Abstract

Objective

Neurological and functional impairments are commonly observed in individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) due to insufficient regeneration of damaged axons. Exosomes play a crucial role in the paracrine effects of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and have emerged as a promising therapeutic approach for SCI. Thus, this study aimed to evaluate the safety and potential effects of intrathecal administration of allogeneic exosomes derived from human umbilical cord MSCs (HUC-MSCs) in patients with complete subacute SCI.

Methods

This study was a single-arm, open-label, phase I clinical trial with a 12-month follow-up period. HUC-MSCs were extracted from human umbilical cord tissue, and exosomes were isolated via ultracentrifugation. After intrathecal injection, each participant a underwent complete evaluation, including neurological assessment using the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) scale, functional assessment using the Spinal Cord Independence Measure (SCIM-III), neurogenic bowel dysfunction (NBD) assessment using the NBD score, modified Ashworth scale (MAS), and lower urinary tract function questionnaire.

Results

Nine patients with complete subacute SCI were recruited. The intrathecal injection of allogeneic HUC-MSCs-exosomes was safe and well tolerated. No early or late adverse event (AE) attributable to the study intervention was observed. Significant improvements in ASIA pinprick (P-value = 0.039) and light touch (P-value = 0.038) scores, SCIM III total score (P-value = 0.027), and NBD score (P-value = 0.042) were also observed at 12-month after the injection compared with baseline.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that intrathecal administration of allogeneic HUC-MSCs-exosomes is safe in patients with subacute SCI. Moreover, it seems that this therapy might be associated with potential clinical and functional improvements in these patients. In this regard, future larger phase II/III clinical trials with adequate power are highly required.

Trial registration

Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials, IRCT20200502047277N1. Registered 2 October 2020, https://en.irct.ir/trial/48765.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13287-024-03868-0.

Keywords: Spinal cord injury, Exosomes, Mesenchymal stem cells, Neuroprotection

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a catastrophic medical condition with an age-standardized incidence rate of 13 per 100,000 individuals. Various conditions, such as vertebral fracture or dislocation could lead to compression or transection of the spinal cord, which in turn, initiates the pathological process of SCI that progresses through acute, subacute, and chronic phases [1, 2]. In the acute phase, local injury leads to edema, necrosis, and immune cell infiltration due mainly to blood-spinal cord barrier disruption. The subacute phase of SCI commences with apoptosis as well as axonal demyelination and the formation of an astrocytic border around the injury site [3, 4]. As the damage advances to the chronic phase, cell death leads to the creation of cystic cavities enclosed by an astrocytic border. These cavities as well as the astrocytic border significantly restrict the axonal regeneration. Hence, therapeutic strategies targeting the acute or subacute phase could prevent late changes observed in the chronic phase, such as apoptosis or the development of cystic cavities in SCI patients [5, 6].

Recent studies have demonstrated promising results in terms of impeding the degeneration process in SCI following the transplantation of MSCs [7]. As multipotent stem cells, MSCs could serve as suitable options for cell therapy in SCI, given their regenerative and immunomodulatory effects [8]. Moreover, MSCs could exert significant neuroprotective, anti-gliotic, anti-inflammatory, and angiogenic impacts in SCI by releasing various molecular agents [9–11]. Among different sources of MSCs, human umbilical cord MSCs (HUC-MSCs) have been a viable option for stem cell therapy, given their low immunogenicity. Further, prior investigations have shown that HUC-MSCs could significantly improve neurological function in animal models of SCI [12, 13].

Recent evidence, however, suggests that the aforementioned supportive effects are mostly attributable to the MSC secretome, in lieu of direct impact of cells, such as multi-lineage differentiation [14]. Exosomes, as part of the MSC secretome, are small endosomal vesicles with a diameter ranging from 40 to 160 nanometers and carry various molecules, such as miRNA, mRNA, peptides, proteins, cytokines, and lipids. These extracellular vesicles play a crucial role in tissue regeneration and cellular communication [15–17]. Many previous animal studies have shown that exosomes derived from various cellular sources have neuroprotective and regenerative effects on SCI [18]. It seems that MSC-derived exosome therapy might be more effective than MSC transplantation. In this regard, exosome therapy offers several benefits over MSCs, such as greater stability, targeted delivery, lower immunogenicity, and enhanced reparative capabilities [19]. Moreover, it does not have a number of drawbacks associated with MSC use, such as cell senescence following in vitro expansion or unintended cell differentiation and/or proliferation [20].

Despite promising preclinical findings, no clinical trial has investigated the use of allogeneic MSC-derived exosomes in SCI patients thus far. Therefore, this phase I clinical trial was designed to investigate the safety and potential efficacy of intrathecal administration of allogeneic HUC-MSC-derived exosomes in patients with subacute complete SCI for the first time.

Methods

Study design and participants

This study was a non-randomized, open-label, single-arm phase I clinical trial designed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The current study was approved by the institutional review board of Shohada Tajrish hospital as well as the ethics committees of Tarbiat Modares University and Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (IR.SBMU.MSP.REC.1399.235). In addition, the present clinical trial was registered at the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT20200502047277N1). All patients with subacute SCI who were referred to the neurosurgery department of Shohada Tajrish hospital between October 2020 to November 2021 were screened for eligibility. All participants were fully informed about the experimental process of the study, unpredicted outcomes, and potential adverse events (AEs). Following that, all participants signed the informed consent form before enrollment in the study and performing any intervention. For further improvement in the reporting quality, the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines were followed in the present investigation.

Study inclusion criteria were: (1) Complete SCI compatible with the American spinal injury association (ASIA) Impairment Scale (AIS) grade A; (2) Age between 18 and 60 years; (3) Signed informed consent form; (4) Between two weeks and six months elapsed since the injury. Exclusion criteria were: (1) Other spinal diseases (herniated disk, spinal stenosis, tethered cord syndrome); (2) Intracranial conditions (mass lesions, cerebral edema, hydrocephalus); (3) Neurodegenerative and movement disorders; (4) Severe comorbidities (diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease); (5) History of any surgeries affecting the results (augmentation cystoplasty, duraplasty, colectomy); (6) Active infections; (7) Bone disorders (osteoporosis, osteopenia); (8) Immunological disorders (autoimmune diseases, immunodeficiency); (9) Psychiatric disorders (major depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia).

HUC-MSC isolation and characterization

The research protocols of Shohada Tajrish hospital were followed for the collection of human umbilical cords. Immediately after cesarean delivery, the umbilical cords were transferred to a clean room specifically designed for manufacturing cell therapy products, under completely sterile conditions. The stem cell extraction process was initiated afterward. The use of human umbilical cord samples was approved by the aforementioned ethics committees. Written informed consent was also obtained before sampling from donors. Pieces of cord tissue were placed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, USA). Once blood clots and vessels were removed, the tissue was repeatedly washed with PBS and cut into small portions mechanically afterwards. After that, 3 mL of fragmented tissue, as well as 1 mL of collagenase type IV (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), were added to a 15 mL centrifuge tube. The sample was then incubated at 37 °C with agitation for 90 min until complete tissue digestion. Shaking was performed for 10 min, and centrifugation was carried out at 1250 rpm for 5 min. After removing the supernatant, samples were transferred to a T75 flask containing DMEM/F12 (Gibco, USA), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, USA), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin for 3 to 5 days (5% CO2 and 37 °C). The cells were observed and passaged based on their growth every day thereafter. In the third passage, using flow cytometry surface markers, including CD29, CD105, CD90, CD73, CD45, and CD34 were characterized. The HUC-MSC multipotency was assessed by evaluating adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation capacities.

HUC-MSC-exosome isolation and characterization

For exosome extraction, in the third passage with about 80% confluence, HUC-MSCs were washed with PBS. Incubation was then performed in a serum-free culture medium (at 37 °C, 5% CO2, and 90% humidity) for 72 h. After collecting the conditioned medium from all flasks, centrifugation was first performed at 300×g, (at 4 °C and for 10 min) for cell removal, and then at 2000×g (at 4 °C and for 10 min) and 10,000×g for 30 min for dead cell and cell debris removal, respectively. After that, the supernatant was collected and passed through a 0.22 μm filter. Ultracentrifugation was performed subsequently at 100,000 × g (at 4 °C and for 90 min). The supernatant was then discarded and loaded with 5 mL of PBS. Ultracentrifugation was performed thereafter at 100,000 × g (at 4 °C and for 90 min). Purified exosomes were finally collected and dissolved in 500 µl of isotonic serum. Exosomes were then stored at -80 °C for further studies. Quantification of exosomes was performed using the Micro BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) for determining the total protein concentration of the exosome preparation. This assay measures protein concentration, which correlates with the amount of exosomes, as they are rich in proteins. The dose for intrathecal administration was set at 300 µg of total exosomal protein per patient. The total protein content was used as an index for exosome quantity to ensure consistent dosing. For size distribution measurement, dynamic light scattering (DLS) was implemented via Zetasizer 3000-HA (Malvern Instruments, UK). In addition, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed to evaluate the exosome shape and morphology using a Zeiss EM10C transmission electron microscope (Zeiss, Germany). Further, Western blot was used to detect CD81 (RRID: AB_10618892), CD9 (RRID: AB_377219) as exosome surface markers. Regarding this, RIPA buffer and protease inhibitor were used for exosome lysis. Proteins were transferred to 0.45 μm PVDF membranes at room temperature for 2 h, following SDS-PAGE electrophoresis. After washing the PVDF membranes with TBST, overnight incubation with primary antibodies was performed at 4 °C. Following that, PVDF membranes were washed with TBST three times. Incubation was then performed with the secondary antibody for 2 h at room temperature. Enhanced electrochemiluminescence was then used to detect blots.

Procedures

After enrollment, patients were hospitalized for the study intervention, which was intrathecal injection of allogeneic HUC-MSC-exosomes. Following the hospitalization, patients underwent thorough physical examination, and complete laboratory investigations were carried out to screen for any potential infection or comorbid condition. After that, patients were admitted to the operating room for the intrathecal injection of 300 µg of total protein of exosome precipitated in 5 mL of PBS (60 µg/mL). The injection was carried out in the operating room through a lumbar puncture with a 24 G spinal needle at L4/L5 levels. The intrathecal injection was started and slowly preceded after confirming the entrance of the spinal needle to the arachnoid space. The needle was not withdrawn for 1 min to diminish the risk of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage.

All patients in the study received surgical decompression and vertebral fixation within the first 24–36 h post-injury. No additional surgical or pharmacological interventions were administered following the exosome injection. During both the subacute and chronic phases of SCI (before and after the exosome injection), patients underwent standard rehabilitation therapy. This included physical, occupational, and neuromuscular re-education therapy. Patients attended regular therapy sessions, typically several times per week, with the frequency and intensity tailored to individual needs and progress. These sessions were monitored and adjusted by a physical therapist to ensure optimal outcomes.

Follow-up and outcome measures

Following the injection of allogeneic HUC-MSC-exosomes, patients were followed up for 12 months after the study intervention. The primary outcome measure of the study was the safety profile and incidence of potential adverse events (AEs) after the intrathecal administration of allogeneic HUC-MSC-exosomes. For safety monitoring, patients underwent complete assessments, including thorough physical examination, complete laboratory evaluations, and electrocardiography. All the aforementioned measures were taken at baseline, weekly after the injection until one month, and monthly afterward until the 3-month follow-up. Additionally, after injection and before discharge, all patients were educated on the potential complications, AEs, or safety concerns. Regular phone calls were also made on a weekly basis, and patients were contacted during the study period. Moreover, patients were monitored in terms of safety outcomes and underwent complete evaluations 6 and 12 months after the injection. All AEs were graded and reported according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5.0. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was also performed 6 months after the injection to evaluate potential anatomical complications after the study intervention.

In addition to safety, potential clinical and functional effects of intrathecal allogeneic HUC-MSC-exosome administration were investigated in this study. Hence, patients were evaluated in terms of secondary outcome measures at baseline, 6, and 12 months after the intrathecal injection. Secondary outcome measures included ASIA (sensory and motor scores), Spinal Cord Independence Measure version III (SCIM III - total score as well as self-care, mobility, and respiratory and sphincter management subscale scores), neurogenic bowel dysfunction (NBD) score, modified Ashworth scale (MAS), and urinary tract questionnaire to assess potential clinical and functional changes during the study period [21–24].

Statistical analyses

All the quantitative data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). All the qualitative data were expressed as frequency with percentage. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare continuous data between the baseline and each study time point after the injection. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant in the present study. All the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 24 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

HUC-MSC cell and exosome characterization

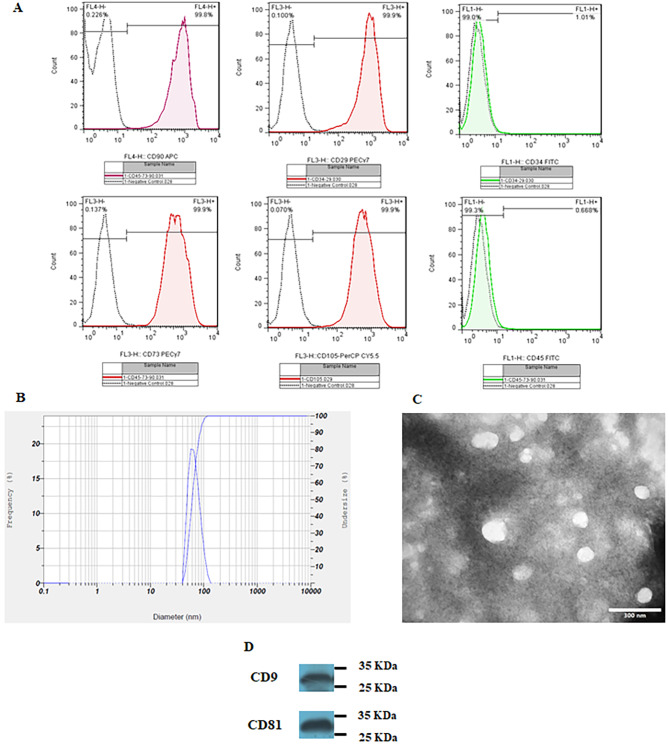

Flow cytometric analysis demonstrated positive expression of CD29 (99.9%), CD73 (99.9%), CD90 (99.8%), and CD105 (99.9%), while concurrently revealing negative expression for CD34 (1.01%) and CD 45 (0.668%) markers in HUC-MSCs (Fig. 1A). The multipotency of HUC-MSCs was confirmed through osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation.

Fig. 1.

(A) Flow cytometric analysis revealed positive expression of CD29, CD73, CD90, and CD105, while indicating negative expression for CD34 and CD 45 markers in HUC-MSCs. (B) The size distribution of exosomes was determined through dynamic light scattering analysis; Mean 63.2 nm, SD: 15.2 nm. (C) Transmission electron microscopy images illustrate the structural features of exosomes. (D) Western blot analysis indicated the expression of exosomal surface markers, including CD9 and CD81 (additional file 1: uncropped blots)

The DLS technique was performed to evaluate the size distribution of HUC-MSC-exosomes, and 1 mL of the prepared sample was used for this purpose. Size distribution assessment demonstrated that HUC-MSC-exosomes had a mean size of 63.2 nm with a standard deviation of 15.2 (Fig. 1B). TEM demonstrated the round morphology of the vesicles suggesting exosomes (Fig. 1C). Moreover, western blot also confirmed the presence of exosome markers, including CD9 and CD8 (Fig. 1D; additional file 1: uncropped blots).

Patient characteristics

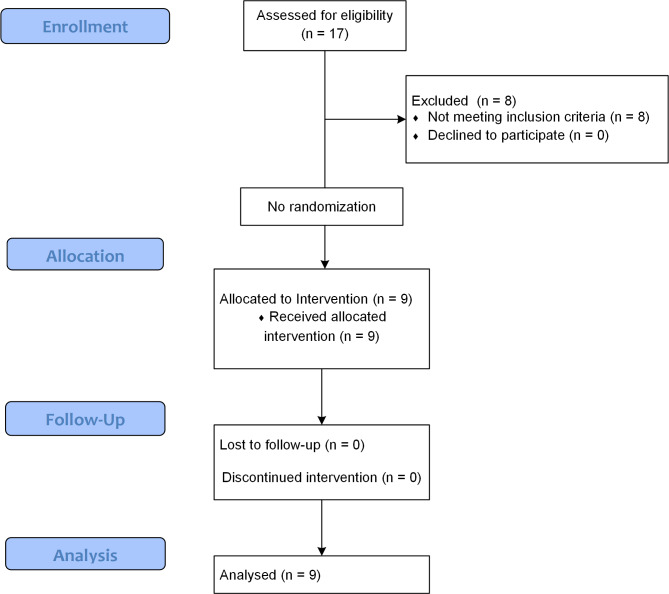

Seventeen patients with complete subacute SCI were screened between 16 October 2020 and 20 November 2021. Among them, 9 patients met the study criteria and were included in the present study. This study included 5 (55.6%) males and 4 (44.4%) females. Participants had a mean age of 33.56 ± 7.62. The mean time elapsed since the injury was 2.78 ± 1.33 months in this investigation. A total of 6 patients had a thoracic level of injury (66.7%) in this study. The most common cause of injury was an accident in this study, which had occurred in 7 patients (77.8%). Table 1 demonstrates the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of each of the included patients. Figure 2 demonstrates the study CONSORT flow diagram.

Table 1.

Patients’ baseline demographic and clinical characteristics

| Patient number | Sex | Age (years) | Cause of injury | LOI | Interval between injection and trauma (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 32 | Accident | T12 | 2 |

| 2 | Male | 28 | Accident | T6 | 4 |

| 3 | Female | 44 | Accident | C5 | 2 |

| 4 | Male | 21 | Falling | T11 | 3 |

| 5 | Female | 36 | Accident | T10 | 3 |

| 6 | Male | 34 | Accident | C6 | 1 |

| 7 | Male | 39 | Falling | C5 | 5.5 |

| 8 | Female | 26 | Accident | T12 | 2 |

| 9 | Female | 42 | Accident | T4 | 2.5 |

LOI: Level of injury

Fig. 2.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2010 flow diagram

Primary outcome measure

Over the 12-month study period, 7 AEs were found in five (55.6%) patients. All the reported AEs were evaluated by the medical safety committee regarding their grade (based on CTCAE version 5), causality, and need for medical intervention. Among all the observed AEs, five (71.4%) were grade I and two (28.6%) were grade II in the present study. Among these seven AEs, four (57.1%) were not related, and three (42.9%) were unlikely related to the study intervention. Therefore, none of the observed AEs were related to the intrathecal injection of exosomes. Table 2 illustrates different characteristics of the observed AEs in this study.

Table 2.

Adverse events according to Common Terminology Criteria for adverse events (CTCAE).

| Pt. | System organ class | Preferred Terms | Number of AE (% respect to number of AE per patient) | Causal link with exosome administration | Degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | General disorders and administration site conditions | Fatigue | 1 (100.00%) | Unlikely | Grade I |

| 2 | Nervous system disorders | Headache | 1 (50.00%) | Not related | Grade II |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | Nausea | 1 (50.00%) | Not related | Grade II | |

| 5 | Nervous system disorders | Headache | 1 (100.00%) | Not related | Grade I |

| 7 | Gastrointestinal disorders | Nausea | 1 (50.00%) | Not related | Grade I |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | Fatigue | 1 (50.00%) | Unlikely | Grade I | |

| 8 | General disorders and administration site conditions | Fatigue | 1 (100.00%) | Unlikely | Grade I |

AE: Adverse event

Secondary outcome measures

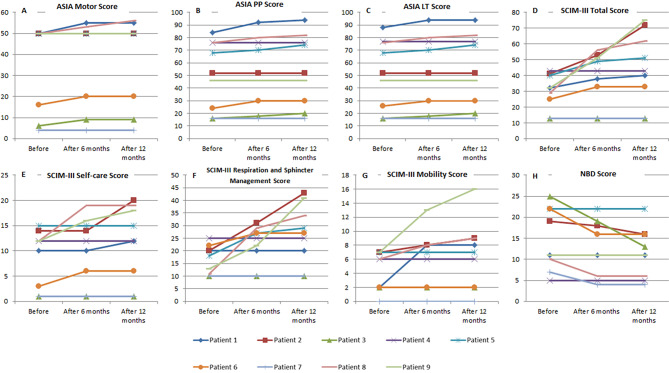

In terms of motor improvement, a total of 4 patients demonstrated recovery over the study period based on ASIA motor score (Fig. 3). Mean ASIA motor scores in the overall study population also demonstrated an increase at 6- (37.89 ± 20.65, p = 0.066) and 12-month (38.22 ± 20.95, p = 0.066) after the intrathecal injection in comparison with the baseline (36.22 ± 20.92), yet it was not statistically significant. In addition, significant changes were observed in ASIA sensory scores in patients. The mean ASIA sensory light touch score showed significant improvement at 6- (53.67 ± 28.38, p = 0.041) and 12-month (54.56 ± 28.62, p = 0.038) after the intrathecal injection in comparison with the baseline (51.67 ± 27.51). Similarly, mean ASIA sensory pinprick score significantly improved at the 6- (53.33 ± 27.93, p = 0.042) and 12-month follow-up (54.44 ± 28.53, p = 0.039) compared with the baseline (50.89 ± 27.00). Among participants, the most remarkable changes were noted in patients 1, 3, 5, 6, and 8 as depicted in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Neurological, functional, and neurogenic bowel dysfunction (NBD) changes in the patients over the study period (A-H). Changes of ASIA motor, pinprick, light touch, spinal cord independence measure (SCIM) version III total, self-care, respiration and sphincter management, mobility, and NBD scores in patients at baseline, 6-, and 12-month after the intrathecal injection

With respect to functional outcomes, significant improvements were found in patients over the study period. The SCIM III total score showed significant improvement at the 6- (38.78 ± 16.33, p = 0.028) and 12-month follow-up (44.67 ± 22.84, p = 0.027) after the intrathecal injection in comparison with the baseline (29.78 ± 11.19). Among participants, six demonstrated notable improvements in SCIM III total score (Fig. 3). Similar to SCIM III total score, the self-care and respiratory and sphincter management subscales showed significant improvements over the study period. The mean self-care subscale score significantly improved at 12-month (11.56 ± 7.37, p = 0.042) after the intrathecal injection in comparison with the baseline (8.89 ± 5.62). Likewise, the mean respiratory and sphincter management subscale score showed significant improvement at 12 months (26.56 ± 11.91, p = 0.042) after the intrathecal injection in comparison with the baseline (16.56 ± 5.66). Concerning the mobility subscale, four participants (patients 1, 2, 8, and 9) showed improvements over time, yet the mean score at 12 months (6.56 ± 4.85, p = 0.068) after the intrathecal injection was comparable with the baseline (4.33 ± 2.78). Figure 3 demonstrates changes in SCIM III total and subscale scores in study participants 6 and 12 months after the injection.

Significant changes were also observed in NBD 12 months after the injection, especially in patients 2, 3, 6, 7, and 8. Among them, patients 3, 7, and 8 showed improvements in NBD grades from severe to moderate, minor to very minor, and moderate to very minor, respectively. The mean NBD score of the study population significantly decreased at 6- (12.44 ± 6.62, p = 0.042) and 12-month (11.56 ± 5.94, p = 0.042) after the intrathecal injection in comparison with the baseline (14.67 ± 7.37). Figure 3 illustrates changes in NBD scores over the study period in patients individually.

Changes in the spasticity after the intrathecal injection of allogeneic HUC-MSC-exosomes were also assessed. A total of 6 (66.7%) patients had spasticity at baseline, based on assessments of the hip extensor, knee extensor, knee flexor, and ankle plantar flexor muscle groups. Among 20 spasms in 24 muscle groups, 11 muscle groups experienced recovery. Of them, 3 (15%) showed improvements in spasticity in ankle plantar flexors, 3 (15%) showed improvements in spasticity in knee extensors, 2 (10%) showed improvements in spasticity in knee flexors, and 3 (15%) showed improvements in spasticity in hip extensor muscles. Mean MAS scores of the overall study population for ankle plantar flexors (baseline: 1.22 ± 0.97; 12-month: 0.78 ± 0.97, p = 0.102), knee extensors (baseline: 1.11 ± 1.05; 12-month: 0.8 ± 0.8, p = 0.083), knee flexors (baseline: 0.56 ± 0.73; 12-month: 0.33 ± 0.50, p = 0.157), and hip extensors (baseline: 0.44 ± 0.53; 12-month: 0.11 ± 0.33, p = 0.083) were comparable between the baseline and 12-month after the injection. Table 3 demonstrates changes in MAS scores in patients with SCI-induced spasticity over the study period.

Table 3.

Patients’ modified Ashworth score following injection of exosomes

| knee extensors | knee flexors | Ankle plantar flexors | Hip extensors | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAS | Baseline | 6-month | 12-month | Baseline | 6-month | 12-month | Baseline | 6-month | 12-month | Baseline | 6-month | 12-month |

| Case 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Case 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Case 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Case 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Case 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Case 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Case 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Case 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Case 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

MAS: modified Ashworth score

In addition, changes in lower urinary tract function were evaluated in the present study. The number of urinary incontinence episodes per week showed a reduction at 6- (4.89 ± 1.45, p = 0.059) and 12-month (4.56 ± 1.74, p = 0.066) after the intrathecal injection in comparison with the baseline (5.89 ± 1.27), yet it was not statistically significant. Moreover, patients 1 and 8 reported subjective improvements in bladder filling sensation and bladder voiding ability. Table 4 shows changes in urinary tract function over the study period in the study population.

Table 4.

Changes in urinary function following injection of exosomes

| Baseline | 6-month | 12-month | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary incontinence (number of episodes per week) | 5.89 ± 1.27 | 4.89 ± 1.45 | 4.56 ± 1.74 | |

| Bladder filling sensation | Yes | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| No | 7 | 6 | 5 | |

| Bladder voiding ability | Yes | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| No | 8 | 6 | 6 | |

Discussion

This single-arm phase I clinical trial, for the first time, showed remarkable findings regarding the intrathecal administration of allogeneic HUC-MSC-exosomes in patients with complete subacute SCI. The major finding of this clinical trial was the safety profile of the study intervention, which was the intrathecal administration of allogeneic HUC-MSC-exosomes. Concerning this, no early or late AEs attributable to the intrathecal injection were observed. Moreover, it seems that intrathecal administration of allogeneic HUC-MSC-exosomes could lead to notable improvements in various aspects of SCI, such as sensorimotor function, NBD, and functional status. However, although significant findings were observed, the present investigation mainly aimed to evaluate the safety profile and merely included 9 patients for such purpose, and is underpowered for efficacy evaluations.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first trial to provide clinical data on intrathecal administration of allogeneic exosomes in patients with complete SCI. The entire group showed a significant improvement in ASIA sensory scores for light touch and pinprick, as well as ASIA motor recovery in four patients. Additionally, during the one-year follow-up after treatment with allogeneic HUC-MSCs-exosomes, there was a significant improvement in the SCIM-III total score and subscales for self-care, respiratory, and sphincter management. Although the improvement in NBD score was statistically significant, patients also reported non-significant improvements in bladder filling sensation, voiding ability, urinary incontinence, and lower limb muscular spasticity. Numerous clinical trials have been conducted to assess MSC effects on SCI. Abo El-kheir et al. investigated the use of autologous bone marrow-derived cell therapy in chronic SCI and observed significant improvements in motor, pinprick, and light touch ASIA scores, as well as in the functional independence measure in 15 complete SCI subjects [25]. Vaquero J. et al. assessed the efficacy of intrathecal autologous mesenchymal stromal cell injection in nine chronic SCI subjects and observed recovery in ASIA motor, pinprick, and light touch scores during their 10-month follow-up. The SCI functional rating scale of the International Association of Neurorestoratology and its sphincter sub-scale also demonstrated improvement in treated patients. Furthermore, following autologous mesenchymal stromal cell injection, there was a significant increase in NBD score, while a non-significant decrease in MAS was observed [26].

Numerous studies have demonstrated the immense potential of MSCs in protecting the damaged spinal cord from degenerative mechanisms after an injury [27]. MSCs achieve this effect by secreting various factors, among which exosomes are believed to be the primary source of therapeutic benefits due to their ability to promote tissue repair [28]. Exosomes have several distinct advantages that make them powerful therapeutic agents compared to MSCs. Exosomes are protected from the hydrolysis due mainly to their bilayer lipid shield. Moreover, they could evade the phagocytosis and engulfment by lysosomes given their small size [29, 30]. Additionally, adhesion molecules, such as the carbohydrate/lectin receptors, intercellular adhesion molecule, heparan sulfate proteoglycans, and tetraspanins could substantially improve the targeted delivery and uptake of them [31, 32]. Exosomes also have a significantly lower potential for carcinogenicity, lower immune rejection, and ease of acquisition, storage, and transport through the blood-brain barrier in comparison with MSCs [33–36].

SCI is a complex condition with a multifaceted pathophysiology that can be divided into primary and secondary injuries [37]. Primary injury occurs due to a sudden impact, leading to fractures and displacements of vertebrae, which in turn cause bone fragments, ligament ruptures, nerve parenchyma destruction, axonal damage, haemorrhage, and disruption of glial membranes [38]. Secondary injury is characterized by a cascade of responses triggered by the initial damage, including elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines, reactive oxygen species, oxidative stress, excitatory amino acids, such as glutamate, disrupted ion homeostasis, mitochondrial dysfunction, and cell death [39]. The primary factors contributing to the secondary damage after SCI are apoptosis and inflammation. [40].

SCI leads to disruption of the blood-brain barrier, which facilitates the rapid infiltration of neutrophils and M1 macrophages from the bloodstream into the damaged spinal cord tissue, resulting in the release of various inflammatory mediators, such as IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β [41, 42]. Heightened TNF-α and IL-1β levels during the initial stages of SCI instigate an inflammatory response that triggers neuronal apoptosis, demyelination, astrocyte toxicity, oligodendrocyte death, and excitotoxicity [3]. Conversely, M2 macrophages balance the inflammatory immune response by generating cytokines, such as IL-4 and IL-10 [43, 44]. IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine, significantly suppresses TNF-α production by astrocytes as well as antigen presentation by both astrocytes and microglia, leading to marked improvements in functional recovery after SCI [45, 46].

Exosomes derived from MSCs (MSC-exosomes) exhibit potent anti-inflammatory properties by reducing levels of proinflammatory factors, such as TNF-α and Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B (NF-κB). This reduction leads to decreased activation of A1 astrocytes. Treatment with MSC-exosomes inhibits the nuclear translocation of the NF-κB p65 subunit, thereby lowering the expression of TNF-α, Interleukin (IL)-1α, and IL-1β while simultaneously increasing anti-inflammatory cytokines. This regulatory action results in smaller lesion areas and improved motor function, as evidenced by higher blood-brain barrier (BBB) scores [47]. Additionally, MSC-exosomes diminish the polarization of macrophages to the M1 phenotype, induced by reactive oxygen species (ROS), through the MAPK-NFκB P65 signaling pathway. By breaking the cycle between ROS production and M1 macrophage activation, these exosomes help reducing the secondary damage and inflammation following SCI, showcasing their potential in mitigating ROS-related damage [48].

Moreover, MSC-exosomes play a vital role in preserving the integrity of the blood-spinal cord barrier (BSCB). They prevent damage to BSCB permeability and promote natural repair processes by regulating tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinase 2 (TIMP2). TIMP2 in these exosomes inhibits the MMP pathway, preserving cell junction proteins and minimizing damage. Knockout studies using siTIMP2 underscore the crucial role of TIMP2 in the efficacy of MSC-exosomes, confirming their importance in maintaining BSCB integrity and enhancing functional recovery after SCI [49].

In addition to the inflammatory response, the extent of apoptosis significantly affects functional recovery, making it a critical factor for axonal regeneration [40]. Apoptosis is primarily regulated by the Bcl-2 and caspase families, acting upstream and downstream in the process, respectively. The pro-apoptotic (BAX) or anti-apoptotic (Bcl-2) molecules significantly influence the functional recovery after SCI [50, 51]. Previous studies have indicated that SCI upregulates BAX expression while inhibiting the expression levels of Bcl-2 [52, 53]. Animal experiments have demonstrated that exosome treatment substantially reduces the expression levels of apoptotic proteins (BAX) when compared to the control group. Furthermore, exosomes cause a significant increase in the level of anti-apoptotic protein (Bcl-2), demonstrating their neuroprotective effect against SCI-induced neuronal apoptosis [54]. Prior studies have indicated that exosomes of bone marrow-derived MSCs significantly reduce lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced apoptosis. They achieve this by decreasing the levels of pro-apoptotic factors (e.g., TNF-α and IL-1β) while increasing the release of anti-apoptotic cytokines (e.g., IL-10 and IL-4). This effect is facilitated by the downregulation of myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88), toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), and NF-κB, underscoring their potential in reducing cell death and inflammation [55]. This neuroprotective action promotes better recovery of sensory and motor functions by preventing secondary damage and supporting neuron survival. [47, 55].

Although the present clinical trial had remarkable strengths, there were some limitations. First, this investigation was performed in one institution, and all SCI patients received similar care with the same protocol. Thus, future multicenter studies are highly needed to evaluate the effects of this therapy in different care settings. Second, the present study was not adequately powered to evaluate the efficacy of intrathecal injection of allogeneic HUC-MSC-exosomes as it primarily aimed to assess the safety profile of this intervention. In acute and subacute phase SCI trials, neural regeneration is influenced by various factors, especially during the critical period for neurological improvements within the first 1–2 years post-injury. We recognize the concern that patients with SCI might naturally experience sensory and motor function improvements during this time, complicating the attribution of observed changes to the experimental intervention. The influence of this factor on our results is unavoidable and limits our conclusions. Therefore, we recommend future phase II/III investigations including larger sample sizes with control groups to obtain more definitive and conclusive results. Third, only patients with subacute complete SCI were included in this clinical trial. Accordingly, the potential effects of this treatment on patients with acute or chronic and those with incomplete injuries are yet to be evaluated. Fourth, the follow-up period in this study was 12 months. Future studies with longer follow-up periods could investigate the potential long-term impacts of intrathecal injection of allogeneic HUC-MSC-exosomes in SCI patients.

Conclusions

This phase I clinical trial demonstrated that intrathecal injection of allogeneic HUC-MSC-exosomes in patients with subacute SCI is safe and tolerable with no early or late AE. Moreover, it seems that exosome therapy in subacute SCI is potentially associated with improvements in different aspects of SCI, such as sensorimotor function, functional status (self-care as well as respiratory and sphincter management), and NBD. However, the present phase I clinical trial was not adequately powered to evaluate the efficacy of intrathecal injection of allogeneic HUC-MSC-exosomes. Therefore, future larger phase II clinical trials are required to assess the efficacy of this novel therapeutic strategy in SCI patients.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Additional file 1: Uncropped blots of western blot analysis indicated the expression of exosomal surface markers, including CD9 and CD81.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

MA: Writing manuscript and investigation; RT: Writing manuscript and investigation; MH: Writing manuscript, clinical and experimental collaboration; KO: Clinical collaboration and manuscript editing; AS: Investigation; MY: Clinical supervision, MS: Experimental supervision, MC: Manuscript editing and data gathering, MG: Experimental collaboration, AZ: Supervision, RH: Experimental supervision and laboratory procedures, SO: Clinical supervision and investigation.

Funding

This study is funded by Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

Data availability

The datasets generated are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study has been approved by the Research Ethics Committees of School of Medicine - Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (Ethics code: IR.SBMU.MSP.REC.1399.235) with the title of “Safety and Efficacy Assessment of Combination of Artificial Dura and Umbilical Cord and Placenta Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes in Patients with Acute, Subacute and Chronic Complete Spinal Cord Injury: A Single-blinded Controlled Clinical Trial” on 2020-09-01. Informed consent form of the study has been reviewed by the mentioned ethics committee and the patient signed it before intervention.

Consent for publication

The informed consent form also had included the patient’s permission to the publication of an article containing all data and images could be published.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests .

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Mohammadhosein Akhlaghpasand and Roozbeh Tavanaei contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Reza Heidari, Email: r-heidary@ajaums.ac.ir.

Saeed Oraee-Yazdani, Email: saeed.o.yazdani@gmail.com.

References

- 1.David G, Mohammadi S, Martin AR, Cohen-Adad J, Weiskopf N, Thompson A, Freund P. Traumatic and nontraumatic spinal cord injury: pathological insights from neuroimaging. Nat Reviews Neurol. 2019;15(12):718–31. 10.1038/s41582-019-0270-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.James SL, Theadom A, Ellenbogen RG, Bannick MS, Montjoy-Venning W, Lucchesi LR, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(1):56–87. 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30415-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahuja CS, Wilson JR, Nori S, Kotter M, Druschel C, Curt A, Fehlings MG. Traumatic spinal cord injury. Nat Reviews Disease Primers. 2017;3(1):1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayta E, Elden H. Acute spinal cord injury: a review of pathophysiology and potential of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for pharmacological intervention. J Chem Neuroanat. 2018;87:25–31. 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2017.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradbury EJ, Burnside ER. Moving beyond the glial scar for spinal cord repair. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):3879. 10.1038/s41467-019-11707-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dalamagkas K, Tsintou M, Seifalian A, Seifalian AM. Translational regenerative therapies for chronic spinal cord injury. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(6):1776. 10.3390/ijms19061776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tashiro S, Tsuji O, Shinozaki M, Shibata T, Yoshida T, Tomioka Y, et al. Current progress of rehabilitative strategies in stem cell therapy for spinal cord injury: a review. NPJ Regenerative Med. 2021;6(1):81. 10.1038/s41536-021-00191-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liau LL, Looi QH, Chia WC, Subramaniam T, Ng MH, Law JX. Treatment of spinal cord injury with mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Bioscience. 2020;10(1):1–17. 10.1186/s13578-020-00475-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rehman J, Traktuev D, Li J, Merfeld-Clauss S, Temm-Grove CJ, Bovenkerk JE, et al. Secretion of angiogenic and antiapoptotic factors by human adipose stromal cells. Circulation. 2004;109(10):1292–8. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121425.42966.F1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uccelli A, Moretta L, Pistoia V. Mesenchymal stem cells in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(9):726–36. 10.1038/nri2395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hofer HR, Tuan RS. Secreted trophic factors of mesenchymal stem cells support neurovascular and musculoskeletal therapies. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2016;7:1–14. 10.1186/s13287-016-0394-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun G, Li G, Li D, Huang W, Zhang R, Zhang H, et al. hucMSC derived exosomes promote functional recovery in spinal cord injury mice via attenuating inflammation. Mater Sci Engineering: C. 2018;89:194–204. 10.1016/j.msec.2018.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang J, Guo Y. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells derived exosomes promote neurological function recovery in a rat spinal cord Injury Model. Neurochem Res. 2022;47(6):1532–40. 10.1007/s11064-022-03545-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ren Z, Qi Y, Sun S, Tao Y, Shi R. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes: hope for spinal cord injury repair. Stem Cells Dev. 2020;29(23):1467–78. 10.1089/scd.2020.0133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalluri R, LeBleu VS. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science. 2020;367(6478):eaau6977. 10.1126/science.aau6977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He C, Zheng S, Luo Y, Wang B. Exosome theranostics: biology and translational medicine. Theranostics. 2018;8(1):237. 10.7150/thno.21945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shafei S, Khanmohammadi M, Heidari R, Ghanbari H, Taghdiri Nooshabadi V, Farzamfar S, et al. Exosome loaded alginate hydrogel promotes tissue regeneration in full-thickness skin wounds: an in vivo study. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2020;108(3):545–56. 10.1002/jbm.a.36835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yi H, Wang Y. A meta-analysis of exosome in the treatment of spinal cord injury. Open Med. 2021;16(1):1043–60. 10.1515/med-2021-0304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nikfarjam S, Rezaie J, Zolbanin NM, Jafari R. Mesenchymal stem cell derived-exosomes: a modern approach in translational medicine. J Translational Med. 2020;18(1):1–21. 10.1186/s12967-020-02622-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herberts CA, Kwa MS, Hermsen HP. Risk factors in the development of stem cell therapy. J Translational Med. 2011;9:1–14. 10.1186/1479-5876-9-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El Masry WS, Tsubo M, Katoh S, El Miligui YH, Khan A. Validation of the American spinal injury association (ASIA) motor score and the national acute spinal cord injury study (NASCIS) motor score. Spine. 1996;21(5):614–9. 10.1097/00007632-199603010-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Itzkovich M, Gelernter I, Biering-Sorensen F, Weeks C, Laramee M, Craven B, et al. The spinal cord independence measure (SCIM) version III: reliability and validity in a multi-center international study. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29(24):1926–33. 10.1080/09638280601046302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krogh K, Christensen P, Sabroe S, Laurberg S. Neurogenic bowel dysfunction score. Spinal Cord. 2006;44(10):625–31. 10.1038/sj.sc.3101887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akpinar P, Atici A, Ozkan F, Aktas I, Kulcu D, Sarı A, Durmus B. Reliability of the Modified Ashworth Scale and Modified Tardieu Scale in patients with spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord. 2017;55(10):944–9. 10.1038/sc.2017.48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El-Kheir WA, Gabr H, Awad MR, Ghannam O, Barakat Y, Farghali HA, et al. Autologous bone marrow-derived cell therapy combined with physical therapy induces functional improvement in chronic spinal cord injury patients. Cell Transplant. 2014;23(6):729–45. 10.3727/096368913X664540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vaquero J, Zurita M, Rico MA, Aguayo C, Bonilla C, Marin E, et al. Intrathecal administration of autologous mesenchymal stromal cells for spinal cord injury: safety and efficacy of the 100/3 guideline. Cytotherapy. 2018;20(6):806–19. 10.1016/j.jcyt.2018.03.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cofano F, Boido M, Monticelli M, Zenga F, Ducati A, Vercelli A, Garbossa D. Mesenchymal stem cells for spinal cord injury: current options, limitations, and future of cell therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(11):2698. 10.3390/ijms20112698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yeo RWY, Lai RC, Tan KH, Lim SK. Exosome: a novel and safer therapeutic refinement of mesenchymal stem cell. Exosomes Microvesicles. 2013;1:7. [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Meel R, Fens MH, Vader P, Van Solinge WW, Eniola-Adefeso O, Schiffelers RM. Extracellular vesicles as drug delivery systems: lessons from the liposome field. J Controlled Release. 2014;195:72–85. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.07.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ha D, Yang N, Nadithe V. Exosomes as therapeutic drug carriers and delivery vehicles across biological membranes: current perspectives and future challenges. Acta Pharm Sinica B. 2016;6(4):287–96. 10.1016/j.apsb.2016.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hwang I, Shen X, Sprent J. Direct stimulation of naive T cells by membrane vesicles from antigen-presenting cells: distinct roles for CD54 and B7 molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2003;100(11):6670–5. 10.1073/pnas.1131852100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nazarenko I, Rana S, Baumann A, McAlear J, Hellwig A, Trendelenburg M, et al. Cell surface tetraspanin Tspan8 contributes to Molecular pathways of Exosome-Induced Endothelial Cell ActivationExosome-Induced endothelial cell activation. Cancer Res. 2010;70(4):1668–78. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lener T, Gimona M, Aigner L, Börger V, Buzas E, Camussi G, et al. Applying extracellular vesicles based therapeutics in clinical trials–an ISEV position paper. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4(1):30087. 10.3402/jev.v4.30087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng G, Huang R, Qiu G, Ge M, Wang J, Shu Q, Xu J. Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles: regenerative and immunomodulatory effects and potential applications in sepsis. Cell Tissue Res. 2018;374:1–15. 10.1007/s00441-018-2871-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang C-C, Kang M, Lu Y, Shirazi S, Diaz JI, Cooper LF, et al. Functionally engineered extracellular vesicles improve bone regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2020;109:182–94. 10.1016/j.actbio.2020.04.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bari E, Perteghella S, Di Silvestre D, Sorlini M, Catenacci L, Sorrenti M, et al. Pilot production of mesenchymal stem/stromal freeze-dried secretome for cell-free regenerative nanomedicine: a validated GMP-compliant process. Cells. 2018;7(11):190. 10.3390/cells7110190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khorasanizadeh M, Yousefifard M, Eskian M, Lu Y, Chalangari M, Harrop JS, et al. Neurological recovery following traumatic spinal cord injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurosurgery: Spine. 2019;30(5):683–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu Y, Soderblom C, Krishnan V, Ashbaugh J, Bethea J, Lee J. Hematogenous macrophage depletion reduces the fibrotic scar and increases axonal growth after spinal cord injury. Neurobiol Dis. 2015;74:114–25. 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.10.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu GJ, Nagarajah R, Banati RB, Bennett MR. Glutamate induces directed chemotaxis of microglia. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29(6):1108–18. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06659.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang P, Hou H, Zhang L, Lan X, Mao Z, Liu D, et al. Autophagy reduces neuronal damage and promotes locomotor recovery via inhibition of apoptosis after spinal cord injury in rats. Mol Neurobiol. 2014;49:276–87. 10.1007/s12035-013-8518-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bellora F, Castriconi R, Dondero A, Reggiardo G, Moretta L, Mantovani A et al. The interaction of human natural killer cells with either unpolarized or polarized macrophages results in different functional outcomes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107(50):21659-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Brown G. Mechanisms of inflammatory neurodegeneration: iNOS and NADPH oxidase. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35(5):1119–21. 10.1042/BST0351119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kigerl KA, Gensel JC, Ankeny DP, Alexander JK, Donnelly DJ, Popovich PG. Identification of two distinct macrophage subsets with divergent effects causing either neurotoxicity or regeneration in the injured mouse spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2009;29(43):13435–44. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3257-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mantovani A, Sica A, Sozzani S, Allavena P, Vecchi A, Locati M. The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol. 2004;25(12):677–86. 10.1016/j.it.2004.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brewer KL, Bethea JR, Yezierski RP. Neuroprotective effects of interleukin-10 following excitotoxic spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 1999;159(2):484–93. 10.1006/exnr.1999.7173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.BETHEA JR, NAGASHIMA H, ACOSTA MC, BRICENO C, GOMEZ F, MARCILLO AE, et al. Systemically administered interleukin-10 reduces tumor necrosis factor-alpha production and significantly improves functional recovery following traumatic spinal cord injury in rats. J Neurotrauma. 1999;16(10):851–63. 10.1089/neu.1999.16.851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang L, Pei S, Han L, Guo B, Li Y, Duan R, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes reduce A1 astrocytes via downregulation of phosphorylated NFκB P65 subunit in spinal cord injury. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;50(4):1535–59. 10.1159/000494652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu C, Hu F, Jiao G, Guo Y, Zhou P, Zhang Y, et al. Dental pulp stem cell-derived exosomes suppress M1 macrophage polarization through the ROS-MAPK-NFκB P65 signaling pathway after spinal cord injury. J Nanobiotechnol. 2022;20(1):65. 10.1186/s12951-022-01273-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xin W, Qiang S, Jianing D, Jiaming L, Fangqi L, Bin C, et al. Human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell–derived exosomes attenuate blood–spinal cord barrier disruption via the TIMP2/MMP pathway after acute spinal cord injury. Mol Neurobiol. 2021;58:6490–504. 10.1007/s12035-021-02565-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang J-H, Yin X-M, Xu Y, Xu C-C, Lin X, Ye F-B, et al. Systemic administration of exosomes released from mesenchymal stromal cells attenuates apoptosis, inflammation, and promotes angiogenesis after spinal cord injury in rats. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34(24):3388–96. 10.1089/neu.2017.5063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang J, Cui Z, Feng G, Bao G, Xu G, Sun Y, et al. RBM5 and p53 expression after rat spinal cord injury: implications for neuronal apoptosis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2015;60:43–52. 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lin C-L, Wang J-Y, Huang Y-T, Kuo Y-H, Surendran K, Wang F-S. Wnt/β-catenin signaling modulates survival of high glucose–stressed mesangial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(10):2812–20. 10.1681/ASN.2005121355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Adams JM, Cory S. The Bcl-2 protein family: arbiters of cell survival. Science. 1998;281(5381):1322–6. 10.1126/science.281.5381.1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen J, Zhang C, Li S, Li Z, Lai X, Xia Q. Exosomes derived from nerve stem cells loaded with FTY720 promote the recovery after spinal cord injury in rats by PTEN/AKT signal pathway. Journal of Immunology Research. 2021;2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Fan L, Dong J, He X, Zhang C, Zhang T. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes reduce apoptosis and inflammatory response during spinal cord injury by inhibiting the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2021;40(10):1612–23. 10.1177/09603271211003311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Uncropped blots of western blot analysis indicated the expression of exosomal surface markers, including CD9 and CD81.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.