Abstract

Despite the protective nature of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and brain-protecting tissues, some types of CNS injury or stress can cause cerebral cytokine production and profound alterations in brain function. Neuroinflammation, which can also be accompanied by increased cerebral cytokine production, has a remarkable impact on the pathogenesis of many neurological illnesses, including loss of BBB integrity and ischemic stroke, yet effective treatment choices for these diseases are currently lacking. Although little is known about the brain effects of Metformin (MF), a commonly prescribed first-line antidiabetic drug, prior research suggested that it may be useful in preventing BBB deterioration and the increased risk of stroke caused by tobacco smoking (TS). Therefore, reducing neuroinflammation by escalating anti-inflammatory cytokine production and declining pro-inflammatory cytokine production could prove an effective therapeutic strategy for ischemic stroke. Hence, the current investigation was planned to explore the potential role of MF against stroke and TS-induced neuroinflammation and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. Our studies revealed that MF suppressed releasing pro-inflammatory mediators like tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) by aiming at the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signaling pathway in primary neurons and astrocytes. MF also upregulated anti-inflammatory mediators, like interleukin-10 (IL-10), and interleukin-4 (IL-4), by upregulating the Nrf2-ARE signaling pathway. Adolescent mice receiving MF along with TS exposure also showed a notable decrease in NF-κB expression compared to the mice not treated with MF and significantly decreased the level of TNF-α, IL-1β, MCP-1, and MIP-2 and increased the levels of IL-10 and IL-4 through the activation of Nrf2-ARE signaling pathway. These results suggest that MF has anti-neuroinflammatory effects via inhibiting NF-κB signaling by activating Nrf2-ARE. These studies support that MF could be a strong candidate drug for treating and or preventing TS-induced neuroinflammation and ischemic stroke.

Keywords: Neuroinflammation, Tobacco smoke, ROS, Cytokines, Ischemic stroke, Adolescent mice

1. Introduction

It has long been recognized that several neurological and neurodegenerative disorders are associated with a pathophysiological process called neuroinflammation [[1], [2], [3]]. In addition to inflammation, the brain tissues are especially susceptible to oxidative stress (OS), which is a consequence of a lack of balance between the antioxidant defense system's capacity and the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [4]. Crucially, redox imbalance is always linked to cellular activities during inflammatory responses [5], and the generation of oxidants by glial cells is linked to several CNS disorders [6]. Excessive production of intracellular and extracellular ROS can cause direct damage to cells, but it can also activate immune pathways in the brain. These pathways can then intricate various harmful inflammatory mediators, including more ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), creating a vicious cycle [7,8].

As per the results of the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2019 study, stroke is the second most deadly disease and the third most common cause of an increase in total disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) worldwide [9,10]. It is commonly known that 62.4 % of all stroke cases are caused by ischemic stroke [9]. Even though ischemic stroke is one of the most prevalent diseases in older persons, new research shows that young adults (aged between 18 and 49), particularly those living in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), are more likely to experience this condition and accounts for 10 %–14 % of all stroke cases [11,12]. Tobacco smoking (TS) is one of the main preventable risk factors for cerebrovascular disease and the biggest cause of avoidable death in the United States. Smoking is associated with one-fifth of all stroke deaths that occur in people under 65 [13]. Although there has been a slight decrease in smoking in recent years, it is concerning that 18 % of adult US citizens currently smoke [14]. Approximately 90 % of American adults who smoke regularly have tried cigarettes by the age of 18, and 98 % had done so by the age of 26. Each day in the U.S., roughly 1500 adolescents aged 17 or under inhale their first cigarette [15]. The National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS) for 2022 revealed that 16.2 % of middle and high school students said they currently used tobacco products. In addition to that, dual usage, or the use of numerous tobacco products by young people, is also very familiar [16].

TS is known to increase not only the threat of stroke [17] but also Alzheimer's disease [18], depression [19], cognitive impairment, and vascular dementia [20]. These smoking-related pathogenic effects are attributable to the raising production of ROS [21,22], proinflammatory activity [23], and BBB impairment [24] caused by TS. Nicotine and other ROS (such as epoxides, nitrogen dioxide, H2O2, peroxynitrite—ONOO−) are among the nearly 7000 compounds found in TS. ROS pass through the alveolar wall of the lung into the systemic circulation [25], resulting in enhanced oxidative damage and BBB impairment at the cerebrovascular level through alterations of the tight junctions (TJs) and on the activation of proinflammatory pathways [26,27].

A master transcription factor, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), is considered the protector of redox homeostasis and a potential therapeutic target for managing stroke and other inflammation-related disorders [[28], [29], [30]]. Along with being essential for cellular defense against oxidative stress, this signaling pathway also negatively regulates inflammatory responses. Research has previously shown that Nrf2 plays a key role in controlling the activation of microglia in response to brain inflammation and stroke [28,30]. Furthermore, in a range of experimental settings, Nrf2 could counteract nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB)-driven inflammatory response by competing with NF-κB p65 for their common transcriptional co-activator p300/CREB binding protein (CBP) at the transcriptional level [31,32].

Earlier research from our group has demonstrated that MF, a commonly given first-line antidiabetic medication, can lower stress and suppress inflammatory responses before and after stroke injury [33,34]. Our group's earlier research has also shown that Nrf2 functions to maintain BBB integrity [35], as well as the alteration of gene transcription and or translation associated with the Nrf2-ARE pathways, were probably the most prevalent in human BBB microvascular endothelial cells that were exposed to TS [36]. Most of our earlier research shows a connection between tobacco smoke's pro-inflammatory properties and BBB deterioration at the cellular immune levels (endothelial and intravascular). However, the dynamics of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine markers and regulation of inflammation upon exposure of primary neuron-astrocytes directly from TS or ischemic hypoxic conditions and treatment with MF have not been sufficiently studied. To our knowledge, we are the first to closely monitor how MF affects primary neurons and astrocytes during TS and ischemic stroke-induced neuroinflammation. Furthermore, compared to adult mice, fewer studies have been conducted on adolescent mice to investigate the effect of TS exposure on the Nrf2-ARE signaling pathway which plays a major role in counteracting the pro-oxidative and pro-inflammatory effects of smoking. This study showed that MF exerts anti-neuroinflammatory effects in primary neurons by reducing ROS generation after OGD/R and TS exposure. MF also promoted the expression of antioxidant enzymes, restored the proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine dynamics, and inhibited NF-кB activation in vitro and in vivo. These findings corroborate and expand upon several previous findings.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Primary neuron isolation and culture

Mouse primary neurons were extracted and grown with a small adjustment based on the earlier description [37]. The Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center's (TTUHSC) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) in Lubbock, Texas, authorized this protocol (Protocol# 08017). Briefly, cerebral cortices were isolated from E16 embryos of CD-1 mice (Charles River Laboratories, Inc., Wilmington, MA, USA; Cat# CRL: 22, RRID: IMSR_CRL: 22) and dissected in Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS) supplemented with 250 μg/mL gentamycin (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH, USA; Cat# MT30005CR). Meninges were separated carefully, and meninges-free cortices cut into pieces were then digested for 15 min at 37 °C in 0.25 % trypsin, then neutralized with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS). The dissociated cell suspensions were counted using a cell counter and seeded (0.75 × 104 per cm2 surface area) into 6- or 96-well plates pre-coated with poly-d-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA; Cat# P6407). The cells were then cultured in Neurobasal medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA; Cat# 21103049) which were supplemented with 0.5 mM Glutamax (Thermo Fisher; Cat# 35050061), 25 μg/mL gentamicin, and 2 % B27 (Thermo Fisher; Cat# 17504044) and maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5 % CO2 in the air. Following an overnight incubation period, the entire medium was discarded and replaced with a new Neurobasal medium. Following that, half of the medium was replaced every two days interval. A summary of the study design utilizing primary cortical neurons in in vitro experiments can be found in Fig. 1 (A).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the study designs. (A) in vitro experiments in neurons, (B) in vitro experiments in astrocytes, (C) in vivo experiments.

2.2. Primary astrocyte isolation and culture

Using previously described procedures, primary astrocytes were isolated from the cerebral cortices of a CD-1 mouse pup (Charles Rivers Laboratory), which was one day old [38]. Following brain isolation, meninges were removed from cerebral cortices, and cortices devoid of meninges were put in HBSS, which did not contain calcium and magnesium but contained gentamycin (250 μg/mL). Subsequently, cortices were digested at 37 °C for 15 min using 0.25 % trypsin and then neutralized with Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM), containing 10 % FBS and 1 % PS solution. After that, cells were plated into a T75 flask for culture, and the media was changed every two or three days until confluency was reached. A summary of the study design utilizing primary astrocytes in in vitro experiments can be found in Fig. 1 (B).

2.3. Oxygen and glucose deprivation/Reoxygenation

Mature neurons and astrocytes were treated with or without MF, followed by exposure to Oxygen Glucose Deprivation (OGD) and reoxygenation. Cells were exposed to ' 'Earle's balanced salt solution (140 mM NaCl, 5.36 mM KCl, 0.83 mM MgSO4, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1.02 mM NaH2PO4, and 6.19 mM NaHCO3) to create an aglycemic condition. Hypoxia (1 % oxygen) was induced [39] by incubating the cells in a customized hypoxic polymer glove box (Coy Laboratories, Grass Lake, MI, USA), which was infused with 95 % N2 and 5 % CO2, and the temperature was maintained at 37 °C. MF was added to ' 'Earle's balanced salt solution at the start of OGD in the treatment group. The OGD-exposed medium was replaced by the respective medium for neurons and astrocytes containing the same MF concentration, and cells were returned to a cell culture incubator for 24 h for reoxygenation (OGD/R). Primary neurons and astrocyte cultures grown in conventional conditions (specified above) served as normoxic controls.

2.4. Tobacco smoke extract preparation

By following previously reported techniques [26,36], soluble TS extracts were made using a Single Cigarette Smoking Machine (SCSM, CH Technologies Inc., Westwood, NJ, USA) under the FTC standard smoking protocol (35 ml draw, 2 s puff length, 1 puff per 60 s). Fresh extracts were prepared for every cycle and diluted to 5 % in the culture media [36,40].

2.5. In vivo experiment

IACUC, TTUHSC, Lubbock, Texas approved the animal protocol for this study. C57BL/6 J adolescent mice (40 days old) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories, which were then divided into two major groups: control and TS exposed, and the groups were again divided into two subgroups, including MF-treated and saline-treated. Mice from different groups were exposed to oxygenated air alone or TS vapor mixed with oxygenated air (via direct inhalation), 6 times/day; 2 cigarettes/hour, 6–8 h/day, 7 days/week for 2 weeks following International Organization for Standardization/Federal Trade Commission (ISO/FTC) standard smoking protocol (35 ml draw, 2s puff duration, 1 puff per 60 s). Single Cigarette Smoking Machines (SCSM, CH Technologies Inc., Westwood, NJ, USA) were utilized to generate TS vapor following previously published methods [26]. MF (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) powder was dissolved in sterile saline at a concentration of 30 mg/ml and administered daily (via intraperitoneal Injections (IP) of 200 mg/kg [34,40,41] to control mice as well as mice exposed to TS for 14 days. After completion of 14 days of exposure, mice were weighed and sacrificed. The plasma and brain samples of mice from different groups were collected and stored at −80 °C for further analysis. A summary of the study design for in vivo experiments can be found in Fig. 1C.

2.6. MTS cell viability assay

Using the CellTiter 96 kit Aqueous assay (Promega) and the supplied manufacturer's instructions, the MTS (dimethylthiazol carboxymethoxyphenyl sulfophenyl tetrazolium) assay was used to determine cell viability with minor modifications. Primary neurons and astrocytes were seeded into separate 96-well plates. Following confluency, cells were treated with various doses of Metformin (1 μM, 10 μM, 100 μM, 200 μM, 500 μM, 1 mM, and 2 mM) for 24 h. Following incubation, the previous media from each well was replaced with 100 μl of fresh new media, and 20 μl of reagent solution was added and incubated for another 2 h until the solution turned a dark brown color. A fluorescent microplate reader was used to measure the absorbance of formazan at 490 nm. The values were calculated using the percentage of the control value.

2.7. Quantitative real-time PCR

RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was used to extract total RNA from primary neurons, astrocytes, and tissue collected from the cortex region of the brain of adolescent mice, as previously reported [42]. RNA concentration was measured using a nanodrop machine, and 1 μg of RNA was taken for converting into cDNAs using iscript TM Reverse Transcription Supermix (Cat # 170–8841, Bio-Rad, United States). Thermal Cycler CFX96 TM Real-Time System (BIO-RAD, USA) was utilized for analysis and quantification, and iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Cat # 1725121, Bio-Rad, USA) was utilized for RT-PCR. The relative mRNA level was calibrated against GAPDH, and the 2−δδCt technique was utilized to ascertain the fold difference between the control and treatment groups. All the primer sets were acquired from Invitrogen, except those for IL-10, which were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT). Table 1 displays the primer sequences that were utilized to amplify each gene. Every primer originates from a mouse source.

Table 1.

Primer sequences for TNF-α, IL-1β, NF-кB, Nrf2, IL-4, IL-10, and GAPDH.

| Target gene | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | 5՛-AGCCCACGTCGTAGCAAACCAC-3՛ | 5՛-AGGTACAACCCATCGGCTGGCA-3՛ |

| IL-1β | 5՛-CCTGCAGCTGGAGAGTGTGGAT-3՛ | 5′-CCTGGGGCATCACTTCTACC-3′ |

| NF-кB | 5′-TTACCTCAGCGTGTGACGAG-3′ | 5′-ACAGGTAGCAAAGCCGAACA-3′ |

| Nrf2 | 5′-CAGTGCTCCTATGCGTGAA-3′ | 5′-GCGGCTTGAATGTTTGTC-3′ |

| IL-4 | 5՛-TGGGTCTCAACCCCCAGCTAGT-3՛ | 5՛-TGCATGGCGTCCCTTCTCCTGT-3՛ |

| IL-10 | 5′-CAGTACAGCCGGGAAGACAA-3′ | 5′-CCTGGGGCATCACTTCTACC-3′ |

| GAPDH | 5՛-ACTCACGGCTTCAACG-3՛ | 5՛-CCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCGTA-3՛ |

2.8. Western blot

Control or OGD/R and TS exposed as well as MF-pretreated primary neurons and astrocytes, were lysed using RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor to isolate protein lysate. Adolescent mice, either vehicle-treated or TS-exposed and also treated with MF, were sacrificed. The brains were collected, homogenized, and then lysed in the same way as we did for cells to isolate protein lysate from tissue. The protein concentration of the cells and tissue lysate was calculated using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay. Protein samples (25–30 μg) were loaded and separated using a 10 % Tris-glycine polyacrylamide precast gel (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA; Cat# 4568034) and then transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (BIO-RAD; Cat# 1704272) using a Trans-Blot Turbo transfer system (BIO-RAD). Later, the membranes were incubated in a blocking buffer (0.2 % Tween-20 containing Tris-buffered saline (TBST) with 5 % bovine serum albumin) for 2 h to block the nonspecific protein bands at room temperature. Membranes were then incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-NRF2 antibody (1:1000, Invitrogen; Cat# PA5-88084), mouse monoclonal anti-NQO1 antibody (1:10,000, Abcam; Cat# AB80588), rabbit monoclonal anti-HO1 antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling; Cat# E6Z5G), rabbit monoclonal anti- NF-κB antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling; Cat# D14E12), and mouse monoclonal anti-beta-actin (β-actin) antibody (1:10000 Millipore Sigma; Cat# A5441) in TBST with 5 % bovine serum albumin at 4 °C overnight. After 3 times washing with TBST for 15 min each cycle, membranes were incubated with anti-rabbit (Sigma Aldrich; Cat# GENA934- 1 ML, RRID: AB_2722659) or anti-mouse (Sigma Aldrich; Cat# GENXA931-1 ML, RRID: AB_772209) IgG-horseradish peroxidase secondary antibody (1:10000) in TBST with 5 % bovine serum albumin for 2 h at room temperature. After 3 times 15 min wash with TBST, the protein signals were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence detecting reagents (Millipore, Sigma Aldrich; Cat# WBKLS0500) and visualized using the VersaDoc imaging system. The ImageJ software was utilized to scan each immunoblot band density, and the associated sample's target protein/beta-actin signal ratios generated by the bands were compared and computed and finally plotted as a densitometric histogram. In most cases, a single band at the anticipated molecular weight validated the antibody's specificity.

2.9. Sample preparation and analysis for LC-MS/MS

We used LC-MS/MS to measure nicotine and cotinine levels in the culture media of astrocytes and neurons during nicotine metabolism studies. Neurons and astrocytes were seeded in 96 well plates and exposed to 5 % TS extract. The reaction was halted by adding 100 μl of acetonitrile at several time points (1 h, 3 h, 6 h, 24 h, and 48 h). For sample preparation, first, we diluted 20 μL of samples (collected from the exposed media) with 180 μL of LCMS water. Then, we mixed 20 μL of the resulting solution with 180 μL of 20 ng cotinine-d3 in a 1:1 water-to-acetonitrile mixture. After vortexing for 5 min, the mixture underwent centrifugation at 10,000×g rpm for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatant (150 μL) was transferred to deep well plates (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) for LC-MS/MS analysis.

Chromatographic and mass spectrometric conditions were followed from previously published methods [43]. In brief, chromatographic separation employed a Kinetex EVO C18 column (100 × 2.1 mm I.D., 1.7 μm particle size, 100 Å pore size) with a SecurityGuard™ ULTRA guard column (Phenomenex; Torrance, CA, USA). The column oven was maintained at 40 °C, and the injection volume was 4 μL. A gradient flow of a mixture comprising 5 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer (pH not adjusted) (A) and acetonitrile: methanol (3:1, v/v) (B) at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min facilitated analyte elution. The gradient program initiated with 10 % B, maintained for 0.40 min, increased to 90 % B over 0.8 min, remained constant from 0.8 to 2.2 min, reverted to the initial condition in the next 0.2 min, and re-equilibrated at 10 % B for an additional 0.6 min. The total method run time was 3.0 min, with retention times (RT) for nicotine, cotinine, and cotinine-d3 at 2.34, 2.08, and 2.19 min, respectively. Quantitation was carried out using a SCIEX 5500 QTRAP system attached to the Shimadzu Nexera LC-30AD UHPLC system. Multiple reactions monitoring (MRM) in positive mode monitored the transition pairs of m/z 163.2 precursor ion to m/z 132.1 for NT, m/z 177.2 precursor ion to m/z 98.0 for CN, and m/z 180.2 precursor ion to m/z 101.2 for the IS.

2.10. Total reactive oxygen species (ROS) measurement

Total ROS was determined using CM-H2DCFDA as a probe, according to the manufacturer's protocol with slight modification. In brief, the cells were seeded on a 3.5 cm glass bottom Petri dish at 1.25 × 105 cells/cm2 density. After 5 days of culture, the cells were exposed to either OGD/R or TS w/wo pretreated with MF and stained with 5 μM CM-H2DCFDA working solution in HBSS to determine the total ROS. The cultures were wrapped with aluminum foil to keep out of light and incubated for half an hour at 37 °C. Following the incubation period, the plates were washed (three times) with HBSS, which was maintained at 37 °C. After that, images were captured with a Leica Stellaris SP8 Falcon microscope (Leica Microsystems) set to 485 nm for excitation and 530 nm for emission. The images were obtained at 20X magnification. The same parameters (smart gain, intensity) were used for every culture to capture the photos. Protein concentration was used to normalize the cellular ROS probe (CM-H2DCFDA) mean intensity. After picture taking, the cell lysate was extracted using the RIPA (radioimmunoprecipitation assay) buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor. Cell lysates were then centrifuged for 10 min at 4 °C at 21,000 g. A fluorescence microplate reader (BioTek Synergy Mx microplate reader) was used to detect the fluorescence intensity of 100 μL of supernatant transferred to a black 96-well plate. The excitation and emission wavelengths were 485 nm and 530 nm, respectively. Lastly, the protein concentration was used to standardize the fluorescence intensity.

2.11. Immunobead assay

An immunobead assay was utilized to calculate the cytokines level in the plasma and brain tissue homogenate of the mice belonging to various groups. At the end of the TS exposure with or without MF treatment, plasma was collected, and mouse brain tissues were homogenized using RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors. These tissue homogenates and plasma were used for inflammatory cytokines assays with the Mouse High Sensitivity T-Cell 18-plex Discovery Assay® Array (Eve Technologies, Canada).

2.12. Statistical analysis

The means ± SD were used to express all data. Either an unpaired “t" test or one-way ANOVA (followed by ' 'Tukey's post hoc multiple comparison test) was used to compare the values between the groups (Prism, version 9.0; GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Nrf2 but not NQO1 and HO-1 expression decreased significantly after OGD/R in primary neurons and astrocytes

We exposed primary neuronal cells to OGD/R at two distinct times, 1 h (short duration) and 2 h (long duration), followed by 24-h reperfusions to investigate the impact of this type of deprivation on primary neurons. We observed that after a short duration OGD/R, there was no significant change in Nrf2 expression (Fig. 2A), however, there was a drop-in expression after a long duration OGD/R (Fig. 2D). The ARE-driven expression of phase II detoxifying and antioxidant enzymes the master regulator Nrf2 signaling regulates NQO1, so next we examined the effect of OGD/R on the expression of the enzyme NQO1. Western blot examination demonstrated that the downstream protein NQO1 also showed a decreased expression level (Fig. 2B and E) in both cases although that decrease was not statistically significant. However, HO-1 expression was found to be significantly higher at both time points (Fig. 2C &F).Similarly, we exposed primary astrocytes to OGD/R at two different time points, 2 h (short duration) and 4 h (long duration). While Nrf2 protein levels remained unchanged after 2 h (Fig. 2G), their expression was downregulated significantly after 4 h of OGD/R exposure (Fig. 2J). However, it was found that NQO1 expression was increased significantly only at the 2-h time point (Fig. 2H). Lastly, HO-1 expression was found to remain unchanged at both time points (Fig. 2I &L)

Fig. 2.

Anti-oxidative enzyme expressions in primary neurons and astrocytes after short and long duration of OGD/R. The protein levels of Nrf2, NQO1, and HO-1 were determined by Western blotting assay and quantified by densitometry after OGD/R in a time-dependent manner in (A–F) neuron and (G–L) astrocyte, mean ± S.D, n = 3; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

3.2. Nrf2, but not NQO1 and HO-1 expression decreased significantly after TS exposure in primary neurons and astrocytes

Previously reported studies showed that in vitro TS exposure promoted the activation of the Nrf2 pathway in endothelial cells and activation of Nrf2 pathways is indicative of protection from oxidative damage [40]. To understand the interrelationship between Nrf2, NQO1, and HO-1 in primary neurons and astrocytes after TS exposure, we exposed primary neurons to TS for 4 days and astrocytes for 5 days. Western blot analysis of the lysate from neuronal cells exposed to TS revealed an initial increase in Nrf2 (after 3 h and 6 h of TS exposure) expression followed by a decrease of Nrf2 (after 24 h and 48 h) (Fig. 3A). However, the NQO1 or HO-1 expression remained significantly higher compared to the control at those time points (Fig. 3B and C). Since astrocytes express Nrf2 at a higher level than neurons do, we did not see a substantial rise in Nrf2 expression after 3 or 6 h of exposure to TS. However, after 24 and 48 h, we did see a significant drop in Nrf2 expression, much like in neurons (Fig. 3D). Nevertheless, the NQO1 or HO-1 expression remained significantly higher compared to the control at later time points (Fig. 3E and F).

Fig. 3.

Anti-oxidative enzyme expressions in primary neurons and astrocytes after exposure to short- and long-term TS. The protein level of Nrf2, NQO1, and HO-1 was determined by Western blotting assay and quantified by densitometry after tobacco smoke exposure in a time-dependent manner in (A–C) neuron and (D–F) astrocyte, mean ± S.D, n = 3. Quantification of the nicotine concentration in (G) neurons and (H) astrocytes was done after TS exposure through LCMS, mean ± S.D, n = 3; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

We wanted to confirm that the change in Nrf2 expression is not due to the change in the concentration of nicotine the cells were exposed to. We performed an LCMS analysis to observe the nicotine metabolism in primary neurons and astrocytes. We simultaneously collected exposed media from cells at various times (1 h, 3 h, 6 h, 24 h, and 48 h) intervals, and we assessed the nicotine concentration in the freshly prepared media before applying it to the cells. As expected, we found no discernible variation in the nicotine content during the first 48 h (Fig. 3G and H). In addition, we detected no cotinine in the medium, suggesting the absence of nicotine-metabolizing enzymes in these cells.

3.3. Metformin activated Nrf2 and its downstream protein NQO1 in neurons and astrocytes after OGD/R and long-term TS exposure

Next, we investigated whether Nrf2 is activated and stabilized by MF exposure in astrocytes and neuronal cells as it was downregulated after long-duration OGD/R and prolonged TS exposure. MTS cytotoxicity experiments were performed on primary neurons and astrocytes to assess the impact of MF dose on cell viability. Primary neurons and astrocytes were subjected to various doses of MF over 24 h to evaluate their survival. In the MTS experiment, MF generated toxicity in primary neurons at higher doses, but at most doses, it did not significantly affect primary astrocytes (Fig. 4A and B).

Fig. 4.

MF upregulated anti-oxidative enzyme expressions. Effects of Metformin on (A) neuronal viability and (B) astrocyte viability in MTT assay mean ± S.D, n = 3–4. The protein levels of Nrf2 and NQO1 were determined by WB assay and quantified by densitometry after OGD/R and TS exposure and treatment with Metformin in (C–H) neuron and (I–N) astrocyte, mean ± S.D, n = 3; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Based on our results and previous data from the literature [44], we thus used two different metformin doses (10 μM and 20 μM). Western blot investigations revealed that long-duration OGD/R injury reduced the expression levels of Nrf2 and NQO1 in neurons (Fig. 2A and B). In both neurons and astrocytes, Nrf2 expression was lowered by prolonged TS exposure (Fig. 3A and D). MF pretreatment, however, reversed these negative alterations; that means an overall increase in Nrf2 nuclear activity, as seen by a corresponding rise in NQO1 expression levels in both cells under those circumstances (Fig. 4C, D, F, I, J, L &M). However, under all prior circumstances with MF pretreatment, the level of HO-1 expression remained unchanged compared to the nontreated cells (Fig. 4E–H, K & N).

3.4. Metformin significantly decreased proinflammatory gene expression and increased anti-inflammatory gene expression after OGD/R and long-term TS exposure in primary neuron and astrocyte

qRT-PCR was used to examine how much MF affected the gene expression of pro-inflammatory (TNF-α and IL-1β) and anti-inflammatory (IL-4, IL-10) cytokines during OGD/R or TS exposure to primary neurons and astrocytes (Fig. 5A - P). Interestingly, in these cells, MF significantly inhibited the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators while raising the mRNA levels of anti-inflammatory markers (IL-4, IL-10) after exposure to either OGD/R or TS. Since NF-κB activation is critical for regulating the expression of proinflammatory cytokines [39], we investigated if MF might stop NF-κB activation in these cells. The MF pretreatment dramatically decreased the expression of NF-κB in both cells, according to the results of the qRT-PCR investigation (Fig. 5Q -T). However, we did not see any dose-dependent reduction in NF-κB expression. Table 2 summarizes MF's pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory gene expression regulation after OGD/R and TS exposure to neurons and astrocytes.

Fig. 5.

MF decreased proinflammatory gene expression and increased anti-inflammatory gene expression in primary neurons and astrocytes. The mRNA expression of proinflammatory (TNF-α, IL-1β, NF-кB) and anti-inflammatory (IL-4, IL-10) gene expression determined by qRT-PCR both in neurons (A–H) & (Q–R) and astrocytes (I–P) & (S–T) after OGD/R and TS exposure and MF treatment, mean ± S.D, n = 3; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Table 2.

The table summarizes the mRNA expression of proinflammatory (TNF-α, IL-1β, NF-κB) and anti-inflammatory (IL-4, IL-10) gene expression determined by qRT-PCR both in neuron and astrocyte after OGD and TS exposure and MF treatment.

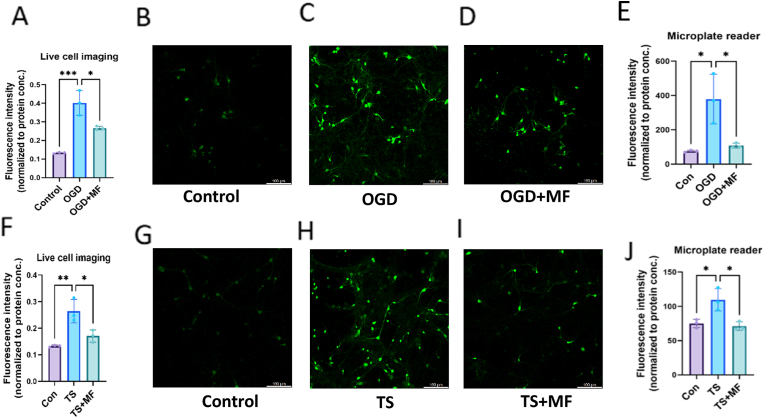

3.5. Metformin significantly decreased ROS generation in neurons after ODG/R and long-term TS exposure

Massive levels of ROS are produced by neuronal cells during ischemia and the following reperfusion, which overwhelms their removal and upsets the antioxidant equilibrium systems, which may lead to neuronal death [45]. To investigate if MF directly lowers oxidative stress in neurons, we pretreated primary cultured neurons with MF and applied MF during OGD/R. TS exposure is also responsible for the elevation of total cellular ROS [36], and ROS has a significant role in the inflammatory signaling pathway [46]. Consequently, DCFH-DA tests were used to quantify the impact of MF on OGD/R or TS-induced ROS production in primary neurons and astrocytes. This work used confocal live cell imaging and microplate reading to quantify cellular ROS in primary neurons and astrocytes using the appropriate probe, CM-H2DCFDA. OGD/R and TS-treated primary neurons showed a substantial increase in DCF-positive cells and cellular total ROS compared to the control group. Nevertheless, ROS generation was successfully decreased by MF pretreatment following OGD/R or TS exposure following the DCF fluorescence quantification assay (Fig. 6A–J).

Fig. 6.

MF decreased ROS generation in neurons after ODG/R and TS exposure. Cellular total ROS was quantified in neurons using confocal imaging (A–D) & (F–I) and plate reader (E) & (J) after OGD/R and TS, respectively, considering CM-H2DCFDA as a probe, mean ± S.D, n = 3; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

3.6. 14 days in vivo TS exposure followed by metformin treatment significantly increased Nrf2 expression and decreased NF-кB expression and other proinflammatory cytokine levels in brain tissue and plasma

To assess the impact of MF on TS-induced neuroinflammation and inflammatory cytokine in vivo, adolescent mice were exposed to TS with or without MF treatment for 14 days. A body weight assessment was performed for the animals at the beginning and end of the experiment to determine whether TS exposure or MF medication had any combined negative effects on this health indicator. After TS exposure, we noticed a significant reduction in body weight; however, no additional reduction in body weight was seen following TS in conjunction with MF treatment (Fig. 7A). After this period, animals were killed, and mRNA was taken from the cerebral cortex of mice from different experimental groups. RT-PCR was then run, specifically targeting the Nrf2 and NF-кB genes. Compared to the control group, the brains of mice exposed to TS showed a significant increase in the expression of NF-кB mRNA and a decrease in Nrf2 mRNA. However, Metformin significantly reduced the effect (Fig. 7B and C). It's interesting to note that WB analysis of Nrf2 and NF-кB in the mouse brain homogenate revealed a similar pattern: after an initial drop from TS exposure, MF treatment increased Nrf2 expression and lowered that of NF-кB (Fig. 7D and E).

Fig. 7.

In vivo TS exposure with MF treatment increased Nrf2 and decreased NF-кB expressions. (A) Effect of saline/MF therapy with/without TS exposure on body weight, n = 4 to 6 mice. The mRNA levels of Nrf2 and NF-кB were determined by qRT-PCR (B–C)) using brain tissue of different groups of mice, and the protein level of Nrf2 and NF-кB were determined by Western blotting assay and quantified by densitometry (D–E) using brain homogenate collected from mice, mean ± S.D, n = 3–4; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

In parallel, cytokines markers in the brain tissue homogenate and plasma from those animals were evaluated using an immunobead technique. TNF-α and MCP-1 were substantially more prevalent in the brain lysate of mice subjected to TS exposure than in the brains of control mice (Fig. 8A and B). Furthermore, TNF-α, MCP-1, and MIP-2 plasma levels were elevated in mice exposed to TS (Fig. 8F–H), while anti-inflammatory markers, such as IL-4 and IL-10, were significantly downregulated (Fig. 8D, E, I & J). Nevertheless, MF therapy in adolescent mice demonstrated protection against TS-induced neuroinflammation by downregulating proinflammatory cytokines and upregulating anti-inflammatory cytokines. Table 3 summarizes MF's cytokine markers regulation in the brain tissue homogenate and plasma of adolescent mice.

Fig. 8.

In vivo TS exposure with MF treatment decreased proinflammatory and increased anti-inflammatory cytokine levels. Cytokine markers were measured through immunobead assay using brain tissue (A–E) and plasma (F–J) of mice, mean ± S.D, n = 3–4; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Table 3.

The table summarizes the cytokine markers that were measured through immunobead assay using brain tissue and plasma of mice.

4. Discussion

Numerous investigations have demonstrated that exposure to TS impairs the integrity of the BBB [14,26,36,[47], [48], [49]] and causes vascular endothelial dysfunction [26,48,50,51] in a dose-dependent way [52], which eventually results in neuroinflammation and other neurological diseases including stroke. The Nrf2-ARE signaling pathway is an essential cytoprotective mechanism that enables cells to withstand oxidative stressors and preserve the proper redox balance within tissues and cells [53]. The advantages of stimulating Nrf2-ARE signaling have received a lot of attention, but the scientific literature frequently claims that Nrf2-ARE activation is a “double-edged sword." The overexpression of multidrug resistance proteins (Mrps), which have glutathione as one of their known transport substrates, may be one of them. Because glutathione (GSH) provides reducing equivalents in significant quantities (millimolar concentrations), it is regarded as the primary redox buffer in a cell [54]. To prevent protein oxidation, GSH reversibly creates mixed disulfide connections between protein thiols (S-glutathionylation) [55]. In addition to GSH, another significant endogenous antioxidant that guards against oxidative stress is thioredoxin (Trx) [56,57]. The production of GSH and the regeneration of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) in its reduced state are both facilitated by the regulation of the enzymes Trx and sulfiredoxin by Nrf2 and thus can play a critical role in the regulation of cellular redox homeostasis [58].

At the pre and post-transcriptional levels, the activation and expression of Nrf2 are strictly controlled [59,60]. Following an ischemic event, loss of Nrf2 function enlarges the cerebral infarct and causes neurological impairments [61,62]. However, the different roles of neurons and astrocytes in TS-induced neuroinflammation and diseases like ischemic stroke have been poorly studied and are still a top concern for many researchers [63]. CNS consists of several neural cells like neurons and glia; furthermore, glial cells consist of astrocytes, radial glia, oligodendroglia, and microglia [[64], [65], [66]] and diverse glial cells perform diverse tasks; astrocytes, for instance, are crucial for maintaining homeostasis and preventing illness [[67], [68], [69]]. Furthermore, astrocytes produce anti-inflammatory and antioxidant proteins, which protect the central nervous system. They also maintain the extracellular environment clean and facilitate proper neuronal communication [70]. This work aims to demonstrate the functional significance of primary neurons and astrocytes in healthy and neuropathological brain states and also to assess the protective role of Metformin in OGD/R or TS-induced neuroinflammatory conditions. Interestingly, although an initial cytoprotective increase of Nrf2 expressions was observed in our study after acute TS exposure (3 h and 6 h in neurons), the results show a progressive down-regulation of Nrf2 in both cells following long-term TS exposure (Fig. 3). A significant downregulation of Nrf2 expression was also observed in both cell line after long duration OGD/R (Fig. 2). Notably, neurons and astrocytes only showed an analogous biphasic pattern of rise and subsequently decrease or no change in NQO1 expression after prolonged OGD/R but not after long-term TS exposure. This suggests that OGD/R has more detrimental consequences than TS exposure. However, after the initial rise in expression, neither case demonstrated a noticeable decrease in HO-1 expression in neurons (Fig. 2). The primary function of HO-1, a member of the vitagene family, is to facilitate the adaptive response to cellular oxidative and nitrosative stress, which is brought on by elevated levels of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNS) respectively [71,72]. According to these findings, HO-1 continued to temporarily shelter these cells as a component of the cell's defense mechanism, even though the stressors (OGD/R and TS) harmed them. These results are consistent with our earlier in vivo research, which showed that even after a prolonged (4-week) TS exposure, an elevated level of HO-1 expression was seen [33]. This provides evidence that endogenous proteins can be altered in conditions like stroke and other neurodegenerative illnesses that are marked by both nitrosative and oxidative stress.

A previous study from our group showed that MF stabilized and translocated Nrf2 to the nucleus in response to stimuli [40] where, the binding between Nrf2 and the genes of ARE and antioxidant enzymes, such as NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), HO-1 and other antioxidant proteins involved in detoxification takes place [59,60]. Studies on the effects of MF on the Nrf2/NQO1/HO-1 axis have only been conducted in endothelial cells, hence these findings in neural cells are rather new. Based on the prior data from the literature [44] and findings from our investigation of the safety dose profiling in neurons and astrocytes (Fig. 4A and B), we used two different doses (10 μM and 20 μM) of MF, similar to the plasma level observed in individuals [73]. We were not surprised to find that pretreatment with MF upregulates Nrf2 and its downstream protein NQO1 in primary neurons after OGD/R and long-term TS exposure (Fig. 4C and D). Pretreatment with MF also restored Nrf2 expression following OGD/R in primary astrocytes (Fig. 4F). HO-1 expression remained unchanged in both cell lines following MF pretreatment (Fig. 4E–H, K & N). We believe that the antioxidant effectiveness of MF is due to the translocation of Nrf2 into the nucleus and the increased enzymatic activity of NQO1 and HO-1 and their effects on free radicals. It is also interesting to note that, when comparing 10 μM and 20 μM, we did not find any discernible dose-dependent differences in the drug's effect.

Additionally, MF has been shown to pass the ischemic BBB by a saturable transport mechanism (organic cationic transporter), as we demonstrated in recent work using an in vitro model. According to our findings, we determined that MF partially utilizes BBB Oct1 to gain brain access under OGD conditions. This occurs through a specific transport mechanism, despite increased paracellular leakage, suggesting that Oct1 is crucial for MF transport. Our results further indicated that increased Oct1 mRNA and protein levels enhance MF transport in the OGD condition [74]. Moreover, our ongoing research indicates that MF can enter the ischemic brain within 5 min after IV administration, even at a dose of 30 mg/kg, which accounts for its neuroprotective effects on the CNS. However, the critical time frame for administration and the appropriate dose to reach and maintain steady-state brain conditions requires further investigation [75].

Significant discoveries in recent years raised questions on the conventional understanding of how the brain's reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated and managed in the nervous system [76]. We assessed total ROS in primary neurons and astrocytes following exposure to long-duration OGD/R and long-term TS using live cell imaging. Since neurons are less able to sustain even moderate amounts of OS compared to astrocytes, we found considerably higher levels of total ROS formation in both TS and OGD/R exposures compared to control in primary neuronal cells (Fig. 6), but not in astrocytes. Although research has shown that astrocytes produce ROS at a higher rate than neurons due to a distinct assembly of mitochondrial respiratory supercomplexes in astrocytes, however, astrocytes have an antioxidant apparatus that is thought to be more effective than neurons at regulating redox signaling, which closely controls ROS levels. This regulation of ROS levels allows for both astrocytic and neuronal metabolic processes to be precisely calibrated [76]. A further explanation could be that Nrf2 expression in astrocytes is comparatively higher than in neurons [77], which protects astrocytes from the harmful effects of ROS. Neuroscientists studying stroke have dubbed this neuroprotective effect of a subtoxic increase in cellular oxidative stress “preconditioning" [78], but it comes within the general category of hormesis [79]. There is limited understanding of the precise molecular processes via which mitochondrial ROS cause hormetic responses in neurons; nevertheless, new research indicates that some transcriptional regulators may play significant roles [80]. The generation of excessive ROS and oxidative damage are associated with the activation of NF-κB, and many chemokines and cytokines are also closely linked to inflammation [81]. The relationship between these inflammatory mediators within the CNS may explain the development of certain neurodegenerative illnesses [63]. In line with our studies, we also saw a considerable increase in the expression of other pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, and, predictably, NF-кB, in primary neurons and astrocytes subjected to OGD/R and TS. In most conditions, MF considerably lowered the expressions of these pro-inflammatory cytokines. To maintain immunological homeostasis, proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines have a complex connection that is tightly regulated. However, after being exposed to OGD/R or TS, we found that several anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-4 and IL-10, were downregulated remarkably; nevertheless, these cytokines were restored by MF pretreatment both in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 5, Fig. 8).

In addition to reducing blood sugar levels, Metformin is known to prevent weight gain [82]. Moreover, it has been shown that TS can reduce hunger, which lowers body weight [83]. Additionally, CO (Carbon Monoxide), formed during cigarette burning, can alter neuronal activity, especially based on how severe the exposure was [84]. Our findings show that two weeks of TS exposure decreased the body weights of adolescent mice significantly (Fig. 7A). However, our study did not find any additional reduction of body weight from TS exposure combined with MF intake, which suggests that MF per se had no significant impact on the animals’ body weight. We speculate that the age of the mice may contribute to general body weight reduction, as our study uses adolescent mice, which might be more susceptible than adult mice to TS exposure. Regarding how MF administration guards against TS-induced cerebrovascular damage, brain homogenates of mice treated with MF showed higher levels of Nrf2 observed both in the RNA and protein, compared to mice exposed to TS without treatment (Fig. 7B and C). It is important to highlight that Nrf2 and NF-кB work together to coordinate inflammatory and anti-oxidative responses, determining innate immune cells' fate [62]. Furthermore, the research suggested that NF-кB inhibited Nrf2, which acts as a regulator through a feedback mechanism [63]. Comparably, MF pretreatment also inhibited the TS-induced elevation of NF-ĸB at the RNA and protein levels (Fig. 7D and E).

Furthermore, to help recruit and attach immune cells at the site of inflammation, NF-ĸB stimulates or transcriptionally regulates the expression of chemokines such as MCP-1, MIP-1, and other proinflammatory cytokines [60,61]. Moreover, one of the most extensively researched functions of NF-ĸB in aging and many diseases is its transcriptional control over the expression of cytokines like TNFα and IL-1α/β. In line with our findings, we also noticed a higher level of TNF-α in brain homogenate and plasma (Fig. 8A and F), MCP-1 in brain lysate (Fig. 8B), MIP-2 in plasma (Fig. 8H) of the TS exposed mice compared to the control mice. However, MF therapy mitigates those problems.

In conclusion, this work provides evidence that neurons and astrocytes are indeed negatively impacted by TS thus reflecting the overall worsening effect of smoking on ischemic stroke. Adolescent mice were used as a model to demonstrate the detrimental consequences of tobacco exposure since it is dangerous for young people to consume tobacco products in any form, as it can both increase stroke risk and worsen outcomes. This finding is important because it shows that MF pretreatment can suppress the pro-inflammatory gene expression and enhance the anti-inflammatory gene expression. This is partially due to the overexpression of anti-oxidases linked to Nrf2-ARE, such as HO-1 and NQO1, and also suppression of NF-кB expression in neurons, astrocytes, and adolescent mice. In light of this, MF shows promise to help TS-induced neuroinflammatory diseases, including stroke, because of its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. A schematic representation of the suggested mechanism by which MF protects the brain against OGD/R or TS-induced neuroinflammation has been summarized in Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Diagrammatic representation of the suggested mechanism by which MF protects the brain against neuroinflammation. The mechanism entails activation of the Nrf2-ARE pathway, stimulation of antioxidant enzyme expression, inactivation of NF-кB, and suppression of ROS generation induced by OGD/R or TS exposure.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH grants R01NS117906 to TJA and LC. Immunofluorescence experiments were made possible by the Core Facility Support Award (#RP200572) from the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas to the Imaging Core, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center at Amarillo.

Declarations ethics approval

Ethics approval and consent to participate in all animal studies were approved by the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Khondker Ayesha Akter: Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Sejal Sharma: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Ali Ehsan Sifat: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Yong Zhang: Writing – review & editing. Dhaval Kumar Patel: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Luca Cucullo: Writing – review & editing. Thomas J. Abbruscato: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Zijuan Liu for providing support for confocal imaging.

Contributor Information

Khondker Ayesha Akter, Email: kh.ayesha.akter@ttuhsc.edu.

Sejal Sharma, Email: sesharma@ttuhsc.edu.

Ali Ehsan Sifat, Email: ali.ehsan.sifat@gmail.com.

Yong Zhang, Email: yong.zhang@ttuhsc.edu.

Dhaval Kumar Patel, Email: dhavalkumar.patel@ttuhsc.edu.

Luca Cucullo, Email: lcucullo@oakland.edu.

Thomas J. Abbruscato, Email: thomas.abbruscato@ttuhsc.edu.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- ARE

antioxidant response elements

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CNS

central nervous system

- DCFDA

2′,7′-dichlorodihydroflurescein diacetate

- HO-1

heme oxygenase-1

- HRP

horse radish peroxidase

- IL

interleukin

- MCP-1

monocyte chemoattractant protein-1

- MIP-2

macrophase inflammatory protein-2

- NF-кB

nuclear factor -kappa B

- NQO1

NAD(P)H quinine oxidoreductase 1

- Nrf2

nuclear-factor (erythroid-derived 2) related factor-2

- RNS

reactive nitrogen species

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- TS

tobacco smoke

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Lehnardt S. Innate immunity and neuroinflammation in the CNS: the role of microglia in Toll-like receptor-mediated neuronal injury. Glia. 2010;58(3):253–263. doi: 10.1002/glia.20928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajan W.D., Wojtas B., Gielniewski B., Gieryng A., Zawadzka M., Kaminska B. Dissecting functional phenotypes of microglia and macrophages in the rat brain after transient cerebral ischemia. Glia. 2019;67(2):232–245. doi: 10.1002/glia.23536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Block M.L., Hong J.S. Microglia and inflammation-mediated neurodegeneration: multiple triggers with a common mechanism. Prog. Neurobiol. 2005;76(2):77–98. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang X., Michaelis E.K. Selective neuronal vulnerability to oxidative stress in the brain. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2010;2:12. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2010.00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dyson A., Bryan N.S., Fernandez B.O., Garcia-Saura M.F., Saijo F., Mongardon N., et al. An integrated approach to assessing nitroso-redox balance in systemic inflammation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011;51(6):1137–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vilhardt F., Haslund-Vinding J., Jaquet V., McBean G. Microglia antioxidant systems and redox signalling. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017;174(12):1719–1732. doi: 10.1111/bph.13426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan P.H. Role of oxidants in ischemic brain damage. Stroke. 1996;27(6):1124–1129. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.6.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mizuma A., Yenari M.A. Anti-inflammatory targets for the treatment of reperfusion injury in stroke. Front. Neurol. 2017;8:467. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diseases G.B.D., Injuries C. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1204–1222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leading Causes of Mortality and Health Loss at Regional, Subregional, and Country Levels in the Region of the Americas, 2000-2019, : ENLACE Data Portal. Pan American Health Organization; 2021. https://www.paho.org/en/enlace/leading-causes-death-and-disability#:∼:text=Regionwide/20in/202019/2C/20Ischemic/20heart/20disease/2C/20diabetes/20mellitus/2C/20and,DALYs)/20in/20the/20total/20population [Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ji R., Schwamm L.H., Pervez M.A., Singhal A.B. Ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack in young adults: risk factors, diagnostic yield, neuroimaging, and thrombolysis. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70(1):51–57. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nedeltchev K., der Maur T.A., Georgiadis D., Arnold M., Caso V., Mattle H.P., et al. Ischaemic stroke in young adults: predictors of outcome and recurrence. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2005;76(2):191–195. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.040543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization . WHO; 2016. Tobacco & Stroke.https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NMH-PND-CIC-TKS-16.1 [Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prasad S., Sajja R.K., Park J.H., Naik P., Kaisar M.A., Cucullo L. Impact of cigarette smoke extract and hyperglycemic conditions on blood-brain barrier endothelial cells. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2015;12:18. doi: 10.1186/s12987-015-0014-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Center for disease control and prevention . CDC; 2023, November 2. Youth and Tobacco Use.https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/youth_data/tobacco_use/index.htm [Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 16.Birdsey J. Tobacco product use among US middle and high school students—national Youth Tobacco Survey, 2023. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2023;72 doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7244a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Health UDo. Services H. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease …; Atlanta, GA: 2014. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: a Report of the Surgeon General. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cataldo J.K., Prochaska J.J., Glantz S.A. Cigarette smoking is a risk factor for Alzheimer's Disease: an analysis controlling for tobacco industry affiliation. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;19(2):465–480. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haire-Joshu D., Glasgow R.E., Tibbs T.L. Smoking and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(11):1887–1898. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.11.1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anstey K.J., von Sanden C., Salim A., O'Kearney R. Smoking as a risk factor for dementia and cognitive decline: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007;166(4):367–378. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sobczak A., Golka D., Szoltysek-Boldys I. The effects of tobacco smoke on plasma alpha- and gamma-tocopherol levels in passive and active cigarette smokers. Toxicol. Lett. 2004;151(3):429–437. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uttara B., Singh A.V., Zamboni P., Mahajan R.T. Oxidative stress and neurodegenerative diseases: a review of upstream and downstream antioxidant therapeutic options. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2009;7(1):65–74. doi: 10.2174/157015909787602823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arnson Y., Shoenfeld Y., Amital H. Effects of tobacco smoke on immunity, inflammation and autoimmunity. J. Autoimmun. 2010;34(3):J258–J265. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenberg G.A. Neurological diseases in relation to the blood-brain barrier. J. Cerebr. Blood Flow Metabol. 2012;32(7):1139–1151. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamaguchi Y., Nasu F., Harada A., Kunitomo M. Oxidants in the gas phase of cigarette smoke pass through the lung alveolar wall and raise systemic oxidative stress. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2007;103(3):275–282. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fp0061055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naik P., Fofaria N., Prasad S., Sajja R.K., Weksler B., Couraud P.O., et al. Oxidative and pro-inflammatory impact of regular and denicotinized cigarettes on blood brain barrier endothelial cells: is smoking reduced or nicotine-free products really safe? BMC Neurosci. 2014;15:51. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-15-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pun P.B., Lu J., Moochhala S. Involvement of ROS in BBB dysfunction. Free Radic. Res. 2009;43(4):348–364. doi: 10.1080/10715760902751902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Innamorato N.G., Rojo A.I., Garcia-Yague A.J., Yamamoto M., de Ceballos M.L., Cuadrado A. The transcription factor Nrf2 is a therapeutic target against brain inflammation. J. Immunol. 2008;181(1):680–689. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang R., Xu M., Wang Y., Xie F., Zhang G., Qin X. Nrf2-a promising therapeutic target for defensing against oxidative stress in stroke. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017;54(8):6006–6017. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-0111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmed S.M., Luo L., Namani A., Wang X.J., Tang X. Nrf2 signaling pathway: pivotal roles in inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Basis Dis. 2017;1863(2):585–597. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim S.W., Lee H.K., Shin J.H., Lee J.K. Up-down regulation of HO-1 and iNOS gene expressions by ethyl pyruvate via recruiting p300 to Nrf2 and depriving it from p65. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013;65:468–476. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brigelius-Flohe R., Flohe L. Basic principles and emerging concepts in the redox control of transcription factors. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2011;15(8):2335–2381. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ashabi G., Khalaj L., Khodagholi F., Goudarzvand M., Sarkaki A. Pre-treatment with metformin activates Nrf2 antioxidant pathways and inhibits inflammatory responses through induction of AMPK after transient global cerebral ischemia. Metab. Brain Dis. 2015;30(3):747–754. doi: 10.1007/s11011-014-9632-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Y., Tang G., Li Y., Wang Y., Chen X., Gu X., et al. Metformin attenuates blood-brain barrier disruption in mice following middle cerebral artery occlusion. J. Neuroinflammation. 2014;11:177. doi: 10.1186/s12974-014-0177-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sajja R.K., Green K.N., Cucullo L. Altered Nrf2 signaling mediates hypoglycemia-induced blood-brain barrier endothelial dysfunction in vitro. PLoS One. 2015;10(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naik P., Sajja R.K., Prasad S., Cucullo L. Effect of full flavor and denicotinized cigarettes exposure on the brain microvascular endothelium: a microarray-based gene expression study using a human immortalized BBB endothelial cell line. BMC Neurosci. 2015;16:38. doi: 10.1186/s12868-015-0173-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Islam M.R., Yang L., Lee Y.S., Hruby V.J., Karamyan V.T., Abbruscato T.J. Enkephalin-fentanyl multifunctional opioids as potential neuroprotectants for ischemic stroke treatment. Curr. Pharmaceut. Des. 2016;22(42):6459–6468. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666160720170124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ke Y. Purity, cell viability, expression of GFAP and bystin in astrocytes cultured by different procedures. J. Cell. Biochem.109. 2010:30–37. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang L., Wang H., Shah K., Karamyan V.T., Abbruscato T.J. Opioid receptor agonists reduce brain edema in stroke. Brain Res. 2011;1383:307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.01.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prasad S., Sajja R.K., Kaisar M.A., Park J.H., Villalba H., Liles T., et al. Role of Nrf2 and protective effects of Metformin against tobacco smoke-induced cerebrovascular toxicity. Redox Biol. 2017;12:58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martin-Montalvo A., Mercken E.M., Mitchell S.J., Palacios H.H., Mote P.L., Scheibye-Knudsen M., et al. Metformin improves healthspan and lifespan in mice. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:2192. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Akter K.A., Mansour M.A., Hyodo T., Senga T. FAM98A associates with DDX1-C14orf166-FAM98B in a novel complex involved in colorectal cancer progression. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2017;84:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2016.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaisar M.A., Kallem R.R., Sajja R.K., Sifat A.E., Cucullo L. A convenient UHPLC-MS/MS method for routine monitoring of plasma and brain levels of nicotine and cotinine as a tool to validate newly developed preclinical smoking model in mouse. BMC Neurosci. 2017;18(1):71. doi: 10.1186/s12868-017-0389-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kadry H., Noorani B., Bickel U., Abbruscato T.J., Cucullo L. Comparative assessment of in vitro BBB tight junction integrity following exposure to cigarette smoke and e-cigarette vapor: a quantitative evaluation of the protective effects of metformin using small-molecular-weight paracellular markers. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2021;18(1):28. doi: 10.1186/s12987-021-00261-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crack P.J., Taylor J.M., Flentjar N.J., de Haan J., Hertzog P., Iannello R.C., et al. Increased infarct size and exacerbated apoptosis in the glutathione peroxidase-1 (Gpx-1) knockout mouse brain in response to ischemia/reperfusion injury. J. Neurochem. 2001;78(6):1389–1399. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strassheim D., Asehnoune K., Park J.S., Kim J.Y., He Q., Richter D., et al. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase and Akt occupy central roles in inflammatory responses of Toll-like receptor 2-stimulated neutrophils. J. Immunol. 2004;172(9):5727–5733. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heldt N.A., Seliga A., Winfield M., Gajghate S., Reichenbach N., Yu X., et al. Electronic cigarette exposure disrupts blood-brain barrier integrity and promotes neuroinflammation. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;88:363–380. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hossain M., Sathe T., Fazio V., Mazzone P., Weksler B., Janigro D., et al. Tobacco smoke: a critical etiological factor for vascular impairment at the blood-brain barrier. Brain Res. 2009;1287:192–205. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaisar M.A., Sivandzade F., Bhalerao A., Cucullo L. Conventional and electronic cigarettes dysregulate the expression of iron transporters and detoxifying enzymes at the brain vascular endothelium: in vivo evidence of a gender-specific cellular response to chronic cigarette smoke exposure. Neurosci. Lett. 2018;682:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2018.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen H.-W., Chien M.-L., Chaung Y.-H., Lii C.-K., Wang T.-S. Extracts from cigarette smoke induce DNA damage and cell adhesion molecule expression through different pathways. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2004;150(3):233–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bernard A., Ku J.M., Vlahos R., Miller A.A. Cigarette smoke extract exacerbates hyperpermeability of cerebral endothelial cells after oxygen glucose deprivation and reoxygenation. Sci. Rep. 2019;9(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-51728-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gill J.S., Shipley M.J., Tsementzis S.A., Hornby R., Gill S.K., Hitchcock E.R., et al. Cigarette smoking: a risk factor for hemorrhagic and nonhemorrhagic stroke. Arch. Intern. Med. 1989;149(9):2053–2057. doi: 10.1001/archinte.149.9.2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kansanen E., Kuosmanen S.M., Leinonen H., Levonen A.L. The Keap1-Nrf2 pathway: mechanisms of activation and dysregulation in cancer. Redox Biol. 2013;1(1):45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aoyama K., Nakaki T. Glutathione in cellular redox homeostasis: association with the excitatory amino acid carrier 1 (EAAC1) Molecules. 2015;20(5):8742–8758. doi: 10.3390/molecules20058742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gilbert H.F. Thiol/disulfide exchange equilibria and disulfide bond stability. Methods Enzymol. 1995;251:8–28. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)51107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cunningham G.M., Roman M.G., Flores L.C., Hubbard G.B., Salmon A.B., Zhang Y., et al. The paradoxical role of thioredoxin on oxidative stress and aging. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2015;576:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2015.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Perkins A., Poole L.B., Karplus P.A. Tuning of peroxiredoxin catalysis for various physiological roles. Biochemistry. 2014;53(49):7693–7705. doi: 10.1021/bi5013222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hirotsu Y., Katsuoka F., Funayama R., Nagashima T., Nishida Y., Nakayama K., et al. Nrf2-MafG heterodimers contribute globally to antioxidant and metabolic networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(20):10228–10239. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tonelli C., Chio I.I.C., Tuveson D.A. Transcriptional regulation by Nrf2. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2018;29(17):1727–1745. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jiang S., Deng C., Lv J., Fan C., Hu W., Di S., et al. Nrf2 weaves an elaborate network of neuroprotection against stroke. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017;54(2):1440–1455. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-9707-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shah Z.A., Li R.C., Thimmulappa R.K., Kensler T.W., Yamamoto M., Biswal S., et al. Role of reactive oxygen species in modulation of Nrf2 following ischemic reperfusion injury. Neuroscience. 2007;147(1):53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.02.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shih A.Y., Li P., Murphy T.H. A small-molecule-inducible Nrf2-mediated antioxidant response provides effective prophylaxis against cerebral ischemia in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2005;25(44):10321–10335. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4014-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Valles S.L., Singh S.K., Campos-Campos J., Colmena C., Campo-Palacio I., Alvarez-Gamez K., et al. Functions of astrocytes under normal conditions and after a brain disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023;24(9) doi: 10.3390/ijms24098434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Prinz M., Jung S., Priller J. Microglia biology: one century of evolving concepts. Cell. 2019;179(2):292–311. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Borst K., Dumas A.A., Prinz M. Microglia: immune and non-immune functions. Immunity. 2021;54(10):2194–2208. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Khakh B.S., Sofroniew M.V. Diversity of astrocyte functions and phenotypes in neural circuits. Nat. Neurosci. 2015;18(7):942–952. doi: 10.1038/nn.4043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Clarke L.E., Liddelow S.A., Chakraborty C., Munch A.E., Heiman M., Barres B.A. Normal aging induces A1-like astrocyte reactivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2018;115(8):E1896–E1905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1800165115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Khakh B.S., Deneen B. The emerging nature of astrocyte diversity. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2019;42:187–207. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-070918-050443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sims S.G., Cisney R.N., Lipscomb M.M., Meares G.P. The role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in astrocytes. Glia. 2022;70(1):5–19. doi: 10.1002/glia.24082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Almeida A., Jimenez-Blasco D., Bolanos J.P. Cross-talk between energy and redox metabolism in astrocyte-neuron functional cooperation. Essays Biochem. 2023;67(1):17–26. doi: 10.1042/EBC20220075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bach F.H. Heme oxygenase-1: a therapeutic amplification funnel. Faseb. J. 2005;19(10):1216–1219. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3485cmt. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gozzelino R., Jeney V., Soares M.P. Mechanisms of cell protection by heme oxygenase-1. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2010;50:323–354. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lalau J.D., Lemaire-Hurtel A.S., Lacroix C. Establishment of a database of metformin plasma concentrations and erythrocyte levels in normal and emergency situations. Clin. Drug Invest. 2011;31(6):435–438. doi: 10.2165/11588310-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sharma S., Zhang Y., Akter K.A., Nozohouri S., Archie S.R., Patel D., et al. Permeability of metformin across an in vitro blood-brain barrier model during normoxia and oxygen-glucose deprivation conditions: role of organic cation transporters (octs) Pharmaceutics. 2023;15(5) doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15051357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.S. Sharma, Y. Zhang, D. Patel, K.A. Akter, S. Bagchi, A.E. Sifat, et al., Evaluation of systemic and brain pharmacokinetic parameters for repurposing metformin using intravenous bolus administration, J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therapeut. 390 (1) (2024).JPET-AR-2024-002152; DOI: 10.1124/jpet.124.002152. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.Vicente-Gutiérrez C., Jiménez-Blasco D., Quintana-Cabrera R. Intertwined ROS and metabolic signaling at the neuron-astrocyte interface. Neurochem. Res. 2021;46(1):23–33. doi: 10.1007/s11064-020-02965-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Boas S.M., Joyce K.L., Cowell R.M. The NRF2-dependent transcriptional regulation of antioxidant defense pathways: relevance for cell type-specific vulnerability to neurodegeneration and therapeutic intervention. Antioxidants. 2021;11(1) doi: 10.3390/antiox11010008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dirnagl U., Meisel A. Endogenous neuroprotection: mitochondria as gateways to cerebral preconditioning? Neuropharmacology. 2008;55(3):334–344. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Calabrese E.J., Bachmann K.A., Bailer A.J., Bolger P.M., Borak J., Cai L., et al. Biological stress response terminology: integrating the concepts of adaptive response and preconditioning stress within a hormetic dose-response framework. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2007;222(1):122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Calabrese V., Cornelius C., Dinkova-Kostova A.T., Calabrese E.J., Mattson M.P. Cellular stress responses, the hormesis paradigm, and vitagenes: novel targets for therapeutic intervention in neurodegenerative disorders. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2010;13(11):1763–1811. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.3074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Malkinson A.M. Role of inflammation in mouse lung tumorigenesis: a review. Exp. Lung Res. 2004;31(1):57–82. doi: 10.1080/01902140490495020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pryor R., Cabreiro F. Repurposing metformin: an old drug with new tricks in its binding pockets. Biochem. J. 2015;471(3):307–322. doi: 10.1042/BJ20150497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chiolero A., Faeh D., Paccaud F., Cornuz J. Consequences of smoking for body weight, body fat distribution, and insulin resistance. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008;87(4):801–809. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.4.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Raub J.A., Benignus V.A. Carbon monoxide and the nervous system. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2002;26(8):925–940. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.