Abstract

A series of new pyrazolate and mixed pyrazolate/pyrazole magnesium complexes is described and their reactivity toward carbon dioxide is examined. The dimeric complex [Mg(pz t Bu, t Bu)2]2 inserts CO2 instantly and quantitatively forming the tetrameric complex [Mg(CO2·pz t Bu, t Bu)2]4 and monomeric donor‐stabilized [Mg(CO2·pz t Bu, t Bu)2(thf)2]. Complexes of the type [Mg x (pzR,R)2 x (HpzR,R) y ] n (R = iPr, tBu) engage in similar insertion reactions involving dissociation of the carbamic acid HOOCpzR,R. Even solid polymeric derivatives [Mg(pzR,R)2] n (R = Me, H) react instantaneously and exhaustively with CO2, the resulting [Mg(CO2·pz)2] m featuring a CO2 capacity of 35.7 wt% (8.2 mmol g−1). All described magnesium pyrazolates display completely reversible CO2 uptake in solution and in the solid state, respectively, as monitored via VT 1H NMR and in situ FTIR spectroscopy as well as thermogravimetric analysis. Fluorinated [Mg2(pzCF3,CF3)4(thf)3] does not yield any isolable CO2 insertion product but exhibits the highest activity in the catalytic transformation of epoxides and CO2 to cyclic carbonates.

Keywords: carbon dioxide, catalysis, epoxides, magnesium, pyrazolates

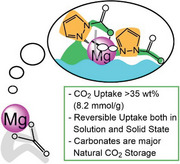

CO2 uptake of magnesium pyrazolates [Mg(pzR,R)2] to afford [Mg(CO2·pzR,R)2] is instant, quantitative, and reversible, both in solution and in the solid state. The CO2 affinity can be assessed by in situ Fourier‐transform infrared (FTIR)/nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, clearly surpassing that of corresponding trivalent and tetravalent rare‐earth‐metal derivatives, while pyrazolyl nucleophilicity drives the catalytic formation of cyclic carbonates in neat epoxide.

1. Introduction

Carbon dioxide emissions originating from fossil fuel (including energy sector and transportation; 2023: ca. 37 billion tons = 37 Gt) and as byproduct from industrial processes have been identified as the main causes of anthropogenic climate change.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ] Accordingly, CO2 management has evolved as a top‐prioritized research field. One strategy to reduce CO2 emissions is to capture the post‐combustion CO2 before it gets released into the atmosphere, in order to either permanently sequester it or utilize it further as an effective C1 synthon in organic synthesis.[ 6 , 7 ] Crucially, any sustainable valorization of CO2‐loaded materials is dependent on energy‐saving, reversible processes. Since the 1930s, aqueous amine scrubbers have been used in industry, but this technology is affected by low capacities (max. < 15 wt% CO2), sensitivity to oxygen and high regeneration energies (high “energy penalty”).[ 8 , 9 ] Current advanced technologies for CO2 uptake are based on alkali/alkaline‐earth metal hydroxides, amine‐containing ionic liquids or amine‐functionalized high‐surface materials such as porous silica, zeolites, or metal‐organic frameworks (MOF),[ 10 , 11 ] with carbamate formation as the most efficient underlying principle. Striking are the properties of magnesium carboxylate‐based MOFs such as Mg(dobdc) (= Mg2[2,5‐dioxido‐1,4‐benzenedicarboxylate] featuring a CO2 capacity of up to 35 wt%,[ 12 ] or the tetraamine‐appended MOF Mg(dobpdc) (= Mg2[4,4′‐dioxidobiphenyl‐3,3′‐dicarboxylate] which is currently the best system for cooperative CO2 capture from simulated flue gas.[ 13 , 14 ]

Magnesium is also a crucial component in natural CO2 storage in the lithosphere (insoluble sedimentary carbonates: >60 000 000 Gt) and in oceans (ca. 38 000 Gt inorganic carbon: CO2, bicarbonate, carbonate).[ 2 ] Our conceptual approach of CO2 capture is inspired by this natural role model and in a broader sense by the industrially applied (re)causticization of alkaline‐earth and alkali‐metal hydroxides.[ 6 ] Accordingly, modification of the dianionic carbonato moiety in terms of charge and functional group (CO3 2− → HCO3 − = (HO)CO2 − → (X)CO2 −; X = NR2 ≡ carbamato ligand) is envisaged to facilitate reversible CO2 uptake with minimum energy penalty (Figure 1 ).[ 15 ] In contrast to the aforementioned magnesium‐based MOFs, carbon dioxide is supposed to interact in a cooperative manner with the monoanionic nitrogen ligand X and the metal center.

Figure 1.

Top: design strategy of reversible molecular CO2 adsorbers. Middle: examples of structurally characterized magnesium carbamate complexes via CO2 insertion into Mg–N(amido) bonds. Bottom: examples of structurally characterized magnesium pyrazolate complexes.

The proof of concept was recently demonstrated for homoleptic cerium pyrazolate complexes which were found to reversibly insert CO2 to afford complexes [CeIV(CO2·pzMe,Me)4] and [CeIII 4(CO2·pzMe,Me)12] (max. 25 wt% CO2).[ 16 ] We wondered about the applicability of this approach for magnesium as an environmentally even friendlier oxophilic earth‐abundant light metal. Pertinent magnesium‐carbamate complexes such as mixed metallic [(Me2Al)2({µ‐CO2·NR2}2)2Mg] (R = Et, iPr) were already described 30 years ago, via CO2 insertion into Mg─N amido bonds (Figure 1).[ 17 ] The first homoleptic magnesium carbamate complex, hexameric [Mg6(CO2·NR2)12] (R = Et, Ph) was reported in 2001.[ 18 ] Since then, several more magnesium carbamate complexes appeared in the literature, however, CO2 insertion has proven irreversible.[ 19 ] The first and only homoleptic magnesium pyrazolate complex [Mg(pz t Bu, t Bu)2]2 (1) was reported by the group of Winter as a potential CVD precursor,[ 20 ] along with the donor adducts [Mg(pz t Bu, t Bu)2(thf)2]2 (1‐thf) and [Mg(pz t Bu, t Bu)2(tmeda)] (1‐tmeda). Moreover, the two mixed pyrazolato/pyrazole complexes [Mg(pz t Bu, t Bu)2(Hpz t Bu, t Bu)]2 (1‐Hpz)[ 21 ] and [Mg(pz i Pr, i Pr)2(Hpz i Pr, i Pr)]2 (4‐Hpz) are known.[ 22 ] The present study aims to adapt the class of magnesium pyrazolates for efficient CO2 capture and contributes to a better understanding of the effectiveness of such pyrazolate complexes in the catalytic formation of cyclic carbonates.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Why Magnesium? Why Pyrazoles?

Magnesium features an earth‐abundant, non‐toxic, non‐strategic light metal and hence is prone to high CO2 uptake (resulting in low “mass penalty”). Pyrazoles feature the conceptually required adjacent nitrogen coordination sites, while displaying flexible coordination behavior as evidenced by many distinct coordination modes.[ 23 ] As revealed by cerium pyrazolate complexes, the κ2(N,N’)‐coordinating pyrazolato ligand decisively promotes reversible and cooperative CO2 insertion by counteracting the mostly irreversible κ2(O,O’) coordination mode.[ 24 , 25 ] Moreover, pyrazoles are straightforwardly synthesized with easily tunable stereoelectronic properties via the 3,5‐substitution pattern. Such five‐membered heterocycles occur in natural products, albeit isolated pyrazoles cause severe toxicity for the nonsubstituted parent representative.[ 26 ]

2.2. Choice of Magnesium Pyrazolates

This study was launched with the discrete tBu‐substituted complexes [Mg(pz t Bu, t Bu)2]2 (1) and [Mg(pz t Bu, t Bu)2(thf)]2 (1‐thf) previously reported by Winter.[ 20 ] However, due to the apparent high “mass penalty” caused by the tBu moieties and the THF donor, further attempts were made to synthesize homoleptic magnesium pyrazolates with smaller substituents in the 3,5 positions, like iPr/iPr, mixed tBu/Me, Me/Me, and H/H. To probe any marked electronic effects on CO2 insertion, the CF3/CF3 variant was considered as well. In our hands, salt‐metathesis reactions of magnesium bromide with 3,5‐substituted potassium pyrazolates bearing alkyl groups smaller than tBu did not lead to the isolation of homoleptic magnesium pyrazolates. The mixed tBu/Me pyrazolato ligand afforded ate complex [KMg(pz t Bu,Me)3]2 (2) as the only isolable metathesis product (Scheme 1 ). For the other alkyl‐substituted pyrazolato ligands either no reaction took place or a complex mixture of products was observed.

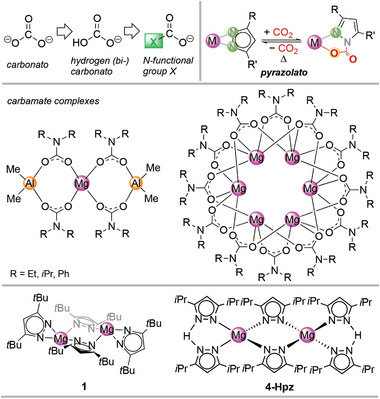

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of complexes 2 and 3‐thf bearing the mixed 3‐tert‐butyl‐5‐methyl pyrazolato ligand.

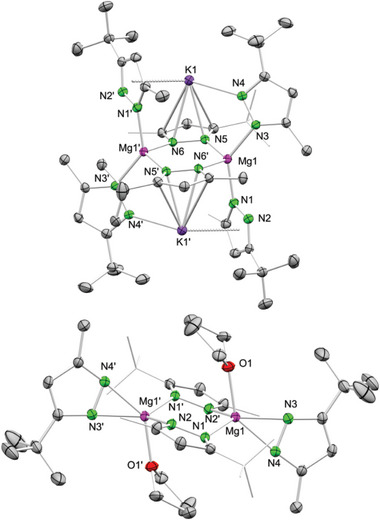

The single crystal X‐ray diffraction (SCXRD) analysis of 2 revealed a dimeric structure in which the two magnesium centers are bridged by two pyrazolato ligands in the µ−1κ(N):2κ(N’) mode forming a six‐membered ring, slightly distorted to a seat conformation (Figure 2 , top).[ 27 ] In addition, each magnesium center is κ1(N)‐coordinated by two pyrazolato ligands above and beneath the metalacyclic ring implying a strongly distorted tetrahedral coordination of the magnesium atoms. The three distinct pyrazolato ligands also encapsulate the potassium cations by bridging to the magnesium centers with the approximate coordination modes µ−1κ(N):2κ(N’), µ−1κ(N):2η5(pz), and µ−1κ(N):2κ(N):3η5(pz). The equilateral triangle N5–K1–N6 is perpendicular to the pyrazolyl plane (90.05°), while the angle between the planes of the η 4‐ and η 5‐coordinating pyrazolatos is close to perpendicular (95.14°).

Figure 2.

Crystal structures of [KMg(pz tBu,Me)3]2 (2, top) and [Mg(pz tBu,Me)2(thf)]2 (3‐thf, bottom). Ellipsoids are set at the 50% probability level. Hydrogen atoms are omitted and some Me/tBu moities are displayed as wireframe for clarity. See supporting information for selected interatomic distances and angles.[ 27 ]

Despite the different coordination modes, the 1H NMR spectrum of 2 in [D8]toluene shows one signal set of the aromatic proton, the methyl and the tert‐butyl groups indicating a high ligand mobility in solution.

Applying a protonolysis protocol by reacting Mg(nBu)2 with 2.5 equivalents of the corresponding pyrazole Hpz t Bu,Me in a n‐hexane/THF solution afforded the donor adduct [Mg(pz t Bu,Me)2(thf)]2 (3‐thf) (Scheme 1, Figure 2, bottom).[ 27 ] The crystal structure of 3‐thf revealed a dimeric complex isostructural to Winter´s tBu/tBu‐congener [Mg(pz t Bu, t Bu)2(thf)]2 with two µ−1κ(N):2κ(N’)‐bridging pyrazolato ligands, two terminal κ2(N,N’) pyrazolatos and two THF molecules.[ 20 ]

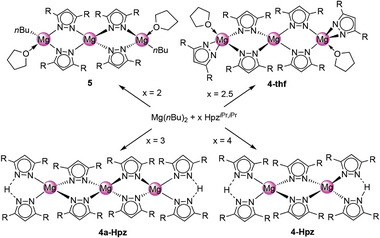

The mixed pyrazolato/pyrazole complex [Mg(pz i Pr, i Pr)2(Hpz i Pr, i Pr)]2 (4‐Hpz) reported by Ruhlandt‐Senge and co‐workers was obtained via protonolysis of Mg(nBu)2 with 4 equivalents of Hpz i Pr, i Pr in THF.[ 22 ] In order to avoid two potential reactive sites for CO2 (vide infra) and since homoleptic [Mg(pz i Pr, i Pr)2] has not yet been reported, we revisited the Mg(nBu)2/Hpz i Pr, i Pr reaction. It was revealed that alkane elimination is very sensitive to the molar ratio employed. Applying a 1:2 ratio in THF did not give the anticipated homoleptic complex but incomplete protonolysis to trimetallic complex [Mg3(pz i Pr, i Pr)4(nBu)2(thf)2] (5) with two remaining n‐butyl moieties (Scheme 2 ). The crystal structure revealed a central magnesium coordinated by four pyrazolato ligands, bridging to the peripheral magnesium centers in 1κ(N):2κ(N’) fashion (Figure S86, Supporting Information).[ 27 ] The tetrahedral coordination of the outer magnesium atoms is completed by one n‐butyl moiety and one THF molecule each. Note that Mg‐alkyl moieties irreversibly insert CO2 to afford carboxylato ligands.[ 24 , 28 ]

Scheme 2.

Formation of different complexes in the reaction of Mg(nBu)2 with Hpz iPr,iPr by using distinct ratios in THF. Complex 4‐Hpz has been reported previously.[ 22 ]

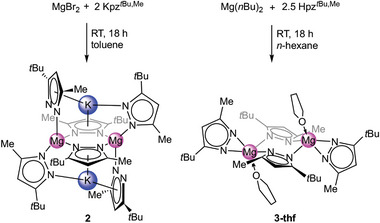

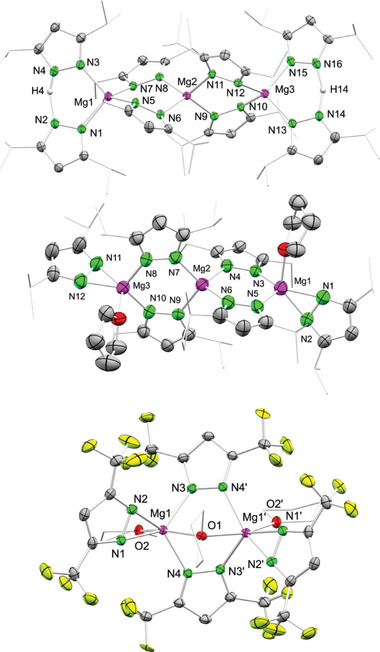

Aiming at a suitable compromise between incomplete protonolysis and coordination of excess pyrazole, the ratio of Mg(nBu)2 to Hpz i Pr, i Pr was increased to 1:3. Now, crystallization accomplished the trimetallic mixed pyrazolato/pyrazole complex [Mg3(pz i Pr, i Pr)6(Hpz i Pr, i Pr)2] (4a‐Hpz, Figure 3 , top).[ 27 ] Like in complex 5, each magnesium center adopts a distorted tetrahedral coordination sphere. Also, the central magnesium is coordinated by four η1(N)‐pyrazolato ligands, bridging to the outer magnesium atoms in the same fashion as in 5. Overall, a spiro arrangement of two six‐membered rings in half‐chair conformation about the central magnesium is observed. The outer magnesium atoms are further coordinated by pyrazolato and pyrazole ligands, which are connected via a N─H─N hydrogen bond. The pyrazolato and pyrazole ligands display a staggered arrangement when viewed along the axis of the magnesium centers.

Figure 3.

Crystal structures of [Mg3(pz iPr,iPr)6(Hpz iPr,iPr)2] (4a‐Hpz, top), [Mg3(pz iPr,iPr)6(thf)2] (4‐thf, middle) and [Mg2(pzCF3,CF3)4(thf)3] (6‐thf, bottom). Ellipsoids are set at the 50% probability level. Hydrogen atoms are omitted as well as the iPr groups and THF ligands are displayed as wireframe for clarity. See supporting information for selected interatomic distances and angles.[ 27 ]

The 1H NMR spectrum of 4a‐Hpz in [D8]toluene indicated a mixture of different species and, hence, fragmentation in solution. Remarkably, two proton signals appeared at 19.89 and 19.51 ppm, respectively, highly shifted to lower field and with a ratio of 1:0.2 (Figure S9, Supporting Information). Additionally, three signals in the region for the proton at the pyrazole ring can be observed along with several septet and doublet signals in the expected region for iPr moieties. The 1H NMR spectra of 4‐Hpz and 4a‐Hpz show the same signal pattern/fragments in [D8]toluene but different signal intensities, due to distinct pyrazolato/pyrazole ratios. The two strong low‐field shifted signals in 4‐Hpz appear in the reversed ratio of 0.2:1. The intensity of all other signals of 4‐Hpz are equally reversed, except for one signal at 5.84 ppm of the pyrazolato ring proton. The strongly low‐field shifted proton signals corroborate a low‐barrier hydrogen bond (LBHB) typical of symmetric hydrogen bonding.[ 29 ]

The very same fragmentation of 4‐Hpz and 4a‐Hpz in solution was confirmed by 1H DOSY (diffusion‐ordered spectroscopy) NMR experiments in [D8]toluene, revealing [Mg2(pz i Pr, i Pr)4(Hpz i Pr, i Pr)2] (M = 958.02 g mol−1) and [Mg2(pz i Pr, i Pr)4(Hpz i Pr, i Pr)] (M = 805.78 g mol−1) as preferred fragments (for an in‐depth discussion and other evaluation methods see the supporting information).[ 30 ]

Using a ratio of 1:2.5 of Mg(nBu)2 and Hpz i Pr, i Pr in the presence of THF first led to the isolation of a white amorphous powder, which after several recrystallization steps in n‐pentane afforded single‐crystalline [Mg3(pz i Pr, i Pr)6(thf)2] (4‐thf, Figure 3, middle).[ 27 ] The white amorphous powder is most likely the homoleptic donor‐free [Mg(pz i Pr, i Pr)2] n (4) forming an insoluble infinite chain structure. The crystal structure of 4‐thf is similar to that of 4‐Hpz except for the terminating donor ligand (THF versus Hpz). The syntheses of 3‐thf and 4‐thf underline that the formation of homoleptic [Mg(pzR,R`)2] n occurs preferentially when Mg(nBu)2 and HpzR,R` are employed in a ratio of 1:2.5.

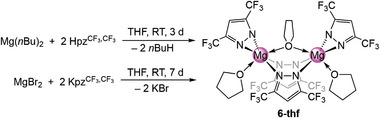

For the 3,5‐bis(trifluoromethyl)pyrazole, both the protonolysis and the salt‐metathesis route in THF yielded [Mg2(pzCF3,CF3)4(thf)3] (6‐thf) as a crystalline material (Scheme 3 ). The crystal structure of 6‐thf revealed 5‐coordinate magnesium centers in a strongly distorted trigonal bipyramidal geometry (Figure 3, bottom).[ 27 ] The magnesium centers are bridged by two µ−1κ(N):2κ(N’) pyrazolato and one µ−1κ(O):2κ(O) THF ligand.[ 31 ] The bridging THF distorts the six‐membered metallacycle to a twisted boat conformation. The 1H, 13C and 19F NMR spectra of 6‐thf revealed high mobility of the pyrazolato ligands in solution at ambient temperature. Both 1 J C,F (267.77 Hz) and 2 J C,F couplings (36.58 Hz) were observed as quartets at 123.0 ppm and 142.7 ppm, respectively.[ 32 ]

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of complex 6‐thf according to salt‐metathesis and protonolysis protocols.

Protonolysis of Mg(nBu)2 with both the 3,5‐dimethylpyrazole and the unsubstituted “parent” pyrazole gave amorphous white powders, which are insoluble in common solvents. However, the 13C CP/MAS (magic‐angle spinning) spectra unambiguously revealed the formation of [Mg(pzMe,Me)2] n (7) and [Mg(pz)2] n (8). For compound 7 the carbon resonances in the 3 and 5 position appeared as one signal at 152.1 ppm, while the carbon in the 4 position and the Me moieties were detected at 107.1 ppm and as two close signals at 12.0 and 10.9 ppm, respectively. As expected, compound 8 shows only two 13C signals in the aromatic region at 141.6 and 103.1 ppm, respectively. Both compounds most likely form an infinite chain structure like [Zn(pz)2] n which was characterized by powder X‐ray diffraction.[ 33 ] This is underlined by the fact, that the DRIFT spectra of 8 and [Zn(pz)2] n are nearly identical (Figure S79, Supporting Information).

The level of magnesium pyrazolate hydrolytic stability was probed for [Mg(pz t Bu, t Bu)2]2 (1) and [Mg(pz)2] n (8). When exposed to air (and moisture) a solution of 1 in THF shows slow decomposition as indicated by anhould incipient precipitation (Mg(OH)2) and formation of the respective pyrazole. A morphology change of mostly insoluble, flaky 8, mainly affecting the surface of the material, was clearly visible in SEM images upon exposure to ambient atmosphere (Figures S81–S83, Supporting Information).

2.3. CO2 Insertion into Magnesium Bis(pyrazolate)s under Anhydrous Conditions

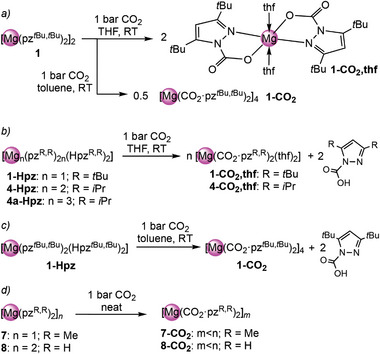

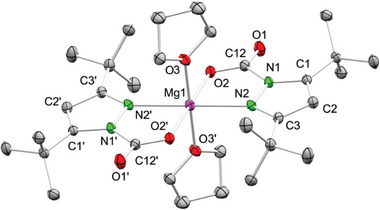

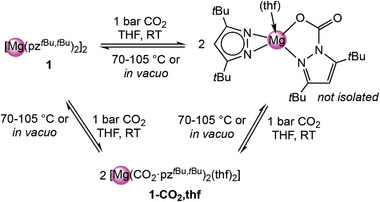

Exposing dimeric [Mg(pz t Bu, t Bu)2]2 (1) to 1 bar CO2 in THF led to the insertion of CO2 into the Mg─N(pyrazolato) bonds, forming the monomeric carbamate complex [Mg(CO2·pz t Bu, t Bu)2(thf)2] (1‐CO2,thf) (Scheme 4a).[ 34 ] The reaction occurs instantly in a small‐scale reaction and single crystals could be obtained overnight at ambient temperature. The mass fraction of 1‐CO2,thf amounts to 14.3 wt% CO2 or 3.3 mmol CO2 per gram.

Scheme 4.

Reaction of magnesium pyrazolates with excess CO2.

Complex 1‐CO2,thf displays a distorted octahedral coordination geometry, the magnesium center being coordinated by two nearly planar CO2·pz t Bu, t Bu carbamato moieties in the κ2(N,O) mode, and two apical THF donor molecules (Figure 4 ).[ 35 ] The inserted CO2 moiety exhibits an angle of 129.23(9)° and distinct C─O distances of 1.2165(12) and 1.2621(11) Å, which however, are less divergent from each other than in cerium complex [Ce(CO2·pzMe,Me)4] (1.207 Å and 1.291 Å).[ 16a ] This can be attributed to the less oxophilic character of magnesium compared to cerium.[ 36 ] The pyrazole ring of the carbamato ligand loses its aromaticity compared to the pyrazolato ligand of precursor 1, as revealed by distinct interatomic distances of both the C─C ring bonds (C2─C1: 1.3788(13) Å; C2─C3: 1.4073(13) Å) and the C─N ring bonds (C1─N1: 1.3800(12) Å; C3─N2: 1.3310(12) Å).

Figure 4.

Crystal structure of [Mg(CO2·pz tBu,tBu)2(thf)2] (1‐CO2,thf). Ellipsoids are set at the 50% probability level. Hydrogen atoms as well as disorder in the thf ligands are omitted for clarity. See supporting information for selected interatomic distances and angles.[ 27 ]

Carbon dioxide insertion into homoleptic pyrazolate 1 was initially observed by DRIFTS measurements showing the characteristic stretching vibration of the C─O double bond at = 1745 cm−1 and of the C─O single bond at = 1293 cm−1 (Figure S75, Supporting Information). The 1H NMR spectrum of 1‐CO2,thf in [D8]THF revealed the characteristic splitting of the tBu resonances into two signals at δ = 1.48 ppm and δ = 1.24 ppm (Figure S24, Supporting Information) due to the asymmetry caused by the inserted CO2. The 13C NMR signal of the inserted CO2 appeared at 149.0 ppm (Figure S25, Supporting Information) which is in the range of known complexes with CO2·pzR,R moieties.[ 16 , 37 ]

Complex 1‐CO2,thf is stable in solution at ambient temperature and as a solid at ‐40 °C. In neat form, CO2 slowly volatilizes at ambient temperature, as monitored by 1H NMR spectroscopy. Under reduced pressure (ca. 10−2 mbar), enhanced CO2 evaporation occurred, and after 6 h a mixture of 1‐CO2,thf, 1, and a proposed mono‐inserted complex was observed in the 1H NMR spectrum, in a ratio of 1:0.8:0.8 (Figure S26, Supporting Information). Admitting in turn 1 bar of CO2 led to the complete re‐formation of 1‐CO2,thf. This reversible behavior was further investigated by variable‐temperature (VT) 1H NMR spectroscopy (Figure S27, Supporting Information). The signal of 1 emerged at 70 °C, while at 105 °C 1‐CO2,thf was completely converted into 1. Cooling to ambient temperature did not afford complete re‐insertion of CO2 but again a mixture of 1‐CO2,thf, 1, and the mono inserted complex in a ratio of 1:1:1. After renewed addition of 1 bar CO2, the mixture quantitatively reformed 1‐CO2,thf, indicating that the overall CO2 insertion step is fully reversible (Scheme 5 ).[ 38 ]

Scheme 5.

Reversibility of CO2 insertion into the Mg─N bond of [Mg(pz tBu,tBu)2]2 (1) at elaborate temperature or reduced pressure (10‐2 mbar).

The CO2 de‐insertion process of 1‐CO2,thf was further investigated using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) by heating the solid from 28 °C to 450 °C and applying a heating rate of 2 K min−1 under constant argon flow (Figure S71, Supporting Information). The first step of 22.16 % mass loss between 78 °C and 134 °C corresponds to the release of the THF donor ligands (calcd. 23.5%). This is followed by two distinct de‐insertion steps of each CO2 (calcd. 7.2 % each) with mass‐loss events of 4.70 % between 134 °C and 170 °C and 6.15 % between 170 °C and 233 °C. The deviation from the calculated value can be explained by incipient gas formation before the TGA experiment and slightly overlapping release of donor THF and the first CO2 de‐insertion step. The two distinct de‐insertion steps observed by TGA support the proposed formation of the mono inserted complex, indicated by 1H NMR spectroscopy (Scheme 5).

The reaction of unsolvated 1 with CO2 in toluene or benzene did not afford a single‐crystalline product. However, the occurrence of a CO2 insertion was clearly indicated by the respective 1H NMR spectrum (Figure S30, Supporting Information). Five signals for the pyrazole backbone protons between 5.89 and 6.05 ppm each with an integral of 1 and nine signals for tBu moieties between 0.87 and 1.78 ppm, of which eight have an integral of 9 and one has an integral of 18, are detected. This pattern indicates that 1 reacts with CO2 in non‐donating solvents to a putatively oligomeric species 1‐CO2 (Scheme 4a). Compound 1‐CO2 was further examined by 1H DOSY NMR spectroscopy in [D8]toluene (Figures S31–S33, Supporting Information). Accordingly, only one large signal was revealed with a diffusion coefficient of logD = −8.96 log(m2 s−1) for all the 1H NMR signals mentioned above. The molar mass calculation of the measured diffusion coefficient, approximated by a highly compact sphere, accounts for a molar mass of 1875 g mol−1. This suggests that 1‐CO2 is a tetrameric oligomer/cluster containing four Mg(CO2·pz t Bu, t Bu)2 units with M = 1883.59 g mol−1 (see Supporting Information for a more in‐depth discussion).[ 30 ] The proposed complex [Mg(CO2·pz t Bu, t Bu)2]4 (1‐CO2) achieves a capacity of 18.7 wt% CO2 or 4.3 mmol CO2 per gram.

Reacting 4‐thf with 1 bar CO2 led to the formation of [Mg(CO2·pz i Pr, i Pr)2(thf)2] (4‐CO2,thf) (not shown in Scheme 4). Although the 1H NMR spectrum of 4‐thf is rather complicated (Figure S16, Supporting Information), due to possible fragmentation/oligomerization like in 4‐Hpz and 4a‐Hpz, the 1H NMR spectrum of 4‐CO2,thf revealed complete and clean CO2 insertion as indicated by two distinct iPr groups. The 13C NMR showed the corresponding iPr signal patterns and a resonance at 149.6 ppm for inserted CO2. Unfortunately, complex 4‐CO2,thf could not be obtained in single‐crystalline form. Conducting the 4‐thf/CO2 reaction in toluene (not shown in Scheme 4), gave also a complex 1H NMR spectrum (Figures S40 and S41, Supporting Information), but resulted in a few crystals suitable for an XRD analysis. The crystal structure of LiMg4(CO2·pz i Pr, i Pr)9, albeit of low quality (connectivity structure only) clearly revealed an exclusive carbamato environment of the metal centers (Figure S91, Supporting Information). The magnesium atoms are arranged tetrahedrally around a central lithium atom. Contamination of the reaction mixture with lithium originated from precursor Mg(nBu)2 as revealed by 7Li NMR spectroscopy. We assume that crystallization of putative donor‐free [Mg4(CO2·pz i Pr, i Pr)8] is strongly favored by the presence of the alkali metal.

Treatment of the mixed pyrazolato/pyrazole complexes 4‐Hpz, 4a‐Hpz, and known [Mg(pz t Bu, t Bu)2(Hpz t Bu, t Bu)]2 (1‐Hpz)[ 22 ] with CO2 was performed in the same way as for 1 (Scheme 4b). The 1H NMR spectra of the 1‐Hpz/CO2 reactions revealed signal sets identical to those of 1‐CO2,thf ([D8]THF) and 1‐CO2 (in [D8]toluene); for the reaction in THF, the formation of 1‐CO2,thf could be confirmed by a unit‐cell check of the obtained crystals. In both solvents, an additional set of four new broad signals is detected: two in the range of tBu moieties (δ = 1.28 and 1.23 ppm), one in the aromatic range (δ = 5.82 ppm) and one in the acidic proton range at δ = 11.34 ppm, which does not align with free Hpz t Bu, t Bu (Figure S34, Supporting Information). Furthermore, the presence of two tBu signals corroborates a reaction of CO2 with the donor pyrazole to yield the new carbamic acid HOOCpz t Bu, t Bu. Since free pyrazoles, like aromatic amines, do not react with CO2 under these conditions, it can be hypothesized that the hydrogen‐bond pyrazolato/pyrazole arrangement is a prerequisite for forming the carbamic acid/ammonium carbamate.[ 39 ] A similar motif was observed for compound [{Cd(µ‐ac)2(Hpz)2} n ] (ac = acetate) in which the acetate has an H‐bond interaction with the pyrazole.[ 33 ] Such two‐fold activation of CO2 also applies for the isopropyl‐substituted pyrazole adducts 4‐Hpz and 4a‐Hpz. The 1H NMR spectra display one signal set assignable to [Mg(CO2·pz i Pr, i Pr)2(thf)2] (4‐CO2,thf) with the expected splitting of the iPr signals. Additionally, one signal set appeared ascribed to the carbamic acid HOOCpz i Pr, i Pr. Both starting materials lead to similar spectra, with varying signal intensities, due to the different pyrazolato/pyrazole ratios. As for [Mg(pz t Bu, t Bu)2(Hpz t Bu, t Bu)]2 (1‐Hpz), the CO2 insertion is reversible for the carbamato ligand in 4‐CO2,thf, but remains irreversible for the disassociated carbamic acid, under the conditions applied (Scheme 4c).

Complex [Mg(pz t Bu,Me)2(thf)]2 (3‐thf) featuring the mixed tBu/Me 3,5‐substitution of the pyrazolato ligand clearly engaged in CO2 insertion. The resulting 1H NMR spectra, however, revealed very complicated signal pattern, which is why this complex was not pursued further. In contrast, CO2 insertion was not detected for fluorinated [Mg2(pzCF3,CF3)4(thf)3] (6‐thf), likely due to the decreased nucleophilicity of the pyrazolato nitrogen atoms (vide infra).

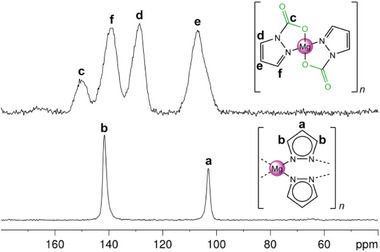

Unexpectedly, the polymeric pyrazolates Mg(pzMe,Me)2] n (7) and [Mg(pz)2] n (8), which are insoluble in most common solvents, feature a rather remarkable CO2‐insertion behavior Scheme 3d). When exposing the solids in a very simple manner to an atmosphere of 1 bar CO2 for three hours, a mass gain of 29.4 wt% for 7 and 36.3 wt% for 8 were found, accompanied by slight morphology change and warming of the samples. This is close to the calculated exhaustive CO2 insertion into the Mg–N(pyrazolato) bond, accounting for 29.1 and 35.7 wt% CO2, respectively. The obtained materials [Mg(CO2·pzMe,Me)2] n (7‐CO2) and [Mg(CO2·pz)2] n (8‐CO2) were further examined by TGA (Figures S72 and S73, Supporting Information) and solid‐state NMR and FTIR spectroscopy. For 7‐CO2, a CO2 release step of 29.5 % was observed when heating a sample from ambient temperature to 210 °C, in line with the CO2 mass fraction. Similarly, material 8‐CO2 revealed a mass‐loss event of 34.3 %, in the range from 50 °C to 225 °C. Different from 1‐CO2,thf and 8‐CO2, where the CO2 de‐insertion only starts at elevated temperatures, the CO2 release for 7‐CO2 already takes place at ambient temperature. The IR spectra of both complexes 7‐CO2 and 8‐CO2 (Figures S76 and S77, Supporting Information) show an intense and broad band between 1709 and 1744 cm−1 for the C─O double bond stretching vibration of the inserted CO2. The CO2 insertion/de‐insertion behavior of [Mg(pz)2] n (8) was further elucidated by conducting an in situ IR experiment. When replacing the argon atmosphere by CO2, immediate formation to 8‐CO2 took place. When restoring the argon atmosphere and heating in 10 °C steps to 240 °C, the C─O double bond stretching vibration at 1709 cm−1 slowly decreased and the overall IR spectrum converted back to that of 8 (Figure S80, Supporting Information). The 13C CP/MAS NMR spectrum of 7‐CO2 revealed distinct carbon atoms at the 3 and 5 positions (148.6 and 142.7 ppm) in comparison to 7 (152.1 ppm) The 13C signal of the inserted CO2 appeared as a shoulder to the signal at 148.6 ppm. To further clarify the signal assignment complex 7 was treated with labeled 13CO2, which resulted in two intense signals at 152.4 and 148.7 ppm. The signals of the methyl groups appeared as one signal at 12.3 ppm. Upon CO2 insertion, 7‐CO2 is soluble in THF and the respective 1H NMR spectrum confirmed its formation by two signals at 2.46 and 2.12 ppm of the methyl groups in 3 and 5 position. The solution 13C NMR signal of the inserted CO2 could be resolved at 149.8 ppm. The 13C CP/MAS NMR spectrum of 8‐CO2 shows four distinct signals in the aromatic region (Figure 5 ). The inserted CO2 appeared as a signal at 150.2 ppm, and the carbon atoms in 3 and 5 position at 139.1 and 128.6 ppm, and the carbon in 4 position at 107.2 ppm. Repeated CO2 insertion/de‐insertion was probed for 7/7‐CO2 and proven to be fully reversible by solid‐state NMR and FTIR spectroscopy (Figures S51 and S78, Supporting Information).

Figure 5.

13C CP/MAS NMR spectra (75.47 MHz) of [Mg(pz)2] n (8) and [Mg(CO2·pz)2] n (8‐CO2).

Comparative studies with literature known [Zn(pz)2] n and CO2 did not indicate any appreciable CO2 insertion.[ 40 ] Although both metal centers have the same charge and similar ionic radii, the pronounced oxophilicity of magnesium[ 36 ] combined with the harder Mg(II) ion determine the high CO2 affinity of the pyrazolate complexes compared to the zinc congeners.

Having established these solid/gas reactions for 7 and 8, a solid sample of 1 was exposed similarly to 1 bar CO2. A mass gain of 18.4 % close to the calculated mass fraction of 18.7 wt% CO2 suggested the formation of putative 1‐CO2 (vide supra). Dissolving the obtained solid in [D8]THF and [D8]toluene gave 1H NMR spectra identical to those of 1‐CO2,thf and 1‐CO2, respectively. The TGA of 1‐CO2 showed a continuous mass loss with less distinct releasing steps, which would be expected for a cluster species. For further comparison, our previously reported ceric pyrazolate [Ce(Me2pz)4(thf)] did not insert the heteroallene when stored under 1 bar CO2 pressure for three days.[ 16a ]

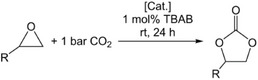

2.4. Catalytic Formation of Cyclic Carbonates from CO2 and Epoxides

The discrete complexes [Mg(pz t Bu, t Bu)2]2 (1), [Mg(pz t Bu,Me)2(thf)]2 (3‐thf), [Mg3(pz i Pr, i Pr)6(Hpz i Pr, i Pr)2] (4a‐Hpz), [Mg3(pz i Pr, i Pr)6(thf)2] (4‐thf), and [Mg2(pzCF3,CF3)4(thf)3] (6‐thf) were probed as catalysts in the cycloaddition of epoxides and CO2 to cyclic carbonates (see Scheme S2, Supporting Information for a proposed mechanism). For better comparability, the conditions stated in Table 1 have been adapted to those reported previously for the rare‐earth‐metal pyrazolates.[ 16a ]

Table 1.

Formation of cyclic carbonates from epoxides and CO2, catalyzed by magnesium pyrazolates under study.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry a) | Catalyst | R = | Conversion [%] b) | TON c) |

| 1 | 1 | Me | 56 | 112 |

| 2 d) | 1 | Me | 85 | 85 |

| 3 | 1 | Ph | 4 | 8 |

| 4 | 1 | tBu | 4 | 8 |

| 5 | 1 | nBu | 7 | 14 |

| 6 | 1‐thf | Me | 51 | 102 |

| 7 | 3‐thf | Me | 43 | 86 |

| 8 | 4a‐Hpz | Me | 45 | 90 |

| 9 e) | 4a‐Hpz | Me | 77 | 51 |

| 10 | 4a‐Hpz | Ph | 4 | 8 |

| 11 | 4a‐Hpz | tBu | 3 | 6 |

| 12 | 4a‐Hpz | nBu | 11 | 22 |

| 13 | 4‐thf | Me | 42 | 84 |

| 14 | 6‐thf | Me | 59 | 118 |

| 15 | 6‐thf | Ph | 8 | 16 |

| 16 | 6‐thf | tBu | 4 | 8 |

| 17 | 6‐thf | nBu | 18 | 36 |

| 18 f) | – | Me | 3 | 6 |

Reaction conditions if not noted otherwise: 1 bar CO2, 0.25 mol% catalyst or 0.167 mol% for 4a‐Hpz and 4‐Hpz (≡0.5 mol% Mg centers), 1 mol% TBAB at ambient temperature for 24 h in neat epoxide;

Determined by comparison of the proton integrals in α‐position of the epoxide and the corresponding cyclic carbonate (expect for 3,3‐dimethyl‐1,2‐butene carbonate where the integral of the tBu moieties was used);

((epoxide/Mg) · conversion)/100;

1 bar CO2, 1 mol% catalyst 1, 1 mol% TBAB, at ambient temperature for 24 h;

1 bar CO2, 0.5 mol% catalyst 4a‐Hpz, 1 mol% TBAB, at ambient temperature for 24 h.

only TBAB without metal catalyst; TON refers to concentration TBAB.

Complex [Mg(pz t Bu, t Bu)2]2 (1) gave 56 % conversion of propylene oxide and CO2 to the cyclic carbonate, with a TON of 112 (Table 1, entry 1). By using a twofold catalyst load of 1 mol% the conversion increased to 85 %, while the TON decreased to 85 (entry 2). This might result from catalyst aggregation in solution, by exceeding the solubility of 1 in epoxide or due to a solubility gradient shift between epoxide and cyclic carbonate. As expected, donor adduct 1‐thf showed a slightly lower conversion of 51 % (entry 6). Similarly, for catalysts 3‐thf, 4a‐Hpz and 4‐thf the conversion slightly decreased to 43 %, 45 % and 42 %, respectively (entries 7 to 8 and 13). As mentioned before, the pyrazole donors disassociate upon CO2 insertion as carbamic acid which can lead also to solubility shifts or blocking of the metal center. Increasing the amount of 4a‐Hpz from 0.167 mol% (≡0.5 mol% Mg centers) to 0.5 mol% complex 4a‐Hpz (≡1.5 mol% Mg centers) led to an enhanced conversion of 77 % but also here the TON was reduced to 51 (entry 9). Accordingly, the effects of reduced catalytic activity due to high catalyst load seem to be intrinsic.

Interestingly, fluorinated complex 6‐thf shows the highest catalytic activity with a TON of 118 (entry 14), despite a side reaction, causing a highly viscous reaction mixture. Crucially, 6‐thf exhibits the highest catalytic activity although it does not insert CO2 (vide supra). Consequently, catalytic activity and CO2 affinity seem to be inversely proportional. As expected, switching to the more sterically demanding epoxides with tBu, nBu and Ph moieties, the conversion is drastically decreased ranging from 4% to 11% (entries 3–5, 10–12 and 15–17). Again, striking is comparatively increased catalytic activity in case of 6‐thf, giving 18% conversion of epoxyhexane in the absence of any side reaction. Complexes 7 and 8 showed also moderate conversion, however, due to high contents of insoluble oligomeric/polymeric side products, these values were not considered representative.

To determine the state of the catalyst after the catalytic reaction, each 10 mol% of 1 and TBAB were employed and the reaction mixture examined by 1H NMR spectroscopy (Figure S70, Supporting Information). Besides the signals for TBAB and propylene carbonate, one signal set could be assigned to complex [Mg(CO2·pz t Bu, t Bu)2(thf)2] (1‐CO2,thf). Moreover, three additional signals in the region for pyrazolate backbones were detected, assignable neither to the carbamic acid, a mono‐inserted species nor to a hydrolysis product.

The overall catalytic activity of the magnesium pyrazolates is only moderate in comparison to the rare‐earth‐metal congeners.[ 16a ] For example, cerium pyrazolate [Ce(Me2pz)4]2 converted up to 98 % of propylene oxide with a TON of 196, under the same conditions. By heating the cerium reaction up to 90 °C, applying a pressure of 10 bar CO2 and using a catalytic load of 0.1 mol% the TON could even be increased to 600. This is clearly reflected in the higher CO2 release temperatures of magnesium pyrazolates (higher CO2 affinity), in agreement with the NMR/TGA studies (vide supra). Also, in comparison to other magnesium catalysts used in this very cycloaddition reaction, our complexes show only moderate catalytic activity.[ 35 , 41 ] Although hardly comparable due to much harsher reaction conditions, a magnesium porphyrin complex with an incorporated tetra‐n‐butylammonium reported by Ema et al. reaches TONs of up to 138 000 with a catalytic load of 0.0005 mol%, at 120 °C and 17 bar CO2.

3. Conclusion

The conceptional approach of carbon dioxide insertion into metal pyrazolates is applicable to the light metal magnesium. Exhaustive CO2 insertion into the Mg–N(pzR,R) bond is proven by the crystal structure of [Mg(CO2·pz t Bu, t Bu)2(thf)2] as well as 13C NMR spectroscopy and thermogravimetric analysis of [Mg(CO2·pzR,R)2] n (R = H, Me, iPr). Carbon dioxide uptake at ambient temperature is instant and reversible with de‐insertion temperatures <250 °C. Remarkably, CO2 insertion also occurs quantitatively using the magnesium pyrazolates in solid form (without solvent!). Unsubstituted [Mg(CO2·pz)2] n accomplishes a maximum capacity of 35.7 wt% CO2 (8.2 mmol g−1) leveling that of the most efficient metalorganic frameworks (MOFs). Depending on the pyrazolate substituents R, the homoleptic magnesium complexes are easily obtained via salt metathesis or protonolysis applying MgBr2 and Mg(nBu)2, respectively. For the protonolysis protocol, stoichiometric control and hence pyrazole coordination are critical since the CO2 uptake is affected by additional formation of the respective carbamic acids HOOCpzR,R. The salt‐metathesis protocol is prone to ate complex formation as evidenced for [KMg(pz t Bu,Me)3]2. The magnesium pyrazolates display only moderate catalytic activity in the reaction of CO2 and epoxides to cyclic carbonates. Crucially, catalytic activity and CO2 affinity seem to be inversely proportional, as revealed by the fluorinated complex [Mg2(pzCF3,CF3)4(thf)3], exhibiting the highest catalytic activity while lacking any traceable CO2 insertion, under the applied conditions. Overall, the catalytic activity is lower than that of the cerium congeners attributable to the higher CO2 release temperatures of the magnesium complexes. Due to significant hydrolytic instability such magnesium pyrazolate complexes are not meant for any industrial large scale carbon dioxide removal technology but might stimulate new inorganic material design.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the VECTOR foundation (grant P2021‐0099) for generous support. The authors thank Dr. Klaus Eichele for measuring the solid‐state NMR spectra, Dr. Wolfgang Leis for discussing and measuring the 1H DOSY NMR spectra, and Dr. Markus Ströbele for executing the TGA measurements.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Kracht F., Rolser P., Preisenberger P., Maichle‐Mössmer C., Anwander R., Organomagnesia: Reversibly High Carbon Dioxide Uptake by Magnesium Pyrazolates. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2403295. 10.1002/advs.202403295

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.

References

- 1.a) Dhakal S., Minx J. C., Toth F. L., Abdel‐Aziz A., Figueroa Meza M. J., Hubacek K., Jonckheere I. G. C., Kim Y.‐G., Nemet G. F., Pachauri S., Tan X. C., Wiedmann T., Emissions Trends and Drivers, IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation Of Climate Change. Contribution Of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change , (Eds: Shukla P. R., Skea J., Slade R., Al Khourdajie A., van Diemen R., McCollum D., Pathak M., Some S., Vyas P., Fradera R., Belkacemi M., Hasija A., Lisboa G., Luz S., Malley J., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA: 2022; [Google Scholar]; b) The critical annual update revealing the latest trends in global carbon emissions, https://globalcarbonbudget.org (accessed: May 2024).

- 2. Falkowski P., Scholes R. J., Boyle E., Canadell J., Canfield D., Elser J., Gruber N., Hibbard K., Högberg P., Linder S., Mackenzie F. T., Moore B. III, Pedersen T., Rosenthal Y., Seitzinger S., Smetacek V., Steffen W., Science 2000, 290, 291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Solomon S., Plattner G.‐K., Knutti R., Friedlingstein P., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Haszeldine R. S., Science 2009, 325, 1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Keith D. W., Science 2009, 325, 1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Chu S., Science 2009, 325, 1599 ; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) D'Alessandro D. M., Smit B., Long J. R., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 6058; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2010, 122, 745; [Google Scholar]; c) Yu C.‐H., Huang X.‐H., Tan C.‐S., Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2012, 12, 745; [Google Scholar]; d) Sanz‐Pérez E. S., Murdock C. R., Didas S. A., Jones C. W., Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 11840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Sakakura T., Choi J.‐C., Yasuda H., Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 2365; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Centi G., Perathoner S., Catal. Today 2009, 148, 191; [Google Scholar]; c) Cokoja M., Bruckmeier C., Rieger B., Herrmann W. A., Kühn F. E., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 8510; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2011, 123, 8662; [Google Scholar]; d) Aresta M., Dibenedetto A., Angelini A., Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 1709; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) von der Assen N., Voll P., Peters M., Bardow A., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 7982; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Liu Q., Wu L., Jackstell R., Beller M., Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5933; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Kleij A. W., North M., Urakawa A., ChemSusChem 2017, 10, 1036; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Artz J., Müller T. E., Thenert K., Kleinekorte J., Meys R., Sternberg A., Bardow A., Leitner W., Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 434; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Olivier A., Desgagnés A., Mercier E., Iliuta M. C., Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 5714. [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Rochelle G. T., Science 2009, 325, 1652 ; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Brœder P., Svendsen H. F., Energy Procedia 2012, 23, 45; [Google Scholar]; c) Heldebrant D. J., Koech P. K., Glezakou V.‐A., Rousseau R., Malhotra D., Cantu D. C., Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 9594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen H., Dong H., Shi Z., SenGupta A. K., Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadg1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Jadhav P. D., Chatti R. V., Biniwale R. B., Labhsetwar N. K., Devotta S., Rayalu S. S., Energy Fuels 2007, 21, 3555; [Google Scholar]; b) Zeng S., Zhang X., Bai L., Zhang X., Wang H., Wang J., Bao D., Li M., Liu X., Zhang S., Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 3555; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Siegelman R. L., Milner P. J., Kim E. J., Weston S. C., Long J. R., Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 2161; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Forse A. C., Milner P. J., Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 2161. [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Mason J. A., Sumida K., Herm Z. R., Krishna R., Long J. R., Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 3030; [Google Scholar]; b) Sumida K., Rogow D. L., Mason J. A., McDonald T. M., Bloch E. D., Herm Z. R., Bae T.‐H., Long J. R., Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 724; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Lin Y., Kong C., Zhang Q., Chen L., Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1601296. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Caskey S. R., Wong‐Foy A. G., Matzger A. J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 10870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) McDonald T. M., Mason J. A., Kong X., Bloch E. D., Gygi D., Dani A., Crocellà V., Giordanino F., Odoh S. O., Drisdell W. S., Vlaisavljevich B., Dzubak A. L., Poloni R., Schnell S. K., Planas N., Lee K., Pascal T., Wan L. F., Prendergast D., Neaton J. B., Smit B., Kortright J. B., Gagliardi L., Bordiga S., Reimer J. A., Long J. R., Nature 2015, 519, 303; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kim E. J., Siegelman R. L., Jiang H. Z. H., Forse A. C., Lee J.‐H., Martell J. D., Milner P. J., Falkowski J. M., Neaton J. B., Reimer J. A., Weston S. C., Long J. R., Science 2020, 369, 392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kadota K., Hong Y., Nishiyama Y., Sivaniah E., Packwood D., Horike S., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 16750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.It is worth mentioning that naturally occurring simple binary carbonates limit themselves to alkali and alkaline‐earth metals (except Be), and the divalent d‐metals Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Zn, Cd; furthermore, NaHCO3 is the only proven natural bicarbonate. CO2 capture from air with caustic solutions involves a calcination process regenerating CaO from CaCO3 at temperatures above 700 °C.

- 16.a) Bayer U., Werner D., Maichle‐Mössmer C., Anwander R., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 5830; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 5879; [Google Scholar]; b) Bayer U., Liang Y., Anwander R., Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 14605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chang C.‐C., Srinivas B., Mung‐Liang W., Wen‐Ho C., Chiang M. Y., Chung‐Sheng H., Organometallics 1995, 14, 5150. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yang K.‐C., Chang C.‐C., Yeh C.‐S., Lee G.‐H., Peng S.‐M., Organometallics 2001, 20, 126. [Google Scholar]

- 19.a) Caudle M. T., Kampf J. W., Inorg. Chem. 1999, 38, 5474; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ruben M., Walther D., Knake R., Görls H., Beckert R., Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2000, 2000, 1055; [Google Scholar]; c) Tang Y., Zakharov L. N., Rheingold A. L., Kemp R. A., Organometallics 2004, 23, 4788; [Google Scholar]; d) Himmel H.‐J., Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2007, 633, 2191. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pfeiffer D., Heeg M. J., Winter C. H., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998, 37, 2517; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 1998, 110, 2674. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mösch‐Zanetti N. C., Ferbinteanu M., Magull J., Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2002, 2002, 950. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hitzbleck J., Deacon G. B., Ruhlandt‐Senge K., Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 2007, 592. [Google Scholar]

- 23.a) Halcrow M. A., Dalton Trans. 2009, 38, 2059; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Torvisco A., O'Brien A. Y., Ruhlandt‐Senge K., Coord. Chem. Rev. 2011, 255, 1268; [Google Scholar]; c) Werner D., Bayer U., Rad N. E., Junk P. C., Deacon G. B., Anwander R., Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 5952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.a) Ayyappan R., Abdalghani I., Da Costa R. C., Owen G. R., Dalton Trans. 2022, 51, 11582; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Pérez‐Jiménez M., Corona H., de la Cruz‐Martínez F., Campos J., Chem. Eur. J. 2023, 29, e202301428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bresciani G., Biancalana L., Pampaloni G., Marchetti F., Molecules 2020, 25, 3603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.a) Magnusson G., Nyberg J.‐A., Bodin N.‐O., Hansson E., Experientia 1972, 28, 1198; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kamel M. M., Acta Chim. Slovaca 2015, 62, 136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Deposition numbers 2342200 (for 2), 2342196 (for 3‐thf), 2342195 (for 5), 2342199 (for 4a‐Hpz), 2342201 (for 4‐thf), 2342198 (for 6‐thf), 2342197 (for 1‐CO2,thf) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data are provided free of charge by the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center, https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/ (accessed: May 2024).

- 28. Pfennig V. S., Villella R. C., Nikodemus J., Bolm C., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202116514; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2022, 134, e202116514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.a) Gunnarsson G., Wennerström H., Egan W., Forsén S., Chem. Phys. Lett. 1976, 38, 96; [Google Scholar]; b) Hibbert F., Emsley J., in Advances in Physical Organic Chemistry (Ed: Bethell D.), Academic Press, London: 1990, pp. 255–379; [Google Scholar]; c) Kumar G. A., McAllister M. A., J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 6968; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Gilli G., Gilli P., J. Mol. Struct. 2000, 552, 1. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Neufeld R., Stalke D., Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 3354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.a) Snyder C. J., Heeg M. J., Winter C. H., Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 9210; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) De Bruin‐Dickason C. N., Deacon G. B., Jones C., Junk P. C., Wiecko M., Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 2019, 1030. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Afonin A. V., Ushakov I. A., Pavlov D. V., Petrova O. V., Sobenina L. N., Mikhaleva A. I., Trofimov B. A., J. Fluorine Chem. 2013, 145, 51. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Masciocchi N., Galli S., Alberti E., Sironi A., Di Nicola C., Pettinari C., Pandolfo L., Inorg. Chem. 2006, 45, 9064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Belli DellÁmico D., Calderazzo F., Labella L., Marchetti F., Pampaloni G., Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 3857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.a) Raghavendra B., Bakthavachalam K., Ramakrishna B., Reddy N. D., Organometallics 2017, 36, 4005; [Google Scholar]; b) Raghavendra B., Shashank P. V. S., Pandey M. K., Reddy N. D., Organometallics 2018, 37, 1656; [Google Scholar]; c) Bott R. K. J., Schormann M., Hughes D. L., Lancaster S. J., Bochmann M., Polyhedron 2006, 25, 387; [Google Scholar]; d) Gallegos C., Tabernero V., García‐Valle F. M., Mosquera M. E. G., Cuenca T., Cano J., Organometallics 2013, 32, 6624. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kepp K. P., Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 9461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tseng Y.‐T., Ching W.‐M., Liaw W.‐F., Lu T.‐T., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 11819; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 11917. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jin D., Sun X., Hinz A., Roesky P. W., CCS Chem. 2023, 5, 1277. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Aresta M., Ballivet‐Tkatchenko D., Belli DellÁmico D., Bonnet M. C., Boschi D., Calderazzo F., Faure R., Labella L., Marchetti F., Chem. Commun. 2000, 1099. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cingolani A., Galli S., Masciocchi N., Pandolfo L., Pettinari C., Sironi A., Dalton Trans. 2006, 35, 2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.a) Ema T., Miyazaki Y., Koyama S., Yano Y., Sakai T., Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 4489; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ema T., Miyazaki Y., Shimonishi J., Maeda C., Hasegawa J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 15270; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Maeda C., Taniguchi T., Ogawa K., Ema T., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 134; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 136; [Google Scholar]; d) Maeda C., Shimonishi J., Miyazaki R., Hasegawa J., Ema T., Chemistry 2016, 22, 6556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.