Significance

The rising prevalence of neck pain is believed to be associated with the sedentary trend of modern work, prolonged use of hand-held devices, and fundamentally, fatiguing mechanical loads. However, while the notion that muscle fatigue increases susceptibility to injury is almost taken for granted, evidence to support this notion remains sparse and fragmented. Critically missing is the knowledge of what exactly happens mechanically to the involved muscles and connected tissues during a fatiguing physical act. We seek to fill this knowledge void through a unique experiment of neck sustained-till-exhaustion exertions and the use of high-precision dynamic stereo-radiographic imaging. We demonstrate that a sustained exertion leads to further bending of the neck and thus modifies its mechanics and propensity for injury.

Keywords: neck mechanics, muscle fatigue, cervical spine deflection, dynamic radiographic imaging

Abstract

The human neck is a unique mechanical structure, highly flexible but fatigue prone. The rising prevalence of neck pain and chronic injuries has been attributed to increasing exposure to fatigue loading in activities such as prolonged sedentary work and overuse of electronic devices. However, a causal relationship between fatigue and musculoskeletal mechanical changes remains elusive. This work aimed to establish this relationship through a unique experiment design, inspired by a cantilever beam mechanical model of the neck, and an orchestrated deployment of advanced motion-force measurement technologies including dynamic stereo-radiographic imaging. As a group of 24 subjects performed sustained-till-exhaustion neck exertions in varied positions—neutral, extended, and flexed, their cervical spine musculoskeletal responses were measured. Data verified the occurrence of fatigue and revealed fatigue-induced neck deflection which increased cervical lordosis or kyphosis by 4–5° to 11°, depending on the neck position. This finding and its interpretations render a renewed understanding of muscle fatigue from a more unified motor control perspective as well as profound implications on neck pain and injury prevention.

While the notion that muscle fatigue increases susceptibility to injury is almost taken for granted, evidence to support this notion remains sparse and fragmented. This is because muscle fatigue as a sequence of events is only partially observable or measurable and potentially injurious conditions cannot be tested on living human subjects. One critically missing piece is knowledge of what exactly happens mechanically to the involved muscles and connected tissues during a fatiguing physical act. This knowledge is central to a clear and holistic understanding of the relationship between muscle fatigue and risk of mechanical injury.

A multimuscle system in a sustained isometric exertion is a simple and frequently adopted human experiment model for testing various hypotheses regarding musculoskeletal mechanical responses to fatigue (1–5), wherein electromyography (EMG) has been the primary means to measure muscle activation and verify the occurrence of fatigue (2, 6–12). Since muscles vary in size, fiber composition, and thus fatiguability—the rate at which the force production ability diminishes secondary to prolonged or repeated muscle activation, a multimuscle system would constantly attempt to re-establish a new equilibrium and sustain a stabilized exertion (13). This would manifest itself as dynamic changes in muscle recruitment or activation pattern and possibly underlying skeletal movement despite a supposedly isometric or statically held exertion.

Muscle activation pattern changes during fatiguing isometric contractions have been observed and most often interpreted as increases of agonist–antagonist coactivation or antagonist activation (4, 14–19). On the other hand, the underlying bone position changes, which would be expected according to musculoskeletal dynamics and would provide an ultimate proof of the hypothesized cascade of events accompanying or ensuing muscle fatigue, have never been observed. The observability of such changes may have been hindered by two factors. First, prior studies all have used an experimental model or setup allowing limited mobility or degrees of freedom in the system, whether it be a multimuscle single-joint system or one that is dynamically constrained or robust; in other words, there is little room to permit changes in the system (20, 21). Second, the subtlety and elusiveness of the bone displacements make it challenging to capture them with measurement modalities commonplace in laboratories. Optical or inertial motion capture methods are plagued by excessive soft tissue motion artifacts and do not have the required precision and accuracy to discern the underlying small-amplitude bone displacements (22–24). Conventional radiography (X-ray) and computed tomography (CT) imaging techniques can be used to acquire bone morphology or geometry information directly, but neither is capable of continuously tracking and resolving time-dependent bone position changes or skeletal kinematics.

In this work, we created a unique experimental model to elicit bone displacement in response to muscle fatigue wherein the head-and-neck, as a multimuscle multijoint system with substantial mobility, engaged in isometric sustained-till-exhaustion exertions (Fig. 1). We designed the exertions to be ones of pushing the head against a force sensor while the shoulders and torso were restrained such that the head–neck system would be likened mechanically to a supported cantilever beam structure. We used a high-speed high-precision dynamic radiographic imaging system to capture the hypothesized small-amplitude cervical vertebral displacements throughout the exertions and an EMG system to monitor the myo-electrical activities of major neck muscles. With the experimental model and an orchestrated deployment of advanced motion–force measurement technologies, we tested a group of 24 healthy subjects to look for consistent musculoskeletal mechanical changes in fatigued necks. With an approximately sex-balanced (11 males and 13 females) design, we also sought to identify potential sex differences in the musculoskeletal responses to fatigue and gain insight into the reported sex disparity in neck pain prevalence and injury risk.

Fig. 1.

Exertion tasks, biplane dynamic X-ray images, and captured fatigue-induced cervical spine displacements. (A) Three exertion tasks varied in the head–neck position and exertion direction; the red arrows indicate the directions of reaction forces to the head. (B) Biplane DSX images captured at the start and end of fatiguing isometric neck exertions in three positions. (C) Superimposed cervical spine sagittal views at the start (dark gray) and end (light silver) of the exertions in three positions from three representative subjects with C7 fixed as the common base; orange curved arrows represent the displacement directions.

Results

Occurrence of Muscle Fatigue.

Muscle fatigue manifests itself in the EMG signal as a decreasing trend of median frequency over a sustained contraction (2, 6, 8, 9, 12, 25). An inspection of the EMG spectrum reveals that all neck muscles measured in all exertions exhibit significant (P < 0.05) negative slopes (Table 1) on the corresponding frequency-time plots (Fig. 2B). This confirms the occurrence of muscle fatigue upon termination of the exertions which lasted on average 82 s (SD: 43 s), 56 s (SD: 23 s), and 117 s (SD: 68 s) in the neutral, 40° extended, and 40° flexed positions (Fig. 1), respectively.

Table 1.

EMG median frequency slopes for four major neck muscles on each side

| Position | Neutral | Extended | Flexed | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle name | Mean | SE | P value | Mean | SE | P value | Mean | SE | P value |

| Flexors | |||||||||

| Left SCM | −0.27 | 0.10 | 0.008* | −0.56 | 0.16 | 0.001* | −0.48 | 0.20 | 0.012* |

| Right SCM | −0.39 | 0.10 | 0.000* | −0.54 | 0.14 | 0.001* | −0.89 | 0.20 | 0.000* |

| Left Hyoid | −0.57 | 0.11 | 0.000* | −0.62 | 0.20 | 0.002* | −0.54 | 0.20 | 0.007* |

| Right Hyoid | −0.50 | 0.12 | 0.000* | −0.38 | 0.12 | 0.003* | −0.52 | 0.26 | 0.030* |

| Extensors | |||||||||

| Left Trap | −1.23 | 0.31 | 0.000* | −0.92 | 0.33 | 0.008* | −0.40 | 0.14 | 0.005* |

| Right Trap | −1.34 | 0.32 | 0.000* | −1.44 | 0.39 | 0.001* | −0.42 | 0.12 | 0.001* |

| Left SPL | −0.37 | 0.13 | 0.005* | −0.43 | 0.17 | 0.012* | −0.34 | 0.16 | 0.025* |

| Right SPL | −0.35 | 0.11 | 0.002* | −0.48 | 0.16 | 0.003* | −0.39 | 0.14 | 0.004* |

An asterisk (*) indicates statistical significance (P ≤ 0.05). SCM, Hyoid, Trap, and SPL abbreviate sternocleidomastoids, infrahyoid, trapezius at C4–C5 level, and splenius capitis, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Force of exertion (A), median frequency of the SCM muscle (B), DSX recordings (C), and tracked bone models (D) of the cervical spine at the start (dark gray) and end (light silver) of a fatiguing neck exertion in the neutral position for a representative subject.

Fatigue-Induced Cervical Spine Deflection.

The cervical spine (C1–C7) as a whole column exhibits significant deflection in the sagittal plane in response to muscle fatigue. Here, the term “deflection” is adopted because the cervical spine structure is modeled as a supported beam but with one caveat: the cervical spine in the sagittal plane is naturally curved when free of external loading. It is in lordosis when neutral and extended and in kyphosis when flexed. The average deflections, measured as the total cervical curvature changes in the sagittal plane (Table 2), are −11.4° (more lordotic), −4.0° (more lordotic), and +5.5° (more kyphotic) for the neutral, extended, and flexed positions, respectively. These deflections are in the same direction of external loading in that the cervical spine responded to fatigue as if the deflections were caused by increased loading to the beam structure. The magnitude is considerably greater in the neutral position than in the extended or flexed position.

Table 2.

Overall cervical spine (C1–C7) displacements during fatiguing exertions

| Position | Neutral | Extended | Flexed | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Displacement | Mean | SE | P value | Mean | SE | P value | Mean | SE | P value |

| Rotation | |||||||||

| FE (°) | −11.4 | 1.41 | 0.000* | −4.0 | 1.31 | 0.007* | 5.5 | 0.98 | 0.000* |

| AR (°) | 0.35 | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.26 | 0.53 | 0.63 | 0.87 | 0.72 | 0.25 |

| LB (°) | 0.32 | 0.48 | 0.53 | −0.07 | 0.42 | 0.87 | 1.61 | 0.68 | 0.03* |

| Translation | |||||||||

| AP (mm) | −10.03 | 1.74 | 0.000* | −3.40 | 1.55 | 0.04* | 7.60 | 1.70 | 0.000* |

| SI (mm) | −3.99 | 1.21 | 0.002* | −2.30 | 1.11 | 0.06 | −1.76 | 0.46 | 0.001* |

| LM (mm) | 0.01 | 0.56 | 0.99 | 0.77 | 0.49 | 0.14 | −2.97 | 0.91 | 0.004* |

An asterisk (*) indicates statistical significance (P ≤ 0.05). FE, AR, and LB abbreviate flexion–extension, axial rotation, and lateral bending, respectively. LM, SI, and AP abbreviate lateral-medial, superior–inferior, and anterior–posterior translations, respectively.

Fatigue-Induced Cervical Intervertebral Displacement.

The overall cervical spine deflections are apportioned among six individual intervertebral joints (C1–C2 to C6–C7) in two contrasting patterns depending upon the cervical spine curvature (Fig. 3). In the neutral and extended positions where the cervical spine is lordotic, a tendency of the more centered joints (e.g., C3–C4, C4–C5) contributing more to FE rotation and anterior–posterior (AP) translation is observed; in the flexed position where the cervical spine is kyphotic, both FE rotation and AP translation of the joints exhibit an increasing trend from top (C1–C2) to bottom (C6–C7). The two end joints (C1–C2 and C6–C7), while fitting the above-described patterns in FE rotation and AP translation, show a distinct response in SI translation: markedly greater SI displacements by C1–C2 and C6–C7 in the extended and flexed positions, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Average cervical displacements between adjacent vertebrae in three positions. (A) Average cervical displacements between adjacent vertebrae in the sagittal plane. (B) Average cervical displacements between adjacent vertebrae out of the sagittal plane. An asterisk indicates a significant difference between segment levels as assessed by two-way ANOVA. Significant differences between groups are indicated by *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01 or ***P ≤ 0.001.

Sex Differences in Cervical Intervertebral Displacement.

Some significant sex differences are observed: males show greater FE in the neutral position (P = 0.03), greater lateral bending (LB) (P = 0.03), and lateral-medial (LM) translation (P = 0.01) in the extended position than females. No significant sex difference is identified in the flexed position.

Discussion

We harnessed modern imaging and biodynamic measurement techniques with a unique experimental model and successfully captured subtle yet consistent neck musculoskeletal mechanical changes that occurred during fatiguing neck exertions. These observed changes are the most unequivocal and compelling evidence demonstrating the fatigue effect on musculoskeletal dynamics to date. They indicate a multimuscle multi-degree-of-freedom system in a statically sustained contraction would undergo a dynamic process of “loss-and-regain” of equilibrium as it experiences fatigue. When permitted, the system moves to establish its new equilibriums; even with structural support or constraints, it could deflect or deform as documented in the current study. Theoretically, this interpretation lends support to the equilibrium-point hypothesis for motor control of human movement (26) and inspires a more inclusive framework unifying dynamic and static activities, free or constrained, transitory or sustained.

A fatigued neck deflects as if it were enduring an increasing external bending moment, resulting in more kyphosis for a kyphotic cervical spine and more lordosis for a lordotic cervical spine. The actual force of exertion and FE moment were maintained constant as designed and verified by the load cell recording (Fig. 2A). We therefore can infer that the primary, if not the only, determining factor for the displacement and deflection is the “tug of war” between the agonist and antagonist neck muscles. While the agonist or antagonist roles of neck muscles are position- and exertion-dependent (13, 27) and the fatigability of individual muscles can be highly variant and complex, consistent across all three experimental conditions was the agonist muscles as a group yielding to the antagonist muscles. This means the antagonist muscles collectively are less inhibited in fatigued state and able to make more compensatory recruitment of additional motor units, resulting in a net bending moment that drives the structure to a new equilibrium.

The experimental model designed in this study provides a time-compressed “fast-forward” look into the effects of prolonged neck exertions of lower amplitude on the cervical spine. The latter type of long-term sustained exertions is not amenable to experimental tests in vivo but is a common form of “wear-and-tear” mechanical insults to musculoskeletal tissue structures leading to neck pain. Most relevant and concerning is the adverse consequence of a sustained flexed neck position as seen in prolonged use of an electronic device with a dropped head, which has been linked to the increasing prevalence of neck pain (28). A full account of the combined effects of muscular and skeletal changes on tissue mechanical loading would require subject-specific and dynamic (given the knowledge gained from the present study) biomechanical models, which are not yet available. We can nevertheless assert that fatigue causes the cervical spine of a flexed neck to become more kyphotic, further aggravating the intervertebral disc compression—a key “mechano-biomarker” for the risk of neck pain.

The middle cervical spine exhibits the greatest deflection and translation in response to fatiguing loads because the upper and lower cervical vertebrae are anchored by larger ligaments and muscles, respectively. The ligaments in the middle cervical spine segments (C2–C3, C3–C4, and C4–C5) are relatively less rigid and smaller in size (29, 30), leading to increased flexibility and reduced stability (31), as the cross-sectional area of the restraining ligaments positively correlates with stiffness and joint stability (32). In contrast, the upper cervical spine benefits from larger and stronger ligaments, such as the transverse and alar ligaments (33–35), which are dedicated to maintaining craniocervical joint stability. The presence of a few more large-size muscles attached to the lower cervical spine (36) contributes to more restrained segment mobility.

Noteworthy also is that the displacements of C1–C2 are uniquely different from the rest of segments. The negligible and insignificant displacements in FE rotation and AP translation compared with substantial and significant displacements in AR rotation and SI translation may be ascribed to the unique yet complex anatomical structure of the C1–C2 joint—the atlanto-axial joint. First, the atlanto-axial joint is formed by the dens of axis (C2) and an osteoligamentous ring of the atlas (C1) and can act as a pivot joint with its primary motion as axial rotation (AR). The relative horizontal orientation of the facet joints can facilitate and allow greater AR along the transverse plane (37, 38). As a result, the atlanto-axial joint contributes to 40 to 70% of total neck AR (38–40). In addition, the transverse ligament, the largest and strongest ligament of the upper cervical spine (33–35), running behind the dens and holding it against the anterior ring of C1, restricts flexion and anterior movement of C1 on C2, which is analogous to the seatbelt restraining a passenger in an automobile (32, 34). Therefore, these structural characteristics along with the function of the transverse ligament may result in more displacement in AR than in FE rotation or AP translation. However, this does not explain why C1 exhibited greater and significant displacement in inferior direction, especially during flexion exertions (positions A & B). Given that large AR displacements have been observed in this study, a plausible explanation is that the AR might initiate the coupled translations in the inferior direction—this seems consistent with findings from studies of the upper cervical spine motion (41–43).

Materials and Methods

Subjects.

Data from 24 healthy subjects (11 males, 13 females, aged 21 to 45) were analyzed in this study. All subjects were in good health at the time of participation and did not have any prior history of neck injury or disorders. The experiment protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of University of Pittsburgh (where the experiments were conducted), and all subjects provided written informed consent.

Experiment.

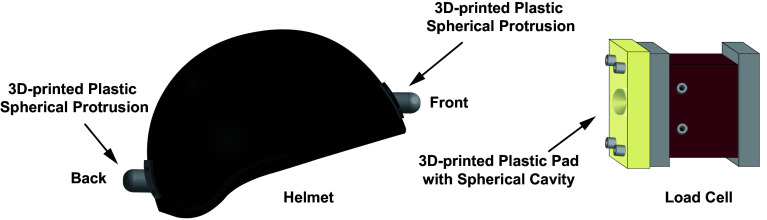

Subjects performed isometric sustained-till-exhaustion head–neck exertions at 50% of their strengths in anterior, anterior-superior, and posterior-superior directions with three different positions: neutral, 40° extended, and 40° flexed, respectively (Fig. 4). The strengths (i.e., 100%) were assessed in maximum voluntary contractions trials, and the individual- and position-specific exertion level of 50% was displayed as real-time feedback to the subjects as well as the experimenters. Also displayed and monitored real-time was the head–neck FE angle, defined as the angle between the Frankfurt plane and the horizontal plane. The exertion tasks required subjects to press their heads with the augmented helmet (Dennis Kirk, Inc., USA) against a triaxial load cell (FUTEK Advanced Sensor Technology, Inc., Irvine, CA) while seated with their torso restrained by straps (Figs. 4 and 5). Additional details of the experimental design can be found in prior publications (44, 45). Two dynamic stereo-radiography “snap-shots” were taken during sustained exertion tasks, one at the beginning of the exertion and another when the subject signaled the exhaustion and termination of the exertion. Each exertion was repeated once. The order of all trials including the exertions and their repetitions performed by each subject was randomized. Sufficient intertrial rest of at least twice the duration of the prior trial was provided to allow the full recovery.

Fig. 4.

Three experimental conditions in which three head–neck postures were assumed to make sustained-till-exhaustion isometric exertions. The four markers placed on tragion notches (Left and Right) and inferior border of each orbit (Left and Right) define the Frankfurt plane which is used to describe the head orientation and exertion direction.

Fig. 5.

Helmet with 3D-printed plastic spherical protrusions (Left), and load cell attached with 3D-printed plastic pad with spherical cavity (Right).

Dynamic Stereo-Radiography (DSX) Imaging of the Cervical Spine In Vivo.

The DSX system consisted of two cardiac-cine angiography generators (EMD Technologies, CPX-3100CV), two X-ray tubes with 0.3/0.6 mm focal spot, two 16-in Thalus image intensifiers, and two high-speed digital cameras (4-megapixels Phantom v10, Vision Research). Cervical spine region was imaged at 30 frames per second for 0.1 s for each “snap-shot” (X-ray parameters: excitation voltage = 70 kV, current = 160 mA, pulsed exposure time = 2.5 ms, source-to-subject distance 180 cm).

CT Imaging.

High-resolution CT scans of the subjects’ neck region (from C1 to T1) were obtained from a clinical CT facility (GE Medical Systems Lightspeed Pro 16, Waukesha, WI) at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC). The CT scans were segmented in Mimics 20.0 (Materialise Inc., Ann Arbor, MI) to create three-dimensional (3D) vertebral bone models.

Surface EMG and Muscle Fatigue Assessment.

EMG data were collected using a Wave Wireless EMG System (formerly known as ZeroWire system; Cometa srl, Milan, Italy), with a band-pass filter of 10 to 500 Hz and sampling frequency of 2,160 Hz, from four pairs of major neck muscles, two flexors and two extensors: the sternocleidomastoids (SCM), infrahyoid (Hyoids), trapezius (Trap) at C4–C5 level, and splenius capitis (SPL). The skin surface areas were shaved and cleaned with isopropyl alcohol prior to the placement of the electrodes. The raw EMG signals were first processed using a band-pass filter of 10 to 500 Hz and a notch filter at 60 Hz and its aliases to remove low- and high-frequency noise as well as power line interference. A fast Fourier transform (FFT) was then applied to the filtered EMG data, and the median frequency (MF) was then determined through a moving average window of 0.5 s. A linear regression was applied to the MF at every 5-s time interval for each muscle for each sustained exertion. The estimated slope of the linear regression was used to assess the development of muscle fatigue.

Model-Based Tracking of 3D Cervical Vertebral Bone Kinematics.

The 3D cervical vertebral kinematics were determined using a previously validated model-based tracking technique (22, 23, 46, 47). Briefly, digitally reconstructed radiographs (DRRs) of the CT-acquired 3D vertebra model were created through ray tracing and then placed within a virtual imaging system that was proportionally and configurationally identical to the actual experimental setup (Fig. 6). The correlation between the DRRs and DSX images was maximized using a volumetric image-matching algorithm to ascertain the 3D position and orientation of the vertebra for each frame. This tracking process was repeated for each individual cervical vertebra.

Fig. 6.

Volumetric model-based tracking of the DSX recordings to determine 3D cervical vertebral kinematics.

Computation of Cervical Vertebra Displacement.

An anatomical coordinate system (ACS) was defined on each vertebra with its three orthogonal axes following the right-hand rule and located at the centroid of the 8 fiducial markers that were consistently identified on the superior and inferior surfaces of a vertebral body (Fig. 7A) (48). The 3D kinematics of the superior vertebra (S) were determined with respect to the inferior vertebra (I) by applying the Euler principle, consisting of three rotations—flexion–extension (FE), AR, and LB, and three translations—medial–lateral (LM), superior–inferior (SI), and AP translations (Fig. 7B). The 3D cervical vertebra displacement during a fatiguing sustained exertion was calculated as the kinematic difference between two time points compared.

Fig. 7.

(A) An anatomical coordinate system (ACS) was established on each vertebra based on 8 bone surface landmarks. (B) ACSs on two adjacent vertebrae defined the intervertebral displacements.

Statistical Analyses.

Data from two repetitions were averaged into a single dataset. The slopes of MF of the SEMG data were obtained for all measured muscles during sustained exertion tasks in all three positions and compared using Student’s t tests to detect whether the slopes were less than zero. The 3D cervical vertebral displacements during sustained exertion tasks in all three positions were examined using Student’s t tests to detect whether the displacements were different from zero. A two-way ANOVA was performed to identify sex and segmental (C1–C2 to C6–C7) differences in 3D cervical vertebral displacements. Whenever a significant main or interaction effect was identified, post hoc Tukey’s honest significant difference tests would follow to examine differences between the 3D vertebral displacements. All analyses were carried out using R statistical software.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a research grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (Grant No. R01OH010587). Technical assistances provided by Dr. William Anderst of Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Dr. Chan-Hong Moon of Department of Radiology at University of Pittsburgh Medical Center are acknowledged.

Author contributions

X.Z. designed research; Y.Z., C.R., and X.Z. performed research; Y.Z., C.R., and X.Z. analyzed data; and Y.Z., C.R., and X.Z. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All study data are included in the main text.

References

- 1.Enoka R. M., Duchateau J., Muscle fatigue: What, why and how it influences muscle function. J. Physiol. 586, 11–23 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mannion A. F., Dolan P., Electromyographic median frequency changes during isometric contraction of the back extensors to fatigue. Spine 19, 1223–1229 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nordez A., et al. , Assessment of muscle hardness changes induced by a submaximal fatiguing isometric contraction. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 19, 484–491 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Brien P., Potvin J., Fatigue-related EMG responses of trunk muscles to a prolonged, isometric twist exertion. Clin. Biomech. 12, 306–313 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Troiano A., et al. , Assessment of force and fatigue in isometric contractions of the upper trapezius muscle by surface EMG signal and perceived exertion scale. Gait Posture 28, 179–186 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cifrek M., et al. , Surface EMG based muscle fatigue evaluation in biomechanics. Clin. Biomech. 24, 327–340 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.González-Izal M., et al. , Electromyographic models to assess muscle fatigue. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 22, 501–512 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hagg G., Interpretation of EMG spectral alterations and alteration indexes at sustained contraction. J. Appl. Physiol. 73, 1211–1217 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jørgensen K., et al. , Electromyography and fatigue during prolonged, low-level static contractions. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 57, 316–321 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lowery M., Nolan P., O’malley M., Electromyogram median frequency, spectral compression and muscle fibre conduction velocity during sustained sub-maximal contraction of the brachioradialis muscle. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 12, 111–118 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vøllestad N. K., Measurement of human muscle fatigue. J. Neurosci. Methods 74, 219–227 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshitake Y., et al. , Assessment of lower-back muscle fatigue using electromyography, mechanomyography, and near-infrared spectroscopy. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 84, 174–179 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thelen D., Schultz A., Ashton-Miller J., Co-contraction of lumbar muscles during the development of time-varying triaxial moments. J. Orthop. Res. 13, 390–398 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ebenbichler G., et al. , The role of the biarticular agonist and cocontracting antagonist pair in isometric muscle fatigue. Muscle Nerve 21, 1706–1713 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernandez-de-las-Penas C., et al. , Cervical muscle co-activation in isometric contractions is enhanced in chronic tension-type headache patients. Cephalalgia 28, 744–751 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gagnon D., et al. , Cocontraction changes in muscular fatigue at different levels of isometric contraction. Int. J. Ind. Ergonomics 9, 343–348 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milner T. E., et al. , Inability to activate muscles maximally during cocontraction and the effect on joint stiffness. Exp. Brain Res. 107, 293–305 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Potvin J., O’brien P., Trunk muscle co-contraction increases during fatiguing, isometric, lateral bend exertions: Possible implications for spine stability. Spine 23, 774–780 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Psek J.-A., Cafarelli E., Behavior of coactive muscles during fatigue. J. Appl. Physiol. 74, 170–175 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hollman J. H., et al. , Effects of hip extensor fatigue on lower extremity kinematics during a jump-landing task in women: A controlled laboratory study. Clin. Biomech. 27, 903–909 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niederer D., et al. , Local muscle fatigue and 3D kinematics of the cervical spine in healthy subjects. J. Motor Behav. 48, 155–163 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderst W., et al. , Validation of a non-invasive technique to precisely measure in vivo three-dimensional cervical spine movement. Spine 36, E393 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bey M. J., et al. , Validation of a new model-based tracking technique for measuring three-dimensional, in vivo glenohumeral joint kinematics. J. Biomech. Eng. 128, 604–609 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miranda D. L., et al. , Kinematic differences between optical motion capture and biplanar videoradiography during a jump–cut maneuver. J. Biomech. 46, 567–573 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moxham J., et al. , Changes in EMG power spectrum (high-to-low ratio) with force fatigue in humans. J. Appl. Physiol. 53, 1094–1099 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feldman A., Once more on the equifibrium-point hypothesis for motor control. J. Motor Behav. 18, 17–54 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng C.-H., Lin K.-H., Wang J.-L., Co-contraction of cervical muscles during sagittal and coronal neck motions at different movement speeds. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 103, 647–654 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Povolotskiy R., et al. , Head and neck injuries associated with cell phone use. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 146, 122–127 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panjabi M., Oxland T., Parks E., Quantitative anatomy of cervical ligaments. Part II. Middle and lower cervical spine. J. Spinal Disord. 4, 276–285 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang X. D., Feng M. S., Hu Y. C., Establishment and finite element analysis of a three-dimensional dynamic model of upper cervical spine instability. Orthop. Surg. 11, 500–509 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderst W., et al. , Three-dimensional intervertebral kinematics in the healthy young adult cervical spine during dynamic functional loading. J. Biomech. 48, 1286–1293 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Panjabi M. M., Oxland T. R., Parks E. H., Quantitative anatomy of cervical spine ligaments. Part I. Upper cervical spine. J. Spinal Disord. 4, 270–276 (1991). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dickman C. A., et al. , Magnetic resonance imaging of the transverse atlantal ligament for the evaluation of atlantoaxial instability. J. Neurosurg. 75, 221–227 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dvorak J., et al. , Biomechanics of the craniocervical region: The alar and transverse ligaments. J. Orthop. Res. 6, 452–461 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Panjabi M. M., et al. , The mechanical properties of human alar and transverse ligaments at slow and fast extension rates. Clin. Biomech. 13, 112–120 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kamibayashi L. K., Richmond F. J., Morphometry of human neck muscles. Spine 23, 1314–1323 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chowdhury S. K., et al. , Lumbar facet joint kinematics and load effects during dynamic lifting. Hum. Factors 60, 1130–1145 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roche C. J., et al. , The atlanto-axial joint: Physiological range of rotation on MRI and CT. Clin. Radiol. 57, 103–108 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goto S., et al. , Three-dimensional motion of the upper cervical spine in rheumatoid arthritis. Spine 19, 272–276 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.White A. A. III, Panjabi M. M., The basic kinematics of the human spine: A review of past and current knowledge. Spine 3, 12–20 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderst W., et al. , Dynamic in vivo 3D atlantoaxial spine kinematics during upright rotation. J. Biomech. 60, 110–115 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ishii T., et al. , Kinematics of the upper cervical spine in rotation: In vivo three-dimensional analysis. Spine 29, E139–E144 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salem W., et al. , In vivo three-dimensional kinematics of the cervical spine during maximal axial rotation. Man. Ther. 18, 339–344 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chowdhury S. K., et al. , “Integrating multi-modality imaging and biodynamic measurements for studying neck biomechanics during sustained-till-exhaustion neck exertions” in Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting (SAGE Publications Sage CA, Los Angeles, CA, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou Y., et al. , A state-of-the-art integrative approach to studying neck biomechanics in vivo. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 63, 1235–1246 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anderst W., et al. , Six-degrees-of-freedom cervical spine range of motion during dynamic flexion-extension after single-level anterior arthrodesis: Comparison with asymptomatic control subjects. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 95, 497 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anderst W., et al. , Validation of three-dimensional model-based tibio-femoral tracking during running. Med. Eng. Phys. 31, 10–16 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Panjabi M. M., et al. , Mechanical properties of the human cervical spine as shown by three-dimensional load–displacement curves. Spine 26, 2692–2700 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the main text.