Abstract

Background

Community health centers grapple with high no-show rates, posing challenges to patient access and primary care provider (PCP) utilization.

Aim

To address these challenges, we implemented a virtual waiting room (VWR) program in April 2023 to enhance patient access and boost PCP utilization.

Setting

Academic community health center in a small urban city in Massachusetts.

Participants

Community health patients (n = 8706) and PCP (n = 14).

Program Description

The VWR program, initiated in April 2023, involved nurse triage of same-day visit requests for telehealth appropriateness, then placing patients in a standby pool to fill in as a telehealth visit for no-shows or last-minute cancellations in PCP schedules.

Program Evaluation

Post-implementation, clinic utilization rates between July and September improved from 75.2% in 2022 to 81.2% in 2023 (p < 0.01). PCP feedback was universally positive. Patients experienced a mean wait time of 1.9 h, offering a timely and convenient alternative to urgent care or the ER.

Discussion

The VWR is aligned with the quadruple aim of improving patient experience, population health, cost-effectiveness, and PCP satisfaction through improving same-day access and improving PCP schedule utilization. This innovative and reproducible approach in outpatient offices utilizing telehealth holds the potential for enhancing timely access across various medical disciplines.

KEY WORDS: virtual waiting room, patient access, primary care provider utilization, quadruple aim, academic community health center

INTRODUCTION

Academic community health centers, as safety-net facilities providing primary care for communities facing healthcare disparities, play a crucial role in achieving the Quadruple Aim, which seeks to improve patient experience, population health, cost-effectiveness, and primary care provider (PCP) satisfaction.1 However, these centers face a significant challenge: a high missed appointment rate, averaging 27% in the USA.2 This undermines consistent care, disrupts care continuity, and strains healthcare resources, negatively impacting patient experience and population health.3

Missed appointments also impose a significant financial burden, costing the healthcare system up to $150 billion annually in lost revenue.4 Interventions like reminder calls, letters, and proactive scheduling strategies have shown limited success in addressing this issue.5 The adoption of telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic also proved effective in reducing missed appointments, increasing access to care, and decreasing patient wait times.6,7

Despite these efforts, challenges persist. Emergency departments (EDs) often experience volume overflow due to low emergency severity index visits, frequently linked to limited primary care access. This underscores the need for comprehensive solutions to optimize healthcare access and mitigate the repercussions of missed appointments.

SETTING AND PARTICIPANTS

High Street Health Center, our teaching health center in Springfield, Massachusetts, serves a diverse urban community of 8706 patients. Our payer mix includes 54.2% Medicaid Accountable Care Organization (ACO) and 36.5% Medicare ACO patients. We are an interprofessional academic teaching center for Internal Medicine residents, medical students, and advanced practice students. Our no-show rates mirror the national average for health centers largely due to socioeconomic barriers such as limited transportation, childcare constraints, housing instability, and work obligations.

Our institution set a system-wide goal of 88% for appointment utilization. However, high no-show rates made it difficult for us to meet this target, impacting the health center’s efficiency and reducing patient access to care. To address these challenges, we created a virtual waiting room (VWR) pool, within our electronic medical record (EMR), Cerner, for same-day telehealth urgent appointments. This innovation was strategically designed to fill the gaps in PCP schedules caused by no-shows or last-minute cancellations.

The pilot began in April 2023 with two High Street Health Center PCPs (one attending physician and one advanced practitioner). By June 2023, the project was extended to all 14 clinicians. Initially, the VWR pool was capped at ten patients per day to ensure capacity. As the project expanded to include all attendings and advanced practitioner PCPs, this limit was increased to 20 patients per day. Concurrently, we transitioned from a mix of 20-min and 40-min appointment slots (with a maximum of 12 patients per session) to a uniform 30-min appointment template that limited sessions to eight patients. This shift not only simplified the implementation of the VWR by streamlining scheduling but also fostered greater PCP engagement.

Our goal was to ensure that our patients received care within our practice rather than resorting to urgent care or the ED. This proactive engagement aligned with the overarching healthcare objectives and promoted a more comprehensive patient-centric care experience. The VWR implementation aimed to improve care delivery and foster greater PCP engagement in addressing no-show rates and ensuring consistent patient care.

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION

The VWR pool was utilized through a structured process:

Triage by Phone: When health center patients contacted our office with acute concerns, our skilled nurses conducted a thorough triage over the phone to assess telehealth appropriateness. Patients were informed that a clinician would contact them within 24 h to address their issues.

Placement into the VWR Pool: If telehealth was deemed suitable, the patient’s name was added to the VWR pool within our EMR, ensuring a systematic and organized approach to managing virtual visits.

Utilizing No-Show Slots: If a scheduled patient failed to present within their 15-min grace period, PCPs proactively accessed the VWR pool to fill the slot. Clinicians had the flexibility to choose from three methods: (1) first-come-first-serve or giving preference to those who were in the VWR pool the longest, (2) selecting their own PCP patients, or (3) prioritizing high-need patients with acute issues that required timely responses. This approach allowed for efficient allocation of resources and personalized care delivery.

Late Afternoon and Friday Considerations: For patients placed in the VWR pool later in the day or on a Friday afternoon, our triage nurses informed them that a clinician would reach out the following day or on Monday, respectively. This managed patient expectations and ensured they were aware of potential delays.

Urgent Care or Emergency Room Guidance: Throughout the waiting period, all VWR patients were advised to seek care at urgent care or the ER if their condition worsened. This precautionary measure emphasized patient safety and addressed the urgency of certain health concerns.

This structured process optimized telehealth use and facilitated clear patient communication, fostering a patient-centered approach to care access.

PROGRAM EVALUATION

Our Institutional Review Board exempted this quality improvement project from formal review. Following the implementation of the VWR, our weekly appointment utilization rate improved significantly, from 76% to a peak of 94%. This positive trend continued, with year-end average utilization increasing from 75% in FY22 to 80% in FY23, indicating the VWR’s sustained impact.

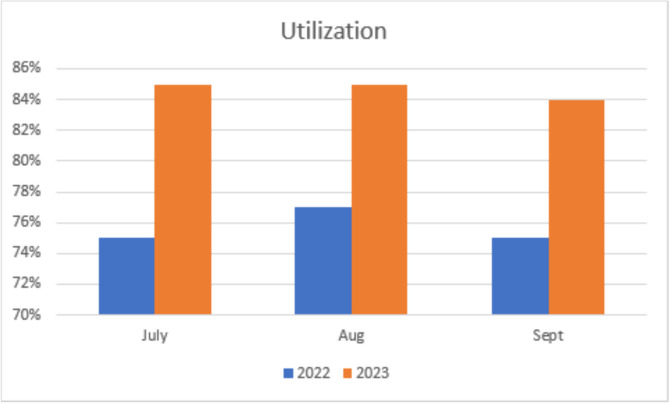

To assess clinician-level utilization, we compared data from July to September in FY23 (post-implementation) with the same period in FY22 (pre-implementation), controlling for seasonality. This time frame covers summer to early fall, when health centers may experience variations in patient flow due to factors like vacations, school schedules, and seasonal conditions. We observed a statistically significant increase in clinic utilization rates from 75.2% (SD 2.7) to 81.2% (SD 3.3), with a p-value < 0.01 (see Fig. 1). Most telehealth visits during this period addressed acute concerns such as otolaryngological infections, anxiety, tick bites, allergy symptoms, and asthma or emphysema exacerbations, which tend to be more prevalent in the summer and early fall.

Figure 1.

Comparison of Provider utilization between 2022 and 2023.

Over the 3-month study period, the VWR served 659 patients. To gain insight into patient experiences and population diversity, we conducted a chart review of the first 100 patients treated via the VWR. This sample size was chosen to provide a comprehensive and representative overview of patient encounters. Among these 100 patients, 76% were able to secure telehealth visits on the same day they called, with a mean wait time of 1.9 h (SD 1.6). Additionally, 1% were directed to the ED, while 61% were prescribed medication, 17% received referrals, and 25% underwent diagnostic tests. Moreover, 8% had an in-person follow-up visit, and 1% had an ED visit within 2 weeks of the VWR encounter.

To gauge clinician experience with the VWR program, we conducted a two-question, open-ended survey asking: “Did you find the VWR implementation valuable? In what way?” and “Would you recommend this to others?” All surveyed clinicians expressed positive sentiments, indicating that the VWR enhanced patient access and increased productivity. Several comments highlighted the professional satisfaction derived from the VWR, as it gave PCPs more control over their clinic sessions, allowing them to fill open slots and “help [patients] avoid unnecessary visits to urgent care or the ER”, thereby “improving urgent care access for our patients.” Triage RNs echoed these views, describing the VWR as a “godsend.” One triage nurse commented, “When we’re without appointments… to offer patients, the [VWR] is a great alternative”. This approach also reduced the demands placed on triage nurses, offering a more efficient approach to addressing patients’ acute concerns.

DISCUSSION

The VWR effectively addressed low utilization resulting from frequent last-minute cancellations and no-shows at our health center, which often redirected patients to seek care in urgent care or the ER, impeding timely primary care. By prioritizing equitable and accessible care for our Medicaid-insured population, our post-implementation capacity to provide such care significantly improved. With 54% of our patient population being Medicaid-insured individuals under a value-based capitated contract with our Medicaid ACO, telehealth visits were facilitated with nominal reimbursement concerns. Additionally, to ensure equitable care, we extended access through audio-only visits for those with limited digital literacy, and inadequate technology or internet services, thereby accommodating patients with transportation or mobility challenges.

However, the program is not without limitations. Firstly, the single-site setting of our program may limit the generalizability of our results to other healthcare settings. The effectiveness of the VWR may vary in health centers with different patient demographics, organizational structures, or patient volume flow. Maintaining a steady flow of open appointment slots, essential for the success of the VWR, may pose challenges for health centers with lower patient volumes or different patient schedule patterns. Additionally, our study excluded internal medicine residents from the implementation of the VWR program, limiting the assessment of its impact on interdisciplinary care delivery and medical education. Future iterations of the program should include residents for a more comprehensive understanding of its implications. Furthermore, the evaluation process lacked direct patient feedback and input from all staff involved in the VWR process, such as medical assistants and patient service representatives, which could have provided valuable insights into patient satisfaction, operational challenges, and workflow dynamics.

In addition to these limitations, it is important to recognize the inherent limitations of telehealth itself, including the inability to take vital signs or conduct a comprehensive physical exam.8,9 However, our hybrid care model, utilizing telehealth for initial assessments and transitioning patients for in-person follow-ups when needed, mitigates these concerns by providing timely in-office visits for those patients requiring further evaluation. This hybrid model, prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic, aligns with the Quadruple Aim by enhancing patient experience, improving clinician satisfaction, optimizing resource utilization, and positively impacting population health.

In our initial 100-patient chart review, 8% had an in-person follow-up visit and 1% had an ED visit within 2 weeks of the VWR encounter. This finding aligns with a recent study by Laub et al., which showed a 9.7% 1-week in-person follow-up after a telephone primary care visit.10 While the sample of 100 patients provided valuable insights, longer-term studies are needed to fully assess the VWR’s sustainability and its broader impact on patient diversity and outcomes.

The VWR has also alleviated the overwhelming influx of inbox messages from patients seeking medical advice or medications when same-day visits were unavailable. By enabling PCPs to address patient concerns directly, the VWR reduces unreimbursed after-hours work, ensuring timely care for patients while acknowledging the asynchronous clinical work of PCPs.

Financially, the VWR supports our objective of improving care access under our capitated ACO agreement, with minimal, if any, direct impact on the health center’s finances. While telehealth visits might raise revenue concerns under fee-for-service arrangements, these patients would otherwise have sought care at urgent care or the ER due to unavailable same-day appointments. Thus, any potential lost revenue from telehealth visits is offset by the fact that these urgent care or ER visits did not directly contribute to our revenue stream.

Our primary outcome, which focused on population health through schedule management, demonstrated significant improvement in utilization rates, thereby reinforcing the value of keeping patient care within the health center. Our observations indicate a positive trend in diverting patients from emergency facilities, enabling PCPs to address acute issues promptly, and contributing to reduced healthcare spending.

The VWR, by utilizing unfilled or no-show slots for urgent same-day telehealth visits, has successfully improved healthcare accessibility for our patient population. PCP’s schedules are now consistently filled to capacity, reducing patient wait times for acute concerns, with most issues being addressed within a 24-h timeframe. This not only enhances patient satisfaction but also aligns with the Quadruple Aim’s focus on improving access to care.

As insurance payers increasingly emphasize value-based care, linking reimbursement to patient and quality outcomes, the success of the VWR in our health center underscores its potential reproducibility in outpatient offices utilizing telehealth visits. This adaptable model promises to enhance timely access for patients across various domains, serving as a scalable solution to improve healthcare delivery and scheduling efficiency. The VWR stands as a testament to our commitment to advancing healthcare delivery, ensuring its equitable distribution, and achieving positive outcomes across all four dimensions of the Quadruple Aim.

Acknowledgements

We extend our gratitude to the triage nurses at High Street Health Center for their unwavering dedication and tireless efforts in refining and improving the processes for the VWR project. Their open communication and willingness to embrace change have been invaluable in shaping the success of this project. We also wish to acknowledge the other clinicians who were actively involved in the initial roll-out of the VWR but have since left the health center. This is an acknowledgment of their collective achievements toward this project.

Data Availability

Data that support the findings of this article are available upon request from the corresponding author, MR.

Declarations:

Disclosure

Dr. Pirraglia is an editor of the journal entitled Journal of General Internal Medicine and has recused himself/herself from all decisions regarding this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6): 573-6. 10.1370/afm.1713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turkcan, A, Nuti, L, DeLaurentis PC, et al. No show modeling for adult ambulatory clinics. In: Denton B, ed. Handbook of Healthcare Operations Management: Methods and Applications. New York, NY: Spring; 2013:251-288. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhagania MK, Figueroa R, et al. Same day access: a viable alternate for outpatient clinical care. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2023;000:1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gier J. Missed appointments cost the US healthcare system $150 B each year. Available at: https://www.hcinnovationgroup.com/clinical-it/article/13008175/missed-appointments-cost-the-us-healthcare-system-150b-each-year. Accessed December 15, 2023.

- 5.Dumontier C, Rindfleisch K, Pruszynski J, et al. A multi-method intervention to reduce no-shows in an urban residency clinic. Fam Med 2013;45(9): 634-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adepoju O, Chae M, Angelocci T, et al. Transition to telemedicine and its impact on missed appointments in community-based clinics. Ann Med. 2022;54(1):98-107. 10.1080/07853890.2021.2019826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frehn JL, Starn BE, et al. Care Redesign to support telemedicine implementation during the COVID-19 pandemic: Federally Qualified Health Center personnel experiences. J Am Board Fam Med. 2023;36(5):712-722 10.3122/jabfm.2022.220370R2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reed M, Huang J, Somers M, et al. Telemedicine versus in-person Primary Care: treatment and follow-up visits. Ann Internal Med. 2023;176(10):1349-1357. 10.7326/M23-1335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gajarawala SN, Pelkowski JN. Telehealth benefits and barriers. J Nurse Pract. 2021;17/(2): 218–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Laub N, Agarwal AK, Shi C, Sjamsu A, Chaiyachati K. Delivering urgent Care using telemedicine: insights from experienced clinicians at academic medical centers. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(4): 707-713. 10.1007/s11606-020-06395-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data that support the findings of this article are available upon request from the corresponding author, MR.