Abstract

This study investigates the effectiveness of ultrasonic (US) treatment in removing and mineralizing surfactants in wastewater. It examines the complex mechanisms and variables (acoustic conditions, solution temperature, initial dose, etc.) that affect sonolytic processes. The effect of water matrix components (such as salts and the presence of secondary pollutants) on process performance is thoroughly investigated. Various treatments are analyzed through a detailed comparison of synergistic hybridization processes. The study also provides a comprehensive review of current environmental applications and explores potential directions for surfactant degradation using ultrasound. Insightful information is presented to advance sustainable wastewater treatment techniques. The literature review clearly reveals the promising future of sonotreatment for degrading various surfactants under different conditions. The use of multifrequency mechanisms and the integration of other advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) with the US process have significantly enhanced the energy efficiency of the sonochemical system. Additionally, the results highlight the need to focus on developing new sonoreactor designs, identifying degradation intermediates, and hybridizing the sonochemical system under innovative operating conditions.

Keywords: Ultrasound, Surfactants, Destruction, Gas-water interface, Pyrolysis, Radical attack

1. Introduction

Surfactants are a broad class of chemicals commonly used in detergents and other cleaning solutions. After use, residual surfactants enter surface waterways or wastewater systems where they gradually spread to various environmental compartments, including soil, water, or sediment [1], resulting in the accumulation of potentially hazardous or toxic materials [2]. Untreated wastewater can contain surfactants at concentrations of some classes between 0.4 and 40 mg/L, which can be harmful to aquatic life [3], [4]. Synthetic organic chemicals, sometimes referred to as xenobiotics, make up the majority of surfactants used in commercial applications [5]. While not all forms of surfactants are resistant to biodegradation, the lack of enzyme systems in microorganisms limits the amount of surfactant that can be biodegraded [5]. The shape of surfactant molecules, the types of functional groups they contain, the length of hydrophobic and hydrophilic chains, branching topologies, and the diversity of bacteria with unique metabolic characteristics all affect the biodegradability of a surfactant class [5]. The majority of surfactants can be treated in wastewater treatment plants through secondary treatment, which significantly reduces their concentration [4]. However, the discharge of untreated or primary treated wastewater poses significant ecological risks as it can release large amounts of surfactants into the environment [2]. Completing the main treatment chain with alternative surfactant mineralization techniques is critical to solving this problem.

A powerful class of secondary treatment techniques called Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs) is designed to deal with refractory and persistent contaminants in wastewater, such as complex organic molecules like surfactants [5]. Extremely reactive and non-selective radicals (SO4●– or ●OH) have strong oxidative capabilities, i.e., E0 = 2.8 V vs. SHE for SO4●– and 2.6 V vs. SHE for ●OH, which are the basis for AOPs [6]. Many organic contaminants can be effectively degraded by these radicals, resulting in their mineralization into simpler, less hazardous by-products [7]. There are several AOPs and they are all identified by the way they produce hydroxyl radicals. The Fenton process, which produces hydroxyl radicals when iron ions (Fe2+) combine with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in an acidic environment, is a common AOP [7]. Another AOP is photocatalysis, which uses semiconductor photocatalysts such as TiO2; in this process, sunlight or UV radiation activates the catalyst to produce hydroxyl radicals [7]. Ozonation, especially at basic pH, is useful in breaking down many types of pollutants by generating reactive oxygen species and hydroxyl radicals [7]. The initiation, propagation, and termination phases are all involved in the complex process by which these AOPs function. Because they are extremely reactive, hydroxyl radicals attack organic contaminants and generate intermediates that then undergo further reactions to complete mineralization. To ensure a more thorough and long-lasting approach to water purification, AOPs are essential in improving the treatment effectiveness of traditional wastewater treatment methods, especially for resistant chemicals such as surfactants.

A subset of AOPs that is particularly important for wastewater treatment is the sonochemical process, which breaks down complex contaminants such as surfactants [8]. Using ultrasonic waves (mechanical perturbations between 20 to 1000 kHz) to induce acoustic cavitation in liquids, through a series of compression and rarefaction cycles, sonochemistry creates short-lived harsh conditions in the microenvironment of collapsing bubbles as well as highly reactive species such as hydroxyl radicals [9]. The high temperatures (∼1000 to 5000 K) and pressures (∼100 to 5000 bar) experienced during bubble collapse (with ∼2000 K at the bubble-solution interface) promote a multitude of sonochemical reactions [10], [11], including the scission of molecular bonds, free radical generation, and the formation of reactive intermediates [12]. These highly reactive species can subsequently engage in various chemical transformations, leading to the degradation of pollutants, initiation of polymerization reactions, and the synthesis of novel nanomaterials. The specific effects of acoustic cavitation are highly dependent on the targeted molecules and the overall reaction environment. Additionally, this cavitation results in the formation of intense acoustic streaming (liquid circulation), high shear stress near the bubble wall, the creation of microjets near solid surfaces due to the asymmetrical collapse of bubbles, and turbulence. All these phenomena enhance the transport properties of the species involved [13].

Sonochemistry has distinct advantages over alternative AOPs. In sonochemistry, the ultrasonic cavitation process takes place throughout the liquid phase, facilitating effective interaction between contaminants and reactive species. This makes sonochemistry very useful for breaking down surfactants, which are often difficult to break down using traditional techniques. Radical formation in sonochemical processes is a flexible process involving a range of reactive species, including superoxide radicals, hydrogen and oxygen atoms, hydroxyl radicals and hydrogen peroxide, all of which contribute to a powerful and diverse degradation mechanism.

Numerous surfactants have been effectively degraded and mineralized by ultrasound in a variety of environmental matrices such as wastewater, soil, and water [8]. Because it can be applied to both homogeneous and heterogeneous systems [14], [15], it is versatile and suitable for a variety of situations. In addition, ultrasound-based processes are thought to be ecologically beneficial because they typically operate under moderate conditions and don't require the addition of chemicals.

The purpose of this work is to present a thorough analysis of the latest developments, confronted challenges, and proposed solutions for the degradation of surfactants by ultrasound. Following a preliminary discussion of surfactants and their environmental implications, this paper delves into the fundamental principles governing sonochemistry within aqueous surfactant systems. This study presents a comprehensive examination of the intricate factors governing the sonochemical degradation of surfactants. Subsequently, the investigation explores the impact of diverse water matrix components on the sonochemical degradation of surfactants. In addition, synergistic strategies, such as hybrid sonochemical systems, are reviewed and their potential to increase removal efficiency is highlighted. The paper concludes with a discussion of current challenges, outlining potential lines for future research, and a holistic overview of sonochemistry's potential in addressing surfactant contamination.

2. Chemistry and types of surfactants

Surfactants function by reducing surface tension and forming micelles in solvents and are known for their surface-active properties [2]. They are often found where water and oil (or lipids) meet and act as emulsifying or foaming agents [4]. Their chemical structure, consisting of an asymmetric backbone with a hydrophobic tail and a hydrophilic head group, is intrinsically linked to this functionality [4]. The hydrophobic portion is usually a linear or branched alkyl chain attached to the hydrophilic group. The most common solvent for surfactant molecules, water, can interact with them differently due to their dual activity. While the hydrophobic moieties are expelled from the inner phase and accumulate on surfaces, the hydrophilic group shows high solubility in water.

Monomers of surfactant molecules are present at low aqueous concentrations. At higher concentrations, surfactant molecules form micelles, which reduces the free energy of the system [4]. The critical micelle concentration (CMC) is the term used to describe the concentration threshold for surfactant aggregation [16]. In contrast to anionic and cationic surfactants, non-ionic surfactants have lower CMC values [4]. In order for surfactants to confer detergent and solubilizing properties, they must naturally form micelles. At concentrations above the CMC, surfactants can dissolve more hydrophobic organic molecules than water alone.

A list of commonly used surfactants is given in Table 1 and the chemical structures of each are shown in Fig. 1. Based on the charge of their head group, surfactants are classified as anionic, cationic, amphoteric or nonionic [4]. The physicochemical properties and uses of each class of surfactant are reflected in this classification. This is a summary of the information found in [4].

Table 1.

Classifications and abbreviations for common surfactant categories [4].

| Common name | Abbreviation | Class |

|---|---|---|

| Linear alkylbenzene sulphonic acid | LAS | Anionic

|

| Sodium dodecyl sulphate | SDS | |

| Alkyl sulphate | AS | |

| Sodium lauryl sulphate | SLS | |

| Alkyl ethoxysulphate | AES | |

| Quaternary ammonium compound | QAC | Cationic

|

| Benzalkonium chloride | BAC | |

| Cetylpyridinium bromide | CPB | |

| Cetylpyridinium chloride | CPC | |

| Hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide | HDTMA | |

| Amine oxide | AO | Amphoteric

|

| Alkylphenol ethoxylate | APE | Nonionic

|

| Alcohol ethoxylate | AE | |

| Fatty acid ethoxylate | FAE |

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of various common surfactants (refer to Table 1 for abbreviations) [4].

2.1. Anionic surfactants

The most common and oldest type of surfactant, anionic surfactants are essential for detergents and soaps. With hydrophilic carboxyl, sulfate, sulfonate or phosphate groups and hydrophobic alkyl chains, they are used in biotechnology, cosmetics and pharmaceuticals, among others. They enhance the efficacy of drugs in pharmaceutical formulations either by direct binding or by improving adsorption and absorption. Anionic surfactants also show promise in soil remediation; in pollution tests, they were particularly effective in removing diesel oil from a variety of soil types.

2.2. Cationic surfactants

In particular, quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs) are cationic surfactants because they contain hydrophobic hydrocarbon chains attached to a positively charged nitrogen atom. These chains often have additional alkyl groups as substituents. Long-chain QACs are commonly found in fabric softeners, hair conditioners and laundry detergents. They are antibacterial and act as disinfectants against a variety of pathogens. QACs are used topically in products such as mouthwashes and oral antiseptics, although they are often toxic to mammalian cells and inappropriate for systemic administration. Some cationic surfactants have been developed to reduce the harmful effects on human cells and the environment, such as soft counterparts of long-chain QACs. These gentle antimicrobial compounds have adequate antimicrobial capabilities, strong chemical stability, and readily degrade in vivo and in the environment without causing harm.

2.3. Zwitterionic surfactants

Amphoteric surfactants exhibit zwitterionic behavior at intermediate pH and undergo a charge change from net cationic to anionic at low and high pH, respectively. Amine oxides (AOs) are well-studied amphoteric surfactants that are generally produced by exothermic reactions between tertiary amines and H2O2. AOs are used in many different industries. They are used as antibacterial agents, foam stabilizers and polymerization catalysts in the rubber industry, textile antistatic agents and foam boosters in dishwashing detergents. In dishwashing applications, AOs offer a superior weight/performance ratio despite their higher manufacturing cost. Due to their zwitterionic nature, which allows them to be compatible with anionic surfactants and provide synergistic effects in formulations, AOs are skin-compatible and are often used in combination with other surfactants. They also exhibit low to moderate toxicity, ease of removal through wastewater treatment, non-volatility and low potential for bioaccumulation in terrestrial organisms.

2.4. Nonionic surfactants

The balance between the hydrophilic and hydrophobic components of nonionic surfactants, usually consisting of an ethylene oxide chain of varying length as the hydrophilic component and a fatty acid, alkylated phenol derivative, or long chain linear alcohol as the hydrophobic component, allows surface activity to be achieved. These surfactants work well with both cationic and anionic counterparts because they are charge-free. Nonionic surfactants are widely used as wetting agents, emulsifiers and foam stabilizers in biotechnological processes, insecticide formulations and to improve the stability of drug carriers. Their involvement in pesticide formulations is influenced by their interaction with pesticides, which affects surfactant efficacy. Nonionic surfactants are widely used, but studies have shown them to be hazardous to a number of plant species, including tobacco, sugar beet and spiderwort.

3. Surfactants environmental impact and ecotoxicity

Due to the widespread use of surfactants in everyday life and their high prevalence in wastewater, surface water, soil, sediment and sludge treatment, concerns about their ecotoxicity have increased. Although wastewater treatment plants degrade a large number of surfactants, certain surfactants can still have an impact on ecosystems. Because they suppress microorganisms in sludge, accumulated surfactants, especially cationic surfactants such as QACs, pose a threat to the effectiveness of wastewater treatment plants. To protect the environment, the amount of surfactants released, especially the cationic, anionic and nonionic varieties, is monitored and regulated. Surfactant concentrations in aquatic systems often remain below levels that are effective toxins to aquatic life; cationic surfactants are known to be the most dangerous. Certain surfactants are known to be toxic to certain species, particularly aquatic species [4]. Test organisms such as fish, algae and bacteria are often used to assess the toxicity of surfactants [4]. Table 2 illustrates some examples of how surfactants impact human health, the microbial world, soil, plants, and aquatic animals.

Table 2.

Effects of surfactants on human health, microbial world, soil, plants and aquatic animals [115].

| Effect of surfactants on human health (The allowable intake of surfactants for humans is approximately 5 mg per person from sources such as drinking water, detergents, and food.) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Surfactant | Acute effects | Chronic effects |

| Sodium dodecyl sulphate | Erythema, redness, Irritation to mouth, skin and lungs [116] | DNA damage, Membrane damage to lymphocytes [116] |

| Sodium dodecyl benzene sulphonate | Skin and eye irritation, possible eye damage, nose and throat irritation [117] | Spastic paralysis, damage to Gastrointestinal track leads to Hypermotility, diarrhoea [117] |

| Perfluorooctane sulphonic acid | Skin and respiratory irritation [118] | cancer, stunted growth, influenza, preeclampsia, thyroid hormone, cholesterol; attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), reduced fetal growth and birth size of animals and humans [119]. |

| Perfluorobutane sulphonate | Alters Red blood cell counts, hemoglobin, lowers albumin. | thyroid hormonal disturbances, reproductive toxicity, effects on liver, kidney, hormonal and disturbances [120]. |

| Potassium oleate | Vomiting, fast renal excretion, skin inflammation, redness, dermatitis [121] | weak pulse, irregularities in heart rhythm, heart block and eventual fall in blood pressure, diarrhea, bloated stomach, corneal clouding and swelling, difficulty in breathing, lung damage [121] |

| Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) | Nausea, Vomiting, skin irritation [122] | chemical burns throughout the esophagus and gastrointestinal tract followed by nausea and vomiting, can lead to death [122] |

| Benzethonium chloride | Vomiting, irritation to the skin, eyes, mucous membranes and upper respiratory tract [123] | Collapse, convulsions and coma, injury to the mucous membrane, nausea, esophageal damage and necrosis, hypotension, dyspnea, cyanosis, paralysis of respiratory muscles and death [123] |

| Effect of surfactants on microbial world | ||

| ||

| Effect of surfactant on Soil and Plants | ||

| ||

| Effect of surfactants on aquatic animals (The permissible levels of surfactants have been reported to be 0.1 mg/L) | ||

| ||

In addition, the environmental persistence of several surfactants underscores the need for more sophisticated treatment methods, including advanced oxidation technologies. The use of advanced oxidation techniques is essential to ensure complete and efficient removal of these persistent chemicals, as they can resist traditional degradation processes. Further research and development in this area is essential to solve the problems caused by persistent surfactants and to improve the sustainability of wastewater treatment methods. The potential environmental and human health impacts of these compounds highlight the need for close monitoring and creative problem solving to protect ecosystems and public health.

4. Sonochemical insights in the presence of surfactants

When aqueous solutions are exposed to ultrasound at frequencies between 20 kHz and 1 MHz, acoustic cavitation is a critical factor in the chemical changes observed. The cycles of sound reflection and compression that pass through the solution cause cavitation, which causes pre-existing bubbles to develop and abruptly collapse [17]. These cavitation bubbles undergo a quasi-adiabatic transient collapse that raises the temperature of the vapor phase within the cavity to 4000–5000 K. The pressure also rises to about 1000 bar [18], [19], and the liquid shell of the bubble reaches a temperature of 500–2000 K [20], [21]. The pyrolytic decomposition of solutes that have separated into the vapor phase or the bubble/water interface is caused by this brief and localized temperature rise. In addition, homolytic cleavage of the water vapor in the collapsing cavity produces H atoms, O atoms, and ●OH radicals [22]. These radicals contribute to the degradation of organic matter not only inside the bubble, but also at the bubble–liquid interface and, to a lesser extent, in the bulk aqueous solution, suggesting different sonochemical scenarios [6], [9].

The gas/liquid interface of the cavitation bubble is where surfactants preferentially adsorb due to their hydrophilic ionic headgroup and hydrophobic tail. The charge and character of the head group in surfactants influence cavitation bubble properties, particularly their growth and surface stability [23], [24]. As a result, the bubble population parameters (i.e., the number and size distribution of bubbles) and the distribution of acoustic pressure are expected to be influenced by the presence of various concentrations and types of surfactants in the sonicated solution. Pyrolytic processes at the bubble/solution interface have been shown to result in the sonochemical degradation of perfluorinated compounds (PFCs), including perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) [25]. The degradation of sodium dodecylbenzene sulfonate was observed to occur by free radical attack in the same reaction zone [26]. Consequently, the fraction of total surfactant molecules adsorbed at the interface of momentarily cavitating bubbles coincides with the sonolytic degradation rate [27]. However, due to the short bubble lifetime (<100 µs) and the high oscillation velocity of the bubble radius (>5 m/s), quantification of this fraction is difficult [27]. The adsorption of surfactants on acoustic cavitation bubbles has been the subject of several studies [8], [25], [28], [29], [30], [31]. Studies have demonstrated that surfactants accelerate bubble growth in aqueous solutions through the rectified diffusion mechanism [23], [24], [32]. A potential mechanism for this enhanced growth is the intensification of microstreaming, which creates a circulatory flow near the bubble, facilitating the transport of fresh solution with a higher gas concentration to the bubble's interface. This, in turn, strengthens the driving force for mass transfer. According to Leong et al [33] the presence of surfactants of any form (DTAC, SDS, DDAPS) in the solution increased microstreaming velocities near the bubble. Notably, surfactants with bulkier headgroups exhibited the most significant enhancement in these velocities. The enhancement in surface oscillations and microstreaming was most pronounced for DTAC, reflecting the bulkiness and charge of its headgroup. Additionally, increased resistance to mass transfer can contribute to the ameliorated rectification of gas into the bubble. Surfactants with long chains provide greater mass transfer resistance, thereby contributing to higher growth rates. This resistance to mass transport arises from the decreased mass transfer during contraction, caused by a reduction in bubble surface area and an increase in surface surfactant concentration, which hinders outward diffusion. Conversely, during expansion, there is less resistance to mass transfer due to the increase in surface area and the reduction in surface surfactant concentration [23]. A direct correlation between surfactant concentration and mass transfer resistance has been established. For instance, a tenfold increase in DTAC concentration, from 1 mM to 10 mM, demonstrably elevates resistance [33]. According to numerical simulations by Fyrillas and Szeri [34], radial oscillations limit the maximum interfacial surfactant concentration, while high-speed bubble oscillations push additional surfactant molecules onto weakly populated surfaces. According to the findings of Sostaric and Reisz [28], radical scavenging efficiency increases with decreasing n-alkyl chain length at high (>1 mM) surfactant concentrations. Their results also showed that the Gibbs surface area excess under ultrasonic irradiation was less than the equilibrium surface area excess. Reduced bubble coalescence and clustering was observed in the acoustic emission spectra experiments of Greiser and Ashokkumar with increasing SDS concentrations (0.5–2 mM). This was attributed to the accumulation of anionic surfactants and the resulting negative charge at the bubble-water interface [35]. At a frequency of 515 kHz, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), a surface-active solute, demonstrably reduced bubble coalescence by approximately 20 % through electrostatic repulsion [36]. In another study, Ashokkumar et al [37] indicated that the increase of SDS and DTAC concentrations up to 1 mM resulted in a significant enhancement of the maximum signal compared to pure water. However, at higher concentrations, the signal intensity decreased again, approaching a limiting value similar to that observed in pure water. This occurs because, beyond this concentration, the addition of the ionic surfactant (a strong electrolyte) reduces the repulsion between the bubbles, thereby increasing bubble clustering once more. When concentration-dependent kinetics for perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) were modeled using Langmuir-Hinshelwood kinetics, it was found that high-speed radial oscillations caused increased partitioning of PFOS and PFOA at the bubble-water interface at low concentrations (<10 µM) [27]. This result is consistent with the findings of Cheng et al. [38] who showed that sonochemical rates for dilute PFOS and PFOA (<1 µM) were unaffected by the addition of very large amounts (>10 mM) of semi-volatile organics. The adsorption of charged surfactants at the air–water interface imparts a net negative or positive charge to the bubbles, mirroring the charge of the surfactant headgroup [39]. This interfacial phenomenon leads to electrostatic repulsion between neighboring bubbles. The addition of electrolytes (salt), however, mitigates this repulsion by screening the electrical field surrounding each bubble, Fig. 2. As a result, bubble clustering may be restored to the level observed in pure water. According to Ashokkumar et al [37], the addition of 0.1 M NaCl to solutions containing three different surfactants (SDS, DTAC, and DAPS) resulted in emission signal intensities that were identical to those observed in pure water. On the other hand, DAPS (a zwitterionic surfactant) solutions exhibit negligible long-range electrostatic interaction between bubbles. Consequently, bubble clustering remains largely unchanged compared to pure water, leading to a similar emission intensity as observed in the pure water case.

Fig. 2.

The schematic diagram depicts a collection of bubbles with adsorbed ionic surfactant molecules. These adsorbed molecules are accompanied by diffuse countercharge regions. Electrostatic repulsion between these charged surfaces keeps the bubbles separated. The lower portion of the diagram illustrates bubble clustering. Here, the van der Waals attraction between bubbles surpasses the weakened electrostatic repulsion caused by the presence of added salt. Within these clusters, the inner bubbles are shielded from the full force of the acoustic pressure by the outer bubbles [37].

5. Ultrasonic removal of surfactants

The particular operating conditions used have a significant impact on how well sonochemical treatment of surfactants works. A summary of the parameters examined in each surfactant research study is given in Table 3, which provides an overview of surfactant research studies. In the following sections, each study is thoroughly analyzed and discussed, highlighting the circumstances and notable results.

Table 3.

Key studies on the sonochemical degradation of surfactants.

| Entry | Surfactant | Sonication conditions | Treatment’s effectiveness | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Triton X 100 | 358 kHz, 0.33 W/cm2, variable concentration (C0) | Higher removal degrees were recorded for concentration lower than the surfactant’s CMC (250 µM). | Destaillats et al. [40] |

| 2 | Teric GN9 (polydisperse nonylphenol ethoxylate surfactant) | 363 kHz, 2 W/cm2, argon saturation, C0 = 0.01–0.11 mM | A remarkable TOC removal of nearly 90 % was attained after 24 h of sonication, underscoring the high mineralization process | Vinodgopal et al. [47] |

| 3 | sodium dodecylbenzenesulfonate (DBS) et sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS) | 200 kHz, 6 W/cm2, argon/air atmospheres, C0 = 10 µM | More than 80 % removed within 1 h. | Yim et al. [29] |

| 4 | Sodium Dodecylbenzene Sulfonate (SDBS) | 362 kHz, 2.5 W/cm2, C0 = 50–450 µM. | Significant degradation takes place, particularly when C0 is below the CMC of SDBS (∼150 µM). | Ashokkumar et al. [26] |

| 5 | Perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) | 200 kHz, 3 W/cm2, air and argon saturation, C0 = 10 and 100 mg/L | Effective removals were achieved, especially under an argon-sonicated medium | Moriwaki et al. [43] |

| 6 | 4-octylbenzene sulfonate (OBS), dodecylbenzenesulfonate(DBS) and 4-ethylbenzene sulfonic acid (EBS) | 354 kHz, 1.41 W/cm2, argon saturation, C0 = 0.1–5 mM | EBS and OBS exhibited faster degradation in the single-component system compared to their mixture counterpart. |

Yang et al. [45] |

| 7 | perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) | 354 kHz (250 W/L), 500 kHz (150 W/L) and 618 kHz (250 W/L), argon saturation, C0 = 10 µM | Efficient removal, followed by immediate mineralization of the surfactants. | Vecitis et al. [25] |

| 8 | Perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) are | 358 kHz, 250 W/L, argon saturation, 10 °C, C0 = 20 nM-200 µM | Both PFOA and PFOS efficiently degraded by ultrasound, especially for lower concentration | Vecitis et al. [27] |

| 9 | Octylbenzene Sulfonic Acid (OBSA) | 206, 354, 620, 803, and 1062 kHz using pulse and continuous wave irradiation (CW, PW). | Sonication effectively degraded OBSA in either continuous or pulse irradiation | Yang et al. [55] |

| 10 | p-octylbenzene sulfonate (LAS C8), p-nonylbenzene sulfonate (LAS C9), and p-dodecylbenzene sulfonate (LAS C12) | 200 kHz, 200 W, C0 = 15 to 2000 µM | Effective degradation of all LACs, especially at lower concentration level in the solution. | Nanzai et al. [54] |

| 11 | perfluorobutanoate (PFBA), perfluoro-butanesulfonate (PFBS), perfluoro-hexanoate (PFHA) and perfluorohexanesulfonate (PFHS) | 202–1060 kHz (250 W/L), C0:0.30 µM for PFBS, 0.47 µM for PFBA, 0.23 µM for PFHS and 0.32 µM for PFHA, argon saturation. | Effective degradation was observed, and it decreased with an increase in the carbon number in the hydrophobic chain of the surfactants. | Campbell et al. [57] |

| 12 | Octaethylene glycol monododecyl ether (C12E8) | 355 kHz, 18 W, C0 = 40 to 120 µM, 20 °C. | Effective degradation was observed, especially for concentration below CMC. | Singla et al. [45] |

| 13 | laurylpyridinium chloride (LPC) | 355 kHz, 18 W (acoustic), C0 = 0.1 to 0.6 mM, 20 ± 5 °C | Effective treatment of LPC solution was achieved; however, a low removal of TOC was observed after an extended irradiation period of 20 h. | Singla et al. [128] |

| 14 | Octylbenzene sulfonate (OBS) | 616 and 205 kHz (pulse and continues wave modes, PW,CW), 27 W acoustic, 20 °C; [OBS]0 = 1 mM. | OBS degraded efficiently under ultrasound. Continuous wave (CW) sonolysis showed improved degradation performance compared to the continuous wave mode. | Deojay et al. [56] |

| 15 | Perfluorobutyric acid (PFBA), Perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHA), perfluorooctanoate (PFOA), Potassium perfluorobutane-1-sulfonate (PFBS), potassium perfluorohexane-1-sulfonate (PFHS), and Potassium perfluoro- octane-1-sulfonate (PFOS) | 202, 358 and 610 kHz for power densities of 83, 167, 250 and 333 W/L (argon atmosphere, C0: 300 nM for PFBS, 470 nM for PFBA, 230 nM for PFHS, 320 nM for PFHA, 200 nM for PFOS and PFOA) | Effective surfactant degradation occurs, with an optimum frequency of 358 kHz and applied power destiny of 333 W/L | Campbell and Hoffmann [58] |

| 16 | Perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) | 44, 400, 500 and 1000 kHz for 40 W power, C0 = 10 mg/L, pHi 5.66, air atmosphere | At elevated frequencies, over 90 % of PFOS was eliminated, whereas no degradation was evident at 44 kHz. | Wood et al. [66] |

| 17 | 13 per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) | 575 kHz and power density = 144 W/L, (temp.11 °C, pH 5.65) | Almost all compounds in the PFAS mixture experienced over 95 % degradation within 8 h. | Shende et al. [68] |

At 358 kHz and 0.33 W/cm2, aqueous solutions of Triton X-100 were treated [40]. After 1 h, concentrations below the surfactant CMC (250 µM) were found to have superior removal efficiencies; removal percentages for concentrations of 31 and 112 µM were 74 % and 39 %, respectively. On the other hand, removal rates were found to be lower at concentrations above the CMC, with 570 µM resulting in a removal rate of 5 %. The observed low degradation above the critical micelle concentration (CMC) suggests that micelle formation diminishes apparent sonochemical efficiency. This phenomenon likely arises from the isolation of free surfactant monomers from the water–gas interface of cavitation bubbles. Consequently, micelles can be conceptualized as effective 'shelters', isolating solutes from the direct effects of sonochemistry. The rate constants (21.5 × 10−3 min−1 and 8.2 × 10−3 min−1) obtained for concentrations (31 µM and 112 µM, respectively) below the CMC (250 µM) were found to be comparable to those obtained using the photocatalytic approach [41], [42]. According to HPLC-ES-MS studies, the preferred active site was the hydrophobic alkyl chain. The main reaction documented was the pyrolytic cleavage of the alkyl chain during bubble collapse, combined with ●OH radicals produced during the same event. Other reactions noted included the addition of ●OH radicals to the aromatic ring and the attack of ●OH radicals on the polyethoxylated chain, resulting in either an oxidized product or a shorter polyethoxylated chain. Similarly, Yim et al. [29] used ultrasound at a frequency of 200 kHz and 6 W/cm2 to study the degradation of sodium dodecylbenzene sulfonate (DBS) and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in an argon environment. The objective was to compare the formation of cavitation bubbles at the gas/liquid interface and the scavenging efficiency of the hydroxyl radical. After 1 h of ultrasonication, 80 % of the surfactants had been removed, with both surfactants degrading at a similar rate of 3.8 µM/min. After 10 min of ultrasonication, hydrogen peroxide yield was measured and the relationship between surfactant concentration and change in yield was determined. Hydrogen peroxide yield decreased rapidly with increasing BDS and SDS concentrations, reaching 0 mM at 1 mM of each surfactant, indicating substantial hydroxyl radical scavenging efficiency by the surfactants. CO and CH4 were detected as gaseous products. The authors claim that both pyrolysis at the bubble-solution interface and interaction with the hydroxyl radical caused the degradation of the surfactants. On the other side, Moriwaki et al. [43] investigated the use of sonochemical action (200 kHz, 3 W/cm2, air and argon saturation) to degrade perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) in aqueous solutions. The t1/2 of PFOS and PFOA degradation at an initial concentration of 10 mg/L was 43 and 22 min under argon and 102 and 45 min under air, respectively. Under air irradiation, the degradation rate constants for PFOS and PFOA increased to 0.0068 and 0.0155 min−1, respectively, while under argon they go up to 0.016 and 0.032 min−1, respectively. Thus, saturating the sonicated solution with argon (polytropic index: Ar: 1.67 compared to air: 1.41) increases the degradation rate of PFOS to approximately twice that observed with air. PFOA was found to be the major by-product of PFOS degradation. When tert-butyl alcohol (10 mM), a known ●OH scavenger, was added to the PFOS sonolysis, the degradation of PFOS was only slightly suppressed (about 12 % after 60 min of sonolysis), indicating that thermal decomposition is the main factor driving PFOS degradation. PFOA was still formed in the presence of tert-butyl alcohol and at a comparable yield. PFOS and PFOA (0.02 mM) did not degrade when Fenton reagents (0.2 mM Fe2+/H2O2, 1:1 M ratio) were tested independently. Since PFOS and PFOA are non-volatile, reaction within cavitation bubbles was not considered. As a result, PFOS and PFOA undergo pyrolysis at the interface between the cavitation bubbles and the bulk solution. Similarly, Using frequencies of 354 kHz (250 W/L), 500 kHz (150 W/L), and 618 kHz (250 W/L), Vecitis et al. [25] investigated the kinetics and mechanism of ultrasonic transformation of perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS). Using 618 kHz and 250 W/L under argon saturation, it took 180 min to completely remove 10 µM PFOS and only 120 min to completely remove PFOA. Mass balances for carbon, sulfur, and fluorine show that mineralization occurs immediately after surfactant degradation. Pyrolytic reactions occur at the bubble interface and in the gas phase of the bubble, resulting in nearly 100 % conversion of PFOA and PFOS to F–, SO42–, CO and CO2. At the bubble/solution interface, PFOA or PFOS undergoes initial pyrolytic degradation resulting in removal of the ionic functional group and formation of the corresponding 1H-fluoroalkane or perfluoroolefin. In the bubble vapor, fluorochemical intermediates undergo a series of pyrolytic processes to produce C1 fluororadicals. Concurrent hydrolysis and secondary reactions in the vapor phase convert the C1 fluororadicals to CO, CO2, and HF, which upon dissolution produce a proton (pH increase) and fluoride. In another study, Vecitis et al. [27] focused on the effect of initial PFOS and PFOA concentrations on the degradation performance of these substances. Sonolysis was performed over a wide range of initial concentrations (20 nM to 200 µM) at 358 kHz and 250 W/L under argon saturation, and decreasing removal yields were observed for higher initial concentrations above 15 µM (e.g., 85 % for 30 µM). Complete removal of low concentrations (<15 µM) was achieved after 180 min for both surfactants. An initial, rate-limiting ionic headgroup cleavage occurs at the bubble-water interface during sonochemical degradation of PFOS. As the bubble interface sites become saturated, PFOS sonochemical kinetics change from pseudo-first order at low initial concentrations (<20 µM) to zero-order kinetics at high initial concentrations (>40 µM). Langmuir-Hinshelwood kinetics were used to quantify concentration-dependent rates below 100 µM. These results showed that sonochemical degradation rates for PFOS increase when the bubble interface is undersaturated. Similar results of PFOS removal as a function of initial concentration during 1 MHz ultrasonication in the range of 10–460 µM [PFOS]0 were published by Rodriguez-Freire et al. [44]. According to their research, PFOS degradation exhibited saturation kinetics, i.e., as the PFOS content increased, the degradation rate also increased, eventually reaching a maximum. Beyond that point, the rate of degradation as a function of concentration stopped. The sound frequency affected the saturation conditions; lower concentrations reached saturation below 1 MHz (100 µM), while the 500 kHz frequency (>460 µM) did not. Within 300 min, almost 50 % of the TOC in the 1 MHz frequency band was mineralized, and F– and SO42– (2.0 and 0.07 mM at 300 min, respectively) were immediately released [44]. In addition, Rodriguez-Freire et al. [44] observed that the PFOS degradation rate was greater at mega-sonic frequency (1 MHz) compared to ultrasonic frequencies (25–500 kHz). The degradation of octaethylene glycol monododecyl ether (C12E8), a nonionic surfactant, was studied by Singla et al. [45] at different initial concentrations (40–120 µM), both above and below its CMC of about 90 µM. Up to the CMC, the degradation rate was found to increase with increasing initial surfactant concentration. Beyond the CMC, a relatively constant degradation rate was observed. At the bubble/solution interface, both pyrolytic fragmentation and surfactant oxidation/hydroxylation are involved in the elimination of C12E8. Various short-chain carboxyalkyl polyethylene glycol intermediates are formed by hydroxylation of the ethylene chain, and oxidative cleavage of the ethylene oxide moiety shows evidence of ●OH radical attack. Rapid oxidation and hydroxylation of the polyethylene glycol chain produce simple molecules that can be further degraded. Despite these procedures, TOC analysis shows that the relatively low reactivity of the degradation products toward the bubble/liquid interface makes it difficult to achieve sonolytic mineralization of the surfactant at reasonable rates. In Reisse [46], the ultrasonic degradation of the cationic surfactant laurylpyridinium chloride (LPC) was investigated at concentrations between 0.1 and 0.6 mM, all below the critical micelle concentration (CMC) of 15 mM. The study found that pyrolysis is mainly involved in the first stage of LPC degradation. Numerous degradation products, including water-soluble species and hydrocarbon gases, were detected after various types of investigations. Interestingly, a significant amount of LPC was converted to carboxylic acids. However, due to the hydrophilic nature of the resulting compounds, the total mineralization of these carboxylic acids by sonolysis proved to be a rather sluggish process.

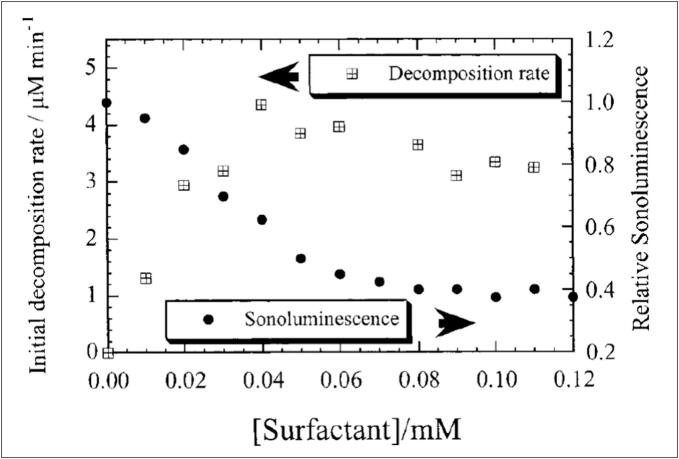

Using ultrasound at a frequency of 363 kHz and an intensity of 2 W/cm2, Vinodgopal et al. [47] conducted a comprehensive investigation of the ultrasonic-induced degradation of Teric GN9, a polydisperse nonylphenol ethoxylate surfactant. A variety of Teric GN9 starting concentrations were used in this study, ranging from 0.01 to 0.12 mM. The TOC of the solutions was tracked over a range of sonication times to evaluate the degradation process. After 24 h of sonication, the data showed a significant decrease in TOC of approximately 90 %, indicating a very successful mineralization process and the generation of volatile degradation products. Interestingly, in the first two hours, over 95 % of Teric GN9 was degraded with a small decrease in TOC of less than 10 %. This observation is consistent with the HPLC results and indicates that the main degradation stage of Teric GN9 produces water soluble by-products. The degradation process starts at the bubble/solution contact and is driven by both thermal and radical processes. Short-length intermediates are then subjected to pyrolysis (within the bubble) resulting in the identification of pyrolytic components including hydrogen, acetylene, propane, ethane and methane. In contrast to the findings of Destaillats et al. [40], the decomposition rate of Teric GN9 increases as the initial concentration rises from 10 to 40 µM, reaches a maximum, and then slightly declines [47], Fig. 3. The surfactant concentration at which the maximum decomposition rate is achieved closely corresponds to the critical micelle concentration (CMC: (5 ± 1) × 10−2 mM) of Teric GN9 (5 × 10−5 M [48]). This discrepancy may be attributed to many factors, including the concentration ranges (0.01–0.12 mM for Teric GN9 and 0.031–1.13 mM for Triton X-100), CMCs ((5 ± 1) × 10−2 mM for Teric GN9 and 0.25 mM for Triton X-100), acoustical conditions, reactivity with hydroxyl radicals, and diffusivity (toward the bubble-water interface) of both non-ionic surfactants. On the other side, the relationship between sonoluminescence intensity and surfactant concentration (Fig. 3) exhibits a distinct two-regimes, roughly separated by the critical micelle concentration. Beyond the CMC, the emission intensity remains relatively constant. This observation reflects the stable concentration of free surfactant monomers in the solution, which translates to a constant surfactant concentration at the bubble-solution interface. The observed accelerated quenching of sonoluminescence for Teric GN9 dose lower than ∼CMC (Fig. 3) is likely attributable to its fragmentation at the bubble surface. The volatile hydrophobic decomposition products are expected to accumulate within the bubble over numerous expansion-compression cycles. This progressive accumulation leads to the decrease of the heat capacity ratio (γ) and potentially increase the internal bubble pressure (Pg) at implosion. Consequently, a decline in bubble core temperature (Tmax) would be expected, leading to a diminished sonoluminescence intensity as shown by Eq. (1):

| (1) |

Fig. 3.

Initial decomposition rate of Teric GN9 as a function of initial surfactant concentration. Additionally, the relative sonoluminescence emission intensity of these solutions is plotted on the right Y-axis [47].

Where T0 is the ambient temperature, and Pa is the pressure exerted on the bubble at the moment of implosion. A study by Ashokkumar et al. [26] used sonochemical treatment at a frequency of 362 kHz and an acoustic power of 2.5 W/cm2 to degrade sodium dodecylbenzene sulfonate (SDBS, CCM ∼ 150 µM). In their tests, they sonicated a 50 µM SDBS solution, which resulted in total removal after 90 min, and initial concentrations of 100 and 150 µM, which resulted in removal rates of 75 % and 73 %, respectively. It is noteworthy that the rate of SDBS (ionic surfactant) removal increased linearly below the CMC, but then slowed. These findings are in accordance with those obtained by Vinodgopal et al. [41] for the degradation of Teric GN9 (nonionic surfactant), Fig. 3. As discussed previously, this slowdown in surfactant degradation is mainly due to the formation of micelles at concentrations above the CMC. According to the study, there is a direct relationship between the rate of SDBS degradation and the decrease in surface tension of solutions in water or air. According to the postulated degradation process, the first step is to attack SDBS molecules adsorbed at the cavitation bubble/solution interface with ●OH radicals (confirmed by the decrease in H2O2 yield). Methane, ethane, ethylene, and acetylene were among the gaseous hydrocarbon compounds produced by prolonged sonication of approximately 12 h (confirmed by headspace analysis using CPG). Both water-soluble species, such as oxalic acid, and volatile products were formed as a result of further radical attack on the intermediates formed in the first stage of degradation. These products then underwent pyrolysis in cavitation bubbles. Berlan et al.[49], in their investigation into the sonochemical degradation of phenol, observed the initial formation of hydroquinone, catechol, and benzoquinone. Continued sonication resulted in the generation of oxalic, maleic, acetic, formic, and propanoic acids, likely arising from further reactions between these initial products and primary radicals. Sonoluminescence (SL) studies were performed during the first five minutes of sonication to investigate the likelihood of pyrolysis of either SDBS or its initial degradation products [26]. A decrease in SL intensity would be expected if SDBS or its initial degradation products were volatile [30], [50], [51], [52], [53], as pyrolysis could occur and lower the peak temperature that drives SL. When SDBS (0–500 µM) was present, there was no quenching of SL, suggesting that neither SDBS nor its degradation products underwent pyrolysis within the bubbles during the initial sonication periods [26]. Nevertheless, as indicated in literature [47], [49] and in Ashokkumar et al’ results [26], further radicals attack leads to the formation of volatile organics (in addition to water-soluble organic species), such as high molecular weight alkanes from the decomposition of SDBS. These alkanes are pyrolyzed within the cavitation bubbles, resulting in the formation of methane, ethane, ethylene, and acetylene [26].

The degradation of 4-octylbenzenesulfonate (OBS), 4-ethylbenzenesulfonic acid (EBS), and dodecylbenzenesulfonate (DBS) was studied by Yang et al. [45] at 354 kHz and 1.41 W/cm2 in both single and binary mixed systems. Compared to their mixed equivalents, EBS and OBS showed faster degradation in the single-component system. In other words, in the single-component system, 32 % of the OBS and 20 % of the EBS were eliminated in 2 h, whereas in the combination, only 30 % of the OBS and a meager 5 % of the EBS were eliminated in the same amount of time. Due to its faster transport to the cavitation bubble interface, OBS showed a faster degradation rate than DBS in surfactant mixtures containing both, especially at shorter pulse intervals. On the other hand, because DBS accumulates more on the bubble surface and is more surface active than OBS, it degraded faster than OBS at longer pulse intervals. The sonochemical degradation of anionic surfactants, specifically p-octylbenzene sulfonate (LAS C8), p-nonylbenzene sulfonate (LAS C9), and p-dodecylbenzene sulfonate (LAS C12), was carried out by Nanzai et al. [54] with the aim of obtaining a comprehensive understanding of the interfacial region of cavitation bubbles, since LASs decompose primarily in this region. To investigate the reaction kinetics, a Langmuir-type mechanism was used in the study, and the initial concentrations of LASs were varied from 15 to 2000 µM. The degradation rate order for low concentrations of LAS (15–40 µM) was LAS C8 > LAS C9 > LAS C12, indicating diffusion-controlled degradation. Despite the fact that degradation rates increased with increasing initial LAS concentration, all LASs showed inflection points between 40 and 100 µM. A Langmuir-type process provided a reasonable explanation for this phenomenon. However, the same mechanism was not sufficient to explain the results at high LAS concentrations (100–2000 µM). An inflection point was found at around 40 µM for all LASs when H2O2 yields in the presence of LASs were quantified as a function of LAS concentration. While LAS scavenging at the bubble interface increased with increasing initial surfactant concentration in the bulk liquid, the primary ●OH degradation pathway was identified. However, the difference in LAS degradation rates suggested that the low and high LAS concentration regimes had different physicochemical properties at the cavitation bubble interface.

Using both pulsed and continuous wave (PW, CW) irradiation, Yang et al. [55] investigated the effects of ultrasonic frequency (206, 354, 620, 803, and 1062 kHz) on the degradation of octylbenzene sulfonic acid (OBSA). In contrast, the effect of frequency on the rate of formation of ●OH radicals was also investigated. For all frequencies, the decomposition of OBSA was consistent with pseudo-first order kinetics. For CW (with an optimum at 620 kHz), the OBSA degradation rate constant showed an order of 620 > 803 > 354 > 1062 > 206 kHz. For PW with T = 100 ms, it decreased with increasing frequency between 206 and 1062 kHz, and for T = 3.54 × 104 cycles/f) ms (T: minimum pulse length), it showed an optimum frequency at 354 kHz. Employing a pulse length and pulse interval of 100 ms each, a 300 % enhancement in OBS degradation was observed compared to continuous wave (CW) exposure with identical total sonication time. This result indicates that when the ultrasound frequency is changed during CW exposure, there is not always a relationship between the rates of ●OH radical production and OBSA degradation. Since the amount of OBSA that can accumulate on the gas/solution surface of cavitation bubbles is known to be affected by ultrasound frequency, the authors explained this effect by variations in ultrasound frequency. The effects of continuous wave (CW) and pulsed wave (PW) irradiation on the degradation of octylbenzene sulfonate (OBS: 1 mM) at 205 and 616 kHz (27 W) were also investigated by Deojay et al. [56]. Their results showed that the degradation of OBS is significantly influenced by both the sonication mode and frequency. Prolonged sonolysis tests showed a significant benefit of PW sonication. A clear inflection point in the first-order degradation rate of OBS was observed with CW sonolysis, resulting in a significant decrease in the degradation rate. On the other hand, PW sonolysis showed a faster rate than CW ultrasound while maintaining the first-order reaction rate. According to the scientists, PW ultrasound during pulse intervals changes the internal composition of sonochemically active bubbles, producing hotter bubbles with fewer organic by-products than bubbles exposed to CW. Aqueous perfluorobutane sulfonate (PFBS), perfluorobutanoate (PFBA), perfluorohexanoate (PFHA), and perfluorohexane sulfonate (PFHS) were studied by Campbell et al. [57] at dilute initial concentrations (<1 µM) over a frequency range of 202 to 1060 kHz (250 W/L) to investigate the sonochemical degradation kinetics at pH 7. The results of Vecitis et al. [27] for PFOS and PFOA were compared. The initial concentrations of the surfactants were degraded after 120 min of ultrasonic treatment at all frequencies. The percentages of degraded surfactants were PFBA (57 %), PFBS (66 %), PFHS (86 %), and PFHA (90 %). The time-dependent kinetics showed exponential degradation and followed pseudo-first order kinetics in all cases, indicating that the bubble/water contact was well below its maximum adsorption capacity. Below the maximum bubble surface adsorption values, degradation by interfacial pyrolysis was hypothesized for all surfactants. At 250 W/L and 358 kHz, the pseudo-first order rate constants (and half-lives) for the degradation of the six perfluorocompounds were as follows: PFHA [C6F11O2NH4]: 0.053 min−1 (16.8 min); PFOA [C8F15O2NH4]: 0.048 min−1 (16.9 min); PFHS [C6F13SO3K]: 0.030 min−1 (23.2 min); PFOS [C8F17SO3K]: 0.028 min−1 (25.7 min); PFBS [C4F9SO3K]: 0.018 min−1 (42.3 min); and PFBA [C4F7O2NH4]: 0.012 min−1 (57.2 min). Compared to the corresponding perfluorosulfonates (PFOS and PFHS), the degradation rates of the perfluorocarboxylates (PFOA and PFHA) were higher. In particular, the degradation rate of PFHA was higher than that of PFOS. This difference may be related to the lower thermal activation energies of the perfluorocarboxylates and the resulting higher intrinsic chemical reaction rates. While negligible effects of chain length on thermal activation energy were predicted, the degradation rate constant for the C4 sulfonate (PFBS) was 1.50 times that of the carboxylate (PFBA), suggesting a difference in bubble/water interface adsorption for the shorter chain. Perfluorobutyric acid (PFBA, 470 nM), perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHA, 320 nM), perfluorooctanoate (PFOA, 240 nM), and potassium perfluorobutane-1-sulfonate (PFBS, 300 nM), potassium perfluorohexane-1-sulfonate (PFHS, 230 nM), and potassium perfluoro-octane-1-sulfonate (PFOS, 200 nM) were all reported to be efficiently degraded at 202, 358, and 610 kHz with variable power densities of 83, 167, 250, and 333 W/L. This information was provided by Campbell and Hoffmann [58]. Due to their higher water solubility compared to their C8 counterparts, the more soluble and less hydrophobic PFBS and PFBA were shown to have slower sonochemical degradation rates than the longer chain analogs. In most situations, the measured degradation rate constants were found to increase linearly with increasing power density. This is because the rise in acoustic power leads to more intense bubble collapses, which improves the generation of free radicals and active species, in addition to enhancing the void fraction and size distribution of acoustic bubbles. For the various power densities applied, the best degradation was observed at 358 kHz. This outcome is in line with various literature findings [59], [60], [61], [62] indicating optimal sono-activity at around 300 kHz. Simultaneous exposure at 20 kHz and 202 kHz (dual frequency sonication) resulted in accelerated degradation rates of 12 % for PFOS and 23 % for PFOA. These results are in good agreement with CFD studies reporting an improvement in acoustic pressure distribution and intensity with the application of a dual-frequency process [63], [64], [65]. Ultrasonic degradation of perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) was correlated with sonochemical parameters (frequency variations: 44, 400, 500, and 1000 kHz) and sonoluminescence (SL)/sonochemiluminescence (SLC) intensity characteristics by Wood et al. [66]. No PFOS degradation was observed at 44 kHz. However, over the course of 4 h, degradation rates at 400, 500, and 1000 kHz reached 96.90 %, 93.80 %, and 91.20 %, respectively, accompanied by stoichiometric fluoride emission, suggesting PFOS molecular mineralization. The results of the investigation showed a strong relationship between the trends in PFOS degradation, KI oxidation, and SCL/SL intensity, indicating that degradation occurred in environments similar to these sonochemical processes. Interestingly, PFOS degradation did not show a corresponding decrease at 1000 kHz, when the overall collapse intensity (measured by SL) was greatly reduced. The authors postulated that PFOS may degrade under supersonic conditions via a hydrated electron degradation process.

The degradation rates of several sulfonic and carboxylic perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl compounds were evaluated at 500 kHz by Fernandez et al. [67], taking into account variations in chain length, functional head groups, and substituents (e.g., ether group and –CH2-CH2- moiety). In contrast to the results of Vecitis et al. [25], which showed a faster rate of sulfate formation than fluoride formation, defluorination was found to occur more readily than removal of sulfonate head groups. The researchers suggested that differences in compound concentrations and ultrasonic frequencies may be the cause of these different results. According to the study, extending the perfluoroalkyl chain improved the defluorination and degradation rates of the PFASs studied (PFOS, PFHxS, PFHxA, PFBS, PFOA, PFPA, 6:2 FTS, PFPrA, and PFEES). This behavior was related to the increasing hydrophobicity of PFAS. The head group had less of an effect on the degradation rate of PFAS; carboxylates with the same perfluorocarbon chain length degraded slightly faster than sulfonates. It was also observed that the rate of defluorination increased as the degree of fluorination increased.

Thirteen per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) were subjected to sonolytic degradation as studied by Shende et al. [68]. These included short-chain perfluorinated carboxylic acids, which have carbon chains of four to eight carbons; higher-chain perfluorocarboxylic acids, which have carbon chains of nine to fourteen carbons; and perfluorosulfonic acids, which have carbon chains of six and eight carbons. The study used a flow-through ultrasonic reactor and added salts along with various process parameters. The study highlighted the importance of PFAS chain length and frequency in the sonolytic degradation process. The statistics show that PFCA degradation rates increase with chain length up to carbon 9, at which point they begin to decrease. All PFAS degraded significantly faster at ambient temperature, 252 W/L power density, and alkaline pH. All PFAS compounds were degraded by over 97 % in 8 h at a power density of 144 W/L, with the exception of perfluorohexanoic acid (94 %) and perfluorobutonic acid (83 %). Thermolytic degradation of PFAS compounds is supported by the finding that the bond dissociation energy of C-F bonds is significantly greater than the experimental sonolytic activation energies. NaCl and NaHCO3 additions showed a sensitive chain length dependence. Overall, short to medium carbon chains showed enhanced degradation, while longer chains showed a reducing effect.

6. Surfactants degradation mechanism

After a thorough analysis of several studies on surfactant behavior and degradation under ultrasonic irradiation in the previous section, it has been repeatedly shown that non-volatile surfactants tend to accumulate near the gas/solution interface of cavitation bubbles. As a function of dissolved surfactant concentration (generally for C0 lower than CMC), degradation patterns partially follow the Langmuir-Hinshelwood mechanism [27], [54], [69], [70].

Table 4 summarizes the known degradation pathways for various surfactants under different sonochemical environments. Table 4 presents a variety of data indicating that oxidation by ●OH radicals [26], [28] and/or pyrolysis at the bubble interface [28], [29], [43], [57] are the major degradation pathways for nonvolatile surfactants. It is common to find pyrolysis products in the heated interfacial area of collapsing bubbles caused by surfactant degradation [25], [26], [28], [29]. Many studies emphasize pyrolysis within the gas phase for the volatile intermediates of various surfactants, although pyrolysis within the gas phase of the bubble is not observed for non-volatile surfactants due to their non-volatile nature [25], [26].

Table 4.

Survey of surfactant degradation mechanisms.

| Entry | Surfactant | Sonication conditions | Reaction mechanism/zone | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Triton X 100 | 358 kHz and 0.33 W/cm2, variable concentration | The initial decomposition of alkylphenolethoxylates occurs by both thermal decomposition and ●OH attack on the surfactant. |

Destaillats et al. [40] |

| 2 | Teric GN9 (apolydisperse nonylphenol ethoxylate surfactant) | 363 kHz and an intensity of 2 W/cm2, argon saturation, C0 = 0.01–0.11 mM) | The degradation process occurs at the bubbe/solution interface, driven by a combination of thermal and radical (●OH) reactions. Short-length intermediates subsequently undergo pyrolysis within the bubble, resulting in various pyrolytic components. | Vinodgopal et al. [47] |

| 3 | Sodium dodecylbenzenesulfonate (DBS) et sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS) | 200 kHz, 6 W/cm2, argon saturation, C0 = 10 µM | The surfactants accumulated to a relatively high extent in the interfacial region, undergoing reactions with hydroxyl radicals and also undergoing pyrolysis. | Yim et al. [29] |

| 4 | Sodium Dodecylbenzene Sulfonate (SDBS) | 362 kHz, 2.5 W/cm2, 200 mL, 20–30 °C, air atmosphere | ●OH radicals primarily attack SDBS molecules at the bubble/solution interface, producing volatile by-products that undergo degradation within the bubble, yielding pyrolysis products such as CH4, C2H6, ethane and C2H4. | Ashokkumar et al. [26] |

| 5 | sodium dodecylbenzene sulfonate | 20/80 kHz, power: 45–150 W, C0 = 15–30 mg/L | Interfacial decomposition with ●OH, with minimal reaction occurring in the bulk liquid. |

Manousaki et al. [129] |

| 6 | Perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) | 200 kHz, 3 W/cm2, argon saturation, C0 = 10 mg/L | PFOS and PFOA experience pyrolysis at the bubble/solution interface | Moriwaki et al. [43] |

| 7 | perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) | 354 kHz (250 W/L), 500 kHz (150 W/L) and 618 kHz (250 W/L), argon saturation, C0 = 10 µM | Loss of the ionic functional group occurs through the initial pyrolysis of PFOS and PFOA at the bubble interface, followed by the pyrolysis of the resulting volatile intermediates inside the gas phase of the bubble. | Vecitis et al. [25] |

| 8 | Perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) | 358 kHz and an applied power density of 250 W/L, argon saturation | PFOS destruction involves an initial, rate-determining ionic headgroup cleavage at the bubble/solution interface | Vecitis et al. [27] |

| 9 | perfluorobutanoate (PFBA), perfluorobutanesulfonate (PFBS), perfluorohexanoate (PFHA) and perfluorohexanesulfonate (PFHS) | 202–1060 kHz (250 W/L), C0:0.30 µM for PFBS, 0.47 µM for PFBA, 0.23 µM for PFHS and 0.32 µM for PFHA, argon saturation. | Interfacial pyrolysis decomposition mechanism was suggested | Campbell et al. [57] |

| 10 | Perfluorobutyric acid (PFBA), Perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHA), perfluorooctanoate (PFOA), Potassium perfluorobutane-1-sulfonate (PFBS), potassium perfluorohexane-1-sulfonate (PFHS), and Potassium perfluoro- octane-1-sulfonate (PFOS) | 202, 358 and 610 kHz for power densities of 83, 167, 250 and 333 W/L, air atmosphere | Surfactants undergo sonolytic degradation primarily at the bubble/water interface of the cavitation bubbles | Campbell and Hoffmann [58] |

| 11 | laurylpyridinium chloride (LPC) | 355 kHz, 18 W (acoustic), C0 = 0.1 to 0.6 mM, 20 ± 5 °C | The initial step in the degradation of LPC occurs primarily by a pyrolysis pathway at the bubble solution interface. | Singla et al. [128] |

| 12 | Octaethylene glycol monododecyl ether (C12E8) | 355 kHz, 18 W, C0 = 40 to 120 µM, 20 °C. | Hydroxylation/ oxidation of the surfactant and pyrolytic fragmentation of the surfactant, both at the bubble interface | Singla et al. [45] |

Whether it's pyrolysis or radical attack, the main process depends on the surfactant. To illustrate, after a long irradiation time of 12 h for the sonolysis of sodium dodecylbenzene sulfonate (SDBS), Ashokkumar et al. [26] find pyrolytic products that disappear in a shorter time. Due to the decrease in hydrogen peroxide production (corroborated by the increase in OH trapping) with the increase in SDBS concentration, it has been proposed that the main mechanism of degradation is ●OH radical attack followed by pyrolysis of volatile intermediates in the gas phase of the hot bubble. This mechanism has been supported by the absence of sonoluminescence quenching during the first five minutes of sonication, which indicates the initial formation of primary intermediates that are further attacked by radicals, leading to the formation of water-soluble products (such as oxalic acid) and volatile organics that are ultimately pyrolyzed within the bubbles over a long period of irradiation, resulting in the formation of pyrolytic products (CH4, C2H6, C2H4, C2H2), as shown in Fig. 4(a). Ashukkumar et al. [26] have proposed a mechanism for the likely products formed from the initial radical attack on SDBS, Fig. 4(b). Two pathways are suggested: (i) Based on the photodegradation of an alkylphenol ethoxylated surfactant [71], the OH• attack on the alkyl chain of SDBS is expected to occur along the entire alkyl chain, with the α- and β-positions being more probable [72]. This pathway shows one of the possible end products of the various RO•C6H4SO3– intermediates. (ii) The second pathway indicates the addition of OH• to the benzene ring at the ortho positions of the alkyl chain, due to the ortho- and meta-directing nature of the alkyl and SO3− groups, respectively, Fig. 4(b).

Fig. 4.

Mechanistic pathways for sonochemical degradation of SDBS in aqueous media (a), and reaction pathways following the reaction of OH• radicals with SDBS (b) [26].

On the other hand, Perfluorooctanoate and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOA and PFOS) were found to be primarily destroyed by pyrolysis at the bubble surface, with their fluorochemical intermediates undergoing successive pyrolytic reactions in the bubble vapor, according to Vecitis et al. [27], who report an immediate balanced release of pyrolysis products, F– and SO42–. This degradation pathway is corroborated by the findings of Moriwaki et al. [43], where the addition of 10 mM tert-butyl alcohol, a well-established hydroxyl radical (•OH) scavenger, exhibited a negligible effect (only 12 % reduction after 1 h of sonication) on PFOS degradation. This observation is further supported by the continuous formation of PFOA, the primary byproduct of PFOS degradation, even in the presence of tert-butyl alcohol, and at a comparable yield. Additionally, the absence of decomposition of independently tested PFOS and PFOA (0.02 mM) using Fenton reagents (0.2 mM Fe2+/H2O2, 1:1 M ratio) reinforces the pyrolytic mechanism.

Destaillats et al. [40] employed HPLC-ES-MS analyses to elucidate the sonodecomposition of Triton X-100. Their findings suggest that the process primarily targets the hydrophobic alkyl chain, which acts as the susceptible active site. As depicted in Fig. 5(a), the main reaction involves pyrolytic cleavage of the alkyl chain during bubble collapse. This phenomenon is likely coupled with the action of hydroxyl radicals (•OH) generated during the same event, Fig. 5(a). Additionally, the authors documented other reaction pathways, including the addition of •OH radicals to the aromatic ring (Fig. 5(b)) and their attack on the polyethoxylated chain (Fig. 5(c)), leading to either oxidized products or chains with a shorter polyethoxylate segment.

Fig. 5.

Degradation products arising from the sonication of TX.

In summary, most studies indicate that the initial ●OH radical attack and/or pyrolysis occurs at the bubble/solution interface, followed by the pyrolysis of volatile intermediates produced within the bubble gas phase. Surfactant concentration, sonication mode (continuous or pulsed), wave frequency, duration of sono-irradiation, and power intensity, which control the adsorption site (bubble surface area) and the percentage of molecules adsorbed on it, have a significant effect on these processes during sonication. A saturation concentration is reported in a number of cases [26], [27], [44], indicating the effectiveness of sonolysis in removing surfactants.

7. Parameters affecting ultrasonic removal of surfactants

The sonochemical reactivity of surfactants is highly dependent on operational factors such as solution pH, reactor design, emission surface area, frequency, power, saturating gases, liquid temperature, and initial surfactant concentrations. These variables affect the adsorption behavior of surfactant molecules on the cavitation bubble surface, which is the most reactive zone for these organic solutes, as well as the bubble dynamics and population. An overview of the factors affecting surfactant degradation (operating conditions) is given in Table 4. The following discussion provides an interpretation of the results for each parameter in Table 4.

7.1. Ultrasonication frequency and power

Two important acoustic elements that greatly affect the dynamics of the bubble cloud in a solution are the applied power and the acoustic frequency (f). The oscillation period (1/f) is related to the frequency, and the oscillating acoustic amplitude, PA = 2IaρLc)1/2, is proportional to the acoustic intensity (In). Specifically, the definition of acoustic intensity is In = Pac/S, which is the acoustic power divided by the surface area of the ultrasonic emitting device. Variations in the applied power or frequency can affect a number of factors such as (i) the maximum and minimum radius of the bubbles and the hot spot lifetime, (ii) the average temperature of the bubbles and the effectiveness of the reactions within them, (iii) the number density and distribution of the bubbles, and (iv) the dispersion of the radicals in the solution. Sonochemical events are governed by a combination of several interrelated elements.

Theoretical studies by Yasui et al. [22], Merouani et al. [73], [74], and Dehane et al. [75] have investigated the effects of intensity and frequency on the dynamics and chemistry of a single bubble. The combined results of all numerical simulations show that increasing the frequency between 20 and 1000 kHz results in a decrease in acoustic intensity between the Blake threshold (the minimum power that causes cavitation) and the falloff power (the maximum power that causes the ultrasound to be attenuated due to the formation of a gas layer between the transducer and the irradiated solution). The recovered numerical simulations, which included variables such as bubble temperature, pressure, and oxidant production, all supported the finding that single bubble efficiency increases with decreasing frequency or increasing intensity. This is explained by the larger resonance radius (Rmax) and smaller minimum close radius (Rmin) achieved by bubbles at higher power (lower frequency) during oscillation, which increases the maximum compression ratio (Rmax/Rmin). Under these circumstances, the bubbles burst more violently, generating significantly higher pressure and temperature. In addition, the response time during collapse is inversely related to the frequency reduction and proportional to the collapse time. Consequently, at lower frequencies or higher power densities, there is an increase in the sono-production of oxidants, mainly ●OH, within a single collapsing bubble. Furthermore, the size distribution of active bubbles increased with power, indicating a higher number of bubbles at higher applied power, while numerical calculations [76], [77], [78], [79] and experimental evidence [80] showed an increase in the number of actively collapsing bubbles with higher frequency (20–1000 kHz). Moreover, as is known, a sound field comprises both standing wave and traveling wave components. Notably, sonochemical yields exhibit optimization in the presence of traveling waves. The ratio between these two wave types varies as a function of frequency, with traveling waves becoming increasingly dominant at higher frequencies [81], [82], [83]. On the other side, at lower frequencies, the extended residence time of radicals within cavitation bubbles allows them to participate in reaction pathways analogous to those observed in flame reactions. Conversely, at higher frequencies, the rate of diffusion into the bulk solution is enhanced, leading to an increased release of hydroxyl radicals into the liquid phase [84]. In summary, the discussion can be reduced to two main points:

-

1)

While the number of bubbles increases with frequency, the temperature of the bubbles and the single bubble yield (hydroxyl radical formation) decrease.

-

2)

The temperature of the bubbles, their number, and the hydroxyl radical output (from a single bubble) all increase with increasing acoustic intensity.

Table 4, entry 1, provides an overview of the effects of acoustic frequency and power on the sonolytic degradation of various surfactants. The results show that higher frequencies are necessary for the most efficient degradation of surfactants, especially in the optimal frequency range of 358 to 615 kHz, where the best mineralization and degradation are shown. Lower frequencies (less than 100 kHz) are not effective for surfactant degradation by sonication [66]. However, almost all published studies indicate that the best degradation occurs as the applied sound intensity increases (see Table 4, entry 2). For some compounds, these patterns are consistent with previous reports [59], [61], [85], [86], [87], [88].

The interfacial region of the acoustic bubble is the preferred zone for surfactant degradation, either by pyrolysis or by ●OH flux from the interior of the bubble, as discussed in Section 6. As a result, the number of bubbles and the total interfacial area for surfactant adsorption are closely related. The increase in acoustic intensity leads to a rise in the single bubble temperature, the hydroxyl radical flux (available for surfactant decay) outside the acoustic bubbles, the interfacial contact region (available for surfactant adsorption) between bubbles and the surrounding solution, the size distribution of bubbles, and the number density (number of bubbles). As a result, depending on whether free radical oxidation or pyrolysis is used as the surfactant destruction mechanism, the total surfactant degradation rate may increase with increasing power (see Table 4, entry 2). Conversely, the conflict between the number of bubbles and the single bubble event (implosion intensity) may lead to the existence of an optimal frequency for the best destruction of surfactants. The single bubble yield (and bubble temperature) decreases with frequency (20–1000 kHz), but the number of bubbles increases. The improvement in number density (number of bubbles) with the rise of the applied frequency (from 20 to 1000 kHz) is mainly attributed to the reduction of bubble coalescence (relatively small bubbles are formed) and the improvement of acoustic pressure distribution in the sonicated solution (the damping effect of bubbles decreases). On the other hand, the decrease in bubble collapse intensity (and thus the single bubble yield) as the wave frequency increases is due to the shorter acoustic period (not enough time is available to achieve higher collapse ratios “Rmax/Rmin”). Nevertheless, the rapid bubble pulsation (as the acoustic period shortens) enhances the diffusion of generated radicals to the bubble-solution interface where surfactant molecules are adsorbed. As a consequence, the intricate interplays between these factors may lead to a frequency balance of the overall performance of the surfactant cavitation treatment, where the frequency effect is controlled by the single bubble event above this optimum, while the number of bubbles below it dominates the degradation process.

7.2. Saturating gas

Compared to air and other polyatomic gases, the degradation results shown in Table 4, entry 3, demonstrate the extremely successful treatment of surfactants under argon saturation. Since bubble interface pyrolysis is the primary pathway for surfactant degradation, it is critical to continuously generate higher bubble temperatures to improve the thermal conversion of surfactant molecules at the bubble interface. Because argon has a lower thermal conductivity (λAr = 179 × 10−4 W/m K, λair = 259 × 10−4 W/m K) and a higher specific heat ratio (γar = 1.66, γair = 1.40), it can cause intense collapses at higher bubble (and interface) temperatures, which increases the efficiency of surfactant molecules adsorbed during pyrolysis. This efficiency is related to the higher solubility of argon than air, or xAr (mol/mol) = 2.748 × 10−5 and xair = 1.524 × 10−5, which allows it to produce a larger bubble flow than air. The positive effect of argon gas (Table 4, entry 3) is corroborated by findings from various literature studies [89], [90], [91], [92].

Thus, if pyrolysis at the bubble interface is the primary degradation pathway, all of the sonochemical activity for surfactant degradation could be achieved in an argon environment. It's important to remember that other sonication parameters such as frequency, power, or media temperature can affect the gas effect. Recent works indicate that at frequencies exceeding 515 kHz, the rate of hydroxyl radical (•OH) production diminishes in the following order: Ar > O2 > air > N2. Conversely, at a lower frequency of 213 kHz, the order of •OH production rate becomes O2 > air ≈ N2 > Ar. These outcomes were attributed to the influence of bubble size, reactivity of saturating gas within bubbles, and the variation in reaction time available, which is in turn related to the applied frequency [74]. As shown in Table 4, entry 3, the majority of studies investigating the impact of saturating gas are performed under a single frequency (200 kHz). Therefore, the effects of saturating gas on surfactant degradation should be analyzed using a larger range of wave frequencies and even under a multifrequency system.

7.3. Initial concentration