Abstract

Median arcuate ligament (MAL) syndrome, otherwise known as celiac artery compression syndrome, is rare and is characterized by celiac artery compression by the median arcuate ligament. We report a unique case of MAL syndrome with recurrent myocardial infarction as the primary manifestation, and offer new pathophysiological insights. A man in his early 50s experienced recurrent upper abdominal pain, electrocardiographic changes, and elevated troponin concentrations, which suggested myocardial infarction. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography showed considerable celiac artery stenosis due to MAL syndrome. The patient was diagnosed with MAL syndrome and acute myocardial infarction. He declined revascularization owing to economic constraints, and opted to have conservative treatment with Chinese herbal extracts and medications. He succumbed to sudden cardiac death during a subsequent abdominal pain episode. The findings from this case show that MAL syndrome can present with recurrent myocardial infarction rather than typical intestinal angina symptoms. The pathophysiological link may involve intestinal and cardiac ischemia. An accurate diagnosis and appropriate management of MAL syndrome require careful evaluation and investigation.

Keywords: Myocardial infarction, median arcuate ligament syndrome, case report, abdominal pain, troponin, celiac artery

Introduction

Median arcuate ligament (MAL) syndrome, which is also referred to as celiac artery compression syndrome, is a rare disorder characterized by compression of the celiac artery by the median arcuate ligament. 1 This ligament, formed by the connection of the diaphragmatic crura, creates a fibrous arch anterior to the aorta. We report a unique case of MAL syndrome with recurrent myocardial infarction as the primary manifestation, and offer new pathophysiological insights into this syndrome. This case report adheres to the SCARE criteria. 2 The reporting of this study conforms to the CARE guidelines. 3

Case presentation

A man in his early 50s was admitted to our hospital on 30 October 2018 because of acute inferior, high lateral, and extensive anterior myocardial infarction. The patient had a history of hypertension without prior blood pressure control therapy and had smoked for 5 years (20 cigarettes/day) before quitting 1 year previously. He had been diagnosed with non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction 27 days earlier at a local hospital, and presented with recurrent upper abdominal pain lasting for 2 weeks. This episode of abdominal pain was his first, and it lasted approximately 30 minutes and was considerably alleviated after rest. An electrocardiogram (ECG) conducted at that time showed slight horizontal ST-segment elevation and high T waves in leads V2 to V5 (Figure 1(a)). The patient had no history of diabetes or genetic diseases in the family. The patient’s son signed a consent form for treatment.

Figure 1.

(a) In column 1, 12-lead electrocardiography (ECG) shows slight horizontal ST-segment elevation and high T waves in leads V2 to V5 on 3 October 2018. In column 2, 12-lead ECG shows restoration of the ST segment to baseline and a slight reduction in T wave amplitude in leads V2 to V5 on 4 October 2018. In column 3, 18-lead ECG shows ST segment elevation in leads I, II, aVL, aVF, V2 to V6, and V3R to V5R on 30 October 2018. In column 4 (5 minutes after the ECG shown in column 3), the ST segment has returned to baseline and the patient’s pain has spontaneously subsided. In column 5 (2 hours after the ECG shown in column 3), the ECG is normal. In column 6, 18-lead ECG remains normal on 31 October 2018. In column 7, an 18-lead ECG is normal at admission on 30 November 2018. In column 8, ECG shows complete atrioventricular conduction block and a ventricular escape rhythm after resuscitation on 30 November 2018 and (b) ECG after resuscitation on 30 November 2018 shows complete atrioventricular conduction block and a ventricular escape rhythm in lead II.

Creatinine kinase-MB (CKMB) and troponin concentrations were within the normal range upon admission to our hospital. A physical examination showed a normal body temperature (36.4°C), blood pressure (130/70 mmHg), and heart rate (60 beats/minute). However, CKMB and troponin concentrations greatly increased several hours later (CKMB concentration: 9.45 ng/mL, normal range: 0–6.36 ng/ml; troponin I concentration: 18.55 ng/mL, normal range: 0–0.3 ng/mL). The ECG showed minimal changes compared with the initial ECG, except for the restoration of the ST segment to baseline and a slight reduction in T wave amplitude in leads V2 to V5 (Figure 1(a)). Additional laboratory tests showed slight liver dysfunction (aspartate transaminase concentration: 47 U/L, normal range: 8–40 U/L), an elevated white blood cell count (13.9 × 109/L, normal range: 3.5–9.5 × 109/L), and an increased neutrophil percentage (76.5%, normal range: 50%–70%). No signs of dyslipidemia or diabetes mellitus were observed. Liver function, renal function, thyroid function, and concentrations of brain natriuretic peptide, carcinoembryonic antigen, alpha fetoprotein, D-dimer, and procalcitonin were within the normal range. Human immunodeficiency virus antibody, hepatitis markers, and syphilis antibody tests were negative. No abnormalities were detected in computed tomography (CT) scans of the abdomen, pelvic cavity, and chest. Echocardiography showed normal findings. Coronary angiography performed at the local hospital showed no marked luminal stenosis or coronary spasm (Figure 2).

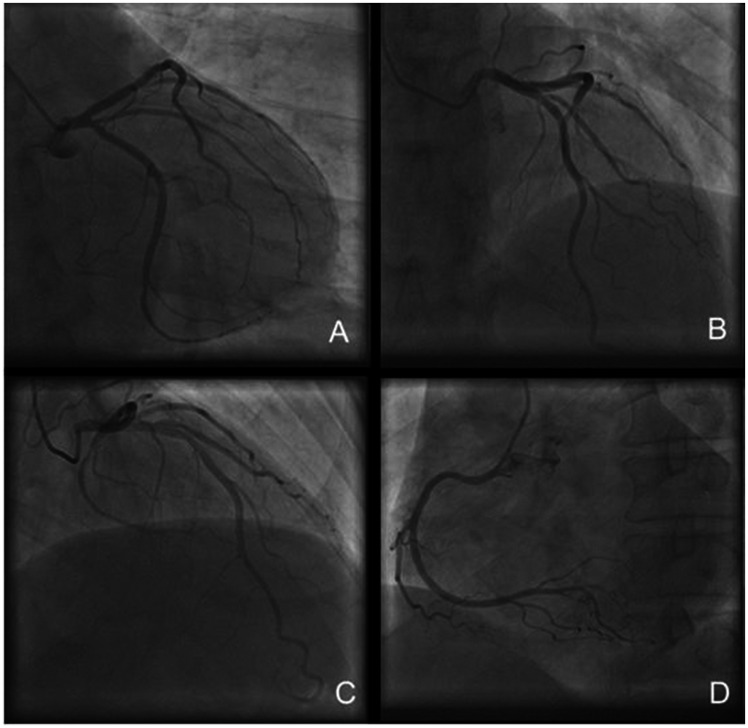

Figure 2.

Coronary angiography shows the left circumflex artery (LCX), left anterior descending artery (LAD), and right coronary artery (RCA). (a) The right anterior oblique (RAO) view at 30° shows the LCX. (b) The left anterior oblique (LAO) view at 45° combined with the cranial (CRA) view at 30° shows the LAD. (c) The anteroposterior (AP) view + CRA 30° shows the LAD and (d) LAO 45°shows the RCA.

When the patient was first diagnosed with non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction in a local hospital, he was treated with dual anti-platelet therapy, a beta blocker, losartan potassium, isosorbide mononitrate, pantoprazole, and hydrotalcite, and discharged 7 days later. After discharge, he still suffered from recurrent epigastric pain, and each time it lasted for less than 30 minutes. The colic pain was localized in the upper abdomen without radiation and usually occurred in the morning when he was brushing his teeth or in the evening after a meal. The colic epigastric pain occurred more frequently in the 2 days before he was admitted to our hospital. The patient visited our Emergency Department because of epigastric pain in the morning of 30 October 2018. An 18-lead ECG conducted in the Emergency Department showed ST segment elevation in leads I, II, aVL, aVF, V2 to V6, and V3R to V5R (Figure 1(a)), with a heart rate of 68 beats/minute and a blood pressure of 105/63 mmHg. Within 5 minutes, the ST segment had returned to baseline, and the pain spontaneously subsided (Figure 1(a)). Upon an examination in our department, the patient had a normal blood pressure (116/92 mmHg), respiratory rate (20 breaths/minute), heart rate (61 beats/minute), oxygen saturation (98%), and body temperature (36.9°C). There were no signs of disorientation or paralysis, and no heart murmurs were auscultated. An abdominal palpation showed no abnormalities. Laboratory tests showed a white blood cell count of 7.7 × 109/L, hemoglobin concentration of 142 g/L, platelet count of 230 × 109/L, activated partial thromboplastin time of 28.3 s, prothrombin time of 11.3 s, and normal fasting blood glucose concentration, BNP concentration, electrolytes, liver function, renal function, and urine tests. The troponin concentration measured 1 hour after the pain episode was slightly elevated (51 ng/L, normal range: 0–50 ng/L), while the subsequent ECG was normal (Figure 1(a)). Echocardiography showed a slightly enlarged left atrium (35 mm) without other abnormalities, with an ejection fraction of 62% and normal contractility.

An 18-lead ECG repeated the next day remained normal (Figure 1(a)). The patient was diagnosed with acute myocardial infarction according to the criteria outlined in the universal definitions of myocardial injury and myocardial infarction updated in 2018 by the European Society of Cardiology. 4 A contrast-enhanced CT scan showed severe stenosis of the celiac artery, with no stenosis observed in the inferior mesenteric artery (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Computed tomographic scanning with contrast enhancement shows severe stenosis of the celiac artery. Arrows in panels a and b show the median arcuate ligament and compressed celiac artery. Arrows in panels c and d show the compressed celiac artery.

We advised the patient to address the celiac stenosis through percutaneous angioplasty of the celiac trunk with stent implantation in the Interventional Radiology Department or through laparoscopic procedures in the Vascular Surgery Department. However, he declined these recommendations because of economic constraints. The patient opted for treatment with Chinese herbal extracts, dual antiplatelet drugs, atorvastatin, diltiazem, alprostadil, and isosorbide mononitrate instead. No pain occurred during hospitalization, and the patient was discharged from our department 7 days later with these medications with no symptoms.

The patient experienced nausea and vomiting after dinner on 29 November 2018, followed by severe epigastric pain and loss of consciousness. Limb movement with dysphonia resumed after 20 minutes, and the patient gradually recovered over several hours. He was readmitted to the Cardiothoracic Surgery Department at our hospital on the morning of 30 November 2018. Upon admission, the patient was conscious and able to answer questions accurately, with no signs of disorientation or paralysis. A physical examination showed a normal blood pressure (131/74 mmHg), heart rate (70 beats/minute), and oxygen saturation (98%). Laboratory testing showed an elevated white cell count (11.4 × 109/L) and neutrophil count (9.42 × 109/L, normal range: 1.8–7.5 × 109/L), as well as an elevated neutrophil percentage (82.6%, normal range: 50%–70%), while the hemoglobin concentration (135 g/L) and platelet count (203 × 109/L) were within normal limits. The activated partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time, electrolyte levels, and renal function were also normal. Liver function tests showed a slightly elevated aspartate transaminase concentration (49 U/L). An 18-lead ECG was normal upon admission (Figure 1(a)), and echocardiography and CT scans of the abdomen, pelvic cavity, and chest were unremarkable. The patient was treated with alprostadil, simvastatin, diltiazem, and enoxaparin sodium.

The patient complained of epigastric pain again 30 minutes after dinner on 30 November 2018. His blood pressure was 135/70 mmHg, heart rate was 78 beats/minute, and oxygen saturation was 98%. Shortly after dinner, he complained of chest pain and immediately lost consciousness, and his blood pressure dropped to 100/55 mmHg. Telemetry showed ventricular fibrillation, which promptly resulted in cardiopulmonary resuscitation and electrical defibrillation. Intravenous epinephrine was administered. After restoration of his heart rhythm, an ECG showed complete atrioventricular conduction block and a ventricular escape rhythm (Figure 1(a), (b)). An ultrasound examination showed no fluid in the pericardial, abdominal, or pelvic cavity. Despite continuous cardiopulmonary resuscitation for more than an hour, the patient succumbed to the event.

Discussion

MAL syndrome is a rare disorder characterized by compression of the celiac artery by the median arcuate ligament. 1 Anatomically, compression of the celiac artery by the median arcuate ligament is believed to lead to intermittent mesenteric ischemia. However, because of the presence of a patent collateral circulation between the celiac artery and the superior mesenteric artery, some patients may remain asymptomatic for an extended period. 5 Nevertheless, in certain cases, MAL syndrome presents with a constellation of symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, epigastric pain, postprandial pain, and weight loss. This diagnostic ambiguity results in MAL syndrome primarily being a diagnosis of exclusion, posing challenges in diagnostic workup. In our case of MAL syndrome, recurrent myocardial infarction emerged as the primary manifestation. This case contributes novel insights into MAL syndrome’s pathophysiology, enriching our understanding and potentially guiding future research directions.

Smoking can trigger symptoms such as chest tightness, chest pain, and abdominal pain6,7 and it is an important risk factor for conditions, such as coronary artery spasm and gastrointestinal spasm.6,8 Our patient had ceased smoking in the year preceding the onset of symptoms. Despite the occurrence of pain, coronary angiography conducted at the local hospital showed no evidence of coronary spasm. Clinical presentation of Takotsubo syndrome often mimics acute coronary syndrome, making differentiation challenging. According to a clinical score developed by Ghadri et al., 9 points are assigned as follows: female sex (25 points), emotional trigger (24 points), physical trigger (13 points), absence of ST-segment depression (except in lead aVR) (12 points), psychiatric disorders (11 points), neurological disorders (9 points), and QTc prolongation (6 points), with a cut-off value of 40 points. When we took into consideration the patient’s medical history, the clinical score was only 6 points, making the diagnosis of Takotsubo syndrome highly unlikely.

Lipshutz first reported anatomical compression of the celiac artery in 1917. 10 As a clinical entity, MAL syndrome was first described by Harolja in 1963, 11 with Dunbar et al. presenting the first clinical study on this entity in 1965. 12 Despite ongoing controversies regarding the etiology, pathophysiology, treatment, and prognosis of MAL, MAL can be diagnosed through various imaging methods, such as duplex scanning, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and contrast aortography.13,14 With the increasing use of these diagnostic modalities, more cases of MAL are being reported, contributing to a better understanding of this disease. In many reported cases, intestinal angina caused by reduced blood flow in the celiac artery has been a common and notable symptom. However, whether ischemia of the celiac artery truly induces angina is unclear. We present a rare case of MAL with recurrent myocardial infarction as the main manifestation during each episode, which may provide a new perspective on the pathophysiology of MAL.

In our case, the patient complained of upper abdominal pain on each occasion, but simultaneous ECG and troponin measurements consistently indicated myocardial infarction. On the basis of the patient’s primary complaint of upper abdominal pain, often occurring in the morning during teeth brushing or in the evening after meals, we performed contrast-enhanced CT to assess the possibility of celiac artery and mesenteric artery ischemia. CT showed considerable stenosis of the celiac artery due to MAL syndrome. During hospitalization, ECG changes sometimes rapidly resolved, resembling Prinzmetal’s angina. In addition, coronary artery angiography showed no fixed stenosis, suggesting that myocardial infarction was induced by coronary artery spasm. In the patient’s initial hospitalization in our facility, an ECG displayed simultaneous ST-segment elevation in inferior, high lateral, extensive anterior, and right ventricular leads, suggesting myocardial infarction caused by coronary artery hypoperfusion due to hypotension. However, this possibility was ruled out because the patient’s blood pressure was within the normal range during at least two episodes of upper abdominal pain. We consider that substances released into the bloodstream during intestinal angina likely triggered actual angina in the heart.

The exact pathophysiological mechanism underlying MAL syndrome remains unclear. Two theories of the pathophysiological mechanism of MAL syndrome have been proposed. The first theory posits that compression of the mesenteric artery leads to mesenteric ischemia, either directly or indirectly, via a “steal phenomenon” facilitated by collaterals connecting the superior mesenteric and celiac arteries. 15 The second neurogenic theory suggests the involvement of the celiac ganglion and plexus, leading to subsequent stimulation and splanchnic vasoconstriction. 16 Hamaoka et al. reported a unique case of intestinal angina with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, which suggested that hemodynamic changes could affect intestinal perfusion even in the presence of mild stenosis of the celiac and mesenteric arteries. 17 In our case, intestinal ischemia may have led to severe cardiac ischemia, suggesting a potential vicious circle between these two phenomena. Therefore, reduced blood flow or nerve dysfunction may induce abnormal splanchnic vasoconstriction, resulting in ischemia affecting multiple organs and leading to serious outcomes.

As a complication, MAL syndrome plays a major role in the development of celiac trunk stenosis or obstruction, which can alter hemodynamic flow and potentially lead to complications such as splanchnic artery aneurysms, with a propensity to rupture.18,19 However, we do not believe that the patient’s death was due to celiac artery rupture because ultrasound after resuscitation showed no evidence of fluid in the abdominal or pelvic cavity. Our patient succumbed to sudden cardiac death resulting from MAL syndrome. Notably, no major collateral circulation between the celiac artery and the superior mesenteric artery was observed in contrast-enhanced CT scans, which may explain the severity of each attack in our patient. Careful clinical history-taking and thorough investigations are essential for an accurate diagnosis and treatment of MAL syndrome because this syndrome can manifest as myocardial infarction.

To alleviate compression of the celiac artery, various medical treatments have been used. Surgical division of the MAL is considered the first-line therapy because of its recognized safety profile and low recurrence rate of symptoms.20,21 Alternatively, bypass surgery between the abdominal aorta and external celiac artery offers another option for revascularization of the stenosis. 22 However, because compression of the celiac trunk is predominantly physical rather than due to intravascular lesions such as atherosclerosis, percutaneous balloon angioplasty or stent implantation is often considered unfeasible because of the high rates of restenosis, stent dislocation, and thrombosis.13,15,23,24 Laparoscopic procedures may reduce surgical trauma and the duration of hospitalization, and enhance surgical safety compared with traditional open surgery, and ultrasound may be used to confirm the patency of the celiac trunk.25–27 Hybrid procedures combining various methods are also under investigation and follow-up to achieve an improved prognosis.28,29

Overall, the technical success rate of endovascular mesenteric revascularization ranges from 85% to 100%, while the technical success rate of surgical revascularization ranges from 97% to 100%. 14 The optimal therapeutic approach for an individual patient should take into account factors, such as age, etiology, symptoms, extent of stenosis, collateral circulation, and physical condition. Unfortunately, our patient did not follow our advice regarding revascularization during the initial consultation, which may have helped prevent his death.

Conclusion

This case highlights the potential for MAL syndrome to present atypically with recurrent myocardial infarction as the predominant manifestation rather than the more typical gastrointestinal symptoms. The underlying pathophysiology of MAL syndrome likely involves a complex interplay between mesenteric and cardiac ischemia, in which the lack of a collateral circulation may exacerbate this condition. While various revascularization options are available, the optimal treatment approach should be individualized. A prompt diagnosis and appropriate management are crucial to prevent life-threatening complications of MAL syndrome, as shown by the fatal outcome in this patient who declined the recommended interventions.

Acknowledgements

We thank International Science Editing (http://www.internationalscienceediting.com) for editing this manuscript. We also extend our gratitude to Professor Li Hongjian of the Heart Center of the Fifth Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University for providing English guidance on this case report.

Author contributions: All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, and/or the analysis and interpretation of the data for this work. In addition, all authors participated in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content and provided final approval of the version to be submitted and any revised version.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

ORCID iD: Xiaoyong Hu https://orcid.org/0009-0006-8917-3793

Data availability statement

All of the patient’s details have been deidentified.

Ethics statement

The case report was approved for publication by the Ethics Committee of Taihe Hospital, Shiyan. The patient’s son and the patient signed a consent form for the release of medical records for publication.

References

- 1.Santos GM, Viarengo LMA, Oliveira MDP. Celiac Artery Compression Syndrome. J Vasc Bras 2019; 18: e20180094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sohrabi C, Mathew G, Maria N, Collaborators et al. The SCARE 2023 guideline: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int J Surg 2023; 109: 1136–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gagnier JJ, Kienle G, Altman DG, CARE Group et al. The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development. Headache 2013; 53: 1541–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. ; Executive Group on behalf of the Joint European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA)/World Heart Federation (WHF) Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Circulation 2018; 138: e618–e651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heo S, Kim HJ, Kim B, et al. Clinical impact of collateral circulation in patients with median arcuate ligament syndrome. Diagn Interv Radiol 2018; 24: 181–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiang D, Kleber FX. Smoking and hyperlipidemia are important risk factors for coronary artery spasm. Chinese Med J-Peking 2003; 116: 510–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lundström O, Manjer J, Ohlsson B. Smoking is associated with several functional gastrointestinal symptoms. Scand J Gastroenterol 2016; 51: 914–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim SY, Han SH, Kim KH, et al. Gastric ischemia after epinephrine injection in a patient with liver cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19: 411–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghadri JR, Cammann VL, Jurisic S, InterTAK co-investigators et al. A novel clinical score (InterTAK Diagnostic Score) to differentiate takotsubo syndrome from acute coronary syndrome: results from the International Takotsubo Registry. Eur J Heart Fail 2016; 19: 1036–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lipshutz B. A composite study of the coeliac axis artery. Ann Surg 1917; 65: 159–169. doi: 10.1097/00000658-191702000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harjola PT. A rare obstruction of the coeliac artery. Report of a case. Annales Chirurgiae et Gynaecologiae Fenniae 1963; 52: 547–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunbar JD, Molnar W, Beman FF, et al. Compression of the celiac trunk and abdominal angina. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 1965; 95: 731–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun Z, Zhang D, Xu G, et al. Laparoscopic treatment of median arcuate ligament syndrome. Intractable Rare Dis Res 2019; 8: 108–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Dijk LJ, Van Noord D, De Vries AC, et al. Clinical management of chronic mesenteric ischemia. United European Gastroenterol J 2019; 7: 179–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mak GZ, Speaker C, Anderson K, et al. Median Arcuate Ligament Syndrome in the Pediatric Population. J Pediatr Surg 2013; 48: 2261–2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skeik N, Cooper LT, Duncan AA, et al. Median arcuate ligament syndrome: a nonvascular, vascular diagnosis. Vasc Endovascular Surg 2011; 45: 433–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamaoka T, Omi W, Sekiguti Y, et al. Intestinal angina in a patient with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2016; 10: 271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chivot C, Rebibo L, Robert B, et al. Ruptured pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysms associated with celiac stenosis caused by the median arcuate ligament: a poorly known etiology of acute abdominal pain. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2016; 51: 295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nasr LA, Faraj WG, Al-Kutoubi A, et al. Median arcuate ligament syndrome: a single-center experience with 23 patients. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2017; 40: 664–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khrucharoen U, Juo YY, Sanaiha Y, et al. Factors Associated with Symptomology of Celiac Artery Compression and Outcomes Following Median Arcuate Ligament Release. Ann Vasc Surg 2019; 62: 248–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duran M, Simon F, Ertas N, et al. Open vascular treatment of median arcuate ligament syndrome. BMC Surg 2017; 17: 95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tochikubo A, Abe S, Yamakawa T, et al. A Single Retrograde Revascularization onto the Superior Mesenteric Artery Using an Artificial Graft for Abdominal Angina: A Case Report. Ann Vasc Dis 2018; 11: 120–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grotemeyer D, Duran M, Iskandar F, et al. Median arcuate ligament syndrome: vascular surgical therapy and follow-up of 18 patients. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2009; 394: 1085–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pillai AK, Kalva SP, Hsu SL, et al. ; Society of Interventional Radiology Standards of Practice Committee. Quality improvement guidelines for mesenteric angioplasty and stent placement for the treatment of chronic mesenteric ischemia. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2018; 29: 642–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cienfuegos JA, Estévez MG, Ruiz-Canela M, et al. Laparoscopic treatment of median arcuate ligament syndrome: analysis of long-term outcomes and predictive factors. J Gastrointest Surg 2018; 22: 713–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.San Norberto EM, Romero A, Fidalgo-Domingos LA, et al. Laparoscopic treatment of median arcuate ligament syndrome: a systematic review. Int Angiol 2019; 38: 474–483. DOI: 10.23736/S0392-9590.19.04161-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sahm M, Otto R, Pross M, et al. Laparoscopic therapy of the coeliac artery compression syndrome: a critical analysis of the current standard procedure. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2020; 102: 104–109. DOI: 10.1308/rcsann.2019.0121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garriboli L, Miccoli T, Damoli I, et al. Hybrid Laparoscopic and Endovascular Treatment for Median Arcuate Ligament Syndrome (MALS): Case Report and Review of Literature. Ann Vasc Surg 2020; 63: 457.e7–457.e11. DOI: 10.1016/j.avsg.2019.08.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Michalik M, Dowgiałło-Wnukiewicz N, Lech P, et al. Hybrid (laparoscopy + stent) treatment of celiac trunk compression syndrome (Dunbar syndrome, median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS). Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne 2016; 11: 236–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All of the patient’s details have been deidentified.