Abstract

PPARα (peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor α) is a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily of ligand-activated transcription factors that regulate the expression of genes associated with lipid metabolism. In the present study, we show that circadian expression of mouse PPARα mRNA requires the basic helix–loop–helix PAS (Per-Arnt-Sim) protein CLOCK, a core component of the negative-feedback loop that drives circadian oscillators in mammals. The circadian expression of PPARα mRNA was abolished in the liver of homozygous Clock mutant mice. Using wild-type and Clock-deficient fibroblasts derived from homozygous Clock mutant mice, we showed that the circadian expression of PPARα mRNA is regulated by the peripheral oscillators in a CLOCK-dependent manner. Transient transfection and EMSAs (electrophoretic mobility-shift assays) revealed that the CLOCK–BMAL1 (brain and muscle Arnt-like protein 1) heterodimer transactivates the PPARα gene via an E-box-rich region located in the second intron. This region contained two perfect E-boxes and four E-box-like motifs within 90 bases. ChIP (chromatin immunoprecipitation) also showed that CLOCK associates with this E-box-rich region in vivo. Circadian expression of PPARα mRNA was intact in the liver of insulin-dependent diabetic and of adrenalectomized mice, suggesting that endogenous insulin and glucocorticoids are not essential for the rhythmic expression of the PPARα gene. These results suggested that CLOCK plays an important role in lipid homoeostasis by regulating the transcription of a key protein, PPARα.

Keywords: circadian rhythm, CLOCK, E-box, liver, peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα), transcription

Abbreviations: ADX, adrenalectomized; bHLH, basic helix–loop–helix; BMAL1, brain and muscle Arnt-like protein 1; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; CRY, cryptochrome; DBP, albumin D-site-binding protein; Dex, dexamethasone; DMEM, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium; DTT, dithiothreitol; EMSA, electrophoretic mobility-shift assay; ET-1, endothelin-1; FBS, foetal bovine serum; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblast; PAS, Per-Arnt-Sim; PER, period; PPARα, peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor α; RXR, retinoid X receptor; SCN, suprachiasmatic nucleus; STZ, streptozotocin

INTRODUCTION

The variety of physiological and behavioural circadian rhythms of almost all life forms from bacteria to humans is controlled by endogenous oscillators [1–3]. The SCN (suprachiasmatic nucleus) is considered to be the master circadian pacemaker that controls most of the physical circadian rhythms of mammals, including behaviour [4,5]. Many studies at the molecular level have revealed that the circadian oscillator in the SCN is driven by negative-feedback loops consisting of the periodic expression of clock genes [4,5]. Clock was the first clock gene in vertebrates identified by forward mutagenesis using N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea in a behavioural screening [6]. The Clock gene encodes a bHLH (basic helix–loop–helix)–PAS (Per-Arnt-Sim) transcription factor [4,5]. Like other bHLH transcription factors, CLOCK binds DNA and modulates transcription after dimerization with BMAL1 (brain and muscle Arnt-like protein 1; a bHLH–PAS transcription factor) [4,5]. The CLOCK–BMAL1 heterodimer drives the rhythmic transcription of other clock genes period (mPer1, mPer2 and mPer3) and cryptochrome (mCry1 and mCry2) through E-box (CACGTG) elements located in their promoters [4,5]. As the PER and CRY proteins are translated, they form multimeric complexes that are translocated to the nucleus. The CRY proteins are essential for the negative-feedback loop that regulates the central clock [7,8]. The primary function of the CRY proteins in mammals is to inhibit CLOCK–BMAL1-mediated transactivation [4,5]. Studies of clock genes have implied that oscillatory mechanisms function in peripheral organs and isolated cells, and that they are entrained to the SCN [4,5]. Although the peripheral oscillators seem to play an important role in regulating various physiological functions, the circadian oscillatory mechanism in peripheral tissues remains vague. Hundreds of tissue-specific circadian-clock-controlled genes that regulate an impressive diversity of biological processes have been identified using DNA microarray technology [9–15]. We recently identified putative CLOCK target genes in the mouse liver using microarray analyses [16]. The screened genes encoded various key physiological molecules associated with the cell cycle, immune functions and lipid metabolism, suggesting that, in addition to being a core component of the circadian oscillator, CLOCK is involved in diverse physiological functions in peripheral tissues. Several direct transcriptional targets of CLOCK have been identified. These include DBP (albumin D-site-binding protein) [17,18], vasopressin [19], prokineticin 2 [20] and PAI-1 (plasminogen activator inhibitor 1) [21].

PPARα (peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor α) is a member of the steroid/nuclear receptor superfamily and it plays a central role in the control of many genes in several pathways of lipid metabolism, including fatty acid transport, cellular uptake, intracellular binding and activation, as well as catabolism (mitochondrial β-oxidation) or storage [22]. Through binding as a heterodimer with the RXR (retinoid X receptor) to specific DNA sequences, PPREs (PPAR-response elements), PPARα regulates gene expression, such as for ACS (acyl-CoA synthase), AOX (acyl-CoA oxidase), CPTI (carnitine palmitoyl transferase I), apolipoproteins and LPL (lipoprotein lipase). Physiological responses to nuclear receptor ligands depend not only on the potency of the ligand, but also on the expression levels of nuclear receptors in specific tissues [23]. Hepatic PPARα is expressed in a circadian manner at the mRNA and protein levels in rats [24] and in mice [25]. The circadian expression of PPARα was thought to be regulated by hormonal factors, because insulin and glucocorticoids negatively and positively regulate its mRNA expression respectively [24,26].

The present study examines the expression profile of PPARα in Clock mutant mice that are deficient for the circadian clock for locomotor activity. The periodicity of homozygous Clock mutant mouse behaviour [6,27] and body temperature [28] is abnormally long. As the Clock allele is truncated and causes a deletion of 51 amino acids, the mutation presumably would not have a significant effect on the N-terminal bHLH and PAS domains, leaving CLOCK dimerization and DNA binding intact [4,5]. The mutant CLOCK protein can still form heterodimers with BMAL1 that bind to DNA, but these are deficient in transactivation [4,5]. We show that the circadian expression of PPARα is regulated directly by CLOCK protein via the E-box-rich region in the second intron in vivo and in vitro. Our results suggest that CLOCK plays an important role in lipid metabolism by regulating the circadian transactivation of PPARα in mice.

EXPERIMENTAL

Mice

Clock mutant mice were derived from animals supplied by Dr J. S. Takahashi (Department of Neurobiology and Physiology, and Center for Functional Genomics, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, U.S.A.) that originally had the Clock allele on BALB/c and C57BL/6J backgrounds. A breeding colony was established by backcrossing further with Jcl:ICR mice [27]. Insulin-dependent diabetes was induced by a single intraperitoneal injection of the β-cell toxin STZ (streptozotocin; 200 mg/kg), as described in [29]. ADX (adrenalectomized) mice were obtained from Japan SLC (Shizuoka, Japan), and were given 0.9% (w/v) NaCl ad libitum. All male mice at 8–12 weeks of age were maintained under a 12:12 h light–dark cycle (lights on at 00:00, and lights off at 12:00) for at least 2 weeks before the day of the experiment. Dissected tissues were quickly frozen and stored at −80 °C.

Northern blotting

Total RNA extracted from frozen tissues using ISOGEN (Nippon Gene Co., Tokyo, Japan) was Northern blotted as described in [27]. Random primed 32P-labelled probes were generated from cDNA fragments of mouse PPARα (bases 1121–1800; GenBank® accession number BC016892), human PPARα (bases 61–884; GenBank® accession number L07592), mPer2 (bases 1123–1830; GenBank® accession number AF036893), DBP (bases 1138–1602; GenBank® accession number J03179) and GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) (bases 133–575; GenBank® accession number M17701).

Cell culture and stimulation procedures

MEFs (mouse embryonic fibroblasts) [30] derived from wild-type and homozygous Clock mutant mice, and human lung diploid cells WI-38 [31] were maintained in DMEM (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium) (Sigma) supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS (foetal bovine serum) (Invitrogen) and antibiotics in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells (1.0×106 per 60 mm dish) were cultured for 2–3 days to reach confluence. At zero time, the cells were stimulated with 30 nM ET-1 (endothelin-1) (Sigma) [32] or with 100 nM Dex (dexamethasone) [33]. After 2 h, the medium was replaced with DMEM supplemented with 5% (v/v) FBS. At the indicated times, the cells were washed with ice-cold PBS, harvested in 1 ml of ISOGEN (Nippon Gene Co.), and stored at −80 °C before total RNA isolation.

Co-transfection and luciferase assay

Mouse NIH3T3 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS and antibiotics in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells (3.4×104 per well) were seeded in twelve-well plates 24 h before transfection using PolyFect reagent (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After 24 h, the cells were washed with PBS and harvested in 250 μl of passive lysis buffer (Promega). Luciferase activities were assayed with the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) using Turner Designs Luminometer Model TD-20/20. Putative CLOCK–BMAL1 target regions were isolated and cloned into the pGL3-Basic Vector (Promega) from +39394 to +39633 (+1 is the putative transcription start site), from +39394 to +39513, and from +39514 to +39633, for E1/E2, E1 and E2 respectively. Mouse CLOCK, BMAL1 and CRY1 expression plasmids were provided by Dr T. Todo (Radiation Biology Center, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan) [34]. Renilla luciferase plasmid was co-transfected to normalize transfection assays. The amount of DNA per well was adjusted using the pGL3-Basic Vector (Promega).

EMSA (electrophoretic mobility-shift assay)

Nuclear extract was purified from adult male mouse liver by using CelLytic NuCLEAR extraction kits (Sigma). The oligonucleotides used were as follows: E1, 5′-GCATGCACGTGCCTGTA-3′; E2, 5′-TGCCTTTACACGTGTGCCCCATA-3′; E2mut, 5′-TGCCTTTAGCTAGTTGCCCCATA-3′; E-like1, 5′-CCTGTACATGTGTGCCT-3′; E-like2, 5′-TGCCTGTACATGTGTGA-3′; E-like3, 5′-TGACAGATGTGCCTTTA-3′; E-like4, 5′-CCATACACATGCTTGTC-3′, and their corresponding complementary sequences. Underlined sequences represent canonical or non-canonical E-boxes. Double-stranded oligonucleotides were end-labelled with [α-32P]dCTP using the Random Primer DNA Labeling Kit version 2.0 (Takara Bio, Otsu, Japan). The reaction mixture (10 μl) for the EMSA containing 1 μg of nuclear extract, 1 ng of labelled probe and 50 μg/ml of poly(dI-dC)·(dI-dC), 4% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT (dithiothreitol), 50 mM NaCl and 10 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), was incubated at room temperature (25 °C) for 30 min. Competition experiments included a 500-fold excess of unlabelled double-stranded oligonucleotides that were incubated with the extract for 5 min before starting the reactions. Mouse CLOCK and BMAL1 proteins were expressed in vitro from pcDNA3.1/HisC-mCLOCK or pcDNA3.1/HisC-mBMAL1 plasmids provided by Dr T. Todo (Kyoto University) [34]. In vitro transcription and translation proceeded using the TNT Quick Coupled Transcription/Translation System (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Antibodies against the amino terminals of mCLOCK (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and against the internal region of human BMAL1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were incubated with the extract for 15 min before starting the absorption experiments. The amount of antibodies per reaction was adjusted using mouse IgG/M purified from pooled mouse sera. Samples resolved by electrophoresis on 5% (w/v) non-denaturing polyacrylamide (acrylamide/bisacrylamide ratio 29:1)/0.5× Tris/borate buffer gels were dried, and DNA–protein complexes were detected using a BAS2500 (Fuji Photo Film Co.).

ChIP (chromatin immunoprecipitation)

NIH3T3 cells expressing FLAG-tagged CLOCK were cross-linked by an incubation with formaldehyde for 10 min at 37 °C and the reaction was stopped by adding 125 mM glycine. The cells were then washed twice with ice-cold PBS, scraped into lysis buffer [5 mM Pipes (KOH), pH 8.0, 85 mM KCl and 0.5% (v/v) Nonidet P40] containing Complete™ protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), and incubated for 20 min on ice. Nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation at 2400 g for 10 min at 4 °C, resuspended in nuclear lysis buffer [50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mM EDTA, and 1% (w/v) SDS containing the same protease inhibitor cocktail as in the lysis buffer], and incubated for 10 min on ice. Lysates were sonicated to shear DNA into fragments of length 0.3–1.5 kb. To reduce the non-specific background, samples were pre-cleared by incubation with Protein A/G–agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1 h at 4 °C, with agitation. The beads were pelleted by a brief centrifugation at 2400 g for 5 min, and 20% of the total supernatant fraction was collected as total input control. The rest of the supernatant was incubated with anti-FLAG M2–agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or mouse IgG-conjugated Protein A/G–agarose beads overnight at 4 °C. Immune complexes were washed once consecutively for 3–5 min on a rotating platform with 1 ml of each of the following buffers: low salt [0.1% (w/v) SDS, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.0, and 150 mM NaCl], high salt [0.1% (w/v) SDS, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.0, and 500 mM NaCl], LiCl [0.25 M LiCl, 1% (v/v) Nonidet P40, 1% (w/v) deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA and 10 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.0], and twice with TE (10 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.0, and 1 mM EDTA). Protein was detached from the agarose beads by adding 250 μl of elution buffer [1% (w/v) SDS, 0.1 M NaHCO3 and 10 mM DTT]. Cross-links were reversed by adding 20 μl of 5 M NaCl to all reactions, including input control, and heating overnight at 65 °C. The DNA was ethanol-precipitated, digested with proteinase K, phenol-extracted, and then resuspended in TE before PCR analysis. The putative CLOCK–BMAL1 target region from +39394 to +39633 of PPARα was PCR-amplified by using the following primer set: forward primer, 5′-GTAAGCACAGGTTTCTTGCGT-3′; reverse primer, 5′-ACTCTATCTCAAAGAGTAAAG-3′. For the negative control, the 5′ flanking region of the PPARα gene (from −636 to −207) was PCR-amplified using the following primer set: forward, 5′-TGGCACCTTGGCCACCTGTT-3′; reverse, 5′-TGTCTGATTGGCTGCTGCGG-3′. The positive control consisted of the putative CLOCK–BMAL1 target region in the first intron of DBP gene (from +543 to +800) [18] was PCR-amplified using the following primer set: forward, 5′-TGACAGCTCAGTAATTCTCCC-3′; reverse, 5′-CTTGAGGACAGAGTTTAGGTG-3′. PCR analysis was performed using Platinum PCR SuperMix (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

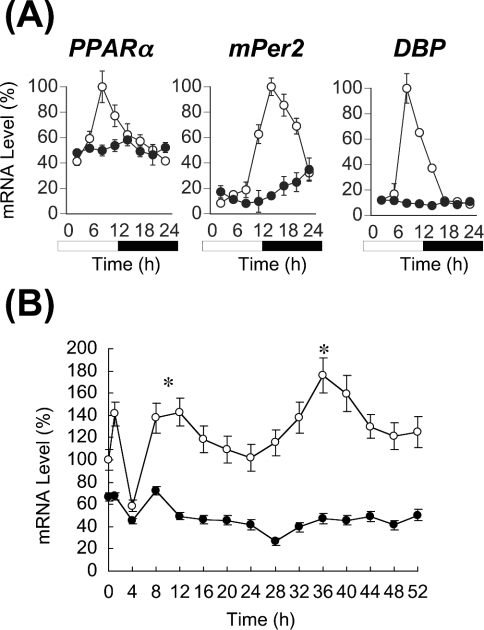

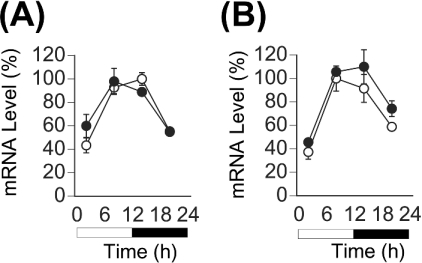

In the present study, we initially examined the expression profile of PPARα mRNA in the liver of homozygous Clock mutant mice (Figure 1A). The mutation damped the circadian expression of the clock gene mPer2 and the clock-controlled output gene DBP in the mouse liver, as we noted previously [17]. The expression of PPARα mRNA in the liver of wild-type mice was robustly circadian, and peaked at 08:00, as found in rats [24] and mice [25]. In contrast, the rhythmic expression of PPARα mRNA was eliminated from the liver of Clock mutant mice, and its mRNA was continuously expressed at the lowest levels found in wild-type mice. The acrophase (08:00) of PPARα mRNA expression in wild-type mice coincided with that of DBP. The circadian transactivation of DBP seems to be absolutely regulated by CLOCK protein via E-box elements [16,18], while that of mPer2 seems to be transactivated not only via the E-box elements but also via CREs (cAMP-responsive elements) that reside upstream of this gene [35]. The circadian expression of PPARα mRNA seemed to be regulated directly by CLOCK protein via the E-box element(s), like that of DBP mRNA [18]. Thus the present findings suggest that CLOCK is associated directly with the circadian expression of PPARα in the mouse liver.

Figure 1. CLOCK-dependent circadian expression of PPARα mRNA in vivo and in vitro.

(A) Expression of PPARα, mPer2 and DBP mRNAs in the liver of wild-type (○) and homozygous Clock mutant (●) mice. mRNA levels of genes were quantified from Northern blots. Maximal values of wild-type mice are expressed as 100% in each gene. Open bar, lights on; closed bar, lights off. Results are means±S.E.M. (n=3). Representative Northern blots are shown in Supplementary Figure 1(A) at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/386/bj3860575add.htm. (B) Circadian expression of PPARα mRNA in MEFs from wild-type (○) and homozygous Clock mutant (●) mice. At zero time, cells were stimulated with ET-1. After 2 h, medium was replaced with DMEM containing 5% FBS. Results were normalized by comparison with amount of GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase). Initial value of wild-type MEFs is expressed as 100%. Results are means±S.E.M. (n=3). One-way ANOVA demonstrated a significant rhythmicity of PPARα mRNA levels in wild-type MEFs (P<0.05). Asterisks indicate peaks of rhythmically expressed PPARα mRNA. Representative Northern blots are shown in Supplementary Figure 1(B) at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/386/bj3860575add.htm.

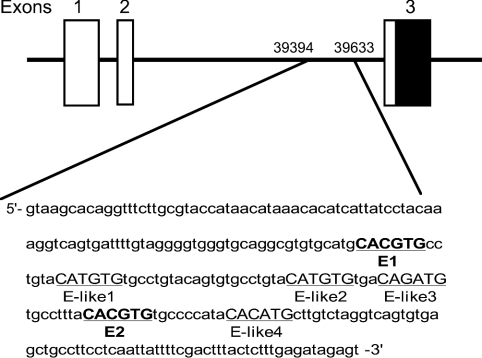

A database analysis showed that a perfect E-box (CACGTG) does not exist within 8 kb of the 5′ flanking region of the PPARα gene (results not shown). However, we discovered an E-box-rich region in the second intron of the PPARα gene (Figure 2) that contained two perfect E-boxes and four E-box-like motifs within 90 bases. The E-box elements located in the first and second introns of DBP are critical for circadian transactivation by CLOCK protein [18]. Recent convincing evidence indicates that the region immediately outside the E-box element is also important for circadian transactivation [42,43]. Such neighbouring structures seem to augment circadian transactivation via E-boxes [42,43]. Therefore we analysed the function of these sequences using a fusion gene of this region to the luciferase reporter plasmid. CLOCK and BMAL1 together, but neither of them alone, produced a major increase (more than 25-fold) in transcriptional activity of the intronic E-box-rich region (+39394 to +39633) containing reporter plasmid (see Supplementary Figure 2A at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/386/bj3860575add.htm). We also found that CLOCK dose-dependently increased the reporter gene activity (see Supplementary Figure 2B at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/386/bj3860575add.htm). This CLOCK–BMAL1-dependent transactivation of the fusion gene was severely inhibited by co-expression with CRY1 (see Supplementary Figure 2A at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/386/bj3860575add.htm), which is the negative component of CLOCK–BMAL1-derived negative-feedback loop of the circadian clock [7]. Actually, expression levels of PPARα mRNA in the liver of Cry1/Cry2 double knockout mice were elevated to the upper range of normal oscillation throughout the day (results not shown), as shown in most of the CLOCK-regulated output genes [16], suggesting that mCRY proteins negatively regulate CLOCK-dependent transactivation of the PPARα gene in vivo, as well as in vitro. The region that we used in this reporter assay included two perfect E-box elements (named from the 5′-side as E1 and E2), as described in Figure 2. Thus we generated two reporter plasmids with either the E1 or the E2 element. CLOCK–BMAL1-induced transcriptional activation via the E1 element was undetectable (see Supplementary Figure 2C at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/386/bj3860575add.htm). However, although some transcriptional activity of the E2 element (approx. 5-fold) was induced by the CLOCK–BMAL1 transcription factors, the levels were considerably lower than those generated using the complete sequence that contains both E1 and E2 E-boxes (see Supplementary Figure 2C at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/386/bj3860575add.htm). These results suggested that the neighbouring structure of these E-box elements is important for effective transactivation of the PPARα gene.

Figure 2. Location of intronic E-box-rich region in mouse PPARα gene.

Closed and open boxes show protein-coding and 5′-untranslated regions respectively. Nucleotide residues are numbered relative to transcription initiation (+1). Underlined bold capitals, perfect E-box elements; underlined capitals, E-box-like elements.

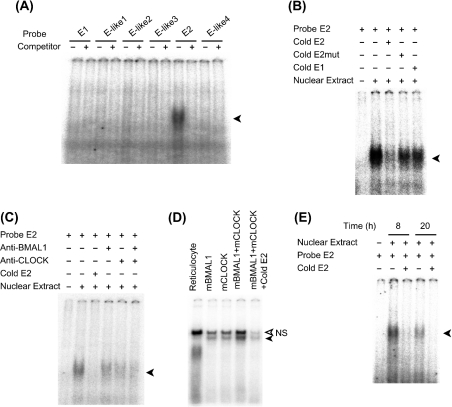

Figure 2 shows the two perfect E-boxes (named from the 5′-side as E1 and E2) and four non-canonical E-box-like elements (named from the 5′-side as E-like1 to E-like4) in the region that we used in the reporter assay (see Supplementary Figure 2 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/386/bj3860575add.htm). We also examined DNA–protein binding using a nuclear extract of the mouse liver in the presence of each oligonucleotide (Figure 3A). Only the shifted band for the E2 oligonucleotide was specifically detected. To ascertain the specificity of this E2 E-box, we prepared some different sequences for the competition. Excess unlabelled E2 probe inhibited the band shift, whereas mutated unlabelled E2 probe (6 bp mismatch) or unlabelled E1 specific probe did not (Figure 3B), suggesting that the E2 element is a specific target of the transcription factors. The shifted band for the E2 oligonucleotide was weakened when the nuclear fraction was incubated with BMAL1- or CLOCK-specific antibodies beforehand, and it was almost totally removed by prior incubation of the extract with both antibodies (Figure 3C). Antibodies targeting either BMAL1 or CLOCK could not completely remove the E2-specific band, but they decreased the E2 band (Figure 3C). MOP4 (NPAS2) and BMAL2 (CLIF) are paralogues of CLOCK and BMAL1 respectively, and behave similarly in cell and biochemical assays [21,38,44–47]. Thus transcription of the PPARα gene via this E2 element might be regulated not only by the CLOCK–BMAL1 heterodimer, but also by MOP4–BMAL1, CLOCK–BMAL2 or MOP4–BMAL2, as described for other target genes [21,45,47]. To confirm that the CLOCK–BMAL1 heterodimer binds to the E2 element, we performed an EMSA with in vitro translated CLOCK and BMAL1 proteins (Figure 3D). The presence of either CLOCK or BMAL1 generated a weak shifted band, suggesting that they can potentially bind to the E2 element as homodimers at least in vitro. However, in the presence of both proteins, DNA-binding activity was robust. These findings suggested that the E2 element is a direct target of the CLOCK–BMAL1 heterodimer. To examine the daily accumulation of nuclear proteins that can bind to the E2 element, we extracted liver nuclear fractions at day (08:00, the peak time of PPARα mRNA expression) and night (20:00). Figure 3(E) shows that the abundance of this complex was obviously (approx. 2-fold) higher with the nuclear extract at 08:00 than that observed with the extract at 20:00, suggesting that the E2 E-box element is a target for circadian transactivation of the PPARα gene in vivo.

Figure 3. E2 E-box is a direct target of the CLOCK–BMAL1 heterodimer in vitro.

(A) EMSA was performed with 1 μg of mouse liver nuclear extract and E-box or non-canonical E-box-containing oligonucleotides as follows: E1, 5′-GCATGCACGTGCCTGTA-3′; E2, 5′-TGCCTTTACACGTGTGCCCCATA-3′; E-like1, 5′-CCTGTACATGTGTGCCT-3′; E-like2, 5′-TGCCTGTACATGTGTGA-3′; E-like3, 5′-TGACAGATGTGCCTTTA-3′; E-like4, 5′-CCATACACATGCTTGTC-3′ and their corresponding complementary sequences. Underlined sequences represent canonical or non-canonical E-boxes. (B) The band for E2 oligonucleotide shifted when the nuclear fraction was incubated with unlabelled mutated oligonucleotide (E2mut, 5′-TGCCTTTAGCTAGTTGCCCCATA-3′) or unlabelled E1 probe at 500-fold molar excess. (C) The shifted band for E2 oligonucleotide was weakened when nuclear fraction was incubated with BMAL1- or CLOCK-specific antibodies. (D) The shifted band for E2 oligonucleotide was detectable when E2 probe was incubated with indicated in vitro translated proteins. Open arrowhead indicates non-specific (NS) band. (E) Day/night difference of signal strength of E2-specific shifted band. Nuclear fractions were extracted from the liver of three mice at day (08:00) and night (20:00). This experiment included 1 μg of pooled nuclear extract. Closed arrowhead indicates specific shifted band.

Cultured cells, such as rat-1 fibroblasts [36], NIH-3T3 [37], vascular smooth muscle cells [38,39], MEFs [32], HeLa [40] and WI-38 [31], have served as models for studies of the peripheral clock system. Circadian gene expression in these cells is induced not only by serum shock [36], but also by many chemicals that activate various signal transduction pathways [32,33,39,41]. To understand whether the circadian expression of PPARα mRNA in vivo is an intrinsic property of peripheral clocks, we examined the temporal expression of PPARα mRNA in MEFs isolated from wild-type and homozygous Clock mutant mice (Figure 1B). We triggered oscillations using the vasoconstricting peptide ET-1 as described by Yagita et al. [32]. As in the mouse liver, PPARα mRNA was expressed in a circadian manner in fibroblasts obtained from wild-type mice, but was extremely suppressed in the Clock-deficient fibroblasts, suggesting that CLOCK is involved in the circadian transactivation of PPARα at the level of peripheral oscillators in mice.

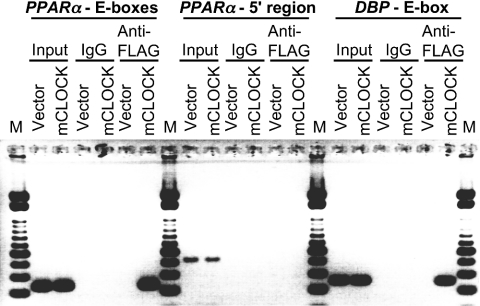

To examine the association of CLOCK with the intronic E-box-rich region of PPARα (from +39394 to +39633) in vivo, we performed ChIP assays using NIH3T3 cells expressing FLAG-tagged CLOCK or FLAG vector only (Figure 4). ChIP was performed using anti-FLAG antibody and analysed by PCR amplification of total DNA before immunoprecipitation (input), non-specific immunoprecipitated DNA (IgG) or specifically immunoprecipitated DNA (anti-FLAG). For the negative control, the 5′ flanking region of the PPARα gene (from −636 to −207) that contains no E-box (-like) element was PCR-amplified. For the positive control, the putative CLOCK–BMAL1 target region in the first intron of the DBP gene (from +543 to +800) [18] was PCR-amplified. The intronic E-box-rich region of PPARα and the putative CLOCK–BMAL1 target region in the first intron of DBP were amplified in DNA recovered from a ChIP reaction performed on chromatin lysates from the cells expressing FLAG-tagged CLOCK protein, but not from control lysates. These data support the view that CLOCK associates in vivo with the E-box-rich region in the second intron of PPARα.

Figure 4. CLOCK associates with the E-box-rich region of the PPARα gene in vivo.

PCR proceeded using primer pairs that specifically detect the E-box-rich region of the PPARα gene, the 5′ flanking region of the PPARα gene that contained no E-box or E-box-like elements, and the putative CLOCK–BMAL1 target region in the first intron of DBP gene. DNA templates were either subcloned total chromatin (Input) or immunoprecipitated chromatin (mouse IgG or Anti-FLAG). Chromatin samples were prepared from NIH3T3 cells expressing FLAG-tagged CLOCK or empty FLAG vector. PCR products were electrophoresed through a non-denaturing 2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide, and photographed. Arrowhead indicates specific shifted band for intronic E-box-rich region. Lane M, molecular mass standards.

The circadian expression of PPARα was thought to be regulated by hormonal factors, because insulin and glucocorticoid negatively and positively regulate the mRNA expression respectively [24,26]. Thus, to evaluate whether insulin is involved in the circadian expression of PPARα, we examined the expression profile of PPARα mRNA in the liver of STZ-induced diabetic mice (Figure 5A). Serum insulin was undetectable at all time points in all mice given STZ (results not shown) as described in [29,48]. The circadian expression of PPARα mRNA was not affected in the diabetic mice like other clock or clock-controlled genes that are regulated by CLOCK–BMAL1 transcription factors [29]. To evaluate whether glucocorticoid is involved in the circadian expression of PPARα, we examined the expression profile of PPARα mRNA in the liver of ADX mice (Figure 5B). Adrenalectomy, however, did not affect the circadian expression of PPARα mRNA in the liver, suggesting that endogenous glucocorticoids are not essential for the circadian expression of PPARα in mice. Taken together, these findings suggest that the circadian expression of PPARα is governed by clock molecules, such as CLOCK and BMAL1, in the mouse liver, although the mRNA expression levels are affected by exogenous insulin or glucocorticoid in vitro [24,26] and in vivo [24].

Figure 5. Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and adrenalectomy do not affect circadian expression of PPARα mRNA in the mouse liver.

(A) Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus was induced by a single intraperitoneal injection of STZ (200 mg/kg), which is toxic to β-cells. Control (○) and STZ-induced diabetic (●) mice did not significantly differ. (B) ADX mice were maintained with 0.9% NaCl supplements. Control (○) and ADX (●) mice did not significantly differ. Open bar, lights on; closed bar, lights off. The maximum value of control mice is expressed as 100% in each graph. Results are means±S.E.M. (n=3). Representative Northern blots are shown in Supplementary Figure 3 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/386/bj3860575add.htm.

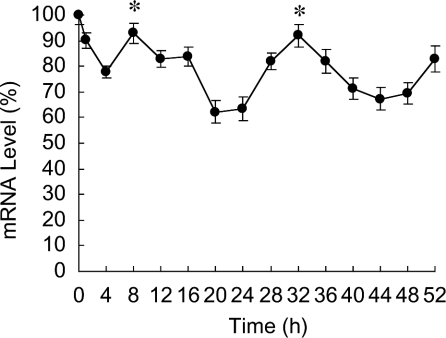

To determine whether the circadian property of PPARα expression is conserved in human tissues, we performed the in vitro oscillation experiment using the human embryonic lung diploid fibroblast line, WI-38 (Figure 6). We triggered the oscillation using 100 nM Dex [33]. The WI-38 fibroblasts expressed PPARα mRNA in a circadian manner like clock genes, such as Per1, Per2, Per3 and BMAL1 [31]. Although PPARα is expressed in some rodent tissues in a circadian manner [24,25], the present paper is the first report to describe the circadian expression of PPARα in human tissue. Three E-boxes are positioned within 8 kb of the 5′ flanking region of the human PPARα gene and 15 (four in the first intron, four in the second, two in the third and five in the sixth) are located within the gene. Some of these E-box elements might be important for the circadian expression of PPARα in human tissues, although the mouse E-box-rich region in the second intron described in the present study is not conserved in the human genome. Further investigation of the circadian regulation of human PPARα expression should reveal critical findings that will help to elucidate the circadian control mechanisms of human lipid metabolism.

Figure 6. Circadian expression of human PPARα mRNA in WI-38 fibroblasts.

At time 0 h, WI-38 fibroblasts were stimulated with Dex. After 2 h, medium was replaced with DMEM containing 5% FBS. Results were normalized by comparison with amount of GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase). The initial value of PPARα mRNA is shown as 100%. Results are means±S.E.M. (n=3). One-way ANOVA demonstrated significant rhythmicity of PPARα mRNA levels (P<0.05). Asterisks indicate peaks of rhythmically expressed PPARα mRNA. Representative Northern blots of total RNA from fibroblasts after Dex stimulation are shown in Supplementary Figure 4 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/386/bj3860575add.htm.

Evidence has emerged that PPARα regulates a variety of target genes involved in cellular lipid catabolism and storage [49,50]. Since daily variations in lipogenic and cholesterogenic gene expression are attenuated or abolished in PPARα-null mice [25], PPARα seems to be an important mediator for the circadian regulation of lipid metabolism. Thus CLOCK-regulated circadian transactivation of the PPARα gene might play a key role in circadian changes in the physiological responses of PPARα, although the activity of this nuclear receptor seems to largely depend on the potency of ligands in specific tissues [22].

The dimerization partner of PPARα, RXRα, interacts with CLOCK protein in a ligand-dependent manner and inhibits CLOCK–BMAL1-dependent transactivation via the E-box element [38]. Thus PPAR might also be associated with the transcription/translation-based circadian clock mechanism in a ligand-specific manner by modifying CLOCK–BMAL1-dependent transactivation via the E-box element in peripheral tissues. We found that the specific ligands for PPARα affect the expression of clock genes in vitro (H. Shirai, K. Oishi and N. Ishida, unpublished work). Further elucidation of the molecular mechanism that regulates the circadian expression of PPARα will provide new insight into the daily processes involved in lipid metabolism.

Online data

Acknowledgments

We thank J. S. Takahashi (Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, U.S.A.) for the gifts of Clock mutant mice. We thank Takeshi Todo (Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan) for supplying mouse Clock, BMAL1 and Cry1 expression plasmids; Gen-ichi Atsumi (Teikyo University, Kanagawa, Japan) for MEF preparation; Koyomi Miyazaki, Satoru Suzuki and Ikuko Kodomari (AIST), and Shuichi Horie, Gen-ichi Atsumi and Naoki Ohkura (Teikyo University, Kanagawa, Japan) for helpful discussion. We also thank Manami Kasamatsu, Noriko Amagai, Kazuko Suzuki and Chisato Iitaka (AIST) for excellent technical assistance. This project was supported by an operational subsidy from AIST, an internal grant of AIST, and a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (15700492) to K. O. from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT).

References

- 1.Dunlap J. C. Molecular bases for circadian clocks. Cell. 1999;96:271–290. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80566-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ishida N., Miyazaki K., Sakai T. Circadian rhythm biochemistry: from protein degradation to sleep and mating. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;286:1–5. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zordan M., Costa R., Macino G., Fukuhara C., Tosini G. Circadian clocks: what makes them tick? Chronobiol. Int. 2000;17:433–451. doi: 10.1081/cbi-100101056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pando M. P., Sassone-Corsi P. Signaling to the mammalian circadian clocks: in pursuit of the primary mammalian circadian photoreceptor. Science STKE. 2001;2001:RE16. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.107.re16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reppert S. M., Weaver D. R. Molecular analysis of mammalian circadian rhythms. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2001;63:647–676. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vitaterna M. H., King D. P., Chang A. M., Kornhauser J. M., Lowrey P. L., McDonald J. D., Dove W. F., Pinto L. H., Turek F. W., Takahashi J. S. Mutagenesis and mapping of a mouse gene, Clock, essential for circadian behavior. Science. 1994;264:719–725. doi: 10.1126/science.8171325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kume K., Zylka M. J., Sriram S., Shearman L. P., Weaver D. R., Jin X., Maywood E. S., Hastings M. H., Reppert S. M. mCRY1 and mCRY2 are essential components of the negative limb of the circadian clock feedback loop. Cell. 1999;98:193–205. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vitaterna M. H., Selby C. P., Todo T., Niwa H., Thompson C., Fruechte E. M., Hitomi K., Thresher R. J., Ishikawa T., Miyazaki J., et al. Differential regulation of mammalian period genes and circadian rhythmicity by cryptochromes 1 and 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:12114–12119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akhtar R. A., Reddy A. B., Maywood E. S., Clayton J. D., King V. M., Smith A. G., Gant T. W., Hastings M. H., Kyriacou C. P. Circadian cycling of the mouse liver transcriptome, as revealed by cDNA microarray, is driven by the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:540–550. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00759-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen L., Madura K. Rad23 promotes the targeting of proteolytic substrates to the proteasome. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:4902–4913. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.13.4902-4913.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delaunay F., Laudet V. Circadian clock and microarrays: mammalian genome gets rhythm. Trends Genet. 2002;18:595–597. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(02)02794-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Panda S., Antoch M. P., Miller B. H., Su A. I., Schook A. B., Straume M., Schultz P. G., Kay S. A., Takahashi J. S., Hogenesch J. B. Coordinated transcription of key pathways in the mouse by the circadian clock. Cell. 2002;109:307–320. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00722-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Storch K. F., Lipan O., Leykin I., Viswanathan N., Davis F. C., Wong W. H., Weitz C. J. Extensive and divergent circadian gene expression in liver and heart. Nature (London) 2002;417:78–83. doi: 10.1038/nature744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ueda H. R., Chen W., Adachi A., Wakamatsu H., Hayashi S., Takasugi T., Nagano M., Nakahama K., Suzuki Y., Sugano S., et al. A transcription factor response element for gene expression during circadian night. Nature (London) 2002;418:534–539. doi: 10.1038/nature00906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y., Osterbur D. L., Megaw P. L., Tosini G., Fukuhara C., Green C. B., Besharse J. C. Rhythmic expression of Nocturnin mRNA in multiple tissues of the mouse. BMC Dev. Biol. 2001;1:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oishi K., Miyazaki K., Kadota K., Kikuno R., Nagase T., Atsumi G., Ohkura N., Azama T., Mesaki M., Yukimasa S., et al. Genome-wide expression analysis of mouse liver reveals CLOCK-regulated circadian output genes. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:41519–41527. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304564200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oishi K., Fukui H., Ishida N. Rhythmic expression of BMAL1 mRNA is altered in Clock mutant mice: differential regulation in the suprachiasmatic nucleus and peripheral tissues. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;268:164–171. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ripperger J. A., Shearman L. P., Reppert S. M., Schibler U. CLOCK, an essential pacemaker component, controls expression of the circadian transcription factor DBP. Genes Dev. 2000;14:679–689. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin X., Shearman L. P., Weaver D. R., Zylka M. J., de Vries G. J., Reppert S. M. A molecular mechanism regulating rhythmic output from the suprachiasmatic circadian clock. Cell. 1999;96:57–68. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80959-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng M. Y., Bullock C. M., Li C., Lee A. G., Bermak J. C., Belluzzi J., Weaver D. R., Leslie F. M., Zhou Q. Y. Prokineticin 2 transmits the behavioural circadian rhythm of the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Nature (London) 2002;417:405–410. doi: 10.1038/417405a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maemura K., de la Monte S. M., Chin M. T., Layne M. D., Hsieh C. M., Yet S. F., Perrella M. A., Lee M. E. CLIF, a novel cycle-like factor, regulates the circadian oscillation of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:36847–36851. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000629200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Desvergne B., Wahli W. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: nuclear control of metabolism. Endocr. Rev. 1999;20:649–688. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.5.0380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blanquart C., Barbier O., Fruchart J. C., Staels B., Glineur C. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) turnover by the ubiquitin-proteasome system controls the ligand-induced expression level of its target genes. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:37254–37259. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110598200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lemberger T., Saladin R., Vazquez M., Assimacopoulos F., Staels B., Desvergne B., Wahli W., Auwerx J. Expression of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α gene is stimulated by stress and follows a diurnal rhythm. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:1764–1769. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.3.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel D. D., Knight B. L., Wiggins D., Humphreys S. M., Gibbons G. F. Disturbances in the normal regulation of SREBP-sensitive genes in PPARα-deficient mice. J. Lipid Res. 2001;42:328–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steineger H. H., Sorensen H. N., Tugwood J. D., Skrede S., Spydevold O., Gautvik K. M. Dexamethasone and insulin demonstrate marked and opposite regulation of the steady-state mRNA level of the peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) in hepatic cells. Hormonal modulation of fatty-acid-induced transcription. Eur. J. Biochem. 1994;225:967–974. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.0967b.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oishi K., Miyazaki K., Ishida N. Functional CLOCK is not involved in the entrainment of peripheral clocks to the restricted feeding: entrainable expression of mPer2 and BMAL1 mRNAs in the heart of Clock mutant mice on Jcl:ICR background. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;298:198–202. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02427-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ochi M., Sono S., Sei H., Oishi K., Kobayashi H., Morita Y., Ishida N. Sex difference in circadian period of body temperature in Clock mutant mice with Jcl/ICR background. Neurosci. Lett. 2003;347:163–166. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00688-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oishi K., Ohkura N., Kasamatsu M., Fukushima N., Shirai H., Matsuda J., Horie S., Ishida N. Tissue-specific augmentation of circadian PAI-1 expression in mice with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Thromb. Res. 2004;114:129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Todaro G. J., Green H. Quantitative studies of the growth of mouse embryo cells in culture and their development into established lines. J. Cell. Biol. 1963;17:299–313. doi: 10.1083/jcb.17.2.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyazaki K., Nagase T., Mesaki M., Narukawa J., Ohara O., Ishida N. Phosphorylation of clock protein PER1 regulates its circadian degradation in normal human fibroblasts. Biochem. J. 2004;380:95–103. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yagita K., Tamanini F., van Der Horst G. T., Okamura H. Molecular mechanisms of the biological clock in cultured fibroblasts. Science. 2001;292:278–281. doi: 10.1126/science.1059542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balsalobre A., Brown S. A., Marcacci L., Tronche F., Kellendonk C., Reichardt H. M., Schutz G., Schibler U. Resetting of circadian time in peripheral tissues by glucocorticoid signaling. Science. 2000;289:2344–2347. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5488.2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kobayashi Y., Ishikawa T., Hirayama J., Daiyasu H., Kanai S., Toh H., Fukuda I., Tsujimura T., Terada N., Kamei Y., et al. Molecular analysis of zebrafish photolyase/cryptochrome family: two types of cryptochromes present in zebrafish. Genes Cells. 2000;5:725–738. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2000.00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Travnickova-Bendova Z., Cermakian N., Reppert S. M., Sassone-Corsi P. Bimodal regulation of mPeriod promoters by CREB-dependent signaling and CLOCK/BMAL1 activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:7728–7733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102075599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Balsalobre A., Damiola F., Schibler U. A serum shock induces circadian gene expression in mammalian tissue culture cells. Cell. 1998;93:929–937. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81199-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akashi M., Nishida E. Involvement of the MAP kinase cascade in resetting of the mammalian circadian clock. Genes Dev. 2000;14:645–649. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McNamara P., Seo S. P., Rudic R. D., Sehgal A., Chakravarti D., FitzGerald G. A. Regulation of CLOCK and MOP4 by nuclear hormone receptors in the vasculature: a humoral mechanism to reset a peripheral clock. Cell. 2001;105:877–889. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00401-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nonaka H., Emoto N., Ikeda K., Fukuya H., Rohman M. S., Raharjo S. B., Yagita K., Okamura H., Yokoyama M. Angiotensin II induces circadian gene expression of clock genes in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Circulation. 2001;104:1746–1748. doi: 10.1161/hc4001.098048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Curtis A. M., Seo S. B., Westgate E. J., Rudic R. D., Smyth E. M., Chakravarti D., FitzGerald G. A., McNamara P. Histone acetyltransferase-dependent chromatin remodeling and the vascular clock. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:7091–7097. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311973200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Balsalobre A., Marcacci L., Schibler U. Multiple signaling pathways elicit circadian gene expression in cultured Rat-1 fibroblasts. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:1291–1294. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00758-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Munoz E., Baler R. The circadian E-box: when perfect is not good enough. Chronobiol. Int. 2003;20:371–388. doi: 10.1081/cbi-120022525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Munoz E., Brewer M., Baler R. Circadian transcription: thinking outside the E-box. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:36009–36017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203909200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dudley C. A., Erbel-Sieler C., Estill S. J., Reick M., Franken P., Pitts S., McKnight S. L. Altered patterns of sleep and behavioral adaptability in NPAS2-deficient mice. Science. 2003;301:379–383. doi: 10.1126/science.1082795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hogenesch J. B., Gu Y. Z., Jain S., Bradfield C. A. The basic-helix–loop–helix–PAS orphan MOP3 forms transcriptionally active complexes with circadian and hypoxia factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:5474–5479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reick M., Garcia J. A., Dudley C., McKnight S. L. NPAS2: an analog of clock operative in the mammalian forebrain. Science. 2001;293:506–509. doi: 10.1126/science.1060699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schoenhard J. A., Smith L. H., Painter C. A., Eren M., Johnson C. H., Vaughan D. E. Regulation of the PAI-1 promoter by circadian clock components: differential activation by BMAL1 and BMAL2. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2003;35:473–481. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(03)00051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oishi K., Kasamatsu M., Ishida N. Gene- and tissue-specific alterations of circadian clock gene expression in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice under restricted feeding. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;317:330–334. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cherkaoui-Malki M., Meyer K., Cao W. Q., Latruffe N., Yeldandi A. V., Rao M. S., Bradfield C. A., Reddy J. K. Identification of novel peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) target genes in mouse liver using cDNA microarray analysis. Gene Expression. 2001;9:291–304. doi: 10.3727/000000001783992533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamazaki K., Kuromitsu J., Tanaka I. Microarray analysis of gene expression changes in mouse liver induced by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α agonists. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;290:1114–1122. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.