Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to investigate the characteristics and related functional pathways of the gut microbiota in patients with IgA nephropathy (IgAN) through metagenomic sequencing technology.

Methods

We enrolled individuals with primary IgAN, including patients with normal and abnormal renal function. Additionally, we recruited healthy volunteers as the healthy control group. Stool samples were collected, and species and functional annotation were performed through fecal metagenome sequencing. We employed linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) analysis to identify significantly different bacterial microbiota and functional pathways. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis was used to annotate microbiota functions, and redundancy analysis (RDA) was performed to analyze the factors affecting the composition and distribution of the gut microbiota.

Results

LEfSe analysis revealed differences in the gut microbiota between IgAN patients and healthy controls. The characteristic microorganisms in the IgAN group were classified as Escherichia coli, with a significantly greater abundance than that in the healthy control group (p < 0.05). The characteristic microorganisms in the IgAN group with abnormal renal function were identified as Enterococcaceae, Moraxella, Moraxella, and Acinetobacter. KEGG functional analysis demonstrated that the functional pathways of the microbiota that differed between IgAN patients and healthy controls were related primarily to bile acid metabolism.

Conclusions

The status of the gut microbiota is closely associated not only with the onset of IgAN but also with the renal function of IgAN patients. The characteristic gut microbiota may serve as a promising diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target for IgAN.

Keywords: IgA nephropathy, gut microbiota, metagenomic sequencing, microbial characteristics and functions

Introduction

Immunoglobulin A nephropathy (IgAN) is the most prevalent form of primary glomerular disease globally [1, 2] and ranks among the leading causes of chronic kidney failure and end-stage kidney disease [3]. IgAN presents a notably high degree of heterogeneity, with distinct clinical and pathological manifestations observed among different patients, alongside variations in prognosis [4]. The accurate diagnosis and early prognosis assessment of IgAN have substantial clinical importance.

Currently, the diagnosis of IgAN hinges on renal biopsy pathology, and a pressing need remains for noninvasive diagnostic and typing biomarkers. The pathogenesis of IgAN is intricate, and its exact mechanisms are not fully understood [5]. The ‘four hits’ theory [6] is now widely accepted for understanding the pathogenesis of IgAN. The gut–kidney axis is believed to play a crucial role in both the ‘first hit’, involving galactose-deficient immunoglobulin A1 (Gd-IgA1) formation, and the subsequent ‘second hit’, which includes the production of IgG antibodies against Gd-IgA1. Aberrant intestinal mucosal immunity serves as a pivotal source of IgAN pathogenesis [7]. An imbalance in the gut microbiota can compromise the integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier, leading to intestinal infections. This, in turn, activates gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), promoting the excessive production of Gd-IgA1, which serves as an antigen that continually stimulates immune abnormalities within the intestinal mucosa. Autoantibodies recognize Gd-IgA1 antigens, forming immune complexes that deposit in the glomerular mesangial region. These complexes activate the complement system, inciting inflammatory responses and kidney damage. They induce mesangial cell proliferation, ultimately driving the development of IgAN [8]. Thus, irregularities in intestinal mucosal immunity constitute the foundation of IgAN, with the intestinal microbiota exerting a significant influence on mucosal immune homeostasis. An imbalance in the intestinal microbiota represents a critical link in inducing the production of Gd-IgA1 and is closely related to IgA nephropathy. By examining the specific species, key constituents, and principal functions of the intestinal microbiota, we anticipate that noninvasive methods can be harnessed for IgAN classification, early prognosis prediction, and the identification of new targets for prevention and treatment.

In recent years, research has revealed differences in the abundance, diversity, and metabolic composition of the intestinal microbiota between IgAN patients and healthy individuals [9–17]. Nevertheless, variations in disease severity, treatment regimens, geographic location, race, and sample sizes among IgAN patients have yielded gut microbiota characteristics that are not entirely congruent. Consequently, pinpointing the key major bacteria directly associated with IgAN remains challenging. Moreover, current research predominantly relies on 16S rDNA sequencing technology, primarily focusing on the V4 or V3-V4 regions. This results in sequences that lack species-level annotations and cannot be further explored at the functional level.

The objective of this study was to investigate the role of the gut microbiota in IgAN pathogenesis by examining the differences in the composition and functional profiles of the intestinal microbiota between IgAN patients and healthy individuals. We also examined differences between individuals with renal dysfunction and those with normal renal function within the IgAN patient cohort. To achieve this aim, we employed state-of-the-art high-throughput sequencing technology, specifically metagenomic sequencing.

Methods

Subjects

Patients diagnosed with IgAN via renal biopsy and pathological examination were enrolled from the Department of Nephrology at the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University between January 2021 and December 2021. Healthy volunteers, matched for age and sex with the IgAN group, served as the healthy control group. The IgAN patients were further categorized into normal or abnormal renal function groups, with renal function abnormalities defined as an eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Both patients and healthy controls did not consume medicine or food that may have affected the gut microbiota in the past month. Fecal samples and clinical data of the study subjects were collected, and all patients provided informed consent for B-type ultrasound-guided percutaneous kidney biopsy before the procedure. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University (ethical approval 2016 No. (036)).

The inclusion criteria were as follows: age > 18; renal biopsy diagnosed primary IgAN with immunofluorescence examination revealing the deposition of IgA or IgA-dominated immune complexes in the glomerular mesangial area; complete information and informed consent to retain the specimens; have not used antibiotics, steroids, immunosuppressants, microbial preparations, or foods containing active bacterial ingredients (such as yogurt, lactic acid drinks, probiotic food, etc.) in the past month.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: secondary IgAN (including purpura nephritis, hepatitis B-related nephropathy, tumor-related IgAN, inflammatory bowel disease-related IgAN, etc.); diagnosis of malignant tumors, acute cardiovascular or cerebrovascular diseases, liver cirrhosis, or hyperthyroidism; previous history of gallbladder or intestinal resection or other intestinal diseases; severe infections or complications, or severe psychological or mental illnesses; pregnant or lactating women; significant changes in bowel habits, stool color, appearance, softness, or hardness in the past month; gastroscopy or colonoscopy examination and endoscopic treatment in the past 3 months.

Fecal sample and clinical data collection

Baseline demographic data, including height, weight, age, sex, smoking history, drinking history, and body mass index (BMI), were collected from the study subjects. The laboratory data included 24-h urine protein, blood albumin, blood creatinine, triglyceride, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein, high-density lipoprotein, blood phosphorus, blood calcium, blood uric acid, random urine protein/creatinine, and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). The eGFR was calculated using the 2009 CKD-EPI serum creatinine equation.

Fecal samples were obtained within 3 days of renal biopsy. Fecal samples from healthy controls were obtained within 3 days after the results of the physical examination were reported. Fecal samples (5–8 g) were collected from the study subjects in sterile containers and immediately stored in a −80 °C freezer. Bacterial DNA was isolated from the stool samples using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method. The metagenomic library was constructed via the NEBNext® Ultra™ DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB, USA). Metagenomic sequencing was performed via an Illumina NovaSeq instrument.

Bioinformatics and statistical analysis

The raw data were subjected to quality control and host genome dehosting using KneadData software. Quality control, which included Trimmatic parameters, was performed via FastQC before and after processing. Metagenomic sequencing data were classified using Kraken, and the results from Kraken2 were further analyzed via Bracken to estimate species-level or genus-level abundance. The relative abundance of each species was predicted using Bracken.

Following quality control and host gene removal, sequences were matched with the protein database (UniRef90) via HUMAnN2 software (based on DIAMOND) to calculate the relative abundance of each protein in UniRef90 (RPKM, reads per kilobase per million). Functional analysis was performed on the resulting relative abundance tables of various functional databases in the KEGG and GO databases.

Abundance clustering analysis, principal component analysis, and sample clustering analysis were conducted based on species abundance and functional abundance tables. Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) analysis is an analytical tool for discovering and interpreting biomarkers in high-dimensional data, which allows comparisons between two or more groups, as well as comparative analysis between subgroups within groups, to identify species with significant differences in abundance between groups. This analysis first uses the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test to detect species with significant differences in abundance between different groups. The Wilcoxon rank sum was subsequently used to test the consistency of differences between different subgroups of different species in the previous step. Finally, linear regression analysis (LDA) was used to estimate the magnitude of the impact of the abundance of each species on the effect of differences (LDA score). The higher the LDA score is, the greater the difference in species between groups. LEfSe identified communities or species with significant differences in sample partitioning (default: LDA > 3 microorganisms). Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was performed with the Bray–Curtis distance for diversity index analysis. KEGG was used for the functional analysis of the gut microbiota. RDA and heatmap analysis were used to identify the clinical factors affecting microbial community composition.

IBM SPSS 26.0 and R software (version 4.0.2) were used for data analysis. The software used for sequencing data processing included Kraken (2.0.7 beta), Bracken (2.0), KneadData (0.7.4), Trimmatic (2.3.5.1), and FastQC (0.11.9). The data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD) for normally distributed data and were analyzed using t-tests. Skewed data are presented as median (interquartile range) [M (Q)] and were analyzed using rank-sum tests. Count data are presented as counts (percentages) [n (%)] and were analyzed via the chi-square test or Fisher’s test. PCoA, visualization, and statistical analysis were conducted via various R packages. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Subject characteristics

A total of 60 subjects were included in the study and were divided into three groups: 40 in the IgA nephropathy (IgAN) group, 20 in the normal renal function IgAN (NR-IgAN) group, 20 in the abnormal renal function IgAN (AR-IgAN) group, and 20 in the healthy control group. We compared the data between the IgAN normal renal function group and the IgAN abnormal function group (Table 1). We also compared the data between the IgAN group and the control group (Table S1, in the supplementary materials). Table S1 (Supplementary material) and Table 1 provide an overview of the demographic and laboratory characteristics of the subjects.

Table 1.

Comparison of data between IgAN normal renal function group and IgAN abnormal renal function group.

| NR-IgAN group | AR-IgAN group | T/Z/X2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 20 | 20 | ||

| Age (y) | 30.55 ± 6.48 | 42 ± 13.55 | −3.410 | 0.002 |

| Smoking [n(%)] | 3(15%) | 5(25%) | 0.156 | 0.693 |

| Drinking [n(%)] | 6(30%) | 5(25 %) | 0.125 | 0.723 |

| Sex | 0.107 | 0.744 | ||

| Male [n(%)] | 12(60%) | 13(65%) | ||

| Female [n(%)] | 8(40%) | 7(35%) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.25 ± 3.78 | 25.61 ± 4.49 | −1.034 | 0.308 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 125.05 ± 19.12 | 138.70 ± 14.69 | −2.531 | 0.016 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 81.40 ± 10.44 | 91.90 ± 9.85 | −3.271 | 0.002 |

| MAP (mmHg) | 95.95 ± 12.34 | 107.50 ± 10.47 | −3.191 | 0.003 |

| Alb (g/L) | 32.73 ± 9.08 | 29.88 ± 9.63 | 0.961 | 0.343 |

| 24h-UPro (g/L) | 894.95 ± 933.01 | 4996.5100 ± 7916.20 | −2.301 | 0.033 |

| Scr (μmol/L) | 81.65 ± 22.94 | 250.75 ± 151.43 | −4.938 | <0.001 |

| eGFR (ml/min) | 101.26 ± 22.91 | 32.25 ± 15.68 | 11.117 | <0.001 |

| PCR (mgP/gCR) | 834.23 ± 641.82 | 2035.16 ± 2427.34 | −2.139 | 0.039 |

| UA (μmol/L) | 408.45 ± 148.98 | 514.60 ± 146.59 | −2.271 | 0.029 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 5.99 ± 2.91 | 6.92 ± 3.37 | −0.930 | 0.358 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.59 ± 1.22 | 2.25 ± 1.27 | −1.678 | 0.101 |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 1.24 ± 0.48 | 1.31 ± 0.41 | −0.522 | 0.605 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 3.72 ± 2.20 | 4.31 ± 2.58 | −0.780 | 0.440 |

| 25 (OH) D3(nmol/L) | 39.87 ± 20.40 | 35.65 ± 21.11 | 0.642 | 0.525 |

| P (mmol/L) | 1.14 ± 0.17 | 1.23 ± 0.29 | −1.192 | 0.243 |

| Ca (mmol/L) | 2.18 ± 0.17 | 2.12 ± 0.19 | 1.038 | 0.306 |

BMI: Body Mass Index. SBP: Systolic blood pressure. DBP: Diastolic blood pressure. MAP: Mean arterial pressure. Alb: Albumin. 24h-UPro: 24-h urine protein. Scr: Serum creatinine. PCR: Urinary protein to creatinine ratio. UA:Uric acid. TC: Total cholesterol. TG: Triglyceride. HDL: High density lipoprotein. LDL: Low density lipoprotein. P: Blood phosphorus. Ca: blood calcium.

There were no significant differences in age or sex between the IgAN patients and the healthy controls. BMI, serum albumin, total cholesterol, triglyceride, high-density lipoprotein, low-density lipoprotein, 25(OH) D3, blood phosphorus, blood calcium levels, smoking history, and alcohol consumption history were not significantly different between the NR-IgAN and AR-IgAN groups. However, the AR-IgAN group was older and had increased systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, mean arterial pressure, random urine protein/creatinine, 24-h urine protein, serum creatinine, blood uric acid levels, and a significantly reduced eGFR (p < 0.05).

Differences in gut microbial communities between the IgAN group and the healthy control group

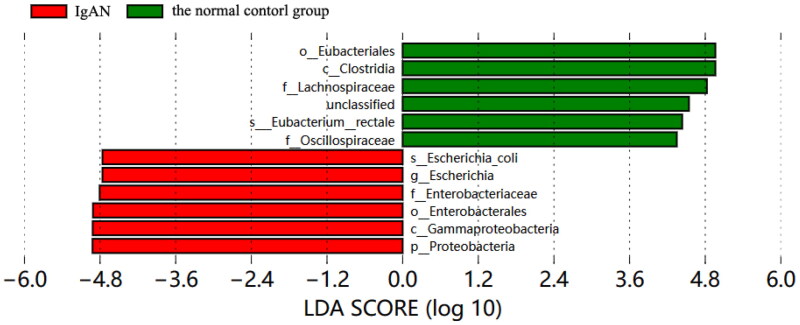

Metagenomic sequencing revealed significant differences in the composition of the intestinal microbiota between the IgAN group and the healthy control group (PERMANOVA: F = 2.22, p = 0.008). LEfSe analysis (Figure 1) revealed that the characteristic microbiota in the IgAN group belonged to the phylum Proteobacteria, class Gammaproteobacteria, order Enterobacterales, family Enterobacteriaceae, genus Escherichia, and species Escherichia coli. In contrast, the characteristic microbiota in the healthy control group was characterized by the class Clostridia, order Eubacteriales, family Lachnospiraceae, family Oscillospiraceae, and species Eubacterium rectale. Compared with the healthy control group, the IgAN group presented greater relative abundances of the phyla Proteobacteria (22.29% vs. 8.18%), Gammaproteobacteria (21.94% vs. 7.96%), Enterobacterales (21.53% vs. 7.73%), Enterobacteriaceae (17.82% vs. 7.70%), Escherichia (14.02% vs. 5.55%), and Escherichia coli (14.01% vs. 5.54%) (p = 0.0061, p = 0.0066, p = 0.0072, p = 0.0264, p = 0.0287, p = 0.0288, respectively). Moreover, compared with the NR-IgAN group, the healthy control group presented greater relative abundance of the class Clostridia (42.89% vs. 29.86%) and the species Eubacterium rectale (6.20% vs. 0.68%).

Figure 1.

LEfSe analysis of LDA column chart of IgAN group and normal control group.

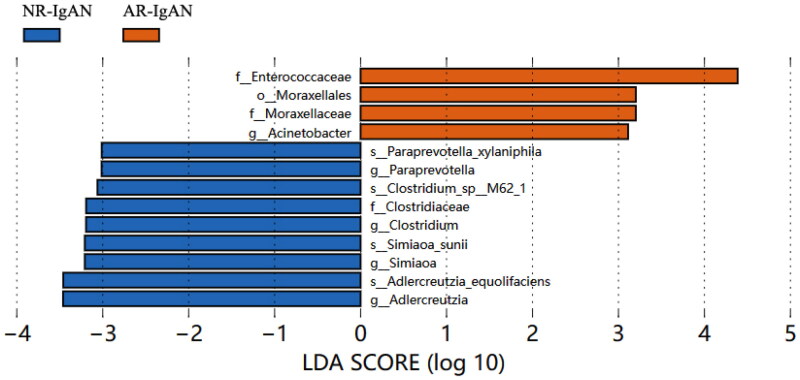

Differences in gut microbial communities between the NR-IgAN and AR-IgAN groups

Comparison of the gut microbiota between the NR-IgAN and AR-IgAN groups revealed greater abundances of the family Enterococcaceae, order Moraxellales, family Moraxellaceae, and genus Acinetobacter in the AR-IgAN group (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

LEfSe analysis of LDA column chart of NR-IgAN group and AR-IgAN group.

Correlations between the gut microbiota and clinical characteristics

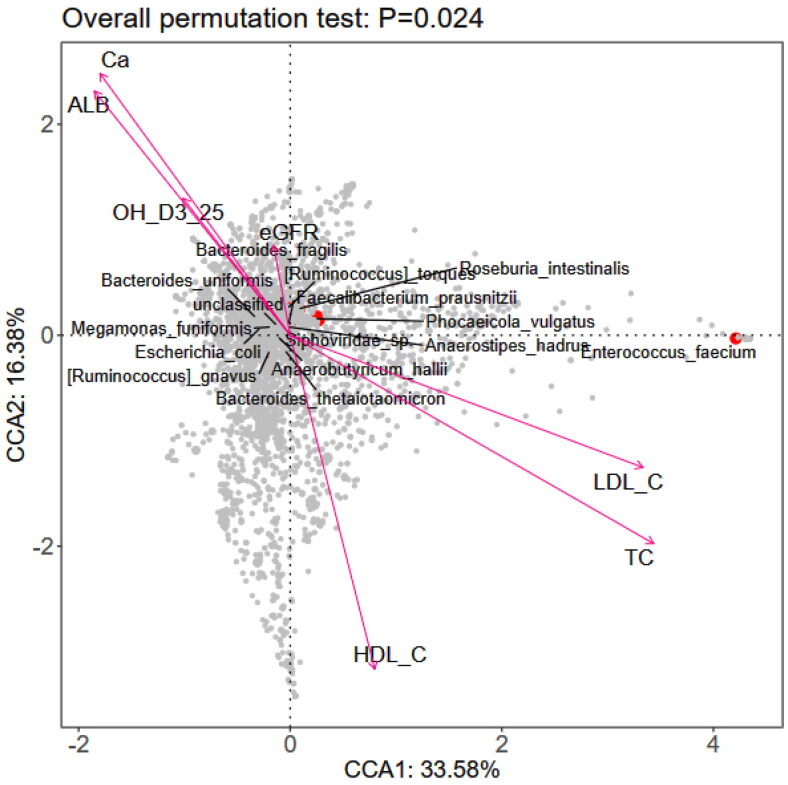

Correlation analyses between the gut microbiota and clinical indicators of IgAN patients and healthy controls revealed significant negative correlations with the eGFR, blood albumin, 25(OH) D3, and blood calcium levels, and positive correlations with the low-density lipoprotein, total cholesterol, and high-density lipoprotein levels (P values <0.05) (Supplementary material, Figure S1). Further analysis at the species level indicated that the eGFR, serum albumin, 25(OH) D3, blood calcium, low-density lipoprotein, total cholesterol, and high-density lipoprotein levels were associated with the composition of the gut microbiota in IgAN patients with normal renal function (total p = 0.024; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

RDA analysis diagram of intestinal microflora ana clinical indicators at species level.

TC: Total cholesterol; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein; LDL-C: Low density lipoprotein; ALB: Serum albumin; eGFR: Estimating glomerular filtration rate; Ca: Blood calcium.

We conducted a bivariate correlation analysis using Spearman correlation between the above microbiota and IgA nephropathy and renal function and found statistical significance (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Correlation analysis between gut microbiota and IgA nephropathy.

| The type of Gut Microbiota | R | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Order Eubacteriales | −0.405 | 0.001 |

| Order Enterobacterales | 0.304 | 0.018 |

| Class Clostridia | −0.404 | 0.001 |

| Class Gammaproteobacteria | 0.308 | 0.017 |

| Family Lachnospiraceae | −0.357 | 0.005 |

| Family Oscillospiraceae | −0.255 | 0.049 |

| Family Enterobacteriaceae | 0.28 | 0.030 |

| Species Escherichia coli | 0.333 | 0.009 |

| Species Eubacterium rectale | −0.376 | 0.003 |

| Genus Escherichia | 0.333 | 0.009 |

| Phylum Proteobacteria | 0.298 | 0.021 |

Table 3.

Correlation analysis between gut microbiota and renal dysfunction of IgA nephropathy.

| The type of Gut Microbiota | r | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Family Enterococcaceae | 0.312 | 0.050 |

| Family Clostridiaceae | −0.351 | 0.026 |

| Order Moraxellales | 0.401 | 0.010 |

| Genus Acinetobacter | 0.367 | 0.020 |

| Genus Paraprevotella | −0.308 | 0.054 |

| Genus Clostridium | −0.394 | 0.012 |

| Genus Simiaoa | −0.355 | 0.025 |

| Genus Adlercreutzia | −0.329 | 0.038 |

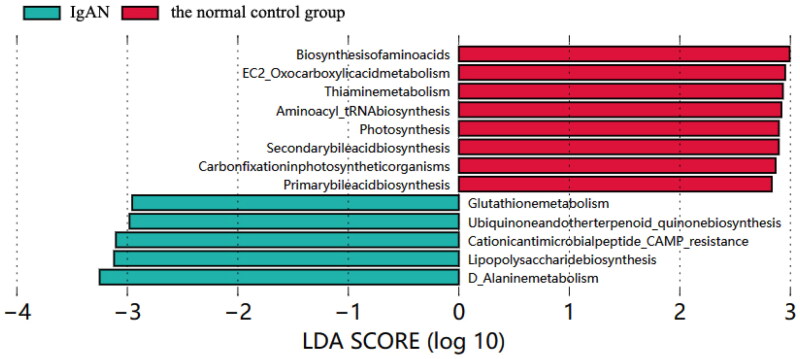

Functional annotation and analysis of the gut microbiota

LEfSe analysis was used to explore functional differences in KEGG pathways between the IgAN and healthy control groups. The IgAN group presented decreased abundance of genes related to primary and secondary bile acid metabolic pathways, aminoacyl tRNA biosynthesis, vitamin B1 metabolism, oxycarboxylic acid metabolism, and amino acid metabolism. In contrast, alanine metabolism, lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis, cationic antimicrobial peptide resistance, ubiquitin, terpenoid quinone biosynthesis, and glutathione metabolism pathways were enriched (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

LEfSe analysis LDA histogram of basic metabolic pathways in KEGG.

Bile acid metabolism and Escherichia coli

The primary bile acid metabolism pathway function was related mainly to Escherichia coli and Shigella sonnei. These findings indicate that the bile acid metabolism pathway in IgAN patients is disrupted, while the synthesis of lipopolysaccharides is abnormally active (Supplementary material, Figures S2 and S3).

Effects of different baseline gut microbiota on treatment outcomes

We conducted an analysis of IgA nephropathy (IgAN) cohort data from the study subjects after renal biopsy, the results of which are shown in Table S2 (Supplementary material). Among them, 12 patients (20%) were lost to follow-up. Only one patient started dialysis within 2 years. Based on the cohort data and analysis results, we were unable to detect significant differences in the gut microbiota among patients with different treatment outcomes.

Discussion

The results of our metagenomic sequencing analysis of the gut microbiota in IgAN patients have provided valuable insights into the role of the gut microbiota in the kidney disease. This study not only demonstrated differences in the overall composition of the gut microbiota between IgAN patients and healthy controls but also revealed variations in the gut microbiota composition between IgAN patients with normal and abnormal renal function. These findings expand our understanding of the complex interplay between the gut microbiota and IgAN.

Our findings suggest that, in IgAN patients, the relative abundance of the entire evolutionary tree of the phyla Proteobacteria, class Proteobacteria, order Enterobacteriales, family Enterobacteriaceae, genus Escherichia, and species Escherichia coli is significantly greater than that of the healthy population. Escherichia coli is a common inhabitant of human and animal intestines. Although it typically exists harmlessly, certain serotypes of Escherichia coli can lead to gastrointestinal infections in humans and animals. The pathogenesis of IgAN is closely related to mucosal immune dysfunction, yet the underlying mechanisms remain unclear [18]. A preliminary study [19] has shown that fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) can reduce proteinuria in refractory IgAN patients, with one patient exhibiting a significant reduction in Proteobacteria and Escherichia coli abundance after FMT. Research has also demonstrated that Escherichia coli can interact with the intestinal mucosa, leading to mitochondrial apoptosis in macrophages and the activation of Nod-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasomes [20, 21]. This interaction between Escherichia coli and the NLRP3 inflammasome may be a key mechanism through which Escherichia coli overactivates mucosal immunity.

Therapeutic approaches for targeting the gut microbiota in IgAN patients have madesignificant progress. An important therapy for improving patient prognosis is controlling the pivotal source mechanism of IgAN. However, our study did not explore the direct effects of E. coli. Some studies have shown that successful immunosuppressive therapy in IgAN patients is associated with a significant decrease in the abundance of Escherichia coli Shigella in the gut microbiota [22–25]. Inhibiting proinflammatory cytokines has also been linked to a reduction in Escherichia coli abundance in the gut microbiota. These findings suggest that targeting Escherichia coli may reduce the occurrence of IgAN and slow the progression of the disease. However, further research is needed to explore the specific molecular mechanisms through which Escherichia coli affects IgAN onset and progression.

Our study explored the functional annotation and analysis of the gut microbiota in IgAN. We compared the functions and related pathways of the gut microbiota between IgAN patients and healthy controls. Our analysis indicated disruptions in the metabolic pathways of bile acids (BAs), specifically the primary and secondary bile acid metabolic pathways, in IgAN patients. Additionally, we observed a significant increase in the lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis metabolic pathway in the IgAN group compared with the healthy control group. These findings suggest that bile acid metabolism in IgAN patients is disrupted, whereas lipopolysaccharide synthesis is abnormally active. Notably, the primary bile acid metabolism pathway was associated primarily with Escherichia coli and Shigella sonnei.

Previous studies have shown that fecal FMT can restore microbial diversity and increase the levels of short-chain fatty acids and bile acids, resulting in reduced IgA production. Moreover, ESRD patients present significantly increased total bile acid levels, and the composition of bile acids is associated with poor prognosis. An imbalance in the gut microbiota–bile acid axis can lead to increased secretion of secondary bile acids, which can activate various signaling pathways within the intestinal epithelium, leading to visceral hypersensitivity and damage to the intestinal mucosal barrier [26, 27].

Inflammasomes may overactivate mucosal immune inflammatory responses, playing a pivotal role in IgAN pathogenesis [28–31]. These findings suggest that interventions targeting the gut microbiota-associated bile acid metabolism pathway may provide a novel approach for IgAN prevention and treatment.

A previous study[32] used ROC curves created from the active rumen bacteria and sublingual muscle bacteria genera of IgAN patients for fitting, and the AUC was 0.927, which relatively accurately distinguished IgAN patients from the healthy population. The model has good calibration, indicating that the prediction model constructed using intergroup differential microbiota can accurately distinguish between IgAN patients and healthy individuals, as well as between IgAN patients with normal and abnormal renal function. These findings suggest that the inclusion of the characteristic gut microbiota as a biomarker for IgAN diagnosis and prognosis prediction has clinical values and should be investigated in future research.

Many studies have shown that transplanting feces can treat diseases associated with intestinal flora dysregulation. Transplanting feces from IgAN patients to IgAN model mice can promote an increase in the abundance of Proteobacteria, leading to more severe renal pathological phenotypes [33]. A domestic study suggested that the traditional Chinese medicine prescription Zhenwu Tang reduces the abundance of Proteobacteria in the intestinal microbiota of mice and that the deposition of IgA in the mesangial area is also significantly reduced [34]. A preliminary study [19] also confirmed that intensified fresh FMT in two refractory IgAN patients can reduce proteinuria, and one of the patients with a gut rich in Escherichia coli Shigella also showed significant depletion of Proteobacteria and Escherichia coli Shigella abundance.

Notably, there is an interaction effect between immunologic dysfunction of the intestinal system and the intestinal microbiome in IgAN patients. The gut microbiota in chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients can undergo changes due to various factors [35]. When kidney function decreases, metabolic waste accumulates in the body, and the gut biochemical environment may change, leading to an imbalance in the gut microbiota and impaired intestinal barrier function. However, the mechanism underlying the interaction between the gut microbiota and IgA nephropathy requires further research, which will provide guidance for clinical microecological treatment.

The innovation of this study lies in the use of metagenomic sequencing technology, which has greater species annotation ability than amplicon technology does, to identify the gut microbiota characteristics of IgAN patients, analyze the related functions of the microbiota, and compare the gut microbiota characteristics of IgAN patients with normal and abnormal kidney function. This provides a theoretical reference for a more comprehensive understanding of the role of the gut microbiota in the occurrence and development of IgAN. The study of the gut microbiota will provide new targets and ideas for the early prediction of IgAN and targeted prevention and treatment of intestinal mucosal immune abnormalities during its pathogenesis. However, our study has several limitations, including a small sample size and a lack of comparisons with other glomerular diseases, such as membranous nephropathy. Moreover, our study did not conduct a double validation of the causal effects between the gut microbiota and IgAN. We could not match the food intake between the patient group and the healthy control group at every meal. Furthermore, we did not conduct targeted metabolomics analysis to pinpoint specific bile acids associated with IgAN. Finally, we did not collect specific dietary data for analysis.

In conclusion, our study sheds light on the role of the gut microbiota, particularly Escherichia coli, in IgAN. Understanding these associations and potential mechanisms may open new avenues for treatment and prevention strategies. Future research should involve larger sample sizes, multicenter collaborations, multiomics approaches, and in vitro and in vivo experiments to explore the specific mechanisms underlying the influence of gut microbiota on IgAN.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (2022GXNSFAA035458) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (81960135).

Authors’ contributions

YD designed the study, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. ZhiN designed the study, collected and analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. YuL designed the study and revised the manuscript. MeiW and YuanX collected stool samples and analyzed data. XiaoL, RuoZ and ZhenY collected and analyzed data. LP collected data and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Wyatt RJ, Julian BA.. IgA nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(25):2402–2414. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1206793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGrogan A, Franssen CF, de Vries CS.. The incidence of primary glomerulonephritis worldwide: a systematic review of the literature. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(2):414–430. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lai KN, Tang SC, Schena FP, et al. IgA nephropathy. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2(1):16001. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Amico G. Natural history of idiopathic IgA nephropathy: role of clinical and histological prognostic factors. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36(2):227–237. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2000.8966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu HH, Chiang BL.. Diagnosis and classification of IgA nephropathy. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(4-5):556–559. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki H, Kiryluk K, Novak J, et al. The pathophysiology of IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(10):1795–1803. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011050464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He J-W, Zhou X-J, Lv J-C, et al. Perspectives on how mucosal immune responses, infections and gut microbiome shape IgA nephropathy and future therapies. Theranostics. 2020;10(25):11462–11478. doi: 10.7150/thno.49778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou N, Shen Y, Fan L, et al. The characteristics of intestinal-barrier damage in rats with IgA nephropathy. Am J Med Sci. 2020;359(3):168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2019.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhong Z, Tan J, Tan L, et al. Modifications of gut microbiota are associated with the severity of IgA nephropathy in the Chinese population. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;89(Pt B):107085. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.107085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu X, Du J, Xie Y, et al. Fecal microbiota characteristics of Chinese patients with primary IgA nephropathy: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21(1):97. doi: 10.1186/s12882-020-01741-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nie C, Li Y, Li R, et al. Distinct biological ages of organs and systems identified from a multi-omics study. Cell Rep. 2022;38(10):110459. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramírez-Pérez O, Cruz-Ramón V, Chinchilla-López P, et al. The role of the gut microbiota in bile acid metabolism. Ann Hepatol. 2017;16(Suppl. 1: s3-105):s15–s20. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0010.5494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fiorucci S, Carino A, Baldoni M, et al. Bile acid signaling in inflammatory bowel diseases. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66(3):674–693. doi: 10.1007/s10620-020-06715-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Angelis M, Montemurno E, Piccolo M, et al. Microbiota and metabolome associated with immunoglobulin A nephropathy (IgAN). PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99006. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piccolo M, De Angelis M, Lauriero G, et al. Salivary microbiota associated with immunoglobu lin A nephropathy. Microb Ecol. 2015;70(2):557–565. doi: 10.1007/s00248-015-0592-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brito JS, Borges NA, Dolenga CJ, et al. Is there a relationship between tryptophan dietary intake and plasma levels of indoxyl sulfate in chronic kidney disease patients on hemodialysis? J Bras Nefrol. 2016;38:396–402. doi: 10.5935/0101-2800.20160064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han L, Fang X, He Y, et al. ISN forefronts symposium 2015: IgA nephropathy, the gut microbiota, and gut–kidney crosstalk. Kidney Int Rep. 2016;1(3):189–196. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2016.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gesualdo L, Di Leo V, Coppo R.. The mucosal immune system and IgA nephropathy. Semin Immunopathol. 2021;43(5):657–668. doi: 10.1007/s00281-021-00871-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao J, Bai M, Ning X, et al. Expansion of Escherichia-Shigella in gut is associated with the onset and response to immunosuppressive therapy of IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022;33(12):2276–2292. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2022020189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deo P, Chow SH, Han ML, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction caused by outer membrane vesicles from Gram-negative bacteria activates intrinsic apoptosis and inflammation. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5(11):1418–1427. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0773-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu B, Nakamura T, Inouye K, et al. Novel role of PKR in inflammasome activation and HMGB1 release. Nature. 2012;488(7413):670–674. doi: 10.1038/nature11290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Endo Y, Kanbayashi H, Hara M.. Experimental immunoglobulin A nephropathy induced by gram-negative bacteria. Nephron. 1993;65(2):196–205. doi: 10.1159/000187474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu B, Piao X, Niu W, et al. Kuijieyuan decoction improved intestinal barrier injury of ulcerative colitis by affecting TLR4-dependent PI3K/AKT/NF-kB oxidative and inflammatory signaling and gut microbiota. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:1036. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.01036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng L, Gao X, Nie L, et al. Astragalin attenuates dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced acute experimental colitis by alleviating gut microbiota dysbiosis and inhibiting NF-kB activation in mice. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:2058. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.02058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu J, Chen N, Wu Z, et al. 5-Aminosalicylic acid alters the gut bacterial microbiota in patients with ulcerative colitis. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1274. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lavelle A, Sokol H.. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites as key actors in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17(4):223–237. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0258-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhan K, Zheng H, Li J, et al. Gut microbiota-bile acid crosstalk in diarrhea-irritable bowel syndrome. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:3828249. doi: 10.1155/2020/3828249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vilaysane A, Chun J, Seamone ME, et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome promotes renal inflammation and contributes to CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(10):1732–1744. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010020143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li X, He C, Li N, et al. The interplay between the gut microbiota and NLRP3 activation affects the severity of acute pancreatitis in mice. Gut Microbes. 2020;11(6):1774–1789. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2020.1770042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Q, Ran X, He Y, et al. Acetate downregulates the activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes and attenuates lung injury in neonatal mice with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:595157. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.595157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu QX, Zhou Y, Li XM, et al. Ammonia induce lung tissue injury in broilers by activating NLRP3 inflammasome via Escherichia/Shigella. Poult Sci. 2020;99(7):3402–3410. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2020.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fan XM, Mi Y, Wang CL.. Preliminary study on the biological characteristics of intestinal flora in IgA nephropathy based on high-throughput sequencing. Chin J Neahrol. 2022;38(2):91–99. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn441217-20210129-00014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lauriero G, Abbad L, Vacca M, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation modulates renal phenotype in the humanized mouse model of IgA nephropathy. Front Immunol. 2021;12:694787. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.694787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li J, Cao Y, Lu R, et al. Integrated fecal microbiome and serum metabolomics analysis reveals abnormal changes in rats with immunoglobulin A nephropathy and the intervention effect of Zhen Wu Tang. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:606689. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.606689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Felizardo RJ, Castoldi A, Andrade-Oliveira V, et al. The microbiota and chronic kidney diseases: a double-edged sword. Clin Transl Immunol. 2016;5(6):e86. doi: 10.1038/cti.2016.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.