Abstract

Colorectal cancer is a common malignant tumor of the digestive system. Its morbidity and mortality rank among the highest in the world. Cancer development is associated with aberrant signaling pathways. Autophagy is a process of cell self-digestion that maintains the intracellular environment and has a bidirectional regulatory role in cancer. Apoptosis is one of the important death programs in cancer cells and is able to inhibit cancer development. Studies have shown that a variety of substances can regulate autophagy and apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells through signaling pathways, and participate in the regulation of autophagy on apoptosis. In this paper, we focus on the relevant research on autophagy in colorectal cancer cells based on the involvement of related signaling pathways in the regulation of apoptosis in order to provide new research ideas and therapeutic directions for the treatment of colorectal cancer.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Autophagy, Signaling pathways, Apoptosis

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) ranks third in the prevalence of human tumors and is the second-leading cause of death [1]. CRC is ranked 5th in cancer-related mortality in Chinese men and 4th in women [2, 3]. China is in a period of cancer transition, and the cancer spectrum is changing from developing countries to developed countries. For example, the incidence of CRC has increased, and there is a tendency to be younger [4, 5]. Early CRC has no obvious symptoms, and changes in stool characteristics, abdominal discomfort, and abdominal mass may occur after the disease progresses to a certain stage. Systemic symptoms include weight loss and low-grade fever. Surgery is one of the important treatments for CRC, but it needs to consider the patient’s prognosis as well as postoperative complications. Non-surgical treatment includes chemotherapy, radiotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy, and toxicity is likely to occur during treatment. Patients have been clinically found to have a low cure rate for CRC and are more likely to relapse. Therefore, it is imperative to deeply explore the pathogenesis and treatment of CRC.

Autophagy is a highly conserved intracellular degradation program. Autophagy is an endogenous form of defense against inflammatory, autoimmune, and cellular differentiation disorders stimulated by various stress conditions such as hypoxia, low energy, and organelle damage [6]. In some cases, autophagy can be involved in cell survival or cell death processes and is environmentally dependent [7]. Mutations in autophagy-related genes are associated with multiple classes of human diseases, and regulation of autophagy can be used as an effective strategy for disease treatment [8, 9]. In cancer, autophagy plays a bidirectional regulatory role by inhibiting tumor initiation or supporting tumor progression [10]. Among cancer resistance mechanisms, cancer stem cells can use the autophagic process to maintain their resistance [11]. Cancer stem cell drug sensitivity rises after knockdown of autophagy-related proteins [12]. Autophagy can also protect DNA and render cancer cells resistant by degrading folded and deformed proteins and organelles [13]. In addition, autophagy in cancer cells is opposite to apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic agents, and the prevention of cell death by autophagy renders cells resistant to drugs [14]. Therefore, regulation of autophagy can be used as an adjuvant to anti-cancer treatment and improve patient survival [15].

Apoptosis is a genetically programmed form of cell death that is controlled by specific signaling pathways and protein kinases. And it concludes the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway, the intrinsic endoplasmic reticulum pathway, and the extrinsic death receptor pathway. Apoptosis has complex molecular biological mechanisms and plays an important role in the stability of the internal environment [16]. In CRC development, molecular alterations in the apoptosis regulatory system include upper-regulation of core anti-apoptotic genes, down-regulation of nuclear cardiac-pro-apoptotic genes, and disturbance of upstream signaling pathways involved in core apoptosis regulatory systems [17]. Because insufficient apoptosis can lead to cancer development and cancer cell drug resistance, cancer treatment focuses on targeting apoptosis.

Signaling pathways are the processes by which molecular signals are conducted to transmit extracellular signals into cells as well as intracellular signals. In cellular biological processes, there are 12 signaling pathways mainly involved, and different signaling pathways have different conduction processes, and there may be crosstalk between each signaling pathway. During the development of CRC, the main signaling pathways include the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, the AMPK signaling pathway, and the MAPK signaling pathway [18–21], and they have a wide range of effects on tumor generation, invasion, drug resistance, immunity and tumor microenvironment [22].

Autophagy and apoptosis are two programmed cell death pathways, and the relationship between them is important in the development of tumors. The complex relationship between autophagy and apoptosis varies with cell type and stimulating factors [23]. The interaction between autophagy and apoptosis is mainly manifested in three aspects [24]: First, it acts as an accessory, and autophagy acts as a dominant factor and promotes CRC cell death. Apoptosis assists autophagy and further promotes CRC cell death. The second is promotion. Autophagy can be used as a promoting factor of apoptosis and promote the killing effect of apoptosis on CRC cells. Third, as an antagonistic factor of apoptosis, autophagy does not promote apoptosis. On the contrary, inhibition of autophagy can promote apoptosis. In the development of CRC, the effects of autophagy and apoptosis cannot be ignored. The early diagnosis rate of CRC is low, and the current treatment is more limited. The treatments for CRC face metastasis, drug resistance and other treatment problems. Autophagy and apoptosis in cancer cells are involved in cancer drug resistance and metastasis of cancer cells [14, 25]. It is important to investigate the regulation of autophagy on apoptosis in CRC cells and explore new regimens for CRC treatment.

Autophagy

Concept and processes of autophagy

Autophagy belongs to type II programmed cell death and is a key cellular process. Autophagy is a major intracellular degradation system that mainly uses lysosomes to degrade misfolded proteins as well as damaged organelles [26]. The term “autophagy” was first coined by Christine de Divf in 1963. In 2016, Yoshinori Ohsumi was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering the mechanism of autophagy. Since then, autophagy has received much attention in the field of medical research.

The main process of autophagy consists of the transport of misfolded proteins or damaged organelles to the vacuole and then degradation by lysosomes. Degradation produces breakdown products that become fuels for cell metabolism and provide the energy needed for cell survival [27, 28]. From sequestration, trafficking to lysosomes, degradation, and utilization of degradation products, each step is critical and serves a different function [29]. Each process involves substances such as its core protein, which together maintain a tight and orderly mechanism of action for autophagy.

Classification of autophagy

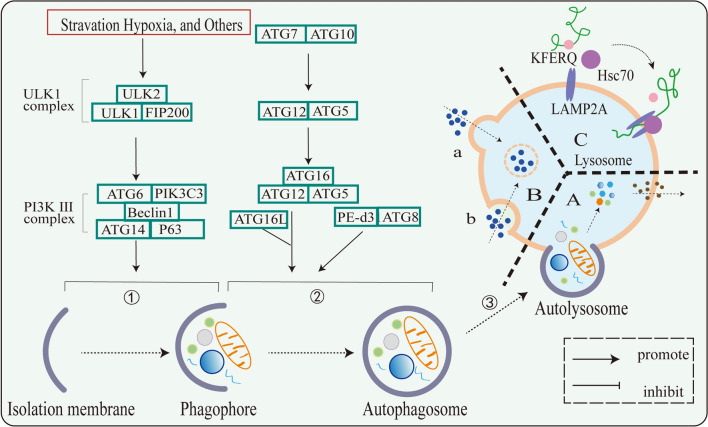

According to different modes of intracellular substrate transport to lysosomes, autophagy in mammalian cells is mainly divided into three types: macroautophagy, microautophagy, and chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) [30] (Fig. 1). Different types of autophagy have different mechanisms. Macroautophagy involves membrane elongation and microautophagy involves membrane internalization, both of them have selective or non-selective processes that transport cytoplasmic components into lysosomes for degradation. CMA is incorporation of cytosolic material into lysosomes, it does not undergo membrane deformation but is selective [31]. Macrophage autophagy is the key to cell homeostasis, which is characterized by the formation of autophagosomes, which are double-membrane vesicles [32]. Among the three types of autophagy, macroautophagy has been comprehensively studied, followed by CMA, and microautophagy has been less studied.

Fig. 1.

Mechanism of action of three types of autophagy. A Macroautophagy: ➀ membrane initiation and extension. ➁ Formation of autophagosomes. ➂ autophagosomes fuse with lysosomes to form autolysosomes. B Microautophagy: a Lysosomal protruding microautophagy. b Lysosomal invagination type microautophagy. C CMA

Macroautophagy

Macroautophagy is tightly controlled by complex signaling pathways and core autophagy proteins and is a tight cellular self-degradation program [13]. Macroautophagy is mainly triggered by stress conditions such as nutrient deprivation, energy loss, and hypoxia and involves membrane elongation and autophagic vacuole formation [31, 33, 34]. It comprises four main stages in mammalian cells: initiation, extension and autophagosome formation, fusion with lysosomes, and degradation of autophagosomes [35].

Autophagosomal membranes are membranes formed and initiated from sources such as the endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, or cytoplasm. Afterwards, cytoplasmic components appeared to be sequestered by the expansion of autophagic vacuoles or sequestration membranes. In this step, the UNC-51-like kinase 1 (ULK1) complex and the classical phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K III) complex play an important role and are positive regulators of autophagosome formation [36, 37]. When subjected to environmental stress, the ULK1 complex is activated, and then the classical PI3K III complex is activated [13, 38]. In addition, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) kinase is a negative regulator during autophagy [39, 40]. Under adequate nutritional conditions, mTORC1 phosphorylates ULK1 complexes and ATG13, leading to dissociation of ULK1 complexes and inhibition of autophagy [41, 42].

This is followed by membrane extension as well as autophagosome formation. Autophagic vacuoles encapsulate part of the cytoplasm or organelles to form autophagosomes, which are double-membrane vesicular structures. Among them, organelles include mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, and Golgi apparatus [26, 29, 41, 43, 44]. In the formation of autophagosomes, multiple complex processes are involved. Multiple ATG proteins are recruited to participate in the regulation of this process, including ATG8, ATG12, etc., and a variety of protein complexes are produced, which are important regulatory molecules in the early stages of autophagosome formation [26, 45, 46].

Finally, autophagosomes fuse with lysosomes and degrade autophagosomes. Upon fusion, autophagy undergoes transformation into autolysosomes. The inner membrane disintegrates and is degraded along with sequestrants in acidic autolysosomes by hydrolases. Normally, macrophage autophagy favors the maintenance of cellular homeostasis. Under various stress stimuli, autophagy is induced and degrades intracellular components through the above steps.

Microautophagy

Macroautophagy is characterized by membrane elongation, the appearance of double-membrane structures, and the formation of autophagosomes. Microautophagy involves membrane internalization in different ways and is divided into two types. One is the direct uptake of substrates by invaginations of the lysosomal membrane, called endosomal microautophagy. In acute starvation, endosomal microautophagy can be induced and depends on ESCRT-III and VPS4 engagement [47, 48]. In addition, endosomal microautophagy can also be dependent on nSMase2 rather than ESCRT complexes [49]. Substrate recognition of endosomal microautophagy involves the ATG8/ATG12 conjugation system and has no core ATG protein. In another class of microautophagy with prominent lysosomal membranes, not only the ATG8/ATG12 conjugation system is required to participate in membrane formation, but also core ATG protein and SNARE protein are required to mediate [50, 51]. In summary, ESCRT and SNAREs are involved in their core mechanisms of microautophagy. Following substrate acquisition by lysosomes, membrane cleavage is performed to release microautophagosomes to degrade the substrate.

CMA

Unlike the first two autophagies, CMA is highly selective. There is no vesicle involved in the process of CMA and no membrane deformation occurs. The KFERQ motif is a ‘bait’ in the substrate protein that specifically recognizes the chaperone protein HSC70. HSC70 promotes substrate protein folding and association with the target protein LAMP2A [31, 52]. Some of the chaperone protein HSC70 is present in lysosomes and is involved in CMA [53]. After the substrate protein enters the lysosome, HSC70 unfolds and unfolds the substrate protein in the lysosome [54]. Following this, the CMA translocation complex forms and dissociation of LAMP2A from the translocation complex occurs for substrate degradation [55].

Role of autophagy in organisms

Autophagy is an important regenerative link that occurs in cells. And autophagy enables damaged cells to regenerate, facilitates the maintenance of homeostasis, and promotes longevity [56]. Autophagy is involved in regulating immune inflammatory responses and has a broad role in immunity [57, 58]. Mutations in autophagy-related processes can lead to the development of many common diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative disease, metabolic disease, etc. [59]. Notably, autophagy has been implicated in tumor development [8]. Next, the role and mechanism of autophagy in tumors will be discussed.

Role of autophagy in cancer

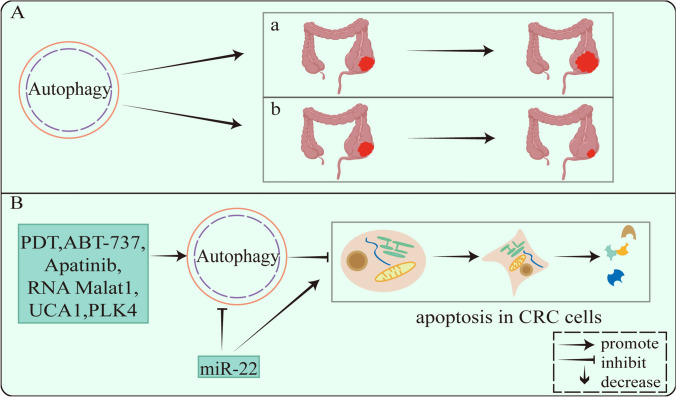

Autophagy has a bidirectional role in cancer development. Cancer cells can self-digest through autophagy in the early stage of tumors and act as inhibitory pathways to prevent tumor development. In the late stage of tumors and when nutrients are scarce, cancer cells use the energy generated by autophagy to relieve cellular metabolic pressure and promote tumor growth and progression [60, 61] (Fig. 2). Autophagy is involved in multiple links in cancer, such as immune inflammatory response, tumor microenvironment, proliferation, apoptosis, drug resistance, and tumor metabolism [15, 62, 63]. Inhibition of ER stress significantly reduces apoptosis triggered by IFN-γ induced autophagy [64]. TRPM7 mediates autophagy, inhibits cancer cell metastasis, proliferation, and promotes cancer cell apoptosis [65]. Autophagy also contributes to tumor progression by maintaining tumor growth and increasing resistance to chemotherapy. The autophagy inhibitors 3-methyladenine (3-MA) or chloroquine have been shown to increase sensitivity to chemotherapy in hepatocellular carcinoma [66]. Autophagy promotes invasion and metastasis of CRC cells by increasing epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [67]. In summary, autophagy is closely related to the development of cancer, and numerous studies have shown that autophagy acts on multiple aspects of CRC development as a key target for cancer therapy.

Fig. 2.

A Bidirectional regulatory role of autophagy in colorectal cancer: a promoting, b inhibiting. B Multiple compounds regulate apoptosis in CRC cells via autophagy

Apoptosis is a process essential for normal development and tissue homeostasis. Autophagy maintains cellular homeostasis by degrading and removing misfolded proteins and damaged organelles, while apoptosis inhibits cancer development through stress-induced cancer cell death [68]. Autophagy helps eliminate cancer cells and prevents cancer cell survival together with apoptosis. Loss or acquisition of autophagy or apoptosis impacts many pathological processes, and these phenomena interact [69]. In studies on autophagy in CRC, many experiments have demonstrated that autophagy is involved in regulating apoptosis in CRC cells (Fig. 2).

Autophagy promotes apoptosis. PROM1/CD133 is a surface marker ubiquitous on stem cells in various tissues. And the photodynamic therapy (PDT) induced the formation of autophagosomes in PROM1/CD133 (+) cells, accompanied by the up-regulation of autophagy-related proteins ATG3, ATG5, ATG7, and ATG12. The PDT significantly induces autophagy and apoptosis in PROM1/CD133 (+) cells [70]. The above studies show that autophagy as a stimulator of apoptosis, increase the process of apoptosis, induce cell death, and exert anticancer effects.

In addition, autophagy inhibits apoptosis. Apatinib, RNA Malat1, and UCA1 all induce autophagy to decrease apoptosis in human CRC cells, while blocking autophagy enhances apoptosis in human CRC cell lines [71–73]. Autophagy is able to reduce cancer cell apoptosis and prevent cancer cell death. The researchers found that it could promote cancer cell apoptosis by inhibiting autophagy. For example, miR-22 increases the sensitivity of CRC cells to 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) treatment by inhibiting autophagy to promote apoptosis [74], reduces the resistance of CRC cells to chemotherapeutic drugs, and enhances the anticancer effects of drugs.

Autophagy regulates C RC cell apoptosis based on signaling pathways

Cancer cells have multiple genetic alterations. Gene mutations in cancer cells affect signaling pathways involved in various biological processes such as cell proliferation, apoptosis, invasion and metastasis, and drug resistance. Andrographolide enhances the radiosensitivity of HCT116 cells by inhibiting glycolysis through PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway, and reduces cell survival and invasion [75]. ρ GTPase activating protein 9 (ARHGAP9) inhibits CRC cell proliferation, invasion, and EMT by targeting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway [76]. In CRC, tumor-secreted interferon induced protein 35 (IFI35) promotes proliferation of CD8 +T cells via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway [77]. Therefore, studying the signaling pathways involved in cancer development and their mechanisms of action in cancer cell biology can provide new strategies for the treatment of cancer.

Currently, several signaling cascades have been identified,and they regulate autophagy and apoptosis in a cell type-specific and signal-dependent manner [78]. TCO increases expression and activity of the enzyme sirtuin-1 (SIRT1) to induce autophagy, and inhibition of the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway [79]. Antrodia salmonea (AS) induces protective autophagy in CRC cells via AKT/mTOR signaling and then promotes apoptosis. After the use of autophagy inhibitors, the apoptosis is inhibited but the AS-induced autophagy is not affected in CRC cells [80]. These indicate that autophagy can be inhibited or promoted through relevant signaling pathways. Cancer arises due to dysregulation of molecular pathways that control cell growth, and protection of genomic stability during the cell cycle as well as the integrity of signaling networks can hinder the malignant transformation of cancer [81]. Considering that there is an interaction between autophagy and apoptosis, it is important to systematically understand the signaling pathways in tumor cells involved in the regulation of apoptosis by autophagy. It can improve our understanding of tumor pathological mechanisms and provide a theoretical basis for the development of new therapeutic strategies.

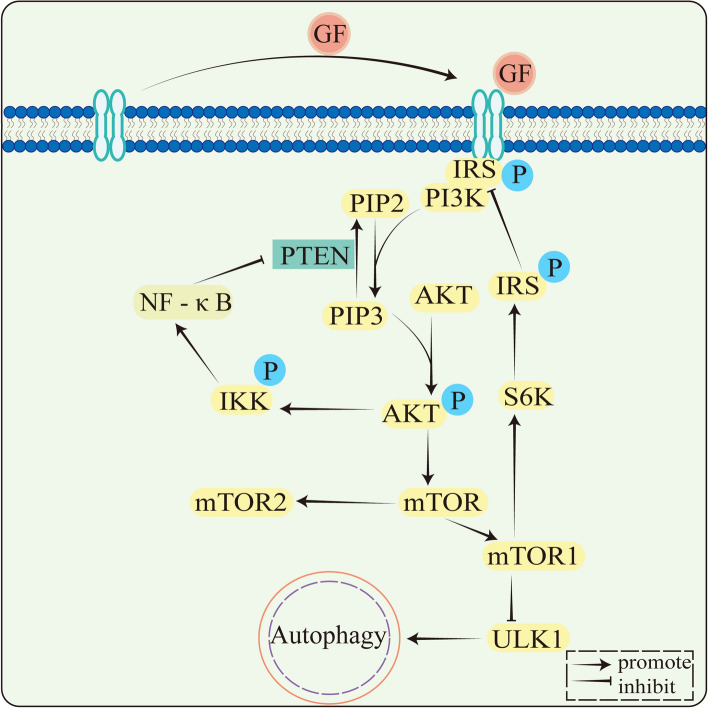

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling

Many studies have shown that PI3K/AKT/mTOR is a classical signaling pathway involved in a variety of cellular biological processes, such as regulation of cell metabolism, autophagy, cell proliferation, apoptosis and metastasis. Core components of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway include phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), AKT or protein kinase B (PKB), and the target of rapamycin (mTOR) [82]. PI3Ks are intracellular lipid kinases involved in regulating cell proliferation and differentiation. (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Membrane receptors PTK bind GF (growth factor) and phosphorylate to form dimers. Phosphorylated PTK dimers bind IRS, IRS binds PI3K, and PI3K is activated. Phosphorylation of PIP2 to PIP3 and PIP2 to PIP3 by PI3K is reversible and PTEN is involved in the dephosphorylation of PIP3. PAKT is phosphorylated by IP3 activation. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway includes both positive and negative feedback. In negative feedback, downstream of AKT is the mTOR, AKT activates mTORC1, mTORC1 activates S6K, and then phosphorylates IRS. TRS phosphorylation is followed by inhibitory activity and is unable to activate PI3K, decreasing the AKT activation. In positive feedback regulation, activation of AKT activates IKK, which then activates the NF‐κB signaling pathway, inhibits PTEN expression, attenuates PIP3 dephosphorylation, accumulates PIP3, and increases AKT activation. mTORC1 downstream genes also include ULK1, which inhibits autophagy following mTORC1 phosphorylation, and ULK1

The mTOR molecule and its involved AKT signaling pathway play a key role in autophagy and apoptosis in CRC cells. In CRC cells, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway inhibits the initiation of autophagy and promotes cancer cell growth [83]. Many studies have found that autophagy can regulate apoptosis through signaling pathways, and there are different promoting or antagonizing effects (Table 1). Pleckstrin homology-like domain family A member 2 (PHLDA2) activates autophagy through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway to promote apoptosis [84]. Grape seed procyanidins B2 (PB2) induces autophagy and apoptosis in CRC cells by PI3K/AKT signaling. PB2-induced apoptosis is reversed after the use of autophagy inhibitors, indicating that PB2-induced autophagy is positively correlated with apoptosis [85]. Justicidin A induces autophagy by converting the autophagy marker LC3-I to LC3-II by PI3K/AKT signaling, and apoptosis is inhibited following the use of autophagy inhibitors [86]. All these studies show the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling is a major autophagy-related signaling pathway, and autophagy can promote apoptosis through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway to exert efficient and synergistic anticancer effects.

Table 1.

Activation of autophagy promotes apoptosis

In addition, autophagy antagonizes apoptosis and inhibits apoptosis to increase CRC cell survival (Table 2). Lomerizine 2HCl induces apoptosis and autophagy through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, while 3-MA increases apoptosis induced by lomerizine 2HCl, indicating that the autophagy induced by lomerizine is protective autophagy [87]. Recombinant Chinese measles virus vaccine strain Hu191 (rMV-Hu191) induces autophagy in human CRC cells through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. And a decrease in the proportion of apoptosis is found after the mTOR inhibitor is used; an increase in the proportion of apoptosis is found after knockdown of the autophagy gene. These results demonstrate that rMV-Hu191-H-EGFP inhibits apoptosis by inducing autophagy through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway [88]. Salidroside increases in LC3 +autophagic vacuoles, LC3-II/LC3-I ratio, and Beclin-1. It can promote autophagy in CRC cells and enhance apoptosis following the use of autophagy inhibitors, suggesting Salidroside mediated autophagy antagonizes apoptosis [89]. Myricetin induces autophagy by inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling, which enhances apoptosis by the use of autophagy inhibitors [90]. Autophagy inhibitors NVP-BEZ235 and W922, which induce apoptosis and autophagy in CRC cells in a dose-dependent manner through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, enhance apoptosis after inhibiting autophagy [91, 92]. The above findings demonstrate that ULK1 is inhibited by activating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway to promote autophagy and apoptosis. However, after using autophagy inhibitors, the proportion of apoptosis increases, indicating that autophagy promoted through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway has an antagonistic effect on apoptosis and reduces the cytotoxic effect of apoptosis on CRC cells.

Table 2.

Inhibition of autophagy promotes apoptosis

| Name | Signaling pathway | References |

|---|---|---|

| AS | Akt/mTOR | [80] |

| W922 | PI3K/AKT/mTOR | [83] |

| Lomerizine 2HCl | PI3K/AKT/mTOR | [87] |

| RMV-Hu191 | PI3K/AKT/mTOR | [88] |

| Salidroside | PI3K/AKT/mTOR | [89] |

| Myricetin | PI3K/AKT/mTOR | [90] |

| NVP-BEZ235 | PI3K/AKT/mTOR | [91] |

| PLK4 | MAPK | [103] |

| Shikonin | MAPK | [104] |

| MJ-33 | AKT/mTOR | [106] |

| Fangchinoline | AMPK/mTOR/ULK1 | [96] |

| Selenite | AMPK | [97] |

AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway

The AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway is also the main regulatory pathway of autophagy in cells. Inhibition of both mTOR and mTORC1 enhances CRC cell proliferation, apoptosis and autophagy [93]. AMPK negatively regulates mTOR, and activation of AMPK increases Beclin-1 and LC3-II protein expression and decreases p-mTOR and p-ULK1 levels to induce autophagy in CRC cells [94]. During autophagy initiation, mTORC1 and AMPK cooperate to activate ULK1 in response to changes in the cellular environment and nutrient levels, which is a core component of autophagy. In addition, activation of AMPK can increase the expression levels of apoptosis-related proteins caspase-3, caspase-8, and caspase-9 and induce apoptosis (Table 1). Therefore, the relative activity of AMPK/mTOR in cancer cells plays a critical role in the initiation of autophagy and apoptosis, and can serve as a drug target to block CRC development.

Studies have shown that many compounds have good therapeutic effects on CRC and have potential molecular mechanisms in the AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway. Regulation of AMPK/mTOR signaling can simultaneously activate autophagy and apoptosis, but the interaction between autophagy and apoptosis needs to be further explored (Table 2). Oridonin induces apoptosis and autophagy in colon cancer DLD-1 cells by regulating the AMPK/mTOR/ULK1 pathway, and knockdown of AMPK or use of autophagy inhibitors inhibits apoptosis [95]. Consistent with the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, autophagy bidirectionally regulates apoptosis through AMPK/mTOR signaling, not only increasing apoptosis but also antagonizing apoptosis. Fangchinoline (Fan) activates the AMPK/mTOR/ULK1 signaling pathway to induce autophagy and apoptosis, and its induced autophagy inhibits apoptosis, both of which have antagonistic effects [96]. Selenite activates AMPK signaling to induce autophagy in CRC cells, and apoptosis is enhanced after silencing AMPK to inhibit autophagy. Selenite induces AMPK signaling-dependent autophagy to protect CRC cells from apoptosis [97].

MAPK signaling pathway

In addition to the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway and the AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway, other signals are also involved in the autophagic process. Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), a serine-threonine protein kinase, is an important transmitter from the surface of signaling cells to the interior of the nucleus and can be activated by cytokines, neurotransmitters and hormones. It can transmit extracellular signals, regulating cell growth, proliferation, differentiation, migration and apoptosis [98, 99]. The MAPK signaling pathway consists of three components: MAPK kinase kinase (MAP3K), MAPK kinase (MAP2K), and MAPK, which sequentially activate and regulate a variety of cellular processes [100]. MAPK signaling pathways can be divided into several types based on their downstream cytokines, such as the classical MAPK pathway, the JNK/p38/MAPK signaling pathway, and the ERK5 signaling pathway [101]. MAPK family members such as ERK, JNK, and p38 regulate diverse biological processes. They regulate apoptosis in response to extracellular stress either positively or negatively by stimulating substrate phosphorylation [102] (Table 2). Antagonisms of autophagy and apoptosis are prevalent in CRC cancers. Polo-like kinases 4 (PLK4) have been found to inhibit autophagy through the MAPK signaling pathway and contribute to tumor dormancy in the early stages of tumors, and autophagy inhibition induces apoptosis of dormant cells [103]. Galectin-1 (Shikonin) inhibits JNK activation, a MAPK family member, and inhibits CRC autophagic flux to induce ROS accumulation and apoptosis in human CRC cells [104].

Regulation of autophagy and apoptosis in the treatment of CRC

Induction of cancer cell apoptosis is one of the important indicators for the evaluation of anti-tumor drugs that inhibit cancer cell growth [107]. Induction of apoptosis using compounds or pro-apoptotic agents is effective in reducing cancer spread [108]. Autophagy in cancer cells is a process that degrades damaged cellular organs or proteins in eukaryotic cells. In the prevention and treatment of cancer, autophagy is a potential target for the treatment of cancer [109] (Table 3). Bupivacaine plays a role in CRC treatment by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway. Bupivacaine inhibits Bcl-2 expression, promotes caspase-3 and Bax expression, and promotes apoptosis in CRC cells. It also decreases Beclin-1 expression, significantly increased the LC3B-II/LC3B-I ratio, decreases p62 expression, and promotes autophagy [110]. Pyrvinium pamoate (PP) inhibits CRC cell progression by inhibiting the PI3K/mTOR signaling pathway to induce apoptosis and autophagy [111]. Oleanolic acid (OA) is found to inhibit mTOR and up-regulate caspase-9, caspase-8, caspase-3, BAX, Beclin-1, LC3B-II, and ULK1 in an AMPK activation-dependent manner, inducing autophagy and apoptosis in CRC cells [112]. The above studies demonstrate that apoptosis and autophagy can be regulated simultaneously through signaling pathways, and different modulators have different effects on autophagy, but they all promote apoptosis. In addition, these studies did not focus on the interaction between autophagy and apoptosis, and it is of great potential to further investigate the promotion or antagonism of autophagy in regulating apoptosis. Studying the regulation of apoptosis by autophagy can provide new ideas for drug treatment of CRC.

Table 3.

Compounds regulate autophagy and apoptosis through signaling pathways in the treatment of CRC

| Name | Autophagy | Apoptosis | Signaling pathway | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bupivacaine | ↑ | ↑ | NF-κB | [110] |

| PP | ↑ | ↑ | PI3K/mTOR | [111] |

| OA | ↑ | ↑ | AKT/mTOR | [112] |

| Isoalantolactone | ↑ | ↑ | AKT/mTOR | [113] |

| Mitoxantrone | ↑ | ↑ | PI3K/AKT/mTOR | [114] |

| Libertellenone T | ↑ | ↑ | ROS/JNK | [115] |

| CbFeD | ↓ | ↑ | NF-κB | [116] |

| Ursolic acid | ↑ | ↑ | JNK | [117] |

| Pogostone | ↑ | ↑ | PI3K/AKT/mTOR | [118] |

| Chaetocochin J | ↑ | ↑ | AMPK | [119] |

| PI3K/AKT/mTOR | ||||

| STZ | ↑ | ↑ | AMPK | [120] |

| Tanshinone IIA | ↑ | ↑ | ROS/JNK | [121] |

| Celastrol | ↑ | ↑ | Nur77/ATG7 | [122] |

| MY-13 | ↑ | ↑ | SIRT3/Hsp90/AKT | [123] |

| AFE | ↑ | ↑ | AMPK/mTOR | [124] |

| D4476 | ↓ | ↑ | AKT/p-β-catenin | [125] |

| Quercus infectoria | ↑ | ↑ | AKT/mTOR | [126] |

| Xanthatin | ↑ | ↑ | ROS/XIAP | [127] |

| MJ—33 | ↑ | ↑ | Akt/mTOR | [106] |

| Zhonglu saponin II | ↑ | ↑ | PI3K/AKT/mTOR | [128] |

Summary and outlook

CRC is a common malignancy with high morbidity and mortality and is a health burden worldwide. In order to improve the treatment outcome of CRC, reduce patient suffering, and improve survival and prognosis, we must continuously improve the treatment options for CRC. Autophagy is an intracellular degradation process that is equivalent to the self-digestion of cells, and autophagy has a dual role in tumors. On the one hand, autophagy can inhibit tumor cell growth and invasion. On the other hand, it helps tumor cells survive stress stimulation, especially in the presence of defective apoptosis. Autophagy and apoptosis usually coexist, and autophagy is accompanied by apoptosis, and the regulation of autophagy on apoptosis deserves our further investigation.

In CRC, the crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis involves multiple signal transduction pathways and regulators, among which the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and AMPK/mTOR signaling pathways are important pathways regulating autophagy and apoptosis. Induction of autophagy or inhibition of apoptosis depends on the nature and duration of the stimulus or stress. Autophagy has been found to regulate apoptosis differently in response to different modulators. On the one hand, activation of autophagy-related signaling pathways promotes autophagy and apoptosis. Related experiments show that apoptosis is inhibited after the use of autophagy inhibitors, demonstrating that activated autophagy is positively correlated with apoptosis and could promote apoptosis through autophagy. Both have synergistic effects on the cytotoxic effects of CRC cells. On the other hand, autophagy inhibits the cytotoxic effect of apoptosis on CRC cells. Relevant studies show that activation of autophagy-related signaling pathways can stimulate the occurrence of autophagy and apoptosis. However, increased levels of apoptosis were found after the use of autophagy inhibitors or signaling pathway inhibitors. This demonstrates that while apoptosis activated by this compound inhibits CRC development, autophagy activated by this compound has an antagonistic effect on apoptosis. Autophagy and apoptosis can efficiently cooperate to induce CRC cell death and arrest CRC development. Autophagy can also attenuate apoptosis-induced cell death and alleviate the inhibitory effect of apoptosis on CRC development. Studies find that many compounds can regulate autophagy and apoptosis through related signals, but the interaction between autophagy and apoptosis has not been further elucidated. Therefore, it is important to deeply investigate how related modulators regulate autophagy and the relationship between autophagy and apoptosis.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Associate Professor Guojuan Wang and Associate Professor Wenyan Yu for their guidance on the paper.

Author contributions

Yuwei Yan: Writing—original draft, Conceptualization, Drawing figures. Guojuan Wang, Wenyan Yu: Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Min Guo, Xiudan Chen, Naicheng Zhu: Writing—review & editing. Nanxin Li, Chen Zhong: Resources, Drawing figures.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82160925; 82205221), Jiangxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No.20224BAB206097), Jiangxi University of Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Innovation Team Development Program (CXTD22011), and Young Foundation Talents in Chinese Medicine in Jiangxi Province (fourth batch) (2022-7).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cancer statistics, 2024—Siegel—2024—CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians—Wiley Online Library, (n.d.). https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.3322/caac.21820. Accessed 31 Mar 2024.

- 2.Han B, Zheng R, Zeng H, Wang S, Sun K, Chen R, Li L, Wei W, He J. Cancer incidence and mortality in China 2022. J Natl Cancer Center. 2024;4:47–53. 10.1016/j.jncc.2024.01.006. 10.1016/j.jncc.2024.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qi J, Li M, Wang L, Hu Y, Liu W, Long Z, Zhou Z, Yin P, Zhou M. National and subnational trends in cancer burden in China, 2005–20: an analysis of national mortality surveillance data. Lancet Pub Health. 2023;8:e943–55. 10.1016/S2468-2667(23)00211-6. 10.1016/S2468-2667(23)00211-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feng R-M, Zong Y-N, Cao S-M, Xu R-H. Current cancer situation in China: good or bad news from the 2018 global cancer statistics? Cancer Commun. 2019;39:22. 10.1186/s40880-019-0368-6. 10.1186/s40880-019-0368-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xia C, Dong X, Li H, Cao M, Sun D, He S, Yang F, Yan X, Zhang S, Li N, Chen W. Cancer statistics in China and United States, 2022: profiles, trends, and determinants. Chin Med J. 2022;135:584–90. 10.1097/CM9.0000000000002108. 10.1097/CM9.0000000000002108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eskelinen E-L. Autophagy: Supporting cellular and organismal homeostasis by self-eating. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2019;111:1–10. 10.1016/j.biocel.2019.03.010. 10.1016/j.biocel.2019.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cecconi F, Levine B. The role of autophagy in mammalian development: cell makeover rather than cell death. Dev Cell. 2008;15:344–57. 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.08.012. 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Debnath J, Gammoh N, Ryan KM. Autophagy and autophagy-related pathways in cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2023;24:560–75. 10.1038/s41580-023-00585-z. 10.1038/s41580-023-00585-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mizushima N, Levine B. Autophagy in human diseases. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1564–76. 10.1056/NEJMra2022774. 10.1056/NEJMra2022774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Onorati AV, Dyczynski M, Ojha R, Amaravadi RK. Targeting autophagy in cancer. Cancer. 2018;124:3307–18. 10.1002/cncr.31335. 10.1002/cncr.31335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gong C, Bauvy C, Tonelli G, Yue W, Deloménie C, Nicolas V, Zhu Y, Domergue V, Marin-Esteban V, Tharinger H, Delbos L, Gary-Gouy H, Morel A-P, Ghavami S, Song E, Codogno P, Mehrpour M. Beclin 1 and autophagy are required for the tumorigenicity of breast cancer stem-like/progenitor cells. Oncogene. 2013;32:2261–72. 10.1038/onc.2012.252. 10.1038/onc.2012.252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pagotto A, Pilotto G, Mazzoldi EL, Nicoletto MO, Frezzini S, Pastò A, Amadori A. Autophagy inhibition reduces chemoresistance and tumorigenic potential of human ovarian cancer stem cells. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:e2943–e2943. 10.1038/cddis.2017.327. 10.1038/cddis.2017.327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy JMM, Towers CG, Thorburn A. Targeting autophagy in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:528–42. 10.1038/nrc.2017.53. 10.1038/nrc.2017.53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khan SU, Fatima K, Aisha S, Malik F. Unveiling the mechanisms and challenges of cancer drug resistance. Cell Commun Signal. 2024;22:109. 10.1186/s12964-023-01302-1. 10.1186/s12964-023-01302-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kimmelman AC, White E. Autophagy and tumor metabolism. Cell Metab. 2017;25:1037–43. 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.04.004. 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The biochemistry of apoptosis | Nature, (n.d.). https://www.nature.com/articles/35037710. Accessed 14 June 2024).

- 17.Wong RSY. Apoptosis in cancer: from pathogenesis to treatment. J Exp Clin Cancer Res CR. 2011;30:87. 10.1186/1756-9966-30-87. 10.1186/1756-9966-30-87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou C, Li Y, Wang G, Niu W, Zhang J, Wang G, Zhao Q, Fan L. Enhanced SLP-2 promotes invasion and metastasis by regulating Wnt/β-catenin signal pathway in colorectal cancer and predicts poor prognosis. Pathol Res Pract. 2019;215:57–67. 10.1016/j.prp.2018.10.018. 10.1016/j.prp.2018.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen S, Chen W, Zhang X, Lin S, Chen Z. Overexpression of KiSS-1 reduces colorectal cancer cell invasion by downregulating MMP-9 via blocking PI3K/Akt/NF-κB signal pathway. Int J Oncol. 2016;48:1391–8. 10.3892/ijo.2016.3368. 10.3892/ijo.2016.3368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang W-J, Luo C, Huang C, Pu F-Q, Zhu J-F, Zhu Z-M. PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β signal pathway is involved in P2X7 receptor-induced proliferation and EMT of colorectal cancer cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2021;899:174041. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.174041. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.174041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan K, Xie Y. LncRNA FOXC2-AS1 enhances FOXC2 mRNA stability to promote colorectal cancer progression via activation of Ca2+-FAK signal pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:434. 10.1038/s41419-020-2633-7. 10.1038/s41419-020-2633-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang Y, Li J, Lei W, Wang H, Ni Y, Liu Y, Yan H, Tian Y, Wang Z, Yang Z, Yang S, Yang Y, Wang Q. CXCL12-CXCR4/CXCR7 axis in cancer: from mechanisms to clinical applications. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19:3341–59. 10.7150/ijbs.82317. 10.7150/ijbs.82317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gump JM, Staskiewicz L, Morgan MJ, Bamberg A, Riches DWH, Thorburn A. Autophagy variation within a cell population determines cell fate through selective degradation of Fap-1. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:47–54. 10.1038/ncb2886. 10.1038/ncb2886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie Q, Liu Y, Li X. The interaction mechanism between autophagy and apoptosis in colon cancer. Transl Oncol. 2020;13:100871. 10.1016/j.tranon.2020.100871. 10.1016/j.tranon.2020.100871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khan SU, Fatima K, Malik F. Understanding the cell survival mechanism of anoikis-resistant cancer cells during different steps of metastasis. Clin Exp Metastas. 2022;39:715–26. 10.1007/s10585-022-10172-9. 10.1007/s10585-022-10172-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mizushima N, Komatsu M. Autophagy: renovation of cells and tissues. Cell. 2011;147:728–41. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.026. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Du Y-X, Mamun AA, Lyu A-P, Zhang H-J. Natural compounds targeting the autophagy pathway in the treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:7310. 10.3390/ijms24087310. 10.3390/ijms24087310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rabinowitz JD, White E. Autophagy and metabolism. Science. 2010;330:1344–8. 10.1126/science.1193497. 10.1126/science.1193497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mizushima N. Autophagy: process and function. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2861–73. 10.1101/gad.1599207. 10.1101/gad.1599207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nie T, Zhu L, Yang Q. The classification and basic processes of autophagy. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2021;1208:3–16. 10.1007/978-981-16-2830-6_1. 10.1007/978-981-16-2830-6_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamamoto H, Matsui T. Molecular mechanisms of macroautophagy, microautophagy, and chaperone-mediated autophagy. J Nippon Med Sch. 2023. 10.1272/jnms.JNMS.2024_91-102. 10.1272/jnms.JNMS.2024_91-102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mijaljica D, Prescott M, Devenish RJ. The intriguing life of autophagosomes. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:3618–35. 10.3390/ijms13033618. 10.3390/ijms13033618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galluzzi L, Pietrocola F, Levine B, Kroemer G. Metabolic control of autophagy. Cell. 2014;159:1263–76. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.006. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Funderburk SF, Wang QJ, Yue Z. The Beclin 1–VPS34 complex—at the crossroads of autophagy and beyond. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:355–62. 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.03.002. 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nair U, Klionsky DJ. Molecular mechanisms and regulation of specific and nonspecific autophagy pathways in yeast. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:41785–8. 10.1074/jbc.R500016200. 10.1074/jbc.R500016200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Itakura E, Kishi C, Inoue K, Mizushima N. Beclin 1 forms two distinct phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complexes with mammalian Atg14 and UVRAG. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:5360–72. 10.1091/mbc.e08-01-0080. 10.1091/mbc.e08-01-0080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liang XH, Jackson S, Seaman M, Brown K, Kempkes B, Hibshoosh H, Levine B. Induction of autophagy and inhibition of tumorigenesis by beclin 1. Nature. 1999;402:672–6. 10.1038/45257. 10.1038/45257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hara T, Takamura A, Kishi C, Iemura S, Natsume T, Guan J-L, Mizushima N. FIP200, a ULK-interacting protein, is required for autophagosome formation in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:497–510. 10.1083/jcb.200712064. 10.1083/jcb.200712064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274–93. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu K, Liu P, Wei W. mTOR signaling in tumorigenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) Rev Cancer. 2014;1846:638–54. 10.1016/j.bbcan.2014.10.007. 10.1016/j.bbcan.2014.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu L, McPhee CK, Zheng L, Mardones GA, Rong Y, Peng J, Mi N, Zhao Y, Liu Z, Wan F, Hailey DW, Oorschot V, Klumperman J, Baehrecke EH, Lenardo MJ. Termination of autophagy and reformation of lysosomes regulated by mTOR. Nature. 2010;465:942–6. 10.1038/nature09076. 10.1038/nature09076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jung CH, Jun CB, Ro S-H, Kim Y-M, Otto NM, Cao J, Kundu M, Kim D-H. ULK-Atg13-FIP200 complexes mediate mTOR signaling to the autophagy machinery. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:1992–2003. 10.1091/mbc.e08-12-1249. 10.1091/mbc.e08-12-1249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang J, Davis S, Zhu M, Miller EA, Ferro-Novick S. Autophagosome formation: where the secretory and autophagy pathways meet. Autophagy. 2017;13:973–4. 10.1080/15548627.2017.1287657. 10.1080/15548627.2017.1287657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tooze SA, Yoshimori T. The origin of the autophagosomal membrane. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:831–5. 10.1038/ncb0910-831. 10.1038/ncb0910-831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nakatogawa H, Suzuki K, Kamada Y, Ohsumi Y. Dynamics and diversity in autophagy mechanisms: lessons from yeast. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:458–67. 10.1038/nrm2708. 10.1038/nrm2708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaur J, Debnath J. Autophagy at the crossroads of catabolism and anabolism. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16:461–72. 10.1038/nrm4024. 10.1038/nrm4024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mejlvang J, Olsvik H, Svenning S, Bruun J-A, Abudu YP, Larsen KB, Brech A, Hansen TE, Brenne H, Hansen T, Stenmark H, Johansen T. Starvation induces rapid degradation of selective autophagy receptors by endosomal microautophagy. J Cell Biol. 2018;217:3640–55. 10.1083/jcb.201711002. 10.1083/jcb.201711002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sahu R, Kaushik S, Clement CC, Cannizzo ES, Scharf B, Follenzi A, Potolicchio I, Nieves E, Cuervo AM, Santambrogio L. Microautophagy of cytosolic proteins by late endosomes. Dev Cell. 2011;20:131–9. 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.12.003. 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leidal AM, Huang HH, Marsh T, Solvik T, Zhang D, Ye J, Kai F, Goldsmith J, Liu JY, Huang Y-H, Monkkonen T, Vlahakis A, Huang EJ, Goodarzi H, Yu L, Wiita AP, Debnath J. The LC3-conjugation machinery specifies the loading of RNA-binding proteins into extracellular vesicles. Nat Cell Biol. 2020;22:187–99. 10.1038/s41556-019-0450-y. 10.1038/s41556-019-0450-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang L, Klionsky DJ, Shen H-M. The emerging mechanisms and functions of microautophagy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2023;24:186–203. 10.1038/s41580-022-00529-z. 10.1038/s41580-022-00529-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schuck S. Microautophagy—distinct molecular mechanisms handle cargoes of many sizes. J Cell Sci. 2020. 10.1242/jcs.246322. 10.1242/jcs.246322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chiang H-L, Terlecky SR, Plant CP, Dice JF. A role for a 70-kilodalton heat shock protein in lysosomal degradation of intracellular proteins. Science. 1989;246:382–5. 10.1126/science.2799391. 10.1126/science.2799391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bandyopadhyay U, Kaushik S, Varticovski L, Cuervo AM. The chaperone-mediated autophagy receptor organizes in dynamic protein complexes at the lysosomal membrane. Mol Cell Biol. 2008. 10.1128/MCB.02070-07. 10.1128/MCB.02070-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Agarraberes FA, Terlecky SR, Dice JF. An intralysosomal hsp70 is required for a selective pathway of lysosomal protein degradation. J Cell Biol. 1997. 10.1083/jcb.137.4.825. 10.1083/jcb.137.4.825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Salvador N, Aguado C, Horst M, Knecht E. Import of a cytosolic protein into lysosomes by chaperone-mediated autophagy depends on its folding state. J Biol Chemy. 2000. 10.1074/jbc.M001394200. 10.1074/jbc.M001394200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Madeo F, Tavernarakis N, Kroemer G. Can autophagy promote longevity? Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:842–6. 10.1038/ncb0910-842. 10.1038/ncb0910-842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Matsuzawa-Ishimoto Y, Hwang S, Cadwell K. Autophagy and inflammation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2018;36:73–101. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042617-053253. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042617-053253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cadwell K. Crosstalk between autophagy and inflammatory signalling pathways: balancing defence and homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:661–75. 10.1038/nri.2016.100. 10.1038/nri.2016.100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Klionsky DJ, Petroni G, Amaravadi RK, Baehrecke EH, Ballabio A, Boya P, Bravo-San Pedro JM, Cadwell K, Cecconi F, Choi AMK, Choi ME, Chu CT, Codogno P, Colombo MI, Cuervo AM, Deretic V, Dikic I, Elazar Z, Eskelinen E-L, Fimia GM, Gewirtz DA, Green DR, Hansen M, Jäättelä M, Johansen T, Juhász G, Karantza V, Kraft C, Kroemer G, Ktistakis NT, Kumar S, Lopez-Otin C, Macleod KF, Madeo F, Martinez J, Meléndez A, Mizushima N, Münz C, Penninger JM, Perera RM, Piacentini M, Reggiori F, Rubinsztein DC, Ryan KM, Sadoshima J, Santambrogio L, Scorrano L, Simon H-U, Simon AK, Simonsen A, Stolz A, Tavernarakis N, Tooze SA, Yoshimori T, Yuan J, Yue Z, Zhong Q, Galluzzi L, Pietrocola F. Autophagy in major human diseases. EMBO J. 2021;40: e108863. 10.15252/embj.2021108863. 10.15252/embj.2021108863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Feng Y, He D, Yao Z, Klionsky DJ. The machinery of macroautophagy. Cell Res. 2014;24:24–41. 10.1038/cr.2013.168. 10.1038/cr.2013.168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cao Z, Zhang H, Cai X, Fang W, Chai D, Wen Y, Chen H, Chu F, Zhang Y. Luteolin promotes cell apoptosis by inducing autophagy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;43:1803–12. 10.1159/000484066. 10.1159/000484066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xia H, Green DR, Zou W. Autophagy in tumour immunity and therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2021;21:281–97. 10.1038/s41568-021-00344-2. 10.1038/s41568-021-00344-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang ZJ, Chee CE, Huang S, Sinicrope FA. The role of autophagy in cancer: therapeutic implications. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:1533–41. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0047. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fang C, Weng T, Hu S, Yuan Z, Xiong H, Huang B, Cai Y, Li L, Fu X. IFN-γ-induced ER stress impairs autophagy and triggers apoptosis in lung cancer cells. Oncoimmunology. 2021;10:1962591. 10.1080/2162402X.2021.1962591. 10.1080/2162402X.2021.1962591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xing Y, Wei X, Wang M-M, Liu Y, Sui Z, Wang X, Zhang Y, Fei Y-H, Jiang Y, Lu C, Zhang P, Chen R, Liu N, Wu M, Ding L, Wang Y, Guo F, Cao J-L, Qi J, Wang W. Stimulating TRPM7 suppresses cancer cell proliferation and metastasis by inhibiting autophagy. Cancer Lett. 2022;525:179–97. 10.1016/j.canlet.2021.10.043. 10.1016/j.canlet.2021.10.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Song J, Guo X, Xie X, Zhao X, Li D, Deng W, Song Y, Shen F, Wu M, Wei L. Autophagy in hypoxia protects cancer cells against apoptosis induced by nutrient deprivation through a Beclin1-dependent way in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112:3406–20. 10.1002/jcb.23274. 10.1002/jcb.23274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Manzoor S, Muhammad JS, Maghazachi AA, Hamid Q. Autophagy: a versatile player in the progression of colorectal cancer and drug resistance. Front Oncol. 2022;12:924290. 10.3389/fonc.2022.924290. 10.3389/fonc.2022.924290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.IJMS | Free Full-Text | The Roles of Autophagy in Cancer, (n.d.). https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/19/11/3466. Accessed 13 Aug 2023.

- 69.Maiuri MC, Zalckvar E, Kimchi A, Kroemer G. Self-eating and self-killing: crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:741–52. 10.1038/nrm2239. 10.1038/nrm2239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wei M-F, Chen M-W, Chen K-C, Lou P-J, Lin SY-F, Hung S-C, Hsiao M, Yao C-J, Shieh M-J. Autophagy promotes resistance to photodynamic therapy-induced apoptosis selectively in colorectal cancer stem-like cells. Autophagy. 2014;10:1179–92. 10.4161/auto.28679. 10.4161/auto.28679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cheng X, Feng H, Wu H, Jin Z, Shen X, Kuang J, Huo Z, Chen X, Gao H, Ye F, Ji X, Jing X, Zhang Y, Zhang T, Qiu W, Zhao R. Targeting autophagy enhances apatinib-induced apoptosis via endoplasmic reticulum stress for human colorectal cancer. Cancer Lett. 2018;431:105–14. 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.05.046. 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.05.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Si Y, Yang Z, Ge Q, Yu L, Yao M, Sun X, Ren Z, Ding C. Long non-coding RNA Malat1 activated autophagy, hence promoting cell proliferation and inhibiting apoptosis by sponging miR-101 in colorectal cancer. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2019;24:50. 10.1186/s11658-019-0175-8. 10.1186/s11658-019-0175-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Song F, Li L, Liang D, Zhuo Y, Wang X, Dai H. Knockdown of long noncoding RNA urothelial carcinoma associated 1 inhibits colorectal cancer cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis via modulating autophagy. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:7420–34. 10.1002/jcp.27500. 10.1002/jcp.27500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang H, Tang J, Li C, Kong J, Wang J, Wu Y, Xu E, Lai M. MiR-22 regulates 5-FU sensitivity by inhibiting autophagy and promoting apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2015;356:781–90. 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.10.029. 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li X, Tian R, Liu L, Wang L, He D, Cao K, Ma JK, Huang C. Andrographolide enhanced radiosensitivity by downregulating glycolysis via the inhibition of the PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling pathway in HCT116 colorectal cancer cells. J Int Med Res. 2020;48:300060520946169. 10.1177/0300060520946169. 10.1177/0300060520946169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sun J, Zhao X, Jiang H, Yang T, Li D, Yang X, Jia A, Ma Y, Qian Z. ARHGAP9 inhibits colorectal cancer cell proliferation, invasion and EMT via targeting PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Tissue Cell. 2022;77:101817. 10.1016/j.tice.2022.101817. 10.1016/j.tice.2022.101817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li P, Zhou D, Chen D, Cheng Y, Chen Y, Lin Z, Zhang X, Huang Z, Cai J, Huang W, Lin Y, Ke H, Long J, Zou Y, Ye S, Lan P. Tumor-secreted IFI35 promotes proliferation and cytotoxic activity of CD8+ T cells through PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in colorectal cancer. J Biomed Sci. 2023;30:47. 10.1186/s12929-023-00930-6. 10.1186/s12929-023-00930-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Botti J, Djavaheri-Mergny M, Pilatte Y, Codogno P. Autophagy signaling and the cogwheels of cancer. Autophagy. 2006;2:67–73. 10.4161/auto.2.2.2458. 10.4161/auto.2.2.2458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Huang Y-H, Sun Y, Huang F-Y, Li Y-N, Wang C-C, Mei W-L, Dai H-F, Tan G-H, Huang C. Toxicarioside O induces protective autophagy in a sirtuin-1-dependent manner in colorectal cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8:52783–91. 10.18632/oncotarget.17189. 10.18632/oncotarget.17189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yang H-L, Liu H-W, Shrestha S, Thiyagarajan V, Huang H-C, Hseu Y-C. Antrodia salmonea induces apoptosis and enhances cytoprotective autophagy in colon cancer cells. Aging. 2021;13:15964–89. 10.18632/aging.203019. 10.18632/aging.203019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jin S, White E. Role of autophagy in cancer: management of metabolic stress. Autophagy. 2007;3:28–31. 10.4161/auto.3269. 10.4161/auto.3269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Moafian Z, Maghrouni A, Soltani A, Hashemy SI. Cross-talk between non-coding RNAs and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in colorectal cancer. Mol Biol Rep. 2021;48:4797–811. 10.1007/s11033-021-06458-y. 10.1007/s11033-021-06458-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rhodamine-RCA in vivo labeling guided laser capture microdissection of cancer functional angiogenic vessels in a murine squamous cell carcinoma mouse model—PubMed, (n.d.). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16457726/. Accessed 30 July 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 84.Ma Z, Lou S, Jiang Z. PHLDA2 regulates EMT and autophagy in colorectal cancer via the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Aging. 2020;12:7985–8000. 10.18632/aging.103117. 10.18632/aging.103117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhang R, Yu Q, Lu W, Shen J, Zhou D, Wang Y, Gao S, Wang Z. <p>Grape seed procyanidin B2 promotes the autophagy and apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells via regulating PI3K/Akt signaling pathway</p>. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:4109–18. 10.2147/OTT.S195615. 10.2147/OTT.S195615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Won S-J, Yen C-H, Liu H-S, Wu S-Y, Lan S-H, Jiang-Shieh Y-F, Lin C-N, Su C-L. Justicidin A-induced autophagy flux enhances apoptosis of human colorectal cancer cells via class III PI3K and Atg5 pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2015;230:930–46. 10.1002/jcp.24825. 10.1002/jcp.24825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tan X-P, He Y, Huang Y-N, Zheng C-C, Li J-Q, Liu Q-W, He M-L, Li B, Xu W-W. Lomerizine 2HCl inhibits cell proliferation and induces protective autophagy in colorectal cancer via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. MedComm. 2020;2(2021):453–66. 10.1002/mco2.83. 10.1002/mco2.83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhang C, Wang Y, Zhou D, Zhu M, Lv Y, Hao X, Qu C, Chen Y, Gu W, Wu B, Chen P, Zhao Z. A recombinant Chinese measles virus vaccine strain rMV-Hu191 inhibits human colorectal cancer growth through inducing autophagy and apoptosis regulating by PI3K/AKT pathway. Transl Oncol. 2021;14:101091. 10.1016/j.tranon.2021.101091. 10.1016/j.tranon.2021.101091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fan X-J, Wang Y, Wang L, Zhu M. Salidroside induces apoptosis and autophagy in human colorectal cancer cells through inhibition of PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Oncol Rep. 2016;36:3559–67. 10.3892/or.2016.5138. 10.3892/or.2016.5138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhu M, Zhang P, Jiang M, Yu S, Wang L. Myricetin induces apoptosis and autophagy by inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signalling in human colon cancer cells. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2020;20:209. 10.1186/s12906-020-02965-w. 10.1186/s12906-020-02965-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yang X, Niu B, Wang L, Chen M, Kang X, Wang L, Ji Y, Zhong J. Autophagy inhibition enhances colorectal cancer apoptosis induced by dual phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor NVP-BEZ235. Oncol Lett. 2016;12:102–6. 10.3892/ol.2016.4590. 10.3892/ol.2016.4590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wang J, Liang D, Zhang X-P, He C-F, Cao L, Zhang S-Q, Xiao X, Li S-J, Cao Y-X. Novel PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling inhibitor, W922, prevents colorectal cancer growth via the regulation of autophagy. Int J Oncol. 2021;58:70–82. 10.3892/ijo.2020.5151. 10.3892/ijo.2020.5151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chen M-B, Zhang Y, Wei M-X, Shen W, Wu X-Y, Yao C, Lu P-H. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) mediates plumbagin-induced apoptosis and growth inhibition in cultured human colon cancer cells. Cell Signal. 2013;25:1993–2002. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.05.026. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.05.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kim YC, Guan K-L. mTOR: a pharmacologic target for autophagy regulation. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:25–32. 10.1172/JCI73939. 10.1172/JCI73939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bu H, Liu D, Zhang G, Chen L, Song Z. <p>AMPK/mTOR/ULK1 Axis-mediated pathway participates in apoptosis and autophagy induction by oridonin in colon cancer DLD-1 Cells</p>. Onco Targets Ther. 2020;13:8533–45. 10.2147/OTT.S262022. 10.2147/OTT.S262022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Xiang X, Tian Y, Hu J, Xiong R, Bautista M, Deng L, Yue Q, Li Y, Kuang W, Li J, Liu K, Yu C, Feng G. Fangchinoline exerts anticancer effects on colorectal cancer by inducing autophagy via regulation AMPK/mTOR/ULK1 pathway. Biochem Pharmacol. 2021;186:114475. 10.1016/j.bcp.2021.114475. 10.1016/j.bcp.2021.114475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yu H, Huang Y, Ge Y, Hong X, Lin X, Tang K, Wang Q, Yang Y, Sun W, Huang Y, Luo H. Selenite-induced ROS/AMPK/FoxO3a/GABARAPL-1 signaling pathway modulates autophagy that antagonize apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. Discov Oncol. 2021;12:35. 10.1007/s12672-021-00427-4. 10.1007/s12672-021-00427-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dhillon AS, Hagan S, Rath O, Kolch W. MAP kinase signalling pathways in cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:3279–90. 10.1038/sj.onc.1210421. 10.1038/sj.onc.1210421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sui X, Kong N, Ye L, Han W, Zhou J, Zhang Q, He C, Pan H. p38 and JNK MAPK pathways control the balance of apoptosis and autophagy in response to chemotherapeutic agents. Cancer Lett. 2014;344:174–9. 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.11.019. 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kim EK, Choi E-J. Pathological roles of MAPK signaling pathways in human diseases. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1802;2010:396–405. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.12.009. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Functions of the MAPK family in vertebrate-development - PubMed, (n.d.). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16949582/. Accessed 13 June 2024.

- 102.Mitogen-activated protein kinases in apoptosis regulation—PubMed, (n.d.). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15077147/. Accessed 14 June 2024.

- 103.Tian X, He Y, Qi L, Liu D, Zhou D, Liu Y, Gong W, Han Z, Xia Y, Li H, Wang J, Zhu K, Chen L, Guo H, Zhao Q. Autophagy inhibition contributes to apoptosis of PLK4 downregulation-induced dormant cells in colorectal cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19:2817–34. 10.7150/ijbs.79949. 10.7150/ijbs.79949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhang N, Peng F, Wang Y, Yang L, Wu F, Wang X, Ye C, Han B, He G. Shikonin induces colorectal carcinoma cells apoptosis and autophagy by targeting galectin-1/JNK signaling axis. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16:147–61. 10.7150/ijbs.36955. 10.7150/ijbs.36955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Deng H, Huang L, Liao Z, Liu M, Li Q, Xu R. Itraconazole inhibits the Hedgehog signaling pathway thereby inducing autophagy-mediated apoptosis of colon cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:1–15. 10.1038/s41419-020-02742-0. 10.1038/s41419-020-02742-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ha H-A, Chiang J-H, Tsai F-J, Bau D-T, Juan Y-N, Lo Y-H, Hour M-J, Yang J-S. Novel quinazolinone MJ-33 induces AKT/mTOR-mediated autophagy-associated apoptosis in 5FU-resistant colorectal cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2021;45:680–92. 10.3892/or.2020.7882. 10.3892/or.2020.7882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dynamic Regulation of the 26S Proteasome: From Synthesis to Degradation—PubMed, (n.d.). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31231659/. Accessed 13 June 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 108.Mohammad RM, Muqbil I, Lowe L, Yedjou C, Hsu H-Y, Lin L-T, Siegelin MD, Fimognari C, Kumar NB, Dou QP, Yang H, Samadi AK, Russo GL, Spagnuolo C, Ray SK, Chakrabarti M, Morre JD, Coley HM, Honoki K, Fujii H, Georgakilas AG, Amedei A, Niccolai E, Amin A, Ashraf SS, Helferich WG, Yang X, Boosani CS, Guha G, Bhakta D, Ciriolo MR, Aquilano K, Chen S, Mohammed SI, Keith WN, Bilsland A, Halicka D, Nowsheen S, Azmi AS. Broad targeting of resistance to apoptosis in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2015;35(Suppl):S78–103. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2015.03.001. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2015.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hauseman ZJ, Harvey EP, Newman CE, Wales TE, Bucci JC, Mintseris J, Schweppe DK, David L, Fan L, Cohen DT, Herce HD, Mourtada R, Ben-Nun Y, Bloch NB, Hansen SB, Wu H, Gygi SP, Engen JR, Walensky LD. Homogeneous oligomers of pro-apoptotic BAX reveal structural determinants of mitochondrial membrane permeabilization. Mol Cell. 2020;79:68-83.e7. 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.05.029. 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.05.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Liu B, Yan X, Hou Z, Zhang L, Zhang D. Impact of Bupivacaine on malignant proliferation, apoptosis and autophagy of human colorectal cancer SW480 cells through regulating NF-κB signaling path. Bioengineered. 2021;12:2723–33. 10.1080/21655979.2021.1937911. 10.1080/21655979.2021.1937911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zheng W, Chen K, Lv Y, Lao W, Zhu H. Pyrvinium Pamoate Induces Cell apoptosis and autophagy in colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2024;44:1193–9. 10.21873/anticanres.16914. 10.21873/anticanres.16914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hu C, Cao Y, Li P, Tang X, Yang M, Gu S, Xiong K, Li T, Xiao T. Oleanolic acid induces autophagy and apoptosis via the AMPK-mTOR signaling pathway in colon cancer. J Oncol. 2021;2021:8281718. 10.1155/2021/8281718. 10.1155/2021/8281718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chen J-S, Chiu S-C, Huang S-Y, Chang S-F, Liao K-F. Isolinderalactone induces apoptosis, autophagy, cell cycle arrest and MAPK activation through ROS-mediated signaling in colorectal cancer cell lines. Int J Mol Sci. 2023. 10.3390/ijms241814246. 10.3390/ijms241814246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zhu L-L, Shi J-J, Guo Y-D, Yang C, Wang R-L, Li S-S, Gan D-X, Ma P-X, Li J-Q, Su H-C. NUCKS1 promotes the progression of colorectal cancer via activating PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Neoplasma. 2023;70:272–86. 10.4149/neo_2023_221107N1088. 10.4149/neo_2023_221107N1088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Gamage CDB, Kim J-H, Yang Y, Taş İ, Park S-Y, Zhou R, Pulat S, Varlı M, Hur J-S, Nam S-J, Kim H. Libertellenone T, a novel compound isolated from Endolichenic Fungus, induces G2/M phase arrest apoptosis, and autophagy by activating the ROS/JNK pathway in colorectal cancer cells. Cancers. 2023;15:489. 10.3390/cancers15020489. 10.3390/cancers15020489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Luan Y, Li Y, Zhu L, Zheng S, Mao D, Chen Z, Cao Y. Codonopis bulleynana Forest ex Diels inhibits autophagy and induces apoptosis of colon cancer cells by activating the NF-κB signaling pathway. Int J Mol Med. 2018;41:1305–14. 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3337. 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Xavier CPR, Lima CF, Pedro DFN, Wilson JM, Kristiansen K, Pereira-Wilson C. Ursolic acid induces cell death and modulates autophagy through JNK pathway in apoptosis-resistant colorectal cancer cells. J Nutr Biochem. 2013;24:706–12. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2012.04.004. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2012.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Cao Z-X, Yang Y-T, Yu S, Li Y-Z, Wang W-W, Huang J, Xie X-F, Xiong L, Lei S, Peng C. Pogostone induces autophagy and apoptosis involving PI3K/Akt/mTOR axis in human colorectal carcinoma HCT116 cells. J Ethnopharmacol. 2017;202:20–7. 10.1016/j.jep.2016.07.028. 10.1016/j.jep.2016.07.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Hu S, Yin J, Yan S, Hu P, Huang J, Zhang G, Wang F, Tong Q, Zhang Y. Chaetocochin J, an epipolythiodioxopiperazine alkaloid, induces apoptosis and autophagy in colorectal cancer via AMPK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways. Bioorg Chem. 2021;109:104693. 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.104693. 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.104693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Yang Y, Jin Y, Yin L, Liu P, Zhu L, Gao H. Sertaconazole nitrate targets IDO1 and regulates the MAPK signaling pathway to induce autophagy and apoptosis in CRC cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2023;942:175515. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2023.175515. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2023.175515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Qian J, Cao Y, Zhang J, Li L, Wu J, Yu J, Huo J. Tanshinone IIA alleviates the biological characteristics of colorectal cancer via activating the ROS/JNK signaling pathway. Anti-Cancer Agents Med Chem. 2023;23:227–36. 10.2174/1871520622666220421093430. 10.2174/1871520622666220421093430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Zhang W, Wu Z, Qi H, Chen L, Wang T, Mao X, Shi H, Chen H, Zhong M, Shi X, Wang X, Li Q. Celastrol upregulated ATG7 triggers autophagy via targeting Nur77 in colorectal cancer. Phytomedicine. 2022;104:154280. 10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154280. 10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Mou Y, Chen Y, Fan Z, Ye L, Hu B, Han B, Wang G. Discovery of a novel small-molecule activator of SIRT3 that inhibits cell proliferation and migration by apoptosis and autophagy-dependent cell death pathways in colorectal cancer. Bioorg Chem. 2024;146:107327. 10.1016/j.bioorg.2024.107327. 10.1016/j.bioorg.2024.107327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Dutta N, Pemmaraju DB, Ghosh S, Ali A, Mondal A, Majumder C, Nelson VK, Mandal SC, Misra AK, Rengan AK, Ravichandiran V, Che C-T, Gurova KV, Gudkov AV, Pal M. Alkaloid-rich fraction of Ervatamia coronaria sensitizes colorectal cancer through modulating AMPK and mTOR signalling pathways. J Ethnopharmacol. 2022;283:114666. 10.1016/j.jep.2021.114666. 10.1016/j.jep.2021.114666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Behrouj H, Seghatoleslam A, Mokarram P, Ghavami S. Effect of casein kinase 1α inhibition on autophagy flux and the AKT/phospho-β-catenin (S552) axis in HCT116, a RAS-mutated colorectal cancer cell line. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2021;99:284–93. 10.1139/cjpp-2020-0449. 10.1139/cjpp-2020-0449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Zhang H, Wang Y, Liu J, Kuerban K, Li J, Iminjan M, Ye L. Traditional Uyghur medicine Quercus infectoria galls water extract triggers apoptosis and autophagic cell death in colorectal cancer cells. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2020;20:371. 10.1186/s12906-020-03167-0. 10.1186/s12906-020-03167-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Geng Y, Zhang L, Wang G-Y, Feng X-J, Chen Z-L, Jiang L, Shen A-Z. Xanthatin mediates G(2)/M cell cycle arrest, autophagy and apoptosis via ROS/XIAP signaling in human colon cancer cells. Nat Prod Res. 2020;34:2616–20. 10.1080/14786419.2018.1544976. 10.1080/14786419.2018.1544976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Li J-K, Sun H-T, Jiang X-L, Chen Y-F, Zhang Z, Wang Y, Chen W-Q, Zhang Z, Sze SCW, Zhu P-L, Yung KKL. Polyphyllin II induces protective autophagy and apoptosis via inhibiting PI3K/AKT/mTOR and STAT3 signaling in colorectal cancer cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:11890. 10.3390/ijms231911890. 10.3390/ijms231911890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.