Abstract

Background

Early screening using low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) can reduce mortality caused by non-small-cell lung cancer. However, ∼25% of the ‘suspicious’ pulmonary nodules identified by LDCT are later confirmed benign through resection surgery, adding to patients’ discomfort and the burden on the healthcare system. In this study, we aim to develop a noninvasive liquid biopsy assay for distinguishing pulmonary malignancy from benign yet ‘suspicious’ lung nodules using cell-free DNA (cfDNA) fragmentomics profiling.

Methods

An independent training cohort consisting of 193 patients with malignant nodules and 44 patients with benign nodules was used to construct a machine learning model. Base models using four different fragmentomics profiles were optimized using an automated machine learning approach before being stacked into the final predictive model. An independent validation cohort, including 96 malignant nodules and 22 benign nodules, and an external test cohort, including 58 malignant nodules and 41 benign nodules, were used to assess the performance of the stacked ensemble model.

Results

Our machine learning models demonstrated excellent performance in detecting patients with malignant nodules. The area under the curves reached 0.857 and 0.860 in the independent validation cohort and the external test cohort, respectively. The validation cohort achieved an excellent specificity (68.2%) at the targeted 90% sensitivity (89.6%). An equivalently good performance was observed while applying the cut-off to the external cohort, which reached a specificity of 63.4% at 89.7% sensitivity. A subgroup analysis for the independent validation cohort showed that the sensitivities for detecting various subgroups of nodule size (<1 cm: 91.7%; 1-3 cm: 88.1%; >3 cm: 100%; unknown: 100%) and smoking history (yes: 88.2%; no: 89.9%) all remained high among the lung cancer group.

Conclusions

Our cfDNA fragmentomics assay can provide a noninvasive approach to distinguishing malignant nodules from radiographically suspicious but pathologically benign ones, amending LDCT false positives.

Key words: noninvasive, low-pass WGS, cancer detection, NSCLC, automated machine learning

Highlights

-

•

We developed a noninvasive liquid biopsy assay for distinguishing malignant and benign lung nodules.

-

•

Our model showed high area under the curves of 0.857 and 0.860 in independent validation and external test cohorts.

-

•

Our model can help minimize unnecessary intrusive interventions by reducing false-positive test results from LDCT screening.

Introduction

Lung cancer is one of the most common cancer types, with ∼2.2 million cases globally in 2020, second only to breast cancer.1, 2, 3 Despite advancements in new treatments in recent decades, non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) remains the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide, with ∼1.8 million deaths globally in 2020.1, 2, 3 Although the 5-year survival rate for localized NSCLC is relatively optimistic at 64%, it drops significantly to only 8% for patients with distant metastasis, according to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program.4 However, early-stage NSCLC is often asymptomatic, and many patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage, resulting in poor prognoses.4 Therefore the development of an effective early detection assay is crucial for treating patients with NSCLC.

Low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) is currently the most effective way to detect small pulmonary nodules in patients who are at risk of NSCLC, which outperforms the X-ray examination by having a higher detection rate.5,6 However, LDCT relies heavily on the expertise of clinicians to interpret the results, as it is a qualitative diagnosis. This means that nodules identified as ‘suspicious’ based on factors such as size, shape, and location can be misdiagnosed. In fact, up to 25% of these nodules are later found to be benign after undergoing resection surgery and pathological confirmation based on results from the National Lung Screening Trial.5,6 These invasive examinations not only cause discomfort for patients, but also add to the burden on the healthcare system. Therefore there is a crucial need for non-invasive methods that can accurately distinguish malignant from benign lung nodules with false-positive (FP) LDCT results.

The utilization of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) fragmentomics has shown great potential in early cancer detection, as tumor DNAs being shed into circulation are known to have distinguishable characteristics such as size, distribution, and other patterns.7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Using various cfDNA fragmentomics profiling, researchers developed novel noninvasive liquid biopsy assays to detect patients with malignant pulmonary nodules among healthy individuals.12, 13, 14 Mathios et al.12 showed that their DELFI diagnostic assay could detect lung cancer with high accuracy, reaching an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.90. In another study, Guo et al.14 demonstrated that the cfDNA breakpoint motif (BPM) could detect stage I lung adenocarcinoma with AUCs of 0.985 and 0.954 in the internal and external validation cohorts, respectively. Furthermore, Bao et al.13 reported an ultra-sensitive multicancer early detection assay that could detect stage I lung adenocarcinoma with an AUC of 0.973; the assay also had 91.6% accuracy in determining the tissue of origin. Given the excellent distinguishing power of cfDNA fragmentomics profiling between pulmonary malignancy and healthy plasma, it is worth investigating whether it can be used to detect pulmonary malignancy from benign lung nodules.

In this study, we set to develop a noninvasive liquid biopsy assay that could distinguish between malignant and benign lung nodules using cfDNA fragmentomic profiling. Unlike the previous studies utilizing healthy controls, our noninvasive cfDNA fragmentomic assay focused on patients who had FP results by the traditional LDCT screening method. We recruited a training cohort of 193 patients with malignant and 44 patients with benign pulmonary nodules and a validation cohort of 96 patients with malignant and 22 patients with benign lung nodules. Fragmentomics feature profiling, including fragment size distribution (FSD), fragment size ratio (FSR), BPM, and neomer, was generated using low-pass whole genome sequencing (WGS) data from plasma samples. To create our predictive model, we used an ensemble stacked machine learning approach that optimized base models through an automated machine learning (autoML) process.

Methods

Cohort design and patient enrollment

The R package MKmisc (version 1.8; R Foundation, Vienna, Austria), developed to calculate sample size requirements in binary classification tests,15 was used to calculate the size required for the cohorts. According to the MKmisc test result, a cohort containing ∼94 malignant nodules and ∼24 benign nodules was required to validate a designed 90% sensitivity (margin of error = 10%, significance level = 0.05, power of test = 0.8, and prevalence = 0.8).

All patients enrolled were recruited from the Department of Thoracic Surgery at the First Hospital of China Medical University and presented with pulmonary symptoms including chronic cough, hemoptysis, shortness of breath, among others. The enrolled patients were suspected of pulmonary malignancy based on various characteristics of positive LDCT results as described in the Guidelines for Management of Incidental Pulmonary Nodules Detected on CT Images (2017),16 including but not limited to nodule location, nodule density, vessel convergence, and pleural depression. All patients received resection surgery based on a consensus ruling from two independent radiologists blinded to the clinical and pathological information. The malignant or benign status of the nodules was then pathologically confirmed.

The inclusion criteria for patients with malignant nodules were (i) patients must be at least 18 years of age and capable of giving written informed consent; (ii) no known cancer history within 5 years of study enrollment; (iii) no prior/current treatment for malignant tumors; and (iv) highly suspicious for malignancy by LDCT, with confirmed malignancy diagnosis through biopsy or surgical resection within 14 (±7) days of blood draw. The inclusion criteria for patients with benign nodules were (i) patients must be at least 18 years of age and capable of giving written informed consent; (ii) no known cancer history within 5 years of study enrollment; (iii) no prior/current treatment for malignant tumors; and (iv) highly suspicious for malignancy by LDCT, with confirmed benign nodule diagnosis through biopsy or surgical resection within 14 (±7) days of blood draw. The exclusion criteria for all patients were as follows: (i) unable to provide sufficient qualified blood sample; (ii) pregnancy or lactation; (iii) history of organ/bone marrow transplantation; (iv) received a blood transfusion within 14 days before the blood draw.

A total of 355 patients, who all had positive LDCT results suspecting pulmonary malignancy, were enrolled in this study between March 2021 and June 2022, including 289 patients with malignant nodules and 66 patients with benign nodules (Figure 1A). These patients were assigned to an independent training and an independent validation cohort at a 2 : 1 ratio based on the decision of physicians, who were not involved in the subsequent process of sample preparation, sequencing and feature extraction, machine learning model construction, and evaluation. The independent training cohort consisted of 193 patients with malignant nodules and 44 patients with benign nodules, while the independent validation cohort included 96 malignant nodules and 22 benign nodules. The training cohort was used to train and optimize the machine learning model, while the validation cohort was used to evaluate model performances.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of methodology and cohort design. (A) The training cohort (n = 237), which included 193 patients with lung cancer and 44 patients with benign lung nodules, was used to train the model. The validation cohort (n = 118), which included 96 patients with lung cancer and 22 patients with benign lung nodules, and an external test cohort (n = 99), which included patients with 58 lung cancer and 41 patients with benign nodules, were used to evaluate the model performances. (B) Plasma samples, collected from non-small-cell lung cancer and patients with benign lung nodules, were used to extract cell-free DNA (cfDNA). Whole genome sequencing was carried out and four different feature types, including fragment size ratio (FSR), fragment size distribution (FSD), breakpoint motif (BPM), and neomer, were extracted. For each feature type, 200 base models were constructed using an automated machine learning process with hyperparameter tuning based on the training cohort. The automated machine learning process utilized five different algorithms, including generalized linear model (GLM), gradient boosting machine (GBM), random forest (RF), deep learning (DL), and extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost). The top three models for each feature type with the highest area under the curves (AUCs) of fivefold cross-validation on the training cohort were selected, and their fivefold CV predictions were assembled into a matrix which was used by a second-layer RF algorithm to assemble into the final stack model.

autoML, automated machine learning; CV, cross-validation.

The study protocols were approved by the ethics committee of The First Hospital of China Medical University and in accordance with the international ethical standards agreed upon in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent. The blood samples were collected before the LDCT and surgical resection of the nodules, followed by pathological examination according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumor–node–metastasis (TNM) system (eighth edition).17

Sample collection, library preparation, and sequencing

The sample collection, library preparation, and sequencing were carried out according to the standard protocol of Nanjing Geneseeq Technology Inc., China, as previously reported.13 Peripheral blood (10 ml) was collected from the patients before the LDCT and surgical resection and kept in the EDTA blood collection tubes (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Samples were kept at 4°C for ≤2 hours before centrifugation at 1800g for 10 min at 4°C for plasma collection. Another centrifugation (16 000g, 10 min, 4°C) was carried out to remove any cell debris. The samples were then frozen, shipped to the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified and College of American Pathologists (CAP)-accredited clinical testing laboratory (Nanjing Geneseeq Technology Inc., China) on dry ice, and stored at −80°C until further analysis.

The Hamilton Microlab STAR automated liquid handling platform (Hamilton Company, Reno, NV) and QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (Qiagen, Netherlands) were used to extract cfDNA. The concentration of extracted cfDNA was measured with the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). About 5-10 ng of cfDNA per sample was then subjected to PCR-free WGS library construction using the KAPA Hyper Prep Kit (KAPA Biosystems). The library was constructed automatically on Biomek (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA), quantified using the KAPA SYBR FAST qPCR Master Mix (KAPA Biosystems, Wilmington, MA), and underwent paired-end sequencing on NovaSeq platforms (Illumina, San Diego, CA).

For bioinformatics analysis, raw sequencing data were trimmed by Trimmomatic as part of the quality control protocol.18 The qualified reads were then mapped onto the human reference genome (GRCh37/UCSC hg19) using the sequence aligner BWA19 after removal of PCR duplicates using the Picard toolkit (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/).

Fragmentomics feature generation

Raw sequencing data from the Illumina NovaSeq platform were first trimmed with Trimmomatic,18 followed by the removal of PCR duplicates using the Picard toolkit (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/). BWA was then used to map the trimmed and PCR duplicate-removed reads onto the human reference genome (GRCh37/UCSC hg19).19 Various in-house scripts then used the mapped reads to generate different fragmentomics features, including the FSR, FSD, BPM, and neomer.

The FSR profile, as previously reported, focuses on the proportions of short and long fragments across the human genome, as the cfDNA fragments originating from tumor cells were known to be aberrantly shorter.20 As previously reported, short fragments were defined as 100-150 bp, while long fragments were defined as 151-220 bp.9,10,13 The ratios of the short/long fragments for each sample were examined in 5-Mb bins across the human autosomes, which can mitigate potential sex bias. This resulted in a total of 1082 (541 bins × 2) FSR features from the 541 bins genomewide, which were then used for machine learning model construction. The FSD profile examined fragment length patterns at a higher resolution by grouping these cfDNA fragments into length bins of 5 bp ranging from 100 to 220 bp.8,13 The ratio of fragments in each bin was then calculated at arm level for human autosomes. The 24 bins on a total of 39 human autosomes contributed 936 (24 bins × 39 arms) FSD features to be utilized by the machine learning algorithms.

The BPM profile was adapted from the end motif initially reported by Jiang et al.7 in 2020. As previously reported, the BPM examined frequencies of the 6-bp motif at the 5′ breakpoints on the human reference genome hg19, which extended 3 bp to each direction. A total of 4096 (46) BPM features were generated for machine learning model construction.

Georgakopoulos-Soares et al.11 defined neomers as short DNA sequences that are recurrent in the tumor genomes yet missing in the human reference genome. By surveying the Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes (PCAWG) database (https://dcc.icgc.org/releases/PCAWG/), we identified a total of 977 recurrent single-nucleotide polymorphisms from 2577 samples obtained from patients with cancer. A total of 4616 neomers of 16-bp lengths were extracted using these recurrent single-nucleotide polymorphisms, which were then filtered against common population variants collected in the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD version 2),21 resulting in a total of 1758 final neomers. For each plasma sample, the FASTQ data were scanned for exact matches to the 16-bp neomer of interest. The neomer features were profiled as the ratio of neomer-detecting reads over the total reads and the read count of each of the 1758 neomers.

Machine learning model construction

The 237 patients in the training cohort, containing 193 patients with lung cancer and 44 patients with benign lung nodules, were used to train the machine learning model, while the validation cohort remained locked during the training process and was only used to evaluate the final machine learning model.

The machine learning model was constructed using a stacked ensemble algorithm on base learners (Figure 1B). To retrieve the optimal base learners, an autoML process utilized five different algorithms, including generalized linear model (GLM), gradient boosting machine (GBM), random forest (RF), deep learning (DL), and extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost). The autoML process was then started to construct a series of models and rank them based on the fivefold cross-validation results of the training cohort. For each feature type, the top 3 ranking models based on cross-validation AUCs were selected as the base learners. The cancer scores of the cross-validation were retrieved for all 12 (4 feature types × 3 top models) base learners and ensembled into a matrix, which was used as input for the RF algorithm to construct the final stacked ensemble model.

The validation cohort and an external cohort containing 99 patients (58 lung cancer and 41 benign nodules; Figure 1B) were used to evaluate the performance of the stacked ensemble machine learning model at the designed 90% sensitivity.

Statistical analysis

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed using the pROC package (version 1.17.0.1). Based on true-positive (TP), true-negative (TN), FP, and false-negative (FN) rates of cancer prediction, the sensitivity [TP/(TP + FN)], specificity [TN/(TN + FP)], positive predictive value [TP/(TP + FP)] and negative predictive value [TN/(TN + FN)], accuracy [(TP + TN)/(TP + FP + TN + FN)], and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using the epiR package (version 2.0.19). Propensity score matching analysis of age, gender, and smoking history within the validation cohort was carried out using the MatchIt package (version 4.2.0). All statistical analyses were carried out in R (version 3.6.3; R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Participant characteristics in the cohorts

This study enrolled a total of 355 patients who presented pulmonary symptoms and underwent resection surgery due to suspicious LDCT results, including 289 with malignant nodules and 66 with benign nodules. As shown in Supplementary Table S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103595, the training cohort consisted of 237 patients, including 193 malignant and 44 benign nodules. The other 118 patients (96 malignant and 22 benign nodules) were included in the validation cohort.

As shown in Supplementary Table S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103595, the mean age for the patient with malignant or benign nodules in the training cohort was 57.2 (31-79) years and 53.9 (24-73) years, respectively. The validation cohort’s mean age for cancer and benign nodules was 56.4 (31-73) years and 51.4 (20-69) years, respectively. The percentages of female patients were similar in the training (63.7% for the cancer group and 52.3% for the benign nodule group) and validation (65.6% for the cancer group and 54.5% for the benign nodule group) cohorts. Patients with cancer enrolled in the training and validation cohorts mainly were stage 0 (14.5% and 17.7%, respectively) and stage I (71.5% and 71.9%, respectively), while the stage information was unavailable for a few patients (6.2% and 5.2%, respectively), according to Supplementary Table S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103595.

As shown in Supplementary Table S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103595, ground-glass opacity (GGO) nodules were predominant in the cancer group, accounting for 52.3% (n = 101) of the training cohort and 54.2% (n = 52) of the validation cohort. In comparison, pure solid nodules comprised only 9.9% (n = 19) in the training cohort and 6.2% (n = 6) in the validation cohort. Mixed GGO nodules made up 37.8% (n = 73) and 39.6% (n = 38) of the training and validation cohorts, respectively. In the benign nodule group, GGO, pure solid nodules, and mixed GGO nodules accounted for 27.3% (n = 12), 18.2% (n = 8), and 54.5% (n = 24) of the training cohort, respectively. In the validation cohort, the percentages of benign nodules were 31.8% for GGO, 9.1% for pure solid, and 59.1% for mixed GGO (Supplementary Table S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103595).

Machine learning model for predicting malignancy

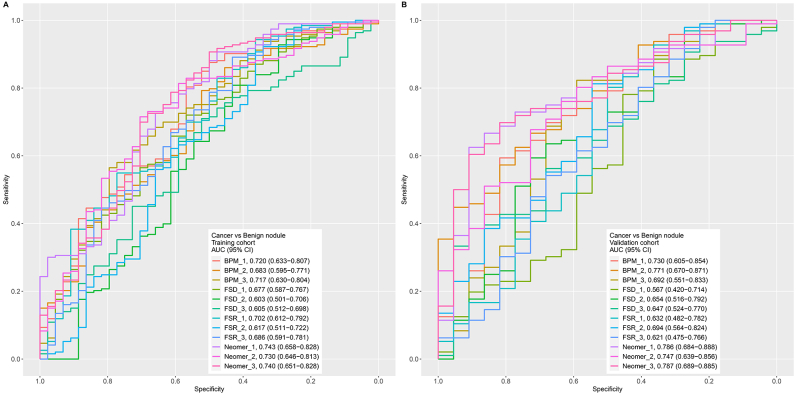

autoML base model construction

We first constructed base models for predicting the malignant status of lung nodules using various fragmentomics features, including FSR, FSD, BPM, and neomer. For each feature, 200 base models were constructed using the training cohort by an autoML process employing five algorithms, including GLM, GBM, RF, DL, and XGBoost. The ROC curves for these 200 base models were generated using prediction scores from fivefold cross-validation on the training cohort. These models were then ranked by AUC from the highest to the lowest, and the top three base models for each feature type were selected.

As shown in Supplementary Figure S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103595, the base models showed various levels of predictive power among the four different feature types, with BPM and neomer performing better than FSR and FSD. The neomer showed the best performances among these base models, showing AUC ranging from 0.730 (95% CI 0.646-0.813) to 0.743 (95% CI 0.658-0.828) for training cohort cross-validation (Supplementary Figure S1A, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103595). Moreover, the other three feature types all showed reasonable ability to distinguish between malignant and benign nodules, with the top performing base models all exceeding 0.65 AUC (FSR: 0.702, 95% CI 0.612-0.792; FSD: 0.677, 95% CI 0.587-0.767; and BPM: 0.720, 95% CI 0.633-0.807) cross-validating the training cohort (Supplementary Figure S1A, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103595). The performances of these base models on the validation cohort were also investigated, as illustrated in Supplementary Figure S1B, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103595, which showed the same trend, wherein neomer (top AUC: 0.787, 95% CI 0.689-0.885) and BPM (top AUC: 0.771, 95% CI 0.670-0.871) outperformed both FSR (top AUC: 0.694, 0.564-0.824) and FSD (top AUC: 0.653, 95% CI 0.515-0.792).

Final ensemble stacked model

These 12 base models were then used to create the final ensemble stacked machine learning model. The fivefold cross-validation prediction scores for the training cohort were assembled into a matrix, which was subsequently used as the input to create an RF model.

As shown in Figure 2A, the final ensemble stacked model showed an excellent ability to distinguish the malignant and benign nodules, achieving AUCs of 0.848 (95% CI 0.785-0.910) and 0.857 (95% CI 0.782-0.932) in the training and validation cohorts, which were higher compared with the base models. The stacked model achieved an excellent specificity of 68.2% (95% CI 45.1% to 86.1%) at the targeted 90% sensitivity (89.6%; 95% CI 81.7% to 94.9%) in the validation cohort, as shown in Table 1. The overall accuracy of the stacked model reached 85.6% (95% CI 77.9% to 91.4%).

Figure 2.

Model evaluation using the training cohort (fivefold cross-validation) and the validation cohort. (A) ROC curves using the training cohort (fivefold cross-validation) and the validation cohort. (B) Box plot illustrating cancer score distribution in the benign nodule and lung cancer groups in the validation cohort. The cut-offs are shown as dotted lines. (C) Violin plot illustrating cancer score distribution in the benign nodule group and very early (stage 0), early (stages I and II), late (stages III and IV), and unknown stages of lung cancer groups. (D) ROC curves using age-, sex-, and smoking history-matched subset in the training cohort (fivefold cross-validation) and the validation cohort. ∗∗∗, P ≤ 0.001.

AUC, area under the curve; BN, benign nodule; CI, confidence interval; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; sens, sensitivity.

Table 1.

Evaluating model performances in the three cohorts at targeted 90% specificity

| Training cohort | Actual |

|

|---|---|---|

| Lung cancer | Benign nodule | |

| Predict, n | ||

| Lung cancer | 175 | 18 |

| Benign nodule | 18 | 26 |

| Sensitivity (95% CI) | 90.7% (85.7% to 94.4%) | |

| Specificity (95% CI) | 59.1% (43.2% to 73.7%) | |

| PPV (95% CI) | 92.5% (85.1% to 96.9%) | |

| NPV (95% CI) | 59.1% (43.2% to 73.7%) | |

| Accuracy (95% CI) |

84.8% (79.6% to 89.1%) |

|

| Validation cohort |

Actual |

|

|---|---|---|

| Lung cancer | Benign nodule | |

| Predict, n | ||

| Lung cancer | 86 | 7 |

| Benign nodule | 10 | 15 |

| Sensitivity (95% CI) | 89.6% (81.7% to 94.9%) | |

| Specificity (95% CI) | 68.2% (45.1% to 86.1%) | |

| PPV (95% CI) | 92.5% (85.1% to 96.9%) | |

| NPV (95% CI) | 60% (38.7% to 78.9%) | |

| Accuracy (95% CI) |

85.6% (77.9% to 91.4%) |

|

| External test cohort |

Actual |

|

|---|---|---|

| Lung cancer | Benign nodule | |

| Predict, n | ||

| Lung cancer | 52 | 15 |

| Benign nodule | 6 | 26 |

| Sensitivity (95% CI) | 89.7% (78.8% to 96.1%) | |

| Specificity (95% CI) | 63.4% (46.9% to 77.9%) | |

| PPV (95% CI) | 77.6% (65.8% to 86.9%) | |

| NPV (95% CI) | 81.2% (63.6% to 92.8%) | |

| Accuracy (95% CI) | 78.8% (69.4% to 86.4%) | |

CI, confidence interval; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

A violin plot was generated using the cancer prediction scores of the lung cancer group and the benign nodule group in the validation cohort, with a higher cancer prediction score representing a higher probability of cancer. As shown in Figure 2B, the cancer prediction scores were significantly higher in the lung cancer group compared with the benign nodule group (P = 1.3 × 10−07, Wilcoxon test). Moreover, the cancer prediction scores showed a gradual increase among the benign nodule, very early (stage 0), early (stages I and II), and late stage (stages III and IV) groups in the validation cohort (Figure 2C). Finally, a propensity score matching analysis was carried out further to eliminate the potential impact of the imbalanced age, sex, and smoking history on our model’s performance. A subset containing 96 patients (65 lung cancer and 31 benign nodules) was selected from the training cohort with matching age, sex, and smoking history. Likewise, 37 patients, including 24 with lung cancer and 13 with benign nodules, were selected as a subset of the validation cohort. As shown in Figure 2D, these age/sex/smoking matched subsets showed equivalent distinguishing power in the training cohort (AUC 0.842, 95% CI 0.756-0.928), while the AUC in the validation subset was even higher at 0.873 (95% CI 0.762-0.984).

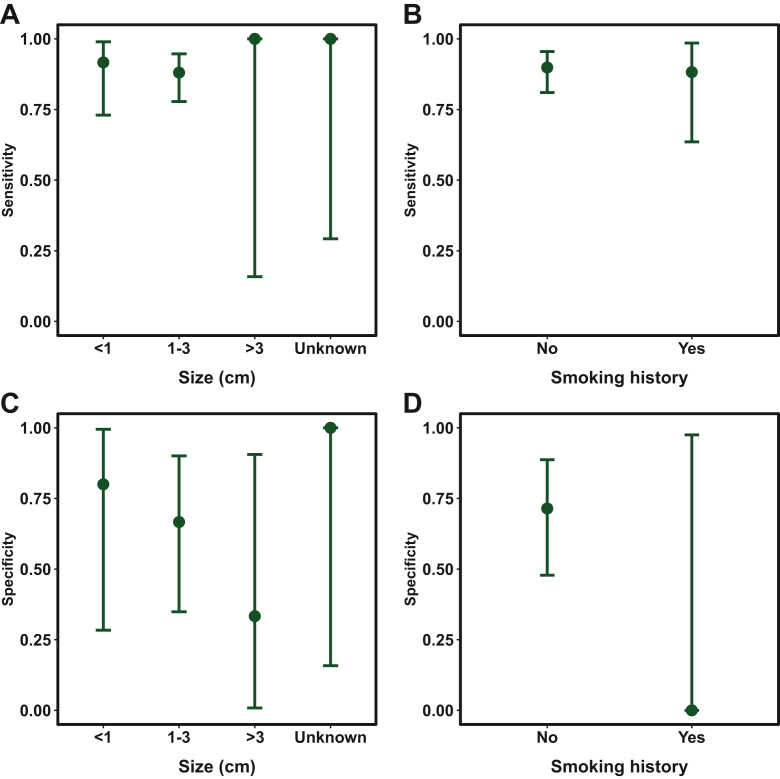

Subgroup analysis

We then evaluated the model’s performances for different subgroups to investigate whether certain subgroups were error-prone. As shown in Figure 3A and B, the sensitivities for detecting various subgroups of nodule size (<1 cm: 91.7%; 1-3 cm: 88.1%; >3 cm: 100%; unknown: 100%) and smoking history (Yes: 88.2%; No: 89.9%) all remained high among the lung cancer group in the validation cohort. The specificity for identifying different subgroups of benign nodules decreased as the size increased (<1 cm: 80.0%, 1-3 cm: 66.7%, >3 cm: 33.3%, Unknown: 100%), as illustrated in Figure 3C. The sensitivity for identifying the nonsmokers among the benign nodule subgroup reached 71.4% in the validation cohort, compared with 0% for the smokers, which is likely contributed by the limited number (n = 1) of this subgroup (Figure 3D). A violin plot of the cancer prediction scores showed our model’s excellent performance across different histological subgroups (Supplementary Figure S2, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103595).

Figure 3.

Evaluating sensitivity within lung cancer and specificity within benign nodule subgroups. Plots of sensitivities for detecting lung cancer for different subgroups of (A) size and (B) smoking history and plots of specificities for detecting benign lung nodules for different subgroups of (C) size and (D) smoking history. The error bars represent the 95% confidence interval.

In addition, our model demonstrated robustness across subgroups with varying nodule opacities. According to Supplementary Table S2, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103595, in the training cohort for the pure GGO nodule subgroup, the sensitivity was 90.1% at a specificity of 75%. This was in comparison to the validation cohort, where the sensitivity was 90.4% at a specificity of 100%. For the pure solid nodule subgroup, the sensitivities were 90.4% and 86.8% at specificities of 50.0% and 53.8% in the training and validation cohorts, respectively, as shown in Supplementary Table S2, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103595. Moreover, the model was equally effective in distinguishing between malignant and benign nodules with mixed opacities, achieving a sensitivity of 94.7% at a specificity of 62.5% in the training cohort, and a sensitivity of 100% at a specificity of 50.0% in the validation cohort.

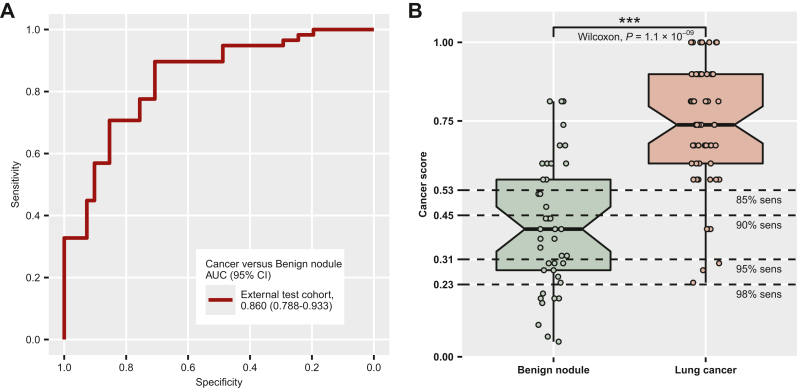

Performance evaluation using an external test cohort

To further validate our predictive model, we introduced an external cohort containing 99 patients (58 lung cancer and 41 benign nodules), using preliminary data collected for a different study at the same hospital. As shown in Figure 4A, our model was able to distinguish the malignant nodules from the benign ones, reaching an AUC of 0.860 (95% CI 0.788-0.9333). A violin plot showed a similar pattern that the cancer prediction scores were significantly higher in the lung cancer group (P = 1.1 × 10−09, Wilcoxon test, Figure 4B). However, after applying the cut-off for the cancer score cut-off (0.45) determined by the training cohort (Table 1), we observed a slight drop in performance in terms of specificity (63.4%, 95% CI 46.9% to 77.9%) and sensitivity (89.7%, 95% CI 78.8% to 96.1%).

Figure 4.

Model evaluation using an external test cohort. (A) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve using the external test cohort. (B) Box plot illustrating cancer score distribution in the benign nodule and lung cancer groups in the external test cohort. The cut-offs are shown as the dotted lines. ∗∗∗, P ≤ 0.001.

AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval; sens, sensitivity.

Evaluating model performance under various cut-offs

We also examined the performances of our model using different cut-offs set at various sensitivities. As shown in Supplementary Table S3, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103595, the cut-offs were set to 0.5268, 0.4504, 0.3139, and 0.2262 to ensure sensitivities in the training cohort reached 85%, 90%, 95%, and 98%, respectively.

When the cut-off was set to 0.5268, our stacked model showed higher specificities of 68.2% and 70.7% in the independent validation (82.3% sensitivity) and external test cohorts (89.7% sensitivity), compared with the 63.6% specificity in the training cohort (87.6% sensitivity), as shown in Supplementary Tables S3 and S4, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103595. However, when more stringent cut-offs were applied (0.3139 and 0.2262), the specificities decreased to 31.8% (94.8% sensitivity) and 22.7% (97.9% sensitivity) in the independent validation cohort, as well as 36.6% (94.8% sensitivity) and 19.5% (100% sensitivity) in the external test cohort, compared with the specificities of 40.9% (94.8% sensitivity) and 29.5% (98.4% sensitivity) in the training cohort (Supplementary Tables S3 and S4, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103595). Our model showed an increase in specificity in all three cohorts compared with the LDCT method, which had FP results for the entire benign nodules (0% specificity).

Discussion

The use of LDCT for early screening of lung cancer has been shown to reduce cancer mortality.5,6 However, a major issue with this method is the high rate of FP results.5,6 According to the National Lung Screening Trial, an invasive procedure, such as thoracotomy, mediastinoscopy, or bronchoscopy, failed to confirm the lung cancer status among 457 of 1075 (∼42.5%) cases based on a positive LDCT screening result,5 with ∼25% later confirmed as benign.6 These invasive procedures caused discomfort for the patients and resulted in complications for 88 of the 457 cases.5 Unfortunately, six patients died within 60 days of receiving an invasive diagnostic procedure. Therefore there is a need for an accurate, noninvasive method that can distinguish true lung cancer from radiologically suspicious, yet benign lung nodules to assist in clinical diagnosis.

Our model excels in distinguishing between malignant and benign nodules in a group of patients who have all presented pulmonary symptoms and subsequently tested positive by the LDCT screening. Rather than replacing the current gold-standard LDCT screening, our model aims to minimize unnecessary intrusive interventions by reducing FP test results. While the sensitivity for detecting lung cancer reached 100%, LDCT had an extremely poor FP rate (100%) or 0% specificity for identifying benign nodules among patients from the three cohorts used in this study. By contrast, our predictive model reached specificities of ∼63.4%-68.2% at 90% sensitivity. The FP LDCT results led to a total of 107 surgical resections, which were later confirmed as benign by pathological examinations. Our assay can be utilized in clinical settings after positive LDCT screening to guide surgical decisions, potentially reducing unnecessary invasive interventions by up to 68.2%.

When comparing our model with existing cfDNA fragmentomics cancer detection assays, the key difference lies in potential clinical usage. Previous studies on early cancer detection were primarily aimed at identifying patients with cancer from healthy individuals, serving as large-scale first-line cancer screening tools. Because of different clinical settings, there are some variations in cut-off selections. As the prevalence of cancer in the targeted groups is relatively low, a high specificity cut-off is necessary to avoid unnecessary medical examinations caused by FP predictions for healthy controls.22 However, our model is specifically designed for high-risk patients who have already received positive LDCT test results, indicating a high likelihood of cancer. In this clinical setting, we believe that the cost of an FN prediction for patients with cancer outweighs the cost of an FP prediction for patients Therefore our model needed to be highly sensitive, and fixing the sensitivity at 90% was deemed more appropriate for clinical utilization.

Another novelty of our fragmentomics cancer early detection assay is the utilization of autoML compared with existing studies.8,9,13 The stacked ensemble approach has demonstrated great potential in early cancer detection. However, the performance of the final model depends on its base models. Hyperparameter tuning can substantially increase model performance and is often considered the most crucial step for model construction. However, manual hyperparameter optimization requires extensive expertise and is time-consuming. The autoML machine learning process, which can automatically select hyperparameters, has demonstrated superior or equal performance compared with manual tuning.23

However, our assay still faces several limitations. One of the biggest challenges is the relatively small cohort size, especially for the benign nodules with FP LDCT results, limiting the power of our diagnostic model. Moreover, because the validation and test cohorts are from the same hospital, a multicenter study is needed to validate our assay further. In addition, it is worth exploring whether our assay, which currently uses low-pass WGS, could be expanded onto existing clinical panels. As Helzer et al.24 have recently shown, targeted cfDNA panels can be utilized to analyze fragmentation patterns in cancer detection, potentially reducing sequencing-related costs.

Overall, our newly developed noninvasive cfDNA fragmentomics assay offers a promising method for distinguishing accurately between malignant and benign pulmonary nodules, effectively reducing the high rate of FPs seen in LDCT screenings. This assay not only aims to improve diagnostic accuracy but also to decrease the need for unnecessary invasive procedures. This minimizes patient discomfort and lightens the load on healthcare systems, making it a potentially valuable addition to current LDCT screening techniques in clinical settings.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and family members who gave their consent on presenting the data in this study as well as the investigators and research staff involved in this study.

Funding

None declared.

Disclosure

WT, HB, SC, and XW are employees of Nanjing Geneseeq Technology Inc., Nanjing, Jiangsu, China. The remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Data Sharing

The datasets used and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

All study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of The First Hospital of China Medical University and conducted in accordance with international standards of good clinical practice. Written informed consents were provided by all patients.

Consent for Publication

The manuscript was read and approved by all contributing authors.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT 4.0 (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA) to improve readability and language for the manuscript. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and took full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Supplementary data

Supplementary Figure.

S1

Supplementary Figure S2

References

- 1.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferlay J., Colombet M., Soerjomataram I., et al. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: an overview. Int J Cancer. 2021 doi: 10.1002/ijc.33588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2018. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Available at https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2018/. Accessed June 19, 2024.

- 5.National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Aberle D.R., Adams A.M., et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Church T.R., Black W.C., et al. Results of initial low-dose computed tomographic screening for lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(21):1980–1991. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang P., Sun K., Peng W., et al. Plasma DNA end-motif profiling as a fragmentomic marker in cancer, pregnancy, and transplantation. Cancer Discov. 2020;10(5):664–673. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang X., Wang Z., Tang W., et al. Ultrasensitive and affordable assay for early detection of primary liver cancer using plasma cell-free DNA fragmentomics. Hepatology. 2022;76(2):317–329. doi: 10.1002/hep.32308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma X., Chen Y., Tang W., et al. Multi-dimensional fragmentomic assay for ultrasensitive early detection of colorectal advanced adenoma and adenocarcinoma. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14(1):175. doi: 10.1186/s13045-021-01189-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cristiano S., Leal A., Phallen J., et al. Genome-wide cell-free DNA fragmentation in patients with cancer. Nature. 2019;570(7761):385–389. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1272-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Georgakopoulos-Soares I., Barnea O.Y., Mouratidis I., et al. Leveraging sequences missing from the human genome to diagnose cancer. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.08.15.21261805. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mathios D., Johansen J.S., Cristiano S., et al. Detection and characterization of lung cancer using cell-free DNA fragmentomes. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):5060. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24994-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bao H., Wang Z., Ma X., et al. Letter to the editor: An ultra-sensitive assay using cell-free DNA fragmentomics for multi-cancer early detection. Mol Cancer. 2022;21(1):129. doi: 10.1186/s12943-022-01594-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo W., Chen X., Liu R., et al. Sensitive detection of stage I lung adenocarcinoma using plasma cell-free DNA breakpoint motif profiling. EBioMedicine. 2022;81 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.104131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kohl M. MKmisc: miscellaneous functions from M. Kohl. Matthias Kohl. 2021. https://github.com/stamats/MKmisc Available at.

- 16.MacMahon H., Naidich D.P., Goo J.M., et al. Guidelines for management of incidental pulmonary nodules detected on CT images: from the Fleischner Society 2017. Radiology. 2017;284(1):228–243. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017161659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amin M.B., Greene F.L., Edge S.B., et al. The eighth edition AJCC cancer staging manual: continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(2):93–99. doi: 10.3322/caac.21388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bolger A.M., Lohse M., Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(15):2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li H., Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(14):1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang P., Chan C.W., Chan K.C., et al. Lengthening and shortening of plasma DNA in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(11):E1317–E1325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500076112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karczewski K.J., Francioli L.C., Tiao G., et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature. 2020;581(7809):434–443. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2308-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu M.C., Oxnard G.R., Klein E.A., Swanton C., Seiden M.V., CCGA Consortium Sensitive and specific multi-cancer detection and localization using methylation signatures in cell-free DNA. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(6):745–759. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waring J., Lindvall C., Umeton R. Automated machine learning: review of the state-of-the-art and opportunities for healthcare. Artif Intell Med. 2020;104 doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2020.101822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Helzer K.T., Sharifi M.N., Sperger J.M., et al. Fragmentomic analysis of circulating tumor DNA-targeted cancer panels. Ann Oncol. 2023;34(9):813–825. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2023.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure S2