Abstract

The lysine-specific histone demethylase 1 A (LSD1) is involved in antitumor immunity; however, its role in shaping CD8 + T cell (CTL) differentiation and function remains largely unexplored. Here, we show that pharmacological inhibition of LSD1 (LSD1i) in CTL in the context of adoptive T cell therapy (ACT) elicits phenotypic and functional alterations, resulting in a robust antitumor immunity in preclinical models in female mice. In addition, the combination of anti-PDL1 treatment with LSD1i-based ACT eradicates the tumor and leads to long-lasting tumor-free survival in a melanoma model, complementing the limited efficacy of the immune or epigenetic therapy alone. Collectively, these results demonstrate that LSD1 modulation improves antitumoral responses generated by ACT and anti-PDL1 therapy, providing the foundation for their clinical evaluation.

Subject terms: Tumour immunology, Immunotherapy, Cancer immunotherapy

The lysine-specific histone demethylase 1 A (LSD1) can regulate cytotoxic CD8 T cell (CTL) responses and anti-tumor immunity. Here the authors show that ex vivo epigenetic reprogramming with a LSD1 inhibitor enhances cell persistence and anti-tumor activity of adoptively transferred CD8 T cells in preclinical tumor models.

Introduction

Adoptive cell therapy (ACT) harnesses the full potential of CD8 + T cells (CTL) to recognize and eliminate the tumor. Despite remarkable results achieved on different tumor types1–4 and tens of completed and active clinical trials worldwide, the response of solid tumors to this personalized therapy ACT is still marginal5. Longevity, persistence and functionality are critical determinants of T cell-based therapies6,7 and the phenotype of T cell products can profoundly impact therapy efficacy8. Indeed, while the acquisition of a dysfunctional state during the in vitro expansion impairs T cells survival and persistence into the patient after infusion9, the loss of metabolic plasticity hampers T cells ability to adapt and survive in the hostile10–12 and immunosuppressive13 tumor microenvironment (TME). In this scenario, maintaining T cells in a less-differentiated state and preserving their plasticity and fitness during ex vivo production and after infusion may have a strong therapeutic impact.

Recently, chromatin remodeling factors emerged as master regulators of mouse and human CD8 + T cell differentiation14, postulating that epigenetic reprogramming of CTL could burst their intra-tumor fitness and improve response to immunotherapy. In this regard, the lysine-specific histone demethylase 1 A (LSD1) could have distinct therapeutic potential, because is highly expressed in several cancers15,16 and has the ability to modulate exhausted CTL17,18 and anti-tumor immunity19,20.

Here, we report a role for LSD1 in directly regulating CTL differentiation, function and anti-tumor response, providing evidence that ex vivo epigenetic reprogramming of CTL through LSD1 inhibition (LSD1i) imprints a less-differentiated fate and ameliorates T cell exhaustion, ultimately enhancing their persistence and anti-tumor activity in vivo. A rationally-designed combination with anti-PDL1 and LSD1i therapy results in complete tumor eradication and long-lasting tumor-free survival. In conclusion, our study demonstrates that LSD1 could be considered as an actionable target to fine-tune CTL functionality and fitness maintenance, linking CTL epigenetic tweaking to anti-tumor surveillance. This paves the way for a new generation of immunotherapies.

Results

LSD1i shapes differentiation in CTL

Epigenetic dynamics play a major role in dictating CTL differentiation into memory, effector, and exhausted phenotype by controlling specific transcriptional programs at precise stages of the immune responses21–28.

In this study, we explored candidate epigenetic drugs (EpiDrug) that target the main chromatin-modifying enzymes to identify epigenetic modulators able to overcome some of the major roadblocks of cancer immunity, including insufficient T cell potency, survival, and persistence8,29. Thus, we tested the effect of a panel of drugs targeting chromatin modifiers (EpiDrug) on CTL activation by measuring their phenotype and function in comparison with controls (Fig. Supplementary 1A) at concentrations not affecting their viability (Fig. Supplementary 1B, all details in Supplementary Table 1). We found that inhibitors targeting the histone demethylase LSD1 and the histone methyltransferases SUV39H1, EZH2 and DNMT3A supported the generation of CTL with a central memory (TCM) phenotype, which we identified as CD44highCD62Lhigh (Fig. Supplementary 1C). On the contrary, CTL activated in the presence of HDAC and BET inhibitors showed increased frequencies of CD44highCD62Llow short-lived terminal effector CTL (TEFF), identified as CD44highCD62Llow cells (Fig. Supplementary 1D). Nonetheless, only CTL treated with LSD1 inhibitor (LSD1i) were predominantly enriched in CD44highCD62Llow TCM with a reduced frequency of CD44highCD62Llow TEFF (Fig. Supplementary 1C, D), which hold superior in vivo persistence after adoptive transfer30. Likewise, a remarkable upregulation of Eomes31,32 - a transcription factor crucial for TCM formation - was registered solely in LSD1i-treated cells (Fig. Supplementary 1E). These data suggested that LSD1 might have a unique role in shaping CTL differentiation away from TEFF and toward a TCM phenotype and motivated further investigation on the use of LSD1i during ex vivo T cell culture.

LSD1i ex vivo induces a memory transcriptional signature in CTL

LSD1i holds the premise of treating different types of cancers15,33 by modulating tumor growth, while enhancing the effector function of tumor-infiltrating CTL17,19,20. However, the role of LSD1i in regulating normal T cell activation and differentiation is yet to be determined. We examined the effects of the LSD1i MC_258034 on CTL fate and function and compared them with controls (LSD1i- versus CTR-CTL) (experimental scheme, Fig. 1A) at a concentration (i.e. 2 μM) that inhibits the proliferation of cancer cell lines35, while preserving CTL viability (Fig. Supplementary 2A) and shaping their differentiation (Fig. Supplementary 2A-C), aiming to modulate both T cell biology and tumor growth.

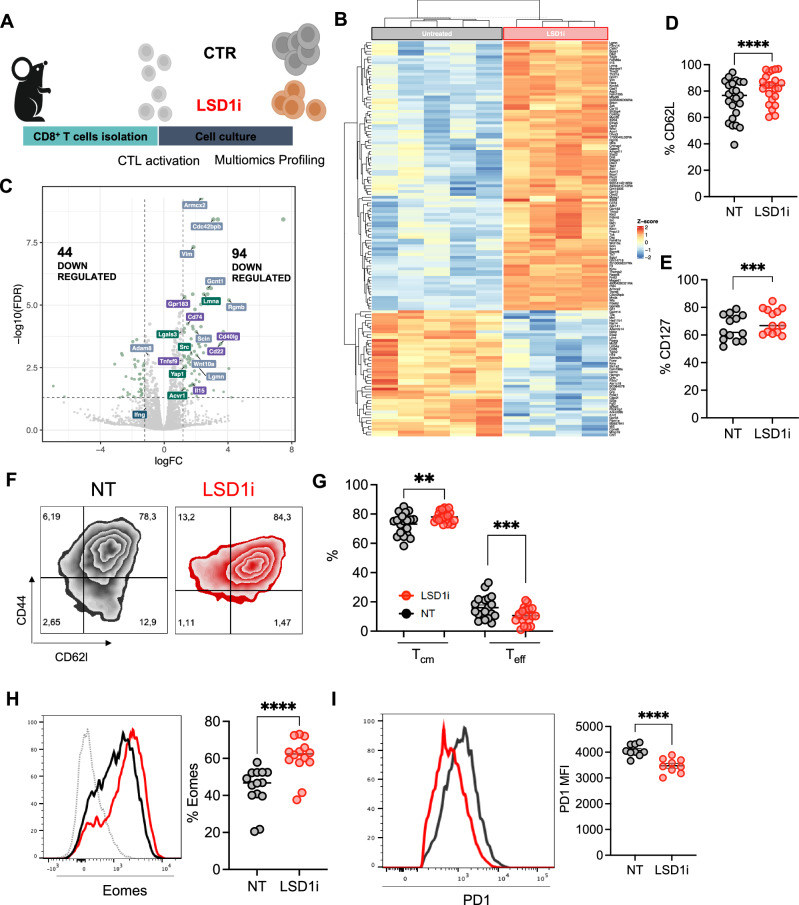

Fig. 1. LSD1i treatment promotes a memory-like phenotype in CTL.

A Experimental design created with BioRender.com (released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International license). CTL were isolated from the spleen and lymph nodes of C57B6 mice and activated with anti-CD28, anti-CD3, and IL2 in the presence or absence of LSD1i for 72 h. B Heatmap showing DEGs in LSD1i and CTR-CTL as assessed by RNA-seq (FDR < 0.05 and linear logFC > 1.2, n = 4). C Volcano plot showing DEGs in LSD1i and CTR-CTL (n = 4). The dot size reflects the significance of each gene. DEGs (FDR < 0.05 and linear logFC > 1.2) are highlighted in light green. Label color code identify genes from different pathways found significatively enriched in IPA analysis. D–H Memory characterization measured as percentage of expression of CD62L (D, n = 24, p < 0,0001), CD127 (E, n = 14, p = 0,0007), frequencies of memory CD44highCD62Lhigh (TCM, p = 0,0041) and effector CD44high CD62Llow (TEFF, p = 0,0005) cells (F, G, n = 24); and Eomes (H, n = 14,, p < 0,0001). I PD1 expression levels (n = 9, p < 0,0001). Data shown as symbols indicate mean ± SEM, two-tailed paired t-test (D, E, G, H, I). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

LSD1i-CTL and CTR-CTL hold the same rate of proliferation - as assessed by the CFSE in vitro assay (Fig. Supplementary 2D) - and activation – as demonstrated by surface expression of canonical markers of activation (Fig. Supplementary 2E) similar to controls (CTR-CTL), indicating that LSD1i does not influences the CTL activation process.

To explore the mechanism by which LSD1 influences CTL fate and function, we performed a transcriptional analysis of CTL, which highlighted that -upon LSD1i- CTL had 138 differentially expressed genes (DEGs, 44 down-regulated and 94 up-regulated, Fig. 1B, C and Supplementary Data 1). Among the upregulated DEGs, we detected markers of long-lived memory cells (i.e. Sell and Il15) genes36, the transcription factor Eomes - key player in memory homeostasis37,38 and Ccr10 and Klrc1 - associated with optimal formation of memory T cells (i.e. Ccr10 and Klrc1) (Fig. Supplementary 2F). In accordance with the induction of a memory signature, LSD1i modulated genes positively associated with CTL proliferation and survival (i.e. Gpr183, Tnfsf9, Cd40lg, Cd22, Il15; Fig. 1C) as well as negative regulators of apoptosis (i.e. Src, Lgals3, Acvr1, Yap1; Fig. 1C). Of note, the transcriptional analysis also showed a significant upregulation of genes involved in T cell migration and cytoskeleton remodeling (i.e. Armcx2, Cdc42bpb, Lamna, Rgmb, Wnt10, Adam10; Fig. 1C), suggesting that LSD1-CTL could be recruited better at the tumor site.

We validated some of these changes independently by real-time PCR (n = 84), confirming up-regulation of memory-related genes (i.e Sell, Eomes, Jun, Il15, Cd40lg; Fig. Supplementary 2G) and down-regulation of genes promoting effector functions (i.e Granzymes, Ifng and Fas-ligand, Fig. Supplementary 2G) in LSD1i-CTL compared with CTR-CTL, which supported the induction of a memory-like signature. Importantly, these genes were regulated similarly when treating CTL with a different irreversible LSD1i (DDP3800339, Fig. Supplementary 2H) as well as in published transcriptional profiling of LSD1 conditional knockout CTL (Cd4CreLsd1f/f, cKO)17 (Fig. Supplementary 2I, J), supporting the on-target effect of the LSD1i MC_2580. Taken together, these data demonstrated that genetic and pharmacological inhibition of LSD1 yield similar transcriptional outcomes in CTL, imprinting a less-differentiated memory state.

LSD1i ex vivo skews CTL towards a memory phenotype

Next, the role of LSD1i in skewing CTL toward a memory-like phenotype was independently validated by multiparametric, high-dimensional flow cytometry. We found that LSD1i favored the expression of canonical memory-associated markers such as CD62L (Fig. 1D) and CD127 (Fig. 1E) – which resulted in the enrichment of the TCM pool at the expense of TEFF cells in LSD1i-CTL compared with CTR-CTL (Fig. 1F, G). Likewise, LSD1i increased the levels of memory-associated transcription factor Eomes (Fig. 1H) and lowered37 the expression of the effector-associated transcription factor Tbet (Fig. Supplementary 3A) as well as the production of effector cytokines (i.e. IFNγ, Fig. Supplementary 3B) and cytotoxic molecules (i.e. Granzymeβ and Perforin, Fig. Supplementary 3C, D) compared to CTR-CTL, which have been demonstrated to negatively correlate with anti-tumor efficacy40, thus reinforcing the concept that LSD1i promote a less-differentiated phenotype in CTL.

Since mitochondrial respiratory capacity is a critical regulator of memory CTL41, we asked whether LSD1i impacts on CTL cellular metabolism. We observed a significant increase in mitochondrial activity upon LSD1i treatment, as detected by an increased in MitoTracker Orange CMTMRos staining (Fig. Supplementary 3E). Consistently, real-time analysis of their bioenergetic profile by Seahorse highlighted that LSD1i-CTL were more energetic (Fig. Supplementary 3F), with a significantly higher O2 consumption rate (OCR; Fig. Supplementary 3G) and SRC (Fig. Supplementary 3H), which are metabolic hallmarks of memory T cells42. Taken together, these data pointed a role for LSD1i in skewing CTL toward a memory phenotype coupled with improved metabolic fitness, potentially allowing for improved functionality under stressful conditions.

These observations were corroborated by a significant drop in PD-1 expression specifically detected in LSD1i-CTL compared to untreated controls (Fig. 1I) and CTL treated with different Epi-Drugs (Fig. Supplementary 1F), which was not due to a diminished activation of LSD1-CTL (Fig. Supplementary 2E) and, thus, might suggest that LSD1i treatment might mitigate exhaustion within the TME.

We obtained similar results in the context of antigen-specific T cell stimulation using CTL from OT1 and P14 mice (which express a transgenic TCR that recognizes OVA and LCMV GP antigens, respectively), with LSD1i-treated T cells displaying Eomes upregulation and PD-1 downregulation (Fig. Supplementary 3I-L). Notably, when LSD1i was administered to CTL post-activation (Fig. Supplementary 3M), it failed to induce a memory-enriched CTL population (Fig. Supplementary 3N) and, conversely, lifted PD-1 levels (Fig. Supplementary 3O), confirming that LSD1i should be provided during the activation in order to positively impact CTL phenotype43. Finally, we tested the selectivity and specificity of LSD1 inhibition by assaying in parallel the activity of additional LSD1 inhibitors (DDP_38003, GSK2879552 2HCl, Bomedemstat and Pulrodemstat (CC-90011) besylate), none of which were toxic to CTL (Fig. Supplementary 4A). All tested chemicals stimulated a central memory phenotype within the CD8 compartment (Fig. Supplementary 4B, C) with Eomes upregulation (Fig. Supplementary 4D) and PD-1 down-regulation (Fig. Supplementary 4E), further demonstrating the specificity and unicity of LSD1 inhibition in regulating CTL fate by fostering a memory program in CTLs. Overall, these results demonstrate a critical role of LSD1 in regulating T cell memory and exhaustion, which provides a promising avenue for LSD1-based reprogramming strategy to arm immune-based cellular therapies.

Ex vivo LSD1i enhances efficacy of ACT therapy

Above mentioned evidences suggested that LSD1i treatment might improve ACT efficacy. Thus, we evaluated whether the memory-like phenotype and PD-1 down-regulation conferred by LSD1i in vitro treatment might enable CTL to better adapt to the immunosuppressive TME in vivo, persisting longer and mediating a durable tumor control. We employed the established B16-OVA melanoma and generated OVA-specific T cells ex vivo in the presence or absence of LSD1i (LSD1-ACT and ACT, respectively; experimental scheme in Fig. 2A),). One week from intravenous injection in tumor-bearing mice, CTL were significantly enriched in the population of tumor-infiltrating immune cells in LSD1-ACT compared to ACT controls (Fig. 2B) that could be due to their improved ability to migrate (Fig. 1B, C), and survive as memory cells (Fig. 1F, G).

Fig. 2. LSD1 inhibition during ex vivo T cell expansion increases ACT efficacy.

A ACT experimental design created with BioRender.com (released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International license). B–I Analysis of the CTL infiltrate 7 days post-infusion. Frequencies of CD8+ (within total CD45+) infiltrating the tumor (B, n = 8, p < 0,0001), tSNE representation based on PD1 and IFNγ (C, D), exhaustion profile assessed as PD1highCD44low (E, F, n = 7 for NT and n = 10 for LSD1i p < 0,0001), frequencies of IFNγ-secreting CTL (G, n = 8, p = 0,0013) and TIM3+ CTL (H, n = 6 for NT and n = 8 for LSD1i, p = 0,0475), mitochondrial activity assessed with MitoTR Orange (I, n = 3–4, p = 0,0343) J Tumor growth curve (n = 23 for CTR-ACT, 21 for LSD1iACT, and 17 for No-ACT; 4 independent experiments, p = 0,0006). Data shown as box and whisker plots (B, F, G, H) or floating bars (I) indicate Min to Max value, two-tailed unpaired t test (B, F, G, H, I, J). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (tSNE) analysis of high-dimensional flow cytometry data confirmed that LSD1i-CTL and CTRL-CTL had substantially different profiles (Fig. 2C) and identified two CTL clusters (CL): CL1, characterized by high PD-1 and low IFNγ levels, was overrepresented in CTRL-CTL, and CL2, characterized by lower PD-1 and higher IFNγ expression, was specifically enriched in LSD1i-CTL (Fig. 2D). Manual gating strategy revealed that tumor from LSD1i-ACT mice bore more-functional CTL compared to those from ACT controls, as indicated by the lower frequency of PD1-expressing CTL (Fig. Supplementary 5D) and terminally exhausted CD44low PD1high CTL (Fig. 2E, F), their higher ability to secrete IFNγ (Fig. 2G) as well as the decrease of TIM3 expression (Fig. 2H). Notably, LSD1i-CTL preserved their superior mitochondrial activity within the TME compared with CTR-CTL (Fig. 2I), confirming that LSD1i-CTL better coped with the metabolic constraints imposed by the TME. Therefore, ex vivo treatment with LSD1i prior to transfer favors a quick and strong recall in vivo early (7 days) after transfer.

These features enabled LSD1-ACT to control tumors more efficiently demonstrating their superior therapeutic potential (Fig. 2J and Supplementary 5A, B) without evidence of adverse toxicities (i.e. no change in overall body weight, Fig. Supplementary 5C). Interestingly, tumors from LSD1i-ACT were enriched in both tumor-specific (Vβ5.2+) and bystander (Vβ5.2−; Fig. Supplementary 5E) CTL within the CD8 compartment, both characterized by a less exhausted phenotype (i.e. increased IFNγ production and pronounced PD-1 down-regulation, Fig. Supplementary 5F, G). Thus, ex vivo treatment with LSD1i promotes optimal intra-tumoral infiltration and effector functions of both tumor-specific and antigen-independent CTL.

Of note, the anti-tumoral efficacy of LSD1i-CTL was superior compared to those treated ex vivo with the SUV39H1 inhibitor chaetocin44 (CHETO-ACT, Fig. Supplementary 5H); despite the enrichment of TCM observed upon SUV39H1 inhibition (Fig. Supplementary 1C) confirming previous studies45,46.

Finally, we confirmed these results in a more clinically relevant context, using T cells derived from pmel-1 TCR–Tg mice and specific for the self/tumor antigen gp100, which has been targeted also in human clinical trials47. Pmel-1 CTL were first skewed ex vivo towards a memory phenotype with LSD1i (Fig. Supplementary 5I) and then adoptively transferred into lymphodepleted C57BL6 WT mice bearing subcutaneous B16-F10 tumors to test their in vivo antitumor functions40,48. Despite the noticeable activity of CTR-Pmel-1-CTL, LSD1i-Pmel-CTL were able to control B16-F10 tumor more effectively (Fig. Supplementary 5J). These results demonstrated that LSD1i treatment could improve CTL anti-tumor responses also in poorly immunogenic and unmanipulated solid, resulting in more potent acute tumor debulking.

LSD1i improves CAR-T cell therapy efficacy

Next, the therapeutic potential of our findings was consolidated in vitro using human CTL, where we confirmed a significant up-regulation of CD62L expression (Fig. Supplementary 6A), which translates in the induction of a less-differentiated phenotype after long-term culture conditions (day 10; Fig. Supplementary 6B). Thus, similar to what we observed in mice, LSD1i also shapes memory fate in human CTLs.

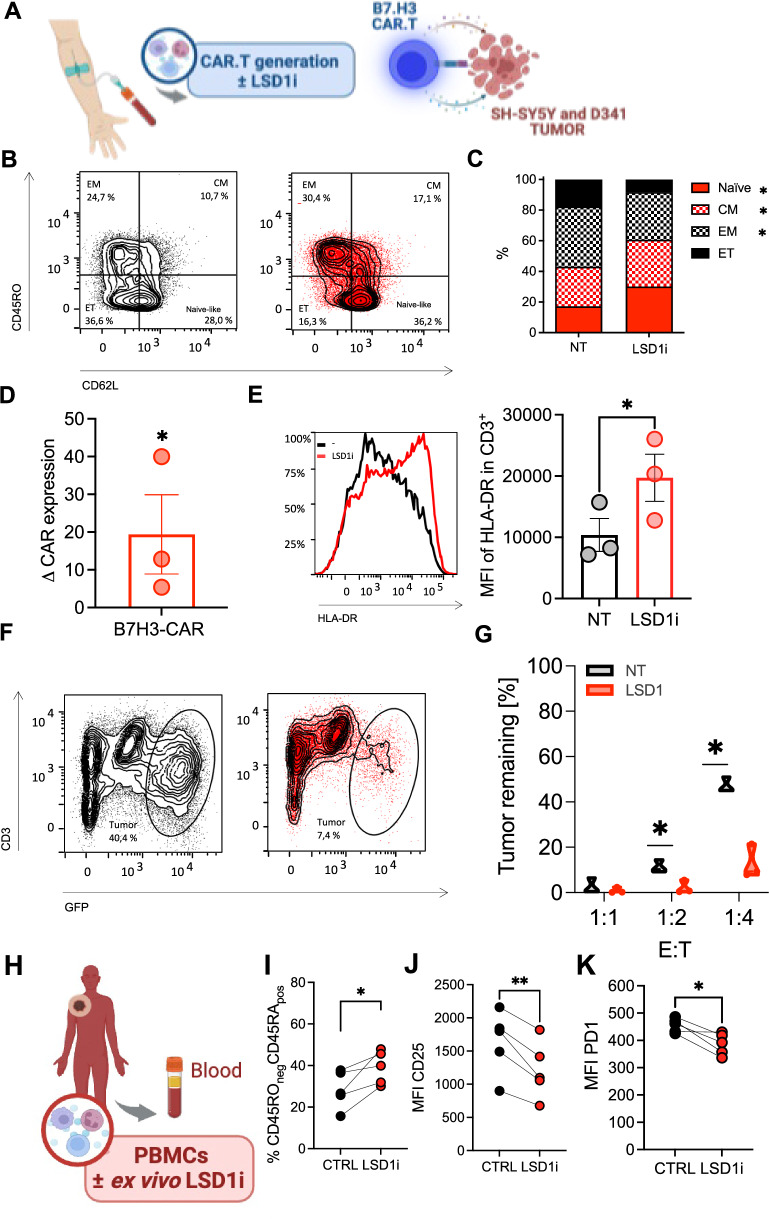

Therefore, we conducted similar tests on human chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR.T), assaying phenotype and pre-clinical performance upon LSD1i-tretment in comparison with CTR (Fig. 3A). As model, we opted to target the B7-H3 molecules which has been extensively validated to be expressed on several solid malignancies using a third-generation B7-H3.CAR49,50. In accordance with the data presented above, we found that LSD1i treatment promoted a less differentiated phenotype, with an increased frequency of TCM and naive-like T cells, the concomitant decrease of TEFF cells (Fig. 3B, C and Fig. Supplementary 6A, B) and augmenting CAR expression (Fig. 3D), which are all intrinsic determinants of CAR-T therapy efficacy51. Thus, we tested whether LSD1i might affect the cytotoxic capabilities when incubated with a higher proportions of tumor cells (effectors:tumor cells ratio E:T = 1:2 and 1:4) a long-term co-culture assay with a model of neuroblastoma (SHSY5Y; Fig. 3E–G) and one of medulloblastoma (D341; Fig. Supplementary 6C–E). Remarkably, LSD1i-treated CAR.T expressed higher level of HLA-DR compared to controls (Fig. 3E and Supplemetary 6C), after co-culture with tumor cell lines, indicative of an enhanced tumor-specific anti-tumoral function. Indeed, LSD1i-treated CAR-T cells displayed a better anti-tumor activity compared to control CAR-T cells. This phenomenon was more evident at low effector:target ratio (1:2 and 1:4) (Fig. 3F, G and Supplementary 6D, E) indicating that LSD1i enhances CAR-T cell functional performances. Finally, we wonder whether LSD1 inhibition could potentially ameliorate the dysfunctional state of CTL usually detected in patients, which represents a major limitation for the generation of sufficient and functional CAR.T. This was achieved thawing and activating in vitro cryopreserved CTL from metastatic melanoma patients in the presence or not LSD1i (Fig. 3H). Also, in this case we found that LSD1i increased the frequency of a less-differentiated naive-like phenotype (Fig. 3I, J) and resulted in a significant decrease in the surface expression levels of PD-1 (Fig. 3K); confirming that it could be used ex vivo to improve the quality of CTL from cancer patients to be used as ACT products.

Fig. 3. LSD1 inhibition promote functional activity of human CAR.T.

A Experimental design created with BioRender.com (released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International license). Human T cells were isolated from heathy donors and CAR.T were generated in the presence or absence of LSD1i. B–E Phenotypic characterization of human CD8 T cells (n = 3). Percentage of Tnaive-like (p = 0,0196), TCM (p = 0,0396), TEM (p = 0,0141), and TET (B), expression levels of CAR construct (D, p = 0,0449) and HLA-DR after long-term co-culture with tumor cells (E, p = 0,0408). F, G Functional activity of long-term killing assays of B7.H3 CAR T cells generated ±LSD1i against SHSY5Y (n = 3). H–K Human T cells were isolated from metastatic melanoma patients and activated in vitro long-term culture ±LSD1i (H, created with BioRender.com). Phenotypic characterization assessed as frequencies of CD45RA+ CD45RO- naïve-like T cells (I, n = 7, p = 0,0387), CD25 (J, n = 7, p = 0,0059) and PD1 expression (K, n = 7, p = 0,0210). Data shown as bar plot (C, D, E), truncated violin plot (G) or symbols (I, J, K) indicate mean ± SEM, two-tailed unpaired t test (C, D, E, G, I, J, K). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

LSD1i enforces an PD-1/PD-L1 axis between T cells and tumor

Despite the significant improvement in acute tumor control, multiparametric analysis of tumor-infiltrating LSD1i-CTL on day 14 after the adoptive transfer did not show any substantial improvement in LSD1i-ACT compared to CTR-ACT. Indeed, frequencies of IFNγ-secreting CTL were comparable between LSD1i-ACT and CTR-ACT mice (Fig. Supplementary 7A). Surprisingly, PD-1high CD44low (Fig. Supplementary 7B) and PD1+IFNγ- “exhausted” CTL (Fig. Supplementary 7C)- were even significantly more abundant in LSD1i-CTL, suggesting that LSD1i-induced reprogramming in CTL did not persist.

Thus, we sought to mechanistically define how LSD1i-CTL would revert to a dysfunctional state. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) of total RNAseq data to identify upstream regulators of the observed changes in gene expression pointed at IFNγ response pathway and its upstream regulators Sox4 and IL12 as the most significatively activated hits (Fig. 4A), in spite of the overall reduction of Ifng gene transcript observed in LSD1i-CTL (Fig. Supplementary 2E and S2H). Of note, genes contributing to this signature were similarly modulated in LSD1i-CTL (Fig. Supplementary 7D) and in LSD1-KO CTL17 (Fig. Supplementary 7E), providing further evidence of an emerging IFNγ-dependent response induced by LSD1i52,53. We independently confirmed this result at protein level, demonstrating that restimulated LSD1i-CTL produce higher amount of IFNγ (Fig. 4B and S7F), albeit comparable cytotoxic abilities of LSD1i- or CTR-CTL (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4. LSD1i treatment induces up-regulation of PD1/PDL1 axes.

A Bubble plot showing IPA prediction of upstream regulator TF based on DEG resulted from RNAseq analysis (n = 3). TF are divided based on the prediction of Activated or Inhibited: size represents the -log10(Pvalue) while color indicates the Zscore. B IFNγ production (n = 18, p = 0,0111) and C killing capacity of CTL±LSD1i (n = 11). D–F IFNγ production in CTL (D, n = 7, p = 0,0228 at 2 h and p = 0,0306 at 24 h), PD1 (E, n = 4, p = 0,0460 at 2 h and p = 0,0493 at 24 h) and PDL1 (F, n = 7, p = 0,0339 at 24 h) expression on B16-OVA tumor cells and CTL ±LSD1i, respectively, in co-culture 1:1 B16-OVA tumor cells. Data shown as box and whisker plots indicate Min to Max value (B-F), two-tailed paired t test (B, C), and two-tailed one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (D–F). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Higher IFNγ levels have been shown to exert the opposite effect on tumor cells. On the one hand, it is needed to sensitize the tumor cells to be killed54–56, while on the other hand, it can induce PD-L1 up-regulation in the TME, which promotes PD-1 signaling in CTL and decreases their effector functions57,58. To prove this hypothesis, we followed the dynamic of expression of PD1 and PDL1 in correlation with IFNγ production by CTL in co-culture with B16-OVA tumors (for 2, 12, and 24 h, Fig. 4D–F). We observed that PD1 and PDL1 upregulation on CTL and tumor cells was directly correlated to IFNγ secretion from LSD1i-CTL (Fig. 4E, F). Indeed, as early as 2 h, LSD1i-CTL - compared with CTR-CTL- hold lower levels of IFNγ and PD1, indicating that after short-term exposure to the tumor antigen, LSD1i-CTL are still in a less-differentiated effector phenotype. Over time with persisting antigen stimulation (12 h), LSD1i-CTL loses the advantages given in vitro by LSD1i and becomes similar to CTR-CTL. At later time point (24 h), LSD1i-CTL produced significantly more IFNγ, which was paralleled by significantly higher levels of PD-L1 on tumor cells and PD1 on CTL. Of note, this was specifically induced by LSD1i-treated CTL because LSD1i alone on tumor cells did not induce PD-L1 upregulation (Fig. Supplementary 7H). Finally, by blocking IFNγ with anti-IFNγ antibody, we abrogated PDL1 upregulation on tumor cells, demonstrating that LSDi-CTL induced PDL1 up-regulation through IFNγ (Fig. Supplementary 7I). Thus, we conclude that LSD1i enforces an PD-1/PD-L1 axis between T cells and tumor, which might be responsible for the loss of the functional advantages given in vitro by LSD1i and the subsequent lack of long-lasting tumor immunosurveillance.

The combination of LSD1i-based ACT and anti-PDL1 therapy promotes long-lasting anti-tumor response and establishes immunosurveillance

Our data suggested that LSD1i-CTL initiates an IFNγ response that promotes tumor attack by CTL while also inducing PD-L1 expression on tumor cells, which blunts CTL activity favoring an exhaustion state. We reasoned that therapeutic blocking of PD-L1 in combination with LSD1i may prevent the exhaustion caused by the enhanced IFNγ production in the TME. Therefore, we combined ACT with an anti-PDL1 blocking antibody and evaluated its effectiveness compared to each of the monotherapies. We found that the combination of LSD1i-ACT with anti-PDL1 therapy drastically reduced tumor growth in the B16-OVA melanoma model, while benefits were negligible with CTR-ACT (Fig. 5A, B and Suppelmantary 8A).

Fig. 5. LSD1 inhibition and anti-PDL1 increases ACT efficacy.

A–C Tumor growth curve (A), tumor volume at the time of sacrifice (B), and survival (C) for CTR-ACT (n = 24), LSD1i-ACT (n = 29), no ACT (n = 17), LSD1i-ACT+anti-PDL1 (n = 28), CTR-ACT+anti-PDL1 (n = 8) and no ACT+ anti-PDL1 (n = 6) therapy. p values calculated with two-tailed unpaired t test (A,B) and Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test (C). D Tumor rechallenge experiment in mice that rejected the tumor after LSD1i-ACT+anti-PDL1 therapy (D, n = 7). Naive mice were injected as controls (n = 15). E–J Analysis of the CTL infiltrate in surviving mice (after 35 days). Frequencies of tumor-specific (E, n = 6 for NT and n = 9 for LSD1i, p = 0,0289), representative plot and frequencies of of PD1+ (F–G, n = 4, p = 0,0461) and PD1+TIM3+ (H, n = 4, p = 0,0734) in Vβ+ CTL, representative plot and percentages of IFNγ-secreting (I, J, n = 10, p = 0,0289) Vβ+ CTL. Data shown as symbols indicate mean ± SEM (B, E, G, H, J), two-tailed unpaired t test (B, E, G, H, J). Source data are and exact p value are provided as a Source Data file.

To study the mechanism underlying such potent tumor debulking operated by the combined LSD1i + αPDL1 treatment, we used a CD45.1+ mouse model with established B16-OVA tumor as the recipient of an adoptive transfer of OTI derived from CD45.2+ donor, which enabled tracking of donor-derived CTL through the CD45.2 congenic marker (Fig. Supplementary 8B). We found that tumor-specific Vβ5.2+ CTL generated in vitro in presence of LSD1i (LSD1i-CTL) were increased in frequency (Fig. Supplementary 8C) and enriched in the pool of central-memory CTL (Fig. Supplementary 8D) in the peripheral blood of adoptively transferred mice compared to endogenous Vβ5.2- CTL, which was indicative of a superior intra-tumor expansion of LSD1i-CTL. Nevertheless, LSD1i-CTL harbored the higher expression of PD-1 (Fig. Supplementary 8E), thus corroborating our in vitro findings. However, when we looked at tumor-infiltrating cells, we found a more sustained increase of CD45+ cells in mice subjected to LSD1i-ACT and αPDL1 combination as compared to either LSD1i or αPD-L1 single treatment (Fig. Supplementary 8F). Within CD45+ cells, the enrichment of Vβ5.2+ CD3+ cells from the donor was higher when the ACT was performed with LSD1i-CTL (Fig. Supplementary 8G), confirming that LSD1i had an active role in promoting CTL migration and survival into the TME. Furthermore, tumor-infiltrating CTL from LSD1i-ACT mice, both of donor (Fig. Supplementary 8G–I) and host (Fig. Supplementary 8J–L) origin, expressed significantly higher levels of PD-1 (Fig. Supplementary 8H, J) and PD-L1 (Fig. Supplementary 8I), which are markers of immunosuppression and a negative outcome in melanoma patients59. In addition, we observed that LSD1i-ACT induced a significant up-regulation of PD-L1 also on myeloid-derived suppressor cells (identified as CD11b+, Fig. Supplementary 8L) and on tumor cells (identified as CD45-, Fig. Supplementary 8M) in mice receiving LSD1i-ACT. Noticeably, when LSD1i-ACT was combined with αPD-L1 therapy, the up-regulation of PD-L1 was abrogated in all cellular compartments analyzed and, consequently, PD-1 expression on infiltrating TILs was diminished as well (Fig. Supplementary 8G–M).

Most importantly, the combination of LSD1i-ACT and αPD-L1 significantly increased long-term survival of tumor-bearing mice compared with αPDL1 or ACT monotherapy (Fig. 5C). Moreover, the combined treatment elicited tumor-specific immunological memory, as demonstrated by the absence of tumor growth 20 days after re-challenge with B16-OVA tumor in the group of mice treated with LSD1i-ACT plus αPD-L1 mice (Fig. 5D). Finally, when analyzing the tumor-infiltrating CTL of the surviving mice, we noticed that the combination therapy increased the infiltration of tumor-specific CTL (Fig. 5E) and drastically reduced the percentage of exhausted CTL expressing PD-1 or TIM3 inhibitory receptor (Fig. 5F–H), resulting in more functional tumor-specific CTL as compared with monotherapy (Fig. 5I, J).

In all, these data highlighted an underscored feature behind LSD1i-mediated regulation on anti-tumor response and demonstrated a synergy between the two therapies, with LSD1i being instrumental to promote infiltration and survival of a less-differentiated subset of CTL and αPDL1 counteracting the induction of the PD1/PDL1 axis at the tumor site, which explain the potent acute tumor debulking observed in the combined therapy.

Systemic in vivo LSD1i promotes intra-tumoral infiltration of memory-like CTL and increases the effectiveness of anti–PDL1 therapy

To further prove the role of LSD1i in promoting CTL anti-tumor responses and by that enhancing the efficacy of immune-based therapies, we used the syngeneic BP melanoma model, which is known to poorly respond to immunotherapy60 mice systemically with a LSD1i (DDP_38003, as MC_2580 cannot be used in vivo35, Fig. 6A). Alongside the abovementioned migratory signature (Fig. 1B), we observed that in vivo systemic LSD1i promoted intra-tumoral infiltration of CTL (Fig. 6B) with an augmented expression of Eomes (Fig. 6C), higher frequency of CD44high CD62Lhigh (Fig. 6D) and lower levels of PD-1 expression (Fig. 6E). Nevertheless, BP tumors showed identical growth kinetic regardless LSD1i treatment (Fig. 6F and Supplementary 9A-D).

Fig. 6. Systemic in vivo LSD1i promotes intra-tumoral infiltration of memory CTL and improves anti-PDL1 increases ACT efficacy.

A Experimental design of systemic LSD1i therapy. B–F Analysis of the CTL infiltrate at the time of sacrifice. Frequencies of CTL infiltrating the tumor (B, n = 7, p = 0,0070), Eomes expression (C, n = 7, p = 0,0454), percentage of memory and effector cells (D, n = 12, p = 0,0033) and PD1+/CD44- CTL (E, n = 12, p = 0,0038) and tumor growth (F, n = 12). G,H Experimental scheme (G) and tumor growth (H, n = 11 for NT, 14 for LSD1i, 7 for anti-PDL1 and 15 for LSD1i+anti-PDL1, p = 0,0026). Data shown as box and whisker plots indicate Min to Max value (B-E), two-tailed unpaired t test (B–E). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

However, when mice with comparable tumor masses were randomly treated or not with anti-PDL1 therapy (Fig. 6G), the combination of LSD1i and αPD-L1 achieved a better tumor control without any adverse toxicity (Fig. Supplementary 9E); paralleled by a reduction of PD-L1 on immune infiltrating CD11b+CD45+ cells (Fig. Supplementary 9F) while each of the two monotherapies did not (Fig. 6H and Supplementary 9A–D). Importantly, when LSD1i therapy was combined with a different immune checkpoint inhibitor (i.e. αTIM3) we did not observe any therapeutic improvement (Fig. Supplementary 9G), supporting our mechanistic model and indicating the specificity of the proposed combinatory therapy.

Discussion

The advent of adoptive T cell therapy (ACT) has opened a new era in cancer treatment by redirecting CD8+ T cell (CTL) to express synthetic receptors towards tumor-associated antigens. Despite impressive clinical results in the treatment of otherwise incurable hematological malignancies, ACT has not demonstrated convincing efficacy in treating solid tumors, which collectively account for ~90% of cancer-related deaths50,61,62. This upsetting could be attributed to the acquisition of a dysfunctional state, loss of metabolic functional plasticity, and failure to adapt and survive in a hostile tumor microenvironment (TME)8. In this scenario, maintaining CTL in a less-differentiated state and with a higher bioenergetic profile during ex vivo T cell production and after infusion may have a strong therapeutic impact.

Recent findings suggest a major role for epigenetic programs in determining and maintaining T cell fate decisions24,54. T cells may resist current strategies for reversing T cell exhaustion as a result of stable changes in gene regulation due to epigenetic reprogramming22,23,63. For instance, progressive de novo DNA methylation is an essential process inaugurating CD8 + T cell exhaustion. This results in a distinct gene repression signature that is preserved during PD-1 blockade64. Thus, manipulating the activity of demethylating enzymes that contribute in establishing exhaustion and memory programs may hold a key to obtaining a long-lived pool of engineered T cells with sustained anti-tumor responses, and implementing the use of ACT in oncology. In this regard, genetic ablation of SUV39H145,46 in CAR-T cells has been shown to improve T cell memory formation and efficacy of adoptive T-cell therapy. In this scenario, the development of tools such as chemical compounds that enable the generation of therapeutic T cells without relying on additional gene therapy modification offers promising alternatives to increase accessibility and efficiency in the development and delivery of CAR.T therapy.

LSD1 is a lysine-specific histone demethylase 1 A highly expressed in several cancers - such as prostate, breast, and hepatocellular- where it is associated with poor prognosis15. Interestingly, recent studies have underscored the role for LSD1i in influencing anti-tumor immunity19,20 by promoting an epigenetic program that modulates exhausted CTL17,18. However, the impact of perturbing T cell-intrinsic LSD1 on CTL differentiation and function as well as their anti-tumoral responses have not been fully explored. Here, we underscore a role for LSD1i in CTL anti-tumor response being unique in its ability to shape their differentiation towards a peculiar CD62 high/CD44high memory T cell pool characterized by Eomes up-regulation while simultaneously counteract exhaustion through PD1 downregulation that operates a more potent acute tumor debulking.

We identified LSD1 as an important regulator of CTL differentiation and anti-tumor functions. We show that in vitro pharmacological inhibition of LSD1 (LSD1i) is a strategy to enforce CD8 functional specialization in tumors and, in turn, enhance the clinical efficacy of ACT, confirming similar results recently published by Dr. Sheng and colleagues43.

LSD1i imprints a stable less-differentiated fate and ameliorates T cell exhaustion as manifested by inhibitory receptor reduction, enhanced metabolic fitness, and enriched transcriptomic signatures of T cell reinvigoration. As a direct consequence, LSD1i-instructed T cells showed enhanced persistence and antitumor effects in a murine melanoma model of ACT. Additionally, LSD1i treatment confers functional advantages to human CAR.T cells, demonstrating its potential in ameliorating ACT efficacy and broadening its application for the treatment of a wide range of malignancies. Of considerable benefit, our approach concerns the ex vivo treatment of isolated T cells and is not limited by systemic targeting and/or additional gene therapy that would complicate the already intricate manufacturing process of CAR.T cell therapy products. Moreover, the ability of LSD1i to ameliorate the exhausted phenotype of CTL from cancer patients is particularly important for the many cancer patients that cannot benefit from ACT due to severe T cell lymphopenia -resulting in a failure to collect a satisfactory amount of T cells in order to manufacture the CAR T cell product, and a severe T cell exhausted phenotype associated with decreased proliferation and cytotoxicity of the final CAR.T product51,65. It is worth to note that among the tested chemical probes, LSD1i was unique in shaping CTL differentiation away from terminally effector and toward a memory phenotype with increased Eomes expression and decreased PD1 levels, posing LSD1i as a promising tool for modulating CTL differentiation during ex vivo T cell culture. As a matter of fact, the anti-tumoral efficacy of LSD1i-redirected CTL was superior compared to the one observed in mice receiving CTL pre-treated ex vivo with a pharmacological SUV39H1 inhibitor44; despite the fact the inhibition of SUV39H1 was able to enrich the CTL memory compartment (Fig. Supplementary 1C), in agreement with previous studies45,46. Future work is required to fully understand the different mechanisms of actions, specificity, and related efficacy of the different epigenetic drugs currently in use. These studies may also inform about the benefits and side effects related to the use of epigenetic drugs as an approach to improve the efficacy of cancer therapy.

Furthermore, a rationally designed combination with PDL1-therapy makes adoptively transferred CTL resistant to exhaustion, thus granting long-lasting immune-surveillance. We demonstrated the direct role of LSD1i in mediating a CTL reprogramming that improved antitumor immunity, especially in combination with anti-PDL1 therapy. LSD1i leads to an optimal priming of CTL which ameliorates their functional performances and empowers them with improved ability to debulk tumors. Its combination with anti-PDL1 therapy resulted in a complete tumor eradication and long-lasting tumor-free survival, demonstrated that LSD1i together with anti-PDL1 therapy complement each other’s deficiencies and produce a better tumor response in a melanoma model, in which both immune and epigenetic therapy alone have shown limited efficacy. Interestingly, if LSD1i is provided in combination with anti-TIM3 therapy, no synergy was achieved and tumors escaped T cell control. While these results support the specificity of LSD1i in fostering a PD1/PDL1 loop; whether anti-TIM3 and anti-PDL1 treatment activate different CTL activation and/or differentiation programs when combined with LSD1i awaits future investigation. It would be also interesting to assess the effect of another type of checkpoint blockade therapies on LSD1i therapy to define the better combinatorial therapy.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that LSD1 could be considered as a molecular switch to fine-tune memory T cell formation and metabolic fitness maintenance, linking epigenetic drugs to antitumor surveillance. This paves the way for a new generation of adoptive T cell-based therapies, where LSD1i can be used during ex vivo CAR- and TCR- T cell manufacturing or in combination with PDL1 therapy to achieve long-term functionality in melanoma patients with primary or adaptive resistance to immunotherapy.

Methods

Ethics approval for the research

The use of human samples was approved by the European Institute of Oncology (IEO) Institutional Review Board. PBMCs were collected from patients with melanoma undergoing immunotherapy at European Institute of Oncology IRCCS (IEO, Milan IT) before the starting of any treatment. No compensation was paid to patients for participating in the study. All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the protocols were approved by IEO Ethical Committees (registered as IEO889). Blood samples from healthy volunteers were collected at European Institute of Oncology IRCCS (IEO, Milan IT) under an approved protocol (IEO 1781) and signed informed consent.

Mice were housed and bred in a specific-pathogen-free animal facility and treated in accordance with the European Union Guideline on Animal Experiments. Animal handling and experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The Jackson Laboratory under the protocol number 720/2019-PR and 75DA4.N.7PH and under the District Government of Lower Franconia protocol number RUF-55.2.2-2532-2-1452.

Experimental model and subject details

Mice were housed and bred in a specific-pathogen-free animal facility and treated in accordance with the European Union Guideline on Animal Experiments under the protocol number 720/2019. For mouse experiments, we used sex- and age-matched (8-10 weeks) mice in each experiment. For in vivo tumor implantation exp we used female mice to optimize the engraftment. The number of animals (biological replicates) is indicated in the respective figure legends. C57B6 or OT1 (C57BL/6-Tg(TcraTcrb)1100Mjb/Crl) mice were purchased from Charles River. LCMV-P14 TCR transgenic mice were obtained through the Swiss Immunological Mouse Repository (SwImMR, Zurich, Switzerland). Pmel1 mice (B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ Tg(TcraTcrb)8Rest/J) were bred at the animal facility of the University Hospital Regensburg. Mice were kept in SPF conditions with food and water ad libitum. Experiments were approved by the District Government of Italy and Lower Franconia and conducted in line with local and state animal welfare guidelines.

Compounds

MC_2580 and DDP_38003 have been synthesized as previously described39. GSK2879552 2HCl, Bomedemstat and Pulrodemstat (CC-90011) besylate, JQ1, SG1027 and UNC1999 were purchased from Selleckchem. Chaetocin was purchased from Aurogene. Valproic Acid (VPA) was purchased from Sigma.

All the reagents were dissolved in DMSO except for VPA, which was dissolved in water. DMSO was added at a final concentration of 0.01% (v/v), including the control. Epigenetic probes used in the experiments are listed in Table S1 and were used at the indicated concentrations.

Cell lines

BP and B16-OVA were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% Glutamine, 1% Pen/Strep. B16-F10 and B16OVA in complete RPMI supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% Glutamine, 1% Pen/Strep and additional G418 (0,4 mg) antibiotic for the selection and isolation of OVA-transfected B16. Cells were cultured in a humidified environment at 37 °C in 5% CO2.

Killing experiment

For killing experiments, 2.5×104 of B16-OVA cells were plated on a 96-well plate in complete RPMI media (10% FBS, 1% NaPy, 1% Glutamine, 1% Pen/Strep, 0,1% β-mercaptoethanol) supplemented with 100 U/mL IL2 to adhere prior to co- culture with activated OT1 CD8 + T cells. OT1 CTL activated in the presence or absence of LSD1i for 72 hours were then counted and added to the plate in a Effector: Target (E:T) ratio of 1:1. 2,12 and 24 hours post-co-culture, cells were stained, fixed and permeabilized following manufacturer’s instruction for multiparametric flow cytometry analysis.

CD8 + T cell isolation and activation

Spleen and lymph nodes (inguinal and axillary) were harvested from mice under sterile conditions, mechanically dissociated into single cell suspension and red blood cells were lysed. Cells were then sorted by negative selection following the manufacturer’s instructions. After sorting, cells were resuspended at 1×106 cells/mL in complete RPMI media (10% FBS, 1% NaPy, 1% Glutamine, 1% Pen/Strep, 0,1% β-mercaptoethanol) supplemented with 100 U/mL IL2. For OT1 and P14 CD8+ T cells, media was further complemented with 2 μg/mL of SIINFEKL, GP100 or GP-33 peptides respectively, while for C57B6 mice polyclonal activation was achieved using 5 μg/mL plated-bound αCD3 and 0,5 μg/mL soluble αCD28. Cells were further treated with EpiDrugs at the indicated concentration for 72 hours at 37 °C, 5% CO2 and 90-95% humidity for a pH neutral environment.

Immunophenotype and flow cytometry

Characterization of the activation and differentiation profile of CTL was performed by flow cytometry following standard protocols. Briefly, for staining of surface markers 1 × 105 – 2 × 106 cells were harvested at the specified post-activation time points, washed with PBS, resuspended in FACS buffer (PBS, 2% FBS, EDTA 2 mM) and stained for 20 minutes at 4 °C. Intracellular staining for cytokine production was performed following a 4 hours incubation with complete RPMI and 1:1000 dilution of GlogiPlug in the presence or absence of a secondary stimulation with SIINFELK peptide (5 μg/mL) or PMA/Ionomycin (20 ng/mL and 1 μg/mL respectively) at 37 °C. Cells were fixed and permeabilized following manufacturer’s instruction. Intracellular staining was then performed in permeabilization buffer for 2 hours at 4 °C. For mitochondrial studies, cells were incubated with 25 nM MitoTracker Orange CMTMRos (Life Technologies) for 30 min at 37 °C before staining. All panels were stained with LIVE/DEAD fixable Aqua stain or Ghost Dyes from TONBO before surface or intracellular staining. UltraComp eBeads were used for all compensation. All FACS data were acquired using a BD-FACSCelesta or BD FACSAria Fusion and analyzed with FlowJo software.

RT2 Profiler PCR arrays

Gene expression analysis of 84 key genes involved in memory differentiation pathway was assessed on vitro–activated CD8 + T cells ± LSD1i using a Mouse T cell differentiation RT2 Profiler PCR Array (Qiagen; PAMM-074ZC) according to manufacturer instructions. Ct values were exported to an Excel file for data analysis using the provided web tools (http://www.qiagen.com/geneglobe). Ct values were normalized based on a panel of reference genes. The data analysis web portal calculates fold changes using using the ΔΔCt method followed by ΔΔCt calculation (ΔCttest group − ΔCtcontrol group). Fold change is then calculated using 2(−ΔΔCt) formula. Data were plotted using volcan plot.

tSNE analysis

FCS data was analyzed with software FlowJo v10.2. RPhenograph package was used to perform computational analysis of multiparametric flow cytometry data. 3000 events per sample were concatenated by the “cytof_exprsMerge function”, after manual gating isolation of singlet, LD negative CD45 + CD3 + CD8 + T cells. All samples were concatenated by the “cytof_exprsMerge function”. /). The number of nearest neighbors identified in the first iteration of the algorithm, K value, was set to 100. UMAP and tSNE representation were generated and visualized using FlowJo version 10.2. Under-represented clusters ( < 0.5%) were discarded in subsequent analysis.

Seahorse extracellular flux analysis

Seahorse experiments were performed on sorted CD8+ cells activated in presence or absence of LSDi using XF Cell Mito Stress kit (Seahorse Bioscience). OCR and ECAR were measured with XF96 Extracellular Flux Analyzers (Seahorse Bioscience). Briefly, cells were plated on poly-D-lysine–coated 96-well polystyrene Seahorse plates (200,000 T cells/well), equilibrated for 1 h at 37 °C, and assayed for OCR (pmol/min) and ECAR (mpH/min) in basal conditions and after addition of oligomycin (1 μM), carbonyl cyanide-4-phenylhydrazone(1.5 μM), and antimycin A/rotenone (1 μM/0.1 μM).

RNA sequencing and data analysis

CD8+ cells were activated for 72 h in presence or absence of LSDi, counted and resuspended in RTL lysis buffer (Qiagen). RNA was isolated from purified cells using RNeasy Mini Kits, and RNA concentrations were determined using Nanodrop. Raw reads were mapped to the mouse reference genome mm9 using STAR66. Reads quantification was calculated using the featureCount function of the Subread package67. Batch correction of the CTL-LSDi samples was assessed with the R package sva, using the command ComBat_seq specifying as group the NT and LSD1i and as batch the two different run of sequencing68. edgeR was used to assess differential expression, following the edgeR user’s guide command of the Generalized linear models section, starting from the batch-corrected counts table obtained removing genes with zero reads counts69. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were defined as those showing FDR ≤ 0.05 and linear fold-change ≥1.2. Pathway analysis and transcription factor prediction analysis were performed with QIAGEN’s Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA, QIAGEN Redwood City, www.qiagen.com/ingenuity).

In vivo animal experiments

All mouse experiments were conducted in agreement with requirements permitted by our ethical committee. C57B6 were subcutaneously injected with 2 × 105 B16-OVA\BP\B16-F10 cells/mouse. Animals were euthanized when the tumor reached the volume of ≥ 2 cm3 or when tumors become ulcerated or interfere with the ability of the animal to eat, drink, or ambulate, according to our national ethical committee. Spleens and tumors were harvested and dissociated to a single-cell suspension. Tumors were digested (1 mg/mL Collagenase A and 0.1 mg/mL DNase I) in DMEM at 37 °C. Cell suspension was filtered first through 100 μm and secondly through 70 μm cell strainers, washed, counted, and stained for multiparametric flow cytometry. Blood was collected in an Eppendorf with EDTA and, after red blood cells lysis (Mylteni, Cat. 130-094-183), cells were washed twice with PBS, counted, and stained for multiparametric flow cytometry.

For in vivo experiments, checkpoint blockade was performed by intraperitoneal injection of 200 ug anti-mouse PD-L1 (clone 10 F.9G2, Leinco Technologies), 200 ug anti-mouse TIM3 (clone RMT3-23, Leinco Technologies) or isotype control anti-rat IgG2gb, Kappa immunoglobulin (clone R1371, Leinco Technologies) based on the following treatment schedule: five days after ACT and every other day (day 15\17\19), i.p. for three times. For indicated experiment, C57B6 were rechallenged with 2 × 105 B16-OVA cells/mouse 3 days after the last anti-mouse PD-L1 injection (day21). For in vivo systemic LSD1 inhibition LSD1i DDP_38003 at the dose of 34 mg/kg was administered by oral gavage twice a week once tumors had reached a measurable size for 3 times. The weight of the animals was monitored biweekly and the overall well-being five times a week to control for adverse toxicity.

Adoptive cell transfer (ACT) experiments

In vivo experiments were performed using antigen specific melanoma cell line B16-OVA that was maintained in culture in RPMI, 10% FBS, 1%PenStrep, 0,4 mg G418 up to 5 passages prior to injection. C57B6 mice were subcutaneously injected with 2×105 cells of B16-OVA cells and tumor growth was monitored daily. 10 days post-injections and once tumors had reached a measurable size, ACT was performed intravenously using 5 × 106 OT1 cells previously activated in the presence or absence of LSD1 inhibitor as previously described. For experiments with Pmel-mice, 3.6 × 105 B16-F10 melanoma cells were inoculated s.c. in 100 µl PBS ten days before cell transfer. On the day before cell transfer, mice were assigned to treatment groups and treated mice were irradiated with 6 Gy. A total of 3 × 105 activated pmel1 T cells were injected i.v. together with 15 µl VV-hgp100 on day 0 and 1.4 × 105 IU recombinant hIL-2 (Miltenyi Biotec) i.p. on days 0, 1, and 2. Tumor size was measured using calipers. Tumors were inspected and measured daily to construct a growth curve using the formula: Tumor volume= length x width2/2, where length represents the largest tumor diameter and width represents the perpendicular tumor diameter. On the day of analysis spleen and tumor were collected from each mouse, disaggregated to single cell suspension, and used for flow cytometry analysis.

CAR T cell transfer experiments

Isolation, generation and transduction of CAR T cells

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from buffy coats obtained from healthy donors (University Hospital Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany – Ethical approval number: 250/20) using Lymphocyte separation medium. For T cell activation, non-tissue culture-treated plates were pre-coated with OKT3 (1 mg/ml) and anti-CD28 (1 mg/ml) monoclonal antibodies (mAb). PBMC were plated in complete medium consisting of CTS OpTmizer T Cell Expansion medium (ThermoFisher, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) supplemented with 2.5% human AB serum, 2 mM glutamine, 1 % pen/strep and with or without 2 mM LSD1, in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C. The day after activation, T cells were treated with recombinant human interleukin-7 (IL-7, 500 U/ml) and -15 (IL-15, 50 U/ml). Activated T cells were transduced on day 3 as described previously with a third generation B7H3-CAR consisting of CD8aStalk.CD8TM.CD28.OX40.zeta-chain (ζ). From day 6 after transduction, CAR-T cells and control T cells were fed with recombinant human IL-2 (100 U/ml) (R&D, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA). Cells were continuously cultured with and without 2 mM LSD1.

Immunophenotype and flow cytometry

Characterization of CAR-T and control T cells was performed by flow cytometry. For analysis of transduction efficiencies, 2 × 105 cells were washed twice with FACS buffer (1x PBS, 0.5 % BSA, and 2 mM EDTA). Cell pellets were resuspended in PE-labeled Protein-L (Sino Biological, Beijing, China) and stained for 40 minutes at room temperature. For staining of surface markers, cells were stained for 20 minutes at 4 °C with following mAb: CD3-PE-Cy7, CD8-APC-Cy7, CD45RO-FITC, CD62L-vioblue (Miltenyi, Bergisch-Gladbach, Germany) and PD1-PerCP Cy5.5 (Biolegend, San Diego, California, USA). For each sample, a minimum of 30,000 events were acquired with FACS Canto II (BD) and analyzed using Flowlogic software (Inivai Technologies, Mentone, Australia).

Co-culture assay

Tumor cells were transduced with a retroviral vector encoding for eGFP (33963009). For co-culture experiments, B7H3-CAR T cells and control T cells either treated with or without LSD1 were cultured with B7H3+ tumor cell lines, SH-SY5Y (neuroblastoma) and D341 (medulloblastoma) in RPMI medium supplemented with 10 % FBS, 2 mM glutamine and 1 % pen/strep in decreasing effector cell to target cell ratio. After 3 days, co-cultures were collected and surface-stained for CD3 and HLA-DR expression. Before analysis via flow cytometer, counting beads (Biolegend, San Diego, California, USA) were added to the samples and a minimum of 5000 counting beads were acquired for sample.

Statistical analysis and data quantification

Flow cytometry data was analyzed using FlowJo v10.2. Results were analyzed and visualized on Prism version 9.2.0 (GraphPad). All statistical analyzes were conducted using GraphPad Prism version 9.2.0. When the data meet the assumption of a parametric test (based on normality test), differences between two groups were calculated by two-tailed Student’s t test. For graphs with multiple comparisons being made, one-way ANOVA was performed with post hoc Sidak’s test or Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons, unless otherwise specified. For data not normally distributed, a non-parametric test was applied. Significance was set at p values ≤ 0.05. For all figures: *, p ≤ 0.05; **, p ≤ 0.01; ***, p ≤ 0.001. All p values are indicated in the figure legend. All plots indicate Min to Max value data and error bars are shown as mean ± SEM. The n numbers for each experiment and the numbers of experiments are annotated in each figure legends. For all experiments, data are reported based on individual biological replicates pooled from multiple donors or animals.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Source data

Acknowledgements

We thank IEO’s Genomic Unit, Flow Cytometry and Imaging Unit at IEO for their technical assistance, Giulia Casorati and Paolo Dellabona for providing the B16-OVA cell line. TM thanks Leonardo and Lara Nezi for their consistent support and helpful discussion. This work was supported by Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca contro il Cancro (AIRC StartUp Grant 21474 to TM, AIRC Bridge 28840 to TM, AIRC IG 24944 to SM, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft 470198222 and DKMS-SLS-JHRG-2021-03 to IC). CC was supported by Fondazione Veronesi’s fellowship. This work was partially supported by the Italian Ministry of Health with Ricerca Corrente and 5 ×1000 funds.

Author contributions

I.P. and T.M. design the study. T.M.F. and C.C. equally contributed to this paper. I.P., T.M.F., C.C., S.T., D.H., J.S., C.H.L., C.B.N.L., M.M., E.P., A.B., E.S. performed the experiments; I.P., T.M.F., C.C., E.C., S.T., D.H., J.S., C.H.L., C.B.N.L., M.M., E.P., A.B., E.S., M.K., L.G., I.C., L.N., and T.M. analyzed the data; M.I., C.M., L.G., I.C., M.K., S.M., and L.N. provided critical expertize and resources; I.P., C.C., and T.M. wrote and edited the manuscript; TM coordinated the whole study. All the authors discussed and read the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Joya Chandra, Byoung S. Kwon and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The RNAseq data generated in this study have been deposited in the GEO database under accession code GSE272770. The RNAseq LSD1 KO publicly available data used in this study are available in the GEO database under accession code GSE147130. The remaining data are available within the Article, Supplementary Information or Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Teresa Maria Frasconi, Carlotta Catozzi.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-024-51500-9.

References

- 1.Kalos, M. et al. T cells with chimeric antigen receptors have potent antitumor effects and can establish memory in patients with advanced leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med3, 1–12 (2011). 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brentjens, R. J. et al. CD19-targeted T cells rapidly induce molecular remissions in adults with chemotherapy-refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med.5, 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005930 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Maude, S. L. et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med.371, 1507–1517 (2014). 10.1056/NEJMoa1407222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rapoport, A. P. et al. NY-ESO-1-specific TCR-engineered T cells mediate sustained antigen-specific antitumor effects in myeloma. Nat. Med21, 914–921 (2015). 10.1038/nm.3910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young, R. M., Engel, N. W., Uslu, U., Wellhausen, N. & June, C. H. Next-generation CAR T-cell therapies. Cancer Discov.12, 1625–1633 (2022). 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-1683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klebanoff, C. A., Gattinoni, L. & Restifo, N. P. Sorting through subsets: which T-cell populations mediate highly effective adoptive immunotherapy? J. Immunother.35, 651–660 (2012). 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31827806e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sukumar, M., Kishton, R. J. & Restifo, N. P. Metabolic reprograming of anti-tumor immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol.46, 14–22 (2017). 10.1016/j.coi.2017.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mondino, A. & Manzo, T. To remember or to forget: the role of good and bad memories in adoptive t cell therapy for tumors. Front Immunol.11, 1–15 (2020). 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McLane, L. M., Abdel-Hakeem, M. S. & Wherry, E. J. CD8 T cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection and cancer. Annu Rev. Immunol.37, 457–495 (2019). 10.1146/annurev-immunol-041015-055318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kishton, R. J., Sukumar, M. & Restifo, N. P. Metabolic regulation of T cell longevity and function in tumor immunotherapy. Cell Metab.26, 94–109 (2017). 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.06.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manzo, T. et al. Accumulation of long-chain fatty acids in the tumor microenvironment drives dysfunction in intrapancreatic cd8+ t cells. J. Exp. Med.217, e20191920 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Nava Lauson, C. B. et al. Linoleic acid potentiates CD8+ T cell metabolic fitness and antitumor immunity. Cell Metab.35, 633–650.e9 (2023). 10.1016/j.cmet.2023.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salas-Benito, D., Berger, T. R. & Maus, M. V. Stalled CARs: Mechanisms of Resistance to CAR T Cell Therapies. Annu Rev. Cancer Biol.7, 23–42 (2023). 10.1146/annurev-cancerbio-061421-012235 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giles, J. R., Globig, A. M., Kaech, S. M. & Wherry, E. J. CD8+ T. cells in the cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity56, 2231–2253 (2023). 10.1016/j.immuni.2023.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hosseini, A. & Minucci, S. A comprehensive review of lysine-specific demethylase 1 and its roles in cancer. Epigenomics9, 1123–1142 (2017). 10.2217/epi-2017-0022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faletti, S. et al. LSD1-directed therapy affects glioblastoma tumorigenicity by deregulating the protective ATF4-dependent integrated stress response. Sci. Transl. Med13, 1–16 (2021). 10.1126/scitranslmed.abf7036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu, Y. et al. LSD1 inhibition sustains T cell invigoration with a durable response to PD-1 blockade. Nat. Commun.12, 1–16 (2021). 10.1038/s41467-021-27179-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tu, W. J. et al. Targeting nuclear lsd1 to reprogram cancer cells and reinvigorate exhausted t cells via a novel LSD1-EOMES Switch. Front Immunol.11, 1–23 (2020). 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheng, W. et al. LSD1 ablation stimulates anti-tumor immunity and enables checkpoint blockade. Cell174, 549–563.e19 (2018). 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qin, Y. et al. Inhibition of histone lysine-specific demethylase 1 elicits breast tumor immunity and enhances antitumor efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade. Oncogene38, 390–405 (2019). 10.1038/s41388-018-0451-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sen, D. R. et al. HHS public access. 354, 1165–1169 (2017).

- 22.Philip, M. et al. Chromatin states define tumour-specific T cell dysfunction and reprogramming. Nature545, 452–456 (2017). 10.1038/nature22367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pauken, K. E. et al. Epigenetic stability of exhausted T cells limits durability of reinvigoration by PD-1 blockade. Science (1979)354, 1160–1165 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gray, S. M., Amezquita, R. A., Guan, T., Kleinstein, S. H. & Kaech, S. M. Polycomb Repressive Complex 2-Mediated Chromatin Repression Guides Effector CD8+ T Cell Terminal Differentiation and Loss of Multipotency. Immunity46, 596–608 (2017). 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Youngblood, B. et al. HHS Public Access. 552, 404–409 (2018).

- 26.Ng, C. et al. The histone chaperone CAF-1 cooperates with the DNA methyltransferases to maintain Cd4 silencing in cytotoxic T cells. 669–683 10.1101/gad.322024.118.6 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Niborski, L. L. et al. epigenetically regulated by Suv39h1 in melanomas. 1–16 (2022) 10.1038/s41467-022-31504-z.

- 28.Pace, L. et al. The epigenetic control of stemness in CD8 + T cell fate commitment. 186, 177–186 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Anderson, K. G., Stromnes, I. M. & Greenberg, P. D. Activity: a case for synergistic therapies. Cancer Cell31, 311–325 (2018). 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gattinoni, L. et al. A human memory T-cell subset with stem cell-like propertiesA analyzed experiments HHS Public Access Author manuscript. Nat. Med17, 1290–1297 (2012). 10.1038/nm.2446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Intlekofer, A. M. et al. Effector and memory CD8+ T cell fate coupled by T-bet and eomesodermin. Nat. Immunol.6, 1236–1244 (2005). 10.1038/ni1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pearce, E. L. et al. Control of effector CD8+ T cell function by the transcription factor eomesodermin. Science (1979)302, 1041–1043 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fang, Y., Liao, G. & Yu, B. LSD1/KDM1A inhibitors in clinical trials: Advances and prospects. J. Hematol. Oncol.12, 1–14 (2019). 10.1186/s13045-019-0811-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Binda, C. et al. Biochemical, structural, and biological evaluation of tranylcypromine derivatives as inhibitors of histone demethylases LSD1 and LSD2. J. Am. Chem. Soc.132, 6827–6833 (2010). 10.1021/ja101557k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ravasio, R. et al. Targeting the scaffolding role of LSD1 (KDM1A) poises acute myeloid leukemia cells for retinoic acid-induced differentiation. Sci. Adv.6, 1–14 (2020). 10.1126/sciadv.aax2746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin, M. D. & Badovinac, V. P. Defining memory CD8 T cell. Front Immunol.9, 1–10 (2018). 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Doering, T. A. et al. Network analysis reveals centrally connected genes and pathways involved in cd8+ t cell exhaustion versus memory. Immunity37, 1130–1144 (2012). 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zaid, A. et al. Chemokine receptor–dependent control of skin tissue–resident memory t cell formation. J. Immunol.199, 2451–2459 (2017). 10.4049/jimmunol.1700571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vianello, P. et al. Discovery of a novel inhibitor of histone lysine-specific demethylase 1a (kdm1a/lsd1) as orally active antitumor agent. J. Med Chem.59, 1501–1517 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Gattinoni, L. et al. Acquisition of full effector function in vitro paradoxically impairs the in vivo antitumor efficacy of adoptively transferred CD8+ T cells. J. Clin. Investig.115, 1616–1626 (2005). 10.1172/JCI24480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Windt, G. J. W. et al. Mitochondrial respiratory capacity is a critical regulator of CD8 + T cell memory development. Immunity36, 68–78 (2012). 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Der Windt, G. J. W. et al. CD8 memory T cells have a bioenergetic advantage that underlies their rapid recall ability. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA110, 14336–14341 (2013). 10.1073/pnas.1221740110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qiu, F. et al. Priming with LSD1 inhibitors promotes the persistence and antitumor effect of adoptively transferred T cells. Nat. Commun.15, 4327 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Greiner, D., Bonaldi, T., Eskeland, R., Ernst, R. & Imhof, A. Identification of a specific inhibitor of the histone methyltransferase SU(VAR)3-9. Nat. Chem. Biol.1, 143–145 (2005). 10.1038/nchembio721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.López-Cobo, S. et al. SUV39H1 ablation enhances long-term CAR T function in solid tumors. Cancer Discov.14, 120–141 (2024). 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-22-1350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jain, N. et al. Disruption of SUV39H1-mediated H3K9 methylation sustains CAR T-cell function. Cancer Discov.14, 142–157 (2024). 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-22-1319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abad, J. D. et al. TCR gene therapy of established tumors. Cytokine31, 1–6 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Overwijk, W. W. et al. Tumor regression and autoimmunity after reversal of a functionally tolerant state of self-reactive CD8+ T cells. J. Exp. Med.198, 569–580 (2003). 10.1084/jem.20030590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Du, H. et al. HHS Public Access. 35, 221–237 (2019).

- 50.Majzner, R. G. et al. CAR T cells targeting B7-H3, a pan-cancer antigen, demonstrate potent preclinical activity against pediatric solid tumors and brain tumors. Clin. Cancer Res.25, 2560–2574 (2019). 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fraietta, J. A. et al. HHS Public Access. 24, 563–571 (2018).

- 52.Kuwahara, M. et al. The transcription factor Sox4 is a downstream target of signaling by the cytokine TGF-β and suppresses T H2 differentiation. Nat. Immunol.13, 778–786 (2012). 10.1038/ni.2362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trinchieri, G. Interleukin-12 and the regulation of innate resistance and adaptive immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol.3, 133–146 (2003). 10.1038/nri1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grasso, C. S. et al. Conserved interferon-γ signaling drives clinical response to immune checkpoint blockade therapy in melanoma. Cancer Cell38, 500–515.e3 (2020). 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hoekstra, M. E. et al. Long-distance modulation of bystander tumor cells by CD8+ T-cell-secreted IFN-γ. Nat. Cancer1, 291–301 (2020). 10.1038/s43018-020-0036-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thibaut, R. et al. Bystander IFN-γ activity promotes widespread and sustained cytokine signaling altering the tumor microenvironment. Nat. Cancer1, 302–314 (2020). 10.1038/s43018-020-0038-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Benci, J. L. et al. Tumor interferon signaling regulates a multigenic resistance program to immune checkpoint blockade. Cell167, 1540–1554.e12 (2016). 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Paschen, A., Melero, I. & Ribas, A. Central role of the antigen-presentation and interferon-γ pathways in resistance to immune checkpoint blockade. Annu Rev. Cancer Biol.6, 85–102 (2022). 10.1146/annurev-cancerbio-070220-111016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jacquelot, N. et al. Predictors of responses to immune checkpoint blockade in advanced melanoma. Nat. Commun.8, 592 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.White, M. G. et al. Short-term treatment with multi-drug regimens combining BRAF/MEK-targeted therapy and immunotherapy results in durable responses in Braf-mutated melanoma. Oncoimmunology10, 1992880 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Irvine, D. J., Maus, M. V., Mooney, D. J. & Wong, W. W. The future of engineered immune cell therapies. Science (1979)378, 853–858 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Finck, A. V., Blanchard, T., Roselle, C. P., Golinelli, G. & June, C. H. Engineered cellular immunotherapies in cancer and beyond. Nat. Med28, 678–689 (2022). 10.1038/s41591-022-01765-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sen, D. R. et al. The epigenetic landscape of T cell exhaustion. Science (1979)354, 1165–1169 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ghoneim, H. E. et al. De novo epigenetic programs inhibit PD-1 blockade-mediated T cell rejuvenation. Cell170, 142–157.e19 (2017). 10.1016/j.cell.2017.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kong, W. et al. BET bromodomain protein inhibition reverses chimeric antigen receptor extinction and reinvigorates exhausted T cells in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J. Clin. Investig.131, 1–16 (2021). 10.1172/JCI145459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics29, 15–21 (2013). 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K. & Shi, W. FeatureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics30, 923–930 (2014). 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Leek, J. T. et al. The sva package for removing batch effects and other unwanted variation in high-throughput experiments. Bioinformatics28, 882–883 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. & Smyth, G. K. edgeR: a bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics26, 139–140 (2009). 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The RNAseq data generated in this study have been deposited in the GEO database under accession code GSE272770. The RNAseq LSD1 KO publicly available data used in this study are available in the GEO database under accession code GSE147130. The remaining data are available within the Article, Supplementary Information or Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.