Abstract

Objective:

We examined positive and negative religious coping as moderators of the relation between physical limitations, depression, and desire for hastened death among male inmates incarcerated primarily for murder.

Methods:

Inmates over the age of 45 years who passed a cognitive screening completed face-to-face interviews (N = 94; mean age = 57.7years; SD = 10.68). Multiple regression analyses included age, race/ethnicity, parole belief, physical health, positive or negative religious coping, and all two-way interactions represented by the product of health and a religious coping variable.

Results:

Older inmates and those who reported greater levels of positive religious coping endorsed fewer symptoms of depression, whereas those who reported greater levels of negative religious coping endorsed more symptoms of depression. Inmates who reported higher levels of depression endorsed a greater desire for hastened death. The effect of physical functioning on desire for hastened death is moderated by negative religious coping such that those who endorsed higher levels of negative religious coping reported a greater desire for hastened death.

Conclusions:

Examinations of religious/spiritual practices and mindfulness-based interventions in prison research have assumed a positive stance with regard to the potential impact of religious/spiritual coping on physical and mental health. The current findings provide cautionary information that may further assist in selection of inmates for participation in such interventions.

Keywords: religion/spirituality, depression, functional status, prison

Introduction

In the USA in 2009, a total of 1,613,740 inmates were in custody in either a state or federal prison, which is a 0.2% increase from 2008 (West and Sabol, 2010). The number of older adult inmates has quadrupled in the past 25 years as a result of demographic changes and increased sentence length. This trend is especially significant in the USA, which incarcerates more individuals per capita than any other nation (Wilper et al., 2009). Because of a life-time of poor health practices, older inmates are a group with disproportionally higher rates of health problems than the overall US population (Hammett et al., 2001; Loeb et al., 2007). Moreover, aging prisoners may experience greater social isolation and mental health difficulties, including depression (Mueller-Johnson and Dhami, 2010), making them a particularly vulnerable group. Depression contributes to the etiology, course, and morbidity associated with chronic disease (Chapman et al., 2005); hence, comorbid physical and mental health problems among aging inmates likely increase the costs of care within these cash-strapped facilities.

In 2008, the Pew Center on the States estimated that the annual average cost of care for geriatric inmates was $70,000, two to three times the cost of care for an inmate under the age of 50 years. Contributing to the high costs of care is the mismatch between the mental and physical health needs of older inmates with physical disabilities and the physical characteristics of prison facilities (Loeb and AbuDagga, 2006; Wilper et al., 2009). Mara (2002) noted that most prison facilities lack environmental supports (e.g., grab bars and lever handles in showers; height of sinks and counters; and distance to infirmary) necessary for older inmates that use wheelchairs or are in need of long-term care. Accessibility in prisons and lack of adherence to the Americans with Disabilities Act remains a problem, increasing the isolation of aging inmates (Gross, 2007).

Nearly 40% of state inmates 55 years and older have symptoms of mental health disorders (James and Glaze, 2006), and depression, guilt, worry, and psychological stress are common (Aday, 2003). Given these data, there is a growing need to identify ways that indigenous coping, such as religious/spiritual coping, may be harnessed to improve mental and physical health outcomes and, potentially, reduce cost of care for older inmates. The purpose of this study is to explore the relations between functional ability, religious/spiritual coping, and mental health including symptoms of depression and desire for hastened death.

There is growing evidence that positive religious/spiritual coping practices or mindfulness-based religious practice helps inmates cope with the prison experience (Chen et al., 2007; Clear and Sumter, 2002; Perelman et al., 2012; Samuelson et al., 2007). In a maximum-security prison in the Deep South, Perelman et al. (2012) examined the impact of 10-day Vipassana silent meditation retreats in comparison with a mindfulness-based 10-week group intervention. They reported that, over the course of l year, inmates in both groups reduced the number of behavioral infractions, but only the Vipassana group reported increased mindfulness and reduced mood disturbance. Neither group was found to have fewer health visits within the facility. Among male federal prison inmates over the age of 50 years, 37% with a history of psychiatric treatment, Koenig (1995) reported that approximately one-third claimed religion was their most important coping method and that lower levels of depression were associated with greater attendance at religious services and higher levels of intrinsic religiousness.

Not all effects of religious/spiritual coping are positive (Hill, 2010). In their meta-analysis of religious coping practices and psychological adjustment to stress among community-dwelling adults, Ano and Vasconcelles (2005) reported that positive forms of religious coping are associated with positive psychological adjustment, whereas negative religious coping (e.g., spiritual discontent, passive religious deferral, re-appraisal of God’s powers, and punishing God re-appraisal) results in negative emotional adjustment. Allen et al. (2008) reported that older male inmates who reported feeling abandoned by God also reported more symptoms of depression and greater desire for hastened death, whereas those describing greater daily spiritual experiences reported fewer symptoms of depression and less desire for hastened death. Fernander et al. (2005) underscore the multivariate nature and varying patterns of association between religiosity/spirituality and offense history among adult male inmates.

Ellison (1994) and Ellison et al. (2001) provide empirical support for a conceptual framework regarding the mechanisms through which religious/spiritual coping may influence mental health. First, religious/spiritual coping and behaviors may reduce stress. Second, engagement in religious/spiritual behaviors may provide a social support network of like-minded persons, also contributing to the enhancement of psychological resources. The experience and expression of forgiveness may have particular salience in the prison setting (Randall and Bishop, 2012). Hill (2010) provided a useful biopsychosocial model in which aspects of positive and negative religiosity/spirituality act as moderators in the relation between physical disability and emotional health. Combining our pilot findings (Allen et al., 2008) with the theoretical predictions of prior models (Ellison, 1994; Ellison et al., 2001; Hill, 2010), we hypothesized that the relation between physical disability (as measured by functional status) and emotional states (e.g., depression and desire for hastened death) would depend upon certain religious/spiritual coping patterns. Specifically, we predicted significant interactions between functional status and positive religious coping such that inmates with more positive coping strategies would report fewer symptoms of depression and less desire for hastened death regardless of their functional ability. With regard to negative religious coping, we predicted that the negative impact of disability (e.g., poor functional status) would be exacerbated by negative religious coping in relation to symptoms of depression and desire for hastened death. Previous data from this study have been published elsewhere (Phillips et al., 2011).

Methods

Setting and participants

Data collection occurred at Hamilton Aged and Infirmed Prison (Hamilton A & I)—Alabama’s primary institution for incarcerated older men. Hamilton A & I is a medium-security prison of approximately 300 inmates. Working with the Alabama Department of Corrections (e.g., Dr Ronald Cavanaugh) and staff at Hamilton A&I, a convenience sample of all inmates above the age of 45 years that also reported a chronic illness were approached for consent.

Because Hamilton A&I is the designated state prison in Alabama for the aged and infirmed, all inmates routinely interacted with or observed other inmates with physical limitations, using wheelchairs or walkers, having feeding tubes, or experiencing cognitive decline. Infirmed inmates could be observed within public areas such as the mess hall or yard, and the dorms at Hamilton A&I consist of double bunks in large open areas rather than individual cells. Inmates often commented during interviews about experiences with infirmed inmates, suggesting an awareness of other frail inmates’ health.

Ninety-four inmates over the age of 45 years passed a cognitive screening examination consisting of the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE; Folstein et al., 1975) as an initial screening instrument and the Wide Range Achievement Test (WRAT; Wilkinson, 1993) as a measure of literacy. The mean age of participants was 57.7 years (SD = 10.68). Fifty-seven inmates (61%) were incarcerated for their first offense, and 37 (39%) were repeat offenders. Length of incarceration data were available for 63 inmates, with a range of 1 to 297 months (e.g., 24.75 years) and a mean of 25.6 months (SD = 37.67). Of the 94 inmates, 42 (44.7%) did not believe they would receive parole, and 52 (55.3%) believed they would be paroled. Of those who believed they would not be paroled, 29 (30.9% of total) were Caucasian, and 13 (13.8% of total) self-identified as a member of a minority group (mostly African-American). Among those who believed they would be paroled, 30 (31.9% of total) identified as Caucasian, and 22 (23.4% of total) as a member of a minority group (mostly African-American). Years of education differed between Caucasians and the minority group (F[1,91] = 7.57, p< 0. 01), with those self-identified as Caucasian reporting fewer years of education. However, there were no significant differences between the racial/ethnic groups for cognitive status or reading ability. Minority inmates were significantly more likely to be repeat offenders, Chi-square [1, N = 94] = 5.20, p = 0.02.

Measures

Mini-mental status examination (Folstein et al., 1975).

The MMSE, a well-validated measure with test–retest correlations of 0.80 to 0.95 (Tombaugh and McIntyre, 1992), was used as a cognitive screen. Education-adjusted scores below 24 indicate cognitive impairment (Tombaugh and McIntyre, 1992). Although there are no nationally available data on MMSE scores among prison inmates, Loeb et al. (2010) found an average MMSE score of 27.8 in a sample of 131 male inmates 50 years and older. In our prior research in the current setting (Phillips et al., 2009), we found an average MMSE between 25 and 27.

Wide Range Achievement Test (Wilkinson, 1993).

The WRAT reading subtest assesses ability to pronounce 42 words out of context. Standard scores range from less than 45 to above 155, with higher scores indicating higher achievement. Cronbach’s α range between 0.90 and 0.95, test–retest reliability ranges from 0.91 and 0.98.

Demographics.

We assessed basic demographic information including age, self-reported ethnicity, reason for incarceration, past convictions, and expectations regarding parole (yes/no).

Functional status items from the Medical Outcomes Survey (MOS) 36-item short-form health survey 1.0 (MOS SF-36; Ware and Sherbourne, 1992).

Inmates completed eight items that assess physical functioning with a resultant Cronbach’s α = 0.92. Three alterations were made in accordance with Walters et al. (2001): the order of the physical items was reversed so that the least demanding activity was given first, wording regarding work or home was changed to reflect the prison setting, and two items were omitted that were not applicable to this prison (i.e., no stairs). Participants reported their limitations in physical functioning on a three-point scale. Response options included 0 = Yes, limited a lot, 50 = Yes, limited a little, and 100 = Not limited at all. For this study, the two response options indicating the presence of physical limitations were collapsed. Scores on this measure range from 0 to 800, such that higher scores represent better health.

Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness and Spirituality (Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Work Group, 1999).

This study used two indices from the Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness and Spirituality. For each index, inmates responded on a four-point scale ranging from 1 = A great deal to 4 = Not at all. Items were recoded such that a higher score indicated greater use of each construct.

The Positive Religious Coping index (3 items; α = 0.80) addressed “benevolent religious methods of understanding and dealing with life stressors” (Fetzer/NIA, 1999, p. 43). Items included: “I think about how my life is part of a larger spiritual force,” “I look to God for strength, support and guidance in crises,” and “I work together with God as partners to get through hard times.” Two items formed the Negative Religious Coping scale (α = 0.64): “I wonder whether God has abandoned me” and “I feel God is punishing me for my sins or lack of spirituality.”

Duke University Religion Index (Koenig et al., 1997).

The five-item Duke University Religion Index measures aspects of religiosity that are related to health outcomes but avoid direct conceptual overlap with mental health (e.g., well-being). Organizational religious activities (e.g., “How often do you attend church or other religious meetings?”) was measured on a 6-point scale ranging from Never to More than once a week. Non-organizational religious practices (e.g., “How often do you spend time in private religious activities, such as prayer, meditation, or bible study?”) was measured on a 6-point scale ranging from Rarely or never to More than once a day. The remaining three items contain response options ranging from Definitely true to Definitely not true and were selected from Hoge’s 10-item intrinsic scale (Hoge, 1972) and averaged to create a measure of intrinsic religiousness.

Hastened Death Scale-Modified (Rosenfeld et al., 1999).

The Hastened Death Scale-Modified is a 12-item scale for assessing patients with a terminal illness (range 0–12). For this study, the questionnaire was altered by replacing the word “cancer” or “illness” with “in prison” so that the instrument measured the influence being in prison had on desire for a hastened death (Allen et al., 2008). Inmates endorse whether they think each statement is true or false. Example items include: “Dying seems like the best way to relieve the pain and discomfort of being in prison,” and “I expect to suffer a great deal from physical problems in the future because I am in prison.” Cronbach’s α in the current sample is 0.82.

Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977).

Frequency of depressive symptoms within the past week was assessed using the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D); scores range from 0 to 60 with higher scores indicating more symptoms of depression, with Cronbach’s α between 0.86 and 0.89.

Procedure

This study was approved by The University of Alabama Institutional Review Board. Measures were administered in interview format. Potential participants were given an informed consent explaining the nature of the study. If the inmate agreed to participate, the interviewer administered the MMSE and the reading subtest of the WRAT. Because of low literacy rates among inmates, if the participant scored below 15 (Newman, 2003) on the education-adjusted MMSE or was unable to read, the interview ended, and he was thanked for his time; if he scored a 15 or higher, informed consent was obtained, and the interview proceeded (Allen et al., 2008; Phillips et al., 2011; Phillips et al., 2009). Interviews lasted 60 to 90 min, and inmates were debriefed after completing the measures. The Alabama Department of Corrections does not permit compensation to inmates for participation in research.

Data analysis

Prior to descriptive and inferential analyses, each variable was evaluated for normality, missing data, and outliers to ensure all assumptions were met for each statistical test. There was a small amount of missing data in the data set (no variable had more than three missing values, and no inmate failed to respond to more than two items) that was replaced using the Expectation Maximization algorithm.

Two regression models examined variables associated with symptoms of depression (Model 1) and desire for hastened death (Model 2) among older male prison inmates in accordance with hypotheses generated by Hill’s (2010) biopsychosocial model. For each of these analyses, age, race/ethnicity, parole belief, functional status, and each spirituality variable (i.e., positive religious coping and negative religious coping) were included. CES-D was added as an independent variable for Model 2 examining desire for hastened death, as such desire is a precursor for depressive symptoms. In addition, the main effects of functional status and two terms for the interaction of functional status with each spirituality variable were added to both models. Continuous predictor variables were centered prior to data analyses.

Results

The average MMSE score was 25.18 (SD = 3.60; range 15 to 30), and mean WRAT scaled reading score was 79.97 (SD = 22.86; range 0 to 120). The average number of years of education was 11.09 (SD = 3.25). All but one participant were willing to report the type of crime for which they had been sentenced, with the majority reporting murder (n = 39, 41.5%), followed by financial offense (n = 20, 21.3%), sexual offense (n = 19, 20.5%), drug offense (n = 10, 10.6%), and other offenses (e.g., arson and assault; n = 5, 5.3%). Table 1 provides descriptive information by race/ethnicity regarding inmate organizational and non-organizational religiosity. Within Hamilton A&d, all inmates are allowed to have a religious text of their choosing, even in solitary confinement. Religious services are held every weekend. Table 2 displays inmate responses on the Medical Outcomes Survey 36-item short-form health survey 1.0, indicating the degree of physical limitations in the current sample.

Table 1.

Response frequencies for organizational and non-organizational Duke University Religion Index items

| How often do you attend church or other religious meetings? | How often do you spend time in private religious activities, such as prayer, meditation, or bible study? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Caucasian | Minority | Caucasian | Minority | ||

|

| |||||

| Never | 27.1 | 27.3 | Rarely or never | 15.3 | 3.0 |

| Once a year or less | 10.2 | 0.0 | A few times a month | 8.5 | 9.1 |

| Few times a year | 8.5 | 15.2 | Once a week | 1.7 | 12.1 |

| Few times a month | 18.6 | 39.4 | Two or more times a week | 22.0 | 15.2 |

| Once a week | 20.3 | 3.0 | Daily | 20.3 | 15.2 |

| More than once a week | 15.3 | 15.2 | More than once a day | 32.2 | 45.4 |

Table 2.

Response frequencies for functional status items from the Medical Outcomes Survey 36-item short-form health survey 1.0

| Item | Response | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Yes, limited (a lot or a little) | Not limited at all | |

|

| ||

| Bathing or dressing yourself | 24 (25.5) | 70 (74.5) |

| Bending, kneeling, or stooping | 65 (69.1) | 29 (30.9) |

| Lifting or carrying something weighing 5–10 lbs | 34 (36.2) | 60 (63.8) |

| Walking one lap | 40 (42.6) | 54 (57.4) |

| Walking a couple of laps | 41 (43.6) | 53 (56.4) |

| Moderate activities, such as mopping or other chores | 51 (54.3) | 43 (45.7) |

| Walking more than a mile | 56 (59.6) | 38 (40.4) |

| Vigorous activities, such as running, lifting heavy objects, and participating in strenuous sports | 73 (77.7) | 21 (22.3) |

Participants were asked, “The following questions are about activities you might do during a typical day. Does your health now limit you in these activities? If so how much?”

Number outside parentheses represents the frequency of the response option (out of N = 94).

Number inside parentheses represents percent of sample.

Table 3 depicts the results for both models. Model 1 (predicting CES-D) was significant, F(8, 82) = 5.32, p 0.001, R2 = 0.34, adjusted R2 = 0.28. Older inmates and those who reported greater levels of positive religious coping endorsed fewer symptoms of depression, whereas those who reported greater levels of negative religious coping endorsed more symptoms of depression. Contrary to hypotheses, interactions with functional status failed to reach significance.

Table 3.

Full models predicting depression and desire for hastened death

| Model 1 predicting CES-D | Model 2 predicting desire for hastened death | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| β | β | |

|

| ||

| Age | −0.21* | 0.11 |

| Race/ethnicity | −0.05 | 0.03 |

| Parole belief | −0.02 | −0.10 |

| Health | −0.16 | 0.00 |

| CES-D | — | 0.40** |

| BMMRS positive | −0.32** | 0.03 |

| BMMRS negative | 0.37** | 0.03 |

| Health × BMMRS positive | 0.02 | −0.05 |

| Health × BMMRS negative | 0.08 | −0.26* |

| Model adjusted R2 | 0.28** | 0.15** |

CES-D, Centers for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; BMMRS, Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness and Spirituality.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01.

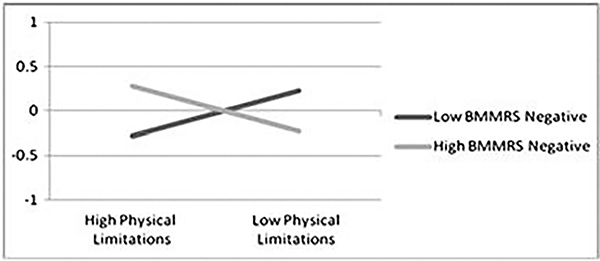

Model 2 (predicting desire for hastened death) was significant, F(9, 79) = 2.76, p = 0.007, R2 = 0.24, adjusted R2 = 0.15. Inmates who reported higher levels of depression endorsed a greater desire for hastened death. The interaction of functional status and negative religious coping was significant, indicating that the effect of physical functioning on desire for hastened death is moderated by negative religious coping. Among inmates with a high level of physical limitations, those who endorsed higher levels of negative religious coping reported a greater desire for hastened death than those with a low level of negative religious coping (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Moderating effect of BMMRS negative coping on the relation of health and desire for hastened death. The Y-axis represents desire for hastened death standard scores where M = 0 and SD = 1. BMMRS, Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness and Spirituality.

Discussion

Using the conceptual framework of Ellison (1994) and Ellison et al. (2001) as well as Hill’s (2010) biopsychosocial model, our findings expand upon prior research examining the role of religious/spiritual coping among male prison inmates (Allen et al., 2008; Clear and Sumter, 2002; Koenig, 1995; Perelman et al., 2012; Samuelson et al., 2007). Specifically, we found support for the importance of distinguishing between positive and negative religious coping strategies as they relate to emotional health, but failed to find strong support for Hill’s (2010) prediction of a moderating effect for religiousness/spirituality in the relation between physical and mental health.

As can be seen in Table 1, Caucasian and minority inmates reported relatively high levels of organizational and non-organizational religious engagement. Both positive and negative religious coping were related to report of depressive symptoms in the expected directions; however, neither type of religious coping strategy interacted with health (see Table 3). As suggested in prior research (Ellison et al., 2001; Randall and Bishop, 2012), it could be that religiousness/spirituality exert the most powerful influence by enhancing social support among inmates and improving positive psychological states. The particular impact of forgiveness and forgiveness therapy (e.g., Randall and Bishop, 2012) as well as meditation programs such as Vipassana or mindfulness (Perelman et al., 2012) as they relate to physical health care costs, behavioral infractions, and positive emotional experiences should be investigated in future research. Practitioners in the area of corrections should investigate these ongoing therapeutic programs as models for potential implementation within their own facilities.

As expected, depression was also significant in the model for desire for hastened death, as was the interaction between negative religious coping and functional status. Inmates’ report of desire for hastened death was enhanced when they reported both physical limitation and greater use of negative religious coping. Hill (2010) and other authors (Allen et al., 2008; Ano and Vasconcelles, 2005; Fernander et al., 2005) have noted the importance of including negative religious coping patterns in the examination of relations of religious/spiritual coping and physical and mental health.

It is noteworthy that most of the examinations of religious/spiritual practices and mindfulness-based interventions in prison research have assumed a primarily positive stance with regard to the potential impact of religious/spiritual coping on physical and mental health (Perelman et al., 2012; Samuelson et al., 2007). The current findings provide cautionary information for practitioners in the area of corrections that may further assist in selection of inmates for participation in such interventions. In addition to examining rates of prison infractions and segregation time (e.g., Perelman et al., 2012), perhaps inmates should be assessed for suitability for such programs based on use of negative religious coping beliefs. This would provide additional protections for inmates and, potentially, enhance intervention outcomes over and above relying on inmates’ self-selection into such interventions.

Descriptive information regarding functional limitations in this sample (Table 2) also provides useful information for the design of religious coping and mindfulness-based interventions for use within an older male inmate population. A disconnect currently exists between adult developmental and aging research on the increased reliance of older individuals on religious/spiritual coping and interventions within the correctional system. The evidence-based religious/spiritual interventions within correctional facilities reported by Perelman et al. (2012) and Samuelson et al. (2007) assume relative physical agility and stamina on the part of participants. Future research should focus on adaptations of these evidence-based interventions for use by the burgeoning number of older prison inmates.

As with any research, our study has limitations primarily reflected in sample selection and choice of instruments. First, these findings are based on surveys conducted with inmates over the age of 45 years at a single, medium-security state prison in the Deep South. It may be that inmates in this geographic setting endorse greater religious/spiritual coping than inmates in other facilities across the USA. Similar to any prison research, volunteer bias may have played a role in the findings; only inmates willing to talk about religious/spiritual coping and topics such as desire for hastened death participated. Additionally, the inmates in this study reported relatively low rates of depressive symptoms and desire for hastened death, limiting our ability to find significant associations cross-sectionally. Finally, our selection of measures may have limited our ability to detect true associations. For example, our measure of physical functioning was limited to self-reported functional status; objective measures of health status would expand upon our current findings.

Despite these limitations, our findings extend prior research examining religious/spiritual coping among older male inmates, particularly with regard to the impact of negative religious coping practices. With the increasing number of older inmates within the USA and internationally, cost effective interventions must be designed to improve physical and emotional functioning and quality of life. Religious/spiritual coping and mindfulness-based interventions represent a potentially useful and developmentally appropriate tool to accomplish this goal. Future research should focus on the adaptation and implementation of such evidence-based programs with physically frail and older male prison inmates.

Key points.

The population of aged and aging prison inmates is growing internationally, but particularly in the USA.

Indigenous coping, such as religious/spiritual coping patterns, may be harnessed to improve physical and emotional health outcomes and, potentially, reduce cost of care within the prison system.

In this study, negative religious coping moderated the relation between physical disability and emotional health among male inmates.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R36 HS016218-01) to L. L. Phillips and by the Center for Mental Health and Aging at The University of Alabama as part of Laura Phillips’ doctoral dissertation in the Department of Psychology. Special thanks are extended to Margaret Ege for assistance in data collection and to all of the inmates, correctional officers, and staff (particularly Warden Butler, Laura Day, and Officer Scott) at the Hamilton Aged and Infirmed Correctional Facility who gave their time and energy to this project.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- Aday RH. 2003. Aging Prisoners: Crisis in American Corrections. Praeger: Westport, CT. [Google Scholar]

- Allen RS, Phillips LL, Rolf LL, Cavanaugh R, Day L. 2008. Religiousness/spirituality and mental health among older male inmates. Gerontologist 48: 692–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ano GG, Vasconcelles EB. 2005. Religious coping and psychological adjustment to stress: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol 61(4): 461–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman DP, Perry GS, Strine TW. 2005. The vital link between chronic disease and depressive disorders. Prev Chronic Dis 2: 1–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Cheal K, Herr ECM, Zubritsky C, Levkoff SE. 2007. Religious participation as a predictor of mental health status and treatment outcomes in older persons. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 22: 144–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clear TR, Sumter MT. 2002. Prisoners, prison, and religion: religion and adjustment to prison. J Offender Rehabil 35(3–4): 127–159. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG. 1994. Religion, the life stress paradigm, and the study of depression. In Religion in Aging and Health: Theoretical Foundations and Methodological Frontiers, Levin JS (ed.). Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA; 78–121. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Boardman AG, Williams DR, Jackson JS. 2001. Religious involvement, stress, and mental health: findings from the 1995 Detroit area study. Soc Forces 80(1): 215–249. [Google Scholar]

- Fernander A, Wilson JF, Staton M, Leukefeld C. 2005. Exploring the type-of-crime hypothesis, religiosity and spirituality in an adult male prison population. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 49: 682–695, DOI: 10.1177/0306624X05274897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Work Group. 1999. Multidimensional Measurement of Religiousness/Spirituality for Use in Health Research. John E. Fetzer Institute: Kalamazoo, MI. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh RR. 1975. Mini-mental state: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12: 189–198, DOI: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross B 2007. Elderly offenders: implications for corrections personnel. Forensic Examiner 16(1): 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Hammett TM, Roberts C, Kennedy S. 2001. Health-related issues in prisoner reentry. Crime Delinq 47: 390–409, DOI: 10.1177/0011128701047003006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill TD. 2010. A biopsychosocial model of religious involvement. Annu Rev Gerontol Geriatr 30(1): 179–199. Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Hoge DR. 1972. A validated intrinsic religious motivation scale. J Sri Study Relig 11: 369–376. [Google Scholar]

- James DJ, Glaze LE. 2006. Mental Health Problems of Prison and Jail Inmates. Bureau of Justice Statistics: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG. 1995. Religion and older men in prison. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 10: 219–230. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Parkerson GR, Meador KG. 1997. Religion index for psychiatric research. Am J Psychiatry 154: 885–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb SJ, AbuDagga A. 2006. Health-related research on older inmates: an integrative review. Res Nurs Health 29: 556–565, DOI: 10.1002/nur.20177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb SJ, Steffensmeier D, Myco PM. 2007. In their own words: older male prisoners’ health beliefs and concerns for the future. Geriatr Nurs 28: 319–329, DOI: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2007.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb SJ, Steffensmeier D, Kassab C. 2010. Predictors of self-efficacy and self-rated health for older male inmates. J Adv Nurs 67: 811–820, DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05542.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mara CM. 2002. Expansion of long-term care in the prison system. J Aging Soc Policy 14(2): 43–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller-Johnson KU, Dhami MK. 2010. Effects of offenders’ age and health on sentencing decisions. J Soc Psychol 150(1): 77–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman J 2003, November. Information processing deficits in psychopathic offenders: implications for self-regulation and violence. Paper presented at the University of Alabama Psychology Colloquium Series, Tuscaloosa, AL. [Google Scholar]

- Perelman AM, Miller SL, Clements CB, et al. 2012. Meditation in a Deep South prison: a longitudinal study of the effects of Vipassana. J Offender Rehabil 51(3): 176–198. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Center on the States. 2008. One in 100: behind bars in America 2008. Retrieved June 11, 2010 from http://www.pewcenteronthestates.org/uploaded-Files/8015PCTS_Prison08_FINAL_2-1-1_FORWEB.pdf.

- Phillips LL, Allen RS, Salekin KL, Cavanaugh R. 2009. Care alternatives in prison systems: factors influencing end-of-life treatment selection. Crim Justice Behav 36(6): 620–634, DOI: 10.1177/0093854809334442 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips LL, Allen RS, Harris GM, et al. 2011. Aging prisoners’ treatment selection: does prospect theory enhance understanding of end-of-life medical decisions? Gerontologist 51: 663–674, DOI: 10.1093/geront/gnr039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. 1977. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas 1: 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Randall GK, Bishop AJ. 2012. Direct and indirect effects of religiosity on valuation of life through forgiveness and social provisions among older incarcerated males. Gerontologist 52, DOI: 10.1093/geront/gns070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W, Stein K, et al. 1999. Measuring desire for death among patients with HIV/AIDS: the schedule of attitudes toward hastened death. Am J Psychiatry 156: 94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson M, Carmody J, Kabat-Zinn J, Bratt MA. 2007. Mindfulness-based stress reduction in Massachusetts correctional facilities. Prison J 87: 254–268. [Google Scholar]

- Tombaugh TN, McIntyre NJ. 1992. The mini-mental state examination: a comprehensive eview. J Am Geriatr Soc 40: 922–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters SJ, Munro JF, Brazier JE. 2001. Using the SF-36 with older adults: a cross-sectional community-based survey. Age Ageing 30: 337–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. 1992. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care 30: 473–83, DOI: 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West HC, Sabol WJ. 2010. Bulletin: prisoners in 2009. (Report No. NCJ231675). Retrieved from U. S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, website: http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&did=2232 [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson GS. 1993. The Wide Range Achievements Test - Third Edition (WRAT-III). Wide Range Inc.: Wilmington, Delaware. [Google Scholar]

- Wilper AP, Woolhandler S, Boyd JW, et al. 2009. The health and health care of US prisoners: results of a nationwide survey. Am J Public Health 99(4): 666–672, DOI: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.144279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]