Abstract

The study of human performance and perception of exertion constitutes a fundamental aspect for monitoring health implications and enhancing training outcomes such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). It involves gaining insights into the varied responses and tolerance levels exhibited by individuals engaging in physical activities. To measure perception of exertion, many tools are available, including the Borg scale. In order to evaluate how the Borg scale is being used during CPR attempts, this integrative review was carried out between October/2020 and December/2023, with searches from PubMed, CINAHL, Web of Science, Embase, PsycINFO and VHL. Full publications relevant to the PICO strategy were included and letters, editorials, abstracts, and unpublished studies were excluded. In total, 34 articles were selected and categorised into three themes: a) CPR performed in different contexts; b) CPR performed in different cycles, positions, and techniques; c) CPR performed with additional technological resources. Because CPR performance is considered a strenuous physical activity, the Borg scale was used in each study to evaluate perception of exertion. The results identified that the Borg scale has been used during CPR in different contexts. It is a quick, low-cost, and easy-to-apply tool that provides important indicators that may affect CPR quality, such as perception of exertion, likely improving performance and potentially increasing the chances of survival.

Introduction

Understanding human performance and the way exertion is perceived, is crucial for monitoring health implications and improving training results. This includes gaining awareness of the diverse responses and tolerance levels displayed by individuals engaging in similar physical activities [1]. In the 1960s, Gunmar Borg developed the Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale [2] to quantify the subjective perception of effort, serving as a tool to measure the difficulty and strenuousness of performing physical activities. This perception is unique to each individual and is influenced by factors such as health status, age, physical and environmental conditions [3]. The scale is based on the idea that an individual’s perception of exertion during exercise is closely linked to their physiological responses such as increased heart and respiratory rate, sweating and muscle fatigue [4]. These responses serve as indicators of the body’s physiological adaptation to the demands of the exercise. The RPE scale (6–20) ranges from six to 20, where six indicates “no exertion” and 20 represents “maximal exertion”. Participants are asked to rate their perceived level of exertion during exercise, with the number on the scale that best represents their perception. This subjective assessment is important as it provides valuable information about an individual’s tolerance, comfort, and overall experience during physical activity. The RPE scale is a low-cost tool, easy to understand and apply, and validated in multiple contexts [3]. Following this, Borg introduced the CR scale (CR10), spanning from 0, 0.5, 1 to 10, serving to evaluate exertion, pain, and dyspnea [1]. Referred to as Borg CR-10, it is also recognised under various names such as Borg Dyspnea scale, Angina scale, Fatigue scale, Anxiety scale, and Pain scale [5,6]. The tool has also been validated in Brazil to assess vocal effort [7]. Subsequently, in 1982, the CentiMax scale (CR100) emerged, encompassing a range from 0 to 100 and functioning as a psychological measure for the assessment of depression [5,8,9].

The perceived exertion enables researchers to understand the impact of work intensity in areas such as emergency care. Interventions such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) require immediate response, with high demands on performance and physical effort. Despite advances in the field of CPR, survival to hospital discharge rates is still low, making cardiac arrest a worldwide health challenge with high rates of morbidity, mortality, and associated costs [10]. According to the American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines, the chances of survival are directly associated with the quality of CPR [11]. It depends, among other factors, on the rescuer’s performance during chest compressions, which is considered a strenuous physical activity, but crucial to establishing coronary perfusion pressure, in an attempt to promote the return of spontaneous circulation [11].

In this context, to bridge the knowledge gap around perception of exertion in relation to CPR quality, this study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of using the Borg scale during CPR performance.

Methods

Integrative review carried out from October 2020 to December 2023, with initial definition of the problem and research focus, comprehensive literature search, evaluation and critical analysis of data, and presentation of results [12]. Search of the published and unpublished literature was performed based on the guiding question “How is the Borg scale being used during cardiopulmonary resuscitation attempts?” Six electronic databases were used to identify eligible studies: PubMed, CINAHL, Web of Science, Embase, PsycINFO and the Virtual Health Library (VHL) portal, using an institutional Virtual Private Network.

Full publications of primary studies relevant to the PICO strategy were included and letters, editorials, abstracts, and unpublished studies were excluded. No time or language limit were established, to avoid compromising the sensitivity of the searches.

During descriptor selection, it was observed that there were no terms directly linked to the Borg scale. Notably, when controlled descriptors were combined without reference to the scale, a substantial decrease in search results was evident. However, incorporating "Borg scale" significantly facilitated the discovery of a more considerable number of relevant studies for this review.

To effectively structure the descriptors, the following PICO strategy (Population, Intervention, Context and Outcome) was used:

P = person of any age performing CPR;

I = Borg scale in the analysis of perceived exertion during simulated or real-life CPR;

C = simulated or real-life cardiorespiratory arrest.

O = perception of exertion

A pre-defined search strategy was used combining Boolean operators ‘AND’ and ‘OR’ with medical search headings and subheadings (e.g. MeSH) when applicable (S1 Appendix).

In order to facilitate the recording and analysis of eligible sources, each identified study from the initial search was collated within a group in EndNote web [13], with any duplicates removed. Subsequently, the search protocol was structured in an Excel spreadsheet to extract the following data: study title, author, year of publication, country, journal, database, objective, method, population, interventions, and results. The data search and extraction process were carried out by three independent reviewers (LT, SHC, RTFR) and conflicts in the analyses were mitigated by the other reviewers. Due to the nature of this review, risk of bias assessment was not performed [14].

Results

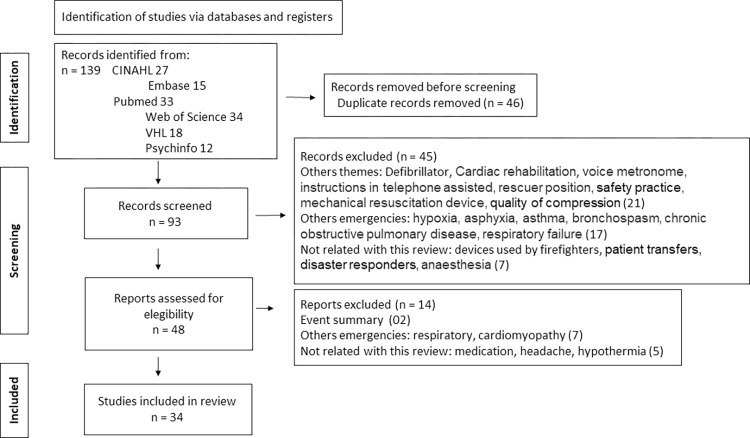

Studies were presented according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) diagram [15], as shown in Fig 1.

Fig 1. PRISMA—Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement.

Of the 139 studies initially identified, 34 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review after full text analysis. The number of included sources according to each database was: eight (23%) in VHL [16–23], six (18%) in CINAHL [24–29], seven (21%) in PubMed [30–36], four (12%) in Embase [37–40] and nine (26%) in Web of Science [41–49]. The year of publication ranged between 2008 and 2023. Country of publication included: Austria [18,20,21,30,32,33,35,41], United States [17,23,24,29,46], Canada [31,42,44], China [16,25,40,49], Japan [34,36], Spain [22,27,47], France [39], United Kingdom [19], Czech Republic [43], Taiwan [26,48], Hungary [28], Korea [37], Saudi Arabia [45] and Brazil [38].

Most studies were randomised crossover studies [16,18,20,24–27,29–31,36,37,39,41–47,49]. Other methods included randomised controlled trials [17,21,23,28,32,33,35,38], non-randomised controlled studies [22,34], and observational studies [19,40,48].

When evaluating perceived exertion with the Borg scale, 22 studies used RPE (6–20) [17,19–24,27,29–34,38,40–43,46,48,49], 11 used CR10 [16,18,25,26,28,35,36,37,39,44,47] and one used CR100 [45]. Due to the heterogeneity of the articles analysed, we classified the studies into three distinct groups: a) CPR performed in different contexts (e.g. simulation, high altitude, microgravity, helicopter) (Table 1); b) CPR performed in different cycles, positions, and techniques (Table 2); c) CPR performed with additional technological resources (e.g. mechanical CPR, metronome, telephone, video) (Table 3).

Table 1. Studies investigating the application of the Borg scale with CPR performed in different contexts.

| Author Country, year | Study type | Sample size | Intervention | Outcome measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Niederer et al. [18] Austria, 2023 |

Randomized crossover | 20 mountaineers | BLS simulation for 16 min at baseline altitude and at high altitude. Borg scale (CR10) |

Vital signs, perception of fatigue. | Significant decrease in oxygen saturation from 97% (SD2%) at baseline to 87% (SD3%) at high altitude (p<0.01). After 16 min of CPR, heart rate had significantly increased [119 bpm (SD 12 bpm) to 124 bpm (95%CI −1.59 to 12.19). No significant difference in perception of fatigue between baseline and high-altitude (2.7 (SD 1.1) vs. 2.6 (SD 0.8), p>0.05). |

| Manoukian et al. [29] USA, 2022 |

Randomized crossover | 3 ALS physicians | CPR in a moving vehicle (3x 2-min stable drive and 3x 2-min dynamic drive). Borg scale (6–20) |

CPR variables and perceived fatigue. |

Stable drive had significantly better CPR score for rate and recoil compared to dynamic drive. There was no significant difference for other measured CPR metrics. Perceived fatigue was greater for dynamic drive (8±1 vs 3.5±1.53) (p = 0.02). |

| Rehnberg et al. [19] United Kingdom, 2011 |

Observational | 21 men | Evetts Russomano (ER) method during CPR in simulated microgravity. Borg scale (6–20) |

Heart rate, perceived exertion rate and arm flexion angle. | Heart rate, perceived exertion, and elbow flexion of both arms increased using the ER method. |

| Barcala-Furelos et al. [22] Spain, 2016 |

Non-randomized controlled | 23 lifeguards | Rescue and CPR on drowning victims, with vs without rescue equipment. Borg scale (6–20) |

Rescue time, quality CPR and perceived exertion. |

Shorter total rescue time with equipment (p <0.001). Increased chest compression rate with rescue tube (p <0.01). Less effort using a rescue board (p <0.001). |

| Asselin et al. [23] USA, 2018 |

Randomized controlled trial | 40 clinicians | 20 teams performed 3 simulations: (baseline; repeat in the same role; repeat in reversed roles). Experimental groups used RTF for simulations 2 and 3. Borg scale (6–20) |

Heart rate, amylase, energy expenditure (NASA-TLX), perceived exertion and CPR quality. | No difference in % heart rate, salivary amylase and NASA-TLX between groups. Reduced levels of physical exertion and perceived workload than control subjects. Positive but limited impact on the quality of CPR performance. |

| Banfai et al. [28] Hungary, 2022 |

Randomized controlled trial | 216 healthcare students | Continuous CPR for 2 minutes, using a surgical vs. fabric mask. Borg scale (CR10) |

Vital parameters and perception of fatigue |

No significant difference in changes in vital parameters and perception of fatigue. |

| Havel et al. [30] Austria, 2011 |

Randomized crossover | 24 certified ALS | ALS in moving ambulance vs flying helicopter. Borg scale (6–20) |

Blood pressure; serum lactate concentrations; Nine Hole Peg Test; perception of exertion | No significant difference in blood pressure, serum lactate and modified Nine Hole Peg Test. Significant reduction on the Borg scale by 0.89 points (95% CI = 0.42–1.350) (p <0.001) with feedback device. |

| Sato et al. [34] Japan, 2018 |

Non-randomized controlled | 24 volunteers | Conventional CPR vs compression only in a hypoxemic environment, simulating high altitudes. Borg scale (6–20) |

Quality CPR and perception of fatigue | Deterioration in performance for compression only CPR. Borg scale after 8 min CPR: greater perceived exertion and fatigue inside the hypobaric chamber and lower outside the chamber (15 ± 2 vs 11 ± 2; p <0.01 in paired t-test). |

| Egger et al. [35] Austria, 2020 |

Randomized controlled trial | 20 climbers | CPR (30:2) in high altitude Borg scale (CR10) |

Quality CPR, heart rate, SpO2 and perceived exertion | Decrease in the mean depth of chest compression (95% CI 0.5 to 1.3; p <0.01), with no difference in compression rate. Increase in heart rate, reduction in SpO2. Increased perception of fatigue after 2 minutes of CPR. |

| Nakashima et al. [36] Japan, 2020 |

Randomized crossover | 45 professionals and medical students | CPR whilst walking alongside a conventional stretcher vs walking alongside a stretcher with support (“wings” method) Borg scale (CR10). |

Quality of the chest compressions and perception of fatigue | Higher average compression rate and depth (p <0.01), with better quality and less perception of fatigue using stretchers with wings. |

| Ahn et al. [37] Korea, 2021 |

Randomized crossover | 30 BLS and ALS providers | 4-min continuous compressions on a mannequin: on a flat floor and 3 types of mattresses (soft, medium, hard). Borg scale (CR10) |

Vital parameters and perception of fatigue |

No significant differences in vital parameters. Perceived exertion was lower when compressions were performed on the floor (p = 0.003) |

| Havel et al. [41] Austria, 2008 |

Randomized crossover | 24 ALS providers | CPR for 8 min in moving ambulance vs flying helicopter. Borg scale (6–20). |

Heart rate to blood pressure ratio; blood pressure, serum lactate, Nine Hole Peg Test, and perceived exertion. | Mean heart rate to blood pressure ratio was smaller (0.89 ± 0.21) in the ambulance compared to (1.01 ± 0.21) in the flying helicopter (p = 0.04). No significant difference in other physiological parameters. Perceived exertion increased in all groups. |

| Pompa et al. [44] Canada, 2019 |

Randomized crossover | 18 clinicians | Conventional CPR vs. Koch compression, in a helicopter. Borg scale (CR10). |

CPR quality and perceived exertion. |

CPR overall quality was 63% in conventional compressions vs 79% with Koch compressions (p = 0.04). Significant reductions in physical exertion for Koch compressions (p < 0.001). |

| Kingston et al. [45] Saudi Arabia, 2021 |

Randomized crossover | 27 ALS providers | Chest compressions for 10 min on a mannequin on concrete and on foam. Borg scale (CR100) |

Heart rate, quality of compressions and perception of fatigue |

No effect on heart rate (p = 0.143). Significant difference (p = 0.019) in compression depth (≥50mm). Perceived fatigue was lower (p <0.001) when CPR was performed on concrete floor. |

Table 2. Studies investigating the use of the Borg scale when CPR is performed in different cycles, positions, and techniques.

| Author Country, year | Study type | Sample size | Intervention | Outcome measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chi et al. [16] China, 2008 |

Randomized crossover | 18 healthcare professionals | 5-min CPR in 3 positions: kneeling, standing next to the manikin on the table and standing next to the manikin on a lower table. Borg scale (CR10). |

Quality CPR and perception of fatigue | No significant difference in quality of CPR (p> 0.05). No significant difference in perceived fatigue between the three positions. |

| Trowbridge et al. [24] USA, 2009 |

Randomized crossover | 20 female lay volunteers | Continuous chest compression vs 30:2 cycle. Borg scale (6–20). |

Compression depth, rate, metabolic fatigue, and perceived exertion at 5 minutes and at the end of CPR | Average depth and rate were significantly lower (p < .004) and (p < 0.001) for continuous CPR. Metabolic fatigue was significantly greater for continuous CPR (p = 0.02). Across both groups, perception of fatigue increased at the end of CPR (p < .001). |

| Chi et al. [25] China, 2010 |

Randomized crossover | 17 professionals | CPR in different cycles: 15:2; 30:2 and 50:5, for 5 min with 50-min rest. Borg scale (CR10) |

Perception of fatigue and discomfort in the body area. | Perception of fatigue was significantly higher (p = .008) in the 50:5 (3.67±2.04) when compared to 15:2 (2.20±1.740) and 30:2 (2.76±1.73). Waist discomfort was noted and was significantly higher in 50:5 (1.83±1.79) when compared to 15:2 (1.40±1.63) and 30:2 (1.56±1.28) (p = .024). |

| Tsou et al. [26] Taiwan, 2022 |

Randomized crossover | 35 nurses | Paediatric chest compressions with one and two hands for 2 minutes. Borg scale (CR10) |

Perception of exertion and pain. | Perceived exertion and pain for one-handed compressions were significantly higher than with two-hands (p< 0.001 and p = 0.004 respectively). |

| Barcala-Furelos [27] Spain, 2022 |

Randomized crossover | 58 lifeguards | Simulated infant CPR in pairs for 20 minutes using two-fingers and two-thumbs technique. Borg scale (6–20) |

Perception of fatigue |

Perception of fatigue is higher in the two-finger technique compared to the two-thumb technique (p = 0.01). |

| Vaillancourt et al. [31] Canada, 2011 |

Randomized crossover | 42 participants ≥55 years old | CPR (30:2 and 15:2) for 5 min and rest for 5 min. Borg scale (6–20) |

Heart rate, blood pressure, venous lactate, and perceived exertion | No significant difference in physiologic measures. Higher level of fatigue using a 30:2 compared to a 15:2 but not statistically significant. |

| Van Tulder et al. [32] Austria, 2014 |

Randomized controlled trial | 26 adults | CPR with dispatcher recommending "compress firmly" vs. "compress as hard as you can", for 10 min. Borg scale (6–20) |

Compression depth and perception of fatigue | Mean compression depth and perception of fatigue were not significantly different between groups (p = 0.66) and (p = 0.89). |

| Skulec et al. [43] Czech Republic, 2016 |

Randomized crossover | Ten volunteers | Continuous CPR vs 30:2 for 30 min. Borg scale (6–20) |

Oxygen consumption and perception of exertion and perception of fatigue | Greater oxygen consumption (p = 0.049) for compressions-only CPR. Higher perceived exertion (p = 0.001) and perceived fatigue (p = 0.058) with compression-only CPR. |

| Marquis et al. [39] France, 2023 |

Randomized crossover | 100 EMS participants | Chest compressions with overlapping or interlocking hands. Borg scale (CR10) |

Overall chest compressions success score, CPR metrics and perception of exertion | Median chest compression score: 79.5% IQR[48.5–94.0] in the overlapping hands group and 71% IQR[38.0–92.8] in the interlocking hands group (p = 0.37). No significant difference for CPR metrics or perception of exertion. |

| Santos-Folgar et al. [47] Spain, 2022 |

Randomized crossover | 21 university students | 2-min standard pediatric CPR vs walking with a dummy on the forearm. Borg scale (CR10) |

CPR quality and perceived exertion | Standard pediatric CPR showed higher overall quality (59% vs 49%; P = 0.02) Ambulating paediatric CPR had a higher perceived exertion (2 vs 5; P< 0.001). |

| Chang et al. [48] Taiwan, 2021 |

Observational | 70 firefighters | 3 CPR tests: (i) uninterrupted for 10 minutes; (ii) after 2 days rest, 5 cycles of 2-min CPR with 10s rest; (iii) after 2 days rest, 5 cycles of 2-min CPR with 20s rest Borg scale (6–20) |

CPR performance and perceived exertion |

No significant differences in compression depth or rate among the three methods (p > 0.05). Perceived exertion during uninterrupted CPR was significantly higher (p < 0.001). |

| Dong et al. [49] China, 2021 |

Randomized crossover | 28 lay people | Hands-only CPR with different rest intervals. Borg scale (6–20). |

Average chest compression depth, vital signs, and perceived fatigue | Significant impact on chest compression depth between different intervals (p = 0.045). No significant difference among all methods in any physiological indicators or in perception of fatigue. |

Table 3. Studies investigating the use of the Borg scale when CPR is performed with additional technological resources.

| Author Country, year | Study type | Sample size | Intervention | Outcome measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barash et al. [17] USA, 2011 |

Randomized controlled trial | 30 BLS/ALS participants | 15 pairs performing simulated CPR, with a change of role (chest compression and AED management), every 2 CPR cycles. With and without automated feedback device. Borg scale (6–20). |

Pre-shock pause time and perceived exertion. | Pre-shock pause time was reduced by 80%, with automated feedback (p<0.0001). No difference in perceived exertion. |

| Fischer et al. [20] Austria, 2012 |

Randomized crossover | 80 medical students | CPR for 12 min with manual mechanical resuscitation device (MRD) vs standard BLS. Borg scale (6–20) |

Heart rate, capillary lactate and perception of exertion |

Heart rate increased in the final minute of standard BLS (p = 0.027). Mean serum lactate concentration decreased with MRD (p≤0.001). Perception of fatigue increased with MRD (p = 0.027). |

| Van Tulder et al. [21] Austria, 2014 |

Randomized controlled trial | 32 volunteers | CPR for 10 min with instructions over the phone with standard wording ("push down firmly 5 cm"), or intensified wording ("it is very important to push down 5 cm every time") Borg scale (6–20). |

Chest compression depth, vital signs reflecting physical strain, perception of fatigue | Compression depth, vital signs and perception of fatigue were not significantly different between groups. |

| Van Tulder et al. [33] Austria, 2015 |

Randomized controlled trial | 36 volunteers | Simulated CPR for 10 min with conventional metronome or continuous voice metronome. Borg scale (6–20). |

CPR quality, heart rate, blood pressure, nine-hole peg test, and perception of fatigue | No significant difference in CPR quality, physiological parameters, and perception of fatigue. |

| Tobase et al. [38] Brazil, 2023 |

Randomized controlled trial | 69 nurses | Simulated BLS with or without feedback device. Borg scale (6–20) |

Heart rate and perceived exertion | Heart rate and perceived exertion were significant lower with feedback device (p<0.001). |

| Li et al. [40] China, 2023 |

Observational | 100 lay adults | 3x 2-min cycles of simulated continuous CPR: without video and with video after 72h rest. Borg scale (6–20) |

CPR metrics and perception of fatigue | Every CPR metric improved significantly with video (all p<0.001). Perception of fatigue significantly increased with video (p< 0.001). |

| Liu et al. [42] Canada, 2016 |

Randomized crossover | 63 participants ≥ 55 years old | 30:2 and continuous CPR for 5 minutes, with a metronome. Borg scale (6–20). |

CPR quality and perception of fatigue | More adequate chest compressions (p = 0.0001) with continuous CPR. No significant difference in perception of fatigue. |

| Manoukian et al. [46] USA, 2022 |

Randomized crossover | 15 firefighters | Manual and mechanical CPR for 2 minutes, on a boat with stable (linear) and dynamic (curved) navigation. Borg scale (6–20) |

Quality of compressions and perception of fatigue | Mechanical CPR favoured the quality of compressions and perception of fatigue (<0.001). |

CPR performed in different contexts

Under this category, 14 studies applied the Borg scale during CPR being performed in different contexts such high altitude [18,34,35], microgravity [19], in the water [22], in helicopter or moving vehicles [29,30,41,44], on different surfaces [36,37,45], wearing face mask [28], and following different protocols [23], as demonstrated in Table 1.

CPR performed in different cycles, positions and techniques

Six studies [24,25,31,43,48,49] used the Borg scale during CPR in different cycles including 15: 2, 30:2, 50:5 and continuous chest compression. Two studies [16,47] applied the Borg scale when investigating CPR being performed in different positions such as kneeling, standing, bending on a low surface, or walking; and four studies applied the tool during different CPR techniques [26,27,32,39], as demonstrated in Table 2.

CPR performed with additional technological resources

In this category, eight studies applied the Borg scale when CPR was provided in combination with mechanical CPR [20,46], phone-assisted CPR [21], with the use of AED [17], teaching video [40] and using feedback devices [33,38,42], as demonstrated in Table 3.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of using the Borg scale during CPR performance in both simulation and real-life contexts. Using the Borg scale during CPR can aid in monitoring and managing the rescuer’s exertion levels, which is crucial for preventing exhaustion and sustaining effective compressions, thus reducing the risk of injuries, and ensuring consistent CPR quality.

It was observed in this review that the Borg scale has been used in several contexts related to CPR to measure the perception of fatigue and/or exertion, with effective contributions to analysis of physical demands. This tool has been applied in other fields [50,51] and demonstrates that, due to the linear relationship between the Borg scale and physiological measures such as oxygen consumption, blood lactate concentration and heart rate during aerobic exercise or strength training, the scale can be a useful tool to monitor exercise intensity, either stationary or dynamic [1,6]. In the field of resuscitation, despite the heterogeneity of the articles included in this review, it has been evidenced that the application of the Borg scale is also beneficial to measure and understand physical demands related to CPR.

It was observed in this review that the Borg scale was applied during cardiac arrest in different scenarios and contexts, including simulation and pre-hospital care, where assistance in challenging environments influences rescuer’s performance during resuscitation [20]. Given the difficulty in carrying out research in real circumstances, a hypobaric chamber was used by Sato et al. (2018) to reproduce the hostile environment at high altitudes. Environments with a lower oxygen concentration require greater effort from the rescuer, negatively influencing the quality of CPR and the chances of survival [34,35]. Additionally, the greater physical and mental stress may result in feelings of fatigue and tiredness. The authors applied the Borg scale to rescuers providing CPR in the hypobaric chamber and scores obtained were higher than those at sea level due to the reduction in SpO2 and rise in heart rate, increasing the perceived exertion. Therefore, to reduce perceived exertion, the authors recommended changing rescuers every two minutes, particularly during CPR with continuous compression, aligning with the current resuscitation guidelines [11]. This is similar to the results from Niederer et al. [18] where mountaineers performed CPR in high altitude. Despite not finding a significant increase in perceived fatigue, physiological parameters such as oxygen saturation and heart rate increased significantly when CPR was performed 3454 meters above sea level. Based on the results, the authors suggest that it is possible to alternate rescuers every one minute in high altitude, where the hypoxic environment and the difficulty in providing CPR can lead to poor performance and physiological fatigue [18,34,35].

Barcala-Furelos and colleagues (2016) explored CPR in the water, evaluating the perception of exertion during compressions on drowning victims. The authors evaluated various rescue equipment to determine the safest option with the shortest rescue time and assessed the impact of these tools on lifeguards’ physiological conditions, perception of exertion and CPR performance. The authors suggest that the use of equipment reduced rescue time, particularly when using a rescue board. Additionally, perception of fatigue was significantly lower with the rescue board when compared to the other tools or without any equipment. However, the authors emphasise that, despite the benefits of using equipment for an improved rescue, there is a need for further training of lifeguards in the use of rescue boards and other tools [22].

In another simulation study exploring cardiac arrest in drowned children [27], lifeguards’ perception of exertion was greater when using the two-finger technique, when compared to the two-thumbs technique. Furthermore, when performing CPR with one-hand and two-hands in older children, the perception of exertion was lower when using both hands, instead of just one [26]. These results are complemented by the study performed by Santos-Folgar (2022) in the infant population. The authors used the Borg scale to evaluate perception of exertion when CPR was provided on an infant supported on the rescuer’s arm. Although it was observed that the quality of compressions was inferior when compared to standard CPR (i.e. infant placed on a hard surface), and the perception of exertion was higher, it is important to consider the need for rapid transport to the emergency department [47].

Performing CPR inside moving vehicles or aircrafts, such as ambulances and helicopters while transporting patients, can be a more complex intervention, which may impact the quality of resuscitation attempts and perception of fatigue [29,30,41,44]. Additional challenges are related to limited space, mobility constraints, vibrations and turbulences, safety concerns, communication difficulties, and equipment stability [52].

Adapting CPR techniques to these unique conditions is crucial, with a primary focus on ensuring the safety of both the patient and the healthcare provider. Interestingly, despite the above-mentioned challenges, a study by Havel et al. (2008) comparing physical effort during CPR performance in an ambulance and helicopter, did not show significant changes in physiological responses. Using the Borg scale (6–20), the authors concluded that the type of transport did not influence physical exertion, however, perception of fatigue increased throughout CPR performance [41], reinforcing the concept of changing rescuers every two minutes for improved performance. In a similar study, Pompa et al. (2019) suggested that changing the way chest compressions are provided is a possible alternative to mitigate the constraints of limited space and mobility [44]. This is also applicable when providing CPR in different positions is required (e.g. performing CPR kneeling, with a manikin on a table, or with overlapping hands) as alternative positions do not influence the perception of exertion, applied force and depth of compression during CPR [16,39]. Furthermore, if it is not possible to perform chest compressions with the hands, using the foot on the sternum can be an effective option, especially when the rescuer has no strength due to exhaustion, or is much smaller than the victim [42]. This is also applicable using the Evetts-Russoman method, where the rescuer’s legs are wrapped around the victim during CPR. Apart from providing adequate compression depth and rate [19], there seems to be a reduced perceived fatigue, potentially improving quality of CPR performance.

Ahn et al. (2021) applied the Borg scale to analyse the influence in quality when CPR is performed on a mattress. Although the authors have not found a significant difference in the quality of chest compressions when compared to CPR delivered on a hard surface, a greater perception of exertion and fatigue was observed [37]. This may be explained by the damping effect of mattress compressibility [53] where the surface may compress under the pressure of chest compressions, making it more difficult to achieve the recommended compression depth. Additionally, the softer surface of a mattress absorbs some of the energy generated during chest compressions, leading to energy dissipation, and reducing the force transmitted to the individual’s chest [54]. Despite not finding a significant difference in CPR performance, the increased perception of exertion can compromise the overall quality and duration of CPR, potentially impacting the patient’s chances of survival.

When comparing continuous compression cycles and standard CPR (e.g. 30:2), it was found that continuous cycles required greater effort, increasing fatigue levels [24]. Similarly, between 15:2 and 30:2 cycles, inadequate chest compressions and greater perception of fatigue were noticed in the latter [27], suggesting that the longer the cycle, the greater energy levels are needed [43], increasing perception of exertion. Chi and colleagues (2010) applied the Borg scale in cycles of 15:2, 30:2 and 50:5, and also concluded that CPR required moderate to heavy exertion progressively, after five minutes of activity [25]. The results of the abovementioned studies support the recommendation that switching rescuers every two minutes or less, improves maintenance of high-quality CPR performance [11]. This is particularly important when CPR is provided by an elderly person or with a slender build, as the constitution of the individual’s physical structure influences CPR performance, recovery time and perception of exertion [24,25,35,48,49]. Additionally, considering the correlation between perceived fatigue and increased heart rate, the application of the Borg scale can also be useful in monitoring CPR performance of individuals who take medications that affect heart rate [4], during prolonged duration of resuscitation attempts [41], for recovery and rehabilitation post-myocardial infarction [55], exertion in patients with pneumopathies [56,57], or long COVID-19 syndrome [58].

Current resuscitation guidelines recommend the use of feedback devices during CPR [11]. The tools provide verbal and/or visual information in real time about the quality and/or metrics of CPR [10] and are believed to reduce perception of exertion during resuscitation attempts [9,17,26,48]. Sound devices such as metronomes are useful in controlling the rhythm and frequency of chest compression [59], while audiovisual devices enable the rescuers to monitor the rhythm, depth, and release of compressions [60,61]. Applying the Borg scale with feedback devices provided additional insights into the rescuer’s perceived exertion levels, helping to ensure that the individual performing CPR can maintain a sustainable level of effort [38]. By combining the data from the feedback device with the subjective assessment provided by the Borg scale, the rescuer can make informed decisions about adjusting their CPR technique or intensity to optimise performance and maintain effective chest compressions. This integrated approach allows for a comprehensive evaluation of both objective and subjective parameters, contributing to enhanced CPR quality and potentially improving patient outcomes.

In addition to feedback devices, other technological resources such as mechanical resuscitation devices, remote guidance over the phone, or video-instruction have also been utilised during resuscitation attempts [20,21,32,33,40]. Although CPR performance may improve with the use of technological resources, when the Borg scale was applied in these circumstances, there were inconsistent conclusions regarding perception of exertion, with one study finding a significant difference when video-CPR was used [40], and others not finding statistically significant results [20,21,32,33]. Moreover, it was observed that quality of CPR performance may be negatively impacted, particularly when feedback devices are used in conjunction with telephone-assisted CPR [33]. Therefore, despite resuscitation guidelines encouraging the use of telephone guidance during CPR, especially for lay people [11], it is important to consider the individual’s profile and ability to understand the guidance and avoid the concomitant use of feedback device.

This review has highlighted the benefit of using the Borg scale to assess the level of exertion during CPR. Although it has been previously evidenced that there are different tools to analyse perception of exertion during physical activities, each offering unique approaches and insights (e.g. Visual Analogue scale, Likert scales) [1], the Borg scale is relatively easy to understand and apply, making it accessible for individuals of different educational backgrounds and age groups. For its straightforward nature that facilitates quick and accurate self-assessment of exertion levels during physical activities, the Borg scale has been recommended by several institutions such as the AHA [11], American College of Sports Medicine [62], and British Association for Cardiac Prevention and Rehabilitation [63].

It is important to recognise that, prior to application of the Borg scale, it is recommended that the tool and instructions on its criteria are presented in advance, so that users (adults or children) can familiarise themselves with its use and correct application [1,64].

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, the results of the included articles were obtained in a simulated environment, using a mannequin. CPR in a real situation can have other effects on the quality of performance and perception of exertion, possibly influenced by a higher level of stress. Second, potential biases were not systematically addressed like in a systematic review. Third, the heterogeneity among study design, population, outcome measures and Borg scale selected, may impact the interpretation and synthesis of the results. Fourth, it is important that the Borg scale be presented to the participants beforehand, in order to understand the respective scoring criteria and values, so that the response is as accurate as possible. However, not all studies described this particularity. Finally, the Hawthorne effect could have impacted the accuracy of results.

Conclusion

The Borg scale was applied in different CPR contexts to analyse the rescuer’s perception of exertion during CPR performance. Identifying the factors that influence quality of performance such as perception of exertion and fatigue, can potentially contribute to enhancing CPR quality, inform resuscitation guidelines, and ultimately improve patient outcomes.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability

The article does not report further data.

Funding Statement

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Williams N. The Borg rating of perceived exertion (RPE) scale, occupational medicine. Occupational Medicine. 2017;67(5): 404–5. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqx063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marques Junior NK. “State of the art” of subjective perceived exertion scales. 2013; 7(39):293–308. Available from: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/4923514.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cabral LL, Lopes PB, Wolf R, Stefanello JMF, Pereira G. A systematic review of cross-cultural adaptation and validation of Borg’s rating of perceived exertion scale. J. Phys. Education. 2017; 28: e2853. 10.4025/jphyseduc.v28i1.2853. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—CDC. Perceived Exertion (Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion scale). 2020. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/measuring/exertion.htm [accessed 18 January 2021]. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borg E. Borg Percetion AB 2024. Sweden. Available from: https://borgperception.se/ [accessed 27 March 2024].

- 6.Kaercher PLK, Glänzel MH, Rocha GG, Schmidt LM, Nepomuceno P, Stroschöen L, et al. The borg subjective perception scale as a tool for monitoring the physical effort intensity. 2019;12(80):1180–5. Available from: http://www.rbpfex.com.br/index.php/rbpfex/article/view/1603. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Camargo MRMC, Zambon F, Moreti F, Behlau M. Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the Brazilian version of the adapted Borg CR10 for vocal effort ratings. CoDAS. 2019; 31(5): e20180112. doi: 10.1590/2317-1782/20192018112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borg E, Magalhães A, Costa MF, MÖrtberg EE. A pilot study comparing the Borg CR scale (centiMax) and the Beck depression inventory for scaling depressive symptoms. Nord Psychol. 2019;71(3):164–76. doi: 10.1080/19012276.2018.1526705 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Araújo ARM. Three studies using the Borg Centimax scale (Borg CR scale, CR 100 cm) for the scaling of depressive symptoms. Institute of Psychology: USP; 2017. Available from: https://teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/47/47132/tde-13122017-093536/pt-br.php. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gugelmin-Almeida D, Tobase L, Polastri TF, Peres HHC, Timerman S. Do automated real-time feedback devices improve CPR quality? A systematic review of literature. Resusc Plus. 2021; 6. doi: 10.1016/j.resplu.2021.100108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Heart Association. American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care circulation. 2020;42(2):S336. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005; 52(5):546–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarivate. EndNote. Philadelphia, 2024. Available from: https://endnote.com/product-details/ [accessed 27 March 2024].

- 14.Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018. Nov 19;18(1):143. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews 2021;10:89. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chi CH, Tsou JY, Fong-Chin Su FC. Effects of rescuer position on the kinematics of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and the force of delivered compressions. Resuscitation. 2008; 76(1):69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barash DM, Raymond RP, Tan Q, Silver AE. A new defibrillator mode to reduce chest compression interruptions for health care professionals and lay rescuers: a pilot study in manikins. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2011. Jan-Mar;15(1):88–97. doi: 10.3109/10903127.2010.531375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niederer M, Tscherny K, Burger J, Wandl B, Fuhrmann V, Kienbacher C, Schreiber W, et al. Influence of high altitude after a prior ascent on physical exhaustion during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a randomised crossover alpine field experiment. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2023;31(59). Available from: doi: 10.1186/s13049-023-01132-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rehnberg L, Russomano T, Falcão F, Campos F, Evetts SN. Evaluation of a novel basic life support method in simulated microgravity. Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 2011;82(2):104-10(7). doi: 10.3357/asem.2856.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fischer H, Zapletal B, Neuhold S, Rützler K, Fleck T, Frantal S, et al. Single rescuer exertion using a mechanical resuscitation device: a randomized controlled simulation study. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(11):1242–7. doi: 10.1111/acem.12008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Tulder R, Roth D, Krammel M, Laggner R, Heidinger B, Kienbacher C, et al. Effects of repetitive or intensified instructions in telephone assisted, bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation: an investigator-blinded, 4-armed, randomized, factorial simulation trial. Resuscitation. 2014;85(1):112–8. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barcala-Furelos R, Szpilman D, Palacios-Aguilar J, Costas-Veiga J, Abelairas-Gomez C, Bores-Cerezal A, et al. Assessing the efficacy of rescue equipment in lifeguard resuscitation efforts for drowning. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2016;34(3):480–5. Available from: doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Asselin N, Choi B, Pettit CC, Dannecker M, Machan JT, Merck DL, et al. Comparative analysis of emergency medical service provider workload during simulated out-of-hospital cardiac arrest resuscitation using standard versus experimental protocols and equipment. Simul Healthc. 2018;13(6):376–86. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trowbridge C, Parekh JN, Ricard MD, Potts J, Patrickson WC, Cason CL. A randomized cross-over study of the quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation among females performing 30:2 and hands-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation. BMC Nursing. 2009;8(6). doi: 10.1186/1472-6955-8-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chi CH; Tsou JY; Su FC. Effects of compression-to-ventilation ratio on compression force and rescue fatigue during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Am J Emerg Med. 2010; 28(9),1016–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsou JY, Kao CL, Tu YF, Hong MY, Su FC, Chi CH. Biomechanical analysis of force distribution in one-handed and two-handed child chest compression- a randomized crossover observational study. BMC Emerg Med. 2022;22(13). doi: 10.1186/s12873-022-00566-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barcala-Furelos R, Barcala-Furelos M, Cano-Noguera F, Otero-Agra M, Alonso-Calvete A, Martínez-Isasi S, et al. A comparison between three different techniques considering quality skills, fatigue and hand pain during a prolonged infant resuscitation: A cross-over study with lifeguards. Children (Basel). 2022;17;9(6):910. doi: 10.3390/children9060910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bánfai B, Musch J, Betlehem J, Sánta E, Horváth bB, Németh D, et al. How effective are chest compressions when wearing a mask? A randomised simulation study among first-year health care students during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Emerg Med. 2022;22(82). doi: 10.1186/s12873-022-00636-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manoukian MAC, Rose JS, Brown SK, Wynia EH, Julie IM, Mumma BE. Development of a model to measure the effect of off-balancing vectors on the delivery of high-quality CPR in a moving vehicle. Am Jour Emerg Med. 2022;61:158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2022.08.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Havel C, van Tulder R, Schreiber W, Haugk M, Richling N, Trimmel H, et al. Randomized crossover trial comparing physical strain on advanced life support providers during transportation using real-time automated feedback. Academic emergency medicine. 2011;18(8),860–7. Available from: doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01124.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vaillancourt C, Midzic I, Taljaard M, Chisamore B. Performer fatigue and CPR quality comparing 30:2 to 15:2 compression to ventilation ratios in older bystanders: A randomized crossover trial. Resuscitation. 2011;82(1):51–6. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Tulder R, Roth D, Havel C, Eisenburger P, Heidinger B, Chwojka CC, et al. "Push as hard as you can" instruction for telephone cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a randomized simulation study. J Emerg Med. 2014;46(3):363–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.08.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Tulder R, Roth D, Krammel M, Laggner R, Schriefl C, Kienbacher C, et al. Effects of a voice metronome on compression rate and depth in telephone assisted, bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation: an investigator-blinded, 3-armed, randomized, simulation trial. 2015. [cited 2021 Jan 18]; 27(6):357–63. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29094836/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sato T, Takazawa T, Inoue M, Tada Y, Suto T, Tobe M, et al. Cardiorespiratory dynamics of rescuers during cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a hypoxic environment. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2018;36(9):1561–4. Available from: doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Egger A, Niederer M, Tscherny K, Burger J, Fuhrmann V, Kiembacher C, et al. Influence of physical strain at high altitude on the quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2020;28(19). doi: 10.1186/s13049-020-0717-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakashima Y, Saitoh T, Yasui H, Ueno M, Hotta K, Ogawa T, et al. Comparison of chest compression quality using wing boards versus walking next to a moving stretcher: a randomized crossover simulation study. J Clin Med 2020;23;September(5):1584. doi: 10.3390/jcm9051584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahn HJ, Cho Y, You YH, Min JH, Jeong WJ, Ryu S, et al. Effect of using a home-bed mattress on bystander chest compression during out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Hong Kong Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2021;28(1):37–42. doi: 10.1177/1024907919856485 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tobase L, Peres HHC, Polastri TF, Cardoso SH, Souza DR, Almeida DG, et al. O Uso da Escala de Borg na Percepção do Esforço em Manobras de Reanimação Cardiopulmonar. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2023;120(1):e20220240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marquis A, Douillet D, Morin F, Chauvat D, Sechet A, Lacour H, et al. Comparison of chest compression quality between the overlapping hands and interlocking hands techniques: A randomised cross-over trial. Am Jour Emerg Med. 2023;74:9–13. Available from: doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2023.08.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li F, Yang CP, Chang CH, Ho CA, Wu CY, Yeh HC, et al. Effect of the Brief Instructional Video Intervention on the Quality of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. Int J Med Sci 2023; 20(1):70–78. doi: 10.7150/ijms.79433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Havel X, Herkner H, Haugk M, Richling N, Riedmuller E, Trimmel H, et al. Physical strain on advanced life support providers in different environments. Resuscitation. 2008;77(1):81–6. Available from: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu S, Vaillancourt C, Kasaboski A, Taljaard M. Bystander fatigue and CPR quality by older bystanders: a randomized crossover trial comparing continuous chest compressions and 30:2 compressions to ventilations. CJEM. 2016;18(6):461–8. doi: 10.1017/cem.2016.373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Skulec R, Truhlar A, Vondruska V, Parizkova R, Dudakova J, Astapenko D, et al. Rescuer fatigue does not correlate to energy expenditure during simulated basic life support. Signa vitae. 2016;12(1):58–62. doi: 10.22514/SV121.102016.10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pompa N, Douma MJ, Jaggi P, Ryan S, MacKenzie M, O’Dochartaigh D. A randomized crossover trial of conventional versus modified "Koch" chest compressions in a height-restricted aeromedical helicopter. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2020;24(5):704–711. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2019.1695300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kingston T, Tiller NB, Partington E, Ahmed M, Jones G, Johnson MI, et al. Sports safety matting decreases cardiopulmonary resuscitation quality and increases rescuer perceived exertion PLoS ONE. 2021;16(7):e0254800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0254800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Manoukian M, Tancredi D, Linvill M, Wynia E, Beaver B, Rose J, et al. Manual versus mechanical delivery of high—quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation on a river—based fire rescue boat. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine. 2022; 1(8). doi: 10.1017/S1049023X22001042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Santos-Folgar M, Fernández-Méndez F, Otero-Agra M, Abelairas-Gómez C, Manuel M, Rodríguez-Núñez, et al. Infant cardiopulmonary resuscitation quality while walking fast: a simulation study. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2022;38(2):e973–e977. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000002505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chang CH, Hsu YJ, Li F, Chan YS, Lo CP, Peng GJ, et al. The feasibility of emergency medical technicians performing intermittent high-quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Int J Med Sci 2021;18(12):2615–2623. doi: 10.7150/ijms.59757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dong X, Zhou Q, Lu Q, Sheng H, Zhang L, Zheng Z. Different Resting Methods in Improving Laypersons Hands-Only Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Quality and Reducing Fatigue: A Randomized Crossover Study. Resuc. Plus. 2021;12(08). doi: 10.1016/j.resplu.2021.100177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aamot IL, Forbord SH, Karlsen T, Støylen A. Does rating of perceived exertion result in target exercise intensity during interval training in cardiac rehabilitation? A study of the Borg scale versus a heart rate monitor. J Sci Med Sport. 2014;17(5):541–545. Available from: doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2013.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paraskevopoulos E, Koumantakis GA, Papandreou M. A Systematic Review of the Aerobic Exercise Program Variables for Patients with Non-Specific Neck Pain: Effectiveness and Clinical Applications. Healthcare. 2023;11(3):339. Available from: doi: 10.3390/healthcare11030339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Havel C, Schreiber W, Trimmel H, Malzer R, Haugk M, Richling N, et al. Quality of closed chest compression on a manikin in ambulance vehicles and flying helicopters with a real time automated feedback. Resuscitation. 2010. Jan;81(1):59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cheng A, Belanger C, Wan B, Davidson J, Lin Y. Effect of emergency department mattress compressibility on chest compression depth using a standardized cardiopulmonary resuscitation board, a slider transfer board, and a flat spine board: a simulation-based study. Simul Healthc. 2017;12:364–369. Available from: doi: 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sainio M, Hellevuo H, Huhtala H, Hoppu S, Eilevstjønn J, Tenhunen J, et al. Effect of mattress and bed frame deflection on real chest compression depth measured with two CPR sensors. Resuscitation. 2014; 85(6): 840–843. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marcin T, Trachsel LD, Dysli M, Schmid JP, Eser P, Wilhelm M. Effect of self-tailored high-intensity interval training versus moderate-intensity continuous exercise on cardiorespiratory fitness after myocardial infarction: A randomised controlled trial. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2022;65(1):101490. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2021.101490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chuang ML, Sia SK, Chang KW. Resting pulmonary function and artery pressure and cardiopulmonary exercise testing in chronic heart failure patients in Taiwan - a prospective observational cross-sectional study comparing healthy subjects and interstitial lung disease patients. Ann Med. 2023;55(1):2228696. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2023.2228696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Radtke T, Crook S, Kaltsakas G, Louvaris Z, Berton D, Urquhart DS, et al. ERS statement on standardisation of cardiopulmonary exercise testing in chronic lung diseases. Eur Respir Rev. 2019;28(154):180101. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0101-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Paradowska-Nowakowska E, Łoboda D, Gołba KS, Sarecka-Hujar B. Long COVID-19 Syndrome Severity According to Sex, Time from the Onset of the Disease, and Exercise Capacity-The Results of a Cross-Sectional Study. Life (Basel). 2023;13(2):508. doi: 10.3390/life13020508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Botelho RMO, Campanharo CRV, Lopes MCBT, Okuno MFP, Góis AFT, Batista REA. Use of the metronome during cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the emergency room of a university hospital. Rev. Latino-Am. Nursing. 2016;24:e2829. 10.1590/1518-8345.1294.2829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kurowski A, Szarpak Ł, Bogdański Ł, Zaśko P, Czyżewski Ł. Comparison of the effectiveness of cardiopulmonary resuscitation with standard manual chest compressions and the use of true CPR and pocket CPR feedback devices. Kardiol Pol. 2015;73(10):924–30. doi: 10.5603/KP.a2015.0084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Truszewski Z, Szarpak L, Kurowski A, Evrin T, Zasko P, Bogdanski L, et al. Randomized trial of the chest compressions effectiveness comparing 3 feedback CPR devices and standard basic life support by nurses. Am J Emerg Med 2016;34(3):381–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zuhl M. Tips for Monitoring Aerobic Exercise Intensity. American College of Sports Medicine 2020. Available from: https://www.acsm.org/docs/default-source/files-for-resource-library/exercise-intensity-infographic.pdf?sfvrsn=f467c793_2. [Google Scholar]

- 63.The British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. Reference tables for assessing, monitoring and guiding physical activity and exercise intensity for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Rehabilitation. BACPR, 2019. Available from: https://www.bacpr.org/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/60110/BACPR-Ref-Table-Booklet-April-2019.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 64.Martins R, Assumpção MS, Schivinski CIS. Perceived exertion and dyspnea in pediatrics: review of assessment scales. Medicine (Ribeirão Preto). 2014. [cited 2021 Jan 3];47(1):25–3. Available from: https://www.revistas.usp.br/rmrp/article/view/80094. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

The article does not report further data.