Abstract

We present the complete genome sequences of two strains of Teredinibacter turnerae, SR01903 and SR02026, shipworm endosymbionts isolated from the gills of Lyrodus pedicellatus and Teredo bartschi, respectively, and derived from Oxford Nanopore sequencing. These sequences will aid in the comparative genomics of shipworm endosymbionts and understanding of host-symbiont selection.

Announcement

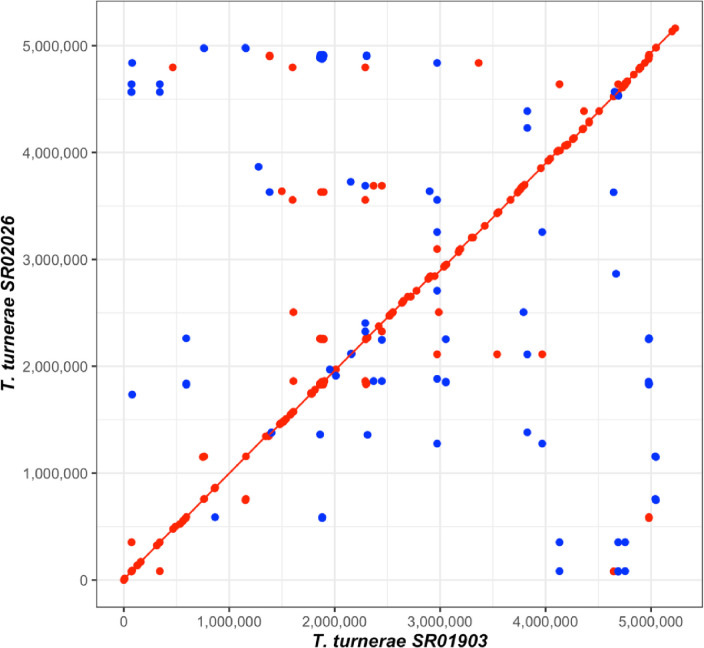

Teredinibacter species are cultivable intracellular symbionts of xylotrophic, bivalve wood-borers (Teredinidae) (1–4) and have been shown to secrete lignocellulolytic enzymes that aid in host digestion (5, 6). Wood containing live specimens of Lyrodus pedicellatus and Teredo bartschi was collected from the Indian River Lagoon, Merit Island, FL. (N 28.40605 W 80.66034) on January 24, 2020, and subsequently maintained in laboratory culture. Strain SR01903 was isolated from the gill of a single specimen of L. pedicellatus immediately after collection from the wild. Strain SR02026 was isolated from the gill of a fourth-generation lab-reared specimen of T. bartschi. Bacterial isolations were performed as in O’Connor et al., 2014. Briefly, gills were removed by dissection and homogenized in 1.0 mL of SBM medium (7) in an autoclave-sterilized glass dounce homogenizer. Homogenates were streaked onto culture plates containing 1.0% Bacto agar prepared in shipworm basal medium (SBM) at pH 8.0 supplemented with 0.2% w/v powdered cellulose (Sigmacell Type 101; Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.025% NH4Cl. Plates were then incubated at 30 °C. When individual colonies appeared, a single colony was picked, re-streaked, and regrown. This process was repeated until clonal isolates were achieved. Genomic DNA was extracted from the resulting clonal isolates, as in O’Connor et al., 2014 using the Qiagen DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit following the manufacturer’s recommended protocol for cultured cells with the exception that DNA was eluted with two 75 μL volumes of AE buffer preheated to 56 °C. DNA quality and length were assessed on Tapestation (Agilent Technologies, US). Nanopore (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, UK) sequencing was performed without DNA fragmentation or size selection. The sequencing library was prepared using the Q20+ chemistry Ligation Sequencing Kit (SQK-LSK112) and sequenced on a MinION (Mk1B) instrument using a R10.4 (FLO-MIN112) flow cell. Bases were called using Guppy v6.4.6 with the high-accuracy (HAC) algorithm, and default read quality filtering. Adapters were trimmed from reads using Porechop v0.2.4 (https://github.com/rrwick/Porechop) and filtered to remove reads less than 1 Kb using Filtlong v0.2.1 (https://github.com/rrwick/Filtlong). De novo assembly was performed with Flye v2.9.2 (https://github.com/fenderglass/Flye) (8) followed by contig correction and consensus generation with Racon v1.5.0 (https://github.com/lbcb-sci/racon) and Medaka v1.8.0 (https://github.com/nanoporetech/medaka). Assemblies were then circularized and rotated to start at dnaA, predicted by prodigal v2.6.3 (9) with Circlator v1.5.5 (https://github.com/sanger-pathogens/circlator) (10). Chromosomal assemblies were produced for both strains and annotated using the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (PGAP) (Table 1). All software was run using default settings unless otherwise noted. The primary sequences were 98.67% identical based on the calculated average nucleotide identity (ANI) (11) and highly syntenic (Fig. 1) (12).

Table 1.

Genome sequencing, assembly, and annotation of Teredinibacter strains

| Strain | SR01903 | SR02026 |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Host | L. pedacellatus | T. bartschi |

| Reads | 77,041 | 253,198 |

| Bases (M) | 289.9 | 306.2 |

| Read N50 | 11,088 | 2,331 |

| Assembly (bp) | 5,229,132 | 5,163,139 |

| Coverage | 52x | 44x |

| GC content (%) | 50.9 | 50.9 |

| Genes | 4,207 | 4,142 |

| CDS | 4,152 | 4,086 |

| rRNA (complete) | 3 | 3 |

Figure 1.

Synteny plot comparing the genome sequences of SR01903 and SR02026. A MUMmer3 plot was generated with NUCmer v3.1 (12) using NUCmer to assess synteny and completion. Minimum exact matches of 20bp are represented as a dot with lines representing match lengths >20bp. Forward matches are displayed in red, while reverse matches are shown in blue.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the following awards to DLD: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NA19OAR0110303), Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (GBMF 9339), National Institutes of Health (1R01AI162943–01A1, subaward: 10062083-NE), and Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory internal research and development funds. The National Science Foundation (DBI 1722553) also funded some equipment used in this research. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Data availability

The complete genome sequences for SR01903 and SR02026 have been deposited in GenBank under the accession numbers CP149818 and CP149819, respectively. The Oxford Nanopore sequencing reads are available from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the accession numbers SRR28421271 and SRR28421270, respectively.

References

- 1.Yang JC, Madupu R, Durkin AS, Ekborg NA, Pedamallu CS, Hostetler JB, Radune D, Toms BS, Henrissat B, Coutinho PM, Schwarz S, Field L, Trindade-Silva AE, Soares CAG, Elshahawi S, Hanora A, Schmidt EW, Haygood MG, Posfai J, Benner J, Madinger C, Nove J, Anton B, Chaudhary K, Foster J, Holman A, Kumar S, Lessard PA, Luyten YA, Slatko B, Wood N, Wu B, Teplitski M, Mougous JD, Ward N, Eisen JA, Badger JH, Distel DL. 2009. The Complete Genome of Teredinibacter turnerae T7901: An Intracellular Endosymbiont of Marine Wood-Boring Bivalves (Shipworms). PLoS ONE 4:e6085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altamia MA, Shipway JR, Stein D, Betcher MA, Fung JM, Jospin G, Eisen J, Haygood MG, Distel DL. 2020. Teredinibacter waterburyi sp. nov., a marine, cellulolytic endosymbiotic bacterium isolated from the gills of the wood-boring mollusc Bankia setacea (Bivalvia: Teredinidae) and emended description of the genus Teredinibacter. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 70:2388–2394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altamia MA, Shipway JR, Stein D, Betcher MA, Fung JM, Jospin G, Eisen J, Haygood MG, Distel DL. 2021. Teredinibacter haidensis sp. nov., Teredinibacter purpureus sp. nov. and Teredinibacter franksiae sp. nov., marine, cellulolytic endosymbiotic bacteria isolated from the gills of the wood-boring mollusc Bankia setacea (Bivalvia: Teredinidae) and emended description of the genus Teredinibacter. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Distel DL, Morrill W, MacLaren-Toussaint N, Franks D, Waterbury J. 2002. Teredinibacter turnerae gen. nov., sp. nov., a dinitrogen-fixing, cellulolytic, endosymbiotic gamma-proteobacterium isolated from the gills of wood-boring molluscs (Bivalvia: Teredinidae). International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 52:2261–2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Connor RM, Fung JM, Sharp KH, Benner JS, McClung C, Cushing S, Lamkin ER, Fomenkov AI, Henrissat B, Londer YY, Scholz MB, Posfai J, Malfatti S, Tringe SG, Woyke T, Malmstrom RR, Coleman-Derr D, Altamia MA, Dedrick S, Kaluziak ST, Haygood MG, Distel DL. 2014. Gill bacteria enable a novel digestive strategy in a wood-feeding mollusk. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:E5096–E5104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sabbadin F, Pesante G, Elias L, Besser K, Li Y, Steele-King C, Stark M, Rathbone DA, Dowle AA, Bates R, Shipway JR, Cragg SM, Bruce NC, McQueen-Mason SJ. 2018. Uncovering the molecular mechanisms of lignocellulose digestion in shipworms. Biotechnol Biofuels 11:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waterbury JB, Calloway CB, Turner RD. 1983. A Cellulolytic Nitrogen-Fixing Bacterium Cultured from the Gland of Deshayes in Shipworms (Bivalvia: Teredinidae). Science 221:1401–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kolmogorov M, Yuan J, Lin Y, Pevzner PA. 2019. Assembly of long, error-prone reads using repeat graphs. Nat Biotechnol 37:540–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hyatt D, Chen G-L, LoCascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. 2010. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics 11:119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunt M, Silva ND, Otto TD, Parkhill J, Keane JA, Harris SR. 2015. Circlator: automated circularization of genome assemblies using long sequencing reads. Genome Biol 16:294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodriguez-R LM, Konstantinidis KT. 2016. The enveomics collection: a toolbox for specialized analyses of microbial genomes and metagenomes. preprint. PeerJ Preprints. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurtz S, Phillippy A, Delcher AL, Smoot M, Shumway M, Antonescu C, Salzberg SL. 2004. Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biol 5:R12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The complete genome sequences for SR01903 and SR02026 have been deposited in GenBank under the accession numbers CP149818 and CP149819, respectively. The Oxford Nanopore sequencing reads are available from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the accession numbers SRR28421271 and SRR28421270, respectively.