Abstract

Background

Acute kidney injury (AKI) significantly increases morbidity and mortality following cardiac surgery, especially in patients with pre-existing renal impairments. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) is a marker of cardiac stress and dysfunction, conditions often exacerbated during cardiac surgery and prevalent in chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients. Elevated NT-proBNP levels can indicate underlying cardiac strain, hemodynamic instability and volume overload. This study evaluated the association between perioperative changes in NT-proBNP levels and the incidence of AKI in this particular patient group.

Methods

This retrospective study involved patients with impaired renal function (eGFR 15–60 ml/min/1.73 m²) who underwent cardiac surgery from July to December 2022. It analyzed the association between the ratio of preoperative and ICU admittance post-surgery NT-proBNP levels and the development of AKI and AKI stage 2–3, based on KDIGO criteria, using multivariate logistic regression models. Restricted cubic spline analysis assessed non-linear associations between NT-proBNP and endpoints. Subgroup analysis was performed to assess the heterogeneity of the association between NT-proBNP and endpoints in subgroups.

Results

Among the 199 participants, 116 developed postoperative AKI and 16 required renal replacement therapy. Patients with AKI showed significantly higher postoperative NT-proBNP levels compared to those without AKI. Decreased baseline eGFR and increased post/preoperative NT-proBNP ratios were associated with higher AKI risk. Specifically, the highest quantile post/preoperative NT-proBNP ratio indicated an approximately seven-fold increase in AKI risk and a ninefold increase in AKI stage 2–3 risk compared to the lowest quantile. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve for predicting AKI and AKI stage 2–3 using NT-proBNP were 0.63 and 0.71, respectively, demonstrating moderate accuracy. Subgroup analysis demonstrated that the positive association between endpoints and logarithmic transformed post/preoperative NT-proBNP levels was consistently robust in subgroup analyses stratified by age, sex, surgery, CPB application, hypertension, diabetes status and fluid balance.

Conclusion

Perioperative NT-proBNP level changes are predictive of postoperative AKI in patients with pre-existing renal deficiencies undergoing cardiac surgery, aiding in risk assessment and patient management.

Keywords: Acute kidney Injury, Cardiac surgery, NT-proBNP, Risk factors

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) following cardiac surgery represents a significant complication that escalates morbidity and mortality among patients [1, 2]. Despite advancements in surgical techniques and patient care, the incidence of AKI remains high, particularly among individuals with pre-existing renal impairment [3]. The capability to precisely predict postoperative AKI and its severity could guide preventive strategies and patient management, potentially improving outcomes [4, 5].

Recent research has underscored the significance of biomarkers in the early prediction of AKI. Among these, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) has emerged as a promising indicator.

NT-proBNP is a fragment of the prohormone BNP (B-type natriuretic peptide), which is released by the heart in response to cardiac stress and dysfunction. Both NT-proBNP and BNP are used clinically to diagnose and manage heart failure, as they reflect similar pathophysiological processes. However, NT-proBNP has a longer half-life and is more stable in the bloodstream, making it a more reliable marker for assessing cardiac function [6]. Traditionally associated with cardiac function, NT-proBNP’s elevation has been correlated with renal outcomes as well. Elevated preoperative NT-proBNP levels have been linked with an increased risk of developing postoperative AKI. This correlation between NT-proBNP concentrations and the risk of any-stage AKI, as well as severe AKI following cardiac procedures, supports its utility as a predictive marker [7, 8].

In another study, Patel et al. demonstrated that higher preoperative brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels significantly predict the risk of AKI after cardiac surgery. The study suggested that incorporating BNP levels into preoperative evaluations could improve risk stratification and outcomes for patients undergoing cardiac surgery [9]. Fiorentino et al. demonstrated that while NT-proBNP alone may not significantly predict AKI recovery, its combination with other biomarkers like plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) improves predictive accuracy [10].

While existing research predominantly focuses on the relationship between preoperative levels of BNP and postoperative AKI, the dynamics of postoperative BNP elevations remain critically underexplored. In addition, patients with impaired kidney function tend to have elevated preoperative BNP [11]. Therefore, in this specific population, it is difficult to draw effective conclusions only by measuring BNP before surgery. An increase in BNP levels following cardiac surgery may reflect augmented cardiac volume stress [12], which could indirectly impact renal function and promote the onset of AKI. Furthermore, monitoring perioperative BNP elevation could offer a novel approach for early identification of patients at elevated risk, enabling timely interventions aimed at mitigating the incidence and severity of AKI. In view of the stability of the prediction effect of NT-proBNP on cardiac function, investigating the association between perioperative elevations in NT-proBNP and the development of AKI holds significant promise for enhancing patient management and outcomes following cardiac procedures.

This study seek to bridge this knowledge gap by evaluating the association between postoperative increases in NT-proBNP and the emergence of AKI in a specific patient cohort - those with impaired preoperative renal function, for developing AKI and more severe stages of the condition following cardiac surgery.

Methods

Patients and inclusion/exclusion criteria

This research focused on adult individuals who had reduced preoperative kidney function (eGFR between 15 and 60 ml/min/1.73 m²) and who underwent valve, coronary artery bypass, or combined procedures at our facility from July to December 2022. Excluded were those previously on renal replacement therapy (RRT) or with a transplant, those meeting the KDIGO criteria [13] for preoperative acute kidney injury, those with incomplete health records, those who died within 48 h post-ICU, and those undergoing urgent surgery. The study received approval from the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Zhongshan Hospital (Approval Number B2021–873R), and all participants provided written consent.

Design

This retrospective analysis involved gathering clinical information from electronic health records, covering (1) demographic information: age, gender, body mass index (BMI), and comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus. (2) laboratory results: including preoperative and postoperative levels of NT-proBNP, (3) surgical details: type of surgery (valve, CABG, or combined), duration of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), and other intraoperative variables. (4) postoperative outcomes: central venous pressure (CVP) upon admission of intensive care unit (ICU), fluid balance, incidence and severity of AKI based on KDIGO criteria, RRT, length of hospital stay, and in-hospital mortality.

Rationale of perioperative care

We used an electronic ICU medical record system that dynamically monitored and followed up on renal function and urine output. This system included automated tracking and alerts for changes in key indicators such as serum creatinine levels and urine output.

Following surgery, SCr was tracked daily in the ICU, with kidney function assessments performed for the first three days after leaving the ICU and then every other day until hospital discharge.

At our institution, NT-proBNP measurement is routinely performed for all hospitalized patients, regardless of their department. This standard practice ensures that comprehensive cardiac monitoring is maintained across all patient populations. Consequently, the perioperative NT-proBNP measurements used in this study were part of the routine clinical care, reinforcing the retrospective nature of the study. The rationale for the blood tests is that blood samples were collected upon ICU admittance and every 24 h postoperatively until the patients were discharged from the ICU. The consistent monitoring typically continued for 3 to 7 days, depending on the patient’s clinical condition and recovery progress.

Definitions

The primary outcome of the study was the incidence of post-surgery AKI, defined by the KDIGO guidelines [13], which include both serum creatinine and urine output measurements. Participants were divided into two groups according to whether they developed AKI after their operation.

The primary exposure of interest in this study was the perioperative change in NT-proBNP levels, defined as the ratio of the last NT-proBNP level before surgery (usually the morning of the surgery day) to the NT-proBNP level upon admission to the ICU after surgery. This ratio was calculated for each patient and used to assess the association between perioperative NT-proBNP changes and the incidence of postoperative AKI. The NT-proBNP ratio was logarithmically transformed for statistical analysis to normalize its distribution.

The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) formula [14] based on the last serum creatinine (SCr) level measured before surgery.

Fluid Balance (FB) was based on detailed records of fluid intake and output were collected for the first 48 h postoperatively or until the diagnosis of AKI, whichever came first. This included intraoperative fluid administration, postoperative fluid management, and daily fluid balance.

|

In the subgroup analysis, we categorized patients into volume overload (≥ 5%) and non-overload (< 5%) groups based on fluid balance (FB). This classification was derived from previous study [15].

Statistical analysis

Data analysis utilized R software, version 4.3.0. Data following a normal distribution were presented as mean ± standard deviation, while those not normally distributed were shown as medians with interquartile ranges. Categorical data were expressed as frequencies and percentages. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test checked for normality and homogeneity of variances. Continuous data differences were assessed using the Student’s t-test or nonparametric equivalents, and categorical data differences were analyzed using Fisher’s exact or chi-square tests. For data not normally distributed, logarithmic (lg) transformed was applied before analysis. To explore the nonlinear association between perioperative change of NT-proBNP and postoperative AKI using restricted cubic splines (RCS) in the context of a clinical study, while adjusting for age, gender, CPB time, surgical type, pre-existing hypertension/diabetes mellitus, preoperative hemoglobin and albumin. Univariate logistic regression identified potential risk factors for postoperative AKI, calculating odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Multivariate analysis, employing stepwise forward selection, was applied to variables with P-values less than 0.05, considered predictive of postoperative AKI. To ensure the reliability of our regression analysis, we assessed multicollinearity among the explanatory variables. We calculated the variance inflation factors (VIFs) for each variable included in the model. A VIF value greater than 10 was considered indicative of significant multicollinearity and the variable was excluded from the regression [16]. Additionally, we performed trend analysis to evaluate the trending association between NT-proBNP quartiles and the endpoints. The optimal cutoff values for biomarkers in predicting the primary outcome were determined by maximizing the Youden index. Subgroup analyses were conducted to explore the associations between NT-proBNP classified with the optimal cut-off and outcomes among individuals of different sexes, ages, surgery, diabetes status, and hypertension status. Interaction tests determine the consistency of these associations across the various subgroups. A P-value of less than 0.05 was set as the threshold for statistical significance.

Results

Basic characteristics

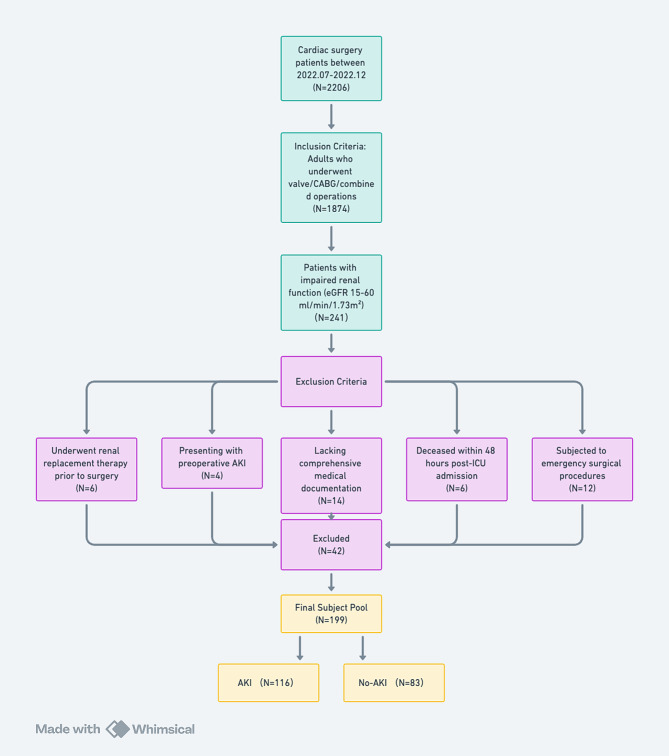

A total of 199 eligible patients were enrolled to this study (Fig. 1) and 116 patients (58.3%) developed AKI after cardiac surgery. RRT was performed in 16 patients. The AKI group had higher postoperative NT-proBNP levels (2973.00 vs. 1110.00 pg/mL, P < 0.001), lower albumin levels (38.84 ± 3.33 vs. 40.92 ± 4.03 g/L, P < 0.001), higher serum creatinine levels (142.54 ± 44.04 vs. 126.54 ± 37.46 µmol/L, P = 0.006), and lower eGFR (45.39 ± 10.85vs. 50.04 ± 10.13 ml/min/1.73 m², P = 0.003). Additionally, postoperative cTnT and CK-MB levels were higher in the AKI group (0.73 vs. 0.31 µg/L, P < 0.001 and 29.50 vs. 20.00 U/L, P = 0.001, respectively), and the length of hospital stay was longer (16.50 vs. 15.00 days, P = 0.017) (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the patients enrollment

Table 1.

Perioperative characteristics of the Study Population

| Characteristics | Total (n = 199) |

No-AKI (n = 83) |

AKI (n = 116) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | ||||

| Male (%) | 130 (65.33) | 51 (61.45) | 79 (68.10) | 0.331 |

| Age (years) | 66.69 ± 9.72 | 66.92 ± 9.07 | 66.53 ± 10.20 | 0.781 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.50 ± 3.49 | 24.16 ± 3.51 | 24.74 ± 3.47 | 0.245 |

| Preoperative context | ||||

| Hypertension (%) | 138 (69.35) | 57 (68.67) | 81 (69.83) | 0.892 |

| DM (%) | 41 (20.60) | 14 (16.87) | 27 (23.28) | 0.270 |

| Baseline laboratory indices | ||||

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 128.80 ± 17.86 | 131.52 ± 16.86 | 126.85 ± 18.37 | 0.069 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 39.68 ± 3.76 | 40.92 ± 4.03 | 38.84 ± 3.33 | < 0.001 |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 9.65 ± 5.18 | 9.34 ± 6.17 | 9.86 ± 4.39 | 0.496 |

| Serum creatinine (µmol/L) | 135.87 ± 42.07 | 126.54 ± 37.46 | 142.54 ± 44.04 | 0.006 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73m2) | 47.33 ± 10.78 | 50.04 ± 10.13 | 45.39 ± 10.85 | 0.003 |

| Uric acid (µmol/L) | 491.87 ± 260.58 | 472.68 ± 159.28 | 505.61 ± 313.63 | 0.381 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 984.40 (403.70, 2383.00) | 778.70 (348.75, 2182.50) | 1155.00 (458.15, 2952.75) | 0.076 |

| cTnT (ug/L) | 0.02 (0.01, 0.05) | 0.02 (0.01, 0.04) | 0.03 (0.02, 0.06) | 0.026 |

| CK-MB (U/L) | 11.00 (9.00, 14.00) | 12.00 (10.00, 14.00) | 11.00 (9.00, 14.00) | 0.027 |

| Surgery | ||||

| Sole Valve (%) | 55 (27.64) | 22 (26.51) | 33 (28.45) | 0.888 |

| Sole CABG (%) | 118 (59.30) | 52 (62.65) | 66 (56.90) | 0.067 |

| Valve & CABG (%) | 26 (13.07) | 9 (10.84) | 17 (14.66) | 0.133 |

| CPB duration (mins) | 114.77 ± 37.06 | 106.38 ± 37.48 | 120.15 ± 36.12 | 0.091 |

| Postoperative laboratory indices | ||||

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 2180.00 (857.50, 4802.50) | 1110.00 (541.10, 2737.00) | 2973.00 (1396.75, 7034.75) | < 0.001 |

| cTnT (ug/L) | 0.50 (0.20, 1.19) | 0.31 (0.14, 0.60) | 0.73 (0.30, 1.39) | < 0.001 |

| CK-MB (U/L) | 25.00 (15.00, 48.00) | 20.00 (12.50, 36.00) | 29.50 (17.00, 55.25) | 0.001 |

| Postoperative indices | ||||

| CVP upon admission of ICU | 8 (7,10) | 8 (6,10) | 8 (7,10) | 0.592 |

| FB (%) | 3.09 ± 1.16 | 2.99 ± 1.12 | 3.24 ± 1.20 | 0.129 |

| Prognosis | ||||

| In-hospital mortality (%) | 6 (3.02) | 0 (0.00) | 6 (5.17) | 0.092 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 16.00 (12.00, 23.00) | 15.00 (11.00, 18.00) | 16.50 (12.00, 25.25) | 0.017 |

AKI: Acute kidney injury; BMI: Body Mass Index; BUN: Blood Urea Nitrogen; CABG: Coronary artery bypass grafting; CK-MB: Creatine kinase MB; CPB: Cardiopulmonary bypass; cTnT: Cardiac troponin T; CVP: Central Venous Pressure; DM: Diabetes mellitus; eGFR: Estimated glomerular filtration rate, calculated by CKD-EPI formulae; FB: Fluid balance; ICU: intensive care unit; NT-proBNP: N terminal pro B type natriuretic peptide

The values are expressed as the median (IQR) and mean ± SD or number (%)

P- values are the results of unpaired t-test or Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables, and χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables

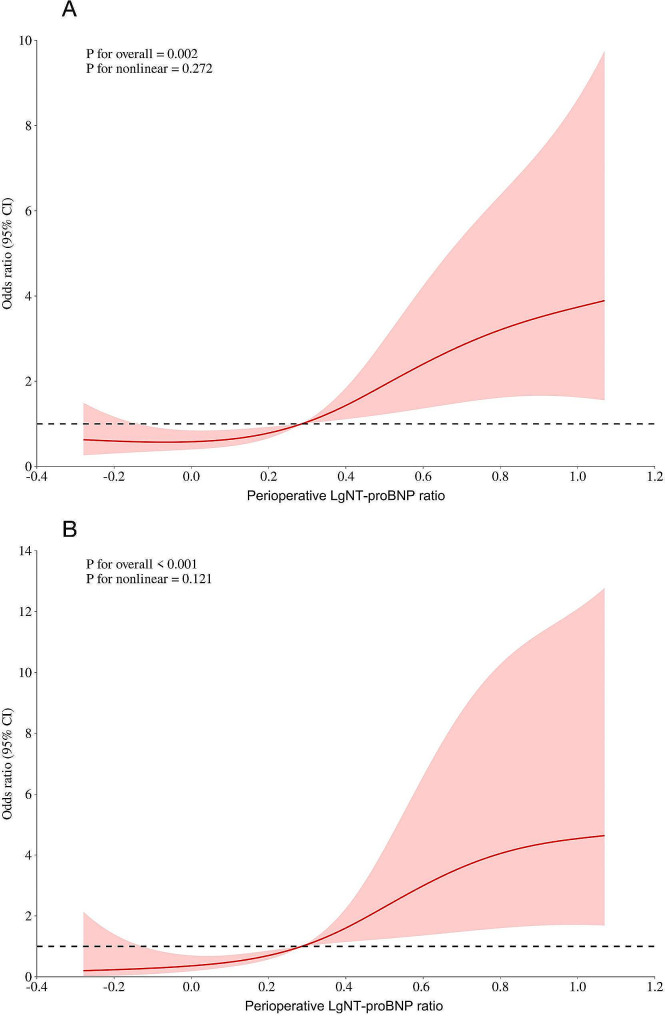

Nonlinear association analysis

The RCS curve analysis was applied to identify potential nonlinear association between logarithmic transformed NT-proBNP and AKI (Fig. 2A)/AKI stages 2–3 (Fig. 2B). However, the statistical test for nonlinearity did not reach significance (P for nonlinear = 0.272 and 0.121), indicating that the relationship between LgNT-proBNP and AKI/AKI stages 2–3 can be adequately described by logistic models in this study.

Fig. 2.

Potential nonlinear relationship between logarithmic transformed NT-proBNP and AKI

Association between perioperative NT-proBNP change and AKI

Because NT-proBNP in our study was not normally distributed, we performed logarithmic transformations of NT-proBNP and classified them according to their logarithmic quartiles: Q1[-0.701,0.0176), Q2[0.0176,0.282), Q3[0.282,0.629) and Q4[0.629,2.14]. In the logistic regression analysis for risk factors of AKI (Table 2), significant predictors in the multivariate analysis included baseline albumin (OR: 0.84, p = 0.018) and logarithmic transformed Post/Preoperative NT-proBNP levels in the highest quantile (OR: 6.68, p = 0.017). Trend analysis indicated that the risk of AKI increased with higher NT-proBNP levels (P for trend = 0.007). Gender, age, fluid balance, and other comorbidities like hypertension and diabetes mellitus were not statistically significant risk factors. Notably, elevated levels of logarithmic transformed Post/Preoperative cTnT and CK-MB were associated with an increased risk of AKI in univariate analysis but did not retain significance in the multivariate model. Figure 3 A showed that logarithmic transformed Post/Preoperative NT-proBNP levels significantly excelled with an AUROC of 0.63 (95%CI 0.552–0.708) for prediction of all stages AKI, indicating moderate predictive accuracy. The optimal cut-off point was determined to be 0.31, with a sensitivity of 57.8% and a specificity of 67.5%.

Table 2.

Logistic regression of risk factors for AKI

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Gender | 1.34 | 0.74 ∼ 2.42 | 0.331 | |||

| Age | 1.00 | 0.97 ∼ 1.03 | 0.780 | |||

| Hypertension | 1.06 | 0.57 ∼ 1.94 | 0.862 | |||

| Diabetes Mellitus | 1.50 | 0.73 ∼ 3.07 | 0.272 | |||

| Baseline laboratory indices | ||||||

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73m2) | 0.96 | 0.93 ∼ 0.99 | 0.003 | 0.98 | 0.91 ∼ 1.03 | 0.213 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 0.99 | 0.97 ∼ 1.00 | 0.071 | 0.99 | 0.96 ∼ 1.02 | 0.554 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 0.85 | 0.78 ∼ 0.93 | < 0.001 | 0.84 | 0.72 ∼ 0.97 | 0.018 |

| Valve & CABG | 1.49 | 0.61 ∼ 3.61 | 0.379 | |||

| CPB duration (mins) | 1.01 | 1.00 ∼ 1.02 | 0.094 | 1.01 | 1.00 ∼ 1.03 | 0.168 |

| FB (%) | 0.83 | 0.65 ∼ 1.06 | 0.130 | |||

| LgPost/Preop cTnT Quantile | ||||||

| Q1 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| Q2 | 0.82 | 0.37 ∼ 1.80 | 0.615 | 1.26 | 0.51 ∼ 3.13 | 0.621 |

| Q3 | 1.51 | 0.68 ∼ 3.34 | 0.313 | 1.73 | 0.66 ∼ 4.53 | 0.264 |

| Q4 | 2.37 | 1.04 ∼ 5.44 | 0.041 | 2.59 | 0.88 ∼ 7.57 | 0.083 |

| LgPost/Preop CK-MB Quantile | ||||||

| Q1 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| Q2 | 1.44 | 0.65 ∼ 3.18) | 0.368 | 1.33 | 0.54 ∼ 3.25 | 0.536 |

| Q3 | 1.91 | 0.86 ∼ 4.23) | 0.111 | 1.15 | 0.44 ∼ 3.04 | 0.777 |

| Q4 | 4.03 | 1.71 ∼ 9.49) | 0.001 | 2.01 | 0.70 ∼ 5.78 | 0.197 |

| LgPost/Preop NT-proBNP Quantile | ||||||

| Q1 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| Q2 | 1.33 | 0.60 ∼ 2.92 | 0.485 | 1.50 | 0.46 ∼ 4.85 | 0.5 |

| Q3 | 2.26 | 1.01 ∼ 5.05 | 0.046 | 3.50 | 0.96 ∼ 12.76 | 0.058 |

| Q4 | 3.62 | 1.56 ∼ 8.42 | 0.003 | 6.68 | 1.41 ∼ 31.69 | 0.017 |

| P for trend | 0.001 | 0.007 | ||||

AKI: Acute kidney injury; BMI: Body Mass Index; BUN: Blood Urea Nitrogen; CABG: Coronary artery bypass grafting; CK-MB: Creatine kinase MB; CPB: Cardiopulmonary bypass; cTnT: Cardiac troponin T; DM: Diabetes mellitus; eGFR: Estimated glomerular filtration rate, calculated by CKD-EPI formulae; FB: Fluid balance; ICU: intensive care unit; NT-proBNP: N terminal pro B type natriuretic peptide

Fig. 3.

Receiver Operating Characteristic curves for the prediction of all stage AKI and AKI Stage 2–3 based on perioperative NT-proBNP ratio

For AKI stages 2–3, baseline albumin levels (OR:0.83, p < 0.001), the third (OR:7.70, p = 0.003) and highest quantiles of logarithmic transformed post/preoperative NT-proBNP (OR:9.38, p = 0.001) were significant risk factors in the multivariate analysis (Table 3). Trend analysis indicated that the risk of AKI increased with higher NT-proBNP levels (P for trend < 0.001). Other factors like age, gender, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and CPB duration did not show significant associations. This highlighted the importance of monitoring preoperative albumin and perioperative NT-proBNP levels in predicting severe AKI post-operation. Figure 3B demonstrated the predictive accuracy for AKI stage 2–3, with logarithmic transformed Post/Preoperative NT-proBNP achieving an AUROC of 0.714 (95%CI 0.63–0.798), showcasing good predictive ability. Logarithmic transformed Post/Preoperative NT-proBNP = 0.365 was the best cut-off point, with a sensitivity of 75%, a specificity of 65.2%.

Table 3.

Logistic regression of risk factors for AKI stage 2–3

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Gender | 0.58 | 0.28 ∼ 1.17 | 0.127 | |||

| Age | 1.02 | 0.98 ∼ 1.06 | 0.340 | |||

| Hypertension | 0.90 | 0.43 ∼ 1.89 | 0.777 | |||

| Diabetes Mellitus | 1.63 | 0.73 ∼ 3.63 | 0.231 | |||

| Baseline laboratory indices | ||||||

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73m2) | 0.97 | 0.94 ∼ 1.00 | 0.095 | 0.97 | 0.94 ∼ 1.01 | 0.119 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 0.98 | 0.96 ∼ 0.99 | 0.029 | 0.98 | 0.96 ∼ 1.01 | 0.218 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 0.86 | 0.78 ∼ 0.95 | 0.003 | 0.83 | 0.74 ∼ 0.92 | < 0.001 |

| Valve & CABG | 1.70 | 0.63 ∼ 4.56 | 0.291 | |||

| CPB duration (mins) | 1.01 | 0.99 ∼ 1.02 | 0.297 | |||

| FB | 1.05 | 0.78 ∼ 1.41 | 0.771 | |||

| LgPost/Pre-op cTnT Quantile | ||||||

| Q1 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| Q2 | 0.70 | 0.21 ∼ 2.37 | 0.564 | 0.83 | 0.21 ∼ 3.21 | 0.783 |

| Q3 | 1.94 | 0.69 ∼ 5.43 | 0.207 | 2.24 | 0.65 ∼ 7.70 | 0.203 |

| Q4 | 2.89 | 1.07 ∼ 7.82 | 0.037 | 2.11 | 0.58 ∼ 7.64 | 0.257 |

| LgPost/Pre-op CK-MB Quantile | ||||||

| Q1 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| Q2 | 0.48 | 0.11 ∼ 2.03 | 0.317 | 0.34 | 0.07 ∼ 1.58 | 0.167 |

| Q3 | 2.07 | 0.70 ∼ 6.12 | 0.189 | 1.06 | 0.29 ∼ 3.83 | 0.926 |

| Q4 | 4.89 | 1.76 ∼ 13.61 | 0.002 | 2.49 | 0.72 ∼ 8.66 | 0.150 |

| LgPost/Pre-op NT-proBNP Quantile | ||||||

| Q1 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| Q2 | 2.19 | 0.51 ∼ 9.28 | 0.289 | 2.00 | 0.46 ∼ 8.80 | 0.358 |

| Q3 | 6.71 | 1.80 ∼ 25.00 | 0.005 | 7.70 | 2.00 ∼ 29.68 | 0.003 |

| Q4 | 7.37 | 1.99 ∼ 27.32 | 0.003 | 9.38 | 2.43 ∼ 36.25 | 0.001 |

| P for trend | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

AKI: Acute kidney injury; BMI: Body Mass Index; BUN: Blood Urea Nitrogen; CABG: Coronary artery bypass grafting; CK-MB: Creatine kinase MB; CPB: Cardiopulmonary bypass; cTnT: Cardiac troponin T; DM: Diabetes mellitus; eGFR: Estimated glomerular filtration rate, calculated by CKD-EPI formulae; FB: Fluid balance; ICU: intensive care unit; NT-proBNP: N terminal pro B type natriuretic peptide

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis was performed to elucidate the heterogeneity of the association between NT-proBNP and endpoints in subgroups. No significant differences were observed between endpoints and logarithmic transformed Post/Preoperative NT-proBNP levels classified with optimal cut-off points (P for interaction > 0.05, Tables 4 and 5). Specifically, the results demonstrated that the positive association between endpoints and logarithmic transformed Post/Preoperative NT-proBNP levels was consistently robust in subgroup analyses stratified by age, sex, surgery, CPB application, hypertension, diabetes status and fluid balance.

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis of the association between AKI and perioperative NT-proBNP change classified with optimal cut-off point

| Variables | n (%) | logarithmic transformed Post/Pre-op NT-proBNP < 0.31 | logarithmic transformed Post/Pre-op NT-proBNP ≥ 0.31 | OR (95%CI) | P | P for interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 199 (100.00) | 49/105 | 67/94 | 3.62 (1.91 ∼ 6.86) | < 0.001 | |

| Gender | 0.442 | |||||

| Female | 69 (34.67) | 12/32 | 25/37 | 5.67 (1.68 ∼ 19.13) | 0.005 | |

| Male | 130 (65.33) | 37/73 | 42/57 | 3.00 (1.39 ∼ 6.49) | 0.005 | |

| Surgery type | 0.699 | |||||

| Valve | 55 (27.64) | 17/35 | 16/20 | 4.60 (1.23 ∼ 17.13) | 0.023 | |

| CABG | 118 (59.30) | 25/56 | 41/62 | 3.70 (1.58 ∼ 8.68) | 0.003 | |

| Valve & CABG | 26 (13.07) | 7/14 | 10/12 | 4.16 (0.56 ∼ 31.25) | 0.165 | |

| CPB application | 0.497 | |||||

| No | 112 (56.28) | 24/53 | 39/59 | 3.50 (1.44 ∼ 8.46) | 0.006 | |

| Yes | 87 (43.72) | 25/52 | 28/35 | 4.86 (1.74 ∼ 13.61) | 0.003 | |

| Hypertension | 0.687 | |||||

| No | 61 (30.65) | 17/35 | 18/26 | 4.16 (1.16 ∼ 14.88) | 0.029 | |

| Yes | 138 (69.35) | 32/70 | 49/68 | 3.82 (1.78 ∼ 8.21) | < 0.001 | |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 0.081 | |||||

| No | 158 (79.40) | 38/81 | 51/77 | 2.85 (1.41 ∼ 5.74) | 0.003 | |

| Yes | 41 (20.60) | 11/24 | 16/17 | 22.21 (2.33 ∼ 211.80) | 0.007 | |

| Age | 0.312 | |||||

| <60yrs | 42 (21.11) | 16/28 | 10/14 | 1.84 (0.41 ∼ 8.25) | 0.427 | |

| ≥60yrs | 157 (78.89) | 33/77 | 57/80 | 4.51 (2.16 ∼ 9.44) | < 0.001 | |

| FB | 0.789 | |||||

| < 5 | 189 (94.98) | 47/99 | 65/90 | 2.88 (1.57–5.28) | 0.001 | |

| ≥ 5 | 10 (5.02) | 2/6 | 2/4 | 2.00 (0.15–26.73) | 0.6 |

AKI: Acute kidney injury; CABG: Coronary artery bypass grafting; CPB: Cardiopulmonary bypass; FB: Fluid balance; NT-proBNP: N terminal pro B type natriuretic peptide.OR: Odds Ratio, CI: Confidence Interval

Table 5.

Subgroup analysis of the association between AKI stage 2–3 and perioperative NT-proBNP change classified with optimal cut-off point

| Variables | n (%) | logarithmic transformed Post/Pre-op NT-proBNP < 0.365 | logarithmic transformed Post/Pre-op NT-proBNP ≥ 0.365 | OR (95%CI) | P | P for interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 199 (100.00) | 9/105 | 31/94 | 6.31 (2.68 ∼ 14.84) | < 0.001 | |

| Gender | 0.911 | |||||

| Female | 69 (34.67) | 4/32 | 14/37 | 20.41 (3.23 ∼ 129.10) | 0.001 | |

| Male | 130 (65.33) | 5/73 | 17/57 | 6.94 (2.21 ∼ 21.85) | < 0.001 | |

| Surgery type | 0.868 | |||||

| Valve | 55 (27.64) | 4/35 | 8/20 | 5.73 (1.36 ∼ 24.07) | 0.017 | |

| CABG | 118 (59.30) | 3/56 | 18/62 | 8.23 (2.14 ∼ 31.67) | 0.002 | |

| Valve & CABG | 26 (13.07) | 2/14 | 5/12 | 6.39 (0.44 ∼ 92.24) | 0.173 | |

| CPB application | 0.100 | |||||

| No | 112 (56.28) | 6/53 | 16/59 | 3.60 (1.14 ∼ 11.37) | 0.029 | |

| Yes | 87 (43.72) | 3/52 | 15/35 | 22.83 (4.51 ∼ 115.60) | < 0.001 | |

| Hypertension | 0.201 | |||||

| No | 61 (30.65) | 2/35 | 11/26 | 21.57 (3.29 ∼ 141.34) | 0.001 | |

| Yes | 138 (69.35) | 7/70 | 20/68 | 4.23 (1.57 ∼ 11.39) | 0.004 | |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 0.474 | |||||

| No | 158 (79.40) | 5/81 | 24/77 | 8.20 (2.82 ∼ 23.85) | < 0.001 | |

| Yes | 41 (20.60) | 4/24 | 7/17 | 8.18 (1.08 ∼ 62.00) | 0.042 | |

| Age | 0.553 | |||||

| <60yrs | 42 (21.11) | 3/28 | 4/14 | 8.91 (0.94 ∼ 84.92) | 0.057 | |

| ≥60yrs | 157 (78.89) | 6/77 | 27/80 | 7.47 (2.74 ∼ 20.38) | < 0.001 | |

| FB | 0.144 | |||||

| < 5 | 189 (94.98) | 9/109 (8.3) | 28/80 (35.0) | 5.98 (2.63–13.62) | < 0.001 | |

| ≥ 5 | 10 (5.02) | 2/6 (33.3) | 1/4 (25.0) | 0.67 (0.04–11.29) | 0.779 |

AKI: Acute kidney injury; CABG: Coronary artery bypass grafting; CPB: Cardiopulmonary bypass; NT-proBNP: N terminal pro B type natriuretic peptide.OR: Odds Ratio, CI: Confidence Interval

Discussion

Advancements in cardiac surgical techniques have enabled an increasing number of patients with pre-existing renal insufficiency to undergo cardiac operations. However, this patient cohort is at heightened risk for developing AKI postoperatively [17], underscoring the imperative for early prediction of AKI risk among these high-risk individuals. In this study, we identified that changes in NT-proBNP levels during the perioperative period can predict the occurrence of AKI and severe AKI. Moreover, we found the optimal cut-off point for prediction of AKI and AKI stage 2–3, and subgroup analysis showed consistency of the association among subgroups. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study addressing the predictive value of the perioperative change of NT-proBNP for cardiac surgery associated AKI .

While prior investigations in general populations have established a correlation between preoperative BNP levels and the incidence of postoperative AKI [7–9], the predictive value of preoperative BNP is compromised in patients with pre-existing renal insufficiency due to inherently elevated BNP levels [18]. Consequently, relying solely on preoperative BNP levels to predict postoperative AKI risk in this specific patient subset presents considerable challenges. The results of the present study underlined the significant role of elevated perioperative NT-proBNP levels in predicting AKI post-cardiac surgery, specifically in patients with compromised preoperative renal function.

In our study, NT-proBNP was not normally distributed; therefore, we performed a base-10 logarithmic transformation and grouped it according to its quartiles. Multivariate regression analysis showed that the highest quartile group, Q4 [0.629, 2.14], was associated with AKI, meaning that when postoperative NT-proBNP increased to 4.26 times the preoperative level, the risk of AKI was 5.68 times higher compared to patients in Q1, whose postoperative NT-proBNP increased to less than 1.04 times the preoperative level or decreased. Simultaneously, Q3 and Q4 were associated with AKI stages 2–3, meaning that when postoperative NT-proBNP increased to 1.91–4.26 times the preoperative level, the risk of AKI stages 2–3 was 6.7 times higher compared to patients in Q1, and when postoperative NT-proBNP increased to 4.26 times the preoperative level, the risk of AKI stages 2–3 was 8.38 times higher compared to patients in Q1.

Our findings showed that the sensitivity and specificity of NT-proBNP for predicting AKI (AUROC 0.63) and AKI stage 2–3 (AUROC 0.714) are moderate. Despite this, NT-proBNP remains valuable in clinical practice for several reasons: Firstly, even with moderate accuracy, NT-proBNP provides significant predictive information, especially in high-risk populations such as those with preoperative renal impairment.

Secondly, our subgroup analysis showed consistent associations between NT-proBNP levels and AKI risk across different patient groups, supporting its reliability as a predictive biomarker. In addition, NT-proBNP should be used alongside other biomarkers and clinical indicators to enhance overall predictive accuracy and provide a comprehensive assessment of AKI risk.

The utility of NT-proBNP measured at ICU admission is supported by its ability to reflect the immediate postoperative state of cardiac stress. For patients who developed AKI shortly after surgery, elevated NT-proBNP levels at ICU admission likely indicate early signs of cardiac stress and dysfunction. For those who developed AKI a few days later, NT-proBNP levels at admission may still serve as a indicative reference and provide valuable predictive information, indicating an ongoing risk due to increased cardiac stress and reduced renal clearance capacity [18].

While NT-proBNP is traditionally considered a marker of cardiac stress, it is important to note that elevated NT-proBNP levels can also result from impaired renal clearance due to AKI or CKD [18]. This suggested that NT-proBNP may serve more as an indicator of existing renal dysfunction rather than a direct cause of AKI or solely a marker of increased cardiac stress.

While NT-proBNP is typically associated with volume status, our study found no significant differences in fluid balance and CVP between the AKI and non-AKI groups. This suggested that the predictive value of NT-proBNP for AKI in our cohort may not be solely related to alteration in volume status.

Additionally, subgroup analyses showed that the association between NT-proBNP levels and AKI remained consistent across various subgroups, including those classified by fluid balance. This indicates that BNP’s predictive value for AKI is robust and not significantly influenced by volume status as measured by fluid balance or CVP.

However, while the predictive value of NT-proBNP is clear, our findings also echo the complexity of AKI as a multifactorial condition, particularly within the setting of cardiac surgery. This complexity mandates a multifactorial approach to risk assessment, highlighting the limitations of relying solely on NT-proBNP or any single biomarker for predicting postoperative renal outcomes. This perspective was bolstered by recent discussions in the literature which advocated for the use of multi-biomarker strategies for improving the accuracy and reliability of AKI predictions [19].

Nevertheless, while our study offers significant insights, it is not without limitations. The retrospective design limits our ability to infer causality between elevated NT-proBNP levels and the incidence of AKI. Prospective studies are needed to confirm our findings and establish a temporal relationship between NT-proBNP levels and AKI development. Additionally, our study population, derived from a single center, may limit the generalizability of our findings. The demographic and clinical characteristics specific to our institution may not be representative of other settings, highlighting the need for multicenter studies to validate our results across different populations and healthcare settings.

Additionally, the timing of NT-proBNP measurements in our retrospective study were based on routine clinical practice rather than a predefined protocol. In our hospital, the first postoperative NT-proBNP was measured at the admission to the ICU. This may mainly reflect the intraoperative cardiac function or fluid overload.

Moreover, our study did not account for all possible confounders that could influence NT-proBNP levels, such as intraoperative hemodynamic changes. The impact of these factors on NT-proBNP levels warrants further investigation to elucidate the multifaceted dynamics at play.

Other biomarkers such as serum and urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), urinary kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1), and interleukin-18 (IL-18) are known to have predictive value for AKI [20]. Unfortunately, these biomarkers were not included in our routine diagnostic panel due to national health insurance policies. As these biomarkers are classified as out-of-pocket expenses, not all patients were willing or able to bear these additional costs, limiting their use in our study. As a result, we were unable to compare the predictive value of NT-proBNP with these other biomarkers.

Conclusions

This study highlighted the predictive value of perioperative changes in NT-proBNP levels for AKI and severe AKI in cardiac surgery patients with preoperative renal impairment. NT-proBNP levels, routinely available and indicative of both cardiac stress and renal function, can aid in early identification of high-risk patients.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the contribution of the study personnel from the department of nephrology, cardiac surgery and critical care for persistent contribution to the maintenance of the cardiac surgery database.

Abbreviations

- AKI

Acute Kidney Injury

- BNP

Brain Natriuretic Peptide

- CKD

Chronic Kidney Disease

- CPB

Cardiopulmonary Bypass

- CTnT

Cardiac Troponin T

- eGFR

Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate

- ICU

Intensive Care Unit

- KDIGO

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes

- NT-proBNP

N-terminal pro-B-type Natriuretic Peptide

- RCS

Restricted Cubic Spline

- SCr

Serum Creatinine

Author contributions

JZ, ZL and WJ designed and directed the study, YM and WZ participated in data collection and maintenance, YM, WZ and JZ analyzed the data, YM, WZ and WJ interpreted the results and writing. WJ and ZL participated in reviewing the manuscript, the maintenance of dataset and facilitating the acquisition of data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Nature Science Foundation of China, No. 82102289; Shanghai Federation of Nephrology Project supported by Shanghai ShenKang Hospital Development Center, No. SHDC2202230; Shanghai “science and technology innovation plan " Yangtze River Delta scientific and technological Innovation Community project, No. 21002411500.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethical board from Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University (Approval Number B2021–873R). All participants provided written consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration (WMA Declaration of Helsinki, 2013).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yiting Ma and Jili Zheng contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Hoste EAJ, Kellum JA, Selby NM, Zarbock A, Palevsky PM, Bagshaw SM, Goldstein SL, Cerda J, Chawla LS. Global epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney injury. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018;14(10):607–25. 10.1038/s41581-018-0052-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu J, Jiang W, Shen B, Fang Y, Teng J, Wang Y, Ding X. Acute kidney Injury in Cardiac surgery. Contrib Nephrol. 2018;193:127–36. 10.1159/000484969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pannu N, James M, Hemmelgarn BR, Dong J, Tonelli M, Klarenbach S, Alberta Kidney Disease N. Modification of outcomes after acute kidney injury by the presence of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58(2):206–13. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.01.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harky A, Joshi M, Gupta S, Teoh WY, Gatta F, Snosi M. Acute kidney Injury Associated with Cardiac surgery: a Comprehensive Literature Review. Braz J Cardiovasc Surg. 2020;35(2):211–24. 10.21470/1678-9741-2019-0122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yuan SM. Acute kidney Injury after Cardiac surgery: risk factors and novel biomarkers. Braz J Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;34(3):352–60. 10.21470/1678-9741-2018-0212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishii J. [Clinical utility of NT-proBNP, a new biomarker of cardiac function and heart failure]. Rinsho Byori. 2008;56(4):316–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenberg JH, Parsons M, Zappitelli M, Jia Y, Thiessen-Philbrook HR, Devarajan P, Everett AD, Parikh CR. Cardiac biomarkers for risk stratification of Acute kidney Injury after Pediatric Cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2021;111(1):191–8. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang C, Gao Y, Tian Y, Wang Y, Zhao W, Sessler DI, Jia Y, Ji B, Diao X, Xu X, et al. Prediction of acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery from preoperative N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide. Br J Anaesth. 2021;127(6):862–70. 10.1016/j.bja.2021.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel UD, Garg AX, Krumholz HM, Shlipak MG, Coca SG, Sint K, Thiessen-Philbrook H, Koyner JL, Swaminathan M, Passik CS, et al. Preoperative serum brain natriuretic peptide and risk of acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery. Circulation. 2012;125(11):1347–55. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.029686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiorentino M, Tohme FA, Murugan R, Kellum JA. Plasma biomarkers in Predicting Renal Recovery from Acute kidney Injury in critically ill patients. Blood Purif. 2019;48(3):253–61. 10.1159/000500423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waldum B, Stubnova V, Westheim AS, Omland T, Grundtvig M, Os I. Prognostic utility of B-type natriuretic peptides in patients with heart failure and renal dysfunction. Clin Kidney J. 2013;6(1):55–62. 10.1093/ckj/sfs174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanakis M, Martens T, Muthialu N. Postoperative saline administration following cardiac surgery: impact of high versus low-volume administration on acute kidney injury. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11(Suppl 9):S1150–2. 10.21037/jtd.2019.04.28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kellum JA, Lameire N, Group KAGW. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of acute kidney injury: a KDIGO summary (part 1). Crit Care. 2013;17(1):204. 10.1186/cc11454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–12. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bagshaw SM, Wald R, Barton J, Burns KE, Friedrich JO, House AA, James MT, Levin A, Moist L, Pannu N, et al. Clinical factors associated with initiation of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury-a prospective multicenter observational study. J Crit Care. 2012;27(3):268–75. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2011.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim JH. Multicollinearity and misleading statistical results. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2019;72(6):558–69. 10.4097/kja.19087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang D, Teng J, Luo Z, Ding X, Jiang W. Risk factors and prognosis of Acute kidney Injury after Cardiac surgery in patients with chronic kidney disease. Blood Purif. 2023;52(2):166–73. 10.1159/000526120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vickery S, Price CP, John RI, Abbas NA, Webb MC, Kempson ME, Lamb EJ. B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and amino-terminal proBNP in patients with CKD: relationship to renal function and left ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46(4):610–20. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fan R, Qin W, Zhang H, Guan L, Wang W, Li J, Chen W, Huang F, Zhang H, Chen X. Machine learning in the prediction of cardiac surgery associated acute kidney injury with early postoperative biomarkers. Front Surg. 2023;10:1048431. 10.3389/fsurg.2023.1048431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan D, Zhao L, Peng W, Wu FH, Zhang GB, Yang B, Huo WQ. Value of urine IL-8, NGAL and KIM-1 for the early diagnosis of acute kidney injury in patients with ureteroscopic lithotripsy related urosepsis. Chin J Traumatol. 2022;25(1):27–31. 10.1016/j.cjtee.2021.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.