Abstract

Tumor hypoxia plays a crucial role in driving cancer progression and fostering resistance to therapies by contributing significantly to chemoresistance, radioresistance, angiogenesis, invasiveness, metastasis, altered cell metabolism, and genomic instability. Despite the challenges encountered in therapeutically addressing tumor hypoxia with conventional drugs, a noteworthy alternative has emerged through the utilization of anaerobic oncolytic bacteria. These bacteria exhibit a preference for accumulating and proliferating within the hypoxic regions of tumors, where they can initiate robust antitumor effects and immune responses. Through simple genetic manipulation or sophisticated synthetic bioengineering, these bacteria can be further optimized to improve safety and antitumor activities, or they can be combined synergistically with chemotherapies, radiation, or other immunotherapies. In this review, we explore the potential benefits and challenges associated with this innovative anticancer approach, addressing issues related to clinical translation, particularly as several strains have progressed to clinical evaluation.

Keywords: anaerobic bacteria, hypoxia, cancer, Clostridium

Introduction

The development of hypoxia is one of the biological hallmarks of cancer that results from an imbalance between increased oxygen consumption by rapidly proliferating tumor cells and poor vascularization [1], which can be observed in up 50–60% of locally advanced solid cancers [2]. Hypoxic tumors usually exhibit oxygen tensions of <10 mmHg, whereas in normal tissues, the oxygen tension ranges between 24–66 mmHg [3]. Traditionally, hypoxic tumor cells are believed to be situated at a considerable distance from the functional blood supply, typically exceeding 100–200 μm, and pose a challenge for systemic therapies to effectively reach them [4]. However, not all instances of hypoxia in tumors can be solely attributed to deficiencies in blood supply. By examining hypoxia and germination of Clostridium novyi-NT (C. novyi-NT) in subcutaneous GL261 mouse tumors, we demonstrated that tumor hypoxia is not confined to the necrotic center but may also manifest as small pockets dispersed throughout the entire tumor body [5]. This is consistent with other studies indicating that aggressive cancer cells can randomly induce intracellular hypoxia through elevated oxygen consumption via the mitochondrial respiratory function [6, 7].

The hypoxic state is crucial in tumors and promotes a more aggressive phenotype leading to proliferative signaling, replicative immortality, angiogenesis, invasion and metastasis as well as immunosuppression and an impaired anti-tumor immunity [8]. Ultimately, it renders tumors less sensitive to radiation, some forms of chemotherapy and immunotherapy, thereby majorly contributing to treatment resistance and patient cancer death. However, attempts to enhance oxygen levels through direct delivery or by manipulating blood flow to the tumor, and reducing oxygen demand have only shown limited benefits.

Central to the therapeutic exploration of tumor hypoxia has been the discovery of the hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs), comprising of HIF-1, HIF-2 and HIF-3 and the two distinct subunits α (HIF-1α, HIF-2α, and HIF-3α) and β (HIF-1β). These transcription factors that are stabilized under low oxygen conditions, regulate the expression of genes involved in cell metabolism, angiogenesis, cell survival, and metastasis in response to hypoxia. Several inhibitors targeting HIF-1 and molecules within its up- and downstream pathways (e.g. VEGF, CAIX) have been developed [9]. One example is everolimus, a mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor that downregulated the HIF-1 pathway, which, in combination, showed efficiency in metastatic papillary renal cell carcinoma [10]. Other promising strategies to counteract the effects of hypoxia include hypoxia-activated prodrugs (HAPs) such as Tirapazamine, AQ4N (banoxantrone) and EO9 (apaziquone), which are bioreductive drugs that can be reduced into active forms when in hypoxic tumor sites with little toxicity to normal tissues [11]. Despite the compelling rationale and extensive research, implementation of hypoxia-targeting drugs into clinic has not been successful due to various reasons [12] and currently, there is no FDA-approved agent for this approach.

Finally, the profound role of tumor hypoxia and the difficulties associated with the development of effective hypoxia-targeting agents to address this high-priority unmet need led scientists to leave the beaten path and created a niche for hypoxia-targeting bacteria in cancer therapy. In contrast to drugs that rely on the vasculature for effective delivery and are limited by incomplete tissue penetration, bacteria are live organisms that can penetrate deeply into the tumors, target hypoxic tumor regions, proliferate and eradicate independently from other factors [13].

Bacteria in Cancer Therapy

A long history of observations spanning over 200 years suggests that natural bacterial infections can induce tumor regressions. Notable instances include Vautier’s report in 1813, indicating tumor regressions in cancer patients who developed gas gangrene [14], W. Busch’s findings in 1866 [15], F. Fehleisen’s work in 1882 [15], and the experiments by William B. Coley, who explored the use of Streptococcus pyogenes to treat cancer [16]. Since then, various bacterial genera have been harnessed for their ability to target and inhibit solid tumors, including representatives of Escherichia, Salmonella, Clostridium, Pseudomonas, Listeria, Bifidobacterium, Streptococcus, Lactobacillus, Caulobacter, of which Listeria, Clostridium, Bifidobacterium and Salmonella have entered the clinical trial stage, and Mycobacterium bovis Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) is the only FDA-approved bacterial agent for the therapy of carcinoma in situ of the bladder to date.

Yet, transforming a cancer into a localized infection for tumor destruction is not trivial. The very pathomechanisms utilized to eliminate the cancer cells can cause potentially life-threatening consequences in those heavily pre-treated, immune compromised patients. In general, bacterial infections exert antineoplastic effects through various mechanisms and interplays with the host immune system. First, bacteria have intrinsic antitumor properties which may vary based on bacterial strains and related to their specific microbial associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) like LPS and flagella. Most bacteria must colonize tumors as a prerequisite for a therapeutic effect; however, anti-tumor effects have also been observed after injection of inactivated bacteria which are unable to establish tumor colonization [17]. Second, bacteria can recruit immune cells to the tumor site and trigger innate as well as adaptive immune responses, which may aid the anti-tumor immunity by increasing immune surveillance and decreasing immunosuppression. Third, bacteria can disrupt the immunosuppressive TME and transform it into an immune-stimulating environment. Fourth, some bacteria can synthesize and release cytotoxic molecules that can kill cancer cells, such as phospholipase C in Clostridium spp [18]. Fifth, bacteria can be genetically engineered to aid tumor targeting (e.g. changing oxygen tolerance) and optimize anti-tumor effects by integrating genes, proteins and drugs or the immune response.

Tumor-targeting bacteria can be distinguished based on their ability to tolerate oxygen. Aerobic and facultative anaerobic bacteria (e.g. Salmonella) have the unique ability to grow in the presence of oxygen. These bacteria carry the great advantage to be able to target and accumulate in well-oxygenated small tumors or metastasis without necrotic areas which are inaccessible to obligate anaerobes. However, in such approach the bacterial spread may not be limited to the tumor but can damage healthy tissues like liver, spleen and bone marrow resulting in toxicities due to the inability to control the bacterial dissemination, as observed with Salmonella typhimurium VNP20009 [19]. Most importantly, strictly aerobes are not able to kill hypoxic tumor regions while facultative anaerobes like Salmonella, Escherichia, and Streptococcus have the ability to adapt.

To mitigate safety concerns and enhance tumor-targeting specificity, anaerobes that selectively colonize the hypoxic regions of tumors and cannot survive in the well-oxygenated normal tissues, seem to be ideally suited to attack tumors while sparing the healthy normoxic tissues and restricting bacterial dissemination within the body. Not only is this approach uniquely tumor-specific and applicable to a wide range of different cancers but attacking tumor hypoxia is a crucial component of tumor killing as hypoxic cells give rise to therapy failures and their removal will sensitize the tumor to conventional therapies, such as chemotherapy. Several candidates have undergone testing in animal models, with Clostridium being the most advanced and having progressed to human trials (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical trials of bacterial therapeutics in human patients and canines with spontaneous tumors.

| Category | Species | Strain | NCT number | Phase | Cancer type | Patients | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clostridium Novyi | Human | Clostridium Novyi-NT | NCT00358397 | I | Colorectal cancer | 2 | Terminated. |

| Human | Clostridium Novyi-NT | NCT01118819 | I | Solid tumor malignancies | 5 | Terminated. | |

| Human | Clostridium Novyi-NT | NCT01924689 | I | Solid tumor malignancies | 24 | 10 of the 24 patients (42%) had partial tumor reductions linked to toxicities such as sepsis, gas gangrene and pathologic fracture [50]. | |

| Canine | Clostridium Novyi-NT | 1 | 6 of 16 dogs (37.5%) had anti-tumor responses (3 complete and 3 partial responses) [47]. Toxicities were observed. | ||||

| Clostridium butyricum | Human | CBM 588 Probiotic Strain | NCT03829111 | I | Renal cell carcinoma | 30 | Progression-Free Survival (PFS) was significantly longer in patients receiving nivolumab-ipilimumab with CBM588 than without (12.7 months versus 2.5 months) [80]. |

| Human | CBM 588 Probiotic Strain | NCT03922035 | I | Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Cell Neoplasm | 36 | Unpublished, active, not recruiting. | |

| Human | CBM 588 probiotic strain (combined with cabozantinib/nivolumab) | NCT05122546 | I | Metastatic renal cell carcinoma | 31 | Unpublished, active, not recruiting. | |

| Bifidobacterium longum | Human | APS001F (Bifidobacterium longum expressing cytosine deaminase) | NCT01562626 | I/II | Advanced and/or Metastatic Solid Tumors | 75 | Unpublished, suspended; Patients were injected with APS001F followed by oral flucytosine (5-FC), that was locally converted into 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). |

| Human | bacTRL-IL-12 | NCT04025307 | I | Solid Tumors | 5 | Unpublished, suspended; Patients were injected with bacTRL-IL-12. | |

| Salmonella spp. | Human | TXSVN (a weakened form of a live vaccine strain CVD908ssb strain) | NCT03762291 | I | Multiple Myeloma | 1 | Unpublished, active, not recruiting. The study aimed to determine the largest safe dose of TXSVN and its side effects. |

| Salmonella typhimurium | Human | VNP20009 | I | Metastatic melanoma and metastatic renal cell carcinoma | 25 | Dose-related increase of cytokines was observed but none of patients had tumor regression [73]. | |

| Human | VNP20009 | I | Metastatic melanoma | 4 | Salmonella can be infused with mild side effects at certain dose. No objective clinical responses were found [74]. | ||

| Human | VNP20009 | NCT00004216 | I | Refractory, superficial solid tumors | 12–40 | Completed; Unpublished. | |

| Canine | VNP20009 | Multiple refractory or advanced cancers | 41 | 42% of dogs had bacterial growth in tumor tissue; 15% had an anti-tumor response (4 complete and 2 partial responses) [65]. Significant side effects occurred in a fraction of dogs. | |||

| Human | TAPET-CD (expressing the E. coli cytosine deaminase) | I | Refractory cancer | 3 | S. typhimurium was functional in delivering cytosine deaminase into tumors [75]. | ||

| Human | Attenuated S. typhimurium expressing human interleukin-2 (IL-2) | NCT01099631 | I | Hepatoma, Liver Neoplasms and Biliary Cancer | 22 | Completed; Unpublished. | |

| Canine | S. typhimurium encoding IL-2 (SalpIL2) | Osteosarcoma | 19 | Orally administered; dogs receiving SalpIL2/doxorubicin had significantly longer disease‐free interval (DFI) than a dogs treated with doxorubicin. Dogs treated with lower doses of SalpIL2 also had longer DFI than dogs treated using the highest SalpIL2 dose. SalpIL2 is safe and well tolerated [38]. | |||

| Human | VXM01 (anti-VEGFR-2) | I | Advanced pancreatic cancer | 30 | Tumor perfusion was significantly reduced after 38 days in vaccinated patients along with increased serum level of VEGF-A and collagen IV [81]. | ||

In this Review, we discuss the most promising hypoxia-targeting bacteria, the current state of their preclinical testing and clinical development. In addition, we highlight their use as immunoadjuvants in combination with other immunotherapies and issues related to clinical translation.

Engineered hypoxia-targeting bacteria

The strains Salmonella typhimurium, Clostridium novyi and Bifidobacterium spp. have received considerable attention as hypoxia-targeting agents because of the advanced understanding of their pathogenicity and genetics. Deletion of major virulence genes in these wildtype bacteria is usually required to minimize toxicity and allow their use as a therapeutic. So far, there has been few engineering efforts on manipulating the hypoxia-targeting; rather other engineering targets have been pursued to acquire improved safety and antitumor activities.

Clostridium novyi

The Clostridia genus comprises a diverse and extensive group of obligate anaerobe, gram-positive, spore-forming bacteria that thrive exclusively in hypoxic conditions [20]. Mainly Clostridium novyi (C. novyi) (ATCC No. 19402) has been explored as a cancer therapeutic in the form of spores for systemic and intratumoral administration in animals and human trials. The strain (ATCC No. 19402) was initially identified through an in vivo screening of a panel of anaerobic bacterial strains for their ability of geminating in implanted mouse tumors. To obtain the considerably safer C. novyi-NT (NT=Non Toxic) strain the α-toxin gene was removed from the wildtype C. novyi simply by heating of spores at 70°C for 15 min, owing to its location within a phage episome [21]. A complete gene sequencing and annotation provided the ground work for further genomic modification of C. novyi-NT [18]. To overcome the difficulties in site-specific genetic manipulation in Clostridia, Kuehne at al developed ClosTron technique as a modification of TargeTron™ platform (Sigma-Aldrich) based on the retro-homing mechanism of group II introns, which carries an antibiotic selection marker and an insertion capacity of 0.3–0.4 kb DNA [22, 23]. In one study, Staedtke et al constructed a C. novyi-NT-ANP strain that secrets the human atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), a 28-amino acid peptide normally secreted from the cardiac atria which has demonstrated suppression of acute inflammatory response induced by reagents such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) in mice [24]. The human ANP cDNA was optimized for Clostridium codon and cloned with C. novyi PLC signal peptide sequence under the control of the C. novyi flagellin promoter in a plasmid targeting knock-in in the 153s site, which was introduced into C. novyi-NT via conjugation with E. coli. When treating subcutaneous tumors in mice via intratumoral injection, C. novyi-NT-ANP markedly reduced the treatment-related animal death and improved the tumor clearance [24].

In the recent years, CRISPR/Cas9 methods have been developed to achieve gene knockout and site-specific insertion in C. novyi-NT as detailed by Dailey et al [25]. This process requires the construction of a plasmid carrying the sgRNA, homology-directed repair (HDR) cassette with gene insert and SpCas9n Cas9nickase and selection of clones. In order to overcome the difficulties in gene transfer into Clostridia, Dailey et al developed a method of generating calcium competent bacteria with the help of Oxyrase [25]. This approach considerably simplified the procedure, improved the targeting flexibility and freed up the constrains in insert size of genetic engineering in C. novyi-NT.

Bifidobacterium spp.

The genus Bifidobacterium contains approximately 57 (sub)species. They are among the dominant bacterial populations in the gastrointestinal tract and the normal inhabitants of a healthy human gut. Bifidobacterium is obligate anaerobe and targets tumors via hypoxia. Owing to their non-pathogenic nature, Bifidobacterium is the only bacterium that is therapeutically used in its wildtype form and has not required modifications of virulence factors. However, Bifidobacterium alone lacks direct oncolytic effects and showed no antitumor effects in mouse models despite successful tumor colonization. Thus, a number of studies of Bifidobacterium related to cancer therapies have utilized its probiotic effects in modulating immune responses [26, 27] and exploiting it as a delivery vehicle. As such, Bifidobacterium has been investigated as a carrier engineered to express therapeutic genes. APS001F is a genetically engineered Bifidobacterium longum (B. longum) strain that expresses a cytosine deaminase (CD) with a mutation at the active site to increase the enzyme activity that converts 5-fluorocytosine (5-FC) prodrug to 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), with a spectinomycin-resistant marker [28]. This strain was used in clinical trial (NCT01562626) of patients with advanced and/or metastatic solid tumors, whose results remain unpublished. In a different approach, Tang et al has used selective germination of Bifidobacterium in tumoral hypoxia to achieve targeted delivery of nanoparticles for high intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) treatment of xenograft tumor [29]. Bifidobacterium bifidum (BF) and AP-PFH/PLGA NPs (aptamers CCFM641–5-functionalized Perfluorohexane (PFH) loaded poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles) carrying BF-binding aptamers were injected in tumor-bearing mice. AP-PFH/PLGA NPs were shown to target BF colonized in tumor with higher tumor accumulation, which led to significantly enhanced HIFU therapeutic efficiency [29].

Salmonella typhimurium

Salmonella typhimurium (S. Typhimurium) is a rod-shaped, non-spore-forming, gram-negative pathogen of the Enterobacteriaceae family that causes food poisoning in humans, resulting in gastroenteritis. As a representative of the facultative anaerobes, S. typhimurium can grow under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions and thus is able to colonize nonhypoxic and hypoxic tumor regions as well as metastasis accessible by the circulatory system. Live S. typhimurium bacteria can be injected IV in mice and reach the tumor at more than 1000 times the concentration found in normal tissues [30]. Although most S. typhimurium reside in necrotic/hypoxic tumor tissue as large colonies, a fraction of the bacterium may be able to spread to healthy tissues where it potentially can cause damages [31]. To avoid this complication, S. typhimurium was engineered to reduce its ability to survive in normal tissues, thus strengthening the tumor targeting specificity. By placing the essential asd gene, which encodes an enzyme needed for diaminopimelic acid (DAP) synthesis of the bacterial cell wall, under the control of a hypoxia-promoter, Salmonella strain YB1 was able to exclusively grow under the anaerobic conditions of the tumor and could not survive in healthy, normoxic tissues when DAB is not synthesized [32]. Other strategies to improve safety included targeting of Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which is a major contributor to gram-negative sepsis and a potent stimulator of TNFα. Disruption of msbB gene using homologue recombination construct carrying an antibiotic selection marker impaired LPS formation and diminished TNFα induction with a subsequent reduction of treatment-related toxicities in mouse models [30]. By disrupting purI in addition to msbB gene, a widely used VNP20009 strain was created from the wildtype ATCC 14028 strain and showed greatly reduced bacterial virulence while maintaining its antibiotic sensitivity and genetic stability [19]. In a different approach, relA and spoT double mutations in ΔppGpp strain significantly attenuated S. typhimurium’s virulence in host animals [33, 34]. A strain expressing secretory Vibrio vulnificus flagellin B (FlaB) based on ΔppGpp has demonstrated enhanced anti-tumor immune response by triggering TLR5-mediated host reactions [35]. However, attenuated S. typhimurium strains often suffer insufficient efficacies in tumor clearance in various animal models. Aiming to improve its efficacy, S. typhimurium was subjected to nitrosoguanidine (NTG) mutagen and selected in vitro for auxotroph of leucine and arginine [36]. The resulting S. typhimurium A1 and subsequent in vivo selected S. typhimurium A1-R demonstrated superior tumor clearance in mouse tumor models [36, 37]. Lastly, the host immune response is critical for the antitumor effects of Salmonella which led to the creation of the IL2-secreting Salmonella strain and several other cytokine-expressing strains (e.g. IFNγ, LIGHT, IL-12, IL-18), that amplified the immune response [38–43].

Preclinical and Clinical Experience

Clostridium novyi-NT

The initial indication of Clostridium’s ability to colonize tumors emerged from studies involving the intravenous injection of C. tetani into mice with both transplanted and spontaneous tumors [44]. Subsequent investigations revealed that the intravenous administration of the non-pathogenic M−55 strain of C. butyricum, later reclassified as C. sporogenes ATCC13732, resulted in oncolysis in both mice and human patients [45]. Nevertheless, when tested in patients with glioblastomas, a high number of complications were noted, including abscess formation and mortality, while the clinical response rate remained unaffected [46].

After the emergence of the C. novyi-NT strain in the 2000s, the bacterium has swiftly become one of the most studied and successful bacterial oncolytics. C. novyi-NT displays a high sensitivity to oxygen. Once the otherwise inert C. novyi-NT spores are exposed to hypoxia, the spores collapse and vegetative bacteria with propeller-like flagella as a means of motility outgrow the spores and penetrate through the hypoxic regions of the cancer [21]. Importantly, robust germination is required for an effective anti-tumor response but may result in toxicities despite the specific tumor targeting mode [47–50]. Figure 1 shows that the germination pattern of C. novyi-NT aligns with the regions of tumor hypoxia und spares normoxic tissues. Interestingly, the germination of spores also extends to micro-invasive lesions and neoplastic vessels (Figure 2) beyond the main tumor mass suggesting that cancer cells can induce a widespread hypoxic state, possibly through an increased oxygen consumption via the mitochondrial respiratory chain [6, 7]. This finding is also consistent with our unpublished observations that C. novyi-NT spores have the capacity to germinate in certain cancer cell lines even under normoxic culture conditions. Furthermore, it is also important to note that the germination appears highly specific to tumor hypoxia, as these bacteria do not colonize hypoxic or inflammatory lesions unrelated to neoplasia [51, 52]. The reason for this is not known but it has been speculated that features of tumor-generated hypoxia and induced metabolic changes could be responsible.

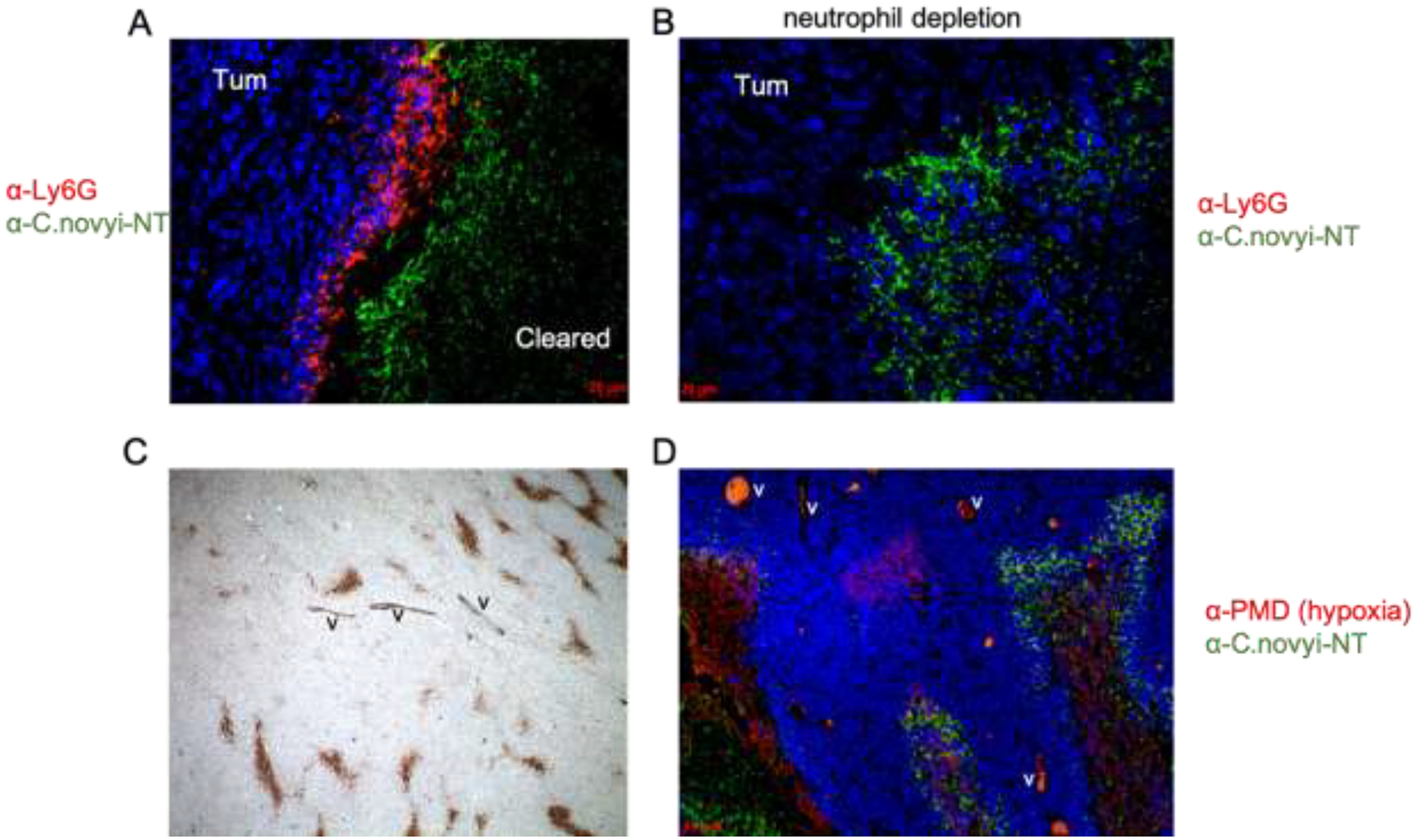

Figure 1.

Neutrophil-depletion was able to facilitate the complete tumor clearance in the subcutaneous GL261 mouse tumor model.

A. Accumulation of neutrophils blocked the expansion of germinated C. novyi-NT in the tumor. GL261 tumor was injected with C. novyi-NT spores and was harvested after 24 hours. Neutrophils were stained by 1A8 anti-Ly6G antibody (red), C. novyi-NT was stained in green, and nuclei were stained in blue by DAPI.

B. Depletion of neutrophils enabled the expansion of C. novyi-NT in the tumor. GL261-bearing mice were pre-treated by neutrophil-depleting anti-Ly6G antibody 24 hours prior to the C. novyi-NT spore injection. Tumors were harvested and stained same as described in A.

C. Presence of hypoxia pockets in non-necrotic tumor body. GL261 tumor was labeled by pimonidazole (PMD) via intraperitoneal (IP) injection in the mouse. Immunohistochemistry with anti-PMD Hypoxyprobe-1 antibody showed the hypoxic areas in the tumor (brown). Section was counterstained by hematoxylin (blue). Magnification: 5x.

D. C. novyi-NT was able to spread through the hypoxic pockets in the tumor body after neutrophil depletion. GL261 tumor bearing mice were pre-treated with anti-Ly6G antibody 24 hours prior to C. novyi-NT spore injection. One hour before harvesting at 12 hours, tumor was labeled by PMD via IP injection and the immunofluorescence staining showed hypoxic area in red, C. novyi-NT in green and nuclei in blue.

Figure 2.

C. novyi-NT germinated in an invasive tumor satellite and in a tumor blood vessel structure in the brain.

A. In the F98 rat glioma model, C. novyi-NT spores were injected in the brain tumor. A gram staining of the brain section showed extensive germination (blue) in the brain tumor (yellow arrow heads), including germination in the tumor satellite (S, yellow arrow) that invaded in the brain tissue (Br).

B. In the VX2 rabbit brain tumor model, C. novyi-NT spores were injected in the brain tumor. A gram staining of the brain section showed extensive germination (blue, yellow arrow heads) in the brain tumor (Tum) and germination in a blood vessel structure adjacent to the tumor (black arrow) that invaded in the brain tissue (Br).

The mechanism by which C. novyi-NT induces tumor cell death is multifaceted and includes tumor cell lysis, toxin production, induction of a robust inflammatory response involving the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and the recruitment of immune cells to the infection site to generate a durable adaptive anti-tumor immunity as well as the disruption of tumor metabolism in the tumor microenvironment. Several exotoxins assist C. novyi-NT in the tumor killing such as phospholipases, lipases and haemolysins that damage tumor membranes, while other toxins are internalized and interfere with critical tumor cell functions [18]. The clostridial infection also causes an initial accumulation of granulocytes and macrophages at the infection site, which restricts the spreading of the bacteria within the tumor and into surrounding normal tissues [5]. The infection results in elevated cytokines and chemokines including IL6, TNFα and recruitment of adaptive immune cells including CD8+ T lymphocytes to help eliminate the tumors [24, 49]. Lastly, C. novyi-NT was also shown to trigger the release of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligands (TRAILs) from PMNs, thus inducing cancer cell apoptosis [53].

Preclinical studies in rodents, rabbits, and canines have demonstrated the potential of C. novyi-NT to target a variety tumor types, including colon cancer, breast cancer, glioblastomas, sarcomas and peripheral nerve sheath tumors, among others. C.novyi-NT was shown to eradicate a variety of experimental tumors after intravenous and intratumoral injections and mice were protected from tumor re-challenge [21, 47, 49, 51, 54, 55]. However, it was found that local, intratumoral spore injections are superior to the intravenous administration due to a locally higher but systemically lower spore number resulting in improved anti-tumor responses, with objective response rates of 40% vs. 9% after intratumoral and intravenous administration respectively, and reduced toxicities [47, 55]. These results had significant impact on the clinical investigations which have since focused on intratumoral spore delivery.

The success seen in C. novyi-NT’s preclinical studies along with the encouraging results from a companion dog trial, which showed objective response rates in 6 of the 16 dogs with spontaneous tumors, ultimately enabled a phase I study in 24 patients with treatment-resistant solid tumors (Table 1) [47]. The trial demonstrated the feasibility of intratumoral C. novyi-NT injection in cancer patients (NCT01924689), and 42% of patients showed evidence of partial tumor lysis which occurred rapidly following treatment but none had a complete response [50]. Yet, this infection – although restricted to the tumor – resulted in considerable clinical toxicities including sepsis, abscess formation, pathologic fractures and gas gangrenes in treated patients [50], emphasizing that localized robust germination is still going to cause systemic toxicities in humans, that can be serious and dose-limiting,

Toxicities are a major issue and typically occur in animals and patients a few days after treatment [24, 50]. These might be serious or therapy-limiting. Clinical signs of toxicities are those of any typical clostridial infection such as lethargy, fever, pain, sepsis and signs of systemic inflammation, gas gangrenes, abscessation that can ultimately lead to death [24, 47, 50]. The toxicity associated with C. novyi-NT seems to be contingent on factors such as spore dosage, germination level, administration route, and most notably, tumor size, with the largest impact observed in animals or patients harboring bigger tumors. Effectively managing these toxicities in animals and patients poses a considerable challenge, demanding a delicate balance both therapeutic benefits and adverse effects. Early antibiotic intervention to prevent or mitigate toxicity may prematurely eradicate the infection before achieving an anti-tumor effect. On the other hand, delaying intervention runs the risk of an unpredictable systemic inflammatory response or even death. In addition, engineering of the bacteria to knock-out known virulence factors, as discussed in the previous chapter, may indeed improve toxicity but could diminish the anti-tumor effect as virulence factors are often involved in the tumor eradication. The creation of C. novyi-NT-ANP significantly reduced treatment-associated death in mice without compromising the tumor fitness of the strain [24] but has not been evaluated in clinical trials yet.

As complete tumor destructions are unlikely due to C. novyi-NT’s inability to inhabit well-oxygenated tumor regions, efforts have been made to combine the bacteria with other treatment modalities to kill the remaining tumor cells. These methods have focused on three synergistic approaches: 1) combinations with cytotoxic drugs and/or radiation, often referred to as COBALT [21, 48]; 2) combinations with other immunotherapeutics such as immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab; and 3) genetic modifications.

The most straightforward approach to improve the antitumor activity would be the combination of bacteria with cytotoxic agents that can either address the remaining well-oxygenated tumor areas via improved drug delivery or induce tumor hypoxia to expand the bacterial spread. Several preclinical studies have shown synergistic effects between C. novyi-NT and several microtubule inhibitors and other hypoxia-inducing chemotherapeutics in different animal models, such as liposomal doxorubicin in glioblastoma mouse model [51] and HTI-286 in colon cancer model [54]. The combinations led to significant tumor reductions and, in some cases, complete tumor eradication; however, none of these combinations has advanced to clinical testing due to concerns of adverse reactions, especially due to potential synergistic toxicity.

The combination of C. novyi-NT and immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) pembrolizumab is believed to have synergistic effects in combating tumors. While C. novyi-NT can cause tumor destruction and promote inflammation, this inflammation can further attract immune cells to the tumor site. Pembrolizumab, on the other hand, can activate these immune cells against the tumor thereby creating a more robust and sustained anti-tumor response. In various animal models of cancer, the combination of C. novyi-NT and pembrolizumab showed enhanced tumor reduction compared to either agent alone (unpublished). The localized bacterial infection caused by C. novyi-NT led to an influx of immune cells, and the subsequent administration of pembrolizumab augmented the T-cell response against the tumor. A clinical trial was initiated to investigate the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of this combination in human patients with different types of tumors (NCT03435952). Preliminary data from 9 solid tumor patients reported partial responses in 22% of patients; however, results are not mature enough to assess comparison to either agent alone [56].

Bifidobacterium spp.

To date, several subspecies have been explored for their tumor targeting potential. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that Bifidobacterium selectively colonizes and proliferates in the hypoxic tumor regions after systemic administration but is not able to destroy the cancer cells owing to their non-oncolytic nature. Thus, a number of studies have explored their tumor-specific delivery capability for antineoplastic agents, as in CD-expressing B. longum resulting in the tumor site-specific conversion of 5-fluorocytosine (5-FC) to 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) which has also advanced to the human clinical trial stage but results remains unpublished [26, 27]. It is noteworthy that in contrast to Clostridia and Salmonella whose pathogenicity may limit their use in humans, Bifidobacterium is nontoxic, and the lack of toxicity could theoretically enable greater therapeutic benefits. Furthermore, there is a growing body of research that has explored their probiotic effects as a way to modulate the immune response and enhance tumor killing [26, 27]. For instance, oral administration of Bifidobacterium was reported to improve tumor control in murine models, alone and in combination with the programmed cell death protein 1 ligand 1 (PD-L1)–specific antibody therapy [57]. Despite encouraging data, definite human data are lacking to confirm this. Lastly, it should be noted that although nonpathogenic, introducing Bifidobacterium systemically might disrupt the gut’s delicate microbial balance which could theoretically affect the immune response and gastrointestinal system in unexpected ways.

Salmonella typhimurium

As a representative of the facultative anaerobes, S. typhimurium can grow under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. After injection, Salmonella are equally delivered to the tumor and normal tissues. While bacteria in the circulation and other normal tissues are swiftly eliminated by the immune system within hours to days, they exhibit a preference for growth in the tumor microenvironment, protected from the clearance of the immune system. It has been reported that S. typhimurium colonizes tumors within 3 days after intravenous injection and primarily resides in necrotic/hypoxic tumor tissue as large colonies, whereas other types of necrotic/hypoxic tissues failed to attract S. typhimurium [58, 31].

S. typhimurium induced cancer cell death is a complex process that is only partly understood. Several studies have suggested that direct cytotoxicity and indirect effects induced by the host immune response are involved in the tumor killing whereby the host immune responses launched against the tumor are more critical than Salmonella’s cytotoxic effects. Specifically, it has been reported that Salmonella induces apoptosis or pyroptosis via activation of caspase 1 and the inflammasomes [59, 60], nutrient deprivation as well as the release of certain toxins and interference with intracellular signaling pathways facilitated by their Type III secretion system [61]. In addition, investigations into the mechanisms underlying Salmonella-mediated tumor suppression revealed the bacterium’s impact on the inhibition of angiogenesis [62]. Naturally, Salmonella may also trigger danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMP) and pathogen-related molecular patterns (PAMP) which may induce a complex immune response consisting of the release of proinflammatory cytokines, the recruitment of immune cells to the tumor site and ultimately, an adaptive immune response and destruction of the tumor.

For cancer therapy, the most widely used strains are VNP20009 and ΔppGpp, both engineered to reduce virulence, as well as the IL-2 secreting Salmonella strain which amplifies the immune response [38, 39]. In addition, several new strains have been created to improve the tumor targeting specificity [32] or enhance the immune response via expression of immunoregulatory factors, which have undergone preclinical testing [38, 40–43, 63]. Numerous preclinical studies have demonstrated the promising potential of these attenuated strains, revealing reductions in tumor size across various tumor models such as melanoma, pulmonary adenocarcinoma and metastatic prostate cancer, among others [19, 64]. For instance, VNP20009 showed good safety profiles in preclinical mouse models and nonhuman primates while maintaining the anti-tumor activity of the parental strain in the mouse B16F10 melanoma model [19, 30]. Intravenously administered VNP20009 was also evaluated in a comparative canine study with spontaneously occurring cancers. In 42% of the dogs bacterial growth of VNP20009 was confirmed in the tumor tissue and 15% had a measurable anti-tumor response (4 complete responses and 2 partial responses) (Table 1) [65]. However, tumor abscessation, fever, or hemorrhage after treatment were common side effects and one treatment-related death occurred [65], highlighting that the therapeutic effect is strongly intertwined with toxicity for bacteria-based therapies.

Several other derivatives of the VNP20009 strain have been created to enhance tumor destruction. One such example is the VNP20009 strain with expression of E. coli CD that showed a significant improvement of antitumor responses in combination with 5-FC in syngeneic and xenograft colorectal mouse tumor models [66]. Other studies employed Salmonella ΔppGpp strain engineered to secrete Vibrio vulnificus flagellin B which also increased the antitumor effect markedly in mice [35]. A recent study focused on enhancing the tumor targeting specificity by genetically transforming Salmonella into an obligate anaerobe strain (YB1) that can only survive in hypoxic tumor regions thereby reducing the damage to normal cells without compromising the tumor fitness [32].

The main struggle of attenuated S. typhimurium strains appears to be the insufficient tumor destruction. Thus, Salmonella has been used with other therapeutic agents to enhance the efficacy including combinations with chemotherapy [67, 68], radiotherapy [69, 70], ICI [71, 72], and immunomodulatory cytokines [41]. As such, IL2-expressing Salmonella showed considerable antitumor activities and has been tested in mouse and canine trials [38, 63]. In addition, several other cytokines and immunoregulatory factors have been utilized to amplify the immune response with superior antitumor effects in non-metastatic and metastatic solid cancer mouse models [40–43].

Transitioning to the clinical stage, six clinical trials utilizing different attenuated Salmonella strains have been initiated in cancer patients (Table 1) [73–75]. Clinical trials have primarily focused on evaluating the safety profile, optimal dosing strategies, and overall feasibility of Salmonella administration. Preliminary results indicate that all tested strains were well tolerated with manageable side effects, including thrombocytopenia, anemia, persistent bacteremia, hyperbilirubinemia, diarrhea, and vomiting as dose-limiting toxicities [73]. However, none of the Salmonella strains tested in human so far has shown the robust colonization and antitumor responses seen in the preclinical mouse models or companion dogs [73]. The reasons are not fully understood but over-attenuation has been suggested, reinforcing the fact that strain attenuation efforts should not compromise the bacterium’s tumor fitness.

Challenges of Bacterial Therapies

Despite the potential of oncolytic bacteria that target on tumoral hypoxia as a therapeutic strategy, safety concerns remain paramount as these live bacteria can replicate and self-amplify potentially causing significant health hazards for patients and the public. Those include serious infections or bacterial overgrowth, unintended re-activation of the infection after completing therapy and bacterial shedding to other individuals or the public. While C. novyi-NT is a self-limiting infection, uncontrolled growth and dissemination of S. typhimurium could theoretically occur, particularly when systemically administered in immunocompromised patients, and may require medical management. Shedding is a well-described phenomenon for both strains and of particular concern for public health risks. Furthermore, as spores can remain in the body following the bacterial treatment (e.g. C. novyi-NT), there is concern for unintended reactivation of the infection often necessitating the use of preventative long-term antibiotics, which may add additional risks to the patients. Thus, appropriate plans need to be established to monitor for these risks. FDA has established a complex regulatory framework and published several guidelines and recommendations to aid investigator’s studies and improve safety, including ‘Nonclinical Biodistribution Considerations for Gene Therapy Products’, ‘Early Clinical Trials with Live Biotherapeutic Products: Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Control Information; Guidance for Industry’, and ‘Design and Analysis of Shedding Studies for Virus or Bacteria-based Gene Therapy and Oncolytic Products’.

Although the clinical translation of hypoxia-targeting bacteria has been cautious, several trials have been conducted to investigate the safety and efficacy over the last decade (Table 1). From these trials, it has become obvious that careful patient selection with suitable tumor characteristics (e.g. tumor size and location, presence of hypoxia) is absolutely necessary to achieve a robust and reliable bacterial tumor colonization required for an effective anti-tumor response and a reasonable safety profile. One of the main issues is the bacterial dose determination which has to depend on the tumor size and/or the extend of hypoxic/necrotic tumor regions rather than following the path of standard dose escalation utilized in clinical trials. Taking the example of oncolytic C. novyi-NT, that exclusively relies on tumor hypoxia as germination ground, the lack of reliability of successful tumor germination has been a limiting factor [5, 24, 47, 50, 51]. Although the germination rates of C. novyi-NT spores administered through intratumoral injection are higher than using intravenous injection, they exhibit considerable variability among different types and sizes of tumors, in both implanted and naturally occurring mouse models (unpublished observation) and humans, with small tumors being the most difficult to treat. In a human trial involving intratumoral injection, germination occurred in 10 out of 24 patients with predominantly surgically inoperable and diverse sarcomas [50]. To certain extend, the lower germination rate in the clinical trial could be related to the relatively low doses of spores (1×104-3×106) and large volume of saline used for diluting the spores (3 ml), compared to 6–18×106 spores in 1–3 μl injection volume used in preclinical studies [5, 50]. As revealed by examining hypoxia and germination in subcutaneous GL261 mouse tumor in a time course, tumor hypoxia can exist not only in the necrotic center, but more importantly also as small pockets throughout the tumor body, which enables spreading of the clostridial infection to initially nearby hypoxic regions and then ultimately through the entire tumor in a model of sustained germination (Figure 1) [5]. Such a model calls for injection of a small volume of spores in high concentration in multiple locations of a tumor to preserve and target hypoxic regions, achieve higher germination rates, and subsequently better anti-tumor responses. This also highlights the need of detection and monitoring of tumor hypoxic areas using imaging tools, to better evaluate the characteristics of a tumor and guide the spore injection to optimize the clinical response. New imaging tools to visualize hypoxia such as PET and emerging MRI techniques may thus be helpful to advance these therapies on the clinical path and improve results [76]. Inconsistencies in the bacterial tumor colonization have also been observed with therapeutic Salmonella strains in the treatment of metastatic cancers. For instance, in a Phase I trial using the intravenously administered VNP20009 strain only 3 out of 25 patients, dosed at 1 × 109 cfu/m2 and 3 × 108 cfu/m2, showed focal tumor colonization and no objective anti-tumor responses were observed [73]. This stands in contrast to the findings from various preclinical animal models and C novyi-NT’s clinical experience which demonstrated robust germination and therapeutic benefits in some patients. While work is continuing to understand the treatment failure of Salmonella in human cancers, future trials should also explore multiple dosing of a single tumor in an attempt to improve bacterial tumor colonization.

The clinical trials also highlight another dilemma of bacterial therapies - the unpredictability of a clinical response in human patients. The presence of bacterial colonization in the tumor tissue itself does not appear to be a “definite” correlate for a clinical response. While none of the patients who had evidence of Salmonella growth in the tumor experienced a tumor reduction [73], a fraction of patients treated with C. novyi-NT had tumor reductions independent of germination while other patients experienced tumor growth despite germination [50]. It has been our experience that a robust tumor infection is a critical prerequisite to achieve a therapeutic response, although there may be other contributory factors including tumor size and administration route, among others. One essential factor is probably the tumor type. Although a broad range of different cancers in different stages (metastatic, non-metastatic) have been treated with hypoxia-targeting bacteria, it is unknown which cancer types are particularly sensitive to this therapy and what characteristics ideal tumors should have. These characteristics could differ between bacterial strains but understanding this would be critical in order to identify patients that are more likely to benefit while avoiding exposure to patients that are unlikely going to respond to these therapies.

An effective anti-tumor response is tightly linked to toxicity and clinical signs will almost always develop in response to a robust infection, even if the infection is limited to the tumor [24, 47, 50, 73]. As these clinical symptoms are often dose- and treatment-limiting, they may thus have a strong impact on the clinical outcome. Effectively addressing these toxicities is a considerable challenge and requires the careful balancing of the timepoint and type of intervention in order to rescue the patient while avoiding premature eradication of the infection. In addition, smart genetic engineering strategies to shift towards an effective therapeutic response with lessened safety concerns are needed for both, Clostridium and Salmonella bacterial therapies. Successful strategies are unlikely to simply utilize the genetic removal of certain virulence factors as these factors are often playing important roles in the anti-tumor response. Rather, novel pathways have to be explored in bacteria or the patient to modulate the immune response in order to optimize the anti-tumor effect while reducing unwanted toxicities. One such example is the creation the an ANP-secreting C. novyi-NT strain that has demonstrated reduced cytokine release in the host by suppressing the catecholamine pathway in modulating inflammatory responses [24], as detailed in the section “Engineered hypoxia-targeting bacteria”. The inflammatory responses could also be mitigated by blocking the synthesis of catecholamine through inhibition of tyrosine hydroxylase using metyrosine [24]. Another way to limit the toxicity is the development of quorum-sensing systems, as done for Salmonella, wherein therapeutic protein expression is only triggered when a certain concentration of inducer molecules is reached thereby increasing the targeting specificity [77].

Another major challenge of bacteriotherapies is the incomplete tumor clearance and the underlying mechanisms may differ depending on the bacterial species. Specifically, for C. novyi-NT several studies have reported high percentages of partial responses in mice and dogs, and absence of total tumor clearance in human patients [5, 47, 50, 55, 78]. This has often been attributed to the normoxic tumor rims, which are undoubtedly less supportive of C. novyi-NT germination and propagation than the necrotic center. However, our recent studies have also shown that rapid accumulation of neutrophils is a critical factor which blocks C. novyi-NT from spreading to the tumor outer rims, as depletion of neutrophils via an antibody or immune suppressant led to a substantially enhanced tumor clearance in animal models (Figure 1) [5, 78]. However, such approach has so far faced reservation from clinicians involved with clinical trials, where depletion of neutrophils is considered risky in an acute bacterial infection. In addition, we have observed that re-grown tumors after the initial treatment with C. novyi-NT spores often fail to effectively germinate when re-treated with C. novyi-NT spores (unpublished observation) alike resistance. This strongly necessitates the development of rationale combination strategies to optimize clinical responses, including the combinatory use of chemotherapy, radiation or immunotherapy.

Lastly, with a few exceptions bacterial therapies have mostly been tested in rodent models that have limitations in the evaluation of infectious agents due to the species-specific sensitivity of pathogens, which could potentially affect the translatability of therapies. For instance, typhoidal Salmonella is human-adapted and does not cause disease in normal mice [79]. Rodent models furthermore fail to recapitulate other important aspects, such as toxicities, discrepancies in body volume important for intravenous bacterial/spore delivery, and dissimilarities of transplanted or genetically induced rodent tumors compared to patient tumors. Thus, evaluating bacterial therapies in more realistic settings such as veterinary trials with companion canines or felines with spontaneous tumors (or other companion animals) utilizing similar outcome measures as in human trials should strongly be considered to improve the translatability and allow for the study of specific tumor characteristics that might otherwise be challenging to investigate in human patients. For instances, many spontaneous dog tumors resemble the pathological and molecular features of human tumors [47] and the immune system between both species is similar which forms a strong rationale to supplement experimental models with naturally-occurring ones to guide human investigations and accelerate clinical success.

Despite these challenges, there is much opportunity in this field because bacteria utilize unique mechanisms to eradicate tumor hypoxia, which has been difficult to achieve with conventional drugs. By better understanding, controlling and managing the currently existing challenges – bacterial/spore delivery, efficacy and safety – it is possible that these therapies could become an integral part in the treatment of certain intractable cancers in the future.

Conclusion and Perspective

Bacterial therapies have emerged as a promising alternative for cancer treatment, offering unique mechanisms of action and the potential to overcome some limitations of conventional therapies. Especially, their ability to target previously unreachable hypoxic regions within malignancies and deliver drugs or other payloads to these areas is exciting. With further research and development, bacterial therapies could become a valuable addition to the cancer treatment arsenal, ultimately improving patient outcomes and survival. Future research should focus on addressing the above-mentioned challenges, optimizing bacterial strains and delivery systems, and exploring combination therapies with conventional treatments to maximize the clinical potential of bacterial therapies for cancer.

Acknowledgments

V.S. was supported by the NCI K08CA230179 and the Sontag Distinguished Scientist Award.

V.S. and R.Y.B are supported by the NCI Cancer Moonshot U01CA247576.

Funding Source

All sources of funding should also be acknowledged and you should declare any involvement of study sponsors in the study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; the writing of the manuscript; the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. If the study sponsors had no such involvement, this should be stated.

Conflict of Interest

A conflicting interest exists when professional judgement concerning a primary interest (such as patient’s welfare or the validity of research) may be influenced by a secondary interest (such as financial gain or personal rivalry). It may arise for the authors when they have financial interest that may influence their interpretation of their results or those of others. Examples of potential conflicts of interest include employment, consultancies, stock ownership, honoraria, paid expert testimony, patent applications/registrations, and grants or other funding.

Abbreviations:

- HIF

hypoxia-inducible factors

- HAPs

hypoxia-activated prodrugs

- IL6

Interleukin 6

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- PMN

polymorphnuclear cells

- PD-L1

programmed cell death protein 1 ligand 1

- ICI

immune checkpoint inhibitor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Vaupel P, Harrison L, Tumor hypoxia: causative factors, compensatory mechanisms, and cellular response, Oncologist 9 Suppl 5 (2004) 4–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Vaupel P, Mayer A, Hypoxia in cancer: significance and impact on clinical outcome, Cancer Metastasis Rev 26(2) (2007) 225–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Vaupel P, Kallinowski F, Okunieff P, Blood flow, oxygen and nutrient supply, and metabolic microenvironment of human tumors: a review, Cancer Res 49(23) (1989) 6449–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Thomlinson RH, Gray LH, The histological structure of some human lung cancers and the possible implications for radiotherapy, Br J Cancer 9(4) (1955) 539–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Staedtke V, Gray-Bethke T, Liu G, Liapi E, Riggins GJ, Bai RY, Neutrophil depletion enhanced the Clostridium novyi-NT therapy in mouse and rabbit tumor models, Neurooncol Adv 4(1) (2022) vdab184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cook CC, Kim A, Terao S, Gotoh A, Higuchi M, Consumption of oxygen: a mitochondrial-generated progression signal of advanced cancer, Cell Death Dis 3(1) (2012) e258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Prior S, Kim A, Yoshihara T, Tobita S, Takeuchi T, Higuchi M, Mitochondrial respiratory function induces endogenous hypoxia, PLoS One 9(2) (2014) e88911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hanahan D, Weinberg RA, Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation, Cell 144(5) (2011) 646–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kheshtchin N, Hadjati J, Targeting hypoxia and hypoxia-inducible factor-1 in the tumor microenvironment for optimal cancer immunotherapy, J Cell Physiol 237(2) (2022) 1285–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Feldman DR, Ged Y, Lee CH, Knezevic A, Molina AM, Chen YB, Chaim J, Coskey DT, Murray S, Tickoo SK, Reuter VE, Patil S, Xiao H, Aghalar J, Apollo AJ, Carlo MI, Motzer RJ, Voss MH, Everolimus plus bevacizumab is an effective first-line treatment for patients with advanced papillary variant renal cell carcinoma: Final results from a phase II trial, Cancer 126(24) (2020) 5247–5255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Li Y, Zhao L, Li XF, Targeting Hypoxia: Hypoxia-Activated Prodrugs in Cancer Therapy, Front Oncol 11 (2021) 700407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Spiegelberg L, Houben R, Niemans R, de Ruysscher D, Yaromina A, Theys J, Guise CP, Smaill JB, Patterson AV, Lambin P, Dubois LJ, Hypoxia-activated prodrugs and (lack of) clinical progress: The need for hypoxia-based biomarker patient selection in phase III clinical trials, Clin Transl Radiat Oncol 15 (2019) 62–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Forbes NS, Engineering the perfect (bacterial) cancer therapy, Nat Rev Cancer 10(11) (2010) 785–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Mowday AM, Guise CP, Ackerley DF, Minton NP, Lambin P, Dubois LJ, Theys J, Smaill JB, Patterson AV, Advancing Clostridia to Clinical Trial: Past Lessons and Recent Progress, Cancers (Basel) 8(7) (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Oelschlaeger TA, Bacteria as tumor therapeutics?, Bioeng Bugs 1(2) (2010) 146–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zu C, Wang J, Tumor-colonizing bacteria: a potential tumor targeting therapy, Crit Rev Microbiol 40(3) (2014) 225–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Karbach J, Neumann A, Brand K, Wahle C, Siegel E, Maeurer M, Ritter E, Tsuji T, Gnjatic S, Old LJ, Ritter G, Jager E, Phase I clinical trial of mixed bacterial vaccine (Coley’s toxins) in patients with NY-ESO-1 expressing cancers: immunological effects and clinical activity, Clin Cancer Res 18(19) (2012) 5449–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bettegowda C, Huang X, Lin J, Cheong I, Kohli M, Szabo SA, Zhang X, Diaz LA Jr., Velculescu VE, Parmigiani G, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Zhou S, The genome and transcriptomes of the anti-tumor agent Clostridium novyi-NT, Nat Biotechnol 24(12) (2006) 1573–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Clairmont C, Lee KC, Pike J, Ittensohn M, Low KB, Pawelek J, Bermudes D, Brecher SM, Margitich D, Turnier J, Li Z, Luo X, King I, Zheng LM, Biodistribution and genetic stability of the novel antitumor agent VNP20009, a genetically modified strain of Salmonella typhimurium, J Infect Dis 181(6) (2000) 1996–2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Maclennan JD, The histotoxic clostridial infections of man, Bacteriol Rev 26(2 Pt 1–2) (1962) 177–276. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Dang LH, Bettegowda C, Huso DL, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Combination bacteriolytic therapy for the treatment of experimental tumors, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98(26) (2001) 15155–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lambowitz AM, Zimmerly S, Group II introns: mobile ribozymes that invade DNA, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 3(8) (2011) a003616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kuehne SA, Minton NP, ClosTron-mediated engineering of Clostridium, Bioengineered 3(4) (2012) 247–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Staedtke V, Bai RY, Kim K, Darvas M, Davila ML, Riggins GJ, Rothman PB, Papadopoulos N, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Zhou S, Disruption of a self-amplifying catecholamine loop reduces cytokine release syndrome, Nature 564(7735) (2018) 273–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Dailey KM, Jacobson RI, Johnson PR, Woolery TJ, Kim J, Jansen RJ, Mallik S, Brooks AE, Methods and Techniques to Facilitate the Development of Clostridium novyi NT as an Effective, Therapeutic Oncolytic Bacteria, Front Microbiol 12 (2021) 624618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ngo N, Choucair K, Creeden JF, Qaqish H, Bhavsar K, Murphy C, Lian K, Albrethsen MT, Stanbery L, Phinney RC, Brunicardi FC, Dworkin L, Nemunaitis J, Bifidobacterium spp: the promising Trojan Horse in the era of precision oncology, Future Oncol 15(33) (2019) 3861–3876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Yoon Y, Kim G, Jeon BN, Fang S, Park H, Bifidobacterium Strain-Specific Enhances the Efficacy of Cancer Therapeutics in Tumor-Bearing Mice, Cancers (Basel) 13(5) (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Shioya K, Matsumura T, Seki Y, Shimizu H, Nakamura T, Taniguchi S, Potentiated antitumor effects of APS001F/5-FC combined with anti-PD-1 antibody in a CT26 syngeneic mouse model, Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 85(2) (2021) 324–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Tang Y, Chen C, Jiang B, Wang L, Jiang F, Wang D, Wang Y, Yang H, Ou X, Du Y, Wang Q, Zou J, Bifidobacterium bifidum-Mediated Specific Delivery of Nanoparticles for Tumor Therapy, Int J Nanomedicine 16 (2021) 4643–4659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Low KB, Ittensohn M, Le T, Platt J, Sodi S, Amoss M, Ash O, Carmichael E, Chakraborty A, Fischer J, Lin SL, Luo X, Miller SI, Zheng L, King I, Pawelek JM, Bermudes D, Lipid A mutant Salmonella with suppressed virulence and TNFalpha induction retain tumor-targeting in vivo, Nat Biotechnol 17(1) (1999) 37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Liang K, Liu Q, Li P, Luo H, Wang H, Kong Q, Genetically engineered Salmonella Typhimurium: Recent advances in cancer therapy, Cancer Lett 448 (2019) 168–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Yu B, Yang M, Shi L, Yao Y, Jiang Q, Li X, Tang LH, Zheng BJ, Yuen KY, Smith DK, Song E, Huang JD, Explicit hypoxia targeting with tumor suppression by creating an “obligate” anaerobic Salmonella Typhimurium strain, Sci Rep 2 (2012) 436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Song M, Kim HJ, Kim EY, Shin M, Lee HC, Hong Y, Rhee JH, Yoon H, Ryu S, Lim S, Choy HE, ppGpp-dependent stationary phase induction of genes on Salmonella pathogenicity island 1, J Biol Chem 279(33) (2004) 34183–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Na HS, Kim HJ, Lee HC, Hong Y, Rhee JH, Choy HE, Immune response induced by Salmonella typhimurium defective in ppGpp synthesis, Vaccine 24(12) (2006) 2027–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Zheng JH, Nguyen VH, Jiang SN, Park SH, Tan W, Hong SH, Shin MG, Chung IJ, Hong Y, Bom HS, Choy HE, Lee SE, Rhee JH, Min JJ, Two-step enhanced cancer immunotherapy with engineered Salmonella typhimurium secreting heterologous flagellin, Sci Transl Med 9(376) (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Zhao M, Yang M, Li XM, Jiang P, Baranov E, Li S, Xu M, Penman S, Hoffman RM, Tumor-targeting bacterial therapy with amino acid auxotrophs of GFP-expressing Salmonella typhimurium, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102(3) (2005) 755–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Zhao M, Yang M, Ma H, Li X, Tan X, Li S, Yang Z, Hoffman RM, Targeted therapy with a Salmonella typhimurium leucine-arginine auxotroph cures orthotopic human breast tumors in nude mice, Cancer Res 66(15) (2006) 7647–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Fritz SE, Henson MS, Greengard E, Winter AL, Stuebner KM, Yoon U, Wilk VL, Borgatti A, Augustin LB, Modiano JF, Saltzman DA, A phase I clinical study to evaluate safety of orally administered, genetically engineered Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium for canine osteosarcoma, Vet Med Sci 2(3) (2016) 179–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Wang D, Wei X, Kalvakolanu DV, Guo B, Zhang L, Perspectives on Oncolytic Salmonella in Cancer Immunotherapy-A Promising Strategy, Front Immunol 12 (2021) 615930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Saltzman DA, Katsanis E, Heise CP, Hasz DE, Vigdorovich V, Kelly SM, Curtiss R 3rd, Leonard AS, Anderson PM, Antitumor mechanisms of attenuated Salmonella typhimurium containing the gene for human interleukin-2: a novel antitumor agent?, J Pediatr Surg 32(2) (1997) 301–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Loeffler M, Le’Negrate G, Krajewska M, Reed JC, Attenuated Salmonella engineered to produce human cytokine LIGHT inhibit tumor growth, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104(31) (2007) 12879–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Loeffler M, Le’Negrate G, Krajewska M, Reed JC, IL-18-producing Salmonella inhibit tumor growth, Cancer Gene Ther 15(12) (2008) 787–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Yoon W, Park YC, Kim J, Chae YS, Byeon JH, Min SH, Park S, Yoo Y, Park YK, Kim BM, Application of genetically engineered Salmonella typhimurium for interferon-gamma-induced therapy against melanoma, Eur J Cancer 70 (2017) 48–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Malmgren RA, Flanigan CC, Localization of the vegetative form of Clostridium tetani in mouse tumors following intravenous spore administration, Cancer Res 15(7) (1955) 473–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Moese JR, Moese G, Oncolysis by Clostridia. I. Activity of Clostridium Butyricum (M-55) and Other Nonpathogenic Clostridia against the Ehrlich Carcinoma, Cancer Res 24 (1964) 212–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Carey RW, Holland JF, Whang HY, Neter E, Bryant B, Clostridial oncolysis in man, European Journal of Cancer 3(1) (1967) 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Roberts NJ, Zhang L, Janku F, Collins A, Bai RY, Staedtke V, Rusk AW, Tung D, Miller M, Roix J, Khanna KV, Murthy R, Benjamin RS, Helgason T, Szvalb AD, Bird JE, Roy-Chowdhuri S, Zhang HH, Qiao Y, Karim B, McDaniel J, Elpiner A, Sahora A, Lachowicz J, Phillips B, Turner A, Klein MK, Post G, Diaz LA Jr., Riggins GJ, Papadopoulos N, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Bettegowda C, Huso DL, Varterasian M, Saha S, Zhou S, Intratumoral injection of Clostridium novyi-NT spores induces antitumor responses, Sci Transl Med 6(249) (2014) 249ra111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Bettegowda C, Dang LH, Abrams R, Huso DL, Dillehay L, Cheong I, Agrawal N, Borzillary S, McCaffery JM, Watson EL, Lin KS, Bunz F, Baidoo K, Pomper MG, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Zhou S, Overcoming the hypoxic barrier to radiation therapy with anaerobic bacteria, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100(25) (2003) 15083–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Agrawal N, Bettegowda C, Cheong I, Geschwind JF, Drake CG, Hipkiss EL, Tatsumi M, Dang LH, Diaz LA Jr., Pomper M, Abusedera M, Wahl RL, Kinzler KW, Zhou S, Huso DL, Vogelstein B, Bacteriolytic therapy can generate a potent immune response against experimental tumors, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101(42) (2004) 15172–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Janku F, Zhang HH, Pezeshki A, Goel S, Murthy R, Wang-Gillam A, Shepard DR, Helgason T, Masters T, Hong DS, Piha-Paul SA, Karp DD, Klang M, Huang SY, Sakamuri D, Raina A, Torrisi J, Solomon SB, Weissfeld A, Trevino E, DeCrescenzo G, Collins A, Miller M, Salstrom JL, Korn RL, Zhang L, Saha S, Leontovich AA, Tung D, Kreider B, Varterasian M, Khazaie K, Gounder MM, Intratumoral njection of Clostridium novyi-NT Spores in Patients with Treatment-refractory Advanced Solid Tumors, Clin Cancer Res 27(1) (2021) 96–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Staedtke V, Bai RY, Sun W, Huang J, Kibler KK, Tyler BM, Gallia GL, Kinzler K, Vogelstein B, Zhou S, Riggins GJ, Clostridium novyi-NT can cause regression of orthotopically implanted glioblastomas in rats, Oncotarget 6(8) (2015) 5536–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Diaz LA Jr., Cheong I, Foss CA, Zhang X, Peters BA, Agrawal N, Bettegowda C, Karim B, Liu G, Khan K, Huang X, Kohli M, Dang LH, Hwang P, Vogelstein A, Garrett-Mayer E, Kobrin B, Pomper M, Zhou S, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Huso DL, Pharmacologic and toxicologic evaluation of C. novyi-NT spores, Toxicol Sci 88(2) (2005) 562–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Shinnoh M, Horinaka M, Yasuda T, Yoshikawa S, Morita M, Yamada T, Miki T, Sakai T, Clostridium butyricum MIYAIRI 588 shows antitumor effects by enhancing the release of TRAIL from neutrophils through MMP-8, Int J Oncol 42(3) (2013) 903–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Dang LH, Bettegowda C, Agrawal N, Cheong I, Huso D, Frost P, Loganzo F, Greenberger L, Barkoczy J, Pettit GR, Smith AB 3rd, Gurulingappa H, Khan S, Parmigiani G, Kinzler KW, Zhou S, Vogelstein B, Targeting vascular and avascular compartments of tumors with C. novyi-NT and anti-microtubule agents, Cancer Biol Ther 3(3) (2004) 326–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Krick EL, Sorenmo KU, Rankin SC, Cheong I, Kobrin B, Thornton K, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Zhou S, Diaz LA Jr., Evaluation of Clostridium novyi-NT spores in dogs with naturally occurring tumors, Am J Vet Res 73(1) (2012) 112–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Janku F, Fu S, Murthy R, Karp D, Hong D, Tsimberidou A, Gillison M, Adat A, Raina A, Call G, Kreider B, Tung D, Varterasian M, Pezeshki A, Goel S, Wang-Gillam A, Shepard DR, Helgason T, Masters T, Khazaie K, 383 First-in-man clinical trial of intratumoral injection of clostridium Novyi-NT spores in combination with pembrolizumab in patients with treatment-refractory advanced solid tumors, Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer 8(Suppl 3) (2020) A233–A233. [Google Scholar]

- [57].Sivan A, Corrales L, Hubert N, Williams JB, Aquino-Michaels K, Earley ZM, Benyamin FW, Lei YM, Jabri B, Alegre ML, Chang EB, Gajewski TF, Commensal Bifidobacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti-PD-L1 efficacy, Science 350(6264) (2015) 1084–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Ganai S, Arenas RB, Sauer JP, Bentley B, Forbes NS, In tumors Salmonella migrate away from vasculature toward the transition zone and induce apoptosis, Cancer Gene Ther 18(7) (2011) 457–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Hersh D, Monack DM, Smith MR, Ghori N, Falkow S, Zychlinsky A, The Salmonella invasin SipB induces macrophage apoptosis by binding to caspase-1, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96(5) (1999) 2396–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Cookson BT, Brennan MA, Pro-inflammatory programmed cell death, Trends Microbiol 9(3) (2001) 113–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Deng W, Marshall NC, Rowland JL, McCoy JM, Worrall LJ, Santos AS, Strynadka NCJ, Finlay BB, Assembly, structure, function and regulation of type III secretion systems, Nat Rev Microbiol 15(6) (2017) 323–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Tu DG, Chang WW, Lin ST, Kuo CY, Tsao YT, Lee CH, Salmonella inhibits tumor angiogenesis by downregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor, Oncotarget 7(25) (2016) 37513–37523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Saltzman DA, Heise CP, Hasz DE, Zebede M, Kelly SM, Curtiss R 3rd, Leonard AS, Anderson PM, Attenuated Salmonella typhimurium containing interleukin-2 decreases MC-38 hepatic metastases: a novel anti-tumor agent, Cancer Biother Radiopharm 11(2) (1996) 145–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Luo X, Li Z, Lin S, Le T, Ittensohn M, Bermudes D, Runyab JD, Shen SY, Chen J, King IC, Zheng LM, Antitumor effect of VNP20009, an attenuated Salmonella, in murine tumor models, Oncol Res 12(11–12) (2001) 501–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Thamm DH, Kurzman ID, King I, Li Z, Sznol M, Dubielzig RR, Vail DM, MacEwen EG, Systemic administration of an attenuated, tumor-targeting Salmonella typhimurium to dogs with spontaneous neoplasia: phase I evaluation, Clin Cancer Res 11(13) (2005) 4827–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].King I, Bermudes D, Lin S, Belcourt M, Pike J, Troy K, Le T, Ittensohn M, Mao J, Lang W, Runyan JD, Luo X, Li Z, Zheng LM, Tumor-targeted Salmonella expressing cytosine deaminase as an anticancer agent, Hum Gene Ther 13(10) (2002) 1225–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Jia LJ, Wei DP, Sun QM, Jin GH, Li SF, Huang Y, Hua ZC, Tumor-targeting Salmonella typhimurium improves cyclophosphamide chemotherapy at maximum tolerated dose and low-dose metronomic regimens in a murine melanoma model, Int J Cancer 121(3) (2007) 666–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Murakami T, DeLong J, Eilber FC, Zhao M, Zhang Y, Zhang N, Singh A, Russell T, Deng S, Reynoso J, Quan C, Hiroshima Y, Matsuyama R, Chishima T, Tanaka K, Bouvet M, Chawla S, Endo I, Hoffman RM, Tumor-targeting Salmonella typhimurium A1-R in combination with doxorubicin eradicate soft tissue sarcoma in a patient-derived orthotopic xenograft (PDOX) model, Oncotarget 7(11) (2016) 12783–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Platt J, Sodi S, Kelley M, Rockwell S, Bermudes D, Low KB, Pawelek J, Antitumour effects of genetically engineered Salmonella in combination with radiation, Eur J Cancer 36(18) (2000) 2397–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Liu X, Jiang S, Piao L, Yuan F, Radiotherapy combined with an engineered Salmonella typhimurium inhibits tumor growth in a mouse model of colon cancer, Exp Anim 65(4) (2016) 413–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Al-Saafeen BH, Al-Sbiei A, Bashir G, Mohamed YA, Masad RJ, Fernandez-Cabezudo MJ, Al-Ramadi BK, Attenuated Salmonella potentiate PD-L1 blockade immunotherapy in a preclinical model of colorectal cancer, Front Immunol 13 (2022) 1017780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Ebelt ND, Zuniga E, Marzagalli M, Zamloot V, Blazar BR, Salgia R, Manuel ER, Salmonella-Based Therapy Targeting Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase Restructures the Immune Contexture to Improve Checkpoint Blockade Efficacy, Biomedicines 8(12) (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Toso JF, Gill VJ, Hwu P, Marincola FM, Restifo NP, Schwartzentruber DJ, Sherry RM, Topalian SL, Yang JC, Stock F, Freezer LJ, Morton KE, Seipp C, Haworth L, Mavroukakis S, White D, MacDonald S, Mao J, Sznol M, Rosenberg SA, Phase I study of the intravenous administration of attenuated Salmonella typhimurium to patients with metastatic melanoma, J Clin Oncol 20(1) (2002) 142–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Heimann DM, Rosenberg SA, Continuous intravenous administration of live genetically modified salmonella typhimurium in patients with metastatic melanoma, J Immunother 26(2) (2003) 179–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Nemunaitis J, Cunningham C, Senzer N, Kuhn J, Cramm J, Litz C, Cavagnolo R, Cahill A, Clairmont C, Sznol M, Pilot trial of genetically modified, attenuated Salmonella expressing the E. coli cytosine deaminase gene in refractory cancer patients, Cancer Gene Ther 10(10) (2003) 737–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Gouel P, Decazes P, Vera P, Gardin I, Thureau S, Bohn P, Advances in PET and MRI imaging of tumor hypoxia, Front Med (Lausanne) 10 (2023) 1055062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Swofford CA, Van Dessel N, Forbes NS, Quorum-sensing Salmonella selectively trigger protein expression within tumors, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112(11) (2015) 3457–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Staedtke V, Roberts NJ, Bai RY, Zhou S, Clostridium novyi-NT in cancer therapy, Genes Dis 3(2) (2016) 144–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Mathur R, Oh H, Zhang D, Park SG, Seo J, Koblansky A, Hayden MS, Ghosh S, A mouse model of Salmonella typhi infection, Cell 151(3) (2012) 590–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Dizman N, Meza L, Bergerot P, Alcantara M, Dorff T, Lyou Y, Frankel P, Cui Y, Mira V, Llamas M, Hsu J, Zengin Z, Salgia N, Salgia S, Malhotra J, Chawla N, Chehrazi-Raffle A, Muddasani R, Gillece J, Reining L, Trent J, Takahashi M, Oka K, Higashi S, Kortylewski M, Highlander SK, Pal SK, Nivolumab plus ipilimumab with or without live bacterial supplementation in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a randomized phase 1 trial, Nat Med 28(4) (2022) 704–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Schmitz-Winnenthal FH, Hohmann N, Niethammer AG, Friedrich T, Lubenau H, Springer M, Breiner KM, Mikus G, Weitz J, Ulrich A, Buechler MW, Pianka F, Klaiber U, Diener M, Leowardi C, Schimmack S, Sisic L, Keller AV, Koc R, Springfeld C, Knebel P, Schmidt T, Ge Y, Bucur M, Stamova S, Podola L, Haefeli WE, Grenacher L, Beckhove P, Anti-angiogenic activity of VXM01, an oral T-cell vaccine against VEGF receptor 2, in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: A randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 1 trial, Oncoimmunology 4(4) (2015) e1001217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]