Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had an unprecedented impact on the delivery of surgery1. Recent estimates in Canada point to a ‘procedure gap’ of nearly 937 000 during the first 31 months of the pandemic, with one province accounting for nearly a third of this gap2. Addressing this procedure gap is a public health priority.

Before the pandemic, a third of Canadian patients exceeded wait time targets for common scheduled surgeries3. Prior research suggests that structural barriers limited access to surgery for certain subgroups, despite a universal healthcare system. Individuals from marginalized communities were more likely to experience: delayed cancer and emergency surgery4,5; greater pain after cancer surgery6; and deferred surgical care7.

The disproportionate impact of the pandemic on marginalized populations in terms of COVID-19 hospitalization, death, and quality of life is well documented8. Whether at-risk communities also experienced diminished surgery rates is unknown; understanding this impact will inform policy for an equitable surgical recovery.

The objective of this study was to determine surgery rates during the COVID-19 pandemic for subgroups with a risk of impaired surgical access; the hypothesis was that the rates of scheduled surgery would be lower for communities with fewer material resources, older patients, those with co-morbid disease, female patients, and immigrant and refugee populations.

Methods

A population-based repeated cross-sectional study of rates of scheduled surgery for all adults (greater than or equal to 18 years or older) living in Ontario9, between January 2017 and March 2023, was conducted. The ‘pre-COVID-19 interval’ was between January 2017 and February 2020. The ‘COVID-19 interval’ began in March 2020 and included the remainder of the study interval.

In this study, health administrative databases were linked using unique encoded identifiers and analysed at ICES (Appendix S1)10. ICES is an independent, non-profit research institute that houses health administrative data in Ontario and whose legal status under Ontario’s health information privacy law allows it to collect and analyse healthcare and demographic data, without consent, for health system evaluation and improvement10.

The most common non-obstetrical, non-cancer surgeries were included: inguinal hernia repair, cholecystectomy, hip or knee replacement, cataract removal, hysterectomy, or transurethral resection of the prostate (Appendix S2)11.

Several at-risk subgroups were identified (Supplementary Materials), including individuals residing in areas with lower material resources based on the validated Ontario Marginalization Index12, older patients, those with a high co-morbidity burden based on the Johns Hopkins ACG system13, female patients, and immigrant or refugee populations.

Monthly rates of procedures per 1000 persons were generated, using the corresponding population on 1 January of each year as the denominator. To measure relative changes in surgery rates during the COVID-19 interval, Poisson generalized estimating equations were used to model pre-COVID-19 trends and these were used to forecast expected COVID-19 procedure rates14,15. Yearly procedure rates between levels of each measure were compared by assigning Duncan groupings of rate ratios for each level and using t tests to compare each level with the reference14.

Results

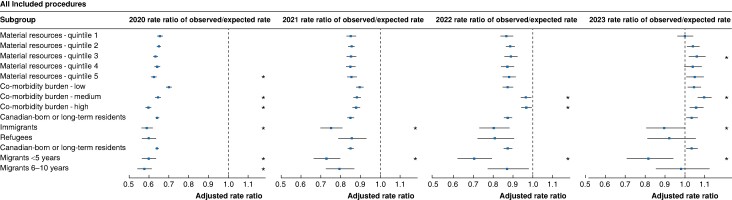

Relative procedure rates were lower in 2020, 2021, and 2022 for all subgroups (Fig. 1) compared with the pre-COVID-19 interval. In 2023, relative procedure rates were the same as or higher than pre-COVID-19 for all subgroups except immigrants (adjusted rate ratio (aRR) 0.90 (95% c.i. 0.80 to 0.99), P = 0.040) and recent migrants (aRR 0.82 (95% c.i. 0.71 to 0.94), P < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Adjusted rate ratios of observed procedure rates over expected procedure rates, by each access measure, for each year of the COVID-19 interval compared with pre-COVID-19 rates for all procedures

An asterisk denotes a difference in the observed to expected rate ratio for the level of access compared with the reference level for the specified year (for example material resources – quintile 5 compared with material resources – quintile 1 as the reference).

In 2020, lower procedure rates were observed for those with the least material resources (quintile 5) compared with the most material resources (quintile 1) and those with medium and high co-morbidity burden compared with low co-morbidity (Table 1 and Table S1). These differences did not persist in subsequent years. Procedure rates for immigrants (aRR 0.92 (95% c.i. 0.88 to 0.97), P < 0.001) and recent migrants (aRR 0.92 (95% c.i. 0.86 to 0.98), P = 0.008) were low in 2020 compared with Canadian-born or long-term residents; these low rates persisted in 2021 (immigrants aRR 0.88 (95% c.i. 0.82 to 0.94), P < 0.001; recent migrants aRR 0.85 (95% c.i. 0.77 to 0.93), P < 0.001), 2022 (recent migrants aRR 0.82 (95% c.i. 0.72 to 0.93), P = 0.001), and 2023 (immigrants aRR 0.86 (95% c.i. 0.77 to 0.97), P = 0.011; recent migrants aRR 0.80 (95% c.i. 0.69 to 0.92), P = 0.002).

Table 1.

Adjusted rate ratio (95% c.i.) of observed to expected procedure rates for each level of measure

| Subgroup | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material resources* - quintile 1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Material resources - quintile 2 | 1.00 (0.98,1.02) | 1.01 (0.98,1.04) | 1.03 (0.98,1.07) | 1.04 (0.99,1.09) |

| Material resources - quintile 3 | 0.98 (0.95,1.00) | 1.01 (0.97,1.05) | 1.03 (0.98,1.08) | 1.06 (1.00,1.12) |

| Material Resources - quintile 4 | 0.99 (0.96,1.02) | 1.00 (0.97,1.04) | 1.01 (0.96,1.06) | 1.04 (0.98,1.10) |

| Material resources - quintile 5 | 0.97 (0.94,0.99) | 1.02 (0.98,1.05) | 1.03 (0.98,1.08) | 1.05 (0.99,1.11) |

| Co-morbidity burden† - low | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Co-morbidity burden - medium | 0.93 (0.91,0.94) | 0.99 (0.96,1.02) | 1.11 (1.07,1.15) | 1.05 (1.00,1.09) |

| Co-morbidity burden - high | 0.86 (0.85,0.88) | 0.99 (0.96,1.02) | 1.12 (1.08,1.16) | 1.01 (0.97,1.06) |

| Canadian-born or long-term residents | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Immigrants | 0.92 (0.88,0.97) | 0.88 (0.82,0.94) | 0.92 (0.83,1.01) | 0.86 (0.77,0.97) |

| Refugees | 0.95 (0.89,1.01) | 1.02 (0.93,1.11) | 0.93 (0.83,1.05) | 0.90 (0.78,1.03) |

| Canadian-born or long-term residents | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Migrants <5 years | 0.92 (0.86,0.98) | 0.85 (0.77,0.93) | 0.82 (0.72,0.93) | 0.80 (0.69,0.92) |

| Migrants 6–10 years | 0.91 (0.85,0.97) | 0.94 (0.86,1.03) | 1.00 (0.89,1.13) | 0.94 (0.82,1.08) |

Analyses limited to outpatient procedures reflected differences observed for all procedures (Fig. S1 and Table S2). By 2022, there was evidence of recovery of outpatient procedure rates for all groups except immigrants (aRR 0.85 (95% c.i. 0.78 to 0.92), P < 0.001) and recent migrants (aRR 0.72 (95% c.i. 0.63 to 0.83), P < 0.001) compared with pre-COVID-19. In 2023, rates of surgery were at or higher than pre-COVID-19 rates for all groups except recent migrants (aRR 0.84 (95% c.i. 0.72 to 0.98), P = 0.03).

Though lower rates of outpatient surgery were observed in 2020 for those with fewer material resources (quintile 5 versus quintile 1) and those with medium and high co-morbidity compared with low co-morbidity, these differences did not persist later. Outpatient procedure rates were lower for immigrants and recent migrants in 2020 compared with Canadian-born or long-term residents; these effects persisted in 2021, 2022, and 2023.

Results of analyses assessing age and sex differences, and procedures rates and differences for inpatient and outpatient surgery and for cataract and non-cataract surgery are presented in the Supplementary material.

Discussion

Immigrants and recent migrants consistently experienced lower surgery rates compared with long-term residents throughout the pandemic, suggesting worsening procedure gaps. Conversely, elderly patients and those with co-morbid disease initially experienced decreased rates of surgery, but demonstrated recovery to pre-pandemic levels by 2023. Though a backlog of procedures still exists, it is not worsening likely due to outpatient procedure recovery.

Early in the pandemic, preference was given to healthier patients to preserve hospital resources, with some traditionally inpatient procedures transformed to outpatient surgery for carefully selected patients16. These changes, in addition to patient choice and hospital avoidance, may have contributed to diminished rates of surgery for sicker patients early in the pandemic17.

Immigrants and recent migrants consistently experienced diminished rates of surgery, especially for outpatient and cataract procedures. Further research disentangling surgical access in the context of the broader immigrant experience, ascertaining factors such as limited social support, unstable employment, language barriers, and structural obstacles to access18, is warranted. Other health systems have pioneered partnerships between hospital systems and community organizations, and instituted alternative funding models to support comprehensive care19, both of which reduced surgical wait times in migrant communities.

Various strategies have been proposed to address the procedure gap, including weekend scheduled surgery20, single-entry models21, and expansion of for-profit outpatient facilities. For-profit surgical centres may preferentially perform low-risk surgery in low-risk patients, while diverting staffing from the existing system, thereby worsening existing barriers to access22. Equity considerations should inform surgical recovery strategies, prioritizing populations with persisting procedure gaps.

Despite capturing all selected publicly funded scheduled procedures, limitations exist, such as limited data on individual-level marginalization, changing patterns of travel and immigration during the pandemic, changes to care patterns negating rather than delaying surgery, and the intersection between measures of risk to surgical access. Despite these limitations, this study highlights population-level discrepancies in surgery rates, particularly for immigrant communities. Further research is needed to disentangle proximate causes of disparities to inform policy that supports equitable access to surgery.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This document used data adapted from the Statistics Canada Postal CodeOM Conversion File, which is based on data licensed from the Canada Post Corporation and/or data adapted from the Ontario Ministry of Health Postal Code Conversion File, which contains data copied under license from ©Canada Post Corporation and Statistics Canada. Parts of this material are based on data and/or information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), the Ontario Ministry of Health, Statistics Canada (census profile 2021), and Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) current to March 2022. The analyses, conclusions, opinions, and statements expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not reflect those of the funding or data sources; no endorsement is intended or should be inferred. The authors thank the Toronto Community Health Profiles Partnership for providing access to the Ontario Marginalization Index.

Contributor Information

Ashwin Sankar, Unity Health Toronto, St Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Department of Anaesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Temerty Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; ICES, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Therese A Stukel, ICES, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Institute of Health Policy, Management, and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Nancy N Baxter, ICES, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Department of Surgery, Temerty Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Duminda N Wijeysundera, Unity Health Toronto, St Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Department of Anaesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Temerty Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; ICES, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Institute of Health Policy, Management, and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Stephen W Hwang, Unity Health Toronto, St Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; ICES, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Andrew S Wilton, ICES, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Timothy C Y Chan, Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Vahid Sarhangian, Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Andrea N Simpson, Unity Health Toronto, St Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; ICES, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Charles de Mestral, Unity Health Toronto, St Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; ICES, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Department of Surgery, Temerty Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Daniel Pincus, ICES, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Department of Surgery, Temerty Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Robert J Campbell, ICES, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Department of Ophthalmology, Kingston Health Sciences Centre, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada.

David R Urbach, ICES, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Department of Surgery, Temerty Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Jonathan Irish, Department of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery and Surgical Oncology, University Health Network, University of Toronto, and Cancer Care Ontario—Ontario Health, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

David Gomez, Unity Health Toronto, St Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; ICES, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Department of Surgery, Temerty Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Funding

This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health (MOH) and the Ministry of Long-Term Care (MLTC). This study also received funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR; operating grant 202109-477229). This work was also supported by the Ontario Health Data Platform (OHDP), a Province of Ontario initiative to support Ontario’s ongoing response to COVID-19 and its related impacts.

Author contributions

Ashwin Sankar (Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Therese A. Stukel (Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Project administration, Validation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Nancy N. Baxter (Conceptualization, Supervision, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Duminda N. Wijeysundera (Conceptualization, Supervision, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Stephen W. Hwang (Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Andrew S. Wilton (Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Investigation), Timothy C. Y. Chan (Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Vahid Sarhangian (Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Andrea N. Simpson (Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Charles de Mestral (Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Daniel Pincus (Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Robert J. Campbell (Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), David R. Urbach (Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Jonathan Irish (Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), and David Gomez (Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing)

All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at BJS Open online.

Data availability

The data set from this study is held securely in coded form at ICES. While legal data sharing agreements between ICES and data providers (for example healthcare organizations and government) prohibit ICES from making the data set publicly available, access may be granted to those who meet pre-specified criteria for confidential access, available at www.ices.on.ca/DAS (e-mail: das@ices.on.ca). The full data set creation plan and underlying analytic code are available from the authors upon request, understanding that the computer programs may rely upon coding templates or macros that are unique to ICES and are therefore either inaccessible or may require modification.

References

- 1. Gomez D, Dossa F, Sue-Chue-Lam C, Wilton AS, de Mestral C, Urbach Det al. Impact of COVID 19 on the provision of surgical services in Ontario, Canada: population-based analysis. Br J Surg 2021;108:e15–e17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Canadian Institute for Health Information . Surgeries Impacted by COVID-19: An Update on Volumes and Wait Times. https://www.cihi.ca/en/surgeries-impacted-by-covid-19-an-update-on-volumes-and-wait-times (accessed 16 January 2024)

- 3. Schneider EC, Shah A, Doty MM, Tikkanen R, Fields K, Williams RD II. Mirror, Mirror 2021: Reflecting Poorly: Health Care in the U.S. Compared to Other High-Income Countries. 2021. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2021/aug/mirror-mirror-2021-reflecting-poorly (accessed 4 January 2024)

- 4. Helpman L, Pond GR, Elit L, Anderson LN, Seow H. Disparities in surgical management of endometrial cancers in a public healthcare system: a question of equity. Gynecol Oncol 2020;159:387–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Platt J, Baxter N, Zhong T. Breast reconstruction after mastectomy for breast cancer. CMAJ 2011;183:2109–2116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Parvez E, Chu M, Kirkwood D, Doumouras A, Levine M, Bogach J. Patient reported symptom burden amongst immigrant and Canadian long-term resident women undergoing breast cancer surgery. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2023;199:553–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Padwal RS, Chang HJ, Klarenbach S, Sharma AM, Majumdar SR. Characteristics of the population eligible for and receiving publicly funded bariatric surgery in Canada. Int J Equity Health 2012;11:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Escobar GJ, Adams AS, Liu VX, Soltesz L, Chen YFI, Parodi SMet al. Racial disparities in COVID-19 testing and outcomes: retrospective cohort study in an integrated health system. Ann Intern Med 2021;174:786–793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Statistics Canada . Estimates of the Components of Demographic Growth, Annual. 2018. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710000801 (accessed 8 February 2024)

- 10. Schull MJ, Azimaee M, Marra M, Cartagena RG, Vermeulen MJ, Ho Met al. ICES: data, discovery, better health. Int J Popul Data Sci 2020;4:1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Feinberg AE, Porter J, Saskin R, Rangrej J, Urbach DR. Regional variation in the use of surgery in Ontario. CMAJ Open 2015;3:E310–E316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moin JS, Moineddin R, Upshur REG. Measuring the association between marginalization and multimorbidity in Ontario, Canada: a cross-sectional study. J Comorb 2018;8:2235042X18814939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. The Johns Hopkins University ACG Case-Mix System. Baltimore: John Hopkins University, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Saunders N, Guttmann A, Brownell M, Cohen E, Fu L, Guan Jet al. Pediatric primary care in Ontario and Manitoba after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic: a population-based study. CMAJ Open 2021;9:E1149–E1158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schull MJ, Stukel TA, Vermeulen MJ, Zwarenstein M, Alter DA, Manuel DGet al. Effect of widespread restrictions on the use of hospital services during an outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome. CMAJ 2007;176:1827–1832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gleicher Y, Peacock S, Peer M, Wolfstadt J. Transitioning to outpatient arthroplasty during COVID-19: time to pivot. CMAJ 2021;193:E455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang J. Hospital avoidance and unintended deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Health Econ 2021;7:405–426 [Google Scholar]

- 18. OECD . What Has Been the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Immigrants? An Update on Recent Evidence. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/what-has-been-the-impact-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-on-immigrants-an-update-on-recent-evidence-65cfc31c/ (accessed 19 December 2023)

- 19. The King’s Fund . Tackling Health Inequalities on NHS Waiting Lists. 2023. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/health-inequalities-nhs-waiting-lists (accessed 16 January 2024)

- 20. Stephenson R, Sarhangian V, Park J, Sankar A, Baxter NN, Stukel TAet al. Evolution of the surgical procedure gap during and after the COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario, Canada: cross-sectional and modelling study. Br J Surg 2023;110:1887–1889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Urbach DR, Martin D. Confronting the COVID-19 surgery crisis: time for transformational change. CMAJ 2020;192:E585–E586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives . At What Cost?https://policyalternatives.ca/publications/reports/at-what-cost (accessed 16 January 2024)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data set from this study is held securely in coded form at ICES. While legal data sharing agreements between ICES and data providers (for example healthcare organizations and government) prohibit ICES from making the data set publicly available, access may be granted to those who meet pre-specified criteria for confidential access, available at www.ices.on.ca/DAS (e-mail: das@ices.on.ca). The full data set creation plan and underlying analytic code are available from the authors upon request, understanding that the computer programs may rely upon coding templates or macros that are unique to ICES and are therefore either inaccessible or may require modification.

References

- 1. Gomez D, Dossa F, Sue-Chue-Lam C, Wilton AS, de Mestral C, Urbach Det al. Impact of COVID 19 on the provision of surgical services in Ontario, Canada: population-based analysis. Br J Surg 2021;108:e15–e17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Canadian Institute for Health Information . Surgeries Impacted by COVID-19: An Update on Volumes and Wait Times. https://www.cihi.ca/en/surgeries-impacted-by-covid-19-an-update-on-volumes-and-wait-times (accessed 16 January 2024)

- 3. Schneider EC, Shah A, Doty MM, Tikkanen R, Fields K, Williams RD II. Mirror, Mirror 2021: Reflecting Poorly: Health Care in the U.S. Compared to Other High-Income Countries. 2021. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2021/aug/mirror-mirror-2021-reflecting-poorly (accessed 4 January 2024)

- 4. Helpman L, Pond GR, Elit L, Anderson LN, Seow H. Disparities in surgical management of endometrial cancers in a public healthcare system: a question of equity. Gynecol Oncol 2020;159:387–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Platt J, Baxter N, Zhong T. Breast reconstruction after mastectomy for breast cancer. CMAJ 2011;183:2109–2116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Parvez E, Chu M, Kirkwood D, Doumouras A, Levine M, Bogach J. Patient reported symptom burden amongst immigrant and Canadian long-term resident women undergoing breast cancer surgery. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2023;199:553–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Padwal RS, Chang HJ, Klarenbach S, Sharma AM, Majumdar SR. Characteristics of the population eligible for and receiving publicly funded bariatric surgery in Canada. Int J Equity Health 2012;11:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Escobar GJ, Adams AS, Liu VX, Soltesz L, Chen YFI, Parodi SMet al. Racial disparities in COVID-19 testing and outcomes: retrospective cohort study in an integrated health system. Ann Intern Med 2021;174:786–793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Statistics Canada . Estimates of the Components of Demographic Growth, Annual. 2018. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710000801 (accessed 8 February 2024)

- 10. Schull MJ, Azimaee M, Marra M, Cartagena RG, Vermeulen MJ, Ho Met al. ICES: data, discovery, better health. Int J Popul Data Sci 2020;4:1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Feinberg AE, Porter J, Saskin R, Rangrej J, Urbach DR. Regional variation in the use of surgery in Ontario. CMAJ Open 2015;3:E310–E316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moin JS, Moineddin R, Upshur REG. Measuring the association between marginalization and multimorbidity in Ontario, Canada: a cross-sectional study. J Comorb 2018;8:2235042X18814939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. The Johns Hopkins University ACG Case-Mix System. Baltimore: John Hopkins University, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Saunders N, Guttmann A, Brownell M, Cohen E, Fu L, Guan Jet al. Pediatric primary care in Ontario and Manitoba after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic: a population-based study. CMAJ Open 2021;9:E1149–E1158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schull MJ, Stukel TA, Vermeulen MJ, Zwarenstein M, Alter DA, Manuel DGet al. Effect of widespread restrictions on the use of hospital services during an outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome. CMAJ 2007;176:1827–1832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gleicher Y, Peacock S, Peer M, Wolfstadt J. Transitioning to outpatient arthroplasty during COVID-19: time to pivot. CMAJ 2021;193:E455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang J. Hospital avoidance and unintended deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Health Econ 2021;7:405–426 [Google Scholar]

- 18. OECD . What Has Been the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Immigrants? An Update on Recent Evidence. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/what-has-been-the-impact-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-on-immigrants-an-update-on-recent-evidence-65cfc31c/ (accessed 19 December 2023)

- 19. The King’s Fund . Tackling Health Inequalities on NHS Waiting Lists. 2023. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/health-inequalities-nhs-waiting-lists (accessed 16 January 2024)

- 20. Stephenson R, Sarhangian V, Park J, Sankar A, Baxter NN, Stukel TAet al. Evolution of the surgical procedure gap during and after the COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario, Canada: cross-sectional and modelling study. Br J Surg 2023;110:1887–1889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Urbach DR, Martin D. Confronting the COVID-19 surgery crisis: time for transformational change. CMAJ 2020;192:E585–E586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives . At What Cost?https://policyalternatives.ca/publications/reports/at-what-cost (accessed 16 January 2024)