Abstract

Objective

Doxorubicin (DOX)-induced cardiotoxicity limits the application of DOX in cancer patients. Currently, there is no effective prevention or treatment for DOX-induced cardiotoxicity. The cellular repressor of E1A-stimulated genes (CREG1) is a cardioprotective factor that plays an important role in the maintenance of cardiomyocytes differentiation and homeostasis. However, the role and mechanism of CREG1 in DOX-induced cardiotoxicity has not yet been elucidated.

Methods

In vivo, C57BL/6J mice, CREG1 transgenic and cardiac-specific CREG1 knockout mice were used to establish a DOX-induced cardiotoxicity model. H&E staining, Masson’s trichrome, WGA staining, real-time PCR, and western blotting were performed to examine fibrosis and ferroptosis in the myocardium. In vitro, neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes (NMCMs) were cultured and stimulated with DOX, CREG1-overexpressed adenovirus, and small interfering RNA was used to establish CREG1 overexpression or knockdown cardiomyocytes. Transcriptomics, real-time PCR, western blotting, and immunoprecipitation were used to examine the roles and mechanisms of CREG1 in cardiomyocytes ferroptosis.

Results

The mRNA and protein levels of CREG1 were reduced in the hearts and NMCMs after DOX treatment. CREG1 overexpression alleviated myocardial damage and inhibited DOX-induced ferroptosis in the myocardium. CREG1 deficiency in the heart aggravated DOX-induced cardiotoxicity and ferroptosis. In vitro, CREG1 overexpression inhibited cardiomyocytes ferroptosis induced by DOX, and CREG1 knockdown aggravated DOX-induced cardiotoxicity. Mechanistically, CREG1 inhibited the mRNA and protein expression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (PDK4) by regulating the F-box and WD repeat domain containing 7 (FBXW7)-forkhead box O1 (FOXO1) pathway. PDK4 deficiency reversed the effects of CREG1 knockdown on cardiomyocytes ferroptosis following DOX treatment.

Conclusion

CREG1 alleviated DOX-induced cardiotoxicity by inhibiting ferroptosis in cardiomyocytes. Our findings may help clarify the new roles of CREG1 in the development of DOX-induced cardiotoxicity.

Keywords: CREG1, Doxorubicin, Cardiotoxicity, Ferroptosis

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease and cancer are two important diseases that affect human health worldwide [[1], [2], [3]]. Doxorubicin (DOX), an anthracycline chemotherapeutic drug, is one of the most effective anticancer drugs for the treatment of various cancers including breast cancer, lymphoma, and sarcoma. However, the clinical application of DOX is limited in cancer patients because of its side effects, especially DOX-induced cardiotoxicity [4]. DOX-induced cardiotoxicity can be acute, subacute, or chronic. DOX-induced cardiotoxicity could lead to diastolic and systolic dysfunction and cardiomyopathy, eventually result in heart failure and death [5,6]. The primary mechanisms underlying DOX-induced cardiotoxicity include cardiomyocytes apoptosis, autophagy dysfunction, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction [[7], [8], [9], [10]]. Although studies on the mechanism of DOX-induced cardiotoxicity have proceeded for many years, the critical underlying mechanisms responsible for DOX-induced cardiotoxicity are still not clarified, and related strategies have failed to prove the protective effect in DOX-induced cardiotoxicity clinically.

Ferroptosis is a novel form of programmed cell death characterized by the accumulation of iron-dependent lipid peroxides [11,12]. The features of ferroptosis include mitochondrial atrophy, membrane density, reduction or disappearance of mitochondrial cristae, and rupture of outer mitochondrial membranes. Several recent studies have shown that ferroptosis plays an essential role in DOX-induced cardiotoxicity [[13], [14], [15], [16]]. The authors found that the ferroptosis inhibitor ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) significantly reduced DOX-induced mortality; however, the inhibitors of apoptosis, necrosis, and autophagy had no protective effect on the survival of mice with DOX-induced cardiotoxicity [15]. These results suggested that ferroptosis might be the main factor causing DOX-induced cardiotoxicity and could be a target for protection against DOX-induced cardiotoxicity. Therefore, identifying the key molecules that regulate cardiomyocytes ferroptosis may provide new strategies for preventing and treating DOX-induced cardiotoxicity.

The cellular repressor of E1A-stimulated gene 1 (CREG1) is widely expressed in various cells and tissues and plays an important role in maintaining tissue and cell homeostasis [[17], [18], [19], [20]]. CREG1 is highly expressed in the heart and plays a protective role against myocardial injury. CREG1 recombinant protein ameliorated myocardial fibrosis after myocardial infarction by inhibiting the phenotypic switching of cardiac fibroblasts [21]. CREG1 overexpression alleviated diabetic cardiomyopathy by promoting autophagy in cardiomyocytes [22]. CREG1 recombinant protein alleviated myocardial injury caused by ischemia-reperfusion by promoting myocardial autophagy [23]. However, whether CREG1 ameliorates DOX-induced cardiotoxicity remains unclear.

In the present study, we aimed to investigate the roles of CREG1 in the development of DOX-induced cardiotoxicity and clarify the underlying molecular mechanisms.

2. Material and methods

2.1. DOX-induced cardiotoxicity in vivo

Eight-week-old male C57BL/6J mice, Creg1 cardiac knockout mice (Creg1-CKO), Creg1 whole-body transgenic mice (Creg1-TG), and their littermate controls, including Creg1-floxed mice (Creg1fl/fl) and wild-type mice (WT) were used [22]. All mice had a C57BL/6J background and were housed in a pathogen-free animal facility with an ambient temperature of 23 °C ± 2 °C and a dark-light cycle of 12-12 h.

C57BL/6J, Creg1-CKO, and Creg1-TG mice were divided into control and DOX groups. The mice in the DOX group were intraperitoneally injected with DOX (Sigma Aldrich, D1515), at a cumulative dose of DOX was 18 mg/kg. Briefly, two doses of DOX were administered by intraperitoneal injection, 9 mg/kg on days 1 and 9 mg/kg on days 4. The mice in the control group were administered equal amounts of saline. For rescue experiments in vivo, an adeno-associated virus with cardiac-specific pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (PDK4) knockdown and its control virus (AAV-shPdk4, AAV-shcon; OBIO Technology, China, 4 × 1011 vector genomes) were administered to Creg1-CKO and Creg1fl/fl mice for 21 days by tail vein injection, followed by intraperitoneal injection of DOX. All mice were euthanized at 15 days after DOX first injection. The hearts were collected and stored at -80 °C for further experiments or fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde for histological analysis. The animal care protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee on the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the General Hospital of the Northern Theater Command.

2.2. Ultrasound assessment of cardiac function

A small animal ultrasound system was used to assess cardiac function. Briefly, mice were sedated by inhalation of 2 % isoflurane. Cardiac dimension and function were evaluated using M-mode echocardiography system (Vevo 2100, Canada). Left ventricular end-diastolic and end-systolic diameters were measured in the parasternal left ventricular long-axis view. Ejection fraction (EF%) and fractional shortening (FS%) were calculated using computer algorithms. All measurements were performed in a blinded manner.

2.3. Histological staining

The heart sections were dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, cut into 3-μm-thick sections using a microtome, and mounted on slides. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Masson’s trichrome staining were used to assess heart morphology and myocardial fibrosis. The stained sections were scanned using a fluorescent upright microscope at 1 × and 40 × magnifications (Zeiss, Axio Imager A2, Germany). The collagen volume fraction (CVF), which is the ratio of the collagen-positive blue area to the total tissue area, is usually analyzed using Masson trichrome staining. CVF was measured using Image J software. CVF (%) = collagen area/tissue total area × 100 %. Three visual fields were randomly selected from each pathological section. The average of the three fields was considered as the fibrosis ratio of the section. In addition, heart sections were stained for CREG1 (Abcam, ab191909, Britian) and prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2, Cell Signaling Technology, 12282S, Danvers, MA, USA) using an immunohistochemistry kit. The stained sections were scanned using a fluorescent upright microscope at 1 × and 40 × magnifications (Zeiss).

2.4. Wheat germ agglutinin staining (WGA)

To analyze the cross-sectional area of cardiomyocytes, heart tissues were stained with WGA (Sigma Aldrich, L4895, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, heart sections were dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, cut into 3-μm-thick sections using a microtome, and mounted on slides. Paraffin sections were subjected to antigen repair solution (Gene Tech, China) at 100 °C for 40 min and room temperature for 2 h, the sections were permeabilized with 0.2 % Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min, sealed with 5 % bovine serum albumin for 1 h. The sections were stained with WGA working solution for 30 min at 37 °C and washed with PBS. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Stained sections were scanned under an upright fluorescence microscope at 40 × magnification (Zeiss). ImageJ software was used to estimate the cross-sectional area of the cardiomyocytes.

2.5. Serum malondialdehyde (MDA) analysis

Serum MDA levels were determined with thiobarbituric acid (TBA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, China) [24].

2.6. Transmission electron microscopy

The myocardium was excised and fixed in 2 % glutaraldehyde. The samples underwent various processing steps, such as fixation, gradient alcohol dehydration, and displacement, and were scanned using a transmission electron microscope (Hitachi, HT7800/HT7700, Servicebio, China). The abnormal number of mitochondria were analyzed by morphological measurements using iTEM software and ImageJ software. The number of mitochondria was analyzed with the same magnification in a 100 μm square field.

2.7. Cell culture and transfection

Neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes (NMCMs) were isolated from 1- to 3-day-old C57BL/6J mice, as previously reported [25]. NMCMs were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 20 % fetal bovine serum (FBS). The cells were cultured at 37 °C in a 5 % CO2 incubator. NMCMs were stimulated with DOX at a final concentration of 5 μM.

To establish CREG1 knockdown cells, Creg1 small interfering RNA and its control (si-Creg1, si-control, RIBOBIO, China) were transfected into NMCMs using Lipofectamine™ RNAiMAX transfection reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) [22]. To establish CREG1-overexpressed cells, Creg1 adenovirus and its control adenovirus (adCREG1 and adcon, the adenovirus titer for adCREG1 was 5.53 × 1010 PFU/ml, and the adenovirus titer for adcon was 1.58 × 1011 PFU/ml, OBIO Technology, China) were added to NMCMs for 24 h. To examine the effect of CREG1 on cardiomyocytes ferroptosis after DOX stimulation, si-Creg1 or adCREG1 was administered to cells for 24 h and followed with DOX stimulation for an additional 24 h. Besides, CREG1-knockdown and overexpressed cells were pretreated with ferroptosis inhibitor Fer-1 (10 μM; Selleck, USA) or ferroptosis inducer erastin (10 μM; Selleck) for 24 h and followed by DOX treatment.

For rescue experiments, PDK4-overexpressed adenovirus and its control (adPDK4 and adcon; the adenovirus titer for adPDK4 was 5.53 × 1010 PFU/ml, and the adenovirus titer for adcon was 4.74 × 1010 PFU/ml, OBIO Technology) were added to CREG1-overexpressed cells, followed by DOX stimulation for an additional 24 h. Three independent experiments were conducted.

In addition, HL-1 cells were purchased from TONGPAI (SHANGHAI) BIOTECHNOLOGY CO., LTD (China) and MDA-MB-231 cells were purchased by FuHeng BioLogy (China). HL-1 cells and MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10 % FBS. To clarify the effect of CREG1 and DOX on the ferroptosis and proliferation of MDA-MB-231 cells, adCREG1, Fer-1 (10 μM) was added into the culture medium for 24 h, and followed by DOX stimulation for additional 24 h.

2.8. Plasmid construction

To establish a forkhead box O1 (FOXO1)-overexpressed plasmid, Foxo1 cDNA sequences were inserted into the pcDNA3.1-P2A-GFP plasmid, and the stop codon was replaced with a 6 × His tag (WZ Biosciences Inc., China). To establish the F-box and WD repeat domain-containing 7 (FBXW7)-overexpressed plasmid, Fbxw7 cDNA sequences were inserted into the pcDNA3.1-P2A-RFP plasmid, and the stop codon was replaced with a 3 × Flag tag (WZ Biosciences Inc.). To establish the mutated FBXW7 plasmid, Fbxw7 cDNA sequences with a deletion of 841-981bp were inserted into the pcDNA3.1-P2A-RFP plasmid and the stop codon was replaced with a 3 × Flag tag (WZ Biosciences Inc.). FOXO1 or FBXW7-overexpressed plasmids were transfected into NMCMs or HEK293T cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

2.9. Cell counting kit-8 (CCK8) assay

To examine the effect of different cell death inhibitors on cardiomyocytes viability induced by DOX, HL-1 cells were seeded in 96-well plates and pretreated with necrostatin-1 (Nec-1, necroptosis inhibitor, 30 μM, MedChemExpress, USA), Z-VAD-FMK (apoptosis inhibitor, 40 μM, MedChem Express), chloroquine (CQ, autophagy inhibitor, 10 μM, MedChemExpress) or Fer-1 (ferroptosis inhibitor, 10 μM, Selleck) for 24 h, and followed by DOX treatment for additional 24 h. Besides, MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded in 96-well plates and treated with different concentrations of DOX for 24 h. 10 μL CCK8 solution (Beyotime, China) and 90 μL serum-free medium was added to each well, and the cultures were incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured.

2.10. Immunoprecipitation (IP)

HEK293T cells were co-transfected with FOXO1-His, FBXW7-Flag, or ubiquitin-HA plasmids for 24 h. The cells were collected and lysed in IP lysis buffer for 30 min. The lysate was centrifuged at 13000 g for 15 min. The protein was incubated with Flag antibody (Sigma Aldrich, F1804), His antibody (Proteintech, China, 66005-1-lg), FOXO1 antibody (Proteintech, 18592-1-AP), FBXW7 antibody (Proteintech, 55290-1-AP), or ubiquitin-conjugated beads (MBL, Japan, D058-8) and rotated overnight at 4 °C. The beads were washed 3 times with IP lysis buffer. Western blotting was performed as previously described [21].

2.11. RNA extraction and real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted using the TRIzol method (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Total RNA was subjected to reverse transcription reactions using the Takara reverse transcription kit, followed by real-time quantitative PCR reactions using a CFX96 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad, USA). The mRNA expression levels of Creg1, Pdk4, Foxo1, and Fbxw7 in the myocardium and cardiomyocytes were measured. 18s was used as the loading control. The primers used were listed in Table S1 (Sangong Biotech). Amplification and calculations were performed as described previously [21].

2.12. Western blotting

Total proteins were isolated from hearts or cells with RIPA lysis buffer. Proteins were separated using SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes, blocked with 5 % skim milk. The membranes were incubated at 4 °C overnight with the corresponding primary antibodies and HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. The primary antibodies were as follows: CREG1 (Abcam, ab191909), PTGS2 (Cell Signaling Technology, 12282S), glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4, Proteintech, 67763-1-lg), 4-Hydroxynonenal (4-HNE, Abcam, ab46545), transferrin receptor (TFR, Proteintech, 66180-1-lg), PDK4 (Abcam, ab214938), FOXO1 (Proteintech, 18592-1-AP), FBXW7 (Proteintech, 55290-1-AP), Flag (Sigma Aldrich, F1804), His (Proteintech, 66005-1-lg), HA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-7392), S-phase kinase associated protein 2 (SKP2, Abclonal, China, A7728), STIP1 homology and U-box containing protein 1 (STUB1, Abclonal, A11751), itchy E3 ubiquitin protein ligase (ITCH, HUABIO, China, ER1901-94), homeobox A5 (HOXA5, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-515309), signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3, Cell Signaling Technology, 9139S), proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA, Abclonal, A0264). GAPDH (Cell Signaling Technology, 2118S) was used as the internal reference.

2.13. Transcriptomics

The hearts in the Creg1-TG-DOX and WT-DOX groups were collected and treated with TRIzol reagent. The samples were subjected to transcriptomic analysis (BioMiao Biological Technology Co., Ltd., China) to screen for differentially genes.

2.14. JASPAR database and luciferase assay

The JASPAR database (https://jaspar.genereg.net/) was used to screen the transcription factor binding sites of mouse Pdk4. The mouse promoter region (-2000 bp) of Pdk4 was inserted into the pGL3-basic vector (pGL3-Pdk4). The binding position between the Foxo1 and Pdk4 promoter was GTAACAA. HEK293T cells were transfected with the pcDNA3.1-FOXO1 plasmid, Renilla luciferase reporter vector (luciferase control vector), or pGL3-Pdk4 vector. At 24 h after transfection, the luciferase activity was measured using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) on a SpectraMax i3X Multimode Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices). Luciferase activity was defined as the ratio of firefly luciferase activity to Renilla luciferase activity.

2.15. Measurement of mitochondrial reactive oxygen (ROS)

NMCMs or HL-1 cardiomyocytes were transfected with adCREG1, si-Creg1, adPDK4, or corresponding controls for 24 h and stimulated with DOX for an additional 24 h. Mitochondrial ROS levels in cardiomyocytes were quantified by measuring MitoSOX Red fluorescence (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The cells were incubated with MitoSOX for 30 min at 37 °C in the dark and washed three times with PBS. Relative levels of cellular fluorescence were quantified using a confocal microscope (Zeiss). Besides, the fluorescence intensity of MitoSOX was quantified using a full-wavelength enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader (TECAN). Briefly, HL-1 cardiomyocytes were seeded in 6-well plates and were treated with adCREG1 or si-Creg1, followed by DOX stimulation. The cells were stained with MitoSOX dye (5 μM) for 20 min, digested with trypsin, and counted. Cells (5 × 106) were added to 96-well plates, and the fluorescence intensity was examined using a 510 nm excitation wavelength and a 580 nm emission wavelength.

2.16. Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential

The mitochondrial membrane potential of NMCMs was quantified using JC-1 staining (Beyotime). Briefly, NMCMs were transfected with adCREG1, si-Creg1, adPDK4, or the corresponding controls for 24 h and then stimulated with DOX for 24 h. The cells were incubated with JC-1 dye according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The fluorescence intensities of JC-1 aggregates (red) and JC-1 monomer (green) were quantified using a confocal microscope (Zeiss).

2.17. Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS v22.0 (IBM Inc., Armonk, NY, USA). Data were shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Differences between the experimental and control groups were calculated using an unpaired Student’s t-test. Differences among three or more groups were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. DOX reduced CREG1 expression in cardiomyocytes

CCK8 assay revealed that DOX induced cardiomyocytes death in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. S1A). Various inhibitors were used to determine the exact mechanism of DOX-mediated cell death. CQ (an autophagy inhibitor) and Nec-1 (a necroptosis inhibitor) did not inhibit DOX-induced cell death. However, Fer-1 (a ferroptosis inhibitor) and Z-VAD-FMK (an apoptosis inhibitor) blocked the DOX-induced decrease in cell viability, and the effect of Fer-1 was stronger than that of Z-VAD-FMK (Fig. S1B). These results indicated that ferroptosis might be the main cell death mechanism under DOX stimulation, which was consistent with previous studies [15].

Compared with the control group, the mRNA level of ferroptosis marker Ptgs2 was increased in DOX-treated cardiomyocytes (Fig. S1C). Compared to the control group, the protein levels of PTGS2, TFR, and 4-HNE were increased in the DOX group, whereas the protein level of GPX4 was reduced in the DOX group (Figs. S1D–E). In addition, the mRNA and protein levels of CREG1 were significantly reduced in the DOX-treated cardiomyocytes (Figs. S1C–E). These results revealed that DOX induced cardiomyocytes ferroptosis and reduced CREG1 expression in cardiomyocytes.

3.2. CREG1 expression was reduced in the myocardium after DOX treatment

To further investigate whether DOX induced myocardial ferroptosis in vivo, an intraperitoneal injection of DOX was used to establish DOX-induced cardiotoxicity in C57BL/6J mice. Compared with the control group, the DOX group exhibited systolic dysfunction with decreased EF% and FS% (p < 0.01; Fig. S2A). The ratio of heart weight (HW) to tibial length (TL) was decreased in the DOX group of C57BL/6J mice (Fig. S2B). The mRNA levels of atrial natriuretic peptide (Anp) and natriuretic peptide B (Bnp) were significantly higher in the DOX group than those in the control group (Fig. S2C). Furthermore, cardiac fibrosis occurred in the DOX-treated myocardium (Figs. S2D–E). WGA staining indicated that DOX caused cardiomyocytes atrophy (Figs. S2D–E). The serum MDA levels in the DOX group were higher than those in the control group (Fig. S3A). Electron microscopy revealed that the number of abnormal mitochondria in the myocardium of the DOX group was significantly higher than that in the control group (Figs. S3B–C).

Compared to the control group, Ptgs2 mRNA was increased in the myocardium of the DOX group; however, Creg1 mRNA was significantly decreased in the DOX group (Fig. S3D). Compared to the control group, the protein levels of PTGS2, TFR, and 4-HNE were increased in the myocardium of the DOX group, whereas the protein levels of CREG1 and GPX4 were reduced in the myocardium of the DOX group (Figs. S3E–F). Immunohistochemical staining indicated that PTGS2 expression was increased and CREG1 expression was inhibited in the myocardium of the DOX group (Fig. S3G). These results indicated that DOX caused myocardial ferroptosis and reduced CREG1 expression in vivo.

3.3. CREG1 deficiency exacerbated cardiac dysfunction induced by DOX

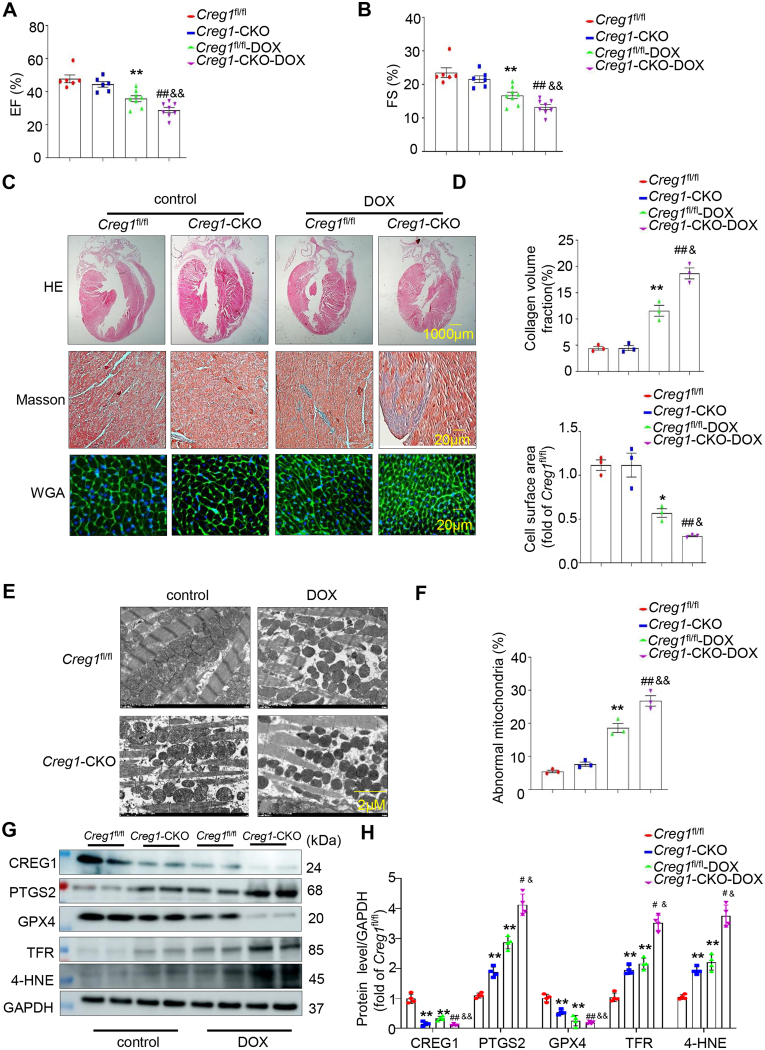

To clarify the role of CREG1 in DOX-induced cardiotoxicity, Creg1-CKO mice and Creg1fl/fl mice were used. Compared to the control group, the DOX groups of Creg1-CKO and Creg1fl/fl mice showed decreased EF% and FS%. Interestingly, the EF% and FS% in the DOX group of Creg1-CKO mice were significantly lower than those in the DOX group of Creg1fl/fl mice (p < 0.01; Fig. 1A-B). The HW/TL ratio was significantly lower in the DOX group of Creg1fl/fl mice than in the control group of Creg1fl/fl mice. The HW/TL ratio in the DOX group of Creg1-CKO mice was lower than that in the DOX group of Creg1fl/fl mice (p < 0.05; Fig. S4A). Compared to control group, body weight in the DOX group of Creg1-CKO mice and Creg1fl/fl mice was significantly decreased. However, no obvious difference of body weight existed between the DOX group of Creg1-CKO mice and the DOX group of Creg1fl/fl mice (Fig. S4A).

Fig. 1.

CREG1 deficiency aggravated DOX-induced cardiotoxicity by increasing myocardial ferroptosis

A-B. EF% and FS% in the Creg1-CKO mice and Creg1fl/fl mice after DOX treatment (n = 6 for the control group, n = 8 for the DOX group). C-D. HE staining, Masson’s trichrome staining, and WGA staining in the Creg1-CKO mice and Creg1fl/fl mice after DOX treatment (n = 3). E-F. Transmission electron microscope for mitochondria in the myocardium of Creg1-CKO mice and Creg1fl/fl mice after DOX treatment (n = 3). G-H. Western blotting of CREG1 and ferroptosis-related proteins in the Creg1-CKO mice and Creg1fl/fl mice after DOX treatment (n = 4). DOX: doxorubicin, Creg1-CKO: Creg1 cardiac-specific knockout mice; Creg1fl/fl mice: littermate control mice. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs. Creg1fl/fl mice. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 vs. Creg1-CKO mice; &p < 0.05, &&p < 0.01 vs. Creg1fl/fl-DOX mice.

Compared with the control group of Creg1fl/fl mice, cardiac fibrosis occurred in the DOX group of Creg1-CKO and Creg1fl/fl mice. Cardiac fibrosis in the DOX group of Creg1-CKO mice was more severe than that in the DOX group of Creg1fl/fl mice (p < 0.05, Fig. 1C-D). Meanwhile, the effects of CREG1 knockout on the surface area of cardiomyocytes under DOX stimulation were evaluated using WGA staining. DOX reduced the cell surface area of cardiomyocytes in Creg1-CKO and Creg1fl/fl mice, which was more pronounced in Creg1-CKO mice (p < 0.05, Fig. 1C-D). Furthermore, the mRNA levels of Anp and Bnp in the DOX group of Creg1-CKO mice were higher than those in the DOX group of Creg1fl/fl mice (p < 0.05; Fig. S4B).

3.4. CREG1 deficiency exacerbated myocardial ferroptosis induced by DOX

Electron microscopy revealed abnormal mitochondria existed in the DOX group of Creg1-CKO and Creg1fl/fl mice compared to the corresponding control group, and the number of abnormal mitochondria in the DOX group of Creg1-CKO mice was higher than that in the DOX group of Creg1fl/fl mice (Fig. 1E-F). The protein expression of PTGS2, TFR, and 4-HNE in Creg1-CKO mice was higher than that in Creg1fl/fl mice, whereas GPX4 protein expression was lower in Creg1-CKO mice (p < 0.01, Fig. 1G- H). Compared to the corresponding control group, GPX4 protein expression was decreased in the DOX group of Creg1-CKO and Creg1fl/fl mice, the protein levels of PTGS2, TFR, and 4-HNE were increased in the DOX group of Creg1-CKO and Creg1fl/fl mice (p < 0.01, Fig. 1G-H). Interestingly, compared to the DOX group of Creg1fl/fl mice, the protein levels of PTGS2, TFR, and 4-HNE were significantly increased, whereas the expression of GPX4 was significantly decreased in the DOX group of Creg1-CKO mice (p < 0.05, Fig. 1G-H). In addition, serum MDA level in the DOX group of Creg1-CKO mice was higher than that in the DOX group of Creg1fl/fl mice (p < 0.01, Fig. S4C).

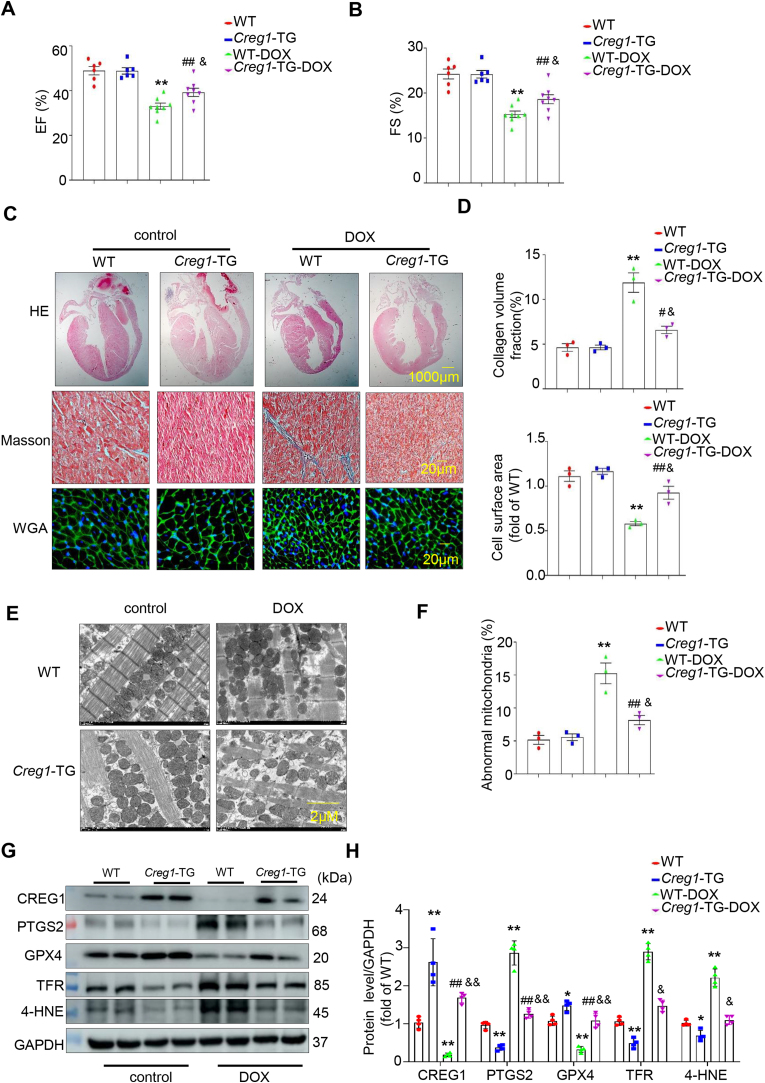

3.5. CREG1 overexpression improved cardiac function induced by DOX

To further clarify the role of CREG1 overexpression in DOX-induced cardiotoxicity, we used Creg1-TG and WT mice. The EF% and FS% was decreased in the DOX group of Creg1-TG and WT mice compared to those in the corresponding control group. Interestingly, the EF% and FS% in the DOX group of Creg1-TG mice was improved compared to those in the DOX group of WT mice (p < 0.05, Fig. 2A-B). The HW/TL ratio in the DOX group of Creg1-TG mice was higher than that in the DOX group of WT mice (p < 0.05, Fig. S4D). Compared to control group, body weight in the DOX group of Creg1-TG mice and WT mice was significantly decreased. However, there was no obvious difference of body weight between the DOX group of Creg1-TG mice and the DOX group of WT mice (Fig.S4D).

Fig. 2.

CREG1 overexpression alleviated DOX-induced cardiotoxicity by inhibiting the myocardial ferroptosis

A-B. EF% and FS% in the Creg1-TG mice and WT mice after DOX treatment (n = 6 for the control group, n = 8 for the DOX group). C-D. HE staining, Masson’s trichrome staining, and WGA staining in the Creg1-TG mice and WT mice after DOX treatment (n = 3). E-F. Transmission electron microscope for mitochondria in the myocardium of Creg1-TG mice and WT mice after DOX treatment (n = 3). G-H. Western blotting of CREG1 and ferroptosis-related proteins in the Creg1-TG mice and WT mice after DOX treatment (n = 4). DOX: doxorubicin, Creg1-TG: Creg1 transgenic mice; WT mice: wild type mice. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs. WT mice; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 vs. Creg1-TG mice; &p < 0.05, &&p < 0.01 vs. WT-DOX mice.

Cardiac fibrosis was observed in the DOX group of Creg1-TG and WT mice (p < 0.01, Fig. 2C-D), and cardiac fibrosis was alleviated in the DOX group of Creg1-TG mice compared to that in the DOX group of WT mice (p < 0.05, Fig. 2C-D). Additionally, DOX reduced the cell surface area of cardiomyocytes in Creg1-TG and WT mice. Compared to the DOX group of WT mice, the cell surface area of cardiomyocytes in the DOX group of Creg1-TG mice were increased (p < 0.05, Fig. 2C-D). In addition, the mRNA levels of Anp and Bnp in the DOX group of Creg1-TG mice were significantly lower than those in the DOX group of WT mice (p < 0.05, Fig. S4E).

3.6. CREG1 overexpression alleviated myocardial ferroptosis induced by DOX

Electron microscopy revealed that the number of abnormal mitochondria was reduced in the DOX group of Creg1-TG mice compared to the DOX group of WT mice (p < 0.05, Fig. 2E-F). The protein expression of PTGS2, TFR, and 4-HNE in Creg1-TG mice were lower than those in WT mice, whereas GPX4 protein expression was increased in Creg1-TG mice (p < 0.05, Fig. 2G-H). Interestingly, compared with the DOX group of WT mice, the protein levels of PTGS2, TFR, and 4-HNE were significantly reduced, whereas the expression of GPX4 was significantly increased in the DOX group of Creg1-TG mice (p < 0.05, Fig. 2G-H). In addition, serum MDA level in the DOX group of Creg1-TG mice was lower than that in the DOX group of WT mice (p < 0.05, Fig. S4F).

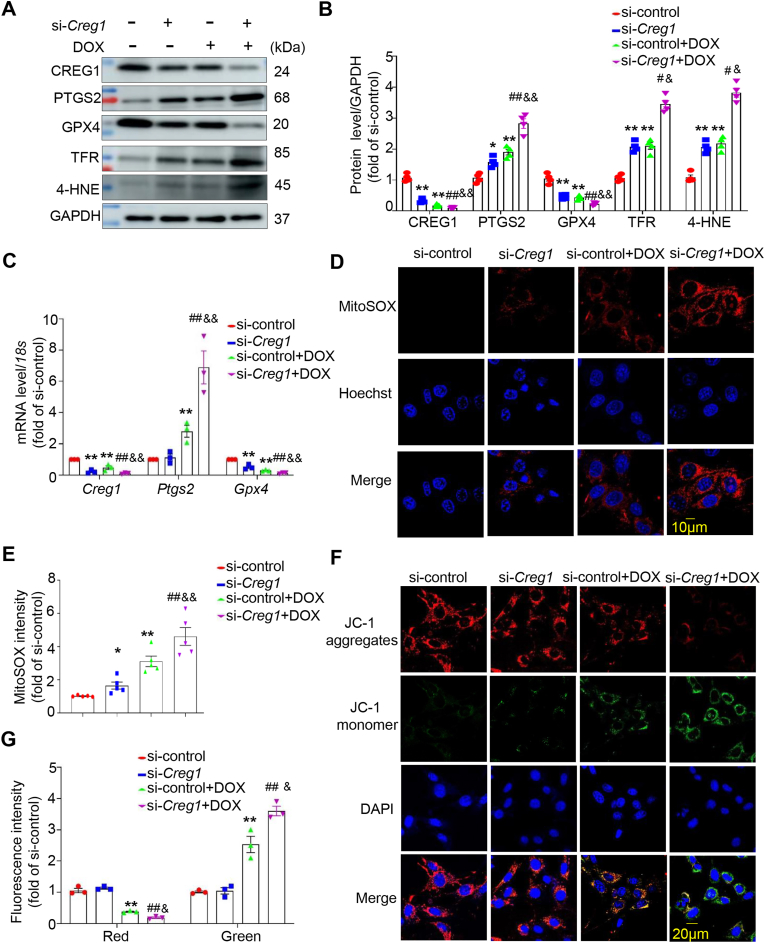

3.7. CREG1 knockdown exacerbated cardiomyocytes ferroptosis induced by DOX in vitro

To determine whether CREG1 knockdown enhanced DOX-induced cardiomyocytes ferroptosis, NMCMs were transfected with si-Creg1 and stimulated with DOX. Compared with the si-control group, an increase in the expression of PTGS2, TFR, and 4-HNE and a decrease in the expression of GPX4 were observed in the si-Creg1 group (p < 0.05, Fig. 3A-B). DOX increased the expression of PTGS2, TFR, and 4-HNE and decreased the expression of GPX4 (p < 0.01, Fig. 3A-B). Interestingly, the expression levels of PTGS2, TFR, and 4-HNE were increased, whereas GPX4 expression was decreased in the si-Creg1+DOX group compared to those in the si-control+DOX group (p < 0.05, Fig. 3A–C).

Fig. 3.

CREG1 knockdown aggravated the cardiomyocytes ferroptosis induced by DOX

A-B. Effects of CREG1 knockdown on the expressions of ferroptosis-related proteins in NMCMs with DOX treatment (n = 3). C. The mRNA of Creg1, Ptgs2 and Gpx4 in CREG1-knockdown NMCMs with DOX treatment (n = 3). D-E. Effects of CREG1 knockdown on mitochondrial oxidation in NMCMs using MitoSOX staining (n = 5). F-G. Effects of CREG1 knockdown on mitochondrial membrane potential in NMCMs using JC-1 staining (n = 3). DOX: doxorubicin, NMCMs: neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs. si-control group; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 vs. si-Creg1 group; &p < 0.05, &&p < 0.01 vs. si-control+DOX group.

Since ferroptosis is driven by lipid membrane damage, we investigated the mitochondrial ROS and membrane potential. Normal NMCMs exhibited low mitochondrial ROS levels. Compared to the si-control group, the content of mitochondrial ROS was increased in the si-Creg1 group (p < 0.05, Fig. 3D–E, Fig. S5A). After DOX stimulation, mitochondrial ROS content significantly increased (p < 0.01, Fig. 3D–E, Fig. S5A). Furthermore, the mitochondrial ROS content in the si-Creg1+DOX group was higher than that in the si-control+DOX group (p < 0.01, Fig. 3D–E, Fig. S5A). In addition, the fluorescence intensity of JC-1 aggregates was reduced, whereas the fluorescence intensity of the JC-1 monomer was increased in DOX-treated NMCMs (p < 0.01, Fig. 3F-G), indicating that DOX decreased the mitochondrial membrane potential in cardiomyocytes. The mitochondrial membrane potential was significantly reduced in the si-Creg1+DOX group compared to that in the si-control+DOX group (p < 0.05, Fig. 3F-G).

Fer-1 (a ferroptosis inhibitor) was added to CREG1 knockdown-NMCMs and followed by DOX treatment. Following DOX stimulation, Fer-1 inhibited the expression of PTGS2, TFR, and 4-HNE and increased the expression of GPX4 in CREG1-knockdown cardiomyocytes (p < 0.05, Figs. S5B–C). Meanwhile, under DOX stimulation, the mitochondrial ROS content was reduced in the si-Creg1+Fer-1 group compared to that in the si-Creg1 group (p < 0.01, Figs. S5D–E).

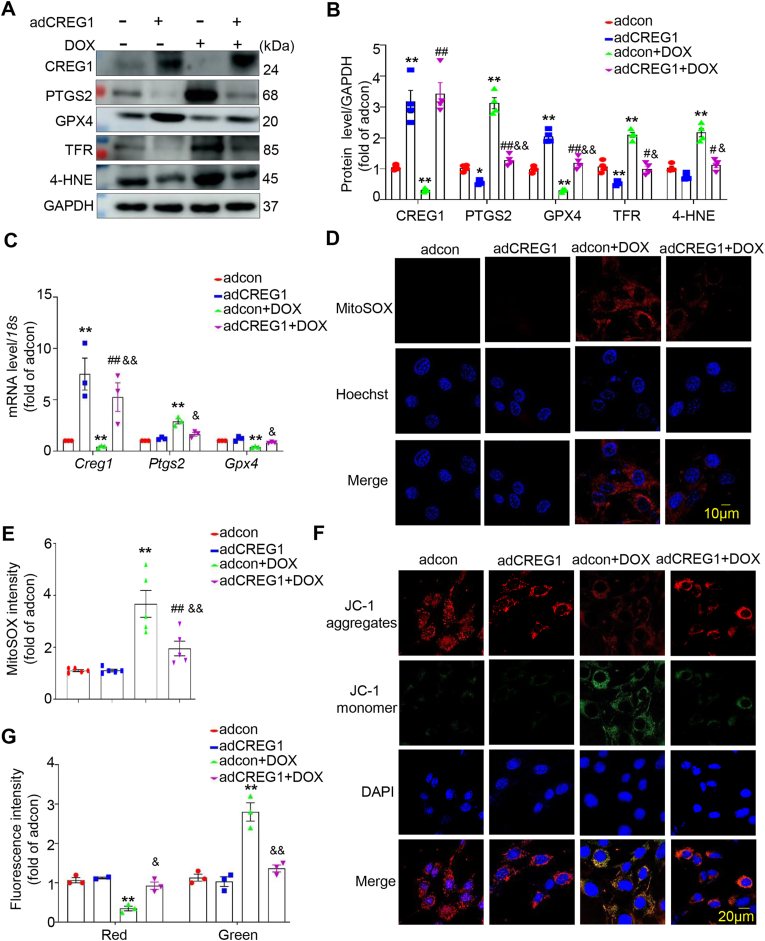

3.8. CREG1 overexpression inhibited cardiomyocytes ferroptosis induced by DOX in vitro

To further determine whether CREG1 overexpression inhibited DOX-induced cardiomyocytes ferroptosis, we infected NMCMs with adCREG1 and stimulated them with DOX. Compared to the adcon group, the expression of PTGS2, TFR, and 4-HNE was decreased, whereas that of GPX4 was increased in the adCREG1 group (p < 0.05, Fig. 4A-B). Moreover, CREG1 overexpression inhibited the expression of PTGS2, TFR, and 4-HNE, but increased the expression of GPX4 in response to DOX stimulation (p < 0.05, Fig. 4A–C).

Fig. 4.

CREG1 overexpression inhibited the cardiomyocytes ferroptosis induced by DOX

A-B. Effects of CREG1 overexpression on the expressions of ferroptosis-related proteins in NMCMs with DOX treatment (n = 4). C. The mRNA of Creg1, Ptgs2 and Gpx4 in CREG1-overexpressed NMCMs with DOX treatment (n = 3). D-E. Effects of CREG1 overexpression on mitochondrial oxidation in NMCMs using MitoSOX staining (n = 5). F-G. Effects of CREG1 overexpression on mitochondrial membrane potential in NMCMs using JC-1 staining (n = 3). DOX: doxorubicin, NMCMs: neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs. adcon group; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 vs. adCREG1 group; &p < 0.05, &&p < 0.01 vs. adcon+DOX group.

Compared to the adcon+DOX group, the mitochondrial ROS content was reduced in the adCREG1+DOX group (p < 0.01, Fig. 4D–E, Fig. S6A). Furthermore, compared to the adcon+DOX group, the fluorescence intensity of JC-1 aggregates was increased, whereas the fluorescence intensity of JC-1 monomers was reduced in the adCREG1+DOX group (p < 0.05, Fig. 4F-G), indicating that CREG1 overexpression increased the mitochondrial membrane potential in cardiomyocytes.

Erastin (a ferroptosis inducer) was added to CREG1-overexpressed NMCMs and followed by DOX treatment. Upon DOX stimulation, erastin increased the expression of PTGS2, TFR, and 4-HNE and inhibited the expression of GPX4 in CREG1-overexpressed cardiomyocytes (p < 0.05, Figs. S6B–C). In addition, under DOX stimulation, the mitochondrial ROS content was higher in the adCREG1+erastin group than in the adCREG1 group (p < 0.01, Figs. S6D–E).

3.9. CREG1 overexpression inhibited the proliferation of breast cancer cell

DOX is reported to inhibit the proliferation of breast cancer cell [26]. Whether CREG1 overexpression affected the anti-proliferative effect of DOX in breast cancer remained unclear. Different doses of DOX were used to stimulate breast cancer cell MDA-MB-231, and a CCK8 assay was used to examine cell proliferation. DOX inhibited the proliferation of MDA-MB-231 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. S7A). DOX increased the protein levels of CREG1 and PTGS2, and inhibited the expressions of GPX4 and PCNA in MDA-MB-231 cells (Figs. S7B–C). Interestingly, CREG1 overexpression and DOX promoted the ferroptosis and inhibited the proliferation of MDA-MB-231 cells (Figs. S7D–F). To clarify whether CREG1 or DOX inhibited the proliferation of MDA-MB-231 cells by increasing the ferroptosis, Fer-1 was added in adCREG1 or DOX-treated cells. Fer-1 significantly increased the PCNA expression and reversed the effects of CREG1 overexpression and DOX on the ferroptosis and proliferation of MDA-MB-231 cells (Figs. S7G–H).

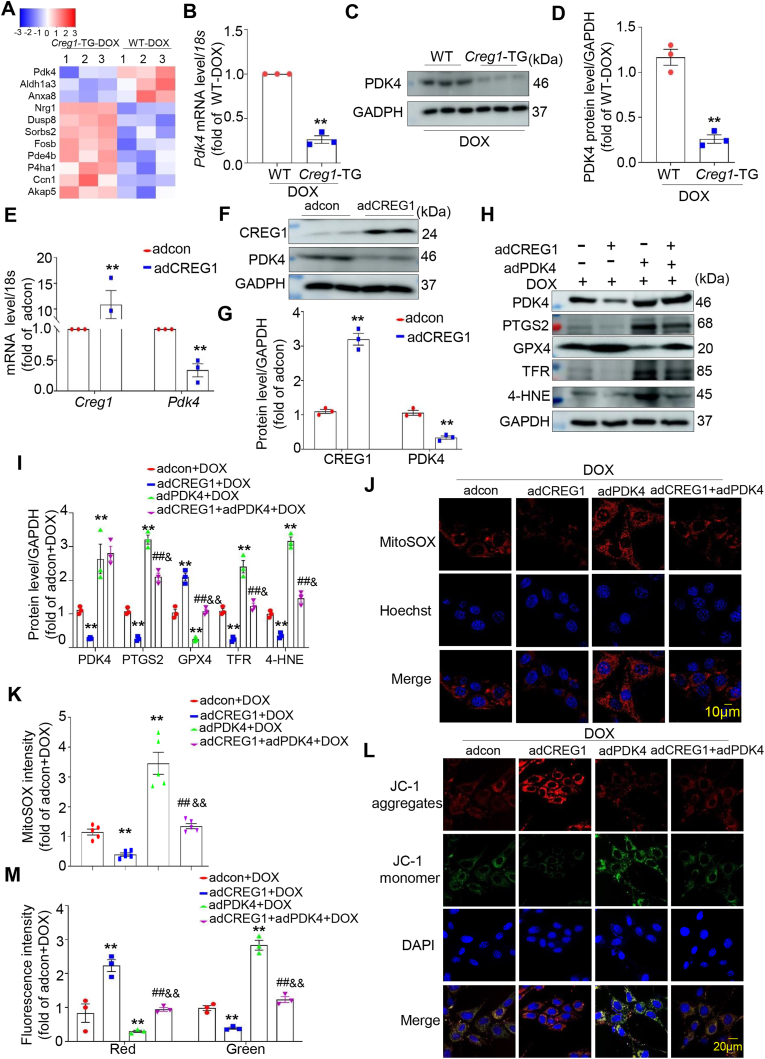

3.10. CREG1 overexpression inhibited the mRNA and protein expression of PDK4 in cardiomyocytes

To reveal the mechanism of CREG1 in cardiomyocytes ferroptosis, the hearts in the group of Creg1-TG-DOX and WT-DOX were subjected to transcriptomic analyses. We found that the mRNA and protein levels of PDK4 were reduced in the hearts of Creg1-TG-DOX group compared to those in the hearts of WT-DOX group (Fig. 5A–D), indicating that PDK4 might be a downstream of CREG1. To further examine the relationship between CREG1 and PDK4, CREG1 or PDK4-overexpressed adenovirus or siRNA was administered to NMCMs. CREG1 overexpression inhibited the mRNA and protein levels of PDK4 in NMCMs (Fig. 5E–G), whereas CREG1 knockdown increased the mRNA and protein levels of PDK4 in NMCMs (Figs. S8A–C). However, PDK4 overexpression or knockdown did not affect the mRNA and protein expression of CREG1 in NMCMs (Figs. S8D–I).

Fig. 5.

CREG1 overexpression attenuated cardiomyocytes ferroptosis by inhibiting PDK4 expression

A. Heatmap of differential genes in the myocardium of Creg1-TG-DOX and WT-DOX mice. B-D. Real-time PCR and western blotting of PDK4 in the myocardium of Creg1-TG-DOX and WT-DOX mice (n = 3). E-G. Real-time PCR and western blotting of PDK4 expression in CREG1-overexpressed NMCMs (n = 3). H–I. Effects of CREG1 overexpression and PDK4 overexpression on the expression of ferroptosis-related proteins in NMCMs, as determined by western blotting (n = 3). J-K. Effects of PDK4 overexpression on mitochondrial oxidation in the CREG1-overexpressed NMCMs using by MitoSOX staining (n = 5). L-M. Effects of CREG1 overexpression and PDK4 overexpression on mitochondrial membrane potential in NMCMs using JC-1 staining (n = 3). DOX: doxorubicin, NMCMs: neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes. **p < 0.01 vs. adcon group or WT-DOX group or adcon+DOX group; ##p < 0.01 vs. adCREG1+DOX group; &p < 0.05, &&p < 0.01 vs. adPDK4+DOX group.

3.11. CREG1 overexpression attenuated cardiomyocytes ferroptosis by inhibiting PDK4 expression

To assess the role of PDK4 in mediating the effects of CREG1 on cardiomyocytes ferroptosis, the effects of PDK4 on cardiomyocytes ferroptosis were firstly examined. The results indicated that PDK4 overexpression increased the expression of PTGS2, TFR, and 4-HNE and inhibited the expression of GPX4 in cardiomyocytes with or without DOX treatment (Figs. S8J–K). Moreover, PDK4 knockdown inhibited cardiomyocytes ferroptosis, with or without DOX treatment (Figs. S8L–M).

Interestingly, the expression of PTGS2, TFR, and 4-HNE was significantly inhibited, whereas the expression of GPX4 was increased in the adCREG1+adPDK4+DOX group compared to the adPDK4+DOX group (p < 0.05, Fig. 5H-I). In addition, CREG1 overexpression inhibited mitochondrial ROS production and increased mitochondrial membrane potential in PDK4-overexpressed NMCMs (p < 0.01, Fig. 5J–M).

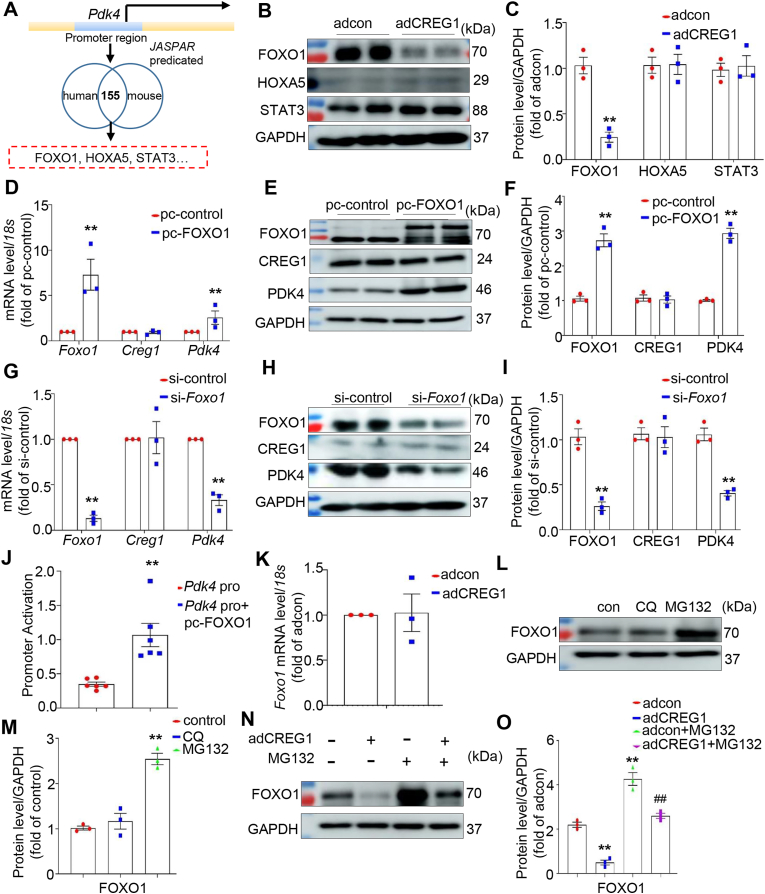

3.12. CREG1 inhibited the mRNA expression of PDK4 by regulating FOXO1 in cardiomyocytes

We used the JASPAR website to predict the transcription factor of the Pdk4 promoter (Fig. 6A) and found that CREG1 overexpression reduced FOXO1 protein expression, however, CREG1 overexpression did not affect the expression of STAT3 and HOXA5 (Fig. 6B-C). In addition, FOXO1 overexpression increased the mRNA and protein levels of PDK4 in NMCMs (Fig. 6D–F), whereas FOXO1 knockdown decreased the mRNA and protein levels of PDK4 in NMCMs (Fig. 6G–I). Luciferase analysis revealed that FOXO1 overexpression increased the promoter activation of the Pdk4 gene in HEK293T cells (Fig. 6J), consistent with a previous study [27].

Fig. 6.

CREG1 inhibited the mRNA and protein expression of PDK4 in cardiomyocytes by regulating FOXO1

A. Transcription factor prediction of Pdk4 gene by JASPAR website.B–C. Western blotting of FOXO1, HOXA5 and STAT3 protein expression in CREG1-overexpressed NMCMs (n = 3). D-F. Effects of FOXO1 overexpression on the mRNA and protein of CREG1 and PDK4 in NMCMs (n = 3). G-I. Effects of FOXO1 knockdown on the mRNA and protein of CREG1 and PDK4 in NMCMs (n = 3). J. Double luciferase reporter gene array in HEK293T cells (n = 6). K. Effects of CREG1 overexpression on the Foxo1 mRNA level in NMCMs (n = 3). L-O. Effects of CREG1 overexpression on FOXO1 protein level under CQ or MG132 treatment. NMCMs: neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes. CQ: chloroquine (10 μM). **p < 0.01 vs. adcon or si-control or Pdk4 pro (WT) or pc-control group; ##p < 0.01 vs. adCREG1 group.

Interestingly, CREG1 overexpression decreased the protein levels of FOXO1 in cardiomyocytes without affecting its mRNA levels (Fig. 6K). CQ, a lysosomal inhibitor, did not affect FOXO1 protein expression. However, MG132, a proteasome inhibitor, significantly increased FOXO1 protein expression (Fig. 6L-M). CREG1 overexpression reduced the protein expression of FOXO1, which was elevated by MG132 treatment (Fig. 6N-O). These results revealed that CREG1 affected the protein degradation of FOXO1 via the proteasome pathway.

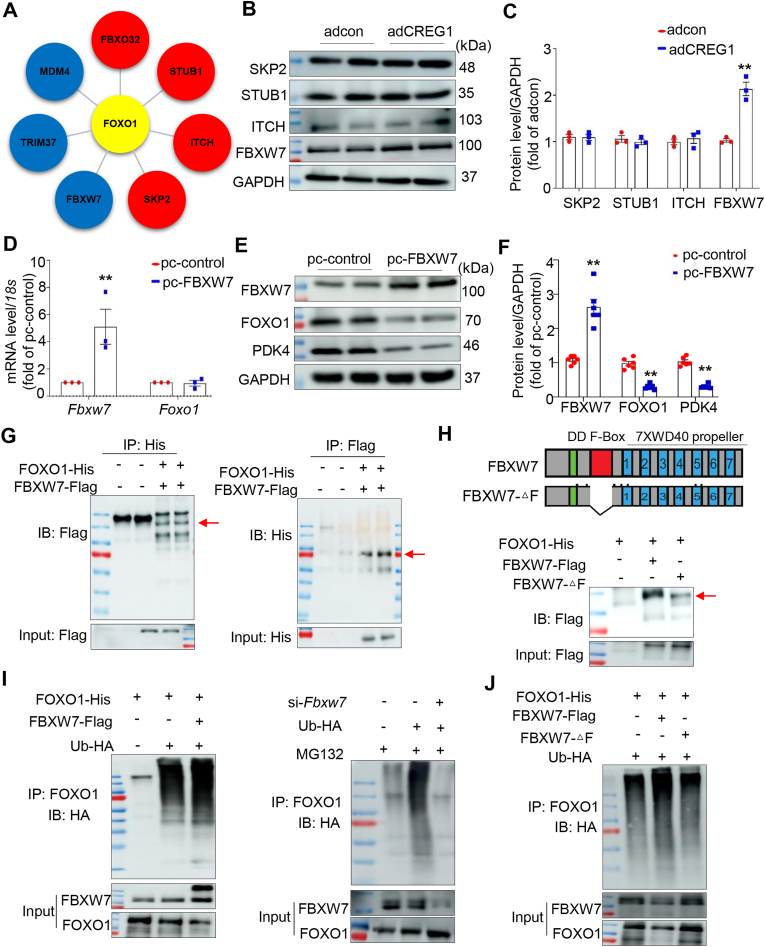

3.13. FBXW7 increased FOXO1 protein degradation via ubiquitination

We used the UbiBrowser website to predict the E3 ubiquitin ligase of FOXO1 (Fig. 7A). We found that CREG1 overexpression did not affect the expression of STUB1, SKP2, and ITCH1 in NMCMs; however, CREG1 overexpression increased FBXW7 expression (Fig. 7B-C) without affecting its mRNA level (Fig. S9A). CREG1 knockdown inhibited FBXW7 protein expression (Figs. S9B–D). In addition, FBXW7 overexpression reduced the protein level of FOXO1 and PDK4 in NMCMs (Fig. 7D–F), whereas FBXW7 knockdown increased the protein level of FOXO1 and PDK4 in NMCMs (Figs. S9E–G). In addition, we also examined the PDK4 protein level in NMCMs with FBXW7 knockdown and FOXO1 knockdown. Compared with si-Fbxw7 group, PDK4 protein was decreased in si-Fbxw7+si-Foxo1 group (Figs. S9H–I), indicating that PDK4 was regulated by FBXW7-FOXO1 pathway.

Fig. 7.

FBXW7 increased FOXO1 protein degradation via ubiquitination

A. Predicted E3 ubiquitin ligase of FOXO1. B–C. Representative western blotting of E3 ubiquitin ligase in CREG1-overexpressed NMCMs (n = 3). D. Effects of FBXW7 overexpression on the FOXO1 mRNA level in NMCMs (n = 3). E-F. Effects of FBXW7 overexpression on the protein level of FOXO1 and PDK4 in NMCMs (n = 6). G. IP assays of the interaction between FBXW7 and FOXO1 in HEK293T cells transfected with the indicated plasmids (n = 3). H. Schematic diagram showing the FBXW7 domains and its truncated mutants (top). IP assays of the binding regions of FBXW7 and FOXO1 (bottom) (n = 3). I. Results of ubiquitination assays confirming FOXO1 ubiquitination after FBXW7 overexpression or knockdown in HEK293T cells (n = 3). J. Results of ubiquitination assays confirming FOXO1 ubiquitination after FBXW7 mutation in HEK293T cells (n = 3). NMCMs: neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes. **p < 0.01 vs. adcon or pc-control.

Direct binding was observed between FOXO1 and FBXW7 (Fig. 7G, Fig. S9J), mainly because of the binding of the FBXW7 F-box domain with FOXO1 (Fig. 7H). FBXW7 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase [28,27]. Its overexpression increased the ubiquitination of FOXO1, whereas its knockdown decreased the ubiquitination of FOXO1 (Fig. 7I); meanwhile, when the deletion of FBXW7-F-box domain, the ubiquitination of FOXO1 was weaker than that of wild-type FBXW7 (Fig. 7J).

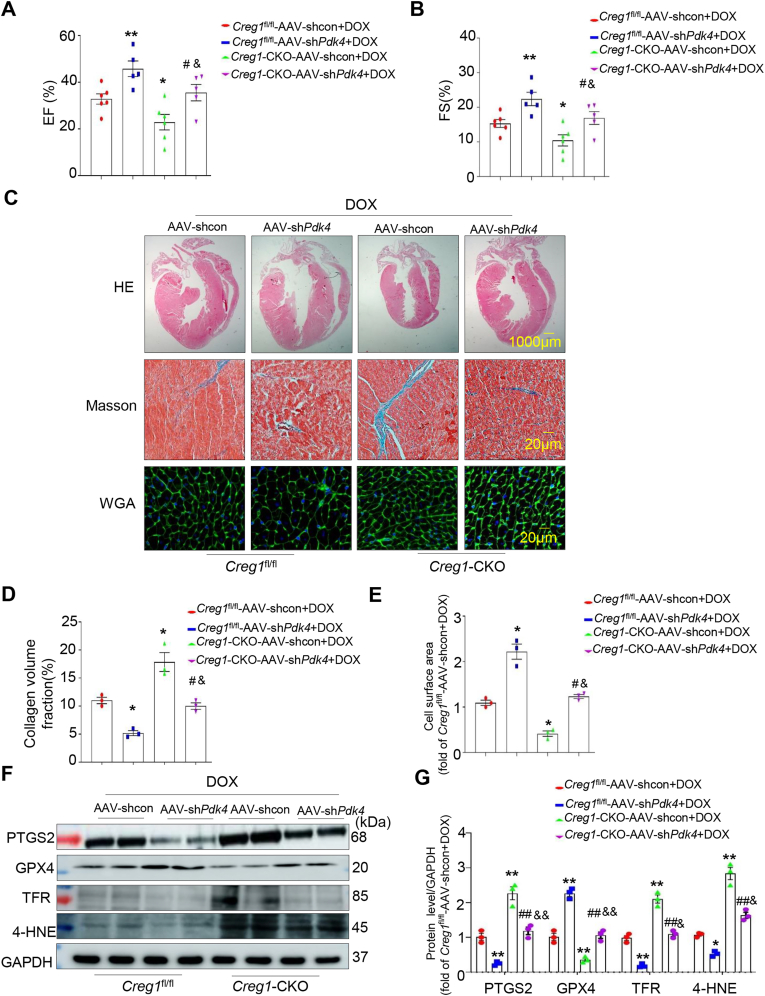

3.14. PDK4 knockdown rescued the effect of CREG1 deficiency in DOX-induced cardiotoxicity

We firstly examined the expressions of FBXW7, FOXO1 and PDK4 in the myocardium of Creg1-TG or Creg1-CKO mice. Compared with the DOX group of Creg1fl/fl mice, FBXW7 expression was reduced and the expressions of FOXO1 and PDK4 were increased in the DOX group of Creg1-CKO mice (Figs. S10A–B). However, compared with the DOX group of WT mice, FBXW7 expression was increased and the expressions of FOXO1 and PDK4 were decreased in the DOX group of Creg1-TG mice (Figs. S10C–D). To further validate the role of PDK4 in CREG1-mediating DOX-induced cardiotoxicity in vivo, AAV-shPdk4 and AAV-shcon were administered to Creg1-CKO and Creg1fl/fl mice, respectively (Fig. S10E). Compared to the AAV-shcon group, the mRNA and protein levels of PDK4 were significantly decreased in the myocardium of the AAV-shPdk4 group (Figs. S10F–H). Under DOX treatment, PDK4 knockdown improved cardiac function (Fig. 8A-B), inhibited myocardial fibrosis and atrophy (Fig. 8C–E) and inhibited ferroptosis (Fig. 8F-G) in Creg1-CKO mice and Creg1fl/fl mice. PDK4 knockdown reversed the detrimental effects of the CREG1 deficiency on DOX-induced cardiotoxicity (Fig. 8A–G).

Fig. 8.

PDK4 knockdown inhibited DOX-induced cardiotoxicity in CREG1 cardiac-specific knockout mice

A-B. EF% and FS% in the Creg1-CKO mice after PDK4 knockdown under DOX treatment (n = 5–6 for each group). C-E. HE staining, Masson’s trichrome staining, and WGA staining in the Creg1-CKO mice after PDK4 knockdown under DOX treatment (n = 3). F-G. Western blotting of ferroptosis-related proteins in the Creg1-CKO mice after PDK4 deficiency under DOX treatment (n = 3). DOX: doxorubicin, Creg1-CKO: Creg1 cardiac-specific knockout mice; Creg1fl/fl mice: littermate control mice. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs. Creg1fl/fl-AAV-shcon+DOX; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 vs. Creg1-CKO-AAV-shcon + DOX; &p < 0.05, &&p < 0.01 vs. Creg1fl/fl-AAV-shPdk4+DOX.

4. Discussion

DOX-induced cardiotoxicity limits the use of DOX in cancer patients. Therefore, it is imperative to identify therapeutic targets to prevent DOX-induced cardiotoxicity. Our study reveals a previously unreported mechanism by which CREG1 overexpression protects against DOX-induced cardiotoxicity via the FBXW7-FOXO1-PDK4 pathway (Fig. S11). These findings suggest that CREG1 is a new and critical potential target for the prevention of DOX-induced cardiotoxicity.

The mechanism of DOX-induced cardiotoxicity is complex and involves multiple factors, including cardiomyocytes apoptosis, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction [[29], [30], [31], [32]]. Accumulating evidence has shown that ferroptosis is involved in DOX-induced cardiotoxicity. DOX-treated cardiomyocytes exhibited ferroptotic cell death. Compared with dexrazoxane, the only FDA-approved drug for treating DOX-induced cardiotoxicity, ferroptosis inhibition by Fer-1 significantly reduced DOX-induced cardiotoxicity. Targeting ferroptosis serves as a cardioprotective strategy to prevent DOX-induced cardiotoxicity [15]. Liu et al. reported that ferroptosis was induced in DOX-treated hearts and the inhibition of ferroptosis using Fer-1 effectively prevented cardiac injury. Acyl-CoA thioesterase 1 (Acot1) may be a potential target for the prevention of DOX-induced cardiotoxicity via anti-ferroptosis [33]. Zhang et al. reported that dexrazoxane had protective effects against DOX-induced cardiotoxicity, which was related to the regulation of ferroptosis [34]. Therefore, improving our functional and molecular understanding of ferroptosis during DOX-induced cardiotoxicity is necessary. In our study, the expression of PTGS2, TFR, and 4-HNE was increased, whereas that of GPX4 was inhibited during DOX-induced cardiotoxicity in vivo and in vitro. In addition, abnormal mitochondria, mitochondrial ROS, mitochondrial membrane potential, and serum MDA levels were increased in DOX-treated myocardium and cardiomyocytes. These results indicated that ferroptosis occurred during DOX-induced cardiotoxicity.

CREG1 is a small glycoprotein that regulates the homeostasis of tissues and cells [[35], [36], [37]]. CREG1 is a protective factor against myocardial damage such as myocardial infarction and ischemia-reperfusion injury [[21], [23]]. However, it remains unclear whether CREG1 protects against DOX-induced cardiotoxicity. The mRNA and protein levels of CREG1 were downregulated in DOX-treated myocardium along with cardiac ferroptosis, indicating that CREG1 might participate in the development of DOX-induced cardiotoxicity by regulating ferroptosis. Loss- and gain-of-function experiments were conducted to elucidate the role of CREG1 in DOX-induced cardiotoxicity. In vivo, CREG1 deficiency impaired cardiac function and induced severe cardiac ferroptosis following DOX treatment. Conversely, CREG1 overexpression significantly improved cardiac function and inhibited cardiac ferroptosis. In vitro, CREG1 overexpression inhibited DOX-induced cardiomyocytes ferroptosis, and CREG1 knockdown increased DOX-induced cardiomyocytes ferroptosis. These results revealed that CREG1 was protective against DOX-induced cardiotoxicity.

PDK4 is an essential mitochondrial matrix enzyme involved in cellular energy regulation and has broad biological effects. PDK4 played a crucial role in vascular calcification through inhibition and metabolic reprogramming [38]. Tan et al. reported that PDK4 was highly expressed in the myocardial tissues of diabetic rats. Silencing PDK4 improved cardiac function and reduced cardiomyocytes apoptosis in diabetes rats [39]. PDK4 inhibition reduced mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membrane (MAM) formation and enhanced insulin signaling by preventing MAM-induced mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and ER stress [40]. These results indicated that PDK4 was important in mitochondrial function and cardiovascular disease.

In our present study, transcriptomic analysis was performed to clarify the mechanism of CREG1 in cardiomyocytes ferroptosis. We found that CREG1 overexpression inhibited the mRNA and protein levels of PDK4, and CREG1 knockdown increased the mRNA and protein levels of PDK4 in DOX-induced myocardium and cardiomyocytes. In addition, PDK4 overexpression increased ferroptosis, aggravated cardiac dysfunction and cardiac fibrosis induced by DOX; while PDK4 knockdown improved cardiac function, inhibited myocardial fibrosis, and inhibited ferroptosis under DOX treatment. Furthermore, PDK4 knockdown reversed the detrimental effects of the CREG1 deficiency on DOX-induced cardiotoxicity. In vitro, CREG1 overexpression decreased PDK4 mRNA levels by inhibiting its transcription factor FOXO1. These results revealed that CREG1 protected against DOX-induced cardiotoxicity by inhibiting the FOXO1-PDK4 pathway.

Ferroptosis is a novel form of programmed cell death characterized by the accumulation of iron-dependent lipid peroxides and is involved in physical conditions and various diseases, including cancers and cardiovascular disease [[41], [42], [43]]. Research on ferroptosis in cancer has boosted the perspective for its use in cancer therapeutics, promoting ferroptosis in cancer cells and inhibiting the proliferation and invasion of cancer cells, thereby inhibiting the development of cancer. Besides, ferroptosis is an important mechanism of DOX-induced cardiotoxicity. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate pretreatment alleviates DOX-induced cardiotoxicity by inhibiting ferroptosis in cardiomyocytes [9]. PRMT4 promotes ferroptosis to aggravate DOX-induced cardiomyopathy via inhibition of the Nrf2/GPX4 pathway. Targeting PRMT4 may be a potential preventive strategy against DOX-induced cardiotoxicity [13]. These results revealed that ferroptosis plays different roles in cancer and DOX-induced cardiotoxicity. PDK4 is an essential mitochondrial matrix enzyme that is involved in cellular energy regulation and has broad biological effects. Song et al. reported that PDK4 inhibits ferroptosis by blocking pyruvate dehydrogenase-dependent pyruvate oxidation in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, revealing that inhibiting PDK4 expression may delay the development of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by promoting ferroptosis in pancreatic cancer cells [44]. In our study, we found that PDK4 overexpression aggravated DOX-induced cardiotoxicity by promoting the ferroptosis of cardiomyocytes and PDK4 knockdown alleviated DOX-induced cardiotoxicity by inhibiting the ferroptosis of cardiomyocytes. Inhibiting PDK4 expression may be a therapeutic target of DOX-induced cardiotoxicity. These results indicated that PDK4 played detrimental roles in the development of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and DOX-induced cardiotoxicity, by regulating the ferroptosis of cancer cells and cardiomyocytes, respectively. The different mechanisms between PDK4 in the ferroptosis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and DOX-induced cardiotoxicity need to be studied in the future.

FBXW7, a member of the F-box protein family, is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that plays an indispensable role in orchestrating cellular processes through the ubiquitination and degradation of its substrates, including Myc proto-oncogene (c-Myc), Notch, cyclin E, and KLF transcription factor 5 (KLF5) [28,27]. FBXW7 promoted the repair of DNA double-strand break damage, an initiating factor for PARP hyperactivation and diabetic vascular complications [45]. FBXW7 was verified as a specific E3 ligase of voltage dependent anion channel 3 (VDAC3). FBXW7 knockdown attenuated VDAC3 degradation by suppressing its ubiquitination, thereby increasing the sensitivity of acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells to erastin [46]. MiR-195-5p promoted cardiac hypertrophy by targeting mitofusin 2 (MFN2) and FBXW7 and may provide promising therapeutic strategies for interfering with cardiac hypertrophy [47]. Wang et al. reported that miR-25 promoted cardiomyocytes proliferation by targeting FBXW7 [48]. In our study, bioinformatics prediction revealed that FBXW7 may be an E3 ubiquitin ligase of FOXO1. We found that CREG1 overexpression increased FBXW7 expression, and CREG1 knockdown inhibited FBXW7 expression in cardiomyocytes. FBXW7 overexpression inhibited FOXO1 protein level by its ubiquitination. These results revealed that CREG1 increased FOXO1 protein degradation by elevating the expression of FBXW7, a new E3 ubiquitin ligase of FOXO1.

There were several limitations in our study. First, CREG1 cardiac specific transgenic mice should be used to clarify the role of CREG1 in DOX-induced cardiotoxicity. Second, previous study reported that DOX could cause ferroptosis and cardiotoxicity by intercalating into mitochondrial DNA and disrupting heme synthesis [49]. They found that DOX accumulated in mitochondria by intercalating into mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), inducing ferroptosis in a mtDNA content-dependent manner. DOX also disrupted heme synthesis, resulting in iron overload and ferroptosis in mitochondria in cultured cardiomyocytes. Whether CREG1 played important roles in cardiomyocytes ferroptosis under DOX treatment was dependent on the mtDNA content and heme synthesis was unclear, which needed to be further studied.

In conclusion, our study revealed that CREG1 could protect against DOX-induced cardiotoxicity by inhibiting cardiomyocytes ferroptosis. These findings provide a new theoretical basis and new ideas for preventing and treating DOX-induced cardiotoxicity.

Sources of funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82070308 and 82270300), the Excellent Youth Fund of Liaoning Natural Science Foundation (2021-YQ-03), The Liaoning Science and Technology Project (2022JH2/101300012).

Availability of data

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the published article.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Dan Liu: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – original draft. Xiaoli Cheng: Data curation, Methodology. Hanlin Wu: Project administration. Haixu Song: Methodology. Yuxin Bu: Methodology. Jing Wang: Methodology, Validation. Xiaolin Zhang: Data curation, Software. Chenghui Yan: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Yaling Han: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization.

Declaration of Competing interest

The authors declared that they had nothing to disclose regarding funding or conflicts of interest with respect to the present study.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the participants of this work.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2024.103293.

Contributor Information

Chenghui Yan, Email: yanch1029@163.com.

Yaling Han, Email: hanyaling@163.net.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Greenberg B.H. Emerging treatment approaches to improve outcomes in patients with heart failure. Cardiol. Discov. 2022;2:231–240. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeng Y.Z. D. Zhao. Rationale, criteria, and impact of identifying extreme risk in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Cardiol. Discov. 2022;2:114–123. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boudoulas K.D., Triposkiadis F., Gumina R., Addison D., Iliescu C., Boudoulas H. Cardiovascular disease, cancer, and multimorbidity interactions. Clin. Impli. Cardiol. 2022;147:196–206. doi: 10.1159/000521680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rawat P.S., Jaiswal A., Khurana A., Bhatti J.S., Navik U. Doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity: an update on the molecular mechanism and novel therapeutic strategies for effective management. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021;139:111708. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schirone L., Vecchio D., Valenti V., Forte M., Relucenti M., Angelini A., Zaglia T., Schiavon S., D'Ambrosio L., Sarto G., et al. MST1 mediates doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy by SIRT3 downregulation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2023;80:245. doi: 10.1007/s00018-023-04877-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swain S.M., Whaley F.S., Ewer M.S. Congestive heart failure in patients treated with doxorubicin: a retrospective analysis of three trials. Cancer. 2003;97:2869–2879. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kong C.Y., Guo Z., Song P., Zhang X., Yuan Y.P., Teng T., Yan L., Tang Q.Z. Underlying the mechanisms of doxorubicin-induced acute cardiotoxicity: oxidative stress and cell death. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022;18:760–770. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.65258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang X., Hu C., Kong C.Y., Song P., Wu H.M., Xu S.C., Yuan Y.P., Deng W., Ma Z.G., Tang Q.Z. FNDC5 alleviates oxidative stress and cardiomyocyte apoptosis in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity via activating AKT. Cell Death Differ. 2020;27:540–555. doi: 10.1038/s41418-019-0372-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He H., Wang L., Qiao Y., Yang B., Yin D., He M. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate pretreatment alleviates doxorubicin-induced ferroptosis and cardiotoxicity by upregulating AMPKalpha2 and activating adaptive autophagy. Redox Biol. 2021;48:102185. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2021.102185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang M., Abudureyimu M., Wang X., Zhou Y., Zhang Y., Ren J. PHB2 ameliorates Doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy through interaction with NDUFV2 and restoration of mitochondrial complex I function. Redox Biol. 2023;65:102812. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2023.102812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dixon S.J., Olzmann J.A. The cell biology of ferroptosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024;25:424–442. doi: 10.1038/s41580-024-00703-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li J., Cao F., Yin H.L., Huang Z.J., Lin Z.T., Mao N., Sun B., Wang G. Ferroptosis: past, present and future. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:88. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2298-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y., Yan S., Liu X., Deng F., Wang P., Yang L., Hu L., Huang K., He J. PRMT4 promotes ferroptosis to aggravate doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy via inhibition of the Nrf2/GPX4 pathway. Cell Death Differ. 2022;29:1982–1995. doi: 10.1038/s41418-022-00990-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang B., Jin Y., Liu J., Liu Q., Shen Y., Zuo S., Yu Y. EP1 activation inhibits doxorubicin-cardiomyocyte ferroptosis via Nrf2. Redox Biol. 2023;65:102825. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2023.102825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang X., Wang H., Han D., Xie E., Yang X., Wei J., Gu S., Gao F., Zhu N., Yin X., et al. Ferroptosis as a target for protection against cardiomyopathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019;116:2672–2680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1821022116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang H., Pan J., Huang S., Chen X., Chang A.C.Y., Wang C., Zhang J., Zhang H. Hydrogen sulfide protects cardiomyocytes from doxorubicin-induced ferroptosis through the SLC7A11/GSH/GPx4 pathway by Keap1 S-sulfhydration and Nrf2 activation. Redox Biol. 2024;70:103066. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2024.103066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu J., Qi Y., Chao J., Sathuvalli P. L YL, Li S. CREG1 promotes lysosomal biogenesis and function. Autophagy. 2021;17:4249–4265. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2021.1909997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song H., Tian X., Liu D., Liu M., Liu Y., Liu J., Mei Z., Yan C., Han Y. CREG1 improves the capacity of the skeletal muscle response to exercise endurance via modulation of mitophagy. Autophagy. 2021;17:4102–4118. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2021.1904488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song H., Li J., Peng C., Liu D., Mei Z., Yang Z., Tian X., Zhang X., Jing Q., Yan C., Han Y. The role of CREG1 in megakaryocyte maturation and thrombocytopoiesis. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2023;19:3614–3627. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.78660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Y., Tian X., Liu S., Liu D., Li Y., Liu M., Zhang X., Yan C., Han Y. DNA hypermethylation: a novel mechanism of CREG gene suppression and atherosclerogenic endothelial dysfunction. Redox Biol. 2020;32:101444. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu D., Tian X., Liu Y., Song H., Cheng X., Zhang X., Yan C., Han Y. CREG ameliorates the phenotypic switching of cardiac fibroblasts after myocardial infarction via modulation of CDC42. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12:355. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-03623-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu D., Xing R., Zhang Q., Tian X., Qi Y., Song H., Liu Y., Yu H., Zhang X., Jing Q., et al. The CREG1-FBXO27-LAMP2 axis alleviates diabetic cardiomyopathy by promoting autophagy in cardiomyocytes. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023;55:2025–2038. doi: 10.1038/s12276-023-01081-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song H., Yan C., Tian X., Zhu N., Li Y., Liu D., Liu Y., Liu M., Peng C., Zhang Q., et al. CREG protects from myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by regulating myocardial autophagy and apoptosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Basis Dis. 2017;1863:1893–1903. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu S.H., Ma K., Xu X.R., Xu B. A single dose of carbon monoxide intraperitoneal administration protects rat intestine from injury induced by lipopolysaccharide. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2010;15:717–727. doi: 10.1007/s12192-010-0183-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song Z., Song H., Liu D., Yan B., Wang D., Zhang Y., Zhao X., Tian X., Yan C., Han Y. Overexpression of MFN2 alleviates sorafenib-induced cardiomyocyte necroptosis via the MAM-CaMKIIdelta pathway in vitro and in vivo. Theranostics. 2022;12:1267–1285. doi: 10.7150/thno.65716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jokar F., Mahabadi J.A., Salimian M., Taherian A., Hayat S.M.G., Sahebkar A., Atlasi M.A. Differential expression of HSP90beta in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cell lines after treatment with doxorubicin. J. Pharmacopuncture. 2019;(22):28–34. doi: 10.3831/KPI.2019.22.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.An H.J., Lee C.J., Lee G.E., Choi Y., Jeung D., Chen W., Lee H.S., Kang H.C., Lee J.Y., Kim D.J., et al. FBXW7-mediated ERK3 degradation regulates the proliferation of lung cancer cells. Exp. Mol. Med. 2022;54:35–46. doi: 10.1038/s12276-021-00721-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao W., Guo N., Zhao S., Chen Z., Zhang W., Yan F., Liao H., Chi K. FBXW7 promotes pathological cardiac hypertrophy by targeting EZH2-SIX1 signaling. Exp. Cell Res. 2020;393:112059. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2020.112059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen S., Chen J., Du W., Mickelsen D.M., Shi H., Yu H., Kumar S., Yan C. PDE10A inactivation prevents doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity and tumor growth. Circ. Res. 2023;133:138–157. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.122.322264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu C., Zhang X., Song P., Yuan Y.P., Kong C.Y., Wu H.M., Xu S.C., Ma Z.G., Tang Q.Z. Meteorin-like protein attenuates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity via activating cAMP/PKA/SIRT1 pathway. Redox Biol. 2020;37:101747. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang A.J., Tang Y., Zhang J., Wang B.J., Xiao M., Lu G., Li J., Liu Q., Guo Y., Gu J. Cardiac SIRT1 ameliorates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by targeting sestrin 2. Redox Biol. 2022;52:102310. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2022.102310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tai P., Chen X., Jia G., Chen G., Gong L., Cheng Y., Li Z., Wang H., Chen A., Zhang G., et al. WGX50 mitigates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity through inhibition of mitochondrial ROS and ferroptosis. J. Transl. Med. 2023;21:823. doi: 10.1186/s12967-023-04715-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Y., Zeng L., Yang Y., Chen C., Wang D., Wang H. Acyl-CoA thioesterase 1 prevents cardiomyocytes from Doxorubicin-induced ferroptosis via shaping the lipid composition. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:756. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-02948-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang H., Wang Z., Liu Z., Du K., Lu X. Protective effects of dexazoxane on rat ferroptosis in doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy through regulating HMGB1. Front. Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:685434. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.685434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu M., Yin F., Wei X., Ren R., Chen C., Liu M., Wang R., Yang L., Xie R., Jiang S., et al. Hepatocyte-specific deletion of cellular repressor of E1A-stimulated genes 1 exacerbates alcohol-induced liver injury by activating stress kinases. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022;18:1612–1626. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.67852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hashimoto M., Goto A., Endo Y., Sugimoto M., Ueda J., Yamashita H. Effects of CREG1 on age-associated metabolic phenotypes and renal senescence in mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021:22. doi: 10.3390/ijms22031276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peng C., Shao X., Tian X., Li Y., Liu D., Yan C., Han Y. CREG ameliorates embryonic stem cell differentiation into smooth muscle cells by modulation of TGF-beta expression. Differentiation. 2022;125:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2022.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma W.Q., Sun X.J., Zhu Y., Liu N.F. PDK4 promotes vascular calcification by interfering with autophagic activity and metabolic reprogramming. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:991. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-03162-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tan W., Bao H., Liu Z., Liu Y., Hong L., Shao L. Protein PDK4 interacts with HMGCS2 to facilitate high glucoseinduced myocardial injuries. Curr. Mol. Med. 2023;23:1104–1115. doi: 10.2174/1566524023666221021124202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thoudam T., Ha C.M., Leem J., Chanda D., Park J.S., Kim H.J., Jeon J.H., Choi Y.K., Liangpunsakul S., Huh Y.H., et al. PDK4 augments ER-mitochondria contact to dampen skeletal muscle insulin signaling during obesity. Diabetes. 2019;68:571–586. doi: 10.2337/db18-0363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang X., Stockwell B.R., Conrad M. Ferroptosis: mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021;22:266–282. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-00324-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu T., Ding W., Ji X., Ao X., Liu Y., Yu W., Wang J. Molecular mechanisms of ferroptosis and its role in cancer therapy. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2019;23:4900–4912. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fang X., Ardehali H., Min J., Wang F. The molecular and metabolic landscape of iron and ferroptosis in cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2023;20:7–23. doi: 10.1038/s41569-022-00735-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Song X., Liu J., Kuang F., Chen X., Zeh H.J., 3rd, Kang R., Kroemer G., Xie Y., Tang D. PDK4 dictates metabolic resistance to ferroptosis by suppressing pyruvate oxidation and fatty acid synthesis. Cell Rep. 2021;34:108767. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.108767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li S., Deng J., Sun D., Chen S., Yao X., Wang N., Zhang J., Gu Q., Zhang S., Wang J., et al. FBXW7 alleviates hyperglycemia-induced endothelial oxidative stress injury via ROS and PARP inhibition. Redox Biol. 2022;58:102530. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2022.102530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu T., Liu B., Wu D., Xu G., Fan Y. Autophagy regulates VDAC3 ubiquitination by FBXW7 to promote erastin-induced ferroptosis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021;9:740884. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.740884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang L., Qin D., Shi H., Zhang Y., Li H., Han Q. MiR-195-5p promotes cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by targeting MFN2 and FBXW7. BioMed Res. Int. 2019;2019:1580982. doi: 10.1155/2019/1580982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang B., Xu M., Li M., Wu F., Hu S., Chen X., Zhao L., Huang Z., Lan F., Liu D., Wang Y. miR-25 promotes cardiomyocyte proliferation by targeting FBXW7. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2020;19:1299–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2020.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abe K., Ikeda M., Ide T., Tadokoro T., Miyamoto H.D., Furusawa S., Tsutsui Y., Miyake R., Ishimaru K., Watanabe M., et al. Doxorubicin causes ferroptosis and cardiotoxicity by intercalating into mitochondrial DNA and disrupting Alas1-dependent heme synthesis. Sci. Signal. 2022;15 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.abn8017. eabn8017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the published article.