Abstract

Background:

In a cluster-randomized controlled trial, the “Migrants’ Approached Self-Learning Intervention in HIV/AIDS for Tajiks” (MASLIHAT) reduced intervention participants’ sexual risk behaviour including any condomless sex, condomless sex with female sex workers, and multiple sexual partners. This analysis investigates if observed changes in sexual risk behaviors translated into fewer reported STIs among participants over 12-month follow-up.

Methods:

The MASLIHAT intervention was tested in a cluster-randomized controlled trial with sites assigned to either the MASLIHAT intervention or comparison health education training (TANSIHAT). Participants and network members (n=420) were interviewed at baseline and 3-month intervals for one year to assess HIV/STI sex and drug risk behaviour. We conducted mixed effects robust Poisson regression analyses to test for differences between conditions in self-reported STIs during 12 months of follow-up, and to test the contribution of sexual risk behaviours to STI acquisition. We then tested the mediating effects of sexual behaviours during the first six months following the intervention on STIs reported at the 9 and 12-month follow-up interviews.

Results:

Participants in the MASLIHAT condition were significantly less likely to report an STI during follow-up (IRR=0.27, 95% CI 0.13–0.58). Condomless sex with a non-main (casual or commercial) partner was significantly associated with STI acquisition (IRR=2.30, 95% CI 1.26–4.21). Adjusting for condomless sex with a non-main partner, the effect of MASLIHAT intervention participation was reduced (IRR=0.36, 95% CI 0.16–0.80), signalling possible mediation. Causal mediation analysis indicated that the intervention’s effect on reported STI was partially mediated by reductions among MASLIHAT participants in condomless sex with a non-main partner.

Conclusions:

The MASLIHAT peer-education intervention reduced reported STIs among Tajik labour migrants partly through reduced condomless sex with casual and commercial partners.

Clinical trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, 2021-04-16, NCT04853394.

Keywords: sexually transmitted diseases, drug users, unsafe sex, sex workers, migrant workers

Background

Sexually transmitted Infectious diseases (STIs) have become a rapidly growing public health problem worldwide. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that globally more than a million curable new STD infections occur each day (1). When left untreated, STIs can lead to serious long-term health outcomes and are known to facilitate HIV transmission and acquisition (2, 3). Considerable evidence indicates that people who inject drugs are at high risk for STIs (4). Frequently used as a marker for HIV risk, STIs themselves represent a critical problem that deserves greater attention than they currently receive (3).

This analysis investigates whether a successful HIV risk-reduction intervention for Tajik labor migrants in Moscow who inject drugs reduced their incidence of STIs over a one-year period. As a temporary labor force, Tajik migrants perform many of Moscow’s most difficult and dangerous jobs while living at a bare, subsistence level. As true among migrants globally, these factors contribute to many of these male migrants engaging in risky sex without a condom, with multiple partners, and with female sex workers (FSWs) who have a high prevalence of HIV and other STIs.

To address the need for HIV/STI prevention for this population, we developed and tested the Migrants’ Approached Self-Learning Intervention in HIV/AIDS for Tajiks (MASLIHAT), an intervention model for reducing risky sex, drug, and alcohol, behavior. In a cluster-randomized parallel group controlled trial, the MASLIHAT intervention demonstrated significant effects in reducing risky sex and injection drug behavior among both peer educator participants (PEs) and their network members (5, 6). For our current analysis, we turn our attention to answering a critical intervention outcome question, “Did MASLIHAT’s observed reduction in sexual risk behavior lower the incidence of STIs among this population of male Tajik migrants in Moscow?” To this end, we conducted additional data analyses to test the intervention’s impact on STIs during one-year of follow-up and the mediating effects of specific sexual risk behaviors.

Methods

Study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Illinois Chicago (protocol 2020-0795), PRISMA Research Center in Tajikistan, and the Moscow Nongovernment Organization “Bridge to the future.” All participants provided written informed consent. The MASLIHAT trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT04853394.

Recruitment and Site Assignment

From October 2021 to April 2022, 140 male Tajik migrant workers were recruited from 12 sites in Moscow and trained as peer educators (PEs) (5). Sites were pair-matched and randomly assigned to either the MASLIHAT intervention or the TANSIHAT comparison condition. Prospective PE participants needed to be a male Tajik migrant aged 18 or older, a current or former person who injects drugs (PWID), intend to reside in Moscow for the next 12 months to participate in their assigned intervention and follow-up data collection, and willing to recruit two male PWID to participate as IDU network members (NMs) for baseline and follow-up interviewing. Network members (n=280) had to meet the same eligibility criteria as PEs but also: 1) have injected drugs at least once in the last 30 days; and 2) be someone whom the PE sees at least once a week. A total of 420 male migrant PWIDs participated in the study, 210 in each group. Participants received the equivalent of $20.00 in Russian Rubles for their time and transportation costs in participating in intervention sessions (PEs only) and for being interviewed at baseline and follow-up (both PEs and NMs).

Intervention sessions

MASLIHAT is a small-group, interactive intervention that relies on peer networks to reduce drug, alcohol, and sexual risk behaviors among temporary migrant workers who inject drugs. Migrants in the host country who inject or have previously injected drugs are trained as PEs to promote positive HIV risk-reduction norms and behavioral change through role modeling and by sharing what they learned during MASLIHAT training sessions with their at-risk NMs. The intervention includes five HIV knowledge and skill-building sessions that involve goal setting, role playing, demonstrations, homework, and group discussions. These sessions teach participants techniques for personal HIV and STI risk reduction along with the communication and outreach skills needed to encourage others at risk to also adopt them. The TANSIHAT program echoes MASLIHAT in style and time commitment over 5 sessions without any content related to HIV or STI sexual risk behavior.

Baseline and follow-up interviews

Baseline interviews with PEs and NMs were conducted at the PRISMA office in Moscow or a private location of the participant’s choosing. Following the interview, participants in both conditions were referred to the Moscow HIV Prevention Center to be tested for HIV and hepatitis C virus. Anonymized test results were reported to study staff with only a group number to identify the recruitment site. Follow-up interviews were conducted with PEs and NMs in both groups at 3-month intervals.

Measures

The structured baseline questionnaire collected information on sociodemographic characteristics, and sex and drug-related risk behavior.

Sexually transmitted infections.

At each follow-up participants were asked if they had been diagnosed in the past three months with gonorrhea, syphilis, chlamydia, or any other STI. Responses were coded as yes or no to indicate a STI diagnosed in the past three months.

Sexual risk behavior.

Participants were asked as to how many women they had sexual intercourse with in the past 30 days, and how many of these partners were sex workers. Responses were used to create binary measures of multiple female partners and any female sex worker partner in the past 30 days. Condom use was assessed by asking participants, “How often did you use a condom when having sexual intercourse?” for each of three partner categories: regular female partner in Russia, Moscow FSW, and casual sexual partners not engaged in selling sex. Response categories were “never,” “sometimes,” “often,” or “always.” Responses were coded to create binary measures of any condomless sex (CS), condomless sex with FSWs (CS/FSW), and condomless sex with any non-main (casual or FWS) partner (CS/NM) in the past 3 months.

Analysis

Using follow-up data, we conducted modified mixed effects Poisson regression models predicting any STI, with random intercepts for participant and network cluster, to obtain relative risk estimates for the effects of treatment arm and sexual risk behaviors. Analyses were conducted using Stata (version 18). Time was included as three dummy variables for 6, 9, and 12-month vs. 3-month follow-up, and we tested the interaction of condition and time. Non-significant effects (p>.10) were not included in subsequent models. In separate models, we added multiple partners, sex with FSWs, CS, CS/FSW, and CS/NM to assess the effect of treatment arm when adjusted for these behaviors.

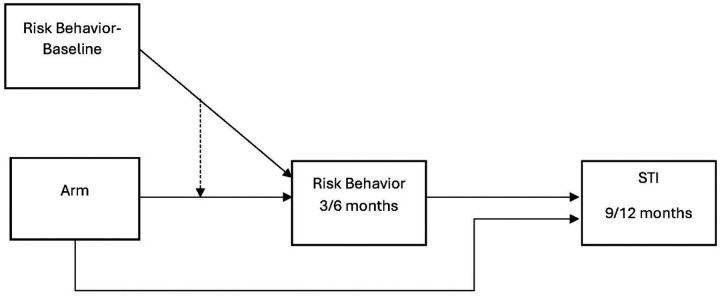

We estimated a causal mediation model (Stata medeff) to compute the indirect effects of treatment arm on STI reported at 9- and 12-month follow-up via sexual risk behaviors reported at 3- and 6-month follow-up (Figure 1). We included the effect of baseline behavior and tested the interaction with treatment arm on the mediating variable. We estimated a mediation model for each risk behavior found to be associated with a STI in regression analyses.

Figure 1.

Mediation model of treatment arm effect on STI at 9 or 12-month follow-up by sexual risk behavior at 3 or 6-month follow-up.

Results

Table 1 reports the demographic characteristics of the sample. All five major regions of Tajikistan are represented in the sample. More participants in the control condition were married (Chi2=5.62, p=0.014). HIV prevalence was 6.8%, among participants who agreed to testing (n=413). When asked at baseline if they had ever been diagnosed with an STI, 41% of the total sample reported yes, 49% reported no, and 10% did not provide an answer. There were no significant differences in STI rates between treatment conditions at baseline (IRR=0.98, p=0.92).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of MASLIHAT trial participants (N=420)

| MASLIHAT | TANSIHAT | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| Age | 29.7 (6.1) | 30.3 (6.3) | ||

| Education | N | % | N | % |

| Primary | 9 | 4.3 | 7 | 3.3 |

| Secondary | 115 | 54.8 | 125 | 59.5 |

| College or Technical | 50 | 23.8 | 55 | 26.2 |

| University (but no degree) | 9 | 4.3 | 5 | 2.4 |

| University Degree | 27 | 12.9 | 18 | 8.6 |

| Employment | ||||

| Construction | 114 | 54.5 | 116 | 55.5 |

| Loading in Bazaar | 41 | 19.6 | 46 | 22.0 |

| Selling in Bazaar | 34 | 16.3 | 22 | 10.5 |

| Food Service in Bazaar | 8 | 3.8 | 11 | 5.3 |

| Other | 12 | 5.7 | 14 | 6.7 |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Not Married | 100 | 47.8 | 76 | 36.4 |

| Married | 18 | 8.6 | 34 | 16.3 |

| Divorced | 91 | 43.5 | 99 | 47.4 |

| Ever any STI | ||||

| No | 102 | 48.6 | 103 | 49.1 |

| Yes | 85 | 40.5 | 88 | 41.9 |

| Don’t know | 20 | 9.5 | 18 | 8.6 |

| Not answered | 3 | 1.4 | 1 | 0.5 |

| HIV Positive / Tested a | 19 / 207 | 9.2 | 9 / 206 | 4.4 |

Tested after baseline interview

MASLIHAT: “Migrants’ Approached Self-Learning Intervention in HIV/AIDS for Tajiks” (intervention group); TANSIHAT Targeted Application of Network and Social Intervention on Health Assistance for Tajiks (control group); SD: standard deviation

Over 90% of participants completed all interview waves. Thirty-seven participants (8.8%) were lost to follow-up at 9 (n=18) and 12 months (n=19). Loss to follow-up was similar across treatment arms and participant type. No new HIV infections were detected at 12-month follow-up. During the 12-month follow-up period 6.7% (n=14) of MASLIHAT participants and their network members and 19.0% (n=40) of TANSIHAT comparison group reported an STI diagnosis.

Regression models

Results of the mixed effects Poisson models testing the effects of treatment arm and sexual risk behavior on STI are shown in Table 2. Participant type, time, and time × arm effects were not significant. Participants in the MASLIHAT condition were significantly less likely to report an STI during follow-up (IRR=0.27, 95% CI 0.13 – 0.58). The marginal probability of STI in the past 3 months over the 12-month follow-up period was 0.03 (95% CI 0.01 – 0.04) in the MASLIHAT condition and 0.08 (95% CI 0.05 – 0.11) in the TANSIHAT condition.

Table 2.

Effects of treatment arm and sexual risk behaviors on STI during 12-month follow-up, modified mixed effects Poisson regressions (N=420, nobs=1610)

| RR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| MASLIHAT vs. TANSIHAT, unadjusted | 0.27 (0.13, 0.58) | 0.001 |

| Adjusted models† | ||

| 1. Any condomless sex | 1.19 (0.67, 2.13) | 0.546 |

| MASLIHAT vs. TANSIHAT | 0.29 (0.14, 0.61) | 0.001 |

| 2. Sex w/ multiple partners | 1.41 (0.73, 2.74) | 0.308 |

| MASLIHAT vs. TANSIHAT | 0.30 (0.14, 0.65) | 0.002 |

| 3. Any sex with sex workers | 1.53 (0.83, 2.82) | 0.173 |

| MASLIHAT vs. TANSIHAT | 0.29 (0.13, 0.64) | 0.002 |

| 4. Number of sex worker partners | 1.22 (0.85, 1.74) | 0.282 |

| MASLIHAT vs. TANSIHAT | 0.30 (0.13, 0.65) | 0.003 |

| 5. Condomless sex with sex workers | 3.30 (1.57, 6.93) | 0.002 |

| MASLIHAT vs. TANSIHAT | 0.37 (0.17, 0.84) | 0.017 |

| 6. Condomless sex with non-main partner | 2.30 (1.26, 4.21) | 0.007 |

| MASLIHAT vs. TANSIHAT | 0.36 (0.16, .80) | 0.013 |

Each sexual risk behavior entered together with treatment arm

MASLIHAT: “Migrants’ Approached Self-Learning Intervention in HIV/AIDS for Tajiks” (intervention group); TANSIHAT Targeted Application of Network and Social Intervention on Health Assistance for Tajiks (control group); CI: confidence interval

Both CS/FSW and CS/NM were significantly associated with STI during follow-up, and the effect of treatment arm was reduced by more than 30% when either variable was added independently to the model. The prevalence of CS/FSW was extremely low in the MASLIHAT condition, with only two participants reporting this behavior during follow-up. Therefore it was impossible to estimate regression models with CS/FSW as an outcome.

Causal Mediation Models

The results of the mediation model for CS/NM are reported in Table 3. As only one MASLIHAT participant at 3 months and one at 12 months reported CS/FSW, the mediation effect for this variable could not be estimated. Therefore, the mediation analysis includes only condomless sex with a non-main partner. In the TANSIHAT group, 61% of men who reported having condomless sex with a non-main partner also reported CS/FSW, as compared to only one out of 6 men (17%) in the MASLIHAT group. The interaction of baseline behavior with treatment arm was not significant and was removed from the model. The indirect effect of treatment arm via condomless sex with a non-main partner was statistically significant and accounted for an estimated 10% of the total effect.

Table 3.

Causal mediation analysis testing effect of intervention arm on sexually transmitted infection via condomless sex with a casual or commercial partner

| Path | Coef. | Robust SE | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS/CC-FU on CS/CC-Baseline | 3.07 | 0.47 | 2.15 | 3.99 | <0.001 |

| CS/CC-FU on Arm | −3.52 | 0.58 | −4.65 | −2.38 | <0.001 |

| STI-FU on CS/CC-FU | 1.10 | 0.40 | 0.31 | 1.88 | 0.006 |

| STI-FU on Arm | −0.99 | 0.42 | −1.80 | −0.17 | 0.017 |

| Effect | Mean | 95% Conf. Int. | |||

| Total Effect | −0.129 | −0.221 | −0.038 | ||

| Average Mediation | −0.013 | −0.025 | −0.004 | ||

| Average Direct Effect | −0.116 | −0.204 | −0.024 | ||

| % of Total Effect mediated | 0.103 | 0.059 | 0.306 | ||

STI: Sexually transmitted infection; CS/CC: Condomless sex with casual or commercial partner; FU: Follow-up; Arm: MASLIHAT (treatment) vs. TANSIHAT (control); Coef: coefficient (log odds); CI: confidence interval

Discussion

The MASLIHAT intervention for HIV prevention is a network-based peer education intervention, tailored for Tajik migrants who inject drugs while working in Russia. In previous analyses of this cluster-randomized controlled trial, we found significant reductions in self-reported sexual risk behaviors associated with the intervention including sexual activity with female sex workers and condomless sex. Our findings indicate that the reported changes in sexual activity, specifically engaging in condomless sex with sex workers and casual partners, contributed to reduced STI incidence among both MASLIHAT PEs and NMs during one year of follow-up.

Risk for HIV and for STIs are behaviourally entwined as they share the same set of sexual practices that can lead to infection. Concern exists that the increasing successful use of medical protection and treatment for HIV will accelerate risky sexual behavior and greatly increase STI rates globally due to the psychosocial effects of risk compensation as personal fear of contracting HIV diminishes (3, 7). Yet, results of research investigating this possibility are inconclusive (8). Meanwhile the data in our study showed a decline in STI rates over a 12-month period, an outcome that suggests that MASLIHAT’s positive effects continue long after its formal training sessions end.

Limitations.

The STI outcomes and sexual risk behaviors in this study were self-reported. Self-reports cannot be verified and may be subject to the demand characteristics of the intervention or to social desirability bias. Another limitation is that most STDs are asymptomatic making them difficult to detect. Consequently, the rates of STI incidence reported by our study participants may under-report actual infection. MASLIHAT participants may be more sensitized to the disclosure of sexual risk. On the other hand, MASLIHAT participants who engaged in sexual risk behavior may be more sensitized to the need for STI testing. Nevertheless, the similarity of effects among direct participants and their network members lends support to the validity of the findings. Our sample is composed entirely of migrant men who inject drugs while in Moscow and does not represent the sexual behavior of their Tajik counterparts who do not. In addition, our sample did not include women.

Conclusions

The MASLIHAT peer-education intervention proved effective during a 12-month clinical trial in reducing STIs among Tajik labour migrant participants and their network members who inject drugs. As such, it responds to WHO’s call for HIV/STI interventions and research findings that help to inform and meet the goals of its widely adopted, “Global health sector strategies on, HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections for the period 2022–2030.” MASLIHAT’s protective effects also may help to inhibit possible forward transmission of STIs among intervention participants to their wives and/or other sexual partners. If culturally adapted for other ethnicities, the intervention holds potential promise in reducing STIs among male migrant labour populations who inject drugs in other destination countries.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the significant contributions of Dr. Mahbatsho Bahromov, founder of the PRISMA Research Center, that made this project possible. He passed away in February 2024. We thank the Tajik Diaspora Union, the Volunteer Doctors Association, and Moscow HIV Prevention Center for their assistance and the study’s participants and members of the MASLIHAT staff for making this research possible.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health (USA) under Award Number R01DA050464 and by a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science, NIH, through grant UL1TR002003. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

List of abbreviations

- CS

condomless sex

- CS/FSW

condomless sex with female sex workers

- FSW

female sex worker

- HIV

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- MASLIHAT

Migrants’ Approached Self-Learning Intervention in HIV/AIDS for Tajiks

- NM

Network member

- PE

Peer educator

- PWID

People who inject drugs

- STI

Sexually transmitted infection

- TANSIHAT

Targeted Application of Network and Social Intervention on Health Assistance for Tajiks

Funding Statement

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health (USA) under Award Number R01DA050464 and by a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science, NIH, through grant UL1TR002003. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Illinois Chicago (protocol 2020-0795), PRISMA Research Center in Tajikistan, and the Moscow Nongovernment Organization “Bridge to the future.” All participants provided written informed consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the Open Science Framework repository [DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/7G3YH https://osf.io/ws5mp/].

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO). Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) 2024. [Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sexually-transmitted-infections-(stis). Accessed 7 Aug 2024.

- 2.Fleming DT, Wasserheit JN. From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: The contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sex Transm Infect. 1999;75(1):3–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen MS, Council OD, Chen JS. Sexually transmitted infections and HIV in the era of antiretroviral treatment and prevention: the biologic basis for epidemiologic synergy. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22(S6):e25355. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization (WHO). Recommended package of interventions for HIV, viral hepatitis and STI prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for people who inject drugs: Policy brief. 2023. Available from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240071858.

- 5.Mackesy-Amiti ME, Bahromov M, Levy JA, Jonbekov J, Luc CM. Changes in risk behaviour following a network peer education intervention for HIV prevention among male Tajik migrants who inject drugs in Moscow: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. J Int AIDS Soc. 2024;27(S3):e26310. doi: 10.1002/jia2.26310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mackesy-Amiti ME, Levy JA, Bahromov M, Jonbekov J, Luc CM. HIV and hepatitis C risk among Tajik migrant workers who inject drugs in Moscow. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(11):5937. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20115937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan X, Jia Z, Zhang B. Evaluating the risk compensation of HIV/AIDS prevention measures. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22(4):447–8. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00151-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eaton LA, Kalichman SC. Risk compensation in HIV prevention: Implications for vaccines, microbicides, and other biomedical HIV prevention technologies. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2007;4(4):165–72. doi: 10.1007/s11904-007-0024-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the Open Science Framework repository [DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/7G3YH https://osf.io/ws5mp/].