Abstract

Background.

Mexico implemented routine childhood vaccination against rotavirus in 2007. We describe trends in hospitalization and deaths from diarrhea among children aged <5 years in Mexico before and 7 years after implementation of rotavirus vaccination.

Methods.

We obtained data on deaths and hospitalizations from diarrhea, from January 2003 through December 2014, in Mexican children <5 years of age. We compared diarrhea-related mortality and hospitalizations in the postvaccine era with the prevaccine baseline from 2003 to 2006.

Results.

Compared with the prevaccine baseline, we observed a 53% reduction (95% confidence interval [CI], 47%–58%) in diarrhea-related mortality and a 47% reduction (95% CI, 45%–48%) in diarrhea-related hospitalizations in postvaccine years, translating to 959 deaths and 5831 hospitalizations averted every year in Mexican children aged <5 years. Prevaccine peaks in diarrhea-related mortality and hospitalizations during the rotavirus season months were considerably diminished in postvaccine years, with greater declines observed during the rotavirus season compared with non–rotavirus season months.

Conclusions.

We document a substantial and sustained decline in diarrhea-related hospitalizations and deaths in Mexican children associated with implementation of rotavirus vaccination. These results highlight the public health benefits that could result in countries that adopt rotavirus vaccination into their national immunization programs.

Keywords: rotavirus vaccines, diarrhea, mortality, hospitalizations, Mexico

Worldwide, diarrheal disease remains a leading cause of death in children aged <5 years (hereafter “under 5”) [1]. Rotavirus is the most common cause of severe diarrhea in children and is most frequently associated with cases of dehydration, hospitalization, and death [2]. Globally, it is responsible for about 40% of all diarrhea-related hospitalizations and was estimated to cause 453 000 deaths in 2008 [2, 3]. Rotavirus infection has a strong seasonal pattern [4, 5]; in Mexico, approximately 60%–70% of the hospitalizations for laboratory-confirmed rotavirus infection occur during the months of October–March [6, 7].

RotaTeq (Merck & Co, Whitehouse Station, New Jersey) and Rotarix (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals, Rixensart, Belgium), the 2 rotavirus vaccines available on the global market, have been shown to be safe and effective in large-scale prelicensure studies [8–17]. Since the recommendation of the World Health Organization to introduce rotavirus vaccines into every country’s national immunization program (NIP), >75 countries have implemented rotavirus vaccines [18, 19]. Mexico was one of the first nations to introduce, in May 2007, the rotavirus vaccine in its national immunization program. Rotarix was used during the first 5 years (2006–2011), administered in a 2-dose schedule. In 2011, due to known similar efficacy for both vaccines, a complete-schedule price competition was set by the government, and monovalent vaccine was substituted with pentavalent vaccine, RotaTeq, administered on a 3-dose schedule.

Monitoring the impact of rotavirus immunization against diarrhea deaths and hospitalizations during routine use will be important to better understand the potential of these vaccines. Two years after implementation of rotavirus vaccination, a 35% reduction in the mortality rate and a 40% reduction in the hospitalization rate from diarrhea were observed in children under 5. These reductions were significant in children aged 0–23 months, but not in children aged 24–59 months [20, 21]. Once 4 annual cohorts were vaccinated with the monovalent vaccine by 2010, the reduction in mortality was 50%, with a significant reduction in all subgroups of children under 5 and with no differences across regions with different socioeconomic levels of Mexico [22, 23]. In this study, we include an additional 3 years of postvaccine data to describe trends in hospitalization and deaths from diarrhea among children under 5 in Mexico before and 7 years after implementation of universal rotavirus vaccination.

METHODS

All-Cause and Diarrhea-Related Hospitalizations

We accessed data from the Ministry of Health’s National System for Health Information to obtain monthly data on all-cause and diarrhea-related hospitalizations among children aged <5 years, from January 2003 to December 2014, for all of Mexico’s 677 Ministry of Health hospitals. These hospitals cover about 50% of the hospitalizations nationwide in public hospitals. International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes A00–A03, A04, A05, A06.0–A06.3, A06.9, A07.0–A07.2, A07.9, and A08–A09 were used to select diarrhea-related hospitalizations. No attempt was made to evaluate hospitalizations specifically caused by rotavirus infection because there is no systematic laboratory testing for rotavirus in children hospitalized for diarrhea in Mexico.

Diarrhea-Related Deaths

For the period from January 2003 through December 2014, we obtained data on diarrhea-related deaths among Mexican children under 5 from the National Institute of Statistics, Geography, and Informatics and the Ministry of Health’s General Directorate of Health Information, which collects information from all death certificates. We used the same ICD-10 codes used to select diarrhea hospitalizations to select diarrhea-related deaths.

Vaccine Coverage

The Mexico National Health and Nutrition Survey for 2012 reports coverage with a complete rotavirus vaccine schedule of 63% for children <1 year and 80% for those <2 years of age [24]. Coverage from the National Health and Nutrition Survey 2012 could be underestimated due to underreporting of doses applied in the national immunization and health card [25].

Other studies using administrative coverage data (doses administered/the estimated target population) have estimated the coverage rate for a complete vaccine series to be 90% for children aged <1 year [22, 23, 25]. Administrative coverage could be imprecise because the estimated population, in some scenarios, could be higher or lower than the number of actual targeted population.

Prevaccine and Postvaccine Periods

The prevaccine period was defined as January 2003 to December 2006; 2007 was considered a transition year after vaccine introduction. Postvaccine period was considered according to age group to account for the moment when the first vaccinated cohort reached the age group: <12 months from January 2008 to December 2014, 12–23 months from January 2009 to December 2014, and 24–59 months from January 2010 to December 2014. In addition, according to the timing of detection of rotavirus in sentinel laboratory surveillance in Mexico, we defined the rotavirus season as occurring from November to March.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were restricted to children <5 years of age and were stratified by age: ≤11 months, 12–23 months, and 24–59 months. National Population Council population estimates were used as denominators [26].

We compared median annual diarrhea mortality rates and median annual absolute number of diarrhea-related deaths in the prevaccine and postvaccine periods. We also compared the median absolute number and rate of diarrhea-related deaths during the peak rotavirus season in the prevaccine and postvaccine periods.

Overall numbers of diarrhea-related hospitalizations from January 2003 to December 2014 were examined. Because the catchment populations of the study hospitals were not known, rates of hospitalization for diarrhea per 100 hospitalizations from all causes were calculated. The median annual rate of diarrhea-related hospitalizations in the prevaccine period was compared with the postvaccine period. To improve specificity of vaccination effect on rotavirus disease, we also restricted our analysis to hospitalizations during the rotavirus season among children <5 years of age.

Diseases recorded on the same information systems where we obtain the deaths and hospitalizations due to diarrhea were used as controls to show that the reduction effect seen in diarrhea mortality and hospitalizations was not an artifact of the record or an unspecific trend. As controls we have included congenital heart malformation mortality for diarrhea deaths, and hospitalization due to injuries for diarrhea hospitalizations.

We estimated the national reductions in diarrhea-related hospitalizations that could reasonably be attributed to the rotavirus vaccinations by extrapolating the rates of diarrhea-related hospitalization per 100 all-cause admissions—observed in the Ministry of Health hospitals, which attend to about 50% of the population—to the total number of hospital admissions for all causes observed countrywide.

We calculated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the rate reductions in diarrhea-related deaths and diarrhea-related hospitalizations by CI for comparing 2 independent proportions. A 2-sided P value of <.05, as calculated with a χ2 test, was considered significant. Analyses were performed with Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington).

RESULTS

Mortality

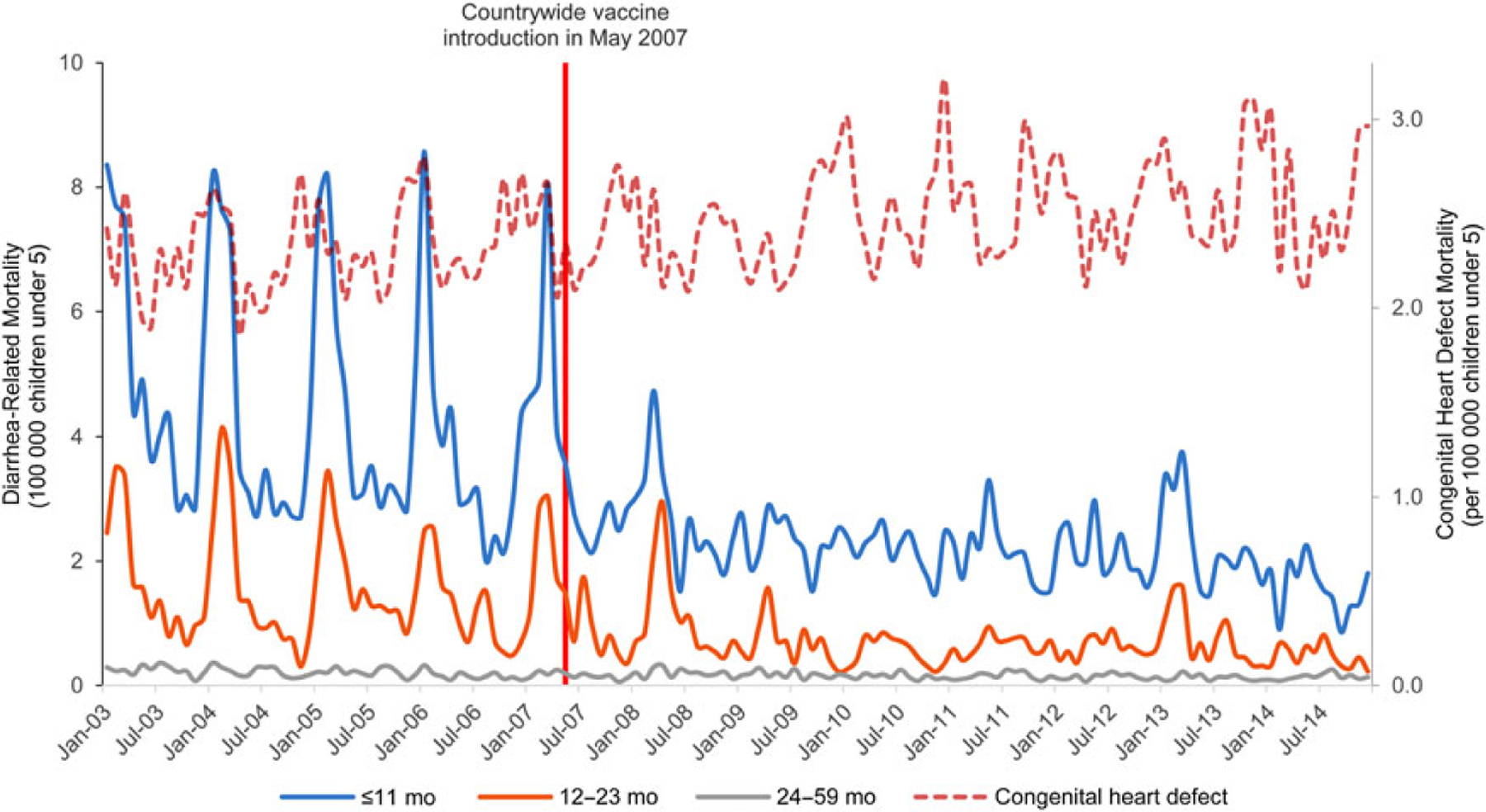

From January 2003 to December 2014, there were 14 808 registered deaths in Mexican children under 5, with 66.2% occurring in children 0–11 months, 22.3% in children 12–23 months, and 11.5% in children 24–59 months of age. Monthly mortality showed the strong seasonal pattern of high peaks in cold months from January to April, mainly in the prevaccine period. After the introduction and universalization of the rotavirus vaccines, seasonal peaks were drastically reduced and seasonality become less evident (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Diarrhea-related mortality among children aged ≤59 months from 2003 through 2014 in Mexico, by age group.

In the prevaccine years, there was a median number of 1198 diarrhea-related deaths annually in children 0–11 months, 421 in children 12–23 months, and 175 in children 24–59 months of age, with median annual mortality rates of 52.7, 18.6, and 2.6 deaths per 100 000, respectively. In the postvaccine period, the median number of annual deaths was reduced to 563 in children 0–11 months, 158 in children 12–23 months, and 114 in children 24–59 months of age, with median annual mortality rates of 25.4, 7.1, and 1.7 deaths per 100 000, respectively. This represents significant reductions in the mortality rate of 52% (96% CI, 45%–59%), 62% (96% CI, 50%–73%), and 34% (96% CI, 15%–55%) in children 0–11 months, 12–23 months, and 24–59 months of age, respectively. Overall in children under 5, we observed a 53% reduction (95% CI, 47%–58%) in diarrhea-related mortality rates post–vaccine introduction, with about 959 deaths averted every year in children under 5 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Changes in Diarrhea-Related Mortality Among Children <5 Years of Age in the Postvaccine Period Compared With the Prevaccine Period, by Age Group

| Median Annual No. of Diarrhea-Related Deaths |

Median Annual Diarrhea-Related Death Rate (No. of Deaths per 100 000 Under-5 Children) |

Absolute Reduction |

Relative Reduction in Death Rate, % (95% CI) | P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group | Prevaccine | Postvaccine | Prevaccine | Postvaccine | No. of Deaths | Death Rate (No. of Deaths per 100 000 Under-5 Children) | ||

| All ages (0–59 mo) | 1794 | 835 | 15.8 | 7.5 | 959 | 8.3 | 53 (47–58) | <.001 |

| ≤11 mo | 1198 | 563 | 52.7 | 25.4 | 635 | 27.3 | 52 (45–59) | <.001 |

| 12–23 mo | 421 | 158 | 18.6 | 7.1 | 264 | 11.5 | 62 (50–73) | <.001 |

| 24–59 mo | 175 | 114 | 2.6 | 1.7 | 61 | 0.9 | 34 (15–53) | <.001 |

| Congenital heart defect 0–59 mo | 3177 | 3362 | 27.9 | 30.1 | −186 | −2.2 | −8 (−13 to −3) | <.001 |

P values were calculated with the use of a χ2 test. Negative values imply relative increase. Prevaccine period was defined as January 2003 to December 2006. Postvaccine period: age ≤11 months from January 2008 to December 2014, age 12–23 months from January 2009 to December 2014, and age 24–59 months from January 2010 to December 2014.

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

The reductions were more evident when the analysis was restricted to the rotavirus season, showing a reduction in mortality rate of 67% in children under 5 during the rotavirus season, which highlights the impact on the diarrhea mortality of the rotavirus vaccination (Table 2).

Table 2.

Changes in Diarrhea-Related Mortality Among Children <5 Years of Age in the Postvaccine Period Compared With the Prevaccine Period During Rotavirus Season

| Median No. of Diarrhea-Related Deaths |

Median Diarrhea-Related Death Rate (No. of Deaths per 100 000 Under-5 Children) |

Absolute Reduction in No. of Deaths per 100 000 Under-5 Children |

Relative Reduction in Death Rate, % (95% CI) | P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group | Prevaccine | Postvaccine | Prevaccine | Postvaccine | No. of Deaths | Death Rate | ||

| All ages (0–59 mo) | 997 | 325 | 8.8 | 2.95 | 672 | 5.9 | 67 (60–74) | <.001 |

| ≤11 mo | 684 | 232 | 30.1 | 10.5 | 452 | 19.6 | 65 (56–74) | <.001 |

| 12–23 mo | 241 | 54 | 10.6 | 2.4 | 187 | 8.2 | 77 (63–91) | <.001 |

| 24–59 mo | 72 | 39 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 33 | 0.5 | 45 (16–74) | <.001 |

| Congenital heart defect 0–59 mo | 1423 | 1516 | 12.5 | 13.3 | −0.9 | −1.1 | −9 (−16 to −1) | <.001 |

P values were calculated with the use of a χ2 test. Negative values imply relative increase. Prevaccine period was defined as January 2003 to December 2006.

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

As a control, in the same population, in the same information system, in the same periods, mortality due to congenital heart malformations did not show any reduction (Table 1; Figure 1).

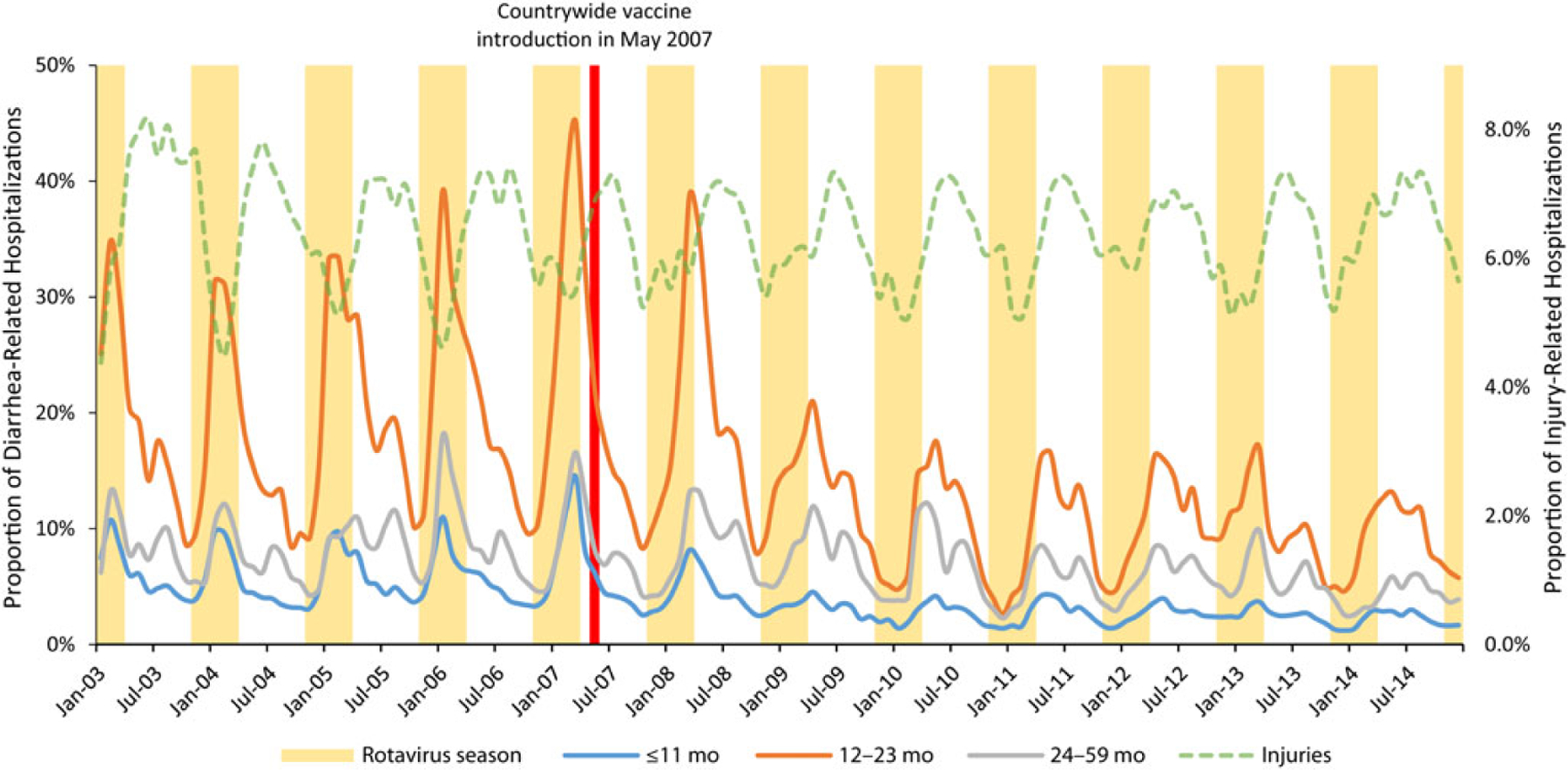

Hospitalizations

From January 2003 to December 2014, there were 189 837 diarrhea-related hospitalizations in children under 5, with 42.3% occurring in children 0–11 months, 32.2% in children 12–23 months, and 25.4% in children 24–59 months of age. Monthly hospitalization rates also showed a clear seasonal pattern of high peaks in cold months, mainly in the prevaccine period. After the introduction of rotavirus vaccines, seasonal peaks were considerably reduced, with declines sustained throughout the postvaccine period (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Proportion of diarrhea-related hospitalizations among children aged ≤59 months from 2003 through 2014 in Mexico, by age group.

In prevaccine years, the median number of annual hospitalizations was 8212 in children 0–11 months, 5823 in children 12–23 months, and 3728 in children 24–59 months of age, with median annual hospitalization proportions of 5.6, 20.2, and 7.9 hospitalizations per 100 hospitalizations in children of these ages, respectively. In the postvaccine periods, the median number of annual hospitalizations was reduced to 4926 in children 0–11 months, 3445 in children 12–23 months, and 3562 in children 24–59 months of age, even when the total number of hospitalizations increased by 26%. These median frequencies corresponded to median annual hospitalization proportions of 2.7, 10.2, and 5.5 diarrhea patients per 100 hospitalizations, respectively. This represents significant reductions in hospitalizations of 52% (96% CI, 50%–54%), 49% (96% CI, 47%–52%), and 30% (96% CI, 26%–34%) in children 0–11 months, 12–23 months, and 24–59 months of age, respectively. Overall, in children under 5, we estimate a 47% reduction (95% CI, 45%–48%) in diarrhea-related hospitalizations, with about 5831 hospitalizations averted every year in children under 5 in Ministry of Health (MOH) hospitals (about 11 662 in the country). As a control, in the same population, in the information system, in the same periods, hospitalizations due to injuries did not show a significant important reduction (Figure 2; Table 3).

Table 3.

Changes in Diarrhea-Related Hospitalizations Among Children <5 Years of Age in the Postvaccine Period Compared With the Prevaccine Period, by Age Group

| Median Annual No. of Diarrhea-Related Hospitalizations |

Median Annual Diarrhea-Related Hospitalizations, % |

Absolute Reduction Proportion of Hospitalizations | Relative Reduction in Hospitalizations, Proportion (95% CI) % | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group | Prevaccine | Postvaccine | Prevaccine | Postvaccine | |||

| All ages (0–59 mo) | 17 763 | 11 933 | 8.0 | 4.3 | 3.7 | 47 (45–48) | <.001 |

| ≤11 mo | 8212 | 4926 | 5.6 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 52 (50–54) | <.001 |

| 12–23 mo | 5823 | 3445 | 20.2 | 10.2 | 10.0 | 49 (47–52) | <.001 |

| 24–59 mo | 3728 | 3562 | 7.8 | 5.5 | 2.3 | 30 (26–34) | <.001 |

| Injuries 0–59 mo | 14 145 | 17 518 | 6.37 | 6.26 | 0.12 | 2 (0–4) | .09 |

P values were calculated with the use of a χ2 test. Prevaccine period was defined as January 2003 to December 2006. Postvaccine period: age ≤11 months from January 2008 to December 2014, age 12–23 months from January 2009 to December 2014, and age 23–59 months from January 2010 to December 2014.

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

In prevaccine years, 55% of diarrhea-related hospitalizations occurred during the rotavirus season. After the introduction of the rotavirus vaccine, during the rotavirus season, diarrhea-related hospitalizations decreased 66% in children under 5, with reductions of 68% in the group of 0–11 months and 12–23 months. In postvaccine years, only 33% of all diarrhea-related hospitalizations occur during the rotavirus season, showing a specific impact of the rotavirus vaccines with more important reductions in the rotavirus seasons (Table 4).

Table 4.

Changes in Diarrhea-Related Hospitalizations Among Children <5 Years of Age in the Postvaccine Period Compared With the Prevaccine Period During Rotavirus Season

| Median No. of Diarrhea-Related Hospitalizations |

Median Diarrhea-Related Hospitalizations, Proportion |

Absolute Reduction Proportion of Hospitalization | Relative Reduction in Hospitalizations, Proportion (95% CI) % | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group | Prevaccine | Postvaccine | Prevaccine | Postvaccine | |||

| All ages (0–59 mo) | 9748 | 3952 | 9.8 | 3.4 | 6.4 | 66 (64–68) | <.001 |

| ≤11 mo | 4573 | 1719 | 7.0 | 2.2 | 4.8 | 68 (65–71) | <.001 |

| 12–23 mo | 3507 | 1143 | 24.5 | 7.8 | 16.7 | 68 (65–72) | <.001 |

| 24–59 mo | 1668 | 1090 | 8.3 | 4.2 | 4.1 | 50 (45–55) | <.001 |

P values were calculated with the use of a χ2 test.

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

Rotavirus vaccine has contributed significantly toward reaching the Millennium Development Goal 4 target in counties where rotavirus vaccines have been introduced [27].

After the implementation of universal rotavirus vaccination in Mexico in 2007, substantial declines in childhood diarrhea deaths and admissions were observed [20–23]. Seven years after the introduction of rotavirus vaccines in the NIP, diarrhea mortality continues to decrease, with a decline of 53% in diarrhea deaths, representing about 6328 averted deaths since vaccine introduction. All-cause diarrhea-related hospitalizations have also declined since 2007, with the highest impact observed during rotavirus seasons. During these months, a reduction of 66% was seen for all diarrhea hospitalizations, with 37 050 hospitalizations adverted during fall/winter seasons in MOH hospitals, and about 74 099 in the country.

We examined all-cause diarrhea-related deaths and hospitalizations, as we did not have verifiable information on laboratory-confirmed rotavirus events. Consequently, the results could be affected by secular trends in diarrhea related to other pathogens to some extent. Nevertheless, the seasonal pattern of all diarrhea-related deaths and hospitalizations follow the same fall/winter seasonality of rotavirus, allowing us to indirectly assess the effect of vaccination on the mortality and the proportion of diarrhea-related hospitalizations. In addition, the stepped shape of the reduction by age groups, as they became vaccine eligible, support the effect of the rotavirus vaccine. In initial reports, no statistically significant reduction was observed in diarrhea mortality or diarrhea hospitalizations in children 24–59 months of age. It was not until the entire annual cohort of under-5 children was vaccinated that reduction was observed in the group of children 24–59 months of age. Finally, there was a noticeable flattening of the seasonal peaks in diarrhea mortality and diarrhea-related hospitalizations, with the greatest decrease seen during the rotavirus season, further supporting a role for rotavirus vaccination in the observed decline.

Additionally, the data sources we used may have been subject to some underreporting and classification error. Nevertheless, underreporting would likely be similar during the periods before and after the introduction of the vaccination program, and thus unlikely to produce major bias. Furthermore, to exclude the possibility of bias from changes in the reporting system, we used other conditions as a control, and it was reassuring that these control conditions did not demonstrate any secular trend.

Our findings are in accord with other Latin American findings, with decreases of 17%–55% in all-cause diarrhea hospitalizations and effectiveness against rotavirus diarrhea hospitalizations ranging from 17% to 94% [28–33]. Mexico’s reductions in diarrhea-related deaths are similar to other Latin American countries, which report a decline of 22%–50% [32, 34, 35]. These results highlight the public health benefits that could result in countries that adopt rotavirus vaccination as part of their NIPs.

In summary, we documented a substantial and sustained decline in diarrhea-related hospitalizations and deaths in Mexican children associated with implementation of rotavirus vaccination. These data highlight the real-world value of vaccination and should encourage other countries to consider vaccination as a strategy to reduce the burden of severe childhood diarrhea.

Footnotes

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The views expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the views of PATH, the CDC Foundation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, or GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance.

Supplement sponsorship. This article appears as part of the supplement “Health Benefits of Rotavirus Vaccination in Developing Countries,” sponsored by PATH and the CDC Foundation through grants from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Black RE, Cousens S, Johnson HL, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2008: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2010; 375:1969–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotloff KL, Nataro JP, Blackwelder WC, et al. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. Lancet 2013; 382:209–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tate JE, Burton AH, Boschi-Pinto C, et al. 2008 estimate of worldwide rotavirus-associated mortality in children younger than 5 years before the introduction of universal rotavirus vaccination programmes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2012; 12:136–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Villa S, Guiscafré H, Martínez H, Muñoz O, Gutiérrez G. Seasonal diarrhoeal mortality among Mexican children. Bull World Health Organ 1999; 77:375–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kapikian AZ, Kim HW, Wyatt RG, et al. Human reovirus-like agent as the major pathogen associated with “winter” gastroenteritis in hospitalized infants and young children. N Engl J Med 1976; 294:965–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Velázquez FR, Garcia-Lozano H, Rodriguez E, et al. Diarrhea morbidity and mortality in Mexican children: impact of rotavirus disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2004; 23 (10 suppl):S149–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Velázquez FR, Calva JJ, Guerrero ML, et al. Cohort study of rotavirus serotype patterns in symptomatic and asymptomatic infections in Mexican children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1993; 12:54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruiz-Palacios GM, Pérez-Schael I, Velázquez R, Abate H, Breuer T, et al. Safety and efficacy of an attenuated vaccine against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vesikari T, Matson DO, Dennehy P, Van Damme P, Santosham M, et al. Safety and efficacy of a pentavalent human-bovine (WC3) reassortant rotavirus vaccine. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwata S, Nakata S, Ukae S, et al. Efficacy and safety of pentavalent rotavirus vaccine in Japan: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2013; 9:1626–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zaman K, Dang DA, Victor JC, et al. Efficacy of pentavalent rotavirus vaccine against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis in infants in developing countries in Asia: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2010; 376:615–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armah GE, Sow SO, Breiman RF, et al. Efficacy of pentavalent rotavirus vaccine against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis in infants in developing countries in sub-Saharan Africa: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2010; 376:606–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sow SO, Tapia M, Haidara FC, et al. Efficacy of the oral pentavalent rotavirus vaccine in Mali. Vaccine 2012; 30(suppl 1):A71–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salinas B, Pérez Schael I, Linhares AC, et al. Evaluation of safety, immunogenicity and efficacy of an attenuated rotavirus vaccine, RIX4414: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial in Latin American infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2005; 24:807–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vesikari T, Karvonen A, Prymula R, et al. Efficacy of human rotavirus vaccine against rotavirus gastroenteritis during the first 2 years of life in European infants: randomised, double-blind controlled study. Lancet 2007; 370:1757–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruiz-Palacios GM, Guerrero ML, Bautista-Márquez A, et al. Dose response and efficacy of a live, attenuated human rotavirus vaccine in Mexican infants. Pediatrics 2007; 120:e253–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tate JE, Parashar UD. Rotavirus vaccines in routine use. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59:1291–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel MM, Steele D, Gentsch JR, Wecker J, Glass R, Parashar UD. Real-world impact of rotavirus vaccination. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2011; 30(1 suppl):S1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Health Section of the Secretariat of the League of Nations. Conclusions and recommendations from the Immunization Strategic Advisory Group. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2006; 81:2–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richardson V, Hernandez-Pichardo J, Quintanar-Solares M, et al. Effect of rotavirus vaccination on death from childhood diarrhea in Mexico. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quintanar-Solares M, Yen C, Richardson V, Esparza-Aguilar M, Parashar UD, Patel MM. Impact of rotavirus vaccination on diarrhea-related hospitalizations among children <5 years of age in Mexico. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2011; 30(1 suppl):S11–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gastañaduy PA, Sánchez-Uribe E, Esparza-Aguilar M, et al. Effect of rotavirus vaccine on diarrhea mortality in different socioeconomic regions of Mexico. Pediatrics 2013; 131:e1115–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Esparza-Aguilar M, Gastañaduy PA, Sánchez-Uribe E, et al. Diarrhoea-related hospitalizations in children before and after implementation of monovalent rotavirus vaccination in Mexico. Bull World Health Organ 2014; 92:117–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gutierrez JP, Rivera-Dommarco J, Shamah-Levy T, et al. Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición 2012. Resultados nacionales. Cuernavaca, México: Instituto Nacional de Salud Publica, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Díaz-Ortega JL, Ferreira-Guerrero E, Trejo-Valdivia B, et al. Vaccination coverage in children and adolescents in Mexico: vaccinated, under vaccinated and non vaccinated [in Spanish]. Salud Publica Mex 2013; 55(suppl 2):S289–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Consejo Nacional de Población. Proyecciones de la población nacional 2010–2050. México City: CONAPO, 2012. Available at: http://www.conapo.gob.mx/es/CONAPO/Proyecciones. Accessed 18 August 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bustreo F, Okwo-Bele JM, Kamara L. World Health Organization perspectives on the contribution of the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization on reducing child mortality. Arch Dis Child 2015; 100(suppl 1):S34–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Desai R, Oliveira LH, Parashar UD, Lopman B, Tate JE, Patel MM. Reduction in morbidity and mortality from childhood diarrhoeal disease after species A rotavirus vaccine introduction in Latin America—a review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2011; 106:907–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yen C, Armero Guardado JA, Alberto P, et al. Decline in rotavirus hospitalizations and health care visits for childhood diarrhea following rotavirus vaccination in El Salvador. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2011; 30(1 suppl):S6–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.do Carmo GM, Yen C, Cortes J, et al. Decline in diarrhea mortality and admissions after routine childhood rotavirus immunization in Brazil: a time-series analysis. PLoS Med 2011; 8:e1001024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Safadi MA, Berezin EN, Munford V, et al. Hospital-based surveillance to evaluate the impact of rotavirus vaccination in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2010; 29:1019–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gurgel RG, Bohland AK, Vieira SC, et al. Incidence of rotavirus and all-cause diarrhea in northeast Brazil following the introduction of a national vaccination program. Gastroenterology 2009; 137:1970–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Molto Y, Cortes JE, De Oliveira LH, et al. Reduction of diarrhea-associated hospitalizations among children aged <5 years in Panama following the introduction of rotavirus vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2011; 30(1 suppl):S16–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lanzieri TM, Linhares AC, Costa I, et al. Impact of rotavirus vaccination on childhood deaths from diarrhea in Brazil. Int J Infect Dis 2011; 15: e206–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bayard V, DeAntonio R, Contreras R, et al. Impact of rotavirus vaccination on childhood gastroenteritis-related mortality and hospital discharges in Panama. Int J Infect Dis 2012; 16:e94–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]