Abstract

This article analyses the use of mediation to resolve mental capacity law disputes, including those that arise in the healthcare context. It draws on original empirical data, including interviews with lawyers and mediators, and analysis of a mediation scheme, to argue that mediation has the potential to be an effective method of resolution in mental capacity law. It highlights the relationship benefits of mediation while acknowledging the challenges of securing P’s participation and best interests. The final section of the article considers how mediation can operate in one of the most challenging healthcare environments, the Intensive Care Unit. The article emphasizes that the challenges we see in mediation are not unique and exist across the spectrum of Court of Protection practice. Therefore, the article concludes that mediation may be used effectively but the jurisdiction would also benefit from a clearer regulatory framework in which it can operate.

Keywords: best interests, Court of Protection, disputes, mediation, mental capacity, participation

I. INTRODUCTION

Mental capacity law disputes cover issues ranging from property and finances to matters of health and welfare. In each of these areas, we can see disagreements between individuals and public bodies which can reach the Court of Protection (CoP) for resolution. In the medical context in particular, there are a number of high-profile disputes between family members, healthcare professionals and the patient (referred to throughout as ‘P’) regarding best interests under the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA) section 4 which have reached the courts.1 It is concerning that healthcare environments can become a place of such disagreement and entrenchment but it is perhaps unsurprising given the sensitive and emotive issues at stake. However, this challenge strengthens the need for appropriate methods of conflict resolution, which may not always be best achieved through the litigation process.

Mediation, a type of Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR), has been advanced as possibly providing a better way to resolve disputes within the mental capacity jurisdiction.2 Mediation involves an independent third-party helping people in dispute come to a mutually agreed resolution. Mediation has been present throughout human society in many different forms, but since the late twentieth century it emerged as a form of ADR in legal disputes.3 Despite what we suggest is mediation’s potential for avoiding or minimizing conflict and stressful litigation under the MCA, there has been very little published evidence about the use of mediation specifically in mental capacity law.4 While we may be able to draw on the extensive evidence about mediation from other areas, we think it is important to understand how mediation might operate in the specific context of mental capacity law disputes. We know that mediation is taking place in this area, but with little scrutiny compared to the ever-increasing scrutiny placed on the CoP, for example, through the Open Justice Court of Protection project and published research.5 Therefore this article draws on data collected by one of the authors to fill that gap in knowledge and to improve understanding of the benefits of using mediation in this jurisdiction. We draw on a qualitative interview study of mental capacity lawyers and mediators as well as data collected as part of a pilot mediation scheme, to consider the appropriate role of mediation in mental capacity law.

The MCA allows for certain decisions to be made on behalf of an adult who has been found to lack the capacity to make the decision for themselves, provided the decision is made in their best interests.6 The person subject to the MCA proceedings is referred to as ‘P’ and many disputes about mental capacity and best interests will reach the CoP for resolution. Capacity is decision-specific, meaning that each individual decision-making domain is analysed rather than making broad conclusions about a person ‘lacking capacity’ in general terms. For example, a person may be found to lack the capacity to decide about their own medical treatment but may have the capacity to make a decision about where they want to live. It is important, therefore, to look at the specific issue in question and analyse P’s decision-making abilities in that domain. Once a person has been found to lack the mental capacity to make their own decision, a decision can, in some instances,7 be made on their behalf if it is in their best interests.

The difficulty that litigation under the MCA poses can be seen in the first MCA case to reach the Supreme Court, Aintree University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust v James.8 Mr James, a talented musician, developed colon cancer in 2001. This was resected and he was left with a stoma. In 2012 he was admitted to hospital with constipation and while in hospital developed pneumonia, which led to him being intubated and ventilated in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). He improved over the course of a month, but then deteriorated. By the time of the first instance decision, he had experienced several episodes of septic shock, had suffered an asystolic cardiac arrest and had undergone multi-organ support. He lacked the mental capacity to make decisions for himself. The Trust made an application seeking a declaration that it was lawful and in his best interests for life-sustaining treatment to be withheld in the event of a clinical deterioration. At first instance, the judge held that it would not be appropriate to make the declarations sought, but on appeal, this was overturned based on fresh clinical evidence. The Supreme Court ultimately affirmed the decision of both judges because of the additional evidence laid before the Court of Appeal. The nature of the dispute, however, was that his family and the clinicians took a very different interpretation of what quality of life would be in his best interests.

The family recognized that he may not return to the quality of life he enjoyed prior to his illness, but they felt he still gained pleasure from many things such as their visits. Whereas the healthcare professionals believed that the invasive treatments necessary to save his life, such as Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR), would not be in his best interests. The case reinforces the position that best interests assessments are not purely medical assessments and incorporate a wider range of interests, particularly the subjective interests of the patients themselves and what they would perceive to be a worthwhile existence. Yet disputes such as this can arise when relationships between professionals and family break down and they approach the matter from very different vantage points. It is this type of conflict scenario that mediation, if used early and appropriately, might help to address.

In section II we set out the relevant framework governing mediation and mental capacity law, specifically looking at the MCA and the Code of Practice to the MCA, as well as some background to mediation’s use in the health and care context, including the ICU. The ICU can be considered a microcosm of the wider healthcare environment as it takes patients from all areas and disciplines of medicine. We then set out the methods used for the empirical data that we explore in the article, which is followed by an analysis in section three of several key themes that arise from the data in relation to the use of mediation in mental capacity law. These include the role of mediation in improving relationships between the parties; the role of P’s participation in mediation; and the complex issue of ensuring that mediated agreements are in P’s best interests. Finally, section four provides a short case study of mediation in the ICU to illuminate how mediation might operate in one of the most difficult healthcare scenarios.

Overall, we argue that there is evidence to support the view that mediation can help to improve the working relationships of those involved in mental capacity law disputes. However, there are difficulties in securing P’s participation and ensuring that P’s best interests are always met through mediation. As a result of our insights, we recommend that P’s participation, whether direct or indirect, must be a requirement for mediation to be more widely adopted in this area. Furthermore, while the mediator may, in some ways, be better placed than other participants to secure P’s best interests, given the possibility for other participants to be biased in their analysis, placing such an onus on the mediator raises several ethical and legal concerns which undermine this as an appropriate solution to the best interests question. Instead, we argue that transparency and openness of mediated agreements would be beneficial. Despite the difficulties in using mediation in mental capacity law, we argue that mediation may still be used effectively and the many challenges that do arise in mediation often also arise in those cases resolved out of court as well as through the CoP, thereby not being unique to the mediation context.

II. MEDIATION AND THE LACUNA IN MENTAL CAPACITY AND HEALTH LAW

Mediation involves an impartial or ‘neutral’ third-party helping people in dispute come to a mutually agreed resolution or understanding. The parties are not compelled to reach agreement through mediation but are free to do so on their own terms, in a confidential, party-led process,9 and mediation can facilitate parties to a dispute to co-construct the solution in their own terms.10 There is some disagreement about the appropriate role of, and underpinning justification for, mediation’s use in mental capacity law. For example, some commentators have argued that mediation cannot be used in certain types of dispute (such as disputes about capacity itself) and that mental capacity law requires judicial oversight to protect P.11 However, others argue that using mediation can encourage parties to come together through mutual respect to try to resolve communication and relationship breakdown.12 Despite the disagreement about mediation’s role in mental capacity law, we know it is being and has been used to resolve a range of mental capacity law disputes in practice.13

Using mediation to resolve disputes in health and welfare cases is a relatively new development, with issues of vulnerability and power imbalances arguably acting as a barrier to mediation’s earlier uptake. However, evidence about mediation in healthcare is beginning to emerge. For example, NHS Resolution has incorporated mediation into its approach for resolution of clinical negligence disputes with some apparent success14 and other jurisdictions also use mediation in health contexts.15 However, mediation in adversarial tort or contract law-based litigation is quite different in nature from mediation’s use in other types of healthcare dispute, such as those that fall within the MCA framework. This is because mediation in those other areas typically involves compromise around financial matters or matters relevant to the settlement of claims, although apologies and other forms of catharsis may also be important in those disputes too. Whereas in mental capacity law disputes, mediation often seeks to resolve disagreements between family members and professionals about the person’s best interests. Mediation in elder law might be more comparable than mediation in negligence disputes, with Martin outlining that the issues in elder mediation are:16

often interrelated and include family communication, caregiving, living arrangements, asset protection, and inheritance and estate disputes. Disputes occur over guardianship and administration, medical care, driving, financial planning and management, and end-of-life issues.

A significant proportion of mental capacity law disputes will include issues which engage dementia, old age and related issues, and many mental capacity law disputes cross the boundaries of health, care, finances, and estate/end-of-life planning. In disagreements about the provision of health and care to older people or severely unwell patients, which cannot be resolved through an agreement about a sum of money or an apology, a different approach is required that focuses on what is in the best interests of P. Yet one of the concerns in using mediation in mental capacity law is mediation’s association with negotiation and compromise. It is understandable that professionals or family members might have reservations about an approach which entails compromising on P’s best interests. A roundtable on CoP mediation highlighted the difference in approach here between legal professionals and mediators, emphasizing that ‘judicial scrutiny was perceived by some attendees to be necessary to avoid the risk of agreements being enacted that are not in P’s best interests’.17 This is seen to be a particular problem in something like elder mediation where disagreements can reflect familial loyalties and, in some instances, possible financial gain. We return to this issue later in this article, to consider how P’s best interests can be secured through mediation, which is one of the biggest challenges in implementing mediation in this area.

Mediation typically involves the consensual engagement of an independent third party to help people in a participatory process come to a voluntary and mutually agreed resolution and/or understanding of the other party/parties.18 Several key features are central to this conception of mediation. First is the need for the involvement of an independent, neutral third party—the mediator. This is essential because it places the parties on a more equal footing and imports a facilitator into the dynamic rather than allowing domination of one party by the other. Mediator neutrality is more commonly seen in facilitative mediation, in which ‘the mediator is meant to be impartial and has no power to impose a particular outcome on the parties’.19 There are other types of mediation practised, with a range of perspectives as to the appropriate role of the mediator and their degree of intervention in the mediation,20 albeit mediation styles appear more on a continuum rather than having distinct differences. It is said to be critical for the mediator to create a neutral environment in which the parties can be facilitated to be heard on equal terms,21 with recognition that the mediator is not ‘invested’ in the decision, which allows the mediator to probe far deeper in a controlled manner.22 Secondly, is the need for any attempt at mediation, and any agreement reached, to be voluntary and consensual on the part of all parties involved. The voluntary nature of mediation fundamentally distinguishes it from litigation. While mandatory mediation is supported by some theorists and policymakers, it is not a feature of orthodox mediation theory.23

Next, is the aim of resolution and/or understanding of the other party. These are both important because, in some instances, parties may not be able to come to a resolution but the process of better understanding the other party and their position is important and potentially even therapeutic.24 In practice, for example, this allows clinicians to admit to being less certain about outcomes and families acknowledge that the outcome may be different from that which they desire. This movement allows the narrowing of disagreements and, often, resolution. Whatever the outcome from the mediation, the fact that dialogue has occurred, generally means that, at the very least, communication between the parties is maintained or improved, something particularly important in healthcare environments.

Arguably one of the most difficult healthcare contexts in which to implement mediation is the ICU. Over the past 20 years, there has been an increase in the involvement of relatives and patients (where possible) about end-of-life decisions in the ICU.25 However, disagreements are not uncommon,26 although the causes of these disagreements can be multifactorial. A breakdown in communication is one of the driving factors behind disagreements in the ICU.27 On the clinician side, this might be caused by the use of technical terms, euphemisms, statistics, fatigue, sleep deprivation, and cognitive overload, which can lead to poor explanations of the disease process and treatment options available. For example, if multiple patients deteriorate simultaneously, as occurs frequently, then the clinical team will require their focus to be on different patients and conflicting demands. Disagreement may also be the result of healthcare professionals’ unwillingness to look beyond the clinical factors and see the wider values which may be influencing the patient or family perspective. The ability to focus on communication and ensure that clear information is imparted is a core skill, but one that depends a great deal on the communication ability of healthcare professionals. Factors which may contribute to disagreement for family members include fatigue, sleep deprivation, cognitive overload, unfamiliar environment, and loss of control.28 Furthermore, families can underestimate the challenges of the clinical realities of ICU and have unrealistic expectations about what options are available, and the impacts of them.29 The family will understandably be focused on their relative and are unlikely to have the conflicting demands on their time that clinicians will have, although they may of course have other caring responsibilities or pressures. All of these challenges make the ICU a somewhat unique health environment with specific challenges in reaching an agreement about a patient’s best interests. However, it is also an environment where ongoing working relationships and effective communication between family members and healthcare professionals are essential. In most healthcare scenarios, when discussing options with a patient, the healthcare professional and patient can talk about the risks and benefits of a particular treatment before reaching a shared decision on what is the best way forward. This approach does not apply in the same way in cases in the ICU as patients will often be ventilated or minimally conscious and therefore unable to have these direct conversations with healthcare professionals. It is these more severe cases where healthcare professionals need to engage with a patient’s family members on an ongoing basis in which mediation might prove fruitful. In the final section of this article, we return to the ICU to provide an example of how mediation can operate.

There is a wealth of evidence about the effectiveness of mediation as a tool for resolving conflict across many different areas of law, as well as in more practical everyday settings such as workplace disagreements.30 In this sense, mediation’s aim is not to necessarily resolve disputes or reach agreement but, as explained above in relation to ICU, to ‘[reorient] the parties to each other’ and enable them to ‘apprehend the reality of the “other”’.31 It is obvious that this approach could be incredibly valuable in the healthcare context due to the often ongoing nature of the relationship between the parties and the importance of understanding each other to the effective provision of healthcare. However, there is very little evidence about mediation’s use in mental capacity law generally, or healthcare disputes specifically. This may partly be the result of the relative absence of mediation from the mental capacity law framework. Unusually for civil litigation, mediation is not explicitly referred to in the MCA, nor is it referred to in the Court of Protection Rules (COPR), although it is mentioned in Chapter 15 of the MCA Code of Practice. The COPR does include reference to ADR generally, noting that active case management includes ‘encouraging the parties to use an alternative dispute resolution procedure if the court considers that appropriate’.32 This can make it difficult for parties who may wish to mediate a mental capacity dispute, but are unsure of the legalities, or processes, of doing so under the mental capacity law framework. Practice regarding how to deal with mediation during proceedings varies, although the COPR would suggest that any mediated agreement during proceedings would require permission from the court for proceedings to subsequently be withdrawn.33 There is some reference to the use of mediation in the Code of Practice to the MCA, which states34:

A mediator helps people to come to an agreement that is acceptable to all parties. Mediation can help solve a problem at an early stage. It offers a wider range of solutions than the court can—and it may be less stressful for all parties, more cost-effective and quicker. People who come to an agreement through mediation are more likely to keep to it, because they have taken part in decision-making.

While we do not disagree with the above description of mediation, it is important to note that, at the time the Code of Practice was published, there was very little evidence published regarding mediation’s use in this area and so it draws on mediation’s use more widely in the civil and family justice system.35 The one example provided in the Code of Practice of where mediation might be appropriate concerns a dispute about care and residence within a family. Beyond that, the MCA, Code of Practice and COPR provide no legal or procedural guidance regarding mediation’s use to resolve mental capacity law disputes. This is disappointing given that mediation often takes place within the context of the litigation process and in parallel with proceedings.

Mediation is very much situated within the framing of the law here. For example, depending on whether proceedings have been issued or not, litigation may need to be stayed while mediation takes place, mediated agreements may have to be reviewed (and approved) by a judge and parties may choose to mediate alongside the court process. This pattern of mediation shadowing litigation, while not necessary if proceedings have not been issued, does mean that the parties involved in mediation likely require some understanding of the interaction between the mediation and litigation processes, but they so far have very little authoritative guidance on how mediation ought to operate in this context. This gap in the regulatory framework makes it difficult for prospective mediation participants to understand the common challenges that might arise when taking part in a mental capacity law mediation and, furthermore, to understand what the evidence base is for using mediation in their case. This article contributes to that lacuna in evidence and provides important empirical insights into what is happening in practice. However, we also argue that mediation ought to be acknowledged with greater clarity in the substantive and procedural legal frameworks and associated codes of practice and guidance.

III. METHODS

We have carried out analysis of two data sources for this article. The first is an independent evaluation of a practitioner-led mediation scheme for CoP cases (the ‘Scheme’). We provide a summary of the broad findings here, but which are discussed elsewhere in the evaluation report.36 In this article, we focus in more detail on the data from the evaluation that is relevant to the themes analysed, namely participation, working relationships and best interests. The second source of data is 13 interviews with legal and mediation professionals (the ‘Practitioner Interviews’). These data were originally analysed from a procedural justice theoretical perspective, focusing on issues of substantive justice and ways in which procedural justice could be secured through mediation. This analysis has been published elsewhere.37 Secondary analysis of that interview data was carried out for this article, focusing on the three key themes that arise from both datasets to provide an academic insight into mediation’s use in mental capacity law. Both methods are discussed in more detail below. While these data have been discussed elsewhere, the analysis in this article is distinct due to its focus on the three themes of this article (participation, best interests, and relationships) and the specific interrogation of mediation in the healthcare context, which is reinforced by the discussion of the case study in the final section.

The Scheme lasted for 21 months, commencing on 1 October 2019 and ending on 2 July 2021. Spanning the period of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic meant that there were a few challenges in raising awareness of the Scheme and encouraging parties to make use of it. The aim of the Scheme was to provide an evidence base for the use of mediation in the CoP. The Scheme was not a formal court-authorized scheme, but was developed and led by practitioners. Chris Danbury was part of the working group that developed the scheme and Jaime Lindsey was invited to carry out the independent evaluation of it. Funding was provided through the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) Impact Acceleration Account and the University of Essex.

The aim of the Scheme was to provide a framework, rules and documentation that could be used by participants to mediate CoP litigation. It was for issued cases only and offered participants:38

A suitably qualified and experienced mediator to conduct the mediation at a reduced fee of £100.80 per hour (plus travel costs), in line with legal aid rates;

Use of the Scheme process and Scheme documentation;

The opportunity to be a participant in important research.

The Scheme was available for use by parties as they wished, with suggestions given as to the types of cases that might be appropriate for mediation under the Scheme. As set out below, most cases mediated covered property and financial affairs disputes, with no cases covering medical treatment disputes. However, the findings still provide a useful insight into the potential benefits, and weaknesses, of mediation in cases that might arise more generally in the CoP, which include disputes about medical treatment and general health and welfare issues.

The weaknesses of the research include that it was not clear who was a party to the mediated cases, including who attended the mediation itself. A further weakness is that only a small number of cases were mediated under the Scheme (n = 6). This small number is a tiny proportion of cases issued in the CoP each year. However, this is balanced by the high engagement with the research for those who took part in the Scheme, with a response rate to the survey of 63 per cent. Furthermore, this study is one of the first to investigate mediation in this challenging area, making it an important starting point for further investigation. In the full report of the evaluation, which is published elsewhere, the key findings are set out.39 A summary of the mediated cases is set out in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Cases mediated under scheme

| Issue | P’s attendance | Outcome | Format | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediation 1 | Property and finances | None | Agreement reached at mediation | Face to face |

| Mediation 2 |

|

None | Agreement reached at mediation | Virtual |

| Mediation 3 |

|

None |

|

Virtual |

| Mediation 4 | Application to the COP by P’s father and sister for joint and several deputyship for Welfare and for a Statutory Will in relation to P. Dispute about who should be involved in P's welfare and the agreement in the will | None | Agreement reached at mediation | Virtual |

| Mediation 5 | The terms of a statutory will | None | Agreement reached at mediation | Virtual via zoom |

| Mediation 6 |

|

None but mediator had a Zoom call with him and his solicitor before the mediation |

|

Virtual |

As outlined above, the second source of data is an interview study of 13 professionals who had experience of the use of mediation in mental capacity law. This was funded through a grant from the Socio-Legal Studies Association. Each interview lasted up to around 60 minutes and the format was semi-structured. Participants were identified using purposive and snowball sampling. These data have been re-analysed for the development of this article, with thematic inductive analysis focusing on the use of mediation generally in mental capacity law but also specifically in healthcare contexts, something which emerged explicitly in discussion in several interviews as well as implicit discussion in others.

IV. FINDINGS: RELATIONSHIPS, BEST INTERESTS, AND PARTICIPATION

In the sections below, we consider three central themes that arise from the data collected. We look at the evidence for mediation’s role in improving the relationship between the parties, the question of who ensures P’s best interests are met in mediation, and P’s participation in mediation. We contend that there is some positive evidence regarding the impact of mediation on the working relationships of the parties but securing P’s best interests and participation pose the greater challenges. Despite this, we emphasize that the question of securing P’s participation and best interests is a problem throughout mental capacity law, including in CoP proceedings, and therefore they are not challenges exclusive to mediation. Any expansion of mediation requires giving careful thought to these issues, but they must also be set in the context of mental capacity law as it currently, and imperfectly, operates.

A. Mediation’s potential in improving relationships

There is an ongoing discussion in the literature regarding the impact that mediation can have on the relationships between individuals involved.40 This goes beyond mediation used in litigation, with mediation being used in other settings as a better form of conflict resolution such as in resolving disputes between colleagues at work.41 The literature supports a view that mediation can help to improve the relationship between parties to a dispute, albeit the evidence is less clear as to how mediation has such an impact and what factors influence a positive impact on relationships. For example, Pruitt et al.’s study of community mediation shows, through quantitative analysis, that ‘joint problem solving contributes to improved relations’.42 However, Pincock’s qualitative study suggests that:43

in a small number of cases, mediation does have positive lasting effects on participants’ efficacy, interests, and relationships. While these cases suggest that mediation has the potential to build participant capacity, these effects are often more limited in scope and less directly linked to the mediation process than ideal expectations suggest.

The consensus across the broad spectrum of mediation literature is that mediation can have a positive and lasting impact on relationships between the parties, but that does not mean it inevitably will. In particular, the quality of the mediation process and the nature and extent of deterioration in the participants’ relationship before mediation are important factors.44 We agree, though, that a core aim of mediation, and one of its fundamental appeals, is in the relationship building potential it can provide. This is particularly valuable in health and care cases due to the ongoing nature of the relationships between P, professionals, and family members. Relationships can be undermined by adversarial litigation, which can enhance, rather than reduce, conflict. While many would argue that the CoP is meant to be an inquisitorial, rather than adversarial jurisdiction, this does not always translate into the realities of CoP practice.45 Therefore any process which can help to support positive relationships to be maintained beyond CoP proceedings ought to be encouraged.

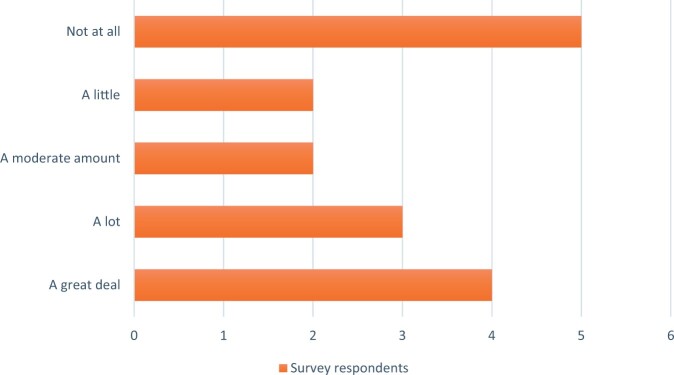

Turning, then, to the evidence about relationship improvement in mental capacity mediation, the evidence from the Scheme indicates that participants felt that taking part in the mediation did have a positive impact on their working relationships with other parties. As Figure 1 below shows, 68.75 per cent (n = 11) of survey respondents indicated some degree of improvement in their working relationship with the other parties. As Johal and Danbury have written, ‘The overarching premise of mediation is to reunite the two conflicting parties, with each party advocating their own interests, before reaching a mutually agreeable decision about P.’46 In this sense therefore, it is unsurprising that survey respondents did experience such an improvement in relationships. However, 5 of 16 respondents answered ‘not at all’ to the question ‘did mediation improve your working relationship with the other parties?’ suggests that the improvement is not felt universally, something supported by the wider mediation literature.

Figure 1.

Responses to Question 26—Did the mediation improve your working relationship with the other parties?

The Scheme itself did not, however, track the baseline relationship between parties, nor was it possible to follow through to a medium to long-term analysis of the impact on relationships. However, free text comments also supported the relationship benefits of mediation under the Scheme. For example, one response to the question of which issues are most appropriate for mediation was:

when you have two parties who[se] relationship has totally broken down, the formal framework of mediation offers a way to understand the views of the other party without the adversarial atmosphere of a court.

The evidence from the Practitioner Interviews overwhelmingly indicated that mediation had benefits for the working relationships of the parties contrasted with litigation.47 This benefit was noted, without prompting, by all participants in each interview, albeit to varying degrees. A typical response was given by Vanessa, who explained that the reason she got involved with mediation was because ‘in Court of Protection, often, you find that court proceedings can make relationships a lot worse’. Jacinta said:

I’ve never been involved with a court hearing—and I’ve been involved with quite a lot of court hearings … I’ve never been in a court hearing where at the end they’ve flung their arms around each other and held each other and cried, because they’re so relieved that it’s all done.

Her experience was that mediation had the real potential to create positive experiences and outcomes for those involved, in stark contrast to her experience of court hearings. The reason for this, Jacinta indicated, was that ‘often the problems are not resolved, because things aren’t explained properly in court hearings’. The value of mediation’s benefit to relationships, then, can emerge from the ability to develop real communication, over a period of time, to get individuals to think, reflect, and understand each other’s perspective on the issues.

These benefits were noted by experienced professionals, all of whom had experience of litigation and/or mediation in mental capacity law disputes. Furthermore, the value to mediation was particularly noted where working relationships needed to continue. Isla explained:

One of the difficult things with CoP mediations … one of the biggest challenges is family dynamics … the healing of relationships within families surrounding P, may be rare, in terms of P’s psychological welfare, I think more could be done.

She went on to say:

The issues before the court aren’t repairing the relationship with the parties for the benefit of P. if there was a psychological report that said how detrimental it was, then maybe the court could … encourage the parties to mediate to improve their relationship for the benefit of P.

These benefits are not just perceived in relation to family dynamics but also in relation to professional relationships with family. Alastair said ‘for medical treatment, it’s all about trust and relationships’. He went on to discuss one of his client hospitals who put effort ‘into relationships and communication and informal dispute resolution’ between family and healthcare professionals, highlighting that going to court is not always necessary if informal measures such as mediation can be used to improve relationships and communication between those involved in these difficult cases. He went on to explain that he had previously taken part in telephone mediation in the area of lasting Powers of Attorney disputes and he thought ‘it’s just not going to be as effective, because it’s [mediation] all about building relationships’. However, he was surprised to find out that those mediations ‘all had good results’.

What these data indicate is that professionals with experience of mediation in mental capacity law perceive there to be a benefit of the use of mediation over litigation in relation to the impact on the working relationships of the parties involved. If mediation can improve relationships, which the data appears to suggest, then it would seem essential to mediate before the case reaches a court hearing (or at least a final hearing, if indeed a court hearing is necessary other than to approve any mediated agreement). This is particularly important in health and social care contexts given the ongoing relationship between family members and professionals. It is important in that scenario that mediation takes place before relationships have deteriorated beyond a point of no return. The need for early mediation is reflected in one of the only published studies about CoP mediation by Charlotte May, who found that 76 per cent of respondents agreed that mediation should be carried out at an early stage with 32 per cent believing it should take place before proceedings.48 The literature similarly indicates the benefits of this, before parties become entrenched in their positions and then find it difficult to view the dispute beyond the confines of their own perceptions of it.49 With the advent of social media and the high profile nature of some cases, this entrenchment is likely to be harder to engage with, once significant publicity has occurred, which can happen with CoP proceedings. Overall, then, mediation does appear to provide relational benefits for at least some participants in mental capacity law disputes, albeit the data is mostly from mediators and lawyers rather than other parties. Further evidence is needed to establish the specific factors which make mediation positively (or negatively) impact relationships which would better enable us to understand which cases are most appropriate for mediation to ensure effective ‘funnelling’ into mediation at an early stage of the dispute.

B. Securing best interests

The requirement under the MCA that actions carried out must be in P’s best interests poses a real challenge for mediation—in the absence of a judicial figure who ought to oversee that P’s best interests are met? Ought it be the mediator who secures this? If it is not the mediator, then who involved in the dispute will be able to effectively oversee whether P’s best interests are secured? These questions articulate some of the central difficulties in mediating CoP cases. This was a concern that was identified in the single case study that was observed for the Scheme, with the report stating:50

To some extent, this mediation felt like a more typical commercial mediation, rather than a CoP mediation, with a strong focus on compromise, costs, and settlement. This was surprising as the driving factor expected in advance was the best interests of P.

Any understanding of the MCA makes it evident that any agreement about P at mediation must be in P’s best interests. Yet if best interests does not appear to be the driving factor behind the agreement, then mediation risks prioritizing the interests of the parties who attend, rather than P. In the Practitioner Interviews, Alastair articulated this risk well, in saying ‘it was the risk of unlawful consensus, so mediation can be great for reaching consensus, but the consensus is not necessarily lawful [if not in P’s best interests]’. If mediation is used to try to achieve compromise between the parties, as it appears to be in other areas, then there is a real risk that compromise undermines P’s best interests. This issue is, of course, most stark in life-or-death cases, which are often the most high profile in the healthcare context, but it can also arise across the board in mental capacity law such as in disputes about the care and finances of elderly relatives.

In the healthcare context, reaching a mediation agreement requires understanding what health and care is in P’s best interests, but also requires a solid grasp of what treatment is available and/or on offer to P by the professionals. Family members of P, or an incapacitated P herself, may have a view on what treatment they think is best but if healthcare professionals are not willing to provide it, then that question becomes difficult. The issue was dealt with in the Scheme guidance through the following statement:51

As disputes in the COP involve the best interests of P, the mediator must ensure first that P can participate appropriately in the mediation, and secondly given that any agreement reached will be subject to consideration by the COP that (i) the agreement reached is in respect of issues on which P lacks capacity and (ii) that the parties have applied the section 4 MCA best interests test when agreeing what is in P’s best interests.

Regardless, we question whether it is appropriate to place the obligation in respect of best interests52 on the mediator, particularly given their professional role as independent and impartial. Facilitative mediation theory says that the role of a mediator is to facilitate the parties themselves to resolve the dispute themselves, it does not permit mediators to take an active or substantive role in relation to the agreement itself.53 Other mediation styles do permit the mediator to take a more active role in the dispute, but these have also been subject to criticism and are also not generally encouraged or practised in civil and family contexts in England and Wales.54

While it could be argued that there is value in being creative with mediation in different areas of law, requiring the mediator to ensure that the best interests tests are met is a radical reframing of their role which, in our view, undermines their impartial stance. The role of the mediator is to empower the process of resolution. If the mediator is perceived by any of the parties as being associated with a particular outcome, then this will likely hinder the ability to be accepted by all the parties involved. The ideal mediator should be impartial to the position of each of the parties. Being impartial allows the mediator to challenge preconceived ideas in a safe and fair way. The mediator’s role is, in part, to encourage the small steps that occur to be built upon to reach consensus. It is imperative to remember P is central to this process, and, the mediator can use questions to encourage the parties to consider what P’s view would be and why. This continued reframing, by the mediator, to put P at the centre is of paramount importance while also enabling them to maintain an impartial stance in respect of the parties themselves. This gives the mediator a central role in facilitating the parties to reach an agreement in P’s best interests, without placing an evaluative role on the mediator to weigh up the substance of the agreement reached.

If the mediator is not the person to secure best interests in that substantive sense, then we must consider how P’s best interests can be guaranteed to be met here. In the Scheme report, it was recommended that the obligation to secure best interests is on the parties, not the mediator. We agree with this approach in general terms for the development of mediation in mental capacity law. However, this requires further consideration regarding its operationalization in different types of cases. For example, how can parties, who are likely to be entrenched in their thinking, all be sure that their positions are in the best interests of P? Placing an obligation on the parties to act in P’s best interests risks changing little in practice, given that most of those involved professionally will already be under such an obligation. The reality, then, is that judicial oversight is the backdrop to securing best interests. This may well be best achieved through a clearer and more robust regulatory framework of mediation in this jurisdiction, which incorporates reporting and transparency requirements regarding mediated agreements to facilitate public scrutiny and to avoid the criticism of agreements not being in P’s best interests.

C. Achieving participation

Participation is an important topic in the context of mental capacity law, with various scholars engaging in discussion of what participation means and why it is important.55 Typically participation means being involved in the case in some way, beyond that, there is little agreement about what participation should look like in mental capacity law with scholars and practitioners taking different perspectives. For example, participation can be substantive in nature through various sub-concepts such as giving voice or personal presence.56 Disability scholars might also remind us of the ‘nothing about us without us’57 concept and therefore participation is an absolute pre-requisite to decision-making in this jurisdiction. Others focus more strongly on representation of P through lawyers or advocates, rather than requiring more direct forms of participation. Representation, as a form of participation, requires P to be a party to proceedings (or a party to the mediation), otherwise they would not have a right to have representation. However, being a party to proceedings is not an absolute requirement in this jurisdiction.58 Furthermore, as others have noted, even if P is a party, there is no requirement for their representatives to directly represent their own views,59 instead, being required to act in their best interests, albeit that does include considering the person’s wishes and feelings.60 Given the possibility that P will not be a party to the case that is mediated and, moreover, that even where P is a party they may not have their views directly reflected (or argued for) in the mediation, the role of P’s direct participation is even more important. Several ethical issues arise regarding whose voice is heard in mediation.61 Johal and Danbury state ‘it is important that the mediator has independent access to P, to ensure that P’s voice is heard during the mediation process; although this is invariably more challenging if P is, for example, sedated’.62 It is those cases where securing P’s participation is difficult, that require careful consideration to understand precisely what participation in mediation would mean.

The Scheme data showed that P’s participation in the six mediations studied was very limited. This is even though it was a key requirement of the Scheme that the mediator must ‘ensure first that P can participate appropriately in the mediation’.63 As noted in the Scheme report:64

in one mediation the mediator reported that she had a Zoom call with P and his solicitor before the mediation, suggesting that he participated indirectly in advance.

Securing (indirect) participation of P in only one mediation out of six is concerning. While there is no comprehensive or statistically reliable data on P’s participation in CoP hearings, the data we do have suggests a comparable or slightly better degree of participation.65 The report further states:66

Various reasons were given for P’s lack of participation by those who indicated that P did not participate, including that: P was unwell (n = 3), P was not invited (n = 2), and P did not wish to participate (n = 1). However, in the majority of cases, P’s lack of participation was attributed to a lack of capacity. This ignores the possibility for Ps to lack capacity in respect of the subject matter of the case but retain capacity to engage in mediation. Furthermore, two respondents expressly stated that P lacked the capacity to “express … views, wishes, or feelings”, whereas even incapacitated Ps should be provided with an opportunity to have the best interpretation of their wishes and feelings ascertained.

The reasons for P’s limited participation in mediation were explicitly explored with interviewees too. A common theme that emerged was that participation of P would be raised by one party or another, but then not pursued or prioritized. As noted elsewhere, in only four of the 13 Practitioner Interviews was there evidence of direct participation by P and in most examples given by interviewees, P did not attend the mediation.67 It could be argued that P participated indirectly in other ways. Typically, the study showed that perceptions of indirect participation were either through legal representation (usually by the Official Solicitor) or through having their wishes and feelings discussed or read to the participants.68 Isla explained a mediation she was involved in which concerned a dispute between two sisters about their mother’s care and living arrangements, with a DOLS order in place. Isla said:

… in terms of P’s views, this was a case which I felt where P was well represented … Firstly, she was represented by the official solicitor. And also, there had been specific conversations … because she’d been saying that she wanted to go back to live with her daughter. So I thought her voice was very much heard.

It is interesting to consider whether legal representation is sufficient as a form of participation when, as noted above, the Official Solicitor, or Litigation Friend, does not have to directly represent P’s views.69 It is reasonable to consider legal representation as a form of indirect participation where the representative puts forward their client’s wishes. However, where the representative is not required to do so, this is not a satisfactory account of participation, even on the thinnest interpretation of the concept. In that scenario, firstly P is reliant on the representative coming to the same conclusion on best interests as P’s wishes and, secondly, even if the representative reaches the same conclusion, it may be for different reasons and does not require putting forward P’s own account. In relation to the second form of indirect participation, conveying P’s wishes to the mediation, this appears to resemble a participatory approach more closely, albeit more weaky than having P as a direct and active participant. If this form of participation is to be used as a justification for mediation securing participation in mental capacity law then it requires clear parameters regarding how P’s wishes and feelings are established and requirements for how those views are put to the mediation. For example, through specific wording articulated to all parties. Furthermore, the timing of the statement and repetition of P’s views during the mediation requires careful consideration to ensure it is a central feature of the mediation process.

Comparing mediation with litigation, some interviewees noted the wider approach adopted by the courts in recent years, with judges seeking to meet P even where he or she is very unwell in hospital. For example, Alastair said:

There’s been a very clear trend in the case law over the last four, five years of judges listening to P much more … in the medical treatment cases in particular, you do see in the judgment now … ‘I went to the bedside and I talked to Bob about how we felt about his amputation, and he told me, you know, he looked me in the eyes and said, “I’d rather die with two legs than live with one, and, you know, this is how I feel”

While the evidentiary value of this sort of approach has since been questioned by the Court of Appeal,70 whether such an approach is possible in mediation is questionable. For example, who is the appropriate individual to have this discussion with P? While there is value in the mediator meeting P, there is a risk in permitting the mediator to adopt a sort of quasi-judicial role.71 Conversely, given that the mediator does not have to make a final determination on the issues, the evidential question present when a judge meets P fall away when a mediator does. In this sense, permitting or even encouraging the mediator to meet with P before a mediation and then conveying P’s wishes and feelings during the mediation may have an intuitive appeal in some cases. Yet it can be challenging to secure P’s participation in healthcare contexts, even if the mediator were to be empowered to meet with P. For example, a ventilated patient in ICU cannot be moved out of a hospital environment, however, mediation is best carried out in a neutral place. Instead, gathering evidence of what P was like prior to their illness is likely to be key, to identify what P’s wishes and feelings would have been based on a range of evidence about his or her life.

The evidence indicates that mental capacity mediations have a long way to go in securing the effective participation of P. We suggest that participation through legal representation is not enough and further consideration by the parties is needed to ensure P either attends the mediation or participants indirectly through having their wishes and feelings clearly put to the participants during the mediation process. There are clear challenges of securing P’s participation in this jurisdiction, but it is evident that these are not unique to mediation. Participation in CoP cases has been sporadic and we think mediation ought not to be viewed differently from the wider issue of participation of P across mental capacity law disputes, meaning that securing P’s party status and direct representation of their views before the mediation is key.

V. MEDIATION IN THE INTENSIVE CARE UNIT

We conclude this article by setting out a short case study exploring how mediation might be used in one of the most challenging healthcare contexts that arise under mental capacity law’s jurisdiction—adult patients in the ICU. We use this example in light of our discussion above to show how mediation might be a useful tool in resolving disputes between healthcare professionals and family members without resorting to the courts. We do this by drawing on one of the author’s experiences as a mediator of serious medical treatment disputes to illustrate the type of case that mediation might be effective for. We acknowledge that empirical evidence regarding mediation’s use in every aspect of mental capacity law’s jurisdiction would be beneficial, however, in the absence of that direct evidence, it is useful for readers to have mediation ‘brought to life’ through a vignette from practice.

A. The case study

In this case study, we consider a scenario where P attended hospital with symptoms and signs of a chest infection. Due to the severity of the infection, P was admitted to hospital and appropriate therapy commenced. Unfortunately, the initial treatment did not work and P deteriorated, subsequently being admitted to ICU, where they were intubated and ventilated. The combination of the underlying disease and the treatments given to P resulted in their blood pressure becoming very low, as well as their kidneys and other organs failing. Vasopressor drugs were started to help increase the blood pressure, renal replacement therapy commenced and P’s condition stabilized. P improved slowly from the multi-organ failure, with one exception—their lungs did not improve. As the days pass into weeks, the treating team started to initiate conversations with P’s partner and family about limitations of life-sustaining treatment and also withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment. The family provided suggestions of possible treatments that they had researched. The treating team became upset that their expert opinion was being challenged by this approach whereas the family feel they were merely trying to fight for their loved one. After some further weeks, positions became entrenched, lawyers instructed and legal proceedings were threatened. At this point, one of the lawyers suggests mediation, which is agreed and the mediation process begins at this point. P cannot be directly involved in the mediation as they are heavily sedated to allow them to be safely ventilated. However, their views are ascertained through the mediator speaking to close family members and considering whether any written or oral evidence exists as to P’s wishes and feelings, which can be discussed at the mediation. In this scenario, the mediation would be expected to progress over a number of weeks with various conversations between the mediator and the parties via video conferencing. Each interaction would be allowed to progress at its own pace and duration. In general, there would be at least one meeting between mediator and one of the parties per day, but multiple events occur on some days. The process allows the emotional overlay of the parties to settle and for them to reappraise their purpose.

Once refocused on P and their best interests, the value of mediation in this case study is in the family and the treating team being able to move from their initial entrenched position and gradually agree on an action plan, which would subsequently be put into place for P. After this point, if the parties wish then the mediator can continue to be involved to help resolve any misunderstandings that might occur. The mediation in this example can be seen as a transformative process in two key ways. Firstly, it can enable the family, treating team and P to improve their relationship during and following the mediation, a key benefit identified in the empirical research discussed earlier. This highlights the impact that mediation can have on a range of individuals who take part in it, even in a case such as this where the outcome may not necessarily be positive for all, particularly family members if P does not ultimately survive. If we see mediation as a contextualized process, the difference that mediation can make in this example is in giving the parties the time and space to step back from the trauma of this type of dispute and reflect, in a safe and independent environment, on what is best for P, rather than remaining in their entrenched positions. Secondly, mediation can provide real communication and participation benefits that having an independent third party, the mediator, to assist with discussion and process on an ongoing basis can provide. It can be challenging to effectively communicate when going through emotional distress and even more so in a litigation process over which the parties have little control. Having a close family member in ICU is one of the most challenging circumstances that a person can face, yet health and care needs change daily and regular communication about P’s condition is essential to ensure their needs are met and that family members remain informed about P’s prognosis. Furthermore, family members may have important observations about P’s presentation if they are regularly in attendance, which can be more effectively communicated through a mediation process than the formality of court proceedings. Therefore the ongoing role of mediator as facilitator here is essential and helps to transform the communicative aspect of the relationship.

While this is only one example of the type of case that can be mediated in the challenging environment of mental capacity law, we argue that the ICU case study represents a paradigmatic example of how mediation can be useful to resolve even the most traumatic disagreements about healthcare. We agree that ‘mediation cannot transform all people’,72 but the example does reflect the potential of mediation in instances where the parties are willing to engage with the process. Ultimately the parties still retain the option of issuing court proceedings if any concerns remain regarding the best interests of the patient following a mediated agreement, but the possibility of a more participatory and relationship-preserving approach to these healthcare disputes are two important advantages of mediation over litigation.

VI. CONCLUSION

This article has presented original empirical data on the use of mediation in mental capacity law disputes, filling a gap in the literature regarding mediation and the MCA, while also grappling with some of the more challenging questions about mediation’s use in healthcare cases specifically. The evidence that we draw on suggests that there are several issues which require careful interrogation regarding mediation’s use, most importantly there is a need to effectively secure P’s participation and to consider more creative ways through which P might be able to give voice. Some of these issues are highlighted through the case study of mediation in the ICU. Furthermore, while there is evidence of positive effects of mediation in these cases, such as an improvement in working relationships, we suggest that further evidence is needed to consider the reasons why mediation improves relationships, the extent to which it does, and the reasons why sometimes it fails to achieve this aim. In relation to the best interests question, which is central to resolution of disagreements under the MCA, we must consider how mediation agreements can be agreed in the best interests of P rather than permitting the interests of others to override. We have analysed the role of the mediator in this regard, albeit requiring the mediator to ensure best interests are secured may undermine their neutral role. Despite some of the challenges mediation poses in the mental capacity sphere, we note throughout that many of these challenges also arise in CoP litigation, thereby supporting a view that the problem is not one caused by mediation. However, this also suggests that these problems are unlikely to be solved through mediation and, arguably, wider cultural change is required within mental capacity law practice which would then filter through to mediation practice too. We have suggested some possible ways forward to resolve the challenges that mediating mental capacity law disputes can create, but further guidance, both judicial, legal and ethical, would also assist in clarifying several of these points. In the absence of such guidance, mental capacity mediation will continue in the background, somewhat under the radar, meaning that we may be missing an opportunity to regulate, or provide oversight of, what is happening on the ground.

Footnotes

Aintree University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust v James [2013] UKSC 67; North West London CCG V GU [2021] EWCOP 59. There are also many in the children context, which have been more high profile and, while the legal framework is different, often raise similar issues, see Great Ormond Street Hospital v Charles Gard [2017] EWHC 972; Barts NHS Health Trust v (1) Hollie Dance (2) Paul Battersbee and (3) Archie Battersbee [2022] EWHC 1435.

eg by practitioners who set up the Practitioner Led Court of Protection Mediation Scheme, further information available at: <https://www.mentalcapacitylawandpolicy.org.uk/court-of-protection-mediation-scheme/#:˜:text=The%20aim%20of%20mediating%20a , proceed%20to%20a%20contested%20trial> accessed 3 April 2024.

CJ Menkel-Meadow (ed), Mediation: Theory, Policy and Practice (Routledge 2018).

For the limited evidence that there is, see Charlotte May, ‘Court of Protection Mediation Research: Where are We in the UK?’ (2019) <http://www.adultcaremediation.co.uk/Court_of_Protection_Mediation_Research_190531.pdf> accessed 5 April 2024; J Lindsey, Reimagining the Court of Protection: Access to Justice in Mental Capacity Law (CUP 2022); J Lindsey and G Loomes-Quinn, ‘An Evaluation of Mediation in the Court of Protection’ (University of Essex, 2022) <https://repository.essex.ac.uk/33465/> accessed 5 April 2024.

Open Justice Court of Protection, <https://openjusticecourtofprotection.org> accessed 28 May 2024.

MCA, s 4.

Due to the operation of MCA, s 27, not all decisions can be substituted. eg consent to sexual relations is excluded from the best interests decision-making framework.

[2013] UKSC 67. Mr James died before the Court of Appeal judgment and Supreme Court hearing. One of the authors, Dr Chris Danbury, was an expert witness in these proceedings.

CJ Menkel-Meadow, Mediation, Arbitration, and Alternative Dispute Resolution (Elsevier Ltd 2015); Menkel-Meadow, Mediation: Theory, Policy and Practice (n 3).

ibid.

J Lindsey, ‘The Role of Mediation in the Court of Protection: A Roundtable Report’ (University of Essex 2020) <https://repository.essex.ac.uk/28658/1/Mediation%20roundtable%20report_2020.pdf> accessed 5 April 2024.

See May (n 4); LL Fuller, ‘“Mediation—Its Forms and Functions”, Southern California Law Review 44, pp. 305-39’ in C Menkel-Meadow (ed), Mediation: Theory, Policy and Practice (Routledge 1971).

(n 4).

See <https://resolution.nhs.uk/2020/02/12/mediation-in-healthcare-claims-an-evaluation/#:˜:text=Mediation%20is%20proven%20to%20be , a%20patient%20and%20their%20family> accessed 2 February 2024; Analyses of mediation in medical negligence litigation also supports its potential, see DH Sohn and B Sonny Bal ‘Medical Malpractice Reform: The Role of Alternative Dispute Resolution’ (2012) 470 Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® 1370.

eg China uses it in relation to medical disputes: M Wang and others, ‘The Role of Mediation in Solving Medical Disputes in China’ (2020) 20 BMC Health Service Research 225; see also discussion in I Izarova and V Vėbraitė, ‘Towards Effective Medical Disputes Resolution in Ukraine and Lithuania: Comparing Analyses, Challenges and Perspectives’ in R Maydanyk, A den Exter and I Izarova (eds), Ukrainian Healthcare Law in the Context of European and International Law (Springer International Publishing 2022) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-05690-1_9.

J Martin, ‘A Strengths Approach to Elder Mediation’ (2015) 32 Conflict Resolution Quarterly 481, 482.

Lindsey (n 11) 15.

This definition is drawn from a range of literature but which is summarized well in Menkel-Meadow, Mediation: Theory, Policy and Practice (n 3) xxix.

Lindsey (n 4) 100.

The different types of mediator styles and practices are beyond the scope of this article, as we focus on facilitative mediation as the dominant form. For further discussion see L Riskin, ‘Understanding Mediators’ Orientations, Strategies, and Techniques: A Grid for the Perplexed’ (1996) 1 Harvard Negotiation Law Review 7; Menkel-Meadow (n 3); R Blakey, ‘Cracking the Code: The Role of Mediators and Flexibility Post-LASPO’ (2020) 53 Child and Family Law Quarterly.

V Bondy and others, Mediation and Judicial Review: An Empirical Research Study (Nuffield Foundation 2009); D De Girolamo, ‘The Mediation Process: Challenges to Neutrality and the Delivery of Procedural Justice’ (2019) 39 Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 834; R Blakey, ‘“Mediators Mediating Themselves”: Tensions Within the Family Mediator Profession’ (2022) Legal Studies 1.

Blakey, ibid.

Bondy and others (n 21). See also government plans to introduce mandatory mediation for small claims cases <https://www.gov.uk/government/news/government-reveals-plans-to-divert-thousands-of-civil-legal-disputes-away-from-court> accessed 28 May 2024.

RA Baruch Bush and JP Folger, ‘Changing People, Not Just Situations: A Transformative View of Conflict and Mediation’ (1994) in Menkel-Meadow (n 3); H Pincock, ‘Does Mediation Make Us Better? Exploring the Capacity-building Potential of Community Mediation’ (2013) 31 Conflict Resolution Quarterly.

CS Hartog and others, ‘Changes in Communication of End-of-Life Decisions in European ICUs from 1999 to 2016 (Ethicus-2) - a Prospective Observational Study’ (2022) 68 Journal of Critical Care 68, 83.

E Azoulay and others, ‘Prevalence and Factors of Intensive Care Unit Conflicts: The Conflicus Study’ (2009) 180 American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 9, 853.

See ibid; K Knickle, N McNaughton and J Downar, ‘Beyond Winning: Mediation, Conflict Resolution, and Non-rational Sources of Conflict in the ICU’ (2012) 16 Critical Care 308.

ibid.

(n 26).

L Barry, ‘Elder Mediation: What’s in a Name?’ (2015) 32 Conflict Resolution Quarterly 435; L Forbat and others ‘Conflict in a Paediatric Hospital: A Prospective Mixed-Method Study’ (2016) 101 Archives of Disease in Childhood 23; T Tallodi, How Parties Experience Mediation: An Interview Study on Relationship Changes in Workplace Mediation (Springer 2019); C Irvine, ‘What Do “Lay” People Know About Justice? An Empirical Enquiry’ (2020) 16 International Journal of Law in Context 146; Wang and others, (n 15) 225; Blakey (n 21).

Menkel-Meadow, Mediation: Theory, Policy and Practice (n 3) xxi.

COPR rule 1.3(3)(h).

COPR rule 13.2; see also Lindsey and Loomes-Quinn (n 4) 56–57.

para 15.7.

Mediation is more established in family law, where parties in private family law proceedings are required to engage in a Mediation Information and Assessment Meeting (MIAM), s 10(1) Children and Families Act 2014. Attendance is not required in all cases, see <https://apply-to-court-about-child-arrangements.service.justice.gov.uk/about/miam_exemptions> accessed 28 May 2024. This area of practice could certainly draw on the existing evidence and framework in family law see recommendations, see Lindsey and Loomes-Quinn (n 4).

See Lindsey and Loomes-Quinn (n 4).

Lindsey (n 4).

<https://www.courtofprotectionmediation.uk/> accessed July 2021.

Lindsey and Loomes-Quinn (n 4).

DG Pruitt and others, ‘Long-Term Success in Mediation’ (1993) 17 Law and Human Behavior 313; RA Peeples, S Reynolds and CT Harris, ‘It’s the Conflict, Stupid: An Empirical Study of Factors that Inhibit Successful Mediation in High-Conflict Custody Cases’ (2008) 43 Wake Forest Law Review 505; Pincock (n 24); Menkel-Meadow (n 3).

Tallodi (n 30).

Pruitt and others (n 40) 327.

Pincock (n 24) 5.

Pruitt and others (n 40); D Wilkinson, S Barclay and J Savulescu ‘Disagreement, Mediation, Arbitration: Resolving Disputes About Medical Treatment’ (2018) 391 The Lancet 2302.

Lindsey (n 4) 40, 143.

HK Johal and C Danbury, ‘Conflict Before the Courtroom: Challenging Cognitive Biases in Critical Decision-Making’ (2021) 47 Journal of Medical Ethics 36, 4.

See Lindsey (n 4) 141–46.

May (n 4) 13.

ibid; Bondy and others (n 21) 28.

Lindsey and Loomes-Quinn (n 4) 50.

para 7, p 3, scheme guide <https://www.courtofprotectionmediation.uk/> accessed July 2021.

In our view there is also an issue here with regard to the obligation relating to capacity but this is explored in more detail in the report, see Lindsey and Loomes-Quinn (n 4).

J Martin, ‘A Strengths Approach to Elder Mediation’ (2015) 32 Conflict Resolution Quarterly 481; Blakey (n 21).

Despite criticism from some about this rigidity, see Blakey (n 21).

C Kong, Mental Capacity in Relationship: Decision-Making, Dialogue, and Autonomy (CUP 2017); L Series, P Fennell and J Doughty, The Participation of P in Welfare Cases in the Court of Protection (Cardiff 2017); J Lindsey, ‘Testimonial Injustice and Vulnerability: A Qualitative Analysis of Participation in the Court of Protection’ (2019) 28 Social & Legal Studies 450; Camillia Kong and others, ‘The “Human Element” in the Social Space of the Courtroom: Framing and Shaping the Deliberative Process in Mental Capacity Law’ (2022) Legal Studies 1; Lindsey (n 4).

Series, Fennell and Doughty, ibid; Lindsey (n 4).

JI Charlton, Nothing About Us Without Us Disability Oppression and Empowerment (University of California Press 1998).

See eg Practice Direction 2A COPR.

AR Keene, P Bartlett and N Allen, ‘Litigation Friends or Foes? Representation of “P” before the Court of Protection’ (2016) 24 Medical Law Review 333.

MCA s 4.

Peeples, Reynolds and Harris (n 40); Pincock (n 24); M Doyle, A Place at the Table: A Report on Young People’s Participation in Resolving Disputes about Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (2019) <www.repository.essex.ac.uk/24546/1/A%20Place%20at%20the%20Table%20final%20/report%20March%202019.pdf> accessed 5 April 2024; V Bondy and M Doyle, Mediation in Judicial Review: A Practical Handbook for Lawyers (London 2011).

Johal and Danbury (n 46) 4.

para 7; Lindsey and Loomes-Quinn (n 4).

Lindsey and Loomes-Quinn (n 4) 35.

Series, Fennell and Doughty (n 55); P Case, ‘When the Judge Met P: The Rules of Engagement in the Court of Protection and the Parallel Universe of Children Meeting Judges in the Family Court’ (2019) 39 Legal Studies 302; Lindsey (n 55); AR Keene and others, ‘Taking Capacity Seriously? Ten Years of Mental Capacity Disputes Before England’s Court of Protection’ (2019) 62 International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 56.

Lindsey and Loomes-Quinn (n 4) 36.

Lindsey (n 4) 131.

This is also reinforced in a survey carried out of mental capacity law practitioners, see ibid, 133.

AR Keene, P Bartlett and N Allen, ‘Litigation Friends or Foes? Representation of “P” before the Court of Protection’ (2016) 24 Medical Law Review 333; Lindsey (n 4) 183–84.

In Re AH (Serious Medical Treatment) [2021] EWCA Civ 1768.

Lindsey (n 4) 125–30.

C Menkel-Meadow, ‘The Many Ways of Mediation: The Transformation of Traditions, Ideologies, Paradigms, and Practices’ (1995) 11 Negotiation Journal 217, 240.

Contributor Information

Jaime Lindsey, School of Law, University of Reading, United Kingdom.

Chris Danbury, School of Law, University of Reading, United Kingdom; University Hospital Southampton, Southampton, United Kingdom.

Funding

Socio-Legal Studies Association research grant to Dr Jaime Lindsey and ESRC Impact Acceleration Account funding to Dr Jaime Lindsey.

Conflict of interest: I confirm that the empirical research on which this analysis is based received ethical approval from the University of Essex research ethics committee. Dr Chris Danbury is a practising mediator in this field.