Introduction

The specific dietary needs of the cat have been established and foods have been developed that provide good nutrition for all life stages as well as for many medical conditions. Less attention has been given to addressing how meeting the cat’s natural feeding behaviors and environmental needs can positively impact its physical and emotional wellbeing. We have a great deal of information about what to feed cats, but relatively little discussion of and emphasis on managing the feeding process to improve this species’ quality of life and ability to cope with the lifestyle we have chosen for it. 1

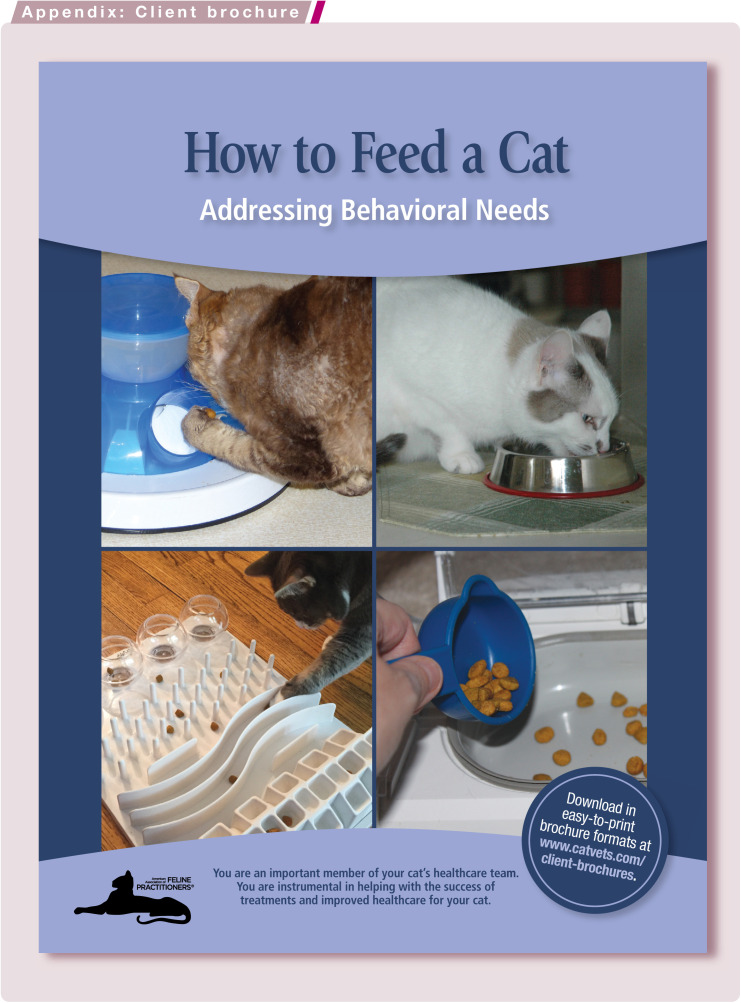

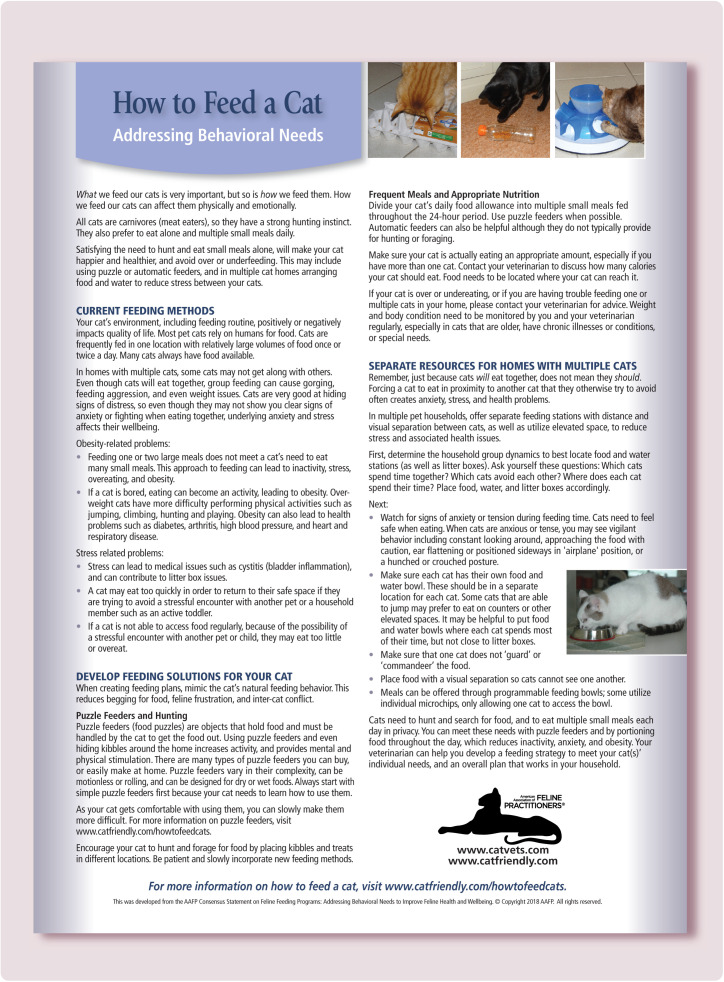

This American Association of Feline Practitioners (AAFP) Consensus Statement, ‘Feline feeding programs: addressing behavioral needs to improve feline health and wellbeing’, explores the medical, social and emotional problems that can result from the manner in which most cats are currently fed. It provides strategies to allow normal feline feeding behaviors to occur in the home environment,2,3 thus alleviating or preventing stress-related and/or overeating issues.3-6 These strategies include offering frequent small meals using appropriate puzzle feeders, forage feeding, and multiple food and water stations.

Normal feline feeding behavior

All felids are meat eaters, or strict carnivores, and many domestic cats have a strong hunting instinct.7,8 Cats are solitary predators that consume small prey, and they prefer to eat often and alone. Their prey is of low caloric density, necessitating several kills per day (for which they expend large amounts of energy) to meet their basic nutritional requirements.7,8

Impact of cat lifestyle

The indoor cat

Many pet cats worldwide live indoors, but a solely indoor lifestyle can prevent normal behaviors such as hunting and foraging, which negatively impacts a cat’s welfare.4,9,10 In fact, it has been documented that behavioral problems are more common in cats without access to the outdoors. 4

Most indoor cats need to rely on humans for food provision. They are often fed with other cats in one location and given relatively large volumes of food once or twice daily or ad libitum, without consideration of each cat’s individual energy requirements.

The outdoor cat

Cats with outdoor access are usually fed similarly to indoor cats, eating readily available, highly palatable food, often rapidly, and have little need to forage and hunt. This leaves a void in the ‘time budget’ of cats with outdoor access as well as indoor-only cats. Cats can naturally spend half of every 24 h looking for and obtaining food. 2

The multi-cat household

Cats engage in and maintain social relationships with other cats and will even live in large colonies (typically of related cats) when resources are sufficient. 3 However, within the group some cats may choose to associate with certain members and actively avoid others. 3 Related cats are often, but not always, bonded.

In multi-cat households, cats usually do not share their provided space equally. 11 In these homes, cats may be restricted or self-restrict to certain areas or rooms because of their social relationships, personalities and genetics. Some cats go into all rooms and others have rather small spaces in which they feel comfortable and safe.

As mentioned, cats naturally prefer to eat small, frequent meals alone, thus competition for food can cause conflict and pre-feeding aggression.6,12,13 An important point to note is that cats may not show overt signs of tension or stress, which therefore often go unrecognized by owners.

Problems associated with current feeding methods

Obesity-related problems

The typical household practice of feeding one or two large meals at a single feeding station does not address the domestic cat’s need for both eating alone and eating multiple small meals a day.6,14 This approach to feeding can lead to inactivity and even distress, often resulting in overconsumption and obesity. 15

Modern pet food is highly palatable and easy to eat rapidly, due to its small chunks and kibble formulation. These factors can contribute to overeating and weight gain.

If a cat is bored and has little to do, eating can in itself become an activity, even in cats with outdoor access, 4 leading to excessive calorie intake and obesity. 15 Overweight cats have more difficulty performing physical activities such as jumping, climbing, hunting and playing, exacerbating the obesity problem.

An indoor lifestyle in general has been demonstrated to increase the risk of obesity and associated diseases.16,17

Stress-related problems

Unsuccessful stress-related coping behaviors, especially in multi-cat households, such as lengthy intervals between litter box uses, may result in or aggravate illnesses such as cystitis.1,5,18,19

In an attempt to avoid a stressful encounter with another pet or even a household member such as an active toddler, a cat may develop the habit of gorging, with subsequent vomiting,13,20 in order to quickly return to a safe place.

Other cats may have inadequate nutritional intake due to lack of access to food.1,5

Solutions: how to develop appropriate feeding programs

The goal of a feeding program should be to mimic the cat’s natural feeding behavior. Simulating normal feeding behavior in cats diminishes begging for food, feline frustration and inter-cat conflict. It also helps reduce relinquishment and enhances the bond between cats and their owners. 14

Consider the following recommendations when developing the cat’s program.

Puzzle feeders and foraging

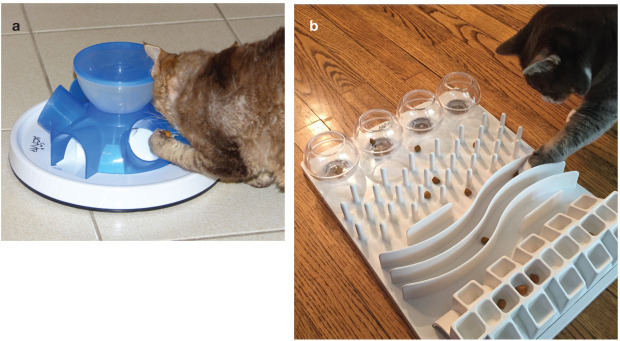

Puzzle feeders (also called food puzzles) are objects that hold food and must be manipulated by the cat to release the food. Using puzzle feeders and hiding kibbles around the home increases activity, provides mental and physical stimulation,10,14 and improves weight management without contributing to patient and owner distress.1,21 A large range of puzzle feeders are available commercially (Figure 1), or they can be made at home easily and inexpensively (Figure 2). Puzzle feeders vary in their complexity, can be stationary or rolling, and can be designed for dry or wet foods. Some types require more effort than others on the part of the cat to obtain food, either by manipulation of the feeder or by the use of paws or tongue to reach the food. Usually simple, easily manipulated puzzle feeders should be introduced first. More information on the different types of puzzle feeders, and how to introduce them into the household feeding program, is available at www.foodpuzzlesforcats.com.

Figure 1.

Two commercial puzzle feeders. These simple (a) and more complex (b) food puzzles are teaching kibble manipulation and retrieval using the paws, mouth and tongue. Courtesy of (a) Ilona Rodan and (b) Heather O’Steen

Figure 2.

Two homemade puzzle feeders. (a) Like the feeders in Figure 1, this simple food puzzle also teaches food manipulation. (b) This dry food puzzle feeder encourages play and predation. Courtesy of (a) Ilona Rodan and (b) Elizabeth Rowe

Placing food portions in different or new locations, including making use of elevated space when the cat’s physical status allows, can also enable cats to forage and engage their senses in searching for food.

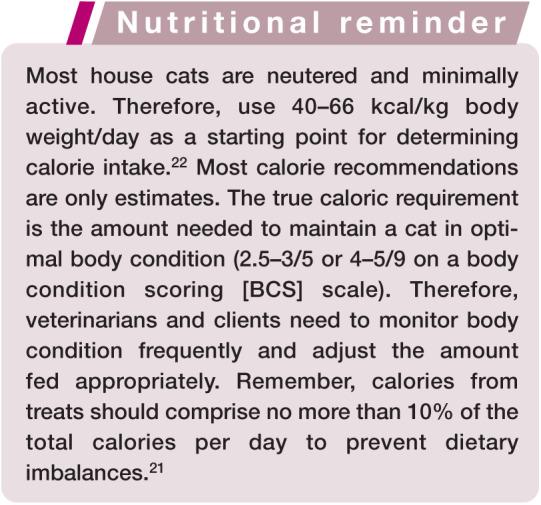

Frequent meals and appropriate nutrition

The cat’s daily food allowance should be split into multiple small meals and fed throughout the 24 h period, using puzzle feeders when possible. Automatic feeders can also be helpful, although they do not typically provide for foraging and predation. Owners must ensure that their cat is actually eating an appropriate amount and that food placement is such that the cat is able to procure it. Weight and body condition need to be monitored regularly, especially in cats that are aged or debilitated, or have chronic illnesses or particular needs. It is imperative that the veterinary team also educates owners on how to evaluate their cat’s behavior for signs of illness, evidence of stress from inter-cat tension, food bowl guarding or other problems, both in general and associated with the feeding program. 13

Veterinarians should counsel their clients as to how many calories their cat should eat on a daily basis (see ‘Nutritional reminder’ box) and help determine the best way to measure food portions, either by using a digital gram kitchen scale or by volume using a measuring cup. (Note that some owners have been found to be inaccurate when measuring portions using the cup method. 23 ) Food can be measured when filling feeding stations and then measured again 24 h later to determine how much has been eaten.

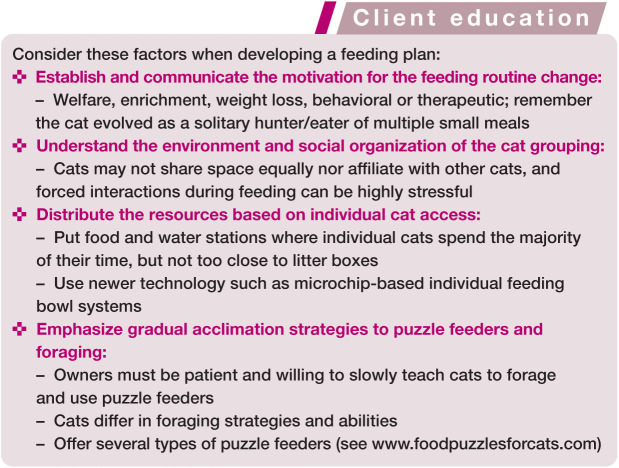

Separate resource areas for multi-cat households

Just because cats will eat together does not mean that they would not greatly benefit from separate feeding areas. Forcing a cat to eat in proximity to another cat that it otherwise chooses to avoid creates anxiety, stress and health problems.

Therefore, the first task is to determine the household group dynamics to help direct where feeding and water stations (as well as litter box resources) should be located. These questions should be answered by the owner: Which cats spend time together? Which cats avoid each other? Where does each cat spend its time?

Feeding plans should include multiple feeding stations that are visually separated.6,12 Feeding station placement should consider the agility of each cat (to utilize elevated spaces such as shelves or tables) and dietary needs. Meals can be offered through programmable feeders, some of which utilize individual microchips. Feeding areas can also be separated by baby gates, or by using size-limiting entrances to access the food.5,24 Cats should be fed in locations where they feel safe.6,12 Additionally, feeding stations should not be close to litter boxes.6,12

Summary Points

As part of providing optimal healthcare to our feline patients, it is crucial to share with our clients the importance of optimizing not only what to feed, but also how to feed.

Engaging the cat’s predatory, foraging and play behaviors to meet its environmental needs with puzzle feeders and multiple small meals reduces inactivity, anxiety and obesity.

In multi-cat households, offering separate feeding stations with adequate distance and visual separation between stations, and taking advantage of elevated space, can reduce stress and associated health issues.

Helping clients develop feeding strategies to meet each cat’s individual needs, as well as an overall plan that works in their own households, should be an important part of nutritional counseling at each veterinary visit.

Acknowledgments

The AAFP Panel gratefully acknowledges the contributions of Dr Kim Farina, for her veterinary and literary consultation and skills in the preparation of the Consensus Statement.

Appendix

The client brochure may be downloaded from catvets.com/client-brochures and is also available as supplementary material at jfms.com. DOI: 10.1177/1098612X18791877

Footnotes

Dr Ilona Rodan is an independent consultant for the Advisory Council for Royal Canin. Dr Beth Hamper is an independent consultant for Freshpet. The other authors do not have any potential conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Dantas LMS, Delgado MM, Johnson I, et al. Food puzzles for cats: feeding for physical and emotional wellbeing. J Feline Med Surg 2016; 18: 723-732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fitzgerald BM, Turner DC. Hunting behaviour of domestic cats and their impact on prey populations. In: Turner DC, Bateson P. (eds). The domestic cat: the biology of its behaviour. 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2000, pp 151-175. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Turner DC. Social organization and behavioural ecology of free-ranging domestic cats. In: Turner DC, Bateson P. (eds). The domestic cat: the biology of its behavior. 3rd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2014, pp 64-70. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Amat M, de la Torre JLR, Fatjo J, et al. Potential risk factors associated with feline behaviour problems. Appl Anim Behav Sci 2009; 121: 134-139. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Buffington CT, Westropp JL, Chew DJ. From FUS to Pandora syndrome: where are we, how did we get here, and where to now? J Feline Med Surg 2014; 16: 385-394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ellis S, Rodan I, Carney HC, et al. AAFP and ISFM feline environmental needs guidelines. J Feline Med Surg 2013; 15: 219-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bradshaw JWS. The evolutionary basis for the feeding behavior of domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) and cats (Felis catus). J Nutr 2006; 136 Suppl: 1927S-2931S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Plantinga EA, Bosch G, Hendriks WH. Estimation of the dietary nutrient profile of free-roaming feral cats: possible implications for nutrition of domestic cats. Br J Nutr 2011; 106: S35-S48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kasanen IHE, Sorensen DB, Forkman B, et al. Ethics of feeding: the omnivore dilemma. Anim Welf 2010; 19: 37-44. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stella JL, Croney CC. Environmental aspects of domestic cat care and management: implications for cat welfare. Sci World J 2016; 2016: 6296315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bernstein P, Strack M. A game of cat and house: spatial patterns and behavior of 14 domestic cats (Felis catus) in the home. Anthrozoos 1996; 11: 25-39. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Desforges EJ, Moesta A, Farnworth MJ. Effect of a shelf-furnished screen on space utilisation and social behaviour of indoor group-housed cats (Felis silvestris catus). Appl Anim Behav Sci 2016; 178: 60-68. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Amat M, Camps T, Manteca X. Stress in owned cats: behavioural changes and welfare implications. J Feline Med Surg 2016; 18: 577-586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ellis SL. Environmental enrichment: practical strategies for improving feline welfare. J Feline Med Surg 2009; 11: 901-912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McMillan F. Stress-induced and emotional eating in animals: a review of the experimental evidence and implications for companion animal obesity. J Vet Behav 2013; 8: 376-385. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rowe E, Browne W, Casey R, et al. Risk factors identified for owner-reported feline obesity at around one year of age: dry diet and indoor lifestyle. Prev Vet Med 2015; 121: 273-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Slingerland LI, Fazilova VV, Plantinga EA, et al. Indoor confinement and physical inactivity rather than the proportion of dry food are risk factors in the development of feline type 2 diabetes mellitus. Vet J 2009; 179: 247-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stella JL, Lord LK, Buffington CT. Sickness behaviors in response to unusual external events in healthy cats and cats with feline interstitial cystitis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2011; 238: 67-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Koolhaas JM, Korte SM, De Boer SF, et al. Coping styles in animals: current status in behavior and stress-physiology. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 1999; 23: 925-935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stella JL, Buffington CAT. Individual and environmental effects on health and welfare. In: Turner DC, Bateson P. (eds). The domestic cat: the biology of its behavior. 3rd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2014, pp 186-200. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wrigglesworth D, Hackett R, Holmes K, et al. Using environmental and feeding enrichment to facilitate feline weight loss. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl) 2005; 89: 427. [Google Scholar]

- 22. National Research Council (US). Ad Hoc Committee on Dog and Cat Nutrition. Nutrient requirements of dogs and cats. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2006, pp 28-48. [Google Scholar]

- 23. German AJ, Holden SL, Mason SL, et al. Imprecision when using measuring cups to weigh out extruded dry kibbled food. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl) 2011; 95: 368-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ellis S, Rowe E. Five-a-Day Felix. A report into improving the health and welfare of the UK’s domestic cats. http://bit.ly/Five-A-DayFelix (2017, accessed January 15, 2018).