Abstract

This cross-sectional study examines the association of availability of primary care practitioners and level of socioeconomic vulnerability with risk of pharmacy deserts in regions of the US.

Introduction

Retail pharmacy chains have been closing thousands of locations throughout the US, possibly playing a role in health care gaps.1 Similar to the concept of food deserts, areas in which medications are harder to obtain have been deemed pharmacy deserts.2 In this study, we defined how pharmacy deserts may disproportionately affect individuals living in US regions with low practitioner supply and high social vulnerability.

Methods

Data through 2020 on communities located 10 or more miles from the nearest retail pharmacy (ie, pharmacy deserts) were sourced from TelePharm Map.3 Counties were stratified as high pharmacy desert density if the number of pharmacy deserts per 1000 inhabitants was in the 80th percentile or higher. Social vulnerability index (SVI) and health care practitioner data were obtained from Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry4 and Area Health Resources File,5 respectively. Primary care practitioner (PCP; including family medicine, general practice, general internal medicine, general pediatrics physicians) density was calculated as the number of PCP per 10 000 inhabitants. In accordance with the Common Rule, this cross-sectional study was exempt from ethics review and informed consent requirement because only public county-level data were used. We followed the STROBE reporting guideline.

Wilcoxon rank sum test, χ2 test, or logistic regression analysis were used to identify associations between variables of interest. Two-sided P < .05 was considered statistical significance. Data analysis was performed from January to March 2024 using R 4.3.2 (R Core Team).

Results

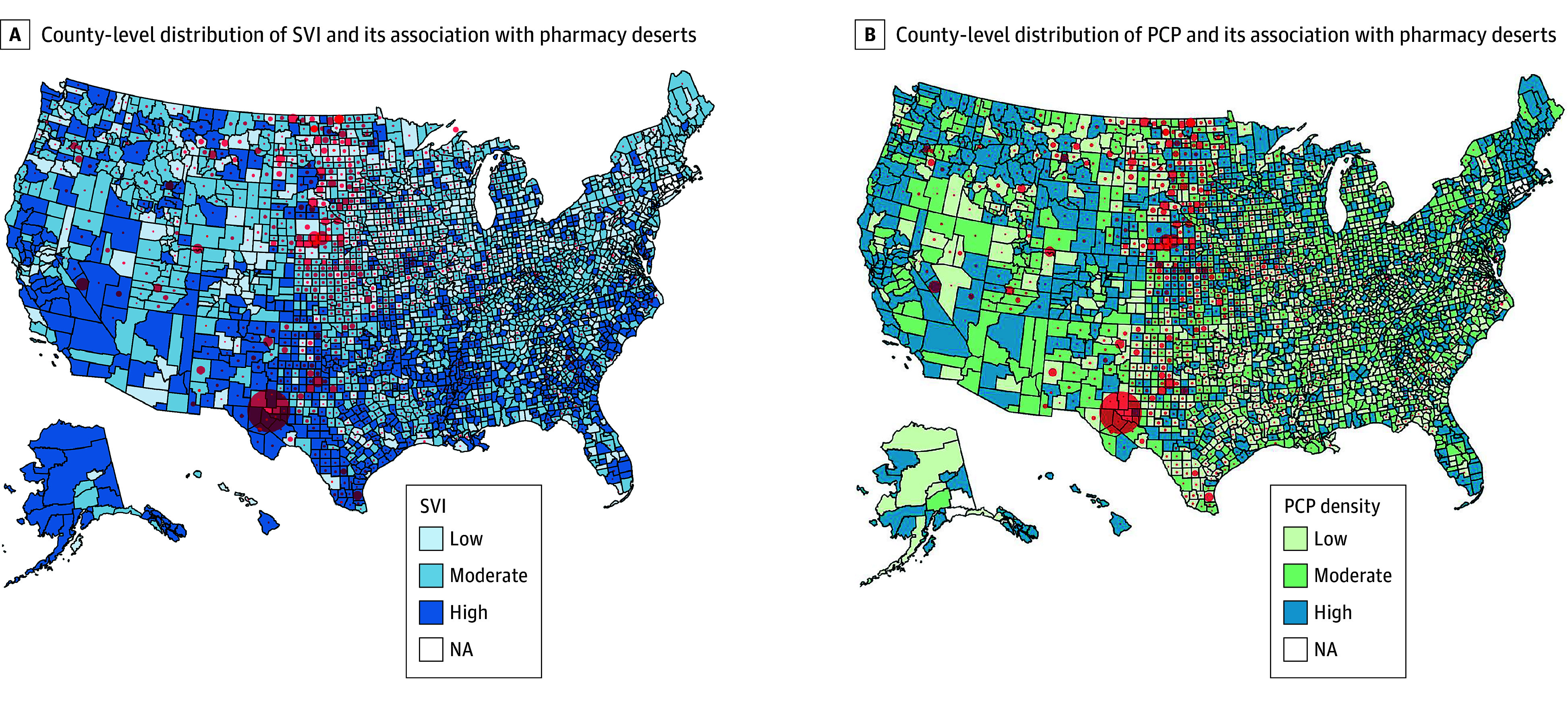

Among 3143 counties, 1447 (46%) had at least 1 pharmacy desert, of which 818 (56.5%) were categorized as having low and 629 (43.5%) as having high pharmacy desert density, respectively (Table). Counties with a high vs low pharmacy desert density had a higher SVI (high SVI: 238 [38.0%] vs 294 [36.0%]; low SVI: 194 [31.0%] vs 246 [30.0%]; P = .006) (Figure). Areas with a high pharmacy desert density had lower median [IQR] PCP density (3.65 [1.12-5.96]) vs regions with low (5.01 [3.21-7.53]) or no pharmacy (4.86 [3.10-7.40) desert density (P < .001). On multivariate analysis, after controlling for age and sex, both high SVI (odds ratio [OR], 1.35; 95% CI, 1.07-1.70; P = .01) and low PCP density (OR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.80-2.86; P < .001) were associated with a higher likelihood for a county to have a high pharmacy desert density.

Table. County Characteristics Stratified by County-Level Pharmacy Desert Density.

| Characteristic | Median (IQR) | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N = 3143) | Pharmacy desert density | ||||

| High (n = 629) | Low (n = 818) | No pharmacy deserts (n = 1696) | |||

| SVI, No. (%) | |||||

| Low | 1037 (33) | 194 (31) | 246 (30) | 597 (35) | .006 |

| Moderate | 1048 (33) | 197 (31) | 278 (34) | 573 (34) | |

| High | 1058 (34) | 238 (38) | 294 (36) | 526 (31) | |

| PCP density | 4.66 (2.79-7.20) | 3.65 (1.12-5.96) | 5.01 (3.21-7.53) | 4.86 (3.10-7.40) | <.001 |

| Total population | 25 698 (10 831-67 945) | 6137 (3258-10 876) | 33 506 (18 011-65 970) | 38 812 (16 756-112 427) | <.001 |

| Sex | |||||

| Female, % | 50.2 (48.9-51.5) | 49.6 (47.9-51.3) | 50.1 (48.8-51.3) | 50.4 (49.4-51.6) | <.001 |

| Male, % | 49.8 (48.5- 51.1) | 50.4 (48.7- 52.1) | 49.9 (48.7-51.2) | 49.6 (48.4-50.6) | <.001 |

| Age >65 y, % | 19.8 (17.2-22.6) | 22.6 (19.7-25.8) | 19.3 (16.8-21.7) | 19.2 (16.9-21.8) | <.001 |

Abbreviation: PCP, primary care practitioner (including family medicine, general practice, general internal medicine, general pediatrics physicians); SVI, Social Vulnerability Index.

Figure. County-Level Distribution of Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) and Primary Care Practitioner (PCP) and Their Association With Pharmacy Deserts.

The size of the red circles represents the number of pharmacy deserts per 1000 inhabitants. The biggest circle is about 10 pharmacy deserts per 1000 inhabitants, while the smallest is about 1 per 1000 inhabitants. NA indicates not available.

Discussion

In the US, CVS announced plans to close 900 stores in the next 3 years, and Rite Aid filed for bankruptcy.1 As pharmacies close, more and more individuals are left without easy access to medications, with disproportionate consequences for certain communities. Patients in higher SVI counties with a lower PCP density had a 30% to 40% higher likelihood to reside in regions with pharmacy deserts. These findings highlight how disparities compound to create barriers to access basic health care.

There is an association between SVI and number of chronic conditions. For example, diabetes and hypertension tend to be more prevalent among Black patients living in rural areas.6 Poor access to pharmacies is often associated with lower medication adherence. Patients in socially vulnerable communities may lack the means to travel to other pharmacies or may have limited access to broadband internet to find telepharmacy options. Furthermore, pharmacies often offer diagnostic, preventive, and emergency services. As high pharmacy desert density counties also have a lower PCP density, patients residing in these regions face increased barriers to accessing primary health care needs.

In future studies, weighted regression and inverse probability weighting could provide more insights into disparities in health care access. While the cross-sectional design limited the ability to draw causal inferences, the study demonstrated that high SVI and low PCP density were associated with concomitant risk of a pharmacy desert. This finding suggests that people already at highest risk of being neglected by the health care system are most likely to be affected by pharmacy closures. More efforts are needed to maintain access to pharmacies in underserved communities.

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Nayak A. How pharmacy deserts are putting the health of Black and Latino Americans at risk. November 10, 2023. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.statnews.com/2023/11/10/cvs-rite-aid-walgreens-pharmacy-deserts/

- 2.Guadamuz JS, Wilder JR, Mouslim MC, Zenk SN, Alexander GC, Qato DM. Fewer pharmacies in Black and Hispanic/Latino neighborhoods compared with White or diverse neighborhoods, 2007-15. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(5):802-811. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.TelePharm, Outcomes Operating Inc. State pharmacy desert map. Accessed February 22, 2024. https://maps.telepharm.com/telepharm/maps/116831/state-pharmacy-desert-map?submissionGuid=7900514c-71b6-4505-8558-4de84e252609#

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (CDC/ATSDR ). CDC/ATSDR Social vulnerability index. Accessed February 22, 2024. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/index.html

- 5.Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Workforce, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis . Area Health Resources File. Accessed February 22, 2024. https://data.hrsa.gov/data/download?data=AHRF#AHRF

- 6.Qato DM, Zenk S, Wilder J, Harrington R, Gaskin D, Alexander GC. The availability of pharmacies in the United States: 2007-2015. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0183172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Sharing Statement