Abstract

TLR4 (Toll-like receptor 4) is essential for sensing the endotoxin of Gram-negative bacteria. Mutations or deletion of the TLR4 gene in humans or mice have been associated with altered predisposition to or outcome of Gram-negative sepsis. In the present work, we studied the expression and regulation of the Tlr4 gene of mouse. In vivo, TLR4 levels were higher in macrophages compared with B, T or natural killer cells. High basal TLR4 promoter activity was observed in RAW 264.7, J774 and P388D1 macrophages transfected with a TLR4 promoter reporter vector. Analysis of truncated and mutated promoter constructs identified several positive [two Ets (E twenty-six) and one AP-1 (activator protein-1) sites] and negative (a GATA-like site and an octamer site) regulatory elements within 350 bp upstream of the transcriptional start site. The myeloid and B-cell-specific transcription factor PU.1 bound to the proximal Ets site. In contrast, none among PU.1, Ets-1, Ets-2 and Elk-1, but possibly one member of the ESE (epithelium-specific Ets) subfamily of Ets transcription factors, bound to the distal Ets site, which was indispensable for Tlr4 gene transcription. Endotoxin did not affect macrophage TLR4 promoter activity, but it decreased TLR4 steady-state mRNA levels by increasing the turnover of TLR4 transcripts. TLR4 expression was modestly altered by other pro- and anti-inflammatory stimuli, except for PMA plus ionomycin which strongly increased promoter activity and TLR4 mRNA levels. The mouse and human TLR4 genes were highly conserved. Yet, notable differences exist with respect to the elements implicated in gene regulation, which may account for species differences in terms of tissue expression and modulation by microbial and inflammatory stimuli.

Keywords: Ets transcription factor, GATA-like, innate immunity, macrophage, RNA stability, Toll-like receptor 4

Abbreviations: AP-1, activator protein-1; BAEC, bovine aortic endothelial cells; DBD, DNA-binding domain; Dex, dexamethasone; EMSA, electrophoretic mobility-shift assay; Ets, E twenty-six; ESE, epithelium-specific Ets; Etsd, distal Ets; Etsp, proximal Ets; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; IRF, IFN regulatory factor; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; LBP, LPS-binding protein; mAb, monoclonal antibody; MEF, myeloid Elf-1-like factor; NK cells, natural killer cells; Oct-1, octamer 1; PEST, proline-, glutamate-, serine- and threonine-rich; PGN, peptidoglycan; SRE, serum response element; TAD, transactivation domain; TLR, Toll-like receptor; TNF, tumour necrosis factor

INTRODUCTION

The innate immune system provides the first line of host defences against microbial pathogens. Detection of invasive microorganisms by the innate immune system is mediated by soluble factors, such as the LBP [LPS (lipopolysaccharide)-binding protein], components of the alternative and mannose-binding-lectin complement pathways and by germ-line encoded pattern recognition receptors [such as CD14 and TLRs (Toll-like receptors)] expressed by a broad range of immune and non-immune cells. On binding the ligand, these receptors elicit a cascade of intracellular signalling events resulting in the release of effector molecules, including pro-inflammatory cytokines. These mediators serve to recruit and activate immune cells, enhancing bactericidal capacities of phagocytes, and thereby facilitating clearance of pathogens [1,2].

Mononuclear phagocytic cells, such as macrophages and dendritic cells, are present in virtually all tissues, where they act as sentinels of the immune system to detect invading microbial pathogens. Immune cells sense Gram-negative bacteria primarily through the recognition of LPS, a glycolipid component of the outer bacterial membrane. Studies of the interaction between LPS and host cells have led to the identification of key molecules involved in LPS recognition, such as the LBP and CD14. LBP dissociates aggregates of LPS and transfers LPS monomers to CD14, expressed on the surface of myelomonocytic cells. Binding of LPS to CD14 induces cell activation and cytokine production. LBP can also transfer LPS to soluble CD14 that serves to activate CD14-negative cells, such as endothelial cells or to lipoproteins, in which case it results in the inactivation of LPS (reviewed in [3]). Given that membrane CD14 is a glycerophosphatidylinositol-anchored protein, it cannot be the signal-transducing molecule of the LPS receptor complex.

Recently, TLRs have been identified as mammalian homologues of the Drosophilia Toll, found to be essential for the recognition of fungi and Gram-positive bacteria in the fruit fly [4]. In mammals, 11 TLRs have been identified. Positional cloning analyses have linked the LPS unresponsive phenotype of C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr strains of mice to missense and null mutations of the Tlr4 gene respectively [5,6]. The essential role played by TLR4 in LPS signalling was confirmed by studies showing that TLR4 knockout mice do not respond to LPS, and that reintroduction of TLR4 in TLR4-negative cells restored LPS responsiveness [7,8]. In agreement with an essential role for TLR4 in the sensing of LPS and Gram-negative bacteria and mounting of the innate immune response, mice homozygous for a defective Tlr4 gene have long been known to be exquisitely sensitive to otherwise non-lethal challenges with Gram-negative bacteria [9]. Recent studies have indicated that MD-2, a secreted protein that binds to the extracellular domain of TLR4, increases cellular response to LPS [10]. MD-2 knockout mice are resistant to endotoxic shock, but susceptible to Salmonella typhimurium infections [11].

Besides TLR4, other members of the TLR family have been shown to also function as sensors of microbial products. TLR2 detects lipoproteins and zymosan. TLR1 facilitates recognition of lipoprotein by TLR2, and TLR6 co-operates with TLR2 to recognize diacylated lipopeptides. TLR3 recognizes double-stranded RNA, whereas TLR7 and TLR8 mediate species-specific recognition of single-stranded RNA. TLR5 senses bacterial flagellin from Gram-positive and -negative bacteria and TLR9 detects unmethylated CpG motifs from bacterial DNA. Finally, mouse TLR11 is implicated in the recognition of uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains (reviewed in [12] and [13–15]). Consistent with the essential role played by TLRs in the sensing of microbial products and induction of host–innate immune defence responses, several polymorphisms of TLR genes or variations in TLR expression have been shown to be associated with predisposition to or outcome of bacterial sepsis in humans [16–18]. In contrast, relatively little information is available on the expression of mouse TLR genes or proteins. We therefore studied the transcriptional regulation of the mouse Tlr4 gene, especially as in vitro and in vivo mouse models of sepsis play a critical role in the preclinical evaluation of novel treatment strategies for patients with severe sepsis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and reagents

The murine macrophage RAW 264.7 and J774 cell lines and BAEC (bovine aortic endothelial cells) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen, Basel, Switzerland) containing 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Seromed, Berlin, Germany). The mouse macrophage P388D1 cell lines and the NIH-3T3 mouse fibroblasts were cultured in Dubelcco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) containing 10% fetal calf serum. All media were supplemented with penicillin and streptomycin (Invitrogen). In selected experiments, RAW 264.7 macrophages were stimulated with 100 ng/ml S. minnesota ultra pure LPS (List Biologicals Laboratories, Campbell, CA, U.S.A.), 10 ng/ml TNF (tumour necrosis factor; Roche Diagnostics, Rotkreuz, Switzerland), 100 units/ml IFN (interferon)-γ (R&D Systems, Abingdon, U.K.), 5 ng/ml PMA (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.) plus 25 ng/ml ionomycin (Sigma), 2 μM CpG oligodeoxynucleotide 1826 (Coley Pharmaceutical Group, Wellesley, MA, U.S.A.), 108 CFU/ml heat-killed E. coli O111:B4 or 108 CFU/ml Staphylococcus aureus AW7, 10 μg/ml PGN (peptidoglycan; Sigma) and 100 nM Dex (dexamethasone; Sigma).

Flow cytometric analysis

After blocking Fc receptors with 2.4G2 hybridoma supernatant, expression of membrane-bound TLR4 on C57BL/6 splenocytes and on thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal macrophages, isolated from TLR4+/+ and TLR4−/− C57BL/6 mice (a gift from Dr S. Akira, Hyogo College of Medicine, Hyogo, Japan), was evaluated by incubating cells for 20 min with a biotinylated rat anti-mouse TLR4-MD-2 mAb (monoclonal antibody; clone MTS510, [19]) or an isotype-matched control mAb. TLR4 expression by splenocytes was revealed using streptavidin allophycocyanin (Becton Dickinson, Erembodegem, Belgium). Splenic subpopulations were identified by counterstaining using FITC-conjugated anti-B220 (CD45R), CyChrome-conjugated anti-CD3 and phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-NK1.1 (Ly-55) mAbs (Becton Dickinson). TLR4 expression by peritoneal macrophages was revealed using streptavidin-FITC (Biosource, Camarillo, CA, U.S.A.). Macrophages were counterstained using phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-Mac1 (CD11b; Becton Dickinson). Analyses were performed on a FACSCalibur™ (Becton Dickinson).

RNA analysis

Expression of TLR4, PU.1 and GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) mRNA was assessed by Northern blotting. Briefly, 10 μg of RNA was electrophoresed through 1% agarose–formaldehyde gels, transferred on to nylon membranes (Hybond N+; Amersham Biosciences, Arlington Heights, IL, U.S.A.) and hybridized overnight with [32P] random-labelled TLR4, PU.1 and GAPDH DNA probes. Membranes were washed and exposed to X-ray films for autoradiography. The PU.1 probe was isolated from a PU.1 expression plasmid [20]. Murine and bovine TLR4 and GAPDH probes were obtained by PCR amplification of RAW 264.7 and BAEC cDNA (primers used for PCR are listed in Table 1) respectively. The identity of the amplicons was confirmed by sequencing. ESE-1 (epithelium-specific Ets-1) and GAPDH expression in RAW 264.7 macrophages was assessed by reverse transcriptase–PCR using hot start Taq DNA polymerase (Qiagen, Basel, Switzerland). Amplification conditions were 94 °C for 15 s, 55 °C for 15 s and 72 °C for 30 s for either 30 cycles (GAPDH) or 40 cycles (ESE-1). To assess TLR4 mRNA half-life, RAW 264.7 macrophages were stimulated for 2 h with or without LPS and then treated with 10 μg/ml actinomycin D (Roche Diagnostics). TLR4 mRNA decay was measured by Northern blotting.

Table 1. Oligonucleotides used in the present study.

| Oligonucleotide | 5′→3′ sequence |

|---|---|

| For gene expression and probe synthesis | |

| Mouse Tlr4 | Sense AGCTTGAATCCCTGCATAGAT |

| Antisense GTTCTCCTCAGGTCCAAGTTGCCGTTTC | |

| Mouse Ese-1 | Sense GGTGGAAGTGATGTGGAC |

| Antisense CGGGGTGGATTAGGATGT | |

| Mouse Gapdh | Sense GGTCATCCATGACAACTTTGG |

| Antisense CACCTTCTTGATGTCATCAT | |

| Bovine TLR4 | Sense CTACAAAATCCCCGACAA |

| Antisense ATCCAAGTGCTCCAGGTT | |

| Bovine GAPDH | Sense ATCCTGCCAACATCAAGT |

| Antisense GGTCATAAGTCCCTCCAC | |

| For promoter construct* | |

| T4PS2 | Sense GAAGATCTGCATTACAGACATTGATTGG |

| T4PAS1 | Antisense GAAGATCTCAGGCAGGAGAAGAACAGTG |

| T4PS3 | Sense GAAGATCTGATTGAGAACTGAGAACTGC |

| T4PAS2 | Antisense GAAGATCTAGGAAGAAGGCGTTTGCTGA |

| 3×Etsd | Sense GATCTGAAAATATGTTCCTCTAGGAAAATAT |

| GTTCCTCTAGGAAAATATGTTCCTCTAGA | |

| Antisense AGCTTCTAGAGGAACATATTTTCCTAGAGG | |

| AACATATTTTCCTAGAGGAACATATTTTCA | |

| For mutagenesis and EMSA† | |

| Tlr4-derived oligonucleotides: | |

| AP-1 | AGAGGTCAGATGACTTCCTGGGATCA |

| GATA-like | GGCAACTGATGATATCTTCATCCG |

| Oct | AAAAGTGAGAATGCTAAGGTTGGCAC |

| Etsd | GAGAAAATATGTTCCTCTAGTCTGAAA |

| Etsp | AGCCAGCTTCCTCTTGCTGTTCC |

| AP-1 mt | GCCCAGAGGTCAGACCACTTCCTGGG |

| GATA mt | CAAGACACGGCAACTGAACTTATCTTCATCCTGGG |

| Oct mt | CCAAAAGTGAGAATGCTCGAGTTGGCACTCTCAC |

| Etsd m1 | GAGCGCATATGTTCCTCTAGTCTGAAACATCC |

| Etsd m2 | GAGAAAGCTTGTTCCTCTAGTCTGAAACATCC |

| Etsd m3 | GAGAAAATACCGTCCTCTAGTCTGAAACATCC |

| Etsd m4 | GAGAAAATATGTAGTTCTAGTCTGAAACATCC |

| Etsd m5 | GAGAAAATATGTTCCCAGAGTCTGAAACATCC |

| Etsd m6 | GAGAAAATATGTTCCTCTGTCCTGAAACATCC |

| Etsd m7 | GAGAAAATATGTTCCTCTAGTAATAAACATCC |

| Etsp mt | AAAGCCAGCTAGTTCTTGCTGTTCC |

| Other oligonucleotides: | |

| IL-12 PU.1 | GAAGTCATTTCCTCTTAGTCCC |

| IL-18 PU.1 | GGGTTCTTCCTCATTCTT |

| Ets | GAAGTCACTTCCGGTTAGTTCC |

| Elk | GAAGTCGCATCCGGTTAGTTCC |

| SRE-1 | GGTCCTTCCTGCTCCTTATATGGCATTTCCGGGTC |

| GATA cs | GGGTTGATAACAGATGATAACCC |

| Oct cs | GGTCGAATGCAAATCACTAGACGT |

* BglII restriction site is underlined.

† Base substitutions are underlined. cs, consensus.

Plasmid preparation

A 3 kb fragment (−2715/+223) from the mouse Tlr4 gene (GenBank® accession no. AF177767) was amplified from C57BL/6 genomic DNA using T4PS2 and T4PAS1 oligonucleotides (Table 1) and the expanded long template PCR system (Roche Diagnostics) [21]. After A-tailing, the amplicon was cloned into the pGEM®-T vector (Promega, Madison, WI, U.S.A.) and sequenced. The fragment was exised from pGEM®-T using NotI, blunt-ended and subcloned in the filled-in BglII restriction site from the pGL3-basic vector (Promega). A 1 kb fragment corresponding to the 3′-portion of −2715/+223 was exised from pGEM®-T using BglII and subcloned into the BglII restriction site from the pGL3-basic vector (construct −743/+223). Constructs −518/+223 and −336/+223 were obtained after digestion of −2715/+223 with PstI–XhoI and EcoRV–XhoI, and subsequent religation. Additional deletion mutants were obtained on digestion of −2715/+223 with exonuclease III. After nuclease S1 treatment, DNA was recircularized and used to transform E. coli. Clones of various size were sequenced to identify the upstream limit of the new constructs. Constructs −541/+223 and −541/−71 were generated by PCR using oligonucleotide pairs T4PS3/T4PAS1 and T4PS3/T4PAS2 respectively (Table 1). Construct −336/−71 was obtained after digestion of −541/−71 with EcoRV and XhoI and religation of the vector. Potential DNA-binding sites within the −600/+223 region of the TLR4 promoter were identified by computer analysis (using htpp://www.motif.genome.ad.jp). Mutations in AP-1 (activator protein-1), GATA, octamer, Etsd (distal E twenty-six, −292/−286) and Etsp (proximal Ets, −115/−109) sites were performed by PCR using the Quik Change™ site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) and the sense and antisense oligonucleotides AP-1 mt, GATA mt, octamer mt, Etsp mt and Etsd mt (Table 1). Tandem copies (three) of the Etsd site were synthesized (Table 1) and cloned in the pGL3 vector. All constructs were verified by sequencing. The expression constructs encoding for wild-type (amino acids 1–272), ΔDBD (Δ201−272; DBD stands for DNA-binding domain), ΔPEST (Δ118–160; PEST stands for proline-, glutamate-, serine- and threonine-rich), ΔTAD (Δ33–100; TAD stands for transactivation domain), ΔNP (Δ33–74) and ΔPN (Δ74–100) PU.1 and for GATA-1 [20] were a gift from Dr I. Skoultchi (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, NY, U.S.A.). The Oct-1 (octamer 1) expression construct [22] was kindly provided by Dr H. Singh (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Chicago, IL, U.S.A.). Plasmids encoding for Ets-1, Ets-2, Elf-1, ESE-1 and PEA3 transcription factors have been described previously [23]. All plasmids were purified using the EndoFree® Plasmid kit (Qiagen).

Transfection

Cells were plated at 30% confluency in six-well culture plates and transiently transfected on the following day using FuGENE™ 6 transfection reagent (Roche Diagnostics) and 2 μg of a luciferase reporter vector together with 0.05 μg of the Renilla pRL-TK vector (Promega). Co-transfection with PU.1, GATA-1 and Oct-1 expression constructs were performed as described in the Figure legends. Controls were co-transfected with the respective empty expression vectors. Fresh culture medium containing stimuli (see Cells and reagents subsection above) was added 24 h after transfection, and cells were cultured for an additional 24 h before harvesting. Luciferase and Renilla luciferase activities were measured using the Dual-Luciferase™ Reporter Assay System (Promega) and a TD-20/20 luminometer (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA, U.S.A.). Results were expressed as relative luciferase activity (ratio of luciferase activity to Renilla luciferase activity).

EMSA (electrophoretic mobility-shift assay) and supershift

Nuclear extracts were prepared and analysed by EMSA as described previously [24]. For supershift analyses, 2 μg of nuclear extracts were incubated for 1 h at 4 °C in 10 μl of supershift buffer [20 mM Hepes, 60 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM PMSF and 5% (v/v) glycerol] with 2 μg of poly(dI-dC)·poly(dI-dC) and 1 μl of supershift antiserum (sc-352 anti-PU.1, sc-111 anti-Ets-1, sc-351 anti-Ets-2, sc-355 anti-Elk-1, sc-109 anti-NF-κB p65; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, U.S.A.). Probes were added to the reaction mixture and incubation continued for 15 min at room temperature (22 °C). Samples were electrophoresed at 4 °C through 6% (w/v) non-denaturing polyacrylamide gels and the gels were exposed to X-ray films for autoradiography. Activity values of Ets-1, Ets-2 and Elk-1 antisera were confirmed in supershift experiments performed using the Ets and Elk oligonucleotides as described in Table 1 (results not shown).

RESULTS

Expression of TLR4 by macrophages

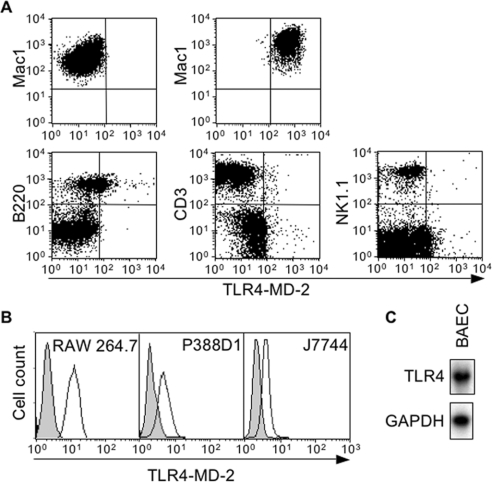

TLR4 expression of mouse peritoneal macrophages and splenocytes was analysed by flow cytometry using MTS510 mAb that recognizes the TLR4–MD-2 complex [19]. Splenocytes were counterstained with antibodies specific for B, T and NK (natural killer) cell antigens. As shown in Figure 1(A), a strong staining was observed using peritoneal macrophages, whereas B cells were weakly stained with MTS510 mAb. Of note, splenic T cells or NK cells were not stained with the anti-TLR4-MD-2 mAb. The specificity of the staining was confirmed by showing that macrophages from TLR4−/− mice were not labelled with the anti-TLR4-MD-2 mAb. Similarly to primary peritoneal macrophages, the commonly used RAW 264.7, J774 and P388D.1 mouse macrophage cell lines expressed high levels of TLR4 mRNA (results not shown) and TLR4-MD-2 (Figure 1B). Finally, TLR4 mRNA was detected in the bovine endothelial cell line BAEC and in NIH-3T3 mouse fibroblasts (Figures 1C and 6A).

Figure 1. TLR4 is expressed by macrophages.

(A) Flow cytometric analysis of TLR4-MD-2 expression by thioglycollate elicited peritoneal macrophages from TLR4−/− (upper left) and TLR4+/+ (upper right) mice and by spleen B (B220+), T (CD3+) and NK (NK1.1+) cells from a TLR4+/+ mouse. (B) TLR4-MD-2 expression by RAW 264.7, P388D1 and J774 mouse macrophage cells was determined by flow cytometry. The white and grey areas represent staining with anti-TLR4-MD-2 antibody and isotype-matched control antibody respectively. (C) Northern-blot analysis of TLR4 and GAPDH mRNA expression by BAEC.

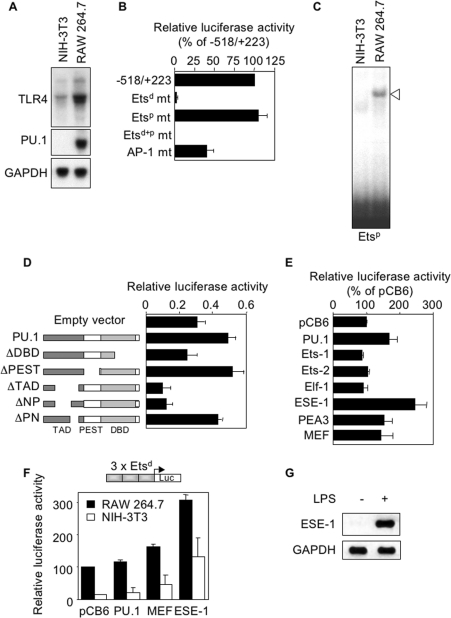

Figure 6. Expression of mouse TLR4 in the absence of PU.1.

(A) Northern-blot analysis of TLR4, PU.1 and GAPDH mRNA by NIH-3T3 and RAW 264.7 cells. (B) NIH-3T3 cells were transfected with −518/+223 wild-type and mutant (mt) TLR4 promoter constructs. Luciferase activity was expressed relative to the activity of the wild-type construct (100%). (C) Nuclear extracts from NIH-3T3 and RAW 264.7 cells were analysed by EMSA using a radiolabelled Etsp oligonucleotide. Specific complex is indicated with an open arrow. (D) Schematic representation of the TAD, PEST domain and DBD of PU.1 expression constructs (see the Materials and methods section), used to transfect NIH-3T3 cells together with −518/+223 TLR4 promoter. Results are expressed as means±S.D. for three independent determinations. (E) NIH-3T3 cells were transfected with −518/+223 TLR4 promoter construct together with expression constructs encoding for PU.1, Ets-1, Ets-2, Elf-1, ESE-1, PEA3 and MEF. Luciferase activity was expressed relative to that of cells transfected with the empty pCB6 vector (100%). Results are expressed as means±S.D. for two experiments. (F) NIH-3T3 and RAW 264.7 cells were transfected with a trimeric mouse TLR4 Etsd reporter construct together with expression constructs encoding for PU.1, MEF and ESE-1. Luciferase activity was expressed as in (E). Results are expressed as means±S.D. for three independent determinations. (G) Reverse transcriptase–PCR analysis of ESE-1 and GAPDH expression in resting (−) and LPS-stimulated (+) RAW 264.7 macrophages.

Analysis of truncated mouse TLR4 promoters

To localize DNA sequences controlling TLR4 promoter activity, deletion constructs of the mouse TLR4 promoter ranging from −2715 to +52 bp were cloned in a luciferase reporter vector and transiently transfected in RAW 264.7 cells (Figure 2A). Surprisingly, promoter activity increased four times after deletion of a 182 bp fragment from the −518 promoter, arguing for the presence of a negative regulatory element in the −518 to −336 bp promoter region. Positive regulatory elements were further localized in regions spanning from −336 to −271 bp and from −144 to −102 bp. The −518 bp promoter was then tested for basal activity in several cell lines. Strong promoter activity was detected in all macrophage cell lines (RAW 264.7, J774 and P388 D1) and in BAEC cells. Lower activity was detected in NIH-3T3 cells (Figure 2B). To make sure that these results were not influenced by differences in post-transcriptional regulation of luciferase expression in the various cells lines, we compared the expressions of SV40 promoter-driven Photinus pyralis luciferase and Renilla luciferase in RAW 264.7, J774 and P388 D1, NIH-3T3 and BAEC cells. On an average, ratios of P. pyralis luciferase over Renilla luciferase activities were five times higher in NIH-3T3 when compared with RAW 264.7, J774 and P388 D1 and BAEC cells (results not shown), indicating that the observed activity of the TLR4 promoter in NIH-3T3 cells was overestimated rather than underestimated.

Figure 2. Mouse TLR4 promoter activity and putative DNA-binding sites for transcription factors.

(A) Activity of mouse TLR4 promoter deletion constructs cloned into a luciferase reporter plasmid (pGL3) and transfected into RAW 264.7 macrophages. Cells were co-transfected with the Renilla pRL-TK vector. Results are expressed as the ratio of luciferase activity to Renilla luciferase activity. Results are expressed as means±S.D. for three independent determinations. (B) Activity of −518/+223 mouse TLR4 promoter (■) and empty pGL3 (□) in RAW 264.7, J774 and P388 D1 macrophages, NIH-3T3 fibroblasts and BAEC. Results are expressed as means±S.D. for three independent determinations. (C) Mouse Tlr4 5′-flanking sequence and potential DNA-binding sites for transcription factors. The ATG start codon is underlined twice (see text for explanations).

Sequence analysis of the proximal 500 bp of mouse TLR4 promoter revealed that it contained putative DNA-binding sites for several transcription factors but contained no TATA box (Figure 2C). Most notably, TLR4 promoter contained five core-TTCC-sequences that bind transcription factors of the Ets family. Two Ets sites at −292 bp (Etsd) and at −115 bp (Etsp) and an AP-1 site at −140 bp were identified in regions sustaining TLR4 promoter activity. A GATA-like motif (at position −342 bp) was detected in a region shown to repress TLR4 promoter activity (Figure 2A). Finally, a DNA-binding site for the octamer transcription factor and a composite IRF (IFN regulatory factor)/Ets motif were identified immediately downstream of the transcriptional start site.

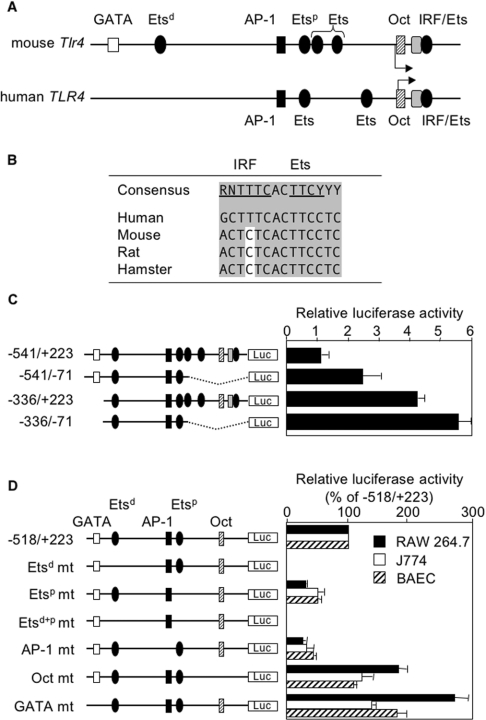

Comparison of the sequence of mouse and human proximal promoters (region encompassing −400 to +100 bp) revealed a high degree of conservation (Figure 3A). Maximal promoter activity in human macrophages was sustained by a short region ranging from −75 to +190 bp. This region included a conserved IRF/Ets composite site (+13/+27, Figure 2C and Figure 3B), which was reported to be essential for promoter activity. It also contained an octamer site that slightly repressed promoter activity in human macrophages [25]. To evaluate the role played by the homologous region of the mouse TLR4 promoter, −541 and −336 promoters truncated in the 3′-end at position −71 were generated by PCR and their activities were tested in RAW 264.7 macrophages. As shown in Figure 3(C), activities of the two truncated promoters were increased compared with that of the −541 and −336 wildtype promoters. Taken together, with the lack of activity of the −102 promoter (Figure 2A), these results suggest that the IRF/Ets composite site is not required for Tlr4 gene activation in mouse macrophages. Yet, similarly to the human TLR4 promoter, the proximal −71 bp of mouse TLR4 promoter contains an element(s) that represses transcriptional activity.

Figure 3. Identification of DNA-binding sites regulating mouse TLR4 promoter activity in macrophages and endothelial cells.

(A) Comparison of putative transcription regulatory sites of the mouse and human TLR4 5′-flanking region. (B) Sequence alignment of the conserved IRF/Ets composite DNA-binding site in the human (GenBank® accession no. AF177765), mouse (AF177767), rat (NM_019178) and hamster (AF153676) TLR4 promoters. Nucleotides matching those of the consensus sequence are highlighted in grey. (C) Activity of 5′- and 3′-truncated mouse TLR4 promoter constructs in RAW 264.7 macrophages. (D) Site-directed mutations of Etsd, Etsp, Etsd+p, AP-1, octamer and GATA sites were introduced in −518/+223 TLR4 promoter. RAW 264.7 cells were transfected with −518/+223 wild-type and mutant (mt) promoter constructs. Luciferase activity was expressed relative to the activity of the wild-type construct (100%). Results are expressed as means±S.D. for one representative experiment performed in triplicate.

Identification of positive and negative regulatory regions of the mouse TLR4 promoter using site-directed mutagenesis

To investigate the functional significance of the Etsd and Etsp, AP-1, GATA-like and octamer sites, we performed site-directed mutagenesis of these DNA-binding sites within the −518 promoter. Wild-type and mutant constructs were tested in RAW 264.7, J774 and BAEC cell lines (Figure 3D). In all three cell lines, disruption of the Etsd site completely abolished promoter activity, whereas the disruption of the Etsp and AP-1 sites decreased promoter activity by 50 and 75% respectively. In contrast, mutation of the octamer and GATA-like binding sites increased promoter activity, especially in RAW 264.7 macrophages (Figure 3D). Therefore the Ets and AP-1 DNA-binding sites and the GATA-like and octamer DNA-binding sites act as positive and negative regulators respectively of the mouse TLR4 promoter activity.

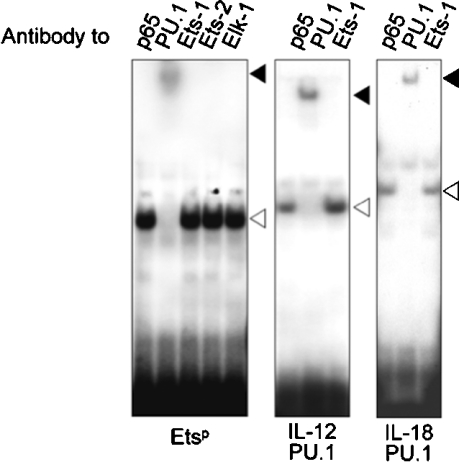

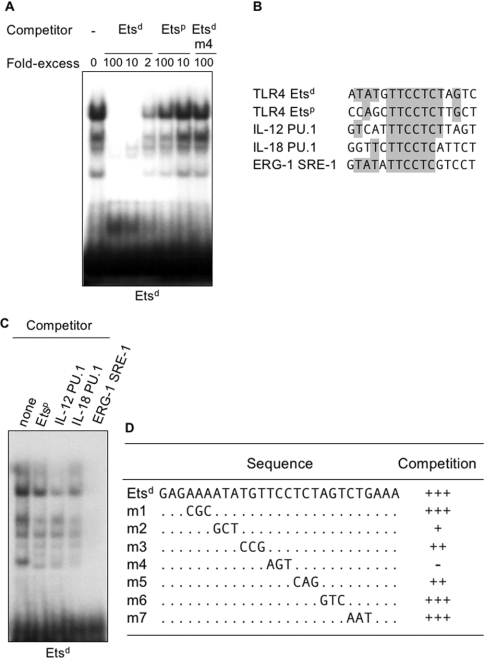

PU.1 binds to the Etsd but not to the Etsp site of mouse TLR4 promoter

To identify the nuclear proteins involved in Tlr4 gene activation, we performed EMSA with nuclear extracts from unstimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. Using a double-stranded oligonucleotide corresponding to the Etsp DNA-binding site, a specific retarded complex was revealed that migrated similarly to a complex obtained on incubation of the same protein extracts with an oligonucleotide specific for the PU.1 DNA-binding site of the IL (interleukin)-12 and -18 promoters. The specificity of Etsp DNA–protein complex was demonstrated by showing that it was dose dependently competed by adding unlabelled Etsp oligonucleotide to the reaction mixture, whereas the addition of a mutant oligonucleotide had no effect (results not shown). The identity of the protein involved in the complex formation was then investigated by preincubating EMSA reaction mixtures with antibodies directed against members of the Ets family (PU.1, Ets-1, Ets-2 and Elk-1) or control antibodies directed against p65. The Etsp complex and the IL-12 PU.1 and IL-18 PU.1 complexes were supershifted only when using anti-PU.1 antibodies (Figure 4). Therefore PU.1 transcription factor bound the Etsp site implicated in mouse TLR4 promoter basal activity.

Figure 4. PU.1 binds to the Etsp site of mouse TLR4 promoter.

Nuclear extracts from RAW 264.7 macrophages were preincubated with antibodies directed against p65, PU.1, Ets-1, Ets-2 or Elk-1. TLR4 Etsp (left panel), IL-12 PU.1 (middle panel) and IL-18 PU.1 (right panel) radiolabelled oligonucleotides were added to the reactions. Specific complexes are indicated with an open arrowhead. Supershifts are indicated with a closed arrowhead. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

We then performed EMSA to determine the identity of the protein binding to the TLR4 Etsd site. Using nuclear extracts from RAW 264.7 macrophages, we identified four specific retarded complexes by competition analysis (Figure 5A). It may be noted that excess of unlabelled TLR4 Etsp, IL-12 PU.1 and IL-18 PU.1 oligonucleotides weakly inhibited DNA–protein complex formation, suggesting a different protein binding preference of the Etsd site (Figures 5B and 5C). Preincubation of binding reactions with anti-PU.1 antibodies before adding labelled Etsd oligonucleotide also did not cause a supershift. Etsd complex was competed using an excess of an unlabelled oligonucleotide specific for the SRE (serum response element) site from the human ERG-1 promoter (SRE-1, Figures 5B and 5C), for which a weak supershift was observed using antibodies against Elk-1 [26]. However, antibodies against Elk-1, Ets-1 and Ets-2 did not cause a supershift of Etsd complexes (results not shown).

Figure 5. PU.1 does not bind to the Etsd site of mouse TLR4 promoter.

(A) Nuclear extracts from RAW 264.7 macrophages were incubated with a radiolabelled Etsd oligonucleotide. Competition analyses were performed with unlabelled Etsd, Etsp and Etsd m4 oligonucleotides, as indicated. (B) Comparison of the sequence of the Ets sites of mouse TLR4 (Etsd and Etsp), IL-12 (PU.1), IL-18 (PU.1) and ERG-1 (SRE-1) promoters. Nucleotides matching the Etsd sequence are highlighted in grey. (C) Competition analyses were performed using nuclear extracts from RAW 264.7 cells incubated with radiolabelled Etsd oligonucleotide and 100 times more of the indicated unlabelled oligonucleotides. (D) Summary of competition studies performed with wild-type and mutant (m1–m7) Etsd oligonucleotides. For each mutant, only the mutated 3 bp is shown. Competition effectiveness was graded from − (no competition) to +++ (strong competition similar to that obtained with wild-type Etsd oligonucleotide).

To determine which nucleotides were required for a DNA–protein complex formation at the Etsd site, a series of sequential 3 bp mutations were introduced into an Etsd oligonucleotide (m1–m7, Table 1) and tested for competition with labelled Etsd oligonucleotide. As summarized in Figure 5(D), m4 in which three nucleotides in the core -TTCC- box had been disrupted did not inhibit complex formation. Mutants m3 and m5 only partially inhibited complex formation, whereas the mutants m1, m6 and m7 fully inhibited complex formation. Finally, mutant m2 showed a markedly reduced inhibitory capacity. Interestingly, m2 was mutated in a region of the Etsd oligonucleotide (ATA) that was more conserved in SRE-1 oligonucleotide (GTA) when compared with the Etsp (CCA), IL-12 PU.1 (GTC) and IL-18 PU.1 (GGT) oligonucleotides (Figure 5B). Taken together, these results indicated that nucleotides comprising the core -TTCC- box are critical for complex formation at the Etsd site and that neighbouring nucleotides appear to influence the composition of the protein-binding complex.

TLR4 is expressed in the absence of PU.1

Mutational and supershift analyses suggested that the PU.1 transcription factor was required to mediate full activation of the TLR4 promoter. Yet, PU.1 was presumably not essential for transcription activation, as deduced from the observation that disruption of the Etsp site did not abolish TLR4 promoter activity. To verify this assumption, we used NIH-3T3 mouse fibroblasts deficient in PU.1 but expressing TLR4 mRNA (Figure 6A). In NIH-3T3 fibroblasts, −518 promoter was constitutively active although much less than in RAW 264.7 macrophages (Figure 2B). Promoter activity was either completely or partially abolished by mutation of Etsd and AP-1 sites respectively (Figure 6B). In contrast, mutation of Etsp site did not alter promoter activity, an observation congruous with the absence of detectable protein binding to the Etsp site using nuclear extracts from NIH-3T3 cells (Figure 6C). Overexpression of PU.1 or a PU.1 mutant, lacking the PEST domain in NIH-3T3 cells, increased TLR4 promoter activity (1.7-fold, Figure 6D), however to levels that remained lower than those measured in RAW 264.7 macrophages (results not shown). The increased activity was lost when cells were transfected with a PU.1 expression construct lacking the DBD. Finally, TLR4 promoter activity was inhibited in cells overexpressing PU.1 mutants with partial deletions of the N-terminal TAD. Therefore the DBD and the ΔTAD of PU.1 were required for optimal mouse TLR4 promoter transcriptional activity.

In an attempt to identify which transcription factor may be implicated in the regulation of TLR4 promoter activity, NIH-3T3 cells were transfected with vectors encoding the members (Ets-1, Ets-2, Elf-1, ESE-1, PEA3 and MEF; MEF stands for myeloid Elf-1-like factor) of the Ets family. In addition to PU.1, TLR4 promoter activity was weakly increased (1.5-fold) by PEA3 and MEF, whereas ESE-1 more markedly increased promoter activity (2.5-fold, Figure 6E). Moreover, ESE-1 strongly increased the luciferase activity of NIH-3T3 and RAW 264.7 cells, transfected with a trimeric Etsd reporter construct (Figure 6F). Yet, ESE-1 mRNA was not detected in resting RAW 264.7 macrophages (Figure 6G).

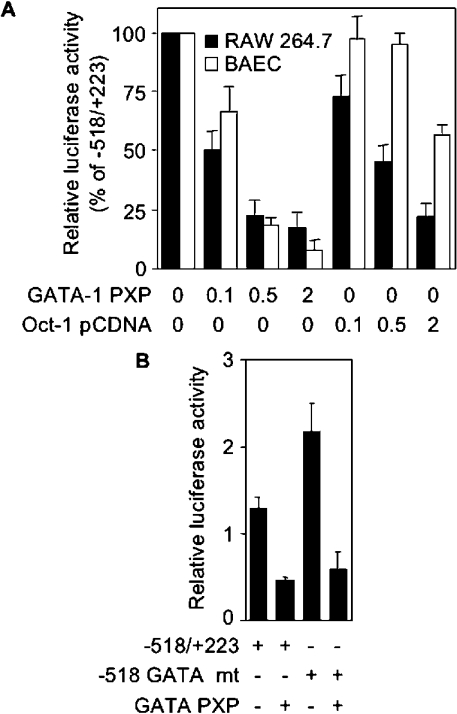

Protein binding at the GATA-like and octamer sites of mouse TLR4 promoter

Basal activity of mouse TLR4 promoter in RAW 264.7 macrophages was observed to be repressed through a GATA-like and an octamer DNA-binding sites. We therefore performed EMSA to detect protein binding to these sites. Using nuclear proteins from RAW 264.7 cells, two GATA complexes and a weak octamer complex were identified. All of these complexes were specific, as they were inhibited by unlabelled specific oligonucleotides and by oligonucleotides containing reference sites for GATA-1 and Oct-1, but not with TLR4 GATA-like and octamer mutant oligonucleotides respectively (results not shown). To confirm that proteins interacting with GATA-like and octamer motifs repressed TLR4 promoter activity, luciferase activity was measured in RAW 264.7 macrophages and BAEC cells that were co-transfected with −518 promoter and increasing concentrations of GATA-1 and Oct-1 expressing vectors. As shown in Figure 7(A), both GATA-1 and, to a lesser extent, Oct-1 inhibited in a dose-dependent manner, the −518 promoter activity. Importantly, GATA-1 inhibited luciferase activity driven by wild-type and mutant GATA −518 promoter (Figure 7B).

Figure 7. Inhibition of mouse TLR4 promoter activity by GATA-1 and Oct-1.

(A) Activity of −518/+223 mouse TLR4 promoter construct in RAW 264.7 (■) and BAEC (□) cells co-transfected with increasing amounts (0.1, 0.5 and 2 μg) of GATA-1 (GATA-1 PXP) and Oct-1 (Oct-1 pcDNA) expression plasmids. Luciferase activity was expressed relative to that of cells transfected with the empty vector (100%). Results are expressed as means±S.D. for one representative experiment performed in triplicate. (B) RAW 264.7 macrophages were transfected with wild-type −518/+223 or mutant GATA −518/+223 (GATA mt) mouse TLR4 promoter construct together with (+) or without (−) 1 μg of a GATA-1 expression plasmid (GATA-1 PXP). Results are expressed as means±S.D. for two independent experiments.

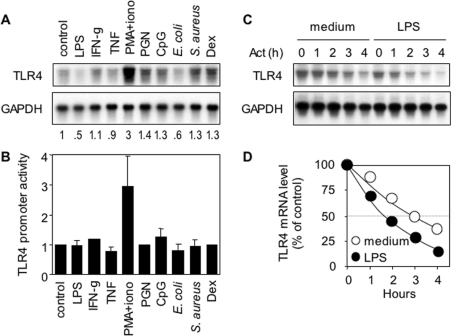

Transcriptional and post-transcriptional control of Tlr4 gene expression in activated macrophages

We next examined whether Tlr4 gene expression was modulated after exposure of macrophages to pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory stimuli. TLR4 mRNA levels and promoter activity were measured in RAW 264.7 cells stimulated with microbial products (LPS, PGN, CpG oligonucleotide, heat-killed E. coli and S. aureus), cytokines (IFN-γ and TNF), mitogen (PMA plus ionomycin) or Dex. Compared with baseline, TLR4 mRNA levels were decreased after exposure to LPS and E. coli, whereas it was increased after exposure to PMA plus ionomycin or PGN. The impact of all the other stimuli, including Dex, was more subtle (10–30% variation of TLR4 mRNA expression; Figure 8A). Similarly, TLR4 promoter activity was markedly increased in cells stimulated with PMA and ionomycin (Figure 8B). However, it may be noted that LPS or E. coli did not inhibit TLR4 promoter activity, suggesting that both stimuli modulate TLR4 mRNA expression by a post-transcriptional mechanism. Consistent with this hypothesis, LPS was found to lower the TLR4 mRNA half-life by almost 50% compared with that of unstimulated cells (Figures 8C and 8D).

Figure 8. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional control of TLR4 mRNA expression in RAW 264.7 macrophages.

(A) Northern-blot analysis of TLR4 and GAPDH mRNA expression by RAW 264.7 macrophages stimulated for 4 h with pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory stimuli (see the Materials and methods section). (B) TLR4 promoter (−518/+223) activity in RAW 264.7 cells cultured for 18 h with the indicated stimuli. Results are expressed as means±S.D. for 3–6 independent experiments performed in triplicates. (C) Northern-blot analysis of TLR4 and GAPDH mRNA expression by RAW 264.7 cells cultured for 1 h with or without LPS and then incubated with actinomycin D (Act) for an additional 0, 1, 2, 3 or 4 h. (D) Time course of TLR4 mRNA decay in unstimulated (○) or LPS-stimulated (●) RAW 264.7 cells. TLR4 levels were normalized for GAPDH levels and expressed as a percentage of TLR4 levels measured at zero time (i.e. before the addition of actinomycin D).

DISCUSSION

Analyses of TLR4 expression by mouse immune cells have revealed high TLR4 promoter activity and protein expression in the macrophage. Transcription of the mouse Tlr4 gene was found to be under the control of regulatory elements, including Ets, AP-1, GATA-like and octamer DNA-binding sites, all located within 350 bp of the transcription start site.

The Ets family of transcription factors comprises over 35 members, among which PU.1 has been shown to play an important role in the differentiation of myeloid and lymphoid cells. PU.1 was found to be implicated in the regulation of the expression of numerous myeloid- and B cell-specific genes, such as those encoding for integrin subunits, IgG chains, growth factors (macrophage, granulocyte and granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factors), cytokines (IL-1, -4, -12 and -18) and receptors for complement, IgGs and cytokines (reviewed in [27,28]). Consistent with its important role in myeloid cells gene expression, PU.1 was observed to sustain basal TLR4 promoter activity in mouse macrophages by binding to a proximal conserved Ets sequence located near the transcription start site. High level of expression of PU.1 promotes macrophage differentiation, whereas low level of expression facilitates B-cell development [29]. Differences in PU.1 cell content may therefore account for higher degree of TLR4 expression in macrophages compared with that in B cells. In agreement with an important role for PU.1 in the macrophage, mutation of the Etsp-binding site decreased TLR4 promoter activity by half. In contrast, transfection of PU.1-deficient NIH-3T3 fibroblasts with a PU.1 expression plasmid increased TLR4 promoter activity. It may be noted that TLR4 promoter activity was inhibited by transfecting NIH-3T3 cells with expression plasmids encoding for PU.1 mutants lacking the TAD but retaining a functional DBD (constructs ΔTAD and ΔNP, Figure 6D). Presumably, overexpressed mutant proteins competed with endogenous transcription factors for binding to Ets sites.

A second, more distal, Ets DNA-binding site was identified as an indispensable regulatory element for Tlr4 expression, as mutation of the Etsd site completely abolished promoter activity. By EMSA, four specific retarded DNA–protein complexes were detected at the Etsd site. However, none of these complexes were supershifted using antibodies against PU.1, Ets-1, Ets-2 and Elk-1 transcription factors. In an attempt to determine which transcription factors may bind to the Etsd site, NIH-3T3 and RAW 264.7 cells were transfected with expression constructs encoding for various Ets factors. Of all the constructs tested, the ESE-1 construct was the only one found to increase both TLR4 promoter activity and luciferase activity driven by a trimeric TLR4 Etsd site, indicating that ESE-1 is capable of binding to the Etsd site. However, ESE-1 was not expressed in resting macrophages, in agreement with the fact that ESE-1 belongs to a newly identified subclass of Ets transcription factors whose basal expression was reported to be restricted to epithelial cells [30–32]. It is still possible that an as yet uncharacterized member of the ESE family of transcription factors binds to the Etsd site in macrophages. As the TLR4 promoter was also active in endothelial cells and fibroblasts, it appears that the transcription factor(s) binding to the Etsd site could have a more ubiquitous cell distribution than myeloid and lymphoid cells only. Work is currently in progress to identify the nature of the protein(s) binding to the Etsd site.

To determine which nucleotides are required for protein binding at the Etsd DNA-binding site, competition analyses were conducted with sequential mutants of the Etsd oligonucleotides. Nucleotides adjacent to (i.e. positioned at −4/−6) the 5′-end of the -TTCC- core sequence were found to be critical for binding in competition experiments. These nucleotides may either affect the binding of an Ets transcription factor to the -TTCC- core sequence or else mediate the binding of a transcription factor next to the Ets site. The latter hypothesis would be in line with a rapidly growing number of studies suggesting that Ets transcription factors may physically interact with other transcription factors to enhance transcriptional activity. A well-documented example of this dual components model is the co-operative interaction between PU.1 and IRF for binding to composite Ets/IRF sites that promote the activation of lymphoid and myeloid genes [25,33–37]. However, apart from the Ets site, no IRF or other consensus DNA-binding site was detected within the immediate proximity of the Etsd site.

The transcription factor AP-1 was also found to regulate positively Tlr4 gene expression in mouse cells. Using nuclear extracts from resting cells, a specific DNA–protein complex was detected at the AP-1 site, confirming that the AP-1 site was implicated in transcription (results not shown). Moreover, mutation of a conserved DNA-binding site for AP-1 decreased promoter activity in RAW 264.7 and J774 macrophages, BAEC and NIH-3T3 fibroblasts. Taken together, these results suggest that basal activity of mouse TLR4 promoter is supported by at least three elements: an indispensable Etsd site, an AP-1 site and an Etsp site.

A GATA-like site and, to a lesser extent, a conserved octamer site were identified as repressors of TLR4 promoter activity. Mutation of the GATA-like site and overexpression of GATA-1 transcription factor have marked effects on mouse TLR4 promoter activity. GATA-1 was recently reported to inhibit gene transcription through two different mechanisms of action, implicating either a direct binding to DNA or a protein–protein interaction between GATA-1 and PU.1 that inhibits PU.1 activity [20,38]. However, GATA-1 quite probably did not bind to the GATA-like site, as GATA-1 expression is repressed during macrophage differentiation [28]. A possible candidate for binding the TLR4 GATA-like site is GAP-12, a nuclear factor present in resting RAW 264.7 macrophages [39]. GAP-12 has been shown to inhibit IL-12 p40 promoter activity on binding to an element called GA-12. Binding of GAP-12 to GA-12 required specific nucleotides in the immediate vicinity (−5/−4 and +3/+4) of the GATA core sequence, which were found in the mouse TLR4 promoter. Unfortunately, GAP-12 has not been cloned and there are no anti-GAP-12 antibodies available. Thus we could not verify whether GAP-12 binds the TLR4 GATA-like site. In addition to mouse TLR4 and IL-12 p40 promoters, numerous myeloid promoters contain GATA-like sequences, suggesting that GATA-related transcription factors may repress the expression of several myeloid-specific genes. Functional promoter studies of the mouse IL-18 [40], mannose receptor [41] and Tlr2 [42] and human CD33 [43] and TLR4 [25] genes showed increased transcriptional activity on deletion of GATA-binding sites. However, these studies focused on positive regulatory elements and did not characterize the elements involved in transcriptional repression of these genes. In agreement with the second mode of action, which does not require binding of GATA-1 to DNA, transfection of RAW 264.7 macrophages with a GATA-1 expression construct inhibited luciferase activity driven by a TLR4 promoter construct with a mutated GATA-like binding site. In addition to the GATA-like site, mouse TLR4 promoter contained a consensus octamer element that repressed transcriptional activity, albeit weakly. Mutation of a homologous octamer element within the human TLR4 promoter slightly increased basal transcription. The marginal effect of the mutated octamer site reflected the fact that human and mouse octamer sites were weak binding sites for octamer transcription factors (results not shown and [25]).

The mouse and human TLR4 genes are highly conserved [44], yet they exhibit noteworthy dissimilarities with respect to transcriptional regulation, which may account for the differences that have been observed between mouse and human TLR4 in terms of tissue expression and modulation of expression in response to infectious and inflammatory stimuli. For example, much higher levels of TLR4 mRNA have been detected in mouse than in human heart and liver [6,45]. Stimulation of human monocytes with LPS, IL-1β and TNF factor increased TLR4 mRNA expression [46,47], whereas it either decreased or did not affect that of mouse macrophages [48,49]. Consistent with these previous observations, we also found that TLR4 expression was strongly reduced after exposure of mouse macrophages to LPS and Gramnegative bacteria (E. coli). Interestingly, LPS did not affect promoter activity, but markedly increased the turnover of TLR4 transcripts. This post-transcriptional mode of regulation is reminiscent of that observed in LPS-stimulated rat alveolar macrophages [50]. In contrast, PMA plus ionomycin significantly increased TLR4 mRNA levels and promoter activity, suggesting a role for protein kinase C and calcium signalling in Tlr4 gene transcription.

The activity of the human TLR4 promoter was regulated by transcription factors acting on elements located in the immediate vicinity of the transcription start site, whereas the important regulatory elements of the mouse Tlr4 gene act more distally. Most notably, full basal activity of the human TLR4 promoter was dependent on binding of IRF-8 and PU.1 to a composite IRF/Ets motif located at position +13 [25], whereas the homologous IRF/Ets motif did not play the same crucial role for the mouse promoter activity. Sequence analysis revealed the existence of a perfect match between human TLR4 IRF and the consensus IRF sequence, which was shown recently to be essential for the binding of the IRF transcription factor to the human CD68 promoter [37]. In contrast, mouse, rat and hamster TLR4 IRF elements diverged by one nucleotide (Figure 3B). As no other IRF-binding site was identified in the mouse TLR4 promoter, IRF-8 does not appear to play an important role in the transcriptional regulation of mouse Tlr4. Consistent with this argument, IRF-8-deficient mice exhibit normal responses to LPS stimulation [51]. Thus, in contrast with the situation of human TLR4, the IRF/Ets element is not essential for mouse Tlr4 regulation, quite probably due to impaired binding of IRF protein to DNA. Other differences between the mouse and human TLR4 promoters are the absence of Etsd and GATA-like DNA-binding sites in the human promoter (Figure 3A).

In conclusion, despite high sequence homology, mouse and human TLR4 exhibit significant differences with respect to the elements implicated in the regulation of gene expression. These observations may explain, at least in part, some of the known dissimilarities of TLR4 expression and innate immune responses to endotoxin and Gram-negative bacteria in the mouse and humans, and remind us of the caution necessary when extrapolating the results of experimental mouse models of sepsis to humans.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr I. Skoultchi and Dr H. Singh for providing expression plasmids, Dr A. Abderrahmani for providing the SV40-pGL3 vector and Dr S. Akira for the gift of TLR4 knockout mice. This work was supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (3100-066972.01), the Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation, the Leenaards Foundation and the Santos-Suarez Foundation for Medical Research. T.C. is the recipient of a career award from the Leenaards Foundation.

References

- 1.Hoffmann J. A., Kafatos F. C., Janeway C. A., Ezekowitz R. A. Phylogenetic perspectives in innate immunity. Science. 1999;284:1313–1318. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janeway C. A., Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ulevitch R. J., Tobias P. S. Recognition of Gram-negative bacteria and endotoxin by the innate immune system. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1999;11:19–22. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)80004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffmann J. A., Reichhart J. M. Drosophila innate immunity: an evolutionary perspective. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:121–126. doi: 10.1038/ni0202-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poltorak A., He X., Smirnova I., Liu M. Y., Van Huffel C., Du X., Birdwell D., Alejos E., Silva M., Galanos C., et al. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science. 1998;282:2085–2088. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qureshi S. T., Lariviere L., Leveque G., Clermont S., Moore K. J., Gros P., Malo D. Endotoxin-tolerant mice have mutations in Toll-like receptor 4 (Tlr4) J. Exp. Med. 1999;189:615–625. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.4.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoshino K., Takeuchi O., Kawai T., Sanjo H., Ogawa T., Takeda Y., Takeda K., Akira S. Cutting edge: Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-deficient mice are hyporesponsive to lipopolysaccharide: evidence for TLR4 as the Lps gene product. J. Immunol. 1999;162:3749–3752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medzhitov R., Preston-Hurlburt P., Janeway C. A. A human homologue of the Drosophila Toll protein signals activation of adaptive immunity. Nature (London) 1997;388:394–397. doi: 10.1038/41131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Brien A. D., Rosenstreich D. L., Scher I., Campbell G. H., MacDermott R. P., Formal S. B. Genetic control of susceptibility to Salmonella typhimurium in mice: role of the LPS gene. J. Immunol. 1980;124:20–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimazu R., Akashi S., Ogata H., Nagai Y., Fukudome K., Miyake K., Kimoto M. MD-2, a molecule that confers lipopolysaccharide responsiveness on Toll-like receptor 4. J. Exp. Med. 1999;189:1777–1782. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.11.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagai Y., Akashi S., Nagafuku M., Ogata M., Iwakura Y., Akira S., Kitamura T., Kosugi A., Kimoto M., Miyake K. Essential role of MD-2 in LPS responsiveness and TLR4 distribution. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:667–672. doi: 10.1038/ni809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takeda K., Kaisho T., Akira S. Toll-like receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2003;21:335–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang D., Zhang G., Hayden M. S., Greenblatt M. B., Bussey C., Flavell R. A., Ghosh S. A toll-like receptor that prevents infection by uropathogenic bacteria. Science. 2004;303:1522–1526. doi: 10.1126/science.1094351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diebold S. S., Kaisho T., Hemmi H., Akira S., Reis E., Sousa C. Innate antiviral responses by means of TLR7-mediated recognition of single-stranded RNA. Science. 2004;303:1529–1531. doi: 10.1126/science.1093616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heil F., Hemmi H., Hochrein H., Ampenberger F., Kirschning C., Akira S., Lipford G., Wagner H., Bauer S. Species-specific recognition of single-stranded RNA via toll-like receptor 7 and 8. Science. 2004;303:1526–1529. doi: 10.1126/science.1093620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agnese D. M., Calvano J. E., Hahm S. J., Coyle S. M., Corbett S. A., Calvano S. E., Lowry S. F. Human toll-like receptor 4 mutations but not CD14 polymorphisms are associated with an increased risk of gram-negative infections. J. Infect. Dis. 2002;186:1522–1525. doi: 10.1086/344893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hawn T. R., Verbon A., Lettinga K. D., Zhao L. P., Li S. S., Laws R. J., Skerrett S. J., Beutler B., Schroeder L., Nachman A., et al. A common dominant TLR5 stop codon polymorphism abolishes flagellin signaling and is associated with susceptibility to legionnaires' disease. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:1563–1572. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smirnova I., Mann N., Dols A., Derkx H. H., Hibberd M. L., Levin M., Beutler B. Assay of locus-specific genetic load implicates rare Toll-like receptor 4 mutations in meningococcal susceptibility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:6075–6080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1031605100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akashi S., Shimazu R., Ogata H., Nagai Y., Takeda K., Kimoto M., Miyake K. Cutting edge: cell surface expression and lipopolysaccharide signaling via the toll-like receptor 4-MD-2 complex on mouse peritoneal macrophages. J. Immunol. 2000;164:3471–3475. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.7.3471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rekhtman N., Radparvar F., Evans T., Skoultchi A. I. Direct interaction of hematopoietic transcription factors PU.1 and GATA-1: functional antagonism in erythroid cells. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1398–1411. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.11.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roger T., David J., Glauser M. P., Calandra T. MIF regulates innate immune responses through modulation of Toll-like receptor 4. Nature (London) 2001;414:920–924. doi: 10.1038/414920a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shah P. C., Bertolino E., Singh H. Using altered specificity Oct-1 and Oct-2 mutants to analyze the regulation of immunoglobulin gene transcription. EMBO J. 1997;16:7105–7117. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.7105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kai H., Hisatsune A., Chihara T., Uto A., Kokusho A., Miyata T., Basbaum C. Myeloid ELF-1-like factor up-regulates lysozyme transcription in epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:20098–20102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roger T., Out T., Mukaida N., Matsushima K., Jansen H., Lutter R. Enhanced AP-1 and NF-kappaB activities and stability of interleukin 8 (IL-8) transcripts are implicated in IL-8 mRNA superinduction in lung epithelial H292 cells. Biochem. J. 1998;330:429–435. doi: 10.1042/bj3300429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rehli M., Poltorak A., Schwarzfischer L., Krause S. W., Andreesen R., Beutler B. PU.1 and interferon consensus sequence-binding protein regulate the myeloid expression of the human Toll-like receptor 4 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:9773–9781. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu Z., Dziarski R., Wang Q., Swartz K., Sakamoto K. M., Gupta D. Bacterial peptidoglycan-induced tnf-alpha transcription is mediated through the transcription factors Egr-1, Elk-1, and NF-kappaB. J. Immunol. 2001;167:6975–6982. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.12.6975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharrocks A. D. The ETS-domain transcription factor family. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;2:827–837. doi: 10.1038/35099076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tenen D. G., Hromas R., Licht J. D., Zhang D. E. Transcription factors, normal myeloid development, and leukemia. Blood. 1997;90:489–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeKoter R. P., Singh H. Regulation of B lymphocyte and macrophage development by graded expression of PU.1. Science. 2000;288:1439–1441. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oettgen P., Alani R. M., Barcinski M. A., Brown L., Akbarali Y., Boltax J., Kunsch C., Munger K., Libermann T. A. Isolation and characterization of a novel epithelium-specific transcription factor, ESE-1, a member of the ets family. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997;17:4419–4433. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oettgen P., Kas K., Dube A., Gu X., Grall F., Thamrongsak U., Akbarali Y., Finger E., Boltax J., Endress G., et al. Characterization of ESE-2, a novel ESE-1-related Ets transcription factor that is restricted to glandular epithelium and differentiated keratinocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:29439–29452. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.41.29439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kas K., Finger E., Grall F., Gu X., Akbarali Y., Boltax J., Weiss A., Oettgen P., Kapeller R., Libermann T. A. ESE-3, a novel member of an epithelium-specific ets transcription factor subfamily, demonstrates different target gene specificity from ESE-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:2986–2998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eklund E. A., Jalava A., Kakar R. PU.1, interferon regulatory factor 1, and interferon consensus sequence-binding protein cooperate to increase gp91(phox) expression. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:13957–13965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Himmelmann A., Riva A., Wilson G. L., Lucas B. P., Thevenin C., Kehrl J. H. PU.1/Pip and basic helix loop helix zipper transcription factors interact with binding sites in the CD20 promoter to help confer lineage- and stage-specific expression of CD20 in B lymphocytes. Blood. 1997;90:3984–3995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu X., Prabhu A., Van Ness B. Developmental regulation of the kappa locus involves both positive and negative sequence elements in the 3′ enhancer that affect synergy with the intron enhancer. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:3285–3293. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marecki S., Riendeau C. J., Liang M. D., Fenton M. J. PU.1 and multiple IFN regulatory factor proteins synergize to mediate transcriptional activation of the human IL-1 beta gene. J. Immunol. 2001;166:6829–6838. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Reilly D., Quinn C. M., El Shanawany T., Gordon S., Greaves D. R. Multiple Ets factors and interferon regulatory factor-4 modulate CD68 expression in a cell type-specific manner. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:21909–21919. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212150200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nerlov C., Querfurth E., Kulessa H., Graf T. GATA-1 interacts with the myeloid PU.1 transcription factor and represses PU.1-dependent transcription. Blood. 2000;95:2543–2551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Becker C., Wirtz S., Ma X., Blessing M., Galle P. R., Neurath M. F. Regulation of IL-12 p40 promoter activity in primary human monocytes: roles of NF-kappaB, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta, and PU.1 and identification of a novel repressor element (GA-12) that responds to IL-4 and prostaglandin E(2) J. Immunol. 2001;167:2608–2618. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.5.2608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim Y. M., Kang H. S., Paik S. G., Pyun K. H., Anderson K. L., Torbett B. E., Choi I. Roles of IFN consensus sequence binding protein and PU.1 in regulating IL-18 gene expression. J. Immunol. 1999;163:2000–2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eichbaum Q., Heney D., Raveh D., Chung M., Davidson M., Epstein J., Ezekowitz R. A. Murine macrophage mannose receptor promoter is regulated by the transcription factors PU.1 and SP1. Blood. 1997;90:4135–4143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang T., Lafuse W. P., Zwilling B. S. NFkappaB and Sp1 elements are necessary for maximal transcription of toll-like receptor 2 induced by Mycobacterium avium. J. Immunol. 2001;167:6924–6932. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.12.6924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bodger M. P., Hart D. N. Molecular cloning and functional analysis of the CD33 promoter. Br. J. Haematol. 1998;102:986–995. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rehli M. Of mice and men: species variations of Toll-like receptor expression. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:375–378. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02259-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zarember K. A., Godowski P. J. Tissue expression of human Toll-like receptors and differential regulation of Toll-like receptor mRNAs in leukocytes in response to microbes, their products, and cytokines. J. Immunol. 2002;168:554–561. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.2.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bosisio D., Polentarutti N., Sironi M., Bernasconi S., Miyake K., Webb G. R., Martin M. U., Mantovani A., Muzio M. Stimulation of toll-like receptor 4 expression in human mononuclear phagocytes by interferon-gamma: a molecular basis for priming and synergism with bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Blood. 2002;99:3427–3431. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.9.3427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Visintin A., Mazzoni A., Spitzer J. H., Wyllie D. H., Dower S. K., Segal D. M. Regulation of Toll-like receptors in human monocytes and dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2001;166:249–255. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matsumura T., Ito A., Takii T., Hayashi H., Onozaki K. Endotoxin and cytokine regulation of toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR4 gene expression in murine liver and hepatocytes. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2000;20:915–921. doi: 10.1089/10799900050163299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nomura F., Akashi S., Sakao Y., Sato S., Kawai T., Matsumoto M., Nakanishi K., Kimoto M., Miyake K., Takeda K., et al. Cutting edge: endotoxin tolerance in mouse peritoneal macrophages correlates with down-regulation of surface toll-like receptor 4 expression. J. Immunol. 2000;164:3476–3479. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.7.3476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fan J., Kapus A., Marsden P. A., Li Y. H., Oreopoulos G., Marshall J. C., Frantz S., Kelly R. A., Medzhitov R., Rotstein O. D. Regulation of Toll-like receptor 4 expression in the lung following hemorrhagic shock and lipopolysaccharide. J. Immunol. 2002;168:5252–5259. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.5252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Giese N. A., Gabriele L., Doherty T. M., Klinman D. M., Tadesse-Heath L., Contursi C., Epstein S. L., Morse H. C., III Interferon (IFN) consensus sequence-binding protein, a transcription factor of the IFN regulatory factor family, regulates immune responses in vivo through control of interleukin 12 expression. J. Exp. Med. 1997;186:1535–1546. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.9.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]