Abstract

NADPH oxidase is the major source of superoxide production in cardiovascular tissues. We and others reported that PG (prostaglandin) F2α, PDGF (platelet-derived growth factor) and angiotensin II cause hypertrophy of vascular smooth muscle cells by induction of NOX1 (NADPH oxidase 1), a catalytic subunit of NADPH oxidase. We found DPI (diphenylene iodonium), an inhibitor of flavoproteins, including NADPH oxidase itself, almost completely suppressed induction of NOX1 mRNA by PGF2α or PDGF in a rat vascular smooth muscle cell line, A7r5. Exploration into the site of action of DPI using various inhibitors suggested the involvement of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in PGF2α- or PDGF-induced increase in NOX1 mRNA. In a luciferase reporter assay, activation of the CRE (cAMP-response element)-dependent gene transcription by PGF2α was attenuated by oligomycin, an inhibitor of mitochondrial FoF1-ATPase. Oligomycin and other mitochondrial inhibitors also suppressed PGF2α-induced phosphorylation of ATF (activating transcription factor)-1, a transcription factor of the CREB (CRE-binding protein)/ATF family. Silencing of the ATF-1 gene by RNA interference significantly reduced the induction of NOX1 by PGF2α or PDGF, while overexpression of ATF-1 recovered NOX1 induction suppressed by oligomycin. Taken together, ATF-1 may play a pivotal role in the up-regulation of NOX1 in rat vascular smooth muscle cells.

Keywords: activating transcription factor 1 (ATF-1), mitochondrion, NADPH oxidase, NOX1, prostaglandin F2α

Abbreviations: AP1, activating protein 1; ATF, activating transcription factor; CRE, cAMP-response element; CREB, CRE-binding protein; DMEM, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium; DPI, diphenylene iodonium; ds, double-stranded; ERK, extracellular-signal-regulated kinase; FBS, foetal bovine serum; MnTBAP, Mn(III)tetrakis(4-benzoic acid)porphyrin chloride; MTT, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide; NOS, nitric oxide synthase; NOX1, NADPH oxidase 1; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; PG, prostaglandin; PKCε, protein kinase Cε; SOD, superoxide dismutase; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cell

INTRODUCTION

ROS (reactive oxygen species), including superoxide (O2−) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), are recognized as important signalling molecules in cardiovascular tissues. It has been shown that NADPH oxidases are the major source of O2− in vascular cells and myocytes [1–4]. Homologues of the catalytic subunit of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase (gp91phox; NOX2) have been found in VSMCs (vascular smooth muscle cells). Among them, NOX1 (NADPH oxidase 1) was implicated in the pathogenesis of arteriosclerosis and reperfusion injury, since it mediates the proliferation and hypertrophy of VSMCs [5–7]. Expression of NOX1 is increased by stimulation with PDGF (platelet-derived growth factor), angiotensin II, phorbol ester or FBS (foetal bovine serum) [5,6]. We reported previously that PG (prostaglandin) F2α, one of the primary prostanoids generated in the vascular tissue, causes hypertrophy of VSMCs by induction of NOX1 and subsequent increase in O2− generation [7]. It thus appears that O2− derived from NADPH oxidase serves as a signalling molecule that elicits vascular hypertrophy.

On the other hand, there is little information on the exact molecular mechanisms underlying the up-regulation of NOX1 gene expression in VSMCs. We have found that a flavoprotein inhibitor DPI (diphenylene iodonium) markedly suppresses induction of NOX1 mRNA by PGF2α, PDGF, FBS or PMA. As DPI is commonly used as an inhibitor of NADPH oxidase by forming adducts with reduced flavin [8–10], experiments were carried out to elucidate the site of action for DPI on the signalling pathway leading to the induction of NOX1 gene expression. In the present paper, we report the first evidence for the roles of mitochondria and ATF (activating transcription factor)-1, a member of the CREB (cAMP-response-element-binding protein)/ATF family, in the regulation of rat NOX1 gene expression.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

[α-32P]UTP and [α-32P]dCTP (3000 Ci/mmol) were obtained from ICN Biomedicals (Costa Mesa, CA, U.S.A.). PDGF-AB, PMA, DPI chloride, tiron, rotenone, antimycin A and oligomycin were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). MnTBAP [Mn(III)tetrakis(4-benzoic acid)porphyrin chloride], EUK-8 and CCCP (carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone) were obtained from Calbiochem-Novabiochem (San Diego, CA, U.S.A.). PGF2α, G418 disulphate and protease inhibitor cocktails were purchased from Nacalai Tesque (Kyoto, Japan). Plasmids containing specific enhancer element–luciferase fusion DNA (Mercury Pathway Profiling Systems) were obtained from Clontech (Palo Alto, CA, U.S.A.).

Northern blot analysis

A7r5 cells obtained from the A.T.C.C. (Manassas, VA, U.S.A.) were maintained in DMEM (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium) supplemented with 10% FBS. Before the addition of reagents, cells were cultured in DMEM containing 0.5% FBS for 48 h. Cells were then incubated with 100 nM PGF2α, 20 ng/ml PDGF-AB, 10% FBS or 100 nM PMA in the presence or absence of various inhibitors for 24 h. RNA isolation and Northern blot analyses were performed essentially as described in [7]. Cell viability was determined using the MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide] assay essentially as described previously [11].

Luciferase assay

A7r5 cells were seeded in six-well plates and were cultured for 24 h in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. Luciferase plasmids (1 μg/well) and pSV-β-galactosidase control vector (0.5 μg/well; Promega, Madison, WI, U.S.A.) were co-transfected into the cells with FuGENE 6 Transfection Reagent (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, U.S.A.). After transfection, cells were cultured for 24 h in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, and then in the absence of FBS for another 24 h. Cells were then incubated with 100 nM PGF2α in the presence or absence of 2 μg/ml oligomycin for 24 h. Cell lysates were prepared, and luciferase activity normalized to β-galactosidase activity was determined according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Western blot analysis

A7r5 cells cultured in the absence of FBS for 48 h were pre-treated with mitochondrial inhibitors for 30 min, and then incubated with 100 nM PGF2α for 5 min. Nuclear extracts were prepared as described previously [11,12]. Briefly, cells were suspended in buffer A (10 mM Hepes/KOH, pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2 and 10 mM KCl) containing protease inhibitor cocktails, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM NaF, 20 mM β-glycerophosphate and 1 mM Na3VO4. After centrifugation, the pellets were resuspended in buffer C (20 mM Hepes/KOH, pH 7.9, 25% glycerol, 420 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2 and 0.2 mM EDTA) containing the inhibitors described above. The supernatants obtained after centrifugation were used as nuclear extracts. The extracts (10 μg) were separated by SDS/12.5% PAGE, and transferred on to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, U.S.A.). Membranes were incubated with anti-phospho-CREB antibody (reactive with phosphorylated forms of CREB and ATF-1; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, U.S.A.) or monoclonal anti-ATF-1 antibody (25C10G; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, U.S.A.), and then with anti-rabbit IgG or anti-mouse IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase respectively. Immunoreactive bands were detected using ECL® (enhanced chemiluminescence) Plus System (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, U.S.A.).

Synthesis of an anti-ATF-1 ds (double-stranded) RNA

A dsRNA expression vector, pcPURU6icassette, was constructed by insertion of puromycin N-acetyltransferase gene to pU6icassette vector [13,14], which contains a human U6 promoter and two BfuAI (BspMI) sites. An anti-ATF-1 dsRNA was designed that targeted nucleotides 247–267 of the rat cDNA clone BU671705. Sense or antisense oligonucleotides containing the hairpin sequence, the terminator sequence and overhanging sequences were synthesized, amplified by PCR, digested by BfuAI, and inserted into the BfuAI site of the pcPURU6icassette.

Establishment of clones stably expressing an anti-ATF-1 dsRNA

The dsRNA expression vector (pcPURU6icassette containing an anti-ATF-1 dsRNA sequence) was transfected into A7r5 cells as described above. Stable transfectants were selected by single-cell cloning in the presence of puromycin (5 μg/ml). For mock transfection, the pcPURU6icassette vector was transfected and selected with puromycin.

Establishment of clones stably expressing ATF-1

The coding region of the rat ATF-1 cDNA was amplified by RT (reverse transcriptase)-PCR and inserted into pcDNA3. The plasmid was transfected into A7r5 cells as described above, and stable transfectants were selected by single-cell cloning in the presence of G418 (1 mg/ml).

Statistical analysis

Values were expressed as means±S.E.M. Statistical analysis was performed with Student's t test. For multiple treatment groups, one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's t test was applied.

RESULTS

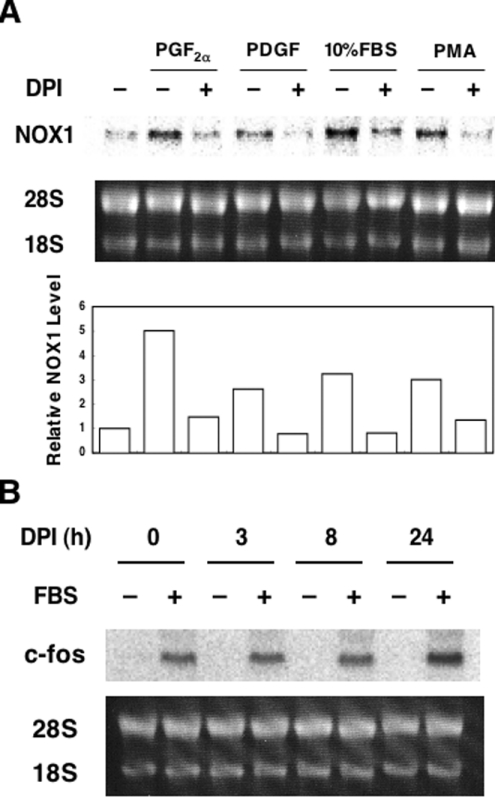

DPI suppresses induction of NOX1 mRNA

As we reported previously, PGF2α increases NOX1 mRNA levels in rat VSMCs, A7r5 [7]. In the course of the investigation on the signalling pathways that mediate PGF2α-induced NOX1 expression, we found that 100 nM DPI, an inhibitor of NADPH oxidase, almost completely suppressed induction of NOX1 mRNA by PGF2α. DPI also suppressed increased NOX1 mRNA induced by PDGF, 10% FBS or PMA (Figure 1A). The MTT assay demonstrated that more than 85% of the cells were viable when cells were incubated in the presence of 100 nM DPI for 24 h (results not shown). In these cells, induction of c-fos by 10% FBS was clearly observed (Figure 1B). These findings suggest that the suppressive effect of DPI on NOX1 induction is not due to cell damage.

Figure 1. DPI suppressed induction of NOX1 mRNA, but not of c-fos mRNA.

(A) Effects of DPI on induction of NOX1 mRNA. A7r5 cells, maintained in DMEM with 0.5% FBS for 48 h, were incubated with 100 nM PGF2α, 20 ng/ml PDGF-AB, 10% FBS or 100 nM PMA for 24 h in the presence or absence of 100 nM DPI. A representative autoradiograph of three experiments is demonstrated. Average expression levels of NOX1 normalized to 28 S RNA are shown below the blot. (B) Effects of DPI on induction of c-fos mRNA by FBS. Growth-arrested A7r5 cells were incubated with 100 nM DPI for the indicated times and then stimulated with 10% FBS for 30 min. Northern blot analysis was performed as described in the Experimental section.

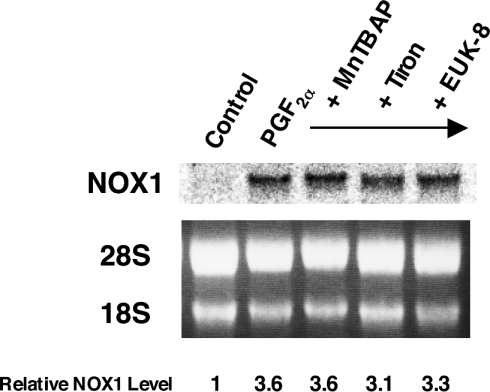

Scavengers of O2− have no effect on induction of NOX1 mRNA

To elucidate further the effect of DPI on NOX1 induction, we first examined whether scavengers of O2−, the reaction product of NADPH oxidase, could affect NOX1 gene expression. MnTBAP, a cell-permeant SOD (superoxide dismutase) mimetic and peroxynitrite scavenger, and tiron, a cell-permeant O2− scavenger, did not affect induction of NOX1 by PGF2α. Furthermore, EUK-8, a synthetic salen–manganese complex with high SOD, catalase and oxyradical scavenging activities, showed no effect on NOX1 induction by PGF2α (Figure 2). These results suggest that NOX1 induction is not mediated by O2−, H2O2 or oxyradicals, and that the effect of DPI on NOX1 induction is not due to the inhibition of NADPH oxidase activity by DPI. DPI is also known as an inhibitor of NOS (nitric oxide synthase) [15]. NG-monomethyl-L-arginine (L-NMMA), an inhibitor of NOS, however, did not suppress NOX1 induction by PGF2α (results not shown). Thus involvement of NO in induction of NOX1 mRNA was ruled out.

Figure 2. Scavengers of O2− had no effect on induction of NOX1 mRNA by PGF2α.

A7r5 cells, maintained in DMEM with 0.5% FBS for 48 h, were incubated with 100 μM MnTBAP, 10 mM tiron or 50 μM EUK-8 for 24 h in the presence of 100 nM PGF2α. A representative autoradiograph of three experiments is demonstrated. Relative expression levels of NOX1 normalized to 28 S RNA are shown below the blot.

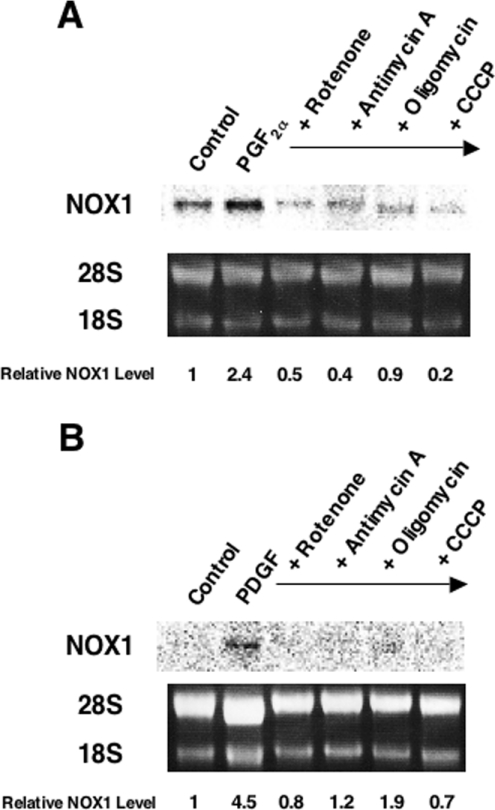

Inhibitors of the mitochondrial respiratory chain suppress induction of NOX1 mRNA

DPI inhibits complex I in the mitochondrial respiratory chain in addition to NADPH oxidase [16]. Therefore involvement of the electron transport system in NOX1 induction was examined next. Rotenone and antimycin A, inhibitors of complexes I and III respectively, blocked induction of NOX1 by PGF2α almost completely. Similarly, NOX1 induction by PGF2α was suppressed by an inhibitor of FoF1-ATPase, oligomycin, and by an uncoupler of oxidative phosphorylation, CCCP (Figure 3A). All of these inhibitors also suppressed PDGF-induced expression of NOX1 (Figure 3B). In the presence of these mitochondrial inhibitors, induction of c-fos by 10% FBS was preserved (see Supplementary Figure 1 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/386/bj3860255add.htm). In a flow-cytometric analysis using a fluorescent dye, JC-1, we confirmed that the same concentration of CCCP markedly reduced mitochondrial membrane potential (results not shown). In the MTT assay, over 75% of cells were viable in the presence of rotenone or CCCP. As for antimycin A and oligomycin, these inhibitors did not affect cell viability (results not shown). These results therefore suggest that inhibition of mitochondrial respiratory chain suppresses NOX1 induction by PGF2α and PDGF.

Figure 3. Inhibitors of the mitochondrial respiratory chain suppressed induction of NOX1 mRNA.

A7r5 cells, maintained in DMEM with 0.5% FBS for 48 h, were incubated with 500 nM rotenone, 100 ng/ml antimycin A, 2 μg/ml oligomycin or 10 μM CCCP for 24 h in the presence of 100 nM PGF2α (A) or 20 ng/ml PDGF-AB (B). Representative autoradiographs of three experiments are demonstrated. Relative expression levels of NOX1 normalized to 28 S RNA are shown below the blots.

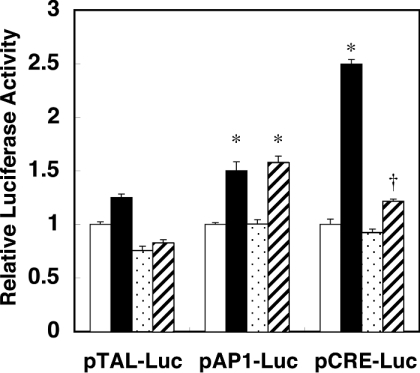

CRE (cAMP-response element)-dependent transcriptional activation by PGF2α is suppressed by oligomycin

To clarify the signal transduction pathway that mediates mitochondria to the nucleus, we screened transcription factors that are activated by PGF2α and inhibited by mitochondrial inhibitors. A7r5 cells were transfected with plasmids containing specific enhancer elements fused to luciferase DNA, and stimulated with PGF2α in the presence or absence of oligomycin. Among AP1 (activating protein 1)-binding site, CRE, glucocorticoid-response element, heat-shock element, NF-κB (nuclear factor κB)-binding site and serum-response element, only CRE-dependent transcription was enhanced by PGF2α greater than 2-fold over the control. As shown in Figure 4, AP1-dependent transcriptional activity was slightly enhanced by PGF2α, which appeared to be linked to the concomitant induction of c-fos by PGF2α that binds to AP1 sites [17]. In contrast with the AP1-dependent activation, however, the CRE-dependent transcriptional activation by PGF2α was significantly suppressed by oligomycin.

Figure 4. CRE-dependent transcriptional activation by PGF2α was suppressed by oligomycin.

Luciferase plasmids containing various enhancer elements were co-transfected with β-galactosidase control vector into A7r5 cells. The activity of luciferase was normalized by that of β-galactosidase. Results are means±S.E.M. (n=3). pTAL-Luc, the control vector lacking the enhancer element. pAP1-Luc, the luciferase plasmid containing the AP1-binding site. pCRE-Luc, the luciferase plasmid containing the CRE. Open bars, control; closed bars, PGF2α; dotted bar, oligomycin; hatched bar, PGF2α+oligomycin. *P<0.001 compared with the control. †P<0.001 compared with PGF2α.

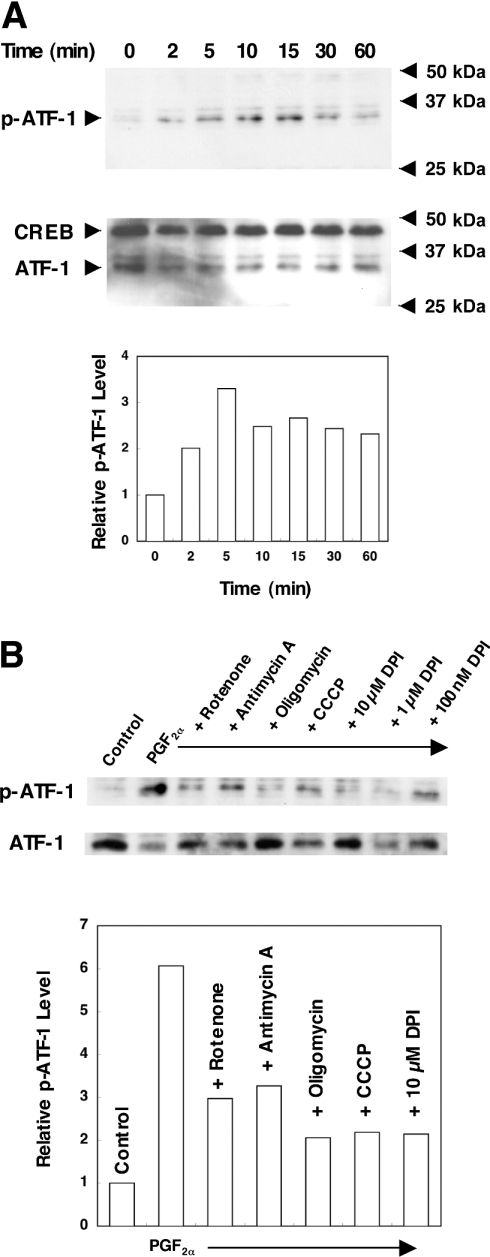

Inhibitors of the mitochondrial respiratory chain suppress phosphorylation of ATF-1 by PGF2α

CRE-dependent transcription is mediated by transcription factors of the CREB/ATF family. Of particular interest is the fact that the involvement of CREB and ATF-1 in angiotensin-II-induced hypertrophy and thrombin-induced growth of VSMCs has been reported [18,19]. We therefore examined whether PGF2α induces phosphorylation of these proteins. As shown in Figure 5(A), a 35 kDa protein was detected in the nuclear extracts of PGF2α-stimulated cells by the anti-phospho-CREB antibody, which reacts with phosphorylated forms of CREB and ATF-1. While the phosphorylated form of CREB (43 kDa) was not detected in these cells, a time-dependent increase in phosphorylation of ATF-1 was observed up to 15 min. These findings suggest that PGF2α elicits phosphorylation of ATF-1, but not that of CREB. PDGF also elicited phosphorylation of ATF-1 in a similar time course (results not shown). Effects of mitochondrial inhibitors on PGF2α-induced phosphorylation of ATF-1 were next examined. As shown in Figure 5(B), DPI and all other mitochondrial inhibitors suppressed phosphorylation of ATF-1 induced by PGF2α. DPI also suppressed PDGF-induced phosphorylation of ATF-1 (results not shown).

Figure 5. Inhibitors of the mitochondrial respiratory chain suppressed phosphorylation of ATF-1 by PGF2α.

(A) Time course of ATF-1 phosphorylation by PGF2α. Serum-starved A7r5 cells were incubated with 100 nM PGF2α for the indicated times. (B) Effects of various inhibitors of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Serum-starved A7r5 cells were pre-incubated with 500 nM rotenone, 100 ng/ml antimycin A, 2 μg/ml oligomycin, 10 μM CCCP or the indicated concentrations of DPI for 30 min, and stimulated with 100 nM PGF2α for 5 min. Western blot analysis was performed as described in the Experimental section. Representative results of three experiments are shown. Averaged relative intensities of the bands for phosphorylated ATF-1 are shown below the blots.

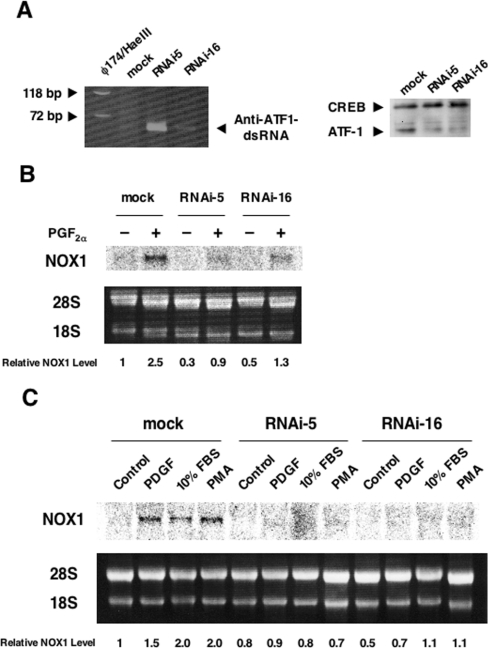

Gene silencing of ATF-1 attenuates induction of NOX1 mRNA

To verify further the involvement of ATF-1 in the induction of NOX1 gene expression, a dsRNA targeted at the rat ATF-1 mRNA sequence was introduced into A7r5 cells. Following single cell cloning of the transfectants, two clones (RNAi-5 and RNAi-16) stably expressing the dsRNA were isolated (Figure 6A, left-hand panel). In RNAi-5 and RNAi-16, the levels of ATF-1, but not those of CREB, were significantly reduced compared with mock-transfected cells (Figure 6A, right-hand panel). As demonstrated in Figure 6(B), induction of NOX1 mRNA by PGF2α in these cells was abolished almost completely. In addition, induction of NOX1 mRNA by PDGF, 10% FBS or PMA was also inhibited in these clones (Figure 6C). In these clones, induction of c-fos by 10% FBS was clearly observed (see Supplementary Figure 2 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/386/bj3860255add.htm).

Figure 6. Gene silencing of ATF-1 attenuated induction of NOX1 mRNA.

(A) Expression of the anti ATF-1 dsRNA (left-hand panel) and silencing of ATF-1 expression (right-hand panel) in the clones RNAi-5 and RNAi-16. Total RNA was reverse-transcribed with random nonomers, and the cDNA fragment (57 bp) was amplified by PCR. The product was separated by 15% PAGE. Western blot analysis was performed as described in the Experimental section. (B) Induction of NOX1 mRNA by PGF2α was suppressed in RNAi-5 and RNAi-16. (C) Induction of NOX1 mRNA by PDGF, 10% FBS or PMA was suppressed in RNAi-5 and RNAi-16. Northern blot analysis was performed as described in the Experimental section. Relative expression levels of NOX1 normalized to 28 S RNA are shown below the blots.

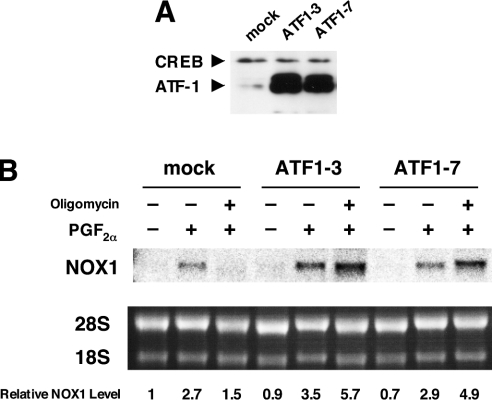

Overexpression of ATF-1 restores PGF2α-induced NOX1 expression suppressed by oligomycin

To examine the effects of overexpression of ATF-1 on NOX1 induction, an expression plasmid containing the coding region of rat ATF-1 cDNA was introduced into A7r5 cells. Following single cell cloning of the transfectants, two clones stably expressing ATF-1, ATF1-3 and ATF1-7 were isolated (Figure 7A). As shown in Figure 7(B), induction of NOX1 by PGF2α in these clones was observed in the presence of oligomycin. These findings, together with the results of gene silencing of ATF-1, clearly indicate that ATF-1 is an essential transcription factor that mediates expression of NOX1 gene in rat VSMCs.

Figure 7. Overexpression of ATF-1 restored PGF2α-induced NOX1 expression suppressed by oligomycin.

(A) Overexpression of ATF-1 in the clones ATF1-3 and ATF1-7. Western blot analysis was performed as described in the Experimental section. (B) Induction of NOX1 mRNA by PGF2α was not affected by oligomycin in ATF1-3 and ATF1-7. Northern blot analysis was performed as described in the Experimental section. Relative expression levels of NOX1 normalized to 28 S RNA are shown below the blot.

DISCUSSION

The present findings suggest that ATF-1, a transcription factor of the CREB/ATF family, plays an essential role in the induction of NOX1 mRNA. The major lines of evidence provided in the present study are that: (i) DPI, which inhibits NADPH oxidase in addition to complex I in the mitochondrial respiratory chain, almost completely abolished induction of NOX1 mRNA by PGF2α, PDGF, FBS or PMA; (ii) the increase in NOX1 mRNA induced by PGF2α or PDGF was attenuated by inhibitors of the mitochondrial respiratory chain; (iii) CRE-dependent transcriptional activation by PGF2α was suppressed by oligomycin, an inhibitor of mitochondrial FoF1-ATPase; (iv) phosphorylation of ATF-1 induced by PGF2α was attenuated by inhibitors of the mitochondrial respiratory chain; (v) induction of NOX1 mRNA by PGF2α, PDGF, FBS or PMA was suppressed by RNA interference targeted at the ATF-1 mRNA sequence; and (vi) overexpression of ATF-1 restored NOX1 expression that was suppressed by oligomycin.

The flavoprotein inhibitor DPI is often used as an inhibitor of NADPH oxidase [8–10], because it reduces the activity of NADPH oxidase by forming adducts with reduced flavin [20]. The present findings suggest that DPI is not only an enzyme inhibitor of NADPH oxidase, but also a down-regulator of NOX1, a catalytic subunit of the enzyme. In the latter effect of DPI, implication of the mitochondrial respiratory chain was demonstrated.

In the same member of the CREB/ATF family, CREB was reported to be one of the transcription factors activated by mitochondrial dysfunction. Arnould et al. [21] reported that CREB is involved in the signalling pathway that communicates the state of the activity of mitochondria to the nucleus. In the mtDNA (mitochondrial DNA)-depleted cell line, CREB was constitutively activated by phosphorylation on Ser133, and metabolic inhibitors of mitochondria led to phosphorylation of CREB in human embryonic kidney cells [21]. In contrast, metabolic inhibitors of mitochondria suppressed PGF2α-induced phosphorylation of ATF-1 in A7r5 cells. Such a discrepancy in the relationship between the phosphorylation status of CREB/ATF and mitochondrial activities may be attributed to the difference in the cell lineage used in these studies.

ATF-1, but not CREB, was phosphorylated in the cells stimulated by PGF2α, although high sequence similarity is found in the sites phosphorylated by serine/threonine kinases. This suggests that strict mechanisms that distinguish phosphorylation sites of ATF-1 and CREB exist, and ATF-1 and CREB may have distinct functional roles in VSMCs. In fact, ATF-1 was reported to be involved in thrombin-induced growth of VSMCs, while CREB was implicated in angiotensin-II-induced hypertrophy of VSMCs [18,19]. We reported previously that PGF2α-induced hypertrophy of VSMCs was mediated by induction of NOX1 mRNA [7]. In the light of the present findings, involvement of ATF-1 in PGF2α-induced hypertrophy of VSMCs was clearly depicted. It is intriguing that the angiotensin AT1 receptor, the thrombin receptor and the prostanoid FP (PGF) receptor are all Gq/11-coupled receptors. These receptors may be coupled to as yet unidentified activation units that discriminate between ATF-1 and CREB.

The molecular mechanisms by which PGF2α- or PDGF-induced signals are propagated to mitochondria and to the transcription factor ATF-1 are still unknown. PGF2α exerts its biological actions through binding to its specific receptor, FP, on plasma membranes [22]. FP is coupled to phosphoinositide turnover and ensuing mobilization of cytosolic Ca2+ [23]. PGF2α also induces translocation of PKCε (protein kinase Cε) to the myocyte membrane [17]. On the other hand, previous studies have demonstrated that PKCδ and PKCε are targeted to mitochondria upon activation, and PKCδ changes mitochondrial membrane potential [24–26]. It is also reported that PKCε co-localizes with ERK (extracellular-signal-regulated kinase) in cardiac mitochondria, and forms PKCε–ERK signalling modules that take part in PKCε-mediated cardioprotection [27]. PDGF, whose effects are mediated by the receptor tyrosine kinase, is also reported to activate ERK by a PKC-dependent manner [28]. In another line of study, we observed that PGF2α-induced expression of NOX1 mRNA was significantly suppressed by PD98059, an inhibitor of MEK1/2 (mitogen-activated protein kinase/ERK kinase 1/2) that blocks ERK1/2 pathway (C. Fan, M. Katsuyama, T. Nishinaka and C. Yabe-Nishimura, unpublished work). As localization of CREB was also reported in brain mitochondria [29], it can be postulated that these PKCs may mediate PGF2α- or PDGF-induced signals to mitochondria, and that ERK and/or ATF-1 closely associated with mitochondria may play pivotal roles in transducing the signals to the nucleus, leading to expression of the NOX1 gene. It is as yet unclear whether ATF-1 directly or indirectly activates transcription of NOX1. A PGF2α-responsive element(s) has not been found by the luciferase reporter assay using a construct containing approx. 2 kb of the 5′-flanking region of the mouse NOX1 gene (results not shown). Further studies on the promoter and enhancer of the NOX1 gene should lead to the better understanding of the regulation of NOX1 gene expression in VSMCs. The present study provides the first evidence for the roles of mitochondria and ATF-1, a member of CREB/ATF family, in the regulation of NOX1 gene expression.

Multimedia adjunct

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) 14770036 from The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan. We thank Dr E. Funakoshi of the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Setsunan University, Hirakata, Osaka, Japan, for valuable discussion and advice.

References

- 1.Griendling K. K., Sorescu D., Ushio-Fukai M. NAD(P)H oxidase: role in cardiovascular biology and disease. Circ. Res. 2000;86:494–501. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.5.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guzik T. J., West N. E., Black E., McDonald D., Ratnatunga C., Pillai R., Channon K. M. Vascular superoxide production by NAD(P)H oxidase: association with endothelial dysfunction and clinical risk factors. Circ. Res. 2000;86:E85–E90. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.9.e85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Irani K. Oxidant signaling in vascular cell growth, death, and survival: a review of the roles of reactive oxygen species in smooth muscle and endothelial cell mitogenic and apoptotic signaling. Circ. Res. 2000;87:179–183. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.3.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lassègue B., Clempus R. E. Vascular NAD(P)H oxidases: specific features, expression, and regulation. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2003;285:R277–R297. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00758.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suh Y. A., Arnold R. S., Lassègue B., Shi J., Xu X., Sorescu D., Chung A. B., Griendling K. K., Lambeth J. D. Cell transformation by the superoxide-generating oxidase Mox1. Nature (London) 1999;401:79–82. doi: 10.1038/43459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lassègue B., Sorescu D., Szöcs K., Yin Q., Akers M., Zhang Y., Grant S. L., Lambeth J. D., Griendling K. K. Novel gp91phox homologues in vascular smooth muscle cells: NOX1 mediates angiotensin II-induced superoxide formation and redox-sensitive signaling pathways. Circ. Res. 2001;88:888–894. doi: 10.1161/hh0901.090299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katsuyama M., Fan C., Yabe-Nishimura C. NADPH oxidase is involved in prostaglandin F2α-induced hypertrophy of vascular smooth muscle cells: induction of NOX1 by PGF2α. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:13438–13442. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111634200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellis J. A., Mayer S. J., Jones O. T. The effect of the NADPH oxidase inhibitor diphenyleneiodonium on aerobic and anaerobic microbicidal activities of human neutrophils. Biochem. J. 1988;251:887–891. doi: 10.1042/bj2510887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robertson A. K., Cross A. R., Jones O. T., Andrew P. W. The use of diphenylene iodonium, an inhibitor of NADPH oxidase, to investigate the antimicrobial action of human monocyte derived macrophages. J. Immunol. Methods. 1990;133:175–179. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(90)90357-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doussiere J., Vignais P. V. Diphenylene iodonium as an inhibitor of the NADPH oxidase complex of bovine neutrophils: factors controlling the inhibitory potency of diphenylene iodonium in a cell-free system of oxidase activation. Eur. J. Biochem. 1992;208:61–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishinaka T., Yabe-Nishimura C. EGF receptor-ERK pathway is the major signaling pathway that mediates upregulation of aldose reductase expression under oxidative stress. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2001;31:205–216. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00571-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andrews N. C., Faller D. V. A rapid micropreparation technique for extraction of DNA-binding proteins from limiting numbers of mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:2499. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.9.2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyagishi M., Taira K. U6 promoter-driven siRNAs with four uridine 3′ overhangs efficiently suppress targeted gene expression in mammalian cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002;20:497–500. doi: 10.1038/nbt0502-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yokota T., Sakamoto N., Enomoto N., Tanabe Y., Miyagishi M., Maekawa S., Yi L., Kurosaki M., Taira K., Watanabe M., Mizusawa H. Inhibition of intracellular hepatitis C virus replication by synthetic and vector-derived small interfering RNAs. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:602–608. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stuehr D. J., Fasehun O. A., Kwon N. S., Gross S. S., Gonzalez J. A., Levi R., Nathan C. F. Inhibition of macrophage and endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase by diphenyleneiodonium and its analogs. FASEB J. 1991;5:98–103. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.5.1.1703974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y., Trush M. A. Diphenyleneiodonium, an NAD(P)H oxidase inhibitor, also potently inhibits mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998;253:295–299. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adams J. W., Sah V. P., Henderson S. A., Brown J. H. Tyrosine kinase and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase mediate hypertrophic responses to prostaglandin F2α in cultured neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. Circ. Res. 1998;83:167–178. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Funakoshi Y., Ichiki T., Takeda K., Tokuno T., Iino N., Takeshita A. Critical role of cAMP-response element-binding protein for angiotensin II-induced hypertrophy of vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:18710–18717. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110430200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghosh S. K., Gadiparthi L., Zeng Z. Z., Bhanoori M., Tellez C., Bar-Eli M., Rao G. N. ATF-1 mediates protease-activated receptor-1 but not receptor tyrosine kinase-induced DNA synthesis in vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:21325–21331. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201608200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Donnell B. V., Tew D. G., Jones O. T., England P. J. Studies on the inhibitory mechanism of iodonium compounds with special reference to neutrophil NADPH oxidase. Biochem. J. 1993;290:41–49. doi: 10.1042/bj2900041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arnould T., Vankoningsloo S., Renard P., Houbion A., Ninane N., Demazy C., Remacle J., Raes M. CREB activation induced by mitochondrial dysfunction is a new signaling pathway that impairs cell proliferation. EMBO J. 2002;21:53–63. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sugimoto Y., Hasumoto K., Namba T., Irie A., Katsuyama M., Negishi M., Kakizuka A., Narumiya S., Ichikawa A. Cloning and expression of a cDNA for mouse prostaglandin F receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:1356–1360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griffin B. W., Magnino P. E., Pang I. H., Sharif N. A. Pharmacological characterization of an FP prostaglandin receptor on rat vascular smooth muscle cells (A7r5) coupled to phosphoinositide turnover and intracellular calcium mobilization. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998;286:411–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li L., Lorenzo P. S., Bogi K., Blumberg P. M., Yuspa S. H. Protein kinase Cδ targets mitochondria, alters mitochondrial membrane potential, and induces apoptosis in normal and neoplastic keratinocytes when overexpressed by an adenoviral vector. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:8547–8558. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.8547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fryer R. M., Wang Y., Hsu A. K., Gross G. J. Essential activation of PKC-δ in opioid-initiated cardioprotection. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2001;280:H1346–H1353. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.3.H1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Majumder P. K., Mishra N. C., Sun X., Bharti A., Kharbanda S., Saxena S., Kufe D. Targeting of protein kinase Cδ to mitochondria in the oxidative stress response. Cell Growth Differ. 2001;12:465–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baines C. P., Zhang J., Wang G. W., Zheng Y. T., Xiu J. X., Cardwell E. M., Bolli R., Ping P. Mitochondrial PKCε and MAPK form signaling modules in the murine heart: enhanced mitochondrial PKCε–MAPK interactions and differential MAPK activation in PKCε-induced cardioprotection. Circ. Res. 2002;90:390–397. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000012702.90501.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsakiridis T., Tsiani E., Lekas P., Bergman A., Cherepanov V., Whiteside C., Downey G. P. Insulin, insulin-like growth factor-I, and platelet-derived growth factor activate extracellular signal-regulated kinase by distinct pathways in muscle cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;288:205–211. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cammarota M., Paratcha G., Bevilaqua L. R., Levi de Stein M., Lopez M., Pellegrino de Iraldi A., Izquierdo I., Medina J. H. Cyclic AMP-responsive element binding protein in brain mitochondria. J. Neurochem. 1999;72:2272–2277. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0722272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.