Abstract

In the mammalian central nervous system, slow inhibitory neurotransmission is largely mediated by metabotropic GABAB receptors (where GABA stands for γ-aminobutyric acid), which belong to the G-protein-coupled receptor gene family. Functional GABAB receptors are assembled from two subunits GABAB(1) (GABAB receptor subtype 1) and GABAB(2). For the GABAB(1) subunit, which binds the neurotransmitter GABA, two variants GABAB(1a) (GABAB receptor subtype 1 variant a) and GABAB(1b) have been identified. They differ at the very N-terminus of their large glycosylated ECD (extracellular domain). To simplify the structural characterization, we designed truncated GABAB(1) receptors to identify the minimal functional domain which still binds a competitive radioligand and leads to a functional, GABA-responding receptor when co-expressed with GABAB(2). We show that it is necessary to include all the portion of the ECD encoded by exon 6 to exon 14. Furthermore, we studied mutant GABAB(1b) receptors, in which single or all potential N-glycosylation sites are removed. The absence of oligosaccharides does not impair receptor function, suggesting that the unglycosylated ECD of GABAB(1) can be used for further functional or structural investigations.

Keywords: fluorescence, GABAB(1b) receptor, G-protein-coupled receptor, ligand-binding domain, minimal functional domain, mutagenesis

Abbreviations: ECD, extracellular domain; EGFP, enhanced green fluorescence protein; fura 2/AM, fura 2 acetoxymethyl ester; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; GABAB(1), GABAB receptor subtype 1; GABAB(1a), GABAB receptor subtype 1 variant a; GABAB(1b)Δglyc, unglycosylated GABAB(1b); GPCR, G-protein-coupled receptor; HEK-293 cells, human embryonic kidney 293 cells; mGluR1, metabotropic glutamate receptor 1; PBP, periplasmic binding protein; PLC, phospholipase C; for brevity, the single-letter system for amino acids has been used, N292, for example means Asn292

INTRODUCTION

The complex process of neural transmission in the mammalian central nervous system is mainly mediated by glutamate and GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid), which are both capable of binding to a range of receptors. Glutamate acts as the major excitatory neurotransmitter, whereas GABA acts to inhibit neurotransmission. Activation of the metabotropic GABAB receptor mediates the slow component of neuronal inhibition in most neurons. They are broadly expressed in the central nervous system and have been implicated in a variety of neurological and psychiatric disorders (see [1] for a review). GABAB receptors belong to the GPCR (G-protein-coupled receptor) gene family, which form the largest class of cell surface receptors representing approx. 1% of the human genome.

GPCRs are involved in the regulation of a large variety of physiological functions and provide huge potential as drug targets. They are activated by a wide range of ligands, ranging from hormones and peptides to light photons. Activation is supposed to induce conformational changes within the transmembrane region thus allowing signal transduction to the intracellular coupled G-protein. The metabotropic GABAB and glutamate receptors have been classified, according to sequence, as members of the family 3 GPCRs that also contain the calcium sensing receptor, sweet and amino acid taste receptors and a group of putative pheromone receptors. Family 3 receptors have a characteristic large N-terminal ECD (extracellular domain), which, in most cases, is responsible for ligand binding.

The means by which signal transduction takes place is, as yet, far from clear. There is now a growing body of evidence to suggest that GPCRs function as dimers or oligomers. Studies of the GABAB receptor that functions as a heterodimer of two related subunits, GABAB(1) (GABAB receptor subtype 1) and GABAB(2) [2–5] provided much of the initial evidence for dimerization of GPCRs. The GABAB(1)ECD is responsible for ligand binding, whereas GABAB(2) appears to be important for surface trafficking and G-protein coupling [6–12]. Whereas GABAB functions only as a heterodimer, other GPCRs are known to function as homodimers and there is also evidence that receptors can form heterodimers with a variety of GPCR partners, resulting in a modulation of receptor properties, such as with the opioid receptors [13].

The ECDs of family 3 GPCRs were predicted to show structural homology to PBPs (periplasmic binding proteins) of Gram-negative bacteria [14]. PBPs are located between the two outer lipid membranes and bind a spectrum of substrates, which may serve either as nutrients or to initiate chemotaxis. Structural homology was verified with the recent crystal structure determination of the ECD of the mGluR1 (metabotropic glutamate receptor 1), which functions as a homodimer [15]. Structures of free, agonist-bound and antagonist-bound proteins confirm the predicted bilobed structure with the ligand-binding site positioned between the two lobes. Ligand binding brings the two lobes closer together, also causing tighter dimerization between the two ECDs of the homodimer. Antagonists bind at the same position and prevent receptor closing, thus holding the receptor in the inactive conformation.

Despite the insights gained by the structure of the mGluR ECD, the structure of the GABAB receptor is still highly in demand, but the production of large quantities of whole receptors for structural studies is a problem. To determine the minimal functional domain of the GABAB(1)ECD to allow structural studies of the ligand binding domain, we have performed analysis of domain boundaries and glycosylation of the receptor. Structural information would be invaluable in the design of novel GABAB receptor agonists, antagonists, allosteric modulators and possibly more selective and safer drugs.

Prediction of the precise domain boundaries is difficult, despite the predicted structural homology with the PBPs and glutamate receptor, due to low sequence similarities. Five putative glycosylation sites are present in the sequence encoding the GABAB(1)ECD, but it is not known whether oligosaccharides are necessary to allow correct folding of the protein, efficient translocation to cell surface or receptor function. In addition, definition of the minimal functional ligand-binding domain should shed light on the possible mechanisms of signal transduction in this heterodimeric GPCR. We have generated a series of GABAB(1b) (GABAB receptor subtype 1 variant b) receptor mutants with either N- and/or C-terminal deletions of the ECD or removal of individual or all potential glycosylation sites. These GABAB(1b) mutants were tested for their functionality by characterizing agonist binding and effector coupling. Our results indicate that the N-terminal boundary of the PBP-like domain (region homologous with the bacterial periplasmic leucine-binding protein) overlaps with the 5′ of the amino acid sequence encoded by exon 6 and the C-terminal boundary with the sequence encoded by the end of exon 14. Moreover, GABAB(1b)Δglyc (unglycosylated GABAB(1b)) behaves similarly to the wild-type protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Alignment and modelling

Amino acid sequences of ECDs of the rat, human and mouse GABAB(1) receptors were aligned with the sequence of the ECD of the mGluR1 taken from the Protein Data Bank (PDB no. 1EWT), along with the sequences of the other mGluRs (mGluRs 2–7 from human and rat; mGluR 8 from human, rat and mouse), retrieved from the Swiss-Prot database. A preliminary alignment was performed with ClustalW (www.expasy.ch, [16]) using default parameters and the BLOSUM62 matrix. The output from ClustalW was then manually adjusted. Figure 1(B) shows the sequence alignment of GABAB(1b)ECD from Rattus norvegicus with the mGluR1 ECD. The secondary structure of the latter was directly derived from PDB number 1EWT (crystal structure, ligand-free open form). Secondary-structure prediction for the GABAB(1b)ECD was performed with PSI-PRED [17]. Several models were generated with Modeller [18], imposing disulphide bridge formation between cysteine residues C103 and C129 and between C259 and C293. The co-ordinates of these models were subjected to the Verify3D algorithm [19], using the Verify3D Structure Evaluation Server (www.doe-mbi.ucla/Services/Verify_3D.htlm). The best model was depicted with Molscript [20,21] and Raster3D [22] (Figure 1C).

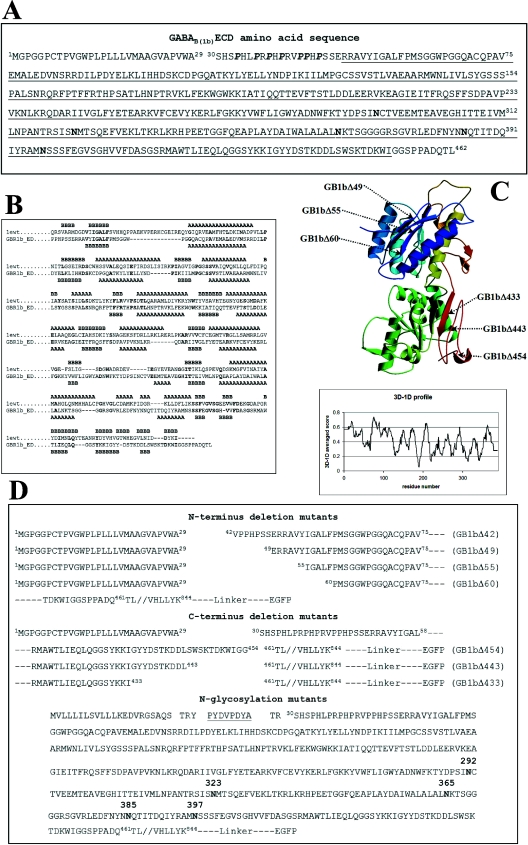

Figure 1. (A) GABAB(1b)ECD sequence, (B) sequence alignment, (C) model of the GABAB(1)ECD and (D) designed constructs.

The natural signal sequence of GABAB(1b) from R. norvegicus spans amino acids 1–29. Proline residues belonging to the N-terminal domain characteristic for the variant 1b appear in bold italic. The sequence encoded by exons 6–14 is underlined. The five potential N-glycosylation sites are indicated in boldface. (B) The amino acid sequence of the mGluR1 (1ewt) is derived from the PDB number 1EWT; GBR1b_ED is the sequence of the GABAB(1b)ECD. Secondary structural elements observed (in the crystal structure 1EWT) or predicted (for GABAB(1)ECD) are indicated with A for α-helices and B for β-strands. Identical residues in the two sequences appear in boldface. The following regions were omitted from the alignment used to generate the model: in mGluR1, residues 132–153 (not present in the PDB number 1EWT) and 348–405; in the GABAB(1)ECD sequence, residues 316–347. (C) The model was ramp-coloured from blue to green and yellow to red, going from the N- to the C-terminus. Arrows indicate the generated GABAB(1b) receptor deletion mutant proteins. The panel shows the plot obtained from the Verify3D algorithm using the co-ordinates of the modelled GABAB(1)ECD. The x-axis indicates the residue numbers and y-axis gives the averaged 3D–1D scores. (D) The top part of the panel shows the N-terminal deletion mutants, all containing the natural signal sequence of the GABAB(1b); the middle part of the panel shows the C-terminal deletions of the ECD. Details on construct generation are given in the Materials and methods section. The bottom part of the panel shows the sequence of the N-glycosylation mutants. The haemagglutinin tag is underlined. Asparagine residues, which can potentially be glycosylated in vivo, appear in boldface. All constructs are fused C-terminally through a short linker to the EGFP.

Generation of GABAB(1b) mutants

Wild-type GABAB(1b) was subcloned in the plasmid pEGFP-N1 (ClonTech, Palo Alto, CA, U.S.A.), using the single cloning site NheI and EcoRI. GABAB(1b) cDNA is, thus, in frame with the downstream nucleotide sequence of the EGFP (enhanced green fluorescence protein). N-terminal deletion mutants of the GABAB(1b) were generated in three different PCR steps as follows: a first PCR amplified the natural signal sequence of GABAB(1b); the reverse primer carried an additional sequence to enable annealing with the region downstream of the section to be deleted. A second PCR amplified the nucleotide sequence of GABAB(1b) without signal sequence; the forward primer was designed to anneal in the region downstream of the portion to be removed and contains, as an additional 5′ attachment, a nucleotide stretch enabling annealing with the last three triplets of the signal sequence. The two resulting PCR products were amplified with the forward primer of the first PCR and the reverse primer of the second PCR to obtain the final construct. The first amino acid in the signal sequence of GABAB(1b) is M1GPGGP. Taking the first amino acid after cleavage of the signal peptide to be Ser-30, the following deletions were introduced (Figure 1D): from Ser-30 to Arg-41 (GB1bΔ42), from Ser-30 to Ser-48 (GB1bΔ49), from Ser-30 to Tyr-54 (GB1bΔ55) and from Ser-30 to Phe-59 (GB1bΔ60).

GABAB(1b) constructs with deletions at the C-terminus of the ECD were generated in two different PCR steps: primers were designed to amplify three different regions in the sequence coding for the ECD of GABAB(1b); from M1GPGGP to TDKWIGG454 (GB1bΔ454), to DSTKDDL443 (GB1bΔ443) and to GGSYKKI433 (GB1bΔ433) (Figure 1D); all three reverse primers used contained XhoI cloning sites. An additional PCR generated the sequence for the rest of the GABAB(1b) receptor from T461FRFL to the C-terminal end; the forward primer also contained an XhoI cloning site. The two different PCR products obtained were ligated into pEGFP-N3 (ClonTech) previously digested with NheI and EcoRI. Two additional amino acids, leucine and glutamic residues (derived from the XhoI cloning site) are introduced.

Construct GB1bΔ55 was digested with NheI and HindIII and ligated with the construct GB1bΔ443 previously digested with the same enzymes to obtain GB1bΔ55/443. All constructs produced were confirmed by sequencing.

For the generation of mutants at putative glycosylation sites, the natural signal sequence of GABAB(1b) was replaced with the mGluR5 signal peptide MVLLLILSVLLLKEDVRGSAQS followed by the haemagglutinin epitope (TRYYDVPDYAT). Using the Quik Change Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, U.S.A.), the following mutations were introduced (Figure 1D): N292Q (Asn292Gln) (GB1bN292Q), N323Q (GB1bN323Q), N365Q (GB1bN365Q), N385Q (GB1bN385Q), N397Q (GB1bN397Q), N292Q-N323Q-N365Q-N385Q-N397Q (GB1bΔglyc). GABAB(2) was constructed as described in [3]. To couple GABAB(1b)/GABAB(2) with PLC (phospholipase C), we utilized a chimaeric form of the Gαq protein named GαqzIC, in which the last five C-terminal residues are replaced by the corresponding residues of Gαi, which is normally activated by the heterodimer [6].

Exon–intron organization was derived from the published work on rat GABAB(1) receptor of Pfaff et al. [23] and Bowery et al. [24] and human GABAB(1) receptor of Goei et al. [25].

Cell culture

Mammalian cells were purchased from the A.T.C.C. (Rockville, MD, U.S.A.). HEK-293 cells (human embryonic kidney 293 cells) and COS-1 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's minimal essential medium (Life Technologies, Basel, Switzerland) and supplemented with 10% (v/v) foetal calf serum.

Immunoblotting

HEK-293 cells were transiently transfected with LIPOFECTAMINE™ (Life Technologies) as described by the manufacturer and plated in 6-well plates. After 48 h, cells were harvested, centrifuged, homogenized and resuspended in 10 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.2) containing 0.1% SDS. Protein concentrations were estimated (bicinchoninic acid assay; Pierce) and aliquots of 20 μg of protein were then mixed with Laemmli buffer [125 mM Tris/HCl, pH 6.8, 1% SDS, 25 mM 1,4-dithio-DL-threitol, 5% (v/v) glycerol/Bromophenol Blue], loaded on to 7.5% gels and separated by SDS/PAGE. Standard electrophoretic transfer was used to blot proteins on to a nitrocellulose membrane, which after blotting was blocked with 5% (w/v) non-fat milk powder in TBST (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.0, 150 mM NaCl and 0.05% Tween 20) for 1 h at room temperature (22 °C). The first and the secondary antibodies, rabbit antibody 174.1 directed against the intracellular domain of GABAB(1) [25] and the goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) POD, 1:2000 and 1:7000 respectively (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Glattbrugg, Switzerland) were incubated with blocking solution for 1 h at room temperature. A stringent wash was performed for 15 min after the addition of the antibodies using 20 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, 60 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.4% SDS, 0.4% Triton X-100, 0.4% deoxycholate, followed by two further washes with TBST. The antibody complex was detected using BM chemiluminescence blotting substrate (POD) (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) and exposure to Biomax maximum resolution X-ray films (Kodak, Cambridge, U.K.).

Photolabelling experiments

HEK-293 cells were grown and transfected by LIPOFECTAMINE™ (Life Technologies). Cells were harvested and lysed 72 h after transfection with a glass homogenizer. GABAB(1b) wild-type and mutants contained in the membrane fraction were photolabelled as described in [26,27]. For SDS/PAGE, the membrane pellets were resuspended in Hepes buffer (Life Technologies) containing 0.1% SDS. A total of 30 μg of protein was loaded on to 10% gels. Photoaffinity-labelled proteins were detected using autoradiography.

Measurement of Δ[Ca2+]i by fluorometry

HEK-293 cells (2.0×106) were mixed with 5 μg of wild-type or mutant GABAB(1b) cDNA and electrophorated as described previously [12]. All transfections included cDNAs for GABAB(2) and for the Gα subunit GαqzIC to couple GABAB(2) with PLC [6]. Transfected cells were resuspended in culture medium and split into two wells of a 12-well plate, containing glass coverslips that had previously been coated with poly(D-lysine) (100 mg/ml). Cells were washed and incubated 24 or 48 h after transfection at room temperature for 1 h in Hepes buffer (Life Technologies) containing 10 μg/ml of the calcium indicator fura 2/AM (fura 2 acetoxymethyl ester), 0.5% Pluronic F-127 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, U.S.A.) and 1% (v/v) DMSO. Coverslips carrying dye-loaded cells were mounted into a perfusion cuvette (1 ml/min) in a fluorescence spectrophotometer (F-4500; Hitachi). Changes of intracellular calcium concentration [Ca2+]i were monitored by measuring the ratio of fura 2/AM fluorescence (510 nm) excited at 340 and 380 nm after application of 0.1 mM GABA. CGP54626A (10 μM) was used to antagonize the effect of GABA [27]. No quantitative comparison between experiments was made, because the signal amplitude depends on the transfection efficiency.

Surface expression labelling

HEK-293 cells were transfected as described before with wild-type GABAB(1b)/GABAB(2) and GABAB(1b)Δglyc/GABAB(2), seeded in an eight chamber polystyrene vessel, with a tissue culture-treated glass slide and cultured for 48 h. Cells were soaked in 3.7% (w/v) paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature and blocked for 30 min at 37 °C with 10% (v/v) foetal calf serum and 0.5% BSA in PBS. Mouse monoclonal antibody anti-haemagglutinin tag (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) and Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (Molecular Probes) were incubated at 37 °C for 45 and 30 min respectively. Images were collected with a Leica TCS SP2 microscope. Cells were excited at 488 and 590 nm and images were collected at 507 and 617 nm, for EGFP and Alexa Fluor, respectively.

Quantitative fluorimetric image plate experiments

Fluorimetric image plate experiments were performed as described previously [12]. Briefly, HEK-293 cells, electrophorated with GABAB(1b)Δglyc:GABAB(2):GαqzIC cDNAs, were loaded with 2 μM fluo-4 AM (Molecular Probes) 48 h after transfection. Cells were measured in a fluorimetric image plate reader (FLIPR; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, U.S.A.). Concentration–response curves of GABA were recorded using eight wells per concentration, data were analysed as fluorescence changes over baseline (ΔF/F) and a Hill equation was fitted to the data using Igor Pro (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR, U.S.A.).

RESULTS

Design of GABAB(1b) receptor mutants

Research performed on mGluR1 has previously illustrated that the domain boundaries of a still functional and crystallizable ECD fragment can be identified by deletion mutagenesis of regions at the C-terminus of the N-terminal domain [28]. For our studies of the GABAB(1)ECD, we adopted a similar strategy. GABAB(1) gene contains alternative transcription initiation sites which result in the generation of different isoforms, the two most prominent isoforms being GABAB(1a) and GABAB(1b), which differ in their N-terminal domain [27,29]. The splice variant GABAB(1b) results from the presence of an alternative transcription initiation site within the GABAB(1a) intron, upstream of exon 6, thereby extending exon 6 at its 5′-end. Consequently, the first 147 amino acids of the GABAB(1a) variant, which code for two regions known as Sushi domains, are replaced in GABAB(1b) with a unique sequence of 18 amino acids containing several proline residues [23,24,29] (Figure 1A). Since the Sushi domains identified in the GABAB(1a) variant are not required for ligand binding [30], we chose the GABAB(1b) receptor for our studies.

To define domain boundaries for the GABAB(1b)ECD, we aligned its amino acid sequence with that of the mGluR1 fragment crystallized in a ligand-free open form (PDB number 1EWT) [15]. We also included in the alignment the GABAB(1) amino acid sequences from other species (human and mouse) along with mGluR sequences (human, rat and mouse). Known similarities between the ligand binding domains of GABAB(1) receptor and of the mGluR were taken into account by manually editing the multiple sequence alignment [31–34]. The alignment between GABAB(1)ECD and the mGluR1 ECD (Figure 1B) was used to generate several different models; restraints were applied to induce the formation of disulphide bridges between cysteine residues. The best model obtained (evaluated with Verify3D algorithm [19]) (Figure 1C) encompasses the region spanning exons 6–14. On the basis of this analysis, we designed N-terminally truncated mutants of the GABAB(1b) receptor starting before, at the edge and within the next ten residues encoded by the 5′-end of exon 6. Deletions at the C-terminus were set at the end and in the last 25 amino acids encoded by exon 14. The remainder of the receptor from Thr-461 to the C-terminus was kept constant in all mutants (Figure 1D).

Identification of the important regions for ligand binding in GABAB(1b) deleted mutants

The GABAB(1b)ECD N- or C-terminal deletion mutants were transiently expressed in heterologous cells (Figure 2A) and tested for their ability to bind the high-affinity antagonist [125I]CGP71872 by photoaffinity cross-linking (Figure 2B). Although the samples detected by the antibody against the GABAB(1b) receptor show significant degradation, in all constructs there is still a significant proportion of full-length protein present.

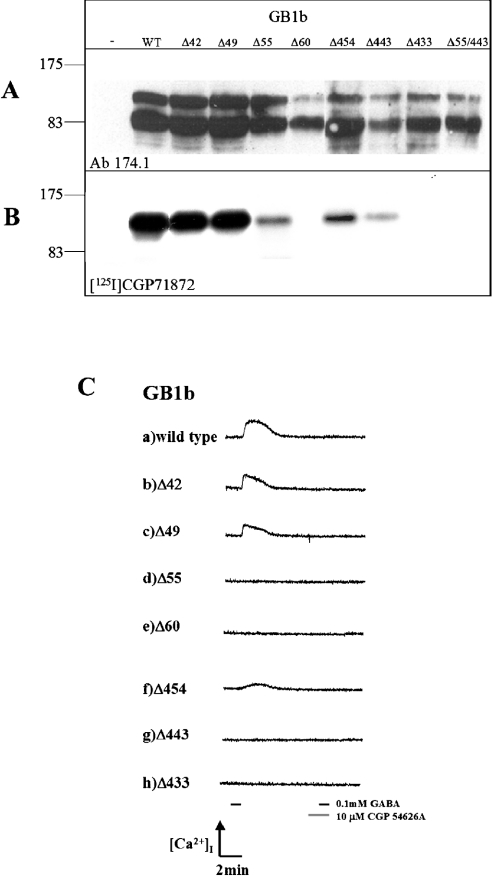

Figure 2. Expression, photolabelling with [125I]CGP71872 and agonist activation of GABAB(1b)ECD deletion mutants.

(A) Western blot. The immunoblot was performed with antibodies specific for GABAB(1) subunits, to confirm the expression of the designed mutants. Protein concentrations were estimated (Biochronic assay; Pierce) and an equal amount of protein was loaded per lane. Lane 1, indicated with a minus, shows membranes of cells transfected without cDNA. Lane WT, wild-type GABAB(1b). Since proteins (molecular mass 100 kDa) are expressed as EGFP fusion proteins, their molecular mass is 20 kDa higher. A lower band is also observed which results from degradation of the full-length protein. This degraded form is detected by the antibody, but is not able to bind the antagonist (see Figure 2B). (B) Photolabelling. Samples identical with those detected in Figure 2(A) were tested for their ability to bind the highly specific GABAB(1) inhibitor [125I]CGP71872. WT indicates wild-type GABAB(1b), lanes GB1bΔ42, GB1bΔ49, GB1bΔ55 and GB1bΔ60 indicate the N-terminally truncated receptors; lanes GB1bΔ454, GB1bΔ443 and GB1bΔ433 indicate GABAB(1b) receptors with C-terminal deletions of the ECD. Lane GB1bΔ55/Δ443 shows GABAB(1b) receptors containing deletions both at the N- and C-terminus of the ECD. No cross-reaction between the iodinated antagonist and HEK-293 untransfected cells was observed (first lane). (C) HEK-293 cells, electrophorated with cDNAs of GABAB(2), chimaeric GαqzIC, GABAB(1b) wild-type (a) and mutants (b–h) were perfused with 0.1 mM GABA for 60 s (short horizontal line on the left side of the 13 min timescale at the bottom of the picture). Changes in intracellular calcium concentration [Ca2+]i were monitored by measuring the ratio of fura 2/AM fluorescence (510 nm) excited at 340 and 380 nm. The generated response could be completely antagonized by preapplication of 10 μM CGP 54626A (short black and grey horizontal lines at the right bottom of the picture). Lanes a–h display changes in fluorescence in response to GABA and CGP54626A application.

Whereas mutants with N-terminal deletions of 12 and 19 amino acids bound the antagonist as well as wild-type GABAB(1b) (Figure 2B, lanes WT, Δ42 and Δ49), a substantial decrease in binding ability was observed by the deletion of 25 N-terminal amino acids (GB1bΔ55). Binding was completely abolished when the N-terminus was truncated even further (GB1bΔ60; Figure 2B, lanes Δ55 and Δ60 respectively). The amount of undegraded GB1bΔ60 is quite low when compared with the other proteins, although there is still a significantly strong band for the degradation product, which may indicate that the protein is less stable than the longer forms. However, even if the absence of antagonist binding is partially a result of the low protein levels, it is clear that this construct is not a suitable target for binding studies. Surprisingly, at the C-terminus of the GABAB(1b)ECD, in a region that is quite often considered to be a linker between the ECD and the first transmembrane helix, deletion of just six amino acids (S455PPADQ460, mutant GB1bΔ454) already decreased the binding capacity with respect to the wild-type protein (Figure 2B, lane Δ454). Further deletions of 17 and 27 amino acids at the C-terminus of the ECD strongly diminished or completely abolished the binding ability respectively (Figure 2B, lanes Δ443 and Δ433). This is clearly not a result of variations in protein levels, since even though the Δ443 mutant is present in lower amounts than the Δ433 mutant, Δ443 shows binding, whereas Δ433 does not. Since we were able to detect significant, yet reduced antagonist binding in the GABAB(1b) mutants with either deletion of 25 amino acids at the N-terminus (GB1bΔ55) or 17 amino acids at the C-terminus (GB1bΔ454) of the ECD, we evaluated the binding ability of a GABAB(1b) mutant exhibiting both of these deletions. With this composite mutant GB1bΔ55/443 no photoaffinity-labelled receptor was detected, although the receptor was expressed (Figure 2A, lane Δ55/Δ443). Thus the effects of these deletions on the ability of the GABAB(1b) to bind a ligand are additive or even synergistic (Figure 2, lane Δ55/Δ443). No antibody cross-reaction or binding was detected in untransfected cells (Figures 2A and 2B, first lane).

Signal transduction ability of the GABAB(1b) deleted mutants

Although the experiments described above illustrate ligand binding, they do not confirm the ability of the truncated receptors, on agonist binding, to induce the conformational change in the GABAB heterodimer, which is essential for coupling with downstream effector cascades [9,34]. Thus, to identify the minimal, functional, binding domain, we investigated the ability of our GABAB(1b) mutants to assemble into functional heterodimers. On transient co-expression of the mutants with wild-type GABAB(2) and a chimaerical Gα subunit, GαqzIC [6], in HEK-293 cells, we measured GABA-induced activation of intracellular Ca2+ levels by fluorimetry.

GB1bΔ42 and GB1bΔ49 N-terminal deletion mutants behaved similarly to the wild-type protein (Figure 2C, lanes a–c), which can be activated with 0.1 mM GABA and subsequently blocked completely using 10 μM CGP54626A. These results are in agreement with the photoaffinity labelling experiments. However, deletion of 25 N-terminal amino acids of the GABAB(1)ECD, GB1bΔ55, completely abolished the function of the heterodimer (Figure 2C, lane d), even though this mutant could be labelled by the photoaffinity ligand (Figure 2B, lane Δ55). Additional experiments allowing for longer protein expression time, drug application time and increased GABA concentration (up to 1 mM) confirmed these findings (results not shown). As expected, the mutant GB1bΔ60, presenting an even longer N-terminal deletion, also did not exhibit any functional response (Figure 2C, lane e). Similar observations were made with the mutants carrying deletions at the C-terminal end of the GABAB(1)ECD. Deletion of six amino acids in GB1bΔ454 did not impair the ability of the heterodimer to couple with PLC on GABA administration (Figure 2C, lane f), but deletion of a further 11 amino acids in GB1bΔ443 completely abolished receptor activation (Figure 2C, lane g). Thus, as already observed for the mutant GB1bΔ55, GB1bΔ443 was also not able to activate intracellular effector systems, although it retained binding ability. As expected, additional deletions at the C-terminus did not lead to a functional receptor (Figure 2C, GB1bΔ433 lane h).

Expression of GABAB(1b) glycosylation mutants

Analysis of the primary structure of the GABAB(1b) receptor revealed five potential N-glycosylation sites. Few eukaryotic protein overexpression systems yield sufficient amounts of homogeneously glycosylated material for structural studies. Moreover, prokaryotic expression systems, which still represent the cheapest, fastest and most useful method to overexpress proteins, lack the capability to glycosylate proteins. To study the effect of absent carbohydrates with respect to receptor function, we designed GABAB(1b) receptor mutants in which each or all potential N-glycosylation sites have been eliminated (N to Q mutation, Figure 1D).

We fused the C-terminus of these constructs with the nucleotide sequence of the EGFP and added an N-terminal haemagglutinin tag to investigate the trafficking of the de-glycosylated receptor. Wild-type and modified receptors were transiently expressed in COS-1 cells. Western-blot analysis shows that the wild-type and the single-point mutants have approximately the same apparent molecular mass (132 kDa) (Figure 3A).

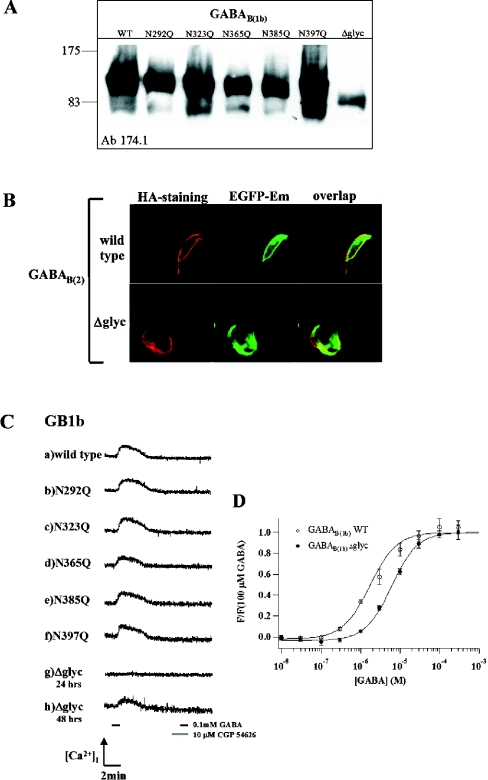

Figure 3. Functional analysis of GABAB(1b) glycosylation mutants.

(A) Western blot. WT, wild-type GABAB(1b); lanes 2–6, single-point mutants; Δglyc, GABAB(1b)Δglyc, with all glycosylation sites mutated. No molecular mass shifts are observed between single-point glycosylation mutants; molecular mass was estimated to be approx. 130–135 kDa. The calculated molecular mass of GABAB(1b)Δglyc plus EGFP is 122.5 kDa. (B) Surface expression of glycosylation-deficient GABAB(1b) receptor. Staining for the haemagglutinin tag (first row, HA-staining), EGFP emission (second row, EGFP-Em) and overlap of the two (third row, overlap). (C) Fluorimetric analysis. HEK-293 cells, electrophorated with the cDNAs of GABAB(2), chimaeric GαqzIC, and either GABAB(1b) wild-type (a) or mutants (b–h) were perfused with 0.1 mM GABA for 60 s. The generated response could be completely antagonized using 10 μM CGP54626A (grey segment on the timescale), since no response was measured by subsequent application of GABA (black segment on the right side of timescale, 60 s). Lanes (a–g) display changes in fluorescence in response to GABA application 24 h post-transfection. Lanes (g) and (h) correspond to the GABAB(1b)Δglyc form, lane (g) 24 h after transfection, lane (h) 48 h after transfection. (D) Agonist concentration–response curves of wild-type and glycosylation-deficient GABAB(1b) receptors. HEK-293 cells were measured in FLIPR [12], 48 h after transfection of each variant together with GABAB(2) and chimaeric GαqzIC. Data points show average fluorescence values of 4 (WT) or 8 (Δglyc) wells ±S.E.M., normalized to the average response to 0.1 mM GABA. Hill equation fits gave EC50 values of 2.4 (1.7, 3.4) for WT and 6.4 μM (5.3, 7.8) for the Δglyc mutant (mean, 95% confidence interval).

This finding suggests variation in glycosylated positions in GABAB(1b), resulting in incomplete glycosylation. The calculated molecular mass (without taking into account the oligosaccharides mass) of wild-type GABAB(1b) fused to EGFP is approx. 122.5 kDa, which corresponds to the GABAB(1b)Δglyc molecular mass (Figure 3, lane Δglyc).

Heterodimerization of GABAB(1b) glycosylation mutants with GABAB(2) and intracellular signalling

N-linked glycosylation is supposed to be important for receptor trafficking and folding and has also been implicated in the regulation of heterodimerization of GPCRs [35]. To determine the role of glycosylation on the GABAB(1b) receptor, we investigated the surface expression of wild-type GABAB(1b) and GABAB(1b)Δglyc, using anti-haemagglutinin antibody staining and EGFP detection. Whereas surface expression of GABAB(1b)Δglyc after 24 h was much lower than that of the wild-type receptor, surface expression levels of GABAB(1b)Δglyc were similar to those of the wild-type, 48 h after transient transfection, as shown in Figure 3(B).

Analysis of the ability of GABAB(1b) glycosylation mutants to transmit the extracellular signal to intracellular effector systems was performed to clarify the influence of N-linked glycosylation on protein folding, translocation, heterodimerization and receptor function. To perform this functional analysis, we measured GαqzIC-mediated activation of intracellular Ca2+ levels ([Ca2+]i) on binding of GABA to the mutated GABAB(1b) receptor, as described above for the truncation mutants. As shown in Figure 3(C), the GABAB(1b) mutants that were depleted of individual glycosylation sites remained functional. Cells expressing GABAB(1b)Δglyc revealed no functional response when assayed 24 h after transfection (Figure 3C, lane g); however, after 48 h, an increase in [Ca2+]i was observed on GABA administration (Figure 3C, lane h), illustrating that GABAB(1b)Δglyc could still form a functional heterodimer. To determine whether there are significant differences between the wild-type and the fully deglycosylated receptor, we measured a concentration–response curve for the agonist GABA. We found that wild-type GABAB(1b) and GABAB(1b)Δglyc receptors differ only slightly in their EC50 values, which are 2.4 [12] and 6.4 μM respectively (Figure 3D).

DISCUSSION

The functional GABAB receptor comprises two GPCRs, namely GABAB(1) and GABAB(2). It is evident that, within this functional heterodimer, GABAB(1) provides the ligand binding domain, whereas GABAB(2) is required for the transmission of signal to the intracellular coupled G-protein [9,11,36,37]. In the present study, we have sought to determine the minimal binding domain of the GABAB(1) receptor to gain insight into the binding of ligand and the mechanism of signal transmission to the heterodimeric partner GABAB(2). The architecture of the GABAB(1)ECD was previously predicted based on comparison with the bacterial periplasmic binding proteins and important residues for the interaction with the neurotransmitter were identified by sequence alignment and modelling [31–33]. The three-dimensional structure of the ECD of the mGluR1, a member of the family 3 GPCRs, was solved by Kunishima et al. [15]. This result was achieved after several years of investigations, probing the extracellular ligand-binding domain by proteolytic digestion and deletion mutagenesis [28,38]. It is hoped that our studies to define the GABAB(1)ECD boundaries and the effect of the absence of carbohydrate moieties on protein function will be advantageous in the production of material suitable for crystallographic studies.

Information regarding the genomic organization of the R. norvegicus GABAB(1) gene [23] and from sequence comparisons was used to design constructs as a basis for scouting the PBP-like domain boundaries of GABAB(1)ECD by deletion mutagenesis. The generated mutants were analysed to determine which of these GABAB(1)ECD mutants were capable of binding ligand and, in combination with GABAB(2), assemble into a functional heterodimer.

An N-terminal deletion omitting the 18 amino acid, proline-rich sequence that is specific to the GABAB(1b) variant did not interfere with ligand binding and effector coupling, indicating that the variant-specific domains at the N-terminus of GABAB(1a) and GABAB(1b) are not essential for basic receptor function.

Recent studies, elucidating the mechanism of signal transmission following ligand binding to the GABAB(1) subunit through GABAB(2) to intracellular effector systems, suggested that the primary amino acid sequence of the region between the PBP-like domain and the first transmembrane helix of GABAB(1) is not critical for signal transduction [11]. Our results, however, demonstrate that the deletion of 17 amino acids from this linker region in GB1bΔ443 completely abolishes signal transmission, even though antagonist binding could still be detected. This suggests that whereas the sequence of this region may not be critical, a minimal distance between the PBP-like domain and the first transmembrane domain of GABAB(1) is required to enable the formation of functional heterodimers.

Studies of the PBP-like domains have indicated that dynamic changes occur between open and closed forms, with the ligand acting to stabilize the closed conformation [39]. Similarly, the crystal structures of the mGluR1 ECD revealed both open and closed conformations for the ligand-free protein, suggesting a dynamic equilibrium between the two, whereas the structure in complex with glutamate showed only the closed form [15]. Such observations give rise to two possible explanations for our observed results with the GABAB(1)ECD: either that the GB1bΔ55 and GB1bΔ443 proteins are capable of binding the iodinated antagonist but are incapable of closing correctly the two lobes composing the PBP-like domain; or that these mutants are not capable of dimerizing correctly with the GABAB(2) receptor. It cannot be excluded, however, that these observations are the result of differences in sensitivity between the antagonist binding assay and the functional fluorimetric analysis.

GPCRs usually contain at least one potential N-linked glycosylation site. Despite the frequency of this post-translational modification, however, the role of this modification is not clear and seems to vary from receptor to receptor. Removal of glycosylation by site-directed mutagenesis or by biochemical methods has been shown to affect receptor trafficking to the cell membrane in a number of receptors (e.g. human calcium receptor [40], human dopamine D5 receptor [41], hamster β-adrenergic receptor [42] and human angiotensin II receptor AT1a [43]); whereas allowing normal cell surface expression in others (human V2 vasopressin receptor [44], human parathyroid hormone receptor [45] and canine H2 histamine receptor [46]). Glycosylation has also been implicated in the regulation of receptor function [47], heterodimerization and signalling, perhaps by influencing receptor conformation and interactions.

The GABAB receptors belong to the family 3 GPCRs that contain at least 25 members. The effect of the removal of glycosylation has so far only been reported for the mGlu1a receptor and for the calcium-sensing receptor. In the human calcium receptor 8 of the 11 potential N-glycosylation sites appear to be glycosylated and this glycosylation is required for normal folding in the endoplasmic reticulum, with removal of five or more sites resulting in misfolding [40]. The effect of glycosylation on the mGlu1a receptor is less clear. Whereas one group reports normal trafficking and signal transduction of the whole receptor after expression in the presence of tunicamycin [48], a second, working only with the N-terminal ECD, reported preliminary results that mutation of the glycosylation sites does affect both cell-surface expression and signal transduction [49].

Our results with the GABAB(1) receptor reveal that the disruption of individual consensus glycosylation sites essentially does not change receptor function when compared with the wild-type receptor and also does not affect receptor trafficking. Mutation of all consensus glycosylation sites, although it does not significantly affect receptor function, did result in a delay in the presentation of functional receptor at the cell surface, suggesting problems with receptor folding or trafficking. Removal of multiple consensus glycosylation sequences is known to give rise to folding problems causing non-glycosylated or partially glycosylated or misfolded receptors to be retained in the endoplasmic reticulum [50]. Correct glycosylation seems to promote sorting of proteins to their required subcellular compartment [51–53]. The GABAB(1b)Δglyc receptor remains capable of folding and finally appears on the cell surface.

We have determined that the GABAB(1b)Δglyc found at the cell surface is capable of heterodimerization with GABAB(2) and is able to produce, on GABA activation, the conformational changes that activate signal transduction demonstrated by the wild-type receptor. Thus the non-glycosylated receptor presented at the cell surface is correctly folded and functional. It appears, therefore, that glycosylation in the GABAB(1b) receptor may promote folding and trafficking of the receptor to the surface, but that this modification is not essential for receptor function. It seems unlikely that glycosylation of the GABAB(1b) receptor is important for heterodimerization, since our unglycosylated receptor is still capable of heterodimerization with GABAB(2) and, as yet, no other receptor has been found to couple functionally with GABAB(1b). It remains possible that glycosylation may be important in GABAB(1b) for reasons other than protein folding and stability in the expression pathway. GABAB(1b) is known to interact with the glycosylation machinery of the Golgi apparatus, machinery that transforms N-linked oligosaccharides in a protein- and cell-dependent manner to modulate new functions such as cell–cell recognition during embryogenesis and tissue organization.

In conclusion, we have identified by deletion and site-directed mutagenesis scouting of the GABAB(1)ECD, the minimal sequence required to form a functional ligand-binding domain, which on the cDNA level corresponds exactly to the sequence from exons 6–14. This information is important to elucidate how ECDs of GPCRs are able to communicate with their transmembrane domains to transmit signal to intracellular G-proteins. We also hope that this information will assist in the generation of proteins for structural investigations. Studies of the effect of glycosylation of the GABAB(1b) are important to understand the role of this post-translational modification, which is common in GPCRs. We have established that the unglycosylated N-terminal domain functions similarly to the wild-type receptor opening the possibility to produce and study this receptor from a range of expression systems.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Dr G. Capitani for reading the manuscript. The financial support of the Swiss National Center of Competence in Research (Structural Biology), of the Swiss National Science foundation (to M.G. and B.B.) and of the Baugartenstiftung (Zurich, Switzerland) to M.G. is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- 1.Vacher C. M., Bettler B. GABA(B) receptors as potential therapeutic targets. Curr. Drug Target CNS Neurol. Disord. 2003;2:248–259. doi: 10.2174/1568007033482814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones K. A., Borowsky B., Tamm J. A., Craig D. A., Durkin M. M., Dai M., Yao W. J., Johnson M., Gunwaldsen C., Huang L. Y., et al. GABA(B) receptors function as a heteromeric assembly of the subunits GABA(B)R1 and GABA(B)R2. Nature (London) 1998;396:674–679. doi: 10.1038/25348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaupmann K., Malitschek B., Schuler V., Heid J., Froestl W., Beck P., Mosbacher J., Bischoff S., Kulik A., Shigemoto R., et al. GABA(B)-receptor subtypes assemble into functional heteromeric complexes. Nature (London) 1998;396:683–687. doi: 10.1038/25360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White J. H., Wise A., Main M. J., Green A., Fraser N. J., Disney G. H., Barnes A. A., Emson P., Foord S. M., Marshall F. H. Heterodimerization is required for the formation of a functional GABA(B) receptor. Nature (London) 1998;396:679–682. doi: 10.1038/25354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ng G. Y., Clark J., Coulombe N., Ethier N., Hebert T. E., Sullivan R., Kargman S., Chateauneuf A., Tsukamoto N., McDonald T., et al. Identification of a GABAB receptor subunit, gb2, required for functional GABAB receptor activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:7607–7610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.7607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franek M., Pagano A., Kaupmann K., Bettler B., Pin J., Blahos J. The heteromeric GABA-B receptor recognizes G-protein alpha subunit C-termini. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:1657–1666. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00135-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Margeta-Mitrovic M., Jan Y. N., Jan L. Y. A trafficking checkpoint controls GABA(B) receptor heterodimerization. Neuron. 2000;27:97–106. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calver A. R., Robbins M. J., Cosio C., Rice S. Q., Babbs A. J., Hirst W. D., Boyfield I., Wood M. D., Russell R. B., Price G. W., et al. The C-terminal domains of the GABA(b) receptor subunits mediate intracellular trafficking but are not required for receptor signaling. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:1203–1210. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-04-01203.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galvez T., Duthey B., Kniazeff J., Blahos J., Rovelli G., Bettler B., Prezeau L., Pin J. P. Allosteric interactions between GB1 and GB2 subunits are required for optimal GABA(B) receptor function. EMBO J. 2001;20:2152–2159. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.9.2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Margeta-Mitrovic M., Jan Y. N., Jan L. Y. Function of GB1 and GB2 subunits in G protein coupling of GABA(B) receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:14649–14654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251554498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Margeta-Mitrovic M., Jan Y. N., Jan L. Y. Ligand-induced signal transduction within heterodimeric GABA(B) receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:14643–14648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251554798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pagano A., Rovelli G., Mosbacher J., Lohmann T., Duthey B., Stauffer D., Ristig D., Schuler V., Meigel I., Lampert C., et al. C-terminal interaction is essential for surface trafficking but not for heteromeric assembly of GABA(b) receptors. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:1189–1202. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-04-01189.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snyder S. H., Pasternak G. W. Historical review: opioid receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2003;24:198–205. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(03)00066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Hara P. J., Sheppard P. O., Thogersen H., Venezia D., Haldeman B. A., McGrane V., Houamed K. M., Thomsen C., Gilbert T. L., Mulvihill E. R. The ligand-binding domain in metabotropic glutamate receptors is related to bacterial periplasmic binding proteins. Neuron. 1993;11:41–52. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90269-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kunishima N., Shimada Y., Tsuji Y., Sato T., Yamamoto M., Kumasaka T., Nakanishi S., Jingami H., Morikawa K. Structural basis of glutamate recognition by a dimeric metabotropic glutamate receptor. Nature (London) 2000;407:971–977. doi: 10.1038/35039564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G., Gibson T. J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones D. T. Protein secondary structure prediction based on position-specific scoring matrices. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;292:195–202. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sali A., Blundell T. L. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;234:779–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luethy R., Bowie J. U., Eisenberg D. Assessment of protein models with three-dimensional profiles. Nature (London) 1992;356:83–85. doi: 10.1038/356083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kraulis P. J. MOLSCRIPT: a program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1991;24:946–950. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merritt E. A., Bacon D. J. Raster3D photorealistic molecular graphics. Methods Enzymol. 1997;277:505–524. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)77028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esnouf R. M. An extensively modified version of MolScript that includes greatly enhanced coloring capabilities. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 1997;15:112–113. 132–134. doi: 10.1016/S1093-3263(97)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfaff T., Malitschek B., Kaupmann K., Prezeau L., Pin J. P., Bettler B., Karschin A. Alternative splicing generates a novel isoform of the rat metabotropic GABA(B)R1 receptor. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1999;11:2874–2882. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bowery N. G., Bettler B., Froestl W., Gallagher J. P., Marshall F., Raiteri M., Bonner T. I., Enna S. J. International Union of Pharmacology. XXXIII. Mammalian gamma-aminobutyric acid(B) receptors: structure and function. Pharmacol. Rev. 2002;54:247–264. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goei V. L., Choi J., Ahn J., Bowlus C. L., Raha-Chowdhury R., Gruen J. R. Human gamma-aminobutyric acid B receptor gene: complementary DNA cloning, expression, chromosomal location, and genomic organization. Biol. Psychiatry. 1998;44:659–666. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00244-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malitschek B., Ruegg D., Heid J., Kaupmann K., Bittiger H., Frostl W., Bettler B., Kuhn R. Developmental changes of agonist affinity at GABABR1 receptor variants in rat brain. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 1998;12:56–64. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1998.0698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaupmann K., Huggel K., Heid J., Flor P. J., Bischoff S., Mickel S. J., McMaster G., Angst C., Bittiger H., Froestl W., et al. Expression cloning of GABA(B) receptors uncovers similarity to metabotropic glutamate receptors. Nature (London) 1997;386:239–246. doi: 10.1038/386239a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okamoto T., Sekiyama N., Otsu M., Shimada Y., Sato A., Nakanishi S., Jingami H. Expression and purification of the extracellular ligand binding region of metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 1. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:13089–13096. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin S. C., Russek S. J., Farb D. H. Human GABA(B)R genomic structure: evidence for splice variants in GABA(B)R1 but not GABA(B)R2. Gene. 2001;278:63–79. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00678-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hawrot E., Xiao Y., Shi Q. L., Norman D., Kirkitadze M., Barlow P. N. Demonstration of a tandem pair of complement protein modules in GABAB receptor 1a. FEBS Lett. 1998;432:103–108. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00794-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galvez T., Parmentier M. L., Joly C., Malitschek B., Kaupmann K., Kuhn R., Bittiger H., Froestl W., Bettler B., Pin J. P. Mutagenesis and modeling of the GABAB receptor extracellular domain support a venus flytrap mechanism for ligand binding. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:13362–13369. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galvez T., Prezeau L., Milioti G., Franek M., Joly C., Froestl W., Bettler B., Bertrand H. O., Blahos J., Pin J. P. Mapping the agonist-binding site of GABAB type 1 subunit sheds light on the activation process of GABAB receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:41166–41174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007848200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galvez T., Urwyler S., Prezeau L., Mosbacher J., Joly C., Malitschek B., Heid J., Brabet I., Froestl W., Bettler B., et al. Ca(2+) requirement for high-affinity gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) binding at GABA(B) receptors: involvement of serine 269 of the GABA(B)R1 subunit. Mol. Pharmacol. 2000;57:419–426. doi: 10.1124/mol.57.3.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kniazeff J., Galvez T., Labesse G., Pin J. P. No ligand binding in the GB2 subunit of the GABA(B) receptor is required for activation and allosteric interaction between the subunits. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:7352–7361. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-17-07352.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu J., He J., Castleberry A. M., Balasubramanian S., Lau A. G., Hall R. A. Heterodimerization of alpha 2A- and beta 1-adrenergic receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:10770–10777. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207968200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robbins M. J., Calver A. R., Filippov A. K., Hirst W. D., Russell R. B., Wood M. D., Nasir S., Couve A., Brown D. A., Moss S. J., et al. GABAB2 is essential for G-protein coupling of the GABAB receptor heterodimer. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:8043–8052. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-20-08043.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duthey B., Caudron S., Perroy J., Bettler B., Fagni L., Pin J. P., Prezeau L. A single subunit (GB2) is required for G-protein activation by the heterodimeric GABA(B) receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:3236–3241. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108900200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsuji Y., Shimada Y., Takeshita T., Kajimura N., Nomura S., Sekiyama N., Otomo J., Usukura J., Nakanishi S., Jingami H. Cryptic dimer interface and domain organization of the extracellular region of metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 1. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:28144–28151. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003226200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oh B. H., Pandit J., Kang C. H., Nikaido K., Gokcen S., Ames G. F., Kim S. H. Three-dimensional structures of the periplasmic lysine/arginine/ornithine-binding protein with and without a ligand. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:11348–11355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ray K., Clapp P., Goldsmith P. K., Spiegel A. M. Identification of the sites of N-linked glycosylation on the human calcium receptor and assessment of their role in cell surface expression and signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:34558–34567. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.34558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karpa K. D., Lidow M. S., Pickering M. T., Levenson R., Bergson C. N-linked glycosylation is required for plasma membrane localization of D5, but not D1, dopamine receptors in transfected mammalian cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999;56:1071–1078. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.5.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rands E., Candelore M. R., Cheung A. H., Hill W. S., Strader C. D., Dixon R. A. Mutational analysis of beta-adrenergic receptor glycosylation. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:10759–10764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deslauriers B., Ponce C., Lombard C., Larguier R., Bonnafous J. C., Marie J. N-glycosylation requirements for the AT1a angiotensin II receptor delivery to the plasma membrane. Biochem. J. 1999;339:397–405. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Innamorati G., Sadeghi H., Birnbaumer M. A fully active nonglycosylated V2 vasopressin receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 1996;50:467–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bisello A., Greenberg Z., Behar V., Rosenblatt M., Suva L. J., Chorev M. Role of glycosylation in expression and function of the human parathyroid hormone/parathyroid hormone-related protein receptor. Biochemistry. 1996;35:15890–15895. doi: 10.1021/bi962111+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fukushima Y., Oka Y., Saitoh T., Katagiri H., Asano T., Matsuhashi N., Takata K., van Breda E., Yazaki Y., Sugano K. Structural and functional analysis of the canine histamine H2 receptor by site-directed mutagenesis: N-glycosylation is not vital for its action. Biochem. J. 1995;310:553–558. doi: 10.1042/bj3100553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Z., Austin S. C., Smyth E. M. Glycosylation of the human prostacyclin receptor: role in ligand binding and signal transduction. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001;60:480–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mody N., Hermans E., Nahorski S. R., Challiss R. A. Inhibition of N-linked glycosylation of the human type 1alpha metabotropic glutamate receptor by tunicamycin: effects on cell-surface receptor expression and function. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:1485–1492. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Selkirk M. I., Strathmann M. P., Gautam N. Characterization of an N-terminal secreted domain of the type-1 human metabotropic glutamate receptor produced by a mammalian cell line. J. Neurochem. 1991;80:346–353. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hammond C., Helenius A. Quality control in the secretory pathway. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1995;7:523–529. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scheiffele P., Peranen J., Simons K. N-glycans as apical sorting signals in epithelial cells. Nature (London) 1995;378:96–98. doi: 10.1038/378096a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gut A., Kappeler F., Hyka N., Balda M. S., Hauri H. P., Matter K. Carbohydrate-mediated Golgi to cell surface transport and apical targeting of membrane proteins. EMBO J. 1998;17:1919–1929. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.7.1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Benting J. H., Rietveld A. G., Simons K. N-glycans mediate the apical sorting of a GPI-anchored, raft-associated protein in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. J. Cell Biol. 1999;146:313–320. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.2.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]