Abstract

This study investigates the binding affinity and interactions of the Furin enzyme with two inhibitors, Naphthofluorescein and decanoyl-RVKR-chloromethylketone (CMK), using molecular docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Molecular docking results showed binding affinities of − 9.18 kcal/mol for CMK and − 5.39 kcal/mol for Naphthofluorescein. To further understand the stability and conformational changes of these complexes, MD simulations were performed. Despite CMK’s favorable docking score, MD simulations revealed that its binding interactions at the Furin-active site were unstable, with significant changes observed during the simulation. In contrast, Naphthofluorescein maintained strong and stable interactions throughout the MD simulation, as confirmed by RMSD and RMSF analyses. The binding-free-energy analysis also supported the stability of Naphthofluorescein. These findings indicate that Naphthofluorescein exhibits greater stability and binding affinity as a Furin inhibitor compared to CMK. The results of this in-silico study suggest that Naphthofluorescein, along with CMK, holds the potential for repurposing as a treatment for COVID-19, subject to further validation through clinical studies.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Spike protein, Furin, Repurposing drugs, MD simulation, Binding-free energy

Introduction

In late 2019 the novel human coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-Corona Virus 2) was detected in Wuhan, China; which is an urgent public health emergency and it is creating a severe impact on universal health (Cheng et al. 2020). COVID-19 is a worldwide pandemic disease that causes high death rates. To date, there is no approved effective drug available to treat COVID patients. As per reports, this virus changes its structure and emerges as a variety of variants in different countries. This is a very difficult situation for people who suffer from low immunity power. To escape from this critical situation, new drugs to be designed and it is much needed to treat the various targets of the virus as well as host cells. The Furin-like cleavage site is present in the spike protein (682–689 amino-acid residues) of SARS-CoV-2, which plays an important role in the mechanism of the virus entering the host cell (Duan et al. 2020; Hoffmann et al. 2020). Furin protease also relates to the calcium-dependent prohormone/proprotein convertase (PCs) family, these are widely expressed in humans and its range is notably elevated in lung cystic fibrosis (Henrich et al. 2003; Ornatowski et al. 2007; Dahms et al. 2016; Vankadari 2020) and it is also known for cleaving different viral-envelope glycoproteins such as influenza and HIV by intensifying the fusion the viral protein with the membrane of the host cell (Hallenberger et al. 1992; Follis et al. 2006; Schneck et al. 2020). Reported Furin crystal structure studies states that His194, Asn295, and Ser368 are the catalytic site residues which includes the conformational changes of the protein (Dahms et al. 2016).

Both MERS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins have a Furin-cleavage site at the S1/S2 intersection promotes viral entry into lung cells, and the cleavage site contributes to viral pathogenesis in SARS-CoV-2 animal models (Zhou et al. 2020; Johnson et al. 2021; Peacock et al. 2021; Wu and Zhao 2021). In the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, the Furin-cleavage site mediates syncytium formation and it is suppressed by specific Furin inhibitors (Wang et al. 2023; Reuter et al. 2023). Ya-Wen Cheng et al (2020) reported that the cleavage and the syncytium are eradicated by hospitalization with decanoyl-RVKR-chloromethylketone (CMK) and Naphthofluorescein which are the Furin inhibitors (Coppola et al. 2008; Remacle et al. 2010; Imran et al. 2019). These two inhibitors show the antiviral reactions on SARS-CoV-2 infected cells by reducing the production of viruses and cytopathic effects (Cheng et al. 2020; Jiang et al. 2024). The latest work examined the inhibition assays for Furin using inhibitors including Naphthofluorescein, CMK, hexa-D-arginine amide, and SSM3 trifluoroacetate. The results of the study demonstrated that Naphthofluorescein could prevent the cleavage of the Furin protein (Yu et al. 2024). To comprehend the structural binding nature of the inhibitors with the Furin-active site, we conducted binding-free-energy calculations, molecular docking, and MD simulations in this study. This in-silico work allowed for the prediction of the binding site itself as well as an analysis of the dynamic properties of the inhibitor-Furin docked complex. The study’s findings make it possible to comprehend how these tiny molecules are inhibited by Furin, which is essential to move on with additional clinical research.

Materials and methods

Protein and ligands preparation

The crystal structure of the Furin protein was downloaded from the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 5JXG) to prepare the Furin target to perform Induced Fit Docking (IFD) simulation (Berman et al. 2002). Before IFD, the protein was prepared with a protein preparation wizard module incorporated into the Schrödinger package, further, the structure was optimized and minimized with the OPLS4 force field (Sastry et al. 2013; Lu et al. 2021). Both Furin inhibitors (decanoyl-RVKR-chloromethylketone (CMK) and Naphthofluorescein) are downloaded from the PubChem database in SDF format (Kim et al. 2021). Ligand molecules were neutralized and prepared for docking using the Epik program on the LigPrep module which is included in the Schrödinger Maestro application (Shelley et al. 2007; Schrödinger 2020).

Induced fit docking

Molecular docking simulation was performed for Furin with its inhibitors using the IFD method with extra precision (XP) mode (Sherman et al. 2006). In IFD, the receptor can alter the binding-site conformations to build the inhibitor-Furin complex. Before the docking process, to find the best binding site of the Furin, the SiteMap program was performed which allowed us to predict the best binding site from the SiteMap results (Halgren 2007). The IFD result gives different conformers of both inhibitors with the active site of Furin protein.

Molecular dynamics simulation and binding-free-energy calculation

From the IFD results, the best conformers of inhibitors were identified based on their binding energy and intermolecular interactions with the Furin enzyme. The MD simulations were performed for the selected complexes of each molecule to analyze the structural stability of the molecules within the active site of the Furin enzyme. The MD simulations were carried out using the Amber20 package for 200 ns, with the ff19SB force field (Tian et al. 2019; Case et al. 2020). The solvent box setup was prepared with a TIP3P water model with a 10 Å distance on each side with an NPT ensemble (Mark and Nilsson 2001). Temperature and pressure were maintained at 310 K and 1 atm; further, the system was neutralized by adding Na + /Cl- ions. The RMSD and RMSF plots are generated from the results obtained from the MD simulation. These findings are used to understand the conformational stability of both inhibitors in the active site of Furin; and also, the fluctuation of the amino acids of Furin enzyme during the MD simulation. From the trajectories of the MD simulation, the binding-free energies of both complexes were calculated using MM/GBSA/PBSA methods. The binding-free energy (ΔG) reveals the binding stability of ligands within the active site of Furin during the MD simulation.

Results and discussion

Induced fit-docking analysis

The inhibitors CMK and Naphthofluorescein with Furin enzymes produced distinct conformers for the IFD simulation, and the docking findings were examined (Table 1). The best conformer was selected for additional examination based on the IFD scores and the intermolecular interactions between the inhibitor and the Furin enzyme’s active site residues. Decanoyl-RVKR-chloromethylketone (CMK) and Naphthofluorescein molecules had respective IFD score values of − 9.18 and − 5.39 kcal/mol. The glide energies of CMK and Naphthofluorescein, − 85.93 and − 52 kcal/mol are respectively sums of various energy components such as van der Waals, electrostatic, and other intermolecular interactions indicate the stability of both docked complexes. The prime energies of these complexes − 21,344.3 (CMK) and − 19,878.9 (Naphthofluorescein) kcal/mol represent the protein, ligand, and solvation effects of the complex also signify the stability of the system. IFD scores which consider both docking scores and energy required for the Furin enzyme to adjust to both CMK and Naphthofluorescein also resulting stability of the complexes with scores -− 1076.94 and − 999.98 kcal/mol, respectively.

Table 1.

The docking scores (kcal/mol) of the different conformers of decanoyl-RVKR-chloromethylketone (CMK) and Naphthofluorescein with Furin complexes were obtained from the IFD simulation

| Conformer | decanoyl-RVKR-chloromethylketone (CMK) | Naphthofluorescein | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Docking score | Glide energy | Prime energy | IFD score | Docking score | Glide energy | Prime energy | IFD score | |

| 1 | − 9.18 | − 85.39 | − 21,344.3 | − 1076.94 | − 5.39 | − 52 | − 19,878.9 | − 999.98 |

| 2 | − 9.06 | − 88.74 | − 21,362.9 | − 1075.83 | − 5.05 | − 50.05 | − 19,883.1 | − 999.61 |

| 3 | − 9.05 | − 90.9 | − 21,347 | − 1075.4 | − 4.76 | − 46.62 | − 19,886.5 | − 998.82 |

| 4 | − 8.78 | − 92.29 | − 21,350.9 | − 1074.95 | − 4.39 | − 48.27 | − 19,879.3 | − 997.97 |

| 5 | − 8.67 | − 82.12 | − 21,351.2 | − 1074.89 | − 4.36 | − 47.1 | − 19,858.8 | − 997.95 |

| 6 | − 8.28 | − 68.87 | − 21,350.3 | − 1074.42 | − 4.26 | − 46.05 | − 19,870.3 | − 997.75 |

| 7 | − 8.10 | − 75.56 | − 21,335.8 | − 1074.26 | − 4.25 | − 45.8 | − 19,874.2 | − 997.64 |

| 8 | − 7.58 | − 77.81 | − 21,339.8 | − 1073.96 | − 4.04 | − 46.42 | − 19,873.3 | − 997.43 |

| 9 | − 7.47 | − 74.2 | − 21,340 | − 1073.64 | − 4.04 | − 46.57 | − 19,874.9 | − 997.29 |

| 10 | − 7.38 | − 74.27 | − 21,333.9 | − 1073.57 | − 4.00 | − 43.82 | − 19,867.9 | − 997.12 |

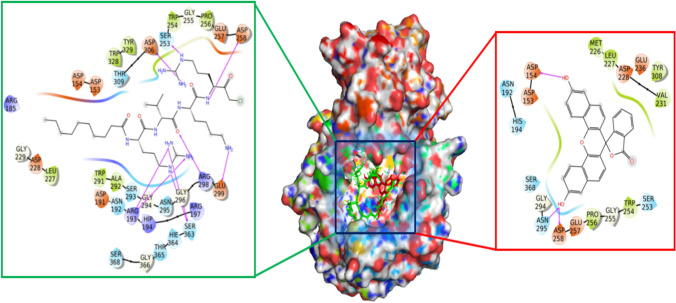

Both docked complexes were analyzed to understand the intermolecular interactions of the binding of the inhibitors with the active-site residues of the Furin enzyme using Discovery Studio and PyMol software (DeLano 2002; BIOVIA 2016) (Fig. 1). For the factual understanding, the top conformers were chosen and analyzed their intermolecular interactions (Table 2). To predict the best complex, the docking scores and the inhibitors that form interactions with the key residues of Furin were compared with the reported structures (Dahms et al. 2016; Vankadari 2020).

Fig. 1.

Intermolecular interactions of decanoyl-RVKR-chloromethylketone (CMK) (right) and Naphthofluorescein (left) within the active site of the Furin enzyme, as obtained from Induced Fit Docking studies. The figure illustrates how each inhibitor binds to the Furin-active site, highlighting the key residues involved in the binding interactions

Table 2.

Intermolecular interactions and the contact distance (Å) between the decanoyl-RVKR-chloromethylketone (CMK) and Naphthofluorescein with the active site residues of Furin obtained from IFD docking and MD simulations

| Interacting residues of Furin enzyme···Ligand atoms | Type of interactions | Distance (Å) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Docking | MD | |||

| 100 ns | 200 ns | |||

| Decanoyl-RVKR-chloromethylketone (CMK) | ||||

| ASN133/HD22⋅⋅⋅O2 | Hydrogen bond | – | 2.52 | – |

| ALA139/O⋅⋅⋅H(41) | Hydrogen bond | – | 2.58 | – |

| ASP154/OD2⋅⋅⋅H(39) | Hydrogen bond | 2.95 | – | – |

| ASP191/O⋅⋅⋅H(39) | Hydrogen bond | 2.57 | – | – |

| ARG193/HE⋅⋅⋅O(5) | Hydrogen bond | 2.25 | – | – |

| LEU227/O⋅⋅⋅H(6) | Hydrogen bond | 1.93 | – | – |

| ASP228/OD1⋅⋅⋅H(50) | Hydrogen bond | 2.58 | – | – |

| SER253/O⋅⋅⋅H(56) | Hydrogen bond | 2.43 | – | - |

| TRP254⋅⋅⋅C(4) | Pi-Alkyl | 5.41 | – | – |

| PRO256/O⋅⋅⋅H(2) | Hydrogen bond | 1.97 | – | – |

| GLU257/OE1⋅⋅⋅H(38) | Hydrogen bond | 2.19 | – | – |

| GLY294/HA3⋅⋅⋅N(4) | Hydrogen bond | 3.03 | – | – |

| ASN295/HD21⋅⋅⋅O(3) | Hydrogen bond | 2.64 | – | – |

| ARG298/HH22⋅⋅⋅O(3) | Hydrogen bond | 2.25 | – | – |

| ASP306/OD2⋅⋅⋅H(7) | Hydrogen bond | 1.98 | – | – |

| TRP328⋅⋅⋅C(6) | Pi-Alkyl | 4.40 | – | – |

| TYR329⋅⋅⋅C(6) | Pi-Alkyl | 4.08 | – | – |

| HIS364/ND1⋅⋅⋅H(15) | Hydrogen bond | 2.14 | – | – |

| THR365/OG1⋅⋅⋅H(13) | Hydrogen bond | 1.88 | – | – |

| GLN399/OE1⋅⋅⋅H(7) | Hydrogen bond | – | – | 2.04 |

| GLY432/HA2⋅⋅⋅O(2) | Hydrogen bond | – | 2.51 | – |

| ALA436⋅⋅⋅C(15) | Alkyl | – | 3.73 | – |

| ASN440/O⋅⋅⋅H(59) | Hydrogen bond | – | – | 1.96 |

| THR442/HN⋅⋅⋅N9 | Hydrogen bond | – | – | 2.60 |

| LEU578⋅⋅⋅C(15) | Alkyl | – | – | 4.78 |

| Naphthofluorescein | ||||

| ASP153/OD2⋅⋅⋅H(4) | Hydrogen bond | 3.70 | 7.50 | 6.90 |

| ASP154/OD2⋅⋅⋅H(16) | Hydrogen bond | 1.97 | – | 1.78 |

| ARG193/NH2⋅⋅⋅Benzene | Pi-Cation | 5.30 | – | – |

| HIS194/ND1⋅⋅⋅Benzene | Pi-Cation | 3.30 | 5.70 | 6.00 |

| LEU227⋅⋅⋅Benzene | Pi-Alkyl | 4.22 | 4.18 | 4.06 |

| GLU230/OE2⋅⋅⋅H(16) | Hydrogen bond | – | 1.70 | 5.70 |

| VAL231⋅⋅⋅Benzene | Pi-Alkyl | 3.93 | 2.37 | 3.01 |

| GLU236/OE1⋅⋅⋅Benzene | Pi-Anion | 4.30 | 4.32 | 4.25 |

| SER253/HG⋅⋅⋅O(4) | Hydrogen bond | 3.40 | 7.60 | - |

| TRP254⋅⋅⋅Benzene | Pi-Pi Stacked | 5.41 | 4.70 | 4.57 |

| PRO256/HA⋅⋅⋅O(3) | Hydrogen bond | 3.70 | 2.47 | 2.29 |

| PRO256⋅⋅⋅Benzene | Pi-Alkyl | 2.20 | 3.40 | 3.10 |

| GLU257/H⋅⋅⋅O(3) | Hydrogen bond | 5.10 | 2.41 | 3.60 |

| ASP258/OD2Z⋅⋅⋅H(15) | Hydrogen bond | 1.86 | – | – |

| ASN295/HD21⋅⋅⋅O(4) | Hydrogen bond | 2.09 | – | – |

CMK forms the hydrogen bonding interactions with the Furin residues Asp154, Asp191, Arg193, Leu227, Asp228, Ser253, Pro256, Glu257, Gly294, Asn295, Arg298, Asp306, His364, and Thr365 with the distance 2.95, 2.57, 2.25, 1.93, 2.58, 2.43, 1.97, 2.19, 3.03, 2.64, 2.25, 1.98, 2.14 and 1.88 Å, respectively. Whereas, the Naphthofluorescein forms the hydrogen bonding interactions with Furin residues Asp153, Asp154, Ser253, Asp258, and Asn295 with the distances 3.70, 1.97, 3.40, 1.86, and 2.09 Å, respectively. Furthermore, both inhibitors form interactions with the catalytic site residues of Furin. From these analyses, it is found that both molecules exhibit interactions with the Furin-active-site residues and are highly stable in the active site.

MD simulations

The best conformer of CMK and Naphthofluorescein in the active site of Furin obtained from the IFD simulation was chosen for the MD simulation study of the CMK-Furin and Naphthofluorescein-Furin complexes. Thus, the selected best conformer exhibits lowest energy and form interactions with the key amino acids of active site of the Furin enzyme and their binding affinity. The MD simulations for both complexes were performed up to 200 ns to understand their dynamic binding nature and the stability of the molecules in the Furin binding-site residues.

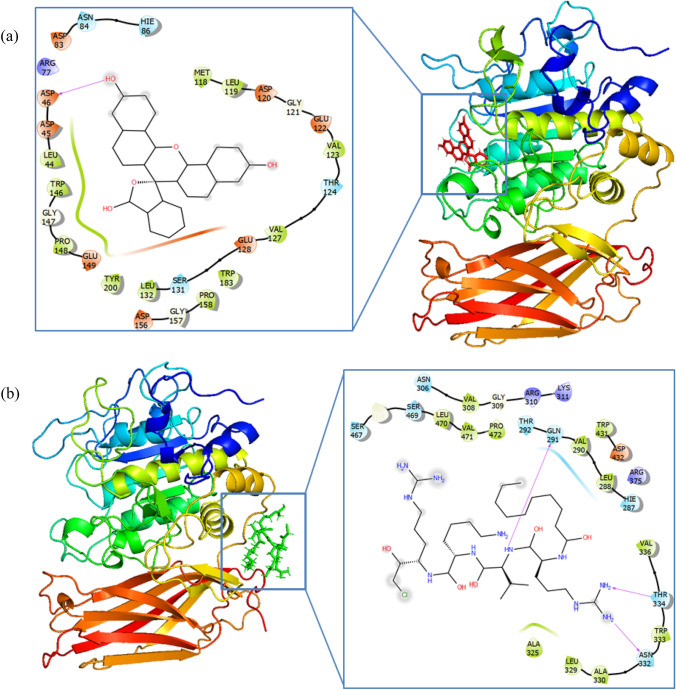

Intermolecular interactions between decanoyl-RVKR-chloromethylketone (CMK) and Naphthofluorescein and Furin-active-site residues

The intermolecular interactions of both molecules were analyzed from the final frame of the MD trajectories which are converted as the PDB format. This final frame file represents the MD simulation form of the complex, this allows to compare and analyze the intermolecular interactions with the docked complex; this facilitates understanding the conformational modifications and binding nature of the inhibitors (Fig. 2) during the MD simulations. Unlike as found in the docked complex, the MD simulation predicts the stability of intermolecular interactions of CMK inhibitor; notably, it forms new interactions with the binding site amino-acid residues Gln399, Asn440, Thr442, and Leu578 at the distance of 2.04, 1.96, 2.60, and 4.78 Å, respectively. These interactions confirm that the binding site of Furin for CMK was totally changing during the MD simulation (Fig. 3). Hence, the intermolecular interactions of the CMK with Furin-active-site residues are missed and so far there is no experimental studies have been reported to understand the enzymatic activities of this new binding site.

Fig. 2.

Intermolecular interactions between Furin and a Decanoyl-RVKR-chloromethylketone (CMK) or b Naphthofluorescein during the MD simulation, highlighting the key interactions between the inhibitors and Furin residues

Fig. 3.

Superimposed structures of a CMK-Furin and b Naphthofluorescein-Furin complexes, obtained from molecular docking and MD simulations, illustrating the conformational differences between the two complexes

Whereas, in the MD simulation of the Naphthofluorescein-Furin complex, the Naphthofluorescein molecule also forms a similar type of intermolecular interactions with the Furin as found in the docked complex. It forms hydrogen bonding interactions with the amino-acid residues Asp153, Asp154, Pro256, and Glu257 at the distance of 6.90, 1.78, 2.29, and 3.60 Å, respectively. This molecule also forms pi-type interactions with the residues His194, Trp254, and Pro256 at distances of 7.00, 4.57, and 3.10 Å, respectively. From this, it is confirmed that the intermolecular interactions found in the molecular docking are well maintained during the MD simulations and are not altered, indicating the Naphthofluorescein is well stable. Notably, during the MD simulation, the CMK molecule completely moved away from the Furin binding site as predicted by the molecular docking. Among these findings, unequivocally it is confirmed that the Naphthofluorescein exhibits high stability in the active site of Furin.

RMSD analysis

The RMSD variation of both complexes are plotted (Fig. 4) with the reference frame (docked complex) and calculated based on the atomic selection of MD simulation trajectories. For the CMK-Furin complex up to 100 ns simulation, the deviations are slightly uneven with the range of 1 to 2.3 Å. Further, from 100 to 200 ns simulation, the RMSD variation is found as evenly deviated with the range of 1.7 to 2.2 Å. Whereas in the Naphthofluorescein-Furin complex, the RMSD is slightly raised (1.6 to 2.7 Å) in between 60–80 ns and 175–185 ns MD simulation. And remaining trajectories show even deviation with the range of 1.5 to 1.9 Å. However, the variation of RMSD for both complexes is relatively small, this confirms that the conformational modifications of protein are not abnormal and are at an acceptable level.

Fig. 4.

RMSD variation for CMK-Furin and Naphthofluorescein-Furin complexes during the MD simulations, depicting the stability and structural deviations of the complexes over time

The RMSD of CMK shows high deviations during the MD simulation, this confirms that the CMK molecule is unstable in the active site of Furin. Whereas in the Naphthofluorescein-Furin complex, the values of RMSD of the Naphthofluorescein molecule shows that the deviation is not significant during the MD simulation; it confirms that the molecule is stable in the active site and the intermolecular interactions also not much varied during the simulation.

RMSF analysis

To understand the fluctuations of the amino-acid residues of Furin in the ligand-Furin complex, the root means square fluctuation (RMSF) values are plotted (Fig. 5). For both CMK-Furin and Naphthofluorescein-Furin complexes, the fluctuations are found in the range of 0.5 to 2.0 Å. In both complexes, the loop-region residues show high fluctuation during the simulation, in which notably, the alpha helices and beta strands are rigid than the loops. During the simulation, the N and C terminals also display high fluctuation, which is found to be higher than the other amino-acid residues of the Furin. However overall, the amino acids of both complexes do not show any significant fluctuations and are normal during the simulation; this indicates that the Furin in both complexes are found stable.

Fig. 5.

RMSF plots of the amino-acid residues of Furin in the CMK-Furin (blue) and Naphthofluorescein-Furin (red) complexes during the MD simulation, highlighting the fluctuations in residue mobility over the simulation period

Radius of gyration

The radius of gyration (Rg) is one of the most significant calculations, widely used to predict the structural activity of macromolecules (Falsafi-Zadeh et al. 2012). To understand the compactness of the ligand–protein, the Radius of gyration (Rg) was analyzed for both CMK and Naphthofluorescein with Furin complexes during the MD simulation (Fig. 6). For the CMK-Furin complex, the Rg values under the range from 22 to 22.4 Å up to 100 ns; further Rg values slightly increased by 0.1 Å up to 200 ns. In the Naphthofluorescein-Furin complex, the Rg values have been observed in the average range of 22.1 to 22.5 Å. However, the observed values show that both complexes are not much altered and the high folded nature is also indicated over the entire MD simulation.

Fig. 6.

Radius of gyration (Rg) plots for CMK-Furin (violet) and Naphthofluorescein-Furin (green) complexes during the MD simulation, illustrating the changes in the compactness and stability of each complex over time

Hydrogen bonding

The number of hydrogen bonding formations has been plotted for both complexes throughout the MD simulation (Fig. 7). Hydrogen bonds significantly contribute to the strong complex formation during the MD simulation. For the CMK-Furin complex, during the MD simulation, there is a slight decrease in the number of hydrogen bonding interactions noticed during the 100–150 ns time scale; a remaining number of hydrogen bonds are found in the range of 235–275. In the Naphthofluorescein-Furin complex, the number of hydrogen bonds formed in the range of 230–280, this exists throughout the MD simulation. Among these results, the Naphthofluorescein-Furin complex maintains more number of hydrogen bonds throughout the MD simulation.

Fig. 7.

Plots showing the number of hydrogen bonds formed in a CMK-Furin complex and b Naphthofluorescein-Furin complex during the MD simulation, depicting fluctuations in hydrogen-bond counts over time and illustrating interaction stability between each inhibitor and the Furin enzyme

DSSP (secondary structure analysis)

DSSP (Define Secondary Structure of Proteins) is the standard hydrogen-bond estimation algorithm for validating the secondary structures of the protein amino acids (Kabsch and Sander 1983). In this work, DSSP was analyzed for both complexes (Fig. 8) during the MD simulation using the CPPTRAJ program which availed with AmberTools20 (Roe and Cheatham 2013). Secondary structural modifications have been analyzed by comparing the protein structures of docking, 100 ns, and 200 ns (Table 3). In the CMK-Furin complex, HIS160-GLY165, ASP168-SER172, and GLY296-HIS300 have loop-helices modifications; and ILE351-GLU362 has some large sheet-loop modifications. In the Naphthofluorescein-Furin complex, LYS117-GLY126, LEU163-TYR167, and SER302-ASP306 have loop-helices modifications; and LEU337-SER342 has some large sheet-loop modifications.

Fig. 8.

DSSP plots showing the secondary structure changes of Furin complexes during the MD simulation. a CMK-Furin complex, and b Naphthofluorescein-Furin complex. The plots illustrate the evolution of secondary structural elements over time, highlighting variations in secondary structure content for each complex

Table 3.

Residue level secondary structural modifications of Furin enzyme while the inhibitors (a) CMK and (b) Naphthofluorescein bound with the binding site of Furin found in docking and MD simulations

| Residues | Docking | MD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 ns | 200 ns | ||

| CMK-Furin | |||

| HIS160-GLY165 |  |

|

|

| ASP168-SER172 |  |

|

|

| GLY296-HIS300 |  |

|

|

| ILE351-GLU362 |  |

|

|

| Naphthofluorescein-Furin | |||

| LYS117-GLY126 |  |

|

|

| LEU163-TYR167 |  |

|

|

| SER302-ASP306 |  |

|

|

| LEU337-SER342 | |||

Notably, there is no modifications are observed with the residues which form the intermolecular interactions with both molecules during the MD simulation. The above-mentioned structural modifications may happen in the protein structures due to their dynamic nature with a set of ensembles with bounded inhibitors.

Binding-free energy

To understand the binding-free energy of two inhibitors with Furin enzyme, the binding-free energy has been calculated using the MM/GBSA method from the MD simulation (Table 3). The binding-free energy of the CMK and Naphthofluorescein with Furin enzyme complexes are calculated from the MD trajectories using the MM/GBSA/PBSA method. However the MM/GBSA is a popular method, this is due to its commendatory computational speed and accuracy on compare with the MM/PBSA method (Hou et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2019). The MM/GBSA results show the different components and major energy contribution of binding-free energy of inhibitors, proteins, and complexes (Table 3). The MM/GBSA binding-free energy value (ΔG) of the CMK-Furin complex is − 20.06 ± 3.46 kcal/mol, whereas for Naphthofluorescein-Furin this value is − 20.67 ± 3.14 kcal/mol. The ΔG of both inhibitors indicates that they exhibit high binding affinity toward Furin, in which the Naphthofluorescein shows a slight difference compared with CMK. The MM/PBSA energy values show the high binding-free-energy value for the CMK-Furin complex (− 21.61 ± 4.19 kcal/mol) while compared with the Naphthofluorescein-Furin complex (− 18.03 ± 4.76 kcal/mol) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Binding-free energies (kcal/mol) of decanoyl-RVKR-chloromethylketone (CMK) and Naphthofluorescein with Furin complexes calculated using prime MM/GBSA

| Binding-free-energy components | CMK-Furin | Naphthofluorescein-Furin | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 ns | 200 ns | 100 ns | 200 ns | |

| MM | ||||

| ∆Evdw | − 36.95 ± 3.87 | − 32.38 ± 3.34 | − 29.64 ± 2.85 | − 31.92 ± 2.89 |

| ∆Eele | − 32.08 ± 8.06 | − 12.84 ± 8.08 | − 17.55 ± 12.34 | − 7.96 ± 9.11 |

| GBSA | ||||

| ∆GGB | 43.89 ± 6.28 | 29.69 ± 7.44 | 29.71 ± 9.06 | 23.29 ± 7.76 |

| ∆Gsurf | − 5.54 ± 0.60 | − 4.53 ± 0.49 | − 3.95 ± 0.29 | − 4.01 ± 0.28 |

| ∆Ggas | − 69.04 ± 9.52 | − 45.22 ± 9.23 | − 47.17 ± 11.53 | − 39.86 ± 9.69 |

| ∆Gsolv | 38.68 ± 5.85 | 25.16 ± 7.12 | 25.76 ± 8.94 | 19.20 ± 7.65 |

| ∆Gtotal | − 30.68 ± 4.51 | − 20.06 ± 3.46 | − 21.41 ± 3.36 | − 20.67 ± 3.14 |

| PBSA | ||||

| ∆GPB | 43.31 ± 6.62 | 27.32 ± 8.08 | 32.46 ± 8.91 | 25.39 ± 8.38 |

| ∆Gnpolar | − 4.43 ± 0.27 | − 3.71 ± 0.33 | − 3.41 ± 0.18 | − 3.56 ± 0.18 |

| ∆Ggas | − 69.03 ± 9.52 | − 45.22 ± 9.23 | − 47.17 ± 11.52 | − 39.86 ± 9.69 |

| ∆Gsolv | 38.88 ± 6.45 | 23.61 ± 7.86 | 29.05 ± 8.85 | 21.83 ± 8.31 |

| ∆Gtotal | − 30.16 ± 4.66 | − 21.61 ± 4.19 | − 18.12 ± 5.11 | − 18.03 ± 4.76 |

The energy contributions given in the table,

∆Evdw- Van der Waals contribution from MM

∆Eele- Electrostatic energy calculated by MM force field

∆GGB- Solvation-free energy calculated by Generalized Born

∆GPB- Solvation-free energy calculated by Poisson Boltzmann

∆Gsurf- Surface area energy

∆Ggas- Gas-phase energy

∆Gsolv- Total solvation-free energy

∆Gnpolar- Non-polar contribution to solvation-free energy

∆Gtotal- Total binding-free energy (kcal/mol)

From the results of MM/GBSA, it can be concluded that the Naphthofluorescein-Furin complex has high stability than the CMK-Furin during the MD simulation. This may be due to the greater number of interactions in the Naphthofluorescein-Furin complex sustained as found in docking simulation. On the other hand, in CMK-Furin complex found low energy values after the MD simulation, this is unlike the molecular docking results; this may be due to the change of interactions in the Furin-binding site (Table 2). Among these results with the reports from the previous articles, MM/GBSA calculation has been considered as further confirmation. Based on the above results, the Naphthofluorescein molecule exhibits a high binding affinity toward Furin when compared with the CMK-Furin complex.

Summary and conclusion

One key strategy for reducing the severe impacts of cancer phenotypes and inhibiting the entry and replication of the SARS-CoV-2 viral protein is to inhibit Furin. Beta-coronaviruses and the other generation of coronaviruses both consist of Furin-cleavage sites. In addition, the highly transmissible and ineffective functionalities of SARS-CoV-2 are largely due to the Furin-like cleavage site. Using molecular docking and MD simulations, the current study aims to comprehend the binding mechanism of the experimentally reported Furin inhibitors CMK and Naphthofluorescein. According to the molecular docking simulation, both inhibitors have binding affinities of − 5.39 kcal/mol and − 9.18 kcal/mol, respectively, and they generate important interactions with Furin. In addition, the MD simulation demonstrates the high stability of the Naphthofluorescein-Furin complex and its ability to form intermolecular interactions with Furin; however, during the simulation, the CMK molecule was moved away from Furin-s active site and bound to another binding site, which has not been reported in any experimental studies. Both compounds exhibit strong binding affinities (20.06 ± 3.46 and − 20.67 ± 3.14 kcal/mol) for CMK and Naphthofluorescein with furin, according to the MM/GBSA. Despite having good binding-energy values during the MD simulation, CMK's intermolecular interactions have changed at the binding site. However, the MD simulation demonstrates that the Naphthofluorescein molecule has a strong binding affinity, which is supported by the findings of the binding-free energy analysis. Throughout the MD simulation, the Naphthofluorescein molecule preserved the intermolecular connections within the Furin-active site. Overall, after clinical testing, the Naphthofluorescein molecule may be regarded as a repurposed medicine for COVID-19 since it may be a lead molecule to inhibit the Furin enzyme.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Computer Centre, Periyar University, Salem for performing the computational work in the High-Performance Cluster (HPC) Computer funded by RUSA.

Author’s contributions

All authors have contributed equally.

Data availability

The data supporting this study's findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and animal rights and informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

- Berman HM, Battistuz T, Bhat TN et al (2002) The protein data bank. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr 58:899–907. 10.1107/S0907444902003451 10.1107/S0907444902003451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BIOVIA (2016) Discovery studio modeling environment, release (2017). San Diego Dassault Syst

- Case DA, Belfon K, Ben-Shalom IY, et al (2020) AMBER 2020

- Cheng YW, Chao TL, Li CL et al (2020) Furin inhibitors block SARS-CoV-2 spike protein cleavage to suppress virus production and cytopathic effects. Cell Rep. 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108254 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppola JM, Bhojani MS, Ross BD, Rehemtulla A (2008) A small molecule furin inhibitor inhibits cancer cell motility and invasiveness. Neoplasia 10:363–370. 10.1593/neo.08166 10.1593/neo.08166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahms SO, Arciniega M, Steinmetzer T et al (2016) Structure of the unliganded form of the proprotein convertase furin suggests activation by a substrate-induced mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:11196–11201. 10.1073/pnas.1613630113 10.1073/pnas.1613630113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLano WL (2002) Pymol: an open-source molecular graphics tool. CCp4 Newsl Protein Crystallogr 40:82–92 [Google Scholar]

- Duan L, Zheng Q, Zhang H et al (2020) The SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein biosynthesis, structure, function, and antigenicity: implications for the design of spike-based vaccine immunogens. Front Immunol 11:1–12. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.576622 10.3389/fimmu.2020.576622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falsafi-Zadeh S, Karimi Z, Galehdari H (2012) VMD DisRg: New User-Friendly Implement for calculation distance and radius of gyration in VMD program. Bioinformation 8:341–343. 10.6026/97320630008341 10.6026/97320630008341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follis KE, York J, Nunberg JH (2006) Furin cleavage of the SARS coronavirus spike glycoprotein enhances cell-cell fusion but does not affect virion entry. Virology 350:358–369. 10.1016/j.virol.2006.02.003 10.1016/j.virol.2006.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halgren T (2007) New method for fast and accurate binding-site identification and analysis. Chem Biol Drug Des 69:146–148. 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2007.00483.x 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2007.00483.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallenberger S, Bosch V, Angliker H et al (1992) Inhibition of furin-mediated cleavage activation of HIV-1 glycoprotein gpl60. Nature 360:358–361. 10.1038/360358a0 10.1038/360358a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich S, Cameron A, Bourenkov GP et al (2003) The crystal structure of the proprotein processing proteinase furin explains its stringent specificity. Nat Struct Mol Biol 10:520–526. 10.1038/nsb941 10.1038/nsb941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Pöhlmann S (2020) A multibasic cleavage site in the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 is essential for infection of human lung cells. Mol Cell 78:779-784.e5. 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.04.022 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.04.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou T, Wang J, Li Y, Wang W (2011) Assessing the performance of the MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods. 1. The accuracy of binding free energy calculations based on molecular dynamics simulations. J Chem Inf Model 51:69–82. 10.1021/ci100275a 10.1021/ci100275a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imran M, Saleemi MK, Chen Z et al (2019) Decanoyl-Arg-Val-Lys-Arg-chloromethylketone: an antiviral compound that acts against flaviviruses through the inhibition of furin-mediated prM cleavage. Viruses 11:999. 10.3390/v11110999 10.3390/v11110999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Li D, Maghsoudloo M et al (2024) Targeting furin, a cellular proprotein convertase, for COVID-19 prevention and therapeutics. Drug Discov Today. 10.1016/j.drudis.2024.104026 10.1016/j.drudis.2024.104026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BA, Xie X, Bailey AL et al (2021) Loss of furin cleavage site attenuates SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis. Nature 591:293–299. 10.1038/s41586-021-03237-4 10.1038/s41586-021-03237-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W, Sander C (1983) Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers 22:2577–2637. 10.1002/bip.360221211 10.1002/bip.360221211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Chen J, Cheng T et al (2021) PubChem in 2021: New data content and improved web interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res 49:D1388–D1395. 10.1093/nar/gkaa971 10.1093/nar/gkaa971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Wu C, Ghoreishi D et al (2021) OPLS4: improving force field accuracy on challenging regimes of chemical space. J Chem Theory Comput 17:4291–4300. 10.1021/acs.jctc.1c00302 10.1021/acs.jctc.1c00302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark P, Nilsson L (2001) Structure and dynamics of the TIP3P, SPC, and SPC/E water models at 298 K. J Phys Chem A 105:9954–9960. 10.1021/jp003020w 10.1021/jp003020w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ornatowski W, Poschet JF, Perkett E et al (2007) Elevated furin levels in human cystic fibrosis cells result in hypersusceptibility to exotoxin A-induced cytotoxicity. J Clin Invest 117:3489–3497. 10.1172/JCI31499 10.1172/JCI31499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock TP, Goldhill DH, Zhou J et al (2021) The furin cleavage site in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein is required for transmission in ferrets. Nat Microbiol 6:899–909. 10.1038/s41564-021-00908-w 10.1038/s41564-021-00908-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remacle AG, Gawlik K, Golubkov VS et al (2010) Selective and potent furin inhibitors protect cells from anthrax without significant toxicity. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 42:987–995. 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.02.013 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.02.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter N, Chen X, Kropff B et al (2023) SARS-CoV-2 spike protein is capable of inducing cell-cell fusions independent from its receptor ACE2 and this activity can be impaired by furin inhibitors or a subset of monoclonal antibodies. Viruse-**/s 15:1500. 10.3390/v15071500 10.3390/v15071500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe DR, Cheatham TE (2013) PTRAJ and CPPTRAJ: Software for processing and analysis of molecular dynamics trajectory data. J Chem Theory Comput 9:3084–3095. 10.1021/ct400341p 10.1021/ct400341p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastry GM, Adzhigirey M, Sherman W (2013) Protein and ligand preparation: parameters, protocols, and influence on virtual screening enrichments. J Comput Mol Desig 27:221–234. 10.1007/s10822-013-9644-8 10.1007/s10822-013-9644-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneck NA, Ivleva VB, Cai CX et al (2020) Characterization of the furin cleavage motif for HIV-1 trimeric envelope glycoprotein by intact LC-MS analysis. Analyst 145:1636–1640. 10.1039/C9AN02098E 10.1039/C9AN02098E [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrödinger (2020) LigPrep

- Shelley JC, Cholleti A, Frye LL et al (2007) Epik: a software program for pK a prediction and protonation state generation for drug-like molecules. J Comput Aided Mol Des 21:681–691. 10.1007/s10822-007-9133-z 10.1007/s10822-007-9133-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman W, Day T, Jacobson MP et al (2006) Novel procedure for modeling ligand/receptor induced fit effects. J Med Chem 49:534–553. 10.1021/jm050540c 10.1021/jm050540c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian C, Kasavajhala K, Belfon AAK et al (2019) ff19SB: Amino-acid-specific protein backbone parameters trained against quantum mechanics energy surfaces in solution. J Chem Theory Comput 16:528–552. 10.1021/acs.jctc.9b00591 10.1021/acs.jctc.9b00591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vankadari N (2020) Structure of furin protease binding to SARS-CoV - 2 spike glycoprotein and implications for potential targets and virulence. J Phys Chem Lett 11:6655–6663. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.0c01698 10.1021/acs.jpclett.0c01698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang E, Sun H, Wang J et al (2019) End-point binding free energy calculation with MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA: strategies and applications in drug design. Chem Rev 119:9478–9508. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00055 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Zhong K, Wang G et al (2023) Loss of furin site enhances SARS-CoV-2 spike protein pseudovirus infection. Gene 856:147144. 10.1016/j.gene.2022.147144 10.1016/j.gene.2022.147144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Zhao S (2021) Furin cleavage sites naturally occur in coronaviruses. Stem Cell Res. 10.1016/j.scr.2020.102115 10.1016/j.scr.2020.102115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu F, Xu J, Chen H et al (2024) Proprotein convertase cleavage of Ictalurid herpesvirus 1 spike-like protein ORF46 is modulated by N-glycosylation. Virology. 10.1016/j.virol.2024.110008 10.1016/j.virol.2024.110008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou F, Liu Q, Zhang L et al (2020) Selective inhibition of CBP / p300 HAT by A-485 results in suppression of lipogenesis and hepatic gluconeogenesis. Cell Death Dis 11:745. 10.1038/s41419-020-02960-6 10.1038/s41419-020-02960-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study's findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.