (Leica, Germany). Image J software was used to measure the mean fluorescence intensity. The primary and secondary antibodies used are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

AQP4 polarization analysis

The polarization of AQP4 in the hippocampus was quantified. Nine blood vessels (as identified by vascular-shaped AQP4 localization, with a length of 20–55 µm and a width of 5–8 µm) were selected randomly from three confocal images of each mouse and marked cross-sectionally using the line plot tool in ImageJ to measure immunofluorescence intensity. The measurement range was 30 µm outwards from the center of the vessel. Baseline fluorescence intensity (BFI) and peak fluorescence intensity (PFI) were calculated with reference to literature. 20 AQP4 polarization index was calculated with formula (2):

| (2) |

All values were normalized to the highest signal for ease of visualization.

Intracisternal CSF tracer infusion

Mice were anesthetized with a combination of ketamine (0.10 mg/g, i.p.) and xylazine (0.02 mg/g, i.p.), which has been shown not to affect tracer influx. 21 Subsequently, mice were placed prone, and their cisterna magna were surgically exposed under a stereomicroscope. 22 All contrast agents were dissolved in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (Yuanye Bio-Technology, China). 10 μl of 1% Evan’s blue (960 Da, GLPBIO, Montclair, USA) or 0.5% Texas Red-dextran 3(TR-d3, 3000 Da, Invitrogen, USA) or 21 mM Gadolinium-DTPA (Gd-DTPA, 938 Da, SunLipo NanoTech, China) was injected into the subarachnoid space at a rate of 1 μl/min using Hamilton microinjector with a 33 G needle. After injecting, the microinjector was left in place for another 10 minutes to prevent reflux. Afterward, the needle was removed and the pinhole was sealed with VetBond Tissue Adhesive (3 M, Maplewood, MN). The incision was supplied with 2.5% lidocaine and 2.5% prilocaine to alleviate postoperative pain. During the intra-cisterna magna injection and the next waiting time, blood pressure and heart rate in mice were monitored with the indirect tail-cuff system (Softron, China).

Ex vivo near-infrared fluorescence imaging

30 minutes after the completion of EB injection, mice brains and lymph nodes were removed after perfusion with PBS to perform ex vivo near-infrared fluorescence (NIRF) imaging. Each brain was placed in a photon imager (Biospace, France) and images were acquired with excitation filter set at 605 nm and emission filter set at 700 nm. The region of interest (ROI) used for quantitative fluorometry encompasses the whole forebrain for the dorsal and ventral part (brainstem not included).

Stereotactic injection (intrahippocampal injection)

Mice were anesthetized with a combination of ketamine (0.10 mg/g, i.p.) and xylazine (0.02 mg/g, i.p.), and fixed on the brain stereotactic apparatus (Ruiwode, China). The scalp of each mouse was then shaved and an incision was made through the midline to expose the skull. A craniotomy was drilled (bregma −2.5 mm, lateral 2 mm from midline, 2 mm ventral to the dura) into the skull of each mouse. A Hamilton syringe was used to inject 2 µL of 1% EB per hippocampal side at a rate of 0.2 µL/min. The bone hole was sealed with bone wax, and the wound was sutured. Subsequently, the mice were placed on a 37°C isothermal pad and continuously observed post-surgery until recovery.

Intracerebroventricular injection of AAV

Mice were also anesthetized with a combination of ketamine (0.10 mg/g, i.p.) and xylazine (0.02 mg/g, i.p.). AQP4 AAV (1.5 × 1012 vg/mL) or AAV control virus (2 µL) was slowly injected into each cerebral lateral ventricle. The lateral ventricle was located by stereotactic coordinates: 0.5 mm posterior from bregma, 1.0 mm lateral, and 2.0 mm ventral. Subsequently, the burr hole was sealed with bone wax and the wound was sutured. The incision was also supplied with 2.5% lidocaine and 2.5% prilocaine to alleviate postoperative pain. Experiments were performed three weeks after the virus injection.

EB extraction and colorimetric assay

24 hours after EB cisterna magna injection, mice were transcardially perfused with PBS under ketamine (0.10 mg/g, i.p.) and xylazine (0.02 mg/g, i.p.) anaesthesia. Brains were removed, brainstem and cerebellum were discarded, and the remaining tissue was minced with scissors after being weighed in an EP tube. Then formamide (1 mL/100 mg of brain tissue) was added to extract EB from the brain pieces at 37°C for 72 h. After centrifugation, the supernatant in each tube was carefully collected and the absorbance at 630 nm was measured with a Tecan Spark microplate spectrophotometer (Tecan, Switzerland). The concentration of EB was calculated following the standard curve of EB in formamide. The above procedure is schematically presented in Figure 1(r). For intrahippocampal injection, at 24 hours after the EB injection, the mice were sacrificed by decapitation and the hippocampal tissue was rapidly dissected. Residual EB levels in hippocampus were determined as described above.

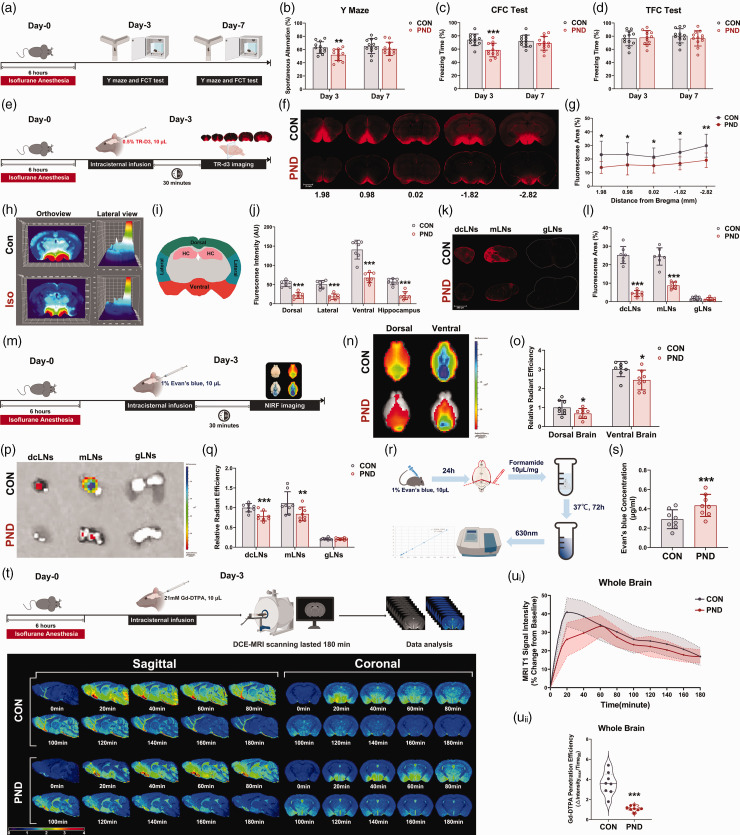

Figure 1.

Adult mice show cognitive dysfunction and glymphatic system impaired following exposure to long-term isoflurane. (a) The PND mouse model was constructed by exposure to isoflurane for 6 hours. Fear conditioning test and Y maze test were performed on days 3 and 7 after the isoflurane exposure. Working memory (b) and contextual fear memory (c) are impaired at day 3 in mice exposed to long-term Isoflurane, however, a tone fear memory was not influenced (d). (e) Schematic of TR-d3 imaging. Mice were intracisternal injection of TR-d3, and the brains and lymph nodes were harvested 30 min later, freshly sliced, and imaged. (f) Representative images showing TR-d3 influx in sagittal brain slices on the 3rd day after modeling. Numbers indicate the anteroposterior distance from bregma in mm. (g) Quantification of TR-D3 positive area per slice (n = 7). (h) Histograph functionality was across stitched whole-brain confocal images (bregma −1.82 mm) of TR-d3 injected mouse brains on the 3rd day after modeling. Color peaks within the histographs represent the positions of TR-d3 particles within mouse brains, the higher the TR-d3 intensity is on this histograph, the more red the color; similarly, the lower the TR-d3 intensity, the bluer the color of the curves. (i) Diagram showing the subregional analysis of brain slice (bregma −1.82 mm). (j) Quantification of the TR-d3 fluorescence intensity of the dorsal, lateral, ventral, and hippocampus. (k) Representative images of dcLNs, mLNs, and gLNs at 30 min after intracisternal TR-d3 infusion on the 3rd day after modeling. gLNs were used as controls to correct for background fluorescence. (l) Percent area covered by TR-d3 in Continued.dcLNs, mLNs, and gLNs. (m) EB is infused in the cerebrospinal fluid via the cisterna magna. At 30 min post-infusion, EB is quantified in brains, dcLNs, mLNs and gLNs. (n) Representative brain-wide NIRF images of EB 30 min after intracisternal infusion on the dorsal and ventral sides. (o) Quantification of EB radiant efficiency in the dorsal and ventral sides. (p) Representative images of the ex vivo lymph nodes at the end of the circulation time (30 min for CM injection). gLNs were used as controls to correct for background fluorescence. (q) Quantification of the radiant efficiency in lymph nodes (r) Intracerebral infusion of EB and quantification of parenchyma EB clearance. (s) Spectrophotometric quantification of the EB content after extraction by formamide. (t) Upper panel: schematic of intracisternal injection of Gd-DTPA and measurement by DCE-MRI; Lower panel: representative psuedocolour images (about 0 mm lateral to bregma for sagittal image and about 1.82 mm posterior to bregma for coronal image) over time after intracisternal injection of Gd-DTPA. Time of acquisition from the end of the injection is shown in minutes. Time 0 on all graphs are baseline images taken before Gd-DTPA infusion. (u) Time-signal curves of Gd-DTPA induced MRI T1 signal intensity changes in the whole brain (ui) and the quantification of Gd-DTPA penetration efficiency (uii). Dashed-dotted line in ui is mean values with shading showing 95% confidence intervals, the solid lines are fitting curves of mean. In uii, the solid line represents the median, and dashed lines represent lower and upper quartiles. n = 12 for the behavioral test, n = 7–8 per group for other experiments; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared to the Con group.

Ex vivo TR-d3 imaging

To evaluate the movement of intrathecal tracers into the mice brain with higher resolution, we conducted ex vivo fluorescence imaging of TR-d3 in brain slices. Mice were sacrificed 30 min after completing intracisternal microinjection of TR-d3. Brains were then dissected and postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h before being sliced into 100 μm coronal sections using a vibratome and with an anti-fluorescence quencher (Leagene Biotechnology, China). Images were acquired with a Thunder Imaging System (Leica, Germany) and analyzed as described previously, 23 the percentage area of TR-d3 positive signals was calculated by dividing the area of positive signals by the total area in the ROI. The mean tracer coverage in three slices was averaged for each animal to generate a single biological measure. The same method was used to determine the percentage area of TR-d3 in the lymph node.

Brain water content measurements

Anesthetized mice were decapitated and their brains were dissected without perfusion. Brain tissues were weighed to measure wet weights and then dried at 65°C until they reached a constant weight (about 48 hours). The resulting dry weight was recorded. Formula (3) was used to calculate brain water content:

| (3) |

DCE-MRI

The detailed methods about DCE-MRI are described in the supplementary methods.

Arterial blood gas analysis

Following DCE-MRI examination, 0.2 mL abdominal aorta blood was immediately collected in a heparinized syringe. The i-STAT portable blood-gas analyzer (Abbott Park, IL, USA) and the i-STAT CG8+ cartridge (Abbott Park, IL, USA) were used to measure arterial blood gas.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 21.0 (IBM, Armonk, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Data are presented as the means ± standard deviation (SD) (if not specified). The normality of data was verified with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Levene’s test was applied to test the homogeneity of variance. Two-tailed independent samples t-test was employed to compare data between two groups. Multivariate data were analyzed with one-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni test when variances were homogeneous or by the Dunnett T3 test when variances were not homogeneous. Nonnormally distributed data were analysed with the Mann–Whitney U test. Correlations were analysed with Pearson correlation analysis. If not otherwise indicated, P < 0.05 was considered as statistical significance.

Results

Adult mice exhibited cognitive dysfunction and glymphatic system impairment following long-term isoflurane exposure

To verify the establishment of the PND model, Y maze and fear conditioning tests were used to assess the cognitive function of mice in different groups at 3 days and 7 days after modeling (Figure 1(a)). Y maze spatial memory and contextual fear conditioning (CFC) memory were dramatically impaired at 3 days after long-term isoflurane anesthesia. There was no statistically significant difference in Y maze spatial memory and CFC memory between the CON and PND group at 7 days after modeling (Figure 1(b) and (c)). No significant differences between the groups were found in tone fear conditioning (TFC) test (Figure 1(d)). Movement velocity and the number of arm visits in Y maze, and freezing levels during the training phase of FC test did not differ between groups (Supplementary Fig. S1A-C), indicating that Y maze and FC test performance were not influenced by differences in motor ability or baseline cognition deficits. This implies that long-term isoflurane anesthesia impairs hippocampus-dependent memory, in accordance with previous reports.17,24

To assess glymphatic function in PND mice at day 3 post-modeling, CSF tracer (TR-d3) was slowly infused into the cisterna magna (Figure 1(e)). Thirty minutes after intracisternal infusion, the parenchymal distribution of TR-d3 was reduced in PND mice than in CON mice (Figure 1(f) and (g)). Notably, TR-d3 intensity showed a decreasing trend from ventral brain to dorsal brain (Figure 1(h)), and subregional quantification showed that TR-d3 penetrated less into the dorsal, lateral, ventral, and hippocampus of PND mice than CON mice (Figure 1(i) and (j)). As shown by high magnification micrographs of brain sections (Supplementary Fig. S1D), there was strong fluorescent intensity within the perivascular space and adjacent brain parenchyma, which indicating perivascular influx in the glymphatic system. Substances transported from brain parenchyma to CSF by the glymphatic system are cleared out of the brain via dural lymphatic vessels and transported downstream into the deep cervical lymph nodes (dcLNs) and mandibular lymph nodes (mLNs).8,25,26 TR-d3 drainage from CSF to dcLNs and mLNs was impaired in PND mice (Figure 1(k) and (l)). To confirm these results using macroscopic imaging methodology, we performed NIRF imaging of the ex vivo brain 30 min after intracisternal injection of EB (Figure 1(m)). NIRF imaging can detect fluorescence arising from several millimeters below the brain surface, both the superficial tracer accumulation and intraparenchymal tracer accumulation were detected. 27 The distribution of EB in the dorsal and ventral brain was markedly reduced in PND mice (Figure 1(n) and (o)). Obviously, EB was distributed in the ventral brain and surrounded by the Willis polygon, an arterial network at the base of the skull (Figure 1(n) and (o)). We observed that EB entry into dcLNs and mLNs was also impaired in PND mice (Figure 1(p) and (q)), this was consistent with previous observations in TR-d3 lymph node sections (Figure 1(k) and (l)). To assess whether or not such a reduction in glymphatic influx also translated to a reduction in clearance of tracer from the brain parenchyma, we measured clearance of EB from the brain at 24 hours post-intracisternal infusion (Figure 1(r)). We observed a higher EB concentration in brain parenchyma of PND mice suggesting compromised glymphatic clearance (Figure 1(s)). On the other hand, we injected EB directly into the hippocampus and the residual EB level was assessed 24 hours after injection. We found that EB levels were significantly higher in the hippocampus of PND mice compared to CON mice (Supplementary Fig. S1E-F), which indicated that the clearance of EB from the brain parenchyma was compromised in PND mice. There were no significant differences in heart rate and mean arterial pressure between the groups during the CSF tracer intracisternal infusion at day 3 post-modeling (Supplementary Fig. S2A-D), thus supporting the hypothesis that CSF tracer transport was reduced in PND mice due to a decline in glymphatic function.

Ex vivo imaging modalities were applied universally but did not provide any dynamic CSF flow information. Additionally, the structure of the glymphatic system is partially altered after death because the perivascular spaces collapse once blood perfusion ceases.28,29 Therefore, we use DCE-MRI to dynamically visualize brain-wide glymphatic pathway in living mice brain with a 3D manner (Figure 1(t)). We observed the brain parenchyma entry path for Gd-DTPA was via the pontine cistern, where CSF moves along the perivascular space surrounding the basilar artery to the circle of Willis, and then ascends along the perivascular spaces of the anterior, middle, and posterior cerebral arteries (in the sagittal images of Figure 1(t) mainly manifested anterior cerebral artery), which confirms the distinct pattern of glymphatic flow previously reported in rodents.10,30 Quantification of Gd-DTPA signal in the whole brain revealed blunted glymphatic flow in PND mice, as indicated by a significant reduction of Gd-DTPA penetration efficiency (Figure 1(u)). No significant differences existed between CON and PND groups in arterial blood gases during MRI scans (Supplementary table. 2).

At day 7 post-modeling, the impaired glymphatic transport had recovered in PND mice (Supplementary Fig. S1G–S, Supplementary Fig. 2 A–C, Supplementary Fig. S3E–H and Supplementary table 3), which echoes the behavioral results at day 7 (Figure 1(a) to (c)). Of note, the brain water content in both groups did not differ (Supplementary Fig. S2D)

Thus, several independent sets of analyses point to glymphatic system function and drainage of CSF to the lymph nodes are impaired in the PND mouse model constructed by long-term isoflurane exposure.

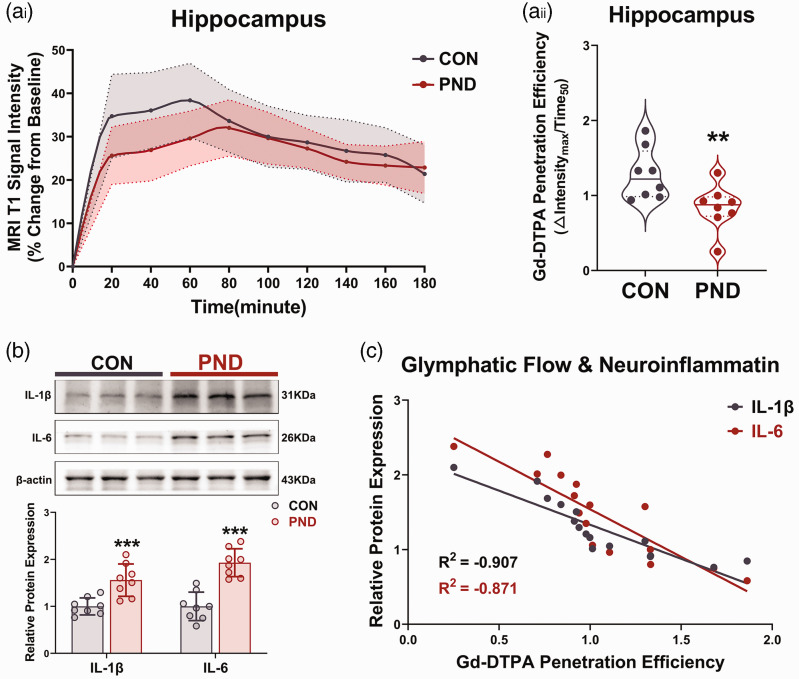

The blunted glymphatic flow and neuroinflammatory proteins accumulation in the hippocampus of PND mice

Neuroinflammation is a hallmark feature of PND pathology, and long-term isoflurane anesthesia can result in hippocampal inflammation.17,24 We hypothesized that this may be due to blunted glymphatic flow, which would impact inflammatory proteins clearance. Thus, we also analysed the Gd-DTPA penetration efficiency in the hippocampus at day 3 after modeling, and a notable impaired glymphatic flow was observed in the hippocampus of PND mice (Figure 2(a)). Meanwhile, inflammatory proteins (IL-1β and IL-6) revealed a significant increase in the hippocampus of PND mice, compared to the control group at day 3 after modeling (Figure 2(b)). Interestingly, there was a clear linear inverse association between Gd-DTPA penetration efficiency and inflammatory proteins (Figure 2(c)), even on the 7th day when there was no difference between the two indicators mentioned above (Supplementary Fig. S4A–C), suggesting that glymphatic system dysfunction might contribute to neuroinflammation during the PND pathological process.

Figure 2.

Impaired glymphatic transport may contribute to the accumulation of neuroinflammatory proteins in hippocampus. (a) Time-signal curves of Gd-DTPA induced MRI T1 signal intensity changes in hippocampus (ai) and the quantification of Gd-DTPA penetration efficiency (aii). The solid line in ai is mean values with shading showing 95% confidence intervals. In aii, the solid line represents the median, and the dashed lines represent lower and upper quartiles. (b) Representative immunoblots and quantification of inflammatory proteins in hippocampus at 3 days after modeling and (c) correlation between Gd-DTPA penetration efficiency and inflammatory proteins expression levels were obtained using Pearson correlation. n = 8 per group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared to the Con group.

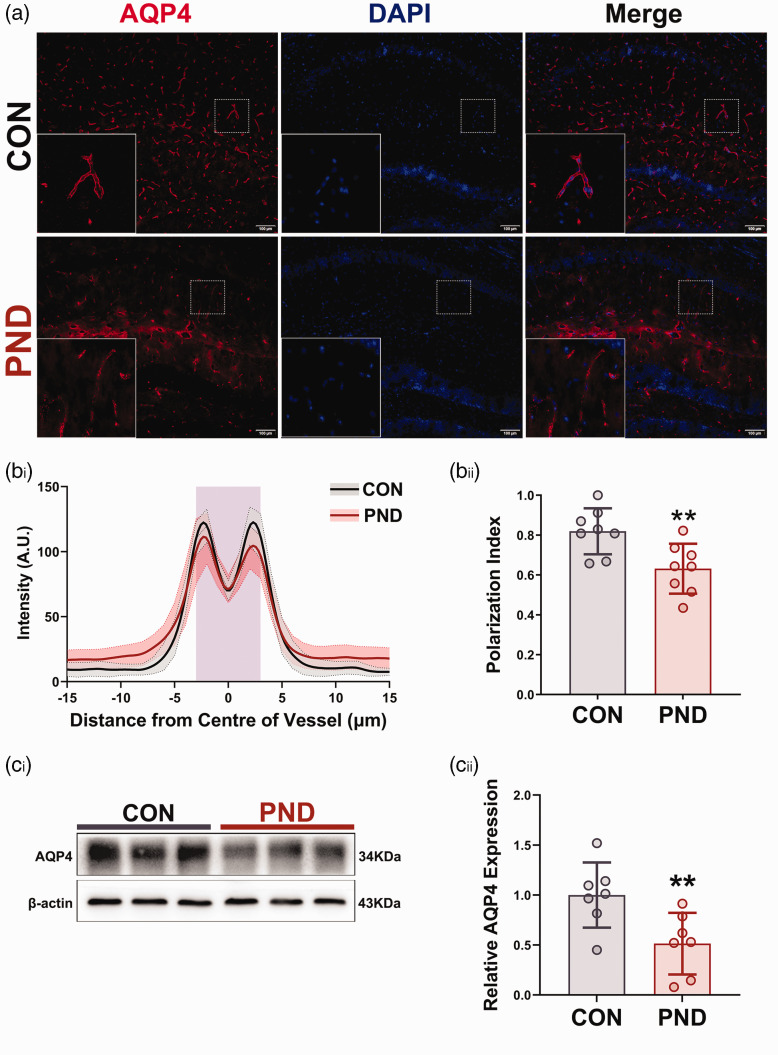

Reduced polarization of AQP4 in hippocampus of PND mice

AQP4 is primarily expressed in the astrocytic perivascular endfeet that line the brain vasculature, their normal expression and polarized localization are essential for optimal glymphatic function. 11 Subsequently, we asked if AQP4 exhibits low expression or depolarization in PND mice. Using immunohistochemistry on brain slices, we found AQP4 polarization was markedly decreased in the hippocampus of PND mice at 3 days post-modeling (Figure 3(a) and (b)). Using western blot to measure protein in the hippocampus extracts, we found AQP4 was downregulated in hippocampus of PND mice at 3 days post-modeling (Figure 3(c)). Consistent with functional changes in glymphatic system, AQP4 depolarization and low expression in the hippocampus returned to baseline at 7 days after modeling (Supplemental Fig. S4D-F). These data indicate the mislocalization and decreased expression of AQP4 adversely affect glymphatic transport and exacerbate neuroinflammation in PND mice.

Figure 3.

PND mice showed a clear AQP4 depolarization and low expression in hippocampus. (a) Representative fluorescent images of AQP4 immunostaining in hippocampus at 3 days after modeling. (bi) Average intensity of AQP4 staining centered on the vasculature in hippocampus of CON (gray, n = 8 mice, 64 vessels/mice) and PND (red, n = 8 mice, 64 vessels/mice), with mean and 95% confidence intervals indicated by the dashed-dotted line (mean) with shading (95% confidence intervals), the solid lines are fitting curves of mean. Purple area indicates the vessel. (bii) Quantification of AQP4 polarization in hippocampus. Representative immunoblots (ci) and quantification of AQP4 (cii) in hippocampus at 3 days after modeling. n = 8 per group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared to the Con group.

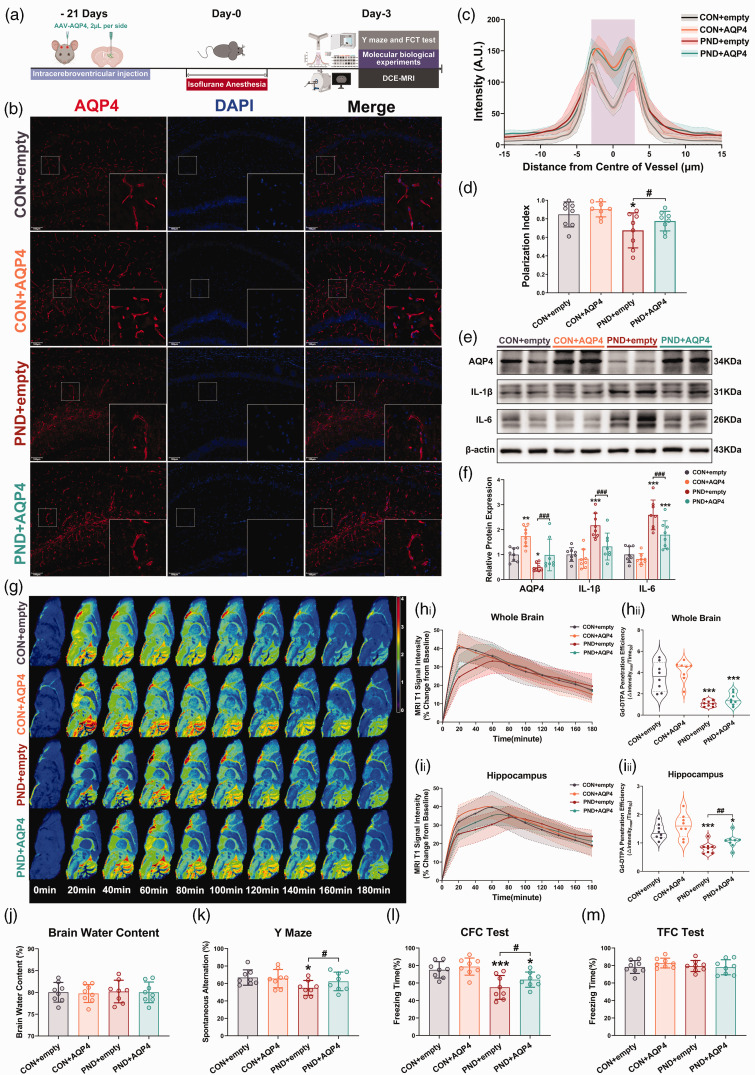

Effect of enhanced AQP4 polarization on glymphatic dysfunction and neuroinflammatory proteins accumulation in PND mice

To investigate whether AQP4 polarization and high expression could enhance glymphatic dysfunction, we overexpressed AQP4 in astrocytes in vivo using AAV-AQP4 (Figure 4(a)). Immunofluorescence and qRT-PCR showed that AAV-AQP4, which expressed EGFP and FLAG, was successfully transfected into hippocampal astrocytes (Supplemental Fig. S5). Increased AQP4 polarity and expression were detected in the hippocampus of PND mice following AAV-AQP4 treatment (Figure 4(b) to (f)). Interestingly, AAV-AQP4-treated PND mice showed significantly decreased the expression of IL-1β and IL-6 in the hippocampus compared with AAV-empty-treated PND mice (Figure 4(e) and (f)). AAV-AQP4 also suppressed isoflurane-induced hippocampal microglial activation (Supplemental Fig. S6A). This result concurred with the changes in glymphatic transport kinetics, significantly enhanced Gd-DTPA penetration efficiency in the hippocampus was observed in AAV-AQP4-treated PND mice compared with the AAV-empty-treated PND mice (Figure 4(g) and (i)). However, Gd-DTPA penetration efficiency differences were absent at the whole-brain level for the above two groups (Figure 4(h)), which may be attributed to AAV-AQP4 regional distribution in the hippocampus (Supplemental Fig. S5A). No significant differences existed among groups in arterial blood gases during MRI scans (Supplementary table. 4). AAV-AQP4 intervention did not alter brain water content, blood pressure, and heart rate (Figure 4(j) and Supplemental Fig. S6B). In parallel with increased glymphatic transport and inflammatory proteins levels, we found that the impaired Y maze spatial memory and CFC memory seen in PND mice can be ameliorated by treating with AAV-AQP4 (Figure 4(k) and (l)). Importantly, these differences in behavioral performance were not due to defects in locomotor activity or altered baseline cognition, as we observed that the movement velocity and the number of arm visits in Y maze, and freezing levels during the training phase of FC test were similar among groups (Supplemental Fig. S6C-E). No significant differences among the groups were found in CFC test (Figure 4(m)). Altogether, these data indicated that promoting AQP4 polarization expedited the recovery of glymphatic function, while rescuing PND mice from neuroinflammation and cognitive deficits.

Figure 4.

AQP4 overexpression and polarization ameliorate glymphatic neuroinflammatory proteins clearance and cognitive impairment in a mouse model of PND. (a) AAV-AQP intracerebroventricular injection and the subsequent experimental procedures followed timeline. (b) Representative immunofluorescence images of AQP4 in the hippocampus. (c) Average intensity of AQP4 centered on vasculature in hippocampus, mean and 95% confidence intervals is indicated by shading (95% confidence intervals) around Continued.dashed-dotted line (mean), the solid lines are fitting curves of mean, purple area indicates the vessel. (d) Quantification of AQP4 polarization in hippocampus. (e) Representative immunoblots for AQP4 and inflammatory proteins in hippocampus and their quantification (f). (g) Representative psuedocolour sagittal image (about 0 mm lateral to bregma) over time after intracisternal injection of Gd-DTPA. Time of acquisition from the end of the injection is shown in minutes. Time 0 on all graphs are baseline images taken before Gd-DTPA infusion. See Supplementary Figure. S5A for representative psuedocolour coronal images. (h) Time-signal curves of Gd-DTPA induced MRI T1 signal intensity changes in the whole brain(hi) and the quantification of Gd-DTPA penetration efficiency (hii). (i) Time-signal curves of Gd-DTPA induced MRI T1 signal intensity changes in hippocampus (ii) and the quantification of Gd-DTPA penetration efficiency (iii). (j) Brain water contents (%) were not affected by AAV-AQP4 treatment. Treated with AAV-AQP4, the working memory (k) and contextual fear memory and (l) were further aggravated in PND mice, however, the tone fear memory was not affected by AAV-AQP4 treatment(m). n = 8 per group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared to the CON + empty group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 compared to the PND + empty group.

Effect of pharmacological inhibition of AQP4 polarization on glymphatic dysfunction and neuroinflammatory proteins accumulation in PND mice

TGN-020 is reported to disrupt the polarization of astrocytic AQP4, thus inhibiting the normal function of AQP4. 31 Therefore, we next applied TGN-020 to suppress AQP4 polarization to explore whether AQP4 depolarization affected glymphatic function and contributed to PND (Figure 5(a)). We found that TGN-020 further aggravated AQP4 depolarization (Figure 5(b) to (d)) in the hippocampus of PND mice without affecting its expression (Figure 5(e) and (f)). No significant differences existed among the four groups in arterial blood gases during MRI scans (Supplementary table. 5).

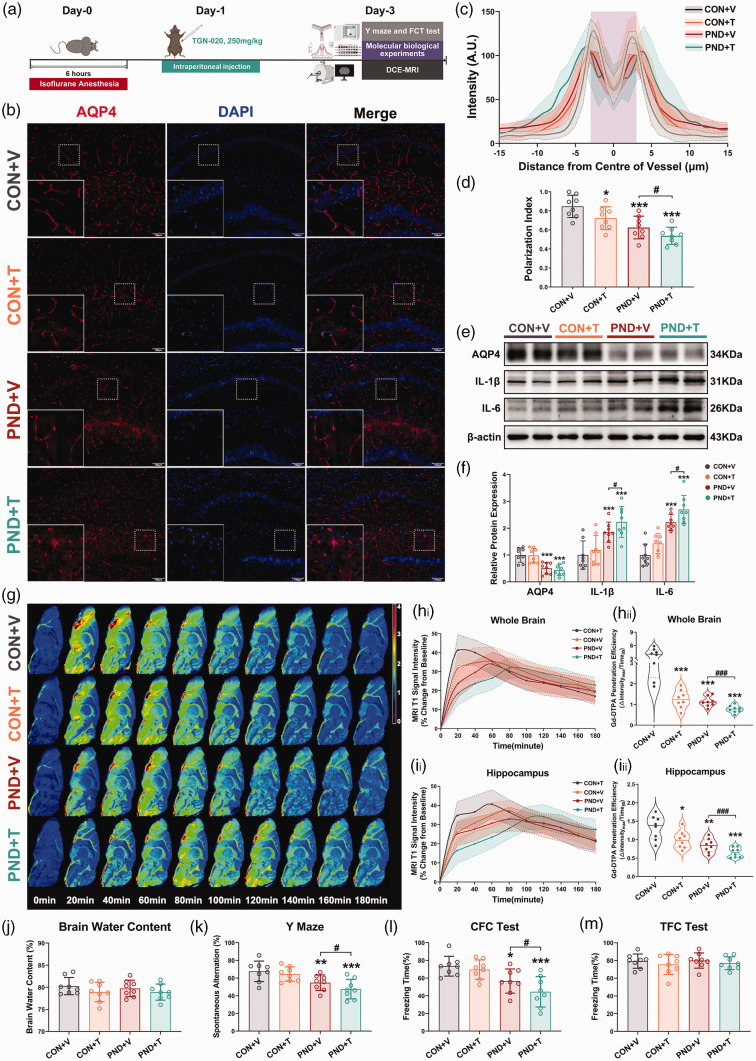

Figure 5.

Suppression of glymphatic functions by treatment with the AQP4 polarization inhibitor TGN-020 exacerbates neuroinflammation and cognitive deficits in PND mice. (a) Schematic of intraperitoneal injection of TGN-020 and the subsequent experimental procedures followed. (b) Representative immunofluorescence images of AQP4 in the hippocampus. (c) Average intensity of AQP4 centered on vasculature in hippocampus, mean and 95% confidence intervals is indicated by shading (95% confidence intervals) around the dashed-dotted line (mean), the solid lines are fitting curves of mean, purple area indicates the vessel. (d) Quantification of Continued.AQP4 polarization in hippocampus. (e) Representative immunoblots for AQP4 and inflammatory proteins in hippocampus and their quantification(f). (g) Representative psuedocolour sagittal image (about 0 mm lateral to bregma) over time after intracisternal injection of Gd-DTPA. Time of acquisition from the end of the injection is shown in minutes. Time 0 on all graphs are baseline images taken before Gd-DTPA infusion. See Supplementary Figure. S6A for representative psuedocolour coronal images. (h) Time-signal curves of Gd-DTPA induced MRI T1 signal intensity changes in the whole brain(hi) and the quantification of Gd-DTPA penetration efficiency(hii). (i) Time-signal curves of Gd-DTPA induced MRI T1 signal intensity changes in hippocampus(ii) and the quantification of Gd-DTPA penetration efficiency(iii). (j) Brain water contents (%) were not affected by TGN-020 treatment. Treated with TGN-020, the working memory (k) and contextual fear memory and (l) were further aggravated in PND mice, however, the tone fear memory was not affected by TGN-020 treatment(m). n = 8 per group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared to the CON + V group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 compared to the PND + V group.

DCE-MRI revealed a severely delayed CSF tracer influx in the whole brain and hippocampus of TGN-020 treated mice compared with vehicle treated mice (Figure 5(g) and (i)), undoubtedly, the sluggish glymphatic transport observed in the hippocampus translates to a higher expression of inflammatory proteins (Figure 5(e) and (f)) and more widespread microglial activation (Supplemental Fig. S7A). TGN-020 intervention did not alter brain water content, blood pressure, and heart rate (Figure 5(j) and Supplemental Fig. S7B). When behavioral tests were used to evaluate cognitive function at 3 days after PND modeling, after exclusion of locomotion and baseline cognition (Supplemental Fig. S7C-E), we found that TGN-020 worsened cognitive function in PND mice (Figure 5(k) and (l)). No significant differences among the groups were found in CFC test (Figure 5(m)). These results demonstrate that AQP4 depolarization, in addition to causing glymphatic system dysfunction and promoting neuroinflammation, exacerbates cognitive deficits in PND mice.

Discussion

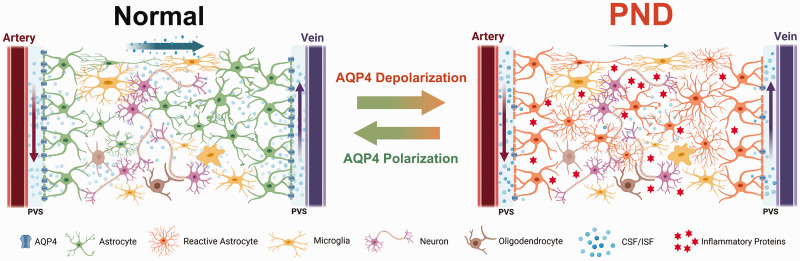

In this study, we showed that glymphatic efflux and influx were severely impaired in mice at 3 days after long-term isoflurane anesthesia. The transient deficit in glymphatic function paralleled the neuroinflammation and cognitive dysfunction. Subsequently, we found that AQP4 depolarization after long-term isoflurane anesthesia impaired the clearance of interstitial solutes along the paravascular glymphatic pathway, increased inflammatory protein levels, and in turn exacerbated neurocognitive deficits in mice (shown in schematic form in Figure 6). The rescue experiments showed that enhanced AQP4 polarization could attenuate cognitive impairment in PND mice by suppressing neuroinflammation via enhancing glymphatic system. Together, our data demonstrate that inhibiting AQP4 depolarization could ameliorate long-term isoflurane anesthesia induced cognitive impairment and lead to a novel therapeutic strategy for treating neuroinflammation associated disorders.

Figure 6.

Graphic scheme summarizing the findings of this study. Left: The glymphatic system is the functional analog of the glymphatic system in the brain. Within the glymphatic pathway, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) enters the brain via periarterial spaces, passes into the interstitium via perivascular astrocytic aquaporin-4, and then carries solutes to the perivenous space to exit the brain tissue. Right: Glymphatic function was impaired during the course of PND. There is less perivascular AQP4 in the brain of PND mice, and glymphatic influx is reduced. Dysfunction of glymphatic system can enhance inflammatory proteins deposition and exacerbate brain neuroinflammation, resulting in neurocognitive impairments. However, increasing AQP4 polarization can enhance the glymphatic clearance of inflammatory proteins, and improve cognitive function in PND mice.

The brain is one of the most energetically demanding organs in the body. However, the brain lacks traditional lymphatic capillaries to establish directional fluid movement and waste clearance. Instead, the brain uses a network termed the glymphatic system to support a constant influx of CSF that drives metabolic waste export. Deficiencies in glymphatic clearance of metabolic waste products contribute to neurodegenerative diseases, while enhancing glymphatic clearance can prevent or delay the progression of neurodegeneration. One general explanation for PND is that intracerebral accumulation of metabolic waste stems from insufficient clearance of interstitial proteins, which in turn induce neuroinflammation or toxicity, therefore, enhancing the glymphatic system will facilitate the removal of metabolic waste, thus representing an appealing therapeutic concept. Diminished glymphatic function may be a hallmark of a vulnerable brain, and interventions that target glymphatic function could prevent the development of PND. Future prospective validation clinical studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis. Remarkably, the DTI-ALPS (Diffusion Tensor Image Analysis Along the Perivascular Space) index is an uplifting noninvasive indicator for assessing glymphatic function in human subjects. 32

The glymphatic system has been visualized using various imaging approaches, including brain section microscopy, two-photon microscopy, transcranial mesoscopic imaging, and DCE-MRI; each of these methods has its unique characteristics. For example, although anatomic characterization can be well described, Ma et al. found that the distribution of CSF tracers in the brain displayed by fluorescence imaging after animal death was inconsistent with that in the living state. 29 The rapid entry of CSF tracers into the penetrating arteries of the brain during animal death, as well as damage to paravalvular channels during brain tissue fixation by cardiac perfusion, can significantly affect the distribution and localization of CSF tracers in the brain, 33 highlighting the need to study the glymphatic system at the in vivo level. In addition to its high spatial and temporal resolution for transport kinetics, DCE-MRI does not require tissue harvest, which avoids postmortem artifacts.29,33 Therefore, in our study, multiple and complementary approaches were used to evaluate changes in glymphatic system following intervention.

Glymphatic function appears to be, at least partially, mediated through arterial pulsations (potentially generated by cardiac pulsatility, respiration, and slow vasomotion) that create pressure differentials within the brain interstitial spaces and helps to drive CSF circulation out of and into perivascular channels of flow. 34 Body posture is also an important parameter can influence glymphatic system. 35 Thus, to study the effect of glymphatic system changes in PND, it was important to avoid this confounding influence. Blood pressure and heart rate were continuously monitored during intracisternal CSF tracer infusion until the animals were sacrificed, and blood gas analysis was done to evaluate oxygenation and metabolic state during DCE-MRI. All mice were kept in the prone position for cisterna magna injection and DCE-MRI. Furthermore, hemodynamic parameters, respiratory rate, oxygenation, and metabolic state were well controlled in different groups. Therefore, haemodynamics and body posture are unlikely to explain the observed differences in glymphatic transport. Notably, glymphatic system has been shown to affect AAV vector gene transfer in the brian, and in particular, decreased glymphatic influx in AQP4 knockout mice resulted in reduced viral transduction and transgene expression. 36 Therefore, AAV-AQP4 was administered before PND modeling to assure mice in different groups achieved comparable transfection levels.

A trifold dysfunction of the glymphatic system has been observed in our study: decreased brain surface coverage, slower diffusion in the brain parenchyma, and reduced tracer excretion into the cervical lymph node. Astrocytes are mainly layered around the blood vessels in the brain and create with their vascular endfeet the perivascular spaces, which are utilized as “highways” for rapid CSF transport into deeper brain regions. Therefore, CSF tracer entry into the ventral brain was higher than into the dorsal brain, this may be attributable to major cerebral arteries extending in the ventral to dorsal direction. 37 For example, we observed that Gd-DTPA enters the brain along the anterior cerebral artery (Figure 4(g)). In addition, the developmental profile of AQP4 expression also showed a ventral-to-dorsal gradient, 38 as does glymphatic tracer influx. Glymphatic system and the meningeal lymphatic vessels (mLVs) are part of the same pathway for effective removal of solutes from the brain. 38 Specifically, mLVs is a downstream draining route of the glymphatic system, and the ablation of mLVs leads to a reduced perivascular influx of CSF macromolecules into the brain parenchyma and concomitantly reduced clearance of macromolecules from the brain, ultimately resulting in cognitive impairment in mice. 39 Our study found that the CSF tracer flowing into lymph nodes of PND mice was reduced, whether this was due to the destruction of mLVs or a downstream effect of delayed glymphatic transport remains to be explored. Consistent with this idea, it has been shown that promoting meningeal lymphatic drainage by meningeal lymphangiogenesis can enhance inflammatory proteins clearance. 40

AQP4 is a key component of glymphatic clearance and predominantly expressed within perivascular astrocytic end-foot processes.11,41 AQP4 affects the glymphatic system in two ways. First, reduction of AQP4 expression, for example, loss of AQP4 exacerbates glymphatic dysfunction, increases amyloid-β accumulation, and exacerbates cognitive deficits in AD mice. 42 Second, AQP4 depolarization; AQP4 can only depolarize with constant expression. 20 Certainly, there is also the possibility that both these scenarios can occur simultaneously. 43 Our results showed that long-term isoflurane anesthesia results in both decreased AQP4 expression and increased AQP4 depolarization. We cannot exclude the possibility that other factors that could affect AQP4 gene expression under PND conditions exist, and this possibility requires further investigation. However, the appropriate localization of AQP4 appears to be more conducive to an efficient glymphatic system than changes in AQP4 expression.10,20,43 –46 Thus, we focused our study on AQP4 depolarization mechanism. We found that AQP4 overexpression by AAV promoted the restoration of AQP4 polarity and glymphatic function in PND mice, while inhibition of AQP4 polarization by TGN-020 worsened the existing neuroinflammation and cognitive dysfunction in PND mice, suggesting that long term isoflurane anesthesia induced glymphatic system dysfunction is associated with AQP4 depolarization. It should be noted that, in this study, we did not investigate changes in the glymphatic system under anesthesia maintenance, but rather the neurological problems following by anesthesia exposure. Isoflurane, one of the most widely used anesthetics in preclinical and clinical settings, has previously been shown to induce cognitive dysfunction and contribute to PND. 17 Xie Z et al. found isoflurane increases Aβ levels in mouse brain after anesthesia, 47 this could be related to the suppression of glymphatic transport, since mice demonstrated a low EEG delta power and high heart rate under isoflurane anesthesia. 48 Notably, glymphatic system changes in an anesthetized state remain controversial.27,48 This study focuses on the cognitive impairment after isoflurane exposure rather than the changes of glymphatic system during anesthesia maintenance. Our research implicates glymphatic system dysfunction as a key mechanism by which long-term isoflurane anesthesia contributes to cognitive impairment in mice. An interesting phenomenon is that neonatal exposure to isoflurane has more serious long-term outcomes,49,50 this might be due to the newborn brain having a nonoptimal glymphatic system, thus, may have impaired clean-up capacity.38,51

Interstitial solutes in the brain can be removed by various overlapping clearance systems, including glymphatic clearance, blood–brain barrier (BBB) transport, blood–cerebrospinal fluid barrier (BCSFB) transport, enzymatic degradation and cellular uptake, and meningeal lymphatic vessels. 52 Although the relative contributions of each of these systems to overall clearance are unknown, they act together to drive neurotoxicants from the brain, meaning that alterations in any given system can contribute to the altered pathophysiology in neurological diseases. BBB transport and glymphatic clearance have the same purpose in clearing interstitial solutes such as Aβ from the brain and in that sense likely serve complementary roles and seem to be partially overlapping mechanisms, 53 but its connection to glymphatic clearance remains to be clarified. It is widely believed that the influx of inflammatory cells and mediators into the CNS through compromised BBB and contributes to PND,54,55 and there is little research focusing on inflammatory cells and mediators flow from the CNS to the periphery through the BBB in PND. The impact of isoflurane on BBB permeability is still debated, isoflurane anesthesia can disrupt the integrity of the BBB, resulting in increased permeability,56,57 in contrast, Altay O et al. found that isoflurane posttreatment prevents BBB disruption after SAH in mice. 58 Interestingly, localized BBB disruption might facilitate glymphatic transport.59 –61 Therefore, BBB disruption and glymphatic clearance likely serve complementary roles with partially overlapping mechanisms, but the interaction of BBB disruption and glymphatic transport in PND is worthwhile investigating in the following study with strict design.

There are limitations to this study. First, the occurrence and development of PND is influenced by individual susceptibility, and advanced age is one of the most important risk factors. 62 The glymphatic influx also shows progressive degeneration with age, 63 loss of perivascular AQP4 localization may render the aging brain vulnerable to neurotoxic protein deposition. 44 Therefore, future studies must be conducted in aged mice in order to confirm the results obtained in our study and improve the translational potential of the findings. Second, the cisterna magna injection may influence intracranial pressure (ICP) and CSF dynamics. The CSF tracer injection speed in our study was 1.0 μL/min for 10 min.In mice,1.0 μL/min infusion rate did not change the physiological direction of CSF flow, 34 but ICP was slightly increased (about 1∼2.5 mmHg)34,64 and quickly returned to baseline levels once infusion ceased. 34 Furthermore, ICP elevations do not contribute to the parenchymal CSF tracer distribution when using 1.0 μL/min for 10 min. 65 Therefore, the infusion protocols of 1.0 μL/min for 10 min may be suitable for glymphatic system in adult mice. Third, external electrocardiogram monitoring was unable to function due to strong magnetic field environment, heart rate and blood pressure were not monitored continuously during DCE-MRI.

Overall, the work described here provides the characterization of glymphatic system in the context of PND and opens the way to a better understanding of brain immune surveillance. The AQP4 depolarization-mediated blunted glymphatic system aggravates the progression of neuroinflammation and neurocognitive disorders initiated by long-term isoflurane anesthesia. Enhancing AQP4 polarization could alleviate cognitive impairment in PND mice through promoting glymphatic transport and decreasing inflammatory proteins levels. These results might help uncover the etiology of the immune imbalance typical of neuroinflammatory disorders, with promising implications for therapy.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jcb-10.1177_0271678X241237073 for Long-term isoflurane anesthesia induces cognitive deficits via AQP4 depolarization mediated blunted glymphatic inflammatory proteins clearance by Rui Dong, Yuqiang Han, Pin Lv, Linhao Jiang, Zimo Wang, Liangyu Peng, Shuai Liu, Zhengliang Ma, Tianjiao Xia, Bing Zhang and Xiaoping Gu in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82171193, 82001132, and 81730033), the Key Talent Project for Strengthening Health during the 13th Five-Year Plan Period (ZDRCA2016069), Jiangsu Provincial Medical Key Discipline (ZDXK202232).

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ contributions: R.D. and Y.H. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; R.D. and P.L. performed the MRI experiments and analysis the data; L.J. and Z.W. contributed to behavioral test; Y.P. and S.L. contributed cell culture and immunofluorescence. P.L, Z.M., and T.X. contributed to the design and manuscript revision. T.X., B.Z, and X.G. conceived and supervised the project, revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Supplementary material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iD: Bing Zhang https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3953-0290

References

- 1.Evered L, Silbert B, Scott DA, et al. Association of changes in plasma neurofilament light and tau levels with anesthesia and surgery: Results from the CAPACITY and ARCADIAN studies. JAMA Neurol 2018; 75: 542–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evered L, Silbert B, Knopman DS, et al. Recommendations for the nomenclature of cognitive change associated with anaesthesia and surgery-2018. Anesthesiology 2018; 129: 872–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin X, Chen Y, Zhang P, et al. The potential mechanism of postoperative cognitive dysfunction in older people. Exp Gerontol 2020; 130: 110791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Needham MJ, Webb CE, Bryden DC. Postoperative cognitive dysfunction and dementia: what we need to know and do. Br J Anaesth 2017; 119: i115–i125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu B, Huang D, Guo Y, et al. Recent advances and perspectives of postoperative neurological disorders in the elderly surgical patients. CNS Neurosci Ther 2021; 28: 470–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plog BA, Nedergaard M. The glymphatic system in central nervous system health and disease: past, present, and future. Annu Rev Pathol 2018; 13: 379–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang L, Chopp M, Jiang Q, et al. Role of the glymphatic system in ageing and diabetes mellitus impaired cognitive function. Stroke Vasc Neurol 2019; 4: 90–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishida K, Yamada K, Nishiyama R, et al. Glymphatic system clears extracellular tau and protects from tau aggregation and neurodegeneration. J Exp Med 2022; 219: e20211275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xuan X, Zhou G, Chen C, et al. Glymphatic system: emerging therapeutic target for neurological diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2022; 2022: 6189170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 10.Harrison IF, Ismail O, Machhada A, et al. Impaired glymphatic function and clearance of tau in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Brain 2020; 143: 2576–2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mestre H, Hablitz LM, Xavier AL, et al. Aquaporin-4-dependent glymphatic solute transport in the rodent brain. Elife 2018; 7: e40070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iliff JJ, Wang M, Liao Y, et al. A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid β. Sci Transl Med 2012; 4: 147ra111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peng W, Achariyar TM, Li B, et al. Suppression of glymphatic fluid transport in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis 2016; 93: 215–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kress BT, Iliff JJ, Xia M, et al. Impairment of paravascular clearance pathways in the aging brain. Ann Neurol 2014; 76: 845–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Percie Du Sert N, Hurst V, Ahluwalia A, et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2020; 40: 1769–1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toft-Bertelsen TL, Larsen BR, Christensen SK, et al. Clearance of activity-evoked K transients and associated glia cell swelling occur independently of AQP4: a study with an isoform-selective AQP4 inhibitor. Glia 2021; 69: 28–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dong R, Han Y, Jiang L, et al. Connexin 43 gap junction-mediated astrocytic network reconstruction attenuates isoflurane-induced cognitive dysfunction in mice. J Neuroinflammation 2022; 19: 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwilasz AJ, Todd LS, Duran-Malle JC, et al. Experimental autoimmune encephalopathy (EAE)-induced hippocampal neuroinflammation and memory deficits are prevented with the non-opioid TLR2/TLR4 antagonist (+)-naltrexone. Behav Brain Res 2021; 396: 112896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kopp ND, Nygaard KR, Liu Y, et al. Functions of Gtf2i and Gtf2ird1 in the developing brain: transcription, DNA binding and long-term behavioral consequences. Hum Mol Genet 2020; 29: 1498–1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hablitz LM, Plá V, Giannetto M, et al. Circadian control of brain glymphatic and lymphatic fluid flow. Nat Commun 2020; 11: 4411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plá V, Bork P, Harnpramukkul A, et al. A real-time in vivo clearance assay for quantification of glymphatic efflux. Cell Rep 2022; 40: 111320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xavier ALR, Hauglund NL, von Holstein-Rathlou S, et al. Cannula implantation into the cisterna magna of rodents. J Vis Exp 2018; 135: 57378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng W, Zhang Y, Wang Z, et al. Microglia prevent beta-amyloid plaque formation in the early stage of an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model with suppression of glymphatic clearance. Alzheimers Res Ther 2020; 12: 125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dong R, Lv P, Han Y, et al. Enhancement of astrocytic gap junctions Connexin43 coupling can improve long-term isoflurane anesthesia-mediated brain network abnormalities and cognitive impairment. CNS Neurosci Ther 2022; 28: 2281–2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aspelund A, Antila S, Proulx ST, et al. A dural lymphatic vascular system that drains brain interstitial fluid and macromolecules. J Exp Med 2015; 212: 991–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ding X-B, Wang X-X, Xia D-H, et al. Impaired meningeal lymphatic drainage in patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Nat Med 2021; 27: 411–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gakuba C, Gaberel T, Goursaud S, et al. General anesthesia inhibits the activity of the “glymphatic system”. Theranostics 2018; 8: 710–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hablitz LM, Nedergaard M. The glymphatic system. Curr Biol 2021; 31: R1371–R1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma Q, Ries M, Decker Y, et al. Rapid lymphatic efflux limits cerebrospinal fluid flow to the brain. Acta Neuropathol 2019; 137: 151–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iliff JJ, Lee H, Yu M, et al. Brain-wide pathway for waste clearance captured by contrast-enhanced MRI. J Clin Invest 2013; 123: 1299–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cao J, Yao D, Li R, et al. Digoxin ameliorates glymphatic transport and cognitive impairment in a mouse model of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. Neurosci Bull 2021; 38: 181–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taoka T, Masutani Y, Kawai H, et al. Evaluation of glymphatic system activity with the diffusion MR technique: diffusion tensor image analysis along the perivascular space (DTI-ALPS) in Alzheimer’s disease cases. Jpn J Radiol 2017; 35: 172–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mestre H, Tithof J, Du T, et al. Flow of cerebrospinal fluid is driven by arterial pulsations and is reduced in hypertension. Nat Commun 2018; 9: 4878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iliff JJ, Wang M, Zeppenfeld DM, et al. Cerebral arterial pulsation drives paravascular CSF-interstitial fluid exchange in the murine brain. J Neurosci 2013; 33: 18190–18199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee H, Xie L, Yu M, et al. The effect of body posture on brain glymphatic transport. J Neurosci 2015; 35: 11034–11044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murlidharan G, Crowther A, Reardon RA, et al. Glymphatic fluid transport controls paravascular clearance of AAV vectors from the brain. JCI Insight 2016; 1: e88034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiong B, Li A, Lou Y, et al. Precise cerebral vascular atlas in stereotaxic coordinates of whole mouse brain. Front Neuroanat 2017; 11: 128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Munk AS, Wang W, Bèchet NB, et al. PDGF-B is required for development of the glymphatic system. Cell Rep 2019; 26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Da Mesquita S, Louveau A, Vaccari A, et al. Functional aspects of meningeal lymphatics in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 2018; 560: 185–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hsu S-J, Zhang C, Jeong J, et al. Enhanced meningeal lymphatic drainage ameliorates neuroinflammation and hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhotic rats. Gastroenterology 2021; 160: 1315–1329.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vandebroek A, Yasui M. Regulation of AQP4 in the Central nervous system. Int J Mol Sci 2020; 21: 1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu Z, Xiao N, Chen Y, et al. Deletion of aquaporin-4 in APP/PS1 mice exacerbates brain Aβ accumulation and memory deficits. Mol Neurodegener 2015; 10: 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu X, Hao J, Yao E, et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acid supplement alleviates depression-incident cognitive dysfunction by protecting the cerebrovascular and glymphatic systems. Brain Behav Immun 2020; 89: 357–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zeppenfeld DM, Simon M, Haswell JD, et al. Association of perivascular localization of aquaporin-4 with cognition and alzheimer disease in aging brains. JAMA Neurol 2017; 74: 91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang M, Iliff JJ, Liao Y, et al. Cognitive deficits and delayed neuronal loss in a mouse model of multiple microinfarcts. J Neurosci 2012; 32: 17948–17960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mogensen FL-H, Delle C, Nedergaard M. The glymphatic system (En)during inflammation. Int J Mol Sci 2021; 22: 7491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xie Z, Culley DJ, Dong Y, et al. The common inhalation anesthetic isoflurane induces caspase activation and increases amyloid beta-protein level in vivo. Ann Neurol 2008; 64: 618–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hablitz LM, Vinitsky HS, Sun Q, et al. Increased glymphatic influx is correlated with high EEG Delta power and low heart rate in mice under anesthesia. Sci Adv 2019; 5: eaav5447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lunardi N, Sica R, Atluri N, et al. Disruption of rapid eye movement sleep homeostasis in adolescent rats after neonatal anesthesia. Anesthesiology 2019; 130: 981–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coleman K, Robertson ND, Dissen GA, et al. Isoflurane anesthesia has long-term consequences on motor and behavioral development in infant rhesus macaques. Anesthesiology 2017; 126: 74–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Di Palma C, Goulay R, Chagnot S, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid flow increases from newborn to adult stages. Dev Neurobiol 2018; 78: 851–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tarasoff-Conway JM, Carare RO, Osorio RS, et al. Clearance systems in the brain-implications for alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol 2015; 11: 457–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Verheggen ICM, Van Boxtel MPJ, Verhey FRJ, et al. Interaction between blood-brain barrier and glymphatic system in solute clearance. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2018; 90: 26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vasunilashorn SM, Ngo LH, Dillon ST, et al. Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid inflammation and the blood-brain barrier in older surgical patients: the role of inflammation after surgery for elders (RISE) study. J Neuroinflammation 2021; 18: 103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang T, Velagapudi R, Terrando N. Neuroinflammation after surgery: from mechanisms to therapeutic targets. Nat Immunol 2020; 21: 1319–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tétrault S, Chever O, Sik A, et al. Opening of the blood-brain barrier during isoflurane anaesthesia. Eur J Neurosci 2008; 28: 1330–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Noorani B, Chowdhury EA, Alqahtani F, et al. Effects of volatile anesthetics versus ketamine on blood-brain barrier permeability via lipid-mediated alterations of endothelial cell membranes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2023; 385: 135–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Altay O, Suzuki H, Hasegawa Y, et al. Isoflurane attenuates blood-brain barrier disruption in ipsilateral hemisphere after subarachnoid hemorrhage in mice. Stroke 2012; 43: 2513–2516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Han M, Seo H, Choi H, et al. Localized modification of water molecule transport after focused Ultrasound-Induced Blood-Brain barrier disruption in rat brain. Front Neurosci 2021; 15: 685977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rezai AR, Ranjan M, D’Haese P-F, et al. Noninvasive hippocampal blood-brain barrier opening in Alzheimer’s disease with focused ultrasound. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020; 117: 9180–9182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.D’Haese P-F, Ranjan M, Song A, et al. β-Amyloid plaque reduction in the hippocampus after focused ultrasound-induced blood-brain barrier opening in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Hum Neurosci 2020; 14: 593672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Au E, Thangathurai G, Saripella A, et al. Postoperative outcomes in elderly patients undergoing cardiac surgery with preoperative cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth Analg 2023; 136: 1016–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Giannetto M, Xia M, Stæger FF, et al. Biological sex does not predict glymphatic influx in healthy young, middle aged or old mice. Sci Rep 2020; 10: 16073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bedussi B, Almasian M, de Vos J, et al. Paravascular spaces at the brain surface: low resistance pathways for cerebrospinal fluid flow. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2018; 38: 719–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mestre H, Mori Y, Nedergaard M. The brain’s glymphatic system: current controversies. Trends Neurosci 2020; 43: 458–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jcb-10.1177_0271678X241237073 for Long-term isoflurane anesthesia induces cognitive deficits via AQP4 depolarization mediated blunted glymphatic inflammatory proteins clearance by Rui Dong, Yuqiang Han, Pin Lv, Linhao Jiang, Zimo Wang, Liangyu Peng, Shuai Liu, Zhengliang Ma, Tianjiao Xia, Bing Zhang and Xiaoping Gu in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism