Abstract

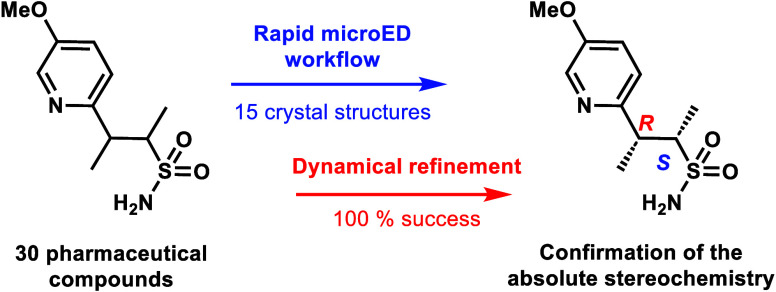

Microcrystal electron diffraction (microED) is an emerging technique for rapid crystallographic analysis of small molecule micro- and nanocrystals. In this report, we evaluate the applicability of microED to pharmaceutical compounds through the analysis of 30 samples obtained from the process and medicinal chemistry groups at Amgen Inc. Using only 40 h of microscope time, 15 of 30 crystal structures were elucidated. From these crystal structures, all chiral compounds had the correct absolute stereochemistry assigned by dynamical refinement of continuous rotation electron diffraction data, confirming dynamical refinement as a promising tool for the absolute stereochemistry determination of pharmaceutically relevant compounds.

Structural determination of a drug substance and its intermediates is critical for pharmaceutical research to assign the composition and molecular connectivity of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). Depending on the molecular complexity, state-of-the-art spectroscopic techniques such as nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) can be time-consuming and may lead to ambiguous structural assignments.1 Single crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) can provide three-dimensional structural information and absolute stereochemistry for the compound of interest; however, this technique can be limited by the ability to grow crystals of sufficient quality and size2 or by weak anomalous scattering effects in organic structures.3 Thus, developing an analytical technique capable of fast structural elucidation of pharmaceutically relevant compounds can lead to a significant reduction in time and costs associated with the drug discovery process.

Recently, microcrystal electron diffraction (microED) has increased in use as a crystallographic technique capable of the structural determination of micro- or nanocrystals. This technique has been applied for the structural elucidation of a wide range of chemicals, including proteins, materials, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), small organic molecules, complex natural products, and organometallic species.4−7 MicroED utilizes crystals smaller than those suitable for SCXRD. Samples isolated by preparative crystallizations or “seemingly amorphous” powders obtained from chromatography can be used, thereby avoiding lengthy crystallization experiments typically necessary for SCXRD.8 MicroED can also detect different polymorphs and crystalline impurities in the nanomolar regime, which can offer important applications for drug discovery.9

As approximately 50% of small molecule drugs recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are chiral,10,11 the determination of the absolute stereochemistry of an API is an essential step for drug discovery and development. For microED diffraction data, stereochemical elucidation has been largely limited to molecules obtained from biological feedstocks, or to those cocrystallized with a chiral compound of known stereochemistry.12−14 Typically, microED data is processed and refined using a kinematical approach, where diffraction intensities are treated without considering multiple scattering events that occur between the electron beam and the crystal.14,15

By taking into consideration multiple scattering events during microED data processing and refinement, Palatinus et al. reported the determination of the crystal structure and absolute stereochemistry of a pharmaceutical cocrystal of sofosbuvir and l-proline. More recently, the absolute stereochemistry of a small subset of microED structures has been elucidated by dynamical refinement.14−19 While most of the previously referenced examples provide a foundation for the pharmaceutical use of microED, in this study, we sought to evaluate microED using real-world samples from a large pharmaceutical company, providing practical insight into the performance of structure elucidation and absolute stereochemistry determination by this method.

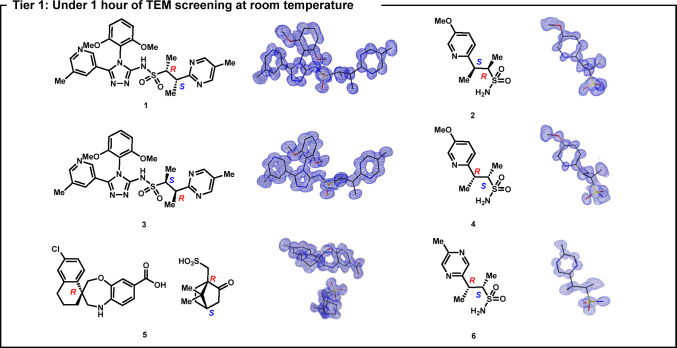

Thirty powders obtained from process and medicinal chemistry groups at Amgen Inc. were chosen as the subject of the study. Our workflow was divided into three tiers: In the first tier, 30 powder samples were screened for diffraction in a TEM at room temperature with microscope time limited to 1 h per sample (Figure 1). The diffraction data sets were processed by using an in-house script to automatically process and index the data sets with XDS software (Supporting Information, section 7),20 and structures were initially solved with SHELXT or SHELXD software using kinematical approaches (SI, section 8).21−23 Six crystal structures (compounds 1–6) were obtained directly in this screening tier, although compound 5 exhibited rotational disorder in the camphorsulfonate motif, at this temperature (compound 5.1, Figure S4, Table S3).

Figure 1.

Structures solved by microED where a preliminary solution was obtained in under 1 h each. Partial view of the asymmetric unit shown for samples 1 and 3 (Z′ = 2). Hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity.

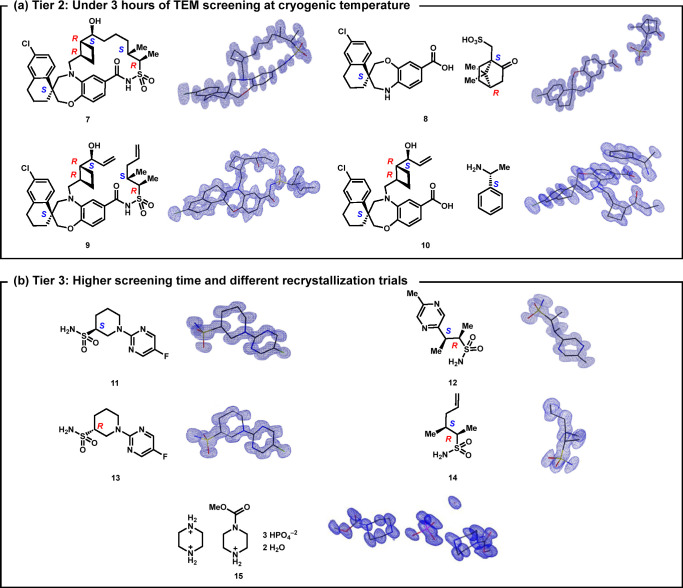

In tier 2, data were collected from samples 7–10 that displayed diffraction patterns consistent with single crystals but were beam-sensitive at room temperature (Figure 2a). In this tier, TEM time was limited to 3 h per sample, and data were collected at cryogenic temperature (80 K). Here, cryogenic temperatures reduced crystallographic disorder and radiation degradation, enabling structural assignment (SI, section 4). In tier 3 of this workflow, samples that were notably polycrystalline had poor diffraction resolution, or provided no diffraction at cryogenic temperatures (Figure 2b). These samples underwent crystallization screenings, where the crystal structures of samples 11–15 were elucidated (SI, section 5).

Figure 2.

Structures solved by microED where a preliminary solution was obtained (a) at cryogenic temperatures and in under 3 h each and (b) by extensive screening time and recrystallization trials. Partial view of the asymmetric unit shown for samples 7 (Z′ = 2), 11, 13, and 15 (Z′ = 4). Hydrogen atoms omitted for clarity.

Overall, for the kinematical approach, structural elucidation for 15 of 30 samples was obtained using approximately 40 h of TEM time and approximately 70 h of automated data processing using an in-house python script and user-driven crystal structure refinement. The remaining 15 compounds failed to produce structures within 3 h of TEM time per sample and/or after recrystallization attempts. These samples consisted of three enantiomeric pairs and nine chiral proteolysis targeting chimera (PROTACs) molecules (Figure S1).

Of the 15 crystal structures obtained in the initial three-tier structural determination stage, 14 samples were chiral and enantioenriched, and dynamical refinement was used for the confirmation of the absolute stereochemistry of these compounds. Data sets with the best overall statistics (completeness higher than 65%, Robs lower than 30%, resolution better than 1.1 Å, and Pearson correlation coefficient (CC1/2) higher than 97% (Table S5)) were reprocessed with Pets2.0 software to generate new kinematical and dynamical reflection files.24 When possible, the kinematical solution of the crystal structures was obtained and refined using the single diffraction data set with SHELXT22 within the Jana2020 suite.25 Otherwise, the crystallographic information file (CIF) was imported and refined against the reflection file obtained with Pets2.0 software. Dynamical refinement was performed by refining the crystal structure against the dynamic reflection file. The crystal structure was then inverted and refined against the same reflection file (SI, sections 8–11). To find the correct enantiomer, values of the residual-factor after refinement (Robs, wRobs, Rall, and wRall, Table S6) for both enantiomeric forms were compared. The enantiomer with lower values is assigned as the correct one while a higher value of R factors indicates the incorrect enantiomer.14

The absolute configuration of all compounds presented in this work was previously determined by Amgen Inc. (Table S1), and in some cases, SCXRD was used to unambiguously assign the correct stereochemistry of the compounds, for structural comparison, and for confirmation of previous findings (SI, Section 12). Overall, dynamical refinement confirmed the assignment of the correct enantiomer with an R factor difference between incorrect and correct enantiomers higher than 0.7% (Table S6) and high confidence levels (Table S7). Sample 8 had a low confidence level in comparison with the other samples (0.2σ); however, high ΔwRall (2.2%) indicates the assignment of the correct enantiomer (Table 1).

Table 1. Results for the Structural and Absolute Stereochemistry Determination for the Samples in the First Tier (1–6), Second Tier (7–10), and Third Tier (11–15)a.

| initial structural determination |

dynamical refinement |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sample | conditions | data sets collected | data sets merged | interatomic coordinates | ΔwRall | z score | computing time | total experimental time | SC-XRD | Flack parameter |

| 1 | <1 h screening, room temperature, no recrystallization | 6 | 3 | free all | 3.40% | 12.1σ | 18 h | 19 h | yes | 0.006(11) |

| 2 | 9 | 1 | free all | 2.10% | 4.3σ | 1 h | 2 h | |||

| 3 | 4 | 2 | free all | 2.30% | 7.3σ | 16 h | 17 h | yes | –0.010(16) | |

| 4 | 4 | 1 | free all | 0.90% | 4.2σ | 1 h | 2 h | |||

| 5 | 9 | 2 | partially fixed | 2.80% | 7.7σ | 2 h | 3 h | |||

| 6 | 1 | 1 | free all | 2.00% | 5.5σ | 1 h | 2 h | yes | 0.05(7) | |

| 7 | <3 h screening, 80 K, no recrystallization | 8 | 3 | free all | 2.20% | 7.8σ | 10 h | 13 h | ||

| 8 | 10 | 3 | fixed all | 2.20% | 0.2σ | 6 h | 9 h | |||

| 9 | 8 | 2 | free all | 5.60% | 19.3σ | 16 h | 19 h | |||

| 10 | 12 | 3 | free all | 1.70% | 4.6σ | 8 h | 11 h | |||

| 11 | <3 h screening, 80 K, different recrystallization conditions | 22 | 2 | fixed all | 2.50% | 7.0σ | 44 h | 47 h | ||

| 12b* | 8 | 2 | free all | 2.60% | 4.5σ | 20 min | +3.5 h | |||

| 13 | 18 | 2 | free all | 3.50% | 19.0σ | 44 h | 47 h | |||

| 14 | 5 | 2 | partially fixed | 2.20% | 2.6σ | 20 min | 3.5 h | yes | –0.05(25) | |

| 15 | 6 | 4 | 3 h | |||||||

ΔwRall is the wRall difference between the wrong and correct enantiomers. Confidence levels (z score) indicate the probability that one enantiomer better fits the experimental data. Samples 1–14 are chiral, and sample 15 is achiral.

Sample 12 required more than 3 h of screening time to obtain a suitable crystal structure. Total experimental time does not consider user-driven data processing.

Dynamical refinement served as a tool to confirm the correct enantiomer from a single diffraction data set for each sample by refining the crystal structures with isotropic atoms or with fixed atomic coordinates. Due to the poor quality of some diffraction data sets, the final solution after refinement had interatomic bonds breaking or the presence of nonpositive definite atoms (NPD). Merging multiple diffraction data sets or carefully collecting higher quality single data sets will likely provide a better dynamical solution but is not required to correctly assign absolute stereochemistry. Here, the crystal structures were not refined to standards common to SCXRD. The purpose of this work was to simulate the use of microED in a pharmaceutical setting where structural elucidation or dynamical refinement is used to answer a question. Thus, structural elucidation does not necessitate full adherence to crystallographic refinement standards. In this work, data processing and refinement utilizing a dynamical approach was standardized to be performed in computers with the same computing capacity. Depending on the molecular complexity, refinement took between 20 min and 44 h of total computing time per sample, including the dynamical refinement of both enantiomers.

A typical range between 2 h and 2 days per sample is required for microED data collection, processing, analysis, and dynamical refinement for absolute stereochemistry confirmation. In the rapid screening stage (tier 1), crystal structures were obtained without recrystallization, and we were able to assign the correct enantiomer in 2 h (samples 2, 4, and 6, Table 1). Although the large computing time for dynamical refinement in some of the samples might still prevent it from being a high throughput methodology, it represents a significant time and resource savings for samples where it is difficult to grow large and high-quality single crystals for SCRXD determination.

In this study, we evaluated the practicality of microED as a tool to routinely determine crystal structures of pharmaceutically relevant compounds, as well as their absolute stereochemistry assignment. Thirty pharmaceutical samples were selected for evaluation, spanning a range of chemical complexity from both medicinal and process chemistry sectors, from Amgen Inc. Crystal structures of half of the compounds analyzed were solved from data sets collected directly from powders obtained following routine purification and no recrystallization steps, by adjusting the temperature conditions under which samples were measured or by recrystallization of the samples. Moreover, absolute stereochemistry was confirmed by dynamical refinement for all 14 chiral samples, highlighting dynamical refinement as a promising tool for enantiomeric assignment of micro- and nanosized crystals analyzed by microED. The speed and minimal sample preparation required for structural determination demonstrate that microED, in combination with dynamical refinement, can be used as routine analytical tools for absolute structural elucidation in the pharmaceutical pipeline.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Lukas Palatinus (Institute of Physics of the Czech Academy of Sciences) for training us on Pets2.0 and Jana2020 software and for the countless correspondence about dynamical refinement. At the California Institute of Technology, we also thank Dr. Michael K. Takase for single-crystal X-ray diffraction data collection and Dr. Songye Chen and Welison B. Floriano from the cryo-EM facility for computer access.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- microED

microcrystal electron diffraction

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- SCXRD

single-crystal X-ray diffraction

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- API

active pharmaceutical ingredient

- CIF

crystallographic information file

- NPD

nonpositive definite

- CS

camphorsulfonate

- PEA

1-phenylethan-1-aminium

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- PROTAC

proteolysis targeting chimera

- CC1/2

Pearson correlation coefficient.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.orglett.4c01865.

Materials, available instruments for microED, electron diffraction experiment, room temperature TEM screening procedure, cryogenic TEM screening, additional screening and recrystallization of samples, transmission electron microscope images of crystals, automated data processing procedure, data processing for the kinematical approach, data processing for the dynamical approach, kinematical and dynamical refinement with Jana2020, dynamical refinement results, single crystal X-ray diffraction, and references (PDF)

Author Present Address

# Current address: Sanofi, 350 Water St., Cambridge, MA 02141. E-mail: shawn.walker@sanofi.com

Author Present Address

∇ Current address: Hexagon Bio, 1490 O’Brien Dr., Suite E, Menlo Park, CA 94025. E-mail: vcee@hexagonbio.com

Author Present Address

○ Current address: Loxo@Lilly, 600 Tech Ct., Louisville, CO 80027. E-mail: asmith@loxooncology.com

Author Contributions

H.M.N. and K.Q. conceived the idea and supervised the project. J.E.B. performed microED data collection and analyzed the data. L.S.M. performed dynamical refinement, absolute structure determination, and SCXRD. J.A.R., D.A.D, I.H.R., and H.M.N. performed data analysis. The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors.

Author Contributions

⧫ These authors contributed equally.

Financial support for this work was generously provided by the David and Lucile Packard Foundation (to H.M.N. and J.A.R.), the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation (to J.A.R.), the National Science Foundation (DGE-1650604 to J.E.B. and CCI Center for Computer Assisted Synthesis CHE-2202693 to H.M.N.), and the Amgen Process Development Academic Interface Team. I.H.R. is supported by an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship under grant 2139433.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): J.E.B., H.M.N., J.A.R., and D.G. are founders of MicroEDLab.com, a for-profit contract research organization providing electron microscopy structural solutions.

Supplementary Material

References

- Hodgkinson P. NMR Crystallography of Molecular Organics. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2020, 118–119, 10–53. 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2020.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunitz J. D.X-Ray Analysis and the Structure of Organic Molecules; Verlag: Zürich, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Flack H. D.; Bernardinelli G. The Use of X-Ray Crystallography to Determine Absolute Configuration. Chirality 2008, 20 (5), 681–690. 10.1002/chir.20473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C. G.; Martynowycz M. W.; Hattne J.; Fulton T. J.; Stoltz B. M.; Rodriguez J. A.; Nelson H. M.; Gonen T. The CryoEM Method MicroED as a Powerful Tool for Small Molecule Structure Determination. ACS Cent. Sci. 2018, 4 (11), 1587–1592. 10.1021/acscentsci.8b00760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clabbers M. T. B.; Xu H. Microcrystal Electron Diffraction in Macromolecular and Pharmaceutical Structure Determination. Drug Discovery Today Technol. 2020, 37, 93–105. 10.1016/j.ddtec.2020.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danelius E.; Patel K.; Gonzalez B.; Gonen T. MicroED in Drug Discovery. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2023, 79, 102549. 10.1016/j.sbi.2023.102549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemmi M.; Mugnaioli E.; Gorelik T. E.; Kolb U.; Palatinus L.; Boullay P.; Hovmöller S.; Abrahams J. P. 3D Electron Diffraction: The Nanocrystallography Revolution. ACS Cent. Sci. 2019, 5 (8), 1315–1329. 10.1021/acscentsci.9b00394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson Grape E.; Rooth V.; Nero M.; Willhammar T.; Inge A. K. Structure of the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient Bismuth Subsalicylate. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13 (1), 1984. 10.1038/s41467-022-29566-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyano T.; Hirakawa Y.; Yamano A.; Ueda H. Microelectron Diffraction Reveals Contamination of Polymorphs by Structure Analysis of Microscale Crystals in a Novel Pharmaceutical Cocrystal. Cryst. Growth Des. 2023, 23 (11), 7706–7715. 10.1021/acs.cgd.3c00468. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chuong P.-H.; Nguyen L. A.; He H. Chiral Drugs: An Overview. Int. J. Biomed. Sci. 2006, 2 (2), 85–100. 10.59566/IJBS.2006.2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceramella J.; Iacopetta D.; Franchini A.; De Luca M.; Saturnino C.; Andreu I.; Sinicropi M. S.; Catalano A. A Look at the Importance of Chirality in Drug Activity: Some Significative Examples. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12 (21), 10909. 10.3390/app122110909. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shah H. S.; Yuan J.; Xie T.; Yang Z.; Chang C.; Greenwell C.; Zeng Q.; Sun G.; Read B. N.; Wilson T. S.; Valle H. U.; Kuang S.; Wang J.; Sekharan S.; Bruhn J. F. Absolute Configuration Determination of Chiral API Molecules by MicroED Analysis of Cocrystal Powders Formed Based on Cocrystal Propensity Prediction Calculations. Chem. – Eur. J. 2023, 29 (14), e202203970. 10.1002/chem.202203970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B.; Bruhn J. F.; Weldeab A.; Wilson T. S.; McGilvray P. T.; Mashore M.; Song Q.; Scapin G.; Lin Y. Absolute Configuration Determination of Pharmaceutical Crystalline Powders by MicroED via Chiral Salt Formation. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58 (30), 4711–4714. 10.1039/D2CC00221C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brázda P.; Palatinus L.; Babor M. Electron Diffraction Determines Molecular Absolute Configuration in a Pharmaceutical Nanocrystal. Science 2019, 364 (6441), 667–669. 10.1126/science.aaw2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klar P. B.; Krysiak Y.; Xu H.; Steciuk G.; Cho J.; Zou X.; Palatinus L. Accurate Structure Models and Absolute Configuration Determination Using Dynamical Effects in Continuous-Rotation 3D Electron Diffraction Data. Nat. Chem. 2023, 15, 848. 10.1038/s41557-023-01186-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jandl C.; Steinfeld G.; Li K.; Pang P. K. C.; Choi C. L.; Wang C.; Simoncic P.; Williams I. D. Absolute Structure Determination of Chiral Zinc Tartrate MOFs by 3D Electron Diffraction. Symmetry 2023, 15 (5), 983. 10.3390/sym15050983. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simoncic P.; Romeijn E.; Hovestreydt E.; Steinfeld G.; Santiso-Quiñones G.; Merkelbach J. Electron Crystallography and Dedicated Electron-Diffraction Instrumentation. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. E Crystallogr. Commun. 2023, 79 (5), 410–422. 10.1107/S2056989023003109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decato D.; Palatinus L.; Stierle A.; Stierle D. Absolute Structure Determination of Berkecoumarin by X-Ray and Electron Diffraction. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Struct. Chem. 2024, 80 (5), 143–147. 10.1107/S2053229624003061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurung K.; Šimek P.; Jegorov A.; Palatinus L. Structure and Absolute Configuration of Natural Fungal Product Beauveriolide I, Isolated from Cordyceps Javanica, Determined by 3D Electron Diffraction. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Struct. Chem. 2024, 80 (3), 56–61. 10.1107/S2053229624001359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W. XDS. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010, 66 (2), 125–132. 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M. A. Short History of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. A 2008, 64 (1), 112–122. 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M. SHELXT – Integrated Space-Group and Crystal-Structure Determination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. Found. Adv. 2015, 71 (1), 3–8. 10.1107/S2053273314026370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M. Crystal Structure Refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Struct. Chem. 2015, 71 (1), 3–8. 10.1107/S2053229614024218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palatinus L.; Brázda P.; Jelínek M.; Hrdá J.; Steciuk G.; Klementová M. Specifics of the Data Processing of Precession Electron Diffraction Tomography Data and Their Implementation in the Program PETS2.0. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B Struct. Sci. Cryst. Eng. Mater. 2019, 75 (4), 512–522. 10.1107/S2052520619007534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petříček V.; Palatinus L.; Plášil J.; Dušek M. Jana2020 – a New Version of the Crystallographic Computing System Jana. Z. Für Krist. - Cryst. Mater. 2023, 238 (7-8), 271. 10.1515/zkri-2023-0005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.