Abstract

Outcomes are presented for a multisite retrospective case series, describing a contemporary cohort of 22 immunocompromised patients with persistent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) polymerase chain reaction positivity who were retreated with antiviral therapy. For those with data available 14 and 30 days after commencement of antiviral therapy, 41% (9 of 22) and 68% (15 of 22), respectively, cleared COVID-19.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in immnuocompromised hosts presents with similar signs and symptoms to other patient cohorts, but the severity and patient outcomes are generally worse [1]. Immunocompromised hosts are also more likely to experience prolonged viral replication and therefore take longer to be considered noninfectious [2, 3]. As viral culture is not routinely available for most patient samples, a semiquantitative review of positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) results (eg, PCR cycle threshold [Ct]) is often used to risk stratify patients as to the likelihood of ongoing severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) replication. PCR positivity for SARS-CoV-2 at 21–30 days after initial diagnosis is generally considered persistent positivity, occurring in 15%–25% of patients with hematological cancer [2, 4]. Prolonged PCR positivity may delay the administration of further immunosuppressive therapy/chemotherapy and prolong inpatient isolation precautions [3]. This can, in turn, adversely affect the frequency of medical care, rates of preventable adverse events, and hospital length of stay [5]. Chronic active infection with SARS-CoV-2 may predispose to the development of viral mutations, giving rise to new variants of interest, antiviral resistance, or immune escape [6].

For immunocompromised hosts, COVID-19 directed antiviral therapy is recommended to commence within 5–7 days of initial symptoms, regardless of disease severity [7]. There are currently no treatment recommendations for relapsed or refractory COVID-19. A recent survey of Australasian Infectious Diseases Physicians demonstrated wide heterogeneity in management approaches for persistent COVID-19 PCR positivity, with clinical uncertainty as to (1) the indication for treatment; (2) the preferred antiviral agent; (3) prescription of antivirals as single or combination therapy; and (4) duration of therapy [8]. We sought to describe outcomes for patients with persistent COVID-19 treated with antiviral agents in a multicenter Australian study.

METHODS

Study Setting and Patient Population

A retrospective cohort study was undertaken at 5 tertiary academic hospitals in Melbourne, Australia. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were (1) immunocompromised [9], (2) received a course of antiviral therapy for persistent COVID-19 between 1 January 2022 and 30 June 2023, and (3) had PCR results available following therapy for persistent COVID-19. During this period Omicron was the dominant variant, emerging in Australia in November 2021 and replacing Delta as the leading cause of COVID-19 infection in early 2022 [10, 11]. Subvariants BA.1 and BA.2 circulated in the first half of 2022, before the emergence of BA.4 and BA.5 in the second half of 2022. Subvariant XBB was predominant in the first half of 2023.

Persistent COVID-19 positivity was defined as either a positive PCR result with a Ct value <30 or positive antigen lateral flow assay result ≥20 days after diagnosis. This corresponded to the timing and threshold used for clearance of immunocompromised patients from respiratory isolation precautions at all institutions, based on local practice and international guidelines [3, 12]. Treatment of persistent COVID-19 infection with a late course of antiviral agents was initiated by treating clinicians under the supervision of local infectious diseases specialists, for the perceived benefit to the patient of improving symptoms or clearing presumed persistent COVID-19 infection. Selection of treatment agent and duration was at the discretion of treating infectious diseases specialists.

SARS-CoV-2 Testing and Study Outcomes

SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR testing was undertaken at the primary diagnostic laboratories for each site as part of routine clinical care. All laboratories used commercial SARS-CoV-2 PCR assays and were accredited for testing by Australia's National Accreditation Testing Authority (www.nata.com.au). The primary outcome of the study was the proportion of individuals with an indeterminate or negative PCR result or the first of ≥2 positive sequential PCR results with a Ct value >30 within 14 days of receipt of antiviral therapy for persistent COVID-19. Patients were excluded from outcome analysis if they died within 5 days after treatment initiation or did not have any further SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing after commencement of antiviral therapy.

Data and Ethics Management

Data were retrospectively extracted at each site after review of patient electronic medical records, pharmacy dispensing information systems, and laboratory information systems into a REDCap database. Statistical tests were undertaken using GraphPad Prism software (version 10.2.0).

Patient Consent Statement

This study was approved as a multisite protocol with a waiver of patient consent authorized by the Human Research Ethic Committee from the Royal Melbourne Hospital (no. 2022.236).

RESULTS

Over the study period, 26 patients were prescribed antivirals for persistent COVID-19 of which 22 patients had PCR results available for review (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). All patients had previously received ≥2 doses of a COVID-19 vaccine (median and interquartile range [IQR], 3), and 86% (19 of 22) had received early directed antiviral therapy for this episode of COVID-19 infection (within 5 days of symptom onset). A persistently positive COVID-19 status required adjustment to planned immunosuppressive therapy in almost half of cases (10 of 22 [46%]).

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of 22 Patients Treated With Late or Retreatment Coronavirus Disease 2019 Antiviral Therapy for Persistently Polymerase Chain Reaction Positive Infection

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%)a |

|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 64 (54–74) |

| Male sex | 15 (68.2) |

| Immunosuppression | |

| Hematological conditionb,c | 16 (72.7) |

| Renal SOT | 2 (9.1) |

| Anti–CD-20 therapy (nonmalignant condition) | 4 (18.2) |

| COVID-19 infection details at diagnosis | |

| Results available within 48 h after COVID-19 diagnosis | 18 (81.8) |

| Blood cell count, median (IQR), ×109/L | |

| WBCs | 4.5 (2.9–8.4) |

| Lymphocytes | 0.65 (0.38–1.62) |

| Neutrophils | 2.9 (1.6–4.5) |

| CRP, median (IQR), mg/L | 19 (4–48) |

| Prior COVID-19 vaccine doses, median (IQR), no. | 3 (3–3) |

| Prior tixagevimab-cilgavimab therapy | 7 (31.8) |

| Hospital admission | 15 (68.2) |

| ICU admission | 6 (27.3) |

| COVID-19 therapy at diagnosis | |

| MPV | 3 (13.6) |

| NIR/r | 7 (31.8) |

| RDV | 8 (36.4) |

| MPV + RDV | 1 (4.5) |

| Nil AV therapy | 3 (13.6) |

| Steroid | 8 (36.4) |

| Baracitinib | 1 (4.5) |

| Tixagevimab-cilgavimab | 1 (4.5) |

| COVID-19 infection details at late/retreatment AV use | |

| Time from initial COVID-19 diagnosis, median (IQR), d | 35 (29–42) |

| PCR Ct on d 1 of AV use, median (IQR) | 22 (20–25) |

| Hospital admission | 19 (8.64) |

| ICU admission | 7 (31.8) |

| Change or delay to other immunosuppressive therapy due to COVID-19 status | 10 (45.5) |

| COVID-19 severity at time of late/retreatment AV used | |

| Asymptomatic | 4 (18.2) |

| Mild/moderate | 11 (50) |

| Severe/critical | 7 (32.8) |

| Late/retreatment COVID-19 therapy | |

| Single agent | 3 (13.6) |

| MPV | 1 (4.5) |

| NIR/r | 0 (0) |

| RDV | 2 (9.1) |

| Sequential single agents | 2 (9.1) |

| Dual agents at any time | 17 (77.3) |

| MPV + NIR/r | 10 (45.5) |

| MPV + RDV | 4 (18.2) |

| NIR/r + RDV | 3 (13.6) |

| Steroid therapy | 14 (63.6) |

| Baracitinib | 6 (27.3) |

| Tocilizumab | 0 (0) |

| Tixagevimab-cilgavimab | 3 (13.6) |

| Negative PCR result or sequential Ct >30 | |

| At d 14 after late/retreatment AVs | 9 (40.9) |

| Dual agents (n = 17) | 8 (47.0) |

| Single or sequential agents (n = 5) | 1 (20.0) |

| Short-total-duration therapy (n = 14) | 7 (50.0) |

| Longer-total-duration therapy (n = 8) | 2 (25.0) |

| At d 30 after late/retreatment AVs | 15 (68.2) |

Abbreviations: AV, antiviral; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CRP, C-reactive protein; Ct, cycle threshold; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; MPV, molnupirivair; NIR/r, nirmatrelvir/ritonavir; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; RDV, remdesevir; SOT, solid organ transplant; WBCs, white blood cells.

aData represent no. (%) of patients unless otherwise specified.

bHematological conditions include lymphoma (n = 7), leukemia (n = 5), hematopoietic stem cell transplant (n = 3), and multiple myeloma (n = 1).

cFive of 18 were also on anti–CD-20 therapy.

dCOVID-19 severity was defined according to World Health Organization criteria (https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/332196/WHO-2019-nCoV-clinical-2020.5-eng.pdf). Mild was defined as symptomatic without clinical signs of pneumonia; moderate, as oxygen saturation (Spo2) ≥90% at rest on room air with clinical signs of pneumonia (eg, fever, cough, or dyspnea); severe, as Spo2 <90% at rest on room air, respiratory rate >30 breaths/min, or severe respiratory distress; and critical, as (1) respiratory failure or adult respiratory distress syndrome requiring high-flow nasal oxygen or noninvasive ventilation/intubation or (2) sepsis/septic shock.

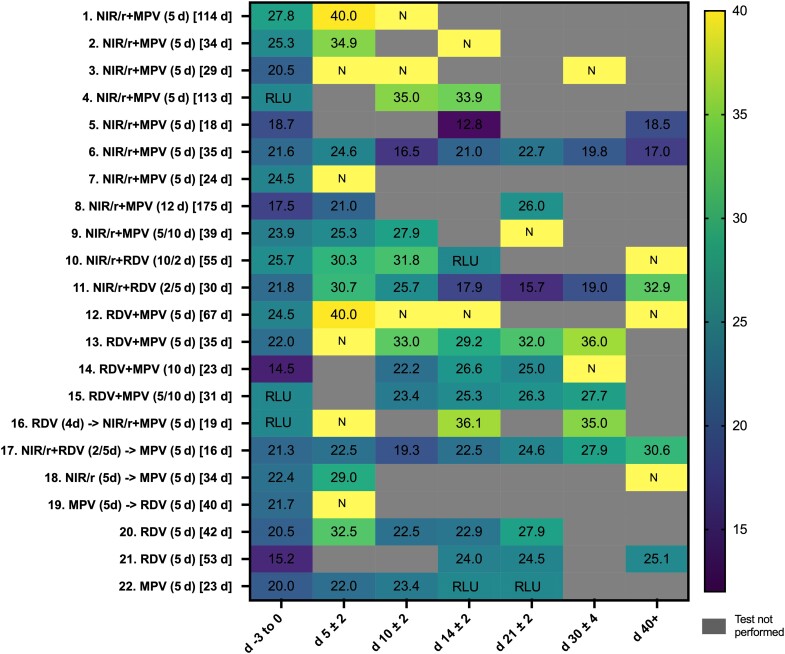

The antiviral therapy and duration selected by treating clinicians for therapy >20 days of COVID-19 was diverse (Table 1 and Figure 1). Both monotherapy (n = 3) and dual therapy (n = 16) was used; 2 patients received sequential monotherapy, and 1 received dual antivirals followed by sequential use of a third agent. No patient received convalescent plasma therapy or additional intravenous immunoglobulin specifically for COVID-19 treatment. The median duration from initial COVID-19 PCR/antigen lateral flow assay diagnosis to late/retreatment with antiviral agents was 35 days (IQR, 29–42 days).

Figure 1.

Heat map reporting cycle threshold (Ct) values for real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) results for patients receiving a second course of antiviral therapy for persistent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection. Darker colors represent lower Ct values, suggestive of increased amounts of COVID-19 RNA present in samples; lighter colors represent higher Ct values or negative PCR results (N), suggestive of lower amounts of COVID-19 RNA present in samples; numbers in colored boxes reflect the Ct values for the tests, which are provided as a semiquantitative guide and are not directly comparable. Across the 4 health services the following assays were used during the study period: the coronavirus typing assay (AusDiagnostics), Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) (Cepheid), Alinity m SARS-CoV-2 (Abbott), and Aptima SARS-CoV-2 Assay (Hologic). Numbers 1–22 represent the case numbers in Supplementary Table 1, which provides additional clinical information by case. Numbers in parentheses represent duration of treatment in days with each agent; numbers in square brackets represent the duration in days of COVID-19 infection from diagnosis to the time of treatment with a late/retreatment course of COVID-19 antiviral therapy. Abbreviations: MPV, molnupiravir (Lagevrio); NIR/r, nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid); RDV, remdesevir (Veklury); RLU, relative light units (output for the Hologic Panther SARS-CoV-2 assay, which are not comparable to Ct values).

Follow-up PCR results are presented in Figure 1. All follow-up samples except one (a bronchoalveolar wash sample) were combined deep nasal and oral swab samples. By day 14 after commencement of retreatment antiviral therapy, 41% (9 of 2) had negative results or sequential Ct values >30. Of patients receiving dual therapy, 47% (8 of 17) achieved viral clearance at day 14, compared with none of those receiving single agents (0 of 3) and 1 of 2 receiving sequential therapy. For those receiving dual agents who had PCR result available confirming clearance at any time (82% [14 of 17]), the median time to clearance (IQR) was 9 (5–25) days after the first day of antiviral therapy. For the 4 of 5 patients (80%) receiving either single agents or sequential monotherapy who achieved clearance at any time, the times to clearance were 7, 20, 42, and 46 days, respectively. At 14 days, for those receiving short-course antiviral therapy (≤5 days), 50% cleared infection (7 of 4), compared with 25% (2 of 8) of those receiving longer courses of therapy (>5 days). No adverse events were recorded for any participant.

DISCUSSION

Here we describe a contemporary cohort of vaccinated immunosuppressed patients who received treatment for persistent COVID-19 infection, the majority of whom received early directed COVID-19 antiviral therapy at diagnosis (88% [23 of 26]), during a period with reduced efficacy of directed monoclonal antibody therapy. We report a viral clearance rate of 41% (9 of 2) in this cohort at 14 days from antiviral therapy, in comparison with other cohorts of similar size (>10 patients) who have reported success in 30% [13] and 70%–79% [14–16]. In addition to cause of immunosuppression, timing of testing, and treatment heterogeneity, other factors contributing to a lower clearance in this study may relate to (1) study bias toward cases with active SARS-CoV-2 replication rather than residual RNA shedding, due to inclusion of only those with Ct <30; (2) higher baseline viral loads in respiratory samples, as estimated by a median Ct value of 22, compared with other case series [14]; (3) a majority of case patients who had already received early direct antiviral therapy, compared with studies describing late antiviral therapy in a largely antiviral naive cohort [13–16]; and (4) lower use of directed monoclonal antibody therapy.

In the next-largest cohort, Mikulska et al [16] report that participants who were antiviral naive at the time of late antiviral treatment (59.1% [13 of 22]) were more likely to respond to treatment than the cohort overall (100% [13 of 13] vs 75% [16 of 22]). Two case series with success at 14 days of 30% and 70%, including a majority of patients undergoing COVID-19 retreatment rather than late initial antiviral therapy, used a test of response approach [13, 15]. Antivirals were continued and escalated in a stepwise fashion (remdesivir [RDV] then nirmatrelvir/ritonavir [NIR/r] [15]) or using a variable sequential approach [13] until negative test results were returned. With this approach, response was achieved within 7–36 days for almost all patients.

Clinicians elected to treat the majority of patients in our study (73% [19 of 26]) with dual antiviral therapy. Theoretical benefits of dual therapy include enhanced viral clearance due to a synergistic viricidal activity and the minimization of viral resistance development. Preclinical studies have demonstrated synergy between RDV and molnupiravir in hamster models, RDV and NIR/r in vitro, and NIR/r and molnupiravir in mice and macaque models [17]. Multiple clinical reports describe the success of dual therapy with few adverse effects [16]; however, no head-to-head trials of single versus dual therapy are available. The numbers of patients who received single-agent or sequential therapy were too low in the present study for comparison, but among the few patients who received single-agent or sequential monotherapy the time to clearance was longer than for those receiving dual antiviral therapy (median, 31 vs 9 days respectively). The duration of successful treatment has generally been reported as shorter in cohorts receiving dual therapy [14, 16] than in those receiving sequential monotherapy [13, 15].

The current study is limited by its observational design, the nonuniform follow-up of cases, and the heterogeneity in both the degree of immunosuppression and other host-related factors in this study cohort. The small numbers of patients preclude analysis by type of immunosuppression or other subgroups. Although often used as a semiquantitative measure of viral load, Ct values are not as robust as viral culture or quantitative PCR for determining active viral replication. Use of the Ct value of 30 was based on local clinical practice and international guidelines [3, 12], but this cutoff included some patients may not have had active COVID-19 infection. Conversely, some “cleared” patients may have experienced viral replication, albeit at a lower level, given the rising Ct values over a number of tests. Lower respiratory tract specimens may give a better estimation of viral replication in patients with critical infection, but limited use of bronchoalveolar lavage meant that such samples were not available for testing or inclusion.

For outcome analysis it was necessary to define a time period for clearance (14 days), of which only 41% were able to achieve success. However, on review of the treatment response heat map (Figure 1), it can be seen that many of the case patients demonstrated rising Ct values after antiviral therapy but were not tested at designated time intervals that allowed them to be classified as cleared by day 14. This may have underestimated the effect of antivirals. Some asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic patients received antiviral therapy as their persistent COVID-19 infectious status (as defined locally) was affecting their clinical care. This situation may not be generalizable to other settings. The majority of our patients were cleared with a short course of therapy (50%); longer courses were associated with lower clearance rates (25%), suggesting that underlying patient specific factors may have influenced the selection of treatment duration as well as clearance outcome. Nevertheless these data suggests that the extension of therapy beyond 5 days may not be routinely necessary. A reasonable approach may include a test of response at 5 days, with the extension of therapy if predefined Ct criteria are not met.

The current study demonstrates a moderate response to directed antiviral therapy in immunocompromised hosts receiving a retreatment course of antiviral therapy for persistently positive COVID-19 infection. The majority of patients received dual antiviral therapy of short duration. Future studies should focus on this high-risk subgroup, considering both the type and duration of antiviral agents. The low case rate means that a large multicenter randomized control trial will be needed.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the clinicians and primary diagnostic laboratories at each health service for the provision of clinical and laboratory information and the clinical care of the patients. For supplementary information relating to diagnostic testing and PCR results, the authors thank Roy Chean MD (Eastern Health) and Tony Korman MD (Monash Health). They also thank the Australian Partnership for Preparedness Research on Infectious Diseases Emergencies (APPRISE) for support with this project.

Contributor Information

K A Bond, Department of Microbiology, Royal Melbourne Hospital, The Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Victorian Infectious Diseases Reference Laboratory, The Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Melbourne at The Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Department of Infectious Diseases, University of Melbourne at The Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Victorian Infectious Diseases Service, The Royal Melbourne Hospital at The Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

C Dendle, Department of Infectious Diseases, Monash Health, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Department of Infectious Diseases, School of Translational Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

S Guy, Department of Infectious Diseases, Eastern Health, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Eastern Health Clinical School, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

M A Slavin, Department of Infectious Diseases, University of Melbourne at The Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Victorian Infectious Diseases Service, The Royal Melbourne Hospital at The Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Department of Infectious Diseases, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Sir Peter MacCallum Department of Oncology, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria, Australia.

O Smibert, Department of Infectious Diseases, University of Melbourne at The Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Department of Infectious Diseases, Austin Health, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

N Ibrahim, Department of Infectious Diseases, Monash Health, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

P M Kinsella, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Melbourne at The Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Department of Infectious Diseases, University of Melbourne at The Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Department of Infectious Diseases, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

C O Morrissey, Department of Infectious Diseases, School of Translational Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Department of Infectious Diseases, Alfred Health, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

M A Moso, Department of Infectious Diseases, University of Melbourne at The Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Victorian Infectious Diseases Service, The Royal Melbourne Hospital at The Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

J J Sasadeusz, Department of Infectious Diseases, University of Melbourne at The Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Victorian Infectious Diseases Service, The Royal Melbourne Hospital at The Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Author contributions. K. A. B., C. D., S. G., M. A. S., C. O. M., M. A. M., J. J. S., and O. S. conceived, designed and implemented the project. K. A. B., S. G., P. M. K., M. A. M., N. I., and O. S. collected data, while K. A. B. and M. A. M. were involved in data curation. K. A. B. and M. A. M. undertook formal analysis of the data and data visualization. K. A. B., M. A. M., and J. J. S. were responsible for writing the original draft. All authors were involved in review of the manuscript and had access to the original data.

Data sharing statement. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, K. A. B., on reasonable request.

Financial support. This work was supported by The Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, University of Melbourne, Victoria Australia (seed grant 2022). Investigators are supported by the following National Health and Medical Research Council grants as follows: postgraduate scholarships GNT1191321 to K. A. B. and GNT2022238 to M. A. M., and investigator grant 1173791 to M. A. S. M. A. S. is also supported by a Synergy grant 2011100. All diagnostic testing and antiviral therapy was undertaken at each health service as part of standard-of-care clinical practice.

References

- 1. Vijenthira A, Gong IY, Fox TA, et al. Outcomes of patients with hematologic malignancies and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 3377 patients. Blood 2020; 136:2881–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lee S, Kim T, Lee E, et al. Clinical course and molecular viral shedding among asymptomatic and symptomatic patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection in a community treatment center in the Republic of Korea. JAMA Intern Med 2020; 180:1447–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cesaro S, Ljungman P, Mikulska M, et al. Recommendations for the management of COVID-19 in patients with haematological malignancies or haematopoietic cell transplantation, from the 2021 European Conference on Infections in Leukaemia (ECIL 9). Leukemia 2022; 36:1467–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Garcia-Vidal C, Puerta-Alcalde P, Mateu A, et al. Prolonged viral replication in patients with hematologic malignancies hospitalized with COVID-19. Haematologica 2022; 107:1731–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sprague E, Reynolds S, Brindley P. Patient isolation precautions: are they worth it? Can Respir J 2016; 2016:5352625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hettle D, Hutchings S, Muir P, Moran E. Persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection in immunocompromised patients facilitates rapid viral evolution: retrospective cohort study and literature review. Clin Infect Pract 2022; 16:100210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organisation . Therapeutics and COVID-19: Living guideline. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moso MA, Sasadeusz J, Morrissey CO, et al. Survey of treatment practices for immunocompromised patients with COVID-19 in Australasia. Intern Med J 2023; 53:619–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation . Recommendations on the use of a 3rd primary dose of COVID-19 vaccine in individuals who are severely immunocompromised. Version 4.2. 2023. Available at: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/atagi-recommendations-on-the-use-of-a-third-primary-dose-of-covid-19-vaccine-in-individuals-who-are-severely-immunocompromised?language=en. Accessed 15 April 2024.

- 10. Hadfield J, Megill C, Bell SM, et al. Nextstrain: real-time tracking of pathogen evolution. Bioinformatics 2018; 34:4121–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. COVID-19 Epidemiology and Surveillance Team . COVID-19 Australia: epidemiology report 75—reporting period ending 4 June 2023. Commun Dis Intell (2018) 2023:47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. European Center for Disease Prevention and Control . Guidance on ending the isolation period for people with COVID-19, third update. European Center for Disease Prevention and Control, Sweden, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Longo BM, Venuti F, Gaviraghi A, et al. Sequential or combination treatments as rescue therapies in immunocompromised patients with persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection in the Omicron era: a case series. Antibiotics 2023; 12:1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pasquini Z, Toschi A, Casadei B, et al. Dual combined antiviral treatment with remdesivir and nirmatrelvir/ritonavir in patients with impaired humoral immunity and persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection. Hematol Oncol 2023; 41:904–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wada D, Nakamori Y, Maruyama S, et al. Novel treatment combining antiviral and neutralizing antibody-based therapies with monitoring of spike-specific antibody and viral load for immunocompromised patients with persistent COVID-19 infection. Exp Hematol Oncol 2022; 11:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mikulska M, Sepulcri C, Dentone C, et al. Triple combination therapy with 2 antivirals and monoclonal antibodies for persistent or relapsed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection in immunocompromised patients. Clin Infect Dis 2023; 77:280–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Focosi D, Maggi F, D’Abramo A, Nicastri E, Sullivan DJ. Antiviral combination therapies for persistent COVID-19 in immunocompromised patients. Int J Infect Dis 2023; 137:55–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.