Abstract

The PITSLRE kinases belong to the large family of cyclin-dependent protein kinases. Their function has been related to cell-cycle regulation, splicing and apoptosis. We have previously shown that the open reading frame of the p110PITSLRE transcript contains an IRES (internal ribosome entry site) that allows the expression of a smaller p58PITSLRE isoform during the G2/M stage of the cell cycle. In the present study we investigated further the role of cis- and trans-acting factors in the regulation of the PITSLRE IRES. Progressive deletion analysis showed that both a purine-rich sequence and a Unr (upstream of N-ras) consensus binding site are essential for PITSLRE IRES activity. In line with these observations, we demonstrate that the PITSLRE IRES interacts with the Unr protein, which is more prominently expressed at the G2/M stage of the cell cycle. We also show that phosphorylation of the α-subunit of the canonical initiation factor eIF-2 is increased at G2/M. Interestingly, phosphorylation of eIF-2α has a permissive effect on the efficiency of both the PITSLRE IRES and the ornithine decarboxylase IRES, two cell cycle-dependent IRESs, in mediating internal initiation of translation, whereas this was not observed with the viral EMCV (encephalomyocarditis virus) and HRV (human rhinovirus) IRESs.

Keywords: cap-independent translation, α-subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF-2α), G2/M cell-cycle stage, internal ribosome-entry-site (IRES)-specific trans-acting factor (ITAF), p58PITSLRE protein kinase, upstream of N-ras

Abbreviations: Apaf-1, apoptotic-protease-activating factor 1; Cat-1, cationic amino acid transporter protein 1; DTT, dithiothreitol; eIFs, eukaryotic initiation factors; eIF-2α, α-subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2; EMCV, encephalomyocarditis virus; FCS, fetal-calf serum; Fluc, firefly luciferase; hnRNP, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein; IL-3, interleukin-3; ITAF, IRES-specific trans-acting factor; HRV, human rhinovirus; IRES, internal ribosome entry site; ODC, ornithine decarboxylase; PARS, polypurine (A)-rich sequence; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; PKR, double-stranded-RNA-activated protein kinase; PKR-K296R, death mutant [Lys296→arginine]KPR; PTB, polypyrimidine-tract-binding protein; 5′-RACE, rapid amplification of cDNA ends; Rluc, Renilla luciferase; RRL, rabbit reticulocyte lysate; SV40, simian virus 40; Unr, upstream of N-ras (protein); 5′-UTR, 5′-untranslated region

INTRODUCTION

PITSLRE protein kinases are members of the large family of p34cdc2-related protein kinases that play key roles in normal cell cycle progression. Their name reflects the presence of an amino acid sequence that is a variation of the conserved PSTAIRE motif characteristic for all members of the cdc2-related protein kinase family. Because of their ability to bind cyclin L, they are also known as cyclin-dependent kinase 11 (CDK11). PITSLRE kinase homologues have been identified in various organisms, including the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, the nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans, the fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster, chicken, mouse and human, suggesting an important conserved function. Two distinct but closely related human PITSLRE kinase genes (cdc2L1 and cdc2L2) express several protein isoforms, mainly p110PITSLRE and p58PITSLRE isoforms. The p110PITSLRE isoforms contain at their C-terminal end the open reading frame of the p58PITSLRE isoform (reviewed in [1]). We have previously identified an IRES (internal ribosome entry site) in the open reading frame of the transcript coding for the p110PITSLRE protein kinase [2]. The PITSLRE IRES leads to the expression of the smaller isoform p58PITSLRE specifically during the G2/M stage of the cell cycle. A role for p58PITSLRE in G2/M has been suggested, as the kinase activity of p58PITSLRE is greatly enhanced upon cyclin D3 association in G2/M [3], and overexpression of p58PITSLRE in Chinese-hamster ovary fibroblasts leads to mitotic delay, abnormal cytokinesis, reduced rate of cell growth and apoptosis [4,5]. Therefore tightly regulated expression of p58PITSLRE, possibly through PITSLRE IRES-mediated translation of p58PITSLRE at G2/M, may be important for proper execution of cell-cycle progression.

IRESs are cis-acting elements, located mainly in the 5′-UTR (5′-untranslated region) of the mRNA, that allow cap-independent translation by directly landing the ribosomal subunit close to the initiator AUG. IRESs were originally discovered in picornaviruses and later in other viruses (reviewed in [6]). More recently, IRES sequences have been identified in a still growing number of cellular mRNAs. Interestingly, these IRESs are found preferentially in the mRNA of genes involved in the control of cellular proliferation, survival and death, and most of them are active under conditions which impair the general cap-dependent protein synthesis (reviewed in [7]). These include hypoxia, apoptosis, mitosis, viral infection and amino acid starvation, suggesting that IRES-mediated translation plays an important role in the regulation of cell fate by over-riding stress conditions. So far, a few IRESs that are active mainly during the G2/M stage of the cell cycle have been identified [2,8–15]. These include IRESs that are on cellular mRNA [as for instance c-myc, ODC (ornithine decarboxylase), PITSLRE, protein kinase Cδ (PKCδ), hSNM1 (human homologue of Saccharomyces cerevisiae sensitivity to nitrogen-mustard mutant), NAP1L1 (nucleosome assembly protein 1-like 1) and Drosophila hairless], as well as viral IRESes such as hepatitis C and HIV type I. Molecular mechanisms involved in cell-cycle-dependent internal initiation of translation are still elusive. So far, it has been reported only for the c-myc RNA that the hnRNP (heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein) C binds to the IRES element and modulates c-myc translation in a cell-cycle-phase-dependent manner [16]. Several RNA-binding proteins, designed ITAFs (non-canonical IRES-specific trans-acting factors), have been shown to regulate cellular IRES-dependent translation (reviewed in reference [7]). For instance, hnRNP C reportedly interacts specifically with the IRES for platelet-derived growth factor 2 (PDGF2)/c-sis during cell differentiation [17], and hnRNP C1 and C2 are involved in the IRES efficiency of the X-chromosome-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP) mRNA [18]. In addition to hnRNP C1 and C2, the La autoantigen also binds to the XIAP IRES and modulates the translation of XIAP in vitro and in vivo [19]. The Apaf-1 (apoptotic protease-activating factor 1) mRNA contains an IRES whose activity depends on the binding of at least two ITAFs, the Unr upstream of N- and the PTB (polypyrimidine-tract-binding protein) [20,21].

A role for canonical initiation factors (eIFs) in mediating cellular IRES-dependent translation has also been proposed. Overexpression of eIF-4G and cleaved eIF-4G stimulate IRES-mediated translation of ODC mRNA and Apaf-1 mRNA respectively [22,23]. The IRES elements of the cationic amino acid transporter protein 1 (Cat-1), c-myc and PDGF2 mRNAs function efficiently under conditions of amino acid starvation, genotoxic stress and cell differentiation, conditions which are associated with increased eIF-2α phosphorylation [24–27].

The detailed mechanism that leads to modulation of cellular IRES-dependent translation during physiological (embryogenesis) or stress (apoptosis, hypoxia, mitosis) conditions, especially the requirement for secondary and tertiary structure in the IRES elements and the role played by ITAFs, is poorly understood. In an attempt to understand better the mechanism by which the PITSLRE IRES is regulated, we determined the minimal sequence of the IRES necessary for mediating internal initiation of translation and investigated the requirement for trans-acting factors.

EXPERIMENTAL

Plasmid constructs

Methods used to generate the dicistronic pcDNA3 expression vectors containing the different p110PITSLRE fragments (Di-4 and mutants of Di-4) are described in the online supplementary data (http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/385/bj3850155add.htm).

The ODC IRES was obtained by a 5′-RACE (rapid amplification of cDNA ends) reaction on poly(A)+ (polyadenylated) mRNA from human HeLa cells, using the SMART™ RACE cDNA Amplification Kit (Clontech) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The gene-specific primer, 5′-GAACGTAGAGGCAGCAGCAACAGTGTAA-3′, was used to amplify ODC 5′-UTR. The ODC IRES was cloned in the dicistronic pcDNA3 expression vector as described for the p110PITSLRE fragments (supplementary data at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/385/bj3850155add.htm).

The dicistronic pcDNA3 expression vector containing the human rhinovirus (HRV) IRES was made by first cloning the HRV IRES as a SalI–NcoI fragment from the pXLJ-HRV 10-611 vector (a gift from Professor Richard J. Jackson, Department of Biochemistry, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, U.K.) [28], and the Fluc (firefly luciferase) gene (NcoI–XbaI fragment of pBluescript-fluc), into the pUC18 plasmid by a three-point ligation. In a second three-point ligation the complete HRV-fluc insert was cloned as a SalI–EcoRI fragment together with the Rluc [Renilla (sea pansy) luciferase] gene, as a KpnI–SalI fragment from pSV-sport-rluc, in the KpnI–EcoRI linearized pcDNA3 expression plasmid.

The dicistronic pcDNA3 expression vector containing the EMCV (encephalomyocarditis virus) IRES was made by a three- point ligation: the EMCV-fluc fragment was recovered as an Xho–XbaI fragment from the dicistronic vector pSV-Sport-lacZ-EMCV-fluc and cloned, together with the Rluc gene, as a KpnI–SalI fragment from pSV-sport-rluc, in the KpnI–XbaI linearized pcDNA3 expression plasmid.

The pGL3-PITSLRE construct was obtained by ligating the PITSLRE sequence (nts 745–1125) as a HindIII–NcoI fragment into the HindIII–NcoI-opened pGL3-basic vector.

For the UV-cross-linking experiments, the different PITSLRE PCR fragments (XbaI–NcoI-digested) were cloned into the pUC19 plasmid containing the T7 promoter using the following strategy: the Fluc gene was amplified by PCR from the pGL3-basic vector (Promega). The forward primer, 5′-TTCTAGAAATTTGCGGCCGCAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGAATTCTCTAGAATGGAAGACGCCAAAAACATAAAGAAAGGCCC-3′, contains the restriction sites NotI and XbaI respectively, upstream and downstream of the T7 promoter sequence (underlined). The reverse primer, 5′-CCCAAGCTTATTTAGGTGACACTATAGAACCATGGTTACACGGCGATCTTTCCGCCCTTC-3′, contains the Sp6 promoter (underlined) between the restriction sites HindIII and NcoI. The PCR product (NotI–HindIII-digested) was cloned in the pBluescript plasmid, from which the SacI–HindIII fragment was then subcloned into the pUC19 vector to obtain pUC19-T7-fluc. The Fluc gene was finally removed by XbaI–NcoI digestion and replaced by the different PITSLRE fragments.

The pGBKT7-unr vector was made by cloning the NcoI–XmaI-digested PCR amplification product obtained from pET21d-unr plasmid (a gift from Professor Richard J. Jackson) using the sense primer, 5′-TTCATGCCATGGGCTTTGATCCAAACCTTCTCCACAACAAT-3′, and the antisense primer, 5′-TCCCCCCGGGTTAGTCAATGACACCAGCTTGACGGATCT-3′, in the NcoI–XmaI-linearized pGBKT7 vector (BD Biosciences–Clontech).

Human cDNAs of PKR (double-stranded-RNA-activated protein kinase) and PKR-K296R (death mutant [Lys296→arginine]KPR) were cloned in the pEF6/Myc-His vector (Invitrogen) in-frame with C-terminal tags. These plasmids have been described elsewhere [29] and were kindly provided by Dr Xavier Saelens (Molecular Signalling and Cell Death Unit of our Department).

Transient DNA transfection and reporter gene assay

Human embryonic kidney 293T cells (a gift from Dr M. Hall, Department of Biochemistry, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, U.K.) were transiently transfected by the calcium phosphate precipitation method [30]. Cells were incubated for at least 4 h with the transfection solution, followed by addition of fresh Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated FCS (fetal-calf serum). At 24 h after transfection, cells were washed with cold phosphate buffer and lysed in Passive Lysis Buffer (Promega). Both Rluc and Fluc activities were measured using the dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and light emission was detected by using a Top-Count NXT Microplate Scintillation and Luminescence Counter (PerkinElmer).

Cell cycle synchronization

The IL-3 (interleukin-3)-dependent mouse pre-B-cell line Ba/F3 was maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated FCS and 10% (v/v) conditioned medium from WEHI-3B (mouse myelomonocytic leukaemia macrophage-like) cells as a source of mouse IL-3. Cell-cycle synchronization of Ba/F3 cells was obtained by depletion of IL-3 for 14 h to arrest the cells in G1 phase. To release this block, the Ba/F3 cells were refreshed with medium containing IL-3.

Western-blot analysis

Cells were lysed in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1% (v/v) Nonidet P40, 10 mM EDTA, 200 units/ml aprotinin, 1 mM Pefabloc, 0.1 mM PMSF and 10 μg/ml leupeptin. Equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS/PAGE, and the proteins were transferred on to nitrocellulose membranes by electroblotting. The blots were probed with 1:4000 dilution of rabbit anti-Unr polyclonal antibody (kindly provided by Professor Richard J. Jackson). p110PITSLRE and p58PITSLRE protein kinases and cyclin B1 were immunodetected using rabbit polyclonal anti-PITSLRE antibody and anti-cyclin B1 antibody respectively (Santa Cruz Biotechnology and Becton–Dickinson). Mouse anti-β-actin antibody was purchased from ICN Biomedicals (now MP Biomedicals). Antibodies against phosphorylated and total eIF-2α were obtained from Research Genetics (Huntsville, AL, U.S.A.) and Santa Cruz Biotechnology respectively.

Expression of recombinant Unr in Escherichia coli

E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS cells (Novagen) were transformed with the pET21d vector containing the Unr open reading frame as an NcoI–HindIII fragment (a gift from Professor Richard J. Jackson). This vector allows expression of Unr with a C-terminal hexahistidine fusion. Overexpression of Unr was induced by addition of 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside) to the culture medium, and the His-tagged protein was purified by Ni-NTA (Ni+-nitrilotriacetate)–agarose (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and dialysed extensively against 20 mM Hepes/KOH (pH 7.4), 100 mM KCl and 2 mM DTT (dithiothreitol).

UV cross-linking assays and immunoprecipitation

For UV cross-linking assays, DNA templates for synthesis of the respective RNA probes were generated by linearizing pUC19 T7 plasmids containing the HRV IRES, the EMCV IRES or different fragments of PITSLRE, with the appropriate restriction enzymes. Internally labelled RNA probes were synthesized by in vitro transcription with T7 polymerase (MAXIscript T7 RNA polymerase kit; Ambion, Austin, TX, U.S.A.) in the presence of 50 μCi of [α-32P]UTP (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

The cytoplasmic extracts used for the UV cross-linking assays were prepared from 293T or Ba/F3 cells as follows. Cells were collected, washed with cold PBS and recovered by centrifugation at 2500 g for 5 min at 4 °C. The cell pellets were resuspended in 100 μl of lysis buffer A containing 10 mM Hepes/KOH, pH 7.4, 3 mM MgCl2, 40 mM KCl, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 0.3% (v/v) Nonidet P40, 200 units/ml aprotinin, 0.1 mM PMSF and 10 μg/ml leupeptin. After lysis, the samples were centrifuged at 20000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were recovered, adjusted to a final protein concentration of 10 mg/ml and kept at −80 °C. UV cross-linking assays were performed as described in [31]. 32P-labelled RNA probes (≈1×106 c.p.m.) were incubated with either 400 ng of recombinant His-tagged Unr protein or 10 μl of cytoplasmic extract (100 μg of protein) for 20 min at 30 °C in a 25 μl reaction mixture containing 10 mM Hepes/KOH, pH 7.4, 3 mM MgCl2, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 100 mM KCl, 40 units of RNasin (Promega) and 6 μg of tRNA. After RNA binding, the reaction mixtures were irradiated on ice with UV light for 30 min using a GS Gene Linker UV Chamber (Bio-Rad). The samples were then incubated with RNase A and RNase T1 for 60 min at 37 °C. The RNA–protein complexes were resolved by SDS/10%-(w/v)-PAGE, the gels were dried and bands were visualized with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

For immunoprecipitation following RNase cocktail treatment, 1.5 μl of mouse monoclonal anti-(E tag) antibody (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) was added to each sample. After an overnight incubation at 4 °C in a rotary mixer, 30 μl of Protein G–Sepharose beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), previously equilibrated in lysis buffer A, was added and incubation was continued for 3 h. After washing six times with 1 ml of buffer containing 50 mM Hepes/KOH, pH 7.4, 250 mM NaCl, 1% (v/v) Nonidet P40, 5 mM EDTA, 200 units/ml aprotinin, 0.1 mM PMSF and 10 μg/ml leupeptin, resin-bound proteins were detached from the beads by adding 30 μl of Laemmli sample buffer and heating the mixture for 5 min at 95 °C. The proteins were then resolved by SDS/10%-PAGE.

In vitro transcription and translation

The dicistronic plasmids and the pGBKT7-unr plasmid coding for Unr were linearized with the appropriate restriction enzymes and used as templates to generate capped dicistronic transcripts with the T7 RNA polymerase from the Megascript kit (Ambion). The transcription reactions were performed in the presence of the RNA-cap-structure analogue m7GpppG (New England Biolabs) and GTP at a ratio of 4:1 according to the manufacturer's instructions.

The in vitro translation assays described in Table 1 (below) were performed in HeLa S3 cell extracts prepared by following a reported protocol [32]. Briefly, 80 ng of capped dicistronic transcript was mixed with 4 μl of cell lysate in a final reaction volume of 10 μl containing 16 mM Hepes/KOH, pH 7.6, 20 mM creatine phosphate, 0.1 μg/μl creatine kinase, 0.1 mM spermidine, 100 μM amino acids, 50 mM potassium acetate and 2.5 mM magnesium acetate. The translation reactions were carried out at 37 °C for 60 min, and luciferase activities were measured as described above using the dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega).

Table 1. Efficiency of different fragments of the PITSLRE IRES in mediating internal initiation of translation in vitro.

Capped dicistronic RNAs containing different fragments of PITSLRE IRES between the Fluc and Rluc reporter genes were obtained by in vitro transcription of the dicistronic vectors described in Figure 1(B). Equal amounts (80 ng) of transcripts were translated in vitro in HeLa S3 cell extracts. Rluc and Fluc activities were measured as described in the Experimental section. Relative IRES activity was determined as the Fluc/Rluc ratio. Abbreviation: c.p.s., counts/s.

| Activity (c.p.s.) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Capped dicistronic transcript | Fluc (IRES-dependent translation) | Rluc (cap-dependent translation) | Relative IRES activity (Fluc/Rluc) |

| D4 | 28997±2478 | 1754827±13355 | 0.0165±0.0015 |

| D4 mut C | 31685±6907 | 1532679±228816 | 0.020±0.001 |

| D4 mut D | 13160±2654 | 1526685±254331 | 0.0086±0.0001 |

| D4 mut E | 15028±168 | 1578001±113157 | 0.0095±0.0001 |

| D4 mut F | 16951±188 | 1743767±38040 | 0.0097±0.0010 |

| D2 | 2079±569 | 1515697±82488 | 0.0014±0.0003 |

To investigate the role of Unr as a trans-acting factor in IRES-mediated translation, 0.2 μg of a reporter dicistronic mRNA was incubated for 10 min at 30 °C in a 10 μl RNA–protein interaction mixture composed of 4 μl of diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water, 4 μl of RRL (rabbit reticulocyte lysate) containing newly synthesized Unr (following the instructions of Promega) and 2 μl of RNA-binding buffer [75 mM Hepes (pH 7.9)/50 mM KCl/1 mM DTT/50% (v/v) glycerol]. Translation reactions (25 μl final volume) were initiated by incubating 5 μl of the above RNA–protein interaction mixture with 15.5 μl of fresh RRL, 0.5 μl of amino acid mixture (1 mM each) and 0.5 μl of RNasin (Promega) for 45 min at 30 °C.

Statistics

Results are expressed as means±S.E.M., and * indicates significant differences compared with the control as determined by Student's t test (P<0.05).

RESULTS

Involvement of the Unr protein in PITSLRE IRES-mediated translation

Mapping of the PITSLRE IRES

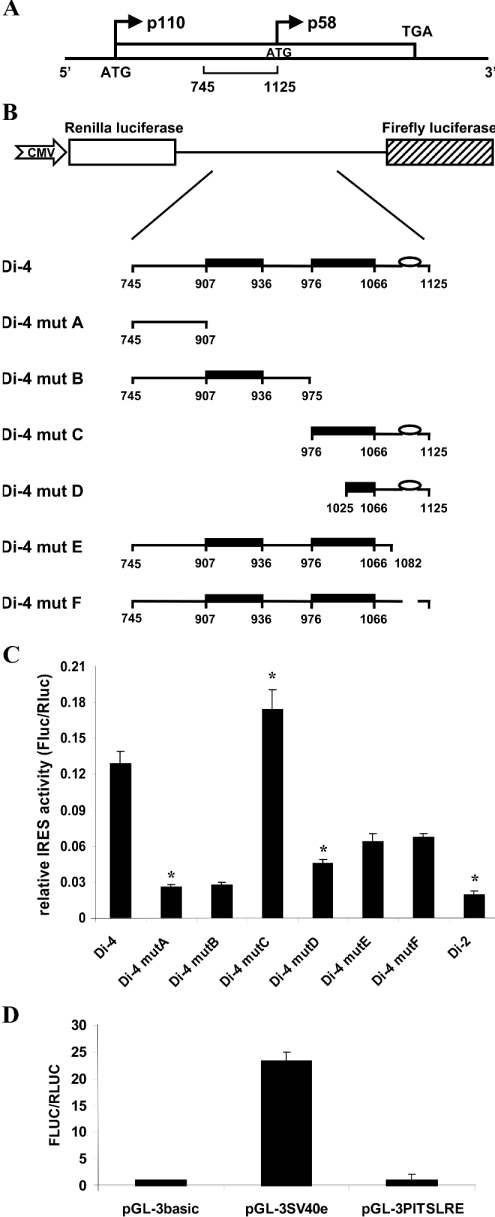

We previously reported that a 380-nucleotide region of the p110PITSLRE transcript located immediately upstream of the AUG codon (nts 745–1125) contains an IRES which allows the synthesis of p58PITSLRE kinase by internal initiation of translation during G2/M-phase [2] (Figure 1A). This region contains two polypurine-rich sequences starting at nts 907 and 976. To further delineate the functional IRES element, a series of dicistronic plasmids containing deletions of the p110PITSLRE fragment (nts 745–1125) was generated (Figure 1B). The PITSLRE fragments were placed in the intercistronic region between upstream Rluc and downstream Fluc coding sequences. As a negative control, we cloned a fragment of nts 121–468 of the p110PITSLRE transcript between Rluc and Fluc to obtain vector Di-2. This fragment has no IRES activity [2]. Figure 1(C) shows the ratio between the Fluc and Rluc activities following transient transfection of asynchronous 293T cells with the different dicistronic constructs. The raw data are presented in supplementary Table S1 (http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/385/bj3850155add.htm). Neither Di-4 mut A nor Di-4 mut B allows internal initiation of translation (Figure 1C). The Fluc/Rluc ratios are comparable with that seen with the Di-2 vector, and are almost 80% lower than that obtained with the Di-4 construct. These low values are due to specific inhibition of cap-independent translation (Fluc expression), and no significant change in the expression level of Rluc in the different transfected cells was observed (supplementary Table S1). This result indicates that fragment nts 745–975, including the first purine-rich region, is insufficient for PITSLRE IRES-mediated translation, and suggests that a downstream element is required. This was confirmed by the fact that the PITSLRE fragment (nts 976–1125), which contains the downstream second purine-rich region, mediates internal initiation of translation as efficiently as the Di-4 PITSLRE fragment (Figure 1C). In addition, the integrity of the second purine-rich-region is required for optimal IRES activity, as the Fluc/Rluc ratio obtained with the Di-4 mut D vector is decreased by ≈65 and 75% compared with that obtained with the Di-4 and Di-4 mut C vectors respectively. Obviously, a sequence of 150 nucleotides (fragment nts 976–1125) is essential for PITSLRE IRES-mediated translation. Interestingly, this region contains a gaagaaguaa sequence at position 1105–1114 (Figure 1B) which is very similar to that identified by a SELEX (systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment) approach as a target of the human Unr RNA-binding protein [33]. Unr reportedly acts synergistically with PTB to stimulate the HRV IRES-dependent translation in vitro and in vivo [34,35] and to bind to, and activate, the cellular Apaf-1 IRES [20,21].

Figure 1. Deletion analysis and mapping of the PITSLRE IRES.

(A) Schematic diagram of the human PITSLRE cDNA (α2-2 isoform). The start codon of the p110PITSLRE protein kinase and the internal initiation codon for the smaller p58PITSLRE isoform are indicated by ATG. The common stop codon for both proteins is indicated by TGA. The PITSLRE element (nts 745–1125), reported to mediate internal initiation of translation [2], is represented by a horizontal brace. (B) Diagram of the dicistronic constructs used to measure protein expression after transient transfection into 293T cells. The coding regions of Fluc and Rluc were inserted downstream of a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter, and different fragments of the PITSLRE IRES were inserted in the intercistronic spacer. Nucleotide numbers indicate the position based on the sequence of human p110PITSLRE cDNA. The black boxes represent the purine-rich regions in the PITSLRE IRES element, and the ellipse illustrates the Unr-binding element (nts 1105–1114). (C) 293T cells were transfected with the dicistronic vectors described in (B), and both Fluc and Rluc activities were determined as described in the Experimental section. Results (means±S.E.M. for three independent transfection experiments) represent the ratio between the Fluc and Rluc activities. *P<0.05 compared with cells transfected with the Di-4 construct. The absolute values of Rluc and Fluc activities are presented in supplementary Table S1 (http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/385/bj3850155add.htm). (D) No cryptic promoter activity present in the PITSLRE IRES sequence. PGL-3PITSLRE, pGL-3SV40e and pGL-3basic were co-transfected with the pSV-Sport Rluc plasmid in 293T cells. Fluc activity was normalized to the Rluc activity. Bars represent the mean±S.D. (n=3) Fluc activities normalized to the Rluc expression level.

To investigate whether the potential Unr-binding sequence contributes to PITSLRE IRES efficiency, we measured the ability of two dicistronic constructs (Di-4 mut E and Di-4 mut F) to drive internal initiation of translation. Di-4 mut E includes a truncated PITSLRE fragment (nts 745–1082) and the Di-4 mut F vector lacks the gaagaaguaa sequence (nts 1105–1114) (Figure 1B). Figure 1(C) shows that the Fluc/Rluc ratio measured in Di-4 mut E and Di-4 mut F transfectants is almost 50% lower than that in cells expressing Di-4. No significant difference between the inhibitory effects induced by Di-4 mut E and Di-4 mut F was observed, suggesting that deletion of the gaagaaguaa sequence is sufficient to impair PITSLRE IRES function.

To rule out a contribution by a cryptic promoter or splicing event to the ability of the Di-4 and Di-4 mutants to translate the downstream Fluc gene, control experiments were performed (Figure 1D, Table 1).

Previously, we showed by Northern blot that both cistrons of Di-4 were translated from the same intact dicistronic mRNA [2]. To exclude further the possibility of putative promoter activity, we analysed this fragment in a promoterless pGL-3basic vector (Figure 1D). This pGL-3PITSLRE plasmid as well as the pGL-3SV40e plasmid [a vector containing the simian-virus-40 early promoter, which served as a positive control] and the promoterless pGL-3basic plasmid were co-transfected with pSV-Sport Rluc plasmid in 293T cells, the latter to correct for variation of transfection efficiencies. Confirming our previous results, Figure 1(D) shows that presence of cryptic promoter sequences in the nts 745–1125 fragment is very unlikely, as the pGL-3PITSLRE and pGL-3basic reporters show similar relative Fluc expression levels, ≈20-fold lower compared with that of the pGL-3SV40e plasmid.

To exclude further the possibility that the differences in the ability of the PITSLRE fragments to drive internal initiation of translation result from splicing events or promoter activity, we tested in-vitro-synthesized capped dicistronic transcripts in an in vitro translation assay based on HeLa S3 extracts. Table 1 shows that the pattern of IRES efficiency (Fluc/Rluc) among the different transcripts is similar to that observed in vivo in 293T transfectants. Consequently, the in vitro data also rule out the possibility that cryptic promoter sequences or splicing events contribute to the ability of the Di-4 and Di-4 mutants to mediate internal initiation of translation, but confirm the involvement of the purine-rich region and the gaagaaguaa sequence in PITSLRE IRES function.

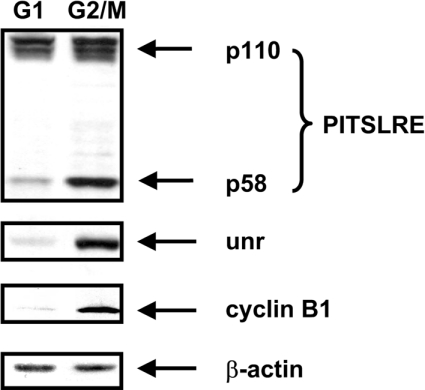

Expression of Unr is maximal at G2/M-phase

The importance of a potential Unr-binding site in PITSLRE IRES efficiency led us to investigate whether this protein might play a role in IRES function. As the PITSLRE IRES specifically drives internal initiation of translation during the G2/M stage of the cell cycle, we first analysed by Western blotting the expression of Unr in IL-3-dependent Ba/F3 cells synchronized at specific cell-cycle stages. As expected, p58PITSLRE kinase and cyclin B1 (a specific marker for G2/M stage) were expressed during the G2/M stage, whereas p110PITSLRE was equally expressed in G1-stage- and G2/M-stage-specific cells (Figure 2). The level of Unr protein also fluctuates during cell cycle progression: it is maximal during the G2/M stage and very low during the G1 stage.

Figure 2. Expression of Unr protein during cell-cycle progression.

Ba/F3 cells were synchronized at the G1 stage by IL-3 depletion for 14 h and then released from this block by restitution of IL-3 into the culture medium. Respectively 3 h (G1 stage) and 16 h (G2/M stage) after IL-3 restitution, cell extracts were made and resolved by SDS/PAGE, then analysed by Western blotting using specific antibodies. This Figure is representative of those obtained in three independent experiments.

Unr binds and stimulates the PITSLRE IRES element in vitro

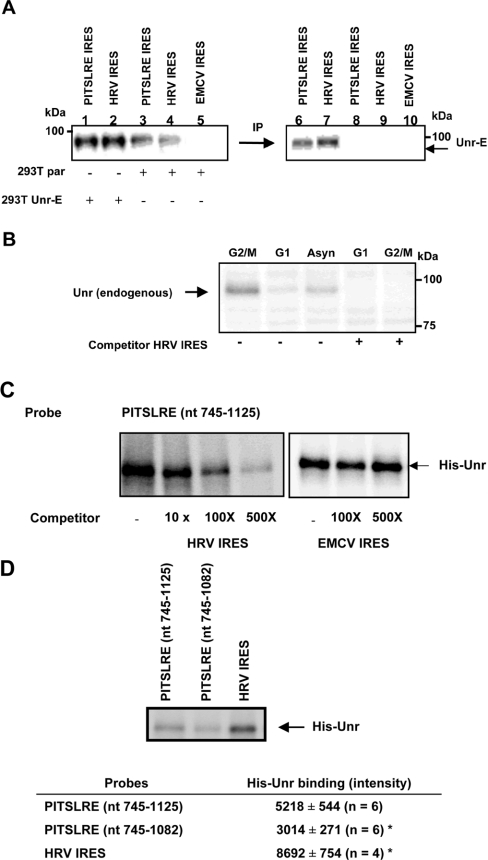

We next investigated whether the PITSLRE IRES RNA interacts with the Unr protein. Cell lysates from parental 293T cells or from 293T transfectants overexpressing E-tagged Unr (Unr-E) were UV-cross-linked with the PITSLRE IRES (nts 745–1125), HRV or EMCV IRES probes. HRV IRES, known to interact with Unr [34], served as a positive control. EMCV IRES function does not require Unr protein [35] and served as a negative control. Figure 3(A) illustrates that a 32P-labelled protein band of ≈97 kDa, corresponding to the size of Unr, is cross-linked with the PITSLRE and the HRV IRES probes, but not with the EMCV IRES probe. This band is most prominently bound in the UV reactions with the Unr-overexpressing 293T cell extracts (Figure 3A, lanes 1–2) and is immunoprecipitated with an anti-(E tag) antibody (lanes 6 and 7). The bands detected in the reactions with parental 293T cell extracts probably correspond to the endogenous Unr protein (Figure 3A, lanes 3 and 4). Overall our data indicate that both the PITSLRE (nts 745–1125) and HRV IRES probes interact with the E-tagged Unr (Figure 3A, lanes 6 and 7) and with the endogenous Unr proteins (Figure 3A, lanes 3 and 4).

Figure 3. PITSLRE IRES binds to Unr.

(A) Cytoplasmic extracts from parental 293T cells (293T par) or from 293T transfectants overexpressing E-tagged Unr (293T Unr-E) were prepared as described in the Experimental section. After UV irradiation with the RNA probes corresponding to the PITSLRE fragment (nts 745–1125), the HRV IRES or the EMCV IRES samples were treated with an RNase cocktail. One part of the sample was analysed by SDS/PAGE, whereas the other part was further mixed with anti-(E tag) antibody for immunoprecipitation (IP) of labelled E-tagged Unr. Bound proteins were analysed by SDS/PAGE. (B) Binding of the endogenous Unr to the PITSLRE IRES during cell-cycle progression. UV-cross-linking assays were performed by pre-incubating the cytoplasmic extracts from asynchronous (Asyn), G1-stage- and G2/M-stage-specific Ba/F3 cells in the absence or presence of 500-fold molar excess of unlabelled HRV IRES transcript before addition of the 32P-labelled PITSLRE fragment (nts 745–1125). After RNA binding and UV irradiation, samples were treated with the RNase cocktail and resolved by SDS/PAGE. The arrow depicts the position of the endogenous cross-linked Unr. This Figure is representative of those obtained in two independent experiments. (C) Recombinant histidine-tagged Unr protein interacts with the PITSLRE IRES. UV-cross-linking assays were performed by pre-incubating 400 ng of histidine-tagged Unr protein purified from E. coli (His-Unr) in the absence or presence of a 10–500-fold molar excess of unlabelled HRV IRES transcript or EMCV IRES transcript before addition of the 32P-labelled PITSLRE fragment (nts 745–1125). After RNA binding and UV irradiation, samples were treated with the RNase cocktail and resolved by SDS/PAGE. The arrow depicts the position of cross-linked histidine-tagged Unr. (D) Deletion of 50 nts at the 3′-end of the PITSLRE fragment (nts 745–1125) decreases its binding affinity for Unr. UV-cross-linking assays were performed as described above by incubating the 32P-labelled PITSLRE fragments nts 745–1125 and nts 745–1082 or the 32P-labelled HRV IRES transcript with the recombinant histidine-tagged Unr protein (400 ng). The intensity of radiolabelled His-Unr bands was quantified by densitometry, and the results, representing means±S.E.M. for the number of experiments given in parentheses, are summarized in the inserted Table.

Next we investigated the effect of cell-cycle progression on the interaction of endogenous Unr with the PITSLRE IRES fragment (nts 745–1125), using cell extracts from asynchronous, G1- and G2/M-cell-cycle-stage-specific cells. The amount of Unr bound to the PITSLRE IRES is barely detectable in the presence of G1-stage-specific lysates, but increases significantly during the G2/M stage (Figure 3B). The interaction with Unr was specifically inhibited by a 500-fold molar excess of unlabelled HRV IRES (Figure 3B).

Specific binding of Unr to the PITSLRE IRES fragment (nts 745–1125) was confirmed by a UV-cross-linking assay using purified recombinant histidine-tagged Unr (Figure 3C). The interaction was specifically inhibited by a molar excess of unlabelled HRV IRES, whereas a molar excess of unlabelled EMCV IRES had no effect.

The PITSLRE IRES fragment (nts 745–1082) lacking the Unr-binding site was also used as a probe. Figure 3(D) shows that this fragment has a lower binding affinity than the full-length PITSLRE IRES element (nts 745–1125) for His–Unr. Binding is almost 45% lower, and these UV-cross-linking data correlate with a decreased IRES efficiency (Figure 1C; compare constructs Di-4 and Di-4 mut E).

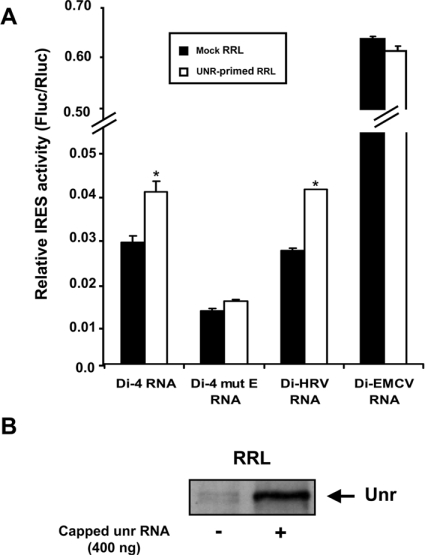

The involvement of a potential Unr-binding element in PITSLRE IRES-mediated translation was further confirmed by a functional in vitro translation assay (Figure 4A). The Unr protein was synthesized in RRL from capped mRNA encoding Unr. In mock RRL, endogenous Unr is barely detectable (Figure 4B). Figure 4(A) shows a small, but reproducible (1.4-fold), increase in the Fluc/Rluc ratio when testing the Di-4 RNA in Unr-primed RRL as compared with mock RRL. A similar increase was observed with the Di-HRV transcript, while no significant increase was seen with the Di-EMCV RNA and Di-4 mut E transcripts.

Figure 4. Effect of Unr on PITSLRE IRES-mediated translation in RRL.

(A) In vitro translation of capped dicistronic mRNAs in mock-translated RRL and in Unr-primed RRL. A 4 μl portion of mock-translated RRL or RRL expressing Unr (Unr-primed RRL) was preincubated for 10 min at 30 °C with the capped dicistronic RNAs obtained by in vitro transcription using the linearized Di-4, Di-4 mut E, Di-HRV and Di-EMCV vectors respectively. Translation reactions were then carried out as described in the Experimental section. After translation of the dicistronic reporter mRNAs, lysates were assayed for Fluc and Rluc activities. Results are expressed as the ratio between Fluc and Rluc activities and represent the means±S.E.M. for three independent experiments. *P<0.05 compared with mock RRL primed with the corresponding dicistronic mRNA. (B) Protein level of Unr in mock-translated RRL and in RRL first primed with 400 ng of capped transcript coding for Unr.

In conclusion, these observations suggest a stimulatory role for Unr in PITSLRE IRES-driven internal initiation of translation.

Involvement of phosphorylated eIF-2α in PITSLRE IRES-mediated translation

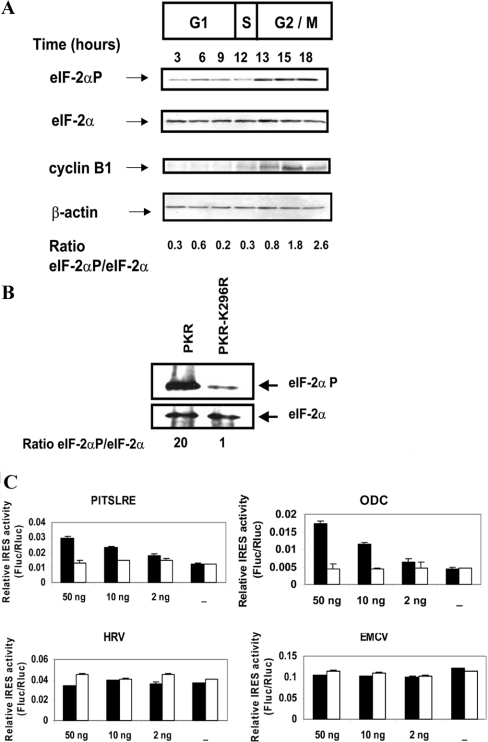

Increased phosphorylation of the α-subunit of initiation factor eIF-2 was reported to occur at the G2−stage/M-stage boundary in human osteosarcoma cells [36]. Phosphorylation of eIF-2α prevents the GDP↔GTP exchange reaction necessary for the formation of the ternary initiation complex eIF-2·GTP·Met-tRNA, impairing the binding of Met-tRNA to ribosomes [37]. As mentioned above, several IRESs, including the PITSLRE IRES, are functional during the G2/M stage, and phosphorylation of eIF-2α might be involved in the switch from cap- to IRES-mediated translation in mitosis. Therefore we evaluated the phosphorylation state of eIF-2α in Ba/F3 cells during cell-cycle progression and analysed the effect of eIF-2α phosphorylation on PITSLRE IRES-mediated translation. Figure 5(A) shows that the level of eIF-2α does not change during cell-cycle progression. In contrast, whereas the amount of phospho-eIF-2α is rather low at the G1 stage, it is significantly enhanced during the G2/M stage, when the ratio between phospho-eIF-2α and eIF-2α increases at least 4-fold.

Figure 5. Role of increased phosphorylation of eIF-2α in the PITSLRE IRES-mediated translation.

(A) Cell-cycle progression from G2 stage to mitosis stimulates the phosphorylation of eIF-2α. Ba/F3 cells were synchronized at the G1 stage by IL-3 depletion for 14 h and then released from this block by addition of IL-3 into the culture medium. At indicated times (starting from addition of IL-3) cell extracts were prepared as described in the Experimental section, and normalized protein amounts were processed for Western blotting using antibodies against eIF-2α, phospho-eIF-2α, cyclin B1 (a specific G2/M-stage marker) and β-actin. Results are representative of those obtained in three independent experiments. (B) Overexpression of PKR, but not PKR-K296R, results in an increased level of phospho-eIF-2α. 293T cells were transiently transfected with the vector coding for PKR or the negative mutant PKR-K296R. At 24 h after transfection, cells were lysed and 25 μg of protein was analysed by Western blotting using antibodies against total eIF-2α and phospho-eIF-2α. (C) Increased phosphorylation of eIF-2α is permissive for PITSLRE IRES activity. The dicistronic plasmids harbouring the PITSLRE fragment nts 745–1125 (Di-4), the HRV IRES, the ODC IRES or the EMCV IRES element were transiently co-transfected with increasing amounts of a PKR-encoding vector (black bar) or of a PKR-K296R encoding vector (open bar). At 24 h after transfection, cell lysates were assayed for Rluc and Fluc activities. Bars represent the mean±S.D. (n=3) of the ratio between the Fluc and Rluc activities.The absolute values of Rluc and Fluc luciferase activities are presented in Table S2 (http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/385/bj3850155add.htm). Results are representative of those obtained in three independent experiments.

Next we wished to determine whether the level of phospho-eIF-2α modulates PITSLRE IRES function. We analysed PITSLRE IRES efficiency in the presence of overexpressed PKR, a kinase that phosphorylates the α-subunit of eIF-2 on Ser51 [38]. As shown in Figure 5(B), overexpression of PKR strongly stimulates the phosphorylation of eIF-2α in 293T transfectants, whereas the kinase death mutant PKR-K296R does not. Overexpression of PKR results in repression of global protein synthesis. Indeed, translation of Rluc derived from Di-4 was inhibited up to approx. 50% in the PKR co-transfectants (Table S2 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/385/bj3850155add.htm). In contrast, translation of the Fluc reporter showed a slight increase upon PKR overexpression, resulting in a significant increase (double) in the ratio between Fluc and Rluc activities over that measured in cells expressing PKR-K296R (Figure 5C). In the same experiment we also analysed another cell-cycle-dependent IRES located in the 5′-UTR of ODC mRNA, as well as two viral IRESs, EMCV IRES and HRV IRES. Like Di-4, the ODC IRES-containing vector (Di-ODC) produced a Fluc/Rluc ratio significantly higher (almost 4-fold) than that measured in cells co-transfected with PKR-K296R. Again, this was due to an increased IRES-mediated translation of the Fluc gene (double) despite inhibition of the cap-dependent translation caused by PKR overexpression (Table S2 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/385/bj3850155add.htm). Whether cells were co-transfected with PKR/Di-EMCV(or-HRV) or with PKR-K296R/Di-EMCV(or-HRV), the ratio between Fluc and Rluc activities remained the same (Figure 5C). Both cap-dependent translation and IRES-mediated translation from Di-EMCV or Di-HRV were impaired to the same extent in PKR-overexpressing cells.

DISCUSSION

From the results of the present study we suggest that Unr plays a role in the regulation of the cell-cycle-dependent PITSLRE IRES. First, the expression of Unr is cell-cycle-regulated and is optimal at the G2/M stage (Figure 2). Secondly, Unr effectively binds to the PITSLRE IRES at the G2/M stage (Figures 3A, 3B and 3C), and deletion of the unr-binding consensus motif gaagaaguaa in the PITSLRE transcript decreases binding affinity for Unr (Figure 3D) and decreases the IRES efficiency (Figure 1C). Thirdly, Unr significantly increases the PITSLRE IRES activity in vitro, but has no significant effect on the ability of a PITSLRE IRES fragment lacking the Unr-binding motif to mediate internal initiation of translation (Figure 4A).

However, additional structural elements and/or trans-acting factors are likely to be necessary for efficient PITSLRE IRES activity, as deletion of the Unr-consensus binding sequence gaagaaguaa did not completely abrogate IRES activity. In support of this hypothesis, we have shown that the integrity of the second purine-rich element is necessary for PITSLRE IRES-mediated translation. The PITSLRE fragment nts 976–1125 (Di-4 mut C) drives internal initiation of translation as efficiently as Di-4 (fragment nts 745–1125), whereas truncation of half of the purine stretch (Di-4 mut D; fragment nts 1025–1125) impairs the IRES activity considerably. Nevertheless, these three fragments displayed the same binding affinity for recombinant His-tagged Unr (results not shown). Therefore, in addition to the binding of Unr, other trans-acting factors and/or cis-acting elements are likely to be necessary for PITSLRE IRES efficiency.

Structure-probing data of the cellular Apaf-1 IRES have suggested that the binding of Unr to the Apaf-1 IRES changes its structure and renders it accessible to PTB, and possibly other proteins, allowing the IRES to achieve the appropriate conformation for binding of the 40 S ribosomal subunit [21]. Although the detailed mechanism by which Unr regulates the PITSLRE IRES remains unclear, it is conceivable that, as in the case of the Apaf-1 IRES, Unr acts as an RNA chaperone. The binding of Unr may be involved in unfolding of the PITSLRE IRES, rendering elements, and especially the purine-rich region, accessible to specific trans-acting factors.

Whereas pyrimidine-rich sequences in several IRESs such as EMCV and c-Myc IRES are targets for PTB and hnRNPC1/C2 respectively [6,7,16], the importance of purine-rich sequences for IRES-mediated translation is less clear. Artificial polypurine (A)-rich sequence (PARS)-containing elements have been shown to promote IRES-mediated translation in vitro in plant and mammalian cells [39]. Consistently, the 5′-UTR of the heat-shock factor 1 mRNA of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), which contains short PARS elements with multiple (G)1–4(A)2–5 modules, functions as an IRES in plant extracts, RRL, tobacco protoplasts and human HeLa cells. The purine-rich region (nts 976–1066) of the PITSLRE fragment (nts 976–1125) contains few gaa modules that may contribute to the IRES efficiency, but a role for specific ITAFs remains unknown. Because (G)1–4(A)2–5 modules do not contain the conserved core motif aagua/g involved in the RNA binding specificity of Unr [35], interaction with Unr appears very unlikely. This is supported by our observation that truncation of the purine-rich region does not change the binding affinity of the PITSLRE fragment (nts 1025–1125) for Unr compared with the fragments nts 745–1125 and nts 976–1125.

The purine-rich region is necessary, but not sufficient, to mediate internal initiation of translation. Indeed, in a preliminary experiment we compared the PITSLRE IRES activity of fragment nts 976–1125, in which the downstream Unr consensus binding site (nts 1105–1114) has been deleted, with that of the complete [nts 976–1125] fragment. Interestingly, deletion of the Unr consensus binding site results in a strong inhibition of the IRES efficiency (by 80%) compared with the wild-type fragment, despite the fact that the intact purine-rich region is present in both fragments (results not shown). This observation supports the hypothesis that Unr may act as an RNA chaperone that somehow renders the purine-rich region necessary for PITSLRE IRES-mediated internal initiation of translation. The functional significance of this purine-rich region, especially the possible role of the gaa motifs as cis-acting elements, as well as the binding of specific ITAFs, needs further investigation.

A strong inhibition of cap-dependent translation has been reported in different cell types arrested in mitosis [40–42], due to a loss of ability of the initiation factor eIF-4E to bind to the cap structure [42]. Although a still controversial notion, it seems that sequestration of eIF-4E by the hypophosphorylated binding protein 4E-BP1 [43,44] during mitosis is responsible for such an inhibitory effect. On the other hand, Datta and co-workers reported a sharp decline in the overall rate of protein synthesis due to increased phosphorylation of eIF-2α in human osteosarcoma cells reaching the G2-stage/M-stage boundary [36]. Thus, it is likely that several signal-transduction pathways may contribute to the inhibition of cap-dependent translation during mitosis and may be involved in the switch from cap- to IRES-dependent translation.

Here we show that the amount of phospho-eIF-2α increases at the G2/M stage of the cell cycle, which coincides with the functionality of the PITSLRE IRES (Figure 5A). More importantly, we demonstrate that, in the presence of an increased level of phospho-eIF-2α due to overexpression of the eIF-2α kinase PKR, the PITSLRE IRES is still active, whereas cap-dependent translation is blocked [Figure 5C; supplementary Table S2 (http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/385/bj3850155add.htm)]. We also found a permissive effect of phospho-eIF-2α on the ability of the ODC IRES, a cellular IRES also activated during the G2/M stage, to mediate internal initiation of translation, while this is not the case for the viral HRV and EMCV IRESs. Our results indicate that the cell-cycle-dependent IRESs, namely PITSLRE and ODC IRESs, mediate internal initiation of translation in the presence of a high amount of phosphorylated eIF-2α, and suggest that the requirement for eIF-2α may differ between these two groups of IRESs.

It has recently been shown that phosphorylation of eIF-2α stimulates IRES-mediated translation of the Cat-1 protein during cellular stress [26], and that eIF-2α phosphorylation is required for activation of cellular IRESes such as those for PDGF2, c-myc and VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) during cell differentiation [27]. As the level of phospho-eIF-2α is up-regulated during the G2/M stage, it is very likely that this event contributes to the G2/M-stage-specific expression of p58PITSLRE and ODC.

In summary, we have identified a polypurine-rich region essential for the PITSLRE IRES function. We have also shown that both Unr expression and eIF-2α phosphorylation occur specifically during the G2/M stage of the cell cycle and contribute to PITSLRE IRES-mediated translation.

Online data

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Belgische Federatie tegen Kanker, the Interuniversitaire Attractiepolen and the FWO (Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek-Vlaanderen). B.S. is a predoctoral research fellow with the Vlaams Instituut voor de Bevordering van het Wetenschappelijk-technologisch Onderzoek in de Industrie. S.A.T. and S.C. are postdoctoral research associates with the Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek-Vlaanderen. We are very grateful to Dr G. Bergamini and Dr M. Hentze (Gene Expression Programme, European Molecular Biology Laboratory, Heidelberg, Germany) for providing us with the technique, the cells and the reagents to perform the in vitro translation assays in HeLa S3 extracts, as well as for their very helpful advice and suggestions. We thank Professor Richard J. Jackson for providing the anti-Unr antisera and the pXLJ-HRV (10-611) and pET21-unr vectors. We are also grateful to Dr E. Brown (Department of Biochemistry, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, U.K.) for her valuable advice on purifying the recombinant Unr protein. We thank Dr X. Saelens and Dr M. Kalai (both of the Molecular Signalling and Cell Death Unit of our Department) for providing us with the PKR and PKR-K296R constructs. We are grateful to Dr Amin Bredan (our Unit) for critical reading of the manuscript, and to A. Meeuws and W. Burn of our Unit for their technical assistance.

References

- 1.Lahti J. M., Xiang J., Kidd V. J. The PITSLRE protein kinase family. Prog. Cell Cycle Res. 1995;1:329–338. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1809-9_27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cornelis S., Bruynooghe Y., Denecker G., Van Huffel S., Tinton S., Beyaert R. Identification and characterization of a novel cell cycle-regulated internal ribosome entry site. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:597–605. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80239-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang S., Cai M., Xu S., Chen S., Chen X., Chen C., Gu J. Interaction of p58(PITSLRE), a G2/M-specific protein kinase, with cyclin D3. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:35314–35322. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202179200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bunnell B. A., Heath L. S., Adams D. E., Lahti J. M., Kidd V. J. Increased expression of a 58-kDa protein kinase leads to changes in the CHO cell cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1990;87:7467–7471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.19.7467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lahti J. M., Xiang J., Heath L. S., Campana D., Kidd V. J. PITSLRE protein kinase activity is associated with apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1995;15:1–11. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson R. J., Kaminski A. Internal initiation of translation in eukaryotes: the picornavirus paradigm and beyond. RNA. 1995;1:985–1000. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hellen C. U., Sarnow P. Internal ribosome entry sites in eukaryotic mRNA molecules. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1593–1612. doi: 10.1101/gad.891101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nanbru C., Lafon I., Audigier S., Gensac M. C., Vagner S., Huez G., Prats A. C. Alternative translation of the proto-oncogene c-myc by an internal ribosome entry site. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:32061–32066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pyronnet S., Pradayrol L., Sonenberg N. A cell cycle-dependent internal ribosome entry site. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:607–616. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang X., Richie C., Legerski R. J. Translation of hSNM1 is mediated by an internal ribosome entry site that upregulates expression during mitosis. DNA Repair (Amsterdam) 2002;1:379–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maier D., Nagel A. C., Preiss A. Two isoforms of the Notch antagonist Hairless are produced by differential translation initiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:15480–15485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242596699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morrish B. C., Rumsby M. G. The 5′ untranslated region of protein kinase Cδ directs translation by an internal ribosome entry segment that is most active in densely growing cells and during apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:6089–6099. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.17.6089-6099.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Honda M., Kaneko S., Matsushita E., Kobayashi K., Abell G. A., Lemon S. M. Cell cycle regulation of hepatitis C virus internal ribosomal entry site-directed translation. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:152–162. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70424-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brasey A., Lopez-Lastra M., Ohlmann T., Beerens N., Berkhout B., Darlix J. L., Sonenberg N. The leader of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomic RNA harbors an internal ribosome entry segment that is active during the G2/M phase of the cell cycle. J. Virol. 2003;77:3939–3949. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.7.3939-3949.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qin X., Sarnow P. Preferential translation of IRES-containing mRNAs during the mitotic cycle in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:13721–13728. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim J. H., Paek K. Y., Choi K., Kim T. D., Hahm B., Kim K. T., Jang S. K. Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein C modulates translation of c-myc mRNA in a cell cycle phase-dependent manner. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:708–720. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.2.708-720.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sella O., Gerlitz G., Le S. Y., Elroy-Stein O. Differentiation-induced internal translation of c-sis mRNA: analysis of the cis elements and their differentiation-linked binding to the hnRNP C protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:5429–5440. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holcik M., Gordon B. W., Korneluk R. G. The internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation of antiapoptotic protein XIAP is modulated by the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins C1 and C2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:280–288. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.1.280-288.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holcik M., Korneluk R. G. Functional characterization of the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP) internal ribosome entry site element: role of La autoantigen in XIAP translation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:4648–4657. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.13.4648-4657.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitchell S. A., Brown E. C., Coldwell M. J., Jackson R. J., Willis A. E. Protein factor requirements of the Apaf-1 internal ribosome entry segment: roles of polypyrimidine tract binding protein and upstream of N-ras. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:3364–3374. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.10.3364-3374.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitchell S. A., Spriggs K. A., Coldwell M. J., Jackson R. J., Willis A. E. The Apaf-1 internal ribosome entry segment attains the correct structural conformation for function via interactions with PTB and Unr. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:757–771. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00093-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayashi S., Nishimura K., Fukuchi-Shimogori T., Kashiwagi K., Igarashi K. Increase in cap- and IRES-dependent protein synthesis by overproduction of translation initiation factor eIF4G. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;277:117–123. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nevins T. A., Harder Z. M., Korneluk R. G., Holcik M. Distinct regulation of internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation following cellular stress is mediated by apoptotic fragments of eIF4G translation initiation factor family members eIF4GI and p97/DAP5/NAT1. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:3572–3579. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206781200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernandez J., Yaman I., Mishra R., Merrick W. C., Snider M. D., Lamers W. H., Hatzoglou M. Internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation of a mammalian mRNA is regulated by amino acid availability. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:12285–12291. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009714200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Subkhankulova T., Mitchell S. A., Willis A. E. Internal ribosome entry segment-mediated initiation of c-Myc protein synthesis following genotoxic stress. Biochem. J. 2001;359:183–192. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3590183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernandez J., Bode B., Koromilas A., Diehl J. A., Krukovets I., Snider M. D., Hatzoglou M. Translation mediated by the internal ribosome entry site of the cat-1 mRNA is regulated by glucose availability in a PERK kinase-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:11780–11787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110778200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gerlitz G., Jagus R., Elroy-Stein O. Phosphorylation of initiation factor-2α is required for activation of internal translation initiation during cell differentiation. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:2810–1819. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borman A., Jackson R. J. Initiation of translation of human rhinovirus RNA: mapping the internal ribosome entry site. Virology. 1992;188:685–696. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90523-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saelens X., Kalai M., Vandenabeele P. Translation inhibition in apoptosis: caspase-dependent PKR activation and eIF2-α phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:41620–41628. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103674200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Mahoney J. V., Adams T. E. Optimization of experimental variables influencing reporter gene expression in hepatoma cells following calcium phosphate transfection. DNA Cell. Biol. 1994;13:1227–1232. doi: 10.1089/dna.1994.13.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walker J., de Melo Neto O., Standart N. Gel retardation and UV-crosslinking assays to detect specific RNA-protein interactions in the 5′ or 3′ UTRs of translationally regulated mRNAs. Methods Mol. Biol. 1998;77:365–378. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-397-X:365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bergamini G., Preiss T., Hentze M. W. Picornavirus IRESes and the poly(A) tail jointly promote cap-independent translation in a mammalian cell-free system. RNA. 2000;6:1781–1790. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200001679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Triqueneaux G., Velten M., Franzon P., Dautry F., Jacquemin-Sablon H. RNA binding specificity of Unr, a protein with five cold shock domains. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:1926–1934. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.8.1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hunt S. L., Hsuan J. J., Totty N., Jackson R. J. Unr, a cellular cytoplasmic RNA-binding protein with five cold-shock domains, is required for internal initiation of translation of human rhinovirus RNA. Genes Dev. 1999;13:437–448. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.4.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boussadia O., Niepmann M., Creancier L., Prats A. C., Dautry F., Jacquemin-Sablon H. Unr is required in vivo for efficient initiation of translation from the internal ribosome entry sites of both rhinovirus and poliovirus. J. Virol. 2003;77:3353–3359. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.6.3353-3359.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Datta B., Datta R., Mukherjee S., Zhang Z. Increased phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2alpha at the G2/M boundary in human osteosarcoma cells correlates with deglycosylation of p67 and a decreased rate of protein synthesis. Exp. Cell. Res. 1999;250:223–230. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pain V. M. Initiation of protein synthesis in eukaryotic cells. Eur. J. Biochem. 1996;236:747–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaufman R. J. The double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase PKR. In: Hershey J. W., Mathews M. B., Sonenberg N., editors. Translational control of gene expression. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2000. pp. 503–527. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dorokhov Y. L., Skulachev M. V., Ivanov P. A., Zvereva S. D., Tjulkina L. G., Merits A., Gleba Y. Y., Hohn T., Atabekov J. G. Polypurine (A)-rich sequences promote cross-kingdom conservation of internal ribosome entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:5301–5306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082107599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fan H., Penman S. Regulation of protein synthesis in mammalian cells. II. Inhibition of protein synthesis at the level of initiation during mitosis. J. Mol. Biol. 1970;50:655–670. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(70)90091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tarnowka M. A., Baglioni C. Regulation of protein synthesis in mitotic HeLa cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 1979;99:359–367. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1040990311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bonneau A. M., Sonenberg N. Involvement of the 24-kDa cap-binding protein in regulation of protein synthesis in mitosis. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:11134–11139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pyronnet S., Dostie J., Sonenberg N. Suppression of cap-dependent translation in mitosis. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2083–2093. doi: 10.1101/gad.889201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heesom K. J., Gampel A., Mellor H., Denton R. M. Cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation of the translational repressor eIF-4E binding protein-1 (4E-BP1) Curr. Biol. 2001;11:1374–1379. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00422-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.