Abstract

Aβ (β-amyloid) peptides are found aggregated in the cortical amyloid plaques associated with Alzheimer's disease neuropathology. Inhibition of the proteasome alters the amount of Aβ produced from APP (amyloid precursor protein) by various cell lines in vitro. Proteasome activity is altered during aging, a major risk factor for Alzheimer's disease. In the present study, a human neuroblastoma cell line expressing the C-terminal 100 residues of APP (SH-SY5Y-SPA4CT) was used to determine the effect of proteasome inhibition, by lactacystin and Bz-LLL-COCHO (benzoyl-Leu-Leu-Leu-glyoxal), on APP processing at the γ-secretase site. Proteasome inhibition caused a significant increase in Aβ peptide levels in medium conditioned by SH-SY5Y-SPA4CT cells, and was also associated with increased cell death. APP is a substrate of the apoptosis-associated caspase 3 protease, and we therefore investigated whether the increased Aβ levels could reflect caspase activation. We report that caspase activation was not required for proteasome-inhibitor-mediated effects on APP (SPA4CT) processing. Cleavage of Ac-DEVD-AMC (N-acetyl-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin), a caspase substrate, was reduced following exposure of SH-SY5Y-SPA4CT cells to lactacystin, and co-treatment of cells with lactacystin and a caspase inhibitor [Z-DEVD-FMK (benzyloxycarbonyl-Val-Ala-DL-Asp-fluoromethylketone)] resulted in higher Aβ levels in medium, augmenting those seen with lactacystin alone. This study indicated that proteasome inhibition could increase APP processing specifically at the γ-secretase site, and increase release of Aβ, in the absence of caspase activation. This indicates that the decline in proteasome function associated with aging would contribute to increased Aβ levels.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, β-amyloid peptide, caspase 3, neuroblastoma, proteasome, γ-secretase

Abbreviations: Aβ, amyloid β peptide or β-amyloid; Ac-DEVD-AMC, N-acetyl-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin; Ac-DEVD-CHO, N-acetyl-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp aldehyde; AEBSF, 4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulphonyl fluoride; AMC, 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin; APP, amyloid precursor protein; BACE, β-site APP-cleaving enzyme; Bz-LLL-COCHO, benzoyl-Leu-Leu-Leu-glyoxal; MOCA, modifier of cell-adhesion protein; Suc-LLVY-AMC, succinoyl-Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-amino-4-methylcoumarin; Z-DEVD-FMK, benzyloxycarbonyl-Val-Ala-DL-Asp-fluoromethylketone

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer's disease is characterized by the presence of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the brains of affected individuals. Amyloid plaques contain aggregated forms of Aβ (β-amyloid) peptide, derived from APP (amyloid precursor protein) upon sequential cleavage by the proteolytic activities of β- and γ-secretase, generating the N- and C- termini of Aβ respectively (for review see [1]). β-Secretase activity has been attributed to at least one protease, BACE (β-site APP-cleaving enzyme) [2], while γ-secretase activity involves a 220–250 kDa protein complex, including presenilin 1, nicastrin, APH-1 and PEN-2 [3,4]. All four member proteins are necessary for γ-secretase activity [5].

The proteasome is a large protease complex responsible for intracellular degradation of misfolded, oxidized or aggregated proteins. Aging impairs proteasome function at several levels, with effects on proteasome expression, activity and response to oxidative stress [6–8]. Proteasome activity is also reduced in brains of individuals affected by Alzheimer's disease [9], as are the activity and expression of the ubiquitin-activating (E1) and ubiquitin-conjugating (E2) enzymes [10], necessary for targeting proteins to the proteasome by covalent conjugation of ubiquitin. Molecular misreading of ubiquitin also increases with age, and in Alzheimer's disease, resulting in the production of a ubiquitin(+1) frameshift mutant, which cannot ubiquitinate, and also inhibits the proteasome [11]. APP, presenilin and PEN-2 are all proteasome substrates [12–14].

A number of previous studies have reported that proteasome inhibition altered APP processing, causing either an increase [12,13,15–18] or a decrease [19] in Aβ production. The mechanism by which proteasome inhibition influences Aβ production is unknown. The fact that Aβ production from the full-length APP used in a number of these studies [15,16,18,19] is influenced by both β- and γ-secretase activities makes it difficult to determine which activity is influenced by proteasome inhibition.

Proteasome inhibition can induce a number of different effects in cells. These include cell-cycle arrest, leading to apoptosis (with caspase 3 activation) in proliferating cells, or differentiation of neuroblastoma cells; and it can also inhibit apoptosis in terminally differentiated cells (see [20] for a recent review). Inhibition of the proteasome has been shown to induce apoptotic cell death in some neuronal and neuroblastoma cells via a mechanism involving caspase activation [21–23]. APP is a caspase 3 substrate, and the resulting product was reported to be more likely to be processed to produce Aβ, than non-caspase-cleaved APP [24,25].

The present study investigated whether inhibition of the proteasome in the human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y-SPA4CT cell line affected Aβ levels detected in cell culture medium. This cell line is stably transfected with the C-terminal 100 residues of APP, plus the signal peptide [26]. The formation of Aβ in these cells does not require β-secretase activity. This allowed the effects of proteasome inhibition on γ-secretase activity to be studied in isolation. The present study also investigated whether any proteasome-inhibitor-mediated effects on γ-secretase activity could result from caspase activation.

EXPERIMENTAL

Cell culture

The SH-SY5Y-SPA4CT cell line [26] was kindly provided by Dr Tobias Hartmann, Center for Molecular Biology, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany. This cell line expresses the SPA4CT construct, encoding the APP signal sequence and two additional residues from APP695 (leucine and glutamate) in frame with the Aβ peptide sequence and the entire C-terminal domain of APP [26]. Cells were maintained in a humidified 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator in 50% Ham's F12 and 50% minimum essential medium supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum, non-essential amino acids, 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco BRL/Life Technology). Cells were harvested by brief exposure to PBS containing 1 mM EDTA, suspension in PBS, and centrifugation at 1000 g for 5 min.

Inhibitors

Two inhibitors of the proteasome were used in the present study. Bz-LLL-COCHO (benzoyl-Leu-Leu-Leu-glyoxal), synthesized in-house, is a reversible inhibitor of the chymotrypsin-like activity of the proteasome [27]. Lactacystin (Affiniti Research Products, Mamhead Castle, Mamhead, Exeter, Devon, U.K.) is a Streptomyces metabolite that inhibits the trypsin-like and chymotrypsin-like activities of the proteasome irreversibly [28]. Z-DEVD-FMK (benzyloxycarbonyl-Val-Ala-DL-Asp-fluoromethylketone) (BioVision, Mountain View, CA, U.S.A.) was used to inhibit caspase 3 activity. It may also affect the activity of other caspases and we therefore refer to it as a DEVDase/caspase inhibitor, rather than a specific caspase 3 inhibitor. This inhibitor was added to cell culture medium to give a final concentration of 2 μM.

Aβ quantification

SH-SY5Y-SPA4CT cells were grown in six-well plates and were exposed to the inhibitors (in duplicate wells) for the times indicated. Medium (1.4 ml) was collected, AEBSF [4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulphonyl fluoride] was added to a concentration of 1 mM, before freezing immediately and storing at −75 °C until Aβ assay. Three different methods for quantifying Aβ were used. These will be referred to as Aβ40 ELISA-G2-10, Aβ42 ELISA-G2-11 and Aβ40 ELISA-Biosource.

Aβ40 ELISA-G2-10 and Aβ42 ELISA-G2-11

These assays were performed as described previously [29] using WO-2 as a capture antibody, with a biotinylated detection antibody (G2-10 for Aβ40 and G2-11 for Aβ42). Horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin binding was quantified using o-phenylenediamine (Sigma, Stockholm, Sweden) and read in an Emax plate reader (Molecular Devices). Aβ standard curves were prepared from 1 mg/ml stock solutions [70% methanoic (formic) acid, stored at −70 °C for 1 day] of Aβ 1–40 and Aβ 1–42 peptides (Biopolymer Laboratory, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, U.S.A.), diluted in ELISA buffer (0.4% ELISA blocking reagent, 0.2% BSA, 2% Tween 20, 2% goat serum in PBS). Cell culture medium was diluted 1:2 in ELISA buffer for the Aβ40 assay and was used undiluted for the Aβ42 assay.

Aβ40 ELISA-Biosource

This assay was performed using the Signal Select Human Aβ 1–40 ELISA assay, colorimetric (Biosource), according to the manufacturer's instructions, and the signal was read using a Multiscan MS plate reader (Labsystems). The Aβ standard curve was prepared from a 1 μg/ml stock solution of Aβ 1–40. Conditioned medium was diluted 1:2 in standard/sample diluent (including AEBSF at a final concentration of 1 mM). Accordingly, buffer used to dilute standards was 50% standard/sample diluent, 50% fresh cell culture medium.

Assay of proteasome activity in cell lysates

SH-SY5Y-SPA4CT cells were grown in culture to approx. 70% confluence, before exposure to inhibitors, as indicated above. Cells were washed with PBS, harvested, suspended in 50 mM Tris/HCl, and sonicated for 5 s to lyse the cells. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford method. Proteasome activity was assayed by incubating 30 μg of protein with the proteasome substrate Suc-LLVY-AMC (succinoyl-Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-amino-4-methylcoumarin) (Affiniti Research Products) (20 μM) in a total volume of 100 μl of assay buffer (0.38 mM EDTA and 50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5) at 37 °C for 4 h, followed by a 10 min incubation at 99 °C to stop the reaction. As a negative control, 30 μg of a cell lysate protein sample was boiled for 10 min before assay. AMC (amino-4-methylcoumarin) liberated from the substrate by proteasome activity was determined by measuring fluorescence (excitation, 380 nm; emission, 450 nm; Molecular Devices SpectraMax Gemini XS), and reading from an AMC standard curve.

Assay of DEVDase/caspase activity in cell lysates

SH-SY5Y-SPA4CT cells were grown in 75 cm2 flasks, exposed to inhibitors for the times indicated, the cells were harvested and lysed by three cycles of freeze–thawing in 100 μl of buffer (25 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 2 mM AEBSF, 10 μg/ml pepstatin A and 10 μg/ml leupeptin) and centrifugation at 14000 g for 10 min. Protein concentrations in the supernatant were determined using the Bradford method. Caspase activity was assayed using the Promega Casp-ACE™ Assay System, Fluorometric (96-well format), according to the manufacturer's instructions. This system employs a substrate [Ac-DEVD-AMC (N-acetyl-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin), 50 μM] and inhibitor [Ac-DEVD-CHO (N-acetyl-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp aldehyde), 50 μM] selective for CPP32/caspase 3 activity. DEVD may also be cleaved by other caspases, and we therefore refer to the activity detected as ‘DEVDase/caspase activity’, rather than caspase 3 activity. Sample protein (60 μg) was assayed for DEVDase/caspase activity in the presence and absence of inhibitor. Fluorescent signal was measured following 1 h of incubation at 37 °C (excitation 360 nm; emission 460 nm; Molecular Devices SpectraMax Gemini XS). Specific DEVDase/caspase activity was calculated from the difference in fluorescent signal in the presence and absence of inhibitor (Ac-DEVD-CHO), and expressed as activity per μg of cell lysate protein per min.

Neutral Red assay of cell viability

A Neutral Red assay was used to determine whether lactacystin was cytotoxic to SH-SY5Y-SPA4CT cells. Cells were plated in a 96-well plate and were incubated in normal growth medium for 24 h. This medium was then replaced by treatment medium containing various lactacystin concentrations. Following 24 h of incubation, the treatment medium was replaced by 200 μl of growth medium containing 50 μg/μl Neutral Red (Sigma). The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 4 h, medium was removed, and cells were fixed for 30 s with 200 μl of formaldehyde fixative (1% CaCl2 and 4% formaldehyde in water). A 200 μl volume of 50% ethanol and 1% ethanoic (acetic) acid in water was added to dissolve the dye taken up by the cells, and the plates were read at 550 nm (Labsystems Multiscan MS plate reader). Absorbance at 550 nm indicates the amount of Neutral Red that has been taken into cells by endocytosis, and is directly proportional to cell viability.

RESULTS

Effect of proteasome inhibition on Aβ levels in cell culture medium

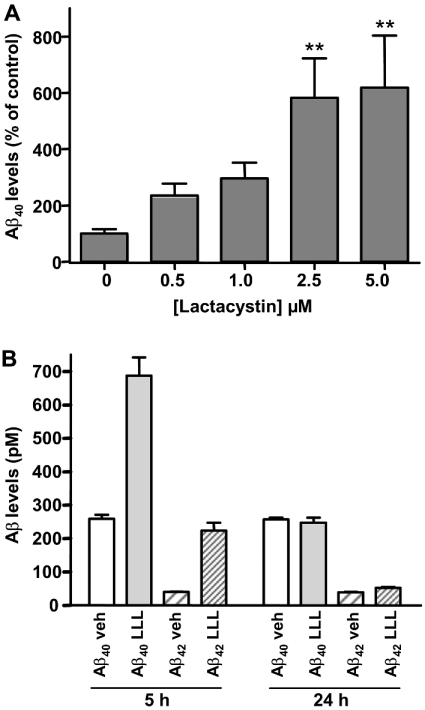

Cells were exposed to lactacystin (0.5–5 μM) for 4 and 24 h. Aβ40 ELISA-Biosource analysis of medium revealed increases in Aβ levels at 4 h. These were statistically significant at a concentration of 1.0 μM lactacystin (Fisher's protected least-squares difference, P=0.014). Increases in Aβ40 levels were more marked at 24 h and were statistically significant at concentrations of both 2.5 and 5 μM lactacystin (Figure 1A). This effect was also seen when medium from SH-SY5Y-SPA4CT cells treated with lactacystin was assayed for Aβ40 using the Aβ40 ELISA-G2-10. In the presence of 5 μM lactacystin, Aβ40 levels were 227% of control at 5 h, and 580% of control at 24 h. To confirm that this effect resulted from proteasome inhibition, SH-SY5Y-SPA4CT cells were also exposed to another proteasome inhibitor, Bz-LLL-COCHO (5 μM) for 5 and 24 h, and Aβ was assayed using the Aβ40 ELISA-G2-10 and Aβ42 ELISA-G2-11 methods. The levels of both Aβ40 and Aβ42 in cell culture medium were increased at 5 h, to 265 and 560% of control respectively (Figure 1B). The Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio was also increased from 1:6.5 in untreated cells to 1:3 in cells treated with 5 μM Bz-LLL-COCHO for 5 h. After 24 h of exposure to Bz-LLL-COCHO, Aβ levels had returned towards those seen in control cells (Aβ40, 96% of control; Aβ42, 131% of control; Figure 1B). The effect of lactacystin was therefore maintained for longer than Bz-LLL-COCHO, and larger increases in Aβ levels were observed at 24 h (Figure 1). This is consistent with the activities of these compounds as proteasome inhibitors, since Bz-LLL-COCHO is a reversible inhibitor and lactacystin is an irreversible inhibitor.

Figure 1. Effects of proteasome inhibitors of Aβ levels in cell culture medium.

(A) Concentration-dependent effects of lactacystin on Aβ40 levels. Aβ40 levels in conditioned medium from SH-SY5Y-SPA4CT cells incubated for 24 h with lactacystin at the concentrations indicated, measured by Aβ40 ELISA-Biosource. Values indicated are means±S.E.M. for three separate experiments with duplicate cell cultures, each assayed in duplicate for Aβ40 (12 Aβ40 assays at each concentration of lactacystin). **P<0.01 by Fisher's protected least-squares difference, compared with control Aβ40 levels. (B) Effect of Bz-LLL-COCHO on Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels. Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels (pM) in conditioned medium from SH-SY5Y-SPA4CT cells incubated for 5 or 24 h with Bz-LLL-COCHO (LLL) (5 μM), or vehicle (veh) control, were quantified using Aβ40 ELISA-G2-10 and Aβ42 ELISA-G2-11. The treatment is indicated below the bar, along with the relevant Aβ peptide. Values indicated are means±S.D. for two cell cultures, each assayed in duplicate for Aβ40 or Aβ42.

As a control experiment, we also assayed medium conditioned by untransfected SH-SY5Y cells for Aβ. The ELISAs described did not detect any Aβ40 in SH-SY5Y medium under these conditions, indicating that less than 2 pM Aβ40 (the most abundant Aβ peptide secreted by the cells) was present. The presence of much higher levels of Aβ40 in medium conditioned by SHSY-5Y-SPA4CT (>200 pM; Figure 1B) confirmed that the SPA4CT construct was robustly expressed in this cell line.

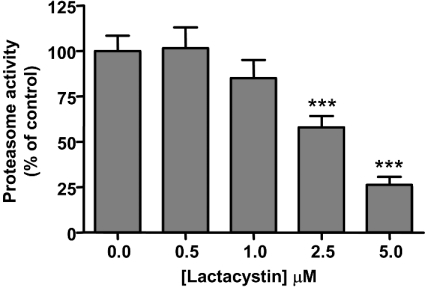

Effect of lactacystin on proteasome activity

Inhibition of the proteasome by lactacystin was confirmed by measuring the chymotrypsin-like activity of the proteasome in SH-SY5Y-SPA4CT cell lysate protein, by assaying cleavage of Suc-Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-AMC. This proteasome activity was inhibited to approx. 40% of control by treatment with 1.0, 2.5 or 5.0 μM lactacystin for 3 h (results not shown). This effect was lost by 24 h in the presence of 0.5 and 1 μM lactacystin, perhaps indicating new proteasome synthesis to overcome the inhibition. Cells exposed to lactacystin concentrations of 2.5 and 5.0 μM still displayed proteasome inhibition at 24 h (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Concentration-dependent effects of lactacystin on proteasome activity in cell lysates.

SH-SY5Y-SPA4CT cells were incubated with lactacystin at the concentrations indicated for 24 h before proteasome activity was assayed using the fluorogenic substrate, Suc-Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-AMC, as described in the Experimental section. Results are means±S.E.M. for six cell cultures, each assayed in duplicate for proteasome activity in 30 μg of cell lysate protein (12 proteasome assays at each concentration of lactacystin). ***P<0.001 by Fisher's protected least-squares difference, compared with control proteasome activity.

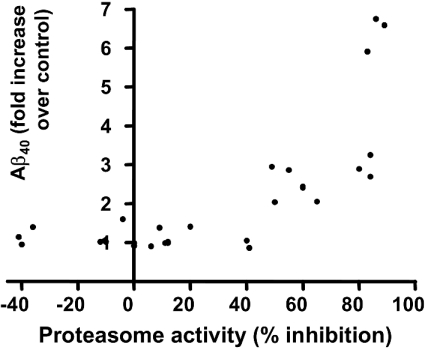

Correlation between proteasome inhibition and Aβ levels

Proteasome activity and Aβ40 levels were analysed simultaneously in the cell lysate protein and medium (respectively) of the same SHSY-5Y-SPA4CT cultures. Aβ40 levels (fold increase over control) were plotted against proteasome activity (percentage inhibition by a range of concentrations of either Bz-LLL-COCHO or lactacystin), as shown in Figure 3. This demonstrated that reductions in proteasome activity of up to approx. 40% were not generally associated with any increase in Aβ40 levels. When proteasome activity was inhibited by more than 50%, levels of Aβ40 began to rise significantly. This suggested that a threshold inhibition of proteasome activity by approx. 50% was necessary before the effects on SPA4CT processing became apparent.

Figure 3. Relationship between proteasome inhibition and Aβ40 levels.

Aβ40 levels in conditioned culture medium were plotted against proteasome activity in the cell lysate of the same SH-SY5Y-SPA4CT cell culture, following incubation with various proteasome inhibitor concentrations. Assays were performed as described in Figures 1 and 2. A reduction in proteasome activity by ≥50% was required to significantly increase Aβ40 levels.

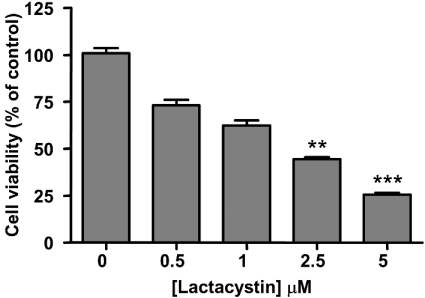

Effect of lactacystin on SH-SY5Y-SPA4CT cell viability

The viability of this cell line during lactacystin treatment was determined using the Neutral Red assay. Results showed that exposure to ≥2.5 μM lactacystin (for 24 h) caused statistically significant, concentration-dependent, reductions in cell viability (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Concentration-dependent effects of lactacystin on cell viability.

SH-SY5Y-SPA4CT cell viability was determined using the Neutral Red assay, following exposure to the indicated concentrations of lactacystin for 24 h. Results are means±S.E.M. (n=7). **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 by Dunn's Multiple Comparison Test, for the comparison with the control (no lactacystin).

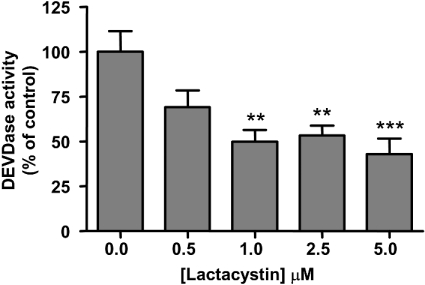

Effect of lactacystin on DEVDase/caspase activity

To investigate whether the observed increases in Aβ levels during proteasome inhibition could result from the activation of apoptosis, DEVDase/caspase activity was assayed in lactacystin-treated cells. Cells exposed to lactacystin did not show increased DEVDase/caspase activity. Instead, decreased DEVDase/caspase activity was observed (Figure 5). Statistically significant (P=0.01), greater than 50% decreases in DEVDase/caspase activity were seen in cells exposed to lactacystin concentrations of ≥1 μM for 24 h (Figure 5). This result demonstrated that the increased levels of Aβ in the presence of lactacystin did not result from increased APP cleavage by caspase 3.

Figure 5. Effects of lactacystin on DEVDase/caspase activity in cell lysates.

SH-SY5Y-SPA4CT cells were exposed to the indicated concentrations of lactacystin for 24 h, before determination of DEVDase/caspase activity in 60 μg of cell lysate protein, using the Promega CaspACE™ Assay System. Results are means±S.E.M. for two separate experiments with duplicate cell cultures, each assayed in duplicate (eight DEVDase/caspase assays at each concentration of lactacystin). **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 by Fisher's protected least-squares difference, compared with the control.

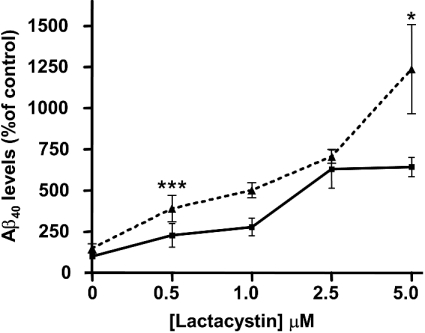

Effect of DEVDase/caspase inhibition on lactacystin-induced increases in Aβ levels

To confirm that caspase activity was not required for lactacystin-induced increases in Aβ levels, we also exposed cells to a cell-permeant DEVDase/caspase inhibitor, Z-DEVD-FMK (2 μM), in the presence and absence of lactacystin. This experiment (Figure 6) confirmed the data presented in Figure 1, showing lactacystin-concentration-dependent increases in Aβ40 levels in SH-SY5Y-SPA4CT cell culture medium (approx. 6-fold increased with 2.5 μM lactacystin). In the presence of Z-DEVD-FMK, Aβ40 levels in the medium actually increased, demonstrating that DEVDase/caspase activation was not required for lactacystin-mediated increases in Aβ40 levels, and suggesting that caspase 3 inhibition may in fact increase Aβ40 levels. Indeed, in the presence of 2 μM Z-DEVD-FMK alone, Aβ40 levels were 148% of control. Aβ40 levels were higher in cells exposed to Z-DEVD-FMK and lactacystin, as compared with lactacystin alone. This effect was statistically significant in cells exposed to 0.5 μM and 5 μM lactacystin for 24 h (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Effects of Z-DEVD-FMK on lactacystin-mediated increases in Aβ40 levels.

SH-SY5Y-SPA4CT cells were exposed to lactacystin at the concentrations indicated for 24 h in the presence (broken line) or absence (solid line) of the DEVDase/caspase 3 inhibitor Z-DEVD-FMK (2 μM). Aβ40 levels in conditioned medium were determined using the Aβ40 ELISA Biosource method. Results are means±S.E.M. for five cell cultures, assayed in duplicate for Aβ40. *P<0.05 and ***P<0.0001, for comparison between cells exposed to Z-DEVD-FMK and lactacystin, and cells exposed to lactacystin alone.

DISCUSSION

Proteasome inhibition increased Aβ levels in medium conditioned by the SH-SY5Y-SPA4CT cell line, where only γ-secretase activity was required to generate Aβ. Levels of Aβ40 and Aβ42 in cell culture medium were significantly increased in the presence of two different proteasome inhibitors, Bz-LLL-COCHO and lactacystin, and the extent of increase in Aβ correlated with the percentage proteasome inhibition (above a threshold of 50% inhibition). This increase in Aβ levels upon proteasome inhibition is consistent with previous studies [12,13,15–18], but the mechanism involved is unclear. The present study investigated one potential mechanism, by testing the hypothesis that proteasome inhibition induced apoptosis and caspase 3 activation, resulting in caspase 3 cleavage of APP. Caspase 3 can cleave full-length APP at residues 197, 219 and 720, and cleavage at Asp720 (the only potential cleavage site in the C100 region of APP expressed by the SH-SY5Y-SPA4CT cells) was shown to provide a better substrate for production of Aβ [24,25]. Proteasome inhibition can induce apoptosis (with caspase 3 activation) in proliferating cells [20–23] (see the Introduction). In the present study, proteasome inhibition in SH-SY5Y-SPA4CT cells by lactacystin (>2.5 μM) induced cell death, but no increase in caspase activation was observed. In fact, DEVDase/caspase activity was actually reduced. The lactacystin-induced decrease in DEVDase/caspase activity occurred over the same concentration range as the increases in Aβ40 levels. Consequently, the observed increases in Aβ could not be attributed to increased caspase 3 cleavage at APP Asp720. This finding is consistent with other studies in CHO (Chinese-hamster ovary) cells indicating that (i) increases in Aβ release during staurosporine-induced apoptosis did not involve APP cleavage at any of the caspase sites [30], (ii) masking the Asp720 caspase site did not result in decreased Aβ levels [31], and (iii) caspase activation during serum withdrawal did not increase Aβ release [31]. To confirm this result, we co-treated cells with lactacystin and a DEVDase/caspase inhibitor, Z-DEVD-FMK. Interestingly, Z-DEVD-FMK significantly potentiated the lactacystin-induced increases in Aβ40 levels, and Aβ40 levels were also higher in the presence of Z-DEVD-FMK alone. This provided further evidence that caspase-mediated cleavage of APP was not responsible for the increased Aβ40 release.

Overexpression of APP has been reported to activate caspase 3 in neuronal cells [32]. We therefore compared basal DEVDase/caspase activity in the SH-SY5Y-SPA4CT cell line, and in the untransfected parent SH-SY5Y cells (results not shown). DEVDase/caspase activity was easily detected in these cell lines, but no increase in DEVDase/caspase activation was observed in the SPA4CT-transfected cells, as compared with the untransfected SH-SY5Y cells. In fact, basal activity was higher in the non-transfected (mean SH-SY5Y DEVDase activity was 113.6 pmol of AMC/mg of protein per min), compared with transfected cells (69.4 pmol of AMC/mg of protein per min).

Taken together, these results raise the possibility that reductions in DEVDase/caspase activity actually contributed to increased Aβ40 levels. In three different circumstances where cellular DEVDase/caspase activity was reduced (by proteasome inhibition, by exposure to Z-DEVD-FMK alone and the lower basal activity in the SPA4CT cells), Aβ40 levels in conditioned medium were increased.

The increase in the amount of APP C-100 that is cleaved by γ-secretase in the presence of proteasome inhibitors could reflect either a change in γ-secretase activity, or an increase in substrate availability. Despite some controversy in this area [19], a consensus is emerging that APP C-100 is processed along at least two independent pathways, one involving γ-secretase generation of Aβ, and the other involving the proteasome [12,33,34]. Membrane proteins can be retrotranslocated from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cytosol for destruction by the proteasome [35]. Proteasome-mediated cleavage of the C-terminal region of APP reduces the amount of APP processed by γ-secretase, and thus reduces Aβ production [12,33]. Overexpression of MOCA [modifier of cell-adhesion protein, also known as PBP (presenilin-binding protein)] increased the amount of APP processed via the proteasome, and resulted in decreased APP and Aβ secretion [36]. MOCA may thus direct APP to the proteasome, and since our results (and those of [12,33,34]) indicate that the C-100 region of APP is also processed via the proteasome, the MOCA-interaction site in APP may be in this region. The subcellular distribution of MOCA is altered in the brain in Alzheimer's disease, with reduced soluble fraction and increased particulate fraction levels, suggesting that delivery of APP to the proteasome may compromised in the disease [37].

Proteasome inhibition may also increase γ-secretase levels by reducing presenilin and PEN-2 turnover [12–14], although overexpression of presenilin alone does not result in increased levels of the biologically active γ-secretase complex [38]. Increased presenilin levels are, however, associated with re-localization of MOCA to the membrane [39]. This suggests that, if proteasome inhibition increases presenilin levels, the consequence is likely to be a decrease in the amount of APP targeted to the proteasome by MOCA, and hence an increase in γ-secretase substrate availability, rather than an increase in active γ-secretase levels. An effect on substrate availability for γ-secretase processing therefore seems the most likely explanation for the proteasome-inhibitor-mediated increases in Aβ levels observed here.

Proteasome activity declines with age, and is also impaired in Alzheimer's disease [6,8–11] (see the Introduction for further information). The present study indicates that decreased proteasome activity would increase Aβ levels, via an effect on γ-secretase mediated APP processing, and thereby increase risk for the neuropathological changes associated with Alzheimer's disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Tobias Hartmann, University of Heidelberg, for the SH-SY5Y-SPA4CT cell line, Dr Malene Jensen for ELISA-G2-10 and G2-11 assays, the Alzheimer's Society, UK, for the award of a Fellowship to J. A. J., and the Research and Development Office of the Department of Health, Social Services and Personal Safety, Northern Ireland, for research funding.

References

- 1.Esler W. P., Wolfe M. S. A portrait of Alzheimer secretases – new features and familiar faces. Science. 2001;293:1449–1454. doi: 10.1126/science.1064638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vassar R., Bennett B. D., Babu-Khan S., Kahn S., Mendiaz E. A., Denis P., Teplow D. B., Ross S., Amarante P., Loeloff R., et al. β-Secretase cleavage of Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein by the transmembrane aspartic protease BACE. Science. 1999;286:735–741. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5440.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu G., Nishimura M., Arawaka S., Levitan D., Zhang L., Tandon A., Song Y. Q., Rogaeva E., Chen F., Kawarai T., et al. Nicastrin modulates presenilin-mediated notch/glp-1 signal transduction and bitmap processing. Nature (London) 2000;407:48–54. doi: 10.1038/35024009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Francis R., McGrath G., Zhang J., Ruddy D. A., Sym M., Apfeld J., Nicoll M., Maxwell M., Hai B., Ellis M. C., et al. aph-1 and pen-2 are required for Notch pathway signaling, γ-secretase cleavage of β-APP, and presenilin protein accumulation. Dev. Cell. 2002;3:85–97. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00189-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edbauer D., Winkler E., Regula J. T., Pesold B., Steiner H., Haass C. Reconstitution of γ-secretase activity. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003;5:486–488. doi: 10.1038/ncb960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bulteau A. L., Petropoulos I., Friguet B. Age-related alterations of proteasome structure and function in aging epidermis. Exp. Gerontol. 2000;35:767–777. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00136-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keller J. N., Huang F. F., Markesbery W. R. Decreased levels of proteasome activity and proteasome expression in aging spinal cord. Neuroscience. 2000;98:149–156. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merker K., Grune T. Proteolysis of oxidised proteins and cellular senescence. Exp. Gerontol. 2000;35:779–786. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00140-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keller J. N., Hanni K. B., Markesbery W. R. Impaired proteasome function in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurochem. 2000;75:436–439. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopez Salon M., Morelli L., Castano E. M., Soto E. F., Pasquini J. M. Defective ubiquitination of cerebral proteins in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurosci. Res. 2000;62:302–310. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20001015)62:2<302::AID-JNR15>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Leeuwen F. W., de Kleijn D. P., van den Hurk H. H., Neubauer A., Sonnemans M. A., Sluijs J. A., Koycu S., Ramdjielal R. D., Salehi A., Martens G. J., et al. Frameshift mutants of β-amyloid precursor protein and ubiquitin-B in Alzheimer's and Down patients. Science. 1998;279:242–247. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5348.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nunan J., Shearman M. S., Checler F., Cappai R., Evin G., Beyreuther K., Masters C. L., Small D. H. The C-terminal fragment of the Alzheimer's disease amyloid protein precursor is degraded by a proteasome-dependent mechanism distinct from γ-secretase. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001;268:5329–5336. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.da Costa C. A., Ancolio K., Checler F. C-terminal maturation fragments of presenilin 1 and 2 control secretion of APPα and Aβ by human cells and are degraded by proteasome. Mol. Med. 1999;5:160–168. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bergman A., Hansson E. M., Pursglove S. E., Farmery M. R., Lannfelt L., Lendahl U., Lundkvist J., Naslund J. Pen-2 is sequestered in the endoplasmic reticulum and subjected to ubiquitylation and proteasome-mediated degradation in the absence of presenilin. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:16744–16753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313999200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamazaki T., Haass C., Saido T. C., Omura S., Ihara Y. Specific increase in amyloid β-protein 42 secretion ratio by calpain inhibition. Biochemistry. 1997;36:8377–8383. doi: 10.1021/bi970209y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marambaud P., Ancolio K., Lopez-Perez E., Checler F. Proteasome inhibitors prevent the degradation of familial Alzheimer's disease-linked presenilin 1 and potentiate Aβ 42 recovery from human cells. Mol. Med. 1998;4:147–157. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang L., Song L., Parker E. M. Calpain inhibitor I increases β-amyloid peptide production by inhibiting the degradation of the substrate of γ-secretase: evidence that substrate availability limits β-amyloid peptide production. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:8966–8972. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skovronsky D. M., Pijak D. S., Doms R. W., Lee V. M. A distinct ER/IC γ-secretase competes with the proteasome for cleavage of APP. Biochemistry. 2000;39:810–817. doi: 10.1021/bi991728z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christie G., Markwell R. E., Gray C. W., Smith L., Godfrey F., Mansfield F., Wadsworth H., King R., McLaughlin M., Cooper D. G., et al. Alzheimer's disease: correlation of the suppression of β-amyloid peptide secretion from cultured cells with inhibition of the chymotrypsin-like activity of the proteasome. J. Neurochem. 1999;73:195–204. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0730195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drexler H. C. The role of p27Kip1 in proteasome inhibitor induced apoptosis. Cell Cycle. 2003;2:438–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lopes U. G., Erhardt P., Yao R., Cooper G. M. p53-dependent induction of apoptosis by proteasome inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:12893–12896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.12893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pasquini L. A., Besio Moreno M., Adamo A. M., Pasquini J. M., Soto E. F. Lactacystin, a specific inhibitor of the proteasome, induces apoptosis and activates caspase-3 in cultured cerebellar granule cells. J. Neurosci. Res. 2000;59:601–611. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(20000301)59:5<601::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qiu J. H., Asai A., Chi S., Saito N., Hamada H., Kirino T. Proteasome inhibitors induce cytochrome c–caspase-3-like protease-mediated apoptosis in cultured cortical neurons. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:259–265. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00259.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barnes N. Y., Li L., Yoshikawa K., Schwartz L. M., Oppenheim R. W., Milligan C. E. Increased production of amyloid precursor protein provides a substrate for caspase-3 in dying motoneurons. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:5869–5880. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-15-05869.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gervais F. G., Xu D., Robertson G. S., Vaillancourt J. P., Zhu Y., Huang J., LeBlanc A., Smith D., Rigby M., Shearman M. S., et al. Involvement of caspases in proteolytic cleavage of Alzheimer's amyloid-β precursor protein and amyloidogenic Aβ peptide formation. Cell. 1999;97:395–406. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80748-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dyrks T., Dyrks E., Monning U., Urmoneit B., Turner J., Beyreuther K. Generation of βA4 from the amyloid protein precursor and fragments thereof. FEBS Lett. 1993;335:89–93. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80446-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lynas J. F., Harriott P., Healy A., McKervey M. A., Walker B. Inhibitors of the chymotrypsin-like activity of proteasome based on di- and tri-peptidyl α-keto aldehydes (glyoxals) Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1998;8:373–378. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(98)00030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fenteany G., Standaert R. F., Lane W. S., Choi S., Corey E. J., Schreiber S. L. Inhibition of proteasome activities and subunit-specific amino-terminal threonine modification by lactacystin. Science. 1995;268:726–731. doi: 10.1126/science.7732382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jensen M., Schroder J., Blomberg M., Engvall B., Pantel J., Ida N., Basun H., Wahlund L. O., Werle E., Jauss M., et al. Cerebrospinal fluid Aβ42 is increased early in sporadic Alzheimer's disease and declines with disease progression. Ann. Neurol. 1999;45:504–511. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199904)45:4<504::aid-ana12>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tesco G., Koh Y. H., Tanzi R. E. Caspase activation increases β-amyloid generation independently of caspase cleavage of the β-amyloid precursor protein (APP) J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:46074–46080. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307809200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soriano S., Lu D. C., Chandra S., Pietrzik C. U., Koo E. H. The amyloidogenic pathway of amyloid precursor protein (APP) is independent of its cleavage by caspases. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:29045–29050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102456200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uetsuki T., Takemoto K., Nishimura I., Okamoto M., Niinobe M., Momoi T., Miura M., Yoshikawa K. Activation of neuronal caspase-3 by intracellular accumulation of wild-type Alzheimer amyloid precursor protein. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:6955–6964. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-16-06955.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nunan J., Williamson N. A., Hill A. F., Sernee M. F., Masters C. L., Small D. H. Proteasome-mediated degradation of the C-terminus of the Alzheimer's disease β-amyloid protein precursor: effect of C-terminal truncation on production of β-amyloid protein. J. Neurosci. Res. 2003;74:378–385. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bunnell W. L., Pham H. V., Glabe C. G. γ-Secretase cleavage is distinct from endoplasmic reticulum degradation of the transmembrane domain of the amyloid precursor protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:31947–31955. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.31947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsai B., Ye Y., Rapoport T. A. Retro-translocation of proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum into the cytosol. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;3:246–255. doi: 10.1038/nrm780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen Q., Kimura H., Schubert D. A novel mechanism for the regulation of amyloid precursor protein metabolism. J. Cell Biol. 2002;158:79–89. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200110151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen Q., Schubert D. Presenilin-interacting proteins. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2002;4:1–18. doi: 10.1017/S1462399402005008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thinakaran G., Harris C. L., Ratovitski T., Davenport F., Slunt H. H., Price D. L., Borchelt D. R., Sisodia S. S. Evidence that levels of presenilins (PS1 and PS2) are coordinately regulated by competition for limiting cellular factors. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:28415–28422. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kashiwa A., Yoshida H., Lee S., Paladino T., Liu Y., Chen Q., Dargusch R., Schubert D., Kimura H. Isolation and characterization of novel presenilin binding protein. J. Neurochem. 2000;75:109–116. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]