SUMMARY

Fluorescent genetically encoded voltage indicators report transmembrane potentials of targeted cell-types. However, voltage-imaging instrumentation has lacked the sensitivity to track spontaneous or evoked high-frequency voltage oscillations in neural populations. Here we describe two complementary TEMPO voltage-sensing technologies that capture neural oscillations up to ~100 Hz. Fiber-optic TEMPO achieves ~10-fold greater sensitivity than prior photometry systems, allows hour-long recordings, and monitors two neuron-classes per fiber-optic probe in freely moving mice. With it, we uncovered cross-frequency-coupled theta- and gamma-range oscillations and characterized excitatory-inhibitory neural dynamics during hippocampal ripples and visual cortical processing. The TEMPO mesoscope images voltage activity in two cell-classes across a ~8-mm-wide field-of-view in head-fixed animals. In awake mice, it revealed sensory-evoked excitatory-inhibitory neural interactions and traveling gamma and 3–7 Hz waves in the visual cortex, and previously unreported propagation directions for hippocampal theta and beta waves. These technologies have widespread applications probing diverse oscillations and neuron-type interactions in healthy and diseased brains.

INTRODUCTION

Fluorescence imaging studies of neural activity using genetically encoded voltage indicators (GEVIs) have mainly focused on detecting the spiking dynamics of identified neuron classes at cellular resolution.1–6 However, complementary to such approaches, fiber-optic studies of subthreshold voltage activity across populations of genetically identified neuron-types can yield insights about neural circuit dynamics in freely behaving rodents.7–9 Neural population-level imaging studies have also used GEVIs to monitor the spatiotemporal dynamics of sensory-evoked potentials or slow voltage oscillations and activity in anesthetized or awake head-fixed animals.10–13 A key limitation, however, is that prior instruments for optical voltage-sensing in either freely moving or head-restrained mammals have lacked the sensitivity to detect rhythms at frequencies above the theta range (~5–9 Hz) without substantial averaging across experimental trials.7,9,13 Due to this technology gap, how specific neuron-types shape the spatiotemporal dynamics of high-frequency oscillations (i.e., ≳10 Hz) remains poorly understood.

Addressing this challenge is crucial, because high-frequency oscillations appear to be integral to many important brain processes. Neural oscillations in the beta (~15–30 Hz) and gamma (~35–100 Hz) frequency bands are implicated in attention,14,15 motor control,16,17 memory18,19,20,21 and sensory processing.22,23 Impairments of high-frequency oscillations arise in brain disease, including cognitive disorders,24 schizophrenia,25 epilepsy,26–28 and Alzheimer’s29–31 and Parkinson’s diseases.32–34 Well-known hypotheses posit that high-frequency oscillations emerge via interactions between excitatory and inhibitory cells, or between coupled sets of mutually inhibitory interneurons.9,35–37 Available evidence points to inhibitory interneurons, especially fast-spiking interneurons,22,38,39 as being important for high-frequency rhythms, but far more work is needed to clarify how different neuron-types and both local and long-distance neural interactions may shape rhythmic synchronization.9,14,21,35–37

To enable studies that dissect how different neuron classes contribute to high-frequency oscillations and waves, this paper describes several new tools and techniques based on the TEMPO (Transmembrane Electrical Measurement Performed Optically) approach that we introduced previously in a fiber-optic format.7 TEMPO captures the aggregate, population-level voltage dynamics of specific neuron-types in behaving mammals. The motivation for such measurements is that, just as in electrophysiology, optical studies of neural population dynamics can reveal collective activity patterns that may not be discernible from single-cell activity traces.

TEMPO has 4 basic ingredients: (1) Use of one or more GEVIs to track voltage activity in chosen neuron-types, which may be targeted using viruses, transgenic animals, or other means of selective labeling; (2) Use of a reference fluor that is not voltage-sensitive to track hemodynamic, brain motion and other artifacts that impact the detection of voltage-sensitive fluorescence signals; (3) A dual-color fluorescence measurement apparatus; (4) Computational unmixing of the artifactual signals from the records of neural voltage activity.

Since both TEMPO and extracellular local electric field potential (LFP) recordings measure neural population voltage activity, it might be tempting to view the two as analogous; however, LFP recordings generally reflect the contributions of multiple unidentified cell-types, are influenced by electrode shape, orientation and composition, and comprise a time-varying, unknown mixture of signal sources across multiple length scales—from currents within ~0.1 mm of the electrode to volume-conducted signals originating up to 1 cm away.40 By comparison, TEMPO probes the local intracellular potentials of user-selected cell-types and is free from volume-conduction effects.

Here, we present an ultrasensitive form of fiber-optic TEMPO for use in freely moving animals and a TEMPO mesoscope for voltage-imaging over tissue areas up to 8 mm in diameter in head-fixed behaving animals. Both instruments are unprecedented in that they can track high-frequency neural voltage oscillations (up to ~100 Hz) without trial-averaging. In addition, we created a transgenic Cre-dependent reporter mouse line expressly designed for TEMPO studies. While most of our investigations relied on viral expression strategies, this reporter line provides a convenient option for uniform dual-fluor labeling and high reproducibility across animals without virus use. Finally, we describe a novel algorithm to unmix biological artifacts and noise from voltage signals while preserving the fidelity of photon shot noise-limited, high-frequency voltage dynamics.

Our fiber-optic TEMPO recordings rely on a photometry apparatus that we call uSMAART (ultra-Sensitive Measurement of Aggregate Activity in Restricted cell-Types). We distinguish the TEMPO concept from the uSMAART apparatus, as the former need not be implemented in optical fiber, and the latter is an ultrasensitive fiber-optic system that does more than just voltage-sensing, including monitoring fluorescent [Ca2+] or neuromodulator reporters. The uSMAART apparatus has dual-channel fluorescence detection, which, when used for TEMPO, allows voltage-sensing of two targeted neuron classes per fiber-optic probe while also tracking the emissions of a reference fluor. uSMAART has ~10-fold greater sensitivity than prior photometry systems for use in freely moving animals, and, when combined with the best available GEVI for sensing subthreshold voltages, allows a ~100-fold improvement over prior fiber-optic studies of voltage dynamics.

With uSMAART, we measured population voltage activity at frequencies up to the gamma band (~35–100 Hz) in freely behaving mice, in sparse and dense cell-types, without trial-averaging. Illustrating the importance of this new capability, we uncovered cross-frequency coupling (CFC) between pairs of voltage rhythms of different frequencies. In CFC, a lower frequency oscillation modulates the attributes of a higher frequency rhythm. CFC has previously been observed in electrical recordings in multiple animal species, and different forms of CFC associate with various cognitive states and diseases.27,32,41–45 uSMAART allowed the first observations of CFC within the transmembrane potentials of specific neuron-types, namely delta frequency (0.5–4 Hz) modulations of low- (30–60 Hz) and high-gamma (70–100 Hz) rhythms in parvalbumin-expressing (PV) interneurons in the visual cortex of anesthetized mice, as well as theta (5–9 Hz) modulations of gamma (40–70 Hz) rhythms in PV cells in the hippocampus of freely moving mice. By using uSMAART and two GEVIs, we monitored two neuron-types at once, which revealed the differential voltage dynamics of excitatory and inhibitory cell-types in visual cortex and hippocampus.

Since fiber photometry measurements are limited to signals from just below the fiber tip, we created a complementary TEMPO mesoscope to image the population voltage dynamics of two neuron-types at once in head-restrained mice. The mesoscope can image low-gamma (30–60 Hz) activity across a ~50 mm2 field-of-view or take high-speed (300 Hz) snapshots of wave propagation over a ~21 mm2 area, at a spatial resolution >10 times finer than those provided by the densest electrode arrays for electrocorticography (ECoG).46,47 With this system, we imaged traveling neocortical voltage waves with CFC synchronized across the delta and gamma bands in PV and layer 2/3 pyramidal cells of anesthetized mice. In awake mice, we found paired trains of visually evoked waves in these cell-types; visual stimulation elicited traveling gamma waves, followed by traveling 3–7 Hz waves at stimulus offset. In hippocampus, TEMPO imaging of PV interneurons provided the first evidence that hippocampal beta rhythms are actually traveling waves and can propagate in a pair of orthogonal anatomic directions. We also performed the first imaging studies of pathway-specific neuronal voltage oscillations by using axonal labeling to target hippocampal pyramidal neurons with a specific projection pattern. Further, our imaging studies of hippocampal theta waves revealed these waves can propagate bidirectionally along the CA1-CA3 axis, which was previously unknown. Finally, by using two GEVIs, we imaged the joint dynamics of visual cortical excitatory and inhibitory neural 3–7 Hz waves evoked in response to visual stimulation.

Overall, the instruments, reporter mouse and analytics introduced here allow a wide range of previously infeasible studies of high-frequency (i.e., ~10–100 Hz) transmembrane voltage dynamics in one or two neuron-classes at once, in freely moving or head-fixed behaving animals.

RESULTS

Ultra-sensitive fiber photometry system.

To capture high-frequency oscillations up to ~100 Hz in freely moving mammals, we created the ultra-sensitive fiber photometry system uSMAART. Prior fiber apparatus have been unable to capture optical voltage traces revealing high-frequency neural oscillations in freely behaving mice. This is challenging, because (i) fiber photometry measurements from GEVIs usually involve very weak fluorescence signals (~50–250 pW), (ii) neural oscillations at higher frequencies afford fewer GEVI signal photons per oscillation cycle, (iii) GEVIs alter their emissions by only ~0.1–1% per mV of voltage change, (iv) hemodynamics and tissue motion typically induce artifactual signals of this magnitude or greater, and (v) fiber-optic apparatus generally have multiple noise sources, including light sources, photodetectors, amplifiers and fiber autofluorescence.

Our own past work on fiber-optic TEMPO came nearest to the landmark achieved here but fell short in key respects.7,9 Specifically, our studies of high-frequency oscillations used head-fixed mice and averages over hundreds of trials to attain statistical conclusions.7 A follow-up study, which also involved substantial trial-averaging, used freely behaving mice but was confined to quantifications of cross-hemisphere gamma-band synchronization across a pair of fiber-optic probes, rather than capturing high-frequency voltage dynamics in unaveraged traces.9 To surpass this past work, we examined our prior TEMPO instrumentation and datasets with the goal of first identifying and then reducing the remnant noise sources.

We found that optical mode-hopping in the fiber conveying laser light to the brain was the main limiting noise source in our earlier studies and arose selectively during unconstrained animal locomotion and thus motion of the fiber (Figure S1A–E). Mode-hopping is a type of speckle noise occurring when coherent laser light propagates in multimode fiber, due to fluctuating interference between light in different modes when the fiber flexes.48 To prevent speckle, one might consider incoherent light-emitting diodes (LEDs) as alternative light sources. But solid-state lasers are generally more stable than LEDs and can be modulated at higher frequencies (~50–100 kHz in this paper) at which detectors usually have much lower noise than at lower frequencies (e.g. ~5 kHz for LEDs) (Figure S1C). By implication, even when LEDs are used for photometry with detectors of near-zero electronic noise, such as a photon-counting photomultiplier tube49 or a scientific-grade CMOS (sCMOS) camera50–52, the additional illumination noise (Figures S1A,B) prevents the system from attaining the low noise floor achievable in principle with laser illumination.

These considerations yielded a key engineering principle for building fiber-photometry systems for freely moving animals with greater sensitivity than prior LED- or laser-based versions. Namely, for illumination sources one should use high-frequency-modulated lasers for their superior stability, but this choice necessitates a means of breaking the illumination’s coherence for the sake of avoiding fiber-optic mode-hopping noise when the animal is actively behaving. By embodying this design principle, uSMAART surpasses the sensitivity of prior LED-based fiber photometry systems9,50 and of laser-based systems that lacked active suppression of speckle noise.7,53 In total, uSMAART has 4 modules, all designed to minimize noise: (i) a low-noise laser illumination module, enabling; (ii) a decoherence module to preclude mode-hopping noise; (iii) a high-efficiency fluorescence sensing module; (iv) a phase-sensitive detection module with digital lock-in amplifiers (Figure 1A; STAR Methods). The laser illumination module is about 10-times more stable than that of prior photometry systems (Figure S1E);7,9,54,55 when it is used together with the decoherence module, the r.m.s. laser illumination fluctuations at the specimen of only ~0.004% are impervious to fiber and animal motion (Figure S1D,E). The fluorescence sensing module minimizes bleedthrough of emissions and photon shot noise from the reference fluor into the detection channel for the GEVI, and the phase-sensitive detection module unmixes emission signals that are excited by different lasers but captured on the same photodetector.

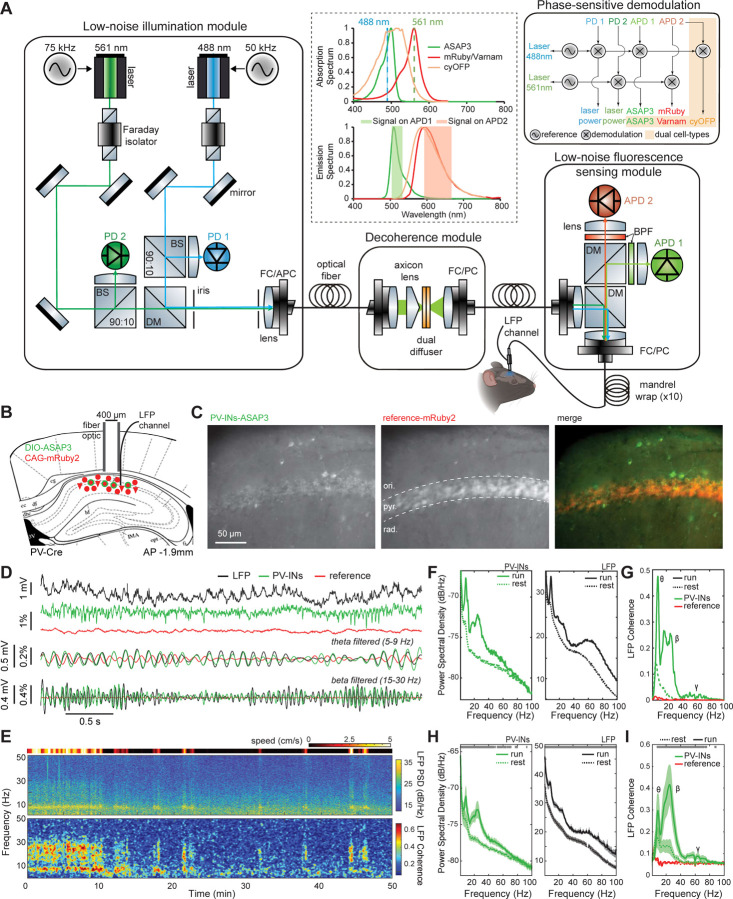

Figure 1: uSMAART fiber photometry captures population-level voltage dynamics, at frequencies up to 100 Hz, of genetically targeted neuron-types in freely behaving mice.

(A) Schematic of the 4 modules in uSMAART. Within a low-noise illumination module (left box), the emissions of blue and green lasers are modulated at distinct frequencies (50 and 75 kHz, respectively) and jointly coupled into an optical fiber via an angled physical contact fiber connector (FC/APC). A portion of the light from each laser is split from the main pathway using a 90:10 beam splitter (BS) and monitored with a photodiode (PD). To achieve immunity to fiber motion artifacts, the illumination passes through a free-space, dual-stage optical diffuser within a decoherence module (middle box) and is then coupled back into optical fiber via a physical contact fiber connector (FC/PC). A low-noise fluorescence sensing module (lower right box) achieves high-efficiency, low-noise fluorescence detection using a pair of avalanche photodiodes (APDs) and a combination of dichroic mirrors (DMs) and bandpass filters (BPFs) that minimizes crosstalk between fluorescence channels. To attenuate noise from spatial mode-hopping, the fiber conveying light to and from the brain is wrapped ten times around a mandrel. Local field potential (LFP) signals are measured in the brain near the tip of the optical fiber. Electronics for phase-sensitive frequency demodulation (upper right box) isolate signals conveying the illumination and fluorescence emission powers. In the dual cell-type voltage-sensing configuration (orange shading), cyOFP emissions are captured on APD2 but demodulated at 50 kHz owing to their excitation by the 488-nm laser. Inset (dashed box): Absorption and emission fluorescence spectra for single and dual cell-type voltage-sensing configurations, for which an mRuby and cyOFP, respectively, are the reference fluors.

(B) To track the aggregate transmembrane voltage activity of CA1 hippocampal parvalbumin-positive (PV) neurons (C–I), we virally expressed the ASAP3 voltage-indicator in PV-Cre mice, along with a reference fluor, mRuby2. As schematized in a coronal brain section, we implanted an optical fiber (400-μm diameter core) and an LFP electrode just atop CA1, to capture optical and electrical signals, respectively. AP: antero-posterior coordinate of the section relative to bregma.

(C) Coronal hippocampal section from a PV-Cre mouse, imaged by fluorescence microscopy, showing expression of green fluorescent ASAP3 in PV interneurons (PV-INs; left), strong expression of red-fluorescent mRuby2 in the stratum pyramidale (pyr.) layer of CA1 and weaker expression in stratum oriens (ori.) and stratum radiatum (rad.) (middle), and the overlap of the two expression patterns (right). Scale bar: 50 µm.

(D) Example traces showing concurrently acquired, LFP (black trace) and fluorescence signals from ASAP3 (green trace) and mRuby2 (red trace) in a freely behaving PV-Cre mouse, as well as overlaid, bandpass-filtered versions of the three traces in the theta (5–9 Hz) and beta (15–30 Hz) frequency ranges, revealing a strong concordance between the optical and electrical recordings. (The LFP is an extracellular measurement and thus is anti-correlated with the optical measurement of transmembrane voltage. Owing to the negative voltage-sensitivity of the indicators used, scale bars for all fluorescence indicator traces elsewhere in the paper are shown with negative units so that upward-sloped traces convey membrane depolarization. Whereas, here the scale bars for ASAP3 signals have positive units, for the sake of showing the phase alignment between oscillations in the LFP and ASAP3 recordings).

(E) Color plots of locomotor speed (top), a time-dependent spectrogram of the LFP (middle), and the frequency-dependent coherence between the LFP and ASAP3 signals (bottom) across a 50-min continuous recording from the same mouse as in (D). Note the bouts of high theta- and beta-band coherence specifically when the mouse is running.

(F) Power spectral density plots for the LFP (right) and ASAP3 fluorescence signals (left) determined from joint, continuous 50-min recordings from the same mouse as in (D), computed separately for periods when the mouse was running (solid curve) or resting (dashed curve). LFP and ASAP3 signals exhibit substantial power in the theta (5–9 Hz) and beta (15–30 Hz) frequency ranges during running bouts but not during rest.

(G) Plots of the frequency-dependent coherence between LFP signals and either the ASAP3 fluorescence trace (green curves), or the mRuby2 trace (red curves), for time periods when the mouse of (D) was running (solid curves) or resting (dashed curves). Note the theta, beta and gamma activity specific to periods of locomotion.

(H) Same as (F) but averaged across n=6 mice. Red dots near the top of the plots in H and I mark frequencies at which the y-axis values during running bouts differed significantly from those during resting periods (signed-rank tests; p<0.05; n=6 mice).

(I) Same as (G) but averaged across n=6 mice. Coherence in the theta, beta and gamma frequency bands significantly increased during locomotion.

To quantitatively evaluate uSMAART against prior LED- or laser-based photometry apparatus that do not follow the uSMAART design principle,7,9 we generated artificial 50 Hz signal bursts using a movable fluorescent sample (Figure S1F) and verified uSMAART boosts sensitivity about ten-fold (Figure S1G–I). Further, for uSMAART studies in the live brain, we took LFP recordings at the same tissue sites to support our interpretations of the optical traces. We stipulated that, as in our prior studies of low-frequency rhythms,7,9 all high-frequency optical voltage events should be accompanied by a coherent rise in LFP signals in the same frequency band, not just by a concomitant rise in high-frequency LFP power over the event time-course7,9 (Figure S1J–N). This criterion might, in principle, lead one to overlook optical voltage signals from certain forms of neural activity that are not coherent with the LFP (Discussion), but ensuring coherence between the two modalities affords additional confidence in the tiny optical signals arising from high-frequency events. We applied this coherence criterion to every biological phenomenon studied in this paper but not every single recording, for in some mice we omitted LFP recordings for the sake of experimental simplicity.

In addition to unprecedented detection sensitivity and immunity to fiber motion, uSMAART allows concurrent recordings from two cell-types. This required an innovation beyond our prior TEMPO studies of one neuron-class, which combined a green GEVI to track voltage signals and a red reference fluor to track hemodynamic and other artifacts. For studies with two GEVIs, we tried using an infrared reference fluor, but, due to the wavelength-dependence of hemoglobin absorption and light scattering,56 an infrared fluor poorly tracked the artifacts affecting visible fluorescence. Instead, we combined spectrally distinct green and red GEVIs along with a long Stokes-shift fluorescent protein, cyOFP,57 of which the absorption spectrum overlaps that of the green GEVI and the emission spectrum overlaps that of the red GEVI (Figure 1A). This labeling approach, when applied along with two light sources modulated at distinct frequencies, enabled unambiguous detection of signals from the 3 fluors using only 2 fluorescence detection channels.

Our in vivo studies explored uSMAART’s ability to capture high-frequency neural dynamics, starting with densely labeled neurons of a single class in head-fixed mice (Figure S2) and then progressing to sparsely labeled cells in freely moving mice (Figures 1,2). We followed a similar progression for studies of two cell-types (Figures S2, S3 and 3). Throughout, we used various GEVIs, including the FRET-opsins Ace-mNeon1,2 Varnam18 and Varnam2,1 and the GFP-based GEVI ASAP3.58 Given our interests in sub-threshold oscillations, ASAP3 proved superior due to its ~10-fold greater sensitivity at subthreshold voltages (1% ΔF/F for 1 mV changes between –100 and –40 mV; Figure S1O). Altogether, using uSMAART and ASAP3, which each provided a ~10-fold sensitivity gain (see Figures S1I and S1O, respectively), we achieved ~100-fold greater sensitivity than prior TEMPO measurements.7,9 This ~100-fold improvement was vital to observing the high-frequency neural phenomena described below.

Figure 2: uSMAART captures cell-type specific cross-frequency coupling in anesthetized and freely behaving mice.

(A–F) Delta-gamma frequency coupling in the membrane potential of ASAP3-labeled PV interneurons in the primary visual cortex (V1) of a ketamine-xylazine anesthetized mouse.

(A) Upper: Example trace of PV cell voltage dynamics showing up- and down-state transitions. Filter versions of the trace illustrate that power in the low- (30–60 Hz; Middle) and high-gamma (70-–100 Hz; Bottom) frequency bands both increased during up-states. (B) Two example epochs of up- and down-state transitions, with raw and gamma filtered traces shown as in (A).

(C) A wavelet spectrogram, with a logarithmic y-axis, averaged over 257 oscillation cycles in the delta frequency range (centered at 0.9 Hz, the frequency of peak delta power), reveals two distinct high-frequency power spectral peaks that arise at different phases of the delta rhythm. In panels C, D, the convention used for the phase of the delta oscillation is that 0-deg. refers to the trough of the oscillation, i.e., the greatest hyperpolarization in the TEMPO signal.

(D) Plot of the mean fluorescence signal in the delta frequency band (0.9 ± 0.25 Hz) (black trace; left axis), overlaid with plots of the delta phase-dependent oscillations of signal magnitude in the low (30–60 Hz; olive trace) and high (70–110 Hz; dashed olive trace) gamma ranges (right axis). As in (A, B), the plot shows distinct delta-phase shifts (dashed vertical lines; n = 122 delta events) for amplitude modulations of the low- and high-frequency gamma rhythms. The two arrows indicate the two delta phases at which the magnitudes of the low and high gamma oscillations are the greatest. Shading: s.e.m.

(E) Raw (top), low-gamma (30–60 Hz;middle) and high-gamma (70–110 Hz;bottom) filtered traces acquired in joint LFP (black) and PV-cell TEMPO (green) recordings in cortical area V1 of a ketamine-xylazine anesthetized mouse.

(F) Plots of frequency-dependent coherence for the same LFP and TEMPO recordings as in (E), using either a 2-s (left) or a 200-ms (right) temporal window to compute coherence values. The green, teal, and red curves respectively show coherence values between the LFP trace and traces for the ASAP3-labeled PV cells, a temporally shuffled version of the ASAP3 trace, and the red reference fluor. Gray dots at the top of the plots mark frequencies at which the coherence of the ASAP3 and LFP recordings differed significantly from the coherence of the LFP and the reference fluor (rank sum test; p<0.05), highlighting significant coherence in the delta, low- and high-gamma bands, as in (A–D). Shading: s.e.m.

(G–J) Theta-gamma frequency coupling in the voltage dynamics of PV interneurons in the dorsal CA1 hippocampal area of a freely behaving mouse (see Figure 1B for labeling strategy).

(G, H) Mean wavelet spectrograms for the LFP (G) and PV population voltage (H) recordings, plotted as a function of theta-phase over two theta cycles (with theta-phase extracted from the LFP trace at the frequency (7.5 Hz) of peak theta power). In G–J, the convention used for the phase is that 0-deg. refers to the trough of the theta oscillation in the LFP, i.e., the greatest hyperpolarization in the extracellular electric field recording.

(I, J) Mean signal amplitudes at the peak theta frequency (black traces; left axes) and signal magnitudes in the gamma (40–70 Hz) frequency range (olive traces; right axes) for LFP (I) and fluorescence (J) signals. Solid and dashed curves in J are for ASAP3 and reference fluor recordings, respectively. We made similar findings as in G–J in n = 4 mice. Shading: 95% C.I..

(K–N) PV cell-population voltage signals, as reported by ASAP3, revealed a ~100 ms transmembrane depolarization, followed by a prolonged hyperpolarization, during a kainate-induced epileptic seizure (typified by high-frequency LFP dynamics) in the dorsal CA1 hippocampal area of a freely behaving mouse.

(K) Example traces of LFP (black trace; top) and PV membrane voltage (green trace; bottom) signals, illustrating that the appearance of epileptic spikes in the LFP channel correlated with a ~100 ms depolarization of PV interneurons (see also N).

(L) Power spectral density plots for the LFP, recorded either during pre- (dashed curve) or after (solid curve) kainate injection.

(M) Plots of the mean temporal cross-correlation between high-frequency (>50 Hz) power in the LFP and the amplitude (at frequencies <10 Hz) of PV-cell membrane voltage signals (green traces) or reference fluor signals (red traces). Solid traces: Averages over n=21 seizure events (each sampled for 5 s; STAR Methods) that occurred after kainate injection. Dashed curves: Averages over 5-s-intervals taken from the period before kainate injection. Shading in panels M, N: 95% C.I.

(N) Plots of the epileptic, ictal spike-triggered average activity in the LFP and PV cell traces, and in the fluorescence reference channel and temporally shuffled versions of the PV cell traces. Note that PV interneurons depolarized during ictal spikes.

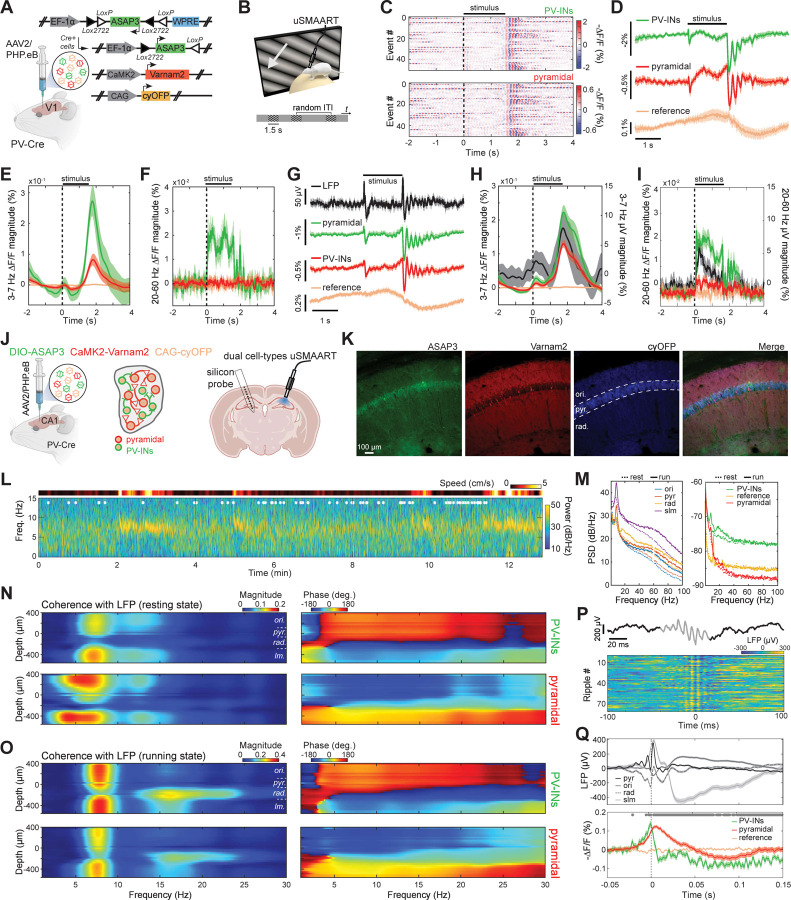

Figure 3: uSMAART tracks the concurrent voltage dynamics of two genetically identified neuron classes in behaving mice.

(A–I) Visual stimulation evoked gamma oscillations in brain area V1 of awake mice during stimulus presentation, followed by 3–7 Hz oscillations after stimulus offset.

(A) Retro-orbital injection of three PHP.eB adeno-associated viruses into PV-Cre mice enabled expression of Cre-dependent ASAP3 in PV interneurons, Varnam2 in pyramidal cells, and cyOFP (a reference fluorophore) in all neuron-types.

(B) Schematic of the visual stimulation paradigm used for dual cell-type voltage-sensing studies. Head-fixed mice viewed a computer monitor placed in front of one eye, as we recorded fluorescence voltage activity in the contralateral primary visual cortex (V1). Drifting grating visual stimuli (each 1.5 s in duration) swept across the monitor. Intervals between stimulation trials were randomized between 2–5 s.

(C) Visual stimuli consistently evoked post-stimulus 3–7 Hz oscillations in ASAP3-labeled PV interneurons (top) and Varnam2-labeled pyramidal (bottom) cells. Each row has data from one of 50 different trials in the same mouse.

(D) Mean time-dependent fluorescence traces, obtained by averaging the signals from all 3 fluors across all 50 trials of (C). Shading in (D–I): 95% C.I.

(E, F) Mean time-dependent fluorescence signal magnitudes in the 3–7 Hz (E) and gamma (30–70 Hz; F) frequency bands for all 3 fluors used in (C, D), computed using wavelet transforms.

(G) Mean time-dependent fluorescence traces from studies in which we reversed the GEVI assignments to PV and pyramidal cells from those of (C), and in which we concurrently performed LFP and TEMPO recordings (averages are over 100 trials).

(H, I) Same as (E, F) but for the studies of G, including the LFP recordings.

(J–Q) We studied the dynamical inter-relationships between excitatory and inhibitory activity in the hippocampus of an active mouse, across different behavioral states.

(J) We performed dual cell-type fluorescence recordings with uSMAART, concurrently with electrophysiological recordings in the contralateral CA1 area (linear silicon probe; 32 recording sites) that allowed us to detect ripple (120–200 Hz) events. The fluorescence labeling strategy using 3 different viruses was the same as in panel (A).

(K) Fluorescence confocal images of a brain slice of a mouse expressing ASAP3 in PV interneurons, Varnam2 in pyramidal cells, and cyOFP in all cell-types. The far right image shows an overlay of the three preceding images, highlighting the different targeting of all three fluorescent proteins.

(L) Top: Plot of mouse speed. Bottom: Time-dependent spectrogram of LFP signals recorded in CA1 stratum pyramidale. White asterisks mark occurrences of ripple events. The LFP exhibited power increases in the theta (5–9 Hz) band during locomotion, whereas ripples occurred only during rest, consistent with past studies.

(M) Power spectral densities for (left) LFP signals recorded across all 4 canonical hippocampal layers (ori.: stratum oriens, pyr.: stratum pyramidale, rad.: stratum radiatum, slm.: stratum lacunosum moleculare) and for (right) the three fluorescent signals from the TEMPO recordings, for periods of rest (dashed curves) or running (solid curves).

(N, O) Plots of the coherence magnitude (left plots) and phase (right plots) between PV (top rows) and pyramidal cell (bottom rows) fluorescence voltage signals and the LFP measured across the 32 recording sites of the silicon probe (plotted as a function of depth relative to the center of stratum pyramidale; tissue layers abbreviated as in M) during periods of resting (N) or running (O). During rest, PV and pyramidal cell voltage dynamics were both coherent with the LFP but with distinct frequency signatures, extending up to the alpha frequency range (~10–15 Hz). During locomotion, both cell-types became highly coherent with the LFP at theta frequencies (~5–9 Hz) in nearly all layers of CA1; however, the LFP signal in stratum radiatum (depth: ~200 μm) had higher coherence with each cell-type in the beta band (~15–30 Hz) than at theta frequencies. Note the sharp changes in coherence phase that occur near the boundaries of different tissue layers.

(P) Top: Example LFP trace showing a hippocampal ripple event (light gray part of the trace) recorded in stratum pyramidale. Bottom: LFP traces shown for 80 different ripple events from the same mouse, temporally aligned to the time on each trial at which the LFP signal was at its minimum.

(Q) Mean time-dependent traces of the LFP signals across all 4 hippocampal layers (top) and fluorescence voltage signals for PV and pyramidal cells (bottom) during ripples, obtained by averaging over 273 ripples. At ripple peak magnitude (vertical dashed line), both pyramidal cells and PV depolarized. PV cells then hyperpolarized more sharply, whereas pyramidal cell voltages more gradually hyperpolarized below baseline voltages. Gray dots at the top of the bottom plot mark times at which the fluorescence changes in the two neuron classes were significantly different (two-tailed signed-rank test; p<0.05). Shaded areas: s.e.m.

Fiber-optic TEMPO captures high-frequency voltage dynamics in behaving animals.

We first examined if uSMAART could sense the high-frequency dynamics of primary visual cortical (V1) neurons of awake head-fixed mice during passive viewing (Figure S2A–F). We virally expressed Varnam1 in pyramidal cells and the reference fluor GFP non-selectively (Figure S2A), and we recorded TEMPO and LFP signals while presenting drifting grating visual stimuli (Figure S2B). In accord with past work,59–61 visually evoked 3–7 Hz oscillations arose in both recordings (Figure S2C–E). Crucially, during visual stimulation the unmixed GEVI but not the reference fluor channel underwent a rise in coherence with the LFP over frequencies up to 30 Hz (Figure S2F), validating that TEMPO had captured cell-type-specific high-frequency dynamics.

Next, we sought to record high-frequency voltage signals from a sparse cell-type in head-fixed but active mice (Figure S2G–L). In hippocampal area CA1, we virally expressed ASAP3 in PV interneurons and the reference fluor mRuby2 non-selectively (Figure S2G). To elicit rest-to-run state changes, we delivered an airpuff to the mouse’s back as it rested (Figure S2H). The airpuff triggered locomotor-evoked ASAP3 and LFP signals in the beta frequency range (15–30 Hz). As in our prior work,7,8 reference fluor signals reflected a slow (~1 Hz) hemodynamic response and the heartbeat (~10–12 Hz) (Figure S2I–K), the absence of which in the ASAP3 traces showed the success of our unmixing strategy. A locomotor-triggered rise in beta-band coherence between the LFP and ASAP3 signals but not with mRuby2 signals confirmed the veracity of the PV cells’ beta-frequency dynamics (Figure S2L).

We next studied CA1 PV cells in freely behaving mice and tracked TEMPO and LFP signals up to ~100 Hz as mice explored an open arena (Figure 1B–I). Like the LFP, TEMPO signals from PV neurons exhibited a clear dependence on the mouse’s locomotor state (Figure 1E,F). During locomotion, these TEMPO signals increased their power (Figure 1H) and coherence with the LFP (Figure 1I) in the theta (5–9 Hz), beta (15–30 Hz) and gamma (30–100 Hz) frequency bands (p<0.05; signed-rank tests; n=6 mice), whereas reference fluorescence signals did not.

Cross-frequency coupling between low- and high-frequency voltage oscillations.

With our newfound ability to capture cell-type specific high-frequency voltage dynamics, we decided to explore whether cross-frequency coupling (CFC), which is associated with a variety of human cognitive processes, could be observed in an individual neuron class. A priori, it was not clear this would be feasible, as CFC might be a collective electrophysiological phenomenon that emerges from the non-stationary contributions of diverse cell-types (Figure 2).62–65

We first studied cortical delta-gamma coupling in anesthetized mice (Figure 2A–F), previously characterized with electrical recordings.66 We recorded TEMPO signals in visual cortical PV cells expressing ASAP3 and found prominent delta rhythms,7 along with high-frequency gamma oscillations during up-states66 (Figure 2A,B). Strikingly, these up-state specific bursts of gamma activity were concentrated in two distinct spectral bands, low (30–60 Hz) and high (70–110 Hz) gamma bands, which were modulated at two different phases of delta (Figure 2C,D). The apex of high gamma activity preceded the peak delta depolarization (–56 ± 14 ms; mean ± s.e.m; p<10–4; n=122 delta oscillations; signed rank test), whereas the apex of low gamma followed it (17 ± 6 ms; p <0.005). Both gamma oscillations nested in the delta rhythm were coherent with the LFP at levels well above chance expectations or those for the reference channel (Figure 2E,F).

We next looked for CFC in freely behaving mice. In mice expressing ASAP3 in hippocampal PV cells, both LFP and TEMPO signals displayed theta-gamma CFC. Notably, the amplitude of PV cell gamma activity peaked at the apex of the LFP theta oscillation, whereas the peak amplitude of LFP gamma activity was phase-shifted relative to the LFP theta oscillation (Figure 2G–J); this fits with reports that PV cells exert a hyperpolarizing influence at the peak of the theta rhythm.67

Bi-phasic dynamics of PV interneurons in an epilepsy model.

We next explored neural voltage dynamics in a disease model. Dysfunctional PV cells are implicated in several neuropsychiatric disorders, including epilepsy,68,69 and activity imbalances between excitatory and inhibitory cells can induce hyperexcitability and seizures.70 Notably, alterations in the membrane voltage dynamics of PV cells can impact their ability to regulate pyramidal cell activity and maintain a balance between excitation and inhibition. To study PV cell voltage dynamics during drug-induced seizures, we utilized uSMAART in mice expressing ASAP3 in PV cells in area CA1 of the dorsal hippocampus.

We induced seizures with kainic acid and jointly recorded LFP and TEMPO signals in freely moving mice (Figure 2K,L). During epileptiform events, PV cell voltage dynamics exhibited two successive characteristic changes. First, they depolarized for ~100 ms, during which the LFP revealed an extracellular hyperpolarization (i.e. depolarized intracellular voltages inducing a local extracellular current sink) (Figure 2M,N). Then, PV cells hyperpolarized for ~1 s as the tissue became hyperexcitable and exhibited ictal spikes, brief high-frequency bursts of activity thought to result from a positive feedback loop between excitatory and inhibitory cells.71 During this second phase of seizure activity, another interneuron-type might limit the PV cell discharge initiated in the first phase. The ictal spikes observed here in PV cells’ dynamics fit with prior recordings72, support the idea that there is a shift between excitatory and inhibitory activity during epileptiform events,73 and show that TEMPO can help reveal how different neuron-types influence epilepsy generation.

Dual neuron-class recordings of visually evoked activity in awake mice.

To validate its capacity for dual cell-type recordings, we assessed if uSMAART can report the concurrent dynamics of glutamatergic and GABAergic neural populations. We first studied awake head-fixed mice expressing cyOFP non-selectively, and Ace-mNeon1 and Varnam1 in pyramidal cells and interneurons, respectively, during passive viewing of visual stimuli (Figure S2M–P). In line with our studies of individual cell-types (Figure S2), these older GEVIs reported stimulus-evoked oscillations in both cell-types in the 3–7 Hz frequency band but not gamma frequencies (Figure S3O,P). To capture excitatory/inhibitory interactions in more detail, we prepared mice expressing ASAP3 in PV cells and Varnam2 in pyramidal cells (Figure 3A). Visual stimuli consistently evoked post-stimulus 3–7 Hz oscillations in PV and pyramidal cells (Figure 3B–E). The superior dynamic range of ASAP3 also enabled the detection of stimulus-evoked increases in gamma (30–70 Hz) activity in PV interneurons (Figure 3F). To verify that the lack of observed gamma activation in pyramidal cells was due to the indicator assignments, rather than a bona fide difference between the two cell-types, we prepared mice in which we reversed the indicator assignments between pyramidal and PV cells and performed joint LFP and TEMPO recordings (Figure 3G-I). In these mice, both cell-types and the LFP exhibited the post-stimulus 3–7 Hz band activation (Figure 3H), and pyramidal cells showed the expected increases in gamma activity during visual stimulation, as did the LFP signals (Figure 3I).

Dual neuron-class recordings in the hippocampus of freely moving mice.

We next studied the relationships between excitatory and inhibitory activity in the hippocampus by performing dual cell-type uSMAART recordings in mice expressing cyOFP non-selectively, ASAP3 in PV cells and Varnam2 in pyramidal cells (Figure 3J–Q). We also recorded electrical dynamics in the contralateral hippocampus with a linear silicon probe, which allowed us to identify well-known physiological signatures of the different hippocampal laminae (Figure S3A,B).74–76 As in prior studies, LFP power in theta (5–9 Hz) frequencies rose across the laminae during locomotion, but hippocampal sharp wave ripples (120–200 Hz) occurred mainly during rest (Figure 3L,M). Locomotor-evoked increases in beta (15–30 Hz) activity were more limited in the LFP recordings to stratum radiatum, whereas the evoked increases in gamma activity (30–100 Hz) occurred across laminae (Figure 3M). Especially in ASAP3-labeled PV cells, locomotion triggered prominent increases in theta and beta activity (Figure 3M), consistent with our prior results (Figure 1).

During rest, the dynamics of both PV and pyramidal cells were coherent with the LFP, but with distinct frequency signatures (Figures 3N and S3C–E). During running, both cell-types had theta-band (5–9 Hz) activity of increased coherence with the LFP in nearly all CA1 layers, as well as beta (15–30 Hz) and gamma (30–70 Hz) dynamics that were more selectively coherent with the LFP in stratum radiatum (Figures 3O and S3C–E).

During ripples (Figure 3P), both PV and pyramidal cells depolarized at ripple onset, consistent with reports that the peak of pyramidal cell activity aligns with the ripple’s envelope peak.77,78 This was followed by a sharp hyperpolarization of PV cells preceding the depolarization peak of the pyramidal cells, and then by a more gradual hyperpolarization of pyramidal cells (Figures 3Q and S3F). The steepness of the PV cell hyperpolarization is suggestive of a time-gating mechanism for precisely releasing synchronized pyramidal cell firing during SWRs, in accord with the idea that inhibitory control by PV interneurons shape the output of pyramidal cells during SWRs.75,79 Future studies should investigate the mechanisms underlying these interactions and explore their consequences for information encoding and memory consolidation. Altogether, these findings show that, when combined with our triple fluor expression strategy, uSMAART can reveal the joint dynamics of two neuron-classes in freely moving mice.

Concurrent uSMAART recordings of two cell-types in two brain areas

An ability to track the concurrent dynamics of multiple identified cell classes across more than one brain area in freely behaving mice would empower mechanistic studies of inter-area oscillatory phenomena. uSMAART provides this capability, in that it allows joint recordings of two cell-types in each of two brain areas (Figure S3G–M). In ketamine-xylazine (KX) anesthetized mice expressing ASAP3 in PV cells and Varnam2 in glutamatergic neurons across cortex (Figure S3H), interneurons and pyramidal cells in area V1 and primary motor cortex (M1) displayed up-and-down state transitions in a delta rhythm with gamma oscillations nested into the up-state (Figure S3I). In line with our prior results (Figure 2), PV cells in V1 and M1 exhibited delta-gamma CFC (Figure S3J–L). We assessed the time delays between the delta oscillations in the two brain areas using the TEMPO signals from either the PV or pyramidal cells (Figure S3M). Using PV cells to estimate the delay, the delta rhythms in M1 had a temporal lead of –103 ± 41 ms (mean ± s.d.) ahead of those in V1. The same calculation for pyramidal cells led to an estimated temporal lead in M1 of –117 ± 35 ms. These results are suggestive of a voltage wave traveling at 10–15 mm·s–1 from anterior to posterior, which prompted us to do follow-up imaging studies (Figure 4).

Figure 4: TEMPO imaging in anesthetized mice reveals traveling neocortical waves in the delta and gamma frequency bands that exhibit cross-frequency coupling.

(A) Schematic of the TEMPO mesoscope. A pair of low-noise light-emitting diodes provides two-color illumination; a corresponding pair of photodiodes monitors their emission powers. The illumination reflects off a dual-band dichroic mirror (70 mm × 100 mm) and is focused onto the specimen by a 0.5 NA macro objective lens providing a 8-mm-diameter maximum field-of-view (FOV) when used in our system. Fluorescence returns through the objective lens and dual-band dichroic mirror. A short-pass dichroic mirror (70 mm × 100 mm) splits the fluorescence into two detection channels. After passing through a bandpass filter, fluorescence in each channel is focused onto a fast sCMOS camera by a tube lens (85 mm effective focal length). Inset: A view from the Allen Brain Atlas, showing the location of the glass cranial windows (dotted black circle; 7–8 mm diameter) used for Figures 4,5,7. Across the full area visible through the cranial window, the cameras acquired images at 130 Hz. In some studies, to increase the imaging speed to 300 Hz, we sampled a region-of-interest on the camera chip that covered the brain areas between the two black horizontal lines. Abbreviations: RSP (retrosplenial cortex), M1 (primary motor cortex), V1 (primary visual cortex), S1 (primary somatosensory cortex), BPF (bandpass filter), BS (beamsplitter), DM (dichroic mirror), LED (light-emitting diode), ND (neutral density), PD (photodiode).

(B) Computer-assisted design mechanical drawing of the mesoscope. Lower inset, magnified view of the large custom fluorescence filter set. Upper inset: Timing protocol for voltage imaging using a single green GEVI plus the mRuby2 reference fluor. Illumination from both LEDs is continuous (bottom two traces). Image acquisition by the two cameras is initiated by an external trigger, ensuring that the image pairs are temporally aligned (top two traces; 800 Mbytes · s–1 data rate per camera).

(C) Top, We retro-orbitally co-injected a pair of AAV2/PHP.eB viruses to co-express red fluorescent mRuby2 and a green fluorescent GEVI, ASAP3. Bottom, One virus expresses mRuby2 via the CAG promoter; the other allows Cre-dependent expression of ASAP3 via the EF-1α promoter. By using Cux2-CreERT2 or PV-Cre mice, we performed voltage-imaging studies of neocortical layer 2/3 pyramidal (L2/3) or PV cells, respectively.

(D) Two examples of traveling voltage waves in the delta frequency band, shown in ASAP3 image sequences (50 ms between images) taken at 130 Hz in ketamine-xylazine-anesthetized Cux2-CreERT2 mice. Images underwent unmixing (Figure S5) to remove hemodynamic changes captured in the mRuby2 channel but were otherwise unfiltered. Brain area boundaries (see (A) inset), are superposed on the last image in each sequence. In each case, a depolarization (denoted by red hues) sweeps across cortex in the anterior to posterior (A-P) direction. Data in (E–R) are also from ketamine-xylazine-anesthetized mice and were acquired at 130 Hz in (D–J) and 300 Hz in (K–R).

(E) Color plot (top) showing the anterior to posterior propagation of the two traveling waves in (D). At each time point (x-axis) and for each A-P coordinate (y-axis), we averaged fluorescence values along the medio-lateral direction. Arrows in 3 different shades of green mark 3 different positions along the A-P axis for which voltage-dependent fluorescence traces are plotted (bottom) in corresponding colors.

(F) Flow maps showing local propagation directions of voltage depolarization for a pair of individual delta waves observed in example Cux2-CreERT2 (top) and PV-Cre (bottom) mice. Flow vectors are all normalized to have the same length.

(G) Distributions of delta wave propagation speed across all delta events seen in two Cux2-CreERT2 (top) and two (PV-Cre) (bottom) mice, computed near the center of area V1 (marked by black dots in (I)), where there was consistent anterior to posterior propagation. Insets: Polar histograms showing distributions of wave propagation direction for the same 4 mice at the center of V1, revealing the approximate alignment of wave propagation with the A-P axis in all 4 mice (n = 313, 320, 405 and 200 delta events in the individual mice).

(H) During the peaks of the delta waves, we found enhanced activity in the gamma (30–60 Hz) frequency band. In two example Cux2-CreERT2 (top) and PV-Cre mice (bottom), the amplitudes of gamma oscillations increased during delta wave depolarizations up to ~4-fold over baseline values in brain areas V1 and RSP and to a lesser extent in other areas.

(I) Maps of peak correlation coefficients, r, for the same mice as in (H), computed for each spatial point by calculating the temporal correlation function between the local fluorescence trace and that at the center of V1 (black dots) and then finding this function’s maximum value.

(J) Maps of peak correlation coefficients, computed as in (I) but using gamma bandpass-filtered fluorescence traces, show that the gamma oscillations were less spatially coherent than the delta waves.

(K) To study gamma activity in greater detail, we acquired a subset of the video data at 300 Hz (K–R) over a more limited FOV (see inset of (A)). Top: Example fluorescence trace of voltage activity at the center of V1 in the same Cux2-CreERT2 mouse as in (H-J), showing ongoing delta waves. Bottom: Gamma-band filtered (35–100 Hz) version of the top trace, revealing increases in gamma-band activity during the peaks of the delta oscillations.

(L) Top: Example fluorescence traces of voltage activity at the center of V1, from each of the two mice in (H-J), temporally aligned to the peak of delta wave depolarization to reveal the consistent waveform of delta activity (n = 260 waves shown per mouse). Bottom: Gamma-band filtered (35–100 Hz) versions of the same traces reveal delta-gamma coupling as in (K).

(M) Mean time-dependent amplitudes of gamma-band (35–100 Hz) activity in the voltage (solid lines) and reference (dashed lines) signals, for each of the 4 mice in (G), computed by averaging over all delta events in each mouse, identified as in (L) and aligned to the peak of the delta oscillation using the wavelet spectrogram. Voltage but not reference channel signals showed increased gamma band activity during the depolarization phase of delta oscillations. Shading: 95% C.I.

(N) Top: Magnified views of two example delta depolarization events at the center of V1 in the same mouse as in (K). Middle: Gamma-filtered (35–100 Hz) versions of the same traces, highlighting gamma events near the end of each delta depolarization. Bottom: Gamma-filtered traces of activity during Event 1, from the color-corresponding locations marked with green-shaded dots in the upper rightmost image of panel (O).

(O) Sequences of gamma-band (35–100 Hz) filtered images (3 ms between successive frames), showing the spatiotemporal dynamics in V1 of the same two delta depolarization events as in (N). Green dots mark the anatomic locations for the voltage traces in the bottom panel of (N). For display purposes only, the images shown were spatially low-pass filtered using a Gaussian filter (156 μm FWHM).

(P, Q) Left panels: Flow maps showing the local wave propagation directions during the same two individual gamma wave events as in (N). As in (F), all flow vectors are normalized to have the same length. Right panels: Histograms showing the distributions of propagation speed across the brain region shown in (O), for the same two gamma events as in the left panels. Unlike delta waves, which traveled along the A-P axis, the gamma waves illustrated here traveled more aligned to the medio-lateral (M-L) axis and had much faster speeds than the accompanying delta waves (compare to (G)). Insets: Polar histograms showing the distributions of propagation direction for the two gamma events, computed across the flow maps of the left panels.

(R) Histograms of propagation speed, aggregated across n = 20 events and all spatial bins (62.5 µm wide) in V1, in the same two mice as in (H-J) (n = 200 and 300 waves, respectively, in the Cux2-CreERT2 and PV-Cre mice). Insets: Polar histograms of the directions of gamma wave propagation, showing that in both L2/3 pyramidal and PV cells the gamma waves traveled approximately in the M-L direction, roughly orthogonal to the propagation directions of their carrier delta waves (E–G).

A TEMPO mesoscope.

As fiber photometry recordings are inherently local and limited to signals arising beneath the fiber tip, we created a complementary instrument, the TEMPO mesoscope (Figures 4A,B and S4A–K), to image the spatiotemporal dynamics of population voltage activity in identified cell-types across the cortical surface of head-restrained mice. The instrument design embodies the TEMPO approach and has 3 main features: (1) a pair of low-noise LEDs for dual-color fluorescence excitation of two GEVIs plus a reference fluor; (2) a low-aberration, high numerical aperture (NA) macro-objective lens to image a field-of-view (FOV) up to 8 mm wide (~50 mm2); and (3) two fluorescence detection pathways with a pair of sCMOS cameras to track GEVI and reference fluor emissions concurrently. We acquired full-frame images on the sCMOS cameras at 130 Hz, above the Nyquist frequency for neural activity in the low-gamma band (30–60 Hz). When we sought to detect higher frequency activity or capture fine temporal snapshots of voltage wave propagation, our cameras allowed imaging at 300 Hz albeit over a narrower FOV (2.7 mm ✕ 8 mm) (Figure 4A, inset). In either imaging mode, in 10 min of operation the system generates about 1 TB of raw data, from which we unmix the voltage signals from biological and instrumentation artifacts.

Frequency-dependent unmixing of voltage and artifact signals.

In our current and prior studies,7–9 unmixing biological and instrumentation noise from the voltage channel is a key part of the TEMPO approach. We initially used independent component analysis to unmix artifacts captured in the reference channel from the voltage channel7 and have since explored the use of linear regression. However, these algorithms are suboptimal in that they lack the flexibility to account for the variable extents to which different artifacts impact the two channels in different frequency bands (Figure S5A). To boost the sensitivity with which TEMPO can detect small-amplitude neural oscillations, we sought an improved unmixing method.

The main biological artifacts reflect hemodynamic processes, which in general are spatially heterogeneous across the field-of-view.56,80 Heartbeat-related signals and changes in tissue’s optical properties due to variations in blood volume and hemoglobin oxygenation have distinct temporal frequency signatures and are generally coherent between the GEVI and reference fluor channels, but with non-zero phase shifts (Figure S5B). Prior methods to unmix hemodynamic contributions to fluorescence signals used either frequency-independent or zero-phase lag transformations that cannot capture frequency-dependent, non-zero phase lags.7,8,13,56,81,82

To address this deficiency, we created a convolutional filtering approach83 to remove biological and instrumentation artifacts from neural voltage signals in a frequency-dependent way (Figure S5C–M, STAR Methods). The algorithm first estimates a linear filter that describes the frequency-dependent manner in which artifacts in the reference channel affect the GEVI channel. It then convolves this filter with the reference channel trace to obtain an estimate of the non-voltage signals in the GEVI channel. Lastly, it subtracts this estimate from the GEVI channel trace to estimate the true voltage signals. This unmixing method outperformed a simple (i.e., frequency independent) linear regression in that it better removed broad- and narrow-band artifacts and did not transfer noise from reference to GEVI channel (Figure S5E–I), which was crucial for detecting high-frequency activity with high sensitivity (Figure S5J). When applied to individual or groups of pixels in the TEMPO video data, our convolutional approach captured the heterogeneity of hemodynamic signals across different blood vessels (Figure S5K,L). Altogether, unlike prior methods, convolutional unmixing preserves high-frequency voltage signals, is applicable to both fiber-optic and imaging TEMPO data, and is an important facet of the toolbox and all analyses presented in this paper.

A transgenic reporter mouse for expressing the TEMPO fluorophores.

To co-express the FRET-opsin voltage sensor AcemNeon12 and the reference fluor mRuby384 in a chosen cell-type, we created a transgenic Cre-dependent reporter mouse line expressly designed for TEMPO studies (Figure S6A–S). We used our published Flp-in approach to make a TIGRE 2.0-based reporter mouse (Figure S6A, STAR Methods).85–87 By enabling dual fluor expression without virus injection, this mouse (termed Ai218) gives TEMPO users a convenient option for uniform indicator labeling in a way that is designed to be highly reproducible across mice.

To evaluate the Ai218 mouse line for TEMPO imaging, we crossed it with PV-Cre or Cux2-CreERT2 driver mice, to express Ace-mNeon1 and mRuby3 in PV or layer 2/3 (L2/3) pyramidal cells, respectively (Figure S6B,C). For optical access to the majority of a cortical hemisphere (~20 brain areas), we created a preparation in which a circular glass window of 7–8 mm diameter is installed in the cranium, allowing us to repeatedly image individual mice over several months.

We first assessed the ability of the TEMPO mesoscope to track voltage rhythms in laminar tissues, where LFP recordings have long been fruitful88,89 and fiber-optic TEMPO was validated (Figures 3, S2, S3).7,8 In KX-anesthetized Cux2-CreERT2 × Ai218 mice (Figure S6B), we found prominent up-down state transitions traveling anterior to posterior (Figure S6D–G). These delta (0.5–4 Hz) waves had a high spatial coherence across most of the imaged brain areas (Figure S6H). But, unlike past electrical measurements66 and our uSMAART studies (Figures 2, S3), we did not see gamma range (30–100 Hz) dynamics (Figure S6I–K), very likely due to the 10-fold poorer subthreshold dynamic range of Ace-mNeon1 as compared to ASAP3 (Figure S1O).

Next, we studied cell-type specific voltage dynamics in awake PV-Cre × Ai218 mice (Figure S6C) as they viewed moving grating visual stimuli (FIgure S6L). Strong 3–7 Hz oscillations arose at visual stimulus offset in V1 but not other brain areas (Figure S6M–R). Visually evoked activity in the gamma range (20–50 Hz) arose in visual cortex during visual stimulation (Figure S6Q,O,S), in line with our uSMAART data (Figures 3, S2). Overall, the Ai218 reporter mice enabled explorations of cell-type specific voltage oscillations up to the low gamma range.

Traveling cortical voltage waves exhibit delta-gamma cross-frequency coupling.

While the Ai218 mouse offers a convenient means of expressing TEMPO fluors, we also sought to benefit from newer GEVIs.1,58 Thus, we created viral tools, based on the PHP.eB serotype90 of adeno-associated viruses (AAVs), for brain-wide expression of GEVI and reference fluors. For instance, to study cortical PV or L2/3 pyramidal cells, we retro-orbitally co-injected into PV-Cre or Cux2-CreERT2 mice, respectively, a pair of AAV2/PHP.eB viruses to drive Cre-dependent expression of ASAP3 and non-selective expression of mRuby2 (Figure 4C, S6T,U).

With this labeling method, we found delta wave depolarizations that swept across cortex in KX-anesthetized mice (Figure 4D–H). These waves traveled anterior-to-posterior (A-P) in excitatory and inhibitory cell-types (Figure 4F,G; n = 200–405 delta events in individual mice, speeds: 12.0 ± 0.4 mm/s for Cux2-CreERT2 and 15.7 ± 0.9 mm/s for PV-Cre mice; angle from the anterior direction: 176 ±1 deg for Cux2-CreERT2 and 164 ± 1 deg. for PV-Cre mice; mean ± s.e.m.). We also found localized increases in gamma (30–60 Hz) activity, which arose during the peaks of delta waves and, unlike delta waves, were confined to a ~2 mm wide area (Figure 4I,J).

To study gamma activity in more detail, we took a subset of the video data at 300 Hz over a more limited field-of-view (Figure 4K–R). This revealed delta-gamma coupling in L2/3 pyramidal and PV cell-types, with gamma arising at the delta wave peaks (Figure 4K–N). We quantified the speed and direction of each individual delta-nested gamma event (Figure 4O–R). Unlike delta waves, which traveled approximately along the A-P axis, gamma waves traveled approximately along the medio-lateral (M-L) axis (72 ± 3 and 88 ± 5 deg. from the A-P axis in Cux2-CreERT2 and PV-Cre mice, respectively; mean ± s.e.m.) and were much faster than the accompanying delta waves (225 ± 28 and 279 ± 20 mm·s–1 in Cux2-CreERT2 and PV-Cre mice, respectively; Figure 4R). This is an important observation, because it shows that coupled oscillations need not co-propagate in the same anatomic direction. Overall, TEMPO imaging was crucial for uncovering the complex spatiotemporal patterns of the nested delta and gamma waves.

Visually evoked sequences of traveling gamma and 3–7 Hz waves in awake mice.

We next studied visual cortical processing in awake mice. Mice with virally-mediated expression of ASAP3 in PV or cortical L2/3 pyramidal cells viewed drifting grating stimuli with the eye contralateral to the cortical hemisphere in which we performed TEMPO imaging (Figure 5, Figure S7A). In these mice, gamma waves (30–60 Hz) consistently arose in the visual cortex during stimulus presentation, followed by waves of ~3–7 Hz frequency at stimulus offset59,61 (Figure 5A–L). Here, both PV and L2/3 pyramidal cells showed significant rises in gamma power in area V1 during visual stimulation over baseline (p<10-9 for each of 2 PV-Cre and p<10-3 for each of 3 Cux2-CreERT2 mice, n=50 trials each, rank sum test, Figure 5H,L). By comparison, reference fluor signals were stationary (p>0.27 in all mice). Visually evoked 3–7 Hz rhythms were previously found in rodents in electrophysiological studies and likely involve thalamocortical interactions akin to those of the human alpha rhythm.59–61 We also observed 3–7 Hz oscillations in areas other than V1, such as in M1, but these were incoherent with the visually evoked waves in V1 (Figure 5I–K).

Figure 5: TEMPO imaging reveals visually evoked sequences of traveling gamma and then 3–7 Hz waves in area V1 of awake head-fixed mice.

(A) For all studies in this figure, we used the same visual stimulation approach as in Figure 3B. We expressed the GEVI (ASAP3) and reference fluor (mRuby2) as in Figure 4C.

(B) Example traces of visual stimulus-evoked voltage activity from a PV-Cre mouse, averaged over primary visual cortex (V1), primary motor cortex (M1) and retrosplenial cortex (RSP). In V1, visual stimuli evoked gamma oscillations (as seen in the gamma-filtered version of the raw trace) and 3–7 Hz oscillations after stimulus offset.

(C) Power spectral densities (PSDs) of voltage activity determined from fluorescence traces that were averaged over V1, M1 or RSP in the same mouse as in (B) across the duration (276 s) of the recording session. Both V1 and M1 exhibited notable oscillations with peak power around 6–7 Hz, and a second-harmonic was also apparent in V1.

(D) Two example sequences of fluorescence images showcasing the spatiotemporal dynamics of visually evoked 3–7-Hz waves in PV cells of area V1 (successive image frames are 75 ms apart). Brain area boundaries, based on the Allen Brain Atlas (Figure 4A inset), are superposed onto the first image in each sequence. Oscillations also arose in M1 but were not time-locked to stimulus presentation (see (F)).

(E, F) Visual stimuli consistently evoked 3–7 Hz and gamma (30–60 Hz) band oscillations in V1 but not M1 in the same mouse as (D). Top plots: Raster color plots showing fluorescence voltage signals, spatially averaged over V1 (E) or over M1 (F), revealing 3–7 Hz oscillations in both areas that were locked to stimulus-offset in V1 but not M1 (50 stimulus trials shown). Bottom plots: Raster plots of gamma-band filtered (30–60 Hz) PV cell voltage activity in V1 (E) and M1 (F), showing that gamma-band activity was evoked during stimulus presentation in V1 but not M1.

(G) Top trace: Mean time-dependent activity trace (mouse 1), obtained by averaging the raw signals of (E) over all 50 trials. Bottom 3 traces: Analogous traces for 3 additional mice, one a PV-Cre mouse and the other two Cux2-CreERT2 mice. Shading: 95% C.I.

(H) Mean time-dependent fluorescence signal magnitudes in the gamma-band (30–60 Hz) for all 4 mice in (G), determined by a wavelet spectrogram as in Figure 4M. All 4 mice showed significant increases in gamma band power during visual stimulation as compared to baseline values (p = 4 × 10-19, 6 × 10-10, 1.5 × 10-16 and 1 × 10-17 in mice 1–4 for the 100-ms-interval after stimulus onset, and 2.6 × 10–18, 3 × 10-16, 6.7 × 10-16 and 7 × 10-15 for the 0.5-s-interval at the middle of the stimulus period, for n = 50 stimulus trials, Wilcoxon sum rank test). Shading: 95% C.I.

(I) Spatial maps of 3–7 Hz power, averaged across the entire recording sessions for mice 1 and 3 of panel (H) (recording durations of 275 s and 266 s, respectively). See (D) for brain area boundaries.

(J) Maps of peak correlation coefficients, r, for the Cux2-CreERT2 and PV-Cre mice of (H), computed for each point in space by calculating the temporal correlation function between the local fluorescence trace and that at the center of V1 (black dots) and then finding this function’s peak value.

(K) Maps of peak correlation coefficients, r, computed as in (J), except that correlations were computed relative to a point in M1 (black dots) not V1. Unlike in (J), in which coherent 3–7-Hz-band activity is largely restricted to V1, here the coherent activity is confined to near M1. Thus, the 3–7-Hz-band oscillations in M1 and V1 appear to be incoherent with each other.

(L) Maps of visually evoked increases in the amplitude of neural activity in the gamma-band (35–60 Hz), computed by wavelet transform as in (H). Both L2/3-pyramidal and PV cell-types underwent increases in gamma activity that were localized to V1.

(M) Two example sequences of fluorescence images from mouse 1 of (H), from videos taken at 300 Hz (3 ms between frames) to reveal the detailed progression of 3–7 Hz waves in V1, for 2 different wave events.

(N, O) Left panels: Flow maps showing the local wave propagation directions (normalized to have the same amplitudes) for the same two 3–7-Hz wave events as in (M). Right panels: Histograms showing the distributions of propagation speed across the region in (M), for the same two events as in the left panels. Insets: Polar histograms of propagation direction for the two 3–7-Hz events, computed across the flow maps of the left panels, showing that the two different events had distinct directions of propagation across V1. The number values on each polar graph refer to the counts in each bin of the histogram.

(P) Histograms of propagation speed, aggregated across spatial bins (62.5 µm wide) in V1 and 30 different 3–7 Hz waves in each of the same two mice as in (L). Insets: Polar histograms of the directions of 3–7 Hz wave propagation direction, showing that while individual waves had a clear direction of propagation (e.g. as in (N, O)), the distribution of these propagation directions across all 3–7 Hz waves was less uniform.

(Q) Sequences of gamma-band (35–100 Hz) filtered images (3 ms between frames), from the same mouse as in (M), showing the spatiotemporal dynamics in V1 of two different gamma oscillation events. For display purposes only, the images shown were spatially low-pass filtered using a Gaussian filter (156 μm FWHM).

(R, S) Left panels: Flow maps showing the local wave propagation directions during the same two gamma events as in (Q). Right panels: Histograms showing the distributions of propagation speed across the region shown in (Q), for the same two gamma events as in the left panels. Insets: Polar histograms showing the distributions of propagation direction for the two gamma events, computed across the flow maps of the left panels.

(T) Histograms of propagation speed, aggregated across all spatial bins (62.5 µm wide) in V1 and 30 gamma waves in each of the same two mice as in (L). For both L2/3 pyramidal and PV cells, modal speeds of gamma waves were higher than those of 3–7 Hz waves, (P). Insets: Polar histograms of gamma wave propagation directions across all observed events, showing that while individual gamma waves had a clear propagation direction (e.g., R, S), the distribution of these propagation directions across all gamma waves was far more isotropic.

To examine if other V1 neuron-types would exhibit similar dynamics, we characterized visually-evoked 3–7 Hz and gamma activity in somatostatin (SST) interneurons, layer 4 (L4) and layer 5 (L5) pyramidal cells (Figure S7A). The 3–7 Hz oscillations arose at visual stimulus offset in all these cell-types, albeit with slightly varying time-courses, but stimulus-evoked gamma activity in L4 pyramids was far weaker than in either L5 or L2/3 pyramids or the two interneuron classes and seemed temporally confined to stimulus onset and offset. These characterizations of sensory-evoked voltage dynamics in 5 V1 neuron-types should help refine models of visual cortical processing.

We next characterized the spatiotemporal patterns of the two types of waves in V1. The 3–7 Hz waves had speeds (108 ± 16 mm·s–1 for PV and 138 ± 16 mm·s–1 for L2/3 cells) and directions relative to the A-P axis (66 ± 8 deg for PV and 63 ± 10 deg for L2/3 cells) that were similar for the two cell-types (30 wave events each; mean ± s.e.m.; Figure 5M–P). Individual gamma waves generally traveled in a well-defined direction (Figure 5R,S), but the distributions of directions across all gamma waves were far more isotropic for both cell-types (Figure 5T). Gamma waves in PV and L2/3 pyramidal cells had much higher modal speeds (178 ± 85 and 145 ± 79 mm·s–1 respectively, mean ± s.e.m., 50 gamma events per cell-type) than 3–7 Hz waves (Figures 5P,T). By comparison, a subset of gamma-band activity arose concomitantly with and propagated similarly to 3–7 Hz wave activity, suggesting that, unlike the faster gamma waves arising in isolation, this slower subset of gamma-band activation was merely harmonics of 3–7 Hz activity (Figure S6X,Y).

Locomotion-evoked theta and beta waves in hippocampus

To apply TEMPO imaging in a subcortical area, we studied the hippocampus during rest-to-run transitions. Past studies found locomotor-associated theta waves in hippocampus, but the use of electrode arrays or multi-site silicon probes led to relatively poor spatial resolution, the interpretative limitations of electric field potential recordings, and a lack of cell-type or neural pathway specificity.74,91

To overcome these limitations, we imaged ASAP3-expressing PV cells across a 3-mm-wide area of dorsal CA1. We took concurrent LFP recordings and directed an airpuff to the mouse’s back to elicit rest-to-run transitions (Figures 6A–F, S2). During running, ASAP3 and LFP signals evidenced a substantial rise in beta band power, accompanied by increased coherence between these two signal-types across most of the optical window (Figures 6B–F, S7B-C). The mRuby2 channel showed neither of these. Strikingly, we discovered that hippocampal beta oscillations are in fact traveling waves; we observed two orthogonal modes of beta wave propagation, in the CA3-to-CA1 and septo-to-temporal directions, with indistinguishable speeds (220 ± 4 vs. 220 ± 6 mm/s; median ± s.e.m; for n=428 and 199 waves propagating in the CA3-CA1 and septo-temporal directions, respectively, p=0.6; rank-sum test; Figure 6G–J).

Figure 6: TEMPO imaging reveals locomotor-evoked bi-directional, theta- and beta-band traveling voltage waves in hippocampal PV interneurons and lateral-septum-projecting pyramidal neurons.

(A) Plot of running speed in an example mouse (top), plus a set of concurrently acquired time traces (bottom 6 traces) illustrating locomotor-evoked hippocampal oscillations in the beta-band (15–30 Hz). Shown are broadband (top 3 traces) and bandpass-filtered versions (bottom 3 (overlaid) traces) of the hippocampal LFP (black traces), fluorescence voltage signals from ASAP3-expressing parvalbumin (PV) cells (green traces), and signals from the mRuby2 reference fluor (red traces). Fluorescence signals are averages across the entire visible portion of the hippocampus. During running, power in the beta band increased in both the LFP and ASAP3 traces but not the mRuby2 trace. Hemodynamic and motion artifacts are visible in the reference trace but not the ASAP3 and LFP traces. Two black arrows on the PV cell voltage trace mark events further characterized in (G) and (H).

(B, C) Power spectral densities (PSDs) for the LFP (B) and fluorescence signals (C), for the same mouse as in (A) during 5 min of continuous recording, during resting (dashed curves) and running (solid curves) conditions. During running (defined as >2 cm/s speed), ASAP3 and LFP signals underwent power increases across the beta band. The mRuby2 signals had prominent spectral peaks arising from the heartbeat and its harmonics. Moreover, the mRuby2 PSD differs between resting and running states across nearly all frequencies, emphasizing the importance of correcting the GEVI signals for the changes in the reference channel.

(D) Plots of the frequency-dependent coherence between the LFP and either the ASAP3 (green curves) or reference fluorescence signals (red curves) from the same mouse as in (A), during resting (dashed curves) and running (solid curves) conditions. ASAP3 but not mRuby2 signals underwent running-evoked increases in coherence with the LFP. The coherence peak near 0 Hz for mRuby2 during running reflects shared motion artifacts affecting the LFP and mRuby2 measurements but not the processed ASAP signals. Also see Figure S7B-C for differences along the CA1–CA3 axis in theta and beta power and coherence.

(E, F) Spatial map of coherence (E) between the LFP and ASAP3 signals during running epochs across the hippocampal surface, averaged across the beta-band (15–25 Hz). The LFP electrode was located in CA1 (upper right portion of the map), which was, as expected, where coherence between the two measurements was highest. However, coherence values were significant across the full field-of-view, unlike values observed during rest (F; top plot) or for the fluorescence reference (F; bottom plot).

(G) Space-time representation of PV voltage activity during beta waves, projected onto the CA3–CA1 (top plot) and septal-temporal (bottom plot) axes. Black arrows mark the same two voltage events marked in (A). The slope of each wave’s representation in the plots gives the reciprocal of that wave’s speed. Based on these slopes, one can see that the waves shown progress from CA3 to CA1 but exhibit almost no propagation in the septal-temporal direction.

(H, I) Movie frames showing beta-frequency voltage waves traveling along the CA3-CA1, (H), or septo-temporal, (I), axes. Each row corresponds to one event; successive frames are 3.3 ms apart. The two events shown in (H) are marked with arrows in (A). Black arrows in the final frame of each plot show the direction of wave propagation, as determined computationally (STAR Methods).

(J) Histogram of waves’ speeds and orientations (inset) for traveling beta waves (756 total events from n=2 mice, STAR Methods). Note that there are two main modes of wave propagation, along two orthogonal axes, the CA3-CA1 axis and the septo-temporal axes of the hippocampus. Beta waves traveled in these two directions with indistinguishable speeds (220 ± 4 mm/s and 220 ± 6 mm/s, median ± s.e.m, for n = 428 and 199 waves propagating along the CA3-CA1 and septo-temporal axes, respectively; p=0.64, rank-sum test).

(K) Plots in the same format as those in (A), but with theta-band (5–9 Hz) filtered traces at bottom, for an experiment in which we used viral retrograde targeting to express ASAP3 in CA1 pyramidal neurons that had axonal projections to the lateral septum (LS).

(L) Plots of coherence between the LFP and fluorescence signals from either LS-projecting pyramidal neurons (green curves) or the red reference fluor (red curves), computed across the entire recording from the same mouse as in K (left) or computed separately for resting and running epochs (right). Note that, unlike for PV-INs, for LS-projecting pyramidal cells the beta-band power is comparatively weak and is unmodulated by running; instead there is strong power in the theta- and gamma-frequency bands that is locomotor-dependent.

(M) Movie frames showing traveling theta-frequency voltage waves for LS-projecting pyramidal (top plot) and PV inhibitory neurons (middle and bottom), as measured with ASAP3. Each row displays an individual theta wave event. Both neuron-types exhibited wave propagation in the CA1 to CA3 direction. Only PV neurons exhibited waves traveling in the CA3 to CA1 direction. Black arrows in the final frames of each plot show the direction of propagation, as computed computationally.

(N) Histograms of speed and direction (inset) for traveling theta waves for LS-projecting pyramidal neurons (left; n=3 mice) and PV inhibitory neurons (right; n=2 mice). Note that only PV cells showed bidirectional wave propagation and that theta waves propagate with different speed between PV (40 ± 2 mm/s and 33 ± 1 mm/s, median ± s.e.m, for n = 930 and 1094 theta waves, for each 2 mice with PV cells targeting, respectively) and LS-projecting cells (90 ± 3 mm/s, 80 ± 3 mm/s and 84 ± 4 mm/s, median ± s.e.m, for n = 508, 465 and 441 theta waves, for each 3 mice with LS-projection targeting, respectively). Moreover, unlike beta waves, the two classes of propagating theta waves traveled with significantly different speeds in PV interneurons (35 ± 2 mm/s and 42 ± 2 mm/s, median ± s.e.m, for n = 777 CA3-to-CA1 and 637 CA1-to-CA3 theta waves, respectively, n=2 mice, p=0.0027).